Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book II: I-XXXII - Germanicus victorious

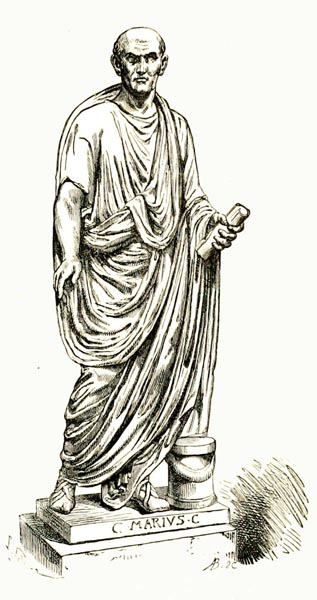

‘Marius’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p450, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book II:I The situation in the East.

- Book II:II The Parthians reject Vonones I as their king.

- Book II:III Prior history in Armenia.

- Book II:IV Vonones removed from Armenia.

- Book II:V Germanicus continues his campaign in Germany.

- Book II:VI Approach by water.

- Book II:VII Germanicus restores the altar dedicated by his father.

- Book II:VIII Germanicus sails his fleet to the River Ems.

- Book II:IX Arminius and his brother Flavus meet at the River Weser.

- Book II:X They argue across the river.

- Book II:XI The death of Chariovalda leader of the Batavian auxiliaries.

- Book II:XII Arminius prepares to attack.

- Book II:XIII Germanicus takes soundings anonymously by night.

- Book II:XIV Germanicus dreams, and then addresses his troops.

- Book II:XV Arminius addresses his men.

- Book II:XVI The Battle of Idistavisus (Battle of the Weser River)

- Book II:XVII The Romans victorious.

- Book II:XVIII The victory dedicated to Tiberius.

- Book II:XIX The Germans mount a further offensive.

- Book II:XX Battle in the woods.

- Book II:XXI Decisive Roman victory.

- Book II:XXII Germanicus celebrates their success.

- Book II:XXIII Return voyage.

- Book II:XXIV The fleet scattered.

- Book II:XXV Germanicus regains the initiative.

- Book II:XXVI Tiberius recalls Germanicus.

- Book II:XXVII Criminal charges against Libo.

- Book II:XXVIII Tiberius allows the evidence to mount.

- Book II:XXIX Libo begs indulgence.

- Book II:XXX Libo’s trial.

- Book II:XXXI Libo commits suicide.

- Book II:XXXII The aftermath of Libo’s trial.

Book II:I The situation in the East

With the consulships of Statilius Sisenna and Lucius Scribonius Libo the Elder (AD16), came disturbances in the kingdoms and Roman provinces of the East, beginning at first among the Parthians, who having petitioned Rome and won acceptance that a king should rule them, had scorned the appointee as an alien, even though he was of the house of Arsaces. This was Vonones I, once sent by Phraates IV (his father) as a hostage to Augustus.

Though he had repelled Roman armies and their leaders, Phraates had shown all due respect to Augustus, and to effect closer ties of friendship had entrusted him with a number of his sons, less from fear of ourselves than from a lack of faith in his countrymen’s loyalty.

Book II:II The Parthians reject Vonones I as their king

After the murder of Phraates and his immediate successors, which were matters internal to Parthia, a deputation from the Parthian nobility arrived in Rome, to appoint Vonones, as Phraates’ eldest son, as their king. Augustus considered this an honour to himself, and bestowed wealth on Vonones, while the barbarians accepted him with the joy they usually show a new monarch.

Feelings of shame soon followed, as they questioned their own degeneration: the Parthians had found a king in an alien country, one tainted by the enemy’s ways; and now the kingdom of Arsaces was considered a Roman province, and treated as such. Where, they asked, was the glory earned by those who had killed Crassus, and ejected Antony, if a slave of Augustus, one who had tolerated all those years of servitude, was to rule Parthia?

Their contempt was deepened by the man’s own behaviour: he being hostile to their way of life, rarely seen in the hunting field, slow to show any interest in horses; lounging about in a litter when passing through the towns; and disdainful of banqueting with his country’s nobility. His retinue of Greeks brought him mockery too, and his habit of setting the royal seal on every household utensil. While his accessibility, and his ready kindness, virtues unknown to the Parthians, were held to be exotic vices; so that being equally foreign to their ways, good or bad he was hated.

Book II:III Prior history in Armenia

Thus, Artabanus was called upon, a descendant of Arsaces by blood, who had been raised among the Scythian Dahae, and though routed in his first engagement, rallied his forces, and seized the kingdom (as Artabanus III).

The defeated Vonones found refuge in Armenia, between Parthian and Roman territory, at that time ungoverned and treacherous as a result of Antony’s criminal actions. The latter had beguiled the late king, Artavasdes II, with a show of friendship, then decked him with chains, and finally handed him over (to Cleopatra VII) for execution.

Artavasdes’ son, Artaxias II, hostile to us on account of his father, defended himself and his crown by virtue of Parthian strength, but following his assassination at the hands of his treacherous relatives, Augustus assigned Tigranes III to Armenia and he was installed in his kingship by Augustus’ stepson, Tiberius. Tigranes’ rule was short; as was that of his son (Tigranes IV) and daughter (Erato) joined, in the oriental manner, in matrimony as well as government.

Book II:IV Vonones removed from Armenia

Next, Artavasdes III was imposed on the country, by order of Augustus, and ejected again not without discredit to us. Gaius Caesar was then delegated to settle Armenian affairs. He granted the Armenian crown to Ariobarzanes, a Mede by origin (he also ruled as Ariobarzanes II of Media Atropatene), who was welcomed by the Armenians for his good looks and noble qualities.

Ariobarzanes meeting an accidental death, his son was not long tolerated; and after experiencing government by the woman called Erato, who was shortly expelled, the weak and wavering people, masterless rather than free, accepted Vonones the fugitive as their king.

But when Artabanus threatened, since scant aid from the Armenians was likely, and since if we chose to defend Vonones in force, war with Parthia would ensue, the governor of Syria, Creticus Silanus, summoned Vonones, and placed him under restriction, leaving him only his title and his luxuries. Vonones’ attempt to escape from this charade we will report in its proper place.

Book II:V Germanicus continues his campaign in Germany

However, the turbulence in the East was not unwelcome to Tiberius as a pretext for removing Germanicus from command of the legions with whom he was familiar and appointing him to fresh provinces where he would be simultaneously exposed to chance and deception. But the deeper the devotion of his men, and the greater his adoptive father’s ill-will, the more intent was Germanicus on a swift victory, after re-consideration of his campaign strategy, given two years of bitter, if successful, warfare.

In line of battle on a level field the Germans had been beaten, while the forests, swamps, brief summer and early onset of winter were to their advantage; his own men were affected not so much by wounds as by the lengthy marches and the loss of weaponry; the Gallic provinces were tired of providing horses; and their long baggage train was subject to ambush, and hard to defend.

Yet if they penetrated from the sea, occupying the ground would be easy for them, and might go undetected by the enemy, while the campaign might commence earlier, and legions and supplies by conveyed together; the cavalry with their mounts could be carried intact from the estuaries up-stream into the heart of Germany.

Book II:VI Approach by water

To this end, he therefore sent Publius Vitellius (the Younger) and Gaius Antius to assess the Gallic tribute, while Silius and Caecina were charged with construction of the fleet. A thousand vessels were thought sufficient and speedily built, some were short craft narrow at fore and stern, wide in the beam, to ride the waves more easily; others were flat-bottomed to run aground without damage; still more had steering oars positioned at both ends, so as to make way in either direction as the bank of oars reversed their stroke. Many were decked to carry military engines, and equally useful for transporting horses and supplies. To manageable sails and swift oars, was added an appearance and threat of military readiness.

The Isle of Batavia was ordained as the meeting place, providing an easy landing, convenient for assembling the troops and sending them on campaign. For the Rhine, flowing seawards in a single channel past insignificant islets, divides in two, so to speak, at the Batavian frontier, retaining its name and force as it passes through Germany, until it joins the North Sea, while washing the Gallic lands in a wider gentler stream, known by the name of the Waal locally but soon changing its designation to the River Meuse and flowing out through an immense estuary into that same North Sea.

Book II:VII Germanicus restores the altar dedicated by his father

While the vessels were being assembled, Germanicus ordered his lieutenant Silius with a lightly-armed force to carry out a raid against the Chatti: he himself, on hearing that the fort situated near the River Lippe was under siege, led six legions to its relief. Due to a sudden worsening of the weather, Silius could do no more than carry off the wife and daughter of Arpus, chief of the Chatti, with a modest quantity of spoils, while the besiegers would not grant Germanicus an opportunity for battle, but melted away on news of his approach; though they demolished the funeral mound he had recently raised over Varus’ legionaries, as well as the former altar set up by Drusus the Elder.

Germanicus restored the altar, and himself led a parade of his legionaries in honour of Drusus, his father; it was not thought proper to reconstruct the funeral mound. Also the whole tract of country between the fort, Aliso (probably at Elsen, near the confluence of the Lippe and Alme) and the Rhine, was strongly fortified, with fresh frontier posts and earthworks.

Book II:VIII Germanicus sails his fleet to the River Ems

The fleet having now arrived, supplies were sent forward, vessels assigned to the legionaries and allies, and Germanicus entered the Canal of Drusus, named after his father, to whom he prayed, by that example and memorial to wisdom and effort, that he be pleased and willing to aid a like endeavour, then navigated the lakes (ancient Flevo) and ocean, voyaging successfully as far as the estuary of the Ems.

The fleet moored by the left bank, in the mouth of the river, erring only in failing to transport the troops upstream and disembark them on the right bank as intended, such that a number of days were lost in building bridges. The cavalry and legionaries crossed the estuary waters before high tide, intrepidly enough, but the auxiliaries at the end of the column and the Batavians there, while dashing into the waves to exhibit their swimming skills, found themselves in difficulties and a number drowned.

While making camp Germanicus heard of an uprising of the Angrivarii to his rear: Stertinius was instantly sent out with cavalry and light infantry to repay their treachery with fire and slaughter.

Book II:IX Arminius and his brother Flavus meet at the River Weser

The River Weser lay between the Roman forces and those of the Cherusci. Arminius, with the rest of his chieftains, halted at the river-bank, seeking to establish whether Germanicus had arrived. On receiving the reply that he had, he asked to be allowed to speak to his brother, Flavus by name, who was serving in the Roman army, a man noted for his loyalty and for the loss of an eye due to a wound received some years before during Tiberius’ command. This being granted, he went forward and was greeted by Arminius; who dismissing his own escort, demanded that the archers posted along our bank of the river be withdrawn also, and when they had retired he asked his brother about his facial disfigurement. On being told the location of the relevant battle, he inquired what reward Flavus had received. Flavus mentioned his increased pay, the torc and gold crown, and other military decorations; Arminius mocking the low price of servitude.

Book II:X They argue across the river

They then began to differ, Flavus insisting on Rome’s greatness, the power of the Caesars, the heavy cost to the vanquished, the ready clemency shown towards those who surrendered; their wives and children not even being treated as enemies: Arminius urging their country’s rights, their ancient liberty, the authority of the gods of the German groves, and the example of their mother, who was his companion in prayer that Flavus would not choose to be a deserter and betrayer of his kith and kin, rather than their liberator.

This gradually descended into a quarrel, that not even the intervening river would have prevented from turning violent if Stertinius had not hastened to restrain Flavus who, filled with anger, was calling for his horse and weapons. On the opposite bank, the menacing figure of Arminius could be seen, threatening battle, with many loud interjections, in the Latin he had acquired as a leader of native auxiliaries in the camps of the Romans.

‘The Roman general Drusus and the Germanic diviner’

Charles Rochussen (Dutch, 1814–1890

The Rijksmuseum

Book II:XI The death of Chariovalda leader of the Batavian auxiliaries

The next day, the Germans formed line beyond the Weser. Germanicus, considering it poor tactics to risk his legions without well-defended bridgeheads, sent the cavalry across by a ford. Stertinius and one of the chief centurions, Aemilius, commanded, attacking at widely separate points to open up the enemy; the leader of the Batavians, Chariovalda, emerging where the current ran fiercest.

The Cherusci, pretending flight, drew him onto level ground surrounded by woods: then breaking out in force from every side, they confronted the Batavians, pursued those who retreated, and where they rallied to form a circle overthrew them by main force with showers of missiles.

Chariovalda, after resisting the enemy’s savagery for some time, exhorting his men to force their way en masse through their attackers while throwing himself into the thickest of the fight, fell, his horse beneath him, to a storm of spear-thrusts, with many of his noblemen around him: the remainder of his band were delivered from danger, by their own efforts, or the arrival of the cavalry led by Stertinius and Aemilius.

Book II:XII Arminius prepares to attack

After crossing the Weser, Germanicus learnt from the mouth of a deserter that Arminius had chosen his ground for battle; and that other tribes had gathered in woods sacred to their Hercules, intending a night-attack on the camp. The informant seemed trustworthy, and they could see the light of fires, while scouts who ventured closer attested to hearing the neighing of horses and the murmur of a confused array.

Germanicus, with the decisive battle near, decided to test the spirits of his men, debating with himself how to ensure the test was genuine. Reports from tribunes and centurions were more often designed to please than accurate in themselves, freedmen were by nature servile, and friends prone to flattery, while if he called an assembly, there too, a few gave the lead while the rest merely applauded. He needed to know the soldiers’ inward thoughts, their hopes and fears, expressed privately, in unguarded moments, over their rations.

Book II:XIII Germanicus takes soundings anonymously by night

At nightfall, leaving his sanctum secretly and unbeknown to the sentries, with a single companion, a wild-beast’s skin over his shoulders, he walked the alleys of the camp, standing beside tents, enjoying the fruits of his reputation, as some praised his nobility, others his bearing, most his patience and courtesy, all of the same mind whether joking or serious, confessing their readiness to show their gratitude in the field, and in the same moment slay these treacherous peace-breakers, in the name of glory and revenge.

During all this, one of the enemy, with a knowledge of the Latin tongue, galloped to the rampart, and in a loud voice offered, in the name of Arminius, wives, land and payment of a gold piece a day for the duration of the war to those who would desert.

The insult caused anger among the legionaries: let day come and battle be joined; they would seize the German land, and carry off those wives; the omen was welcome; the enemy’s women and wealth were destined as their prize!

About the third watch, an attack was launched against the camp, but not a spear was thrown, the enemy finding the ramparts lined with men, and no precaution lacking.

Book II:XIV Germanicus dreams, and then addresses his troops

That same night, brought Germanicus a welcome dream, in which he saw himself offering sacrifice and receiving a fresh and more beautiful garment from the hands of his grandmother, Livia, his own being spattered with the victim’s blood. Strengthened by the omen, the auspices being favourable, he called an assembly and explained what his experience suggested as appropriate to the imminent conflict: open ground was not the only kind favourable to Roman soldiers, but if they used sound judgement, woods and glades also. The huge shields of the barbarians and their immense spears were of less use among the tree-trunks and brushwood than the javelin, the short sword, and close-fitting armour.

The Germans struck thick and fast, seeking the face with their spear-points; they wore neither body-plate nor helmet, and rather than shields strengthened with metal and hide carried pieces of wickerwork or thin painted board. Only the front line wielded spears of a kind, the rest only shorter darts with hardened points. Again, their bodies, while grim enough to the eye and good for short-lived attacks, could not endure wounds. They would turn and flee without shame at the disgrace, without a thought for their leaders, fearful in adversity, and in victory without heed to divine or human law.

If the Romans, tired of road and seaway, desired an end, this battle would procure it; the Elbe was already nearer than the Rhine, and no warfare beyond; let them only grant him, treading in the footsteps of his father and uncle, victory in these same lands!

Book II:XV Arminius addresses his men

This speech of Germanicus was followed by an outburst of military ardour, and the signal to engage was given. Nor did Arminius and the rest of the German chieftains omit to call their clans to witness that these were only the Romans of Varus’ army, quickest to run, who had turned to mutiny rather than face battle: of whom part were showing, to a hostile enemy, their backs, scarred with wounds; part their limbs weakened by storm and tide; with the gods against them and without hope of success. True, they sought ships and pathless seas, to arrive unopposed, to flee without pursuit: but when battle was joined, wind and oars would be no help to beaten men.

They only need remember Roman greed, cruelty, pride: what remained but their hold on liberty, and death before servitude!

Book II:XVI The Battle of Idistavisus (Battle of the Weser River)

So the chiefs led them down, roused and clamouring for battle, to the plain known as Idistavisus, lying between the River Weser and the hills which wind unevenly there, now yielding to the river bank, now lifting in some mountain spur. At the enemy’s back rose the forest, its branches stretching skywards, with clear ground between the tree-trunks. The barbarian ranks occupied the level ground and the margin of the woods: the Cherusci alone were positioned on the hills, so as to charge down from above when the Romans engaged.

Our army advanced as follows: the Gallic and German auxiliaries in front, followed by archers on foot; then four legions with Germanicus, two praetorian cohorts, and the pick of the cavalry; then four more legions and the light infantry with mounted archers and the remainder of the allied cohorts. The troops were alert, and prepared so as to halt in battle array.

Book II:XVII The Romans victorious

On sighting the Cheruscan forces, whose courageous spirit led to their dashing forward, Germanicus ordered the flower of his cavalry to charge the enemy flank while Stertinius with the remaining squadrons rode to attack their rear, Germanicus himself being ready to provide support at the right moment. During this time, his attention was drawn to the happiest of omens, a flight of eight eagles seen seeking and entering the woods. ‘On,’ he cried, ‘follow the birds of Rome, ever the divine spirits of the legions.’

The infantry line and the forward cavalry, charging simultaneously, broke through the enemy rear and flanks. Strange to relate, the two enemy columns fled in opposite directions, those who had held the forest margin rushing to open ground, those stationed in the plain towards the forest. Midway between the two, the Cherusci were being driven from the hills, among them the prominent figure of Arminius, striking, shouting, bleeding, as he tried to maintain the fight.

He had flung himself at our archers, and might have broken through there, had the Raetian, Vindelician and Gallic cohorts not raised their standards against him. Nevertheless, physical strength and his horse’s momentum carried him clear, his face being smeared with his own blood to avoid recognition. Some say that the Chauci, serving with the Roman auxiliaries, knew him and granted him passage. A like courage or deceit allowed Inguiomerus escape: the rest were slaughtered indiscriminately. Many too died attempting to swim the Weser, struck by spears or drowned by the force of the current, or later, overwhelmed by the weight of the crush, and the collapsing river-banks.

Some found shameful refuge by climbing the trees, until, while hiding in the branches, they were derisively shot down by the advancing archers, or were brought down by uprooting the trees.

Book II:XVIII The victory dedicated to Tiberius

It was a magnificent victory, nor for us was it a bloody one. The enemy were massacred from the fifth hour of daylight to nightfall, and the ground was littered with corpses and weapons for a space of ten miles. Among the spoils were found the chains which, confident in the outcome, the enemy had brought for us Romans.

On the field of battle, the soldiers proclaimed Tiberius as Imperator, and raised a mound, planting weapons there, in the style of a victory memorial, with the names of the defeated clans inscribed below.

Book II:XIX The Germans mount a further offensive

Wounds, grief and ruin affected the Germans far less than the resentment and anger this sight evoked. Those who had been prepared to leave their homes and migrate beyond the Elbe, chose to fight and rushed to arm. Commoners and noblemen, young and old, suddenly attacked the Roman line of march, and threw it into confusion.

Ultimately, they chose a position between a stream and the woods, centred on a narrow and sodden stretch of level ground; the woods also were encircled by deep marshland, except on one side where the Angrivarii had raised a broad earthwork separating them from the Cherusci.

Here their foot-soldiers stood: their cavalry being concealed in the glades nearby, so as to be behind the legions as they entered the woods.

Book II:XX Battle in the woods

Nothing of this escaped Germanicus: aware of their intent and their positions, overt or hidden, he turned his enemies’ cunning to their own disadvantage. He assigned the cavalry and the plain to Seius Tubero, his legate; he positioned his infantrymen so that one group might enter the woods marching on a level track, while the other scaled the intervening earthwork: what was difficult he reserved for himself, the rest he left to his legates.

The group assigned to level ground broke through easily; those attacking the barrier, as if scaling a wall, suffered the weight of blows from above. Germanicus, sensing that the fight was unequal at close quarters, ordered the legionaries a little further back, the marksmen and slingers to hurl their missiles and rout the enemy. Javelins were thrown from the engines, and the more conspicuous the defenders the more numerous the wounds that felled them.

Germanicus, with the praetorian cohorts, was the first to lead the charge into the woods, once the rampart was captured. There the fight went head to head: the enemy had their back to the marshes, the Romans theirs to the river and the hills; for both, necessity lay in winning the field, hope in courage, salvation in victory.

Book II:XXI Decisive Roman victory

The Germans showed no lack of spirit, but were overcome by the nature of the battle and their weapons, forced to a standing fight by their immense numbers, unable to thrust or retrieve their long spears in the confined spaces, or employ the momentum of their bodies by running at our men; while we, shields held tight to the chest, hands clasped on sword-hilts, thrusting at the barbarians’ mighty limbs and bare heads, cut a path through the massed warriors.

Arminius was now less forceful, owing to the endless risks, or hampered by the recent wound he had incurred. Moreover, Inguiomerus, rushing about the battle-field, was deserted less by courage than by fortune. Germanicus, too, tearing off his helm so as to be more easily recognised, called on his men to press on with the killing: captives were useless, only the extermination of a tribe would end the war.

Finally, at close of day, he withdrew a legion from the field to start work on the camp: the rest sating themselves with blood till nightfall. The cavalry engagement proved inconclusive.

Book II:XXII Germanicus celebrates their success

After praising the victors in an address, Germanicus raised a pile of weapons with a proud legend, proclaiming that the army of Tiberius Caesar, having subdued the tribes between the Rhine and the Elbe, had dedicated that memorial to Mars, Jupiter and Augustus. He added nothing as regards himself, fearing jealousy or considering the knowledge of his exploits sufficient.

He instructed Stertinius, shortly, to make war on the Angrivarii, unless they had previously surrendered. As suppliants, resisting nothing, they were in fact granted every indulgence.

Book II:XXIII Return voyage

However, as it was already midsummer, some of the legionaries were marched back to winter quarters by land, while Germanicus embarked the majority and sailed then down the River Ems to the North Sea.

Initially they met with a flat calm, resounding to the flapping of sails and the beating of oars, but soon hail slanted down from a mass of dark clouds, as the waves, raised by conflicting winds from every quarter, obscured the view and impeded the steering; while the soldiers, fearful, ignorant of the perils of the sea, by obstructing the sailors or providing ill-timed assistance harmed the exercise of their skills.

Then sky and sea yielded to a southerly, powered by immense trains of cloud rising from Germany’s sodden land and deep rivers, rendered more intense by the cold from the neighbouring north, a storm which overtook and scattered the vessels over the open sea or among islands made dangerous by scattered rocks and hidden shoals.

These, with a little time and effort, were avoided, but when the tide changed and flowed with the wind, no anchor would hold nor could the inrushing waters be baled. Horses, pack-animals, baggage, even weapons were jettisoned to lighten the hulls, that leaked below decks and were overtopped by the waves.

Book II:XXIV The fleet scattered

Just as the North Sea is more violent than other seas, and Germany’s weather noted for its severity, so this disaster, facing hostile shores or an extent of water so vast and profound it is judged the last deep beyond all land, exceeded others in its abnormality and magnitude. Some of the ships sank, yet others were wrecked on remote islands, where, in the absence of all civilisation, the men died of starvation, except those able to live on the flesh of horses likewise driven ashore.

Germanicus’ trireme alone reached the Chaucian coast. For many a day and night, on some cliff or headland, he berated himself for so ruinous an outcome, his friends barely able to prevent him seeking death in those same waves. At last, on a flowing tide with a following wind, the crippled vessels appeared, a rare few under oar, some with makeshift sails, or under tow from sturdier craft: and swiftly refitted they were sent to search the islands. Many were rescued through that act of forethought: many, ransomed from the interior, were returned by the Angrivarians whose loyalty had recently been confirmed; a few driven across to Britain were sent back by its chieftains.

Those who returned from distant parts told wondrous tales of powerful whirlwinds, unknown birds, sea-monsters, enigmatic forms part-human part-creature, things seen or believed real in a moment of terror.

Book II:XXV Germanicus regains the initiative

But though rumours of the fleet’s loss led the Germans to hope for fresh conflict, they prompted Germanicus to ensure its suppression. He ordered Gaius Silius, with thirty thousand of the infantry and three thousand cavalry, to move against the Chatti, while he himself with a larger force attacked the Marsi, whose chieftain, Mallovendus, had recently surrendered himself, and now claimed that the eagle from one of Varus’ legions was buried in a nearby grove, itself minimally defended.

A detachment was immediately sent to draw the enemy forward, while a second force encircled their rear and excavated the site; fortune attended both. Given this, Germanicus pushed on more readily into the interior, attacking and destroying an enemy that dared not engage, or whenever it resisted was routed, and, as prisoners attested, was never more demoralised.

Indeed the Romans were declared invincible, equal to all eventualities; forces who though their fleet was wrecked, their weapons lost, the shore littered with the bodies of their men and horses, had returned to the fight, as bravely, as fiercely and seemingly in greater numbers, than before.

Book II:XXVI Tiberius recalls Germanicus

The army was then led back to winter quarters, delighted at compensating for the disaster at sea with the overall success of their mission. Germanicus added to this by his generosity in making good whatever losses were claimed to have been incurred. There was no doubt also that their enemies were wavering and discussing moves towards peace, and that a further effort next summer might end the war.

But letters from Tiberius constantly urged Germanicus to return and enjoy the triumph decreed him: his successes and misfortunes already sufficed. Great were his battles and achievements, yet he should also remember the cruel and heavy losses incurred by wind and wave, though through no fault of his leadership. He himself, Tiberius added, had been sent into Germany on nine occasions by the divine Augustus, achieving more by diplomacy than force: thus the Sugambrian surrender was achieved, thus the Suevi under King Maroboduus had been bound to keep the peace. The Cherusci and the other rebel tribes might be left to their internal conflicts, now that Roman vengeance was satisfied.

When Germanicus asked for another year to finish what was begun, Tiberius addressed his reluctance more forcefully, offering him a second consulate, the duties of which he would effect in person, at the same time adding that, if there must be further warfare, he might leave his brother Drusus that means to glory, since they had no other enemies at the time, and Drusus could neither pursue the title of Imperator nor win laurels except in Germany. Germanicus delayed no longer, though he was aware all this was a fiction, and that he was being denied through jealousy an honour properly his.

Book II:XXVII Criminal charges against Libo

Around the same time, Libo Drusus, a member of the Scribonian family, was indicted for revolutionary activity. I shall describe the origin, process, and end of this matter, as it marked the first inception of a system that would eat away for many years at public affairs.

A senator, Firmius Catus, one of Libo’s closest friends, had involved that thoughtless youth, who was susceptible to any inanity, in astrological forecasts, magical rites, and even the interpretation of dreams; while at the same time encouraging his luxurious style of living and accumulation of debt, by pointing out to him that Pompey was his great-grandfather; Scribonia, at one time consort to Augustus, his great-aunt; the Caesars his cousins, and his house filled with ancestral portraits; and by sharing his wants and needs; thus accumulating the more evidence with which to entangle him.

Book II:XXVIII Tiberius allows the evidence to mount

When he had found sufficient witnesses, and servants with a like knowledge, he asked for access to Tiberius, who had been advised by a Roman knight close to him, Vescularius Flaccus, of the defendant and the charge. Tiberius, while not rejecting the evidence, refused an audience: as their communication could be maintained through that same intermediary, Flaccus.

In the meantime Tiberius granted Libo a praetorship, inviting him to dinner, where Tiberius showed no sign of estrangement in his gaze, nor emotion in his speech (having buried his anger deep). While he might have curbed Libo’s every word and action, he preferred to note them, until eventually, a certain Junius, persuaded by Libo to try raising the infernal shades with his spells, carried that information to Fulcinius Trio. Celebrated among the professional informers, Trio’s genius was for feeding on ill rumour.

He immediately swooped on the accused, approached the consuls, and demanded a senate enquiry. The Fathers were moreover being called upon, he added, to consider a matter both grave and hideous.

Book II:XXIX Libo begs indulgence

Libo, meanwhile, went into mourning, and with an escort of noblewomen made a tour of the great houses, pleading with his wife’s relatives (the Sulpicii), begging them to speak against his indictment, but was refused everywhere on various pretexts, and with the same degree of alarm.

On the day the senate met, he was so exhausted by fear and anxiety, unless as some say he was feigning illness, that he was carried to the doors of the Curia in a litter, and leaning on his brother (Lucius Scribonius Libo, the Younger) extended his hands to Tiberius while raising his voice in supplication, Tiberius receiving him with unmoved countenance. The emperor then read out the indictment, and the names of the accusers, calmly, appearing neither to mitigate nor aggravate the charges.

Book II:XXX Libo’s trial

Besides Trio and Catus, Fonteius Agrippa and Gaius Vibius added their names to the accusation, and they disputed as to who should state the prosecution case, until Vibius announced that, since no one would concede and Libo was appearing without counsel, he would present the charges one by one.

He produced a woeful set of complaints, including the claim that Libo had consulted his seers as to whether he would acquire enough wealth to cover the Appian Way with coins as far as Brundisium (Brindisi). There was more in the same vein, stupid, vacuous, or if considered with greater sympathy, merely pitiful.

However, regarding one charge, the prosecution argued that a series of notations in Libo’s hand, threatening or mysterious, had been appended to the names of the imperial family and various senators. The defendant denying the allegation, it was resolved that his servants, who might know of all this, be interrogated under torture. And because an old senate decree prohibited their questioning on a capital charge against their master, Tiberius, cunning inventor of new legalistic processes, ordered the slaves to be sold individually to an agent of the treasury, with the obvious purpose of eliciting information about Libo from his servants, while preserving the integrity of the senate decree!

In the light of this, the accused asked for an adjournment to the following day, and left for home, after instructing his relative, Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, to make a last appeal to the emperor.

Book II:XXXI Libo commits suicide

The response was that he should petition the senate. Meanwhile his house was picketed by soldiers, stamping about the portico itself, so noisily and visibly that Libo, at the banquet he had arranged as his last indulgence, clutched at the hands of his servants in torment, pushing his sword at them, and calling out for someone to strike him.

But they, fleeing in fear, overturned the lamp beside the table, and he, now shadowed by death, struck twice at his innards, and collapsed groaning. His freedmen ran to him, and the soldiers witnessing this withdrew.

In the senate, the prosecution was however pursued with the same severity, Tiberius declaring on oath that, however guilty the defendant might have been, he would have petitioned for the man’s life, had he not chosen to hasten his own death.

Book II:XXXII The aftermath of Libo’s trial

Libo’s possessions were divided among his accusers, and extraordinary praetorships were granted to those of senatorial rank. Then, Cotta Messalinus proposed that no effigy of Libo be allowed at the funeral processions of his descendants, and Gaius Lentulus that no member of the Scribonii should carry the surname Drusus.

At the suggestion of Pomponius Flaccus, a number of days of public thanksgiving were instituted. Further, votive offerings were to be made to Jupiter, Mars and Concord, and the thirteenth of September, the anniversary of Libo’s suicide, was to be appointed a feast day, according to an act engineered by Lucius Piso, Asinius Gallus, Papius Mutilus, and Lucius Apronius; which decrees and sycophancy I have told of, in order to show how long this evil has existed in public life.

Other resolutions enacted by the senate commanded the expulsion from Italy of all astrologers and magicians, of whom one, Lucius Pituanius, was flung from the Tarpeian Rock, while another, Publius Marcius, was decapitated by the consuls outside the Esquiline Gate, at the sounding of a trumpet, according to ancient usage.

End of the Annals Book II: I-XXXII