Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXVI: Reconciliation

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXVI: 1-4: Ariosto on Courtesy

- Canto XXXVI: 5-10: The cruelty of the Slav mercenaries at Polesella (1509)

- Canto XXXVI: 11-14: Ruggiero learns his foe is Bradamante

- Canto XXXVI: 15-19: Marfisa pre-empts their encounter

- Canto XXXVI: 20-25: The two warrior-maidens fight

- Canto XXXVI: 26-29: Their contest sparks conflict between the camps

- Canto XXXVI: 30-36: Bradamante attacks Ruggiero

- Canto XXXVI: 37-39: He eventually addresses her

- Canto XXXVI: 40-42: They turn aside to a nearby vale

- Canto XXXVI: 43-46: Marfisa follows, only to be attacked by Bradamante

- Canto XXXVI: 47-50: The warrior-maidens resist attempts to part them

- Canto XXXVI: 51-57: Marfisa turns upon Ruggiero

- Canto XXXVI: 58-62: The voice from the tomb

- Canto XXXVI: 63-66: Atlante tells the tale of the twins’ separation

- Canto XXXVI: 67-69: The three warriors are reconciled

- Canto XXXVI: 70-74: Ruggiero tells Marfisa of their family history

- Canto XXXVI: 75-79: Marfisa exhorts him to avenge their parents

- Canto XXXVI: 80-84: It is agreed he should remain awhile in the Moorish camp

Canto XXXVI: 1-4: Ariosto on Courtesy

Tis fitting that a noble heart should be,

Courteous, it could not be otherwise,

For by habit, as by nature, surely,

It acquires what it nevermore denies.

Tis fitting that a base heart, as we see,

Should ever prove discourteous, likewise

Nature bows to evil, and tis not strange

If the heart forms ill habits hard to change.

The noblest examples of courtesy,

Seldom matched in modern times, are found

Amongst the warriors of antiquity,

While examples of discourtesy abound

Among ourselves, Ippolito, as we see,

Recalling Polesella (whence a mound

Of spoils adorn our churches) where you bore

Those laden galleys captive to our shore.

Every cruel, inhuman deed of the Moor,

The Tartar or the Turk, was there outdone,

(Though tis not the Venetians we deplore,

Who’ve ever proven just, beneath the sun)

By that band of mercenaries we abhor,

Who committed every sin, to evil won.

I’ll not tell of the fires, of which the traces

Remain, that burnt cities and fair places,

Though twas a vile revenge, aimed ever

It would seem, against you; while, at the side

Of the Emperor, at the siege of Padua,

Tis known that you often turned aside,

To quench some roaring flame; moreover,

When the fire was spent, you oft denied,

All attempts to relight it; owing, surely,

To your noble, your inborn, courtesy.

Canto XXXVI: 5-10: The cruelty of the Slav mercenaries at Polesella (1509)

I’ll say no more of that, or their other

Cruel and discourteous deeds, save one alone

A deed that when spoken of, moreover,

Still has the power to draw tears from stone;

Twas that day you gave your men the order

To take the fort to which the foe had flown

Quitting their fleet, in defeat’s shadow,

The auspices ill for them, the morrow.

As Hector, and Aeneas, on Trojan shore,

Fired the Greek fleet, amidst the waves, there, I

A Hercules, an Alexander, saw,

Burning with noble ardour, spirits high,

Spurring side by side, and so far before

The rest that, entering the river thereby,

The latter of the two could scarce fight free,

While leaving the former to the enemy;

Faruffino there escaped, Cantelmo died.

What were your thoughts and feelings, at that hour?

O, Duke of Sora, when your son you spied,

Bare-headed, and in the enemy’s power?

Led aboard ship and, by the river-side,

Beheaded, as you watched, in the flower

Of his youth? I marvel you did not die,

Seeing your son struck dead before your eye.

Merciless Slavs, say whence you brought this mode

Of warfare. In what Scythian land is it the rule

To slay one who’s defenceless? By what code

Do you live, performing an act so cruel?

Was it a crime that he his ardour showed

Fighting for his land? Such is but misrule;

Deprived of light, ill is the world that sees

Tantalus, Atreus and Thyestes.

O cruel barbarians, you that reft the head

From the most daring lad twixt pole and pole,

Twixt farthest India’s shores, and Ocean’s bed,

Where the descending sun is swallowed whole.

His youth and beauty pity might have bred

E’en in some creature born without a soul,

But not in you, whose deeds have now outdone

The Cyclops, or vile Laestrygonian.

No, not the like example could we find

Midst the ancient warriors, whom we study

Who, in victory, were ne’er so unkind,

Possessed by mercy, full of courtesy.

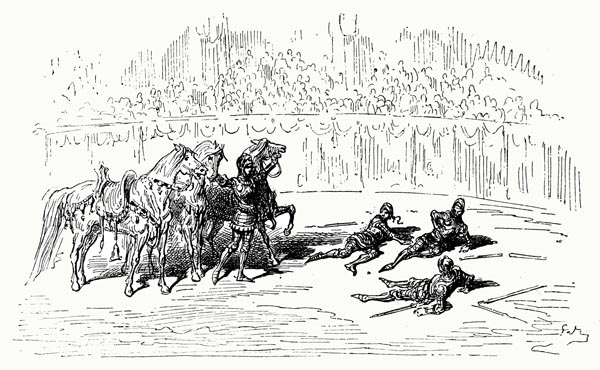

While Bradamante, of like noble mind

Not only had forborne to harm the three

She had unhorsed, but had returned their steeds,

That they might rise again to further deeds.

Canto XXXVI: 11-14: Ruggiero learns his foe is Bradamante

Of that fair, courageous warrior-maid

I have related how she swiftly downed

Serpentino of the Star, and then laid

Grandonio and Ferrau on the ground.

And how a gift of his steed she made

To each warrior, and how, at the sound

Of her summons, Ruggiero to the fight

Had ridden, whom she deemed the finer knight.

Ruggiero met the call most joyfully,

And had his weapons brought, and his armour,

Which he donned before King Agramante,

While wondering who was this warrior

That fought so skilfully, and elegantly,

Wielding the lance with such great valour;

And asked Ferrau, who’d addressed the knight,

If the latter was known to him by sight.

Ferrau replied: ‘Be sure, it is not one

That you have spoken of, ere this, to me.

For I thought, the visor opened to the sun,

Rinaldo’s younger brother I did see;

But now that, with this same, a course I’ve run,

Ricciardetto fights far less skilfully.

I believe this is his sister, whom I hear

Much like to him in visage doth appear.

She is said to be as valiant in a fight

As her Rinaldo, or any other,

And yet, from what I’ve seen, the maid well might

Exceed both her cousin and her brother.’

Ruggiero’s cheeks, hearing this, burned bright,

With that dye with which the sun doth colour

The morning clouds; such now was his hue,

His heart so throbbed he knew not what to do.

Canto XXXVI: 15-19: Marfisa pre-empts their encounter

Stung, and aroused, by the amorous dart,

At this, he felt the living flame within,

Yet while upon his flesh he felt the smart

Of Love’s fire, a chill to his bones did win,

A chill of fear that she might, for her part,

Disdain the love, with which they did begin.

Confused, he stood, uncertain in his mind

If he should go or stay, and lagged behind

The fierce Marfisa, thus, who had desired

To meet this bold warrior in the field.

And being armed (since always so attired,

Clad in armour, next her sword and shield)

And hearing that Ruggiero now aspired

To victory, his lance about to wield,

Thought to pre-empt him there, before all eyes,

Defeat that warrior, and gain the prize.

She leapt upon her horse, and swiftly flew

To where with beating heart Bradamante

Awaited Ruggiero, thinking to

But take him prisoner, striking lightly

With her lance, in whatever might ensue,

Seeking not to wound the warrior deeply.

Marfisa issued from the gate, to war,

Who, on her helm, the phoenix emblem bore,

Either to so proclaim, in her great pride,

Her own unique reserves of bravery,

Or that she’d never seek to play the bride,

Remaining single, bound to chastity.

Bradamante this fresh warrior eyed,

But finding not the one expected, she

Demanded this other’s name, and so heard

Twas she on whom his love he had conferred;

Or rather she believed he had conferred

His love upon this maid, she hated so

That a most painful death she’d have incurred

Rather than fail to avenge her deep woe.

Angered, she wheeled her horse, without a word,

Yet less with longing to unhorse her foe,

Than with her lance to pierce the other’s breast,

And put all thoughts of jealousy to rest.

Canto XXXVI: 20-25: The two warrior-maidens fight

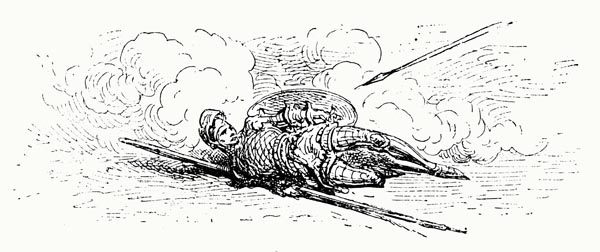

Marfisa was obliged, at her first blow,

To prove if the ground below was soft or hard,

And all unused to being treated so,

Nigh maddened by disdain, at once, on guard,

She rose, drawing her blade upon her foe,

To avenge the stroke while as yet unmarred.

Bradamante, no less proud, called to her:

‘What would you now? You are my prisoner!

Though I show courtesy to others, none

Shall I show to you, Marfisa,’ she cried.

‘Ever, indeed, I hear of you as one

Bedevilled by discourtesy and pride.’

At these words, Marfisa, not to be outdone,

Cried aloud, as does the wind the cliffs abide,

And screamed a reply, all meaning drowned

Such was her anger, in that burst of sound.

With her drawn sword she sought to strike

The knight, or the steed, in breast or belly;

Bradamante tugged the reins, in warlike

Manner, turned, and used her lance, suddenly,

In anger and disdain, thrusting the spike

At her foe, and thus striking again swiftly,

And, though the lance scarce touched Marfisa,

She fell backwards to the ground beneath her;

Yet scarce touched the earth ere she rose once more,

Intent on wreaking vengeance with her blade.

Bradamante couched her lance as before,

And, again, overthrew the furious maid.

Yet though of martial strength she had full store,

Bradamante had not Marfisa stayed,

Upending her, whene’er she would advance,

Had it not been for her enchanted lance.

Meanwhile a band of knights upon our side,

Christian knights I mean, had issued out,

And sped to where each warrior replied

To the other’s strokes in that angry bout;

(Midway twixt the camps, half a mile the ride)

Since their warrior showed such skill throughout;

‘Their warrior’, but otherwise unknown,

Seen to be ‘theirs’ by the emblems shown.

Agramante, Troyano’s generous son,

On seeing them draw near the city wall,

And concerned at all that might there be done,

Every risk, every peril to forestall,

Ordered his men to arm, and, once begun,

Sent them forth from the city, at his call;

Amidst them went Ruggiero, pre-empted

By Marfisa’s haste, with naught attempted.

Canto XXXVI: 26-29: Their contest sparks conflict between the camps

The enamoured youth gazed on, to see,

Fearing the outcome for Bradamante,

Knowing Marfisa’s skill and bravery,

Doubting where might lie the victory.

He doubted at the start, I say, wholly,

When they first engaged, but latterly

As the duel progressed before his eyes

Was filled with amazement, and surprise.

And seeing that the battle failed to end,

As such often did, at the first encounter,

His doubt increased, in that it might portend

Unaccustomed harm to one or the other.

He feared for his lover and his friend,

With deep concern for them both; however,

His heart felt burning passion for the one,

For the other less love than affection.

He would willingly have parted the two,

If he could yet have done so with honour,

But his company, fearing they might view

A victory for Charlemagne’s warrior,

Who seemed by far the stronger, in their view,

Drove between them, ending the encounter;

While, from the other camp, the Christians sped,

And battle waged between the foes instead.

On both sides they now sounded the alarm,

Which indeed occurred almost every day,

Bidding those on foot mount, the unarmed arm,

And summoning all to this fresh affray.

More than one horn cried out impending harm,

With a piercing note, o’er the trumpets’ bray,

And as their notes sent forth the cavalry,

Tabors, and side-drums roused the infantry.

Canto XXXVI: 30-36: Bradamante attacks Ruggiero

As fierce and sanguinary a skirmish

As any could imagine now took place,

While Bradamante thwarted of her wish,

Her foe thus vanishing before her face,

Unable to fight on to the finish,

And slay Marfisa, paused there, for a space,

Turning this way and that her questing eyes

Seeking her love, the cause of all her sighs.

By the eagle argent, on an azure shield,

She recognised Ruggiero midst the throng;

Her thoughts and gaze intense, o’er the field

She saw those mighty shoulders, broad and strong,

The manly features, and the grace revealed

By his movements, yet, conscious of the wrong

He’d done her, thinking he loved another,

Spoke thus, to herself, in pain and anger:

‘Shall another, then, kiss those lips, so sweet

And fine, if those same lips are lost to me?

Ah, no other shall with those favours meet;

For, if not mine, no other’s must you be.

Rather than die alone, in sole defeat,

Ere I die beside you, your death I’d see.

Then, if I lose you here, at least in hell

I’ll have you; there, eternally, to dwell.

Or if you slay me, I shall have obtained

The solace of vengeance still, for the law

And justice will demand he who’s deigned

To take another’s life shall die; far more

Painful my death, if such were thus ordained;

I’d die unjustly, you beneath the claw

Of justice. I’d slay him who would slay me,

You, a maid that has loved you endlessly.

Why, my hand, do you lack the power

To drive true steel to my enemy’s heart?

He’s wounded me to death many an hour,

Secure in the love I showed for my part,

And still would slay me, and my life devour,

Without an ounce of pity, then depart.

Fight, brave spirit, and the wretch dismiss;

Let me avenge my thousand deaths with his!’

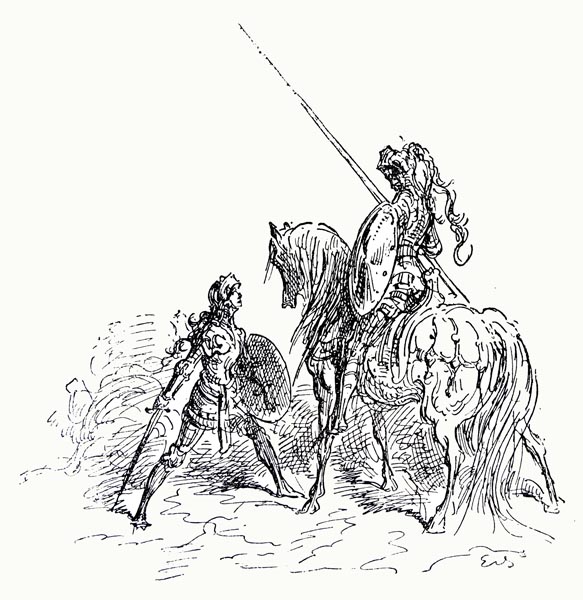

So saying, she spurred her brave steed, and cried:

‘Guard yourself, O faithless Ruggiero!

The heart of a proud maid shall be denied

You here, as the spoils of war, this I know.’

Ruggiero heard her call, where he did ride

Amidst the hostile ranks, and felt the blow,

Knowing it was her voice, forever prized,

That, midst a thousand cries, he recognised.

Furthermore, he recognised from that cry

That she’d accused him of disloyalty,

And so, with the aim of explaining why

He’d been delayed, and seeking parley,

He signalled to her; but it passed her by,

Her visor being closed; she came swiftly,

Full of hurt and rage, with vengeful hand;

And twas on hard earth he seemed like to land.

Canto XXXVI: 37-39: He eventually addresses her

Ruggiero, seeing her so angry,

Settled into his armour, and his seat,

Raised his lance, and held it vertically

So that he would not harm her should they meet;

While riding towards him, mercilessly,

Intending now to wound, nowise to greet,

The maid yet could not bear, seeing him near,

To unhorse the form that she yet held dear.

Void of effect their lances at that meeting,

And, indeed, that was well, since Love had so

Jousted with each ere they came to greeting

The other, he’d pierced their hearts at a blow.

Since she would do naught, her passage fleeting,

Bradamante turned her fury on the foe,

And did such deeds as fame and glory earn,

While the heavens above such warfare turn.

In a brief space of time, that golden lance

Flung three hundred or more to the ground.

Alone she won the fight with her advance,

Scattering the Moors all that field around.

Ruggiero, with the aid of circumstance,

Made his way towards her, his tongue he found,

And cried: ‘Alas, what have I done to you

That you should fly? Hear me; for I hold true!’

Canto XXXVI: 40-42: They turn aside to a nearby vale

As, when a southerly blows from the sea,

The deep snow melts, the icy claws relent,

While the imprisoned rivulets flow free,

Hearing that fervent cry, that brief lament,

Bradamante’s heart melted, at the plea,

Seemingly vanished, all her discontent,

Filled now with mercy, and compassionate,

The heart that had seemed turned to stone, of late.

She could not, or she would not, make reply,

But spurred brave Rabicano to one side,

And signing to Ruggiero, gave a sigh,

As forth from the battlefield she did ride.

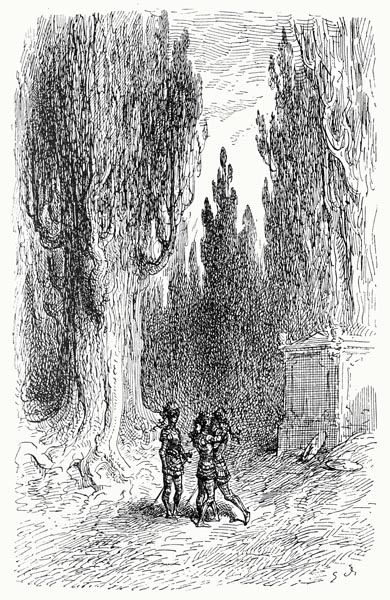

Far from the multitude, and yet nearby,

A sheltered vale lay hid, and deep inside

A grassy lawn about some cypress trees,

That, seeming of one stamp, the eye must please;

Within that grove, a noble monument,

Of snow-white marble stood; twas newly made;

With a brief inscription to represent,

To whoe’er cared to know, who there was laid.

Though, meseems, upon her thought now intent,

Bradamante noticed little of that glade.

Ruggiero spurred his horse, hard as he could,

And joined the warrior-maiden in the wood.

Canto XXXVI: 43-46: Marfisa follows, only to be attacked by Bradamante

Meanwhile we return to bold Marfisa,

Who remained there, mounted on her steed,

Her eyes searching for the valiant warrior,

That had toppled her to earth with such speed,

And saw Ruggiero meet with that stranger,

And then depart, the latter in the lead,

Deeming not that he followed out of love,

But to end the joust, and his honour prove.

So, she spurred her horse, and followed after,

Almost reaching the vale as soon as they,

How much pain this might cause to either,

Any lover here knows, without my say;

Yet to Bradamante more than the other,

Vexed by finding her ‘rival’ still in play;

For who could not believe the truth to be

That love for Ruggiero drew her enemy?

And faithless, she called him once again:

‘Was it not enough, you faithless traitor

That I must learn of what has brought me pain,

Through rumour, without having thereafter

To bear witness to it? Your desire, tis plain

Is to drive me away; that aim I’ll further;

But my own is, with my last parting breath,

To slay her, the true reason for my death.’

Bradamante, with this (more spite revealed

Than a viper’s) advanced upon her prey,

And with her lance pierced her enemy’s shield,

Who fell upon the ground, in such a way,

That half her helm was buried in the field;

Nor was she taken by surprise, I’d say,

Resisting the blow with all her worth,

Yet her head nonetheless struck the earth.

Canto XXXVI: 47-50: The warrior-maidens resist attempts to part them

Bradamante, who wished to slay Marfisa

Or die herself, was now in such a rage,

She disdained to use the lance against her,

To hurl her to the ground, but would engage

Now, with her glittering blade, and sever

That head trapped in the sand, and assuage

Her need for vengeance, and, losing the lance,

Dismounted, drawing her sword in advance.

But her arrival was tardy, for Marfisa

Had scrambled to her feet, so full of ire,

At having felt the ground rise beneath her

A second time, so burning with desire,

That Ruggiero’s pleas failed to move her,

Who gazing on, begged either to retire;

Yet both were so possessed by spite and rage

That neither maid would quit that martial stage.

They were at less than sword-length, suddenly,

Yet such was their great pride, you understand,

Both pressed hard, and were so close, so quickly,

They’d no choice but to grapple hand to hand;

For their swords they both let fall, and swiftly

Sought some means to hurl their foe to the sand.

Meanwhile Ruggiero begged the pair to cease,

Gaining scant success with his prayers and pleas.

Finding his shouts and cries were all in vain,

He decided to part the two by force;

The dagger from each maid he thought to gain,

And thereby stop the battle in due course.

He won both weapons, and returned again

To plead, then threaten, shouting himself hoarse,

Yet in vain, since they used their fists and feet

Lacking aught else, for neither would retreat.

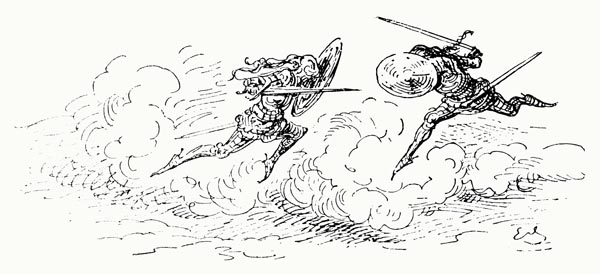

Canto XXXVI: 51-57: Marfisa turns upon Ruggiero

Ruggiero persisted, grasping either

One or the other, by hand or arm,

Such that Marfisa, waxing in anger,

Was quite ready to work the knight some harm,

For, disdaining all the world, as ever,

To her his friendship held no special charm;

And, quitting the fight with Bradamante,

She ran to seize her sword, and then, swiftly,

Attacked the knight, crying: ‘Discourtesy

And treachery it is to interfere;

Yet I’ll punish your lack of chivalry;

My sword will serve to conquer any here.’

Ruggiero sought to quell hostility

With fair and gentle speech, but found, I fear,

Marfisa filled with such pride and disdain

That all he uttered was sent forth in vain.

In the end, Ruggiero drew his sword,

Deep anger reddening his face also.

I think no other sight could have ensured

Such joy as Bradamante now did show,

(None, indeed, that the ancient texts record

Of Rome or Athens; nor of which I know)

As this battle, viewed by the jealous maid,

That, to her every doubt, had now put paid.

She’d recovered her own sword from the ground,

Yet she stood aside to watch, for her part,

For it seemed to her the god of war had found

A home on Earth, in the knight’s strength and art,

While, if he seemed Mars, in Marfisa bound,

A hellish Fury, to and fro, did dart;

Though tis true Ruggiero yet refrained

From exerting all his power, tightly reined.

He well knew the virtues of his weapon,

So extensive the use of it he’d made;

Where it fell, every spell of the magician

Was rendered vain, by that enchanted blade.

He wielded it so that, within reason,

Nor point nor edge, but flat alone was laid

Upon the other’s sword, continuing so

Till he suddenly lost patience, at a blow,

A mighty stroke, that bold Marfisa dealt,

Intending, thus, to split his skull in two.

For he’d raised his shield, and slightly knelt,

So the blow would the eagle emblem hew.

And, while upon his arm the stroke he felt,

The enchanted shield yet denied his foe;

Still, were it not that he wore Hector’s mail

His swift defence had proved of small avail,

The blow would have sheared away his arm,

And struck his head, at which the maid had aimed,

He could scarce lift the limb without a qualm,

Nor sustain the shield, somewhat split and maimed.

At this all mercy fled; to do her harm

The sole thought that his attention claimed.

He smote, and smote as fiercely as he could:

Ill for you Marfisa, had the stroke proved good!

Canto XXXVI: 58-62: The voice from the tomb

I know not how it came about, but, lo,

His weapon struck against a cypress tree,

And, to a hand’s depth, it was buried so,

While the trunk shivered, and rang loudly.

At this the mountain, and the plain below,

Shook with a mighty tremor while, clearly,

A more than mortal voice arose on high,

From the sepulchre, in the grove nearby.

This dreadful cry issued forth: ‘No more!

Twould be a deed unjust, and inhumane,

If a brother slew a sister, nor forbore,

Or a brother by a sister’s hand were slain.

My Ruggiero, my Marfisa, this is sure,

(Nor the words that I deliver said in vain)

In one womb, of one seed, were you begot,

And born together; entwined is your lot.

Galaciella’s children are you; whom

She bore to Ruggiero the Second,

Whose brothers had sent him to his doom,

Leaving her to her grief, the fair and fond.

Not knowing that she carried in her womb

You, his offspring, e’er bound by mortal bond,

She, in the fragile timbers of a boat,

They set adrift to flounder, or to float.

But Fortune, that had destined you, unborn,

To many a glorious enterprise,

Drove the boat to that lonely and forlorn

Shore, that by Syrtes sandy waters lies,

Where, having given birth to you at dawn,

She rose to join the souls in Paradise.

As God willed, and your destiny say I,

It so happened that I found myself nearby.

I granted her a simple burial,

Such as I could amidst the desert sand,

And wrapping you both then in my mantle,

Bore you to Mount Carena, close inland.

I drove a lioness from her cubs to suckle

Your infant selves, although, with my own hand,

I learnt how to nourish you, with her milk,

Nigh on two years, or something of that ilk.

Canto XXXVI: 63-66: Atlante tells the tale of the twins’ separation

One day, while abroad in the countryside,

And, thus, far from the chamber where you lay,

An Arab host discovered you, inside,

As perchance you recall, for, on that day,

They seized you, Marfisa, who sought to hide,

While Ruggiero wisely sped away.

I was left to grieve your loss, most deeply,

While guarding Ruggiero more closely.

You know, Ruggiero, if Atlante

Guarded you well; to do so, I did try.

For the fixed stars revealed your destiny,

That by treachery, midst the Christians, you’d die.

And so, to thwart their influence wholly,

I sought to avert your fate, kept you by.

Lacking power in the end to stay your will,

I fell sick, and grieving died, yet not until,

Through infernal aid, this tomb was complete,

Whose stones were laid by more than human might,

For I had foreseen that you two would meet,

With Marfisa you were destined to fight.

And I told Charon, deep beneath your feet,

That my spirit should rest here, day and night,

In this glade, till a sister and a brother,

Marfisa and yourself, fought one another.

And so, my shade has waited for your coming,

In this pleasant glade, for many a day.

Bradamante, from jealousy now ceasing,

Know Ruggiero has loved but you alway.

And, thus, from the light I go, receding,

For, to the shadows, I now make my way.’

His voice failed there, no sound his going raised,

Leaving the three astounded and amazed.

Canto XXXVI: 67-69: The three warriors are reconciled

Ruggiero, with joy, now knew Marfisa

As his sister, and she him as her brother;

They, without hurting the maiden-warrior,

Met together, and embraced each other,

And one thing from childhood and another

They remembered, this brother and sister,

And confirmed with, ‘I was’, ‘I did’, ‘I said’,

All the wizard had told, or left unsaid.

From his sister, Ruggiero did not hide

That Bradamante occupied his heart,

And by what obligations he was tied

To a maiden he had loved from the start;

Nor ceased till he had taught either side,

To change hatred to love, and with such art

That they embraced, without affectation,

As a mark of true reconciliation.

Marfisa then turned to Ruggiero

And asked who and what was their father,

Who had killed him, and the means also,

And if in the field or someplace other;

And who’s the request, what savage foe

Had brought about the death of their mother,

For of aught she had been told, earlier,

Little or nothing could she remember.

Canto XXXVI: 70-74: Ruggiero tells Marfisa of their family history

Ruggiero told her they were descended

From Trojan stock, of Hector’s lineage;

That after Astyanax amended

His state, and somehow escaped the outrage

Proposed by Ulysses, and had ended

His presence in his own land, he wended

His way upon the deep sea, till he gained

Sicily’s shores, and in Messina reigned.

‘His descendants were the lords of Faro,

In Calabria and, many a long year after,

Departed thence for Rome, and prospered so

That more than one king and emperor

Of their blood there held court, elsewhere also;

Many a name known to fame and power.

Thus, from Constantius, and Constantine,

To Pepin’s Charlemagne extends their line.

Ruggiero the First, and Gianbarone,

Were scions of his, Buovo, and Rambaldo,

Down to Ruggiero the Second, for twas he

Who, as Atlante said, sired us; and, know,

Of our line, many a deed, famed in story

Shall be celebrated in this world below.’

Of Agolante, and Almonte he then told

(Galaciella’s father); with Troiano bold

They had come, and how Almonte’s daughter

Accompanied him, who was so valorous

That many a paladin fell before her;

And how for Ruggiero, e’en then famous,

And, his love, she rebelled gainst her father,

Was baptised, and wed; of the incestuous

Love of the traitor, named Beltramo,

For his brother’s wife, he told also.

He his country, and his father, betrayed,

And his two brothers, hoping to have her,

Laying Risa open to a hostile raid,

Such that all his kin were made to suffer;

While Agolante (whom his sons obeyed)

Set Galaciella, their dear mother,

Great with them and six months gone, in a boat

In winter, midst a tempest, there to float.

Canto XXXVI: 75-79: Marfisa exhorts him to avenge their parents

Marfisa, listened, face calm as the dawn,

As her brother pursued his tale’s course,

Delighted to learn that they were born

Of a line that flowed clear from its source.

Thence Chiaramonte’s House came to adorn

The halls of fame, Mongrana’s drew its force;

Renowned throughout the world many a year,

For peerless leaders, famous in their sphere.

When, finally, she learned from her brother

That their father’s death had been contrived

By Agramante’s grandfather, and father,

And uncle, and that all three had connived

To destroy her mother, listening no further,

(Though, often, to contain herself she’d strived)

She cried: ‘Brother, too long have you delayed

In seeking vengeance; wrongs should be repaid!

Almonte and Troiano, both are dead,

Yet why should this race of theirs survive?

Why not vengeance on Agramante’s head?

Why, since you live, is he, as yet, alive?

Tis a stain upon our name that, instead,

Though you are wronged, you but watch him thrive.

Not only have you failed to slay this king,

You take his pay, serve him in everything!

I swear to God, for I shall worship now

Christ the Lord, worshipped by my father,

That I’ll not doff this armour, such my vow,

Until I’ve avenged him, and my mother.

I’ll grieve for you as, here, to grief I bow,

If midst those ranks, or those of some other

Of the Moors, I find you, unless you go,

Sword in hand, amongst them as their foe!’

Oh, how Bradamante raised her lovely head

At those words, and inwardly rejoiced!

She urged Ruggiero, for vengeance bred,

To heed the sentiments his sister voiced,

And join Charlemagne’s camp, his cause to wed,

(Where he’d be praised) and there his banner hoist.

For Charlemagne honoured his father’s name,

And, as a peerless knight, revered that same.

Canto XXXVI: 80-84: It is agreed he should remain awhile in the Moorish camp

Ruggiero, cautiously, answered her,

That long ago he would have done the deed,

But the facts were hidden from him ever,

And, when he knew them, twas too late indeed;

For having been knighted since, moreover,

By Agramante, he would be decreed

A traitor, and thus everywhere abhorred,

Should he slay the one deemed to be his lord.

Yet, as he had promised Bradamante,

Ere now, he would seek a fit occasion

To quit the king, and do so plausibly,

Not marring, thereby, his reputation,

If he could; and if he was not yet free,

Then twas of Mandricardo’s creation,

For she knew he’d been wounded by that knight,

And left sorely stricken from the fight;

And she, who’d sat beside his bed each day,

Was as good a witness to that as any.

The two warrior-maids had much to say

Twixt them regarding this, yet did agree,

In conclusion, he should return that day

To the Moorish king, and his company,

Till he found a sound occasion to resort

To Charlemagne, and thereby join his court.

‘Let him depart now’, cried bold Marfisa,

To Bradamante, ‘Doubt not that before

Many days shall pass, I will discover

A means by which he’ll cease to serve the Moor.’

So said the maiden, without, however,

Revealing, there, the plan she had in store.

Bidding leave of them both, Ruggiero

Had turned his steed towards the Moorish foe

When they heard a plaintive cry from the vale,

Which, nearby, now caught all three’s attention.

They paused to listen, there, amidst the dale,

To what seemed some poor maid’s lamentation;

Yet I must end this canto here, and avail

Myself of rest, ere, for your delectation,

I bring, I promise, finer things to you,

When the very next canto you pursue.

The End of Canto XXXVI of ‘Orlando Furioso’