Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXV: Bradamante at the Bridge

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXV: 1-2: Ariosto to his lady

- Canto XXXV: 3-9: Astolfo sees the source of Ippolito d’Este’s life-thread

- Canto XXXV: 10-17: Of the old man, and the name-plates he bears away

- Canto XXXV: 18-30: Saint John explains the things they have seen

- Canto XXXV: 31-34: Bradamante meets Fiordelisa on the road

- Canto XXXV: 35-40: And agrees to challenge Rodomonte

- Canto XXXV: 41-47: With whom she agrees the terms of their encounter

- Canto XXXV: 48-52: Bradamante defeats King Rodomonte

- Canto XXXV: 53-56: She removes the trophies taken from Charlemagne’s knights

- Canto XXXV: 57-61: She hands Frontino to Fiordelisa

- Canto XXXV: 62-65: Fiordelisa seeks out Ruggiero

- Canto XXXV: 66-72: Bradamante seeks to joust with him

- Canto XXXV: 73-80: She encounters and defeats Ferrau

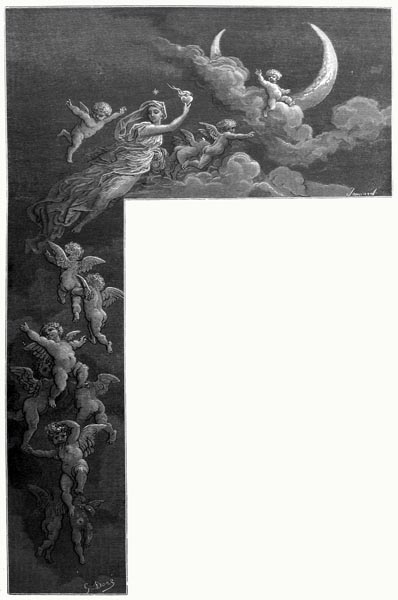

Canto XXXV: 1-2: Ariosto to his lady

Who’ll ascend the heavens for me, my lady,

And return my lost sense and wits to me,

Which, since the sharp arrow flew so swiftly

From your eyes to my heart, ebb endlessly?

Yet I’ll complain not of that loss, if only

I lose no more of them, injuriously,

For, if they waste further, I fear, ah woe,

To become such as I’ve shown Orlando.

To restore my wits and sense, I realise,

I have but little need to soar through space,

To the moon’s sphere, or to Paradise,

For they are lodged in no far distant place.

Tis o’er your face serene, your lovely eyes,

Alabaster neck, ivory breasts, I trace

Their passage, while I seek thus to retrieve,

With my lips, those wanderers ere they leave.

Canto XXXV: 3-9: Astolfo sees the source of Ippolito d’Este’s life-thread

Through the spacious palace, roamed Astolfo,

While gazing at the bales, from which the thread

Of future lives would be drawn, destined so

To be wound on the spindle from them fed;

And viewed a bale that seemed to cast a glow

Brighter than gold; no gem such light could shed;

Though ground, to form a thread, by magic art,

Twould lack the brightness of its thousandth part.

That lovely bale pleased him marvellously,

Without an equal in that wondrous space,

And he desired to know who’s that might be,

What life it signified, its time and place.

That life’s brief span would commence but twenty

Short years (Saint John declared) ere that of grace

(If they were counted from the Incarnation)

Containing both an M and D, when written.

‘And just as, in splendour and in beauty,

That bale’s rich substance is beyond compare,

So will the age be fortunate and happy,

That in his most singular life shall share.

For all the grace that Nature and Study

Can grant a man, both excellent and rare,

Or which kind Fortune on us can shower,

Such shall be his fair, unfailing dower.

Between two noble stretches of the river,

(The Po, the king of rivers) stands a town,

Small and humble still, while pale mists cover

The land behind it, which deep marshes drown.

She, as the years revolve, shall prove ever

First of Italian cities in renown,

Not only for her palaces on view,

But for Ferrara’s arts, and customs too.

Such exaltation, rapidly achieved,

Will not arrive fortuitously, by chance,

But ordained there on high shall be conceived,

Prepared for him I speak of, in advance.

(The stem to bear fine fruit, its graft received,

Must be protected from ill circumstance,

As the artificer refines the gold

That the precious gem, he sets will hold.)

Ne’er in so fine a raiment e’er was dressed

That soul that, in mortal guise, shall appear;

Ne’er so worthy a spirit, Earth’s fair guest,

E’er descended from the heavenly sphere,

As by the Eternal Mind shall be blessed;

Ippolito d’Este, his fair name here

Shall be; this man, on whom God doth elect

To shower such gifts, and his brave form perfect.

All the virtues that, scattered among many,

Would serve to adorn them all most richly,

Will be combined, in his person, wholly,

This prince of men, of whom you ask me,’

Saint John declared, ‘And fine arts, and study,

He shall sustain; indeed, if you’d have me

Speak of his other merits, to regain

His sense, poor Orlando shall wait in vain.’

Canto XXXV: 10-17: Of the old man, and the name-plates he bears away

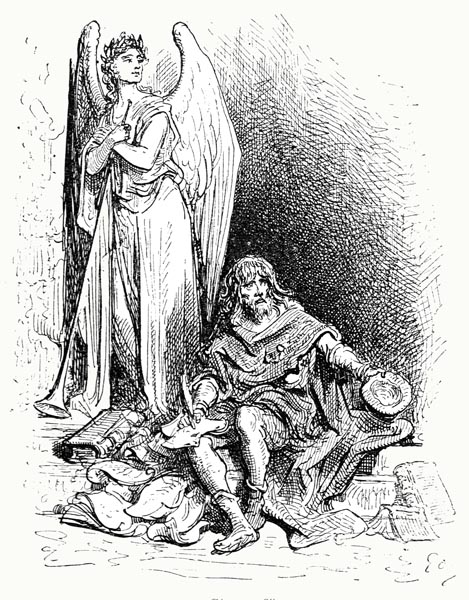

Thus, Christ’s servant spoke with Astolfo,

And when they had seen every chamber,

The bales and threads of mortal lives on show,

Through which the path of destiny flows ever,

They viewed a river, that stirred the sand below,

Thus, turbid, discoloured was the water;

And saw that aged man upon the shore

That with the name-plates hastened, as before.

I know not if you have him still in mind,

He that I spoke of in the last canto,

Ancient in looks, but nimble enough, you’d find,

As to outrun a stag when in full flow.

He filled his cloak with names, but left behind

Swiftly replenished heaps as, to and fro,

He went, gifting the names to Lethe’s stream,

Or drowning them there, rather, it would seem.

For, I tell you, whene’er he reached the shore,

That prodigious old fellow shook his cloak,

And into the turbid waters cast, once more,

A countless number, lost at a single stroke;

Nor were they then of use, none could restore

Those names that a host of lives might evoke,

For tis scarce one in a hundred thousand

Survives, of those that fall to the hidden sand.

Around, and along Lethe’s waters, flew

Flocks of rapacious vultures and crows,

And ravens and others, that did e’er pursue

Those spoils, and from the birds loud cries arose,

Whene’er he re-appeared to their view;

Then all would plunge from the sky, God knows,

To seize those that remained, in beak and claw,

Yet little distance those fair names they bore.

For when those birds, again, sought the air,

They’d not the strength to long sustain their flight,

And so, the names worthy of memory, there,

Fell to dark Lethe’s waters, lost from light.

And yet two snowy swans that might compare,

In their whiteness, to Este’s eagle bright,

Caught what names they could, for, evermore,

They bore them, safely, to dark Lethe’s shore.

Thus, counter to the thoughts, ill and malign,

Of that old man who casts them in the water,

Some names are saved by means of those benign

White birds, though oblivion every other

Fair name consumes, while that pair divine

Now swim, now beat the air, till they recover

Their place upon the bank of that ill stream,

Below a hill, on which a shrine doth gleam,

Sacred to Immortality; from there

A lovely nymph descends the grassy hill,

To those shores, that sad Lethe’s waters share,

And those bright names, that the dark beaks fill,

She hangs about a statue, high in air,

Upon a column in mid-shrine, where still

They may glow, and eternity outlast:

Consecrated by the nymph, and held fast.

Of that old man, and why he chose to throw

Those names into the waters, all in vain,

And of the swans, and sacred shrine, also,

From which the nymph descended to the plain,

Astolfo had a great desire to know

Their solemn mystery, and a sense would gain

Of their import, and prayed he would disclose

The man of God, the meaning of all those.

Canto XXXV: 18-30: Saint John explains the things they have seen

‘You must know not a single leaf can move

On Earth without some sign of it up here.

Since all on Earth and in the skies above

Corresponds, yet differently will appear.

That old man, who the names doth e’er remove,

So swift that naught delays him, year by year,

Performs the same task in this lunar clime

As is performed below, by passing Time.

The thread that on the spindle here is wound

Of some human life down there, is the sign;

Of those famed below, here, the name is found,

And both would be immortal and divine,

If not for that greybeard who scours the ground,

And Time below; both to one end align.

He casts their names, here, into the river;

Time submerges them, forgot, forever.

And just as here, the raven, vulture, crow

And other birds attempt to seize the names

That shine most brightly, so there below

Pimps, and informers, thieves with all their games,

Fools, and accusers, equally do so,

Whom never a soul thinks less of, nor blames,

As do all those courts nourish, all that are

Better rewarded than the good, by far,

And are addressed as noble courtiers,

Although, like swine or asses, oft ill-bred;

They, when the Fates, or more oft, it appears,

Venus and Bacchus, snip their master’s thread,

Those base and idle rascals, his for years,

Born but to wine and dine; once he is dead,

Bear his name on their tongues a day or so,

Then let it fade to oblivion, there below.

Yet as the swans here carry to the shrine

Those spoils that bear the memory of a name,

So are men, worthy of some authors’ line

Saved from oblivion, preserved for fame.

O princes, cautious and discreet as mine,

That Caesar’s example prize, do the same:

Win yourselves some fine poet as a friend,

And fear not Lethe’s waters, at life’s end!

Are not such poets rare as swans, indeed?

That of the name of poet prove worthy?

Since as rarely have the heavens decreed

That some prince shall tread the path of glory,

While, the rest, in error, full of greed,

Let sacred genius starve (e’er the story!),

Suppress the Virtues, see the Vices thrive,

Banish art, and watch bare ignorance thrive.

Such princes God deprives of intellect,

(And from them He conceals pure wisdom’s light)

That loathe all poetry, and its claims reject,

Such that bodily death consumes them quite.

Those other few fresh life may yet expect,

Evil though they may be, far from the right;

Those Delphi’s god yet chooses to befriend

Shall savour of myrrh and nard, in the end.

Aeneas was ne’er as pious, nor as brave

Was Hector, nor great Achilles as strong

As they have been claimed to be, while the grave

Holds many a man fine as those in song,

Yet the rich farm that some descendant gave

To the poet helped to move their fame along,

And raise those heroes to the heights of honour,

Exalted by the more than grateful author.

Augustus was ne’er as sacred or benign

As Virgil’s epic makes him out to be,

Yet, given his taste for the flowing line,

He’s forgiven Ovid’s exile, as we see.

Nero’s injustices none would divine,

Nor would the man be known for cruelty,

Though both heaven and earth had proved his foe,

Had he won Lucan to his side below.

Homer shows Agamemnon a victor,

And makes the Trojans ever vile and base,

While Penelope’s as faithful as ever,

Suffering the suitors with a noble grace,

Yet if you’d have me speak true (as ever!)

History would show quite another face:

The Trojans won, the Greek battalions ran,

While fair Penelope proved a courtesan.

Yet hear what fame Elissa left behind,

That fair Dido, who bore a humble heart,

Whose reputation is so poor we find,

Because old Virgil scorned her in his art.

Marvel not that I bring all this to mind,

And speak at length, for I too played my part;

Authors I love, and pay the debt I owe,

For I was an author too, down below.

And there, beyond all other men, I earned

What Time, and Death can never take away;

So, tis befitting that, to me, Christ turned,

Whom I so praised, to show that future day,

And him of glorious fate of whom you’ve learned;

While sad for those that in the dark night stray,

Whom Courtesy denies, midst rains that pour,

Though, pale and wan, they beat upon her door;

Such, pursuing thus my previous theme,

Are the poets and scholars; the honest few,

Who, finding no bed or board, it would seem,

In princes’ halls, must search the world anew.’

So said the holy saint, whose eyes did gleam;

(Much like twin flames of fire blazed the two)

Then Saint John turned calmly, with a smile,

Towards the duke, and was at peace the while.

Canto XXXV: 31-34: Bradamante meets Fiordelisa on the road

We’ll leave Astolfo to his peaceful viewing,

While I leap to the Earth from out the skies,

For I can’t hang for ever on the wing,

But must turn to Bradamante, and her sighs,

Who, wounded by jealousy’s sharp sting,

Was flying from Tristan’s Tower, likewise.

I’d left her at the point where she had won

The field, and downed three kings there, one by one,

And had then arrived at a nearby town,

On the road from Paris, where she had heard

That Agramante, to preserve his crown,

Had retreated to Arles; such was the word.

Convinced Ruggiero, given his renown,

Would be there, with the king, she sought to gird

Her loins, at dawn, and set out on the way

Charlemagne had pursued with scant delay.

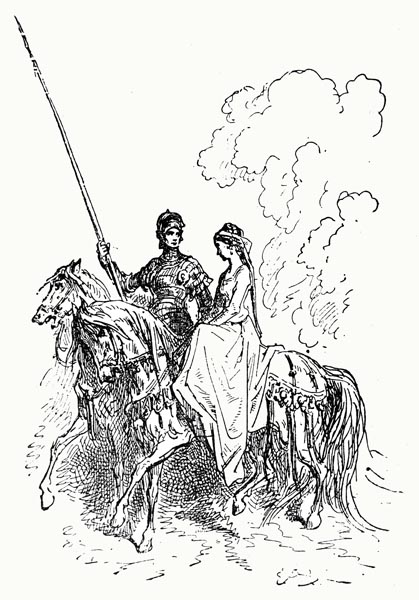

Towards Provence then by the shortest road

Travelling swiftly, she came upon a maid,

Whose face with copious tears overflowed,

Yet beauty and nobility conveyed.

Twas the lady on whom Love had bestowed,

This longing for Brandimarte she betrayed,

She who’d left her lover at the bridge, lately,

Where he’d surrendered to Rodomonte.

She was searching, now, for a valiant knight,

Used to land or water, like an otter,

And so brave he would champion her in fight,

Against the Saracen lord, and not fail her.

As this sad and tearful lady came in sight,

Bradamante, also sad, riding nearer,

Saluted her courteously and, to follow,

Asked her the cause of her deep sorrow.

Canto XXXV: 35-40: And agrees to challenge Rodomonte

Fiordelisa, gazing at her, saw

A warrior most suited to her need,

And began to speak of the bridge, and more

Of Algiers’ mighty king of evil deed,

That sought to slay the one she did adore;

Not that the king was mightier indeed,

But that he’d gained no small assistance

From the bridge and river, in that instance.

‘Are you,’ she said, ‘so courteous and brave,

As you appear to show by your manner,

That for love of God, you’d my lover save,

And take vengeance on that cruel warrior,

Who’s saddened me, and doth him enslave,

Or counsel me where to find some other

So skilful that neither river nor bridge

Will grant the fierce Saracen advantage.

Besides the fact that you will thus extend

Your aid to a courteous knight, acting so,

By your courage you would surely befriend

The truest of true lovers known, also;

His other virtues, on which I depend,

Let me not speak of, many are they though,

Such that those who mark them not, I fear,

Must lack the eyes to see, or ears to hear.’

The warrior-maid to whom was welcome

Every noble quest that might yet enhance

Her honour and her fame, wherever from,

Resolved to ride at once, with sword and lance,

To the Saracen’s bridge, for she, in sum,

Would rather die, in her sad circumstance,

Than live believing that her Ruggiero

Was lost to her, and suffer endless woe.

‘For what it may be worth’ she now replied,

‘I will undertake this dread encounter,

Because, sweet lady, you have testified

To the many virtues in your lover,

That few men may claim and all else beside

Among those, you maintain, moreover,

That he is constant, strong in loyalty,

While I thought all were prone to perjury.’

She ended with a sigh, our warrior-maid,

A sigh that issued from her very heart,

And said: ‘We should go.’ Then through the glade

They took their way, both eager to depart,

And reached the bridge, where the trumpet brayed

Which summoned the king to play his part,

On the following morn; Rodomonte

Armed, and sped to the encounter, swiftly.

Canto XXXV: 41-47: With whom she agrees the terms of their encounter

As she seemed to be a well-armed knight

He threatened to despatch her in a trice,

Unless her horse and armour were outright

Conveyed to him, for such was, there, the price

All must pay, or be slain in mortal fight,

In tribute to the tomb; such would suffice.

Bradamante knew, from Fiordelisa,

How he’d caused the death of Isabella,

And cried: ‘You brute, why should the innocent,

Do penance for a sin that was your own?

Tis fitting that you bleed, such my intent,

For you killed her; such by all folk is known;

So that, of the spoils, that hang for ornament

About her tomb, from those here overthrown,

Most fitting of all would be your armour;

Your death would pay her the greatest honour.

And sweeter would the gift be from my hand,

For as she was a woman so am I,

And here, for no other reason, I stand,

Than to avenge her, and to see you die.

But first a pact between us I demand,

Ere I now challenge you, and you reply:

If I am overthrown, then you may do

As you have done to those you overthrew,

But if, as I think and hope, you shall fall,

I’ll have your steed, and your amour too,

And remove the other amour from the wall

And hang yours there alone, for all to view,

And free the captives that you hold in thrall.’

‘Tis just,’ the king replied, ‘and yet tis true

Those prisoners cannot be rendered so,

They were transported elsewhere, you should know.

To my African realm have they been sent,

But I promise you now, and swear the same,

That if you should succeed in your intent

While I’m unseated in our little game,

Then I will free them all, and rest content,

In such time as an order in my name

May be carried to those in my command,

Instructing them to do as you demand.

But if you’re overthrown, as is likely,

And I am sure the outcome will prove so,

I’d not hang your amour, nor proudly,

Add your name, as my victim, there below.

But on your face, eyes, hair, on your beauty

That breathe but love and grace, I’ll bestow

The victory, and ask but that you love me,

Where now, so it would seem, you hate me.’

‘If am of such valour,’ the maid replied,

‘And of such skill that you need not disdain

To bow to me.’ And smiled, upon her side,

Although she smiled in a most bitter vein,

And more in anger than aught else beside.

Then returned to the bridgehead once again,

Spurred her steed, levelled her lance before,

And rode to the encounter with the Moor.

Canto XXXV: 48-52: Bradamante defeats King Rodomonte

King Rodomonte now came on at speed,

And with such a mighty sound of thunder,

It echoed all about the bridge, indeed,

Enough to fill a listening ear with wonder;

Yet, in an instant, the golden lance decreed

That the Saracen, who tore his foes asunder,

Was lifted from the saddle, hung in air,

Then fell upon the bridge, its dust to share.

The warrior-maid found scant room to pass

Her enemy now lying on the ground,

And was at considerable risk, alas,

Of ending in the river, yet she found,

Or rather Rabicano did, from the impasse

(For the steed was dextrous and, as yet, still sound)

A path of sorts along the outer ledge,

As if he trod a sword-blade set on edge.

Bradamante, turning the horse about,

Addressed the king, in a sportive manner:

‘The loser of the joust is scarce in doubt,

For, now, we may see who proves the winner.’

Indeed, thus overthrown, in their first bout,

The king said naught, merely gazed in wonder,

Amazed that a woman had laid him low,

As dumb as if his wits were ever slow.

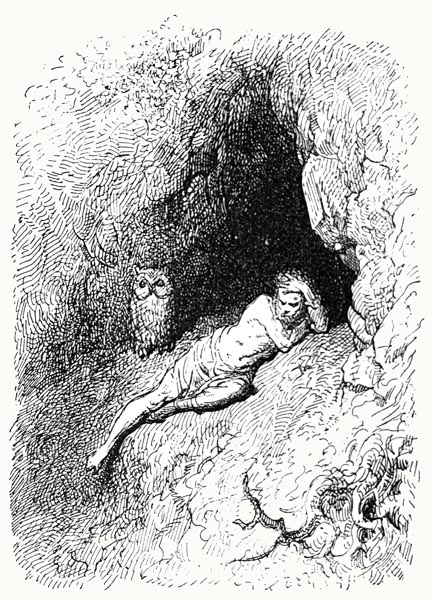

He rose, both gloomily and silently.

When he had gone six paces, less perchance,

He doffed his helmet, mail, and plate, sadly,

(Once he’d laid down his shield, and sword, and lance)

Flung it down on the stones; alone, and slowly

He walked away having issued, in advance

Of his departure, his command to a squire

To order all as the maiden might desire.

He went, and was heard of, there, no more,

Except twas said he dwelt in some dark cave;

While Bradamante to the tombstone bore

His gear, and hung it high above the grave.

Then, removing all the arms that she saw,

From the writing, had belonged to some brave

Knight of Charlemagne’s court, she left the rest,

Nor allowed what remained to be addressed.

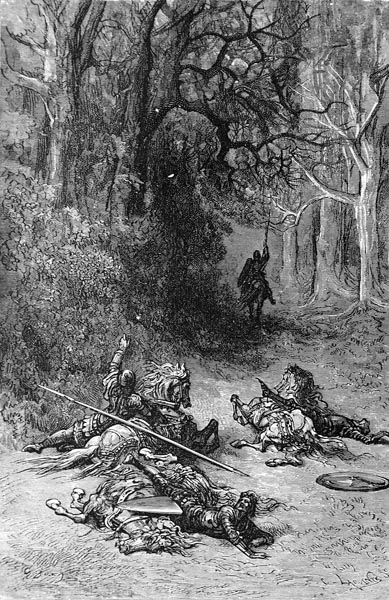

Canto XXXV: 53-56: She removes the trophies taken from Charlemagne’s knights

Besides those of Brandimarte, the heir

Of Monodante, those of Oliviero

And Sansonetto she found, for that pair

Had arrived in search of Count Orlando,

And, the day before, had been taken, there,

And despatched to Africa, by their foe.

Their arms and armour, that very hour,

She saw removed and stored in the tower.

All those once borne by some pagan knight,

Bradamante left hanging midst the fane,

Among them Sacripante’s, who day and night,

Sought his steed, Frontilatte, all in vain.

His arms had Rodomonte seized outright,

Thus, he, after wandering hill and plain

In search of the steed, had lost another,

And gone his lonely way, bereft as ever.

Now on foot, and stripped of his armour,

The Circassian king left the bridge behind,

For Rodomonte (twas a point of honour)

So treated those to his own faith aligned;

Yet Sacripante had no wish to further

The war, as he’d previously designed,

Ashamed to show his face after boasting,

In such a fashion, from defeat yet reeling.

A fresh desire now claimed his stricken heart,

To seek Angelica, whom he still loved;

For he had learned, while seeking to depart,

(The source unknown, yet by him approved)

That she had sailed for home, for her part;

And now, spurred on by Love, he was moved

To pursue her who plagued him, and swiftly;

While I turn again to Bradamante.

Canto XXXV: 57-61: She hands Frontino to Fiordelisa

Once that maid had added an inscription

To the tomb, stating how she’d freed the way,

She asked of Fiordelisa, whose affliction

Of weeping kept her head bowed alway,

With great courtesy, in what direction

She now proposed to go, if she could say.

Fiordelisa answered: ‘I would go now

To Arles and the Saracen camp; I vow

To seek a ship, and fitting company,

And cross the sea, and there, in Africa,

Not rest until I’ve found my lord, for he

Is imprisoned there, and every measure

I shall try that might serve to set him free.

If what Rodomonte promised further,

Is not so, if some treachery I discover,

I shall seek his liberty from some other.’

Bradamante replied: ‘May I offer,

My company for part of your journey;

Till we have sight of Arles, but no closer.

There I’d have you seek, for love of me,

Agramante’s Ruggiero; that warrior

Is named with praise in every country;

And render to that knight this fine steed

From whose saddle the Saracen I freed.

I would have you tell him this: “A knight

Gave me charge of this horse, that you might be

Equipped for the joust, who seeks to fight

And prove to the world your disloyalty.”

Then hand the courser’s reins to him outright,

And say again you had the horse from me,

While he must don his armour, and await

My coming, who shall there decide his fate.

Say this and naught else, and if he’d know

Whom I might be, say you know not my name.’

The other answered, in her kindness, so:

‘I’ll not weary of performing that same

And other tasks for you, that I might show

My gratitude, and so discharge the claim

You have upon me.’ So, Bradamante

Handed her Frontino’s rein, gratefully.

Canto XXXV: 62-65: Fiordelisa seeks out Ruggiero

Down the Rhone’s fair course, all the livelong day,

The two fair travellers rode in company,

Till they reached Arles, and heard the distant play

Of waves upon the bare shores of the sea.

Near the edge of the town, before the way

Crossed its boundaries, fair Bradamante

Halted to grant time for Fiordelisa

To seek Ruggiero, with the courser.

Fiordelisa passed the bridge and the gate,

And found a guide to keep her company,

And show her where Ruggiero lodged and ate.

There, she descended from her steed, promptly

Found the warrior; and the message, of late

Entrusted to her by fair Bradamante

She conveyed to him, with the horse, Frontino,

Then, without waiting, on her way did go.

Ruggiero stood bemused, in deep thought,

Unable to make head nor tail of who

Had issued the challenge, and had sought

To speak ill of him yet courteously too.

Who had this charge of disloyalty brought,

Or might any charge at all so pursue,

He could not conceive, and least of all

Did his thoughts upon Bradamante fall.

His suspicions fixed on Rodomonte,

Much the most likely in his opinion;

Though that he should speak of disloyalty

Was a thing, seemingly, without reason.

Yet none other, as far as he could see,

Had so quarrelled with him on occasion.

Meanwhile Bradamante blew her horn

The warrior to summon, and to warn.

Canto XXXV: 66-72: Bradamante seeks to joust with him

To Agramante and Marsilio,

Came the news that a warrior sought battle,

While in their presence stood Serpentino;

He now gained their leave to show his mettle,

Promising that such pride would be brought low.

The walls of the town soon filled with people,

A willing audience, as young and old

Sought to see what fine deeds might now unfold.

In a rich surcoat, over splendid armour,

Serpentino of the Star sped to the fight,

And yet he fell at the first encounter,

While his courser, as if twere winged, took flight,

With Bradamante chasing swiftly after.

She returned the steed to the winded knight,

Saying: ‘Mount, and go tell your lord to send

A better knight with whom I might contend.’

The Moorish king, who, with his company,

Stood on the battlements to gaze thereon,

Marvelled at this warrior’s courtesy,

Towards poor Serpentino, whereupon,

The king remarked: ‘He sets the vanquished free,

Though he need not,’ this heard by everyone.

Serpentino re-appeared and, as commanded,

Claimed a better knight was now demanded.

The fierce Grandonio di Volterna,

The proudest warrior in all of Spain,

Begged King Agramante for the honour

Of the second joust, and then took to the plain.

‘Courtesy shall not avail you further,’

He cried to Bradamante, ‘I shall deign

To unhorse you and lead you to my lord,

Or slay you, if I can, with lance or sword.’

‘I would not wish your lack of courtesy,’

She replied, ‘to deprive me of my own,

But I beg you to turn again, swiftly,

Ere but solid ground greets your flesh and bone.

Return, I pray, and tell your lord from me,

Not to place such as you again, on loan,

For to find a true warrior of worth,

I have come, one whose name is known on earth.’

Her stinging answer, both sharp and bitter,

Fanned the knight’s fury to a mighty flame,

Who, rendered speechless, now wheeled his courser,

His face filled with anger and with shame.

The warrior-maid wheeled her own charger,

Rabicano, and spurred hard at that same,

The deadly golden lance now struck his shield

And, heels in air, he tumbled to the field.

The magnanimous maid returned his horse,

Saying: ‘I told you such would prove your fate;

Better if, ere we’d fought, you’d had recourse

To your lord than stayed, to feel my lance’s weight.

Tell the king, I pray, from his mighty force

To choose a knight, and not one second-rate,

And not weary me so, by sending more

Knights, like you, inexperienced in war.’

Canto XXXV: 73-80: She encounters and defeats Ferrau

Those on the walls knew not who this might be,

This warrior that had so well held his seat,

Calling out the names of knights, though vainly,

That made them shiver in the noonday heat.

Some thought it was surely Brandimarte,

Others that Rinaldo was more complete,

While others claimed this to be Orlando,

Though his state of madness all seemed to know.

The third joust, bold Ferrau, Lanfusa’s son

Now claimed, saying: ‘Not that I hope to fare

Better than those before me have done,

Yet their falls may seem easier to bear.’

Then he donned fine armour he had won,

And, from a hundred steeds, stabled there,

He chose the best there was, famed indeed

For its great strength in battle, and its speed.

He rode to the encounter with the maid,

But first saluted her, as she the knight.

‘If tis permitted, midst those here arrayed,

Pray, tell me who you are, before we fight,’

She said; and he his name and rank conveyed,

Who concealed it not from her, as was right,

‘You I’ll not refuse,’ she cried, ‘though I

Came to seek another, I’ll not deny.’

‘And who might that be?’ bold Ferrau replied,

She answered: ‘Ruggiero,’ in a whisper,

And then, her lovely face with crimson dyed,

Blushed like a rose, and added, thereafter,

‘I would prove if his claim be not mere pride,

To great skill and bravery; that I’d discover.

I seek naught else; I have no other wish,

But that I prove myself gainst him, in this.’

She spoke these words, in all simplicity,

Which some might have thought to show ill-will.

Ferrau replied: ‘The laws of chivalry,

Demand that I should fight against you still;

Yet if perchance I fall, as previously

Those others did, then he my place shall fill,

At my request, that noble knight, you say

You’d so like to encounter, this fair day.’

While she was speaking, the lovely maid

Had kept her visor raised above her face.

Ferrau marvelled, as he quietly surveyed

Her beauty, and was half-conquered apace;

And to himself he said: ‘Here is portrayed

An angel from paradise, filled with grace,

And though as yet not pierced by his lance,

I fall already, conquered by a glance.’

They took the field and, as occurred before,

Ferrau shot from his saddle, in brief flight.

The horse Bradamante seized once more,

And cried: ‘Return, and speak my wish, sir knight.’

Shamed, he went and looked about, and, when he saw

Ruggiero, told him of that angel bright,

And how he’d been informed the fair stranger,

Sought to meet him, now, in brave encounter

Ruggiero, knowing not whom this might be

That had summoned him to fight in the field,

Yet assured, in his mind, of victory,

Had his armour borne to him, and his shield;

Nor was his brave heart the least uneasy

At having seen those others swiftly yield.

Yet how he armed, went forth, and what befell

Our brave knight, a further canto must tell.

The End of Canto XXXV of ‘Orlando Furioso’