Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXVIII: The Innkeeper's Tale

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXVIII: 1-3: A cautionary word

- Canto XXVIII: 4-7: The beauty of Aistulf, King of the Lombards

- Canto XXVIII: 8-10: Faustus claims his brother’s looks to be superior

- Canto XXVIII: 11-17: Iocondo departs for Pavia, to his wife’s seeming distress

- Canto XXVIII: 18-20: He misses her gift and swiftly returns for it

- Canto XXVIII: 21-23: He finds himself betrayed, but leaves silently

- Canto XXVIII: 24-27: His beauty is impaired by his sorrow

- Canto XXVIII: 28-32: Iocondo languishes in Pavia

- Canto XXVIII: 33-36: He spies the Queen and a dwarf together

- Canto XXVIII: 37-40: He is pleased when the dwarf neglects the affair

- Canto XXVIII: 41-44: He reveals the situation to the king

- Canto XXVIII: 45-49: They set out to prove all women fickle

- Canto XXVIII: 50-52: They determine on finding one woman to suit both

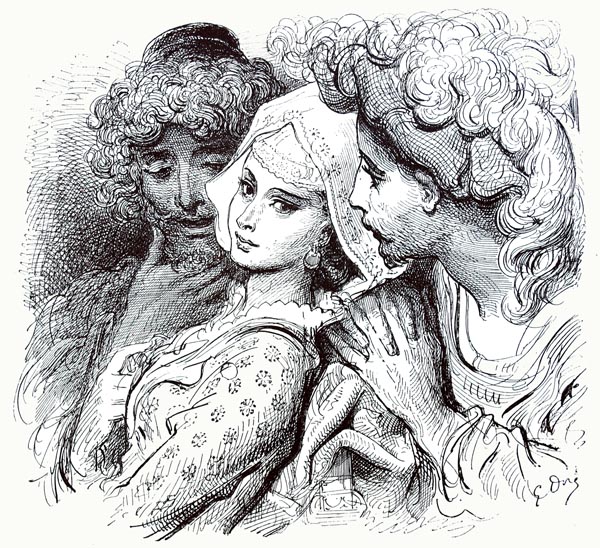

- Canto XXVIII: 53-55: They take the inn-keeper’s daughter with them

- Canto XXVIII: 56-61: She meets her former companion

- Canto XXVIII: 62-65: He sleeps with her covertly

- Canto XXVIII: 66-70: She confesses to Iocondo and the King

- Canto XXVIII: 71-74: After much laughter, they decide to return to their wives

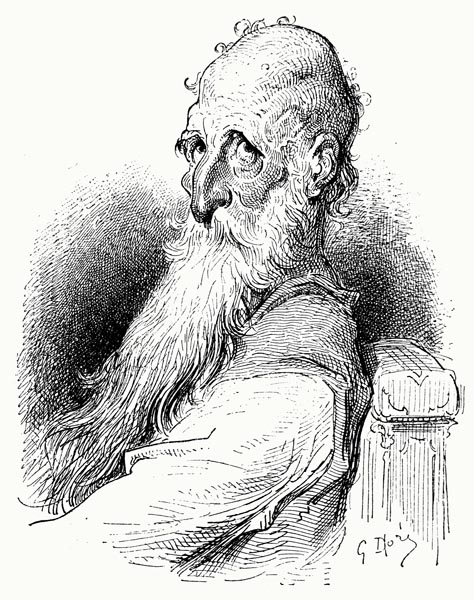

- Canto XXVIII: 75-84: Rodomonte is offered an alternative view of women

- Canto XXVIII: 85-90: He descends the River Saône

- Canto XXVIII: 91-94: And reaches Avignon, then Aigues-Mortes

- Canto XXVIII: 95-98: He meets Isabella, and his affections turn to her

- Canto XXVIII: 99-102: He seeks to seduce her from her intent

Canto XXVIII: 1-3: A cautionary word

Ladies, and all you that ladies cherish,

For God’s sake, close your ears to this story,

One the innkeeper told, with great relish,

To woman’s discredit, not her glory.

Tis well that such a tongue naught can blemish,

For as the saying goes, old and hoary:

The ignorant condemn all, out of hand,

And talk the more the less they understand.

Forego this canto, and my tale will be

As good as ever, not a whit less clear.

Yet, as Bishop Turpin told it formerly,

I tell it (nor from spite nor malice) here.

That I love you, I’ve expressed endlessly,

With a tongue that praised you many a year,

And in a thousand ways I’ve proved, and shown

That I am, and must ever be, your own.

Pass this portion by, and ne’er read a verse,

Or read whate’er you wish, and move on,

And believe in the matter we rehearse,

As much as you do in works of fiction;

But (turning to the story) our perverse

Innkeeper, seeing how they hung upon

His every word, ere the thing grew stale,

Seated, there, before the knight, began his tale.

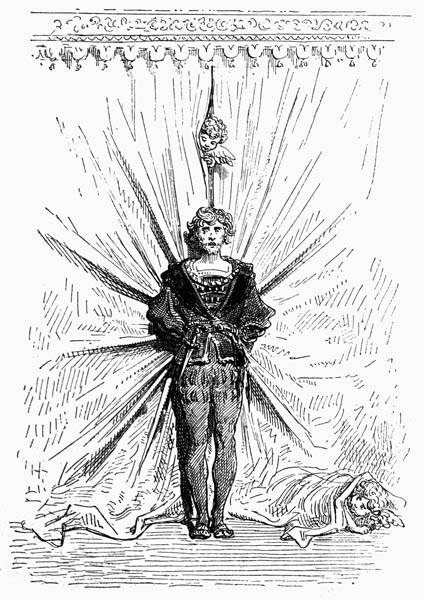

Canto XXVIII: 4-7: The beauty of Aistulf, King of the Lombards

‘Aistulf, King of the Lombards, who received

The kingship from his brother Ratchis (he

That entered a monastery) was perceived

To be the most handsome youth in Lombardy.

For nor Zeuxis nor Apelles achieved,

In their art such, a rare form of beauty.

Handsome indeed he was, and all thought so;

He thought himself yet more beautiful though.

He esteemed himself less for his kingdom,

In which he ranked above all other men,

The number of his subjects, or his income,

(That of his neighbours, and as much again)

Than the fact that he was young and handsome,

Deemed so by Christian and Saracen.

It so pleased him to have his beauty praised,

He was thrilled whene’er the subject was raised.

One amongst the court, dear to the king,

Was Faustus Latinus, a Roman knight,

That, hearing Aistulf, yet again, praising

His own lovely visage (a pleasing sight)

On being asked, by him, while so doing,

If any he’d seen offered more delight,

Such that his primacy might be denied,

To that monarch’s profound surprise, replied:

“From all I see, and from all I hear tell,

None on Earth compares to you in beauty,

(A beauty that o’er all folk casts its spell)

Except for one, a brother dear to me,

Iocondo is his name; yet one might well

Say that, but for him, you, assuredly,

Leave all behind, all the unlovely mass,

For he alone your beauty doth surpass.”

Canto XXVIII: 8-10: Faustus claims his brother’s looks to be superior

Aistulf thought the thing impossible,

For he’d assumed the palm was his indeed,

And so, he longed to meet with this mortal,

A lad whose beauty such great praise could breed.

He asked Faustus, if such were feasible,

To bring his brother there; so, twas agreed,

Though Faustus declared twould prove a labour,

To persuade one living far from Pavia

Where Aistulf held his court, who ne’er had been

Away from Rome, not even for a day;

For, since the lad had great good fortune seen,

He dwelt there tranquilly, at peace alway,

His inheritance intact, his gaze serene,

His wealth nor more nor less; he might well say

That Pavia seemed as far as to another

Tanais might prove; such was his brother.

And then the difficulty would be greater

In tearing him from the wife he so loved,

That he was bound to her, and was ever

Subject to no will but hers, and unmoved

By others’ wishes; and yet his brother

He would seek out, since his sovereign proved

So persuasive; while, in his turn, the king,

Offered gifts designed to bring about the thing.

Canto XXVIII: 11-17: Iocondo departs for Pavia, to his wife’s seeming distress

Faustus departed, and a few weeks later

Entered Rome, and the paternal mansion.

There, his fervent pleas so moved his brother,

That he made him of his own persuasion,

And, though twas difficult, found the counter

To the wife’s dismay, and each objection,

By propounding the good that must ensue,

And the gratitude that must prove their due.

Iocondo named a day for his departure,

And gathered his servants and his steeds,

And prepared the finest clothes (our nature

Benefitting from fine dress, as fine deeds).

At his side, by night and day, did feature

His tearful wife, who, seeing to his needs,

Declared she knew not how she might endure

Such long absence; not death could pain her more;

That the thought alone produced such misery

Twas as if her heart was drawn from out her side.

“Ah, come, weep not, my life, that this must be!”

(Weeping no less than her) Iocondo cried.

“So may this journey prosper, happily,

That here but two brief months shall you abide

Without your spouse, no longer shall it be,

Though the king should grant half his realm to me.”

But little comfort to his wife this brought,

For such an absence was too long, she said,

And it would be no wonder if he sought

For her, on his return, and found her dead;

Grief, night and day, so weighed upon her thought,

That she could eat not, nor could rest abed.

So that, for pity, the youth repented

Of his promise, having thus consented.

From her neck, she unloosed a costly chain,

Which a gemmed cross and holy relics bore.

(These a Bohemian pilgrim, with much pain,

Had garnered, on some distant sacred shore.

From Jerusalem, in sickness, once again

Returned, he had entered her father’s door,

Died in that house, her father was his heir)

And she gave this to Iocondo to wear,

That he might place it round his neck, and so

Bear it and thus remember her forever.

Her spouse was happy to receive it, though

Needing naught to prompt him to recall her,

For neither time nor absence would e’er show,

In good or ill, cause for him to waver,

Or forego the love, deep and strong, that he

Felt then, and must through all eternity.

The night ere the dawn of his departure,

Iocondo thought his wife would die, indeed,

Of the pain inflicted by her loving nature,

Though he must leave her at the time decreed.

She could not sleep, a wretched creature;

He left an hour ere twas morn, as agreed,

Mounted his horse, and then away he sped,

While his weeping spouse returned to bed.

Canto XXVIII: 18-20: He misses her gift and swiftly returns for it

He was scarce ten miles upon his way,

When the holy cross, her gift, came to mind,

Placed neath his pillow, the previous day,

And now, through forgetfulness, left behind.

“Alas,” he thought, “what could I do or say,

To save myself, if she that gift should find?

She must not know how careless I now prove,

Forgetting that which speaks of boundless love.”

He sought an excuse, then fell to thinking

That any such would not be well received

If a servant were to speak it, conceding

That he must go himself; the thought conceived,

He said to Faustus: ‘While I’m returning,

Go on to Baccano; once I’ve achieved

My errand, as I must, or ill twill bode,

I’ll hope to join you later, on the road.

The task no other should perform but I,

Doubt not but I’ll soon you join further on.”

Then said adieu, and down the road did fly,

At a trot, then a gallop, and was gone.

As he crossed the river, the sun was high

And the shadows had all vanished therefrom,

He reached his house, sought the bed, and found

His wife, neath the canopy sleeping sound.

Canto XXVIII: 21-23: He finds himself betrayed, but leaves silently

He raised the coverlet, without a word,

And scarcely could believe the dreadful sight,

For his chaste and faithful wife ne’er stirred

From the arms of the youth who held her tight.

He knew this adulterer, a lad preferred

By him, for the sun was shining bright

Through the window; this was a page he’d raised,

Of humble birth: Iocondo stood amazed.

Tis better to speak it, and bear witness,

That others might credit an affair,

Than experience Iocondo’s sadness,

And such pain and distress be forced to share.

Assailed by anger, he, nonetheless,

Drew his sword so he might despatch the pair,

But the love, despite himself, he still felt

For that wife of his, their salvation spelt.

Nor did this love that mocked him so, permit

(So utterly was the poor man its slave)

Him to wake her, lest she be pained by it,

Being caught, that is, in a crime so grave.

As best he could, he made a swift exit,

Descended the stair, mounted, and gave

His horse the whip, Love having whipped him so,

And joined Faustus ere he’d reached Baccano.

Canto XXVIII: 24-27: His beauty is impaired by his sorrow

His looks seem altered now, to one and all;

They saw his heart was heavy, yet none knew

The secret of his sorrow; bitter gall

It seemed, and yet the reason none could view.

They thought he’d gone to Rome, you recall,

Yet Corneto (that ‘horned’ town) saw him too!

All believed twas Love had caused him pain,

But in what manner none could yet explain.

Faustus thought his brother grieving

At having left his wife sad and lonely,

While he on the contrary was cursing

That she enjoyed such brave company.

Meanwhile, with furrowed brow, and ever musing,

His brother now eyed the ground, morosely,

As Faustus, sought to comfort him again,

But with the cause unknown, twas all in vain.

The salves that he now sought to employ

To heal the wound, increased the misery,

For his speaking of his wife brought no joy,

But simply incised the wound more deeply.

His brother took no rest, all must annoy;

His appetite was lost, as if completely,

And the face that shone with beauty before,

So changed that it was handsome no more.

His eyes now seemed quite sunken in his head;

Thinner in the face, his nose seemed larger;

Little beauty now remained, and instead

Of a paragon’s, he cut a graceless figure.

By the Arbia and Arno, half-dead,

He journeyed, nigh consumed by wasting fever,

Aught of beauty that sorrow had not undone

Doomed to fade, like a cut rose in the sun.

Canto XXVIII: 28-32: Iocondo languishes in Pavia

Faustus, besides grieving that his brother

Had been reduced to such a sorry state,

Regretted that he’d deceived his master,

Aistulf, to whom he’d praised him, of late,

Promising the most handsome courtier

Of all, and bringing one ruined by fate.

But they still rode on their way together,

And so came, in the end, to Pavia.

Fearing to bring the youth before the king,

And thus reveal his own lack of judgement,

He first informed him of his bringing

One whose deep sorrow had caused impairment,

And that the beauty of his face was fading,

Harmed by his heart’s woe, to his detriment,

A secret wound matched by a vile fever,

Such that he seemed himself no longer.

King Aistulf welcomed his brother’ coming,

With a show of friendship great as any,

Though in this mortal world there was nothing

That he’d wished to view more than his beauty.

Nor was he displeased that it was waning,

Noting his own’s superiority,

Which might well have been matched, the monarch feared,

By Iocondo’s, that some bitter flame had seared.

Lodged in the palace, his new visitor

Could be seen every hour of every day,

And, thus, the king could observe the stranger,

And to Faustus and his brother honour pay.

Meanwhile Iocondo languished, as ever,

Thoughts of his wife tormenting him alway.

For neither pastimes nor sweet music eased

His endless woe a jot, and nothing pleased.

Before his chambers, on the upper floor,

Next to the roof, there was an ancient hall.

Where alone (since he could delight no more

In seeing others, and so shunned them all)

He withdrew, while ever adding, to his store

Of heavy woe, fresh grief to pierce and gall.

Yet there he found (who’d have thought it, truly?)

That which healed him of his wound completely.

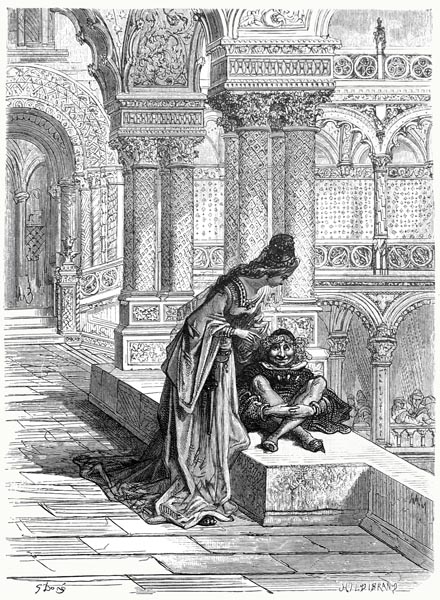

Canto XXVIII: 33-36: He spies the Queen and a dwarf together

At the end of the hall, where it was darker,

(For the windows set there were closed alway)

A beam of light issued from a corner,

Where the walls fitted ill, and there did play.

He set his face to the gap and saw, further,

Something hard to believe if but hearsay;

Naught was he told, but saw with his own eyes

What none could believe, or e’en surmise.

He could see into the Queen’s apartment

Her finest, and her most private, chamber,

Which none could enter lacking her consent;

None but the most faithful saw it ever.

As he gazed, he saw, to his amazement,

That a dwarf was wrestling closely with her;

Though little, he’d the better of her so,

Since he was atop, and the queen below.

Iocondo was dumbfounded and amazed,

And, thinking he was dreaming, stared awhile,

Until, no longer thinking he was dazed

And this a dream, he realised all was vile.

As at that scorned, misshapen form he gazed,

“She submits to such a man as must defile

One who’s wed” he cried, “to the fairest knight,

And most gracious king. Oh, what appetite!”

And then his wife whom he ne’er ceased to blame,

He thought of, who a pageboy had received,

And deemed excusable her want of shame,

Though the pair had betrayed him, and deceived.

Twas the fault of her sex that one should name,

Ne’er content with but one man, he perceived;

And if each shared the same sad taint, at least

His spouse had foregone coupling with a beast.

Canto XXVIII: 37-40: He is pleased when the dwarf neglects the affair

The following day, at that self-same hour,

Iocondo returned to the self-same place,

And espied the dwarf in the lady’s bower,

Bringing upon the king the like disgrace.

He found them to the utmost of their power

Doing so alway, with ne’er a day’s grace,

While the queen (much to Iocondo’s wonder)

Denounced the neglect shown by her lover.

One day, before the monarch, with the rest,

He saw she was possessed by melancholy.

For she had, through her maidservant, addressed

This lover, and yet had found him tardy.

Sent there a third time, the girl expressed

Her annoyance: “He’s gambling, my lady,

And lest he lose some fraction of his stake

The churl will not that game of his forsake.”

At this strange spectacle his eyes grew bright,

His brow was smoother, and his whole face cleared;

As joyful as his name, now seemed the knight.

Once restored, smiles not tears then appeared;

He gained weight, and a Cherubim in flight

Borne from Paradise, he seemed, his heart cheered.

The king, his brother, all the household there,

Of the change in his looks were now aware.

If Aistulf wished to learn, from Iocondo,

What had caused the sudden transformation,

No less keen was he for the king to know

All about the queen’s vile situation.

Yet he wished him to refrain, even so,

From revenge, based on his information.

To expose and yet not harm the lady,

He made the king swear on the Agnus Dei.

Canto XXVIII: 41-44: He reveals the situation to the king

He had him affirm that whate’er he saw

Or heard, which might seem to him most ugly,

(Even though the appearance that it bore

Looked to harm His Majesty, directly)

He would ne’er seek revenge; furthermore,

He bound Aistulf to utter secrecy.

(So that the malefactor would not learn,

By word or deed, what the King might discern.)

The king, who aught else would have believed

Before such a thing, gave his oath freely.

Iocondo then affirmed he’d been deceived,

And that was why he, in truth, had slowly

Languished from the hurt that he’d received,

On viewing his wife with one most lowly;

And said that he’d have died, twas his belief,

If he’d had to wait much longer for relief.

Twas in His Highness’ palace he had seen

The thing that had greatly eased his woe,

For if he were deceived, he had not been

Alone in that, he claimed; and, saying so,

He led the king to where a man might glean

A view of that vile brute, and there, below,

The mare, and not his own, that he did ride,

And spurred, and made her rear her back, beside.

You may believe the act seemed to the king

A deed of shame, without me swearing so,

He seemed distraught, raging at everything,

And striking the walls, with his head, in woe,

He cried aloud, his oath intent on breaking,

Yet forced himself to silence, drove below

His boundless anger and his bitter scorn,

Since twas upon the sacred host he’d sworn.

Canto XXVIII: 45-49: They set out to prove all women fickle

“What counsel can you offer me, brother?”

He asked Iocondo, “Since you’ve ensured

I may not wreak vengeance on the sinner,

Nor sate my anger, nor cry this abroad.”

Iocondo answered, “Naught let them suffer

But rather let us greater proof afford

That all women are as weak, let us begin

To take what others from our wives now win.

We are both still young, and of a beauty

That cannot easily be found elsewhere,

What woman will not please us readily

If with the ugly their delights they share?

And, if beauty and youth fail completely,

Then our wealth may aid us everywhere,

Nor would I that we come here again,

Till the spoil, from a thousand wives, we gain

Long absence, viewing places far away,

And the company of other women,

Will both serve the heart’s passions to allay,

That much pain and trouble oft have given.”

The king was pleased, nor would he brook delay,

And so, the next morn, when the sun had risen,

He and the Roman knight took to the road,

With two squires, on whom their gear was bestowed.

Disguised, they passed through Italy and France,

Then Flanders, and so reached the English shore,

And when they met a lovely woman’s glance

Found her open to their pleas, and much more.

They gave, and yet regained their advance,

For what was spent another would restore.

They made request of many a wife indeed,

But many a wife prayed to them, in need.

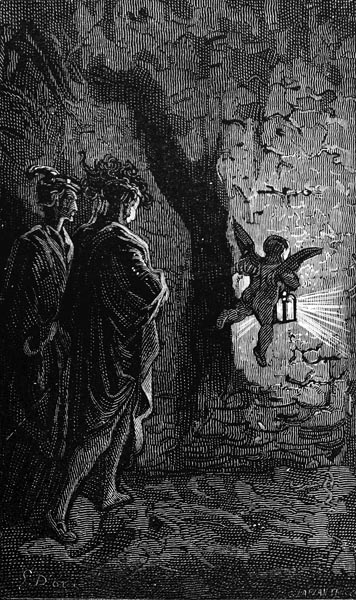

![Ariosto - Orlando Furioso - Canto XXVIII: 48 [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Italian/interior_ariosto_orlandofurioso_cantoxxviii48b.jpg)

They stayed a month in this land, and that, two;

And solid proof they thus did ascertain.

Those women were as faithless and untrue

As their own wives, whatever they might feign.

But ever chasing after something new,

Led the two, more often, to complain,

For entering another’s door (or purse)

Meant risking their death, or something worse.

Canto XXVIII: 50-52: They determine on finding one woman to suit both

“Twere better,” said Iocondo, “if we found

One wife whose face and manner pleased us both,

One where we may meet on common ground,

And ne’er show jealousy, as if on oath.”

“Why should I,” the king exclaimed “not be bound

By such, as any other?” nothing loath;

“It seems that to each of this female crowd

More than one man is, frequently, allowed.

One we want who will not constrain us,

But whene’er natural need should arise,

In joy, and peace, she may entertain us,

Without any conflict, or tears, or sighs.

Nor would the harm to her be grievous;

If every wife had two spouses, likewise,

She needs but be faithful to two, not one,

And we might hear less quarrelling, or none.”

The king’s proposal seemed to well-content

The Roman knight and so it was, the pair,

Upon achieving their ambition bent,

O’er hill and plain pursued the bold affair.

They found a woman matching their intent,

Fair in form and manner, they might share,

She was a Spanish innkeeper’s daughter;

The inn he kept was at Valencia.

Canto XXVIII: 53-55: They take the inn-keeper’s daughter with them

Still at an age as yet unripe but tender,

She was in truth a flower in her first bloom.

Many a child, already, had this father,

And sought to grant poverty little room;

So, twas but a swift and simple matter

To yield them his daughter, I presume,

For they promised to treat her courteously

Where’er they might go; and thus made three.

She went with them, and pleasing they found her,

Taking turns, in peace, most generously,

As if they passed each other the hammer

And struck the anvil fiercely or gently.

To see all Spain was the wish of either,

So, through Siface’s realm they sped swiftly,

And that same day they left Valencia

They halted at the inn at Xàtiva.

The travellers went to view the palaces,

The streets, and public and holy places,

A practice they employed, more or less,

In every country where they left their traces;

The girl remained at the inn, with the rest,

The valets seeing to the beds, the horses,

And taking care that a meal awaited

Their masters return when they were sated.

Canto XXVIII: 56-61: She meets her former companion

Now, a youth there was, in that hostelry,

Who’d worked in her father’s inn before,

As a groom, and knew her from infancy,

And love towards each other this pair bore.

They would glance, at each other, secretly,

Without seeming to, fearing to do more,

And, when their lords and masters could not see,

Spoke with each other, surreptitiously.

The lad sought to know why she was there,

And asked which of the two lords thus laid claim

To her; Fiammetta told him of the pair,

Such was she called, “The Greek” was his sole name.

“Just when I’d hoped to make you mine, and care

For you, forever,” cried that very same,

“Fiammetta, my life, you’re lost to me,

No more, it seems, your face shall I e’er see.

All my sweet hopes are turned to bitterness,

Since you are others’ now, and leave me so.

For I’d planned, having laboured with success

To earn a little, and to save a tithe, also,

From my scant earnings, and from what the guests

Are kind enough to grant me as they go,

To seek Valencia and ask permission

Of your father, to wed you; such my mission.”

The girl shrugged her shoulders, and replied

That he came too late, and naught could be done.

The Greek now feigned grief, and wept, and sighed:

“Will you then see me die, my lovely one?

In your arms let me expire,” the lover cried,

“Let me but once your tender charms have won;

For every moment, ere you leave, that’s spent

Beside you will grant that I die content.”

Fiammetta, pitying him, gave answer:

“Believe me, I wish that no less than you;

But, surrounded by as many eyes as ever,

Neither time nor opportunity accrue.”

Yet the Greek pursued the matter further:

“Were you but true to me as I am true,

I think you might yet find somewhere tonight,

Where we might lie together till first light.”

“How can I,” she cried, “when all night through

I’m forever trapped, now, between that pair,

Pestered by one or tother of those two,

And clasped in an embrace that I must share?”

“Why,” cried the Greek,” the thing’s naught to you,

No doubt you know how to escape from there,

And could slip from between them easily;

And that you shall, dear, if you pity me.”

Canto XXVIII: 62-65: He sleeps with her covertly

She thought awhile, then told him he must come,

When he believed the household were asleep,

Then how to reach her silently, where from,

And next, in going, what watch he must keep.

He approached as she’d said, noiseless and dumb,

When he thought all were lost in slumber deep;

Then he pushed, till it yielded, at the door,

Entered softly, and tiptoed o’er the floor.

Short and cautious steps he took, and was sure

To always keep one foot planted firmly,

As if glass was scattered o’er that chamber floor,

Or he feared to tread on eggs; carefully,

He extended his arms a little more,

Till his fingers found the bed, then, quietly,

Headfirst he entered where the others lay,

Claimed his Fiammetta, and began to play.

He placed himself between her tender thighs,

Since she lay on her back; when all was set,

He clasped her in his arms, stifled her sighs,

And pressed himself upon her, till they met;

He rode hard upon that steed, his fair prize,

Nor needed any other; without let,

He trotted, galloped, ambled, like a knight

Nor dismounted, but continued, all the night.

King Aistulf and Iocondo both perceived

Wild movements that shook the bed about,

And yet the self-same error both deceived,

For each thought “My companion tis, no doubt.”

Once the Greek’s destination was achieved,

As he’d entered, he silently slipped out.

And as the sun a new day did begin,

Fiammetta rose, to let the valets in.

Canto XXVIII: 66-70: She confesses to Iocondo and the King

Aistulf said to Iocondo, as in jest,

“Brother, tis a journey you have gone,

Twere well that you took some time to rest,

Having ridden so, all night, off and on.”

“I was about to say the same:” confessed

Iocondo, “you’ve performed a marathon;

Tis you that should lie down, though it be light,

Having hunted, up and down, all this night.”

“I?” said the king, “I’d have unloosed my hound

And run a course, if you had been so kind,

As to lend me the horse, and quit the ground,

And not left me to toss and turn, behind.”

Iocondo cried: ‘As your vassal am I bound,

You may dictate whatever comes to mind;

Tis unseemly to claim what is not so,

Tis yours to say whether she’s mine or no.”

If one spoke, then the other added more;

They ended by quarrelling most fiercely,

And dealt each other such brave words of war,

Both of them were well-nigh mocked entirely.

The pair summoned Fiammetta, therefore,

(As witness to the truth, the girl was clearly

Most afraid) each demanding she not hide

That his friend had done the deed, and had lied.

“Confirm”, the monarch said, with haughty gaze,

“You need not fear, now, either of us two,

That twas he who in pastures sweet did graze

While I remained a world away from you.”

Each disbelieved the other, in a phrase,

And waited for the answer, that fell due,

While Fiammetta threw herself on the floor,

Once discovered, of surviving this, unsure.

She begged their pardon that love had urged her

To introduce a young man to their bed,

Out of pity for one she’d made to suffer

Heart’s torments; twas a youth she’d hoped to wed.

That night she’d fallen into mortal error,

Yet had hoped that, when the hours were sped,

They’d both be of the same opinion:

That the deed was done by his companion.

Canto XXVIII: 71-74: After much laughter, they decide to return to their wives

Iocondo and the king gazed at each other,

In a stupor, from amazement and confusion,

Never having heard of two such, ever,

That had suffered from a like delusion.

Open-mouthed sat fond lover by lover,

And then roared with laughter; in conclusion,

Scarcely able to breathe, with what she’d said

Delighted, they fell backwards, on the bed.

They laughed so hard their chests ached, and their eyes

Were full of tears of joy; their sole request,

Of each other: “How can we now disguise

Our folly, and not be but woman’s jest;

For we have failed to guard our lovely prize,

Betwixt us two, by neither one possessed?

Though a husband acquired more eyes than hairs,

He’ll be fooled yet by these schemes of theirs!

We’ve assayed a thousand, and all fair,

And found not one that worked otherwise.

If we tried the next, her actions would compare;

Yet let this one be the last; let us be wise.

That our wives are no worse, in this affair,

Than others, and as chaste, we may surmise.

If they but do as all the rest have done,

Twere better to return to them anon.”

This decided, they despatched Fiammetta

To find the lad, and next, before the rest,

Declared her his wife, and then her lover

Accepted gifts from both, at their request.

Then they mounted, and made their departure,

And headed for the east, since to the west

They’d strayed, and so they sought their wives again,

Nor thereafter found reason to complain.’

Canto XXVIII: 75-84: Rodomonte is offered an alternative view of women

Thus, the innkeeper ended his bold tale,

Listened to by all, with great attention.

With Rodomonte silence did prevail,

He revealed not a sign of dissension,

Then declared: ‘Tis the truth in each detail;

For every woman’s powers of invention,

Seem infinite, and not a thousandth part

Could one grasp, despite all one’s skill and art.’

There was an elder midst that company,

Wise yet bold, and sounder than the rest,

That unable to sit there silently,

And hear all women slandered, though in jest,

Turned to him who had told the story,

Crying: ‘Many a thing folk will attest

That not an ounce of the truth doth contain;

That this fine tale of yours is one, tis plain.

I give credence to not a word you’ve said,

Not though the Evangelist said the same;

Mere opinion, not experience, has led

You to lodge, against woman, such a claim.

Your malevolence against a few has bred

A desire that the sex should bear the blame.

Yet, if you can be calm, I’d have you hear

Praise of them not blame, so lend an ear.

For he that would praise them has a greater

Field to exploit than he that would speak ill.

A hundred he might name we should honour,

For every one that shows but evil will.

Blame not all, and aim to laud those rather

That excel, and seek their virtues to distil.

And if Valerio has taught you otherwise,

His true feelings he’s laboured to disguise.

Tell me, is there one among you, truly,

That has never proved unfaithful to his wife?

Who, when granted the opportunity,

Has not gone with another? Why, tis rife.

Is there one, in all this world? Inform me.

Whoever claims so, lies, upon my life,

Yet how many have had designs on you?

(Except those that for a living so do?)

Know you a single man that would not leave

His wife alone, though she were young and fair,

To follow another, and that wife deceive,

If he thought he’d gain ready access there?

What would he not do were he to receive

Gifts from a woman, with her plea and prayer?

I think he’d give his soul to please that one,

Or his flesh at least, when all is said and done.

Those that leave their husbands have good reason;

The man is bored at home, and listless too.

When he’s not he’ll gladly commit treason,

And other women eagerly pursue.

Wishing to be loved, at every season

They but seek love, and grant what is their due;

And I would pass a law, this very hour,

That no man could oppose, had I the power.

It would read that every woman taken

In adultery, should be slain, there and then,

If she could not claim and it be proven

That her spouse had but done the same again.

If proved it was, she’d regain her freedom,

Neither spouse nor court might hound her, amen.

Christ in his precepts said as much, indeed;

“Do as you would be done by” was his creed.

Ascribe incontinence to those who show it,

And not to the whole sex, because some do.

Who do so more than us? (And you know it!)

Not to one sex alone adultery’s due.

Let ours be the shame if we’d bestow it.

Blasphemers, thieves, rapists, traitors too,

Usurers, murderers, we rarely see

Except among our own sex; there they be.’

Then, his speech sincere and just, the elder,

Gave many an example, of good women,

That, in both their thoughts and deeds, had ever

Proven chaste, though, at this, the Saracen,

Scowled threateningly, disinclined to suffer

The truth to be heard, till, there and then,

The wiser man, through fear, ceased to name

Such women, his opinion, though, the same.

Canto XXVIII: 85-90: He descends the River Saône

Having put an end to all contention,

Rodomonte left the table, and went

To his bed, to rest, until the morning sun

Drove the shadows from the air, though he spent

More of the night sighing for the one

He loved than sleeping, foiled of his intent;

And so, with the sun’s first dawning ray,

Boarded a vessel to pursue his way.

For he held the respect for his good steed

That a knight should have for one so fine,

(Though twas his despite Ruggiero indeed,

And Sacripante) and thus his design,

Having travelled two full days at speed,

And wearied it, was to find a more benign,

Mode of transport, for his own ease as well,

And make better speed by water, for a spell.

Without delay, the bargeman launched the boat,

And commanded each man to ply his oar,

While the lightly-laden craft, once afloat,

Was soon gliding by the Saône’s pleasant shore.

Yet his gaze was still troubled and remote.

Care travelled behind him, and before.

He found it at the stern, and at the prow;

He’d borne it as he rode, and did so now.

In his head or in his heart, care sat alway,

Depriving him of comfort, and of rest.

The wretched man could not his pain allay,

For the enemy was there in his own breast,

Nor could he hope for mercy, night or day,

Since by his very self he was distressed;

Warring within, vexed ever by his foe,

That cruel one who brought not aid but woe.

All that night, and the next day, his journey

Rodomonte pursued, with heavy heart,

Still musing on the lasting injury

Dealt by both king and lady, that fierce dart.

For the self-same thoughts brought him misery

Once on board, as before they did depart.

Such a flame could not be quenched by water,

Nor could change of place his anguish alter.

Like one who’s wearied by burning fever,

That tosses, weakly, from side to side,

Now the left, now the right, hoping ever

To reach a state of ease, and there abide,

Yet finds it not, this way nor the other,

But in all ways is by discomfort tried,

So, upon land and water equally,

That anguish was felt by Rodomonte.

Canto XXVIII: 91-94: And reaches Avignon, then Aigues-Mortes

He lost patience with travelling by water,

And had them land him on the eastern shore.

By Lyon, Vienne, and Valence, the courser

Sped, till the bridge at Avignon he saw.

These lands, and all those upon the other

Shore of the Rhône and conquered in the war,

Between the river and the Pyrenees,

Were Africa’s and Spain’s new territories.

He crossed the Rhône, and to Aigues-Mortes he rode,

Thinking to pass to Africa with ease,

And came to a stream and village, that showed

Allegiance to Bacchus and to Ceres,

But emptied now was every last abode,

Due to the conflict, and its injuries.

Here, and there, he viewed wave after wave,

That, here the vale, there the sea-shore, did lave.

And came upon a church, upon a hill,

New-built, yet abandoned like the rest,

For the war all about was raging still.

Rodomonte, the place at once possessed,

For its situation did calm instil,

Sequestered from the fields, and seeming blessed,

In that ill news could scarcely reach him there,

And, thus, for his Algiers he ceased to care.

He abandoned thoughts of Africa; the site

Appeared most suitable, and fair indeed,

And here he lodged his household outright,

And quickly found a stable for his steed.

Montpellier not far, yet out of sight,

Lay a few leagues distant, where every need

Might be satisfied; a stream ran nearby,

And their food the fields about might supply.

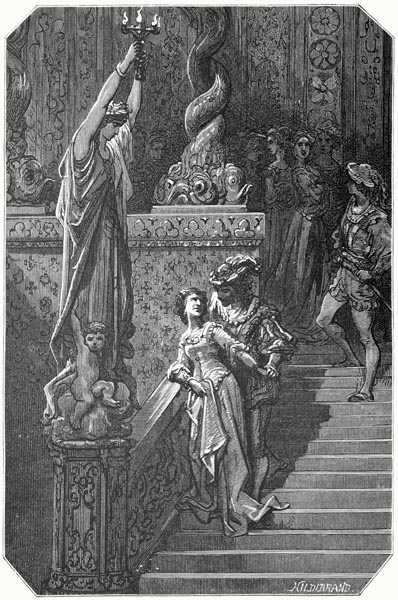

Canto XXVIII: 95-98: He meets Isabella, and his affections turn to her

Musing there, one day, Rodomonte

(Who spent most of his days deep in thought)

Saw a maid, whose face was sweet and lovely,

Tread the narrow path (as if the place she sought)

That crossed the flowery field below, while she

Was accompanied by a monk, of bearded sort,

And he led behind him a mighty steed,

Clothed in black trappings, of noble breed.

Now, who the monk is, and who the lady

You surely know, and what the steed bears there;

Isabella, it must be, and with the body

Of her once dear Zerbino in her care.

When she to Provence began her journey,

I left her with the old monk, thus, to fare.

He’d persuaded her to devote her days

To the service of the Lord, and His praise.

Though with pale and troubled face she went,

Though the maiden’s hair was loose and astray,

Though sighs from her burning breast she spent,

Though founts of tears fell from her eyes alway,

And though to grief her mien was testament,

(Many a tribute to the dead she did pay)

Yet such beauty her face and form did share

Love and the Graces sought a dwelling there.

As soon as Rodomonte saw the maid,

He laid the thoughts he’d harboured aside,

All that loathing of the sex he’d displayed,

The one by which the world is beautified.

While Isabella, to his eye, portrayed

All that a new affection might provide;

This fresh love now displacing the other,

As a nail extracts a nail from timber.

Canto XXVIII: 99-102: He seeks to seduce her from her intent

He met her with the mildest gaze he knew,

And the gentlest tones that he could muster,

And asked about her health, politely, too.

All that was in her mind she did utter,

As to how she’d left the world to pursue

Holy works, and to the Heavenly Father

Offer prayer, at which Rodomonte smiled,

Who gods, and law, and faith e’er reviled.

He called her intent a foolish error,

And said that she’d but wandered astray,

And as much to blame as any miser

That kept his treasure buried deep alway,

Such that none e’er received a measure,

Nor found profit in its use, night or day:

Enclose the lion, bear, and the serpent,

Not that which is yet fair and innocent.

The monk, that to all this had lent an ear,

Ready to prevent the incautious maid

Straying from a path, straight and clear,

And keep her to the course that he’d displayed,

Sought to spread his table with holy cheer,

A spiritual feast, most swiftly laid.

Yet to Rodomonte, all seemed bitter,

No sooner tasted than loathed, as ever.

He, having vainly sought to interrupt,

And perchance force the monk to hold his peace,

The rein of patience broke and, with abrupt

Blows of his fists, encouraged him to cease.

Yet, lest you’re, likewise, ready to erupt,

At my torrent of words, and seek your ease,

I’ll end the canto, and the like end reach

As the old monk attained by too much speech.

The End of Canto XXVIII of ‘Orlando Furioso’