Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXVII: The Tale of Marganor

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

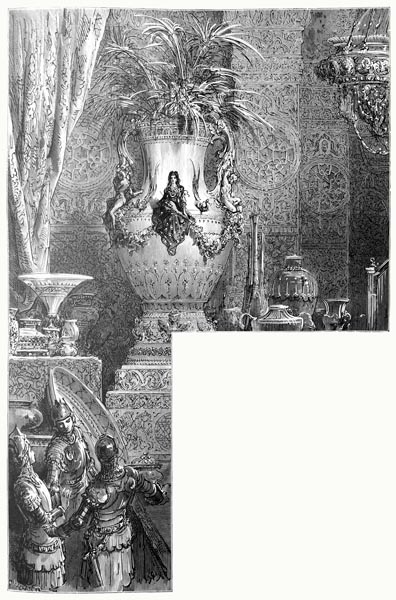

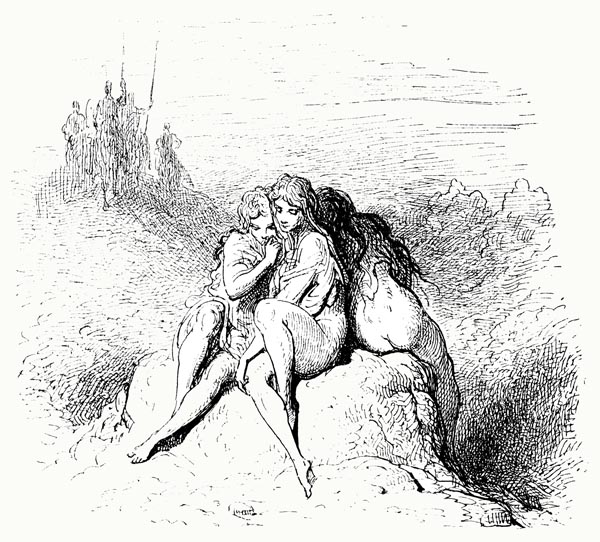

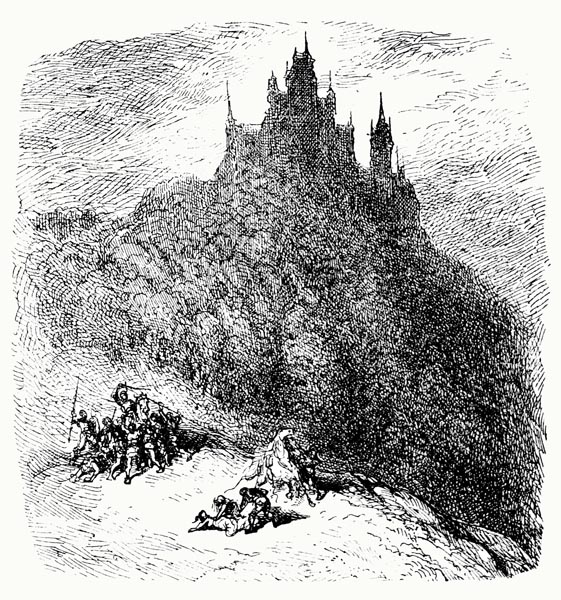

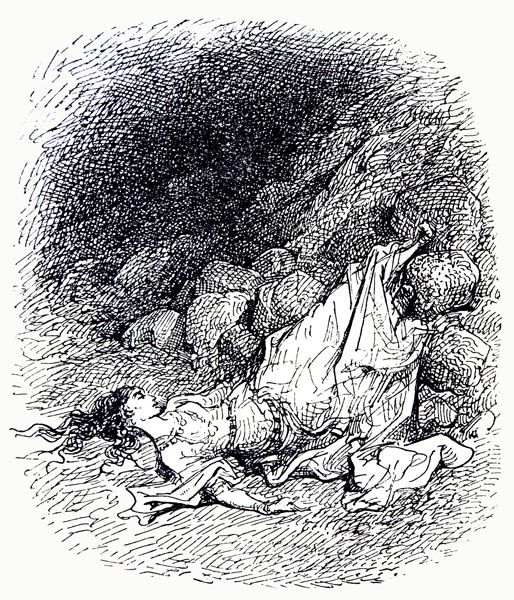

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXVII: 1-8: Ariosto in praise of women’s talents

- Canto XXXVII: 9-14: Of Francesco II Gonzaga, Isabella d’Este and others

- Canto XXXVII: 15-24: Ariosto praises Vittoria Colonna, and honours all women

- Canto XXXVII: 25-29: The three warriors come upon Ullania and two other ladies

- Canto XXXVII: 30-34: They set out to avenge the wrong done them

- Canto XXXVII: 35-43: The village of women

- Canto XXXVII: 44-47: The history of the tyrannical giant Marganor

- Canto XXXVII: 48-50: Cilander errs and is slain

- Canto XXXVII: 51-56: Tanacro slays Olindro and seizes his wife Drusilla

- Canto XXXVII: 57-60: She plots revenge

- Canto XXXVII: 61-65: She devises a means

- Canto XXXVII: 66-69: And achieves her aim

- Canto XXXVII: 70-74: She curses Tanacro

- Canto XXXVII: 75-79: Marganor wreaks havoc in his grief

- Canto XXXVII: 80-85: And banishes the women

- Canto XXXVII: 86-91: He captures Drusilla’s aged servant

- Canto XXXVII: 92-97: Who is freed by the three warriors

- Canto XXXVII: 98-102: Marganor is unseated and his men dispersed

- Canto XXXVII: 103-106: The people approve of Marganor’s downfall

- Canto XXXVII: 107-111: He is handed over to the crone

- Canto XXXVII: 112-114: The warriors free the three kings

- Canto XXXVII: 115-120: A new law is framed

- Canto XXXVII: 121-122: The company depart

Canto XXXVII: 1-8: Ariosto in praise of women’s talents

If, in order they might other gifts acquire,

(For Nature grants nothing without study)

Courageous women, night and day, aspire

To win, through great diligence, mastery

Of many an art, grant works we admire,

And with much labour gain the victory,

They must be equipped for every mortal

Effort that renders virtue immortal;

And if they their own selves could praise,

And, thus, be known to all posterity,

Without begging aid, as they must these days,

From male critics filled with hate and envy,

That hide the good they find in them, always,

Yet all the ill they hear repeat gladly,

To such glorious heights would mount their fame,

As ne’er perchance was reached by any name.

Tis not enough for them that mutual aid

May render them glorious to a world,

That does it best to see their faults displayed,

And keep them prisoned in some netherworld,

Such that they cannot rise from out its shade;

Rather it sinks them, banners ne’er unfurled;

As did the ancients, as if glory won

By a woman dimmed theirs, as mist the sun.

But hand or tongue ne’er possessed the power,

By foolish speech, by penning some ill page,

(Though both the tides of ignorance empower,

And diminish the fine arts, in this blind age)

To eclipse women’s glories for an hour;

They still remain to light our heritage,

Though they may fail to reach their proper height,

Nor reach the regions augured by their flight.

Not only Harpalyce, Queen Thomyris,

Penthesilea, and Camilla,

And Dido who crossed the sea, in peace,

To found, from Tyre, Carthage in Libya,

Zenobia, who saw her power increase,

In India, Assyria, and Persia,

And some further few, were truly worthy

Of, through arms, gaining eternal glory.

For brave women were strong, and chaste, and wise,

Not in Greece and Rome alone, but where’er,

From far India to our Western skies,

The Sun sheds brightness from his golden hair,

Their virtues, honours, hid so from our eyes

That scarce one in a thousand names we share

Amongst ourselves; because they, in their day

Had false and envious, chroniclers, I say.

Yet, rest not, bold women, that glory so;

Follow your path, ever your aims pursue,

Nor pause a moment on the road you go,

For fear of failing of the honours due;

Though good lasts not forever, as we know,

Still, the ills of this world must perish too.

Ignored, to date, within the written page,

It yet may champion you, in this our age.

Marullus and Pontano, ere now, declared

For you, with the Strozzis, father and son,

Capello, Bembo, Castiglione who’s shared

With us the courtier’s goal, lost or won;

Luigi Alamanni, and those two, paired,

Beloved of Mars and the Muse bar none,

Born of the line that reigns in Mantua,

That Mincio cleaves, and three lakes border.

Canto XXXVII: 9-14: Of Francesco II Gonzaga, Isabella d’Este and others

The one, besides his wish to honour you,

And respect, nay reverence, you likewise,

Makes Parnassus, and Mount Cynthus too,

Sound with his praise of you, to reach the skies.

The love, the faith, the mind forever true,

When threats of conflict, and of war, arise,

That calm spirit Isabella has shown,

Have made him more your champion than his own.

Such that he never wearies of praising,

And honouring you, in his lively verse,

And if others censure you in anything,

None seems swifter your defence to rehearse.

For no knight in this world is more willing

To yield his life for virtue (and his purse).

Material for others’ pens he gives,

While, in his writings, others’ glory lives.

And he’s worthy of a lady so blessed

(Blessed with every virtue that may be

Found in any woman of East or West,

Though none can equal her in constancy)

A pillar of support to him, possessed

Of disdain for Fortune’s inconstancy,

She’s worthy of her lord, as he of her,

No truer match, here, could e’er occur.

New trophies now adorn the Oglio,

For he afloat, ashore, midst fire and sword,

Has scattered many a well-penned folio,

To swell the river’s envy of its lord.

And then, Ercole Bentivoglio,

To you, with his clear note, praise doth afford,

Renato da Trivulzio, my Guidetto,

And Molza, blessed you claim by Apollo;

And Ercole, the Duke of Carnuti,

Alfonso d’Este’s son, who spreads his wing,

And soars, and trills so harmoniously,

Praising woman to the skies in everything;

With my lord of Guasto, who not only

Yields such as a thousand Athens might sing,

A thousand Romes, but promises, again,

To exalt your sex forever, with his pen.

And, besides the many alive today,

Who granted you, and grant you still renown,

You yourselves may exalt yourselves, I say;

For many, laying silk and needle down,

Have accompanied the Muses, to allay

Their thirst at Aganippe’s spring (not drown),

And shall do so; and, thus, your works we need

More than you do our efforts, I’d concede.

Canto XXXVII: 15-24: Ariosto praises Vittoria Colonna, and honours all women

If I were to give a full account of these,

Each and every one, and do them honour,

More than one folio I’d need, and cease

To speak of aught else in my cantos ever.

While if with five or six I sought to please,

I’d rouse all the rest of them to anger,

What then? Shall I pass all the others by,

Or bring but one alone before your eye?

I shall choose one, and such a one I’ll choose

As quells all envy and in such a manner,

That no one else, thereby, shall I bruise,

By praising her alone and none other.

She has not yet gained immortality,

Through her sweet style (I know none better)

Yet she, more than any of whom you write,

Or speak, will escape Death’s eternal night.

As Phoebus adorns his gleaming sister

More, and lends her orb a brighter fire,

Than he does Venus’ orb or some other,

That moves on high with the heavenly choir,

Or shines alone, so (as Apollo) ever,

The one of whom I speak he doth inspire

With greater eloquence, and grants such power,

That a second sun illuminates our hour.

Vittoria is her name, and, fittingly,

She was born midst victories, while she

Deserves many a triumph and trophy,

Preceded (or followed) by Victory;

One like to Artemisia, who nobly

Honoured her Mausolus, for thus we see

Tis finer, more beautiful, to raise his vault

On high, whene’er a man we would exalt.

If Laodamia, if Porcia,

If many a faithful wife, desiring

To join their dead spouse (Argia,

Arria, Evadne) are deserving

Of praise, then how much more Vittoria,

That hers, from Lethe, and the encircling

Styx (that nine times about the shades winds tight)

Despite the Fates and Death, draws to the light!

If Macedonian Alexander

Was envious of proud Achilles’ fame,

How he’d envy, Francesco di Pescara,

Were he living now, your glorious name,

While your chaste wife, so dear to you, ever

Sings the eternal honour due that same,

Such that your virtue, through her, so sounds

No clearer trumpet from the skies resounds.

If all there is to tell, and all that I’d say

Of that lady, I sought to pen, indeed

Long might I do so and yet leave alway

A large part still untold; and I have need

To save my errant tale from more delay,

And to Marfisa and her comrades speed,

Whom, I promised you, I’d seek to follow,

If you but lent an ear to this canto.

And now you are here, and all attention,

Since I’d not break my promise, I’ll delay

Any further praise of her, nor mention

Her again, here, though she needs not, I’d say

Any aid from verse of my invention,

That herself the debt can readily repay,

Verse with which I but sate my own desire

To praise and honour one whom I admire.

Many a woman worthy of story,

I claim, dear ladies, every age can show,

And yet, through many an author’s envy,

Unknown, those paragons to death did go;

Yet shall no more, since, for posterity,

Your virtues you shall sing, so all may know.

Had those two warrior-maids owned the skill,

Word of their prowess had spread wider still.

I speak of Bradamante and Marfisa,

Whose great deeds and victories I labour

To bring to light though, it seems, as ever,

Of nine in ten I know naught, yet honour

Those I find, and willingly uncover

Many that are hid, in my endeavour

To please you, dear ladies, that I might prove

Loyal to those whom I admire and love.

Canto XXXVII: 25-29: The three warriors come upon Ullania and two other ladies

Ruggiero, was in the act of leaving

As I said; he’d plucked his sword from the tree,

Which remained still quivering and shaking,

But looked much as it had previously,

When a loud cry, not far distant, sounding

From the vale made him pause suddenly;

Then, with the warrior-maids, he went at speed

Towards it, bringing aid in time of need.

As the three advanced, the cries grew louder,

While they heard the words of woe more clearly,

Finding three women, as they rode further,

Making their lament, and clothed most strangely,

Their skirts sheared to the waist, the shearer

Having treated them most discourteously.

Not knowing how better to hide their state,

They sat upon the ground, disconsolate.

Just as Erichthonius, Vulcan’s son,

Who sprang from the earth, without a mother,

Whom Minerva saw nursed, with care, by one

Aglauros, Cecrops’ over-bold daughter,

Sat in a cart he’d built, and from the sun

Hid his ugly feet, so, in like manner,

Those three maids, seated, kept concealed,

That which is seldom to the world revealed.

At that outrageous and most shameful sight,

The warrior-maidens, as they drew near,

Blushed, their faces like two roses, bright

Of hue, that in Paestum’s gardens appear,

Bradamante drawing closer, saw outright

That Ullania was one, that fact was clear,

Ullania, who’d been sent from the Lost Isle,

To France, and had journeyed many a mile.

She recognised the other two no less,

Ullania’s companions then as now,

Though the envoy herself she did address,

Being the noblest, though with troubled brow,

Demanding who, with utter wickedness,

And scorning decency all must avow,

Had exposed what Nature has concealed,

And their secrets to all the world revealed.

Canto XXXVII: 30-34: They set out to avenge the wrong done them

Ullania knew twas Bradamante,

By her voice, and by her insignia,

She that but a few days previously

Had overthrown those three kings before her.

She told how the folk, unmoved by pity,

In a nearby town, had brought them bother,

Not only caused them harm and injury,

But shorn away their clothes as she could see.

She knew not where the golden shield was gone,

Nor, the three kings, who’d kept her company

And guided her through lands here and yon,

Whether they’d died, or lost their liberty.

And said the three of them, had thereupon,

Journeyed on foot, though twas pure misery,

To report the outrage to Charlemagne,

Who’d avenge both the insult, and their pain.

The warrior-maidens’ faces, as she told

Her tale, were robbed of their serenity,

As was Ruggiero’s who though fierce and bold,

Yet possessed a heart attuned to pity.

They forgot all but the wrong she did unfold,

And without her asking, of chivalry,

Resolving to avenge this wickedness,

Sought the road to the castle, and redress.

With one accord, it seems, they had removed

Their surcoats, moved by pity and concern,

The which were most well-suited, as it proved,

To clothing the fair maids, whose cheeks did burn.

Bradamante, who plainly disapproved

Of their being seen on foot on their return,

Placed Ullania before her, while so,

With the two, did Marfisa and Ruggiero.

Ullania pointed out to Bradamante

The nearest path to the keep, while they rode;

As, promising to wreak vengeance promptly,

She, in turn, comfort on her ward bestowed.

They left the dale, and by a way most weary,

Their horses burdened by the double load,

Ascended slowly, and, while it was light,

Sought to find a fitting lodging for the night.

Canto XXXVII: 35-43: The village of women

Upon those mountain heights, harsh and steep

They found shelter, and a bed, till the morn,

In a village somewhat distant from the keep,

And dined on such as poor folk’s boards adorn.

They looked about them, ere they sought to sleep,

And found that all were women there; timeworn,

Middle-aged, or younger still, as if some ban

Permitted not one solitary man.

No greater wonder Jason, and the crew

Of Argonauts who formed his company,

Felt, gazing on those women who once slew

Their husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, when he

Touched on Lemnos’ rocky isle (but two

Males surviving there, in all that country)

Than did Ruggiero, and his company, feel

At the scene their night’s lodging did reveal.

The warrior-maidens sought some fresh attire

For Ullania, and the maidens with her,

Which, though mean, might at least prove entire,

And such was brought their limbs to cover.

He, of one seeming wisest, did enquire,

Where their men were, none could he discover,

And asked her what the cause of this might be,

While she answered him most courteously:

‘That which perchance seems marvellous to you,

A place so full of women, and no man,

Is a punishment to us and grievous too,

That live here sorrowing and under ban.

For to deal us greater harm, and pain anew,

Our fathers, husbands, sons, every man,

Have long been parted from us, cruelly,

At the pleasure of our lord; a tyrant he.

And this savage has ordered us confined

On these heights, yet but two short leagues away

From his land, to harsh exile thus assigned,

Banned from where we saw the light of day;

And our men are to death or worse resigned,

Threatened with torture if they should stray,

Should seek to visit us, or we offer

To receive them, and to grant them shelter.

He’s an enemy to us, one and all,

Who’ll have us no nearer than I’ve said,

Nor permits a single female in his hall,

As if a woman’s face might strike him dead.

Autumn’s leaves twice already we’ve seen fall,

To be replaced with others in their stead,

Since he was possessed by this mad whim,

With not a one here that can counter him:

For the folk here fear him worse than death,

And added to his evil will, and nature,

He could slay us with but a single breath,

Since this tyrant is a giant in stature,

While his sex acts much like a shibboleth,

All who possess it not are in danger.

Stronger than a hundred men, his anger

Is worse towards any female stranger.

If your honour, sir, and that of those three,

That are in your keeping, is dear to you,

‘Twould be safer, as far as one can see,

To leave this, and another path pursue.

It leads to his tower, well-known to me,

And a most savage use he puts it to,

That brings lasting shame and woe, say I,

On every knight and dame, that passes by.

Than Marganor (such is the villain’s name,

The lord and tyrant of that evil keep)

Not even the monstrous Nero has claim

To be crueller, nor others dyed as deep

In human blood; for he thirsts for that same,

(Woman’s most) as wolves for the lives of sheep,

Dealing shamefully with all women led,

By their ill fate, to seek, there, board and bed.’

Canto XXXVII: 44-47: The history of the tyrannical giant Marganor

Ruggiero, and the warrior-maids, irate,

Asked her what had brought about his rage.

And begged her, of courtesy, to relate

This history that now adorns my page.

‘The castle’s lord was from an early date

Fierce and inhumane, yet at that stage

His evil heart was ever well-concealed,

And twas long ere his baseness was revealed:

For, while,’ she said, ‘his two sons were alive,

Two fine youths who were quite unlike their sire,

(Since they loved strangers and did ever strive

To deny every false and cruel desire)

Courtesy and good manners there did thrive,

Pleasant customs and noble deeds; his ire

The father suppressed, and e’er did treasure

His sons, and indulged their every pleasure.

All the knights and ladies that passed by

Were welcomed with such grace and courtesy,

Every one departed conquered thereby,

Won by the kindly brothers’ chivalry;

In this the youths shared equally, say I,

Ordained to the sacred order, mutually.

Cilander one, Tanacro his brother,

Each noble, strong, and bold as the other.

Both were worthy of their fame, and they

Would deserve both praise and honour still,

If the pair had not rendered themselves prey

To that desire we call love, each lad’s will

Was seduced from the right and proper way,

Drawn into folly’s maze, to error’s mill,

And all the wealth of good they had done

Was corrupted in a trice, ere they’d begun.

Canto XXXVII: 48-50: Cilander errs and is slain

An imperial knight of Greece came to court,

And brought his lady there for company,

Of learned ways, and as lovely, in short

As any man might wish for in this country.

Cilander fell in love, was truly caught,

And was like to die unless he, suddenly,

Possessed the wife, for, if she should depart,

He’d surely perish of a broken heart.

As naught could be won by prayer or plea,

He was disposed to take the girl by force,

And, to a path by the keep, armed fully,

Where both of them must pass, he had recourse.

Through recklessness, and amorous folly,

He’d given little thought to his mad course,

And, when he saw them, wildly did advance,

To attack the knight, bold lance against lance.

He thought to down the man with that first blow,

And seize the woman, and the victory,

But the Greek, who’d mastered many a foe,

Shattered his plate like glass, instantly.

To the father sped the tidings of woe,

Who had him borne back on a bier, promptly,

And finding he was dead, laid him beside

His buried ancestors, then wept and sighed.

Canto XXXVII: 51-56: Tanacro slays Olindro and seizes his wife Drusilla

And yet guests were made welcome as before,

And lodged as graciously, for Tanacro

Was as courteous as his brother, if not more,

And the same graciousness did ever show.

There came that year, from a foreign shore,

A noble baron, and his wife also,

He marvellously brave, she full of grace,

And, beyond all description, fair of face,

And as honest and true as she was fair,

And worthy of honour, and of praise.

The baron to a famous name was heir,

And brave as any heard of in those days.

Twas fitting to such valour that so rare

And rich a prize was at his side always.

Olindro he, lord of Lungavilla,

While his fair lady was named Drusilla.

No less for her did young Tanacro burn

Than bold Cilander had for the other,

Whose errant desire had seen him earn

An end that was both tragic and bitter;

No less than he, Tanacro chose to spurn

The laws of hospitality, forever

Holy and sacred, sooner than endure

A deep longing that must his death ensure.

Yet with the example of his brother

Before his eyes, and his desperate end,

He thought to make the abduction surer,

Such that this Olindro might not defend

His wife or take revenge; lost forever

Was the courtesy he’d formerly extend,

Virtue, that kept the tide of Vice at bay

That sunk his father in its depths alway.

A score of armed men, in the dead of night,

He gathered, and, far from the castle keep,

Deployed them in the caverns, left and right

Of the road, while all else was drowned in sleep.

He blocked Olindro’s way when it was light,

Who rode the path beneath the mountain steep;

The baron fought hard to prevent the wrong,

Yet was robbed of wife, and breath ere too long.

With the husband slain, the lady was led

Captive, and so overwhelmed with sorrow,

Wishing that she herself had died instead,

That she begged Tanacro to end her woe.

Then, crying out that she would join the dead,

She leapt from a ledge to the vale below.

Death was denied her, but as dead she lay,

Her head and limbs sore damaged on the way.

Canto XXXVII: 57-60: She plots revenge

She could not to the castle thus repair,

Except on a stretcher borne by his men.

He had the doctors tend to her with care,

Fearing his prize might yet be lost again.

While she was healed, he thought to prepare

To celebrate their marriage, as and when

She was well, wishing her to bear the name

Of wife not mistress, and her true place claim.

Tanacro had no other thought nor wish,

Nor other care, nor spoke of aught beside

Save that he’d wronged her deeply in this,

On him lay all the blame, and thus he tried

To amend his fault, himself would punish,

Yet all in vain, the more he sought a bride

And laboured to please her, the more that she

Longed to slay him, hating most vengefully.

But hatred failed to blind her to the fact

That if she wished to strike the fatal blow,

She must dissimulate, prepare to act,

Yet her true feelings she must never show;

But the contrary part, in every way, enact,

(To that of a plotter gainst Tanacro)

And lead him to believe that her first love

She had forgot, and did his suit approve.

She wore a tranquil mask, but inwardly

Swore vengeance; to little else gave care.

Sundry plans she now conceived, some that she

Accepted, then rejected, some most rare

Yet doubtful of success and, finally,

Resolved to die that he her death might share;

For how better to avenge Olindro

Than by dying, yet while slaying his vile foe?

Canto XXXVII: 61-65: She devises a means

She wore a face of joy, and thus she feigned

A fervent longing that they soon might wed,

And all delay to the course now ordained

She overcame, e’en though her heart nigh bled.

To adorn herself most richly she deigned,

(Olindro seemed forgotten and long dead)

While insisting that the ceremony

Should be performed as in her country.

A false custom she devised, devoid of fact,

Yet said that, in her land, all was done so,

While she gave her every thought to the act

Of vengeance, by which to slay Tanacro,

And thought only of how she might enact

Her plan, by a means she alone could know.

She said she wished to marry in the manner

Of her own folk, and explained the matter:

The widow that would take a husband, there,

Before she approached her spouse-to-be,

Would placate, with solemn mass and prayer,

The dead shade, lest it proved her enemy;

And would to that holy temple, thus, repair

Where lay her dead husband’s tomb, and she,

When the proper rites were duly over,

Then received the ring from her new lover.

Amidst all this, the priest, having brought,

A flask of wine with him, in due order,

With orisons, devout and fitting, sought

To bless and fill a chalice with the liquor,

Handing them the vessel, though he ought

If the solemn task were performed as ever,

To bear it first to the bride, who would sip

The contents ere it touched Tanacro’s lip.

The latter, who gave not a single thought

To the true reason for her insistence,

Said, as long as it achieved, in short,

Their marriage, and ensured they issued thence

As man and wife, her pleasure he but sought,

Seeing not that revenge for his offence

Was the sole object that possessed her mind;

To her consuming passion he was blind.

Canto XXXVII: 66-69: And achieves her aim

Drusilla had an old crone in her service,

Seized with her, that with her had remained.

She summoned her, and then shared all this,

So, none could overhear, as she explained:

‘Prepare a sudden poison, whose malice

I know you have the secret of; once strained,

Fill a phial with it, for I’ve found a way

This wicked son of Marganor to slay,

And no less save myself, and you also.

Of that I’ll tell you later; now depart.’

The old woman left; and when all was so,

Returned to the palace; while, for her part,

Drusilla had filled a flask, neck to toe

With sweet wine of Candia; now, with art,

She mixed the fatal poison, gainst the day

When she was to be wed; nor would delay.

On the day ordained, to the church she came,

Adorned with gems, and in rich garments dressed,

Where a marble tomb, worthy of his name,

For Orlindo, had been built at her request.

A solemn mass was sung, to mark his fame,

Many a knight and lady, midst the rest,

Attended, and Marganor, happier

Than of late, with his friends there did gather.

Once the holy rites had been completed,

And the priest had, devoutly, blessed the wine,

He filled a chalice, and the bride he greeted,

With the golden cup, as was her design.

Drusilla sipped, then (scarcely depleted,

Was the chalice, twas her intent, in fine)

Handed it to her spouse with joyful face,

Which he took, and downed, draining it apace.

Canto XXXVII: 70-74: She curses Tanacro

Returning it to the priest, he, blithely,

Opened his arms to embrace Drusilla,

But her calm sweet expression had, swiftly,

Changed to one of fierce disdain and anger.

She thrust him back, scorning him completely,

And with ire and menace in her manner,

In a dreadful voice, with fiery eyes and face,

Cried: Traitor, away now; keep your place!

Shall you have joy and solace then, of me,

While tears are mine, and torment, and deep woe!

Vile death, from out my hand, I grant to thee,

Twas poison laced the cup, as you shall know.

It grieves me that too swift a death you’ll see,

For I’ve ne’er heard of punishment so slow,

So harsh a death as that I’d wish on you,

To equal your grave sin; such is your due.

I grieves me that I could not live to see

The perfection of my sacrifice complete.

Had I wrought all, ere I thus set you free,

That I desired, twould smack less of defeat.

Yet may my own sweet consort pardon me,

And approve my true intent, if not the feat:

Lacking the power to compass all I would,

Yet I have wrought the utmost that I could.

The punishment I failed to grant you here,

That might have matched the depth of my desire,

I trust your shade will suffer many a year,

(While I look on) scorched by eternal fire.’

And then with joyous face it would appear

Yet clouded eye, her gaze she lifted higher,

And cried: ‘Olindo, take this victim’s life,

Receive this gift, from your avenging wife;

And beg grace for me, of the Lord above,

That I may dwell with you, in paradise.

If He should say that only those that prove

Worthy of merit, come before His eyes,

Say such am I; in honour of your love,

This evil wretch, before His altar, dies.

What greater merit could there be than this,

To end such vicious sinfulness as his?’

Canto XXXVII: 75-79: Marganor wreaks havoc in his grief

Her life now ended, as she ceased to speak,

And yet her face still seemed suffused with joy,

At having slain the man (such did she seek)

Who had her husband laboured to destroy.

Whether Tanacro, who the harm did wreak,

Followed or preceded her, as her envoy,

To Death, I know not, yet, I must believe,

He died first, that most poison did receive.

Marganor, who saw his remaining son

Slump to the ground, and die in his embrace,

Was like to die himself, well-nigh undone

By the grief that pierced him in that place.

Two sons he had possessed, and now had none;

While two women had thus destroyed his race,

The death of his first son caused by the one;

Of the second by what this wife had done.

Love, pity, deep disdain, grief and anger,

With the desire for death, yet vengeance too,

Agitated the now-childless father,

Who moaned, as wind and wave in winter do.

Towards Drusilla, to avenge the murder,

He hastened now, yet found but death anew,

And, lashed by burning hatred, pain his lot,

Sought to offend her corpse that felt it not.

As a snake, pinned by a stick to the sand,

Will fix its jaws upon it, writhing madly,

As a mastiff, seeing some missile land,

Thrown by a passing lad, gnaws it fiercely,

Worries at it in rage, and there will stand,

Taking vengeance on a stone, uselessly,

So Marganor, worse than a dog or snake

Marred the bloodless corpse, for revenge’s sake.

Finding his lust for vengeance unfulfilled

By this foul abuse of the voiceless dead,

He turned upon the women there, and killed

One, then another, with his sword, instead,

Mowing us down, as his fierce anger willed,

Like to dry reeds scythed in some marshy bed.

Few could escape; he struck, and struck again;

A hundred were wounded, and thirty slain.

Canto XXXVII: 80-85: And banishes the women

Marganor filled his people with such fear

That not a man there dared to meet his gaze;

The women, with the weaker of them, near

Dead with fright, fled their separate ways.

Then, by plain force, his friends, it would appear,

Restrained his rage (naught else this man obeys)

And made him to his rock-bound castle go,

Leaving tears and desolation there below.

The depth of his anger yet remaining,

He determined to exile all the women;

His friends there, and the populace praying

That he’d not slay us all, but think again,

While that same day he decreed the thing,

And banished all of us, but spared the men.

He has placed this restriction on us all:

Woe to those that approach the castle wall.

From wives were the husbands separated,

From mothers their sons, and if tis known

That some brave soul visits here, they’re fated

To be denounced to him, for spies he’s sown.

Many have been punished, mutilated

Or slain in cruel ways; we sigh and groan,

For he has made a law, worse ne’er has been,

At least a worse we’ve ne’er heard of nor seen:

Every woman who is found within that vale,

(For some will venture down there, even now)

Must be beaten with sticks o’er hill and dale,

And banished from the land; such he did vow;

Their skirts are sheared, no protest doth avail;

That which Nature hides, shame on their brow,

They must reveal; while if some valiant knight

Accompanies a woman, she’s slain outright;

She, though she’s escorted by a warrior,

Is dragged, by this enemy of piety,

To his sons’ sepulchre, where her murder

Is achieved by his own hand, most cruelly,

A sacrificial offering, while his armour

Is stripped from her champion, and he

For his pains is imprisoned neath his hall,

For a thousand men are at his beck and call.

And furthermore, I say, ere one is freed,

He makes him swear, upon the sacred host:

For as long as he lives, he must concede

That to shun the sex he’ll do his uttermost.

If it seems good to you to scorn his creed,

And display the prowess you seem to boast,

Then draw near the wall, with these maids, boldly,

Prove his strength is less than his cruelty.’

Canto XXXVII: 86-91: He captures Drusilla’s aged servant

The warrior-maids by her words were moved

First to pity, then to scorn and disdain,

And if it had been day, not night, had proved

Themselves against this evil châtelaine;

Thus, when Aurora had once more removed

The darkness, signalling to the stars, again,

That to the rising Sun they must give place,

They armed and mounted, sternness in each face.

Ere departing, they heard a mighty sound

Of trampling hooves, from the vale below,

Such that it drew their gaze, there they found,

At no greater distance than a stone’s throw,

A troop that through a narrow gully wound.

A score perhaps in number, passing slow,

Through the winding ravine in close array,

While others too, on foot, pursued their way.

They led an aged woman on a horse,

(Lined and wrinkled was the face of that same)

In the manner of one whose bitter course

Leads to the gallows, prison, or the flame.

Despite the flow of time, amidst that force,

The women of the village knew the dame

As that crone who’d accompanied Drusilla,

And had assisted her in the murder.

Seized, by the rapacious Tanacro,

Along with the mistress that she served,

She’d distilled the poison, as we know,

That dealt the punishment which he deserved.

She’d then shunned the church; for what must follow

The crone anticipated; unobserved,

She had fled from the village and had, swiftly,

Sought a distant place offering safety.

Marganor had learnt she was hiding

Somewhere in Austria, and he had sought

To lay his hands upon her, desiring

To hang her, or to burn her, at his court.

And finally, with Avarice conspiring

Seduced a greedy baron, richly bought,

Who, to his profit, then, secured the crone,

And sent her to Marganor, for his own,

Tied on a pack-horse, borne to Costanza,

Like a bundle of merchandise, indeed,

And gagged so not a peep issued from her,

Imprisoned in a chest, aboard the steed.

From there, at the bidding of their master,

From whom naught of pity did e’er proceed,

His men had led her there, so that he might

Vent all his rage upon her, and his spite.

Canto XXXVII: 92-97: Who is freed by the three warriors

As the stream that flows from Monte Viso,

Grows to form the River Po, descending,

(Fed by the Lambro, and the Ticino,

And a host of tributaries, unending)

Towards the plains and the sea, even so,

His pride and impetuosity increasing,

Went Ruggiero, raging at Marganor,

While the warrior-maids raged even more.

They burned with such hatred, and such anger

Against the wretch, incensed by his crimes,

That despite his army, and present danger,

They would press on to punish him betimes;

Yet with no easy death; they’d have him suffer,

By pains unknown e’en to those evil climes,

Rather the fiercest torments he should feel,

Prolonged and bitter, wrought with fire and steel.

But first twas right to free the aged dame,

Being led towards her death by that crew.

Loosing the reins, spurring their steeds they came,

Upon them, making short work of them too.

Ne’er had they, who felt the power of those same,

Suffered such mighty blows as from these two,

Thankful, with but the loss of sword and shield,

And the crone, and the horse, to quit the field,

Just as a wolf, that’s burdened with its prey,

When heading for its den, on paths secure,

Meets a hunter with his hounds on the way,

When it had thought all safe, and, safe no more,

Drops what it bears, and swiftly speeds away,

Through the woods, devoid of spoils, as before.

No less swift were that band to quit the dale,

Than the three were to see those wretches quail.

Not only did they leave the crone behind,

And their gear, but many a steed as well,

And from any bank or ledge they could find,

Launched themselves, to escape that dell.

The warriors were pleased, who now assigned

Steeds to the three, that, behind each saddle,

Had been mounted all the long day before,

Burdening their own good coursers sore.

Lightened of their load, their horses bore

Our three to the infamous keep nearby,

Determined the old crone, what is more,

Should see true vengeance wrought with her own eye.

She (fearing lest it ended ill, I’m sure)

Shrieked and wept, vainly seeking to deny

The need for her presence, though Ruggiero

Having seized her, conveyed her on Frontino.

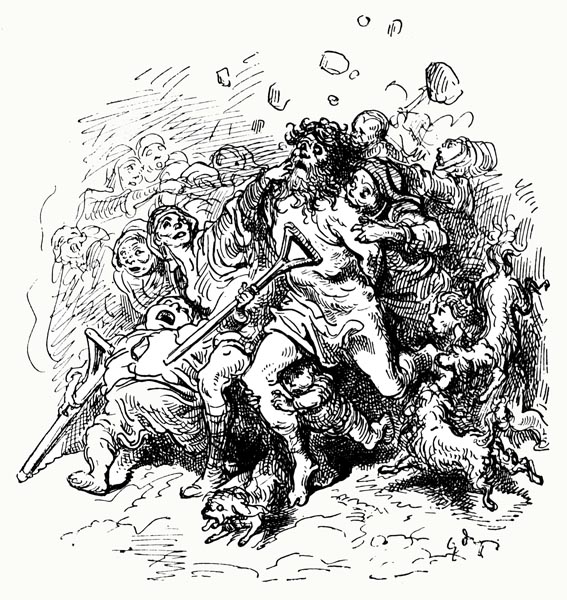

Canto XXXVII: 98-102: Marganor is unseated and his men dispersed

They reached a summit, and from there could see

A town, with wealthy mansions, down below,

With nothing to defend it outwardly,

Since it had neither moat nor wall to show,

In its midst a rock towered, and proudly

On its top stood a keep, supported so,

Fearlessly, our warriors forged ahead,

For twas Marganor’s castle; on they sped,

Yet no sooner had they their entry made,

Than those who kept guard beside the gate,

Placed behind them a solid barricade,

While their exit was in a like, barred state.

Behold Marganor, with a cavalcade

Arrived, and men on foot, armed and irate,

That, briefly and proudly, made them sure

Of the continuance of that vile law.

Marfisa (who had previously agreed

Their plan of campaign with Bradamante,

And Ruggiero) at he who had decreed

That ill custom, spurred her charger fiercely.

Nor her lance, nor her good sword, did she need,

But, as valiant as ever, hammered, bravely,

On this Marganor’s helmet with her fist,

Till, half-dead, his courser’s neck he kissed.

Chiaramonte’s maid had with Marfisa gone,

Nor was Ruggiero’s steed far in the rear.

They, with levelled spears, had soon undone

Half a dozen, and had filled the rest with fear,

One he slew; a paunch, a chest, another one

Clasped his neck, a fifth his head; and then sheer

Through the sixth man’s spine and breast went the stroke

Of his lance, which splintered therein, and broke.

As many as Bradamante touched, she downed,

With the golden lance, to greet the solid stone;

Seeming like lightning, leaping o’er the ground,

Marring all beneath, striking flesh and bone.

The people scattered, some towards the mound

On which the castle stood, some, swiftly flown,

Seeking the plain, church, or home for shelter,

Abandoning the dead, ran helter-skelter.

Canto XXXVII: 103-106: The people approve of Marganor’s downfall

Marfisa, meanwhile, had bound Marganor.

His hands behind his back (to the crone,

She consigned him, one happy to ensure

He was guarded closely, and confined alone)

Then sought to burn the town, or see the law

Repealed, and devout repentance shown,

For its past errors, and a fresh law made

That she would see established and obeyed.

To gain her wish required scant persuasion,

For they feared she might do more than she said,

And lay about her, on the least occasion,

Or burn the town, above the silent dead,

Killing all (while thwarting all evasion)

That to Marganor and his laws were wed.

They’d done what most folk do, all that host,

And obeyed the one that they feared the most.

Since none could place their trust in another,

And none had dared to exercise their will,

They’d seen him banish father or brother,

Steal their goods, and their honour; even kill.

But the heart, silent here, is heard in other

Realms above; God, and all his saints, seek still

The surer judgement, which though oft delayed,

Sees, with harsher punishment, the debt repaid.

Thus, the crowd full, of hatred and anger,

Sought vengeance for each evil word and deed,

As the proverb says: all ran with sudden fervour

To strip the tree the wind has felled; indeed,

Let Marganor’s fate teach every leader:

Evil actions shall their own downfall breed;

To see the wicked punished for their crime

Delights both great and small, in every clime.

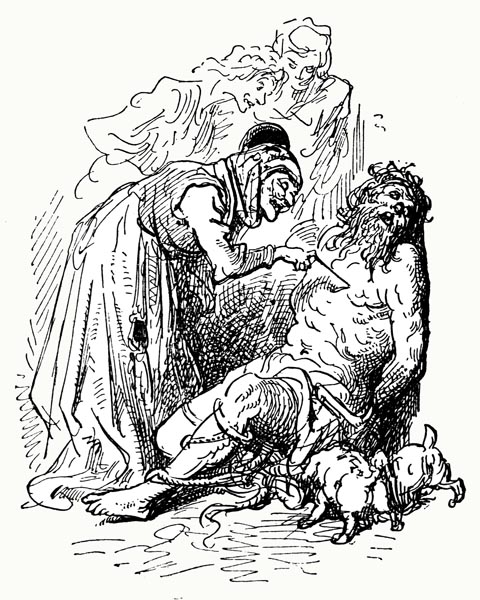

Canto XXXVII: 107-111: He is handed over to the crone

Many a man whose dear wife, or sister,

Or fair daughter, or mother had been slain,

Suppressing his smothered wrath no longer

Hastened to deal the man a world of pain;

While howe’er magnanimous each warrior

None would persuade the people to refrain,

For all three had doomed the villain to death:

Let grief and torment share his final breath.

They gave the wretch, stark naked, to the crone,

And bound so tight that he could ne’er work free,

For she bore such hatred to him, I own,

As e’er one could towards an enemy.

She, to assuage her grief, now made him groan,

Bloodying his flesh, nigh universally,

With a sharpened goad that a village lad

Set in her aged hand, that drove him mad.

Nor did Ullania, or those maidens with her,

Who would not soon forget their bitter shame,

Withold their hands, but one then another,

Bent upon vengeance, sought to hurt and maim.

As great as was their longing, yet the power

To savage him was lacking; all the same,

A needle sank deep and, aided by a stone,

Tooth and nail engendered many a moan.

As a wild torrent, swollen by the rain

And filled with the melting snow, plunges down,

Tearing out rocks and trees, towards the plain,

Flooding the fields, until the ripe crops drown,

And then, at the point where loss exceeds the gain,

Its force subsides, vanished its brief renown,

Until a woman, a child, can pass it by,

Tread where it flowed, and keep their stockings dry,

So Marganor, who’d caused the folk to mourn,

And tremble at the mention of his name.

For one had come to break the tyrant’s horn,

To quench his pride, obliterate his fame,

Until the children, too, put him to scorn,

Tugging at mane, and beard, the lion now tame.

Ruggiero and the maidens turned aside

And to the keep, set on its height, did ride.

Canto XXXVII: 112-114: The warriors free the three kings

The place was yielded them without a fight.

Of all within, much of it rich and rare,

Part they seized, part gave as gifts outright,

To Ullania, and her companions; there,

They brought the golden shield once more to light,

And freed the three kings from that evil lair,

Who’d reached it, as I think I related,

On foot, unarmed, and been incarcerated.

For from the day that brave Bradamante

Had overthrown them, they’d gone unarmed,

Accompanying the Icelandic lady,

On foot, as though their very lives were charmed;

Though who knows if that was better, truly,

Or worse, if they’d see the maid unharmed;

Worse in lacking the means to strike a blow,

Yet better, surely, in not doing so;

For she, like all the other women whom

Armed men had guided to that keep before,

Would have been borne off to the brothers’ tomb,

And there been sacrificed by Marganor.

And death, indeed, is a more final doom,

Than revealing one’s private parts, I’m sure;

Besides, what offset the grief and shame

Was that here the use of force was to blame.

Canto XXXVII: 115-120: A new law is framed

The warrior-maids, ere they rode away,

Called the men together, and made them swear

They’d allow the town’s women to hold sway,

Ruling all matters there, and everywhere;

And would torment defaulters, night and day,

All those that to breach the law might dare.

In short, whatever, elsewhere, men controlled

The women would handle there, young and old;

And made them promise that no man ever

That came to the castle would be received,

Whether on foot, or mounted on a courser,

Nor granted lodging, nor his needs relieved,

Unless he swore, by God above, forever,

(Or stronger oaths if such could be conceived)

To every female he would stand a friend;

And always, from its foes, that sex defend;

And, were he to wed sooner or later,

Once joined in marriage with a loving wife,

He would obey her in every matter,

And be her subject, all his wedded life.

Then Marfisa said she’d return hereafter,

Ere the autumn, bringing pain and strife

If they sought to flout the law so declared,

And burn the place, with not a building spared.

Nor would the company leave, moreover,

Till Drusilla’s corpse, from an evil place,

Had been brought to light, and the sepulchre

That held her husband’s corpse it did grace.

Meanwhile her aged servant, had further

Reddened Marganor, goading him apace,

Only grieving that she lacked the strength

To strike and mar the wretch at greater length.

Beside the church, the warrior-maids beheld

A pillar standing in the market square,

On which this Marganor had felt compelled

To inscribe his mad and cruel law; and there,

As if a victory unparalleled

They celebrated thus, the martial pair,

Hung his armour, helm, and shield, and had traced

The law that the men had now embraced.

The company lingered there, till Marfisa

Might see the work completed in her name,

Replacing that once carved on the pillar

That had doomed all women to death or shame.

Ullania had withdrawn, however,

To replace her clothes, for it could but maim,

She felt, her honour, given what she wore,

Till she was dressed and adorned as before.

Canto XXXVII: 121-122: The company depart

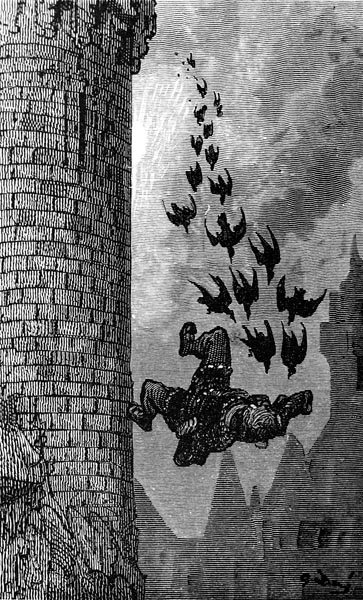

At that place she remained; in her power

Lay the vile Marganor, and she, concerned

That he might escape in some evil hour,

And cause more harm, though now interned,

Had him flung from the summit of the tower,

A leap for which e’en he had never yearned.

Yet speak no more of her and hers, my art,

But tell of the rest, who for Arles, depart.

All that day, and a good part of next morn,

The company rode on, until they came,

To a fork in the road, from which was born

The path to Arles, the other as its aim

Had Charlemagne’s camp; the lovers, torn

Apart once more, a sad embrace did claim,

The maidens sought the camp; Ruggiero

To Arles was gone, and so ends my canto.

The End of Canto XXXVII of ‘Orlando Furioso’