Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXIV: Astolfo on the Moon

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXIV: 1-5: Astolfo decides to enter the cavern

- Canto XXXIV: 6-10: Where he encounters the shade of Lydia

- Canto XXXIV: 11-15: Lydia speaks of the ungrateful lovers

- Canto XXXIV: 16-19: She tells of herself and her suitor Alcestus

- Canto XXXIV: 20-24: Alcestus turns against her father

- Canto XXXIV: 25-30: Lydia persuades him to relent

- Canto XXXIV: 31-34: Alcestus restores all he has gained

- Canto XXXIV: 35-40: Lydia seeks to destroy him

- Canto XXXIV: 41-43: She causes him to sicken and die

- Canto XXXIV: 44-46: Astolfo blocks the entrance to the cave

- Canto XXXIV: 47-52: Then climbs to the mountain summit

- Canto XXXIV: 53-57: Where he encounters Saint John

- Canto XXXIV: 58-62: With Enoch and Elijah

- Canto XXXIV: 63-68: Astolfo learns of Orlando’s mad frenzy

- Canto XXXIV: 69-72: He journeys to the moon

- Canto XXXIV: 73-82: And reaches a vale where all things lost from Earth go

- Canto XXXIV: 83-87: He finds Orlando’s store of sense

- Canto XXXIV: 88-92: The Palace of the Fates

Canto XXXIV: 1-5: Astolfo decides to enter the cavern

O, vile and famished Harpies that have fed

So long on blind Italy, full of error,

That, to punish the ancient sin, are led

To enact, gainst each board, Heaven’s anger,

Innocent children, pious mothers, dead

Of hunger we see, while you thus hover

Above them, the food and drink consumed

That gave life to those now sadly doomed.

Too great the fault of those who unclosed

The cavern that was sealed so long ago,

From whence the greed and stench now disclosed

Infected our Italy with its flow.

These the good life, we possessed, opposed,

And peace in our land extinguished so

That war and poverty are now her state,

And for many a year such must be her fate,

Till she grips her thoughtless sons by the hair,

Drags them from Lethe, and cries out: ‘Where, now?

Like to Calais and Zetes, that bold pair,

Are those who will free her, and will vow

To cleanse the board, and her sad state repair,

The claws and stench that plague her, disallow,

As they saved Phineus from his suffering,

Likewise, Astolfo Ethiopia’s king?’

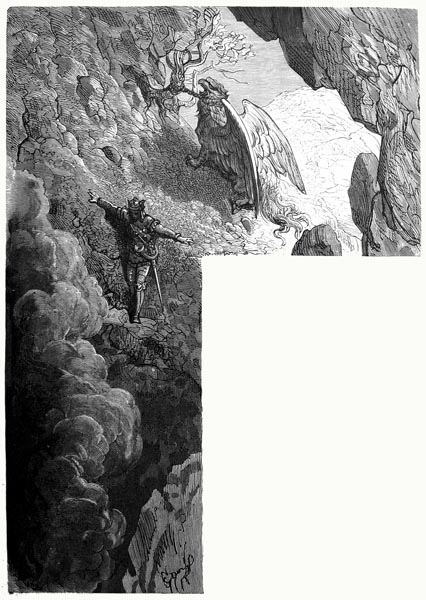

For our brave paladin, the English knight,

Had chased the Harpies, blowing on his horn,

Till they reached the mountains, in their flight,

Where a cavern, from the depths, once was torn.

To that fissure, to which they’d plunged, outright,

He set his ear and heard their cries forlorn;

While groans, deep sighs, and endless sad lament,

The path to Hades rendered evident.

He was doubtful whether he should enter,

And view the shades denied the light of day,

Penetrating to the Earth’s deep centre,

There the infernal abyss to survey.

‘Yet, why fear,’ he cried, ‘when, as ever,

The enchanted horn’s call will clear the way?

Dis and Satan, will both flee from the sound,

As will Cerberus, the triple-headed hound.’

Canto XXXIV: 6-10: Where he encounters the shade of Lydia

He dismounted, swiftly, from the winged steed,

Then tethered it to a sapling nearby,

And entered the cavern (though, indeed,

He grasped his magic horn tight, as would I)

He’d not gone far before he felt the need,

To sneeze, and wipe the damp soot from his eye;

For blacker than pitch, and much thicker,

Was the foul darkness; though ne’er a flicker

Of fear did he show; the deeper he went,

The worse the fog, and the vile stench, became,

And it seemed to him, within that noisome vent,

That he best retreat, and issue from that same.

Yet, behold, something moved, with darkness blent,

From the vault above, naught that he could name,

Hanging, as a corpse, from the gallows, might,

Withered by the wind, and bleached by the light.

Though there was little light by which to see,

Within that dark, and deep, and smoke-filled place,

So, to Astolfo twas a mystery

What thing it was that hung before his face;

Meanwhile, to ascertain what it might be,

He gave it a thrust or two, and made a space,

With his sword, deeming it then a shade,

That he’d but seemed to strike at with his blade.

But then he heard a mournful voice that cried:

‘O, without harming others, thus descend,

For in these dark fumes, suffering, I abide,

That from infernal fires, below, ascend.’

At these words, the duke, amazed, slacked his stride,

And replied to the voice: ‘May Heaven send

You relief from the fumes the depths exhale,

And, if it please you, tell your woeful tale,

For, if you’d have me bear the news above

Of your sad state, I shall most readily.’

The shade replied: ‘If to the light I love,

My name returns, that is so dear to me,

That I must do, an orator must prove

Despite myself, to win such charity,

And who I am may say, if this you seek,

Though tis tedious and wearying to speak.’

Canto XXXIV: 11-15: Lydia speaks of the ungrateful lovers

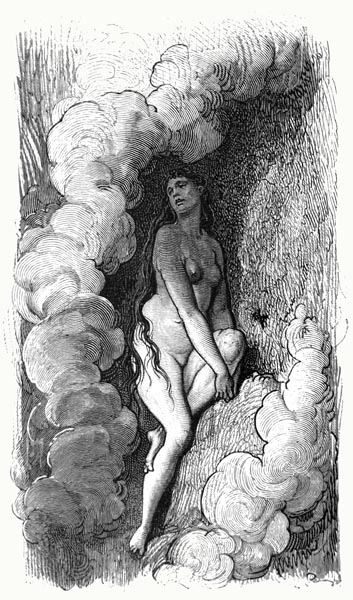

And thus, she began: ‘Lydia am I,

The King of Lydia’s noble daughter,

That, by the judgement of the Lord on high,

Am condemned to this darkness, forever,

Because a lover’s faith, his every sigh,

I met with ingratitude, and scorned him ever;

While countless others fill the cave below,

Condemned by that same sin, to the same woe.

Deeper still you’d find Anaxarete,

Who scorned Iphis, great is her suffering;

Turned to harsh stone was her living body,

Her spirit was sent here to feel the sting

Of seeing her lover, eternally,

(That killed himself for love of her) hanging.

Nearby is Daphne, who scorned Apollo,

Yet erred, in fleeing one that loved her so.

It would take long to name them, one by one,

The shades of the ungrateful women here,

If I but told of them, as I have done,

An endless number haunt these depths, I fear;

Longer still to tell of the men undone,

Damned, by ingratitude, to many a tear,

That in a fouler place may thus repent,

For those the harsh smoke blinds, and flames torment.

Since women oft prove the more trusting,

Men that deceive them, should suffer more.

There are Theseus and Jason, ever groaning,

And Aeneas that, in Latium, made war,

And Amnon that, fair Thamar abusing,

Led Absalom swift vengeance to ensure.

Many another haunts this place of strife,

That abandoned a husband or a wife.

But to speak of myself, and no other,

And reveal the sin that brought me here,

Lovely when alive, yet still haughtier

Than beautiful, was I, without a peer;

Nor do I know now which was the greater,

My beauty or my pride; both cost me dear;

For it is certain that my pride was born

Of a loveliness that no man might scorn.

Canto XXXIV: 16-19: She tells of herself and her suitor Alcestus

At that time, there lived a brave knight in Thrace,

In warfare, the most valiant of men,

Who, by many a witness to my grace

Was told of my beauty, and so often

That he desired to gaze upon my face;

(His longing and desire were most sudden)

Thinking that mere valour, on his part,

Was more than enough to win my heart.

To Lydia he came, and by so strong

A love was snared that he remained.

And great renown he earned there, ere long,

Amidst the other knights my sire maintained.

His valour and his deeds, worthy of song,

Would take too long to tell, who had obtained

Far greater reward if he’d but served

One who had honoured him as he deserved.

Through him, Pamphylia, and Caria,

My father conquered (who, scarcely ever,

Himself led out his men) and Cilicia,

(For this knight directed all with valour).

He, believing that none was worthier,

Deeming he had earned it, pressed my father

To grant him my hand, as his just reward

For the victories gained for his new lord.

His request was rejected by my father,

Who intended his daughter to be wed

To one of higher rank, not some warrior,

Who owned courage alone it must be said;

For my father was bent on gain, and further

A slave to greed, all vice’s fountainhead,

And he esteemed courage just as highly

As the sweet sound of the lyre the donkey.

Canto XXXIV: 20-24: Alcestus turns against her father

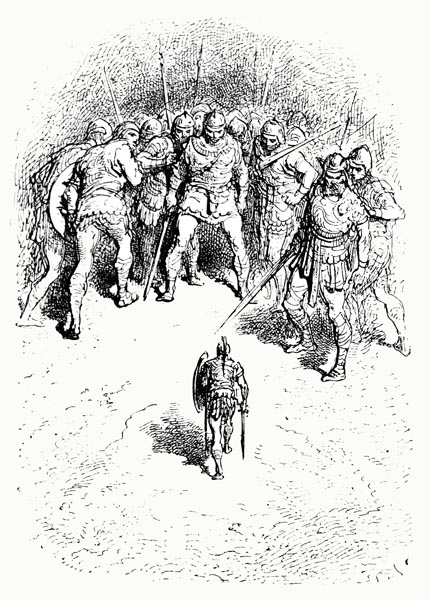

Alcestus (such was the warrior’s name

Of whom I speak), finding his suit denied,

Repulsed by one he thought would now proclaim

Himself his debtor, and see him gratified,

Sought leave to go; the gross slight to his fame,

He threatened to avenge; with wounded pride,

He sought the court of Armenia’s king,

Our rival, and arch-foe in everything.

And he so roused that monarch he made war,

Sent out his troops, and attacked my father,

While Alcestus, given his deeds and more,

Was named his champion, and their leader.

The knight declared that he would now secure

Possession of our lands for Armenia,

Only asking that, when he’d conquered all,

Myself to him should, as his guerdon, fall.

I can scarce express the great harm he wrought

My father in that war; four great armies

He overthrew, and such fierce battle sought

That in a year he’d conquered all, with ease,

Our lands and castles lost, except one fort,

Sited on high cliffs, that he might not seize,

And here with a chosen few, my father

Took refuge with the wealth he could gather.

This keep Alcestus besieged, and swiftly

Drove my father to such desperation,

That the latter would have granted me

To this foe with, indeed, half the nation,

If by my marriage, nay my slavery,

He might retain his wealth, and high station;

Else the loss of his riches he foresaw,

For he would die a captive, he felt sure.

To forestall, by every means, his defeat,

And thus attempt every last remedy,

He sent myself, the cause of this complete

Disaster, forth to meet my enemy.

I went to yield myself, fall at his feet,

And grant him thus my person utterly,

With whatever of our realm he sought,

If it but brought us peace, and calmed his thought.

Canto XXXIV: 25-30: Lydia persuades him to relent

Now, when Alcestus heard that I drew near

He came to meet me, trembling and pale,

More prisoner than conqueror did appear,

With bashful look, for there did Love prevail.

I, perceiving his ardour, and his fear,

Did myself of this passion now avail.

Seizing the sudden opportunity,

Offered by his state, I changed my plea.

I began by speaking ill of his manner,

And the cruelty he’d shown towards me,

Of the disloyalty he’d shown my father,

And that by violence he’d sought to gain me,

That would have welcomed him as a lover

Nor delayed many days, if only he

Had behaved towards us as at the start,

Whereby he had conquered many a heart.

If the honest request that he had made,

Had at first been denied by my father,

Well, he never a greater warmth displayed

On initial request, twas his nature;

But he himself should, indeed, have delayed,

And not fallen prey to such deep anger,

And by showing restraint would have acquired

The reward, for all his labours, he desired.

And if he’d still been thwarted thereafter,

I would have prayed my sire, earnestly,

To make a son-in-law of my lover;

And had he proved as obstinate, with me,

I’d have done for Alcestus moreover,

What would have satisfied him, secretly;

But since he had now turned to force instead,

No thought of loving him was in my head.

And if I came to him, moved so to do

By my deep respect for my dear father,

He might be sure he’d not long pursue

Violence against me, seeking to plunder;

For my death must swiftly then ensue,

Should he seek to gain what he was after,

And thereby achieve upon my person

What by force alone could thus be won.

Such words, and the like, I thus employed

Seeing the power that I now possessed;

His penitent pleas more than those deployed

By any hermit saint, ranked with the blessed.

At my feet he fell, with a blade he toyed,

That he had by his side, then addressed

Its hilt to me, and begged me to avenge

His most grievous fault, and gain revenge.

Canto XXXIV: 31-34: Alcestus restores all he has gained

Since I’d won so much, I sought to pursue

My swift and welcome victory to the end.

And gave him hopes of being worthy to

Enjoy the fruits of love should he amend

His former fault, restore to us anew,

Our wealth and kingdom, as an honest friend,

And, in time to come, enjoy my charms

Through loving service, not by force of arms.

All this he promised, and then returned me

To our fortress, as intact as I’d arrived,

Nor did he even venture to kiss me.

Was he not yoked securely? He derived

His pleasure from Love’s longing entirely,

Love who had slain him, though he’d survived!

He took himself to the Armenian king,

To whom the least of spoils he yet must bring;

In his most courteous manner, he besought

The king to grant our realm to my father,

Over which he had campaigned, in short,

And rest content with the former border.

The monarch answered no, that all he’d brought,

As gains from the war against that other,

Must be retained, and war he would demand,

Till his foe possessed not a foot of land;

And if a vile woman had persuaded

This change of heart, then let her bear the cost,

He himself would never be dissuaded

From retaining the lands her sire had lost.

Alcestus asked again, his deeds paraded,

And then complained, finding himself star-crossed,

Of this rejection, threatening in due course

To restore them with consent, or by force

Canto XXXIV: 35-40: Lydia seeks to destroy him

Their anger so increased that they passed

From mere ill words to many a worse deed.

Alcestus took to battle, at the last,

(Thousands flocking to aid the king, at need)

And, slew him, despite the troops amassed,

Making many an Armenian bleed.

Aided by Cilicians and Thracians,

And mercenaries of other nations.

He pursued the victory and, at his cost

Without his asking aught of my father,

He restored all the lands that we had lost,

In a month, and to pay for the slaughter,

Beside the splendid spoils, his gifts he glossed,

By taking the whole of Armenia,

And Cappadocia, on our border,

And, to its shore, scouring Hyrcania.

In place of a triumph, we thought to slay

The victor on his return, suddenly,

And yet fearing failure, we chose delay,

For he’d amassed friends far too readily.

Feigning love for him, from day to day,

I nurtured his fond hopes of wedding me,

But said I’d have him fight against the foes

That remained, and prove his worth against those;

And alone, or with but few, had him ride,

On many a strange and perilous campaign,

On which a thousand knights might have died,

Though, victorious, he’d thence return again,

Or I’d send him through all the countryside

To fight the monstrous creatures e’er our bane,

The fierce Giants and the Laestrygonians,

That infested our and others’ nations.

Hercules was ne’er sent on such a chase,

By Eurystheus, or Juno ever,

On Erymanthus, in Nemea, Thrace,

Lerna, Numidia, Aetolia,

By Tiber, Ebro, or some other place,

As I decreed, to exercise my lover,

With feigned pleas, and murderous intent,

Hoping that his demise I might lament.

Lacking the power to gain my foremost aim,

I devised a scheme with no less effect:

He brought harm to all who had praised his name,

And, thus, was hated by that injured sect,

For he was pleased to work that very same,

Enacting all I asked, without respect

To whether they were friends; a sign from me,

And all, alike, became his enemy.

Canto XXXIV: 41-43: She causes him to sicken and die

Once I perceived that every mortal foe

Of our House had been eliminated,

And Alcestus conquered by himself, also,

Whose every friendship was terminated

Through our efforts, I did the mask forego;

Discarded the fondness I had imitated,

Revealed the hatred behind every breath,

And that I sought to bring about his death;

Aware that if I did so, I would know

The burden of public ignominy,

(Too many knew my debt to him, and so

Would deem my actions born of cruelty);

It seemed to me enough to see him go,

Offend my eyes no more, exiled from me;

Nor would I view, or speak to, him again,

While messages, or letters, I’d disdain.

My ingratitude caused him such suffering,

That, at last, overcome by deepest woe,

Seeking mercy in vain, then sickening,

He sank to death, neath the weight of sorrow.

Through this punishment, of my own making,

My face is blackened, my tears overflow;

Such my eternal fate, here must I dwell,

For none are redeemed from the fires of Hell.’

Canto XXXIV: 44-46: Astolfo blocks the entrance to the cave

Since the hapless Lydia spoke no more,

Astolfo thought to find what lay below,

But the dense, and bitter, fog, that stretched before

His eyes, decreed no further might he go,

Not a yard could he now descend, therefore

Our knight returned above, nor was he slow

To deliver himself from that seething deep,

But, hastening to the light, he climbed the steep.

He moved at a run, not a walk or trot,

And, fleeing swiftly, as if out the grave,

He sought his exit from that dismal spot,

And mounted to the entrance of the cave,

Where, through the smoke and mist, those ingrates’ lot,

The light of day now shone, that they did crave.

After serious effort, and well-nigh blind,

He issued forth, and left the fumes behind.

Then, to bar the way against the Harpies,

Whose greed drove them to attack the food,

He gathered stones, cut branches from the trees,

(With cardamom or pepper all imbued)

And built a sort of rugged fence with these,

Before the cave, to thwart that hellish brood,

And so successful did his efforts prove,

The monsters could, no more, emerge above.

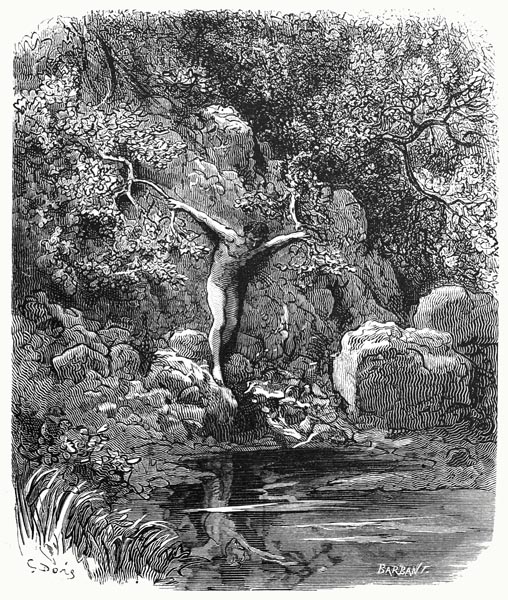

Canto XXXIV: 47-52: Then climbs to the mountain summit

The smoke, as of burning pitch, dense and black,

That had obscured his sight in the cavern,

Had not only soiled his clothes, front and back,

But had sunk to the flesh, at bow and stern,

He sought for some stream, beside the track,

To cleanse himself and, at last, neath a fern,

Found a rill, born from the rock, that filled a rut

By a tree, and washed himself, head to foot.

Then he mounted the hippogriff, and rose

Through the air, to reach the mountain summit,

Which to him seemed close enough, heaven knows,

To the moon’s far sphere, and all within it,

And such a longing to see it now arose,

He aspired to the heavens, Earth would quit,

To reach the sky, every nerve he strained,

And, thus, the mountain-top they attained.

Topazes, sapphires, rubies, pearls, and gold,

Diamonds, chrysolites, and jaspers, set on

The heights, like glowing flowers, he did behold,

Catching the light that on their surface shone,

The grass so green that, if some field or fold

It clothed down here, see emerald foregone,

Its colour we’d prefer; while no less fair

Blossom, leaves, and fruit its trees did bear.

Amidst the branches fluttering, birds did sing,

Their hues of azure, white, green, yellow, red;

A peaceful lake, its clear waters showing

Brighter than crystal, murmuring freshets fed;

While a sweet breeze there, forever blowing,

In gentle fashion through the branches sped,

Making the pure air tremble, all around,

To quell the heat of day, and cool the ground;

Plundering the odours from fruits and flowers,

And from the foliage each varied scent,

Forming a fragrance from those pleasant bowers,

That filled the soul with sweetness and content.

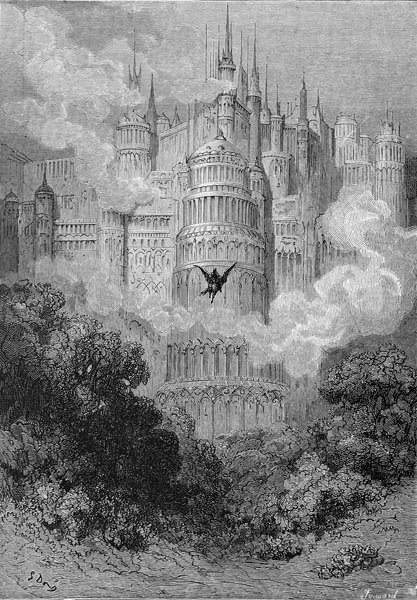

There, on the heights, a palace, with its towers,

Uprose, to which some living flame had lent,

It seemed, such splendour, a glow so bright

That, beyond mortal fashion, shone its light.

It covered more than thirty miles around,

And towards it Astolfo turned his steed,

Moving slowly, at his ease, o’er the ground,

(All, to his gaze, seemed beautiful indeed)

And thought that all that down below was found

In wrath Heaven and Nature had decreed;

Brutish and ugly, this sad world we face,

So sweet and clear and happy was that place.

Canto XXXIV: 53-57: Where he encounters Saint John

As to that bright palace he drew near,

Astonished, on its wondrous walls, he gazed,

Wrought from a single gem they did appear,

That, redder than ruby, the eye amazed.

What mighty work, Daedalian art, is here?

What palace below could, thus, be praised?

Be silent those who exalt the glory

Of the Seven Wonders, famed in story!

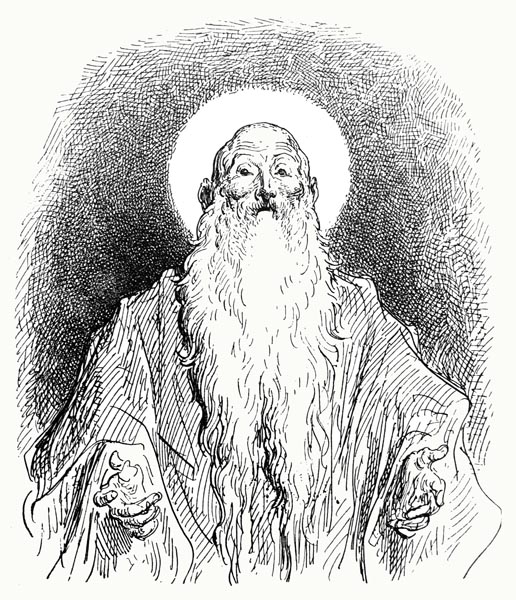

An elder, from the gleaming entrance-hall

Of that fair house, strode towards Astolfo,

White his robe, crimson his mantle all,

The mantle as red-lead, the robe as snow;

White was the elder’s hair, and white did fall

His bushy beard down to his chest also,

So wise and kindly seemed his face, his eyes,

He seemed of the elect of Paradise.

To Astolfo who’d humbly descended

From his steed, he, with glad face, now cried:

‘O noble knight, you who have ascended

To our earthly paradise, God your guide,

Though you know not why it is you wended

Your way here, nor to what end tis applied,

Believe: profound mystery brings you here,

Drawing you from your northern hemisphere.

You are brought here to learn, from my counsel,

You who without counsel have long journeyed,

How to Charlemagne, and the Church as well,

You may bear succour, by such counsel led.

Not to your wits, nor skill, all that befell

Should you ascribe, nor the course you sped,

Nor to your winged steed, your magic horn,

For God alone has brought you to this bourne.

We will converse together, you and I,

And I will tell you how you must proceed,

But first find ease, and to our board apply

Your thoughts, for food and drink you surely need.

And continuing his speech, by and by,

He set our knight to marvelling indeed,

For his revered name, thus, his lips disclosed,

And that he the fourth Gospel had composed.

Canto XXXIV: 58-62: With Enoch and Elijah

Twas John, so beloved of the Redeemer,

His role questioned by Peter, of whom some

Said that he would ne’er see death; however,

‘If I will that he tarry, till I come

What is that to thee?’, rebuking Peter,

Were the words of The Son of God, wherefrom,

Though He did not say John would not die

It is clear that was what He meant thereby.

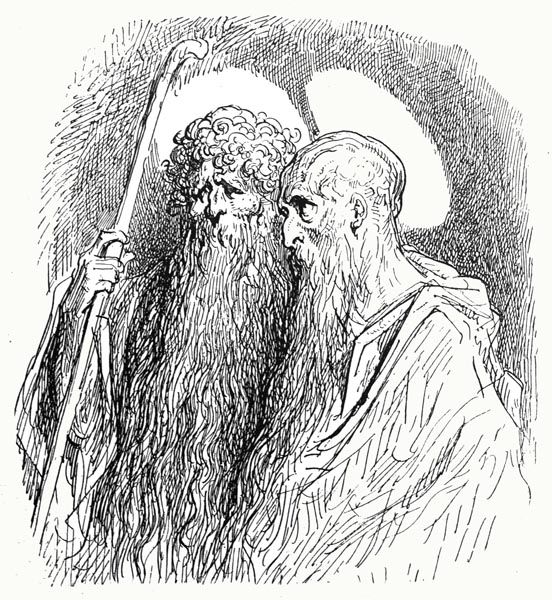

Led within, the duke encountered there,

Enoch, the patriarch, in company

With Elijah the prophet; none would share

Death’s last corruption, of these holy three,

But, far from all foul and pestilential air,

Would ever that perpetual springtime see,

Until they heard the Angel’s trumpet blow,

And Christ returned, amid the white clouds, so.

With a welcoming grace, the ancients led

The knight to a palatial chamber,

And stabled his good steed, where it was fed

On fodder enough for any creature,

While he gave his attention to the bread

And fruits of paradise of rarest savour,

Such that our first parents might be excused

If, to gain such, God’s edicts they abused.

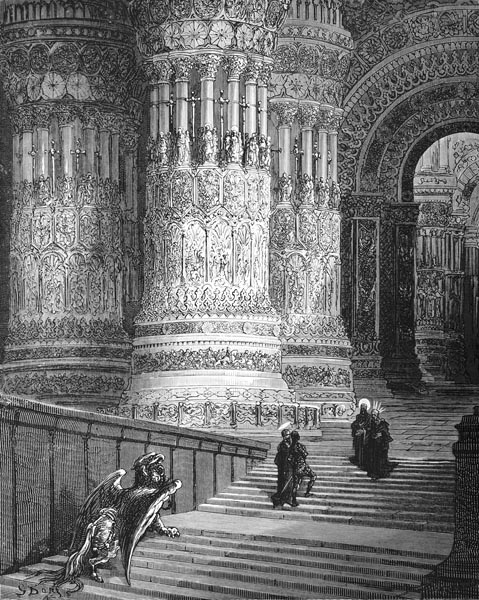

![Ariosto - Orlando Furioso - Canto XXXIV: 60 [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Italian/interior_ariosto_orlandofurioso_cantoxxxiv60b.jpg)

When Astolfo had paid the debt we owe

To Nature, both in food and in sweet rest,

(For he found a calm repose there also)

And Aurora had left her spouse’s breast,

(Burdened with years her prince, beloved though)

Our knight-errant rose from his bed, and dressed,

And issuing forth, met, with true delight,

The apostle he’d seen the previous night,

Who took his hand; spoke of many a thing

That’s worthy of reverent silence here;

And then said: ‘Son, of events happening

In France you as yet know little, I fear:

Learn that your Orlando, now straying

From the true path decreed it would appear,

Is punished by the Lord who will descend,

In wrath, on those He loves, if they offend.

Canto XXXIV: 63-68: Astolfo learns of Orlando’s mad frenzy

To your Orlando, at his birth, God gave

Sovereign courage, and sovereign might,

And more than mortal hide, destined to save

Him from hostile blades in many a fight;

For the Lord set the Count amidst the brave

To defend Holy Church, and all that’s right,

As, against the Philistines, He did choose

That mighty Samson, to defend the Jews.

Your Orlando for such great gifts has made

An ill return unto his Heavenly Master,

Quitting his people though they need his aid,

And vanishing from their sight thereafter,

So blinded by love for a pagan maid,

That twice at least this great warrior

Has attempted in cruel and wicked strife

To rob his faithful cousin of his life.

For this God has maddened him, and now

He goes naked, with chest and flanks all bare,

While his head is so empty, I avow,

That none, least of all himself, knows him there.

In that manner did Nebuchadnezzar bow

To the ground, and then at the grass did tear,

Like a bull, for seven years, in mad fury,

At God’s decree, as we read in story.

And yet because your maddened warrior,

Has transgressed against his Creator less,

Tis for a mere three months he needs suffer

The punishment for error and excess.

Tis, to address this matter, and no other

That the Redeemer did your journey bless,

So that we the swiftest means might show

Of restoring sense to your Orlando.

You’ll need to journey far with me, tis true,

And thus, abandon this Earth completely,

For tis to the moon’s sphere I must lead you,

Set nearest to ours, since the remedy

For his sad affliction, there, you may view,

That which will cure his madness most swiftly.

And when, this night, the moon sheds its bright ray

Upon our heads, we’ll set out on our way.’

On this, and many another matter,

The apostle discoursed, till day was done.

But when above their heads the moon did glitter

And to the Ocean depths had fled the sun,

A chariot was prepared, used by another

To soar through the sky, for twas the one

In which, from the mountains of Judea,

Had sped, lost to mortal sight, Elijah.

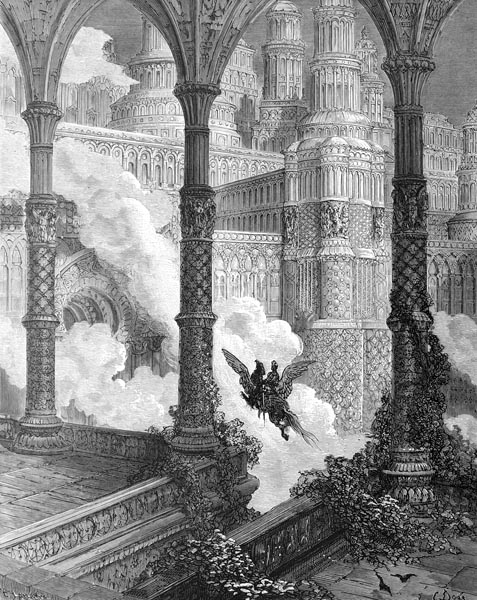

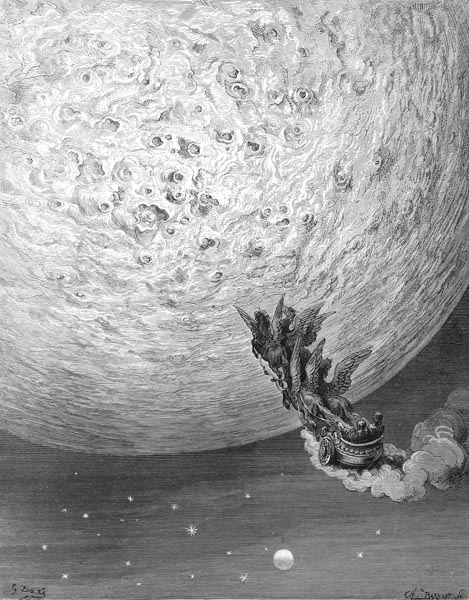

Canto XXXIV: 69-72: He journeys to the moon

Four horses, redder than flame, the saint led

To the chariot, and then prepared to fly,

For, once he and Astolfo were seated,

He took the reins, and sped towards the sky,

Rising, in wide circles, oft repeated,

Till they had reached the realm of fire, thereby,

Its heat miraculously suspended,

By the evangelist, whilst they ascended.

So, through all that fiery region, they passed,

Soaring swiftly to the moon’s sphere above,

Which they saw, when they had reached it at last,

Like to unblemished steel did mostly prove;

And found the size of what was there amassed

(Or the half that they could see, at that remove)

Much the same as distant Earth’s to the eye,

Comprising our seas, and the part that’s dry.

For the knight was doubly surprised to see

Its surface was so large viewed close at hand,

Which seemed a little orb, when seen fully,

From the enormous Earth on which we stand,

While forced to strain his eyes to view clearly

How Earth’s distant oceans embraced the land,

That, from the arc subtended by its light,

Appeared quite small at that wondrous height.

There other rivers, lakes, and countryside,

Are seen than those which we view here below,

Other valleys, plains, and mountains are descried,

Whole cities, towns and castles, there on show.

With houses of such splendour that, beside

Their majesty, our own seem base and low.

Broad, solitary woods also feature,

Where nymphs pursue every kind of creature.

Canto XXXIV: 73-82: And reaches a vale where all things lost from Earth go

The duke stayed not to gaze upon them all,

Since he’d not journeyed there for that reason,

But followed the apostle, at his call,

Towards a vale where, twixt hill and mountain,

Those things we have lost beyond recall

On Earth are found, miraculously, again

Retrievable; all things lost by error,

Down here, through time or chance, whole as ever.

Not just of crowns, or treasure, do I speak,

O’er which the ever-moving wheel holds sway,

But that too o’er which Fortune’s power is weak,

Unable to grant such, or sweep it away.

Fame and renown are here, that many seek,

Things slowly gnawed by time, and by decay;

Here countless idle vows, and prayers lie,

Made by us sinners to the Lord on high;

And many a lover’s sigh, many a tear,

All the long idleness of foolish men,

All the time we lose in gaming here,

And vague plans made, and never seen again.

Our vain desires are such that they appear

To cover a vast portion of that glen;

For all that, on Earth, you’ve lost entirely,

You’d find there, if you but made the journey.

Passing through things piled on every side,

The meaning of the various heaps he sought;

Of a great mound of bladders, asked his guide,

From which rose cries and tumult, and was taught

That ancient realms lay there, concealed inside,

Assyrian, Lydian, with conflict fraught,

Or Greek, or Persian, famous in their day,

Whose very names swift Time has washed away.

A mass of gold and silver gifts, he saw,

The kind that courtiers offer to their lord,

Hoping to win their favour, or far more,

Those to king, prince, or patron, they afford.

Many a garlanded snare, that vale bore;

Of such signs of adulation, vast the hoard.

While from the loud cicadas poured forth verse

Poets had made to praise their lords, or worse.

Knots of gold, and jewelled stumps he found

The remnants of unhappy loves, ill-starred.

And many an eagle-claw did there abound,

To show the power invested in some guard.

Bellows filled every patch of barren ground,

Their fumes the favours graceless king’s discard

They once granted some Ganymede, whose hour

Has passed, whose springtime ceased to flower.

Ruined castles, cities, and lost towns lay there,

With all their wealth; he, on request, was told

They were emblems of treaties, and the bare

Dust of cunning plots, that failed to unfold.

Serpents with women’s faces found a lair

In that place, and coiners, and thieves untold,

While broken bottles, of many a varied sort,

Marked fair service at some graceless court.

He saw a huge puddle of soup, and sought

To know what that liquid signified,

And learned twas almsgiving, one last thought,

Of those folk who had willed it, and then died.

He passed a pile of flowers that had brought

Scent to the air, and now stank far and wide;

Much like that list, of gifts, left to fester,

That Constantine granted Pope Sylvester.

He saw a great lake of viscous birdlime

The which, ladies, signified your beauty!

Twould take too long to relate in rhyme

All the things he saw there, in that valley,

Viewed thousands upon thousands, at a time,

The results of our lives, each casualty;

Yet little or no sign of that madness

Rarely absent from Earth one must confess.

He turned back to search for some day or deed

Of his own, that had vanished long ago;

Lost, without his interpreter to read

Its form much altered from that down below.

Then he came to that which all are agreed

They need none of, since they seem so slow

To ask the Lord for more; I speak of sense,

Of which the pile was even more immense.

Canto XXXIV: 83-87: He finds Orlando’s store of sense

It was like a thin and subtle liquor,

Evaporating if not well-enclosed,

Collected in vessels, large or lesser,

As required, that all about were disposed.

In one flask, larger than any other,

Was the Count’s vast store of it, he supposed,

For there he found, written on the side,

‘Orlando’s Sense’ in letters tall and wide.

And there were labels too on all the rest,

That revealed whose sense was bottled within.

A great part of his own was there a guest,

But he was more amazed to see, therein,

That of folk of whom he’d ne’er have guessed

That they’d lost a drop; yet, with some chagrin,

He saw, clearly, they had scant sense to spare,

Considering the amount that was there.

Some lose theirs in love, or seeking honour,

Some scouring the seas for rich merchandise,

Some pin their hopes on a wealthy master,

Others lose theirs in dreams of paradise,

Some buy works of art, or gems they gather,

Or lose theirs on what seems the highest prize.

Astrologers’ and sophists’ sense they bore,

Those vessels, and many a poet’s he saw.

The author of the Book of Revelation

Granting consent, Astolfo took his own;

And to his nose raised the distillation

Till, to its proper place, his sense had flown.

Henceforth Bishop Turpin’s indication

Is that he was wise, as far as is known,

All his days, until a further error

Deprived him of his brain altogether.

The vessel that contained Orlando’s sense,

He took; twas the amplest, and the fullest,

Though heavier when he took it thence,

Than it had seemed when heaped amidst the rest.

Ere his earthward journey he could commence,

From that sphere of light to our own sad nest,

The evangelist led him, still his guide,

To a fair palace by the riverside.

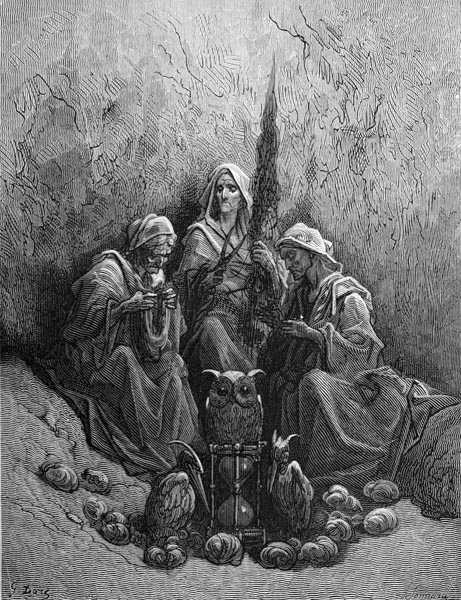

Canto XXXIV: 88-92: The Palace of the Fates

Bales of raw cotton, flax, silk, and wool

Filled every single chamber of that same,

And all of various shades, bright or dull.

In the first cloister, a white-haired dame

Thread for her spindle, from a bale, did cull,

As on a summer’s day a view we claim

Of some villager twining the damp thread

From the silk-worms, thus to her spindle fed.

When one bale was finished, came another

Dame, replaced it, and bore the work away.

A third, from all the threads twined together,

Picked the fair from the foul in close array.

Astolfo asked Saint John: ‘All their labour,

What purpose has it?’ The saint paused, to say:

‘They are the Parcae, whose powers are great,

For here are spun the threads of mortal fate.

As long as each single thread might extend

So long lasts that one life, and no longer,

For Nature and Death pay heed to its end,

To know the hour when that life is over.

The fairest threads the third dame will commend,

Which are woven into many things, thereafter,

To adorn paradise; while the lesser

Serve as cruel bonds, the damned to fetter.

On each spindle, on which thread was wound,

Which had been marked for further attention,

A name, engraved on a small plate, was found,

These plates of gold, or silver, or iron.

And there were heaps of these, upon the ground,

That were ne’er reduced enough to mention,

Though an old man, unwearied, ever bore

Some of these thence, and then returned for more.

This old man was so nimble and slender

He seemed from birth made for such exercise.

As, from those heaps, he gathered, forever,

In his cloak the names, engraved in such wise.

Where he went, and the aim of his labour,

The next canto shall reveal to your eyes,

If you would but grant, and so commend me,

The kind attention, that you now extend me.

The End of Canto XXXIV of ‘Orlando Furioso’