Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXIII: Merlin's Prophetic Art

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXIII: 1-5: Ariosto on depictions of things to come

- Canto XXXIII: 6-12: Merlin’s prophetic art: Faramund

- Canto XXXIII: 13-15: Merlin’s prophetic art: Childebert II to Childebert III

- Canto XXXIII: 16-20: Merlin’s prophetic art: Pepin to Charles of Anjou

- Canto XXXIII: 21-24: Merlin’s prophetic art: Jean de Armagnac to Charles VIII

- Canto XXXIII: 25-30: Merlin’s prophetic art: Alfonso d’Avalos future Sixth Marquis of Pescara

- Canto XXXIII: 31-33: Merlin’s prophetic art: Alfonso d’Avalos Fourth Marquis of Pescara

- Canto XXXIII: 34-41: Merlin’s prophetic art: Louis XII’s Italian Wars

- Canto XXXIII: 42-44: Merlin’s prophetic art: Francis I

- Canto XXXIII: 45-53: Merlin’s prophetic art: The Battle of Pavia

- Canto XXXIII: 54-57: Merlin’s prophetic art: The Naval Battle of Capo d’Orso

- Canto XXXIII: 58-64: Bradamante’s vision of Ruggiero

- Canto XXXIII: 65-76: She jousts again with the three kings at their request

- Canto XXXIII: 77-78: She hears news of King Agramante’s flight from Paris

- Canto XXXIII: 79-83: We return to the duel between Rinaldo and Gradasso

- Canto XXXIII: 84-88: A flying creature appears and Baiardo flees

- Canto XXXIII: 89-92: Rinaldo fails to find the steed

- Canto XXXIII: 93-95: Gradasso succeeds, and sails for home

- Canto XXXIII: 96-102: We turn to Astolfo who reaches Ethiopia

- Canto XXXIII: 103-112: Senapo, Emperor of Ethiopia (called Prester John)

- Canto XXXIII: 113-116: He begs Astolfo to alleviate his plight

- Canto XXXIII: 117-125: Astolfo rids the king of the Harpies

- Canto XXXIII: 126-128: And sends them fleeing to Hades

Canto XXXIII: 1-5: Ariosto on depictions of things to come

Timagoras, Parrhasius, Timanthes,

And Protogenes, and Polygnotus,

Apollodorus, and the great Apelles,

First among them, and Zeuxis; all famous

Painters of their age, the names of these

(Despite Atropos who takes life from us,

And often our works as well) will survive,

While writers keep their memory alive;

And of those renowned in our own day,

Mantegna, Gian Bellini, Leonardo,

The Dossi, and (in sculpture too, I say,

Not man but angel) Michaelangelo,

Titian, Bastiano, Raphael (they

Who’ve adorned Venice, Florence, Urbino)

And others, their yet-living works shine so

We grant like power to those lost long ago.

The things that we see now, artists portray,

As artists did two thousand years before,

On wall or wood, yet never could convey

Things of the future, only what they saw.

The ancient masters had, ours have, no way

Of viewing what’s to come; though, to be sure,

There are things and deeds known to history,

Which were depicted ere they came to be;

Yet no artist can, or could, possess the skill

To create such works, nor can the credit take;

Tis the enchanter’s art, spells cast at will,

That can cause the infernal shades to shake

With fear; so, the chamber, I speak of still,

Wise Merlin, with demonic aid, did make,

(Chanting from a book, to Norcia’s grotto

Sacred, or to Avernus’ Lake, below),

All in a single night. The art displayed

In ancient times which such wonders wrought

Is lost to ours; I speak of things portrayed

Upon those walls. Torches now lit the court,

That dispelled the dark around, every shade

Dismissed completely, and so served, in short,

To fill with splendour, and glorious light,

The chamber, that by day was ne’er so bright.

Canto XXXIII: 6-12: Merlin’s prophetic art: Faramund

The castellan now spoke: ‘I’d have you know

That, of the battles you see here portrayed,

Few have been witnessed, for these paintings show

Events not yet enacted; here, arrayed,

Are the works of that sage who did foreknow

The victories, the defeats, in paint displayed,

That the armies of Italy shall see,

And you may view, ere they are history.

The wars the Franks would wage, for good or ill,

Beyond the Alps, for a good thousand years

From his day, Merlin showed; here are they still,

Here his prophecies we view, here each appears;

For Arthur, Britain’s king, had him fulfil

The task for Faramund, who was Marcomir’s

Great heir; and why the king decreed that day

That Merlin must so labour, I shall say.

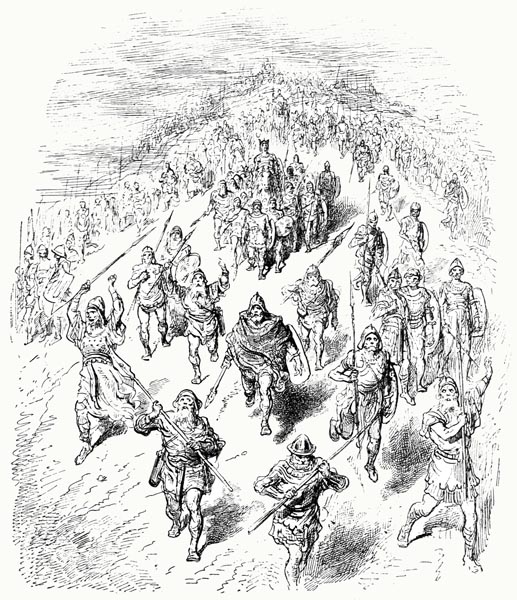

King Faramund, the first of those who crossed

The Rhine, entering Gaul, with his great army,

Once it was occupied for little cost,

Thought how he might rein in proud Italy.

That the Roman Empire had all but lost,

Or was fast losing, power he could see,

And so, with his peer King Arthur, he sought

To act in league, and compass this, in short.

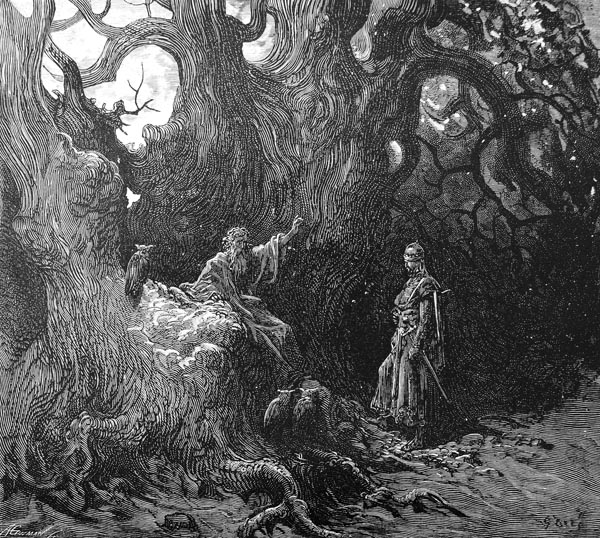

Arthur (who never wrought a single thing

Without prophetic Merlin’s wise counsel,

Merlin, the Devil’s son, he who could sing

I say, of future deeds) now sought to tell

Faramund of the danger he would bring

To his armies, and his own realm as well,

If he entered that land the Apennines

Divide, the Alps bound, and the sea confines.

For Merlin had revealed that almost all

The future kings destined to rule in France

Would see their ill, exhausted armies fall

Through famine, fever, war by such advance,

And that but little joy, great sorrow, small

Profit, and a deal of harm, perchance,

Italy would yield them, for the lily

Would fail to take root in that proud country.

Faramund had such trust in the royal word,

That he turned his mind to other conquest,

For Merlin who saw (as the king had heard)

Past, present and future, was now his guest.

The paintings on this chamber he conferred,

Through his magic, at Faramund’s request.

Here every deed of the Franks, in the field,

As if already wrought, would be revealed.

And, thus, his successors might comprehend

That victory and honour would be won,

If they but sought to muster and defend

Italy gainst barbarous incursion;

While if they simply sought to descend

Upon her to enforce their dominion,

They might there foresee their armies’ doom,

And that beyond the Alps lay but a tomb.’

Canto XXXIII: 13-15: Merlin’s prophetic art: Childebert II to Childebert III

Saying so, he then led the ladies where

The painted history commenced; to view

Childebert the Second venturing there,

The Emperor Maurice’s offer to pursue;

Behold him, descending from Alpine air,

Whence the Ticino and Lambro issue.

See Clothar the Second deter his foe,

Then put them to flight, conquering so.

See Clothar the Third’s army cross the pass

With more than a hundred thousand men,

And the Duke of Benevento face, en masse,

The mighty foe, yet drive them back again;

See him feign to retreat, then reap like grass

The Franks that seek to win the Lombard plain.

To shame and death they go, drawn to the wine,

And caught like mullet, without net or line.

How many Childebert the Third now sends,

Led by his generals, into Italy!

Yet no more than Clothar achieves his ends,

Failing to rape and conquer Lombardy;

For Heaven’s sword so weightily descends

On his men, their corpses clog the country,

Slain by the flux, and the heat of the sun,

So that of every ten there’s left but one.

Canto XXXIII: 16-20: Merlin’s prophetic art: Pepin to Charles of Anjou

Pepin the Short, he showed, and Charlemagne

Descending again into Italy,

And how each some success would there obtain,

Because both sought to ensure her safety;

Pope Stephen, Pope Adrian, they’d sustain,

And Leo the Third defend from injury;

The one would conquer Aistulf, the other

Desiderius, gaining the Pope honour.

He showed young Pepin of that royal line,

Whose mighty host would appear to cover

The sea from Venice’ shore to Palestine;

He would build a costly bridge, moreover,

At Malamocco, to cross o’er the brine,

Reach the Rialto, and seek to conquer,

But be forced to flee, leave his men to drown,

His fine bridge, by the wind and sea, brought down.

Behold how Louis of Provence descends

To where he first conquers, then is taken;

And, to guarantee he no more offends,

Must swear his warlike plans now forsaken.

Behold, he breaks the oath, for his own ends,

And falls once more into the snare, mistaken

In his aims; then, by his foes rendered blind,

Borne o’er the Alps, leaves Italy behind.

See Hugh of Arles do many a great deed,

And from Italy expel the Berengari.

Yet, now Huns, now Bavarians, succeed,

Defeating him twice or thrice utterly.

He is now forced to sue for peace, indeed,

Not surviving long, nor his heir, we see,

Leaving Berengar of Ivrea to rein,

He possessed of his kingdom once again.

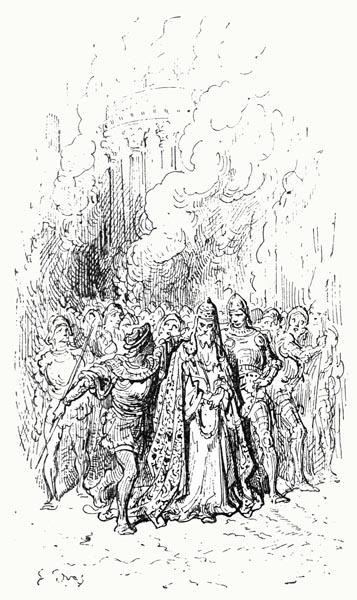

Behold another Charles, he of Anjou,

Who, to save a Pope, sets Italy aflame;

A pair of kings he slays, behold, the two,

Are brave Manfred, and Conradin, by name.

Yet his soldiers, who with vile wrongs (no few)

Oppress the land, to their and Charles’ great shame,

Scattered, here and there, throughout Sicily,

Are slain, as the Vesper-bells ring wildly.

Canto XXXIII: 21-24: Merlin’s prophetic art: Jean de Armagnac to Charles VIII

Then (though it seems not merely a few years

But many and many an age has gone by)

A Gallic captain o’er the Alps appears,

To war on the famed Viscontis, thereby;

And here, with foot and cavalry he nears

Alessandria’s walls, and a siege will try.

Gian Galeazzo garrisons the place,

And lays an ambush, clasps in his embrace

The French force under Jean of Armagnac,

Caught by the artful net that Duke has spread,

Such that, all around, felled by his attack,

Lie the Gallic soldiers, full many dead,

While the rest, that all hope of flight thus lack,

Prisoners, to Alessandria are led;

Thus, swollen now with blood, Tanaro’s flow

Sends crimson tribute to the River Po.

One named De la Marche, and three D’Anjou,

The warden showed, one upon another,

And said: ‘The Brutti, and the Marsi too,

The Daunians and Salentines, they bother,

But tis not Franks, nor Latini, renew

Their aid, nor their position recover;

As often as these Gallic foes attack

Alfonso, then Gonsalvo, drive them back.

Behold, here, Charles the Eighth descending

From the Alps, with all the flower of France,

Crossing the Liri, fair Naples conquering,

And yet without deploying sword or lance;

All but the isle, o’er Typheus lying,

Ischia, he takes in his bold advance,

Held, here, yet, by Iñigo del Guasto

Of the House of Avalos; a worthy foe.’

Canto XXXIII: 25-30: Merlin’s prophetic art: Alfonso d’Avalos future Sixth Marquis of Pescara

The warden of the tower, once their brief tour

Of those scenes was done, and he had named

That isle for Bradamante, said: ‘Before

You view aught else I’ll tell you what was claimed

By my great-grandfather, a thing of lore,

While I was still a child, which was proclaimed

To him alone, likewise, by his father,

And to his father by his grandfather,

And so twas told, by one or the other,

Starting from he that was the first to hear

These prophecies; recited, then, moreover

By him who’d had them magically appear,

Thus painted, in crimson, white, and azure;

When that enchanter made their meaning clear

To Faramund, who the isle’s name did learn,

And told the king what I’ll tell you, in turn,

He heard him tell how (in that very place

You see him defending with such ardour,

He seems to scorn the flames before his face,

That reach to the Pharo nigh the harbour)

From that knight a warrior of his race

Would spring (then or very shortly after;

Indeed, he named the year and week and day)

A warrior that all others would outweigh;

One who’d prove stronger than great Achilles,

Wiser than Nestor, both long-lived and sage,

More daring even than bold Ulysses,

Nimbler than Ladas, athlete of his age,

More generous, and readier to ease

The errant through clemency, and assuage,

Than was famed Caesar; Ischia’s delight,

Against whom others’ virtues would seem slight.

If ancient Crete rejoiced when Zeus was born,

Or Thebes, of old, when Dionysus, there,

And Bacchus did that famous place adorn;

If Delos the divine twins’ light did share,

Then no less glory would in time be borne

By Ischia, her head raised high in air,

She that this great Marquis would come to know,

On whom Heaven would every grace bestow.

Merlin said, and many a time repeated

That this Marquis was destined to arrive

In an age when the Empire, oft defeated,

Was much oppressed; a soldier born to strive

For liberty. But since I’ve not completed

Our review, I’ll not seek to so deprive

You; first, ere that valiant knight I hail,

With Charles I shall again take up the tale.

Canto XXXIII: 31-33: Merlin’s prophetic art: Alfonso d’Avalos Fourth Marquis of Pescara

Ludovico Sforza will soon regret

Inviting Charles to enter Italy,

Whom he summons but to aid and abet

Him in countering the bold Papacy,

Not to overthrow it; though in his debt,

On his return, he deems him an enemy.

He leagues with Venice, and yet his new foe

Despite him, his skill in war will show.

The king’s forces, remaining in command

Of his new realm, will meet another fate,

For Ferrante, Sforza’s defence in hand,

Will return to the fight, his strength so great

He’ll leave not a foreigner in his land,

Slays them all, on land and sea, and saves the state;

Yet through King Ferdinand’s ingratitude

Will be deprived of the honours he’s accrued.’

And then that lord, showing Bradamante

The portrait of Alfonso d’Avalos,

Fourth Marquis of Pescara, said: ‘When he

Shall have acquired the fame and gloss

Of a thousand deeds, bright as the ruby

Will he shine, yet men will mourn his loss,

Deceived by a Moorish slave’s treachery,

Pierced by a barb, departing thus the stage,

The finest knight and general of his age.’

Canto XXXIII: 34-41: Merlin’s prophetic art: Louis XII’s Italian Wars

And now Louis the Twelfth, escorted by

Italians, descending the Alps, they see,

Uprooting Il Moro’s mulberries, thereby

Planting, in Visconti ground, the lily.

‘Treading in Charles’ footsteps, by and by,’

Said the castellan: ‘strong bridges will he

Fling o’er the Garigliano, and yet later

Mourn his troops drowned in that fatal water.

See the French army there, again in flight,

Routed in Apulia, scourged, no less;

Gonsalvo Ferrante, bold Spanish knight,

Twice springs the subtle trap, and wins success.

Yet Fortune reveals to Louis her bright

Face; upon the Padan plain, grants redress,

Twixt Alps and Apennines, Agnadello

The field of war, close to the River Po.’

The host reproved himself for neglecting

To speak of first things first, and in order,

And returned to show the overthrowing

Of a strong keep betrayed by its warder;

Then a lord imprisoned after hiring

A Swiss traitor as his sole defender;

Which double-treason, without sword or lance

Grants swift victory to the King of France.

Cesare Borgia next he shows and names,

Raised to power, by that king, in Italy,

For all Rome’s lords, and all those lords she claims

As hers, he drives into exile, promptly.

The king will help the Pope meet his aims,

Driving Bentivoglio, ruthlessly,

From Bologna; then the rebel Genoese

He’ll put to flight, and that fair city seize.

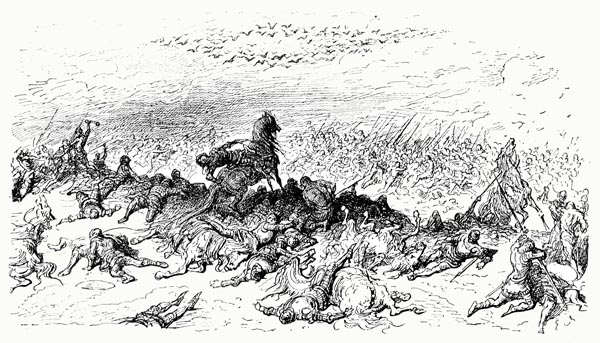

‘Behold,’ the warden said, ‘the many dead

That o’er the Gera d’Adda hide the field,

While each city opes to the king in dread,

And Venice herself scarce fails to yield.

See how he ignores the Pope, instead

Leaving Romagna’s confines; here revealed,

See Modena wrested from Ferrara’s lord,

Nor does he linger there, or rest afford,

But draws Bologna, now, to his party,

Which the Bentivogli then re-enter.

Next the French king lays siege swiftly

To Brescia, and accepts its surrender.

Then he promptly routs the Papal army

While yet bringing Bologna his succour.

And then it seems the hostile armies lie,

On Chiassi’s level shore, before your eye.

On this side France, and on the other Spain,

Engage their troops in battle, there we see

Many fall, on both sides, and with the stain

Of crimson blood paint the earth, and sadly

Dye every stream bright red, ditch, and drain.

Mars doubts to whom belongs the victory,

Till, Alfonso d’Este wins the field;

The French prevail, and the Spaniards yield.

The Pope bites his lips in woe and anger,

As his Ravenna is sacked, and brought low,

And draws German mercenaries, moreover,

O’er the Alps, to storm all the lands below.

While the French, unable to recover,

Are chased home, beyond the mountain snow,

Il Moro’s scion, there, ousts the lily

From his rich soil, replants the mulberry.

Canto XXXIII: 42-44: Merlin’s prophetic art: Francis I

Behold the French return, and here behold

One broken, by the faithless Swiss betrayed,

The same who had his father seized and sold,

Whom he had rashly summoned to his aid.

Here you see an army, o’er which has rolled

Fortune’s wheel, before the new king arrayed;

Francis the First prepares thus to efface,

In swift revenge, Novara’s late disgrace,

With better auspices the victory gains.

Tis Francis, at the head of his vast army,

That will ensure that not one Swiss remains

To thwart him, destroying them entirely.

Such that nevermore will they lay claims

To their title of defenders of the Holy

Faith, the Church, and the scourge of princes,

Borne by those whom it no more evinces.

Behold, despite the League, he takes Milan,

Then with the young Sforza strikes accord;

Here the Duke of Bourbon fights man to man

To keep that city from the German horde.

While Francis wars elsewhere, as he began,

With cruel pride, so rules this ducal lord,

That soon the king discovers, to his cost,

Thereby, once more, a city gained is lost.

Canto XXXIII: 45-53: Merlin’s prophetic art: The Battle of Pavia

A second Francis, see, a Sforza, heir

To the founder’s rare virtues, and his name.

He, with the French expelled, we witness there

Regaining lost Milan which now he’ll claim.

France too returns, but under tighter rein,

Nor scourges Italy, as did that same,

For Mantua’s noble duke, Federico,

Bars their passage o’er the Ticino.

Though o’er his cheeks youth’s bloom doth scarce advance,

That duke seems worthy of eternal glory,

For tis not merely by the sword and lance,

But through diligence, and ingenuity,

He defends Pavia from the men of France,

Frustratings the Lion of Venice equally.

Here, are two marquises, Italy’s pride,

And the bane of we French, tis not denied,

Both of one blood, born in the one nest, there,

The first, Fernando (son of that Alfonso

Who, through the Moorish slave, caught in a snare,

Drenched with a crimson stream the ground below)

You see how, through his counsel, like a hare

From Italy he oft hounds the French foe,

The other, of benign looks and manner,

Alfonso, Sixth Lord of Pescara later.

He is the famous warrior wise and bold,

That I spoke of when we viewed Ischia,

Of whose mighty deeds wise Merlin foretold,

Speaking to King Faramond, earlier,

Saying his birth would be deferred, untold

Ages, until needed more than ever,

By Church, and Empire, and poor Italy,

To counter their most barbarous enemy.

He, following his cousin, Fernando,

Under Prospero Colonna’s command,

Makes the Swiss, at Bicocca, and more so

The French, pay dearly, for all they’ve planned.

Behold how France again must prove a foe:

Seeking to restore her losses, out of hand,

The king descends once more on Lombardy,

His other force on Naples fair city.

But she that makes us like the dust that flies

Before the wind, whirling that dust around,

Who raises it, awhile, towards the skies,

And then returns it swiftly to the ground,

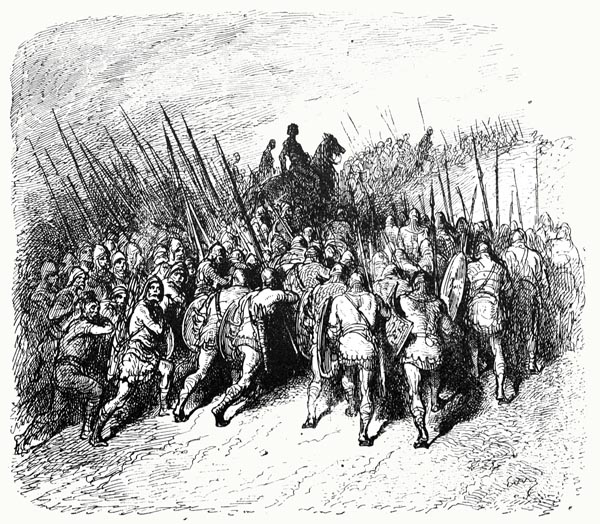

Has a hundred thousand men, to the eyes

Of Francis, Pavia’s mighty walls surround.

He marvels at what lies before his hand,

But marks not the weakness of his command.

Through the greed of a cunning minister,

And the goodness of a most trusting king,

The ranks are but thin that seek to muster,

When, by night, the call to arms forth doth ring,

For his camp the cunning Spaniards enter,

Guided by those two of Ischia’s making;

Avalo’s ardent blood drives that pair on,

That in search of heaven or hell are gone.

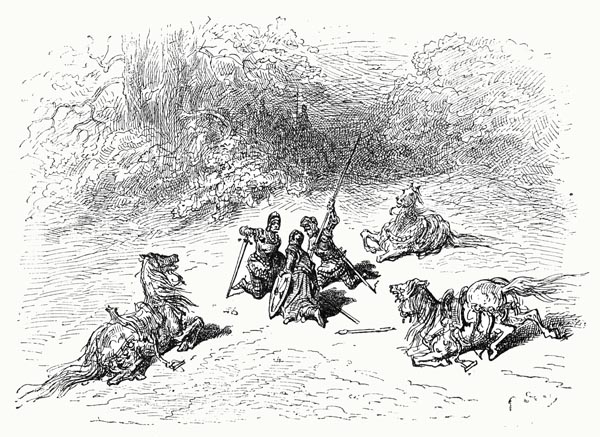

View the finest of the French nobility

Suddenly extinguished, on that field;

While a host of swords, and lances, you see,

That, nigh the monarch, these Spaniards wield.

Behold, his horse falls under him, while he

Neither owns himself conquered, nor will yield.

Though to him, alone now, the foemen run,

Abandoned there, to aid him he finds none.

The King of France, on foot, makes his defence,

Drenched in the enemy’s blood, head to toe,

But courage yields to force (and better sense),

He is taken, and to Spain must swiftly go;

While true praise, and glory, both immense,

On brave Fernando all men now bestow,

And on Alfonso, ever at his side,

For a king is captive, and his aims denied.

Canto XXXIII: 54-57: Merlin’s prophetic art: The Naval Battle of Capo d’Orso

Once force is routed on Pavia’s plain,

The other, Naples bound, quelled on the way,

As an oil-less lamp, a wax-less candle wane,

Till quenched is each illuminating ray.

Behold the king returns to France again

Leaving his son in Spanish hands; away

From fair Italy, where he wages war,

Others do likewise on his native shore.

Rome is grieving at the rape and murder,

Theft and arson, that everywhere we see,

And all is cursed by insult and anger,

The profane and the divine equally.

The League, as they advance, view with terror

This sore disaster and where they should be

Moving swiftly towards Rome, they retreat,

Abandoning him who holds Saint Peter’s seat.

Francis sends Lautrec with a fresh army,

Not to wage war anew in Lombardy,

But to save the Pope from the enemy,

And free the Church’s head and limbs entirely.

But Lautrec and his men move so slowly,

The Pope by then has gained his liberty,

And now has conquered Naples fair city,

With its tomb of the Siren, Parthenope.

And here the Spanish ships southwards steer,

To thwart the French blockade, as best they may;

Set afire, sunk, engulfed, they disappear,

Met by Andrea Doria mid-way.

Behold, how lightly Fortune now shall veer,

That seems to aid the French, for from that day

Their troops are slain by fever not the lance;

Of a thousand not one returns to France.’

Canto XXXIII: 58-64: Bradamante’s vision of Ruggiero

These and other things the walls portrayed,

Whose contents would be lengthy to relate,

In lovely, varied, colours that conveyed

Their meaning well, their import seeming great.

Twice, or thrice, they returned and honour paid

To their excellence, viewing those turns of fate.

And knew not how to leave the scenes foretold,

Reading the words beneath, writ there in gold.

When the lovely ladies, gazing with the rest,

Had viewed and conversed, sufficiently,

Their host, who sought to honour every guest,

Led them to their chambers, courteously.

Yet Bradamante was by thoughts oppressed,

Though the others were soon slumbering deeply;

Turning this way and that, of sleep bereft,

Leaning upon her right side and her left.

Near dawn, at last, she closed her weary eyes,

Only, in dream, to see her Ruggiero,

Who seemed to say: ‘Why such doubts realise?

Why grant substance to things that are not so?

For rivers will flow backwards, ere such lies

Possess truth, and I turn from you; and, know,

I’ll cease to love this heart of mine, still true,

And these eyes, ere I’ll cease to care for you.’

Then he seemed to suggest: ‘I am come here,

To be baptised, fulfil the pledge I made,

For by a wound not wrought by Love, I fear,

I have been long oppressed and, thus, delayed.’

With that, the vision chose to disappear,

While its vanishing broke her troubled rest.

The warrior-maid shed fresh tears of woe,

And then spoke to herself, in accents low:

‘What pleased me so was but an idle dream,

This that torments me is the truer sight;

The dream of joy is but a vanished gleam,

No dream my suffering, my sorry plight.

Why must my joyless senses rule supreme,

And wrest him, thus, from hearing and from sight?

What condition afflicts my poor eyes, still?

That they must close on good yet ope to ill?

Sweet sleep thus promised both repose and peace,

Yet bitter the dream wakening me to war.

Sweet sleep but brought what proves illusory,

Yet bitter my sight that doth the truth restore.

If falsehoods please, while truth brings misery,

Let me not see or hear such truth and more:

If sleep brings pleasure, and if sight brings pain,

Then let me sleep, never to wake again.

Happy the creatures that sleep half the year,

Nor open, for six months, their shuttered eyes!

For if such sleep like death must e’er appear,

The title ‘life’ scarce to my state applies;

So contrary my fate, my suffering here,

My heart, alive in sleep, in waking dies.

And, if such sleep is deathlike, ah, come Death,

Close up my eyes, and ease my parting breath.’

Canto XXXIII: 65-76: She jousts again with the three kings at their request

The sun had crimsoned the far horizon,

And all the clouds had vanished from the sky,

Thus, a fresh view of things met her vision,

With the promise of sweet times by and by,

When Bradamante rose, and made provision

For her journey, armed herself, gave a sigh,

Then thanked the tower’s courteous commander

For the kindness and honour he had shown her.

She found the ambassadress and her maid,

With the squires too, had issued from the keep,

And had joined the three kings, there arrayed,

That had been obliged in that place to sleep.

Those three monarchs her golden lance had laid

On the ground, for whom the lady might weep,

Since they’d spent the night in deep discontent,

Wind and rain proving most malevolent.

Add, then, their empty stomachs to their ire,

For both they and their good steeds yet remained,

Grinding their teeth, and trampling the mire,

But what increased their fury, now unfeigned,

Was that they knew the lady ne’er would tire

Of telling their fair queen how they’d sustained

Defeat at a warrior’s hands, this the first lance

That they’d encountered in the land of France.

Ready to gain revenge, or die, were they,

For the insult to himself each perceived,

If but Ullania might see her way

(Such was her name, if I’m not deceived)

To disregard the defeat they’d met that day,

And quell the ill opinion she’d conceived,

So, once more, they challenged Bradamante,

As she had crossed the drawbridge already,

Not dreaming that she was a maiden, though,

For she showed naught of that in her manner.

Bradamante refused, in haste to go,

But the three so begged her, and harassed her,

That it seemed shameful to deny them so;

Three thrusts she gave, and each descended

To the earth; and, thus, the warfare ended.

Without another glance, she turned her back,

And, in a trice, disappeared from the field,

While they who had launched the fresh attack,

Come to this land to gain the golden shield,

Who now both courage and fair speech did lack,

Rose slowly, their amazement unconcealed,

Seeming dumbfounded, in their great surprise,

Nor to Ullania dared raise their eyes.

Full many a time when they were on the road,

They’d boasted to her of their great prowess;

For there was ne’er a knight of France, they’d crowed,

Could match the least of them in skilfulness.

The lady, to dispel their pride, and goad

Them for their arrogance, and scant success,

Told them the knight, who’d laid them at her feet,

Was a maid; and rendered their shame complete.

‘What must you think of Orlando’s might,

Or Rinaldo’s, for which the pair are famed,

When you are all three overthrown in fight

Defeated by a maid, who goes unnamed?

If you would have the shield, I ask outright:

Shall you joust as well as you have claimed,

If this, against a maid, is all you do?

I think not, and perchance you think not too.

Let this suffice you all; there is no need

To show a clearer proof of your valour.

If there be one that seeks a reckless deed

And to gain experience through another,

Or add danger to his shame, and thereby bleed,

He’ll but deepen that shame and dishonour;

Unless he thinks it useful, or wins praise,

To meet such warriors, and end his days.’

As soon as Ullania had made plain

That a maid was the cause of their downfall,

And blacker than pitch dyed, to their great pain,

Their honour once so fair (beyond recall,

Twas lost, or so did more than one maintain

Where but the one sufficed) twas bitter gall.

They felt such sorrow, that they well-nigh turned

Their weapons on themselves, their anger burned,

The doffed their armour (in the moat it went

That ringed the Tower) stung by rage and fury,

Cast away e’en their swords, in discontent,

And left themselves devoid of arms, entirely,

And swore that, since their previous intent

Was thwarted by a maid, and they swiftly

Hurled to the ground, they would now appear

Unarmed, in every place, for twelve months clear,

And that they’d travel on foot, everywhere,

Up and down the hills, over every plain,

Nor, when the year had ended, would they bear

Chain-mail and plate, or mount a horse again,

Unless they had, in some warlike affair,

Acquired those same, as fortune might ordain.

Thus, in penance for their failings they went

On foot while others rode, with quiet lament.

Canto XXXIII: 77-78: She hears news of King Agramante’s flight from Paris

Bradamante lodged in a keep, that night,

Which lay upon the road from Paris; there,

She heard the news of Agramante’s flight,

And brave Rinaldo’s role in that affair,

For her brother was indeed a man of might.

The bed and board were fine but, full of care,

She ate little, and she slept even less,

Denied repose, by thoughts that caused distress.

Yet, for now, I shall say no more of her,

And return to Rinaldo and Gradasso,

For each bold knight had tethered his charger

Beside the solitary fount, as you know,

And I’ll speak of their duel a little further,

Though they fought not for land or power, so,

But that the best might Durindana wield,

And ride Baiardo o’er the battlefield.

Canto XXXIII: 79-83: We return to the duel between Rinaldo and Gradasso

Without a signal, or a trumpet sounding,

To announce their joust, without a master

To advise them on their moves when fighting,

Or spur them on to attack each other,

They drew their mighty swords, and commencing,

With one accord, lunged at one another.

The blows rained thick and fast, and their ire

Waxed, as from the first spark grows the fire.

I know no other blades of shining steel

As sound and solid, forged to so endure.

Three blows alone from them, could one but deal

Such strokes, surpassed all measure, I am sure;

So perfect was their temper, near ideal,

From many a trial they’d emerged secure;

And they might strike a thousand blows, say I,

Before a splinter from those blades would fly.

Here and there, Rinaldo danced, as he sought,

By skill, and effort, and dexterity,

To evade Durindana as they fought,

Knowing that weapon’s sheer lethality.

Gradasso’s heavier blows oft fell short,

Or cut the air, or landed but idly,

Or, if they struck home, fell upon some spot

Which resounded, while little harm was got.

Rinaldo fought far more effectively:

He numbed Gradasso’s arm with a blow,

And often struck his helm, or flank sharply,

Or his breastplate, as to it they did go,

Yet found the other’s armour, endlessly,

Impenetrable, for all his brave show;

Though if his every effort seemed to fail,

Twas no wonder, it was enchanted mail.

Without seeking rest, the two had fought

Some little while, on their duel so intent

That their eyes scarce another thing had sought

Save that on which their labour was spent,

When suddenly an equal noise they caught,

And upon other strife their sight was bent;

Such was the sound they both turned away

And saw Baiardo troubled, and at bay.

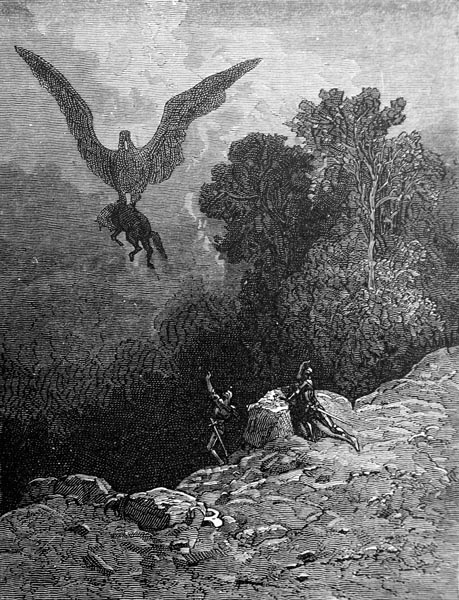

Canto XXXIII: 84-88: A flying creature appears and Baiardo flees

The horse was in conflict with a monster,

Or rather a monstrous bird, whose great beak

Was three yards long, the bird in bulk bigger

Than the steed; batlike, if more facts you’d seek,

Except with feathers, deepest black, all over;

Piercing talons, it possessed; it gave a shriek,

And with blazing eyes, and a vicious look,

Two wide wings, like a ship’s mainsails, it shook.

A bird perchance, and yet I know not where

Or when, such a bird did ever feature;

I’ve seen no pictures, nor read anywhere

Except in Turpin’s work, of such a creature.

Which moves me to believe the monster there

A devil out of hell, vile in nature,

That Malagigi conjured, in such guise

As to shock them, and thwart the fight likewise.

This Rinaldo too believed, and thereafter

Many a scornful word passed twixt the two;

Malagigi would not confess, rather

He swore by the fires that light the sun anew,

That he had naught to do with the matter,

To claim so was unjust, nor was it true.

Whether bird or demon the thing once more

Swooped on Baiardo, wielding beak and claw.

The mighty steed broke free, suddenly,

And, with disdain and ire, it kicked and bit

At the creature, which retreated swiftly

Into the sky, where it might not be hit,

And wheeled round and round the charger, calmly,

Plunging down, then gripping and beating it.

Baiardo, unequipped for such a fight,

Suffering badly, quickly took to flight.

The courser sped towards the wood nearby,

Searching for the densest thicket there.

The feathered monster followed with its eye

While, from above, it marked the path, with care,

But the horse so hid itself none could spy

Its whereabouts, then found a stony lair.

Once the creature lost all trace of its prey,

In search of other flesh, it sailed away.

Canto XXXIII: 89-92: Rinaldo fails to find the steed

Rinaldo and Gradasso when they saw

The reason for their quarrel departing,

Agreed to suspend the fight once more

Till they’d rescued the steed, though agreeing

That whoever found it first must ensure

He returned to the fount it was fleeing,

And be present by that source to defend

His honour, till their duel reached an end.

In pursuit, they left the fount far behind,

Following fresh hoofprints on the ground,

Though Baiardo ran faster to their mind,

And looked to vanish soon, as they found.

Gradasso now to mount his steed designed,

Alfano, that was yet both safe and sound,

And left Rinaldo stranded midst the trees,

Never filled with less joy, or more unease.

A few steps more and he had lost all trace

Of Baiardo, who his strange course had run,

The courser making for some thorny place

Midst trees, streams, and rocks, so as to shun

Those cruel claws, that struck at his bare face,

And now hiding from the light of the sun.

Rinaldo whose labours proved all in vain,

Returned, and lingered by the fount again,

Trusting Gradasso would, in time, repair

To the place, as agreed twixt them before;

But, having waited, quit the whole affair,

And returned to camp, his heart (and feet) full sore.

We’ll pursue Gradasso; see him there,

Happier than Rinaldo, to be sure,

For not through skill, but destiny, say I,

He heard Baiardo neigh aloud, nearby.

Canto XXXIII: 93-95: Gradasso succeeds, and sails for home

He found him hiding in a gloomy cave,

So oppressed by fear of the creature

He dared not emerge, no longer brave

And bound to obey Gradasso’s pleasure.

The king remembered that the first to save

The steed was pledged to return the charger

To the fount, and yet he scorned so to do,

Seeing fit his silent thoughts to pursue:

‘Whoe’er covets him for conflict and war,

To possess him in peace is my desire.

From the far side of the earth, I sailed, before,

To seek him, and to that alone aspire.

Having my Baiardo now, you may be sure,

Any that seeks him risks more than my ire.

If Rinaldo wants him, let him grasp his lance,

And search all India, as I have France.

Sericana he’ll find no less secure

Than his France has, twice, appeared to me!’

And, so saying, he spurred his steed once more,

Rode to Arles, and chartering a boat, he,

(With Durindana) departed that fair shore,

His Baiardo, safe aboard the galley.

But of this hereafter; for Gradasso

I leave behind, and France, and Rinaldo.

Canto XXXIII: 96-102: We turn to Astolfo who reaches Ethiopia

I turn to bold Astolfo, still in flight,

Riding the hippogriff like a palfrey,

Saddled and bridled, thus, to bear the knight,

On a course that the eagle spurns entirely,

Over all of Gaul, gleaming in the light,

From Rhine to Pyrenees, from sea to sea,

Rising to those mountains, from the plain,

That separate the whole of France from Spain.

He passed Navarre, flew over Aragon,

(Leaving those who saw the sight to wonder)

Tarragona southwards, Biscay upon

His right, and reached Castile and, over

To the west, saw Galicia, then Lisbon,

Reaching thence Seville, beyond Cordoba;

Outspread beneath him, all of Spain he saw,

Each of her fair cities, shore to shore.

Cadiz, he viewed, and those bounds the sailor

Marks, once set there by mighty Hercules,

(Intending, thus, to traverse Africa,

To the ends of Egypt, from those western seas).

The Balearic Isles he now flew over,

And saw Ibiza, there, beneath his knees,

Then tugged the reins, and turned for Asilah,

O’er the sea from Spain, yet seeming closer.

Moroccan Fez he sees, Oran the fair,

Algiers, Béjeïa, Annaba (all those

Great cities that the crown of laurel bear,

Yet, wrought in gleaming gold, its leaves disclose),

To Bizerte headed, gliding through the air,

O’er Tunis, Gabes, Djerba’s isle, he goes,

Tripoli, Benghazi, Tolmeita,

Towards the Nile’s mouths opening on Asia.

Twixt Atlas’ wooded ridges and the shore,

He viewed thus the landscape all around,

Turned his back on Carena’s peaks, to soar,

Then skim o’er Cyrenaica, near the ground,

And, above the desert, south-eastwards bore,

With Battus’ tomb behind, yet ne’er a mound

Where Zeus-Ammon’s shrine once stood, at Siwa,

Till he reached Albaiada, and Nubia.

Then to another Tlemcen he came,

Where upon Muhammad’s tenets they smile,

And a second Ethiopia in name,

Which faces the other, beyond the Nile;

Twixt Coallee and Dobada he took aim;

(Bound for the royal city, in fair style)

Here the Muslims, there the Christians stand,

And each side guards the borders of their land.

In Ethiopia, their emperor,

Was Senapo, the cross was his sceptre,

Possessed of cities, gold, and men, and more,

As far as the Red Sea’s southern water;

He held a faith much like ours, wherefore

He may have won salvation thereafter.

Tis there, lest I err and prove a liar,

That their baptismal rite makes use of fire.

Canto XXXIII: 103-112: Senapo, Emperor of Ethiopia (called Prester John)

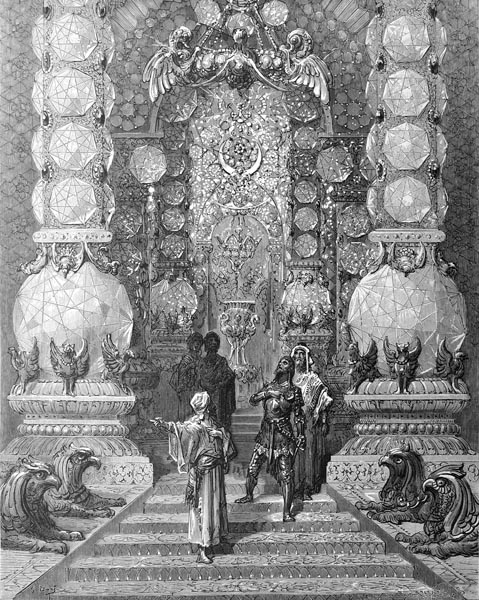

Astolfo set down in the spacious court

Before the palace, to visit the king.

Less strong than splendid was the royal fort,

From which this emperor ruled everything;

The fittings of the bridges, gates, in short,

Every bolt, and hinge, and chain, and ring,

Which with us would be iron, I am told

Was in this palace wrought of solid gold,

And the metal which was so abundant there

Was of the very finest purity.

Columns, of translucent crystal, did bear,

Here and there, a hanging balcony,

While, beneath these, ran a frieze, an affair

In red, white, yellow, azure, verdigris;

Divided, with clear spacing, by many

A topaz, sapphire, emerald and ruby.

In the walls, roofs, and pavements, embedded,

Gleamed many a pearl, many a rich gem.

There the balm thrives, more fully tis said

Than do the plants found near Jerusalem.

The musk we utilise from there was sped,

And amber too has been obtained from them;

Many a thing, in sum, comes from that country

Which we, in our domains, value greatly.

Twas said the Sultan that in Egypt reigned,

Paid tribute to this Emperor, Senapo,

For of the Nile flood, twas maintained,

He controlled both the timing and the flow,

Such that Cairo and its districts obtained

Their water, and so grew their crops, below.

Senapo is the name all folk gave, yon,

To one we call the Priest, or Prester John.

Of all who ruled in Ethiopia

He was the richest and most powerful;

Yet, with all his riches and his power,

He yet was blind, and therefore pitiful.

And greater trouble did his life devour,

More miserable still, and more harmful,

For however rich seemed that emperor

He was afflicted with ceaseless hunger.

When the wretched man sought to drink or eat,

Tormented by that great and pressing need,

An infernal vengeful brood flew to greet

His efforts, monstrous Harpies (in their greed,

With beaks and talon, battening on the meat,

Overturning the jars) that stayed to feed.

And what their stomachs failed to contain

They’d leave soiled and foul, then flee again.

Now he, because he was so green in years,

Yet had been raised to such supreme honour,

And because he was endowed, it appears

More than any, with courage and vigour,

Grew proud as Lucifer, amidst his peers,

And thought to wage war upon his Maker,

And proceeded to attack the very mount

Where Egypt’s mighty river has its fount.

He had heard that upon this Alpine peak,

That thrust above the clouds, and touched the skies,

The realm of Eve and Adam one might seek

That we name the terrestrial Paradise.

With a mighty army, he of whom I speak,

Elephants and camels massed before his eyes,

Went to find if any lived where that mount soars,

And render them obedient to his laws.

God reproached him for his audacity,

And sent an angel to destroy his sight,

That slew a hundred thousand in his army,

And condemned him to perpetual night.

And then, to his board, flew many a Harpy,

Those horrendous monsters, a hellish blight,

That contaminated all, with their stink,

And left him nothing fit to eat or drink.

So, it was prophesied, things would continue

(To the emperor’s uttermost despair)

The Harpies would that same foul course pursue

And would only forego the royal fare

When a knight on a winged horse hove in view,

And descended upon them from the air;

Which, indeed, seemed a most unlikely thing,

And brought little hope to the wretched king.

Canto XXXIII: 113-116: He begs Astolfo to alleviate his plight

So it was with amazement that they saw

The English knight now circling in the sky,

Then, in haste, the news to the emperor bore,

Of what wheeled above the walls and towers, on high.

Recalling the prophecy wrought before,

Neglecting the staff, he was supported by,

The king sped joyfully this knight to greet,

That seemed destined to land, there, at his feet.

Sweeping widely, Astolfo now descended,

And touched down in the courtyard far below.

The emperor knelt, his arms extended,

(His attendants had helped him, thus, to show

Humility). ‘If I have offended,

Yet may still mercy find,’ he cried ‘you know,

Angel of God, sin is e’er Man’s intent,

As tis yours to pardon those that shall repent.

Aware of my fault, I dare not conceive,

Nor dare to ask, that you’ll restore my sight,

Though you possess the power, I believe,

Being dear to God, and blessed by His might.

Let it suffice that I, no more, perceive

The light of day, yet ease my other plight,

Drive my hunger, and those vile Harpies hence,

Let them not foul all here; be my defence.

And a marble temple I will promise you,

Built on high, its roofs and walls of gold,

Beside this palace, glorious to the view,

Decked without, and within, with gems untold,

And your name it will bear, as is your due,

And through sculpture will the miracle be told.’

So spoke the sightless emperor and, again,

He sought to kiss the duke’s feet, but in vain.

Canto XXXIII: 117-125: Astolfo rids the king of the Harpies

The knight replied: ‘No angel of the Lord

Am I, no new Messiah, from the sky;

A mortal sinner, nor of grace assured,

Unworthy to bestow such things, am I.

Yet all my aid to you I may afford,

To drive the creatures hence, or see them die.

If I do so, then praise the Lord alone,

In that a means to help you, thus, is shown.

Make your vows to God, to Him they are due,

To Him your churches, and your altars, rear.’

Discoursing so, they took their way those two

Towards the palace, amidst many a peer.

The king commanded his cooks anew

To prepare a feast, that swiftly did appear,

Hoping the knight might quell that vile band

That sought to snatch the food from out his hand.

Within a nearby chamber, Senapo

Commanded that the table should be laid,

And, seated alone, he and Astolfo

Were served the solemn dinner, there conveyed.

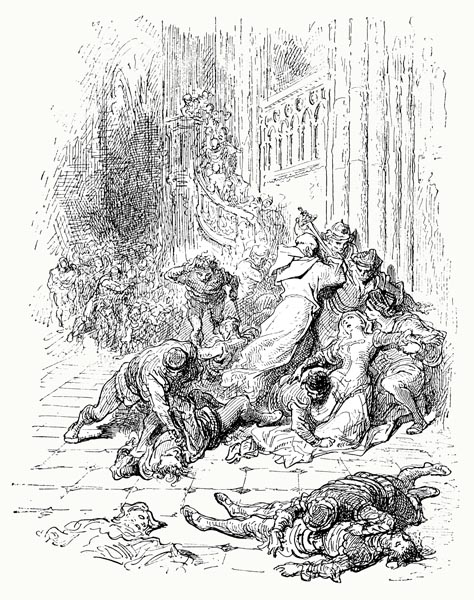

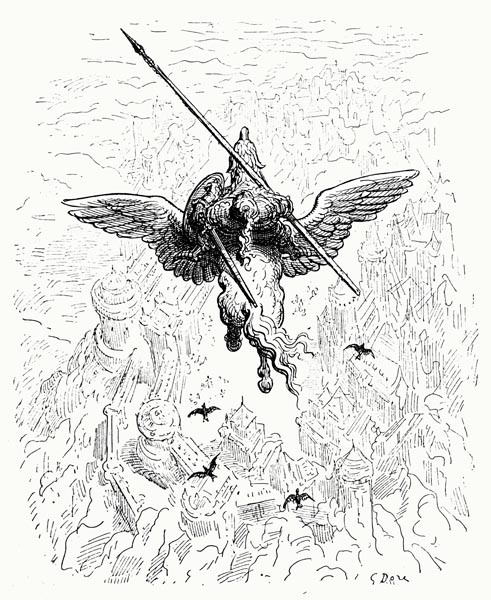

Lo, a whirring sound above was heard, and lo,

Monstrous creatures beat the air, on their raid;

Down from above, the thieving Harpies came,

Drawn by the scent of food, to snatch that same.

Seven in number were that horrid crew,

With the faces of women, pale and wan,

Dry-lipped they were, emaciated too,

More dreadful than death, as they began

To flap their great misshapen wings, anew,

And arch their crooked claws; the evil clan

Had large and fetid bellies, and long tails,

Like coiling serpents, that left slimy trails.

They heard them in the air, as they plunged,

And swooped together on the plates of food,

Overturned all the jugs and jars, and lunged

At the scraps, while there rained a noisome flood

Of foul ordure, not readily expunged,

Upon the board; wrath fired Astolfo’s blood,

And, unable to withstand the smell, the knight,

Drew his sword, and whirled it with all his might.

He struck one on the neck, then another

On the rump, and the breast, and the wing,

But, as if he’d hit a bag of dough, ever

The strokes failed, effecting not a thing,

While they left not a plate or cup, never

Turning for a moment from their feeding,

Till they had ravaged what was thereby doomed

To be fouled and soiled, or otherwise consumed.

The king had pinned his hopes on the knight,

Trusting he’d send the creatures on their way,

But now his hopes had vanished (like the light)

He moaned, and groaned, and sighed, in his dismay.

But then the duke remembered that he might

Employ the magic horn, that helped alway

In times of war; and thought it just the thing

To ensure that those evil birds took wing.

First, he told the king, and all the court,

To stop their ears with wax so the sound

Would not send them all fleeing, for, in short,

It maddened all who tried to stand there ground,

Then he seized the bridle and, ere he fought,

Mounted on the hippogriff and wheeled around

With the horn in his hand, and had a board,

With another set of cups and plates, restored.

This was sited in an open gallery,

Where the Harpies soon returned as of old,

While Astolfo blew the horn, full loudly,

As soon as he those creatures did behold,

And since their ears performed perfectly,

The noise soon penetrated every fold.

They fled in fear, while they showed not a care

For the food e’er again, nor aught else there.

Canto XXXIII: 126-128: And sends them fleeing to Hades

At once, in hot pursuit, Astolfo spurred,

And issued forth, flying from the court,

He left the emperor, without a word,

As o’er the distant sky those birds he sought,

He blew the horn, and all the people heard,

(Unless their very ears were stopped, in short)

While the vile Harpies fled to heights forlorn,

Those highest peaks where the Nile is born.

Almost to the roots of that great range

A cavern pierces, plunging underground;

And they do say twould be more than strange

If it leads not to Hades: from the sound,

The Harpies fled, seeking to exchange

The echoing air for silence, this they found,

Descending, swiftly to Cocytus’ shore,

Where the horn’s fearful cry was heard no more.

Outside that deep, and dark, infernal hole,

Where a way opes to those who flee the light,

Astolfo ceased to blow, achieved his goal,

And let his courser furl its wings in flight.

Yet ere I lead him further, that brave soul,

Or seek to scorn my customary rite:

This canto’s long enough; I think it best,

To end it here, and then go seek some rest.

The End of Canto XXXIII of ‘Orlando Furioso’