Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXIII: Orlando's Frenzy

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXIII: 1-5: The reward for evil deeds

- Canto XXIII: 6-8: Bradamante reproaches herself

- Canto XXIII: 9-11: She meets Astolfo with the hippogriff

- Canto XXIII: 12-16: Astolfo departs leaving his armour and lance behind

- Canto XXIII: 17-21: Bradamante seeks Vallombrosa but reaches Montalbano

- Canto XXIII: 22-27: Which she must visit, but sends a messenger to Vallombrosa

- Canto XXIII: 28-32: The messenger is her maid, Ippalca

- Canto XXIII: 33-38: Ippalca encounters Rodomonte

- Canto XXIII: 39-43: Zerbino and the crone come upon the dead Pinabel

- Canto XXIII: 44-50: Zerbino is wrongfully accused of his death

- Canto XXIII: 51-55: Orlando and Isabella arrive on the scene

- Canto XXIII: 56-61: Orlando proceeds to rescue Zerbino

- Canto XXIII: 62-66: Who thinks Isabella is in love with Orlando

- Canto XXIII: 67-69: But soon finds that all is otherwise

- Canto XXIII: 70-74: Mandricardo appears, in pursuit of Orlando

- Canto XXIII: 75-79: He has sworn an oath to win Orlando’s sword

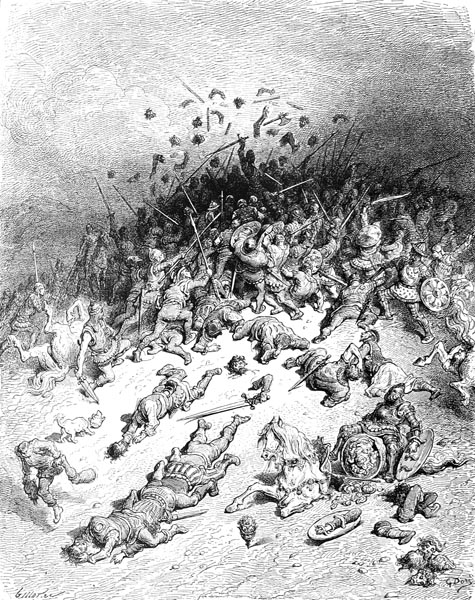

- Canto XXIII: 80-88: The two knights contend and Orlando falls from his steed

- Canto XXIII: 89-91: Mandricardo is carried off by his steed

- Canto XXIII: 92-95: He meets Gabrina and takes her bridle

- Canto XXIII: 96-99: Orlando takes leave of Zerbino and Isabella

- Canto XXIII: 100-104: He reaches the place where Angelica and Medoro had stayed

- Canto XXIII: 105-111: And then the cave where they had dallied

- Canto XXIII: 112-115: Troubled in mind, he halts at the farm

- Canto XXIII: 116-120: He learns the tale of Angelica and Medoro

- Canto XXIII: 121-124: And quits the farm

- Canto XXIII: 125-127: His lament

- Canto XXIII: 128-136: Orlando gives way to wild frenzy

Canto XXIII: 1-5: The reward for evil deeds

Let us seek to aid all others for, tis rare

That a good deed goes without its reward,

While, if there be none, at least we’ll not share

In injury, or shame, or feel the sword.

Who harms another, Fortune will not spare,

Soon or late; the debt can ne’er be ignored.

Mountains never move, but folk, they say,

Will often meet each other, on the way.

For see what happened to this Pinabel;

How, having borne himself so wickedly,

Due punishment upon the villain fell,

As was but right, for acting unjustly,

While God who, for the most part, is well

Content if none are punished wrongfully,

Saved the warrior maid, as He will save

All those whose lives are pure this side the grave.

Pinabel believed foul death he’d brought

Upon the maid; that she was buried deep.

No fear of her haunted his every thought;

Nor dreaded he her vengeance in his sleep.

And yet it served the wicked fellow naught

That his father held many a fort and keep,

Where Altaripa midst the mountains lay,

Near to his own broad realm of Poitiers.

For old Anselmo held Altaripa;

From him was sprung this fount of wickedness,

That to flee Chiaramonte’s hand forever

Needed more than mere aid, in his distress.

At the foot of a hill, she slew the traitor,

With the greatest of ease, who, nonetheless,

Cried for aid, though twas but, in misery,

To weep, and beg Bradamante’s mercy.

Once she had slain the treacherous knight,

He that had sought to murder her before,

She wished to find Ruggiero, while twas light,

Yet her harsh fate had other things in store,

Sending her, by narrow paths, to left and right,

Amidst the deepest woods, and ways unsure,

Where all was strange to her, until the sun

Had left the world to night, and day was done.

Canto XXIII: 6-8: Bradamante reproaches herself

Not knowing where she might find safe shelter,

She resolved to rest where she was, that night,

On the fresh grass, the branches above her,

Now sleeping gently, till it should be light,

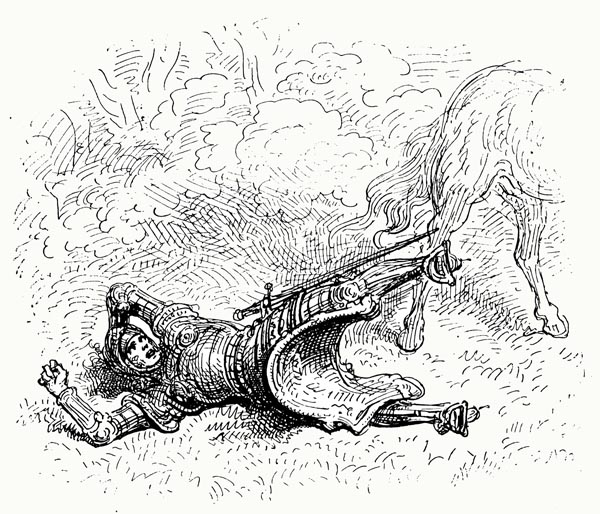

Now watching Saturn shine, now Jupiter,

Venus, or Mars, heavenly wanderers bright;

Though always, waking or in sleep, her mind

Dwelt on Ruggiero, whom she’d left behind.

From the depths of her heart, she often sighed,

(Sighs of sorrow and regret compounded)

That love had bowed to anger and to pride.

‘Anger,’ she cried ‘has my love confounded,

If only I’d looked about while I did ride

With vengeful intent, though twas well-founded,

So that I might return now, whence I came;

For sight and memory find naught the same.’

These, and other words, oft broke the silence,

And many more she mused on in her mind;

Meanwhile her gusts of sighs and penitence,

Her rain of tears, rendered her deaf and blind.

At last, the new dawn announced its presence,

Bright sunlight, in the east, the world defined;

She found her steed, now grazing by the way,

Mounted, and so rode forth, to greet the day.

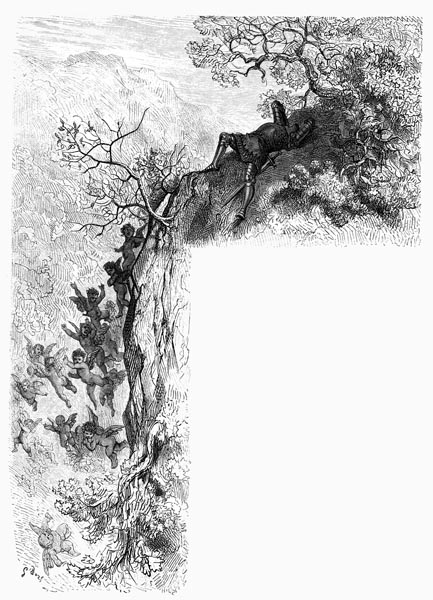

Canto XXIII: 9-11: She meets Astolfo with the hippogriff

She had not ridden far, when, midst the wood,

She came to where they’d met with such delay,

For there the enchanted mansion had stood,

And there the wizard held them many a day.

She found Astolfo who, as best he could,

Had equipped the hippogriff for his foray,

Yet was lost in thoughts of Rabicano,

And on whom he might that fine steed bestow.

By chance, she found him as the warrior

Removed his helm, his face was thus in view,

So that, clear of the forest, riding nearer,

She saw that it was her cousin, and flew,

Hailing him, from afar, as a brother,

And once there, clasped him to her anew,

Said her name, and raised her visor, swiftly,

So, he could clearly see that it was she.

Astolfo could not have found a better

Person with whom to leave Rabicano,

Than the Duke of Dordona’s brave daughter,

Knowing she would care for him, and also

She’d yield the steed when he returned later,

And felt that God, in truth, had sent her, so

To do, ever pleased to see her, indeed,

Yet even more so in his hour of need.

Canto XXIII: 12-16: Astolfo departs leaving his armour and lance behind

Three times at least, the cousins now embraced,

With familial affection, and sought,

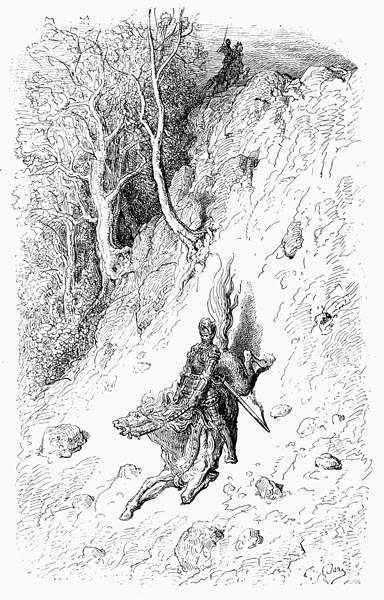

Each, to know how the other one was placed,

And then Astolfo of his wishes gave report:

‘I would see the land where chargers are graced

With wings, yet I linger here.’ His thought

He exposed to the warrior maid, and showed

Her the flying horse, which Ruggiero rode;

Though it was scarcely a marvel to her,

To see the wondrous beast its wings unfold;

For, long ago, the wizard had assailed her,

When he had flown about his mountain hold,

While she had strained her eyes; far above her,

She had gazed his soaring flight to behold,

That day when, on a journey long and strange,

Ruggiero had been borne beyond her range.

Astolfo wished upon her to bestow,

His Rabicano, so swift of its kind,

That, departing with the dart from a bow,

Twould ever leave that arrow far behind;

And his armour he also would forego,

Which to Montalban should be consigned,

And kept there, till he returned once more,

Since he would need it not, he felt most sure.

For, wishing to ascend the air in flight,

He desired to lighten the load further,

Yet he kept his sword and horn, did the knight,

Though the horn, alone, repelled all danger.

His lance he abandoned, once of right

Borne by Galafrone’s son, Argalia,

That whoever it touched, in its swift course,

Would topple, in an instant, from their horse.

Astolfo leapt upon the steed, and promptly

Set it moving, though slowly, through the air,

Then spurred it on, such that Bradamante

No longer in their movements could share.

So, the pilot guides a ship, cautiously,

Through the reefs, fearing danger everywhere,

And then, once the shore is left in its wake

Its captain, with full sails, his course will take.

Canto XXIII: 17-21: Bradamante seeks Vallombrosa but reaches Montalbano

The warrior-maid, now the duke had flown,

Was most troubled in her mind, as to how

She might lead Rabicano, on her own,

To Montalbano, with all he did endow.

For the ardent desire of flesh and bone

Was to seek Ruggiero, you’ll allow,

Whom she hoped to find at Vallombrosa,

If she met him not ere she rode closer.

But, while standing there musing, she espied

A peasant lad, who o’er the plain did go,

Who, at her request, the duke’s armour tied,

As best he could, on brave Rabicano;

And gave him charge of the other beside.

Two he led, one burdened, and did follow,

For Bradamante owned the horse as well,

That she had now retrieved from Pinabel.

She thought to proceed to Vallombrosa,

Hoping that Ruggiero might be there.

But knew not which was shorter or better,

Of the many roads o’er which she might fare,

While the lad’s knowledge ran little deeper,

And thus, they might well wander everywhere.

So, she decided, at a venture, to stray

Down a path that, perchance, led where it lay.

She looked to left and right, as on they went,

Yet found none there of whom to ask the way,

But on leaving a wood, a keep did present

Itself to weary eyes, about mid-day,

Upon a mount, above the road they went,

It seemed like Montalbano, and held sway

O’er all the land around; twas no other;

And there dwelt her mother, and a brother.

When the warrior-maid saw the place,

She was sadder at heart than I can say;

She would be known, if any saw her face,

Which would, rightly, cause a long delay,

And yet, were she not to depart, apace,

To the ardent fire, within her, she’d fall prey.

Nor would her Ruggiero be closer,

Nor aught she’d reserved for Vallombrosa.

Canto XXIII: 22-27: Which she must visit, but sends a messenger to Vallombrosa

She pondered a while, and then decided

She would turn her back on Montalbano,

And head towards the abbey, for she prided

Herself on knowing, now, the way to go;

But Fortune, for good or ill, now guided

One of her brothers there, named Alardo,

Ere she could issue forth from out the dale,

Nor had she time to hide; fate would prevail.

He came from billeting the men that lay

About that place, foot and horsemen too;

King Charlemagne’s decree he must obey,

To whom a further levy, now, was due.

He embraced her in a most kindly way,

And so, they went forward, two by two,

And thus, talking together, side by side,

Up to Montalbano, that pair did ride.

The warrior-maid entered Montalbano,

She, whom her mother Beatrice with tears

Had longed for, seeking news of her also

Through every part of France, it appears.

Now all was kisses, hand in hand, although

She could not but compare (though fondness cheers)

Their welcome with her lover’s sweet embrace,

That time could never from her mind efface.

She thought to send, because she could not go,

A messenger, instead, to Vallombrosa,

Instructed to let Ruggiero know

Why she herself could not be there sooner,

Praying him (if prayer were needed, also)

To be baptised, at once, if he loved her,

And then come, and effect what was required

To bring about the marriage both desired.

By the same messenger, she intended

To return his good steed to Ruggiero,

Which he held ever dear, and extended

His fond care to one so worthy, for no

Courser could be found quite so splendid.

Nor the Saracens, nor France could show

A finer, braver steed (as all did know)

Other than Bayard, and Brigliadoro.

When, with great audacity, Ruggiero

Had soared aboard the hippogriff, on high,

He’d left the steed, that was named Frontino,

To Bradamante’s care, who, by and by,

Sent him, to be kept, at Montalbano,

At great cost; he was well-treated thereby,

Richly fed, yet rendered sleek, by the grace

Of brief excursions, at a modest pace.

Canto XXIII: 28-32: The messenger is her maid, Ippalca

She soon set her ladies, and every maid,

To labour with her on embroidering

A piece of silk in white and black, o’erlaid

With finest gold, and, with this, covering

The bridle and the saddle, she then bade

One of the women come to her, choosing

The kind daughter of Callitrefia,

(Her nurse) who shared her secrets ever.

A thousand times she had told the maid

How Ruggiero had conquered her heart;

To his virtue, beauty, manners, had paid

Great tribute, holding him a man apart.

‘None better than yourself,’ she said, ‘to aid

My true love and myself, with all your art,

None, my Ippalca, so faithful, so wise,

As an ambassadress, beneath the skies.’

Ippalca then was this fair maiden’s name.

‘Go!’ said Bradamante, pointing the way,

Having told her all about that same,

And what, to Ruggiero, she should say,

Of her tardiness, and what was to blame:

That bad faith was not a cause of delay,

But to Fortune he should impute that ill,

That, more than ourselves, rules us still.

She had helped her mount a palfrey, then set

Frontino’s reins in her hand, and told her

That if any man so rude or mad, she met,

As to seek of that steed to deprive her,

She was to tell him, and must not forget,

Who it was that owned the mighty charger,

For she thought there was none, here below,

That feared not that name of ‘Ruggiero’.

Of many and many a thing she’d told her,

To be relayed to Ruggiero in her stead.

Ippalca having gathered all this to her,

Now set upon her way, and onwards sped,

By road, and field, and forest, however

Gloomy, more than ten miles his steed she led,

Yet none crossed her path that sought her harm,

Nor asked here where she went, nor gave alarm.

Canto XXIII: 33-38: Ippalca encounters Rodomonte

About mid-day, on descending a hill,

In a narrow and unpleasant defile,

She encountered Rodomonte, armed to kill,

And guided by a little dwarf the while.

The bold Moor, expressing his proud will,

Gazed at her and blasphemed, in evil style,

Cursed the heavens above, that this fine steed

She led yet lacked a knight, to meet his need.

For he had sworn to seize the first good horse

That he chanced to encounter on the way,

And this was the first, and none perforce

Seemed finer, or more suited to affray.

Yet to take it from a maid, seemed a course

To be frowned upon, and so he chose delay,

Gazed covetously at him, and then said:

‘Where is his master now; alive or dead?’

‘Ah, would that he was here,’ the maid replied,

‘For he, perchance, would force to you think twice.

That steed a better knight than you doth ride,

Unequalled in this world, to be precise.’

‘Who claims that honour, then?’ the pagan cried,

‘Ruggiero!’ she answered, in a trice.

‘Then I will have him for my own,’ he said,

‘Since for so great a champion he was bred.

And if this knight is as great as you say,

So fine, and worth more than any other,

Then not for the horse but its hire I’ll pay,

And render it at his master’s pleasure.

Relate the tale, say I am Rodomonte,

And if he’d like to joust with me a measure,

He shall find me, where’er I go or stay,

A man who e’er shines forth, in his own way;

For, where’er I go, I leave behind me,

Like lightning, the traces of my passage.’

With this, he threw the gilded reins swiftly

O’er Frontino’s head, and then, stage by stage,

Backed up the steed, and so left her sadly

Bemoaning its loss, and this cruel outrage.

Ippalca cried shame, threatening the Moor,

But he hearkened not, and rode on as before,

The dwarf ever guiding him in his pursuit

Of Doralice and bold Mandricardo,

While Ippalca, at a distance, followed suit,

Cursing and taunting him, as they did go.

What came of this, my later verse shall bruit.

Bishop Turpin wrought this tale long ago;

Here he digresses too, and turns again,

To that same place where Pinabel was slain.

Canto XXIII: 39-43: Zerbino and the crone come upon the dead Pinabel

Bradamante had scarcely turned her back

On his corpse, and departed on her way,

Ere Zerbino came there, by another track,

With that deceitful crone he must obey,

And saw the body there, that life did lack,

Though who the knight might be, he could not say.

Yet as the prince was kind and courteous,

He felt saddened by a sight so piteous.

Now, Pinabel lay dead upon the ground,

From whom so many streams of blood did flow

It seemed as though a hundred swords had found

His poor flesh, and combined to lay him low.

From all the hoofprints that did there abound,

He sought to understand, the good Zerbino,

If, perchance, those traces he might read,

And find who had wrought the murderous deed.

And so, he told Gabrina to wait there,

And he’d return to her without delay,

But she towards the corpse did swiftly fare,

And gazed all about her, every way,

Since whatever caused her eyes delight,

She wished to prosper from, by night or day,

As one who was more filled with avarice,

Than any other woman ever was, or is.

If she’d thought she could carry off the theft,

She countenanced, in any secret manner,

The victim’s costly surcoat, that was left

Upon him, she would have seized, together

With his armour, yet only that she reft

From him, that she could conceal thereafter,

Dropping the rest, full sadly, but a belt

She took, and hid about her, as she knelt.

In a little while, Zerbino returned,

Who’d followed Bradamante’s tracks in vain,

For he found her trail twisted so and turned

It led deep within the trees, to his pain,

And by the fast-fading light now concerned,

And desiring to retreat towards the plain,

To find lodging, with the evil crone in tow,

From that fatal valley, forth he did go.

Canto XXIII: 44-50: Zerbino is wrongfully accused of his death

Two miles away, a castle they did spy,

Twas the great fortress of Altaripa.

They halted for the night; since, o’er the sky,

The darkness gathered, swifter and swifter;

Yet were not long in the city, ere a cry,

A lament, arose, mournful and bitter,

While from every eye the tears did fall,

As if some tragedy had touched them all.

Zerbino asked to know what had occurred,

And was told news had come to Anselmo,

That in a narrow pass, so they had heard,

Pinabel his son lay dead, hence their woe.

Zerbino lowered his gaze, said not a word,

And feigned an unknowing face to show,

Though doubtless aware that this must be

The corpse he’d come across on his journey.

After some time, the funeral bier was seen,

Amidst bright fiery torches, and the cries

Were louder, while, about that mournful scene,

The crowd’s lament rose to the starry skies.

And faster flowed the tears, as they did keen,

The bitter streams descending from their eyes,

But far cloudier and darker was the face

Of his most wretched father, in that place.

While most solemn preparations were made,

For the funeral pomp, and the obsequies,

According to such honours as were paid

In days of old (corrupted now, in these),

Their master’s proclamation was relayed,

That all but made the louder mourning cease,

And pledged a rich reward to anyone

That could discover who had slain his son.

From voice after voice, to ear after ear,

News of the proclamation spread further,

Until that wicked woman chanced to hear,

She more savage than a bear or tiger;

Twas news that would cost Zerbino dear.

Either from hatred, or that she was ever

Human in form yet lacked humanity,

To ruin the prince, she schemed, secretly;

Or perchance she but wished for the reward.

Granting an air of truth to her false tale,

She told a falsehood to the grieving lord:

That the prince had slain his son, in the dale,

While the belt as evidence she did afford,

Which the father recognised without fail.

And from this, with the crone’s testimony,

Assumed the prince was the guilty party.

Lamenting, he raised his hands to the sky,

Demanding vengeance on the murderer,

While men surrounded the lodgings, nearby,

Where the prince lay, in their sudden fervour.

Zerbino, thinking that no foe was by,

And expecting no harm whatsoever,

Was soon seized by Anselmo’s soldiery,

Accused of having wrought the injury.

Canto XXIII: 51-55: Orlando and Isabella arrive on the scene

That night, Zerbino lay in a dark cell,

Chained in heavy fetters, till the morn.

His execution, but delayed a spell,

Had been ordained for the first light of dawn:

That he be quartered in that very dell

Where the wicked crime itself had been born.

No other evidence did any show,

Twas enough that the Count believed it so.

When, with the dawn light, came fair Aurora,

Turning the heavens yellow, white, and red,

A crowd, seeking vengeance for the murder,

Crying: ‘Death! Death!’ o’er the innocent’s head,

Came to lead him, in angry throng, together,

Some mounted, some on foot running ahead,

To the place, as the prince, with eyes downcast,

On a sorry nag, to his death now passed.

But God, who often aids the innocent,

Nor deserts those who trust in his goodness,

Granted him help in thwarting their intent;

He would not die that day, whom God did bless;

For there Orlando came, as on they went,

That Zerbino might be saved nonetheless.

For Orlando saw the crowd upon the plain,

The young prince, riding deathwards, in their train.

With Orlando, rode that royal daughter

Whom he had found in the savage cave,

Galicia’s fair child, Isabella,

Whom from the band of thieves he’d chanced to save.

Into their hands she’d fallen, earlier,

When her vessel had sunk beneath the wave.

She, held Zerbino dearer to her heart

Than her own soul, though they were long apart.

She’d travelled in Orlando’s company

Since being rescued from that stony cell;

Now she sought to know who this crowd might be

Proceeding noisily towards the dell.

Orlando left the maid, and rode there swiftly,

For who and what they were he could not tell,

But gazing on Zerbino, at first sight,

Knew him to be a true and noble knight.

Canto XXIII: 56-61: Orlando proceeds to rescue Zerbino

Drawing closer, he demanded to know

Where they were taking the captive, and why.

At this, raising high his head, Zerbino,

Comprehending the question, gave reply,

Spoke the truth, and thereby showed Orlando

That, in no way, did he deserve to die.

Orlando, finding he was innocent,

Now aimed to foil this crowd of their intent.

And when he understood that all was done

On the orders of the Count of Altaripa,

He was sure the prince had not slain the son,

Since naught but ill was born of them ever.

Moreover, his line were foes to one

In whose veins ran the blood of Maganza,

By reason of the ancient enmity

Twixt his house and that of Chiaramonte.

‘Untie the knight, if you would not be slain!’

Cried Orlando to Altaripa’s crew,

‘And who is this, that would that same ordain?’

Answered one, who seemed bravest and most true.

‘Were he of fire, that tone might appertain,

And we of wax and straw, of pallid hue!’

And, with that, charged the champion of France,

Who’d responded, by lowering his lance.

The bold Maganzese’s shining armour,

Which he’d taken, at night, from Zerbino,

Now proved no defence whatsoever,

In his fierce encounter with Orlando,

Whose blow struck his cheek and, though no deeper

Did it penetrate the helm, even so,

His neck was broken and, without a sound,

Robbed of life, he fell sideways to the ground.

Without pausing, without raising his lance,

Orlando pierced another horseman through,

Then, Durindana in his hand, did advance

And attacked the rest of the motley crew.

One’s head he lopped, in his deadly dance,

Another’s skull he neatly cleft in two,

Pierced full many a throat and, in a breath,

A hundred he’d shattered, or put to death.

Two thirds or more he slew, dispersed the rest,

And struck, and pierced, and cleft as he rode on,

Here a helm, there a shield he dispossessed

Its owner of, pikes and billhooks too were gone.

One along, one o’er the road, lay at rest,

While some hid in woods or caves, here and yon,

Orlando, on that day, showed no pity,

Twas in his power to deny them mercy.

Canto XXIII: 62-66: Who thinks Isabella is in love with Orlando

Of a hundred and twenty (so maintained

Bishop Turpin) at least eighty men died.

Orlando, from the field, at last, regained

The spot where the fearful prince did abide.

I could scarce express the joy he attained,

When Orlando rode swiftly to his side.

He would have knelt, in thanks, on the ground,

If, there, upon the nag, he’d not been bound.

While Orlando, once he had freed the knight,

Had him don his shining armour, as before,

Stripped from the captain who in the fight

Had worn it, to his own harm, now no more.

The prince on Isabella turned his sight,

Who once she saw that the battle was o’er,

Having halted on the hill, roused her steed,

And, to the field below, brought beauty indeed.

When the lady, so dear to Zerbino,

Appeared close by, on that very ground,

She for whom he had felt such sorrow,

She, that a lying tongue had claimed was drowned,

He felt his heart had turned to ice, although,

After feeling chilled within, he soon found

The coldness ebbed, and all his flesh entire

Seemed engulfed in flames of amorous fire.

Respect for Orlando made him refrain

From embracing her as he might have done,

Reflecting, though indeed it gave him pain,

That the Count, most surely, her love had won,

So, from pain to pain he passed, and little gain

Had he from all his previous joy, or none;

To view her as another’s, seemed instead

Far worse to him than hearing she was dead.

He grieved the more in that she rode beside

A knight from whom his life he’d received.

To reclaim her, it could not be denied,

Was neither honest, nor easily achieved.

He’d have much preferred to have fought and died,

Than relinquish the maiden, he believed,

But so profound, in this case, was his debt,

He must bow to the Count, and lose her yet.

Canto XXIII: 67-69: But soon finds that all is otherwise

Riding, silently, they soon came to a spring,

Where they dismounted, and rested awhile.

Here the Count undid his helmet, assisting

The prince to so yield, after his sore trial.

When the lady saw his face, free of the thing,

She grew pale with sudden joy, in such style

As does a flower, that drenched with rain, grows bright,

When the sun re-appears, and sheds fresh light.

Without a thought, in a moment, she ran

To her love, and clasped him in her embrace,

And not one word could she speak to the man,

But with happy tears bathed his neck and face.

Count Orlando whose eyes the pair did scan,

Required naught else the path of love to trace,

And words, indeed, were needless to show

That this youth must be her own Zerbino.

When Isabella her speech could recover,

Although her tear-drenched cheeks were not yet dry,

She spoke only of the courtesy that ever

Had been shown her by the Count; by and by,

Zerbino, who held the maiden dearer

To him than was his life, much moved thereby,

Fell at Orlando’s feet, and praised this lord

That, in an hour, had two young lives restored.

Canto XXIII: 70-74: Mandricardo appears, in pursuit of Orlando

Many a word of thanks, and many an offer,

Would have followed between the knightly pair,

Had they not heard, beneath the leafy cover,

The darkened ground echo swift passage there.

Their helms they ran, quickly, to recover,

Late removed, and to their steeds did repair,

When they saw a knight and maiden appear,

Almost ere they’d mounted, and draw near.

It was the Tartar king, Mandricardo,

Who had followed behind the Count, in haste,

To avenge Alzirdo, and Manilardo,

Whom Orlando had previously faced.

Though his pace after that was somewhat slow,

Since Doralice now his presence graced,

Whom he’d seized from a hundred men in armour,

With but an oak staff, she now his lover;

Though the warrior knew not he did pursue

The Lord of Anglante, Count Orlando,

Yet by certain indications he knew

It was a powerful knight he followed so.

He examined, from head to foot, the two,

Though the Count more closely than Zerbino,

And, finding the signs he’d noted, and more,

Cried: ‘Here is one whom I was searching for!

For ten days now I have followed you,’

He added, ‘and have never left the trail,

To such a degree did those tales of you

Rouse me, that in our camp did then prevail,

When, of a thousand men, barely a few,

Returned to tell us how you did assail

The ranks of Tremisenne and Norizia,

And put their warriors to the slaughter.

Once I had heard of you, I was not slow

To follow, that I might behold your face,

And prowess, while by your surcoat I know

You are the knight whom I desired to trace,

Yet if some other garb you were to show,

And midst a hundred did yourself efface,

That proud gaze of yours would yet have told me,

You are the one I sought most urgently.’

Canto XXIII: 75-79: He has sworn an oath to win Orlando’s sword

‘No man dare say,’ replied Count Orlando,

‘That you are not a knight of high honour.

For such a bold desire, it must follow,

Could not arise in a heart sans valour.

Since you, it seems, have come to view me so,

Then behold the inner, not just the outer,

I shall remove the helmet from my brow,

Thus, the object of your quest you may avow.

Yet once your eyes have dwelt upon my face

Attend then to that other wish of yours,

The desire I shall address, in this place,

Which also set you on this warlike course:

To prove if, now, that valour I embrace

That in my noble semblance you endorse.’

‘Then,’ cried the pagan king, ‘let us fight,

For, so, my second wish you shall requite!’

While he spoke thus, the Count’s enquiring eye

Was searching the bold knight, from head to toe,

Examined too his steed, yet failed to spy

Any sign of sword or mace; he sought to know

How the warrior would his valour try

If his good lance was broken at a blow,

‘Be not concerned,’ replied the pagan knight,

‘Many a man yet feared me in the fight;

I have sworn to wear no blade at my side,

Till Orlando’s Durindana is my own,

And after him I everywhere did ride,

And upon more than one steed have I shown.

I swore it (and by that oath I abide)

When I donned this helm, that Hector alone

Bore on his brow, a thousand years ago,

And my other armour he then wore also.

All that I lack now is Orlando’s sword.

When the thing was stolen, I cannot say,

But now, it seems, tis borne by that great lord,

And hence he has such courage in affray.

Yet if I can but meet him, I’m assured

Of his rendering what he stole that day;

And I seek true vengeance, moreover,

For the death of Agricane, my father.

Canto XXIII: 80-88: The two knights contend and Orlando falls from his steed

Count Orlando slew him by treachery,

For he could not have done so otherwise.’

The Count could not but speak: ‘Tis false!’ cried he

‘And whoever said so is but full of lies.

For him, you have sought for you now see.

I am Orlando, that all falsehood defies;

I slew him fairly, and here is the sword

Which you shall have, if such you can afford.

Although the sword is mine, and mine by right,

We’ll contend for it, in knightly manner,

Nor shall either man own it, while we fight;

I shall hang it in this tree; if you conquer

You shall have it, freely, obtained by might;

That is, if I am slain, or I surrender.’

And, with this, Durindana he revealed.

And hung it on a sapling in the field.

Half a bow-shot’s distance from each other,

The two warriors placed themselves apart;

And then the two met swiftly together,

With a fine display of the horseman’s art,

Striking fiercely against one another,

That matched blows to their visors did impart.

Like shafts of ice the lances broke in two,

As a thousand splinters to the heavens flew.

Though both the knight’s lances were shattered,

Neither to that stroke of fortune would bend,

Both men charged again, if somewhat battered,

And with the stumps of their lances did contend.

These warriors who their steel weapons flattered,

Like two farmers sought to uphold their end,

That o’er a boundary or stream, proudly, fight,

Armed with clubs, each man arguing his right.

No more than four blows could their weapons bear,

Then broke apart with the fury of that battle,

With growing rage, they staggered here and there,

With only their fists to display their mettle.

They grasped the armour, at chain-mail did tear,

Twisting steel in their hands, as they did grapple.

None could desire, smiting in that manner,

Better tongs, or a weightier hammer.

How might the Tartar king devise a way

To conclude the fight his honour had sought?

Twere madness to continue that fierce fray,

Where each but harm to himself now wrought.

They drew each other close, as they did sway;

Full tight the pagan, thus, Orlando caught,

Against his chest, as Heracles once clasped

Antaeus to him, while his arms he grasped.

Mandricardo exerted all his power,

Pushed him away, then seized him more tightly,

But Orlando sat firm, like some strong tower,

Neither to right nor left moved easily,

The Count waited his moment, face full dour,

And then stretched forward his hand slily,

Sensing victory, caught the other’s bridle,

Above, then dragged it down, and let it fall.

The Tartar king meanwhile had vainly sought

To drag him from his mount, but Orlando

Grasped his steed, with his knees, as they fought;

Naught for his efforts could the pagan show.

Yet the force he exerted broke the taut

Girth that held the saddle firm below;

The Count tumbled sideways, not knowing why,

His feet in the stirrups, pointing at the sky.

With the sound made by a sack of armour,

As it falls to earth, so Orlando fell,

While the king’s steed (its bridle lost) in terror,

Sped away, by dark grove, and woodland dell,

On a ruinous course, hither and thither,

As if maddened by some demon’s spell,

Blind with fear, stumbling as it did go,

Still bearing on its back Mandricardo.

Canto XXIII: 89-91: Mandricardo is carried off by his steed

Doralice who saw her companion

Borne from the field and her vicinity,

Unwilling to remain now he was gone,

After his swift charger sent her palfrey.

The proud king cursed his steed, that yet flew on,

And struck at him with hands and feet, vainly,

Threatening the horse as if twere human,

Yet the more he did, the faster it ran.

The creature, of a somewhat fearful kind,

Not looking to its course, careered about.

Three miles it had gone, still running blind,

When a ditch arrested that sudden rout,

Into which, upside-down, both were consigned,

And naught to break their fall; with a shout,

Mandricardo to the hard earth was thrown,

Yet was neither slain, nor broke a bone.

Thus, their travels came swiftly to an end;

While, on its feet now, the horse lacked a rein,

Which the king, in a rage, sought to amend,

By grasping the poor creature by the mane.

Doralice now called out to her friend:

‘Take the bridle from my palfrey, if you deign,

For the horse is gentle, without a doubt,

Whether ridden with a bridle or without.’

Canto XXIII: 92-95: He meets Gabrina and takes her bridle

The Tartar thought it a discourtesy

To accept Doralice’s kind offer,

But won another bridle, most strangely,

Fortune operating in his favour;

Since the wicked Gabrina he did see,

Who’d betrayed Zerbino; for the traitor

Like a she-wolf had fled, o’er hill and dale,

That hears the hounds and hunters on her trail.

The old crone was still wearing that same dress,

And the same youthful adornments, as well,

That Zerbino had seized, as fair redress,

From that ill-mannered maid with Pinabel,

And on the maiden’s horse she did progress,

One of the choicest, and sound as a bell.

Upon the Tartar, and his friend, she came,

Ere she was, indeed, aware of those same.

Fair Doralice and Mandricardo

Were moved to laughter by her youthful dress;

She resembled a baboon, in that show

Of finery; a human ape, no less.

The Tartar king, in a moment, did go

To strip the bridle from her steed, with success,

And then, with a loud and threatening cry,

Scared the creature, till, away it did fly.

The horse sped through the wood, together

With the old crone, now almost dead with fear,

O’er hill and dale, by straight ways and other,

O’er bank and ditch, much like a startled deer;

Yet my verse must no more dwell on either,

To Orlando’s path I again must steer,

Who, with none left to engage in battle,

Repaired, at length, the girth on his saddle.

Canto XXIII: 96-99: Orlando takes leave of Zerbino and Isabella

He remounted, and then waited, for a space,

To see if Mandricardo would return,

But seeing he did not, prepared to trace

His passage, the Tartar’s course to learn;

Yet as was his custom, born of grace,

Ere he departed, to his friends did turn;

A sweet and courteous speech he did air,

Then took his leave of the loving pair.

Zerbino was much grieved at their parting,

And Isabella wept from tenderness.

They wished to ride with him but, on starting,

He declined their company nonetheless,

Though he thought it fair and good, declaring

That a knight who would an enemy address,

Must not take with him his dearest friend,

And upon his arms and succour thus depend.

He begged them, if they met Mandricardo,

Before he should come upon him, to say

That, for three days, his opponent Orlando

Would, willingly indeed, prolong his stay,

But then, to Charlemagne’s aid he must go,

Where the gold fleur-de-lys was on display.

Thus, the Tartar, if his foe he still sought,

Would know where to find him; with the court.

The lovers promised that they both would do,

This, and whatever else he might command.

They parted, their different roads to pursue,

They by the plain, Orlando the woodland.

The Count ere he went, his sword withdrew

From the sapling, and then as he had planned,

Steered his steed in the Tartar’s direction,

Where he best might meet with further action.

Canto XXIII: 100-104: He reaches the place where Angelica and Medoro had stayed

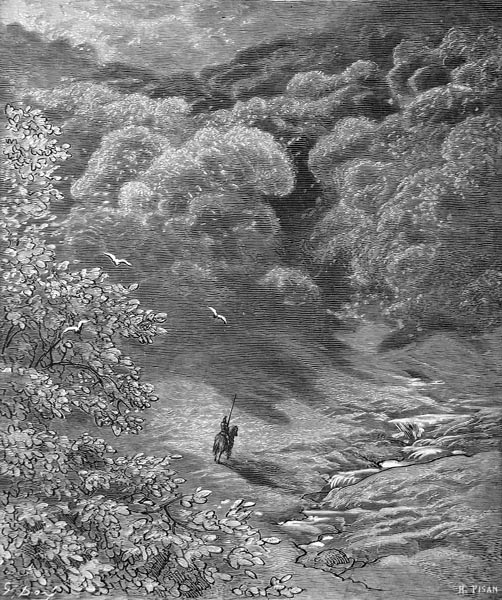

The errant course the pagan’s steed had taken,

Amidst the forest, and on pathless ways,

Led our knight through many a forsaken

Wooded vale, and wasted nigh on two days.

Thence he came where crystal waters, shaken

By a breeze, through a meadow went their ways,

A flowery place, decked with various hues,

And many a fine tree, amidst sweet views.

The shade was welcome in the mid-day heat,

To the herd, and their naked herdsman too;

While Orlando, who the sun’s rays did meet

In plate armour, felt them through and through.

He entered, for respite, that cool retreat,

Yet found it but a cause for pain anew,

A place more bitter than the tongue could say,

On that unhappy, and ill-omened day.

Gazing, about him, at many a tree

On that shaded bank, Orlando saw,

(As soon as he had scanned it more closely)

That the bark his beloved’s writing bore;

This was the place I spoke of previously,

Whence, from the herdsman’s hut, some time before,

Medoro and Angelica would stray,

She the lovely queen of far Cathay.

With a hundred knots all interlaced,

On a hundred trees, there, ‘Angelica’

And ‘Medoro’ the rugged surface graced,

Those letters, barbs, sinking ever deeper.

Despite himself, believing, she had traced

Their outlines, though, ere this, he’d have never

Believed the like, he sought to see another

Hand, here, than that of his erstwhile lover.

‘And yet I know those characters,’ he cried,

‘That I have seen so many times before;

Perchance a name for me she has supplied,

And myself as one Medoro does adore.’

Such fantasies, far from the truth, did glide

About his brain, as that sudden pain he bore.

Orlando grasped at hope, though ill-content

With those illusions self-deception sent.

Canto XXIII: 105-111: And then the cave where they had dallied

Yet the more he sought to quench suspicion,

The more it was rekindled and renewed,

Like the unwary bird whose inattention

Leaves the creature netted, or limed and glued,

While the more it struggles in contention,

The more tis caught, tangled and subdued.

Orlando reached a place where the mount,

Like an arch, overhung a crystal fount.

Clinging ivy, and the straggling vine,

The lofty entrance to that cave did grace,

Where, in the heat of day, would oft recline

That pair of lovers, locked in fond embrace,

Who’d writ their passion there, in bold design,

With chalk and charcoal, all about the place;

And, likewise, were those same two names displayed

Engraved in the stone, with a knife’s sharp blade.

From his steed, descended Count Orlando,

And read the words carved about the opening,

Seemingly inscribed by this Medoro,

And but recently, judged by their cutting.

These lines, in verse, his delight did show,

Regarding all the pleasure appertaining

To the cavern, writ in his native tongue,

And here’s the sense, in ours, of what he sung:

‘Sweet foliage, green herbs, and clear water,

Dark cavern, with your cool and welcome shade,

Where Angelica, Galafrone’s daughter,

Beloved in vain of many, here, displayed

Her naked charms to me, for the shelter

You kindly granted us, when here we strayed,

I, Medoro, poorly recompense you,

With these lines, that will forever praise you;

And I ask of every lord passing by,

And every amorous knight and lady,

Every native, each traveller, neath the sky,

Led here by Fortune, or proclivity,

To the herbs, shade, stone, grass, and water, say:

“Be blessed by the moon and sun, endlessly,

And may the lovely choir of Nymphs decree

That of his flocks the shepherd keeps you free.”’

This was writ in Arabic, which Orlando

Read as well as Latin and, of all those

Tongues he knew greatest skill in this could show,

And, therefore, could wander where he chose;

It had saved him from harm, and shame also,

Amidst the Moors, when occasion arose.

Yet twas a vain boast such things to recall,

For the pain that it brought now paid for all.

Five and six times, or more, he read the verse,

The unhappy wretch, and still searched, in vain,

For some other meaning he might rehearse,

Yet ever found the thing most clear and plain.

All, the while, a hand, icy and perverse

Gripped within him, and did his heart constrain.

He stood, in sum, eyes and mind upon the stone,

As if made such, and no longer flesh and bone.

Canto XXIII: 112-115: Troubled in mind, he halts at the farm

He fell prey to an overwhelming woe,

And well-nigh lost all sense and perception.

Tis believed by such folk as anguish know,

That this pain e’er proves the worst affliction.

His brow, of pride bereft, bowed full low.

His chin upon his chest, devoid of action,

He found he could not weep (so deep his grief)

Nor in dire lamentation find relief.

Within him that impetuous woe was pent,

That sought to issue with too swift a flow;

Like water in some bottle, his lament,

The vessel ample, the neck too narrow,

That when up-ended, with the fond intent

Of emptying it, doth but a trickle show,

The liquid meeting with so great a stop,

It emerges but slowly, drop by drop.

Returning to himself, it crossed his mind

That perchance the whole thing might prove untrue,

That someone bent on shaming her he’d find,

Who’d plotted, yearned, and sought so to do;

And, with such jealousy, hoped to blind

Him, her lover, that would slay him too;

And that the man who had this whole thing planned,

Had forged the writing in his lady’s hand.

With such slight and feeble hopes, he sought

To rouse his spirits, and pursue his way,

And so, to Brigliadoro made resort,

As moonlight now replaced the glow of day.

He had not gone far, ere the sight he caught

Of smoke, above a farm, that near him lay,

Heard cattle lowing, and the dogs barking,

And drawing closer to it, sought lodging.

Canto XXIII: 116-120: He learns the tale of Angelica and Medoro

Dismounting, he left Brigliadoro

To the care of a lad, while another

Removed his gilded spurs and, to follow,

Another relieved him of his armour.

This was the farmstead where Medoro

Lay wounded, and met with high adventure,

Orlando, without seeking to be fed,

Yet sated with sorrow, now sought his bed.

But the more the Count searched for peace and ease,

The more he found but pain and sore travail;

For that vile writing seemed his mind to tease,

On every door, wall, and window left its trail;

He rose to ask, but in mid-flight did cease,

Fearing to learn the plain truth of the tale,

Wishing rather that all might be concealed,

That might the more offend him if revealed.

Yet the Count’s silence proved of small avail,

For it was spoken of without his asking.

The herdsman, who thought his face seemed pale,

And he distressed, raised the matter, seeking

To cheer him, accustomed to regale

The ears of those delighted by listening

To the story of the lovers; sans respite,

He commenced to relate it the knight.

He told how, at Angelica’s request,

He had carried young Medoro to his farm,

Gravely wounded, where the lady then dressed

His hurt, and in a short space healed the harm;

Yet Amor had a deeper wound impressed

Upon her heart; his youthful grace and charm,

From a small spark, now kindled such a fire

That she burned within, with hot desire;

And forgetting that she was the daughter

Of the mightiest monarch in the East,

Now chose to be the wife of a soldier,

Driven by raging passion, to Love’s feast.

At the end of the tale the Count was further

Engulfed by sorrow, while his woe increased

When he was shown the gem Angelica

Had bestowed on them, in thanks, thereafter.

Canto XXIII: 121-124: And quits the farm

This conclusion to the story was the blow

That, with a single stroke, lops off the head,

When Love after tormenting his poor foe,

Is sated, and would strike the lover dead.

Orlando sought now to conceal his woe,

And yet his sorrow gained in strength instead,

And looked to issue forth in tears and sighs,

Despite himself, from out his mouth and eyes.

When he, at last, could give his grief full rein,

(Once in solitude, with none other by)

The tears poured down from his eyes, amain,

In a stream o’er his breast, while many a sigh

And groan he gave, and tossed about in pain,

On the bed, much like a man about to die,

Which felt harder than stone, and more stinging

Than a shirt of nettles, fierce and clinging.

It came to him, amidst that cruel travail,

That to that very bed, in which he lay,

The vile ungrateful woman, without fail,

Must oft have led her lover, on a day.

He loathed that couch no less, nor did sail

Less swiftly forth from there, I might say,

Than a farmer’s lad, about to close his eyes,

Springs from the grass, if a snake he espies.

The bed, the house, the herdsman, now had bred

Such hatred, in him, he could not remain,

Till the moon rose, or dawn broke in its stead,

That sheds a half-light, ere all things show plain;

But, with his steed and armour, forth he fled,

And the sombre heart of the woods did gain;

And when, at last, he felt he was alone,

Uttered his grief, in many a shout and groan.

Canto XXIII: 125-127: His lament

He ceased not from his weeping and moaning,

Nor could Orlando find peace, night or day,

He shunned the towns and villages, lodging

In the woods; there, on the hard ground, he lay.

He marvelled at his tears’ endless flowing,

How such a fount could rise from human clay,

How it held the breath for so many sighs;

Then spoke thus, amidst many groans and cries:

‘These can no longer be true tears that flow,

From my eyes in such a copious stream.

Naught could such fountains, on my grief, bestow,

For when my pain was half as fierce, I deem,

They ceased; now forth my vital liquids go,

Driven by the fires within me, it would seem,

Through the pathway of my eyes, no other;

So, cease my sorrows, and my life, together.

These, that are the index of my torment,

Are not sighs; no sighs are such; they fail,

While the pain I feel is ever-present;

Nor can my breast find peace but must exhale

Its anguish; for Love, who this fire has sent,

To scorch my heart, his wings create the gale.

Love, by what miracle have you so doomed

This heart to burn, and yet ne’er be consumed?

Canto XXIII: 128-136: Orlando gives way to wild frenzy

I am not what appears to others’ sight.

That which was Orlando’s, dead, interred;

While that ungrateful woman I indict,

Whose faithlessness my bitter wound conferred.

I am his spirit, parted from the light,

That suffers in this hell, doomed, at a word,

To wander as his shade, alone, above,

An example to all those that trust in love.’

The Count roved through the forest all that night,

And, at the rise of the diurnal sphere,

Fate brought him to the fountain, at first light,

Where Medoro’s inscription did appear.

When that source of injury met his sight,

It so inflamed him, so those lines did sear,

That all was rage, wild frenzy, hatred, ire.

He drew his sword, destruction his desire,

And cut away the writing and the stone,

And sent the fragments soaring to the sky;

Unhappy was that cave, the trees-half-grown,

Where ‘Angelica’, ‘Medoro’, met his eye!

Left in a state that day, such havoc sown,

That herd nor herdsman nevermore would lie

In their shade, while the fount, so clear and pure,

From that same anger was no more secure;

For trunks and branches, grassy turf and rock,

Orlando hurled into the lovely wave,

Thus, he, in its far depths, the source did block,

Till its clear flow no more the banks did lave.

At last, he ceased, for having run amok,

All bathed in sweat, to weariness a slave,

His strength now failed his hatred, anger, pride;

He fell upon the ground, and skywards sighed.

Tired, and afflicted, thus, he slumped to earth,

And gazing at the heavens, said not a word.

Without food or drink he lay, while the birth,

Thrice, of the rising sun new light conferred.

His wound pained him ever, with the dearth

Of hope; and both his mind to madness stirred.

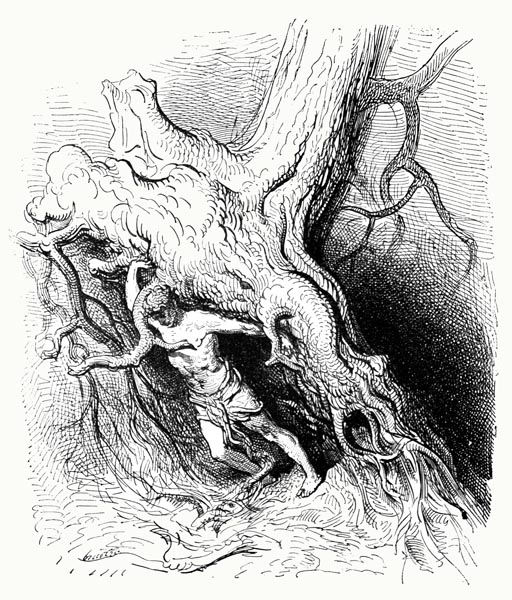

Moved to frenzy, at length, on the fourth day,

He stripped off his armour, casting it away.

Here he hurled his helm, and there his shield,

His chain-mail far off, his breastplate further;

All through the wood, and scattered far afield,

Lay the lodging places for his armour.

And then he rent his shirt, the rest did yield,

His hairy chest and back he did uncover;

And upon that dreadful frenzy, he began

The strangest ever seen in mortal man.

So fierce was his rage, so great his fury,

That his every sense was obfuscated.

The sword in his hand told not the story,

To his mind, of his deeds long celebrated;

(For wondrous deeds he’d wrought, bringing glory)

Nor double-bladed axe his hand awaited,

For his great strength and vigour served, alone,

To raze the pine-tree low, and split the stone.

He followed that by downing many a tree,

As if they were but fennel, mint or dill;

To elm, and rowan, showed little mercy,

Ash and beech, fir and ilex, all lay still.

As the fowlers in the field do, so did he,

Before the nets are spread; all at their will,

They flatten stubble, nettles, at a stroke;

Thus, he flattened many an ancient oak.

The shepherds, who heard the hillsides echo,

Left their flocks to scatter midst the wood;

They ran, from here and there, and proved not slow,

To seek the reason for it, if they could.

But, if beyond the point I’ve reached I go,

The tale may weary you; tis understood;

And so, I’ll choose, for now, to save my strength,

Rather than, thus, offend you with its length.

The End of Canto XXIII of ‘Orlando Furioso’