Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXX: Mandricardo's Fate

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXX: 1-3: Ariosto’s apology to the ladies

- Canto XXX: 4-9: Orlando goes on the rampage

- Canto XXX: 10-15: And nigh on drowns in the sea

- Canto XXX: 16-22: We return to the warriors and their quarrels

- Canto XXX: 23-27: The contest meets with disapproval

- Canto XXX: 28-36: Doralice seeks to persuade Mandricardo not to fight

- Canto XXX: 37-42: Mandricardo replies

- Canto XXX: 43-46: Mandricardo and Ruggiero prepare to joust

- Canto XXX: 47-52: They fight and Mandricardo strikes a mighty blow

- Canto XXX: 53-57: Ruggiero recovers and wounds Mandricardo

- Canto XXX: 58-64: And then finally slays him

- Canto XXX: 65-70: Though receiving a further wound himself

- Canto XXX: 71-73: Regarding Doralice’s fickle nature

- Canto XXX: 74-75: The spoils are distributed

- Canto XXX: 76-80: We return to Bradamante

- Canto XXX: 81-85: Bradamante’s lament

- Canto XXX: 86-89: Ricciardetto gives her further news

- Canto XXX: 90-95: Rinaldo arrives, then returns to Paris with his brothers

Canto XXX: 1-3: Ariosto’s apology to the ladies

When Reason allows rashness and anger

To defeat her, and offers no defence,

And blind fury so directs, moreover,

Hand and tongue, that to friends we give offence,

Though we may sigh aloud, thereafter,

We can scarce amend it by penitence,

Still, I regret what I said (to my woe)

At the end of the previous canto.

I’m like one who is ill and suffering,

Who though patient for many a long day,

Can no longer contain his loud moaning,

And to fury and blasphemy gives way.

Yet, the pain and the sickness receding

That moved his tongue to utter his dismay,

He repents of annoying everyone,

And yet cannot undo what he has done.

Still, I hope, ladies, of your courtesy,

I’ll yet obtain the pardon that I seek,

And you’ll excuse that, in bitter frenzy,

I, there, expressed so damning a critique.

Lay the blame upon my fair enemy,

She, who renders my state but sad and bleak,

And makes me utter what none should approve:

God knows how she wrongs me; she, how I love.

Canto XXX: 4-9: Orlando goes on the rampage

I was no less beside myself, tis plain,

Than Orlando, and as worthy of pardon;

He who’d scoured the better part of Spain,

Wandering o’er shore, and plain, and mountain,

While still dragging that dead mare by the rein,

To no good purpose, a useless burden;

But when he came to where a river met the sea,

He abandoned the corpse, indifferently.

And, since the Count could swim like an otter,

He leapt in, and landed on the further side.

Behold, a shepherd brought his horse to water,

And to that bank of the stream turned aside.

He scorned not the Count, although, as ever,

He was naked and alone. Orlando cried,

Like the madman he was: ‘I will barter,

My mare for your steed, she’s o’er the river.

If you’d have me show you her, I’ll do so.

She fell down dead, upon the other shore.

You’ll be able to cure her of it though,

For she’s scarce another defect, I’m sure.

Grant me yours, with something else also,

To make the thing fair, for the mare’s worth more.’

The shepherd laughed, not one word did afford,

But quit the fool, and rode towards the ford.

‘Hey there, do you hear? I want your horse!’

Cried Orlando, who towards him did go,

While the shepherd stayed him in his course

With his sound knotted staff, though the blow

Only fired the Count’s wrath, who, with force,

A solid thump of his fist did bestow

Upon the shepherd’s unprotected head,

Split his skull so, and left the fellow dead.

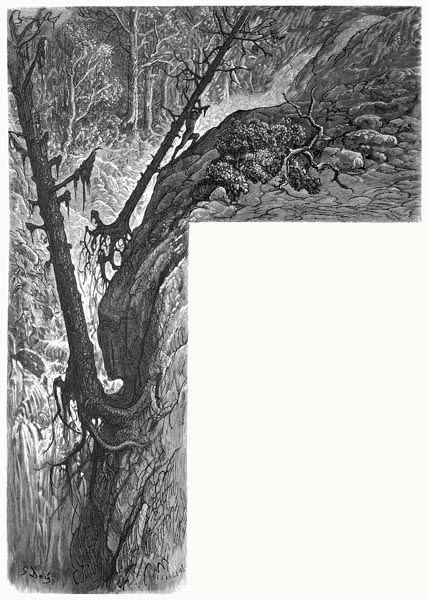

Then, leaping on the horse, he went his way,

Wandering madly everywhere, pillaging,

While the horse, that saw not a sight of hay,

Was soon done for, half-famished and limping.

Yet Orlando went on foot not a day,

Nor e’er lacked for transport, acquiring

Some other. For whene’er he felt the need,

He’d slay a rider, and purloin his steed.

He came at last to Malaga, and wrought

Greater harm there than any place before,

For besides the mighty havoc that he brought,

He left the folk unable to restore

Their wealth in less than a full year; he fought

Wildly, killed many, and furthermore,

Orlando pulled so many houses down,

He destroyed nigh on a third of the town.

Canto XXX: 10-15: And nigh on drowns in the sea

Leaving there, he came to Algeciras,

On the shore of the Bay of Gibraltar,

(Or Jabal Tariq, for either will pass

As the name for that rock o’er the water)

Here he saw a boat departing, that alas,

He felt he wished to board; bound for pleasure

Were its occupants; to the morning breeze,

They’d spread their sail, and were taking their ease.

‘Put back, for me!’ the mad Orlando cried,

Yet shouted to those voyagers in vain,

For sadly on their ears his clamour died,

Nor sought they such a cargo to obtain.

As swiftly as they could, the oars they plied;

Like a swallow, the boat sped o’er the main,

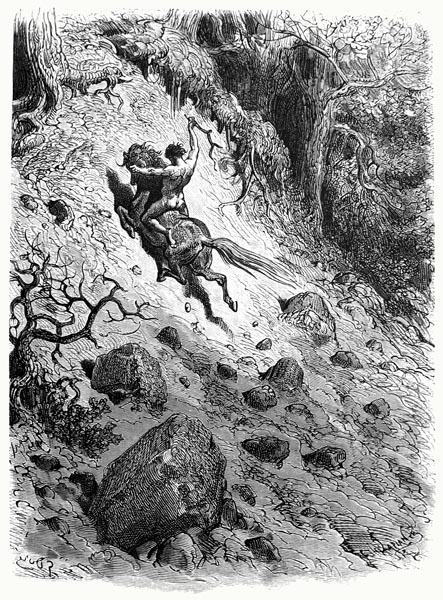

While Orlando struck his steed, violently,

And, flailing hard, drove it on, into the sea.

Lacking strength to counter wave or rider,

Urged on by mighty blows, the horse plunged deep,

Bathed first his knees, belly, then the crupper,

And scarce his head above the waves could keep.

Let him not hope to turn, or tire and founder,

While the Count seeks towards that boat to leap.

Wretched creature! Forced to drown, gloriously,

Or plough on, to Africa, o’er the sea.

For neither prow nor stern were now in sight,

Since the vessel was far distant from the shore,

And the mounting tide was of such a height

The boat was hidden; waves were all he saw.

Still, he drove the creature on with all his might,

As if he’d gallop o’er the sea’s deep floor.

The horse, lungs full of water, I’ll be bound,

At last, gave up the effort, and was drowned.

He sank, and would have dragged down the rider,

If Orlando had not turned himself about,

Worked his legs, and drawn his palms together,

And then swum, bare shoulders in and out,

As from his face, he blew the briny water.

The waves had calmed, the breeze quiet no doubt,

For fairer weather he required, the tide

Else would have swamped the Count, and he’d have died.

But Fortune, that ever cares for the mad,

Cast him from the waves on Ceuta’s shore,

Two bow-shots from the wall, and still unclad,

For scarcely a stitch of clothing he bore.

Along the coast he ran, and hence did add

Many a day’s wild wanderings to his score,

Till he came to a place, along the strand,

Where a host of dark-skinned folk clothed the sand.

Canto XXX: 16-22: We return to the warriors and their quarrels

Let us leave the Count to wander on his way,

The time will come to speak of him again.

While of fair Angelica, of Cathay,

Who’d escaped from the madman, as is plain,

And was bent for her land, without delay,

Seeking passage, and fair weather, o’er the main,

And Medoro, whom, once there, she made king,

Perhaps some finer voice than mine may sing.

For, upon other matters, I’m intent,

And Orlando I’ll not, as yet, pursue,

But rather I’ll direct my argument

To Mandricardo (free now to renew

His ties with Doralice) while content

That Europe has none lovelier in view,

Since fair Angelica has left its shores,

And chaste Isabella to heaven soars.

Mandricardo, proud of the judgement

That the lady had given in his favour,

Was not wholly satisfied; discontent

Pricked him, twas a question of honour;

Ruggiero’s shield a cause for dissent,

That silver eagle he displayed, as ever,

And then Gradasso’s wilful claim,

To that sword Durindana, known to fame.

Agramante had sought to untangle

This knot, with Marsilius, in vain.

Seeking, while pursuing every angle,

To end their quarrels, and the peace maintain,

He’d failed to resolve the endless wrangle

Over Hector’s shield, between the twain;

Nor indeed would Gradasso yield the sword,

While this and other conflicts were abroad.

Ruggiero refused to meet some other

With his shield, nor did Gradasso wish

To meet any, ere he met the Tartar

And did battle for the sword. ‘Chance in this,’

Cried the king, ‘shall now decide the matter,

And to these arguments put a finish,

Let us see what Fortune shall propose,

And let her of the question now dispose.

For, if you would do what would please me,

And I be obliged to you, evermore,

Then cast lots, as to the priority,

And agree who’ll fight the Tartar, on this score.

But he who does shall end this for all three,

And the result none of you may ignore.

If the one of you wins, he wins for two,

And if he loses his comrade loses too.

I think twixt Ruggiero and Gradasso

There is little to choose, in such a fight,

And whichever man to this duel shall go

He’ll reveal himself as a perfect knight.

Yet we’ll let Divine Providence now show

Who is wrong in the matter; who is right.

And on the loser no great blame shall fall,

For to Fortune’s will we’ll impute it all.’

Canto XXX: 23-27: The contest meets with disapproval

Ruggiero and Gradasso said naught

While Agramante spoke, but then agreed

That whoever was preferred, and then fought,

Would champion them both by that deed,

Thus, two lots, of the same form, were wrought,

And their names were inscribed, as decreed,

And these were placed inside a sealed urn,

Thrice shaken, and given many a turn.

A servant lad then dipped his hand within,

And drew a lot forth, and Ruggiero’s

Was the one that did the preference win,

While the one left behind was Gradasso’s.

I know not what the sorrow and chagrin

The latter felt, or the joy that arose

In the former, but to the pact they kept.

Fortune’s decree each agreed to accept.

Gradasso now gave every thought and care

To preparing Ruggiero for the fight,

That the latter might prove the winner there,

And gave of his experience outright,

Regarding all the use in that affair

Of sword and shield, and how a skilful knight

Might avoid empty blows, and so strike true,

And all the moves, one by one, did review.

The rest of the day, that yet remained

Once the lots were drawn, the warriors passed

In sending (for the custom they maintained)

Mementos to the friends they’d amassed,

While folk greedy for the fight had attained

The lists at once and, better first than last,

Not content to delay till it was light,

Were preparing to camp there for the night.

That mindless crowd anxiously attended

On the warriors’ arrival, till the morn,

Fools who neither saw nor comprehended

What was before their eyes, so were they born.

But Sobrino, and Marsilius the intended

Battle, with like-minded folk, viewed with scorn;

Both the contest, and their king, Agramante,

Who’d conceded so much to either party.

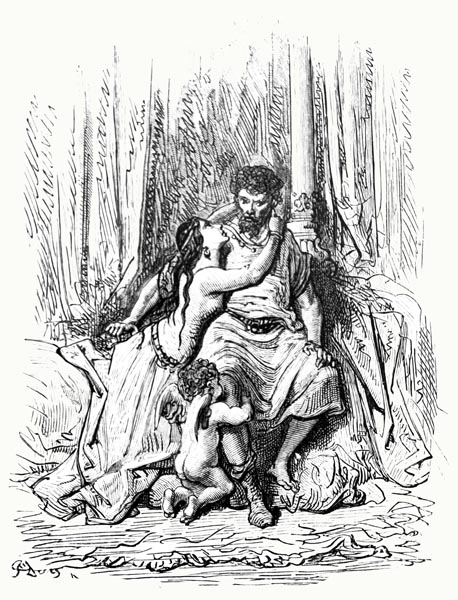

Canto XXX: 28-36: Doralice seeks to persuade Mandricardo not to fight

They continued to emphasise, indeed,

The harm that the Saracens would know,

If Fortune, in that fight, the death decreed

Of Ruggiero or Mandricardo;

Of their presence there was far greater need,

As against Charlemagne they did go,

Than of ten thousand others, to their mind,

Midst whom a champion was hard to find.

King Agramante knew that this was true,

But what he’d promised he could not deny.

Yet he asked now a favour of those two,

To yield the right he’d conferred thereby.

And, besides, what they sought to pursue

Was not worth martial combat, to his eye,

And, if this new request they’d not obey,

At least to countenance a short delay.

And if they would both defer their quarrel

For five months or six, they might chase

Charlemagne from his realm, take his mantle,

Crown, and sceptre, and he rule in his place.

Yet though neither man wished to trouble

Their king and disobey, they sought his grace,

For it seemed, to them both, a thing of shame

To be the first to concede and mar their fame.

But more fervent than the king’s (who in vain

Sought to change the mind of Mandricardo)

Were the pleas, and expressions of true pain,

That the daughter of King Stordilano,

Fair Doralice, uttered; she, again,

Begged him to do as all desired, her woe

Being great, that through him she must be

Subjected, thus, to deep anxiety.

‘For, alas, what remedy can I find

(She bemoaned) to allay my constant fear,

If ever some new passion fills your mind,

Such that in armour you must e’er appear?

What joy have I, ever to woe resigned,

In seeing the one quarrel ended here,

If you through love of me must discover

A reason to commence yet another?

Woe is me! Twas in vain that, so proudly,

I saw a worthy king and valiant knight

Put himself at risk for me, and fiercely

Fight as if his life’s worth were but slight,

When, thus, he but chances himself hourly

For so trivial a cause, with death in sight.

It is your inborn fury drives you now,

More than your love for me, I’ll avow.

But if tis true that it is love you show,

And that urges you to do me honour,

By that, and by the depths of my sorrow,

Which brings pain to my soul and heart, ever,

Cease to fret if on his shield Ruggiero

Now bears the eagle blazoned in silver.

Why should it matter so to you, that he

Bears that shield and emblem? Tis naught to me!

But small reward, though a world of pain,

Shall come of this brave quarrel you pursue,

While, if from Ruggiero you regain

The shield, tis slight benefit to you.

But if Fortune turns her back, then tis plain

(Since she it seems decides between the two)

You’ll cause such harm, as to think upon

Pains my heart, e’en before the fight is done.

If life be not a thing that you hold dear,

And a bird, painted on a shield, weighs more,

Then value life for my sake, since tis clear

One shall not die without the other, nor

Do thoughts of death beside you cause me fear;

I’m bound to follow you, as heretofore.

And yet I would not die a malcontent,

As I shall die, if thus your life is spent.’

Canto XXX: 37-42: Mandricardo replies

With such words and the like, which the lady

Accompanied with many a plaintive sigh,

She ne’er ceased to pray him, sincerely,

To seek peace, and let the quarrel go by,

While he, all that night, sucked in the dewy

Sweetness of her bright tears that fell thereby,

And the loving complaint from lips more red

Than a crimson rose, as, tenderly, he said:

‘Ah, come, love of my life, for Heaven’s sake,

Cease to weep, over so slight a matter,

For if Charlemagne himself were to make

War upon me alone, and on no other,

And our king too, did such action take,

You’d have no cause to fear it; however,

It shows what little faith you have in me,

Fearing, thus, Ruggiero’s enmity.

And then you should recall how I, alone,

Without my good scimitar in my hand,

Only a broken lance, yet held my own,

And scattered and dispersed a warlike band.

Gradasso, though he hates to have it known,

Admits, to those who make of him demand,

He was my prisoner, in far Syria;

And Ruggiero’s power is no greater.

Nor will Gradasso, likewise, e’er deny

Nor Isolier, nor Sacripante,

Circassia’s great king, the fact, say I,

Nay nor Grifone nor Aquilante,

Nor hundreds more, gathered from far and nigh,

That at the fearful pass I freed many,

Treating Muslims and Christians alike;

And, in like cause, I will forever strike.

Even now, warriors marvel at the deed,

And the wondrous things I did that day,

Greater than if the Moorish host indeed,

United with the Franks, I’d held at bay.

To Ruggiero then, should I give heed,

When in battle I shall the blade display

That once was Hector’s, fierce Durindana,

And fight protected by Hector’s armour?

Why sought I not to win you from the foe,

That you might have seen me charge, and defend,

With all my skill and valour there on show?

Then you’d foresee Ruggiero’s certain end.

Dry your tears, for God’s sake, speak not so;

Let no ill omen evil thus portend;

Tis for honour alone, I take the field,

And not the eagle blazoned on his shield.’

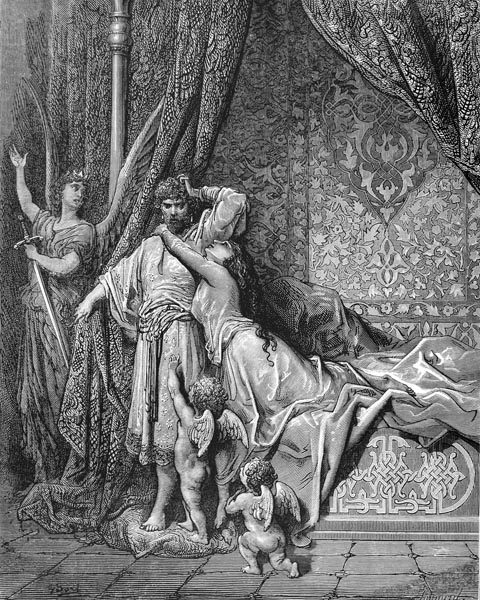

Canto XXX: 43-46: Mandricardo and Ruggiero prepare to joust

So, he spoke; yet many a good reason

To desist she offered, with saddened face,

Enough not just to change his opinion,

But to move a solid pillar from its place.

Behold, her knight was as good as beaten,

Though he was in armour, and she in lace;

She induced him to say that, if the king

Asked again, he would please her in this thing.

And he would have done so, but Aurora,

Accompanying the sun, as was her way,

Revealed Ruggiero, there, beneath her,

That his right to the eagle would display,

And would cut the quarrel short moreover,

By deeds, lest more words brought more delay.

And so, before the lists, that pleasant morn,

He appeared, in armour, and blew his horn.

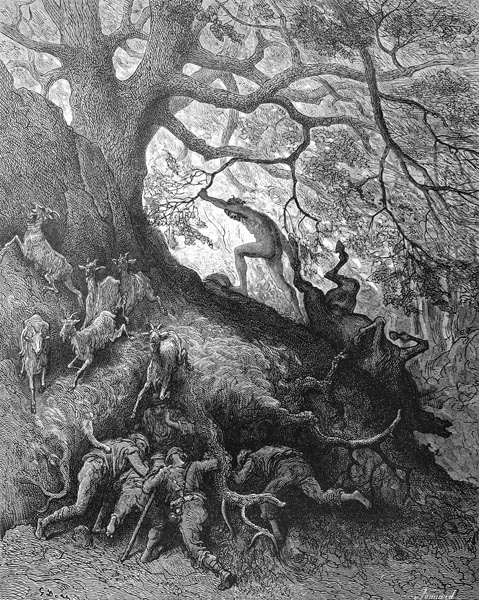

When proud Mandricardo heard that sound,

Whose loud cry now summoned him to the fight,

Every excuse he, as swiftly, found

To close his ears, and leave his bed outright;

And with so angry a face gazed around,

Doralice dared not speak, in her fright,

Of truce or peace, or of some new accord;

Of more conflict she was sadly assured.

He armed himself at once, while fretting

At his squires, all less prompt than he desired,

And then he mounted on his horse, being

That which was Orlando’s, that he’d acquired.

Then, to the place appointed for jousting,

He rode, to end the quarrel he’d inspired.

And at once the king and his court appeared;

Nor delayed, as Ruggiero had feared.

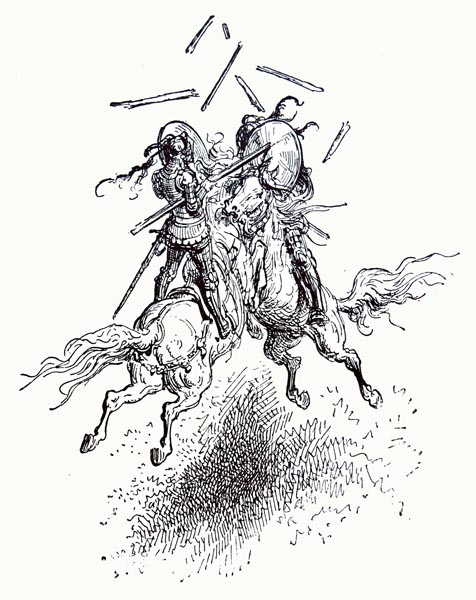

Canto XXX: 47-52: They fight and Mandricardo strikes a mighty blow

Their helms were set upon their head, and laced,

And each warrior was handed his lance,

Then the trumpet’s sound the hearers graced,

While a thousand cheeks paled at their advance.

Upon its rest each levelled spear was placed,

They spurred their coursers on (to death perchance),

And met together with so fierce a blow

The skies nigh fell, the Earth nigh split below.

On both sides the eagle emblem showed,

That Jove himself in air did once maintain,

That oft, in Thessaly, the currents rode,

Though with far darker feathers, o’er the plain.

How bold and strong they were the heavy load

Of wooden lance revealed, each did sustain,

That worse than that encounter had withstood,

As towers gainst the wind, or cliffs the flood.

The flying splinters soared towards the sky,

As Bishop Turpin writes, and is no liar,

For two or three returned thence, by and by,

That had ascended to the sphere of fire,

The warriors brandished their swords on high,

Displaying little fear, but great desire

For a fresh encounter, and so they met,

Their aim upon each other’s visor set.

The visor twas each struck, at that first blow,

For neither man sought to unhorse a knight

By thrusting at the valiant steed below,

Since their steeds were not to blame for the fight.

Who thinks this was a pact, twixt foe and foe,

Knows not the ancient custom, for twas right,

In the absence of a pact, to scorn and shame

Any man that another’s steed did maim.

They struck the visor, which was doubly strong,

Yet would scarcely serve to deflect the blow,

And many such they dealt, to right a wrong,

Like bursts of hail that mar the crops below,

Breaking stalk and stem as they drive along,

Destroying every hope of harvest so.

What Durindana and Balisarda

Could do, you know: if wielded with ardour.

And yet so prudent were the pair, that they

Failed to land a blow worthy of their might,

Till Mandricardo made a frenzied play

That nearly did for Ruggiero outright;

His shield was sliced in two, and torn away,

By one of those strokes that either knight

Was able to land, while his breastplate too

Was pierced, and the cruel blade drove on through.

Canto XXX: 53-57: Ruggiero recovers and wounds Mandricardo

That fierce blow nigh on stopped every heart

Amidst those there, thinking Ruggiero slain,

For most had taken that warrior’s part,

As he sought right and honour to maintain;

And had Fortune not seen fit to depart

From his side, those folk had hoped he’d attain

To Mandricardo’s death or his capture:

Thus, the blow seemed ruinous in nature.

That an angel intervened, is my belief,

To save Ruggiero from that blow,

For without delay, seeking scant relief,

He pointed Balisarda at his foe,

Struck the helm, but much to his great grief,

Such was his haste it failed to bestow

All he sought, though he was less to blame

Being with indignation all aflame.

Yet if his aim had been but straight and true,

The virtues of the helm had proved in vain;

So fierce the blow that Mandricardo knew,

From his hand he let fall the courser’s rein.

Thrice he swayed, was nigh lost, then anew

Raised himself, as his steed scoured the plain,

Twas Brigliador, whom you already know,

Whose change of master yet filled him with woe.

Never did trampled snake or wounded lion

Rage with such fury as did the Tartar,

As he swayed, and was carried here and yon,

While from that blow he sought to recover.

Yet as his anger and his pride drove him on,

So, his strength he regained, and his valour.

He wheeled and drove the steed at Ruggiero,

With his sword raised on high to deal a blow.

He rose tall in his saddle, and then aimed

His sword at Ruggiero’s head, and thought

To cleave him to the chest, and yet unmaimed

Was that skilled warrior; who swiftly sought

Before the stroke had thus his helmet claimed,

To lunge beneath its arc, and so he caught

The other’s chain mail, opening a space

Neath the right armpit, while guarding his face.

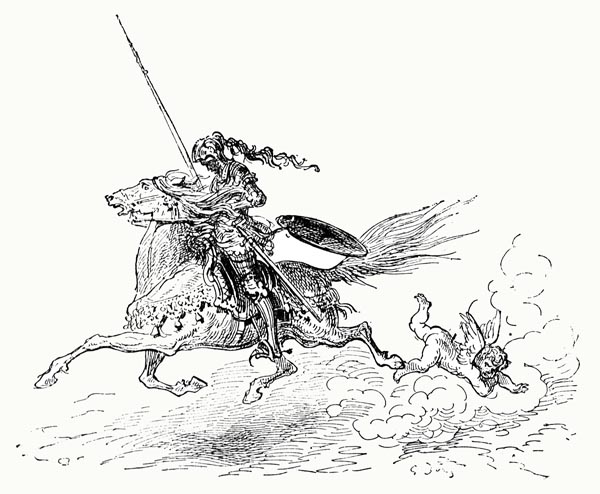

Canto XXX: 58-64: And then finally slays him

He drew brave Balisarda backwards then,

As spouted forth the hot and crimson blood.

Durindana was denied the strength of ten

His foe’s arm had possessed, yet, midst that flood,

Ruggiero felt the sharp sword strike again,

And closed his eyes with the pain, ere he could

Compose himself, while great the harm indeed

Had been, had he a lesser helm, and steed.

Ruggiero paused not, but drove the courser on,

And, in the right side, pierced Mandricardo,

While the latter’s strong chain mail, thereupon,

Burst, though of fine steel, at that fierce blow.

The result of that blade’s fall was foregone,

Its enchantment intended to bestow

A power against which such could not prevail,

Whether charmed breastplate, or enchanted mail.

Whate’er the sword thus pierced it sheared away,

And left the Tartar wounded in the side,

Such that he cursed the sky, his rage in play,

Roaring more loudly than the breaking tide.

He yet prepared to strive, and win the day,

And so chose to hurl his shield far and wide,

With its eagle emblem, in his anger,

And then, with both hands, grasp Durindana.

‘Ah,’ cried Ruggiero, ‘it needs no more

To show your lack of right to that fair shield,

Since you hurl away what failed you before,

And your claim upon the emblem must yield’

Yet was forced a further blow to endure

From that mighty blade, famous in the field,

Durindana, that struck him with such power

It seemed a mountain’s weight was its dower.

Through the midst, it pierced his steel visor,

And well for him it failed to take his sight;

It struck the saddle’s pommel, then his armour,

And the steel case and skirts it oped, outright,

Though the metal was of a hardened temper;

And then, grievously, it wounded the knight.

For it struck his left thigh, and pierced the flesh,

And long it was ere that deep wound would mesh.

The blood that o’er their shattered armour played

Rendered it crimson, with its double stain,

Such that various were the claims now made,

As to which had achieved the greatest gain.

But Ruggiero soon the doubts allayed,

With his sword, many a knight’s true bane,

He dealt a blow to Mandricardo’s side,

Where the shield a defence had once supplied.

He pierced the left side of his breastplate

And found a passage to the heart below,

The sword-tip entering deep, such was fate,

And forcing Mandricardo to forego

His title to the eagle, claimed of late,

And Durindana; yielding to his foe,

What was dearer to him than sword or shield,

Sweet life itself, upon that bloodied field.

Canto XXX: 65-70: Though receiving a further wound himself

Not unavenged did Mandricardo die,

For at the moment that he felt the blow

The sword, still his awhile, that king let fly,

And had split the skull to the visor so,

If Ruggiero had not thrust the weapon by,

Having robbed him of his vigour, then, below

The right arm, struck the Tartar knight once more,

Who’d failed to strike as he had struck before.

Thus, Ruggiero was smitten by that blade,

At the very moment he slew the king,

And the iron band and steel cap that weighed

Upon his brow were both split by the thing,

While Durindana’s blow, though delayed,

Cut deep, two finger widths, in descending.

Ruggiero, stunned, fell backwards to the ground,

And dyed the earth bright crimson all around.

Twas Ruggiero fell first, with a clatter,

While so slowly did Mandricardo fall

Twas believed it surely was the latter

That had maintained his right before them all.

While Doralice made the like error

That on both tears and smiles was wont to call,

That day, for she gave thanks to God above

That the victory was gained by her true love.

But when by manifest signs it was known,

That the living lived, and the dead did not,

Their supporters were swift to change their tone,

Some relieved, while some bemoaned their lot.

The king, the lords, and those about the throne,

Gathered round, Mandricardo now forgot,

And embraced Ruggiero, friend to friend,

And did him grace and honour without end.

Most rejoiced with Ruggiero, and the joy

They showed without, their hearts felt within,

Yet Gradasso did other thoughts employ

Than his tongue spoke, amidst the happy din.

Pleasure his face showed, rather than annoy,

Yet envy, covertly, lurked neath the skin;

Blind chance or fate, he knew not which to blame,

Cursing both, the lots, and Ruggiero’s name.

How to tell of the affection, the kindness,

The favour by King Agramante shown

To Ruggiero, as a mark of his success,

Without whom not a banner had he flown,

Nor had sought foreign lands to possess,

(His allies’ loyalties as yet unknown)

And, whom, now Mandricardo was no more,

He prized above the rest, on this far shore?

Canto XXX: 71-73: Regarding Doralice’s fickle nature

Ruggiero’s support lay not merely

Among the menfolk, but the women too,

Who had left, midst the host, their own country,

Spain or Africa, their husbands to pursue.

E’en Doralice, though grieving loudly,

From her dead lover might have turned anew,

And, perchance, felt exactly the same,

Had her doing so not been curbed by shame.

I say perchance, since I lack certainty,

Though it might, readily, have proved so,

For such was the worth, and such the beauty,

The manners and address, of Ruggiero,

And she (as we know from her past story)

So ready some new lover to follow,

That she might indeed have taken his part,

And upon Ruggiero set her heart.

Though a living Mandricardo was of use,

What good was he to her, now he was dead?

Twas right to seek one, so she did deduce,

To meet her needs, night and day, in his stead.

Meanwhile the doctors were told to produce

Every remedy to mend the hero’s head,

And, addressing the results of the strife,

They, expertly, secured Ruggiero’s life.

Canto XXX: 74-75: The spoils are distributed

He was attended to, most diligently,

And beside him, oft, at night or by day,

To demonstrate his care, sat Agramante,

Such was the love for him he did convey.

Mandricardo’s shield and armour too, he

Ordered hung beside the bed, on display,

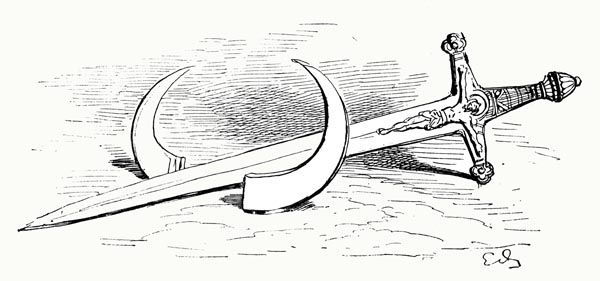

Except for Durindana, that fine sword,

Which the king to Gradasso did award.

Mandricardo’s other weapons and armour

Were, thus, granted as spoils to Ruggiero,

With Brigliador, that warlike charger,

Left behind, in his frenzy, by Orlando.

But Ruggiero gave the steed to his master

Agramante, knowing twould please him so.

Yet, enough, I must turn from Ruggiero

To she who longs and sighs for that hero.

Canto XXX: 76-80: We return to Bradamante

I speak of Bradamante, who had yearned

For the arrival of her messenger.

To Montalbano, Ippalca now returned,

Bringing news of the valiant lover.

Of Frontino Bradamante now learned,

And Rodomonte’s baseness did discover,

And how she’d found Ruggiero at the fount,

With Ricciardetto, and Agrismonte’s count;

And how Ippalca had left with Ruggiero

In hopes of finding said Rodomonte,

And punishing his theft of Frontino,

Seized from a woman, so abruptly,

And how, although they had sought to follow,

They had lost Rodomonte on the journey;

And then the reason why Ruggiero

Had not yet arrived at Montalbano.

And she spoke the words in full to her

That Ruggiero had offered in excuse,

And then she drew, from her breast, the letter

That he’d placed in her hand, to thus produce.

Bradamante, troubled, took the paper,

And read its contents; far more profuse

Her thanks had been had she not hoped to see

Ruggiero there, and not this proxy.

Having waited for Ruggiero, and instead

Obliged to have him there but in writing,

Gave her face a saddened air, as she read,

And a semblance of fear too, in so doing.

Ten times she kissed the page, and bowed her head

Ten times more, to him her love directing.

Only the tears she scattered from her eyes,

Kept it from kindling to her ardent sighs.

Five times or more she perused the letter,

And returned as many times to the maid,

Asking her to repeat, as messenger,

All that she was told, and now relayed,

Weeping all the while, nor would she ever

Have ceased, and an end to this have made

If she had not been solaced by the thought

That he must soon return, the one she sought.

Canto XXX: 81-85: Bradamante’s lament

A term of but fifteen, or twenty, days

Had Ruggiero set to his absence,

Sworn to Ippalca in a thousand ways,

Bidding her rely upon his presence.

‘Yet perchance adventure his course delays,’

Cried Bradamante, ‘or some brave nonsense

Oft present in war; what can assure me,

That he will indeed return to me shortly?

Alas, Ruggiero, who would have thought,

For I love you more than myself, that you

Could yourself love aught more, and, by report,

Not some friend but the foe that you pursue?

You harm where you should help, offer naught

To aid the one that loves you, and is true.

Nor know I if you think it praise or blame

To neither punish nor reward this same.

That your father was slain by Troiano

I know not if you know; yet these stones do!

And yet to aid Troiano’s son you’d go,

Agramante and his cause thus pursue.

Is’t your idea of vengeance, Ruggiero?

And is this the reward you grant those who

Did so avenge him? By rendering me,

Of his House, a martyr to his memory?’

Such words, and others, the lady addressed

To her dear Ruggiero, while weeping,

Though Ippalca sought to grant her some rest

By saying, often, that Ruggiero’s keeping

To his word was not in doubt, and twas best,

Since no other crop was worth the reaping,

In waiting patiently for that fair day

That he’d promised would soon end all delay.

Hope, that ever comforts those who love,

And Ippalca’s kindly solace so eased

Bradamante’s fears and grief as to prove

Of such virtue that tears and sorrow ceased.

She’d stay, at Montalbano, nor remove,

Until the term was done, and he was pleased

To return, as he had promised, though twas ill

His keeping of his pledge, she waiting still.

Canto XXX: 86-89: Ricciardetto gives her further news

But that his promise was not yet fulfilled

Was scarcely the fault of Ruggiero

The time by one thing and other filled

Until the term was passed, nor could he go

For he had after all been nigh-on killed,

In that fierce fight with Mandricardo,

And lay abed, at risk of death, I’m sure,

So deep his wound, for a month or more.

Bradamante waited, day after day,

Beyond the time that her knight had said,

With no more than Ippalca could relay,

And Ricciardetto who had homeward sped.

He told her how Ruggiero had made play

Of his foes, and freed the brothers that men led

Towards their death, and she the news did meet

With joy, though there was bitter midst the sweet.

For Marfisa figured in that discourse,

With somewhat of her valour and beauty,

While brave Ruggiero pursued his course

With her beside him to relieve the army,

Where, besieged and with the weaker force,

Agramante held his ground, though insecurely.

Such companionship Bradamante praised,

Yet was not pleased, nor were hopes thus raised,

Nor slight were the suspicions it aroused,

For if Marfisa was as fair as said,

And if such close friendship he’d espoused,

Twould be strange if his heart were not misled;

Yet she would not believe it, though it roused

Both hope and fear, that on its heels doth tread,

For the day that would bring joy or sadness,

And, in Montalbano, waited, nonetheless.

Canto XXX: 90-95: Rinaldo arrives, then returns to Paris with his brothers

Meanwhile, came Montalbano’s prince and lord,

Rinaldo, among her brothers first of all,

For proof of his brave deeds the tales afford,

(Yet in honour not in age, for she could call

On two who were his elders, I’ll record)

He who shone in splendour, midst that hall,

As the sun among the stars. He came at noon,

With one page, that was all, and none too soon.

The reason he was there was that from Brava

He was returning to Paris once again,

(He’d gone there searching for Angelica

As he did frequently, though all in vain)

And hearing the news from another

That Viviano and Malagigi, the twain

Were sent to the Maganzese that day,

Had hence to Agrismonte made his way.

There, hearing of their rescue, and the fall

Of their adversaries, scattered or slain;

That Ruggiero and Marfisa midst all,

Had triumphed there, and the spoils did gain,

And had arrived at Montalbano’s hall,

With his brothers and cousins once again,

Each hour had seemed to him as twere a year

Until he could embrace them, without fear.

Came Rinaldo to Montalbano, and there,

Embracing his mother, wife, and children,

His brothers, and his cousins free as air,

Seemed like a swallow, nesting o’er a garden,

That to its famished chicks did thus repair,

With full beak, bringing gladsome burden.

He stayed with them for but a day or two,

And then issued forth, companied anew.

Amone’s eldest son, Guicciardo,

Was there, Viviano, Malagigi,

Ricciardo, Ricciardetto, Alardo,

And all rode behind Rinaldo proudly.

But Bradamante waited on Ruggiero,

And on that day that came all too slowly,

Feigning to her brothers that she was ill,

And could not go, but must reside there still;

And, in saying she was ill, spoke most truly,

Though twas not a bodily pain or fever,

It was longing that weighed on her unduly,

Her love it was that made her soul suffer.

So, Rinaldo went his way with his party,

And with him, to the war, led the flower

Of his folk, and how to Paris then he came,

Another canto of mine shall proclaim.

The End of Canto XXX of ‘Orlando Furioso’