Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXIX: Orlando Restored

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXIX: 1-7: Melissa deceives King Agramante

- Canto XXXIX: 8-18: Marfisa and Bradamante join the fight

- Canto XXXIX: 19-22: Meanwhile Astolfo defeats the foe in Africa

- Canto XXXIX: 23-25: And agrees to King Branzardo’s offer

- Canto XXXIX: 26-29: A fleet of ships is miraculously created

- Canto XXXIX: 30-35: Rodomonte’s ship full of prisoners is intercepted

- Canto XXXIX: 36-38: A savage man appears wielding a sapling

- Canto XXXIX: 39-43: The maiden who has appeared is Fiordelisa

- Canto XXXIX: 44-47: She recognises in the savage the mad Orlando

- Canto XXXIX: 48-54: The knights struggle to pin Orlando down

- Canto XXXIX: 55-63: But eventually succeed in restoring his wits

- Canto XXXIX: 64-65: Orlando and Astolfo pursue the siege of Bizerte

- Canto XXXIX: 66-73: Agramante flees to Arles

- Canto XXXIX: 74-79: He sails for Africa, unaware of Dudon’s fleet

- Canto XXXIX: 80-86: A naval battle ensues

Canto XXXIX: 1-7: Melissa deceives King Agramante

More bitter, harsher, stronger, than any

Was the sadness that afflicted Ruggiero,

Troubling the mind, more so than the body;

Facing death from one or the other foe.

From Rinaldo, if he fell to that enemy,

From Bradamante if he killed Rinaldo,

For he knew, were he to conquer her brother,

A hatred, worse than death, would slay her lover.

Rinaldo, who was dogged by no such thought,

Aspired to win by any means, and sought

Whirling his axe about, oft falling short,

To strike at arms or head, and not in sport.

Ruggiero circled wisely, as they fought,

And each fierce blow upon his weapon caught,

And if he struck endeavoured so to smite

As to do least harm to the Christian knight.

To most of the Saracens the contest

Seemed unequal, so slow was Ruggiero

To use his great skill, feeble here at best,

And easily rebuffed by Rinaldo.

Agramante was troubled, with the rest,

He sighed gazing at the curious show,

And laid the blame on Sobrino’s head

Whose ill counsel to this display had led.

Meanwhile Melissa who was the fount

Of all, that mages and enchanters know,

Had now transformed her shape, by such amount

As needed, Rodomonte’s form to show,

Both her face and gestures, by all account,

Seemed his, and her harsh scaly hide also,

And such her sword and her shield beside

She lacked no arms with that fell lord allied.

She rode a steed, a demon trapped inside,

That she now steered towards Agramante,

And loudly, with troubled brow, she cried,

‘My liege lord, this is no less than folly,

To imperil a mere boy, as yet untried,

Gainst this Frankish lord who fights so fiercely,

Electing him your champion in a cause

That affects all Africa’s northern shores,

And her honour; pursue it not, my lord,

For twill prove greatly to our detriment;

Rodomonte all the blame you may afford,

For the swift breaking of the covenant.

Let every man among us draw his sword,

Each is worth a hundred, and of adamant,

Now I am here.’ This swayed Agramante,

Who advanced upon the foe, recklessly.

Believing Algiers’ king was at his side,

He gave no further thought to the pact,

Deeming him worth a thousand knights, he cried

A summons to his lords, roused them to act,

Till levelled lances swept in one great tide

Towards the foe; nor could he now retract.

Melissa, as the furious onslaught neared

The Christian ranks, quietly disappeared.

Canto XXXIX: 8-18: Marfisa and Bradamante join the fight

The two champions, their duel ended,

Despite all promised by the joint accord,

No longer now attacked or defended,

But pledged that neither knight would wield the sword,

(Setting aside the effort they’d expended)

Until some evidence men might afford

As to which king his honour so did stain

Young Agramante, or old Charlemagne.

They swore, anew, to deem an enemy

Whichever of the two had done the deed.

The field was now confused as, hastily,

Men ran to meet the foe, or fled at speed.

Mingling now the coward and the worthy,

In a single throng, where none agreed,

All ran alike, to what end none could say;

Some ran towards the foe, and some away.

As greyhounds on the leash, that some hare

Have in their view, as it flees o’er the field,

Thus, unable with the other dogs to share

The furious chase, their passion ill-concealed,

Will fret, and whine, and grieve, in despair,

And pull against the rope that will not yield,

So, till that moment, were the bold Marfisa

And Bradamante, Almone’s daughter.

Until that moment, on the spacious plain,

Each had waited, eyeing the sought-for prize,

Both obliged, by the treaty, to refrain,

From attempting some hostile enterprise,

Lamenting and sighing, though in vain,

Coveting their prey with greedy eyes.

But now, with the breaking of the treaty,

They pounced upon the Moorish enemy.

Marfisa, piercing her opponent’s breast,

While her lance two clear yards beyond did go,

Drew her sharp sword, and flew among the rest;

Four helms, like glass, she shattered at a blow.

Bradamante upon the others pressed;

Although not with like effect, even so,

All the golden lance touched she overthrew,

Doubling Marfisa’ count, though none she slew.

At first, they fought so closely together

That both were witnesses to every deed,

Then, parting swiftly from one another,

Each warrior, where her fury might lead,

Advanced midst the foe, competing ever.

Who could count the Moorish riders, indeed,

Downed by that golden spear, or every head

That Marfisa struck from the bloodied dead?

As when some more benign wind seeks to blow,

Laying bare a snowy Apennine height,

Till a pair of streams start their downward flow,

(Whose fall two separate channels carves outright,

Uprooting rocks, and mighty trees that grow

On those steep slopes, bearing, far out of sight,

Both turf and soil) and seem as if they vie

As to which can do the greatest harm thereby,

So those great-hearted maidens scoured the field,

On their separate courses, while each wrought

Huge havoc, forcing many a Moor to yield

Before the lance or sword howe’er they fought.

Agramante scarce could force his men to wield

Their weapons; for flight, not the flag, they sought,

In vain he gazed about him, urgently,

Yet found not a trace of Rodomonte.

At that warrior’s urging (so he believed)

He’d broken the treaty but lately made,

Swearing by Mohammad (though deceived),

And yet the man had vanished; sore dismayed,

He lacked wise Sobrino too, deeply grieved

By this action, who’d but a moment stayed,

Then retreated to Arles, crying to all

That vengeance would upon the monarch fall.

Marsilio had fled to that same place,

The sacred oath now weighing on his heart,

Thus, Agramante could but briefly face

Those that laboured there on Charlemagne’s part;

Italians, Germans, Englishmen, apace

Came upon him, with lance, and sword, and dart,

And among them those paladins, full bold,

Rare gleaming gems amidst a cloth of gold.

There rode one, as perfect as any knight,

In this our world, Guidon Selvaggio,

Ever intrepid, eager for the fight,

And those two sons of Oliviero;

Of those two warrior-maids, still in sight,

I’ll say but this, pressing upon the foe,

They such sterling effort did expend

That of the Moorish dead there seemed no end.

Canto XXXIX: 19-22: Meanwhile Astolfo defeats the foe in Africa

Yet, setting aside this battle for a space,

I shall pass, without a ship, o’er the sea,

Not so bound to the Franks, in that place,

That Astolfo has slipped my memory.

I told you of Saint John’s act of grace,

And related (or so it seems to me)

How Algeciras’ king, with Branzardo,

Had mustered all their forces gainst the foe.

Hastily, they had raised a host of men,

Gathering them from all North Africa,

Whether sound or infirm, and had often

Nigh-on drafted the women, in their fervour;

Agramante had so drawn, now and then,

On his resources, that every warrior

Was already assisting his campaign,

And those left were but feeble in the main.

As now was seen; the foe was scarce in sight

Before that makeshift army broke in fear,

Driven like sheep before the English knight,

And his more warlike troops; far or near,

They preferred to flee rather than to fight,

Yet few reached Bizerte, with sword or spear;

Brave Bucifaro lost his liberty,

While King Branzardo attained the city,

More grieved at the loss of Bucifaro

Than at having squandered all the rest

(In need of repair, the walls of Hippo

Were his charge, and his skills of the best).

And so, the thoughts of King Branzardo

Turned to ransoming the Nubians’ guest,

And he recalled Dudon, a warrior

Who’d been for many months his prisoner.

Canto XXXIX: 23-25: And agrees to King Branzardo’s offer

This Dudon had been seized at Monaco

By Rodomonte, on his first passage,

And had been captive since, to his great woe;

The paladin was of Danish lineage.

Thinking to exchange him for Bucifaro

The king now despatched an urgent message,

To the leader of the Nubian foe;

That, his spies informed him, was Astolfo.

As a paladin himself, Astolfo knew

He must seek to free Dudon if he could,

And so Branzardo’s offer did pursue,

Agreeing the exchange should be made good.

Dudon, once free, his thanks did e’er renew,

And set himself, as perchance he should,

To support all appertaining to the war,

On land and sea, as he had once before.

Astolfo having such a force in hand

As might have conquered seven Africas,

And recalling it was the saint’s command

That he should regain, from the warriors

Of North Africa, Aigues-Mortes’ captive strand,

And all Provençe, now searched for sailors

Midst his host, or rather such Nubians

As might, aboard ship, execute his plans.

Canto XXXIX: 26-29: A fleet of ships is miraculously created

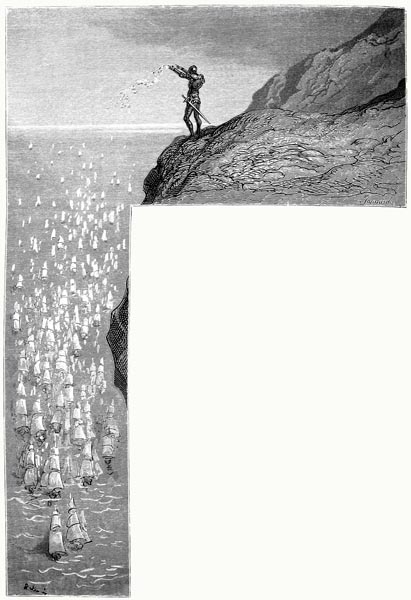

He now grasped as many fronds in each hand

As would fill them, from many a fine tree,

(Palm, laurel, cedar, bay grow in that land)

And scattered them, evenly, o’er the sea.

O grace, ever God’s and at His command!

True blessing and divine felicity!

A stupendous miracle He wrought there,

Out of those very fronds the waves did bear!

They grew, in size, beyond all estimation,

Becoming vast and curved, long and wide,

Of heavy timber now each new creation,

Their veins great solid beams on either side.

Masts rose on high, as they held their station,

For o’er the bay a fleet of ships did ride,

And all possessing varying qualities,

According to their source amidst the trees.

It was wondrous to see that navy grow,

Galleys, frigates, pinnaces, a vast host,

With oars, and sails, and rigging, all on show,

As fine as any another fleet might boast.

Nor was there any lack of men to row,

Or spread the canvas wide, while from the coast,

And from Sardinia, Corsica, came those

Skilled in dealing with every wind that blows.

Twenty-six thousand men went on board,

With captains, pilots, and many another,

With wise Dudon as their admiral, that lord

Fit to lead on sea, or land, wherever.

They were anchored, till the winds might afford

Them passage, when a vessel, from over

The water, reached the shores of that country,

Twas that ship despatched by Rodomonte.

Canto XXXIX: 30-35: Rodomonte’s ship full of prisoners is intercepted

Those seized at the perilous bridge she bore,

Where the field of battle was so narrow,

By Rodomonte, as oft told before.

Amongst them was the bold Oliviero,

Orlando’s kin, and there, midst many more,

Were Brandimarte and Sansonetto,

And brave knights from many a fair country,

Gascony, Germany, or Italy.

Her captain, unaware of this hostile foe,

Here brought his laden galley to anchor,

With Algiers far behind him, for the blow

Had barred him from that safer harbour;

A gale it was that had pursued him so,

And borne her along the coast much further,

Yet he still thought himself a welcome guest,

Like to Procne when she seeks her noisy nest.

But when the Imperial eagle he saw,

Leopards, and golden lilies, raised on high,

He blanched, like one who, wandering o’er the moor,

Treads on a basking adder, that doth lie

Amidst the heather, and, shaken to the core,

Hastens, pale, and fearful he may die,

To flee from the place, and that ill creature,

Of such a venomous and angry nature.

Yet no retreat from peril was on show,

Nor could he restrain his prisoners.

He, by Brandimarte, Oliviero,

And Sansonetto, and many others

Was dragged before Dudon and Astolfo,

(Who greeted them joyfully, as brothers)

And condemned him, who’d brought them to that shore,

To labour in the galleys, at the oar.

Great welcome there had each Christian knight,

To Astolfo’s quarters, with honour,

They were led, and decked out, in his sight,

With all they required of arms and armour.

Dudon delayed his passage, for that night,

Wishing to speak with them, and gain further

News of events elsewhere, though at the cost

Of perhaps a day, or two, that might be lost.

He learned of Charlemagne’s situation,

That of the Moorish army, and of France,

And of where he might land in that nation

To best advantage, and from there advance.

Meanwhile, to their utter consternation,

A noise was heard, of some assault perchance,

Followed by such a mighty trumpet call,

As to foster great concern, in one and all.

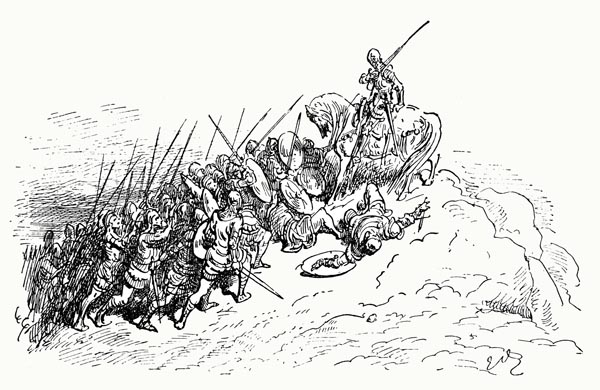

Canto XXXIX: 36-38: A savage man appears wielding a sapling

Astolfo, and his goodly company

Who were thus conversing together,

Armed themselves, and mounted instantly,

And hastened to where the cries seemed louder,

Seeking the source of that cacophony,

Gazing here and there, as they rode further,

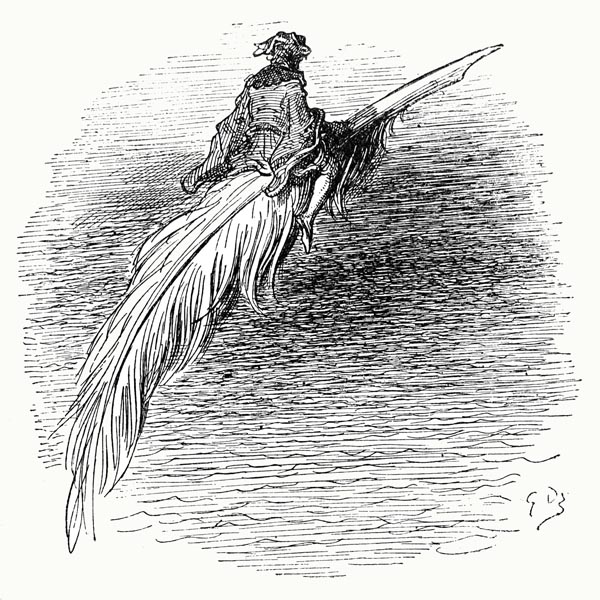

Till they saw a crazed savage, all alone

Half-naked, who made many a man to moan.

For he whirled a great sapling all around,

So hard, and so heavy, and so strong,

That, at every swing, it felled to the ground

Some man that to the force there did belong.

At least a hundred corpses lay around,

And yet none attempted to right the wrong,

Save by their hurling missiles from afar,

Since none with his great strength seemed on a par.

Went, galloping there, each and every knight,

Dudon, Brandimarte, Oliviero,

Amazed by this savage show of might,

Hastening behind bold Duke Astolfo,

When a maid on a palfrey came in sight,

Clad in sable gear, as one full of woe,

Who approached Brandimarte at a pace,

And clasped that warrior in tight embrace.

Canto XXXIX: 39-43: The maiden who has appeared is Fiordelisa

Twas fair Fiordelisa, she whose heart

Burned with love for her Brandimarte,

And had been sorely troubled, for her part,

To leave him in the hands of Rodomonte.

She’d sailed across the sea, pierced by that dart,

Once she had learned, from that fell enemy,

That the brave knight, with many another,

Had been shipped to Algiers, a prisoner.

She’d sought passage at Marseilles, and had found

A Levantine barque there, about to sail,

Which had brought an aged knight, homeward-bound,

Of Monodante’s House, who’d heard the tale,

And had searched those foreign shores all around,

For Brandimarte, though all to no avail,

And then had heard, amidst his merry dance,

That he’d find that very same, back in France.

And she, recognising this Bardino

As he who had from Monodante’s court

With the infant Brandimarte taken flight,

Then reared the child in the Sylvan Fort,

And learning the reason why the knight

Had journeyed far, had them leave the port,

Having told the old man in what manner

Her lover had been shipped to Africa.

She had news, when they landed, that Hippo

Lay under siege, and that Brandimarte,

Was there in company with Astolfo,

Though unconvinced of the tale’s verity.

Now, on seeing him, she flew to him though,

And revealed her true delight most plainly,

Finding her grief now proven overblown,

While the joy was great as e’er she had known.

The noble baron felt no less delight,

On viewing his loyal consort’s face,

For he loved it o’er every other sight,

And he welcomed her with sweet loving grace;

Nor would he have been satisfied, her knight

With only their first, or second, embrace,

Had he not discovered that Bardino

Had journeyed from France with her to Hippo.

Canto XXXIX: 44-47: She recognises in the savage the mad Orlando

He stretched out his arms to clasp Bardino,

Ready to ask him why he was there,

But found himself unable to do so,

For all the folk involved in this affair,

Were forced to take flight, to escape a blow

From the tree the savage waved in the air.

Fiordelisa, gazing on the naked fellow,

Cried to Brandimarte: ‘Tis Orlando!’

At that very moment, Astolpho too

Recognised the Count by certain signs,

Which had indeed been taught to him anew,

In the earthly paradise, by those divines,

Though none of the others, who did view

The savage, yet thought on similar lines.

Through self-neglect, as all about he ran,

In his face he appeared more beast than man.

His heart transfixed by pity, Astolfo,

Bathed his manly chest with many a tear,

And turned to Dudon, then Oliviero,

Who’d failed to recognise the Count, twas clear,

Crying: ‘Behold, this is Count Orlando!’

They both now strained their eyes towards the peer,

And, seeing him in such a dreadful plight,

Were filled with compassion at the sight;

And they sorrowed so deeply, on their part,

That their salt tears overflowed to the ground,

‘Tis time,’ Astolfo cried, ‘to seek some art,

Cease our weeping, and render his mind sound.’

He sprang from his steed, while, with a start,

Brandimarte followed, then, at a bound,

Dudon, Oliviero, Sansonetto,

Leapt down, to secure the mad Orlando.

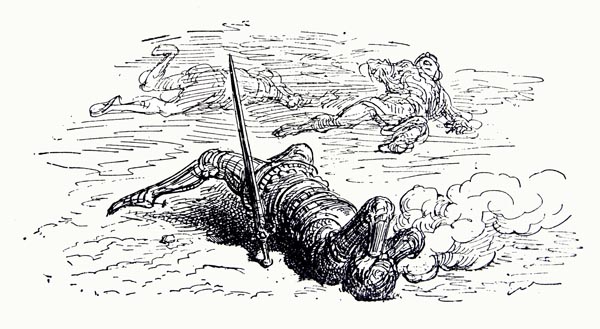

Canto XXXIX: 48-54: The knights struggle to pin Orlando down

Seeking himself encircled, Orlando

Swung the sapling round in desperation,

Causing Dudon, who’d dipped his head below

His shield, a degree of consternation,

Since he received from it a glancing blow;

Oliviero saved him from mutilation,

His prompt use of his blade deflecting it,

Or shield, helm, head, and body would have split.

The shield alone shattered, while the blow

Still landed with such force that Dudon fell.

Though, wielding his sword, Sansonetto

Trimmed that sapling by two clear yards as well.

Then Brandimarte, grasping Orlando

Sought to drag him to the ground; with a yell,

Both his strong arms round his chest he flung,

While to the Count’s bare legs Astolfo clung.

Orlando shook himself (the English peer

Landed upside-down, ten clear feet away)

But Brandimarte clasped him, without fear,

All the more tightly holding to his prey;

Yet Oliviero, too bold it would appear,

Was struck by a clenched fist, and down he lay,

That harsh blow nearly ending him for good,

While forth, from eyes and nostrils, poured the blood.

Had it not been for his helm, Oliviero

Had died there where he fell, toppling endwise,

And striking the ground as if, at the blow,

He’d just bequeathed his soul to paradise.

To their feet rose Dudon and Astolfo,

Dudon with bloodied face, and swollen eyes,

And with Sansonetto (of the helpful sword)

All rushed together on Anglante’s lord.

Dudon grasped him tightly from behind,

And sought to down him, swiftly, with his feet.

Astolfo and the rest now sought to bind

His arms, though the task was left incomplete.

Who has seen some great bull, with fury blind,

Chased by the mastiffs, that his ears mistreat,

Bellowing, tossing them from side to side,

Seeking to fling them from him, far and wide,

Can picture the sight of our Orlando,

Dragging those brave warriors o’er the ground.

Meanwhile, rising once more, Oliviero,

Whom that great fist had so harshly found,

On seeing that the efforts of Astolfo

And the rest had done little to confound

The madman, now devised and effected

A way to down him, when least expected.

He had men bring lengths of rope, good and strong,

And running-knots in these he swiftly tied,

Threw them o’er Orlando as he ran along,

Noosed his arms and legs, and then supplied

The rope-ends to the others, passed among

Them all, to hold the Count on every side.

They stopped the raging madman in his course,

As farriers down an ox or a horse.

Canto XXXIX: 55-63: But eventually succeed in restoring his wits

As soon as he was felled, they gathered round

And tied his hands and feet more securely.

Though he shook himself, and arched from the ground,

His efforts were rendered vain, entirely.

Astolfo bade them bear him, tightly bound,

To where they might restore his sanity.

Dudon’s strong shoulders the Count now bore,

To the sea’s edge, nigh the brink of the shore.

Seven times Astolfo had them bathe him,

And seven times beneath the wave he went,

Until his visage looked a mite less grim,

And his skin was clean, to a large extent;

Then with certain special herbs they gagged him,

And stopped his mouth, to his deep discontent,

Such that only his nostrils were left free,

As Astolfo intended them to be.

Astolfo now took the flask he’d brought,

In which Orlando’s sense was confined,

And set it to the Count’s nose, as he sought

To breathe, so his addled brain it might find.

He drew all in, and a miracle was wrought!

Sound and whole again was Orlando’s mind;

While, by his fluent speech, his intellect

It seemed was yet finer, and more elect.

As one aroused from dark and heavy sleep

In which he saw abominable creatures,

Monsters that exist in slumber deep

And nowhere else, with most fearsome features,

Or did things fit to make a demon weep,

Now marvels at himself, and those far reaches

Of slumber, so Orlando, new-restored,

Was left wondering at the depths he’d explored.

On Brandimarte, and Oliviero,

Aldabella’s brothers, he gazed mutely,

And on him who’d restored him, Astolfo,

Uncertain how he’d got there, restlessly,

Turning his eyes about, for Orlando

Could hardly grasp where he was, and clearly

Was astounded at his nakedness also,

And at why he was bound fast, head to toe.

Then he cried out, as Silenus once cried

To those who had bound him in the cave,

‘Solvite me: loose me!’ this in so clear-eyed

A manner, seeming now both wise and grave,

That they did so, and they clothed him beside

With garments, like one risen from the grave,

And comforted him, now by regret oppressed

For the madness by which he’d been possessed.

Once restored, and then unbound, Orlando

Wiser and more vigorous still in manner,

Now found himself free of love’s ties, also;

For she he had deemed the fairest ever,

And the noblest maid, whom he’d adored so,

Now seemed but a base, and faithless, lover.

His whole study now, his whole desire,

Was all he’d lost through love to reacquire.

Meanwhile Bardino told Brandimarte

That good Monodante his father was dead,

And that, from his kind brother Ziliante,

To call him to rule in his father’s stead,

And from his isles scattered sparsely

O’er the sea, and the far Levant, he’d sped,

Than which there were never realms more happy

More pleasant, or populous, or wealthy.

In a lengthy speech he sought to express,

That one’s homeland was sweet, and whene’er

He was disposed to taste that sweetness

For the wandering life he’d no longer care.

Brandimarte replied that, nonetheless,

He would see the end of all that affair,

Serve Orlando and Charlemagne, and then,

If he lived, return to his realm again.

Canto XXXIX: 64-65: Orlando and Astolfo pursue the siege of Bizerte

The next day, under Dudon, the whole fleet

Sailed for Provençe; meanwhile bold Astolfo

Sat down with Count Orlando to complete

His plans, and told him how the siege should go.

The Count agreed, but rather than compete

For glory, gave credit to Astolfo

On every occasion, while the latter

Yet deferred to Orlando in the matter.

Of the order of troops for the assault

On Hippo, and upon what flank, and when,

The walls were won, almost by default,

At the first attempt, by Orlando’s men,

And of who else that battle did exalt,

Permit me to defer the tale, again.

In the meantime, be pleased to let me show

How the Franks dealt Agramante woe.

Canto XXXIX: 66-73: Agramante flees to Arles

For, in the moment of greatest danger,

Agramante remained well-nigh alone;

Marsilio with his troops, together

With Sobrino and his, to Arles had flown;

Who, unsure of their safety, chose, rather,

To board their vessels anchored in the Rhône,

With those knights and lords, that served the Moor,

Who had, at their example, quit the shore.

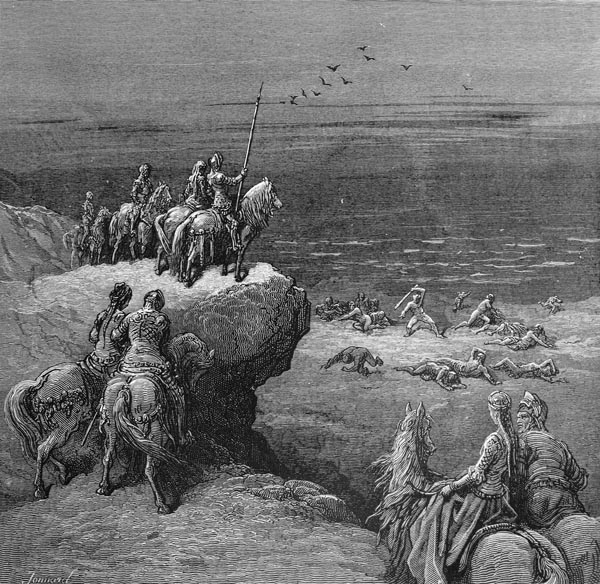

Yet Agramante still maintained the fight,

Until he could no longer make a stand,

Then he turned from the field, and took to flight,

Towards Arles, o’er the intervening land.

Rabicano, spurred hard with all her might

By Bradamante, was now close at hand,

She filled with fierce desire this king to slay

Who’d so oft drawn Ruggiero away;

While the like desire possessed Marfisa,

Who her father sought to revenge at last,

As she spurred her own steed to a lather,

And closed upon the fleeing monarch fast.

Yet neither she nor the pursuing other,

Could reach him, now furiously harassed,

Before he had achieved a swift retreat,

First to Arles, and then aboard his fleet.

As a pair of cheetahs, fine and generous,

Hunting together in the open plain,

On finding that their prey’s more vigorous,

And the victim they desire pursued in vain,

As if ashamed, turn, in inglorious

Defeat, with a show of high disdain.

So, the warrior-maids returned, sighing,

At the hair’s-breadth survival of the king;

Yet ceased not in making war, but chased

The host of others who had swiftly fled,

And with blow after blow, deftly placed,

Struck full many down, and left them for dead.

The scattered foe was beaten and disgraced,

Nor was there sanctuary for those that sped

From the field, since Agramante, to gain

Advantage, barred the gate that faced the plain,

And downed every bridge across the Rhône.

O wretched men, such lives e’er held but cheap,

When tyranny needs not their flesh and bone,

Like flocks of stupid goats, or foolish sheep!

Some to the sea, some to the river flown,

Drowned there, others lay in a bloodied heap.

The Franks slew full many, and at random,

Few worth holding for the sake of ransom.

Of the many nobles that there were slain,

(The dead of both the hosts, in that last fight,

Though the numbers were unequal I maintain,

For far more Saracens were killed in flight

By those two warrior-maids on that plain)

Some trace remains; the traveller has sight,

Near the walls of Arles, by the sluggish Rhône,

Of the Alyscamps, where their tombs are shown.

Meanwhile his vessels of deepest draught,

Agramante had await him out at sea,

Leaving a number of his lightest craft

To attend to stragglers that sought safety.

For two whole days, swirling fore and aft,

Fierce adverse winds kept them to that country,

Till, on the third day, he led forth the fleet,

Bound for Africa, hastening from defeat.

Canto XXXIX: 74-79: He sails for Africa, unaware of Dudon’s fleet

King Marsilio, who was filled with dread

Lest the penalty fell upon his Spain,

And those dark clouds looming overhead

Drenched the land in bitter hail and rain,

With his remnants towards Valencia fled,

Where he fortified the town with much pain,

And prepared for that war which would end

In his fall, and that of many a friend;

Agramante sailed, on Africa intent,

His ships poorly-armed and half-empty,

Empty of men, yet full of discontent,

Three-quarters having died in that country.

Some thought him cruel, some chose to lament

His pride and foolishness, and secretly

Hated him, as in like case men will do,

But, fearing him, were silent, save a few;

For oft some group of close friends spoke out,

Among themselves, trusting in each other,

And vented their anger at the sudden rout,

While Agramante, deceived as ever,

Thought that respect, nay love, ringed him about,

Since feelings were masked, inner thoughts never

Shown in the face, voices still full of praise,

Though filled with lies and flattery always.

The African king was counselled not to land

At Bizerte, for news, borne from the shore,

Claimed that the Nubians were near at hand

And held the coast about against the Moor,

But to disembark on some deserted strand

Far beyond it, not too harsh or insecure,

There marshal his men, and then move, outright,

To aid his people in their sorry plight.

And yet that counsel, wise and provident,

Aligned not with the proud king’s destiny,

That willed that the fleet Astolfo had sent,

Then bound for France across the foaming sea,

Which had been created with like intent,

From those tree-fronds, so miraculously,

Met with his own, at night, at such an hour

Dismal and dark, that all lay in its power.

The king had heard no word of an armed fleet,

Of such magnitude, nor would have conceived

That a hundred vessels could rise complete

From the mere fronds of trees; and so, deceived,

Agramante had sailed in swift retreat,

Not fearing by hostile ships to be received,

Not even setting lookouts at the mast

That might their gaze upon the foe have cast.

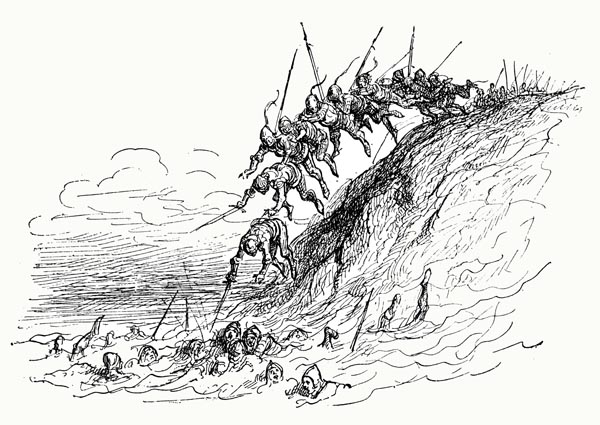

Canto XXXIX: 80-86: A naval battle ensues

Thus, the fleet that Dudon commanded

Supplied by Astolfo, filled with armed men,

Meeting Agramante’s ships, ere he landed,

Stood to battle stations, then tacked again,

Engaging, as the moment demanded,

For they knew, hearing their cries, there and then,

Who these folk must be, from their Moorish tongue,

Boarding them, as the grappling irons were flung.

Driven by the wind, favouring Dudon,

His great ships so shocked the enemy

That many of their own were swiftly gone,

Forced by the blow beneath the churning sea,

While the rest with fire and stones were set upon,

As hands and wits now brought them misery,

Pouring down such a tempest from their foe,

As ne’er the seas have seen, to work them woe.

Dudon’s men, with more than usual might,

And granted fresh strength from above, at need,

(For they could, amidst this opportune fight,

Repay their enemies for many an ill deed)

And having been taught how they could smite

From near and far, sent, as Dudon decreed,

A sudden hail of arrows, while all around

Sword, and pike, and hook, and axe did sound.

Huge, heavy stones descended from on high,

Hurled, by catapults, onto bow and stern,

Opening their timbers to the sea and sky,

Caught by the waves that about them did churn,

Yet the greatest damage, creeping nigh,

Was done by the subtle fires, slow to burn,

From which the wretched crews sought to flee,

Yet ran from the flames to the crueller sea.

One, escaping the enemy’s sharp blade

Leapt to the waves, drowned, and remained.

Another, swimming, his long passage made,

To another ship, also swamped and maimed;

She denied him, his grasping hand delayed

As he sought to climb aboard, and then claimed

His whole arm, while the fellow sank below,

Staining the waves with blood from the blow.

Others who sought salvation in the sea,

Or, at least, to perish there with less pain,

Finding naught to aid them, and suddenly

Feeling the strength from out their bodies drain,

Now most afraid of drowning, hastily,

Sought to return, yet met the flames again,

And, grasping a burning plank, in their dread

Of either death by both, to death, were sped.

Others, seeing a pike or axe draw near

Ran towards the bulwarks, yet all in vain,

For a stone or arrow, following in the rear,

Caught the coward, ere the waves he could gain.

Now, while perchance it still attracts an ear,

Tis wise, and good, to cease my sad refrain,

Rather than harp upon this theme too long,

And, thus, annoy with its too-mournful song.

The End of Canto XXXIX of ‘Orlando Furioso’