Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXVI: In Pursuit of Vengeance

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXVI: 1-2: Bradamante’s virtues

- Canto XXVI: 3-8: Marfisa joins forces with the three

- Canto XXVI: 9-11: They prepare to fight Bertolagi

- Canto XXVI: 12-25: And put to rout both the enemy parties

- Canto XXVI: 26-29: Marfisa is seen to be a warrior-maid

- Canto XXVI: 30-37: Merlin’s fount described

- Canto XXVI: 38-42: Malagigi prophesies the future harrying of the beast (Avarice)

- Canto XXVI: 43-47: Francis I’s campaign in Italy (1515-1516)

- Canto XXVI: 48-53: Other virtuous enemies of Avarice

- Canto XXVI: 54-57: Ippalca now appears, seeking Ruggiero

- Canto XXVI: 58-60: And tells her tale

- Canto XXVI: 61-65: Ruggiero seeks vengeance for the theft

- Canto XXVI: 66-68: But misses Rodomonte and Mandricardo who arrive at the fount

- Canto XXVI: 69-72: Mandricardo picks a fight

- Canto XXVI: 73-77: And overcomes the four male knights

- Canto XXVI: 78-83: Marfisa takes up the challenge

- Canto XXVI: 84-87: Rodomonte achieves a reconciliation

- Canto XXVI: 88-90: Meanwhile Ruggiero sends Ippalca to Montalbano

- Canto XXVI: 91-97: He finds Rodomonte who declines to fight

- Canto XXVI: 98-102: But Mandricardo finds sufficient reason

- Canto XXVI: 103-108: Rodomonte and Marfisa intervene

- Canto XXVI: 109-114: Yet fail to resolve the issue

- Canto XXVI: 115-118: Ruggiero fights Rodomonte, and loses his sword Balisarda

- Canto XXVI: 119-123: Viviano gives his sword to Ruggiero who stuns Rodomonte

- Canto XXVI: 124-126: Marfisa is unseated

- Canto XXVI: 127-130: Malagigi’s spell sends Doralice’s mount fleeing

- Canto XXVI: 131-133: She is pursued by Rodomonte and Mandricardo

- Canto XXVI: 134-137: Ruggiero and Marfisa decide to pursue them in turn

Canto XXVI: 1-2: Bradamante’s virtues

Noble were they, the ladies long ago,

That loved not riches but only virtue.

In our age we but rarely find them so,

That desire mere sordid gain to pursue.

Yet those who live pure goodness to bestow,

Nor follow Avarice midst all who do,

They are worthy to live and die, so blessed,

Winning glory, midst their eternal rest.

Bradamante, worthy of eternal praise,

Loved not dominion, nor rich treasure,

But the virtue and spirit shown always

By noble Ruggiero gave her pleasure.

And thus, worthy to be loved, all her days,

By so brave a knight, and in such measure,

Was she, for whom tremendous deeds were wrought,

That, in later times, true miracles were thought.

Canto XXVI: 3-8: Marfisa joins forces with the three

As I told you earlier, Ruggiero,

With two of the House of Chiaramonte,

Aldigier and Ricciardetto,

Had gone to aid those in captivity.

And I told you of a knight they met, also,

One that sat a gallant steed, most proudly,

Whose emblem was the phoenix, that rebirth

Finds in the flames, unique upon this earth,

When the warrior had drawn near the three,

(Poised on the wing, as if about to strike)

He wished to try their prowess, instantly,

To see if show and substance were alike;

‘Is there, here, one of you that would meet me,

One that may deem himself the more warlike,’

Cried the knight, ‘that will fight with sword or lance,

Till one yield to the other’s swift advance?’

‘I would,’ said Aldigier, ‘at your wish,

Swing a sword about me, or run a spear,

But another enterprise conflicts with this,

Which you may witness if you linger here.

It grants us the time our speech to finish,

But scarce leaves us time for jousting, I fear.

Six hundred men or more, we now await,

With whom we’ll battle, ere it proves too late.

Love and Pity have brought us to this place,

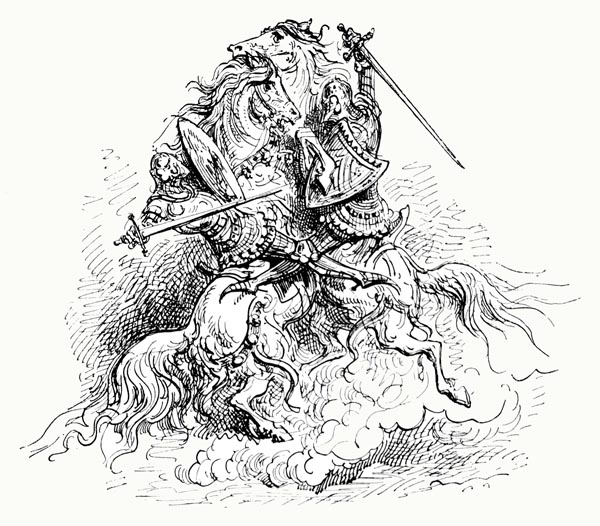

To rescue from their chains two of our own.’

He followed by explaining, face to face,

All the reason, till the whole tale was made known,

‘The justice of your cause I must embrace,’

Said the knight, ‘nor should you contend alone,

For, in my judgement, you appear to be

Peerless in valour and in chivalry.

I sought but to exchange a blow or two,

To witness all your prowess in the field,

But at another’s cost would thus pursue,

The joust, and so to reason I must yield.

I pray you, let me join what will ensue,

And so, lend to your cause my helm and shield,

Hoping to show, amidst your company,

Such a companion as may prove worthy.’

It seems to me that some might ask the name

Of the stranger, who sought to fight beside

Ruggiero and his friends, and thus lay claim

To share the risk, in being thus allied;

She (for a warrior-maid was that same)

Was Marfisa, who Zerbino, for a guide,

Had granted to the wretched Gabrina,

That vicious, and unrepentant sinner.

Canto XXVI: 9-11: They prepare to fight Bertolagi

Those of Chiaramonte, with Ruggiero,

Accepted her kind help, most willingly,

While believing her a male knight, although

She was not quite what she appeared to be.

Soon Aldigier saw riders, neath the flow

Of a banner, and warned the company,

Viewing the flag quivering in the breeze,

That showed the passage of their enemies.

Soon after, as the riders came closer,

They saw that they were clad in Moorish gear,

And knew them for Saracens, and further,

Perceived two prisoners towards the rear,

Each on a sorry nag led by the halter,

To be purchased by Bertolagi, here.

Said Marfisa to the other three: ‘Why wait,

Since our food’s already on the plate?’

Ruggiero answered: ‘Part is lacking,

For the guests have not all appeared as yet,

And, since a grand ball is now preparing,

Not one of all our arts should we forget;

Nor is it not long they’ll keep us waiting.’

As he spoke, both the parties were now met,

For the traitor from his side did advance,

And all was ready to commence the dance.

Canto XXVI: 12-25: And put to rout both the enemy parties

From one side those Maganzeses came,

Leading pack-mules bearing chest-loads of gold;

Costly garments, they carried with that same,

And other gear, the worth well-nigh untold.

On the other, armed, in Lanfusa’s name,

Men had brought the two brothers to be sold.

They saw Bertolagi speaking further

With the Moorish captain, their bold leader.

Nor Aldigier, nor Ricciardetto

Could rest, when they saw the villain there.

With lances levelled, set to strike him low,

They charged, and in the death both knights did share.

One pierced his guts, and saddle, at a blow,

The other his vile face refused to spare.

May like to Bertolagi’s wretched fate

O’ertake all evil doers, soon or late!

At this, Marfisa and Ruggiero

Gave spur to their brave steeds, and joined the fray.

The warrior-maid three victims soon could show,

That on the bare earth, in their death-throes, lay.

Ruggiero’s lance dealt with his mark also,

The Moorish leader, his life reft away.

And then, with a glancing blow to the helm,

Two more he sent to the infernal realm.

An error those villainous bands now made,

That caused their final ruin, and downfall,

For the Maganzeses thought themselves betrayed

By the Moors, on seeing Bertolagi fall.

While on their side, the Moorish cavalcade

Called the others assassins, traitors all,

And attacking, with dart, and lance and sword,

Fell, in a trice, on the opposing horde.

Ruggiero now charged at both the bands,

And took twenty or thirty in his stride;

While the like fell to the maiden’s hands,

Toppled from their steeds on either side.

As many as were touched by those sharp brands

Vanished from their saddles, and so died.

Breastplates and helms ne’er kept them from the pyre,

Destroyed like dry wood in some forest fire.

If ever you remember having seen,

Or heard report, of how, when they’re disturbed,

Wasps gather in the air, and fill the scene,

Ready to sting their foe, if left uncurbed,

And how a swallow then will seek to glean,

A meal, and swoop upon them unperturbed,

Slaying and devouring, so fell those two

Upon the fearful men from either crew.

Ricciardetto and his cousin, though,

Chose not to dance between the parties,

For, leaving the Moors, the pair did go,

With fiery gaze, towards the Maganzeses.

There, Rinaldo’s brother, Ricciardetto,

Possessed of both strength and spirit, to these,

Brought all his fury, doubled by the spite

That well-nigh consumed the vengeful knight.

Aldigier, who shared his cause, likewise,

Seemed like an angry lion, as he sheared

Each helmet that came before his eyes,

Or crushed it like an egg, as it appeared.

Who’d not have dared aught beneath the skies,

Or proved another Hector to be feared,

When Ruggiero and Marfisa there did ride.

Each the flower of chivalry, by his side?

Marfisa, while all the time waging war,

Oft turned her gaze upon their company,

And finding how well each warrior bore

Himself, marvelling, praised them equally.

Yet Ruggiero, in his valour, was, she saw,

Unparalleled, in strength and mastery,

Descended to earth, like the war god Mars,

Quitting that fifth heaven among the stars.

She marvelled at the force behind his blows,

And how they ever fell as he intended,

For, whene’er his sword, Balisarda, rose,

Steel seemed but paper, where it descended.

He pierced helm or breastplate, as he chose,

And oft upon some saddle its fall ended,

Splitting those who that fell blade defied,

Sending half to this, half to the other side.

And oft the same blow slew the steed as well,

And horse and rider tumbled to the ground.

Heads from shoulders flew, beneath its spell,

While thighs from chests were parted, all around.

Five with one blow he cleft, and sent to hell.

But lest you think but lies herein are found,

Where all is true, and yet shows falsehood’s face,

Though I have more to tell, I’ll keep my place.

Good Bishop Turpin who, in all he said,

Knew he spoke the truth, leaving you and I

To think as we please, wrote, as I have read,

Wondrous things, that yet may seem a lie.

Thus, turned to ice, frozen in utter dread,

Marfisa’s victims seemed, as on she sped,

A blazing fire, and Ruggiero no less

Marvelled at hers than she at his prowess.

And if like Mars she had thought Ruggiero,

Perchance the war-goddess, fierce Bellona,

She’d have seemed to him, amidst the foe,

If he’d but known she was a maid in armour;

And emulation had been nurtured so,

Contending, with their cruel blades, to muster

The greatest number slain among that crew,

Flesh, bone, and sinew, pierced, through and through.

The spirit and the valour of those four

Was enough to shatter both the parties.

To put both sides to rout nothing more

Than their own spurs was needed, for to seize

A horse, then ride, was all each warrior

Desired, and then to seek the distant trees;

While those without a steed sadly learned

How the poor foot-soldier’s pay is earned.

Canto XXVI: 26-29: Marfisa is seen to be a warrior-maid

To the victors the field and spoils remained;

Every horseman and muleteer had fled.

Here the Maganzese, there the Moors had gained

Their escape; these their load of gold had shed,

Those had left the captives, as yet constrained,

Viviano and Malagigi; all now sped

To free them, and their squires, and unload,

All that upon the mules had been bestowed.

As well as a quantity of silver

In the form of various vessels, they found

A wealth of female clothes; and, far finer,

A set of Flemish tapestries, once bound

For some royal palace, where the weaver

To form the figures, threads of gold had wound,

Amidst the silk; and then, on which to dine,

Meat and bread, and many a flask of wine.

When they removed their helmets, all could see

That they’d received a warrior-maiden’s aid,

Known by her golden hair, now falling free,

And the lovely and delicate face displayed.

They honoured her greatly, and asked that she

Reveal her name, in glory now arrayed,

And ever courteous among friends, the maid

At last, by their polite requests was swayed.

They were ne’er sated, gazing on her so,

Such had been her appearance in the fight,

While she spoke with none but Ruggiero,

Seeming, indeed, to prize no other knight.

Meanwhile, the squires to and fro did go,

Setting the feast, then the six did invite

To dine there, beside a neighbouring fount,

Shaded, from the sun’s rays, by a low mount.

Canto XXVI: 30-37: Merlin’s fount described

This fount was one that Merlin had made,

One of four in France, set all around

With polished marble, figures there inlaid.

No whiter stone than that had e’er been found.

And, as I say, the fountain there displayed,

Many carvings that did the spring surround,

Wrought with godlike skill, and but that they

Lacked a voice, the breath of life did convey.

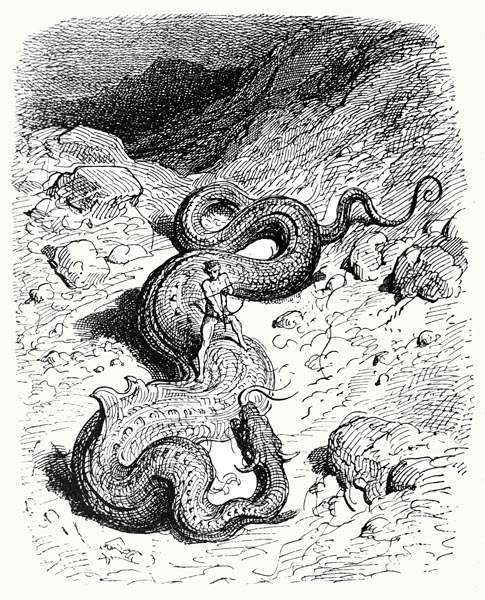

There a beast seemed to issue from a glade,

Cruel in aspect, hideous to the sight,

Ass’s ears, a wolf’s mask, the beast displayed;

Lean with hunger, lion’s claws showed its might,

While the rest a fox’s body portrayed.

It appeared to be ravaging outright,

France, England, Italy and all of Spain;

Of Europe, Asia, the whole world, the bane.

All folk this vile beast had slain or maimed,

The lowest of the low, to those on high,

And the latter it had most surely claimed,

King and satrap, prince and lord, far and nigh.

Many a victim in Rome might be named,

For cardinals and popes, carved, met the eye;

Peter’s throne it had contaminated,

Brought shame on the faith, there celebrated.

Whate’er the vile creature touched, was laid low,

Every temple, every palace, roof and wall;

No castle could defend against that foe,

To its onslaught every fortress must fall.

To be worshipped as divine, here below,

That creature seeks, and hold all folk in thrall,

For it claims to keep the keys to the skies,

And the abyss beneath the world likewise.

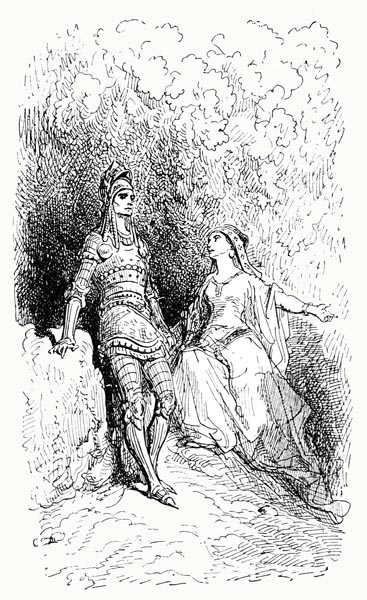

Next a knight was depicted, on his brow

A crown of imperial laurel shown,

With him three youths, each bound by his vow,

Golden lilies upon their garments sewn.

And a lion did that same device allow,

Set to challenge that thing all skin and bone.

And each form had a name above its head,

Or beneath its feet that same could be read.

The noble knight had driven his good sword

Up to the hilt, into the beast’s belly,

‘Francis the First’, his lettering did record;

Twas Maximilian kept him company.

Then, the Emperor Charles the Fifth, had gored

The beast’s throat with his lance, while Henry,

The eighth English king to bear that name,

With a dart, in the chest, had pierced that same.

A lion’s back ‘Leo the Tenth,’ displayed.

It held the beast, by the ears, in its jaws,

And had so shaken, and had so dismayed

The creature, that others had joined the cause.

Their fears, it would seem, had been allayed,

Amending past errors; towards its roars,

Those noble folk thus trooped, though not many,

Yet the beast’s life had been taken swiftly.

Marfisa and the five knights stood and gazed,

Desirous, as they did so, of learning

Whose hands they were that had the beast amazed,

Which had set so many countries mourning;

For though their names upon the stone were raised,

Whom they signified had left them guessing.

They asked, among themselves, if any knew

The history, and could the tale pursue.

Canto XXVI: 38-42: Malagigi prophesies the future harrying of the beast (Avarice)

Viviano turned to Malagigi;

(He had listened, yet failed to say a word)

‘It is for you, to tell that history.

Come, say who they might be, and what occurred;

Who wields (in stone) the lance of chivalry,

That here upon the beast has death conferred?

And he replied: ‘None yet has told the story,

Nor yet enshrined in memory their glory.

Know that those whose names are carven here,

Have not yet graced the world with their presence.

After seven hundred years they’ll appear,

To honour that future age, their task immense.

Twas Merlin the enchanter, that wise seer,

That carved this fount, at Arthur’s expense,

And displayed here things to come, formed in stone,

Sculpted with art and skill, to make them known.

The creature issued from the depths of hell,

When men first set boundaries to their lands.

Wrought weights and measures, all to buy and sell,

Their agreements recorded with cunning hands.

Yet not every place did of this creature tell,

It left many a country free of its demands;

Now everywhere the beast goes wandering,

All nations thus troubling and offending.

From its first appearance to this age of ours,

The monster has grown, and will e’er do so,

And, till its time is past, will shows its powers,

Ever the most hideous root of woe.

The Python, that from old pages glowers,

Though vast, and fierce, and terrible a foe,

Proved not half so dreadful to mortal sight,

Nor so abominable, its presence slight.

Slaughter and desolation it will bring,

All lands contaminated and tainted.

In sculpture you see little of the thing,

Nor its wickedness where’er tis painted.

To a world of its evil wearying,

And with its power too long acquainted,

These lords like bright jewels free of flaws,

Combined, will dare to aid the greater cause.

Canto XXVI: 43-47: Francis I’s campaign in Italy (1515-1516)

None more fiercely will that beast molest

Than Francis, of fair France the noble king,

Who will surpass full many in that quest,

And none shall equal him in so doing,

For he, in splendour, as in all the rest,

Will make many a fine lord seem wanting

In virtue, seeming perfect; so, must yield

All other splendours by the sun revealed.

In the first year of his glorious reign,

The crown not yet secure upon his brow,

He’ll cross the Alps, and so shall render vain

Those who would hold Milan, for such his vow.

Spurred on by just and generous disdain

That unavenged is the affront, ere now,

The French army had suffered at their hands

When they issued forth from their pasture-lands.

And from there he’ll descend to Lombardy,

With all the flower of fair France at his side,

And break the Swiss, so that, fruitlessly,

Their horns they’ll ever raise in foolish pride.

To the shame of Spain and the Papacy,

And the Florentine Pope, in this defied,

He’ll subdue the mighty Sforza castle,

Deemed, ere that, to be impregnable.

His glorious sword will be of more avail

In that than all else with which he’ll arm,

Which first against the vile beast will prevail,

That corrupts every country, and works harm.

Every banner will flee him, without fail,

Or fall to the earth, at the first alarm.

Against that blade no rampart, moat or wall

Will serve as a defence; he’ll conquer all.

This prince will own to every excellence,

That may be seen in a great commander:

Caesar’s spirit, the caution and prudence

Shown by Hannibal at the Trebbia,

And by Lake Trasimene, with the immense

Good fortune of a modern Alexander,

Without which all designs are smoke and mist.

Add peerless munificence to the list.’

Canto XXVI: 48-53: Other virtuous enemies of Avarice

So said Malagigi, and stirred their longing

To know the names of others who would fight

And so combine to slay the hellish thing,

That creature that had others’ deaths in sight.

And, among those found in Merlin’s writing,

Upon Bernardo’s name he did alight.

‘Through him’, said he, ‘Tuscan Bibbiena,

Will be as famed, as Florence, or Siena.

In this, none will be more relied upon

Than Sismondo Gonzaga, Giovanni

Salvati, and Ludovico of Aragon,

Each of that creature a sworn enemy.

While Francesco Gonzaga will make one,

His son, Frederico, of a surety,

His brother-in-law, and son-in-law, also,

The dukes of Ferrara and Urbino.

The son of the latter, Guidobaldo,

Will not lag behind his sire or any other;

Ottobon dal Flisco, Sinibaldo,

And he, will hunt the creature together.

Its neck seared by Luigi da Gazolo,

With an arrow from Apollo’s quiver,

One granted him, with a bow, long before,

And a brave sword, from Mars, the god of war.

Two Ercules, two Ippolitos d’Este,

Another Ercule and Ippolito,

Of the Gonzagas, of the Medici,

Will chase the beast where’er it might go.

Ferrante will match his brother closely,

Guiliano his son, and there also

Will be Andrea Doria, while by none

Shall bold Francesco Sforza be outdone.

Of the generous and illustrious line

Of Avalo, bearing the vast mountain

That hides evil Typheus as their sign,

(That serpent, thus, shall not rebel again!)

Two will appear, who will ne’er resign

First place, but the beast of blood shall drain.

“Francesco di Pescara” see written,

Nigh “Alfonso del Vasto”, his cousin.’

Shall we neglect Consalvo Ferrante,

The pride of Spain, such his reputation,

Who was so praised now, by Malagigi,

Few might equal him midst any nation?

Or William the Ninth of Montferrat? He

Too was named in that brief summation.

Yet they seem but few beside the number

That shall be slain by that evil creature!

Canto XXVI: 54-57: Ippalca now appears, seeking Ruggiero

In simple games and pleasant conversation,

They spent the height of day, their meal done;

Upon the finest tapestries, their station,

Midst the grass and herbs by the river-run.

Viviano, armed, for the duration

Of that pleasant hour or two, neath the sun,

Keeping watch with Malagigi, now saw

A lady, all alone, traverse the shore.

Ippalca it was, from whom Frontino,

Had been taken by fierce Rodomonte,

(The charger belonging to Ruggiero);

With pleas and cries of ‘shame’, fruitlessly,

She’d followed, but then sought Ruggiero

Who, she had heard, was at Agrismonte,

(Though who relayed the news I do not know)

He having rescued Ricciardetto.

And because the place was known to her,

(She had been there many a time before)

She’d tried the fount, and in that manner

Found them, as I’ve said, beside the shore.

But, as a sage and cautious messenger,

That knows to act wisely, when she saw

Bradamante’s brother, Ricciardetto,

She pretended not to know Ruggiero.

To Ricciardetto, herself she addressed,

As if it were to him that she did fare,

While he, who knew her well of old, expressed

His greetings, and then asked why she was there.

Sighing, her eyes yet red, at his behest,

She spoke, but loudly, so the whole affair

Might be heard by Ruggiero, nearby,

On whom she sought not to cast her eye.

Canto XXVI: 58-60: And tells her tale

‘I brought a good and wondrous steed,’ she said,

‘From Montalbano, at your sister’s wish,

One much loved by her, and nobly bred;

Frontino is his name, and one to cherish,

And more than thirty miles the horse I led

Towards Marseilles, the reason for this

Being that she designed that way to fare,

And I was to wait, and attend her there.

I travelled, slowly, in the fond belief

That there was none so foolish as to take

Rinaldo’s sister’s steed, and play the thief,

Once I had pointed out their sad mistake.

But in that I was wrong, for, to my grief,

A Saracen seized him, the cunning snake;

Nor, when I explained who owned Frontino,

Would return the horse, but away did go.

I followed; all yesterday and today,

Have I pleaded and threatened, yet in vain;

I cursed him then, as he went on his way,

And left him not far off, upon the plain,

Where his steed, and he, are hard at play;

For he, with sword in hand, seeks to maintain

Himself against one who doth so contend

He shall gain revenge, for me, in the end.’

Canto XXVI: 61-65: Ruggiero seeks vengeance for the theft

Ruggiero, hearing this, leapt to his feet,

Scarce waiting for her to end her story,

Turned to Ricciardetto, and did entreat

Him to yield the chance to garner glory

To himself, as a favour, just and meet,

To mark his rescue, and with the lady

Let him depart; she would show the way,

So, he might yet restore the steed that day.

Ricciardetto, though it seemed to be

A discourtesy to yield to the knight

That which he should perform himself, nobly

Gave way to Ruggiero, as of right,

Who then took leave of the company,

With Ippalca, who expressed her delight,

And, departing, left the rest stupefied

Marvelling at his valour, open-eyed.

As soon as they were far enough away,

Ippalca told him that she had been sent

By one who in her heart, night and day,

Felt the sense of his worth ever-present;

And, without more ado, did then convey

All her lady had said, and her intent,

Adding that she had hid all this before,

For fear of Ricciardetto learning more.

She added that the thief who, in his greed,

Had taken the horse, had said with pride:

‘Because I know Ruggiero owns the steed,

More willingly I seize it from its guide.

If he would reacquire it, by some deed,

Tell him, since my name I would not hide,

That I am Rodomonte, whose great worth

Casts its splendour throughout all the earth.’

On hearing this, Ruggiero’s face revealed

The extent to which his heart was aflame.

Since his love for the steed he’d ne’er concealed,

Given, also, the source from which it came,

And since the thief’s scorn was unconcealed,

He saw it meant dishonour, and much blame,

If he failed to challenge Rodomonte,

And seek due vengeance for the theft, promptly.

Canto XXVI: 66-68: But misses Rodomonte and Mandricardo who arrive at the fount

The lady guided him, and took no rest,

Wishing to see him meet the pagan king,

And, as the road they swiftly addressed,

Came to where it split, one branch winding

O’er the plain, one seeking the mountain crest,

The one flat, the other steep, both leading,

To where she’d left the pagan; the latter

She chose, it being harsher but shorter.

Her desire to regain the steed, Frontino,

And revenge the wrong on Rodomonte,

Thus dictated her choice, and rightly so,

Since, as I say, they’d arrive more swiftly;

But Rodomonte and Mandricardo,

And the others I spoke of previously,

By that easier path o’er the plain did go,

And failed to encounter Ruggiero.

Their quarrel they’d suspended (as you know),

Until they’d brought aid to Agramante,

While Doralice rode with them, although

The cause of their ongoing enmity.

Now hear the story’s outcome, for lo,

Their road had led to the fount directly,

Where were Marfisa and Ricciardetto,

Aldigier, and his two brothers also.

Canto XXVI: 69-72: Mandricardo picks a fight

At the request of the others, Marfisa

Had donned the dress and ornaments of a maid,

From amongst the riches that Lanfusa

Had to that traitorous tryst conveyed,

And though it was not the custom for her

To appear lest in full armour arrayed,

At their plea she had laid the armour down,

And deigned to appear dressed in a gown.

As soon as the Tartar saw Marfisa,

He thought he might win her in recompense

For Doralice, and yield the latter

To Rodomonte, as if it made sense,

To believe that Love in such a matter

Would countenance that rude offence,

Or fail to wound, with reason, a ‘lover’

Who’d exchange one maiden for another.

Yet he thought to give her to Rodomonte,

So that he might Marfisa then retain,

Thinking her most graceful and lovely,

And well worth a warrior’s toil and pain.

Thus, as if one were as good, suddenly

As another, and the maid his to gain,

He challenged all the knights about her

To joust singly, or be assailed together.

Malagigi was armed, and Viviano,

Since they were standing guard for the rest,

And thus, they rose to meet Mandricardo,

Springing from the grassy turf they pressed,

Thinking to face Rodomonte also,

But he, who thought the Tartar mad at best,

Gave not a sign, nor moved as if to fight,

So, their opposition was this lone knight.

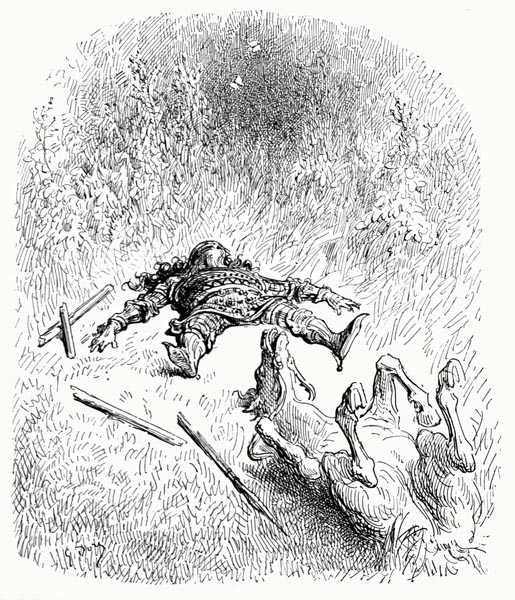

Canto XXVI: 73-77: And overcomes the four male knights

Viviano was the first to advance,

And great of heart he went to meet the foe,

While Mandricardo, lowering his lance,

Seeming stronger, prepared to lay him low.

Each aimed where lay the greater chance

Of planting a fierce, all-conquering blow.

But Viviano struck the helm in vain,

For the other bent not, but wheeled again.

The pagan king whose blow was the stronger,

Burst Viviano’s shield as if twere straw,

He tumbled to the ground in short order,

To sit midst the grass and flowers, as before.

Came Malagigi, to avenge his brother,

And down upon the Tartar warrior bore.

Yet, such his haste for vengeance, he found

He merely joined his brother on the ground.

Aldigier was armed before Ruggiero,

And, in a moment, leapt upon his steed,

Then, defying the might of Mandricardo,

He charged the Tartar monarch, at full speed.

An inch below the visor, his fierce blow

Resounded on the helm, and yet no heed

The Tartar paid, though Aldigier’s lance

Dispersed, in fragments, over half of France.

The pagan king meanwhile aimed at his flank,

With a lance-blow delivered at full strength,

Nor had he his good shield or mail to thank

For saving him, their thickness seemed a tenth

Of the other’s; thus, to left, then right he sank,

And fell amongst the grass and flowers, full length,

His shoulder pierced, his armour to be seen

Dyed crimson, he, pale-faced amidst the green.

After him, Ricciardetto sought the foe,

And, boldly, his great lance he displayed,

Set on showing, as he was wont to show,

That a worthy French champion he made.

And would have taught Mandricardo so,

If all things had been equal, yet was laid

Upon the ground, not through his fault indeed,

But through the sudden fall of his good steed.

Canto XXVI: 78-83: Marfisa takes up the challenge

Now, when no further challenger appeared,

To joust with the pagan king, he thought

The maiden was his prize, so he neared

The fount, to lay claim to the one he sought,

And cried: ‘You are mine, save one endeared

To aiding you remains, and offers aught;

Nor can you refuse, or seek excuse,

Such is the rule of war, in common use.’

Marfisa gazed at him, pride in her face,

And said: ‘Sir, you seem to be in error,

Tis true that your company I would grace,

According to the rules of war, if either

My lord or knight lay there, in deep disgrace,

Among those you’ve tumbled in the heather.

Yet not theirs, nor another’s, but mine own,

He who’d win me, must deal with me alone.

I know how to employ both lance and shield,

And more than one upon the ground have laid.

Bring my steed,’ she cried, ‘arm me for the field!’

And her young squire most readily obeyed.

With surcoat beneath, her gown she did yield,

And her slim body, full of strength displayed,

For in every aspect, save her lovely face,

She resembled Mars in form and warlike grace.

Fully armoured, she girded on her sword,

And with a light leap mounted her charger.

She made the horse wheel, once she was aboard,

Rearing on high, then the ground did quarter.

Levelling her lance at this pagan lord,

Then gripping it tight, she charged the Tartar.

So, on Troy’s far field, Penthesilea

Assailed Achilles in his bright armour.

Their lances flew to pieces as they met,

Splintering like glass in that encounter,

Though neither warrior seemed harmed as yet,

But merely seemed ready to strive harder.

Marfisa, hoping to reduce the threat,

And test his skills more, if they came nearer,

Sought closer combat with the Tartar lord,

And wheeled round, to attack him with the sword.

He cursed the elements, and cursed the sky,

Once he saw she held the saddle still;

And she who’d sought to split his shield thereby,

Cursed no less loudly at heaven’s ill-will.

Both the warriors whirled their swords on high

And made their foe’s enchanted armour thrill,

That enchanted armour, that both knights bore,

Never more needed than in that fierce war.

Canto XXVI: 84-87: Rodomonte achieves a reconciliation

So strongly-wrought their plate was, and chain-mail,

That neither lance nor sword could win through,

So that they might have fought, to no avail,

Another day, it seemed, or even two.

But Rodomonte on the Tartar did prevail

To cease, and not seek to prove the issue;

Saying: ‘If there’s a battle to be fought,

Then let us recommence the one we sought.

For we both agreed a truce, as you know,

So that we then might grant the army aid,

Nor should we joust, or battle with a foe,

Until the debt we owe them has been paid.’

Then he turned, to Marfisa, bowing low,

And the message they’d received he relayed.

And explained the reason they were there:

To aid Agramante in that fierce affair.

Then he begged her, as did Mandricardo,

To now abandon or defer the fight,

To travel with them where’er they must go,

And aid Troyano’s son with all her might,

While raising her fame to the heavens so,

On wings of glory, in worthier flight

Than in a joust of such little moment,

That one might term it an impediment.

Marfisa who was ever keen to prove

Charlemagne’s champions, with sword and lance,

(By solely that, induced to make remove

From a far-off clime to the land of France)

And discover if the tales she might approve,

That their fame was due to skill and not chance,

To accompany the pair, at once, agreed,

Once she’d heard of Agramante’s need.

Canto XXVI: 88-90: Meanwhile Ruggiero sends Ippalca to Montalbano

Meanwhile Ruggiero had, all in vain,

Followed Ippalca o’er the mountain height,

To find that Rodomonte, o’er the plain,

Had swiftly sped, and was no more in sight;

Yet, reading that fresh trail, the news did gain

That he towards the fount had gone, and might

Be not so far ahead, so took his way,

Hoping to meet the Saracen that day.

He asked Ippalca to return once more

To Montalbano, a good day away;

Since for her to seek the fount, he was sure

Would take her far too far from her way.

And he would find Frontino yet, he swore;

Upon her mind, let not the steed’s loss prey,

For to Montalbano, or wherever

She might be, he’d send a messenger.

Then he gave her the letter he had written,

In Agrismonte, that was at his breast,

And many a verbal message was given,

Praying his love’s forgiveness for the rest.

Ippalca, having memorised all, then

Took leave of him and, on her way, she pressed,

Nor did that messenger cease from riding,

Till she reached Montalbano, that evening.

Canto XXVI: 91-97: He finds Rodomonte who declines to fight

Chasing the Saracen went Ruggiero,

Along the road that crossed the level plain,

But only came upon him, even so,

As he drew closer to the fount again.

There too was the Tartar, Mandricardo;

Both had agreed, on the way, to restrain

Themselves from conflict, till they’d brought aid

To their king, facing Charlemagne’s blockade.

On arriving, he recognised Frontino,

And, therefore, the knight upon his back,

And crouched o’er his lance, bending low,

Threatened him with immediate attack.

Humbler than Job proved Rodomonte though,

All his customary pride he seemed to lack,

While the battle that he was ever used

To seek, on all occasions, he refused.

This was the very first time, and the last,

On which the Moorish king chose not to fight.

But his desire to help his monarch surpassed

His wish to prove his prowess as a knight;

And even if he’d held Ruggiero fast,

As a greyhound grips a hare, felt it right

Not to linger for a sword-blow or two,

But rather his prime purpose to pursue.

Even though he knew twas Ruggiero,

So famous that none matched him in glory,

That was set to fight him for Frontino,

A knight of whom (in any other story!)

He would, indeed, have gladly liked to know,

By trial, if his fame was but vainglory,

He nonetheless refused the encounter,

So keen his wish to bring the army succour.

A hundred miles, a thousand, he’d have gone,

Were it not so, to purchase this brave quarrel,

Yet if Achilles himself had brought it on,

He’d still have sought exit from the battle,

So deeply had the ash been poured upon

The fire within; he further grasped the nettle,

And told Ruggiero why he dared not rise,

While asking him to join their enterprise;

For, in doing so, a knight, he said, but showed

The loyalty a follower owes his lord,

And when the siege was lifted, it followed,

They might resume, being of one accord.

Ruggiero said: ‘Tis easily bestowed;

Let us defer our fight till, by the sword,

Agramante is saved from Charlemagne,

But first you must render the horse again.

If you’d have me refrain, till we’re at court,

From proving that you did an ugly deed,

And one unworthy of a knight in short,

In taking, from a maid, my own true steed,

Then give me back Frontino; I’ll support

The deferral then, in principle agreed.

Yet, if not, then the battle twixt us two,

And no truce e’en for an hour, I’ll pursue.’

Canto XXVI: 98-102: But Mandricardo finds sufficient reason

As he made clear his sole demand again,

Either to fight, or return Frontino,

While Rodomonte yet denied his claim,

Another sight had stirred Mandricardo,

And set another cause for strife in train.

He saw the emblem borne by Ruggiero

Upon his shield: an eagle, painted there,

That, above all the birds, commands the air.

The eagle, argent on an azure ground,

Was once the emblem of the Trojan race,

For to the famous Hector, twill be found,

Ruggiero could his own fair lineage trace.

But Mandricardo, viewing it, was bound,

Not knowing this, to deem it a disgrace

That any but himself had there revealed

Famed Hector’s puissant emblem on his shield;

For Mandricardo showed the very same:

The bird that, on Ida, snatched Ganymede.

How, in the perilous castle, he’d laid claim

To that emblem, of old, and by what deed,

I suspect you may know, and how that same

The enchantress bestowed on him; indeed,

She granted him that, and all the armour

That Vulcan had forged for Trojan Hector.

For this reason alone, they had fought before,

Mandricardo and Ruggiero, although

Why they’d ceased the fight, I am unsure,

For naught in my books the cause doth show.

They had not met again, nor fought the more;

But now the shield he saw, and Mandricardo

Shouted aloud, and gave a threatening cry,

Then proclaimed: ‘I challenge you, hereby!

You, that dare my own emblem, thus, to bear,

Tis not for the first time I challenge you.

Madman, think you that I shall let you wear

It so, because I chose, once, to spare you?

Since threats, nor aught else, it seems, can repair

Your brain, and drive this folly forth anew,

I’ll show you why it had served you better

Simply to obey me to the letter.’

Canto XXVI: 103-108: Rodomonte and Marfisa intervene

As smouldering wood suddenly takes light

At a breath of air, and fierce flames ascend,

So, Ruggiero’s anger burned, at the slight

Mandricardo offered, seeking to offend.

‘You think,’ he said, ‘to carry on our fight,

Merely because you see I must contend

With this other, but you’ll learn, in the field,

I’ll have Frontino and good Hector’s shield!

For when before (twas not so long ago)

I encountered you in battle, I recall

I refrained from dealing you the fatal blow

Because you lacked a sword; that was all.

Here deeds, and not sweet mercy, I’ll bestow;

Let this pale bird be presage of your fall.

Here stands the ancient emblem of my race;

Tis you that snatch it from its rightful place.’

‘Rather tis mine, and you usurp the thing!’

Cried Mandricardo, and unsheathed the sword

That Orlando had hurled, midst his raging,

Into the glade, to lie upon the sward.

Ruggiero, that chivalrous being,

Could not but draw his own, in accord,

Seeing Mandricardo hurl his lance

To the ground, and then, blade in hand, advance.

He gripped his shield tight, and Balisarda,

(His own blade) and then prepared for the fight;

But Rodomonte drove his steed, then Marfisa

Betwixt the two, and each implored their knight

To end the contest, sooner not later,

Regardless of whiche’er was wrong or right.

While Rodomonte cried that the Tartar king

Had twice broken their pact, without trying,

Since firstly, he’d thought to win Marfisa,

And more than once had jousted for the maid,

And now sought to deprive a warrior

Of his device, while both of them delayed,

He said, in aiding their royal leader:

‘Twere better that the start we both made

To our worthier contest were resumed,

Than see our time, in lesser strife, consumed.

On such condition was our treaty made,

And the truce between us is still in force.

When we have fought, and thus its terms obeyed,

Then he and I may battle for the horse,

While, if you survive, you may turn your blade

Against that ill shield of his, in due course.

Though I’ll deal you such a mortal blow

There’ll be little left for Ruggiero.’

Canto XXVI: 109-114: Yet fail to resolve the issue

‘That which you expect, you shall not gain,’

Said Mandricardo to Rodomonte,

‘I’ll grant you what you’d rather not obtain,

And make you sweat, from head to toe, freely,

Yet sufficient strength and more I’ll retain,

(As the fount never fails, that yields plenty)

To meet Ruggiero and a thousand more,

With all the world beside; a plenteous store.’

The anger, and the flow of words, increased,

On this side and that; for Mandricardo

A torrent of disdain and scorn released,

Directed at the Moor, and Ruggiero,

Who unused to defiance that ne’er ceased,

No longer wished for peace, but to show

His warlike face; Marfisa hovered there,

But the rift she alone could not repair,

Like a farmer, who if the river leaches

Through its high bank and seeks to find

A new channel, hastes to stem the breaches,

And save the pasture and the crops behind,

Yet sees the flow drown the farthest reaches;

For though each open gap is filled and lined,

Yet, elsewhere, the foundering bank gives way,

And the water through further holes will play.

So, while Ruggiero, and Mandricardo,

And Rodomonte, quarrelled together,

Seeking their greater vigour to show,

And labouring to outdo one another,

Marfisa sought to dam the angry flow,

Yet wasted her time, and all her labour;

For as soon as she drew one from the fight,

The others but resumed with greater spite.

Marfisa, seeking to achieve accord,

Said: ‘Listen, lords, to my wiser counsel,

Twould be best to defer, and yet record,

These arguments, until, all being well,

You have your monarch’s safety assured;

Or I’ll fight Mandricardo for a spell,

If you so wish, and see if he can win me,

By force of arms, as he sought, formerly;

For if to succour Agramante is your aim,

Let us do so, and not contend together.’

‘I make no obstacle, naught do I claim,’

Said Ruggiero, ‘but my stolen charger,

Let him grant me my Frontino, for shame,

Or look to his own defence, as ever.

I’ll return with my fine steed from the field,

Or remain, while my parting breath I yield.’

Canto XXVI: 115-118: Ruggiero fights Rodomonte, and loses his sword Balisarda

‘The former’s not so easy in the doing,’

Rodomonte replied, and then again:

‘I protest; if any harm comes to our king,

The fault is yours, for I, as yet, maintain

That I shall perform whate’er is fitting.’

But Ruggiero found no way now to contain

His fierce anger, and gave him little heed,

But gripped his sword, while readying his steed.

Like a savage boar, he drove at Rodomonte,

Striking him with his shoulder, and his shield,

And dismayed Algiers’ king so completely,

That one foot left the stirrup, as he reeled.

Mandricardo cried: ‘Cease, or as surely

You’ll fall to me, and your surrender yield!’

Savagely and fiercely, he charged Ruggiero,

Striking his helm, and with a mighty blow.

Upon his horse’s neck, Ruggiero bowed,

Nor could he rise again, as he now sought,

For Rodomonte’s blade, echoing loud,

Had struck against him also, as they fought,

And if the helm had not been well-endowed

With adamantine steel, his face had caught;

The pain assailed him with its fierce demand,

And sword and bridle fell from either hand.

His charger bore him swiftly o’er the field,

While Balisarda fell towards the ground.

Marfisa, his true comrade was revealed,

For she was all aflame, a queen uncrowned,

Angered that the pair had sought to wield

Their swords against a single foe; she found

Mandricardo, yet unscathed, and her blade,

To his head, a mighty stroke now conveyed.

Canto XXVI: 119-123: Viviano gives his sword to Ruggiero who stuns Rodomonte

Rodomonte chased after Ruggiero,

For one more blow and Frontino was won:

But Ricciardetto and Viviano

Drove between them, ere the course was run.

The former warrior parted, so,

Rodomonte from his prey, the latter one,

Viviano, placed his sword in the hand

Of Ruggerio (no longer unmanned).

Returned, now, to himself, Ruggiero,

Re-armed by Viviano with that blade,

Charged at Rodomonte, as if the blow

Were naught; much as a lion, undismayed,

Raised on a bull’s horns from the ground below,

Denying pain, would see the beast repaid,

And, spurred by indignation and anger,

Is merely goaded to revenge thereafter.

Ruggiero struck at Rodomonte’s head,

And had it been his own sword in his hand

(That, through a treacherous blow, as I have said,

Had slipped his grasp, he by the stroke unmanned)

I doubt the helm, that stood him in good stead,

Had protected him, though forged to withstand

Many a blow, by Babel’s king once wrought,

That a war with the heavens long had sought.

Discord (thinking naught could there exist

But contention and strife, now stirred anew,

Nor could truce, pact, or treaty e’er persist)

Advised her sister she might thus renew

Acquaintance with her monks so sorely missed,

And she would seek, with her, that godly crew.

Let both depart; while we turn to the blow

That had nigh on laid Rodomonte low.

Ruggiero’s blade had struck with such force

That the helm and cap Rodomonte wore

Had landed on the crupper of his horse,

Brave Frontino, that is; three times or four

The Saracen swayed on his errant course,

As if he might fall head-first to the floor,

And would have lost his sword, I insist,

If the hilt had not been tied to his wrist.

Canto XXVI: 124-126: Marfisa is unseated

Marfisa meanwhile fought with Mandricardo,

Till sweat ran down his brow, face, and chest,

And he had no doubt wearied her also,

Though their breastplates were as yet un-distressed,

So impenetrable the armour both did show,

And both, in the saddle, as yet, did rest;

But Marfisa, with a turn her charger made,

Found herself in need of Ruggiero’s aid.

For Marfisa’s valiant steed, in wheeling,

Where the ground was all soft and slippery,

Was unable to stop itself from sliding,

And fell upon its right side, heavily,

And then was struck, while swiftly rising,

By Brigliadoro (scant courtesy

Being shown by his rider, Mandricardo)

Such that her horse fell again, at the blow.

Seeing Marfisa tumble to the ground,

Ruggiero galloped swiftly to her aid,

Free to do so, since Rodomonte he found,

Partly stunned and helpless, retreat had made.

He’d have had the Tartar’s head, at a bound,

As he struck at his helm, had he his blade,

Balisarda, and not Viviano’s, instead,

Or Mandricardo other helm on his head.

Canto XXVI: 127-130: Malagigi’s spell sends Doralice’s mount fleeing

Rodomonte, who his senses had regained,

Wheeled around, and espied Ricciardetto,

Recalling how his charge had been contained

By that knight granting aid to Ruggiero.

He drove at him, and his charge maintained,

And had dealt him his reward, a fierce blow,

Had not Malagigi taken his part,

With a fresh display of enchantment’s art.

Malagigi, who knew every evil spell

That could be cast by the sagest enchanter.

(And could halt the sun, and the moon as well;

The book he needed, he lacked however)

Recalled now how to conjure, out of hell,

A tame demon, and then bade it enter

The body of fair Doralice’s horse,

And sting it, till it took a random course.

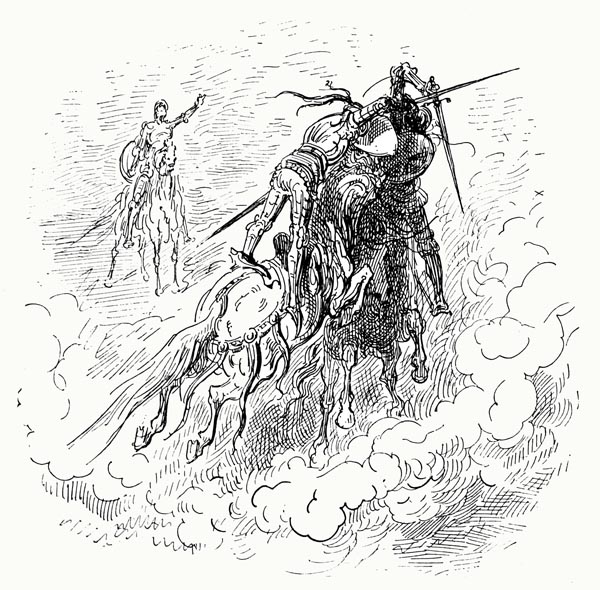

Into that gentle palfrey, which now bore

King Stordilano’s most lovely daughter,

Viviano’s brother conjured, by his lore,

A fallen angel summoned from the lower

Depths, while the steed, that had ne’er stirred before

Except, indeed, at its mistress’ order,

Now took a sudden leap towards the sky,

A good thirty feet long, and sixteen high.

It was a mighty leap, yet not the kind

That ejects the rider from the saddle;

Yet seeing herself leave the earth behind,

The lady gave a cry (as if twere fatal).

The palfrey, having leapt, running blind,

Took off, as one possessed by the devil,

The lady crying out for aid, in haste,

As an arrow’s speed that palfrey outpaced.

Canto XXVI: 131-133: She is pursued by Rodomonte and Mandricardo

On hearing her loud cry, Rodomonte

Retired from the battle, and pursued her,

And, wherever went the maddened palfrey,

He sped after it to bring her succour.

Mandricardo did no less, ending swiftly

His tussle with Ruggiero and Marfisa,

And seeking neither truce, nor peace, wildly,

Set off in his pursuit of Rodomonte.

Now, Marfisa had risen from the ground,

Her mind ablaze with anger and disdain,

Thinking to win revenge, and yet she found

Her enemy had vanished o’er the plain.

Ruggiero roared, as he gazed around,

Like a lion, the fight deferred again,

He knew their own steeds would chase Frontino

In vain, not to speak of Brigliadoro.

Ruggiero would not cease till he’d received

That brave steed of his from Rodomonte;

Marfisa would not rest till she’d achieved

Vengeance on her hateful enemy,

To leave their quarrel thus, they believed,

Seemed against the true law of chivalry,

And the mutual intention of the pair

Was to follow those offenders everywhere.

Canto XXVI: 134-137: Ruggiero and Marfisa decide to pursue them in turn

If they failed to overtake them on the way,

They would find them with the Moorish army,

Knowing that summons they must yet obey:

To fight the Franks, or fail in their duty.

So, for Paris, they both would ride that day,

Where they thought to pursue their enmity

Against the other pair, yet Ruggiero

Wished first to speak with Ricciardetto.

So, he returned to seek his lady’s brother,

Professing himself a friend, who would share

In good or evil fortune, while, together,

They might venture an action, anywhere.

He begged him then to salute his sister,

In his name (and o’er this he took great care)

Such that not e’en the slightest suspicion

Did he raise, regarding his own position.

He of Viviano, and Malagigi,

And the wounded Aldigier, took leave;

While those three knights (in his debt) repeatedly,

Proffered their services, as you’ll conceive.

Marfisa (her mind on Paris, ready

To depart) neglected them, as I believe,

But, a little way, the two brothers rode,

And a distant salute on her bestowed,

As did Ricciardetto, but his cousin,

Aldigier, suffering, needed rest.

The two fierce kings to Paris sought to win,

While the two behind pursued an equal quest.

In the very next canto, I’ll begin

To reveal the deeds (wondrous I’d suggest,

Nigh superhuman others will maintain)

Wrought by those warriors gainst Charlemagne.

The End of Canto XXVI of ‘Orlando Furioso’