Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXII: Pinabel's Downfall

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXII: 1-4: Ariosto’s plea to the ladies

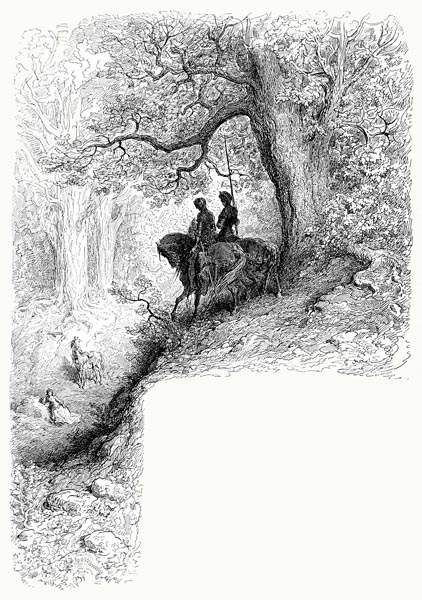

- Canto XXII: 5-10: Astolfo reaches France from the Levant

- Canto XXII: 11-15: He chases a thief to the enchanted mansion

- Canto XXII: 16-19: He consults Logistilla’s book, then contends with Atlante

- Canto XXII: 20-23: He uses the magic horn, then undoes the spell

- Canto XXII: 24-27: Astolfo chances upon the hippogriff

- Canto XXII: 28-30: And ponders what to do with his steed Rabicano

- Canto XXII: 31-33: Ruggiero and Bradamante find each other

- Canto XXII: 34-36: She insists he is baptised before they wed

- Canto XXII: 37-41: They meet a woman who tells a sad tale

- Canto XXII: 42-46: And decide to rescue the youth she speaks of

- Canto XXII: 47-51: She explains the dangers of their taking the highroad

- Canto XXII: 52-57: And tells of the four knights who guard the castle

- Canto XXII: 58-62: They approach the castle, and the first knight appears

- Canto XXII: 63-69: Ruggiero downs Sansonetto

- Canto XXII: 70-75: Bradamante recognises and pursues Pinabel

- Canto XXII: 76-79: Pinabel’s consort exhorts her champions to fight

- Canto XXII: 80-83: Ruggiero encounters Grifone

- Canto XXII: 84-88: By chance, the magic shield is unveiled

- Canto XXII: 89-94: Ruggiero drowns it in the well

- Canto XXII: 95-98: Bradamante slays Pinabel but cannot find Ruggiero

Canto XXII: 1-4: Ariosto’s plea to the ladies

You gracious ladies, dear to your lovers,

All you who rest content with but the one,

(Though tis clear, given so many others,

You’re rarely satisfied with him you’ve won)

Be not displeased if my tale discovers

Much to blame in what Gabrina’s done,

Nor if another verse or two you find,

That, indeed, condemns so perverse a mind.

Such was hers; and this task imposed on me

By one from whom I must not hide what’s true.

And, in executing it, I honour, surely,

All those who are sincere in what they do.

He who betrayed his master, wickedly,

Neither John nor Peter could wrong anew.

Yet still renowned is Hypermnestra’s fame,

Despite her sisters’ wickedness and shame.

For every one whose sins I choose to sing,

(For such the tales demand, that I recite)

My high praise of a hundred here shall ring,

And, brighter than the sun, display their light.

Now, turning to the work that I’m weaving,

In which, of their grace, many take delight,

I’ll speak of the Scottish knight, Zerbino,

That towards the sound of conflict did go.

Twixt two mountains, he entered on a pass,

From whence those cries arose, and in a while

Came to a vale, closed by their stony mass,

Where a knight was lying dead, of whom I’ll

Tell, but first must leave there, on the grass,

And quit France for the Levant, mile on mile

I must go, to seek Astolfo once more,

Midst his journey to find our western shore.

Canto XXII: 5-10: Astolfo reaches France from the Levant

I left him in that cruel Syrian city,

From which, with his formidable horn,

He’d chased those women full of enmity,

And so, himself from dreadful peril torn,

While obliging his friends to sail swiftly,

To fly that shore, and put the land to scorn.

Now, as I follow, he took, perforce,

The road to Armenia; such his course.

Through Anatolia, at a brisk pace,

He rode along, thereby reaching Bursa,

And thence crossing, o’er the Black Sea, to Thrace.

Up the Danube, through Hungary, later,

As his good horse had wings, he flew apace.

In less than twenty days, the border

Of Moravia he passed, then Bohemia,

And so crossed the Rhine, in Franconia.

Through the Ardennes he rode to Aix,

Then Brabant, and in Flanders went aboard;

With a southerly, the vessel made its way

At full sail, such speed did the wind afford;

And, by noon, there the shores of England lay,

Where he landed, once more the English lord.

He spurred his steed, and advanced so well,

That he reached London ere the shadows fell.

On hearing twas in Paris Otho lay,

(His father) since many moons ago,

And nigh every baron had made his way

To France, to follow his example so,

He returned to his vessel, that same day,

And downriver to the Thames’ mouth did go,

And thence, issuing forth with all sails set,

To Calais steered; full brisk the winds they met.

The light breeze to starboard had persuaded

The peer’s vessel to brave the open sea,

Which grew in force, and the sails invaded,

And so commandeered the ship, utterly;

While the captain was, swiftly, dissuaded

From doing aught but letting her run free,

Lest he, and all, were swamped; so, perforce,

He allowed the driving wind to set her course.

Now to starboard, now to port, they were thrown,

Here or there, o’er the waves, as Fortune wrought,

And, at last, to the Seine’s mouth they were blown.

To Rabicano the harness he now brought,

And our knight, armoured, took his way alone.

His good sword was at his side and, if he fought,

That which was worth a thousand men or more,

His magic horn, o’er his shoulder, he bore.

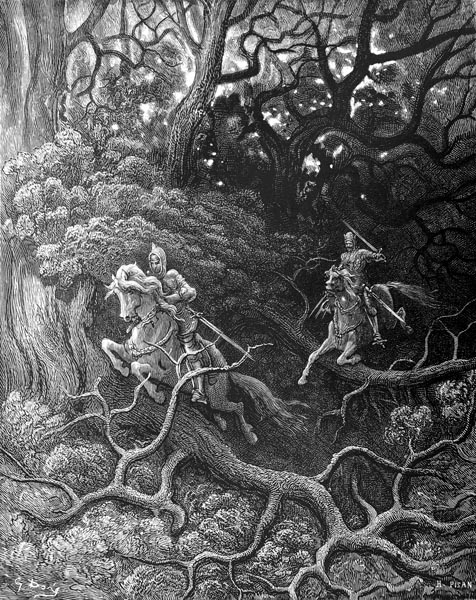

Canto XXII: 11-15: He chases a thief to the enchanted mansion

He traversed a forest, and swiftly came

To a fountain at the foot of a hill,

At an hour when the flock, close by that same,

Ceased to graze, and having eaten their fill

Rested in cave or fold, and, as the flame

Of the sun had raised a thirst, twas his will,

To doff his helm, then tether his courser,

And approach the fount, to drink its water.

He had scarce wet his lips, when a youth

Who had been lurking nearby, fast appeared,

Seized the horse, and leapt upon it, forsooth.

Then away, through the darkest woods, he veered.

Astolfo raised his brow, confused, in truth,

But on seeing the harm, as his head cleared,

Left the fountain behind, without drinking,

And sped after the lad, without thinking.

The thief a steady course did maintain,

Once he had, so suddenly, the creature got,

Often loosening, then tightening the rein,

And fled at now a canter, now a trot.

From the forest he entered on a plain,

Astolfo close behind, and reached the spot,

Where so many noble knights, in that mansion,

Were more captive than in a walled prison.

The youth vanished then, within that place,

On that steed that ran faster than the wind,

While Astolfo, far behind him in the chase,

Ran, within his helm and armour pinned,

And with his shield, so he found not a trace,

Of the lad that so blatantly had sinned,

Nor there did he meet with Rabicano,

Though he looked hard, and walked all round also.

He strode around, but his search proved all in vain,

Traversed the halls, rooms, and every gallery,

But, although he took nigh every pain,

Of the bold lad, not a sign did he see,

Nor caught a glimpse of Rabicano’s mane,

That finest mount for sheer velocity.

He searched, quite fruitlessly, I may say,

Up and down, and here and there, all that day.

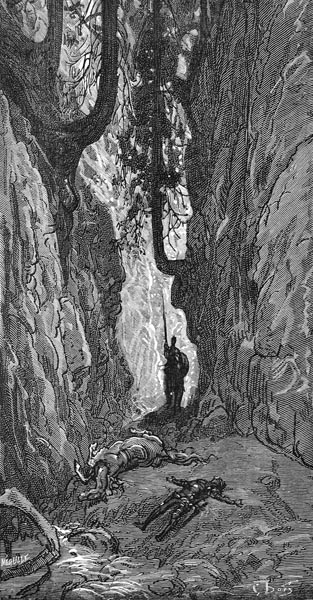

Canto XXII: 16-19: He consults Logistilla’s book, then contends with Atlante

Confused and weary, he roamed everywhere,

And finding that the place was enchanted,

Viewed the book that Logistilla the Fair

As a gift to him, in India, had granted,

So that if a spell, one new, strange, and rare,

Ever his own given powers supplanted,

He might find succour; in the index he

Sought the page that might yield a remedy.

Of that enchanted mansion he read much,

And there it was written how he might

Foil the enchanter, and his evil touch,

And so, untie the knot that held each knight.

Beneath the sill a spirit lay, and such

Was its power the captives were bound tight,

But raise the stone that buried it below,

And the rooms and halls as mere smoke would show.

All eager to bring that spell to an end,

And embracing the glorious enterprise,

Astolfo to the task his strength did lend,

To raise the marble flagstone was the prize;

But Atlante, seeing how he did bend

His arm to foil his art, and subtle lies,

Suspecting what was likely to ensue

Assailed him with enchantments, strong and new.

He, with devilish shapes and imagery,

Made him look quite other than before.

One perceived a giant, the next would see,

A peasant or a vile knight, old and hoar.

They, in the form in which he formerly

Appeared within the wood, Astolfo saw,

(The wizard, that is), and set upon him;

The prize Melissa took, to win from him.

Canto XXII: 20-23: He uses the magic horn, then undoes the spell

Ruggiero, Gradasso, Bradamante,

Brandimarte, Iroldo, Prasildo,

And many others, deceived entirely,

Attacked, bent on destroying Astolfo.

But remembering the horn, instantly,

He swiftly brought their foolish pride full low;

Though if not for the sound of its loud call

He had been slain, that must fight them all.

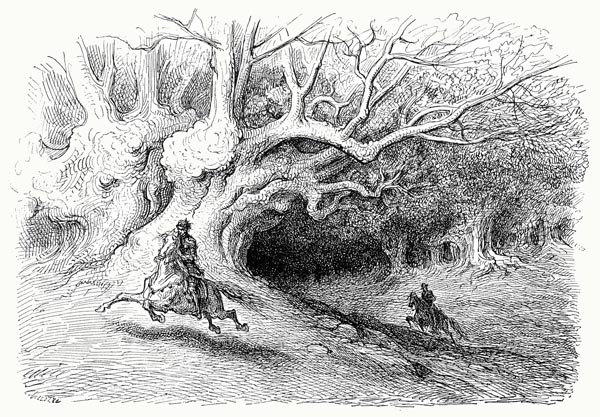

But as soon as the knight had blown the horn,

And raised its dreadful clamour all about,

Like doves that on hasty wings are borne,

At the sound of a musket, or loud shout,

They fled, while the necromancer, shorn

Of his powers, from his lair issued out,

Pale and trembling, and ran away, in fear,

Till the pain of the thing might disappear.

The warder and his prisoners were gone,

And many a courser broke from its stall,

While more than just a rope, tied fast, thereon,

Twould have needed that swift flight to forestall;

Not a cat or mouse remained, for ‘On! On!’

Was divined, in their own way, by them all;

And, with the rest, had vanished Rabicano,

Had he not been seized by brave Astolfo.

He, having chased the enchanter away,

Now raised the heavy stone above the sill,

And there, beneath it, sundry figures lay,

And other things I shall omit at will.

To destroy every spell, that on them lay,

He shattered all, that the dark space did fill,

As the book had informed him that he ought,

Thus, the mansion to smoke and mist was brought.

Canto XXII: 24-27: Astolfo chances upon the hippogriff

Then, tethered by a golden chain, he saw

Ruggiero’s hippogriff, the winged steed.

I speak of that mount Atlante the Moor

Had sent, that magic creature of rare breed,

To bear him to Alcina’s realm, then bore

Him back, as Logistilla then decreed,

From India to England, to reach France,

Over half the Earth’s watery expanse.

You may yet recall how Ruggiero

Had left the creature fastened to a tree,

When Angelica, naked, scorned him so,

And vanished from his presence suddenly.

The flying steed had departed also,

Returning to its master, Atlante,

Much to his wonder, and with him had stayed

Till the necromancer’s spell was unmade.

Now, Astolfo was more than pleased by this,

For the hippogriff would offer him a way

To fly o’er land and sea, as he might wish,

Thus, all he had not seen he might survey,

And circumnavigate the Earth, with relish,

For he knew that the creature could convey

Him thus, in any journey through the air,

Since he’d made ample trial of it elsewhere.

He’d proved its powers that day in India,

When by Melissa he was sped, swiftly,

From the realm of that wicked Alcina,

Who had changed him there, to a myrtle tree,

For he’d noted the response of the courser

To the rein, how it moved obediently,

So trained by Logistilla, who with care

Had taught Ruggiero to fly everywhere.

Canto XXII: 28-30: And ponders what to do with his steed Rabicano

To ride the hippogriff was his intent,

So, he saddled the creature, and then found

A bridle and bit from all those present,

That suited the steed, one strong and sound,

For many were still there, that had been meant

For the steeds that had fled o’er the ground;

And he was, thus, prepared to up and go,

Had he not then thought of Rabicano.

For he loved that steed, and with good reason,

None better while jousting with a lance;

And from remotest India he’d ridden

That fine courser to the fair land of France.

He pondered awhile, and his decision

Was to gift him, thus leaving naught to chance,

To some friend, not abandon him, a prey

To the first passer-by who came that way.

So, he gazed about the forest, to see

If some farmer or huntsman was around,

Who might lead the charger to the city,

And stable Rabicano there; but found

No sign of such, and waited, fruitlessly,

All day and night, yet, as dawn lit the ground,

Though the light was dim, as yet, where he stood,

He saw a knight approaching through the wood.

Canto XXII: 31-33: Ruggiero and Bradamante find each other

Yet I should seek, before I tell you more,

For Ruggiero and Bradamante.

The moment the horn’s magic call was o’er,

Our two warriors having fled most swiftly,

Ruggiero looked about him, and saw

What had been hidden from him, formerly,

All that Atlante’s powers had concealed,

And so, their own true faces were revealed.

Ruggiero now gazed at Bradamante,

And Bradamante at him, in wonder

That mere illusion, and but trickery,

Had led both mind and eyes so to blunder.

Ruggerio, with joy, clasped his lady,

Who the bright rose’s crimson did plunder,

While the first sweet flowers of love, intently,

He gathered from her lips, yet most gently.

A thousand times they embraced anew,

And, lovingly, they clasped each other tight.

So happy, and contented, were those two,

Their hearts could scarce contain their pure delight.

Great their grief, that a magic spell, untrue,

Had so wrought its enchantment on their sight,

That neither had recognised their lover,

Thus, many a joyful day was lost forever.

Canto XXII: 34-36: She insists he is baptised before they wed

Bradamante who was disposed to grant

Whate’er a wise and prudent virgin might,

So as to ease his pain, and make all pleasant,

So long as her honour received no slight,

Told the knight that he must ask her parent,

Duke Amone, for her hand, as was right,

(If the true fruits of love he now would gain,

For no objection would she then maintain)

Yet first must be baptised. He, not only

Would live a Christian for love of her,

As his father had been, and formerly

His whole past line down to his grandfather,

But would lay down his life, entirely,

And without a thought, he said, for her,

Crying: ‘Twould be naught if tis your desire,

To be baptised not with water but with fire.’

Then Ruggiero, that he might soon be wed,

Went to seek a means to the baptismal rite.

To Vallombrosa, Bradamante led

Her lover, till the abbey came in sight,

(Rich and fair, yet upon religion fed

And welcoming to many a brave knight)

Where they met, coming from the woodland chase,

A woman with a sad and mournful face.

Canto XXII: 37-41: They meet a woman who tells a sad tale

Ruggiero, ever courteous and kind,

But to women most of all, when he saw

How she wept, and seemed so troubled in mind,

Her lovely eyes all reddened, and full sore,

Felt pity for her then, and sought to find

What grieved her so, and thus did her implore,

After a courteous greeting, to say

What had caused her tears to flow, in that way.

And she, raising eyes full moist, yet bright,

Granted the knight a courteous reply,

And told him of the reason for her plight,

Since he had asked, with many a deep sigh.

‘You should know,’ she said, ‘most gentle knight,

My cheeks are wet with tears, because I cry

For a youth who, prisoned in a keep near this,

Has been condemned, in the flames, to perish.

Loving a lovely, young, and noble lady,

The daughter of Marsilius of Spain,

Neath a white veil, in a woman’s gown, he

A maiden’s looks and manners did maintain,

All so that he might lie with her, nightly,

With none suspecting either of the twain.

But none can e’er work such so secretly

That their affair is not exposed, finally.

One became aware, and told another,

And they the rest, till to the king twas fed,

And then there came a faithful follower,

That ordered they be taken in their bed.

In the fortress then, the one and the other

To separate cells within the keep were led,

And now there is scarce time for anyone

To save the youth, before the day is done.

I fled, swiftly, so that I should not see

Their cruelty, for he must die by fire;

And naught could prove such bitter grief to me

As to behold him burnt upon that pyre;

Nor could I after that live happily,

But rather in pain and sorrow suspire,

Were I then to recall the vicious flame,

That, searingly, upon his body came.’

Canto XXII: 42-46: And decide to rescue the youth she speaks of

Bradamante heard her tale, and appeared

Greatly troubled at heart, by her story,

As anxious for the youth, for whom she feared,

As if her brother knew such cruelty;

Nor without cause were her own eyes teared,

For of him you shall hear later, from me,

She turned to Ruggiero then, and cried:

‘Shall this youth our brave weapons be denied?’

Then to the weeping maid, Ruggiero said:

‘Be of good comfort, and but place us two

Within the walls and, if he be not dead,

He shall not die, and that I promise you.’

For Ruggiero his lover’s face had read,

And saw the kindness there, the pity too,

And felt, within, a flame, a fierce desire

To rescue this poor youth from out the fire.

Then, to the melancholy soul, he cried

Viewing her flowing tears: ‘Why do we wait?

Here is there need for aid, not tears; but ride

To where this youth is; once beyond the gate,

We’ll save him from lance and sword beside.

So, we promise, yet pray we be not late,

Show forth the way, ere we delay too long,

And he be burnt, and love be dealt a wrong.’

The noble speech, and the proud semblance,

Of this pair, who such brave ardour showed,

Brought fresh hope to her, whom circumstance

Had robbed of thoughts of aid, as on she rode,

Yet, fearing the distance less than mischance,

And that some obstacle the way bestrode,

Such that they might make their way in vain,

The maiden lingered; heart filled with pain.

And then she said: ‘If the way ran but straight,

A highroad, clear and wide, to that same place,

Then there might well be time to reach the gate,

Before the youth those dreadful flames must face,

But we must take a path, such is our fate,

That needs a day or more, and God’s good grace,

To bring us there, and so, when we come near,

We shall but find the youth is dead, I fear.’

Canto XXII: 47-51: She explains the dangers of their taking the highroad

‘Why not the highroad?’ asked Ruggiero.

‘Because that way, a mighty castle lies;

The Count of Poitiers is all men’s foe,’

She answered, ‘and a law he did devise

Unjust and savage, but three days ago,

This Pinabel, who knights and ladies tries,

He the son (the worst man living ever),

Of Count Anselmo of Altaripa.

No noble knight nor lady may pass by

Without incurring harm and injury,

Both are despoiled of their horses thereby,

And his armour, and her robes, are his fee.

And no finer knights with him, there, ally,

No finer for many a year shall France see,

Than the warriors who have sworn, being four,

To maintain Count Pinabel’s savage law.

How this custom (which is but three days old)

First began, I shall relate to you, sir knight,

This same law which they have sworn to uphold,

Of which you may judge if tis wrong or right.

Pinabel has a lady who, I’m told,

Is so vile and bestial none match her quite:

She, on a day, when the Count was beside her,

Encountered a bold knight, who scorned her.

The knight, because it had caused her laughter,

To view the crone carried on his crupper,

Had fought with Pinabel, of little power

But overweening pride, and gave him bother,

And made her dismount as well, then put her

To the proof, whether she was lame or other;

For he left her to walk, and took her dress

To adorn the crone, much to her distress.

Being stranded, on foot, and filled with spite,

And longing, for revenge, nay thirsting,

She joined with Pinabel, who, all in sight

That bodes ill, embraces, ever-willing,

Declaring she’d not rest, or day or night,

Nor ever be content again, till, sighing,

A thousand knights and ladies paid her tax,

Left to walk, sans dress or armour on their backs.

Canto XXII: 52-57: And tells of the four knights who guard the castle

As it happened, four knights arrived, that day,

At his fortress, mighty warriors indeed,

Who’d journeyed from afar, upon their way,

Four whom, to his realm, their travels did lead.

Of such valour our age ne’er saw in play

Such fine and warlike knights, all folk agreed:

Aquilante, Guidon Selvaggio,

And Grifone they, with Sansonetto.

Pinabel, full of seeming courtesy,

Received them at the place of which I’ve told,

But, that night, he had them seized suddenly,

In their beds, nor loosed those warriors bold

Till he had made them swear that they would be

His champions, for a thirteen-month, all told,

And of their armour and their steeds deprive,

Whatever brave knights-errant might arrive;

And any lady riding at their side,

Must go afoot, and be stripped of her dress.

Thus constrained, the four were forced to abide

By his terms, though with anger and distress;

And, against the four, it seems none can ride,

But are forced to walk, their ladies no less.

Many a knight has come, and gone, indeed,

Bereft of his fine armour, and his steed.

Their rule is that whichever of them first

Rides from the keep (as determined by lot)

He fights alone, but if he has the worst

Of the encounter, then, rightly or not,

The other three, all in conflict well versed,

Must seek to slay the foe upon the spot.

And imagine how powerfully they fight,

When each man alone is peerless in might.

Given the importance of our mission,

No distraction befits us, nor delay,

And so, we should avoid such diversion,

For grant that you be victors in the fray,

(Since your appearance yields that impression)

Tis a matter that might well take all day,

And were it that long ere we brought him aid,

He’d have perished in the flames, I’m afraid.’

‘Pay no regard to that!’ cried Ruggiero,

‘But let us, rather, do whate’er we may.

Let Him who rules above, the rest bestow,

Or Fortune, if He wills that she holds sway;

Indeed, the outcome of this joust will show

If we can aid the youth, this very day,

Who for so slight and baseless a reason,

They will burn, for such is your impression.’

Canto XXII: 58-62: They approach the castle, and the first knight appears

Without another word, the maid led on

Towards the castle, by the shortest road,

And no more than three brief miles had they gone,

Before they reached that dangerous abode

Where many a brave knight had been undone,

And armour, dresses, even lives, were owed,

In fee; at sight of them the sentinel

Beat twice upon the castle’s warning bell.

And behold, in great haste, from out the gate,

On a nag, came a fellow old and staid,

And he approached them, crying: ‘Wait, now, wait!

Halt, sirs, for here a levy must be paid;

Should you know naught of our law passed of late,

Then I am here that it might be relayed.’

And then the three he straight began to tell

Of the custom brought about by Pinabel.

He proceeded to instruct them further,

As he’d instructed many a brave knight,

‘Let the lady be unrobed,’ said this elder,

‘And forgo, sirs, your steeds and armour bright;

Twere unwise to put yourselves in danger,

Here, four warriors wait, eager for the fight.

Dresses, armour, mounts, you’ll find elsewhere,

But loss of life no mortal can repair.’

‘Enough! Enough!’ bold Ruggiero cried,

‘I am informed of this and hither rode

To prove that I am what my heart, inside,

Declares I am, and ill doth that now bode

To all who threaten; such shall be denied

Horses, armour, and robe, where none are owed.

And my comrade here, I, as surely, know,

For such words alone, little will bestow.

But, by Heaven, let me see before me,

Those who would obtain both horse and armour,

For we must pass beyond the hills, swiftly,

And have but little time, thus, to linger.’

‘O’er the bridge, to perform the task,’ cried he,

‘Behold, he comes.’ Nor was he in error.

For thence a knight came, crossing o’er the moat,

With white flowers upon a crimson surcoat.

Canto XXII: 63-69: Ruggiero downs Sansonetto

Bradamante begged her Ruggiero

To allow her, of his great courtesy,

To lay this fine and handsome warrior low,

Whose costume was so rich and flowery,

But could not move the knight an inch, and so,

Was forced to leave him to his chivalry,

For he wished to perform the task alone,

That Bradamante to his skill might own.

Ruggiero asked who the knight might be

That was the first to issue from the gate,

‘Tis Sansonetto,’ the maid said, ‘tis he,

By the flowery crimson coat, he wears of late.’

Without a word they wheeled, separately,

But their onlookers had not long to wait,

For now, with lowered lances, on they came,

Spurring their chargers, set to kill or maim.

Meanwhile, from the fort, came Pinabel,

With many men on foot, all ready now

To seize the horse, with the armour as well,

From the knight, once he had made his bow.

The two brave knights, each aiming to impel

The other from his seat, should fate allow,

Gripped their strong lances, made of native oak,

Full two palms thick, preparing for the stroke.

More than ten of these, had Sansonetto

Ordered cut from a mighty, living tree,

In the woods nearby; these he did show

To his opponent, most courteously,

And then had one of them borne to his foe,

And took another for himself, equally,

While an adamantine breastplate and shield

Were needed to withstand such in the field.

With lances that might pierce an anvil through,

(So sharp, and strong, their tips appeared to be)

They came together, in mid-course, those two,

Though but found each other’s shield, mutually.

Ruggiero’s (that an imp had wrought when new,

Naked and sweating) released him wholly

From fear; Atlante ordered it, of old;

While of its powers I’ve previously told.

For I’ve explained, before, with what great force

Its enchanted light struck upon the eye.

All that saw it were blinded in their course,

And half-dead, or stunned, upon the earth did lie.

Unless the knight to it must make recourse,

He kept the shield concealed, but ever nigh;

And it was thought to be impenetrable,

Since it was unharmed in every battle.

Sansonetto’s wrought by a lesser art,

Could not endure the force behind that blow;

As if struck by lightning, it flew apart,

The steel giving way, its core did show;

The steel gave way, the lance-tip, thus, did dart

Towards the ill-protected arm below,

So that Sansonetto was forced to yield,

And, despite himself, toppled to the field.

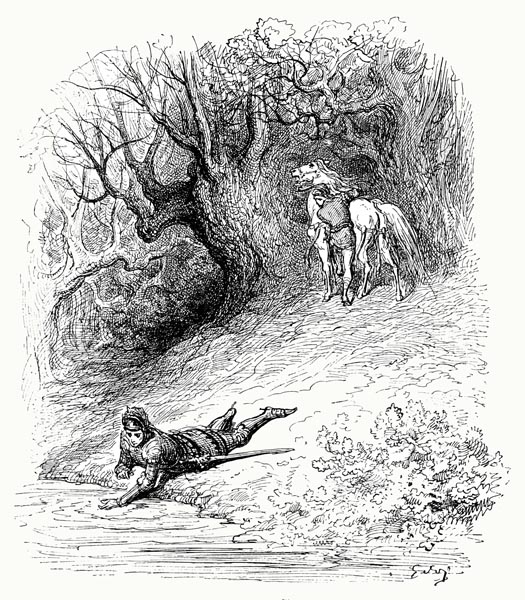

Canto XXII: 70-75: Bradamante recognises and pursues Pinabel

This was the first, then, of the band of four

That maintained the custom of the keep,

Who had failed to gain the spoils, as before,

But had left his saddle, in a sudden leap.

He who smiles must sometimes weep the more,

And may find that Fortune lies fast asleep.

The sentinel now beat the bell again,

To signal to the other knights his pain.

Meanwhile, Pinabel neared Bradamante,

Seeking to know who was this knight

That had unhorsed his champion so swiftly,

And with such skill and valour, in the fight.

God’s justice, to ensure that he might be

Rewarded as was due, and as was right,

Had led him to appear on the courser

He’d seized from Bradamante earlier.

For it was exactly eight months before,

(If you recall) that, together on the way,

This Maganzese thrust her to the floor

Of a cleft before Merlin’s tomb; that day,

She might have died, yet a bough did ensure

Her fall was broken, or good Fortune, say,

Though Pinabel had made off with her horse,

Thinking the cave her tomb, without remorse.

Bradamante knew the steed, instantly,

And, by the horse, the iniquitous count.

Hearing his voice, and seeing him clearly,

She gazed at him more closely, and his mount.

‘Here is the traitor, without doubt,’ said she,

‘Brought here by his sin, to render account,

And receive all he deserves for his treason,

That offended me, and for no good reason.’

To threaten him with vengeance, and to set

Her hand upon her sword, and then advance,

Was a moment’s work; nor did she forget

To bar the road, so he might not, perchance,

Flee, like a fox to earth, for she had met

That thought of his with her own lowered lance;

He shouted aloud, and fled, hopelessly,

As soon as that mighty weapon he did see.

Pale and dismayed, the villain spurred away,

Whose last hope lay, indeed, in taking flight,

While Dordona’s warrior-maid her sword did lay

To his flanks as he went, and pressed the knight,

Hounding him close, pursuing him alway.

Loud the sounds rose to the forest’s height,

Though naught of this was known yet at the fort,

Where Ruggiero attracted every thought.

Canto XXII: 76-79: Pinabel’s consort exhorts her champions to fight

The fort’s remaining champions, meanwhile,

Had issued forth to maintain the battle,

Bringing with them the woman, full of bile,

That had devised the custom, base and evil.

The faces of those three knights, free of guile,

Who had rather died than serve the devil,

Burned with shame, while their hearts were full of woe,

At being forced to counter one man, so.

The cruel courtesan who had designed

The rite, which by the four was executed,

The content of their oath, once more, defined:

To avenge her in fight, they were recruited.

‘If this lance, alone, your foes can unbind,

Cried Guido, ‘why then is aught else mooted?

Why fight in company? And if I lie,

Off with my head, I am content to die!’

So said Aquilante, and Grifone,

For both knights preferred to fight one on one,

Or, instead, be taken, and die swiftly,

Than combine, and see scant justice done.

The woman cried: ‘Why waste words, fruitlessly,

Since it brings no profit? For here is none.

I brought you here to win the man’s armour

Not with some new law replace the other.

When I had you in prison, there was time

To offer your excuse, now tis too late;

You must apply the law to other’s crime,

Not, with a false tongue, seek to alter fate.’

Ruggiero cried: ‘Behold, now, my prime

Steed; its saddle and cloth are new of late;

And my fine armour, and the maiden’s dress;

Why linger, if these things you would address?’

Canto XXII: 80-83: Ruggiero encounters Grifone

The mistress of the keep urged her troops on,

While Ruggiero summoned them to fight,

Till all three charged forward with abandon,

Though with shamed expressions, blushing bright.

Foremost were the one and the other son,

Of Burgundy’s marquis, then came the knight,

Guidon, who rode a heavier charger

And reached them slowly, and a little later.

Ruggiero bore his lance, the very same

That had overthrown brave Sansonetto,

And the shield whose use Atlante did claim

On the Pyrenean height, whose magic glow,

Too much for human eyes, did almost maim

Folks’ vision, for it struck them like a blow;

To this, Ruggiero, as a last resource,

When in the gravest danger, made recourse.

But three times only had he felt the need

(And ne’er but in great peril) for its light.

Twice, when from Alcina he did speed,

And to a calmer region made his flight;

The third when that vile orca that did feed

On human flesh had plunged down out of sight,

That would have sought to eat the naked maid;

She, so cruel to the knight that brought her aid.

But for those three occasions, well-concealed

He kept the shield, veiled in such a manner

That the thing could be readily revealed,

If he was ever in need of succour.

With it there, he might enter on the field,

Which he did now, and with as much ardour

As if the three knights he encountered then,

Were less to be feared than little children.

Canto XXII: 84-88: By chance, the magic shield is unveiled

Ruggiero’s lance struck Grifone

Where the top of his shield met the visor,

Who swayed to either side, perilously,

Falling earthwards, at last, from his courser.

He too had aimed at Ruggiero’s shield,

The glancing blow fell slantwise however.

The lance-tip sliding, as he was upended,

Wrought the opposite of that intended;

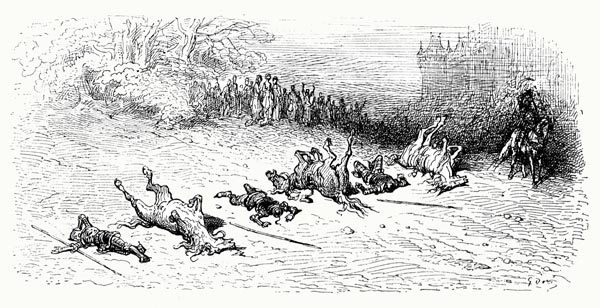

For it tore apart the concealing veil,

That hid its dangerous enchanted light,

The intense splendour serving, without fail,

To rob all those who gazed there of their sight.

Aquilante, close on his brother’s tail,

Tore off the rest, so that it blazed outright.

The pair were, by its brightness, rendered blind,

With Guidon, who was riding close behind.

This way and that, they tumbled to the ground,

Nor did the light confound their sight alone,

For every sense that magic did astound.

Ruggiero, to whom all this was unknown,

As he wheeled his mount about, turning round,

Sword in hand, to reap the harvest he’d sown,

Found not one mounted foe for him to fight,

For on the earth lay, winded, every knight.

His opponents he viewed, and the footmen,

And the ladies who had come from the hall,

And the horses panting from their sudden

Tumble, as silence now embraced them all.

At first, he marvelled, and then the hidden

Shield, he realised, was stripped of its pall,

Which hung down on the left, and no longer

Served to guard against unwanted error.

He swiftly turned and, in turning, sought

For a sight of his beloved warrior-maid,

Then rode to where the joust was first fought

And where, he believed, she must have stayed.

Not finding her, she must have sped, he thought,

To bring the poor condemned youth her aid,

Fearing lest he’d been offered to the flames,

While they were all delayed in warlike games.

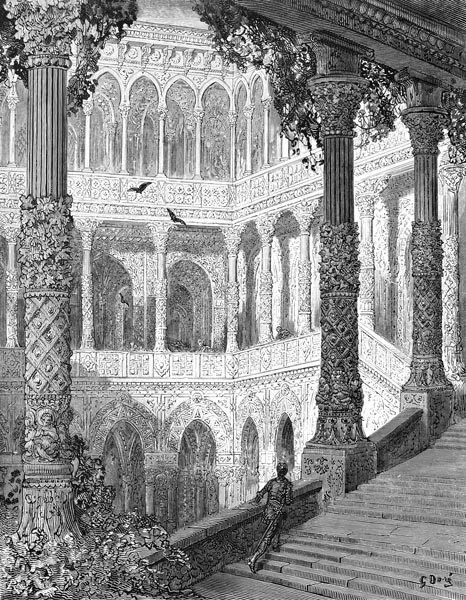

Canto XXII: 89-94: Ruggiero drowns it in the well

He found the maiden who had led them there,

Slumbering among the rest; set her before

Him, on the steed, still asleep and unaware;

Then, greatly troubled, took his way once more.

He veiled the shield (the face, as yet, was bare)

With her cloak, its powerlessness to ensure,

And, once the enchanted thing was hidden,

Her senses she recovered, unbidden.

Away he rode, his cheeks suffused with shame,

Nor did he dare his crimsoned face to raise,

Since all, it seemed to him, were like to blame

A victory, in truth, worth little praise.

‘What shall I do? he thought, ‘to clear my name

Of shameful error, and its stain erase,

Twill be said my conquests, past and present,

Were simply due to powers of enchantment.’

While he rode on, debating in his mind,

Ruggiero came upon what he sought,

For beside the track there lay, as if designed

To assist him, a deep well, soundly wrought.

There the cattle, in the summer heat, could find

A trough from which to drink. ‘Tis how,’ he thought,

‘I may shun further shame, and so ensure,

That you, enchanted shield, work harm no more;

Once you are gone, the last time shall this be:

That I earn shame, through the powers you command.’

Thinking so, he dismounted, eagerly,

And took a large, and heavy, stone in hand,

Which he fastened to the shield, full tightly,

And threw both into the well, as he’d planned,

Crying: ‘Be drowned now, this your sepulchre;

You, and my shame, lie hid, forever, there!’

The well was full to the brim with water;

Full heavy was the stone, as was the shield.

They sank into the depths, bound together,

Both by the liquid element concealed.

Yet the fact of his deed spread by Rumour,

That, wandering wide, his noble act revealed,

And trumpeted it, everywhere, he found,

In France and Spain, and all the lands around.

Once that strange tale, by word of mouth, had passed

Through all the world, then many a bold knight

Undertook the quest for that which he had cast

Into the depths, all hoping to alight

Upon the forest, and the well, at last,

As yet unknown, that hid the shield from sight;

For the maid that told the tale was unclear

Where the well lay, nor if twas far or near.

Canto XXII: 95-98: Bradamante slays Pinabel but cannot find Ruggiero

Once Ruggiero departed from the field,

Where he’d conquered. and with little trouble,

Where, like to men of straw, the four did yield

Who’d championed Pinabel and the castle,

Withdrawing the shield, he stole the light

That did all folk confound and bedazzle,

And the many who had lain there, half-dead,

Rose to their feet, in wonderment, instead.

Nothing else did they speak of all that day,

Among themselves, but of the strange event,

And how each of them had, in deep dismay,

Been conquered by the light, ere it was spent,

Or rather removed, till news came there way

Of Pinabel, whom, they’d found, was absent.

Count Pinabel was dead, they were advised,

But by whom, as yet, no one had surmised.

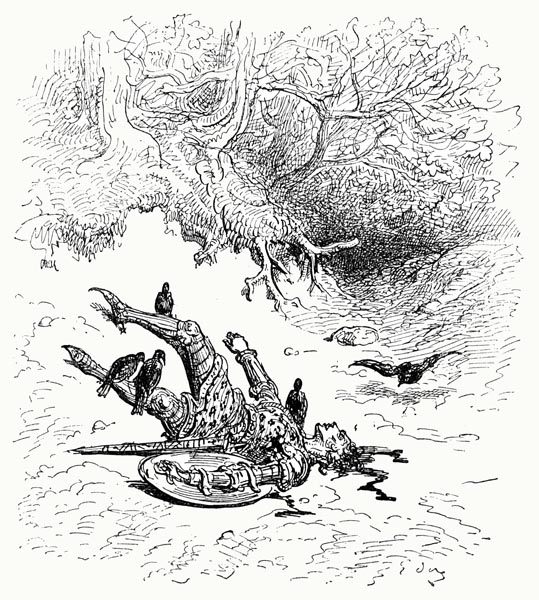

Twas the ardent Bradamante, meanwhile,

Who had pressed Pinabel hard, in flight,

Then half her blade had buried in that vile

Wretch, in every place, with all her might.

Once she’d removed that man of evil guile,

That upon the lands around had laid his blight,

She, from the place that witnessed it, did go,

With the steed he had stolen long ago.

She wished, then, to return to Ruggiero,

But could no longer find the way she’d come,

And thus, o’er hill and dale, she wandered slow,

Searching half the forest that she’d issued from;

But her ill-fortune now pursued her so,

She failed to find the way to him, in sum.

Another canto must speak of the knight,

O you, that in my story take delight.

The End of Canto XXII of ‘Orlando Furioso’