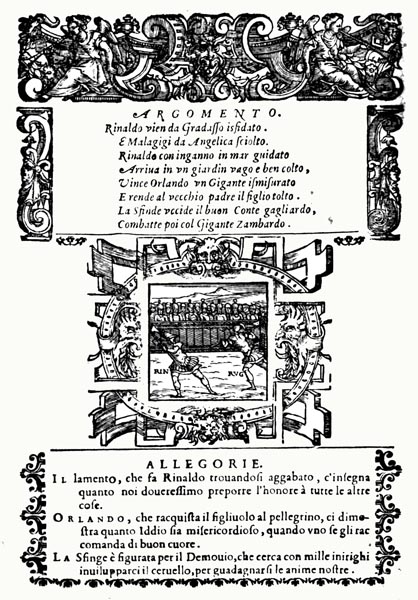

Boiardo: Orlando Innamorato

Book I: Canto V: Seeking Angelica

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book I: Canto V: 1-6: Rinaldo slays Orione, the giant King of Macrobia

- Book I: Canto V: 7-13: Gradasso proposes a duel the following day

- Book I: Canto V: 14-18: Angelica is tormented by her love for Rinaldo

- Book I: Canto V: 19-22: She frees Malagigi but asks a favour of him

- Book I: Canto V: 23-27: He is to bring Rinaldo to her

- Book I: Canto V: 28-31: But Rinaldo, now loathing her, refuses

- Book I: Canto V: 32-35: Malagigi deceives Rinaldo and Gradasso

- Book I: Canto V: 36-39: The demon Draginazzo takes on Gradasso’s form

- Book I: Canto V: 40-42: Rinaldo fights with Draginazzo

- Book I: Canto V: 43-47: Who lures him aboard ship and then vanishes

- Book I: Canto V: 48-52: Rinaldo laments his situation

- Book I: Canto V: 53-55: The ship reaches a garden-isle amidst the sea

- Book I: Canto V: 56-61: We turn to Orlando who encounters a pilgrim in distress

- Book I: Canto V: 62-65: The Count defeats a giant

- Book I: Canto V: 66-69: And climbs the cliff to question the sphinx

- Book I: Canto V: 70-75: He fails to unravel her riddles and slays her

- Book I: Canto V: 76-77: Though the book held the answers to her questions

- Book I: Canto V: 78-83: Orlando fights the giant who guards the Bridge of Death

Book I: Canto V: 1-6: Rinaldo slays Orione, the giant King of Macrobia

You will recall, my lords, how brave Rinaldo

Was much troubled on seeing Orione,

Bearing away poor Ricciardetto.

He abandoned Gradasso completely,

And attacked the giant, who, as you know,

Went all naked into battle, for he

Possessed so thick and hard a hide, all over,

He had no need to clad it with armour.

Now, Rinaldo had dismounted promptly

To keep Baiardo safe from all attack,

At the hands of this giant Orione;

Indeed, he’d swiftly slipped from off his back.

It seems that the giant believed that he

Had at last found a knight that naught did lack

In the way of courage, who sought to fight

Hand to hand, for he mocked him outright;

Rinaldo merely sought to save his steed,

While the giant had not met with Fusberta,

Nor the strength of Rinaldo’s arm; indeed,

If he had, he’d have wished for more armour.

Rinaldo swung, and wrought a mighty deed,

Slicing that wretch’s thigh, who did utter

A loud bellow like a bull, saw the blood,

And dropped Ricciardetto where he stood.

As Ricciardetto lay there on the ground,

Stunned and stupefied, scarcely breathing,

The giant gripped his club, and glanced around,

While Rinaldo stood, patiently, watching.

The king aimed a blow, seeking to confound

The knight, like to send a mountain reeling.

He had merely retired a pace or two,

When, behold, King Gradasso came in view.

Rinaldo was unsure of what this meant,

Though he certainly felt a touch of fear,

Yet appeared as well-nigh indifferent,

And a swift blow towards the giant did steer.

Fusberta whistled, swung with true intent,

Sweeping through the air, and slicing sheer

Through the giant’s side; so fiercely it flew

That the wretch fell to the earth, cut in two.

The bold knight scarcely lingered though,

Not seeking to observe the giant’s descent,

But swiftly remounted his Baiardo,

A close meeting with Gradasso his intent.

But the king was still musing on the blow,

The wondrous sword-stroke, that the giant had rent,

And signed, with his un-gauntleted hand,

For him to join him; well-nigh a command.

Book I: Canto V: 7-13: Gradasso proposes a duel the following day

He addressed the warrior: ‘Come, sir knight,

It would surely be a crime for such prowess,

And such courage as you have shown in fight,

To perish here; twould bring me much distress.

You’re surrounded by my men, such that flight

Offers not the smallest chance of success;

To escape’s impossible, you surely see,

You’d be caught or slain, should you seek to flee.

Allah forbid that I show disrespect

To as valiant a warrior as you,

So, for honour’s sake, I hereby elect

(Since the evening is nigh upon us too)

That we fight tomorrow and, there, effect

A duel on foot, so naught can hide our true

Abilities; unequal mounts do so,

Hence, I’ll quit my mare, and you Baiardo.

But let us first agree upon a pact:

That if you chance to kill or capture me,

I’ll release all my prisoners intact;

King Marsilio’s subjects shall go free,

And your friends, by my gracious act.

But if, instead, I gain the victory,

Baiardo’s mine; and, win or lose the test,

I’ll depart, nor come again to the West.’

Rinaldo sought no time to think, but cried:

‘Sire, this duel must be; an encounter

That will but bring me pleasure, on my side,

And can only add to my own honour.

Your skill and prowess are such beside

That, if I’m defeated by your valour,

There is surely no shame in such a fate,

Rather glory, that I die at your dictate.

As for your suggestion, I reply

That I wish you well, and thank you kindly,

Yet I am not in such dire straight, that I

Must beg for my life, or seek your mercy,

For, come the whole world in arms, I defy

Its efforts, and your guards’, to prevent me

From departing; and if you wish, perchance,

To prove it, I suggest that they advance.’

Promptly then, the king and knight agreed,

On the required arrangements for the fight.

The place would be the shore, six miles indeed

From their forces, and therefore out of sight.

Each could employ the armour he might need,

For defence, and the weapon of a knight,

His good sword; but no lance, or club, or dart,

He’d bring, nor a friend, that might take his part.

Each was eager, and prepared to appear

For the encounter, at the break of day,

And rehearsed in their minds, devoid of fear,

The varied skills that they might set in play.

Yet, before they arm, I would have you hear

Of Angelica, at home, in Cathay,

Having been conveyed, by magic art,

(As I’ve related) to that far-off part.

Book I: Canto V: 14-18: Angelica is tormented by her love for Rinaldo

Despite the distance, she could not remove

From her mind, the image of Rinaldo;

And as a wounded deer (here, struck by Love),

Whose pain but grows with time, and feels the flow

Of heart’s-blood, finds the faster she may move,

The more it hurts, and adds to her deep woe,

So, she, whose flame burnt higher, for Rinaldo

Felt the fire in her heart increase also.

To sleep at night the maid could ne’er aspire,

For thoughts of love now possessed her mind.

And if, when long-tormented in Love’s fire,

She found a little rest, with tears half-blind,

Before the dawn, she dreamed, in her desire,

Of Rinaldo, who seemed to flee, unkind

As ever, filled with anger, from her sight;

She abandoned, in that forest, by the knight.

She ever turned her face towards the west,

As she sighed and she wept, while exclaiming:

‘In that place, midst those people, he doth rest

That cruel, yet so handsome man,’ complaining

Of him. ‘He cares naught for me, he confessed,

And this one thing saddens all my being,

That I must love, despite myself, I own,

A man whose heart is harder than a stone.

To my art’s extremes, I’ve sought to pursue,

Every enchantment known, every spell,

Culled rare herbs at night, when the moon was new,

And, at the sun’s eclipse, strange roots, as well,

Yet this savage pain, that pierces me through,

And grieves my poor heart more than I can tell,

Enchantments, herbs or gems cannot remove;

Love conquers all; such things but idle prove.

Why could he not have come to Merlin’s stone,

Where I captured the mage, Malagigi?

I’d not have screamed, faced with him alone!

His wretch of a cousin, I’ve sunk deeply,

Yet I’ll release him, so that, having shown

A fine example of true courtesy,

The knight may see how, by loving kindness,

Is revealed his endless ungratefulness.’

Book I: Canto V: 19-22: She frees Malagigi but asks a favour of him

With this, she plunged far beneath the sea,

To where Malagigi was imprisoned.

By magic, she was borne there easily,

While no other way there could be opened.

When the mage heard the charmed bolt shot free,

He thought some demon had been commissioned

To murder him, there, in that sunken keep,

For no one ever wandered midst the deep.

Once there, she had the wise Malagigi

Borne, in a trice, to her palace above.

And, in a splendid chamber she, swiftly,

From his arms, the heavy chains did remove.

As yet, she’d done all this most silently,

But when his feet were free, and he could move,

She said: ‘You were my prisoner, my lord,

But, to you, full liberty I now afford.

Yet since I’ve released you from that cell,

I ask a favour of you, in return;

If you brought me your cousin, twould be well,

From death to life I’d be restored, in turn.

Rinaldo, I mean; for with pain I dwell,

I hide not my deep woe; I freeze and burn;

Love torments me, with fire and ice, I say,

And allows me no peace, by night or day.

If you will swear to me, on your honour,

That you will have Rinaldo come to me,

I’ll reward you indeed for that small favour,

With what you desire most fervently,

Your precious book of magic; however,

No deceit, if to my terms you agree!

I warn you, an enchanted ring I bear,

That can thwart your magic spells, everywhere.’

Book I: Canto V: 23-27: He is to bring Rinaldo to her

Malagigi raised no opposition,

But swore to what she wished, readily.

Without knowing Rinaldo’s position,

He could bend his will, of a certainty.

At sunset, he started on his mission,

And as darkness descended, rapidly,

Upon a demon’s back the bold mage flew,

Through the air, all Earth open to his view.

A flow of speech the demon did maintain,

(As he sped upon his way, through the night)

With regard to the invasion of Spain,

And Ricciardetto’s capture in the fight,

And the terms of the duel did explain.

Of all that had occurred, throughout that flight,

The demon spoke, although I’ll not deny

He coloured it, well-knowing how to lie.

At last, they were approaching Barcelona,

(It was, perhaps, an hour before the dawn).

Once there the mage quit the demon’s shoulder,

And searched the barrack-tents, as he had sworn,

For the knight, who, ere the day was older,

To fair Angelica must now be borne.

He found Rinaldo, fast asleep, within,

And woke him, so his own task might begin.

Rinaldo had never felt so happy,

In his life, as when he saw his cousin there,

And, on his leaving his bed instantly,

Warm embraces passed between the pair.

Then Malagigi said: ‘Come, dress swiftly,

For an oath I made, a promise did swear.

You can release me from it, if you will;

If not, I must return, a captive still.

Let no suspicion in your mind be bred,

Of your facing any kind of danger,

You need simply take a maiden to bed,

Fair as the lily, glowing like amber.

In freeing me, with joy you shall be fed.

This maid, with a blushing face, moreover,

Is one perchance you’d ne’er have thought to seek,

Angelica it is, of whom I speak.’

Book I: Canto V: 28-31: But Rinaldo, now loathing her, refuses

Now Rinaldo, upon hearing the name

Of that maid whom he now loathed, heart and soul,

Felt a deep annoyance, while a flame

Of pride and anger o’er his cheeks now stole.

He sought to reply, but no answer came,

His throat seemed choked as by a blazing coal,

Tongue-tied, he now would speak, now delay,

And, for a while, not a word could he say.

At last, being yet a knight of valour,

Who e’er refused to hide behind a lie:

‘Aught would I do that preserves my honour,

(I would even consent, my friend, to die)

Face the harshest fortune, any danger,

All grief and suffering,’ such was his reply,

‘Yet, hear this Malagigi, I will never

Not even to free you, seek her ever.’

Malagigi was stunned by his answer;

Those words he’d ne’er expected to hear.

And he begged Rinaldo to reconsider,

And keep him from the dungeon he did fear,

Out of mercy, and reminded him of former

Services, should he hold him less than dear

As his kin; but all proved of no avail;

Rinaldo still refused to hear his tale.

When he’d pleaded a while, yet been denied,

He cried: ‘Rinaldo, tis true what they say,

The ungrateful are never satisfied,

Though the kindest of good deeds comes their way.

I’ve well nigh been to Hell for you, and fried

In its fires, yet to prison you’d convey

My body thus, to perish. Yet, beware,

I can drive you to shame and deep despair.’

Book I: Canto V: 32-35: Malagigi deceives Rinaldo and Gradasso

When he’d spoken, he turned upon his heel,

And vanished in a trice, upon his way,

And then, once he was where he might reveal

(Having conjured up a plan, I should say)

His great book of magic spells, yet conceal

His power to call up demons, night or day,

He chose Falsetta, and Draginazzo,

From those summoned, and let the others go.

As a herald he disguised this Falsetta,

Dressed like a servant to Marsilio,

The demon bore Spanish insignia,

Coat of arms, and staff of office, also,

And he then appeared as a messenger,

In Rinaldo’s name, before Gradasso,

To inform him that, this next day, at three,

Rinaldo would take the field; joyously,

Gradasso agreed, and gave Falsetta

A golden cup to reward the fellow;

The demon then returned to his master,

And changed his semblance so as to show

A ring in his ear, not on his finger,

His head wrapped in a cloth; the robe below

Down almost to his feet, and trimmed with gold,

As Gradasso’s words he feigned to unfold.

He’d the look of a Persian Al-Mansur,

With a gilded sword and a mighty horn,

And, to the king and court of Spain, he bore

A message that at break of day, this morn,

His master Gradasso would walk the shore,

Armed, and alone, such was the oath he’d sworn,

Nor would that valiant king fail to appear;

While the imp ensured Rinaldo could hear.

Book I: Canto V: 36-39: The demon Draginazzo takes on Gradasso’s form

Rinaldo, therefore, armed himself in haste,

(It being near to dawn) amidst all there,

And, quietly, Ricciardetto he graced

With the task of his steed Baiardo’s care.

‘I know not if I’ll win, or be disgraced;

I place my trust in God, in this affair,

Yet if the Lord shall see me fight in vain,

Command my men; return to Charlemagne,

Obey his will, while yet you breathe, I say,

Don’t follow my example, for, I own,

I have erred through anger, many a day,

Or disdain; he hurts his foot, not the stone,

That kicks the wall, in furious display,

To my king, who is worthy of his throne,

And has ever favoured me all his reign,

I leave Baiardo, if perchance I’m slain.’

He spoke other words to Ricciardetto,

And, with tears in his eyes, clasped him once more,

Then, leaving behind the steed, Baiardo,

Our knight, alone, proceeded to the shore.

A ship was anchored there, in dawn’s fair glow,

No sailors seemed aboard, or none he saw,

And no one else was present on the sand,

As he waited for Gradasso, sword in hand.

Yet Draginazzo appeared, and, behold,

He’d the form of Gradasso, and was dressed

In a surcoat all of blue, barred with gold,

O’er bright armour, its steel the very best,

While a crown his shining helm did uphold,

That had a pure white pennant for a crest.

A scimitar he had, and that white horn

That by the king himself was always borne.

Book I: Canto V: 40-42: Rinaldo fights with Draginazzo

The demon now approached along the shore,

Walking in the manner of Gradasso.

From its sheath his scimitar he did draw.

He seemed to shed bright flame, to spark, to glow.

Rinaldo, cautious as to what lay in store,

Stood ready, his sword positioned low,

But Draginazzo hesitation read,

And aimed a furious blow at his head.

Rinaldo replied to that hissing blade

With a fierce back-handed stroke to the thigh.

Both redoubled their blows, as on they laid,

Waxing more spirited as time went by.

Our knight breathed hard, with every move he made,

Seeking to prove his strength, his courage high,

And discarded his shield, as on he poured,

Employing both his hands to swing his sword.

He struck hard, seeking to win high renown,

Throwing all his weight behind that fierce blow.

Fusberta struck against the demon’s crown,

Sending his white crest to the ground below,

Then slid along the helm, and ran on down,

Sounding against the hard shield of his foe,

Scoring, from top to bottom, all it found,

Till its tip sank, a foot deep, in the ground.

Book I: Canto V: 43-47: Who lures him aboard ship and then vanishes

The cunning demon now seized the moment,

Turned his back, at once, and appeared to flee;

While Rinaldo, not perceiving his intent,

Thought him beaten, and pursued joyously.

While he upon this blind pursuit was bent,

Falsetta set his course towards the sea,

Our knight crying: ‘Wait, my lord Gradasso:

He that flees can’t hope to ride Baiardo;

Is this the courage that a monarch shows?

Feel you no shame in showing me your back?

Turn; here’s the steed, none better I suppose,

Whether in stout defence or bold attack.

His saddle’s new, see how his fine coat glows,

Fresh shod but yesterday, naught does he lack.

Come, take him, sire, and be not so afraid,

I offer him at the point of my blade.’

The demon waited not, but sped away

As if he were carried on the breeze,

And like an arrow sped across the bay,

To land aboard the vessel, there, with ease.

Nor did Rinaldo linger on his way,

But plunged in, and reached it, by degrees,

Climbed aboard and dealt such a blow, I vow,

As made the demon leap from stern to bow.

Now, Rinaldo was absorbed in the fight,

And pursued the imp, wielding Fusberta,

Unaware that the vessel was in flight,

And, across the waves, sped ever further.

So involved in the battle was our knight,

That its motion he failed to discover

Till the ship was seven miles from the shore,

When the imp vanished, to be seen no more.

He disappeared in a puff of smoke. Ask not

If Rinaldo was amazed; he was indeed.

He searched the ship, examined every spot;

It was empty, though it moved away at speed,

For the sails were full, and thus the upshot

Was that he saw the land behind recede,

And alone on the deck, his strength all spent,

You may imagine that bold knight’s lament!

Book I: Canto V: 48-52: Rinaldo laments his situation

‘Ah, Lord, on high,’ he cried, ‘for what sin

Have you punished me with this misfortune?

I know I’ve often erred (where to begin?)

But this penance is most inopportune.

I’ll be shamed forever, without, within

The royal court, my motives they’ll impugn,

Not a soul will believe a word I say

Should I recount all that’s occurred this day.

The king has appointed me commander,

And well-nigh placed his realm in my hand,

But like a false, vile, coward of a traitor,

I now flee across the waves, far from land.

I seem to hear the roar, growing louder,

Of that foreign host, pounding o’er the sand,

And the cries of my troops, their misery,

As Alfrera slays, and seeks the victory.

How could I quit you, my Ricciardetto?

How could I leave you to the enemy?

And you, sad prisoners of Gradasso:

Gucciardo, Alardo, Ivone?

I wish I’d been vanquished by the foe,

On that day we entered Spain, so boldly!

I was thought fine and brave, in my armour;

Yet this shame has robbed me of my honour.

I sail the sea. Who will excuse the deed?

When I’m accused, by, all of cowardice?

He condemns himself that betrays his creed,

I am no knight, who breaks our code in this.

Would that I was Ferrau, and he was freed,

And I, in his place, prisoned in the abyss,

To die in torment, in those depths below,

Rather than live on, thus, and bear such woe.

What will be said, at Charlemagne’s great court,

When this affair is spoken of, in France?

To what shame will Mongrana’s House be brought,

By one of their own fleeing sword and lance?

Gano, all Maganza’s House in short,

Will through the halls, in triumph, there advance.

Woe is me! I called the man a traitor,

Yet can no more; lacking in true honour.’

Book I: Canto V: 53-55: The ship reaches a garden-isle amidst the sea

So, the valiant warrior groaned and sighed,

And added fresh cries to his sad lament,

Reflecting thrice, now humbled in his pride,

As to whether to his own death to consent;

And thrice he, thus, approached the vessel’s side,

As if to leap down, armed, was his intent.

Fear for his soul, and dread of Hell below,

Alone restrained Rinaldo in his woe.

The ship sailed on, meanwhile, o’er the sea,

Three hundred miles beyond the Straits, flying

Faster than a dolphin swims, wondrously,

Amidst the waves, to port its course lying,

As from Seville a stern-wind blew strongly,

While our knight was yet groaning and sighing.

Then it tacked, and, in an instant, released

From that near gale, sailed gently to the east.

The ship was packed with stores on every side;

(Though it seemed to lack both captain and crew)

With bread and wine, in casks, twas well-supplied.

Rinaldo felt no wish to eat, tis true,

But prayed to God and in Him did confide.

And as he knelt in prayer, there came in view,

A garden-isle, graced by a palace, fair,

A garden bordered by the waves everywhere.

Book I: Canto V: 56-61: We turn to Orlando who encounters a pilgrim in distress

I shall leave him in that marvellous isle,

Of which I’ll tell many a wondrous thing,

And return to Orlando, who, meanwhile,

As I’ve said, in amorous thought, pursuing

Angelica, day and night, for many a mile,

Was forever further eastwards journeying,

Searching, alone, for that absent beauty,

Though none could offer news of the lady.

He’d crossed the waters of the River Don,

And, meeting not a soul, he rode all day,

That brave warrior, still travelling on,

But, at nightfall, met a pilgrim, on his way;

(The man was sad and aged) whereupon,

The palmer cried: ‘Alas,’ in deep dismay,

‘Who has reft from me, my sole hope and joy?

I commend you to God, O, my lost boy!’

‘May God aid you, pilgrim,’ Orlando cried,

‘Tell me the reason for your sad lament.’

The wretched man his complaints multiplied,

Crying: ‘Alas for my poor innocent!

Great ill-luck have I met with here,’ he sighed,

‘And a giant of a man with foul intent.’

Orlando begged him then his tale to share,

And give the substance of the whole affair.

‘I’ll tell you the reason for my sadness,’

He replied: ‘since you clearly seek to know.

Two miles away, behind me, more or less,

There a tall cliff, that you can see, although

My sight’s so dim, through age and my distress,

That I cannot, and, observed from below,

Its colour seems that of a living flame,

While all bare is the summit of that same;

And a voice from there echoes all around,

And though I cannot tell you what it says,

In this world there is no more fearful sound.

Beneath the cliff a foaming torrent plays,

And like a crown encircles all that ground.

There’s a gate (guarded by a giant always)

Tis of adamant, that leads to a bridge

Of dark-coloured stone, beneath the ridge.

My son, who’s but a little lad, and I

Were walking close to that place, a while ago;

And the cruel and evil giant my weak eye

Failed to spot; the wretch was well-hidden though,

Nigh-concealed behind some boulders nearby.

He seized my boy; he’ll consume him, I know.

And, now you’ve heard the reason why I grieve,

Well, my advice is: turn your steed, and leave.’

Book I: Canto V: 62-65: The Count defeats a giant

Orlando thought a moment, then replied:

‘No matter what, I’m riding on my way.’

Said the pilgrim: ‘God save you then!’ and sighed,

You’ve no wish it seems to survive the day.

Believe me, tis a fact, nor have I lied,

When you have seen that giant’s strength in play,

His height, his great legs, his monstrous arms,

Your hair will rise; all passers-by he harms.’

Orlando smiled, and begged the man to wait,

At that spot, for God’s sake, a little while;

But if an hour had passed, and he was late

In returning, to put a goodly mile,

Or more, between himself and that dark gate.

‘An hour’, he repeated; then for that pile

Of blood-red rocks he headed; by and by

The giant appeared: ‘So then you wish to die,

Bold knight, it seems,’ he called to Orlando.

‘The King of Circassia placed me here.

None may pass, for there dwells an evil foe

On that cliff, a monstrous form, all men fear,

Who will answer any question; yet, know,

That all who choose before her to appear,

Must, in turn, solve the riddles she poses,

And dies unless true answers he discloses.’

Orlando now demanded the young boy,

But the giant replied with a mighty ‘No!’

And so, the two their weapons did employ,

Contesting fiercely, trading blow for blow.

The giant’s club made the Count’s sword seem a toy,

Yet, without describing all the ebb and flow,

Of the fight, the Count troubled him so sore,

He yielded, crying: ‘Ah, I can no more!’

Book I: Canto V: 66-69: And climbs the cliff to question the sphinx

Thus, the lad was saved by Count Orlando,

And soon returned to his weeping father.

The pilgrim drew a cloth, as white as snow,

From his pouch, and a book did uncover,

That with gold, and bright enamel, did glow,

Which he’d hidden there, a precious treasure.

And then he said, turning to Orlando,

‘Sir knight, I can’t repay the debt I owe,

For a lifetime would prove insufficient

As would, indeed, my power to do so.

Yet, please, accept this tome (wise, and ancient)

Of wondrous virtue, for its pages show

The answer to every riddle, present

Or past; all, that is, that a man need know.’

‘Now, farewell!’ said he, handing him the book,

And so departed, with a thankful look.

Count Orlando stood awhile, lost in thought,

Then, gazing at the stony cliff above,

Determined to ascend it, for he sought,

To view the wondrous creature there, and prove,

The truth of the old pilgrim’s strange report,

That the doubt in his mind she could remove,

For, to this question, he’d know the answer:

Where, on Earth, he might find Angelica.

Safely o’er the dark bridge he did clatter

For the giant no objection now did show;

Not desiring more of Durindana,

He opened, thus, the gate to Orlando,

Who climbed the cliff; high above the water,

Then through a gloomy tunnel he did go,

To attain the place where that strange creature

Crouched, in silence, on a mighty boulder.

Book I: Canto V: 70-75: He fails to unravel her riddles and slays her

She had the smiling face of a maiden,

Above a lion’s breast; and golden hair;

A wolf’s teeth behind her lips were hidden;

She’d eagle’s talons, the arms of a bear,

The body, and the tail, of a dragon,

And wings that a peacock’s hues did share.

And she beat hard with her tail on the rock,

Its harsh and stony darkness to unlock.

When the monstrous creature saw the knight

She fanned her open wings, and coiled her tail,

Hiding all but her fair visage from sight;

A cavern yawned behind that feathery veil.

Count Orlando posed his question, outright:

‘Amidst strange lands, where foreign tongues prevail,

From the icy poles to the equator,

Night’s dark to light, where dwells Angelica?’

In sweet speech, that most subtle beast replied,

Responding thus to Orlando’s question:

‘She, that torments your mind so, may be spied

Near Cathay; Albracca’s her location.

And now you must answer me,’ she sighed,

‘What creature walks with purposeful motion,

Without feet? And what other do we see

Using four, and then two, and later three?’

The Count pondered, seeking to unravel

Her strange questions, but then, without reply,

Quite unable to solve either riddle,

Drew Durindana, and raised it on high.

The Sphinx and he began a fierce battle,

As she about his head commenced to fly,

Menacing him, striking with tail and claw,

Though such attack his enchanted hide bore.

If his flesh had not been charmed, all over,

As indeed it was, then that precious knight,

Would have suffered wounds to back and shoulder,

Arms and chest, in that most furious fight.

His pride was hurt, and fuelled his anger,

For the blows she landed were scarcely light.

He waited his moment and, with a spring,

Leapt up, as down she swooped, and clipped a wing.

The monster screeched, and earthwards did sail,

Her cry echoing all about the place.

About Orlando’s legs she coiled her tail,

And gripped his shield with her claws, for a space,

In a last vain attack, one bound to fail,

For he struck, while still caught in her embrace,

Pierced her gut and, struggling free of his foe,

Hurled her, from the cliff, to the ground below.

Book I: Canto V: 76-77: Though the book held the answers to her questions

The Count descended and located his steed,

Then took to the road, urged on by passion,

Though wondering, as he galloped o’er the mead,

About the answers to her dual question.

He thought of the palmer’s book, its screed

Held the riddles, no doubt, with their solution.

‘I forgot the thing, so was forced to fight,

Yet perchance God thought twas only right.’

Opening the tome, to all the creature

Had asked he now sought the true solution.

He found that it was the seal, whose nature

Is to walk on the sand, its fins in motion.

There too we human beings did feature,

That on all fours make infant progression,

Yet when we cease to crawl, two feet we see

Suffice, though, with a stick, the old make three.

Book I: Canto V: 78-83: Orlando fights the giant who guards the Bridge of Death

Now, while reading he came to a river,

A dark torrent, twas both fearsome and deep,

But lacked any means to cross the water,

While its banks were slippery and steep.

Hoping some passage o’er to discover,

His way along its border he did keep,

And saw a giant, on a bridge, on high:

Which bold Orlando approached, by and by.

When the giant caught sight of him, he cried:

‘O wretched knight! It seems an evil fate

Has brought you here to me, in all your pride!

This is the Bridge of Death; and soon or late,

All must come here; the paths on every side

Twist and wind, but ever lead to its gate.

There’s no escaping it, for by and by,

Upon this bridge, one of us two must die.’

This giant, who was the bridge’s guardian,

Was named Zambardo, and mighty was he.

His brow was two feet high, in proportion

Was his body, or all that one could see,

For he was armoured, a hill in motion,

And held a metal club, huge and heavy,

And from the club five iron chains did fall,

And attached to each was an iron ball;

Each such ball was twenty pounds in weight.

From head to foot a serpent’s hide he wore,

A complete defence neath his mail and plate.

A sheathed scimitar upon his left he bore.

Worst of all, a net he’d hidden, near the gate,

Such that, when some knight battled there before

The Bridge of Death, howe’er bravely he fought,

In its strong mesh he would, at last, be caught.

This net was invisible, neath the sand;

He could trip it, with his foot, as he pleased,

And once he’d done so, take the web in hand,

Then, to the river, drag the knight he’d seized.

No escape was there from what he’d planned;

With death alone his captives’ torments ceased.

Not knowing this, Orlando dismounted,

And approached the bridge, all fear discounted.

Armed with his shield, he gripped Durindana,

With as close an eye on his enemy

That seemed large and fierce enough, as ever

One might keep watch on a little baby.

A hard fight followed, with this great creature,

But, of that, you will hear no more from me,

In this canto; twas so hard to prevail,

I’ve need of rest, ere I resume the tale.

The End of Book I: Canto V of ‘Orlando Innamorato’