Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXIV: Zerbino's Fate

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXIV: 1-3: Love is a madness

- Canto XXIV: 4-7: Orlando attacks the shepherds in his frenzy

- Canto XXIV: 8-12: Then turns upon the farmers

- Canto XXIV: 13-14: He roams France and reaches a lonely tower

- Canto XXIV: 15-19: We return to Zerbino and Isabella

- Canto XXIV: 20-28: Almonio tells the tale of Odorico’s capture

- Canto XXIV: 29-32: Odorico offer his excuse

- Canto XXIV: 33-37: As Zerbino considers his punishment, Gabrina appears

- Canto XXIV: 38-45: The ultimate fate of the treacherous pair

- Canto XXIV: 46-50: Searching for Orlando, Zerbino finds the cave

- Canto XXIV: 51-57: They gather Orlando’s gear, and meet with Fiordelisa

- Canto XXIV: 58-62: Mandricardo seizes the sword Durindana

- Canto XXIV: 63-67: They fight and Zerbino is lightly hurt

- Canto XXIV: 68-70: But then receives further wounds

- Canto XXIV: 71-74: Isabella seeks Doralice’s aid and the fight is ended

- Canto XXIV: 75-85: The death of Zerbino

- Canto XXIV: 86-93: Isabella aided by a hermit transports Zerbino’s body

- Canto XXIV: 94-96: We return to Mandricardo, who encounters Rodomonte

- Canto XXIV: 97-107: They fight, the outcome uncertain

- Canto XXIV: 108-115: They are summoned to Paris, so make peace

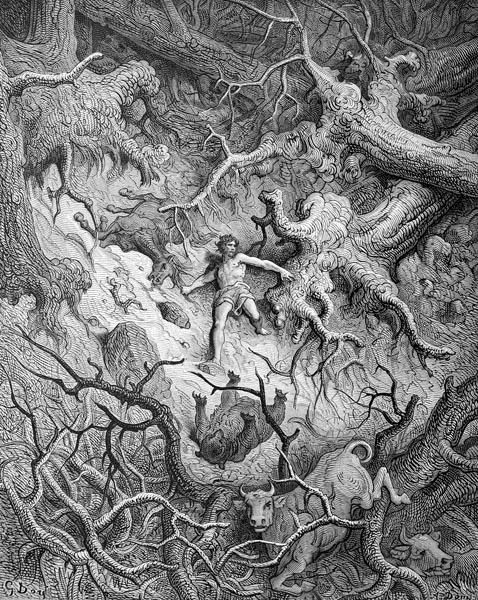

Canto XXIV: 1-3: Love is a madness

He that sets claws upon the bait of love,

Let him not lime his wings, but realise

Love is mere madness that our hearts doth move,

In the combined judgement of the wise.

And if some, calmer than Orlando, prove,

Their folly shows but in some other guise.

For what sign of madness could be clearer,

Than to wish to lose oneself in another?

Its effects are various, but madness

Is ever the common source of all.

Tis like a great forest, at whose ingress,

The traveller’s way is lost beyond recall;

To and fro, and up and down, his progress

Non-existent; so, I say to you, in thrall,

He who grows old in love, beyond his pain,

Well deserves iron fetters and a chain.

You might well say: ‘Brother, there you go,

Advising others, to your own faults blind.’

I reply that I can see the madness though,

In the lucid moments fate grants my mind,

And strive and hope, that I may yet forego

The dance of folly, and some peace may find.

Yet twill not be as soon as I desire,

For to my very marrow sinks the fire.

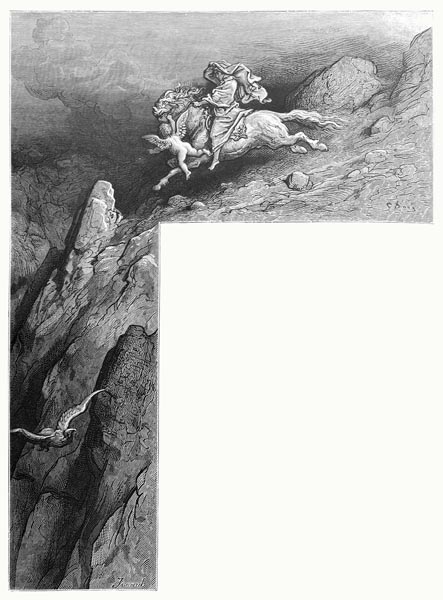

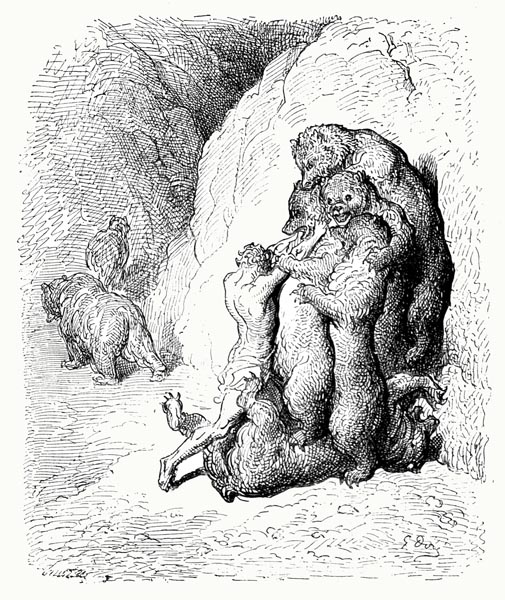

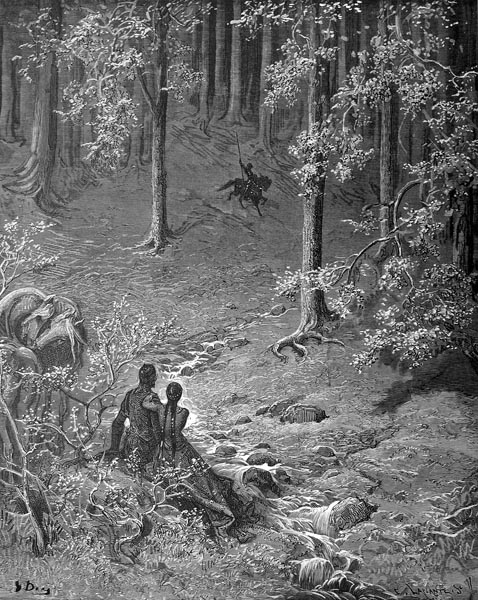

Canto XXIV: 4-7: Orlando attacks the shepherds in his frenzy

In the previous canto, I have told you

How the frenzied, insensate Orlando

Tore off his armour, and its pieces threw

About the woods, and shed his sword also,

Uprooting trees, while echoes rose anew

From forest heights, and stony caves below,

Till their past sins, or fateful planets, drove

Nearby shepherds to that noise in the grove.

On a closer view of this wild display,

And the extremes of strength Orlando showed,

They turned to flee, every and which way,

As men do, in fear, careless of their road;

For the madman seemed at their back alway.

So he was; and he caught them when they slowed.

Plucking off a shepherd’s head, as one might

An apple from the branch, or blossom bright.

By a leg, he lifted one’s weighty mass,

And of him made a mace to strike the rest;

He stretched a pair, in a trice, on the grass,

To awake on the last day, midst the blessed.

The others, more alert, from there did pass,

(Or much fleeter of foot, when sorely pressed);

The madman would soon have followed too,

Had he not chosen their flocks to pursue.

The farmers, now warned by their example,

Abandoned every scythe, and hoe, and plough,

And made for the roof of house, or temple,

For unsafe proved the elm or willow bough,

And from there, they watched the madman trample

All about, and with kicks, bites, blows endow

All creatures; cattle, horses were his prey;

Swift was the courser that escaped that day.

Canto XXIV: 8-12: Then turns upon the farmers

You might have heard the clamour, already,

Rise in the air, from all the farms nearby,

Horns and rustic trumpets, notes unsteady,

And the bells, ringing loudly, from on high.

With pikes, and bows, and slings, at the ready,

A thousand rustics gave their battle-cry.

From the hills, with as many from the vale,

They charged, the vicious madman to assail.

As a wave will tumble on the briny shore,

Raised, at first, by a playful southerly,

But then a second greater than before,

Precedes a third, breaking yet more fiercely,

As the waxing gale rises evermore,

And lashes the sands, roaring loudly,

So, the growing crowd attacked Orlando,

From the hills above, and the dale below.

He slew ten farmers, then another ten,

That, in scattered groups, fell to his strong hand,

And their example taught the other men

To choose a safer place to make their stand.

And none drew blood from him, but then again

His skin was tough as steel, you understand;

As a guardian of the holy faith, the Lord

Such protection to that knight did afford.

Orlando would indeed have been in danger,

If he’d not been equipped with such defence;

He might have learned that quitting his armour

And his sword, was unnecessary expense;

But the crowd retreated, without honour,

Since his hide was too steely, or too dense;

And Orlando, as no other sought renown,

Made his way, now, to the neighbouring town.

Since the citizens had fled the place in fear,

He found not a soul there, great or small,

But copious stores of food, far and near,

Suiting the rustic palates of them all;

And bread from ground-up acorns is as dear

To a man as aught else, in hunger’s thrall.

And so, he there employed his hands and jaws

On whatever he found, with scarce a pause.

Canto XXIV: 13-14: He roams France and reaches a lonely tower

From thence, he roved about that country

Hunting down every creature that he saw,

Scouring the woods and fields, in his frenzy,

Slaying now a deer, a goat, whate’er they bore.

Oft a bear or wild pig, he would harry,

And with his bare hands their deaths ensure;

Gorging on the flesh, and hide, and all,

Of whatever living things to him might fall.

He roamed up and down the land, far and wide,

Through the whole of France, and came one day

To a bridge, beneath which the stream did glide;

Twixt steep and slippery banks, its flow did stray.

And there a tower could be seen, from every side,

A turret built for strength, and not display.

What he did there, you shall hear elsewhere,

For Prince Zerbino is my present care.

Canto XXIV: 15-19: We return to Zerbino and Isabella

The prince, once Orlando had departed,

Stayed a little while, then made his way

By the road, down which the Count had started;

With Isabella, slowly, onwards then did stray.

Yet not two miles of the road had they charted,

When a knight, tightly bound, met their survey;

Upon a sorry nag, the man was tied,

Accompanied by a guard, on either side.

The prince soon recognised their prisoner,

As did Isabella, once they’d drawn near,

Twas Odorico of Biscay, who earlier

Had been appointed her guardian, I fear,

Like a wolf o’er a lamb, for his master

Zerbino, as a friend, had held him dear,

And confided the lady to his care,

Trusting his loyalty, in that affair.

As it chanced, the maid had been relating

The tale of what had happened, as they rode:

How she was rescued, the ship forsaking,

Ere it sank in the sea, with all its load;

Then the assault of Odorico’s making;

And how the robbers, in a cave, had bestowed

Her, as their captive; and her whole story

Was not yet done, ere they met that party.

The two that had hold of Odorico,

In turn had recognised Isabella,

And, therefore, concluded twas Zerbino,

Beside her, now her lord and her lover.

More, the emblems on his shield did show

His noble ancestry, his House, and further,

As they, more closely, observed his face,

They decided they’d rightly judged his place.

Dismounting, with open arms, they ran

To embrace her lord, and clasped Zerbino

Where a lord is embraced by his man,

On bended knee, and their bared heads did show.

Corebo of Biscay he knew; his scan,

Of the other, revealed Almonio,

Both of them he’d commanded, as well

As Odorico, to the charge of that vessel.

Canto XXIV: 20-28: Almonio tells the tale of Odorico’s capture

‘Since God is pleased, of His great mercy,

That Isabella should be here with you,’

Said Almonio, ‘my lord, my tale, clearly,

Would scarce be news, were I to tell anew

Why I lead this captive along with me,

The very worst of the worst, in my view,

For she who has endured the most offence,

Will have told the tale, ere you came hence.

Thus, how the traitor fooled me you know,

When he left me behind; and of the harm

That was suffered by our friend Corebo,

He that sought to keep the maid from alarm.

But that which followed she cannot know,

On my return, an, though with far less charm,

I shall tell of the things she did not see,

And so, reveal the rest of the story.

From the town to the shore I came, swiftly,

With the string of horses that I had found,

And, once there, looked carefully about me,

For those I’d left behind, gazed all around,

And advanced to where not far from the sea

I’d seen them last, twas unpeopled ground,

Except that, as I rode along the strand,

I found a trail of footprints in the sand.

Following those tracks, they soon led me

Into the wild wood; in a yard or two,

Sounds struck my ears, and advancing quickly,

My wounded comrade came within my view.

I asked what had become of the lady,

And Odorico, and of his wounding too,

And once he’d exhausted the matter,

I searched amidst the cliffs for the traitor.

I rode about the shore, went to and fro,

But found no further trace of the pair.

And so, at length, returned to Corebo,

With the ground all about him, bloodied there.

And had I waited longer ere I did so,

He’d have needed a grave, and a prayer

From a priest, not a bed and a doctor,

Blessed with the soothing hands of a healer.

I had him borne to the town, from the shore,

And lodged with a kindly host, I knew,

And there a skilful surgeon found the cure

For his ills, and restored our friend anew;

Then provided with a horse, arms and more,

We next searched for Odorico, we two,

And found him hiding at Alfonso’ court,

Where I challenged the man, and so we fought.

The monarch’s justice (for he granted me

Both true and level ground on which to fight)

And my cause (that was Fortune’s cause clearly,

She who grants victory, as she thinks right)

So aided, that the wretch was readily

Defeated, and surrendered to my might.

Alfonso, once the crime had been confessed,

Left me to deal with him as I thought best.

I neither wished to leave him or to slay

The wretch, so have led him, thus, by a chain,

All that you might judge him, on a day,

And say if he should die or live, in pain.

Hoping to find you, forth I took my way,

On hearing that you fought for Charlemagne,

And now, my thanks to God, I have found you,

Both where, and when, I least thought so to do,

And give thanks too, that your Isabella,

Is here, present at your side as before,

Of whom, all due to this evil traitor,

I thought not to hear news evermore.’

Zerbino, gave ear to the narrator,

In silence (Odorico’s fear he saw)

Yet not in hatred, saddened by the end,

Of past amity, pitying his friend.

Canto XXIV: 29-32: Odorico offer his excuse

When Almonio had finished his tale,

The prince stood awhile, astounded that one

That had the least cause a friend to assail

Had proved treacherous, with little reason.

Yet, though long amazement did prevail,

He sighed, at last, at what the man had done,

And asked Odorico if all was true

That the knight had said. Without more ado,

The traitor dismounted and, on his knees,

Answered: ‘All folk that live on earth, my lord,

Err and sin, slaves to their infirmities;

Nor does the world a happier view afford,

Except that, while ill wins its victories

Because the ‘sinner’ doth a path accord

To desire, yielding to that stronger foe,

The ‘good’ a sound defence do ever show.

If you had set me to defend a fort,

And at the first attack I’d raised, on high,

Some hostile banner, my loyalty bought,

Or through cowardice or treason, then I

Had but deserved my fate, if you had sought

To hide me in some cell far from your eye;

But, yielding to a greater force, I say

I should not be blamed, but praised alway.

If the enemy proves the stronger,

The loser ever has a fair excuse;

I kept faith, as one the foe doth ever

Besiege, a fort he seeks for his own use,

Thus, all the wit and sense I could gather

That Providence, at birth, did introduce

To my poor being, I essayed to wield,

But, at last, to a greater force did yield.’

Canto XXIV: 33-37: As Zerbino considers his punishment, Gabrina appears

So said Odorico, then added more,

(In a speech too long to recount it here)

To show how great the urge that went before

His deed, how fierce the flame that did sear.

And if ever prayer might clemency assure,

If ever humble speech might error clear,

It must have done so then; all that might melt

The hard heart, in words, Odorico spelt.

Whether to now avenge his infamy,

Twixt ‘yea’ and ‘nay’, Zerbino hovered;

Reviewing the crime’s enormity,

He was inclined to see the villain dead;

But then their friendship and the memory

Of long accustomed loyalty, instead,

Cooled his anger, with the dew of mercy,

And tempted him to spare the man, in pity.

With Zerbino thus in a quandary,

Whether to hold him, or set him free,

Or remove him from his sight, quickly,

Doom him to die, or live on painfully.

That very steed appeared, neighing loudly,

Whose bridle Mandricardo, forcefully,

Had snatched away, as the old crone it bore,

That had nigh caused Zerbino’s death, before.

The palfrey, that the others there had heard

Afar, thither Gabrina now conveyed,

That came weeping, though in vain; every word

She uttered, seemingly, a cry for aid.

Zerbino with the skies above conferred,

And, hands raised, thanked them for the gift so made,

Of deciding her and Odorico’s fate,

Those whom he had the truest right to hate.

Zerbino held her captive while he thought

What might offer the fittest punishment;

To remove her nose and ears, so he ought,

As an example; or perchance rest content

With condemning her to the vultures’ court,

And letting them be judge of what he sent.

He considered these various fates a while,

And then resolved the matter, in this style:

Canto XXIV: 38-45: The ultimate fate of the treacherous pair

He turned to the company, and declared:

‘I am content to grant the man his freedom.

Though he merits not being wholly spared,

Death is not deserved; he has my pardon,

Inasmuch as, though the traitor has erred,

Twas Love that made him do as he has done,

And all excuses we must readily accept

When on Love himself the guilt doth reflect.

For Love will oft turn all things upside-down,

And has overturned stronger minds than his;

Love renders many a sober man a clown,

To outrage us, far more so than did this.

For Odorico pardon, mine the crown

Of sad misjudgement and utter blindness,

In granting him my trust yet minding not

That fire burns straw, such is our common lot.’

Gazing at him, he uttered his decree:

‘This is the punishment for your offence.

You must endure this woman’s company

For one whole year; with her you’ll travel hence,

At your side, day and night, where’er you be,

Nor shall you quit her on the least pretence,

And must at all times prove her defender,

Against any who would seek to harm her.

And, if this woman, here, doth so command,

You must take up arms against whatever

Armed warrior you may meet; through this land,

Of France, I so order you to wander.’

So, he spoke. While, deserving, at his hand,

To die, for his attempt on Isabella,

Odorico now faced a deep dark pit,

And would do well indeed to escape it.

The crone had so many men and women

Betrayed, and had offended so many

That whoever accompanied her, then,

Could ne’er pass by a knight-at-arms freely.

Both would be punished thus, time and again,

She, for the deeds that she’d wrought vilely,

And he because he must those crimes defend;

Nor would he go far, ere he met his end.

Zerbino made him swear to keep the pact,

And a mighty oath Odorico swore,

That if he broke his pledge by any act,

And were brought before the prince’s face once more,

Without prayer or mercy, twas a fact,

A cruel death he’d die, such was the law.

Then to Almonio and Corebo,

He turned, that they might free Odorico.

Corebo, with Almonio’s consent,

Freed the traitor, at last, though tardily,

For both the prince’s mercy did resent,

Who’d seemed to thwart revenge entirely.

Thus, the traitor, on his way, swiftly went

With Gabrina at his side for company.

Of them, Bishop Turpin said naught further,

Yet I’ve found more, in another author.

This author said (I shall not give his name)

That they were not a day on their journey

Ere Odorico, indifferent to blame,

Broke the pact, threw a rope o’er an elm tree,

Tied a noose about her neck, with that same,

And left her suspended, swinging freely;

While, within a year, careless of his cries,

Almonio served the traitor likewise.

Canto XXIV: 46-50: Searching for Orlando, Zerbino finds the cave

Zerbino, who had followed Orlando,

And was loth to lose all trace of the knight,

Sent news of his state to his troops, so

As to quell their doubts of his health, outright.

With the missive, he sent Almonio,

Its contents far too long to here indite;

And then, after him, Corebo did ride,

Leaving only Isabella at his side.

So great was his respect for Orlando,

No less than his love for Isabella,

That (regarding the Tartar, Mandricardo)

He longed to find the Count and discover

If he’d met the infidel, who’d downed him so,

And left him, and his saddle, in some bother.

He, therefore, his return to camp, delayed.

For three days, thus, patiently, they stayed;

For that was the term set by Orlando,

To wait for the sword-less knight to appear,

While all about the woods rode Zerbino,

Where’er the Count had gone, far and near,

And, at last, to that place, came riding slow,

Where the names were carved, deep and clear,

Of Angelica and her love, Medoro.

And there, the fountain and the rocks he found

In disorder, and ruin all around.

Not far from him, lay something bright;

Twas Orlando’s breastplate, on the ground,

And then his helm, gleaming in the light,

But not that which Almonte’s head had crowned;

He heard a neighing steed, that of the knight,

In the wood, and raised his head at the sound,

And saw Brigliadoro grazing there,

With his rein hanging loosely in the air.

Then he searched for the sword, Durindana,

And found it, far apart from its sheath,

With pieces of the surcoat, a scatter,

A hundred fragments, in the trees and beneath.

Grieving now, the prince and Isabella

Stood, and gazed on the woodlands and the heath,

They knew not what to think; not, certainly,

That the Count’s mind might be lost to frenzy;

Canto XXIV: 51-57: They gather Orlando’s gear, and meet with Fiordelisa

Had they but seen a single drop of blood,

They might well have believed that he was dead.

But a shepherd appeared, between the wood

And the water, one that seemed pale with dread.

Not long before, where, on a hill, he’d stood,

He’d seen the madman’s fury, who had shed

His clothes, and once rid of arms and armour,

Had caused havoc, slaying many a farmer.

The shepherd, when questioned by Zerbino,

Gave them a true account of all he’d seen.

The prince scarce believed it of Orlando,

Though the traces clearly showed what had been.

He dismounted, on the plain, even so,

Full of pity, with sad and troubled mien,

And went about gathering all he found

Of Orlando’s gear, scattered on the ground;

Isabella also, now, descended,

And gathered all the things she could find.

Behold, a maiden towards them wended,

Sad of face, and seeming troubled in mind.

If you ask why many a sigh she expended,

Why she sorrowed, as if to grief resigned,

I reply that the maid was Fiordelisa,

That came seeking traces of her lover.

Brandimarte had left her at the court

Of King Charlemagne; all without a word,

For eight months, she’d awaited a report

Of her knight, yet no news of him was heard.

From the Alps, to the Pyrenees, she’d sought,

From sea to sea, and had much pain incurred.

In every place she’d looked for her lover,

Except the mansion of the enchanter.

If she’d entered that house of Atlante,

She’d have found the knight there, with Gradasso,

With Ruggiero, and Bradamante,

Wandering, with Ferrau and Orlando,

But when Astolfo blew his horn loudly,

And chased the wizard forth, he did go,

Brandimarte, once more, straight to Paris,

Though Fiordelisa had known naught of this.

As I say, it was by chance Fiordelisa

Encountered the lovers searching there.

She knew Brigliadoro, the armour,

And the sword and, gazing everywhere,

Explored the relics of the mad endeavour,

While hearing all the story from that pair,

As told by the shepherd, who had seen

Orlando, running frenzied midst the scene.

Zerbino had brought the things together,

And hung, them like a trophy, from a pine;

And, to preserve them from some traveller,

Native or foreign, carved a single line

In the bark of the tree, for every reader:

‘Orlando’s arms and armour, and not thine’

As if to say, let none to greed now yield,

That dare not meet Orlando in the field.

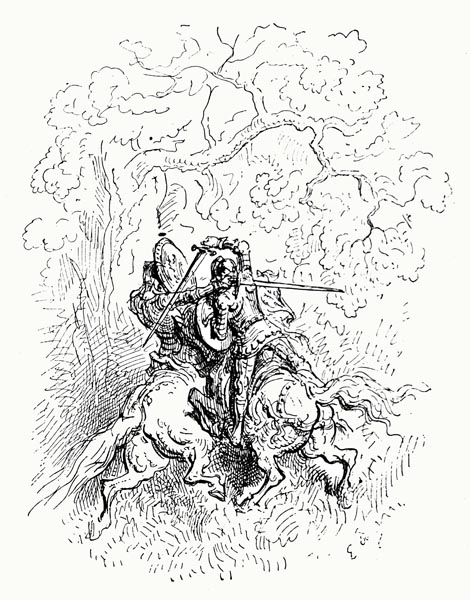

Canto XXIV: 58-62: Mandricardo seizes the sword Durindana

On completing this praiseworthy deed,

Zerbino was mounting his horse, once more,

When, behold, Mandricardo came at speed

O’er the plain, fast approached, and there he saw

What hung from the pine; and set to read,

And next sought to know what had gone before.

Then, pleased by what he heard, the Tartar lord,

Hastened to the pine-tree, and seized the sword,

Saying: ‘None shall take this weapon from me;

Before today, this sword I held as mine,

To be claimed as my possession, rightly,

Whene’er, where’er, its presence I divine.

Orlando who fears to meet me, clearly,

Is quite maddened, and does the sword resign;

And if madness is claimed as his excuse

Tis no reason not to put the thing to use.’

‘Yet, take not the weapon,’ Zerbino cried,

‘Or think to have unchallenged possession.

Though you wear Hector’s armour, in your pride,

Tis by theft you gained it, without question.’

And, without further words on either side,

They met, with equal skill and aggression.

While ere they were yet deeply engaged,

A hundred echoes sounded, as they raged.

Zerbino seemed a flickering flame in flight,

As he twisted to evade Durindana,

Leaping, like to a deer, amidst the fight,

Wherever the footing looked the firmer.

And well that he gave not an inch, the knight,

For, if that great sword had touched him ever,

He’d have joined the enamoured shades that rove

Amidst the shadows of the myrtle grove.

As the sure-footed hound that finds a boar,

Wandering from its kind, and far afield,

Now circles round it, now in air will soar,

While the fierce creature waits its tusks to wield,

So, the weapon rose, behind and before,

While Zerbino watched, nor his ground did yield,

Seeking to preserve both life and honour,

Smiting when he could, but fleeing never.

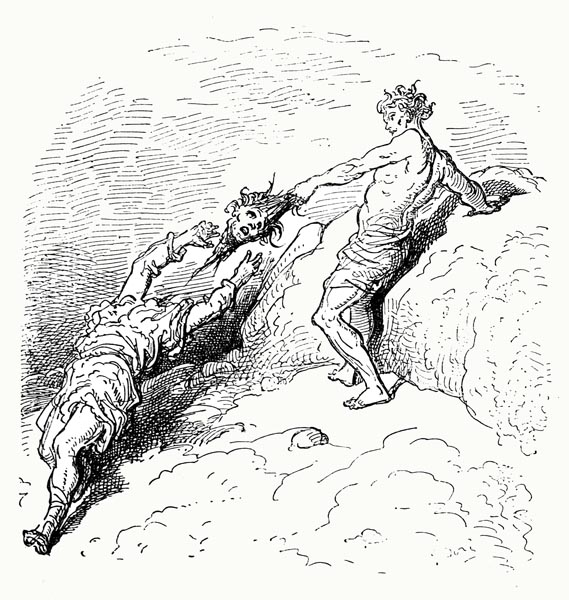

Canto XXIV: 63-67: They fight and Zerbino is lightly hurt

On the other side, where the Tartar king

Landed, now and then, an almighty blow,

He seemed much like an Alpine gale raging,

That shakes, in March, all the woods below,

That now, to the ground, their summits bending,

Now shedding branches, must endure it so.

Though Zerbino scaped many, in the end

Came a blow gainst which no man could defend.

He failed to evade the descending sword,

That struck upon his chest, twixt blade and shield.

Through breastplate, and corselet, it bored;

Though the steel was dense, it could but yield.

Then the cruel weapon sliced and scored

All down his front, skin and flesh now revealed,

As it cut right through the armour, and fell

To the saddle-bow, which it then cleft, as well.

Were it not that the blow fell somewhat short,

It would have split Zerbino like a cane,

But it scarcely penetrated, piercing naught

But the skin, and brought him less harm than pain.

The wound was a span in length, but brought

No greater damage to the knight, in its train,

Than staining the steel with a line of blood,

That dripped to the earth, in a crimson flood.

Thus, do I see a vermilion ribbon

Betwixt a silver sleeve and a hand

Seeming as white as pure alabaster,

And feel my heart split open where I stand.

Little did his great skill serve its master,

Nor the strength and ardour, at his command.

In the temper of his blade, and his power,

The Tartar king was the ruler of the hour.

Though the blow was, in reality,

Far greater in appearance than effect,

Poor Isabella felt the stroke deeply,

As if upon her heart it fell direct,

Zerbino, full of ardour, answered swiftly,

Inflamed with anger and, swinging unchecked,

With a two-handed blow from his sharp sword,

Upon the helm he struck the pagan lord.

Canto XXIV: 68-70: But then receives further wounds

The proud Tartar knight was thus forced to bow

His neck, and lower his face towards his steed.

Had the helm not been enchanted, I vow

His head had been split; and yet fate decreed

That the king would have revenge; even now,

He raised the sword, as he wheeled at speed,

Thinking not: ‘Leave it, for another season,’

But intending to cleave Zerbino’s person.

Zerbino, his mind in tune with his eye,

Now wheeled his mount swiftly, to the right,

But not so quickly that they could outfly

Durindana, that struck his shield outright,

Dividing it, top to bottom, cleanly,

Cutting the sleeve beneath it, while the knight

Felt the blow on his arm; rent the harness;

And descended to bruise his thigh, no less.

The prince sought every way that he could

To achieve his end, but to no avail,

For while he struck the armour as he would,

It escaped all marks, all dints, without fail;

On the other hand, the Tartar, who’d withstood

Every blow, now began to prevail,

Wounding him often, and sought to overwhelm,

The knight, denting his shield, and half his helm.

Canto XXIV: 71-74: Isabella seeks Doralice’s aid and the fight is ended

Zerbino was losing both strength and blood,

Though he seemed to feel it not, twould appear;

His vigorous heart yet the pain withstood,

And sustained the body of the cavalier.

Isabella, who’d turned pale where she stood,

Ran towards Doralice, then drew near,

And, for the love of God above, prayed her

To halt that fierce contest, then or never.

Doralice, courteous as she was fair,

All uncertain how the matter would end,

Willingly granted Isabella’s prayer,

And requested peace of her martial friend,

While Zerbino was persuaded by the other,

To calm himself, and to her pleading bend;

And so, they took to the road, sans discord,

Forgoing now the business of the sword.

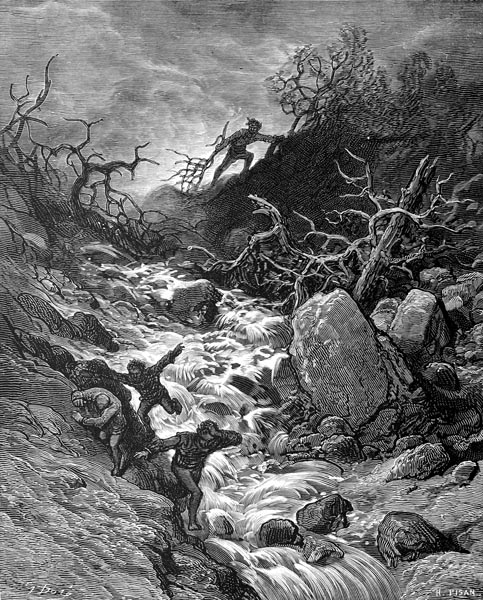

Meanwhile, Fiordelisa who decried

The abandonment of Orlando’s blade,

Grieved wordlessly, though angrily she sighed,

And wept bitter tears in the woodland glade.

She wanted Brandimarte by her side,

Who, once found, and all the tale relayed,

Would, she believed, seek out Mandricardo,

That but a brief while the sword must know.

She enquired for Brandimarte, but in vain.

From morn to eve, and now she wandered,

Far from that knight, who did his path maintain

To Paris, where he, equally, was wanted.

So far, she went, o’er mountain height, and plain,

That soon a river passage she adventured,

Where she met with the wretched Orlando.

Yet first I’ll say what happened to Zerbino.

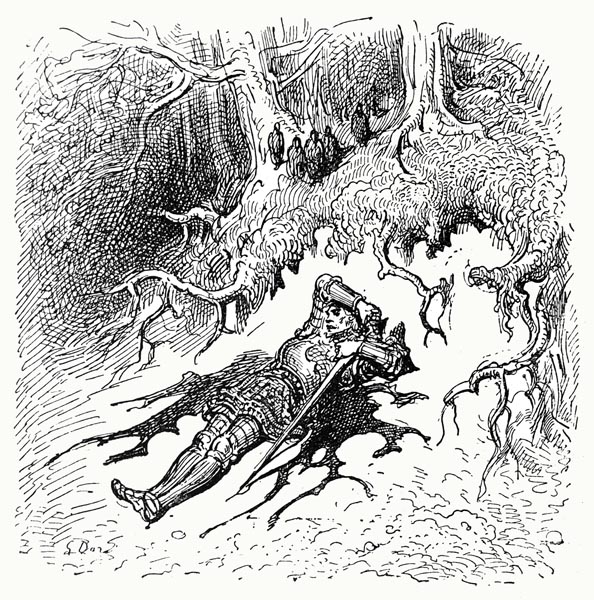

Canto XXIV: 75-85: The death of Zerbino

So great a fault it seemed to him to leave

Durindana, it surpassed every ill,

Yet could scarce ride a horse, you may conceive,

Since the blood was seeping from him still.

And the pain of his wounds made him grieve,

As his ardour ebbed, and his strength of will;

So swiftly was his anguish increasing,

As it deepened, he felt his life departing,

He could no longer stir, such his weakness;

Near the fountain he was forced to remain.

Isabella gave thought, with scant success,

To how she might yet aid him, in his pain.

She thought him dying of his sore distress;

All help lay far away, beyond the plain,

Every township where a surgeon might dwell,

That would, for gold or pity, make him well.

She knew not whether in vain she grieved,

Calling on heaven, and the cruel sky:

‘Why was I not drowned, as he believed,

When my vessel was wrecked?’ such was her cry.

Zerbino, whose languid gaze she received,

Felt greater pain at each complaint and sigh

Than the strong and fierce anguish that he felt,

Which the rapid advance of death now spelt.

‘Promise me, truly, my dear heart’ he cried,

‘That you will love me still when I am gone.

To leave you now alone, without a guide,

Renders me distraught and I grieve thereon.

Were I a safer refuge not, thus, denied,

Where I might end my life, my journey done,

I’d be content to die, and thus to rest

Most fortunate, indeed, upon your breast.

But since my fate, cruel in its harshness,

Forces me to leave you, and with whom

I know not, I swear by those lips, no less,

Those eyes, that hair that ever spelt my doom,

(I, whose spirit into the darkened depths,

Of hell must go) the thought, amidst the gloom,

Of abandoning you, will assail me

More than all else, and ever more fiercely.’

At this, Isabella, sorrowing,

Bowed down her moistened face, in tearful pose,

Her lips with Zerbino’s conjoining,

He who seemed now as languid as a rose

Gathered out of season, swiftly fading,

From the shadowy hedgerow where it grows,

And said: ‘My life, oh, think not to depart,

On this last journey, without your true heart.

Of that, my love, you need possess no fear,

For to heaven or to hell, I’ll follow you,

Tis right that both together quit this sphere,

One with the other, ever one not two.

No sooner shall your eyelids close, my dear,

Than either grief will kill me (tis your due)

Or, if my sorrow has not power to slay,

The sword’s a means to end this life today.

I cherish no small hope that, being dead,

Our bodies shall meet a happier fate.

Moved by pity, some kind soul may be led

But a single tomb for both to create.’

As she spoke, from his lips she yet gathered

The last living breath, ere it was too late,

Collecting on her lips, that could but sigh,

The final thoughts of one about to die.

For his faint voice strengthened a moment:

‘My living deity, I beg, and pray,

By the love you showed me, and intent,

In forsaking your father’s home that day,

And command you (if I may), but consent,

While it yet pleases God above, to stay

Alive, for me, and to this thought be true:

I, in all ways I could, have so loved you.

God will, of His great mercy, grant you aid,

And keep you free from all vile oppression,

As when Orlando his powers displayed,

In rescuing you from the robbers’ cavern.

God saved you, when to that shore conveyed

From the waves; He foiled the vile Biscayan.

Should you seek death, in dire extremity,

Yet ever the lesser evil let it be.’

I believe his last words were not expressed

With voice enough that he was understood;

He died, like a taper no longer blessed

With wax enough to brighten as it should.

Who could relate how pale and distressed,

The maid became? None but a lover could.

For her Zerbino, with pale and icy face,

Cold and dead, lay still in her fond embrace.

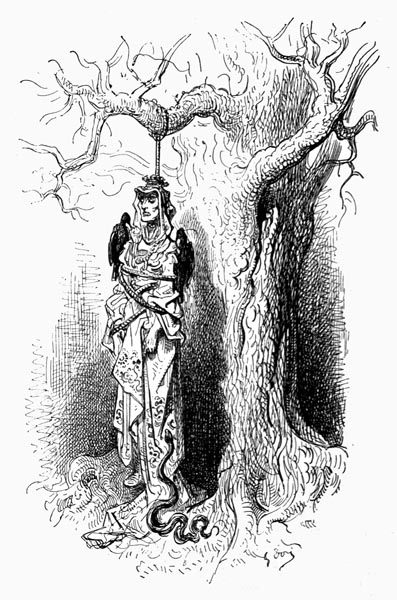

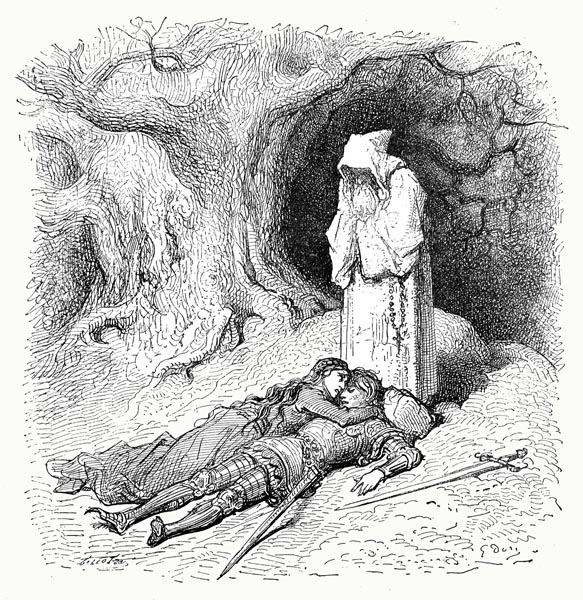

Canto XXIV: 86-93: Isabella aided by a hermit transports Zerbino’s body

Over the blood-stained corpse the maiden wept,

Bathing it in her tears, in her distress,

Her lament so great that the woodland kept

Repeating her sad cries, that ne’er grew less,

In distant echoes, nor did she except

Her breast, her cheeks, from misery’s excess,

Tearing, perversely, at her golden hair,

And calling out his name, in her despair.

She was so possessed by pain and frenzy

That she might easily have turned the sword

Against her breast, thus, failing, completely,

To obey that command of her dead lord,

If a hermit had not, unexpectedly,

Appeared. He, since the fountain did afford

A ready source of fresh water, came there,

And now opposed her wish, with a prayer.

The venerable man whose great goodness

Was combined with an inborn prudence,

And who, filled with pity and with kindness,

Many a truth expressed, with eloquence,

Persuaded the sad maid, with an excess

Of most effective reasons, to patience.

Placing, from the Testaments, old and new,

Woman, as in a glass, before her view.

Thus, he made her see that true contentment

Lay in faith in God alone; that all other

Hope was but fleeting, of little moment,

A human thing and transitory, as ever;

And so, her savage, obstinate intent

He thwarted, such that the maid did render

The time still left to her, as he did wish,

A tribute to her God, spent in His service.

Not that she sought to forget her love,

Nor allow his dear remains from her sight,

And these, whether she stayed or did remove,

The maiden kept beside her, day and night.

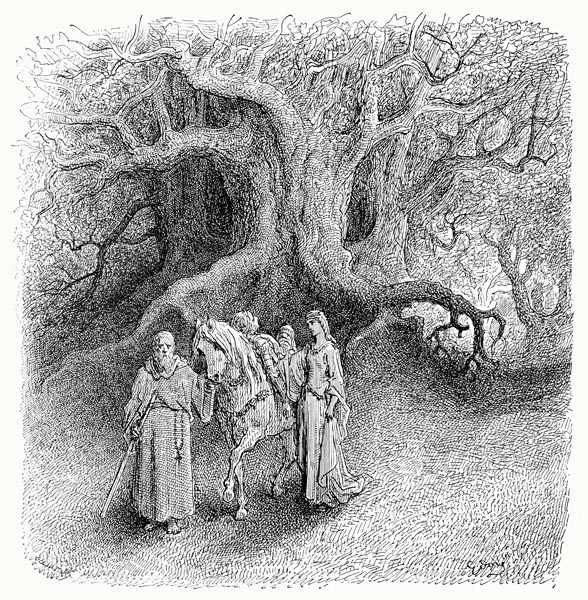

In this the hermit helped, who did prove,

For his age, one whose powers were not slight;

On his sad steed Zerbino’s corpse they placed,

And, many a day, the woodland paths they traced.

The prudent old hermit would not consent

That they be alone together; the fair maid

He concealed in a cave, with good intent,

Not far from his cell, and there she stayed.

To himself he said: ‘All is innocent,

Yet the fire midst the fuel has often strayed.’

He trusted neither age nor discretion,

Where such experiments were in question.

To conduct her to Provence was his thought,

For, not far from Marseilles, a castle stood.

There the wealthy nunnery might be sought,

Well-built and fair, in its neighbourhood.

So, to carry the knight’s corpse as they ought,

They placed it in a chest of sound oak-wood,

Wrought in a village by the road, and which

Was long and broad and deep, and sealed with pitch.

Then, o’er a vast extent of land they passed,

Amidst many a wild and savage place.

For, everywhere, the war all folk harassed,

And so, they ever sought to hide their face.

And yet a knight thwarted them, at the last,

That barred their way, much to his disgrace,

Of whom far more, in due time, you shall learn.

But, now, to the Tartar king I return.

Canto XXIV: 94-96: We return to Mandricardo, who encounters Rodomonte

After the fight, I’ve spoken of, was over,

Mandricardo betook himself to the shade,

And refreshed himself, beside the water,

Leaving his weary steed to browse the glade,

And roam amidst the grass, fresh and tender,

At will, for fine pasture the moisture made;

But was not long there, ere, far off, he saw,

A knight descending to the valley floor.

Recognising the man, once he drew near,

Doralice named him to her lover,

‘Behold, proud Rodomonte, journeys here,

Unless, perchance, my sight proves in error.

He descends the mountain, it would appear,

To challenge you; so, arouse your valour.

To have lost one he deems great injury,

That was his wife, true vengeance he would see.’

As a fine hawk, that sees its prey on high,

Wild duck or partridge, or dove, or pigeon,

Flying towards it, in the distant sky,

Will fix its sharp gaze in that direction,

Proud and alert, so Mandricardo’s eye,

Was fixed on the knight. Sure, in that action,

Of slaying Rodomonte, he bestrode

His steed, and to the duel swiftly rode.

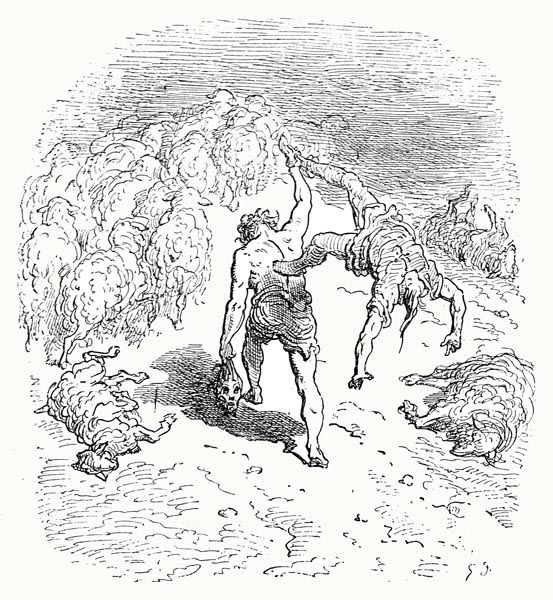

Canto XXIV: 97-107: They fight, the outcome uncertain

When the two drew nearer to each other,

That they might barter words, fittingly,

Rodomonte, with fierce look and gesture,

Commenced to state, loudly, and threateningly,

How he would serve one that for his pleasure,

Had robbed him, and injured him so rashly,

And had not scorned to insult, and incite,

One who now sought vengeance, as a knight.

Mandricardo, replied: ‘In vain his cry

That thinks his threats will engender fear;

Women or children, such things terrify,

Or other folk that hold not warfare dear,

Not I, that ever love a fight; not I,

That scorn the thought of rest, prepared as here,

To meet my foe, in the lists, or in the field,

Mounted and armed, or not, and never yield.’

They passed to insults, and shouts of anger,

To naked blades, and then the clash of steel,

As, first, a breeze, offering little danger,

The oak and ash amidst their branches feel,

Next as a wind, then a gale, grown stronger,

Making the soundest trees and houses reel,

Raises the waves, and brings the tempest on,

Till the herds, midst the glades, are slain and gone.

The valiant hearts, and the unmatched power

Of that pair, that on earth had no equal,

Gave birth to such blows, so great a dower,

Befitting warriors of their brave metal,

That the very ground trembled at that hour,

As their blades crossed; the combat mortal.

Their weapons sent bright sparks into the sky,

Thousands upon thousands did upwards fly.

Without taking breath, and never resting,

That fierce battle they waged together,

On this side and that, forever striving,

To pierce the chain-mail, or split the armour,

Neither one nor the other ever yielding,

As if bounded by a wall, men no longer

Prepared to give an inch of that ground,

And thus, within a narrow circuit found.

Amidst a thousand blows, Rodomonte

Upon the forehead, smote the Tartar king,

With a two-handed stroke; its savagery,

Turning the man about, sent him reeling;

Dazed he saw but stars in flight, all fiery.

Mandricardo, as if lost now, and weakening,

Bent low, and in full sight of his lady,

Seemed about to quit his mount completely.

Yet like an arbalest, cranked back slowly,

That strains against the tension in its steel,

The more the bow narrows, the more fiercely

The bolt flies, the greater hurt it will deal,

While the steel, returning to its shape, swiftly,

Deals more damage than any it may feel.

So Mandricardo now, with gleaming blade,

Rose and, with twice the force, the blow repaid.

Rodomonte, in the very place where he

Was hit, struck Mandricardo in reply,

But failed to wound the Tartar sorely,

Since his Trojan helm did the blow defy,

But so stunned the man that he scarcely

Knew night from day, and heaved a mighty sigh.

Meanwhile, Rodomonte ceased not, but dealt

A lesser blow at his head, that yet was felt;

For the Tartar’s mount, abhorring the sound

Of that blade whistling, falling from the sky,

In saving his master, his own death found;

For, while backing, and rearing up on high,

To escape the steel, as the blade swung round,

It struck him, not his rider, in the eye,

Cleft his head and (lacking Trojan armour

Like his lord) he sank beneath the Tartar.

He fell, but Mandricardo, his mind clear,

Slid to the ground, and whirled Durindana.

His steed stretched dead, yet still devoid of fear,

He turned about, now blazing with anger.

Rodomonte, in a new attack, drew near,

Yet the Tartar’s stance was but the firmer.

He stood like a rock that waves beat upon;

Twas the other’s steed fell, while he lived on.

Rodomonte, feeling his mount give way,

Quit the stirrups, then leapt from the saddle,

Landed, and kept his feet; thus, for the fray

Both were ready, once more poised for battle.

They recommenced, more fiercely, I may say,

In wrath, hatred, pride, about to grapple

And fight on, when a messenger appeared;

He called out, as towards the pair he steered.

Canto XXIV: 108-115: They are summoned to Paris, so make peace

He had come from the Moorish camp, apace,

Sent, with others, through the whole of France,

Summoning knights and captains, to replace

Men lost, and then beneath the flag advance;

For Charlemagne had set a siege in place,

And menaced them all, with sword and lance,

And if aid came not soon, with bold intent,

Their campaign’s collapse seemed imminent.

The messenger had recognised the pair,

And not only by surcoat and emblem,

But by the mighty blows they traded there,

Champion matched against brave champion;

Thus, to come between them he did not dare,

His status, in his humble opinion,

Not certain, in this case, to be respected,

Though by custom envoys are protected.

He feared naught from fair Doralice though,

Approached her, and said that Agramante,

With Marsilio and Stordilano,

Behind slight walls, with a weakened army,

Were now besieged, requesting her to go

To the two, explain the matter, plainly,

And seek a truce, and urge the warring pair

To cease, and to the Moorish camp repair.

Twixt the two, the courageous lady

Now set herself, saying: ‘I command you,

To end this fierce conflict; if you love me,

Sheathe your swords, ride now to the rescue

Of those menaced by this Christian army;

Our forces are besieged; what will ensue

Is utter ruin, which this news portends,

If they receive not succour from their friends.’

Then the messenger explained the danger

In which their army stood, told all the tale,

And handed Rodomonte a letter

From Agramante. Peace did now prevail,

Twixt the lords, who agreed that, together,

They would ride, and thus, of a truce avail

Themselves, till the current siege was over,

And this, they so pledged to one another;

Intending, once the army was secure,

The siege was lifted, and their duty done,

To keep each other’s company no more,

But with true ardour fight, beneath the sun,

And by their use of weapons, therefore,

Determine which of them the maid had won,

While she, twixt whose fair hands their firm oath

Was pledged, stood security for them both.

With this, Discord revealed her discontent,

Scorning truces, to peace an enemy;

While Pride too disdained their fresh intent,

And scarce could bear this new-found amity.

But Love, the greater power, being present,

Unequalled by any, in chivalry,

With his sharp arrows forced them to retreat;

Thus, Pride and Discord went down to defeat,

And the truce was concluded twixt the pair

In a form that pleased her, their commander.

The Tartar now had lacked a steed, for there,

Void of life, lay Mandricardo’s charger;

Yet Brigliadoro chanced that way to fare,

As he strayed, grazing grass, by the river;

Though I find myself at this canto’s end,

So, of your grace, I shall my tale suspend.

The End of Canto XXIV of ‘Orlando Furioso’