Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXVII: Conflict and Discord

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

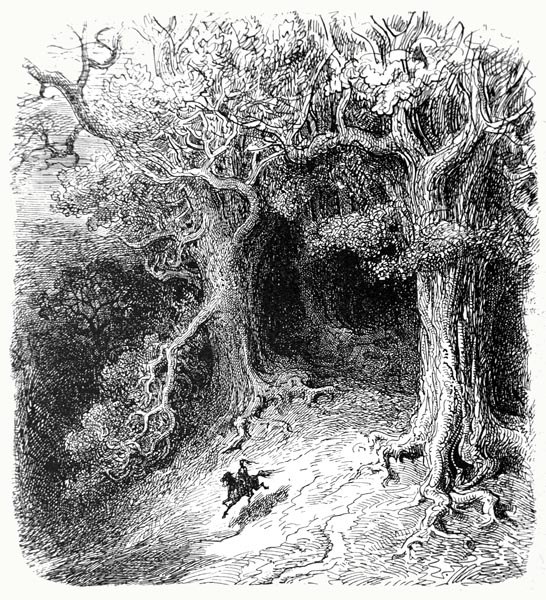

- Canto XXVII: 1-4: Unforeseen consequences

- Canto XXVII: 5-6: Rodomonte and Mandricardo pursue Doralice to Paris

- Canto XXVII: 7-12: Rinaldo returns there still seeking Angelica

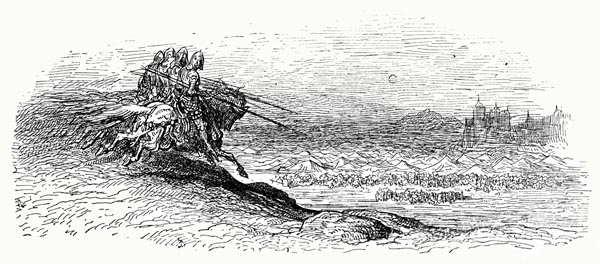

- Canto XXVII: 13-16: The warriors bring aid to the Moorish army

- Canto XXVII: 17-19: The first four arrivals launch a surprise attack

- Canto XXVII: 20-22: Charlemagne surveys the damage

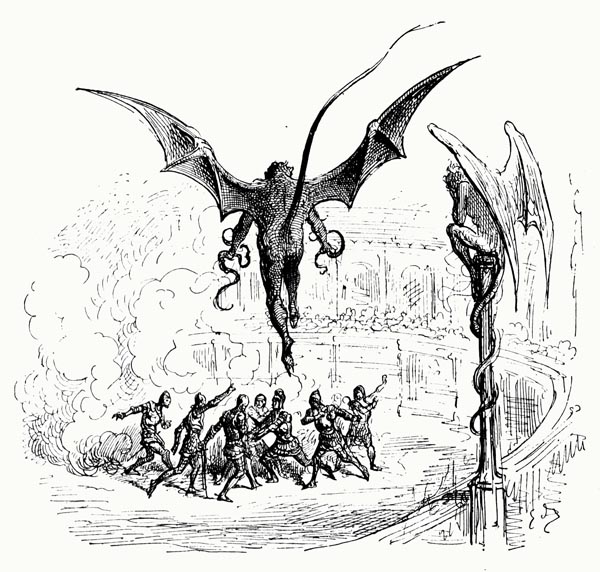

- Canto XXVII: 23-28: Ruggiero and Marfisa reach Agramante’s camp

- Canto XXVII: 29-33: The Christians retreat behind the walls of Paris

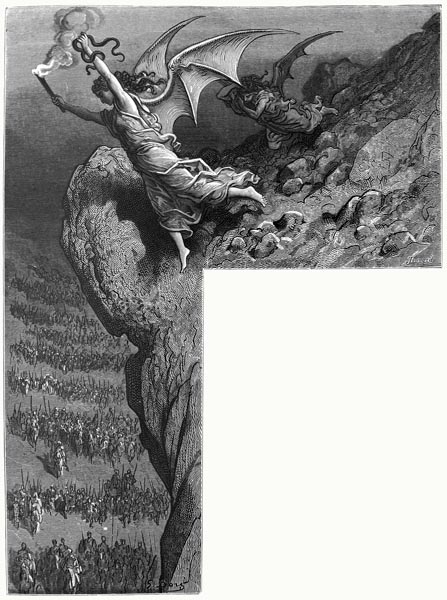

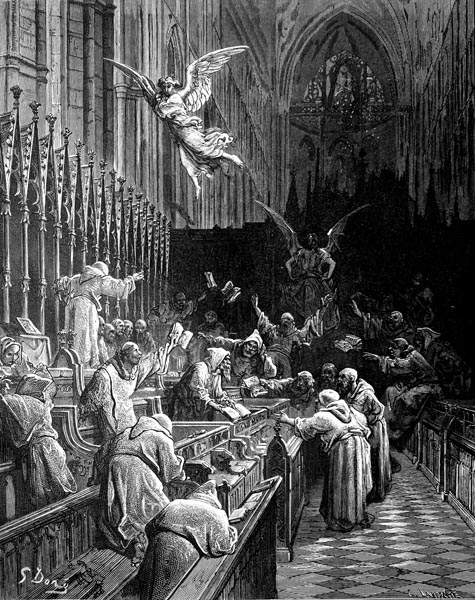

- Canto XXVII: 34-36: Saint Michael hastens to intervene

- Canto XXVII: 37-39: He sends Discord to rectify the problem

- Canto XXVII: 40-44: The warriors’ quarrels are renewed

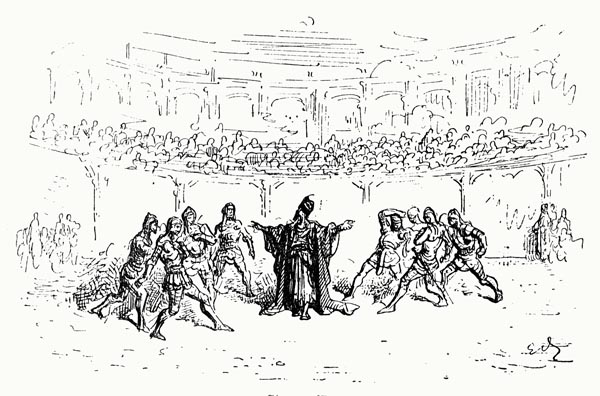

- Canto XXVII: 45-48: Lots are drawn and a place assigned

- Canto XXVII: 49-53: Mandricardo is angered

- Canto XXVII: 54-58: Gradasso lays claim to Orlando’s sword

- Canto XXVII: 59-63: Mandricardo seizes it from him

- Canto XXVII: 64-68: Agramante temporarily resolves the dispute

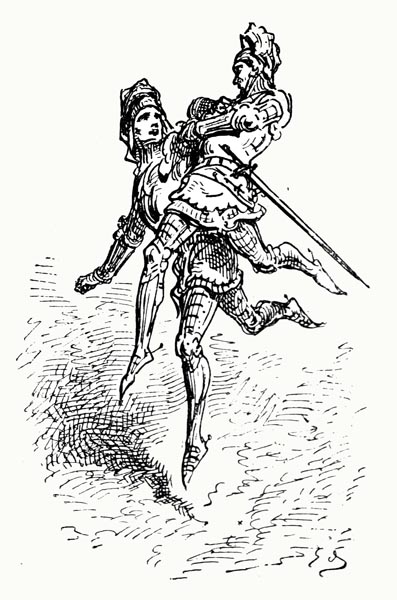

- Canto XXVII: 69-74: Meanwhile Sacripante lays claim to Frontino

- Canto XXVII: 75-79: He and Rodomonte spar together

- Canto XXVII: 80-84: Agramante again seeks the cause of dispute

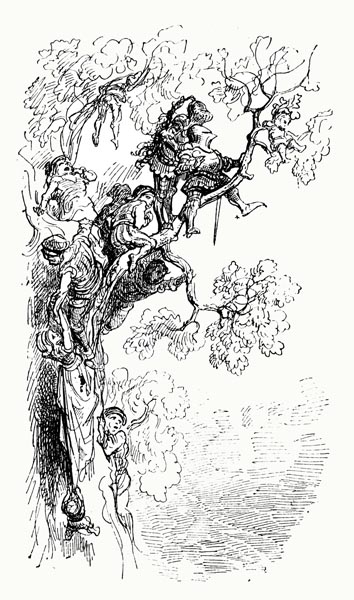

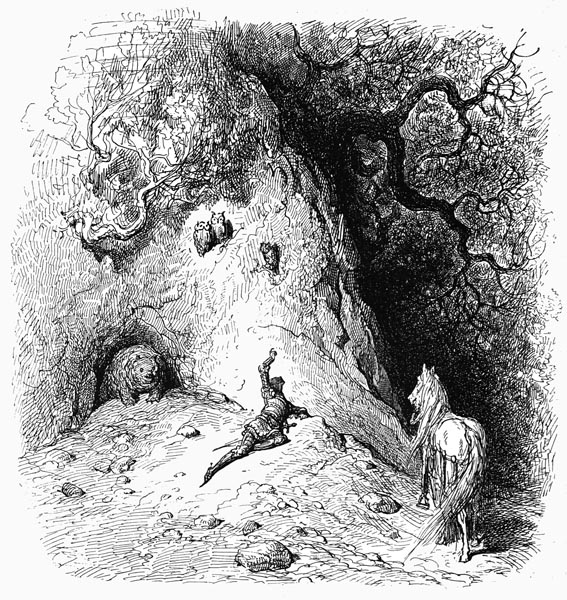

- Canto XXVII: 85-93: Marfisa seizes Brunello and issues a challenge

- Canto XXVII: 94-98: Agramante is persuaded not to respond

- Canto XXVII: 99-101: Discord rejoices

- Canto XXVII: 102-108: Agramante seeks to resolve the first quarrel

- Canto XXVII: 109-111: Rodomonte departs the camp

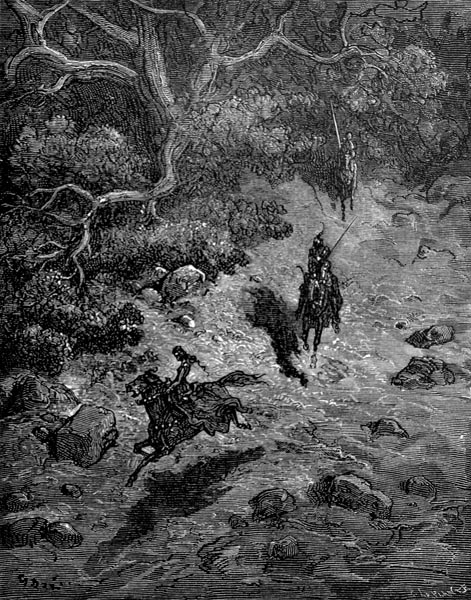

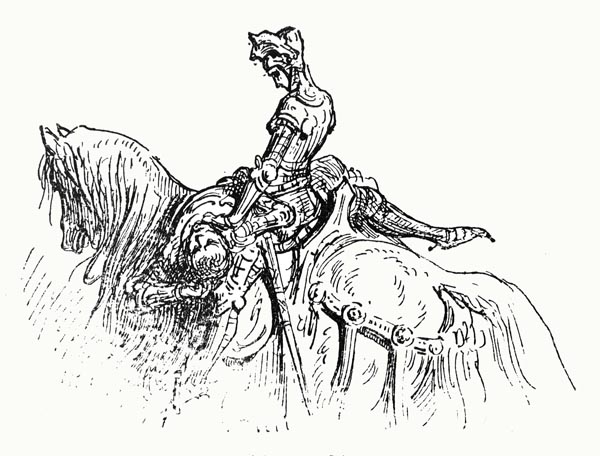

- Canto XXVII: 112-116: He is followed by Sacripante

- Canto XXVII: 117-121: Rodomonte’s lament

- Canto XXVII: 122-124: Ariosto’s hope and prayer

- Canto XXVII: 125-129: Rodomonte reaches the Saône

- Canto XXVII: 130-136: And is lodged at an inn

- Canto XXVII: 137-140: Whose landlord offers to tell a tale

Canto XXVII: 1-4: Unforeseen consequences

Many a woman’s best judgement is rather

Born of intuition than conscious thought,

Her own unique gift midst all the other

Blessings that the heavens to her have brought;

While men, in general, need the aid of sober

Reflection, or midst the shoals are caught,

Their judgement ill, unless they ruminate

Awhile, and labour hard to concentrate.

Malagigi’s seemed good, and yet was not,

Although, as I’ve said, from dreadful danger

He’d rescued Ricciardetto, whose ill lot

Was to meet Rodomonte, and encounter

Mandricardo. By conjuring, on the spot,

That demon, he’d sent them chasing after

Doralice; yet never dreamed the charm

Might to the Christian forces bring harm.

Had he but time for a moment’s thought,

He might have granted his young cousin aid,

Without his doing harm to those who fought

For Charlemagne, and greater sense displayed.

He could equally have ordered, as he ought,

The demon in the steed, that e’er obeyed,

To bear the lady so far, west or east,

That France would hear no more of them, at least.

Thus, the warriors, following as she fled,

Might elsewhere than to Paris have been sent,

But, to ruin, inadvertently, it led,

All through Malagigi’s reckless intent;

For Malice, whose great hunger’s ever fed

By blood and fire, and slaughter, was content,

Exiled from the heavens, to make her way

To Charlemagne’s host, bringing great dismay.

Canto XXVII: 5-6: Rodomonte and Mandricardo pursue Doralice to Paris

The palfrey, with the demon there inside,

Led fair Doralice not so far astray,

That she was halted by some ditch, yawning wide,

River, wood, marsh, or cliff, along the way.

Through the English, and French lines they did glide,

And the rest of the Christian array,

And the steed never stopped till it bore her

To the King of Granada, her father.

For a portion of that day, Rodomonte,

With Mandricardo, pursued her apace,

Their eyes fixed on her back, though, finally,

She was lost to sight; yet, hot upon the trace,

Rode those warriors, like hounds running free

Hunting some hare, or roebuck, in the chase,

Nor did they cease till they the news did gain

That she was safe with her father again.

Canto XXVII: 7-12: Rinaldo returns there still seeking Angelica

Guard yourself, Charlemagne for upon you

Comes such a storm I see no help at hand,

For not only these, but Gradasso too,

And Sacripante, heed the king’s command;

While Fortune, who would probe your strength anew,

Has drawn away those twin lights that did stand

At your side, e’er shedding wisdom and light;

Thus, you are blinded, midst the dark of night.

I speak of Orlando and Rinaldo,

Of whom the one is in a maddened frenzy,

And naked o’er the hills and plains doth go,

Neath sun and rain, in cold or heat, wildly,

While the other, likewise, wanders to and fro,

Nigh lost to you, when you need him greatly.

He, failing to locate Angelica,

Had left Paris, swiftly, in search of her.

By the cunning old enchanter deceived

(As from an early canto you should know),

Deluded by a phantom, he believed

Angelica had fled with Orlando,

And hence by bitter jealousy aggrieved,

More than any lover yet, he did go

To fair Paris, where appearing at court

He was sent to Britain, his quest cut short.

Then the field won, where he had the honour

Of inspiring the siege gainst Agramante,

He’d returned to Paris, still searching for her,

Through every fort, and tower, and nunnery;

And, save she were sealed in bricks and mortar,

That restless lover had surely found her.

Yet finding her not, nor yet Orlando,

He’d gone forth, again, to wander to and fro.

Fearful that in Brava, or Anglante,

Orlando enjoyed her, in joyful play,

Up and down, he journeyed, joylessly,

Nor found her, here or there, by night or day.

He’d then returned to Paris, thoughtfully,

Deeming that in a while he might waylay

The Count, who could not simply roam at will,

Beyond the walls, bound by stern duty still.

Once there, he’d rested but a day or two,

And, finding that Orlando came not there,

To Brava and Anglante had gone, anew,

Seeking news of the knight and lady fair;

And thus, at noon and midnight, would pursue

His dream, in light and darkness, nor did spare

His steed, but full two hundred times had run

That same round, by the light of moon and sun.

Canto XXVII: 13-16: The warriors bring aid to the Moorish army

But the ancient adversary, through whom

Eve raised her hand to the forbidden fruit,

Turned livid eyes on Charlemagne once more,

While Rinaldo was far upon his route,

And, seeing what great harm he might ensure

Among the Christian forces, in pursuit

Of their doom, led there, to the Saracen

Camp, their finest warriors, maid and men.

Those kings, Sacripante and Gradasso,

He’d joined in company, that very day

When from Atlante’s mansion they did go,

And then had set them swiftly on their way,

To aid the Moors, and strike many a blow

Against this Charlemagne and his array.

Ever, through unknown lands, he was their guide,

And smoothed their path to Agramante’s side.

To another fiend from Hell he’d given

The task of conducting Mandricardo,

And Rodomonte, to where the demon

Had carried Doralice, beyond the foe;

And then he had sent a third to summon,

Lest their hands be idle, Ruggiero

And Marfisa, guiding them more slowly,

Such that the pair had appeared but lately.

Half an hour at least behind the other two

He’d kept Marfisa and Ruggiero,

Because the Dark Angel who would pursue

The final ruin of the Christian foe,

Ensured no more delay could now ensue

From their dispute with Mandricardo

And King Rodomonte, which it well might

Have done, if that bold pair had met their sight.

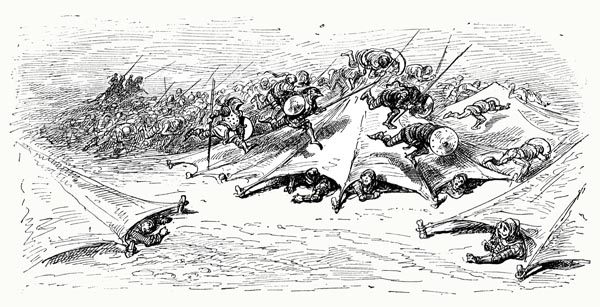

Canto XXVII: 17-19: The first four arrivals launch a surprise attack

The first four to arrive viewed, together,

The camps of the besieged and besieger,

The field of banners in the wind all a-flutter,

And there took counsel with one another.

The result of their discussions as to whether

To press on, and grant Agramante succour,

Despite the seeming strength of Charlemagne,

Was that sudden advantage they might gain.

Keeping close, they spurred across the plain,

To where the Christians were closely packed;

Crying, as they rode: ‘Africa, and Spain!’

Thus, turning mere suspicion to bold fact,

Among their foes, who must now maintain

The call to arms; but caught there in the act

Of arming, e’en the rear-guard felt the blow,

That not only were attacked, but routed so.

Amidst the tumult, the Christian army

Was confounded, though how they scarcely knew,

Thinking it some insult, treacherously

Wrought by the Swiss or Gascons; midst the hue

And cry, confused, they gathered swiftly

To each nation’s banners, forming up anew,

Here to the drum, and there the trumpet’s cry,

Echoing, loudly, from the earth and sky.

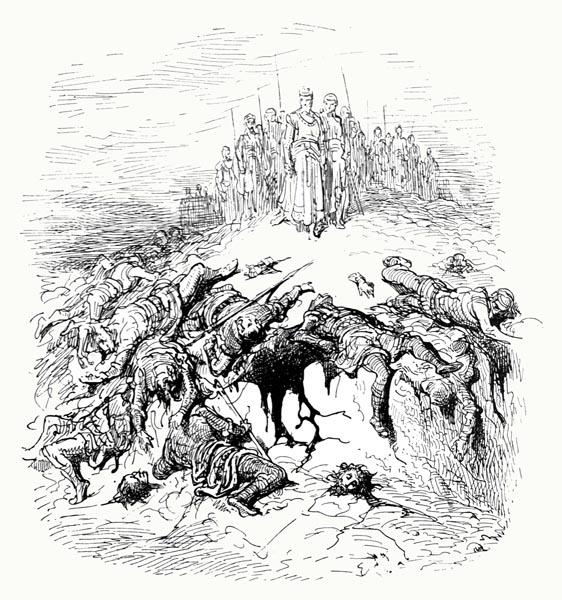

Canto XXVII: 20-22: Charlemagne surveys the damage

Save for his helmet, Charlemagne was armed,

With his paladins about him, and sought

To know what it was that had so alarmed

His brave squadrons, and havoc midst them wrought.

He threatened those that tried to flee, unharmed,

Though many a fugitive had, briefly, fought,

For bloodied faces, chests, arms, hands, he saw,

And heads and throats, the evil gifts of war.

Advancing, he viewed many on the ground,

Or rather weltering in a crimson lake,

So that, in their own blood, the living drowned;

No surgeon or magician such could wake.

Torsos, devoid of heads, lay all around,

And legs and arms, that none could now remake;

And cruel slaughter there, from first to last

Of the encampments, witnessed as he passed.

Where the band of warriors had sped by,

(Each of them worthy of eternal fame)

A lengthy wake, of corpses, met his eye,

A record of the exploits of those same.

At that cruel slaughter he heaved a sigh,

Filled with wonder, and anger, and disdain.

So, one who has felt the lightning’s force

Strike his ruined house, might chart its course.

Canto XXVII: 23-28: Ruggiero and Marfisa reach Agramante’s camp

This sudden aid, employed amidst the foe,

Had not yet reached Agramante’s army,

When, from another side, bold Ruggiero

And Marfisa, approached most suddenly,

Who, once they had cast their gaze to and fro,

And made a survey, however briefly,

Of the swiftest way to afford him succour,

Rode thence, to defend his life and honour.

When, by the gunner, the mine’s fuse is lit,

So swiftly through the powder will the fire

Run its course, that the eye scarce follows it,

Astounded by the speed it will acquire,

While ruin descends where the mine has hit,

As walls of stone are razed, and men expire.

So, Ruggiero and Marfisa sped

To battle, leaving but a line of dead.

Forward, and sideways, swept each sharpened blade,

Severing arms, and heads, and shoulders too,

Where’er the Christian ranks the pair delayed,

Too slow to move, as they swept through that crew.

Whoe’er has seen the trees by tempest swayed,

Midst hill or valley, while it passes through,

Leaving the rest untouched, may conceive

How those two the enemy ranks did cleave.

Many, that feared Rodomonte’s fury,

And that of the other furious three,

And thanked God He’d seen fit, in His mercy,

To grant them legs and feet on which to flee,

Now found themselves but mocked perversely;

Marfisa and Ruggiero, they could see

Before them and, whether they stood or ran,

None could escape, but perished to a man.

For whoe’er dodged the one, faced the other,

And paid the penalty in flesh and bone.

So, do fox cubs die, beside their mother,

In the hounds’ jaws, when she and they have flown

The den, forced by blows to break their cover;

For, unearthed, when fire and smoke were sown

Through all their ancient run beneath the ground,

Yet another form of death the creatures found.

Marfisa and Ruggiero, by and by,

Within the Saracen camp, took shelter,

Where while raising their gaze towards the sky

All gave thanks for their successful venture.

Indeed, the humblest Moor might now defy

A hundred Christians; he much the braver!

And so, it was agreed they’d, once again,

Set forth to drench with blood the open plain.

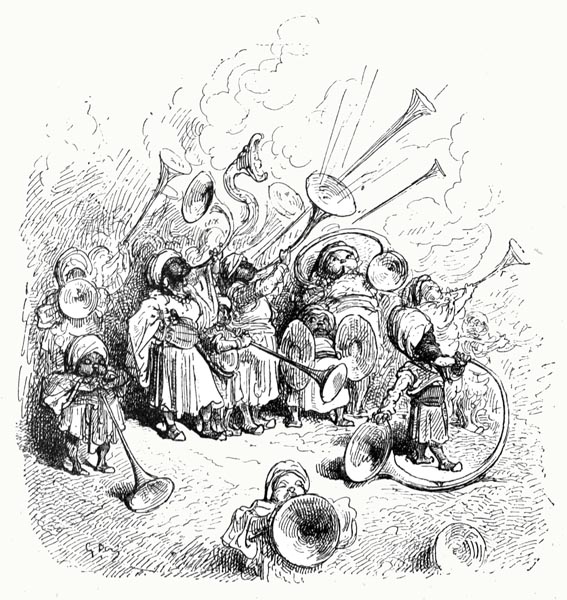

Canto XXVII: 29-33: The Christians retreat behind the walls of Paris

Trumpets, horns, and Moorish timpani

Filled the sky, with a formidable sound.

While banners in the wind fluttered gently,

Casting flickering shadows on the ground.

On the other side Charlemagne’s army,

With the Bretons and Germans could be found,

Those men of England, France and Italy;

Fierce war now was waged most bitterly.

The might of the furious Rodomonte,

With that of the Tartar, Mandricardo,

And that of Ruggiero, of virtue, truly,

The fountain, and of renowned Gradasso,

And Marfisa, that intrepid lady,

With that of King Sacripante also,

Made Charlemagne upon Saint Denis call,

Then Saint John, then seek Paris, and its wall.

The wondrous skills and the martial ardour,

Of Marfisa, displayed by every knight,

Was not, I must claim, of such a nature

As to be shown, or e’en conceived aright.

The number that they put to the slaughter,

You must imagine, and how, in that fight,

Charlemagne felt the blow. Add to these same,

Ferrau, and many a Moor known to fame.

Many a Christian drowned in the Seine,

(The bridges could not support so many)

And longed for Icarus’ fine wings, in vain,

With death before, and behind them, surely.

Save Oliviero, and Uggieri the Dane,

The paladins now faced captivity;

Oliviero’s shoulder ached and bled,

Uggieri was bruised about the head.

And if, like Rinaldo and Orlando,

Brandimarte had been lost from the game,

Charlemagne had been forced to forego

His Paris, or be scorched in the flame.

Where Brandimarte could hold, he did so,

Where he could not, he yielded the same.

And thus, Fortune smiled on Agramante,

While Charlemagne was penned in the city.

Canto XXVII: 34-36: Saint Michael hastens to intervene

The laments of the old rose to the sky

With the cries of the orphan, and the widow,

Reaching Saint Michael’s blessed realm, on high,

Set far beyond the troubled earth below,

And brought him news of how men fight and die,

And how their flesh yields to the ravening crow.

Those faithful of England, Germany, France,

Mere corpses, filled the field of that advance.

It reddened, the blessed Archangel’s face;

For it seemed he’d executed the command

Of his lord most poorly, feeling his disgrace,

Betrayed by faithless Discord, all unplanned.

He’d been told to foster strife amidst the race

Of Saracens, such was the Lord’s demand,

Yet the opposite he had achieved, I ween,

To those eyes that now gazed upon the scene.

Like a faithful servant (weaker in memory

Than loyalty, who finds he has forgot

That which to his heart and mind should be

As precious as his life and soul, whose lot

Is now to mend the error, speedily,

Nor see his lord before) he might not

Ascend to God, the Lord of Creation,

Till he’d first fulfilled his obligation.

Canto XXVII: 37-39: He sends Discord to rectify the problem

Once more, to the monastery, he flew

Where he’d seen Discord, and found her there,

Seated in chapter, as they chose anew

Their officers, a desperate affair,

In which the monks hurled, a delight to view,

At each other’s heads, their books of prayer.

Gripping her by her hair, mercilessly,

The angel kicked and struck her, endlessly.

Then he broke his cross’s handle on her head,

With which he belaboured her arms and back.

She cried aloud, as if to wake the dead,

And embraced his knees, stunned by the attack.

Yet he ceased not until, at last, she fled

Before him to the Moorish camp. A thwack

He gave her, crying: ‘I’ve yet more in store,

If I find you’ve quit the task, I sent you for.’

Though her head, and back, and arms, were aching,

For fear of his attacking her again,

(Since his anger there was no mistaking,

And a further beating meant further pain)

She ran to her furnace and, there, raking

The coals, and adding fuel, set to strain

At the bellows, thus lighting many a fire,

To kindle, in many a heart, a blaze of ire.

Canto XXVII: 40-44: The warriors’ quarrels are renewed

Rodomonte, she inflamed, Ruggiero,

And Mandricardo, who went together

To King Agramante (for since the foe

Had retreated, they now held the upper

Hand) and told him the tale, that he might know

The seed of their dissension, and its bitter

Fruit, and to his judgement they appealed

As to which of them should first take the field.

Marfisa put her case to him, also,

Saying she wished to complete the fight,

Which she’d begun with Mandricardo,

Provoked to commence it by the knight,

Nor would accept delay in doing so,

Not a day, not an hour, for twas her right;

To be the first to joust, she demanded,

With the Tartar, if the king commanded.

No less did Rodomonte seek first place,

Wishing to end the fight with his rival,

Which they’d interrupted that they might face

The foe, bringing aid by their arrival.

While Ruggiero chose to speak a space,

And said, for far too long, he’d suffered mortal

Aggravation from the theft of his steed,

While Rodomonte sought delay indeed.

Then the Tartar added more complexity,

Complaining that Ruggiero had no right

To the eagle emblem; in his fury,

So filled with bitter anger and with spite,

That he cried, if the rest would so agree,

They might all engage together in fight,

Which indeed the others were prepared to do,

If that had been King Agramante’s view.

Agramante, with prayer, and kingly speech,

Would have forged a truce twixt them if he could,

But since they all seemed deaf, beyond the reach

Of reason, and required not peace but blood,

He decided that the best that he could preach

Was that they fought in order, for their good;

And, to that end, he decided, on the spot,

That they should each take to the field by lot.

Canto XXVII: 45-48: Lots are drawn and a place assigned

Four lots were thus prepared, and on the one

‘Rodomonte gainst Mandricardo’ was writ.

‘Mandricardo gainst Ruggiero’ once done,

‘Ruggiero gainst Rodomonte’, joined it,

Then ‘Mandricardo gainst Marfisa’. None

Left, one was drawn, to the benefit,

Of Rodomonte and the Tartar king,

As Fortune now wished, that fickle being.

‘Mandricardo gainst Ruggiero’ showed then,

‘Ruggiero gainst Rodomonte’ still third,

While ‘Mandricardo gainst Marfisa’ again

Was drawn the last, at which the maid demurred.

Nor was Ruggiero happier that the men

Before him, when the first fight occurred,

Were like to conclude in such a manner

As to leave naught for him, or Marfisa.

Not far from Paris’ walls there was a place

That measured a mile or so, all around;

An embankment held it in its embrace,

Like a theatre that doth the stage surround.

A castle, once, that site, it seems, did grace

Siege and fire had levelled it to the ground;

The like a citizen of Parma may survey,

If from thence to Borgo they make their way.

Upon that site the lists were soon displayed

A square of turf sufficient for their need,

The ground enclosed by a low palisade,

With two gates, as is commonly decreed.

The warriors seeking not to be delayed

Had the day for the joust at once agreed,

And now behind the fence, on either side

Facing those gates, pavilions were descried.

Canto XXVII: 49-53: Mandricardo is angered

The tent on the west housed Rodomonte,

And there his serpent-hide was soon clad

In steel, by Ferrau and Sacripante;

His giant members they adorned as he bade.

Falsiron and Gradasso made entry

To that on the east and, there, were glad

To dress Mandricardo in the armour

That had once been worn by Trojan Hector.

On an ample throne sat King Agramante,

Marsilius beside him, King of Spain,

Then Stordilano, and the heads of the army

Most revered, among the host, upon that plain.

Whoe’er could climb a nearby hill or tree,

Was happy such a noble view to gain.

Great was the crowd, on every side arrayed,

A wave of folk against that fencing swayed.

And there, beside the Queen of fair Castile,

Sat queens, princesses, noble ladies too,

From Aragon, Granada, and Seville,

And from where Atlas’ Pillars one might view.

Stordilano’s daughter every eye did steal;

Doralice wore rich robes, though of the two,

One crimson, and one green, that she bore

The first looked worn, behind and before.

In a short and skimpy dress was Marfisa,

Such as was suited to a warrior-maid,

The river Terme might, in that manner,

Have seen Hippolyte and her troop arrayed.

Now, the king’s herald, midst the clamour,

Who the royal coat of arms there displayed,

Proclaimed that none must side, twas their duty,

In their deeds or words, with either party.

The dense throng of folk waiting for the fight,

Complained at the lateness of the duo,

(Each of the combatants a famous knight)

When from the tent of bold Mandricardo,

Cries and shouts were heard, and not of delight.

Twas the King of Sericane, Gradasso,

And the fierce Tartar, who’d stirred, at a word,

The tumult, shouts, and cries that they heard.

Canto XXVII: 54-58: Gradasso lays claim to Orlando’s sword

Having clad in armour the Tartar king,

Gradasso had approached to gird a sword

About the pagan, the blade revealing

Which was Orlando’s (that he’d flung abroad).

Twas then Gradasso saw the engraving,

‘Durindana’, with the arms of that lord

Young Orlando had slain, brave Almonte,

Beside a crystal fount, in Aspramonte.

At once, he knew it for the famous blade

That Anglante’s count, bold Orlando, bore,

For which, the finest fleet had anchor weighed,

That had ever sailed from Levantine shore.

Castile, they had conquered, and France dismayed,

Beneath his flag, a few short years before,

Nor could he now imagine how that sword

Had been acquired, thus, by the Tartar lord.

He asked him where and when the sword was won,

And if by force or not. Mandricardo,

Lied, and said fierce battle he had done

For that illustrious blade with Orlando,

Who’d feigned madness, neath the midday sun,

Seeking to conceal his cowardice so,

‘For he knew,’ he added, ‘that I’d afford

Him endless trouble till I had the sword.’

And said that he’d behaved like the beaver

That tears out its own castor sacs whene’er

Tis closely pursued by the fierce hunter,

For the castoreum secreted there.

Gradasso, who none of this would suffer,

Cried that he alone the blade should bear:

‘Tis owed to me, for me alone tis meant,

For all the effort, gold and lives I’ve spent.

Seek out some other blade you might employ;

That this is mine, should not be news to you.

Whether the Count sanity may enjoy

Or madness yet, tis mine, this blade you view.

That you fought for it is some mere ploy;

You found it by the wayside; tis my due.

My sharp scimitar will uphold my cause,

Here, in the lists, according to our laws.

Canto XXVII: 59-63: Mandricardo seizes it from him

You must retain the blade ere you can fight

Gainst Rodomonte with it; as you know,

Tis an ancient custom that every knight

Must earn his sword, ere he may meet the foe.’

‘No sweeter sounds could on my ear alight,’

Replied the Tartar, proudly, ‘here below,

Than those that summon me to the field,

Yet Rodomonte his consent must yield.

Be you the first, and let Rodomonte

Be the second that I shall attend to,

And doubt you not that I’m good and ready

To reply to every other after you.’

But Ruggiero called out: ‘Not so swiftly

Would you now set aside the lots we drew;

Either Rodomonte first you must meet

Or fight me, and their order thus defeat.

If Gradasso’s reasoning shall prevail,

And a knight must win the arms he’d wield,

Your claim to show the eagle can but fail,

Unless you first can bear away my shield.

But since I’ve deemed all that of no avail,

I say none here should their placement yield,

And mine should be the second battle fought,

When Rodomonte first his cause has brought.

Yet, should you disturb the order of the day,

Then I’ll confuse the matter utterly,

For I’ll not yield the eagle I display,

Unless you then can wrest my shield from me!’

‘Were you both Mars, desirous of affray,’

Mandricardo now replied, wrathfully,

‘Neither one nor the other might deny

My title to the shield or sword, say I!’

Then, possessed by anger, he upped and flew,

With clenched fist, at the amazed Gradasso.

He lost the sword, in what did then ensue,

For the hilt slipped his grasp, at that fierce blow.

Not thinking Mandricardo would pursue

So mad and spiteful a course, nor was so

Foolish as to try, no defence he’d made,

And so, he found himself robbed of the blade.

Canto XXVII: 64-68: Agramante temporarily resolves the dispute

Thus scorned, righteous hurt and anger

Flared o’er Gradasso’s face, his cheeks aflame,

While the pain that he suffered was greater,

In that twas done in public, to his shame.

He now stepped back, to draw his scimitar,

Bent on revenge, and to defend his name;

While Mandricardo, trusting in his skill,

Sought Ruggiero, if twas his will.

‘Come on, in arms, together!’ so he cried,

‘Let Rodomonte be the third I’ll fight.

Come Africa and Spain, the world, allied

In force, I’ll ne’er turn my back in flight.

And fearing none, those warriors he defied.

Whirling Almonte’s blade, the Tartar knight,

Grasped his shield, a formidable foe,

To meet with Ruggiero and Gradasso.

‘Leave this task to me,’ Gradasso said,

‘And to this madman I shall bring the cure.’

‘Not so,’ Ruggiero cried, ‘tis I instead

That claim the right, for I deserve it more.’

‘Retreat!’ ‘Stand back!’ The counter-claims now sped

Between the two, yet neither would withdraw.

And thus began a feud between the three,

And strange the issue there, had not many

Well-nigh bought themselves a deal of pain,

By intervening, though with scant wisdom,

And learnt, to their sad cost, what men obtain

That to the aid of warring madmen come.

For all the world had sought peace there, in vain,

If Marsilio had not struck them dumb,

And Agramante, whose sudden presence

Subdued them now to awe and reverence.

Agramante demanded that they reveal

The cause of this fresh and ardent quarrel,

And, once known, to Gradasso made appeal.

He should yield Hector’s blade, for a little,

To Mandricardo, who required the steel

To face Rodomonte in fierce battle.

Twas for but a day, till they were done,

And had resolved the matter, one on one.

Canto XXVII: 69-74: Meanwhile Sacripante lays claim to Frontino

While Agramante pacified the three,

Reasoning with one and then another,

A second pair were heard to disagree,

In the nearby tent, arguing together.

Sacripante, as I’ve said previously,

Had helped Rodomonte with his armour,

And he and bold Ferrau had clad the king

In plate of his forebear Nimrod’s making,

And then had gone to where spraying spume

His horse champed at the bit; of Frontino

I now speak, that valiant charger, for whom

Longed yet, in indignation, Ruggiero.

Sacripante who thus acted as groom

For the steed, and had led it to and fro,

Had marked the shoes, and trappings that it bore,

And thought that he had seen the like before.

Then, in gazing, more closely, at the steed,

His doubt dispelled, he recognised the creature,

And surmised it was Frontino indeed,

Not merely by the form, but its proud nature.

A horse that he’d held dear he now did lead,

One, in a thousand feuds born to feature,

And one whose capture from him long ago,

Leaving him on foot, had pained him so.

Brunello had seized it that same day,

Before Albracca, when he’d taken

Angelica’s ring, and snatched away

Orlando’s horn, his Balisarda stolen,

And Marfisa’s blade; he did convey

Balisarda to brave Ruggiero, then,

And with the sword, this noble steed, also,

That Ruggiero had renamed Frontino.

Once certain that he was not in error,

He turned to Rodomonte, and cried:

‘This horse was seized from me in Albracca!

The steed is mine, as may be verified

By many that know its rightful owner;

Yet since those folk are scattered far and wide,

If any should deny it, I’ll maintain

The truth, sword in hand, and make all plain.

Yet I’m content, since we for many a day

Have been companions, to lend the steed

To you, until the morrow, so you may

Perform the fight, at the hour now agreed,

Though on the understanding, as I say,

That the horse is mine, lent to you at need,

Else hope not to mount him for the fight,

Unless you first win him, from me, outright.’

Canto XXVII: 75-79: He and Rodomonte spar together

Rodomonte, possessed of greater pride

Than all the finest knights put together,

His strength and courage, not to be denied,

Such as ancient stories rarely offer,

To the kindly King Sacripante cried,

‘If such words had come from any other,

He’d have been dealt such bitter fruit

Twere better if from birth he’d proven mute.

Yet, for the comradeship that we have known,

And for the action we have seen together,

I’ll offer the respect that should be shown,

And merely suggest you take some other

Path, for now, and adopt some other tone,

Till you have witnessed the fight; thereafter,

When I’ve made of him a brave example,

You’ll cry: ‘Keep the courser, and the saddle!’

‘Tis your form of courtesy to be rude?’

Sacripante asked, in anger and disdain.

‘I’ll needs be clear, given your attitude:

Forgo possession of the steed! Is that plain?

For I’ll defend my right, with fortitude,

As long as my brave sword I might maintain,

And I’d battle for it then, tooth and nail,

If all other forms of weapon were to fail.’

From dispute they progressed to mockery,

Then threats and cries, and thence to fighting,

Their anger blazing higher, more quickly,

Than fire amidst the straw, swiftly kindling.

Rodomonte had his breastplate, while sadly

Sacripante lacked mail, or steel cladding,

Yet seemed (so well he fenced, that nimble lord)

To be as well protected by his sword.

No greater were the strength and bravery

(Both immense) that Rodomonte displayed,

Than were the awareness and dexterity

That Sacripante summoned to his aid.

No grindstone was e’er rotated faster

By the mill-wheel, ere the grain is weighed,

Than Sacripante’s circling hands and feet

Moved at his need, his actions trim and neat.

Canto XXVII: 80-84: Agramante again seeks the cause of dispute

But then Ferrau, and bold Serpentino,

Drew their gleaming swords, parting the pair,

With Isolier, and Grandonio,

And the other Moorish lords who were there.

It was the sound of sword blow upon blow,

And the shouts, that gave news of the affair

To the king, striving to calm Ruggiero,

Gradasso, likewise, and Mandricardo.

A fresh report came, then, to Agramante

Of the quarrel, regarding the said steed,

Twixt Rodomonte and Sacripante,

That seemed bent now on war, as all agreed.

The king, disturbed by their great enmity,

Said to Marsilio: ‘Ensure no deed

Renews the fight here, or breeds another,

While I now seek to resolve the other.’

Rodomonte, on seeing the king appear,

Reined in his wrath, and then stepped back a pace,

While Sacripante, with like awe and fear,

Retreated too, before the king’s stern face.

He asked to know the cause, as yet unclear,

(Grave his voice, imbued with regal grace)

Seeking, once the matter was made plain,

To reconcile the pair, yet all in vain.

Sacripante demanded Rodomonte

Return the steed, and ride it no longer.

Unless the latter requested, humbly,

That for a day he lent him the charger,

To which Rodomonte answered proudly,

‘Neither you nor heaven, in this matter,

Will see a thing that I have won by force,

Deemed another’s, be it sword or horse.’

The king asked Sacripante to explain

What right he thought he had to the steed,

And how it had been taken; so, with pain

And reddening cheeks, he told of the deed,

Whereby the thief the animal did gain,

Having surprised him, as ill fate decreed,

Deep in thought, his saddle pinned on high

By four spears, the horse stolen, on the sly.

Canto XXVII: 85-93: Marfisa seizes Brunello and issues a challenge

Marfisa, also drawn to the shouting,

When she heard about the theft of the charger,

Displayed a troubled face, remembering

How her sword had been lost at Albracca,

For she recognised the horse that, fleeing

From her, had seemed winged, and further

She recalled Sacripante, she felt sure,

Whom she had failed to recognise before.

The others there, who’d often heard Brunello

Boast of the matter, turned against the thief,

And signalled that he was the very fellow

That had stolen it, such was their belief.

Marfisa, who had thought it might be so,

From all that had been said, now, in brief,

Was convinced, since those about her agreed,

That Brunello it was who’d done the deed,

And that, for the crime, the man was worthy

Of being hanged by the neck, yet to the throne

Of Tingitano he’d been raised by Agramante,

(An ill choice) and held that realm for his own.

This again made Marfisa more than angry,

(For the seeds of vengeance had long been sown)

Set to punish him for all the shame and scorn

She’d incurred when the sword from her was borne.

She had a squire set her helm on her head,

Being clad already in her armour;

Nor do I find that steel was ever shed

More than ten times all her days for, ever,

Was she dressed so (such the life she led)

Since she had first become a warrior.

Then, helmeted, she sought out Brunello

Amidst the high seats, in the loftiest row.

When she reached him, she gripped him by the chest,

And then raised the thief high above the ground,

As an eagle will a pullet’s course arrest,

With its fierce talons, while the squawks resound,

And carried him where the king, and the rest

Of his monarchs and lords could yet be found,

While Brunello, moaned and wept, endlessly,

And, midst his cries and groans, begged for mercy.

Amidst the shouts and noise, with which the field

Was equally alive, Brunello’s pleas

For pity and for aid, so loudly pealed,

That a crowd gathered round, to mock and tease,

(His great cowardice being thus revealed)

As bold Marfisa carried him with ease

To the African king, then, in her anger,

Addressed him proudly, and in this manner:

‘I wish to hang this thief, your vassal, high,

And with this hand suspend him by the throat,

For, the day he stole that horse, tis no lie,

He stole my sword as well, let all here note.

And, if any would the facts of it deny,

Let him stand forth, and this man’s lies promote,

For, in your royal presence, I’ll sustain

My rights, and e’er the truth will I maintain.

Yet if some here would seek to accuse me,

And say I take advantage of a quarrel,

While the finest warriors in this army

Are committed to meet, and so do battle,

I’ll wait to hang him for his villainy,

For three whole days, unless and until

One comes, or sends another in his stead;

For failing that I’ll see the fellow dead.

From here to that tower, three leagues away,

That overlooks the little wood below,

With but one servant, and a maid, this day,

And with no other company, I go.

And, to any that would rescue him, I say:

Visit the tower, for you I seek to know.’

So, she spoke, and having done so, she went;

And, with that, they were forced to rest content.

Canto XXVII: 94-98: Agramante is persuaded not to respond

She set Brunello on the steed before her,

While still grasping the villain by his hair,

As he cried to all about for succour

And ever wept and moaned in his despair.

Meanwhile Agramante, troubled further,

Saw no end to wild affair upon affair,

While he grieved to see Marfisa convey

His vassal to the tower, in that vile way.

Not that he prized or cared for the fellow,

For many a time he’d aroused his disdain,

And at heart he’d longed to see him hanged so,

Since the ring he’d lost, and to little gain.

But, in this thing, dishonour might follow,

So that his face was reddened, once again.

He would follow the maid he thought, at speed,

And avenge the slight, ere she did the deed.

But King Sobrino, who was yet present,

Attempted to dissuade him from the quest;

Saying twas ill if a king should consent

To such as demeaned him, and twere best,

(Since he could, with impunity, prevent

The execution, and e’en the maid arrest)

To avoid the shame, for there was scant honour

In defeating the maid, though he must conquer.

Great was the risk and small was the reward,

In any battle to be fought with the maid,

While better counsel he could now afford,

Which was to leave Brunello, and not aid

The fellow; though the latter might accord

With his majesty’s powers, he was afraid

That the slight nod, which was all it needed,

Meant that justice might well be impeded.

‘You can send to Marfisa, now,’ he said,

‘And request her to leave justice to you,

With a promise to her that he’ll be led

To the gallows, and her wish so pursue;

Or, should the maid refuse, let her, instead,

Perform that same deed, if all this be true.

Better her friendship, such is my belief,

Though she hangs Brunello, and every thief.’

Canto XXVII: 99-101: Discord rejoices

Agramante conceded, willingly,

To Sobrino’s calmer, wiser counsel,

And let Marfisa retire, in safety,

Nor did he seek, otherwise, to compel

The maid to aught, but suffered her, bravely,

Letting her in that lonely tower dwell,

So that he might quench the greater strife,

And his whole court pursue a calmer life.

Mad Discord smiled at this, with little fear

That peace or a truce might be forthcoming,

But scoured all about the field, far and near,

Nor could she find a pleasanter dwelling.

Pride leapt and gambolled with her peer,

And to the flames she added fresh kindling,

And cried aloud, so Saint Michael might know,

That victory had been gained on Earth below.

All Paris trembled, turbid ran the Seine,

At that loud voice, that fierce inhuman cry;

The Ardennes Forest heard it sound again,

Wild creatures found their dens, birds fled the sky;

The Alps, the Cevennes all heard it, plain,

O’er Arles, and Blois and Rouen, it did fly;

Rhône and Saône, Garonne and Rhine, east and west,

While mothers hugged their children to their breast.

Canto XXVII: 102-108: Agramante seeks to resolve the first quarrel

The five male knights had each resolved to be

The first to conclude their duels outright,

And yet were involved so intricately,

Not Apollo himself could see the light.

To untie the knot, King Agramante

Began with what had caused the first sad fight

(Fair Doralice, Stordilano’s daughter!)

Between Rodomonte and the Tartar.

Agramante, who sought a firm accord,

Went here and there, from one to the other,

To and fro, between each angry lord,

Now a just king, now a faithful brother.

But when he found that neither would afford

Grounds for peace, each seeming deaf as ever,

Refusing to relinquish the lady,

The reason for strife, to their enemy,

He appealed at last to a course that might

Serve to satisfy the lovers: that the maid

Should now be married to whichever knight

She preferred, and with that decision made,

Naught must be done, and none must fight

To overturn it, with words, or lance, or blade.

Both of them were pleased with the compromise,

Both hoping to find favour in her eyes.

King Rodomonte who had, long before

That other, told her of his love, now thought

(Since she’d ever seemed his suit to favour,

As much as a chaste lady might, in short)

That once she passed judgment on the matter,

His case could not but weigh more in that court.

Nor was the king alone in his belief;

Such was agreed by every Moorish chief.

All knew what deeds he had wrought for her sake,

In jousting, and in tournament, and war,

Thus, regarding the judgment she must make,

Mandricardo seemed ill-matched gainst the Moor;

Yet he, who’d talked with her, and time did take

To woo her, when the earth its shadows wore,

Knew, thus, what grounds he had for confidence,

And smiled at the foolish crowd’s innocence.

Once they had ratified their agreement

Twixt the king’s hands, the valiant pair

To seek the lady’s final judgement went.

She lowered her gaze modestly, and there

To the Tartar gave her love and consent,

While Rodomonte could but stand and stare,

Then lower his own gaze, in deep dismay,

While the rest their sheer wonder did display.

But then the usual anger chased the hue

Of shame from his face; unjust he called

The judgment, and false, and gripped anew

The sword hilt in his hand, sadly galled,

And said, in the king’s hearing, the issue

Should be decided not by one enthralled,

Not by woman’s fickle choice, but the blade,

For oft where they should not her feelings strayed.

Canto XXVII: 109-111: Rodomonte departs the camp

Mandricardo again arose, and cried,

‘Let it be as you wish, then!’ Thus, it seemed

That a wide tract of ocean must be tried

Ere the ship made port as the king had schemed.

But he reproved Rodomonte, on his side,

For the quarrel was at an end, he deemed,

In vain could the conflict be maintained,

The sails had now been furled; the harbour gained.

Rodomonte, considering he had been

Doubly shamed, both by his sovereign lord,

Whom he revered, and his affection’s queen,

Deemed he was doomed to wander now abroad,

And thus, determined to depart that scene,

Taking two sergeants with him, out the horde,

Went from the cantonment that same day.

A sad and angry man, he took his way.

He left as a defeated bull might go,

Relinquishing the heifer to the victor,

That seeks the river, or the woods, in woe,

Or some barren shore, far from the pasture,

Nor ceases in sun or shade to bellow,

Still lost in his longing for the other.

So Rodomonte, parting from the maid,

Overcome by deep sorrow, widely strayed.

Canto XXVII: 112-116: He is followed by Sacripante

Ruggiero thought now to reclaim his steed,

Being already armed for that same quest,

But recalled Mandricardo, who’d agreed

To fight in strict order, as had the rest.

And so, he wheeled his horse, such was his creed,

So that he might the Tartar’s claim contest,

And then meet with Gradasso, thereafter,

To challenge his claim to Durindana.

To see Frontino vanish neath his eyes,

And yet do nothing, grieved our knight sorely,

Though his resolve was to pursue that prize,

Once he’d dealt with the other two, briefly.

But Sacripante was not bound likewise;

Naught stopped him from chasing Rodomonte.

Hence, being of no other aim possessed,

To o’er-take the Saracen was his quest.

He would have come upon him, were it not

That he now met with a strange adventure,

Which detained him till he’d almost forgot

His pursuit of both the steed and warrior.

By the Saône a maid, such was her ill lot,

Had slipped, and was drowning in the river,

And would have perished so, you may be sure,

Had he not plunged in, and brought her to shore.

When he would remount and seek the trail,

His steed would not wait but broke astray,

Nor could he capture it, and yet prevail,

Till he came upon it, nigh the close of day.

And caught at last, it proved of small avail,

For he had lost the hoofprints, and his way.

Two hundred miles he roved, o’er hill and plain,

Ere he found Rodomonte once again.

Where he found the Saracen, who then fought

And was overcome by Sacripante,

And lost the horse which the other sought,

I’ll not speak of now, for my first duty

Is to tell of the disdain, the charges brought

Gainst Doralice and Agramante,

By that knight, as the road he did cover,

And what he said of one, and the other.

Canto XXVII: 117-121: Rodomonte’s lament

The air was all aflame with burning sighs

Where’er the grieving Saracen now went,

While Echo, out of pity, sad replies

Repeated from the cliffs, as is her bent:

‘O feminine mind, in what fickle guise,

You stray, transformed in mood and intent,

Opposed to every form of loyalty!

The man that trusts in you, wretched is he!

Neither my endless service, nor my love,

That I, a thousand times and more, have shown,

Had the power to hold your heart from remove,

That changed so soon, and left me all alone;

Nor has love died, although, to you, I prove

Less than this Mandricardo, as you’ve shown;

Nor for all this can I find a reason,

Save this alone, that you are a woman.

For I think that God and Nature bore you,

O evil sex, as a weighty punishment

For man’s grave earthly sin, who, without you,

Had been far happier, and e’en content;

Much as the bear was wrought, the grey wolf too,

And that devil in the grass, the serpent;

Much as the wasp and flies, that buzz in air,

Or the weeds that mar the crop, everywhere.

Why has generous Nature not decreed

That man could be born without your aid?

As pear, apple sorb, can, without seed,

Be obtained by grafting? Yet, I’m afraid,

Nature cannot create the world men need,

Rather, I perceive that world betrayed,

For naming her, I see naught perfect can

Be wrought by Nature, for She’s a woman.

Yet, ladies, be not so proud or scornful

In proclaiming that man is born of you,

For the rose midst the thorns springs eternal,

And the lily out the slime gleams anew:

Importunate, arrogant, and spiteful,

Lacking love, loyalty, and wisdom too,

Unjust, ungrateful, reckless, cruel from birth,

You were formed to forever plague this Earth!’

Canto XXVII: 122-124: Ariosto’s hope and prayer

These complaints, and many another, I find,

The Saracen king yielded to the air,

Now, murmuring low to ease his troubled mind,

Now, in great cries that echoed everywhere,

Casting blame and reproach on womankind.

Yet in this the king, I deem, was wont to err,

Since for every evil maid to be found,

A hundred are thought goddesses, and sound.

Though I have loved many a maid, to date,

And I’ve found none faithful, not a one,

I lay the blame upon my sorry fate

That all have proved disloyal, neath the sun.

Many have been, and many are, of late,

Such as give no cause for a man to shun

Their presence, yet if there be one or two,

Of evil cast, I’ll form their prey, tis true!

Yet I’ll seek, so thoroughly, ere I die,

(Rather before my hair grows whiter still)

That one day, perchance, I may cast my eye

On one that will keep faith, despite her will.

And if that happens (for my hopes are high)

I pray the happy task I’ll yet fulfil

Of rendering her glorious, ere the close,

With tongue, and pen and ink, in verse and prose.

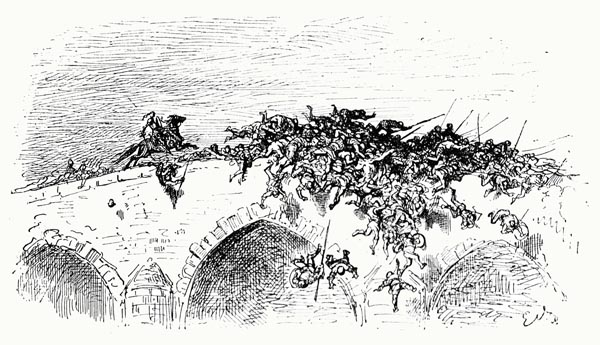

Canto XXVII: 125-129: Rodomonte reaches the Saône

The Saracen king felt no less disdain

For his sovereign than for the maiden,

Blaming one, then the other, for his pain,

And passing thereby the bounds of reason.

He wished to see such ill, such storms, maintain

Their assault against that monarch’s kingdom,

That every house in Africa might fall,

Nor stone rest yet on stone in standing wall,

While, thrust from his realm in grief and woe,

Agramante should live a wretched beggar,

And he himself might then his fealty show,

And restore him to his throne, thereafter,

And, thus, the fruits of loyalty bestow,

And make that sovereign see that twas better

To choose a true friend, whether wrong or right,

Though all the world against him should unite.

And now upon his monarch, now the lady,

He turned his troubled thought, as he passed by

Upon his way; he journeyed, restlessly,

Yet was neither weary, nor closed an eye.

(Nor did Frontino!) Two days later, he

Found himself upon the Saône for, thereby,

He might reach Provence, then sail from there

To his realm in Africa, his native lair.

The water was filled with many a boat,

The surface covered o’er from shore to shore,

Vessels from many a place there afloat,

To supply the host, and deficits restore,

For south of Paris every stream of note,

Was in the power of the advancing Moor,

From Aigues-Mortes, and the watery main,

O’er the land, to the west, as far as Spain.

The stores that were carried to dry land

Weighed down the carts, and beasts of burden,

Which were then despatched, on every hand,

Where no barge could reach, to many a region;

While oxen were seen, grazing, now un-spanned,

Brought from elsewhere, their sources legion;

Their drovers sleeping near the river-side,

Or in herdsmen’s huts, scattered far and wide.

Canto XXVII: 130-136: And is lodged at an inn

Rodomonte, since the light was fading fast,

Responded to an innkeeper’s request,

For the air filled with shadows as he passed,

To stay the night at his inn, as his guest.

His horse once stabled, he took his repast,

And wine, from Greece and Corsica, addressed,

For, a Moor in every other way, he drank

Of the forbidden beverage like a Frank.

The landlord, with good fare, and honest face,

Thought to pay Rodomonte honour,

Judging from his manner, full of grace,

That he was one renowned for his valour,

Yet one divorced from himself a space,

And as dull of heart as any man ever,

(For his thoughts dwelt upon his lost lady,

To his detriment) that sat there silently.

The host, more diligent in his good trade,

Than any e’er recorded in fair France,

(In that despite the fierce incursions made,

He’d kept his tavern whole, midst that advance)

His kin, that they might cheer the knight, displayed,

And ease his troubled countenance, perchance,

Yet not one of them dared smile, or say aught,

On finding he was mute, and lost in thought.

Far distant from himself, Rodomonte,

Wandered from one thought to another;

His gaze on the ground, quite melancholy,

So, none there could see his face; then, sighing,

After long silence, raised his head slowly,

As if he were roused from his dreaming,

And gathered himself and turned his eyes

On the host and the rest, in mild surprise.

And then, the silence broken, with a face

Less troubled, and a far calmer manner,

He asked the host, and others in that place,

If any had a wife, and those made answer

Who had, accordingly, and for a space

He was silent again, then he asked further

What belief as to her did each espouse:

Did he trust in her keeping to her vows?

And all, except the host, said they believed

Theirs was chaste, and good, without exception.

The host retorted: ‘Then you’re all deceived!

Every one of you but errs, in my opinion.

And your foolish belief, howe’er conceived,

Stands as witness to your loss of reason.

And in that he will concur, this noble knight,

Unless he would persuade us black is white!

For, as there is but one phoenix living

On this Earth, at any hour, only one,

So, tis said, there’s but one husband breathing,

That’s not betrayed by his wife, neath the sun.

Yet each believes he’s that happy being

And that he the solitary palm has won!

Though how can all achieve that blissful state,

If there’s but one appointed so by fate?

Canto XXVII: 137-140: Whose landlord offers to tell a tale

I once made the same sad error as you,

Thinking more than one of them was chaste,

Until a gentleman of Venice, who,

By great good fortune, my poor tavern graced,

Condescended, with examples, sound and true,

To counter a belief so wrongly-based;

Gian Francesco Valerio his name,

And forever I’ll remember that same.

He knew every tale of their treachery,

That of wives, and mistresses, one and all,

Culled from new and ancient history,

And on his own experience could call,

That showed that not one woman that we see

Is chaste, or rich or poor, or great or small;

And that if one seems purer than another,

She’s but learnt to hide her nature better.

And amongst other tales (he told so many

That a third of them at least I’ve forgot)

One was engraved in my mind, so deeply

Twas as if carved in marble, on the spot;

And what I learnt of the sex was, surely,

Impressed on all that heard, like it or not.

And if, my lord, twould not displease you

I’ll tell these fools the tale, and tell it true.’

The Saracen replied: ‘There’s naught could better,

Please me at this hour, and entertain me,

Than to hear a story, illustrating further

Your opinion, which I hold to, wholly.

And that I may listen close, draw nearer’

He said, ‘thus, I may see you more clearly.’

In the following canto, I’ll relate

All he told Rodomonte, if you’ll wait.

The End of Canto XXVII of ‘Orlando Furioso’