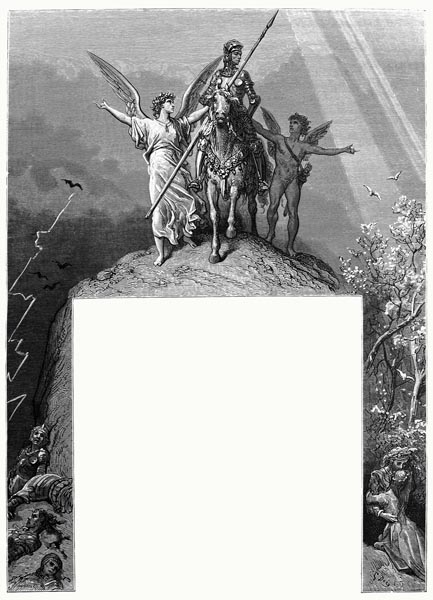

Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXV: Ricciardetto's Tale

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXV: 1-4: Love may bring good as well as ill

- Canto XXV: 5-10: We return to Ruggiero and the lady

- Canto XXV: 11-16: Ruggiero sets upon the hostile crowd

- Canto XXV: 17-24: The youth Ricciardetto, Bradamante’s twin brother, is rescued

- Canto XXV: 25-28: Ricciardetto begins his tale

- Canto XXV: 29-33: Bradamante reveals to Fiordispina that she is female

- Canto XXV: 34-37: Fiordispina’s lament

- Canto XXV: 38-44: She offers Bradamante hospitality

- Canto XXV: 45-48: Bradamante returns to Montalbano

- Canto XXV: 49-52: Ricciardetto seeks to take advantage of their likeness

- Canto XXV: 53-57: And is welcomed by Fiordispina

- Canto XXV: 58-64: He tells a tale of how his sex was changed

- Canto XXV: 65-70: And encourages her to prove his new state

- Canto XXV: 71-72: As his tale ends, they reach Agrismonte

- Canto XXV: 73-76: Ruggiero learns of the capture of Viviano and Malagigi

- Canto XXV: 77-80: He proposes that that they free the brothers

- Canto XXV: 81-85: He agonises over his delay

- Canto XXV: 86-91: He writes to Bradamante

- Canto XXV: 92-97: The cousins set out to free the brothers

Canto XXV: 1-4: Love may bring good as well as ill

Ah, the great tension, in a youthful mind,

Twixt ardent love, and the desire for praise!

Which to pursue, by which to be defined,

When each in turn its opposite outweighs?

In those two knights, duty it was, we find,

And honour, that seemed uppermost always,

Their quarrel, one provoked by love, delayed,

Till to the Moorish camp they’d furnished aid.

Yet love triumphed, for were it not that she,

Their lady, had commanded them to cease,

Neither man would have done so, willingly,

Ere he had won; yet her they sought to please,

Though Agramante, and his whole army,

Might wait endlessly for aid, in great unease.

Love, then, does not forever bring us ill,

Harm he deals, and yet may help us still.

Now that both the pagan knights had simply

Postponed their bout of hostility,

They travelled towards Paris, with the lady,

To add their strength to the Moorish army;

And the little dwarf was of their company,

Who, to satisfy the other’s jealousy,

Had tracked the Tartar warrior and, lately,

Brought him face to face with Rodomonte.

They came to a meadow; there, knights they saw,

Resting beside a stream and, of these, two

Were free of armour, two bright helmets wore,

A lovely lady also met their view;

Of these five, elsewhere, I’ll tell you more.

But first Ruggiero I seek anew,

That true knight, who had hurled the magic shield

Into the well’s dark depths, as I revealed.

Canto XXV: 5-10: We return to Ruggiero and the lady

He had scarcely gone a mile from that well,

Ere came a messenger, one of those sent

By King Agramante that he might swell

The Moorish army, his need full urgent.

This messenger the whole tale did tell,

Of how, within the camp, they were pent,

Who if they were not aided in the fight,

Would lose life or honour there, outright.

Ruggiero paused awhile, assailed by doubt,

Many a thought pursued, yet this was not

The place, nor had he time, to ravel out

Which cause was best; and so, upon the spot,

Dismissed the courier, then turned about:

Let the lady and the youth be not forgot!

He halted but a moment, and was gone,

And, from hour to hour, he hastened her on.

In pursuing their former road once more,

(As the sun declined) they came to a city,

That Marsilio, in mid-France, in that war,

Had won from Charlemagne, previously;

Yet no challenge, at drawbridge, gate, or door

Did they meet, nor was there threat of any,

Though in the ditch, and round the palisade,

Stood many men, their arms about them laid.

Because they had recognised the lady,

Who accompanied him, they allowed her,

And our Ruggiero, to pass freely,

Nor asked them whence they rode, or whither.

They reached the square (a pyre waiting darkly)

So full, their arrival caused little stir,

And beheld there the youth, condemned to death,

Pallid of face, that scarce could draw a breath.

Ruggiero, who upon that face did stare,

(One bowed low, and wet with many a tear)

Twas as if he saw Bradamante there,

The two so like to his eyes did appear.

The greater the likeness seemed twixt that pair,

The more at that fair visage he did peer.

‘Oh, tis Bradamante,’ he cried, ‘or I

Am not Ruggiero; her form I spy.

She’s proved too bold, in seeking to defend

The fair youth who was, here, condemned to die;

And has met with some ill chance, in the end,

Been captured, and exposed here to the eye.

Ah, why was she in such haste to expend

Her brave effort, ere my bright steel came nigh?

But, thank God, I am here, and my sharp blade,

And come in time, it seems, to bring her aid.’

Canto XXV: 11-16: Ruggiero sets upon the hostile crowd

Without more delay, he drew his weapon,

(His lance he’d broken, in that former place)

And with his charger he bore down upon

The hostile crowd, striking at back and face,

And brow, and cheek, and throat, till all were gone

In sudden flight, and left but empty space.

Shouting, with cries of woe, those folk had fled,

Many with bruised limbs, or an aching head.

Just as a flock of birds, feeding, quietly,

Will take flight across the marsh, if they see

A hawk in the air, descending swiftly,

Amidst them all, to seize one, savagely,

Scattering o’er the wide sky, suddenly,

Caring but for their own precious safety,

While leaving some companion to die,

So that crowd when Ruggiero drew nigh.

Our brave knight beheaded five or more,

Who proved too slow, in running from the square;

And to the chest he split another four,

Or to the jaw, or eyes, none did he spare.

Admittedly not one a helmet bore,

Yet many a steel cap gleamed, here and there,

Though, had a helmet clad each wicked head,

His sword would still have left as many dead.

His strength was greater in my opinion

Than any you will find in our own day,

And likewise greater than a bear or lion,

Or any beast, found here or far away.

An earthquake, or that devilish invention,

None of Satan’s but my lord’s, I should say,

Might compare (his bombard, wreathed in flame,

E’er parts earth, sea, and heavens, in his name).

For with every stroke one or more he slew,

And left them bleeding there, on the ground.

Even four or five at once he overthrew,

Until soon a hundred corpses lay around.

That sword of his, that rose and fell anew,

For cutting steel like butter, was renowned:

In Orgagna, had Falerina made

(Bent on Orlando’s death) that very blade.

Having done so she was most unhappy

To see her garden ruined by the sword.

What havoc it must have wrought, when, fiercely,

It was wielded there, by Anglante’s lord!

For if e’er Ruggiero, in a frenzy,

E’er such fury, such power did record,

Twas here revealed, and here displayed,

In his efforts to bring his lady aid.

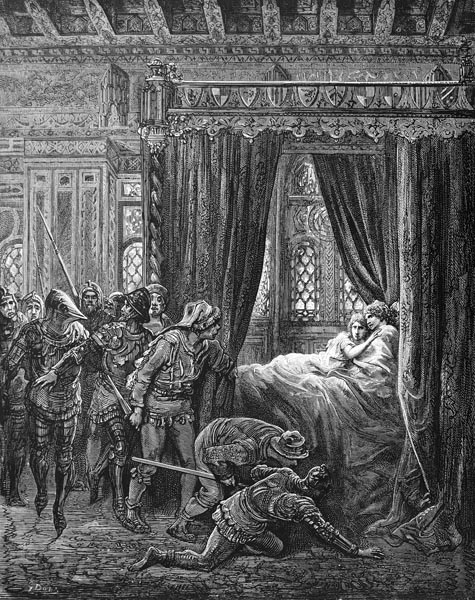

Canto XXV: 17-24: The youth Ricciardetto, Bradamante’s twin brother, is rescued

Much as a hare runs when the hounds are freed,

Those in the crowd now fled, before the knight.

Numberless those who vanished at full speed,

While many Ruggiero slew outright.

Meanwhile the young man, bound as was decreed,

The lady released, and then armed the knight,

As swiftly as she could, with sword and shield,

So that he might boldly take the field.

He, who was greatly riled, as best he could

Sought vengeance on the wicked populace.

And, readily, gave such proofs of knighthood,

As showed a worth to match his noble face.

The Sun dipped his gilded wheels in the flood

And sank into the west as, with God’s grace,

Ruggiero issued from the city square,

With the youth and went, victorious, from there.

Now, once the young man found himself safely

Beyond the city gate, he sought to render

His thanks to Ruggiero (speaking nobly,

And warmly) for aiding one who never

Had met with him before, twas surely

At the risk of the knight’s life, and his prayer

Was to know the name of his saviour,

To whom he would be obliged, forever.

‘I see’, thought Ruggiero, ‘the fair face;

The features and aspect are as lovely,

And yet I do not hear the flowing grace

And charm, in my ears, of Bradamante;

Nor do such thanks as these seem quite in place,

Addressed to a lover, whose loyalty

Is not in question; if this were that same,

How could she have, so soon, forgot my name?’

To ascertain the truth, accordingly,

Ruggiero said: ‘I’ve seen you elsewhere,

And have thought and thought, yet seemingly

I neither know, nor can remember, where.

If you yourself can recall it, tell me,

And I request that you your name declare,

So, I may know whom I have saved today

And rescued from the fire, and the affray.’

‘Tis possible you’ve met me,’ he replied,

‘And yet, in truth, I know not where nor when,

Though I like to roam the roads, on every side,

Seeking strange adventure. It may be, then,

That it was my sister, who doth often ride

Clad as a knight, and fights amidst the men.

My twin is she, we so alike to view,

E’en kin fail to distinguish twixt us two.

Not the first to find yourself in error,

Nor the second, are you, for this is true:

My father, my brothers, e’en my mother,

Have made the very same mistake as you.

My hair is cut short, as many another,

Hers she wore coiled and plaited, to the view,

And, with her tresses wound about her head,

She often acted for me, in my stead;

And then she was wounded by a Moor,

(A head-wound; the tale too long to teach)

And a holy man, so he might restore

Her to health, trimmed her tresses; each from each

To tell is now e’en harder than before,

Differing but in sex, and name, and speech.

She is Bradamante, I Ricciardetto,

She sister, and I brother to Rinaldo.

Canto XXV: 25-28: Ricciardetto begins his tale

Were I not afraid of displeasing you,

A most wondrous tale I might recite,

Arising from the likeness twixt us two,

Ending in woe, though starting in delight.’

Ruggiero, who no greater pleasure knew

Than hearing news of his fair maiden-knight,

For no sweeter music his ear could win,

Begged him to do so; thus, he did begin:

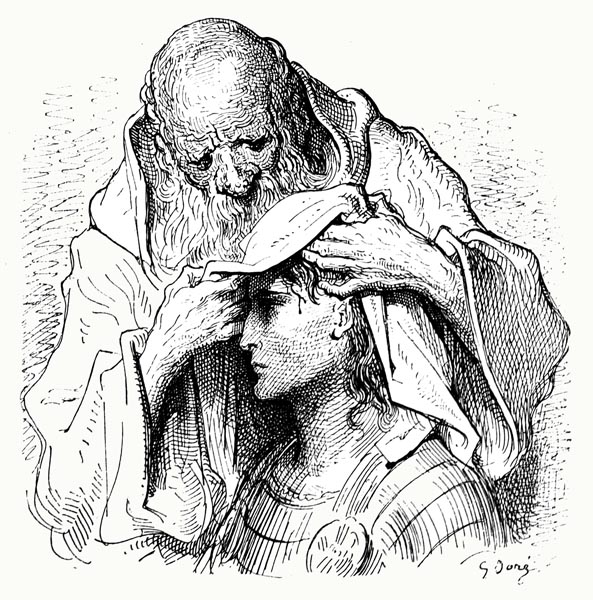

‘It had chanced, one day, that my fair sister

Was riding within a neighbouring wood,

When she was wounded by a warrior;

Her head, un-helmeted, was drenched with blood.

Her hair was trimmed, so as to uncover

The cut, and render what was damaged good.

Once it was healed, and she with rest restored,

With shorn locks, once again she roamed abroad.

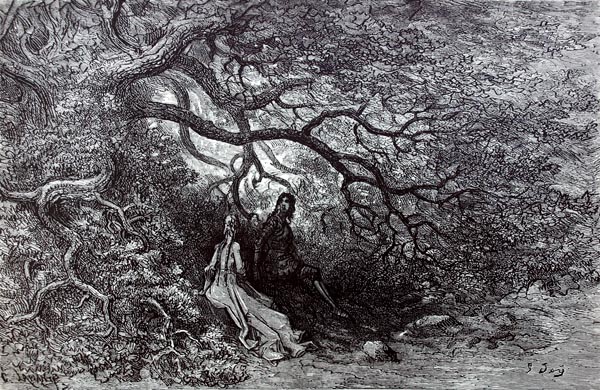

Wandering, she reached a shaded fountain,

Where, both tired and troubled, she dismounted,

Removed her helm and, freed from it again,

Upon the grass, with sleep her pain surmounted.

A sweeter tale, than this you entertain,

I think was never in this world recounted,

For, there, appeared Fiordispina of Spain,

Hunting freely in the woods, with her train.

And finding my sister there, in the shade,

Fully-armoured, but for her head and face,

(With a sharp sword for a distaff displayed!)

Believed that she was male, and, for a space,

A survey of that martial form she made,

And her heart was conquered, and did race.

Then, waking her, she sought her company,

And they hunted midst the woods, happily.

Canto XXV: 29-33: Bradamante reveals to Fiordispina that she is female

Once they were in a solitary glade,

No longer fearing they might be surprised,

In words, and manner, she her heart displayed;

Wounded deeply, Bradamante surmised.

For her ardent sighs, the glances she relayed

Expressed her soul’s desire, quite undisguised.

The colour of her cheeks thus waxed and waned,

While, boldly, a stolen kiss she obtained.

My sister was certain that she, in error,

Thought her to be a man, nor could she see

Any way to aid her in that matter,

And found herself in some perplexity.

“Tis, better,” she thought, “I disabuse her

Of that foolish belief, and she in me,

Finds a chivalrous woman, rather than

Let myself be taken for some vile man.”

And she spoke true; for it would be vile,

Though befitting a man but made of straw,

If, set beside a lovely lady the while,

One so sweet, and amorous, and more,

She was to speak in a deceptive style,

A cuckoo in the nest, and pain ensure.

Shaping her speech in a careful manner,

My sister therefore revealed the matter:

That she, like Hyppolite and Camilla,

Sought glory in arms; that she was born

On the Moroccan coast, in Asilah,

Trained, from a child, to weapons, night and morn.

This quenched not Fiordispina’s fervour,

Won by the rose of love, pricked by the thorn.

Too late, for that deep wound, the remedy,

Love’s dart having pierced the maid so deeply.

For my sister’s face seemed no less lovely,

No less pleasing her manner, nor her guise,

Naught eased that heart, in its extremity,

Still delighting in those beloved eyes.

Viewing, in her, the flower of chivalry,

Desire could not but in her heart arise.

Yet, when she thought “She is indeed a maid,”

How could she not be saddened and dismayed?

Canto XXV: 34-37: Fiordispina’s lament

Whoe’er had heard her sorrow and lament,

That day, would have wept sad tears beside her.

“Who, she cried, e’er suffered cruel torment

That would not have deemed mine the crueller?

With another love I might have been content,

Pure or impure, and known how to gather

The rose from the thorn, to my heart’s delight;

This alone plagues me, with no end in sight!

If twas your wish, Love, to torment me so,

Because my happy state has angered you,

You might have found some other form of woe,

One you’ve provoked in others, old or new.

Nor midst the herds, nor among people, though,

Do females mate with females, maid nor ewe;

Woman with woman cannot procreate;

Nor shall doe with doe; yet it seems my fate,

To long for that which none on earth can gain,

And suffer your harshness, Love, and cruelty.

All is your doing, till, in my woe and pain,

I stand a prime example of folly.

Semiramis did a passion entertain,

For her own son, it seems, impiously,

Myrrha for her father, and Pasiphae

For that bull, yet my folly’s worse I say,

The female there was but drawn to the male,

And hoped to mate, and did, or so I’ve read;

For the Cretan queen did herself avail

Of a wooden cow, the others their bed;

Yet if Daedalus flew here, he’d now fail,

With all his many skills, this conch to thread,

For Nature, wrought this puzzle, with great care,

She the most powerful here, as everywhere.”

Canto XXV: 38-44: She offers Bradamante hospitality

So, the fair lady spoke, and lamented,

And was slow to end her sorrowing,

Then tore at her hair, as if demented,

As if cruel vengeance she was seeking,

On herself; my sister too, tormented,

Wept for pity, her pain and woe sharing;

From folly, and from vain desire, she sought

To draw her, but in vain; scant ease she brought;

For, she who searched for aid, and not comfort,

Merely lamented, and was grieved, the more;

While the day declined, and time grew short,

Ere the sun passed from the western shore,

For those who a place of rest now sought,

Nor would spend the night on the woodland floor.

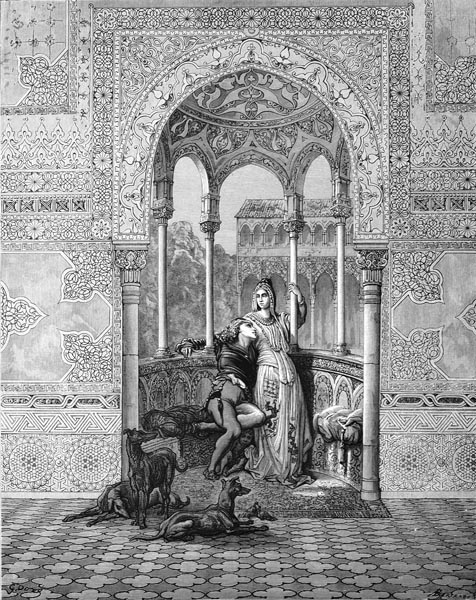

Thus, the lady invited Bradamante,

To her dwelling in the nearby city.

My sister could scarce deny her request,

And so, they reached the place together,

Where, but for you, those folk, who sore oppressed

My poor self, had ended me forever.

There Fiordispina, saw her guest caressed,

By all, welcomed with grace and honour.

And there in female dress she was arrayed,

That all might know her for a warrior-maid;

She, deeming no advantage would be won

By assuming her male garb in that place,

Sought to avoid reproach from anyone,

And, therefore, her bright armour did replace,

Thinking that the ill to the maiden done

By viewing that virile gear, might, of grace,

Through this other that the eye did greet

Chase away Fiordispina’s fond conceit.

The two maids shared a common bed, that night;

Their couch the same, yet different their repose.

For the one slept; the other, in sad plight,

Wept, as the flames of fiercer longing rose.

If, sometimes, sleep did on her lids alight,

Brief was it, and deceitful were its throes;

For, therein, heaven had granted freely,

A more helpful sex to Bradamante.

As a feeble patient, oppressed by thirst,

Closes her eyes, possessed by longing

For water, and, in restless sleep, is cursed

With fond memories of fountains bubbling,

So poor Fiordispina’s dreams rehearsed

Cruel images of delight, in passing.

She woke, and then, the form she loved she sought,

Yet found but vain all that those dreams had brought.

How she prayed that night, what vows she made,

Offered to her Mahomet, in despair,

Hoping that by some miracle displayed,

My sister might another sex now share!

Yet all her vows brought her but little aid,

While heaven, it seemed, mocked every prayer.

Night passed, and Phoebus his bright locks unfurled,

Rose from the sea, and shed light on the world.

Canto XXV: 45-48: Bradamante returns to Montalbano

When they left their bed, as dawn was breaking,

Fiordispina’s sadness was augmented,

For Bradamante now spoke of leaving,

(So that the maid no longer was misled).

The fair lady, as a gift in parting,

Gave her a Spanish jennet, nobly bred,

With gilded trappings, and a surcoat too,

Embroidered by herself, and rich to view.

She accompanied Bradamante some way,

Then fair Fiordispina returned, weeping.

My sister rode so quickly that same day

She reached Montalbano, and a greeting

From her brother and mother, I may say,

Most joyful, for, both fearful and doubting,

We were concerned, hearing nothing of her,

Lest she might be dead, and lost forever.

Her helmet doffed, we wondered at her hair,

Cut short, once coiled in braids above her brow,

No less than at the surcoat she did wear,

Foreign in appearance, while she did now

Rehearse her story that with you I share,

From start to end, the very same, I vow:

How she was wounded in the wood, and so

Her locks were shorn in healing of the blow;

And then how, sleeping by the river-bank,

She was surprised by the lovely huntress,

That, deceived by her appearance, drank

Of Love’s potion, and to foolish excess;

Then of the sorrow into which she sank.

(The tale stirred pity for the maid’s distress)

And how she’d lodged with her, and all that passed

Ere she returned to Montalbano, at the last.

Canto XXV: 49-52: Ricciardetto seeks to take advantage of their likeness

I’d long taken note of Fiordispina,

Her sweet face, her eyes, her lovely glance,

Having seen her once in Saragossa,

Found her pleasing there, and later in France.

Yet would not my desire fix upon her,

For hopeless love is a dream, a mischance;

But now, within, my winged hopes did soar,

The ancient flame rekindling one more.

By means of such hopes, Love weaves his net.

Though he’d failed to spin such threads, ere now,

I was caught, and he thus taught me to forget

All else, and when to win the maid and how.

For the snare with which to catch her was set;

My likeness to my sister, you’ll avow,

Means I’m oft taken for Bradamante,

And thus, might deceive the maid completely.

To act, or not to act? It seems to me

Always good to pursue what brings delight.

My thoughts and plans I mused on privately,

Nor sought advice regarding what was right.

At night, I went to where I might, quietly,

Don my sister’s armour; long ere twas light,

I did so, took her steed, and rode away,

Down that same road, not waiting for the day.

I journeyed all that night (Love was my guide)

To seek the home of fair Fiordispina,

And arrived, ere the sun that long did hide

In the western flood, had risen higher.

Blessed was he that hastened to her side,

And spoke the good news ere any other,

Hoping to acquire, for his diligence,

Grace, and favour, of her countenance.

Canto XXV: 53-57: And is welcomed by Fiordispina

All who were there took me, mistakenly,

As you yourself did, for Bradamante,

The more so since I rode her steed, clearly

Clad in the armour she’d worn previously.

Fiordispina soon came to welcome me,

Embraced me, and showed every courtesy,

With a face so happy, that such love betrayed,

No greater joy could she have e’er displayed.

About my neck she threw her lovely arms,

Clasped me sweetly, and my mouth she kissed,

(Think how the arrow then, with which Loves harms

The lover, pierced my heart, it ere had missed!)

Then took my hand, employing all her charms,

Led me to her chamber, and let none assist

With stripping me of my helm and armour,

Asking that none trouble us thereafter.

To my attire, she then herself addressed;

And, as if I were a maid, with great care,

Soon had me in most costly garments dressed,

And, in a golden net, then veiled my hair.

My eyes a female modesty expressed,

Nor aught to deny that sex did declare;

While my voice, that might yet have betrayed me,

I attuned to the notes of the lady.

Then we issued out among the many

Personages that now adorned the hall,

Who showed us honour as great as any,

That royalty ere received, one and all.

Yet, many a time, I smiled, covertly,

At all those men my fair looks did enthral,

That yet knew not what lay beneath my dress,

As they eyed me with lasciviousness.

When that festive eve was more advanced,

And the tables had been cleared (we had dined

On seasonal fare, yet richly enhanced)

Fiordispina could find no peace of mind

Till she had sought to know why it so chanced

That I’d returned thus, or if twas designed;

And so invited me, by kindness led,

To sleep that night with her, and share her bed.

Canto XXV: 58-64: He tells a tale of how his sex was changed

Once her ladies, the maids, and all the rest

The chamberlains and pages, were away,

And we lay in bed together, undressed,

While the torches shed light as if twere day,

“Wonder not, lady,” I her form addressed,

“If I return after but brief delay,

Whom, perchance, you thought not to find again

Before your eyes, until Heaven knows when.

I shall tell you now, why I left your side,

And then of my return you’ll hear anon.

If, for your ardour, I might have supplied

Some remedy, then I would ne’er have gone,

And in your service would have lived and died,

Nor wished to do aught but dwell, on and on,

Beside you; yet seeing how my presence

Harmed you, twas better to choose absence.

Fortune then drew me from my proper road,

And into the midst of a tangled wood,

Where I heard one call for aid, as I slowed.

Her cries echoed about the neighbourhood.

More swiftly, nigh a crystal lake, I rode,

And there I saw her, hooked amidst the flood,

A naked maiden, whom a Faun had caught,

And to devour her flesh, now, cruelly sought.

I unsheathed my sword, and ran, blade in hand

And (since naught otherwise could I do)

I slew the fisherman, where he did stand.

Beneath the water, instantly, she flew,

Then rose, and said, ‘You helped me not in vain,

And most richly will I reward you too,

With whate’er you wish, for a nymph am I;

This crystal water does my art supply.

I have the power to do wondrous things,

And can overcome the force of Nature.

Ask then; come, seek what my magic brings,

And leave to that art the form and feature.

The moon shall descend, as if on wings,

Fire I can freeze, and alter any creature,

Harden the air, and with a single word

Move the earth, or halt the sun, if preferred.’

I chose not to reply to her offer

By demanding a royal throne, or treasure,

Nor sought for greater strength nor valour,

Nor success in war and martial honour,

But only some way to sate your ardour,

For that was the reward I asked of her;

Nor sought one or another outcome there,

But left her as sole judge of the affair.

I’d scarce made my request, before I saw

Her hands dip neath the surface; her answer

She gave, yet not in speech; she turned once more,

And doused me with the enchanted water.

No sooner was I touched by that downpour,

Than I was changed (by some means or other).

I see, I feel, and yet it scarce seems true,

That, no longer female, I’m shaped anew.

Canto XXV: 65-70: And encourages her to prove his new state

And if, an unbeliever, you would prove

That such is my new state, without delay,

And that in my new sex I will remove

Every obstacle, and your needs obey,

Command that which to you will show my love

Alert, awake for you, and so alway.”

Thus, I spoke, and urged her, as I had planned,

To seek the truth revealed, with her own hand.

Like to those whose hope is lost entirely,

Not thinking to possess that which they sought,

And weep to be deprived of it, sorely,

Who grieve, and pine, and ever grow more fraught,

Yet win it; from being used so badly,

And having sown the sand that yielded naught,

They will, relieved of their desperation,

Scarce believe, possessed by consternation.

So, the lady, now, as she touched and saw,

That for which her longing had been great,

Yet scarce trusted sight or touch, still unsure,

Doubtful if she slept, and proved my state

While dreaming, seeking proof all the more

That she felt what she felt, blessed by fate.

‘God,’ she cried, ‘if I dream, let me remain

Asleep forever, and ne’er wake again!’

No sound of trumpet or of drum, withal,

Did there announce the amorous assault,

But kisses like to doves gave the signal,

To turn about, rise above, move or halt.

Other arms than arrows for the battle,

Or sling, I deployed, yet the wall did vault

Without a ladder, planted my banner

Firmly, and thrust the enemy under.

If that same bed was full, the night before,

Of deep sighs, and mortal anguish, and woe,

Now it was lightened by a greater store

Of cries of joy, sweet games, and laughters low.

The ivy clings no more tightly, I’m sure,

To the tree than did we, nor makes more

Knots than we did there, I may attest,

Ever clasping neck or arm, thigh or breast.

The thing remained a secret twixt us two,

And thus, some months it lasted, our affair,

Till, discovered, to my harm, the news flew

To the king’s ears; twas now beyond repair.

You, who freed me from the vicious crew

That sought to light my pyre in the square,

Know all the rest, yet God alone may know

The depths of my enduring pain and woe.’

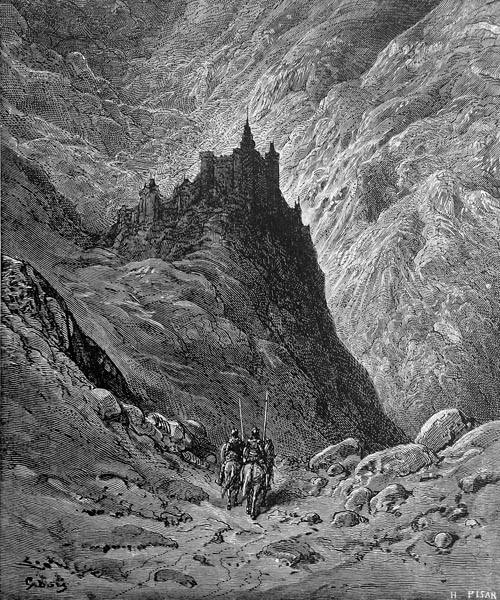

Canto XXV: 71-72: As his tale ends, they reach Agrismonte

So Ricciardetto told his woeful tale

To Ruggiero, lightening the darkness,

As they ascended that nocturnal trail,

Twixt cliffs with many a shaded recess,

A steep and narrow, and a stony, vale

The key to the heights, that granted access,

At the top, to a fortress, Agrismonte,

Held by Aldigier of Chiaramonte,

He being the bastard son of Buovo,

His brothers Viviano, Malagigi;

While those who would assert that Gherardo

Begot him lawfully, do so wrongly.

Be that the case, he e’er did wisdom show,

Strength, grace, humaneness, and courtesy.

And for the brothers, night and day, assured

The defence of the castle, as its lord.

Canto XXV: 73-76: Ruggiero learns of the capture of Viviano and Malagigi

He received his cousin Ruggiero,

Whom he loved like a brother, courteously,

And, likewise, of respect, treated him so.

Yet he welcomed him less than cheerfully,

And not as he was wont, but full of woe,

With saddened aspect, troubled inwardly;

For he’d received ill news, that very day,

That concerned him, far more than he could say.

Now, in exchange for his cousin’s greeting

He said: ‘Cousin, I have sad news indeed,

By a sure messenger the tale receiving.

Bertolagi of Bayonne has agreed

To yield gold to Lanfusa, she granting

(Ferrau’s cruel mother) for that same deed,

Him power over my two brothers so,

Good Malagigi and Viviano.

She’s held them in a dark and noisome place,

From the day Ferrau captured them, until

This pact the Maganzese’s seal did grace;

And, intending to keep the bargain still,

Tomorrow the evil pair will embrace

Twixt Bayonne and his castle, where he will

The reward for her wickedness advance,

So, purchasing the truest blood in France.

A messenger is, even now, hastening

To advise our Rinaldo of their plight.

But, given the distance he is travelling,

He’ll prove too late in reaching the knight.

I lack resources to address this thing,

The spirit willing, yet the strength but slight.

If the traitor acquires them, they will die,

Nor know I how that deed I might deny.’

Canto XXV: 77-80: He proposes that that they free the brothers

The tragic news saddened Ricciardetto,

As it did him, and Ruggiero likewise,

Who when he saw them silent, full of woe,

And unable some sound scheme to devise,

Exclaimed, with strength and ardour: ‘Grieve not so;

To me shall fall this whole fair enterprise;

This sword will be worth a thousand men.

I shall grant them their liberty, again.

I ask no other men, nor other aid;

I think my own strength equal to the deed.

I seek naught but a guide, one not afraid

To lead me to the place they have agreed.

And when with me tis blows that they must trade,

You’ll hear their cries as the villains bleed.’

So, he ended, claiming naught that was new

To one who had witnessed his own rescue.

The other listened only as one might

To those who speak a lot, yet do little,

But Ricciardetto did their host invite,

To hear the tale of the earlier battle,

And how he was saved, and said the knight

Would make his statement good; for his mettle

He would prove at the proper time and place.

Aldigier then showed him fitting grace.

At table, where Plenty dowered all three,

He honoured him as if he were his lord,

And agreed the brothers might be set free,

Without other aid; thus, all were in accord.

Then came the time when Sleep, languidly,

Closed their eyes, and repose did them afford.

All save Ruggiero, troubled by a thought,

That pricked his conscience sore, as ease he sought.

Canto XXV: 81-85: He agonises over his delay

That Agramante was besieged, he knew

From his summons, and had taken it to heart.

He saw the least delay that might ensue

In yielding aid dishonoured him in part.

What infamy, what shame would fall anew,

On a knight that from his king stood apart!

How great the crime that must be realised;

And charged to him, if he were now baptised!

It might be believed, at a later date,

That he’d been moved by religious feeling,

But now his aid was needed ere too late,

To relieve his true master and his king.

Twas more likely that others would relate

His tale as that of some craven being,

Rather than as witnessing his belief.

It pricked his heart, and brought no little grief.

Then it stung him that he’d quit his lady,

Without her leave, and she now all alone.

To this thought now, and that, piercing deeply,

He turned his mind, wherein much doubt was sown.

He’d looked about for her, yet fruitlessly,

At Fiordispina’s castle, I should own,

Where, as I’ve said, they had gone, together,

To rescue Ricciardetto, her brother.

Then he recalled the promise he’d made her,

To meet at Vallombrosa’s sanctuary,

Thinking, now, she must have travelled thither,

And be wondering where her lover might be.

He could at least send the maid a letter,

So that she be not worried, needlessly,

Given he’d not merely disobeyed her,

But without a word had parted from her.

Once his imagination ceased to stir,

He decided to write, without delay;

And though he was unsure in what manner

He might yet send the missive on its way

So as to reach her, some sure messenger

He hoped to find as soon as it was day.

Malingering no more, up leapt the knight,

And called for pen, ink, paper and a light.

Canto XXV: 86-91: He writes to Bradamante

Thus, the attentive servants of his host,

Brought Ruggiero all he requested;

He began to write his screed, and foremost

Greeted her, as courtesy suggested,

Then told how Agramante had utmost

Need of his help, being sorely tested,

And that if he did not soon go to his aid,

His king would be slain or a captive made.

Then added that him being in that state,

And turning to him for aid and succour,

She must see that shame would be his fate,

If he were to refuse, and dishonour.

And since she was about to be his mate,

He must guard himself from every error,

For it was wrong that aught ill should appear

Near her, where all was pure and sincere.

And since he’d laboured to keep his name

Clear of all taint, done so, and held it dear,

And sought to keep it so, that very same,

He kept it now, as with a miser’s fear,

That she might bear that emblem without shame,

For she as his dear wife would soon appear,

And, though a separate body, ought to be

At one with him, in spirit, endlessly.

And as, in speech, he had explained before,

And now would set down here in his letter,

When e’er his service to his king was o’er,

Unless he were to die, he assured her

He’d be a Christian, her god adore,

As was e’er his wish, and so forever.

And of her father, and Rinaldo, in this life,

Ask no more than that she should be his wife.

‘I would,’ he wrote, ‘by your good leave, help raise

This siege of King Agramante’s army,

So that the vulgar crowd might grant me praise

Rather than pour shame and scorn upon me,

Saying that while their king felt Fortune’s rays,

Ruggiero was at his side, endlessly,

But now that she to Charlemagne has fled,

He flies his flag for the victor, instead.

I ask for a mere twenty days, or less,

So that I might take to the field once more,

And help the army to win fresh success,

And free them from the siege they now endure.

Meanwhile, I’ll seek just reason to address

My change of creed, and baptism ensure.

I, of my honour, make this sole request,

Then my whole life is yours, I, here, attest.’

Canto XXV: 92-97: The cousins set out to free the brothers

In like words Ruggiero then expressed

Himself the more, nor could I tell you all;

Many a word he wrote, and could not rest,

Until the sheet was filled with his fair scrawl.

Then the letter he sealed, and at his breast

Concealed it, lest some harm to it befall,

Hoping to find next morn, upon the way,

One that, to the maid, might his screed convey.

Having brought all to a close, with weary eyes,

To bed he went, and found peace thereafter;

For Sleep now came, and sprinkled, from the skies,

Dew from some branch wet with Lethe’s water.

He slept, till the white and red of sunrise

Appeared and, scattering flowers, fair Aurora,

Filled the east with her colourful display,

As from her gilded house, she brought the day.

Then, as the birds hailed the returning light,

Amidst the greenwood, joying in the dawn,

Aldigier (who sought to guide the knight

And his cousin, as they set out, that morn,

Eager to save the brothers, and to fight

Bertolagi, for his sake, as they had sworn)

Was first upon his feet; and then the two

Arose, on hearing him, and armed anew.

And once they were in armour fresh arrayed,

Ruggiero, with his cousins, took his way,

Though as we know, he had already prayed

That the adventure with himself should stay;

Yet they, by love of those two brothers swayed,

Believed it shameful simply to obey,

And denied his plea, as if made of stone,

Not consenting that he should go alone.

They reached the place at the time proposed

For Lanfusa’s exchange with Bertolagi.

It was an open tract of land exposed

To Apollo’s rays; all that barren country,

Neither myrtle nor laurel scrub disclosed,

Nor beech, cypress, ash, for all lay empty;

Twas but naked gravel, and humble weed,

Where none had ever ploughed, or scattered seed.

The trio of brave warriors halted there,

Where a wide track ran o’er the silent plain,

While at a knight, who towards them did fare,

They gazed, his armour all with gold o’er-lain.

His emblem, on a green field, was the rare

Phoenix, that for an age or so doth reign.

Yet, no more; for the end of this, my canto,

I perceive here and rest, too, I would know.

The End of Canto XXV of ‘Orlando Furioso’