Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XX: The City of Women

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

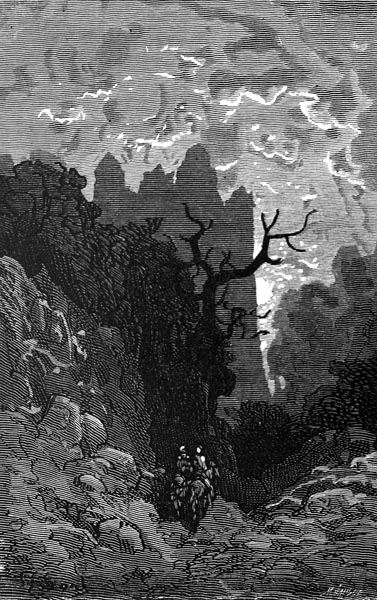

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XX: 1-3: Ariosto in praise of women

- Canto XX: 4-8: Guidon reveals his name and origin

- Canto XX: 9-13: He is questioned regarding the city’s strange custom

- Canto XX: 14-18: Of Phalantus and the women of Crete

- Canto XX: 19-21: The women are left behind in Syria

- Canto XX: 22-27: Orontea proposes they remain and take revenge

- Canto XX: 28-31: They change the law to ensure progeny

- Canto XX: 32-35: Each woman might retain one male child

- Canto XX: 36-38: Elbanio arrives, of whom Orontea’s daughter hears praise

- Canto XX: 39-46: Alexandria, in love with him, conveys his plea

- Canto XX: 47-54: The council consent to Orontea’s request

- Canto XX: 55-57: Elbanio completes the two trials

- Canto XX: 58-64: Guidon ends his tale

- Canto XX: 65-69: Astolfo declares himself kin to Guidon

- Canto XX: 70-76: Marfisa calls on Guidon to join forces

- Canto XX: 77-81: He ensures their means of escape

- Canto XX: 82-86: The companions fight their way to the gate

- Canto XX: 87-91: Astolfo sounds the magic horn

- Canto XX: 92-98: All but he set sail

- Canto XX: 99-101: The company, minus Astolfo, make their way to Marseilles

- Canto XX: 102-105: Marfisa quits the other four

- Canto XX: 106-110: And comes upon an aged crone, and then Pinabel

- Canto XX: 111-116: Marfisa disposes of the knight

- Canto XX: 117-120: They encounter Zerbino who insults the crone

- Canto XX: 121-127: Marfisa unseats him

- Canto XX: 128-134: She departs; the crone deduces that he is Zerbino

- Canto XX: 135-138: She has news of his beloved Isabella

- Canto XX: 139-144: But withholds her whereabouts

Canto XX: 1-3: Ariosto in praise of women

The women of ancient times wrought many

A fine thing in battle, and for the Muse,

While the worth of their deeds, and the beauty,

Have oft, the wide world o’er, received their dues:

Camilla praised in warfare, o’er any,

By Virgil, and that Harpalyce who’s

Own father she saved, Sappho, Corinna,

Glowing stars, whose light will shine forever.

Women have always shown their excellence

In all the arts they’ve sought to command,

And every person that, with care and sense,

Has read the histories, will understand

That if, now, through some evil influence,

Such are absent or dismissed out of hand,

It will pass, with those who hid their glory

Whether through blind ignorance, or envy.

For such is the virtue, it seems to me,

That is possessed by women, in this age,

With pen and ink, they’ll win celebrity

In years to come, who grace the written page,

(You and your works, consigned to infamy,

You evil tongues, that now command the stage.)

Their praise will be sung in such a manner

As to surpass that earned by Marfisa.

Canto XX: 4-8: Guidon reveals his name and origin

To turn, once more, to her: the warrior-maid

Refused not to declare her given name,

To one who had such kind attention paid,

For he had first agreed to do the same.

She nigh discharged the debt ere it was laid,

So keen was she to hear the knight proclaim

His identity ‘Marfisa,’ she cried,

‘Am I!’ for she was famous, far and wide.

Since it was his turn to speak, the other

Began with this preamble: ‘None of you

Will fail, I think, to know of my father,

For not just France and Spain, but Pontus too,

Ethiopia, India, and further

Countries still, far lands both ancient and new,

Know Chiaramonte’s House, and the knight

Rinaldo, that slew Almonte, in fight,

And Chiariello, and King Mambrino,

And sacked their royal kingdom; my mother

Bore me to Amone, of whom all know,

Where the Danube’s nine streams (or more) enter

The Euxine, for, a wanderer he did go

To that region, and there I did leave her,

A year ago, now, she with grief oppressed.

Since to seek my kin in France is my quest.

I failed to complete my journey, though,

For a southerly gale impelled me here,

Ten months, and more, have I been prisoned so;

I count the hours; each day is like a year.

And I am named Guidon Selvaggio,

One little tried, or known as yet, I fear.

Argilon of Meliboea I slew,

And the rest of that band of ten died too.

I proved myself with the maidens also,

And ten share my bed, to my pleasure;

The very noblest the city can show,

And the loveliest, by any measure.

These ten are in my sole command, although

I wield the sceptre o’er the rest at leisure;

And Fortune will grant this to any knight

That overcomes the ten, with skill and might.’

Canto XX: 9-13: He is questioned regarding the city’s strange custom

The warriors asked Guidon to explain

Why so few males dwelt there in the city,

And how these women did such power retain

While elsewhere one would see the contrary.

‘I’ve heard, since I’ve lived here, time and again,

The reason for it all, and their story,’

Guidon replied, ‘and, indeed, I’ll tell it

To you, if that would please, as I heard it.

When after twenty years the Greeks returned

From Troy (the siege itself had lasted ten,

And then, for ten more, they were tossed and turned

By the waves, the winds adverse once again)

They found that their womenfolk who had yearned

For comfort in their absence, had been fain

To take up with young lovers in their stead,

So that they might not freeze, alone, in bed.

The Greeks found that others’ children filled

Their houses, and yet, by common consent,

They pardoned their wives, their anger stilled,

Knowing that twas not done with ill intent,

But rather that without them they were chilled.

Yet the adulterous issue forth they sent,

To seek their fortunes elsewhere; an offense,

They thought it, thus to live at their expense.

Some were exposed, while others were concealed,

And kept alive, by many a mother,

While those who were of age roamed far afield,

And were employed at one task or another.

Some fought abroad, others chose to wield

The pen, or practice trades, or agriculture;

This one served in court, that as a shepherd

(Pleasing to her that reigned below, I’ve heard).

Now, among all those who left, was the son

Of that most cruel queen, Clytemnestra,

Fresh as a lily (eighteen years he’d won)

Or a rose that, from the thorns we gather.

Arming a ship, he sailed, beneath the sun,

To roam the wide seas in search of plunder,

With a hundred youths in his company,

All of an age, picked from out that country.

Canto XX: 14-18: Of Phalantus and the women of Crete

In those days the Cretans had banished

The cruel Idomeneus from their island.

To ensure their security, they wished

A wealth of men and weapons to command.

The mercenary band he established,

This Phalantus, for such, you understand,

Was the youthful soldier’s name they now chose

To guard Dictynna’s walls from their foes.

Among the hundred cities of fair Crete

Dictynna’s was the richest and most fair,

With lovely and amorous maids replete,

That from morn to night in joyous sport did share;

And as with kindness they would ever greet

The stranger, his men were welcomed there,

Such that little remained ere they were made

The lords of all those households where they stayed.

Young and handsome were they, every one,

(The flower of Greece Phalantus selected)

Such that, at first sight, the hearts they won

Of those maids, and no man was rejected.

And not only were they handsome, bar none,

But skilled in bed, as those maids expected.

Thus, so grateful, in a few days, they proved

That, above all else, those warriors were loved.

After the war was ended, by accord,

For which, indeed, Phalantus had been hired,

Their being no further need for the sword,

Since naught was left to gain, nor aught required,

The men thought, once more, to roam abroad,

Not something that the women there desired,

For, lamenting, many a tear they cried,

More than if their fathers had up and died.

Thus, the maidens begged the young men to stay,

But, failing that, not wishing to remain,

Both left fathers, brothers, sons, sailed away,

Taking, of their wealth, all they could obtain

In gold and gems, departing, on a day,

With a secrecy, they’d worked to maintain;

For the plan that they made was so well hid

Not a man left in Crete knew what they did.

Canto XX: 19-21: The women are left behind in Syria

So fair was the wind, so perfect the hour,

When Phalantus chose his moment to flee,

They were out of sight of the highest tower,

Ere the city woke to its misery.

This shore, then uninhabited and dour,

Received them, as they wandered o’er the sea,

Here they rested, and here found safe shelter,

To weigh the stolen fruits of their labour.

And they remained here, for ten days in all,

Sating themselves with amorous pleasure,

But as often happens, things began to pall,

With endless play, and abundant leisure.

All the youths were soon inclined to recall

Their lost days of freedom without measure,

For there is ne’er a burden so heavy

As a love of which the heart doth weary.

They were eager for plunder and for gain,

(None thereabouts had payment to bestow)

Well-knowing more was needed to maintain

Their many paramours than shaft and bow;

And so, they left the women to complain,

While off, with their weapons, they did go,

And there, in Puglia, the shore quite near,

Founded Tarentum, or so twould appear.

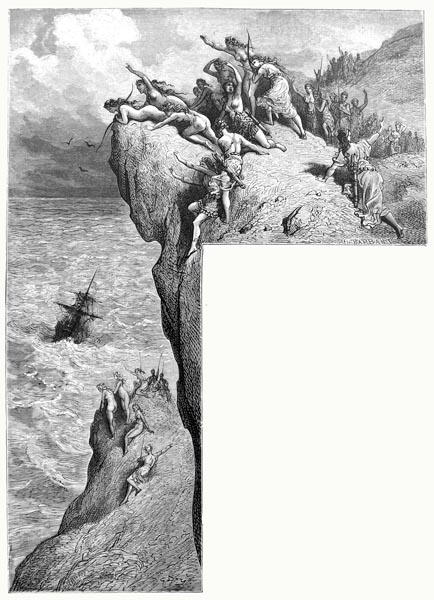

Canto XX: 22-27: Orontea proposes they remain and take revenge

The women, finding that they’d been betrayed,

By these lovers, in whom they’d placed their trust,

Were so troubled, for days, and so dismayed,

They sat like lifeless statues, in the dust.

But finding that tears small difference made,

Though their treatment was unearned, and unjust,

They began to consider, somewhat late,

What they might do to remedy their fate.

Some now proposed that they return to Crete,

(For they might win them better husbands there),

And throw themselves at their fathers’ feet,

Rather than languish in the desert air,

Or in the woods around, with naught to eat,

Perish, in time, of hunger and despair;

Others proclaimed that such they’d never do,

They’d drown first, twas more honourable too;

For twere better to embrace harlotry,

In this world, or be a slave or beggar,

Than to sail for home, hoping for mercy,

Where, for their sins, they would surely suffer.

Such schemes they offered in their misery,

Each one no less dreadful than another,

Till Orontea rose, their hearts to win,

That to King Minos traced her origin,

The youngest and the fairest of that band,

The shrewdest, and the least prone to error,

She’d loved Phalantus, and left her land,

And her father, to follow him, however.

She showed by the words she did command,

That her generous heart burned with anger.

And, rejecting all that had gone before,

She spoke, to this effect, upon the shore.

She would not leave the place where they stood.

She thought the ground was fine, the air healthy,

Limpid streams flowed there, with many a wood

To grant them shade; the shore was flat, mostly.

This seemed a natural harbour, which would

Grant fair shelter from the gales to every

Stranger, merchant, and mariner,

That offered trade with Egypt, and Africa.

Here they might rest, and vengeance take

On the male sex, that had so offended.

She wished each ship and crew, the wind did rake,

That sheltered there, and thought their ills ended,

Might be sacked, burnt, slain, for honour’s sake,

Nor mercy to a single man extended.

So was it put, and so was it agreed,

And a law, to enshrine it, was decreed.

Canto XX: 28-31: They change the law to ensure progeny

When it blew a gale, then they would gather

And, fully armed, hasten to the harbour,

Led by the relentless Orontea,

That had made the law, and was their ruler;

And all the vessels that here sought shelter

They set ablaze, and the crews did murder,

Leaving no man alive to spread the word,

In any place; thus, the tale went unheard.

They lived so, for many years, alone,

At enmity with the male sex, entire,

Then realised the loss would prove their own,

Unless they changed the custom there; for dire

The consequence if no fresh seed were sown;

The law would be scorned, and all conspire

To end it, lest their barren realm should fail,

And all they had hoped eternal, prove frail.

Tempering somewhat that law’s harsh rigour,

From all the vessels driven to that bay

In the next four years, they chose to gather

Ten bold and handsome knights for their prey,

Who might last against a hundred, moreover,

When engaged with them in amorous play.

A hundred they; and so, from out the men,

One lover was assigned to every ten.

Of those not chosen, many were beheaded

As failing to meet their main requirement.

But these ten were all approved, and bedded,

And allowed a share in their government,

First made to swear, to those they wedded,

That if any other men that way were sent,

They would put them to the sword, equally,

To none would they show a trace of mercy.

Canto XX: 32-35: Each woman might retain one male child

When the women found themselves with child,

Fearing to rear too many that were male,

(Since to that they remained unreconciled,

Lest their children oppose them, and prevail,

And the laws and statutes they’d compiled

Be set aside, and men their rule assail)

They, while their babes were still young, took care

That no rebels should be bred, to their despair.

Lest to the male sex they be subjected,

Each mother was allowed one son alone,

Any other she must smother, as directed,

Or sell the child abroad, ere fully grown.

And this, by barterers, they effected,

Telling them to seek some girl unknown,

And barter boy for girl, in foreign lands,

And if not, return not with empty hands;

Nor should any male child be shown mercy,

If, without him, the race could be sustained.

Such then the law’s sole act of clemency:

To spare one child, that order be maintained,

Yet condemn all the others, equally.

Only in this, some kindness was retained:

Where once all male babes each used to slay,

Now one might live, to prosper day by day.

No matter how many men came to shore,

All were imprisoned, to await their end,

And every day but one of them, no more,

By lot selected, to his death they’d send.

In a shrine Orontea built, before

An altar raised to Vengeance, he was penned,

While one of the chosen ten, did there suffice

To execute the cruel sacrifice.

Canto XX: 36-38: Elbanio arrives, of whom Orontea’s daughter hears praise

Now, to that murderous shore, there came,

After many a year, a youthful knight,

Elbanio was this proud warrior’s name,

Of the line of Hercules, great in might.

There he was seized, not knowing of this same

Vile law, and unsuspecting of his plight.

He was prisoned in a closely-guarded cell,

That gaol claiming other knights as well.

He was handsome, and most pleasant of face,

Noble in his manners, and his dress,

His speech so eloquent, and of such grace,

The ‘deaf’ adder might hark to his address.

So that news of his presence, in that place,

Reached Queen Orontea’s daughter, no less,

As though twere of something rich and rare.

Alexandria was her name; she, sweet and fair.

Orontea was old, while those who, with her,

Had once founded the city, were long gone.

And ten times as many, born then and later,

Filled the plain and wielded power thereon.

Of ten forges that might yield bright armour,

They had need, it seems, for no more than one,

For the ten knights selected took great care

To offer battle to all who ventured there.

Canto XX: 39-46: Alexandria, in love with him, conveys his plea

Alexandria, most eager to behold

This youth who had garnered such great praise,

Asked her mother, Orontea, wise and old,

If she might but view him (and thereon gaze!).

And having heard him, and his tale-retold,

Found her heart bound in unaccustomed ways,

Caught, so it knew not how to break free;

To their prisoner, she had lost her liberty.

Elbanio said: ‘If pity was ever

Witnessed here, and shone as clear and bright

As it does in every other country

On which the wandering sun sheds its light,

Then, I would dare to ask of your beauty,

That must capture every soul, at first sight,

The gift of my life, which I’d dedicate

To serving your wish, both soon and late.

But since hearts, here, lack all humanity,

I will not ask my life of you, in vain,

Since to do so, though deprived of liberty,

Were but to meet with cruelty again;

Yet the knight, good or ill, I seek to be,

Would seek to die, sword in hand, on the plain,

And not, as one condemned, pay the price,

Or some beast, slaughtered as a sacrifice.’

Full of pity for the youthful warrior,

Alexandria, with moist eyes, replied:

‘Though this land may appear far crueller

Than any other place, both far and wide,

Not every woman here is a Medea,

As you seem to believe; if all beside

Were such, then I, alone, you yet would find,

Know how to show true mercy, and be kind.

If I have been, like many here, I own,

Both impious and cruel, I can say

That no object of pity was I shown,

That deserved clemency, in any way;

But fiercer than a tiger, were I grown,

Harder than diamond, were my heart this day,

If that harshness did not melt, completely,

Before your courage, grace, and chivalry.

If less severe were the customs of this land,

Towards the stranger reaching this shore;

Then no less than my life you might demand,

In exchange for your own, whose worth is more.

But none has such power in their command

To aid you freely, for such is the law.

And what you ask, a simple act of grace,

Is yet hard to accomplish in this place.

Yet that I’ll endeavour to achieve,

So that, as a knight, you may die content,

Though it will but prolong, I believe,

Your dying, and harm come of your intent.’

‘So long as I,’ he said, ‘gain that reprieve,

At heart, I feel more than confident

That I shall save myself, and death shall deal

To my foes, though they were made of steel.’

Alexandria, at this, gave no reply,

Her poor heart wounded, beyond remedy,

And departed sadly, with a sigh,

Pierced a thousand times, indeed, and deeply.

Of her mother she begged that he not die

Would he but fight the ten, and willingly,

And, there, reveal himself as of such might,

As to slay them in fair and open fight.

Canto XX: 47-54: The council consent to Orontea’s request

Orontea called the council to gather

And said ‘We must forever seek the best

To guard the shoreline and the harbour,

Though we choose as yet to slay the rest.

And to know who that may be, as ever,

It is fitting that we put some to the test,

So as not, in our choice, to go awry,

And the vile rule while their betters die.

It seems to me, if you agree, that the law

Should say that every knight landing here,

Whom Fortune has abandoned to our shore,

Ere he in the temple dies, like a steer,

May fight alone, and liberty ensure,

If he can slay the ten, with sword and spear.

He afterwards the harbour should defend,

With nine others, selected to that end.

This I suggest, since, in our prison,

We hold one who has offered so to do.

Who if he’d fight thus, ten against the one,

Is worthy of the chance, whate’er ensue.

But if, in boasting rashly, he’s undone,

Then let him bear the punishment still due.’

Orontea made her case, then stood aside,

As the oldest of the others, now, replied:

‘The principal purpose of the law,

And our commerce with men, I understand,

Is not to defend this pleasant shore,

Nor that their strength or aid we need command.

For we have wit and skill enough, I’m sure,

To perform that ourselves, and rule this land;

But that, alone, we lack means to propagate

Our race, and so defy the world and fate.

And since we cannot do without the men,

We allow a few amongst our company,

And yet no more than one for every ten,

Such that they’ll ne’er claim the sovereignty.

For conception are they here, I say again,

And not to defend us and our city.

To use them to that end, be you content,

Vain and idle else is their employment.

To allow one here who’s as strong as ten

Would be contrary to our first design.

If he can fight and conquer all those men,

How many women could he keep in line?

If our ten champions were as strong again

Then our rule they’d have ended, at a sign.

Tis no way to hold power, free and alone,

To arm a hand that’s mightier than your own.

Consider this: if Fortune aids your man,

So that he slays our champions in the fight,

You’ll find a hundred women of our clan,

Deprived of their husbands, day and night.

Let him, to scape, devise some other plan,

Than murdering ten youths for his delight.

Yet pardon him, if he’s the strength of ten,

And can do the deeds they do, as and when!’

Thus, cruel Artemisia’s opinion;

(So, she was named) and had she gained her way,

Elbanio, straight to the shrine had gone,

To placate their vile gods, that very day.

But Orontea, fondly thinking on

Her daughter’s wish and plea, yet had her say,

With argument on argument, until

They were forced to surrender to her will.

Canto XX: 55-57: Elbanio completes the two trials

Elbanio boasted of a beauty

Greater than any other on this earth,

Which so convinced the vast majority

Of the younger women there, of noble birth,

That the judgement of the minority,

Artemisia’s, regarding his worth,

Was set aside, the final decision

Being, to free him on one condition:

That if he slew the ten, as he intended,

He must take ten women to his bed,

(Not a hundred, for that was amended)

And conquer them, once the ten were dead.

So, next day his prison-stay was ended,

And, fully armed, on a fine steed, he sped

To battle with those ten knights in the square,

And, one by one, slew the warriors there.

That night saw his second encounter,

Against ten women, naked and alone.

He wrought so well, owing to his ardour,

That his mastery was swiftly shown.

With Orontea he gained such favour,

That she then adopted him as her own,

And, next, to Alexandria he was wed,

With the other nine he’d overcome in bed.

Canto XX: 58-64: Guidon ends his tale

Orontea left the realm, named after her,

To Alexandria, and Elbanio,

With this clause, that every successor

Should retain the law, of which you know.

Thus, whoever’s stars bring him hither

Whether through pure misadventure, or no,

Must then die, a sacrifice, in the temple,

Or fight alone against the ten in battle.

And if he should conquer the ten, by day,

Then he must sleep with ten women, that night,

And if fate determines that he hold sway,

And he overcomes them all, by first light,

Then as the prince and leader he shall stay,

To command all, and rule the ten outright,

And so, reign, till another knight arrive

That can master all and, thus, survive.

For two thousand years this law they’ve obeyed,

And this wicked custom they maintain still.

And rarely a day goes by ere, conveyed

To their temple, some hapless knight they kill.

If one seeks, like Elbanio, with his blade,

The terms set for his freedom, to fulfil,

He’s often slain in that first encounter;

Not one in a thousand wins the other.

Yet some have achieved the deed, though rarely,

Less, in sum, than the fingers on one hand.

One of these was Argilon; but briefly

Did he rule, as one of ten, all the land,

For, brought by a gale to this fair country,

I slew him, and the rest of his command.

Yet I wish I had died with him that day,

Than live a slave, scorned in every way.

For amorous pleasures, laughter, and play,

In which those of my years oft find delight,

And robes and gems, and then, with fine display,

To hold first place in the land, as of right,

Scant joy of such applies to one, I say,

Deprived of liberty, both day and night.

And never to be free to leave this place

Bound in servitude, seems but deep disgrace.

To know the best years of my life I waste,

The flower of youth, in utter idleness,

The heart within corrupted and debased,

Brings me no pleasure, adds to my distress.

News of my kin every fair land has graced,

Fame bears, on wings, the tale of their success,

Even to the heavens; and I might share

In such if, with my brethren, I fought there.

It seems that, wounded by my destiny,

I’m condemned to a slavery so low

That I am like the war-horse that, sadly,

Is turned out to grass, damaged by a blow,

Or maimed in eye or foot, accidentally,

Or, due to some defect, is treated so.

For, except through death, no escape I spy

From this vile slavery, and so would die!’

Canto XX: 65-69: Astolfo declares himself kin to Guidon

Guidon ended his tale, and cursed the day

With proud disdain, that he had fought the ten,

And then with the ten women had his way,

A double victory o’er maids and men,

And won the realm; Astolfo let him say

His piece, and claim high kinship once again,

Though it seemed as clear as day that Guidon

Was, indeed, his cousin, Amone’s son.

And so, the English duke made this reply:

‘I am Astolfo, your cousin,’ and embraced

The knight, and with courteous, kindly eye,

Not free of tears, their arms now interlaced,

Said: ‘Come, no sign to better signify

Your birth could your mother e’er have placed

About your neck, for that good sword you bear,

And your courage, cry out the blood we share.’

Guidon who, elsewhere, would have felt delight,

At having met with such near kin, dismayed,

And with a mournful face, now clasped the knight,

Knowing that, if that vile law he obeyed,

And he survived, Astolfo, post that fight,

Must die, or death be but a time delayed,

While for the Duke to go free, he must die;

One’s good would spell the other’s ill, thereby.

He grieved that the duke’s companions too,

He would doom, in conquering, to slavery.

While if he died, all means were lost, anew,

His power thus ended, to set them free.

And if Marfisa from one quicksand drew

Her company, and yet, subsequently,

Failed that night, her victory must prove vain,

For they would be enslaved, Marfisa slain.

While, on their side, lay this bitter thought:

That (since the youth’s courtesy and valour,

Upon the hearts, with tender pity, wrought

Of all their company, e’en fierce Marfisa)

If, by his death, their liberty was bought,

They must grieve the fact, in love and honour.

While Marfisa declared if he must die

Then she desired beside him, dead, to lie.

Canto XX: 70-76: Marfisa calls on Guidon to join forces

‘Join with us,’ to Guidon, now, she cried,

‘So, we may issue out in force, as one.’

‘Forsake all hope,’ on his side, he replied,

‘Of leaving; win with me, or be undone.’

‘Fear not,’ she said, ‘I shall not be denied,

I complete my every task, once tis begun;

Nor a safer path can this world afford

Than one where I am guided by my sword.

I have so proved your valour in the square,

I would share any enterprise with you.

When, in the theatre, for this affair

The crowd congregate, then shall we two

Slay the onlookers, once gathered there,

Whether they flee, or stand against the few;

Then leave them to the wolves and crows entire,

Shun their corpses, and set the place afire.’

And Guidon replied: ‘You’ll find me ready,

To follow you, or die there at your side,

Yet let us not seek to live, but simply

Battle on, till vengeance is satisfied.

For oft ten thousand fill the place, wholly,

A female host, while as many are outside

To defend the forts, the walls, the harbour;

No is any way from here unguarded, either.’

Said Marfisa: ‘If of foes there were more,

Than Xerxes had about him in his army,

More than the rebel angels that did pour

From out the heavens, to endless misery,

All, in a day, would die upon this shore,

At least if, scorning them, you were with me.’

‘I know no other scheme,’ Guidon replied,

‘That is of worth, if one plan be not tried,

For it alone would serve, should it succeed,

This that I speak of: I now remember,

Except to women, so it is decreed,

No voyage is allowed, and none may wander

About the sandy shore; yet in our need

I shall seek aid from one loyal ever,

Whose perfect love for me oft have I proved,

In trials not so far from these removed.

No less than me, she loathes this slavery,

And would flee it, if with me she might go,

For she would wish an end to rivalry,

And, thus, she alone might possess me, so.

She’ll obtain a boat, and prepare for sea,

While it is dark, ready, when we may show,

For your sailors to take to the water,

So that we may all depart together.

Behind me, in close formation, then

Merchants, sailors, warriors, all you

Who have chosen (for which my thanks, again,)

To rest beneath my roof, whate’er ensue

You all must forge ahead, if these women

Attempt to block our way; and battle through,

I hope, thus, with the aid of sword and spear,

To lead you from the city, and win clear.’

Canto XX: 77-81: He ensures their means of escape

‘Do as you wish.’ Marfisa spoke again.

‘For I am sure to gain my liberty.

Tis likelier my enemies will be slain

All who, behind these walls, would hinder me,

Than that I take flight, or from fear refrain

To fight, or fail to triumph and win free.

Through force of arms, in daylight, I would go,

My sense of honour would e’er have it so.

If my fame, to these women, was made known,

Their respect I would receive, as I deserve,

Be freely entertained, and have them own

My worth, and in their highest council serve.

But I would seek no privilege, alone,

The like, for my friends, must fate reserve;

While great the wrong if I were to be free,

While those friends were deprived of liberty.

These words, and others she added later,

Revealed that Marfisa withheld her arm,

And refrained from attacking with ardour

That female host, and dealing them great harm,

Solely because she might increase the danger

To her friends, by raising the alarm.

She left it to Guidon to plan, therefore,

The means for their escape he deemed most sure.

Guidon spoke with Aleria that night,

(She, his most loyal wife) nor did it need

Many words from her beloved knight,

She being well disposed, ere she agreed

To prepare and arm a vessel for their flight,

Stowed with the finest goods, as he decreed;

And to feign that, the next day, she would sail

About the bay, since calm weather did prevail.

Swords, shields, spears, had her companions brought

Into the palace, darkness all around,

To arm the sailors, so they could reach the port,

With the company, and there hold their ground;

Some slept, some kept watch lest they be caught,

While seeking, as they watched, to make no sound.

With armour on their back, and weapons drawn,

They waited on the first pale light of dawn.

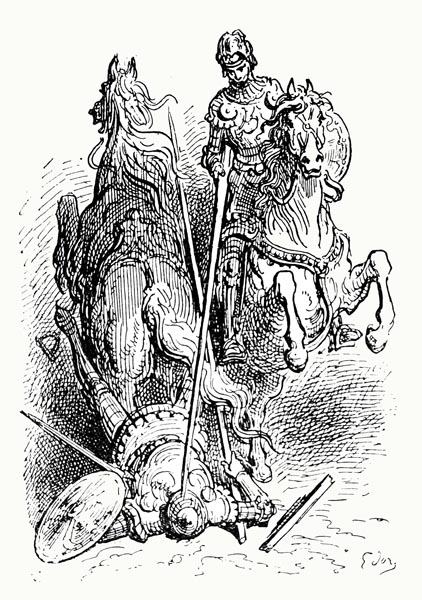

Canto XX: 82-86: The companions fight their way to the gate

The sun had scarcely raised the darkened veil

From the earth’s harshest and most bitter face,

Scarce had the northern ploughman, in the pale

Furrow, turned his ploughshare, to retrace

His steps than the female host, ne’er a male,

Came to the theatre there, and filled the place,

To see the fight; like bees they swarmed the gate,

Changing their realm, in spring, by chance or fate.

To the loud noise of trumpet, horn and drum,

That great crowd made heaven and earth resound,

Demanding their champion Guidon come

To end the fight, begun upon that ground.

Aquilante and Grifone, midst the hum,

Stood fully-armed; there was Astolfo found,

Guidon, Marfisa and Sansonetto,

With all their other knights and men, also.

To reach the harbour and the sea from there,

There was no other passage, long or short,

But to traverse the densely-crowded square,

So, Guidon cried; then, ceasing to exhort

His companions to perform their share,

He issued forth across the central court,

And silently appeared, amidst the throng,

Leading his company, a hundred strong.

Hastening them on, Guidon led his force

Towards the other gate, but all around

The well-armed women now delayed their course,

Using whatever ways and means they found;

Their view, one they did swiftly endorse,

On seeing who led that host o’er the ground,

Being that all would flee, so raised their bows,

And next the gate their own force did dispose.

Guidon and the knights, and, bravest of all,

Marfisa, were not slow to use the blade,

And many a blow from their swords did fall

As they strove to force that gate, unafraid.

But such a storm of arrows did forestall

Their best efforts, with wounds and death repaid,

Pouring down upon their armour from on high,

They feared to meet with harm and scorn thereby.

Canto XX: 87-91: Astolfo sounds the magic horn

Proof against all, the armour that they wore,

That, without it, might have had worse to fear.

But Sansonetto’s horse fell, and that which bore

Marfisa, while, Astolfo, drawing clear,

Said to himself: ‘Why wait a moment more?

The horn I must needs use, it would appear.

If I can gain naught further with the sword,

Then let the horn a passage forth afford.’

Then, as he was wont, in extremity,

That magic trumpet to his lips he placed,

And, as the dreadful sound rose, forcefully,

And earth and sky both trembled, on they raced.

It brought about such fear in the enemy

That, seeking to escape, in sudden haste,

As from the square they fled deafened quite,

They left the gate unguarded in their flight.

Like to some family, fleeing danger

Who leap from the windows, up on high,

Chancing life and limb, as near and nearer

The fire approaches, and flames fill the sky,

Which had crept upon them in their slumber,

Their eyes closed to all, where they did lie,

So, reckless of their lives, the women fled,

The horn’s loud cry filling them with dread.

Above, below, scattering here and there,

Their foes sought to flee, and at each gate

A thousand milled about upon the square,

Falling there, so thwarting each other’s fate,

Or leapt from the galleries, through the air,

To lose their lives, fearing to contemplate

Worse ills, many a head and arm broken;

Here one crippled, there a corpse forsaken.

Great cries and sore lament rose to the sky,

Mingling with the noise, amidst the rout.

Where’er the sound of the horn passed by,

Dreading its noise, they scattered all about.

If tis said but little caused such to fly,

Lacking courage, filled with fear and doubt,

Tis no wonder, for the hare, by nature,

Is likewise a timid, fearful creature.

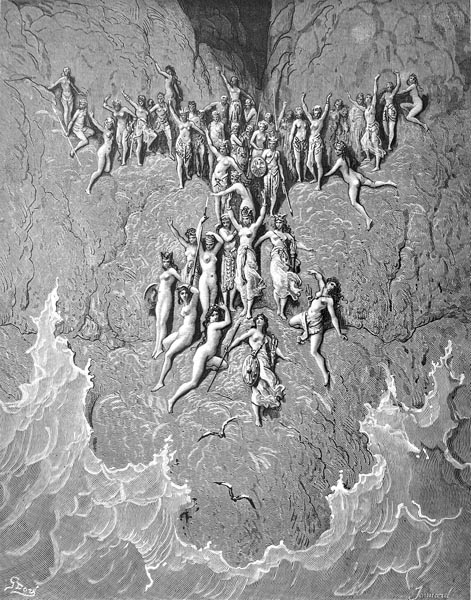

Canto XX: 92-98: All but he set sail

But what of those two brave hearts, Marfisa

And (their leader) Guidon Selvaggio?

Or that pair, whose lineage showed ever

Great deeds (those sons of Oliviero),

Who’d held a thousand as naught earlier,

Yet fled now, robbed of courage, even so,

As rabbits run, or fearful doves will fly,

That hear some echo from the earth, or sky?

Quite as dreadful to friend as to stranger,

Was the power of that enchanted horn.

Guidon, Sansonetto, and Marfisa,

With the brothers, in fear, to flight were sworn.

Nor could they reach such a distance either,

That the clamour was not towards them borne.

For Astolfo, galloping far and wide,

Blew the horn ever louder, on his ride.

Some sought the sea, some the mountain high,

And some chose to hide, deep within the trees;

While one who never turned her head, did fly

For a good ten days at least, without cease.

Some sought to leap down from the bridge nearby,

Never to rise again, e’en to their knees.

The temples, houses, squares, now, silence claimed,

And free of human presence they remained.

Marfisa, Guidon, and Sansonetto,

All pale and trembling, fled towards the sea,

With the brothers, and mariners, also,

Where, between the two strong forts, they could see,

Aleria’s barque, to which they now did row,

For she’d left the boats there, riding easily,

And, once they’d reached the vessel, did avail

Themselves of the breeze, and soon set sail.

Astolfo had scoured the whole city,

From the hills to the shore, within, without,

Leaving the streets echoing and empty,

All having fled before him, midst the rout;

Many, whom cowardice led completely,

Hid, in some dark and filthy place no doubt,

While many not knowing how they might flee,

Took to the waves, and drowned, there, in the sea.

The English duke now sought the company,

Whom he had hoped to find upon the shore.

He turned his gaze upon the sand, yet he

Found them not; as he raised his eyes once more,

There, in the distance, sailing, silently,

Over the open sea, their ship he saw.

And so was forced to seek another way

Of escape, they having gone from the bay.

Let him depart; feel no regret that he

Must travel, now, a long and lonely road,

Through a barbarous and pagan country,

Where suspicion haunts each least abode,

There is no danger, once the enemy

Hear that magic horn, as he lately showed.

But let his five companions be our care

Who’d fled in fear, and o’er the waves now fare.

Canto XX: 99-101: The company, minus Astolfo, make their way to Marseilles

Far out to sea, the vessel now did stand,

Scorning that most cruel and bloody shore,

And having reached a distance from the land

Where they could hear the dreadful horn no more,

Unaccustomed shame set its fiery brand

Against their faces, till its flames they bore;

None dared to eye another, in a daze,

They stood, unspeaking, sad, with lowered gaze.

Intent upon his course, their captain passed

Cyprus and Rhodes, then, o’er the Aegean,

A hundred islands fell behind their mast.

Next by Malea’s fierce cape, in their run

Before the wind’s fair, and constant blast,

They sped, and Greek Morea, neath the sun;

Round Sicily, o’er the Tyrrhenian Sea,

Reaching the pleasant shores of Italy.

Luni, on Genoa’s coast, now rose to view,

Where the master had left his family.

He thanked God, to whom fulsome thanks were due,

That they’d received no damage from the sea.

The knights sought to journey now, anew,

France was their object, all that company.

They embarked, and blown swiftly on their way,

In a brief while, found themselves at Marseilles.

Canto XX: 102-105: Marfisa quits the other four

Bradamante, who had sole governance

Of that region was absent at that hour,

Who if she then had been in residence,

Would have used every means in her power

To persuade the group to grace her presence;

But Marfisa, staying but a brief half-hour,

Took leave of the three and Aleria,

And took her wandering way, at a venture,

Saying that she thought it unbecoming

For so many knights to travel together,

So, doves, or starlings, journey on the wing,

And deer, and such, in a herd will gather;

Yet the falcon, and the eagle, soaring,

Place no reliance on any other,

While lion, bear, and tiger roam, alone,

Fearing no greater strength than is their own.

None of the rest were of similar mind,

And so, she took her solitary way;

Through the forest, lonely tracks she did find,

As, without companions, she did stray.

Guidon (with Aleria his wife behind),

Aquilante and Grifone, left that day,

And a castle, from the broad road, did see,

Wherein they were lodged, most courteously.

Courteously, so it seemed outwardly,

Though soon the contrary would be revealed,

For the castellan feigning courtesy

And benevolence, their opposites concealed;

And, as they slept, seemingly securely,

In their beds, laying by both sword and shield,

He took them, and refused to let them go,

For a custom, most vile, they must follow.

Canto XX: 106-110: And comes upon an aged crone, and then Pinabel

Yet, I shall pursue the warrior-maid,

Before I speak again of those four.

Beyond the Durance, Rhône, and Saône she strayed,

Where neath a mountain, on the valley-floor,

Beside a torrent, all in black arrayed,

She met an aged crone, one wearied sore,

Twould seem, from some long tiring journey,

Though afflicted more with melancholy.

She was the aged crone who once had served

The band of robbers in their mountain cave,

To which, to mete the justice they deserved,

Orlando came, Anglante’s count, full brave.

The crone, fearing death, though yet preserved,

Had, for a reason I must briefly waive,

Fled swiftly through the forest, dark and deep,

Lest any should remembrance of her keep.

Viewing the semblance of a foreign knight

In Marfisa, her surcoat and armour,

She chose not to flee, as before, on sight,

She had fled from every native other,

But feeling more secure, she ceased her flight,

At the ford and, once there, waited on her;

At the ford through the torrent, and then she

Advanced to greet Marfisa, pleasantly.

Then she asked the warrior-maid to bear her

On her horse’s croup to the other shore,

And, being of noble stock, Marfisa,

Lifted her up, and so carried her o’er;

And did not disdain to bear her further,

Till the path beneath them was more secure,

Clear of weed and stone; once there, they found

A horseman who towards the ford was bound.

This knight bestrode a saddle rich and fair,

His weapons gleaming, ornate his armour,

A squire, and a lady, the road did share,

As they descended towards the river.

The lady was lovely, yet her proud air

Was scarcely pleasing, to the onlooker,

So full of pride, and insolence, indeed,

Twas worthy of the knight who led her steed.

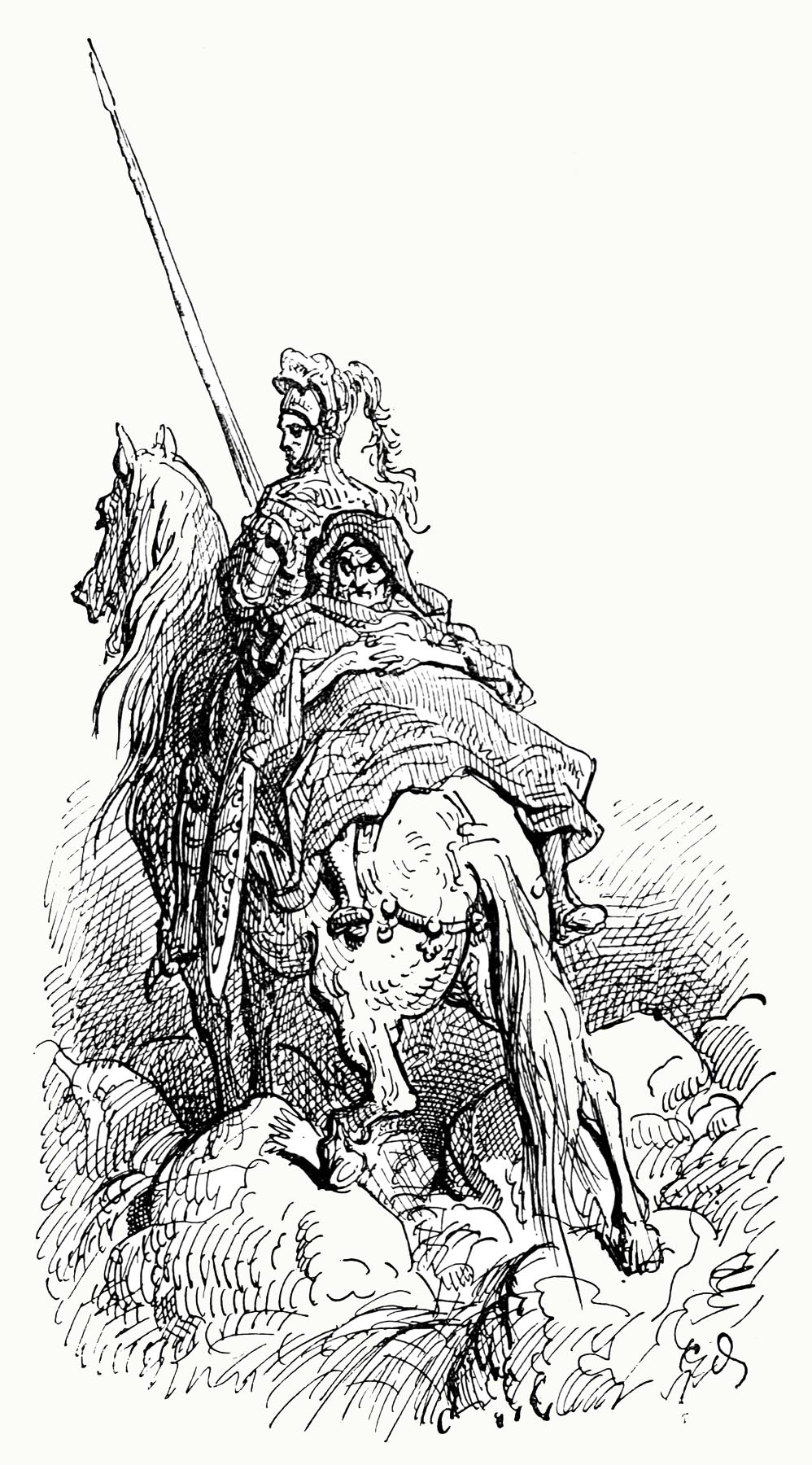

Canto XX: 111-116: Marfisa disposes of the knight

Pinabel, of the House of Maganza,

Was the knight accompanying the lady;

The same who Bradamante, earlier,

Had plunged into the cavern, spitefully.

Those sighs, those tears burning ever hotter,

That had near blinded the fellow, surely,

Were for the lady he now led towards her,

Once imprisoned by the necromancer.

Yet, when the enchanted tower was razed

From the mount, the keep of old Atlante,

And his prisoners, once free, all amazed,

Then roamed at will, thanks to Bradamante,

The lady who before had always praised

And obeyed this Pinabel entirely,

Once more at his side, had journeyed so,

As from castle to castle, they did go.

Now, being so inclined, when she saw,

Marfisa’s companion on the road,

Her laughter could contain itself no more,

Mocking the crone, as with delight she crowed,

Proud Marfisa, who ne’er an insult bore,

Unused to hearing such, swift anger showed,

And, scornfully, replied to the lady,

That the crone was far lovelier than she;

And this she would prove upon the knight,

And more she would strip her of her gown,

And seize her good palfrey, when, in the fight,

She had brought her fine friend tumbling down.

Pinabel, who could scarce accept the slight,

A source of shame, a blight on his renown,

Raised his shield, lowered his lance, and spurred his steed,

And rode towards her angrily, at speed,

Marfisa grasped her heavy lance, and thrust,

As she encountered him, at Pinabel’s face,

And stretched him, dumbfounded, in the dust,

Nor could he raise his head an hour’s space.

Marfisa, conqueror o’er the unjust,

Told the maid to strip her gown off, apace,

With all the gems and ornaments she wore;

And these to the old crone as gifts she bore,

Requesting her to don that youthful gear,

Both the dress and ornaments of the maid.

And then the palfrey she did commandeer,

On which the maid had ridden; so arrayed,

The crone now high on horseback did appear,

The better dressed, the worse the sight she made.

Three days they rode, without encountering

A single thing at all worth the telling.

Canto XX: 117-120: They encounter Zerbino who insults the crone

On the fourth day they met a knight who sped,

In wild gallop, all alone, down the road.

If you would have me name the knight ahead,

Twas Prince Zerbino who that steed did goad,

That exemplar, of worth and beauty bred,

Who, in grief and anger, bore a heavy load,

Lacking the means to take vengeance, swiftly,

On him who’d thwarted his great courtesy.

He’d pursued the man through the wood in vain,

Ever behind the one who’d done him wrong,

While the other had managed to maintain

The greater speed, as they had coursed along,

Through tangled undergrowth, and then again,

Amidst the wood, the dawn light lost among

The misted trees, and scaped his sword, to hide,

Till his anger and fury might have died.

Yet Zerbino, despite his blazing anger,

On seeing the crone, could not but raise a smile,

Her youthful dress was a source of laughter,

When contrasted with her face, old and vile.

Then he said: ‘’You are wise sir,’ to Marfisa,

(After gazing at the crone for a while)

‘To go leading so peculiar a lady,

That you needs must fear no other’s envy.’

The crone possessed (as indeed one might guess

From her wrinkles) more years than the Sibyl,

And in all her ornaments, and in that dress,

Seemed an ape, adorned, to be risible,

And far viler since angered to excess,

Her old eyes glittering now, and terrible,

For no man can insult a woman more,

Than to claim she is old, and an eyesore.

Canto XX: 121-127: Marfisa unseats him

She showed her disapproval, our warrior,

At his taking pleasure in it, as he had,

And called to Zerbino: ‘She is fairer

By far than you are courteous, my lad.

Though I think the words you chose to utter

Came not from the heart indeed, and tis sad

That you feign not to own to her beauty,

To avoid being seen as cowardly.

For what knight is there who would not wish,

On finding such a young and lovely maid,

With no more company at her side than this,

To take her for his own, in this fair glade?’

‘She suits you so well,’ he said, with relish,

‘Twere ill if from your side she were conveyed.

And I would never prove so bold, sir knight,

As to deprive you of your fond delight.

Yet if you would, indeed, have more of me,

I would be glad my skill to demonstrate,

Though deem me not of such perversity

That I ask no more than with such to mate.

Fair or foul, may she share your company;

I would not seek to mar a love so great.

Well matched the pair of you; and I do swear

You are as valiant as she is fair.’

‘Despite all you say,’ replied Marfisa,

‘You shall not seize the lovely maid from me;

One so beautiful I shall not suffer

You to gaze on, nor gain her easily.’

Said the prince: ‘I know not why a warrior

Should undertake to win a victory,

And place himself in peril, for his pains,

When, if he succeeds, the loser gains!’

‘Well, if that course seems less than good to you,

I’ll suggest another, out of chivalry;’

Cried Marfisa, ‘if your aim’s good and true,

And you win, she shall yet remain with me.

But if I succeed, she will be your due.

Let us see, now, whose prize she shall be.

If you lose, you shall escort her ever,

Where’er she’s pleased to go, and whenever.’

‘So be it!’ cried Zerbino, in reply,

And wheeled his steed about, suddenly,

Gathered himself, and raised himself on high,

Firm in the saddle, then struck her neatly,

In mid-shield, thinking she must fall, thereby;

As if made of steel, she swayed but slightly,

And then thrust at his helmet so surely,

He fell from the saddle, dazed completely.

Much grief it gave Zerbino thus to fall,

To whom the like had ne’er occurred before;

Thousand upon thousand, after all,

He had vanquished, and left upon the floor.

For a long while he lay, twas bitter gall,

And thinking on it, it pained him the more

That he had promised, and it must be so,

To accompany the crone where’er she’d go.

Canto XX: 128-134: She departs; the crone deduces that he is Zerbino

Turning to him in triumph, and smiling,

Marfisa cried: ‘This lady I present

To you; the more beauty there residing,

She being yours, the more I am content.

Take you the place I am forsaking,

And yet of your firm promise ne’er repent;

Fail not to lead and guide her on the way,

(As you have sworn) wherever she would stray.’

And then, without waiting for an answer,

She spurred her steed, and vanished midst the trees.

Zerbino, who would know the warrior

That had defeated him, and with such ease,

Asked the crone, and she, to fuel his anger,

Was happy to provoke the knight, and tease:

‘Why, the blow came from the hand of a maid,

That on the ground your noble self has laid.

Her valour sees her overcome each knight

She meets; she is the pride of sword and lance,

And from the East she comes now to men’s sight,

To test the mighty paladins of France.’

Not only did Zerbino blush outright,

With the shame of his most grievous mischance,

But little was wanting to crimson o’er

Every piece of armour that he wore.

He re-mounted, blaming himself, indeed,

For his inability to keep the saddle,

While the crone smiled within, and sought to breed

More ire in him, and increase his trouble.

She reminded him of her pressing need

For a guide, and Zerbino, ever noble,

Stood like a weary steed that, ears drooping,

Feels the bit in its mouth, the spurs pricking.

And, sighing, he said: ‘O fickle Fortune,

What alteration you e’er bring, night and day!

The fairest one, beneath the sun and moon,

That should be mine, you rudely snatched away.

And think you now to sound another tune,

And with this gift of yours the debt repay?

To lose all I own, would seem less strange,

Than suffering so unequal an exchange.

She, that for her virtues, and her beauty,

Was never equalled, nor shall ever be,

You drowned among the reefs, most cruelly,

Food for the birds, or creatures of the sea.

And she that should have fed the worms, why she

You preserve beyond her time, fatally,

Granting this crone ten years, fifteen, a score

She should not own, but to torment me more.’

So said Zerbino and in these words displayed

No less grief, nor less sorrow in his face,

For the vile acquisition he had made,

Than for the loss of his lady, full of grace.

The aged crone, though she had never laid

Eyes on him before, yet deduced, apace,

From his speech, that he must be the lover

Of Galicia’s fair Isabella.

Canto XX: 135-138: She has news of his beloved Isabella

For, if you recall all that you have heard,

This crone had escaped the robbers’ hold,

Where Isabella, who his heart had stirred,

Was kept a prisoner, to be bought and sold.

And she’d oft described, with many a word,

How, o’er the waves, she’d left her native fold,

And how her ship had been wrecked, as well,

Upon the reefs that border La Rochelle.

And she had so portrayed her Zerbino,

His handsome features, and his noble face,

That the crone, on hearing him, and also

Drawing nearer to view his form and grace,

Realised this was the youth, he who had so

Grieved the heart of Isabella, in that place,

Who had wept more at losing him, she knew,

Than at falling captive to that vile crew.

The old woman, hearing all the pain and woe

The prince poured forth, realised that he

Wrongly believed (and hence his deep sorrow),

That Isabella had drowned in the sea.

Yet, though the true position she did know,

To plague him, out of sheer perversity,

She hid what would have granted him relief,

And only told him what would cause him grief.

‘Hear me,’ she said, ‘you who are so haughty,

You who mock me, and treat me with such scorn,

Since you’d wish to hear the news, eagerly,

That I possess regarding her you mourn:

Well, I would rather be strangled, slowly,

Or, to a thousand pieces, ripped and torn;

While if you had been kinder, and less cold,

All that is hidden from you, I’d have told.’

Canto XX: 139-144: But withholds her whereabouts

As the mastiff, that attacks a robber,

Is soon pacified, with a crust or bone,

As promptly, now, did Zerbino offer

His apologies to the triumphant crone,

Humbling himself, prepared to suffer,

If only something further might be known.

For in that wrinkled face of hers he’d read

That she had news of one whom he’d thought dead.

And turning to her, with a kinder face,

He supplicated, begged, and conjured her,

By all the gods, and men, though he must face

Ill news not good, the whole truth to utter.

Replied the stubborn crone, devoid of grace:

‘Naught shall you hear but will make you suffer;

She did not die, in spite of all you’ve said,

Yet her life is such, she envies the dead.

She, fell (so swift it was that you heard naught),

Captive, to a band of twenty or more,

Such that if she now, to you, was brought,

Think not to cull the flower you longed for.’

Ah, cursed hag, how cruelly you wrought

Those lies, for false indeed the tale you bore:

Though, in the hands of twenty, a prisoner,

Not a single one had sought to touch her.

Though he asked to know where she had seen her

And when, yet poor Zerbino asked in vain,

For the obstinate crone, despite his prayer,

Would add naught, nor would she further explain.

The prince gentle pleas, at first, did utter,

Then swore he’d cut her throat, in his pain,

But prayers and threats likewise went unheard,

For he failed to make the monster speak a word.

At length Zerbino’s tongue came to rest,

Since his speeches had brought him little joy;

He could scarce feel the heart beat in his chest,

Such jealousy with that poor heart did toy.

To search for his lady, was now his quest,

Any and every means he would employ,

E’en to leap into the flames, yet ever

Was bound by the oath he’d sworn Marfisa.

So, from thence, by strange and solitary ways,

As the old crone chose, Zerbino was led,

O’er hill and dale, each averting their gaze,

And in silence, for not a word was said.

But the peace was broken, when the sun’s rays

Declined from noon, by a bold knight who sped

Towards them, on the road, and you shall know

What happened, in the canto to follow.

The End of Canto XX of ‘Orlando Furioso’