Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XVII: Norandino and the Ogre

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XVII: 1-5: The curse of tyranny

- Canto XVII: 6-13: Rodomonte reaches Charlemagne’s palace

- Canto XVII: 14-16: Charlemagne and his knights attack Rodomonte

- Canto XVII: 17-21: We return to Grifone and Orrigille, in Damascus

- Canto XVII: 22-25: Grifone learns the reason for the tournament

- Canto XVII: 26-28: King Norandino’s ship is caught in a gale

- Canto XVII: 29-35: The rest of the company are captured by the Ogre

- Canto XVII: 36-39: Norandino reaches the Ogre’s cave

- Canto XVII: 40-44: The Ogre’s wife confirms that Lucina is alive

- Canto XVII: 45-49: She plans a way for the king to join Lucina

- Canto XVII: 50-57: He then helps the others to escape

- Canto XVII: 58-63: But, with Lucina still captive, is forced to linger

- Canto XVII: 64-68: Lucina having been rescued, Norandino searches for her

- Canto XVII: 69-72: Grifone prepares for the tourney at Damascus

- Canto XVII: 73-80: Ariosto exhorts the West to reclaim the Holy Land

- Canto XVII: 81-84: The prize assigned to the tournament

- Canto XVII: 85-90: Martano, Orrigille’s lover, is defeated in the joust

- Canto XVII: 91-99: Grifone overcomes seven of the eight knights

- Canto XVII: 100-105: And lastly Seleucia’s lord

- Canto XVII: 106-108: The trio leave Damascus and halt at an inn

- Canto XVII: 109-114: Martano, in disguise, is honoured as Grifone

- Canto XVII: 115-118: Grifone repents of his foolishness

- Canto XVII: 119-125: He is mistaken for Martano

- Canto XVII: 126-128: Norandino devises his punishment

- Canto XVII: 129-130: Martano and Orrigille depart

- Canto XVII: 131-135: Grifone frees himself from his captors

Canto XVII: 1-5: The curse of tyranny

The Lord of Justice when iniquity

Runs beyond the bounds of absolution,

Shows a justice equal to His pity,

To crown the tyrant is His solution,

Some monstrous expert in atrocity,

And grants him powers of execution.

He gave, to Rome, Marius and Sulla,

Two Neros, and the mad Caligula,

Domitian, the last Antonine, Commodus,

And, promoted from a common soldier

To imperial power, Maximinus.

Thus, to Creon, a Thebes must surrender,

An Agylla to Virgil’s Mezentius,

He that drenched the fields with blood, not water;

And in Italy, in times near to our own,

Fierce Lombards, Huns, and Goths have held a throne.

And what of Attila? What of the impious

Ezzelino of Romana, and hundreds more?

Twas because of all their iniquitous

Deeds, God sent deep woe, and torment, and war.

And we have clear proof from those among us,

Not merely from the ancients, of His law,

When we, His worthless and ill-nurtured sheep,

He gives to some rapacious wolf to keep,

A beast, that having sated its own hunger,

And lacking the stomach to consume more,

Summons up some ultramontane other

From distant woods, greedier than before.

The bones of Trasimene, and Trebbia,

And Cannae, were yet sparse along the shore,

Compared to those that field and bank display

Where Adda, Mella, Ronco, Tara, stray.

Now, the Lord consents to our punishment

By those who, perchance, are worse than us,

For our sins, which are foul and pestilent,

And our desires, base and iniquitous.

Yet the time will come when our troops are sent

To despoil their lands, if more virtuous

We prove ourselves, their vile sins such again

As e’en Eternal Goodness must disdain.

Canto XVII: 6-13: Rodomonte reaches Charlemagne’s palace

What excesses they must have committed,

This folk, to have troubled God’s brow so;

For He the Turks and Moors had permitted

To rape, and kill, and plunder here below.

But worse than all to which they’d submitted,

Was Rodomonte’s fury, bringing woe.

And so it was, I say, that Charlemagne.

Came seeking for him, in that place of pain.

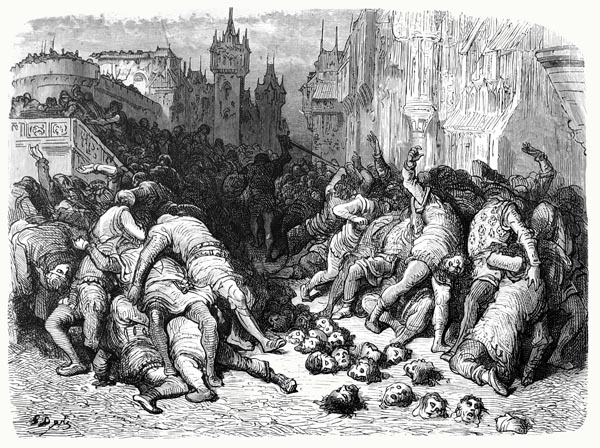

He saw the corpses littering the street,

The burning palaces, and ruined shrines,

A great part of the city razed complete,

Nor had he ever seen such fateful signs.

‘Where will you flee to?’ thus the king did greet

That crowd, ‘Where is the coward that resigns

Himself to such a loss? What fresh city,

What place is yours, if you act shamefully?

Shall one man alone, constrained within,

Surrounded by walls he cannot conquer,

Go unchallenged, and thus his freedom win,

When all those around you die and suffer?’

Thus, Charlemagne now railed, and called it sin,

So intense the shame he felt; and, after,

To the open square, he then made his way

Where, before the palace, heaped corpses lay.

There, had fled many of the populace,

Hoping that they might find aid and shelter,

For well-fortified was that entire place,

With munitions for the brave defender.

Rodomonte, with proud and angry face,

Cleared the courtyard, scornful, as ever,

Of all the world, whirling his sword higher,

With one hand, with the other hurling fire.

He hammered on the gates, wide and tall,

Of the royal palace, as, from above,

The defenders let stones and timbers fall,

For whole sections they’d contrived to remove,

Hurling down the roofs of tower and hall;

Great fragments of them they sought to move,

Huge slabs, great columns, gilded beams, and more,

Prized by their grandsires, centuries before.

Rodomonte stood, gleaming in the light,

Clad all in steel, before the portal there,

Like a serpent issuing, shining bright,

Having sloughed its skin, to the outer air,

Proud of its scaly hide, and filled with spite,

Renewed in vigour, rising from its lair,

Forked tongue flickering, and eyes of fire,

All creatures yielding to its least desire.

Not stone or beam, not arbalest or bow,

Nor whatever else was aimed at the Moor,

Could arrest the hand of their mighty foe.

He struck, and cleft, and broke apart the door,

And made a vast opening, that did show

The courts full of people, and every floor

Filled with faces gazing, pale as death,

Scarce daring now to take a single breath.

But then there echoed from the vaults, on high,

Wails of woe, as the women sought to flee,

Striking their breasts and, with many a cry,

Seeking their chambers, in their misery,

Grasping the doorpost, or the bed nearby,

Some vile stranger would fill, seemingly;

Such was their state, menaced and sore afeared,

When Charlemagne, and his court, appeared.

Canto XVII: 14-16: Charlemagne and his knights attack Rodomonte

The king turned to his mighty company,

Whom he’d e’er found loyal in time of need,

‘Are you not those that, in Aspramonte,

Stood against Agolante, wrought the deed,

And slew Troyano, and bold Almonte,

And hundreds more? Do you, now, fear to bleed?’

He cried, ‘When this vile foe we seek to face

Is but one more of that accursed race?

Shall I behold less strength and skill in you

Than seems to live in that bold enemy?

Come, let your greater prowess be on view;

End this mere man, and his foul killing spree.

A valiant heart cares not when death ensue;

If the man dies well, therein lies victory.

Yet I doubt not; stronger are you by far,

For I have ever conquered where you are.’

With this, he spurred his mount, his lance held low,

And galloped straight towards the Saracen,

Beside him rode Namo, Ugiero,

And Ulivier; came Avolio, then,

Otone, Berlingiero, Avino,

(Ever seen together, bravest of men)

Who charged at Rodomonte, allied,

In striking at his helmet, breast, or side.

Canto XVII: 17-21: We return to Grifone and Orrigille, in Damascus

But let us leave this talk of war, and ire;

Pray accept that I’ve said enough, for now,

Of that Saracen, bringing sword and fire,

As strong as he was cruel, you will allow.

It’s time to seek Damascus, and enquire

Of Grifone, who rides with furrowed brow,

Beside Orrigille, and a brother

That is no kin of hers, but her lover.

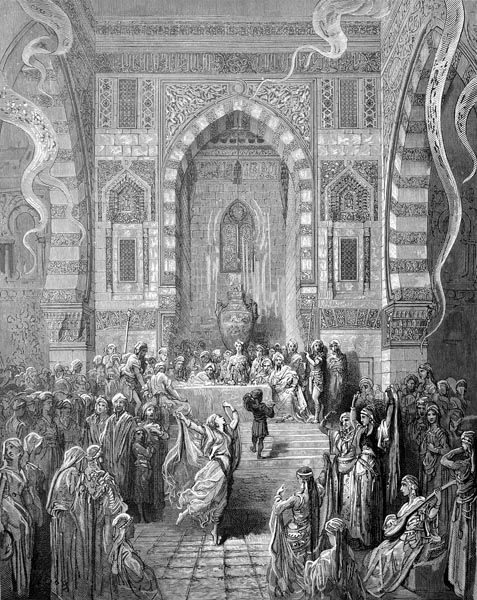

Among the wealthy lands of the Levant,

The most populous, and the most ornate,

Is said to be Damascus; not distant

Seven days from Jerusalem’s north gate.

Rich and fertile is the plain; abundant

Its crops, summer and winter, soon and late.

In that place, the dawn rays, shining bright,

Fill the hills, to the north-west, with their light.

Through the city, two crystal rivers flow,

That, dividing variously, water

An endless series of gardens, as they go,

That are never bare of leaf, or of flower;

And, their streams drive many a mill, also,

Possessing both the depth and the power,

Tis said; and that those who choose to wander

Its streets meet many a perfumed odour.

On that day, the main street was covered o’er

With bright cloths, of many a differing hue;

While fragrant herbs, and fresh green leaves, and more,

Graced the open ground, and decked the walls too.

Every window was adorned, and every door,

With drapes and carpets, various and new,

But more so with fair ladies, richly dressed,

With costly jewels, and fine garments, blessed.

Within the gates, the people celebrated,

In the crowded squares, in joyful dance,

While in the streets, some demonstrated

Their greater rank, and set their steeds to prance;

And then their power the courtiers illustrated,

Knights, barons, vassals, with their slow advance,

And the showers of pearls, and gems, they wore,

From India, and Eritrea’s shore.

Canto XVII: 22-25: Grifone learns the reason for the tournament

Grifone rode in, with his company,

Calmly gazing as he went, here and there;

When a knight stopped them, courteously,

And asked them to his palace in the square,

Where he wished them to stay, presently;

That they suffered no hardship, was his care.

He had them bathe, and then, cheerfully,

Led them to a sumptuous meal, those three.

He told them, then, how King Norandino,

King of Damascus, and all Syria,

Had invited every sworn knight, to go

Whether a native, or a foreigner,

To a great tournament, on the morrow,

Which would be held in the square, as ever;

Where, without straying further, one might show

Whether one’s valour matched one’s pride, or no.

Though that was not his purpose in coming,

Grifone agreed to participate,

For, when the occasion comes, tis pleasing

To display one’s true worth, and demonstrate

One’s martial skills; then asked him why the king

Gave the feast, and whether it was, of late,

A regular event, or something new,

By means of which his knights he might review.

‘At every fourth moon,’ came the reply,

‘The king must offer a like tournament.

This is the first of them, for none, say I,

Have been held formerly, and his intent

Is to commemorate the day, drawn nigh,

On which his life was saved, though all but spent,

After four months of pain and woe, likewise

The constant threat of death before his eyes.

Canto XVII: 26-28: King Norandino’s ship is caught in a gale

Norandino (to explain more fully),

Our monarch, had felt for many a year

A burning desire for the quite lovely

Daughter of the King of Cyprus; more dear

To him than any maid, and finally,

Sought her in marriage, then to bring her here,

With knights and ladies of her company,

To his Syrian realm, from o’er the sea.

But as we ran, with our mainsail outspread,

Through Carpathian waters, far from shore,

A storm arose, so cruel that it brought fear

Even to our old captain; down it bore

Upon the ship, took us, and drove us clear

From our course, threatening, evermore;

Yet left us, at the last, wet and weary,

In a bay with fresh streams, green and hilly.

We set up our pavilions, midst the trees,

Hung awnings there, and were more than happy;

Set a fire, and built a canteen, with ease,

And spread carpets for a banquet, swiftly;

Meanwhile, Norandino roamed, without cease,

The untrodden woods around, every valley,

Seeking goats, or deer: fallow, red, or roe;

And followed by two servants with his bow.

Canto XVII: 29-35: The rest of the company are captured by the Ogre

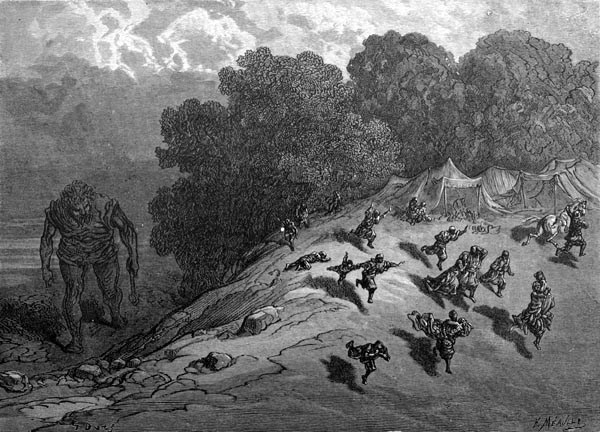

While we sat there, pleasantly, awaiting

The return of our monarch from the chase,

We saw a monstrous Ogre approaching,

Racing along the shore, towards that place.

God grant you never meet the wretched thing,

Nor that your eyes behold his dreadful face.

Better to hear that such exists, than see

It drawing near you, in reality.

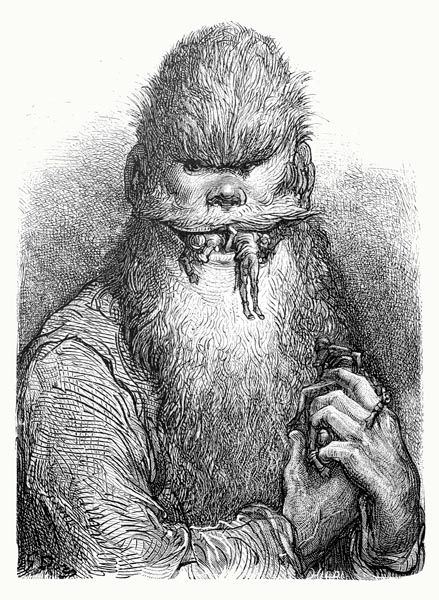

Twas hard to calculate the creature’s height,

So immense was he; he had, instead of eyes,

Two fungus-coloured berries, lacking sight,

Orbs of bone, neath the brow, of little size.

He came towards us, as I said, and might

Have been a hill decked out in mortal guise.

From his face two tusks, like a savage boar,

Projected, and a long snout, dripping gore.

He came running, scenting in the manner

Of a hound, when it’s hot upon the trail.

We beheld him, and then fled, wherever

Fear drove us, with faces drawn and pale,

His blindness no comfort; he knew better

By sniffing at the ground, thus, all the tale

Of things about him than do those with sight;

Swift wings were needed to pursue our flight.

We scattered here and there, but all in vain;

He travelled faster than a sudden gale.

Of forty, scarce ten did our ship attain

By swimming, and were tempted to set sail.

He tucked some beneath his arm, and was fain

To clasp the rest to his chest, and avail

Himself of the immense pouch that was tied,

Like a shepherd’s spacious purse, to his side.

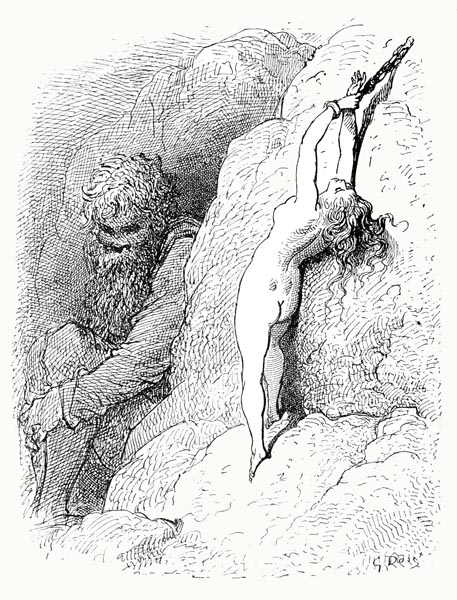

The blind monster bore us off to his lair,

Carved deep into the cliff, above the shore,

Of marble were its walls, as white and bare

As a blank sheet of paper, fresh and raw.

A monstrous wife of sorts dwelt with him there;

Marks of pain and grief on her face she bore.

And women and maids too dwelt in that place,

Both fair and foul, of every age and race.

And close to this cave there was another,

Just beneath the summit of the rock,

No smaller in size, that, from the weather,

Served to hide, and defend his precious flock;

He would graze those sheep winter and summer,

Their number such that none could count his stock.

As he wished he’d pen them, or set them loose,

More to yield him pleasure than for use.

But, to mutton, he preferred human flesh,

And was seen, ere he had reached this enclave,

To eat three of our number, being fresh;

For the young and tender, such he did crave.

He moved a stone that had sealed the creche,

Drove forth his flock, and left us in that cave.

With that, he took his customary way,

While a flute, hung at his neck, he did play.

Canto XVII: 36-39: Norandino reaches the Ogre’s cave

Our king, meanwhile, returning to the shore,

Became aware of the loss he’d sustained,

For silence reigned and, everywhere, he saw,

Mere empty tents and canopies remained.

Nor did he know who should answer for

The theft, if such it was; fearful and pained,

He ran to the strand, and saw his men take

To a boat, that for the wide beach did make.

For as soon as their monarch came in view,

They launched the pinnace, and now plied the oar,

But no sooner did he hear, from its crew,

Of the Ogre, that he turned from the shore;

Indeed, his only thought was to pursue,

The creature till it reached its stony door.

So painful was the loss of his Lucina,

He was doomed to die, unless he found her.

On observing fresh footprints in the sand,

He tracked them, with a lover’s fervour,

Swiftly, glancing about, on every hand,

Till the Ogre’s cave he did discover;

Where imprisoned nearby, our fearful band

Awaited his return. Who worse could suffer?

At every sound we heard, we were afraid

That of our flesh his dinner would be made.

Fortune guided the monarch to the cave,

While the Ogre’s wife was there, and not he.

Seeing the king: “Flee!’ she cried, ‘and save

Your life! Woe will be yours, if he should see

A sign of you.” “Seen or not seen,” the brave

King replied, “saved or not, my misery

Is such that led by love, not chance, am I,

That seek beside my honoured wife to die.”

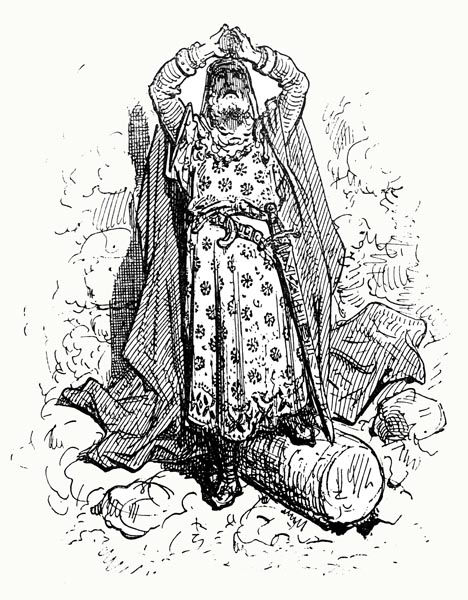

Canto XVII: 40-44: The Ogre’s wife confirms that Lucina is alive

And then he pressed the Ogre’s wife to say

What became of those he made prisoner;

And whether his Lucina lived that day,

And, if so, where the Ogre might hold her;

She then answered him, in a kindly way,

And eased his mind, telling him his lover

Was alive, nor her death need any dread,

For on woman’s flesh the Ogre ne’er fed.

“Of this,” she said, “I am the living proof,

And all the women who dwell here with me,

From me, and them, the Ogre keeps aloof,

So long as we remain here, for, you see,

Any that would forsake this stony roof,

Will never be at peace, or pardoned be.

Buried alive are they, chained on the strand,

Or naked, in the sun, he’ll make them stand.

When he brought your people here, today,

The men from the women were not parted;

Whate’er they be, he shut them all away.

Off to that pen of his they were carted.

Yet he will sort them out, by sex, I say,

With that nose of his; be not downhearted;

The men alone he eats, five, six, a day,

In his greed; the women he leaves alway.

I cannot counsel you on how to free her,

But be content to hear she will not die.

Her life, I tell you, is not in danger,

For good or ill she’ll dwell here, in this sty.

But go, my son, remain here no longer,

Lest the Ogre should scent you, thereby.

Once here, he’ll sniff all about the house,

And can hear and scent the smallest mouse.”

The king replied that no, he would not go,

Until he had found his dear Lucina,

(And would die beside her, she should know),

Whom he esteemed, rather than desert her.

On finding she had naught to say, or show,

That could serve to move the monarch further,

The Ogre’s wife a new thought did admit,

Pursuing it with all her strength, and wit.

Canto XVII: 45-49: She plans a way for the king to join Lucina

There were slaughtered sheep and goats aplenty,

That her husband provided, in that place,

To serve their needs; from the roof hung many

A fleece, that would, in time, the dwelling grace.

She made the monarch take the grease, that she

Extracted, from a male goat’s guts, apace,

And coat himself with it, from top to toe,

That his true scent the Ogre might not know.

And when she thought that he gave off the scent

With which a fetid goat perfumes the air,

She took a fleece, and made the king consent

To creep inside, and so concealed him there.

And then she made him, crawling as he went,

Led by her, to the other cave repair,

Where his lady’s sweet face might be known,

Now hid behind that weighty mass of stone.

Norandino obeyed; and hugged the grass,

Beside the entrance to the other cave,

So that with the homeward flock he might pass,

And there, till evening, the odd bleat he gave;

For twas evening ere he heard the notes, alas,

Of the elder-pipe, with which that wretch did pave

His path, as he called the sheep from pasture,

And led them all, behind him, to his parlour.

Think how his heart trembled to the core,

Norandino, when he heard the Ogre there,

As, approaching close to the cavern door,

That dread face hung above him in the air!

But his love, and not his fear, was to the fore;

You’ll see if he feigned aught in this affair!

The Ogre then removed the stone, and so

The king, twixt sheep and goat, within did go.

The flock inside, the Ogre approached us;

But he first took care to replace the stone.

He sniffed around and after doing thus

Chose two to swallow quickly, flesh and bone;

At the memory, I grow nauseous,

And tremble, and sweat, and cry, and groan.

The Ogre left; the king cast off his fleece,

And then embraced his love, despite the grease.

Canto XVII: 50-57: He then helps the others to escape

Where she might have felt delight and comfort,

On seeing him, she felt fresh grief and pain;

She felt, now, that death would be his consort,

Since he could not prevent them being slain.

“Amidst my sorrows, it was sweet, in short”

She cried, “to know your freedom would remain

To you, and at least you would not suffer,

When we were dragged here by the Ogre.

While the very thought, that I must issue

Forth from this life, seemed harsh and bitter,

Twas for me to grieve, at that which must ensue,

As is the common instinct; now, whether

You die before or after me, tis true,

For your death, more than my own, I’ll suffer.”

And for Norandino’s peril she did show

More concern than for her own, I must owe.

“Yet Hope has led me here,” declared the king,

“To save you and your people, every one.

And if not, then tis better I die trying,

Than live blind without you, my living sun;

As I came, I may leave; and, so doing,

All of you may do just as I have done,

If you, indeed, can bear as I have borne,

The vile scent of a beast as yet unshorn!

Then he taught us the trick, to cheat the nose

Of the Ogre, that his wife had devised,

And, in any case, our bodies to enclose

In a fleece, that we might not be surprised.

Then, persuaded, as many sheep we chose,

As the number that our company comprised,

Men and women, and as many he-goats too

As that same, and then sheep and goats we slew.

Then we covered our bodies with the grease

That round about the goats’ intestines lay,

And we sheared, and each dressed in, a fleece.

When, from his golden dwelling, with the day,

Rose the sun, came the Ogre, to release

His flock and, by that orb’s first shining ray,

The shepherd raised a shrill note from his reed,

And summoned them to graze, as fate decreed.

He held his hand before the opening,

Lest his prisoners escaped midst the flock,

And held us by the door, feeling, smelling,

But, since he felt a fleece, none did he block.

Clothed in our shaggy coats, though unappealing,

Men and women issued forth from the rock,

And not one did the Ogre, there, restrain,

Till Lucina, in fear, the door did gain.

Lucina (whether loathing the idea,

Of coating herself, like us, in vile grease,

Or whether her soft step, as she came near,

Or slowness gave him pause, despite the fleece,

Or whether when he touched her, in her fear,

She cried out, as her terror sought release,

Or her hair tumbled down from her brow)

Was caught; though I cannot tell you how.

For, upon ourselves, we were so intent,

We gave scant thought to any other’s fate,

Yet I turned at her cry, as forth I went,

And saw he had un-fleeced her at the gate.

And driven her within, where she was pent.

We, in our quaint, and ambiguous state,

Moved with the flock where’er the shepherd led;

Amidst green hills, to pleasant slopes we sped.

Canto XVII: 58-63: But, with Lucina still captive, is forced to linger

There we waited, till, beneath the shade

Of a dense grove, the Ogre fell asleep.

Some sought the shore, some for the hillsides made,

Norandino, alone, his watch did keep.

Love of his lady thoughts of flight delayed;

He wished now to return, amidst the sheep,

Nor leave that place before his life was done,

Unless he freedom, for his wife, had won.

When he had issued forth amidst the sheep

And found that she alone was captive still,

Maddened by sorrow, he had thought to leap

Into the Ogre’s throat, and neath the mill

Of those sharp grinding teeth, and scarce did keep

From doing so; such, now, was not his will,

Hope sustained him, that he might yet save

His love, and lead her from the Ogre’s cave.

That evening, when the creature had, once more,

Penned in his flock, he found that we had fled,

His supper lost, vanished along the shore.

The blame he cast on poor Lucina’s head;

He made her stand (and heavy chains she bore),

On the very summit of the cliff, instead;

The king, whose plan had brought about her woe,

Felt like to die there; death escaped him though.

At morn and eve, the unhappy lover,

Was witness to her sorrow and her pain,

As amidst the goats and sheep, for cover,

He went to pasture, and returned again,

She, with sorrowful face, pleading ever

That he, for love of God, should not remain.

Since her love, by doing so, risked his life,

Yet lacked the means to rescue his poor wife.

Likewise, the Ogre’s spouse begged him to go,

But all in vain, for he refused to leave

Without his love; and the more she did so,

The firmer his refusal, I believe;

Sad was the servitude that bound him though.

Held by Love and Pity, naught did relieve

His state, till to that place came Gradasso,

And Agricane’s son, Mandricardo.

They wrought so well, those two together

That they swiftly freed the fair Lucina,

More by chance than cunning, however;

Then down to the sandy shore they bore her,

And placed her in the hands of her father,

Who was there; a morn like any other,

It yet seemed to Norandino, standing

In the cave, midst the flock, ruminating.

Canto XVII: 64-68: Lucina having been rescued, Norandino searches for her

But when he left the cave, as the sun rose,

And then discovered that his wife was gone,

(For the Ogre’s spouse told him, I suppose,

How it was achieved, and spurred him on)

He gave thanks to God, and did next propose,

To find his love, seek her thither and yon,

And then by arms, or prayer, or bribery,

Gain her side, and ensure her liberty.

Amidst the flock he lingered, by the bay,

And, rejoicing, wandered o’er the pasture,

Till slumbering, in the shade, the Ogre lay,

As was his wont, and his idle nature;

Then he journeyed onwards, night and day,

Until, no longer fearful of the creature,

He boarded a ship at Antalya,

And, in three days, arrived in Syria.

He had men search through North Africa,

Through Rhodes, Cyprus, Egypt, and Turkey,

For any sign of the fair Lucinda,

Nor had he news of her till, lately,

He heard she was safe in Nicosia,

With her father, the sailors, manfully,

Having fought with a gale, so furious

Southwards it had driven them, to Cyprus.

Filled with true delight, at the news he’d heard,

Our monarch prepared a sumptuous feast,

And, at every fourth new moon, so the word

Goes, he will grant the very same, at least;

Renewing the memory of the Ogre’s herd,

And the four months, ere she was released,

On that day, which is recalled tomorrow,

When the king found himself free of sorrow.

These things, I tell of, in part I saw,

And heard in part, from one who knows the whole,

The king, I mean; Kalends and Ides he bore,

Till grief had turned to joy within his soul.

And if, from some other, you hear more,

That some conflicting tale doth unroll,

Know, he errs.’ So, for Grifone, the knight,

Upon the reason for the feast, shed light.

Canto XVII: 69-72: Grifone prepares for the tourney at Damascus

A large part of the eve and night was spent

By these two men, in like conversation,

Who judged, therein, the monarch did present

Clear proof of his pity and affection.

Both then rising from the table, they went,

Each to his pleasant accommodation;

And when the morning broke, calm and clear,

Great cries of joy arose, from far and near.

With drums and trumpets men came running,

And all assembled in the market square,

While shouts along the streets went echoing,

The noise of carts and horses mingled there.

Grifone donned his armour, bright and gleaming,

Wrought in a manner that was rich and rare;

For the White Fay had cast a spell upon it,

Such that naught could shatter it, or pierce it.

The lover from Antioch armed, at his side,

Though a worse wretch never rode a charger,

Their host provided lances, true and tried,

While, of his kith and kin, a host did gather,

That with the knight into the square did ride,

Many a proud and worthy warrior,

With squires mounted, and on foot also,

To serve their needs, wherever they might go.

Once in the square, they waited, well apart,

Nor sought to show themselves in the field,

The better to see those of warlike art,

That came in two and threes, thus revealed.

One by his banner showed the lover’s heart,

His joy or sorrow lay therein, concealed,

Another, by his shield or helm, displayed

The cruelty or kindness of the maid.

Canto XVII: 73-80: Ariosto exhorts the West to reclaim the Holy Land

The Syrians, at that time, had adopted

The armour, and the weapons of the West;

Perchance to that manner and custom led

By the Frankish knights, and all the rest,

Who ruled the Holy Land, where He once bled,

(Almighty God, in human flesh) and blessed

The ground we proud Christians, to our shame,

Now leave the heathen hounds to scar and maim.

Where Christians should wield the sword and lance,

And, furthering our faith, claim lands anew,

Against each other’s forces they advance,

To the destruction of the faithful few.

You lords of Spain, and you, great lords of France,

And you the lords of Switzerland, and you

Of Germany, go, gain what is worth more;

For what you seek to win was Christ’s before.

If you would be true Christians, indeed,

And catholic in dominion, as in name,

Why do you slay Christ’s people? And then seed

The fields with destruction, to your shame?

Why, that kingdom of Jerusalem, concede,

That was once yours? Who else should we blame?

If Constantinople, with much the best

Portion of those lands, the Turks invest?

Spain, have you not North Africa nearby,

That has assailed you more than Italy?

While that great venture, ever, you pass by,

To bring, on us, yet deeper misery.

Beset with every vice, you, sleeping, lie,

My drunken Italy, content that we

Should play the handmaid to many a race,

Once subject to us, and in Rome’s embrace.

If fear of dying leads you Swiss to seek

Our aid, in Lombardy, and sympathy,

To beg for bread, among the poor and meek,

Or a helping hand to end your misery,

The Turks’ domains their ample wealth bespeak:

Drive them from Europe, and let Greece be free,

And in that way save yourselves from hunger,

Or die in foreign lands, and there win honour.

And what I tell you, I tell your neighbour:

You Germans, all the treasures of the West

That Constantine bore from Rome, and ever

Retained the finest, gifting all the rest,

All are there, and, there, the golden river

Pactolus, golden Hermus, all those blessed

Lands from Mygdonia to Lydia;

With the Holy Land, but a little further.

And you, Pope Leo, now ordained to keep

The keys to Paradise (immense their weight),

Let Italy not lie submerged in sleep;

Lift her head by the hair, redeem her fate.

You are the Shepherd; set to lead God’s sheep.

He gave the ‘ferula’; named you, of late,

That you might, likewise, roar; your arms extend,

And from the greedy wolves the flock defend.

Yet where stray I? Ever, from one thing

To another, it seems, I’m wont to go,

Yet think not to err so in my telling

That my former path I cease to know.

I said the Syrians mode of arming

Was like to the Frankish knights; even so,

In Damascus that crowded square was bright

With helms and breastplates, a glorious sight.

Canto XVII: 81-84: The prize assigned to the tournament

From their balconies, the fair ladies threw

Red and yellow flowers upon the jousters;

While, below, the trumpeters loudly blew,

And the proud horses pranced, as their riders

Displayed their skills, cavorting there anew,

Performing well or ill, amidst the others,

Such that one earned great applause, and was praised,

While some other a storm of laughter raised.

The tourney’s prize was a suit of armour,

Presented to the king some days before,

Which a merchant, coming from Armenia,

Had chanced to find upon the desert floor,

The king had added a surcoat, further

Nobly adorned, with pearls, and gems, and more,

Trimmed about with gold, in ample measure,

Rendering it a veritable treasure.

Yet, if the king had known the quality

Of that armour, he would have held it dear,

Above all such, and not, from courtesy,

And liberality, assigned it here

To serve as a reward for chivalry;

Though it will prove a lengthy tale, I fear,

To say who’d scorned it, and had left it so,

As a prey to those who passed to and fro.

Of that I will tell you further, later;

Now, more of Grifone at the tourney,

That saw many a lance break, its wielder

Launched upon a sudden earthwards journey.

Eight knights were joined there, in league, together,

Dearest to the king, truest of any,

Young men, well-practiced, all, in chivalry,

All noble lords, or of good family.

Canto XVII: 85-90: Martano, Orrigille’s lover, is defeated in the joust

These eight took on all-comers, on that day,

And one by one, dispensed with all that came,

At first with lance, then mace or sword in play.

The king, looked on, delighted with that same.

And often they would pierce a breastplate, say,

As though the thing were more than just a game,

As if of some true foe they took the measure;

Though the king could part them at his pleasure.

Orrigille’s lover, named Martano,

He of Antioch, a foolish coward,

Being with Grifone, thought he, also,

Possessed great skill, and put himself forward.

Into the lists he, thus, did, swiftly, go,

But halted there, before charging onward,

Until a joust between two knights had ended,

After which he’d attempt what he intended.

Of the eight, Seleucia’s lord made one,

Who, eager to maintain their enterprise,

Fought Ombruno, neath the morning sun,

Wounding that knight across the face and eyes,

Such that he fell there, mourned by everyone;

For many did that skilful warrior prize,

Not just for his skill, but his chivalry,

Praising him, above all in that country.

On seeing this, Martano felt great fear,

Lest, indeed, he should incur a like fate;

And, at once, his true nature did appear,

As his attempt he looked to terminate.

But Grifone, as he sought to disappear,

With many a word, harsh to contemplate,

Set him on a warrior, who held his ground,

As one, against a wolf, might set a hound,

That will, for ten or twenty yards, pursue

The beast, and then halt, and bark, at bay,

As the creature turns, and threatens him anew,

Its sharp teeth, and fiery eyes, on display.

Twas thus before the princes, in full view,

And all the lords and knights, there that day,

That Martano, now seized by fear and dread,

Tugged the reins to the right, and off he sped.

To be fair, twas the horse one might blame,

That sought to relieve itself of his weight;

But, after that, he fought so ill, that same,

E’en Demosthenes had left him to his fate,

As too hard to defend, so poor his aim;

Paper and not steel seemed his blade, his state

Was one of such fear, that, at last, half-dead,

Amidst the laughter of the crowd, he fled.

Canto XVII: 91-99: Grifone overcomes seven of the eight knights

Hands were clapped in mockery, midst the mirth

And the cries of those folk, on every side.

Like a fox, in the chase, that seeks its earth,

Martano, swiftly, from the lists did ride.

While Grifone felt the shameful loss of worth

Stained him also, as to that wretch allied,

Such that to leap into some blazing fire,

And die unseen, was now his fond desire.

With burning heart, and his face much the same,

He thought the knight’s disgrace was, thus, his own.

Because by such ill deeds, that brought but shame,

He himself, by that crowd, might now be known.

He needed, if he would redeem his name,

To allow his brightest skills to be shown,

And shine forth clear, lest the slightest error

Seem six yards though the breadth of a finger.

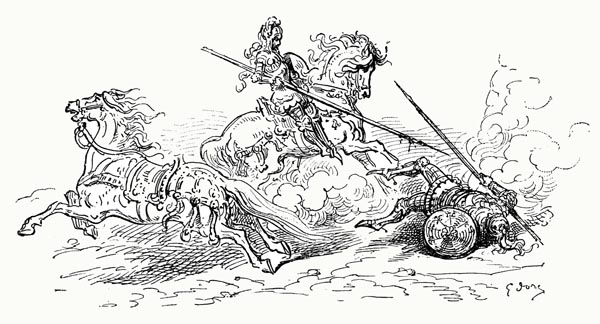

The lance already rested at his thigh,

Which he was rarely known to wield in vain;

He urged his steed to the gallop, and let fly

Dealing grief to his opponent, and sore pain,

Sidonia’s youthful lord, now like to die,

And then returned, and took his place again.

Overcome with wonder the spectators rose,

Their expectations confounded, I suppose.

Grifone charged, with the self-same lance,

Recovered sound and whole from the field,

And broke it in three, in his bold advance,

On the lord of Laodicea’s solid shield.

The latter lay on the croup, stunned perchance,

As three or four times he looked set to yield,

And fall, yet rose at last and drew his sword,

Wheeled his horse, and sent his challenge abroad.

Grifone, seeing him regain his posture,

The thrust having left him still on high,

Said to himself: ‘Well, it seems, the failure

Of the lance, now, the blade must rectify.’

And, on the forehead, he smote him, harder,

With a stroke, that seemed to fall from the sky;

And then equalled that with another blow,

Till he’d stretched him flat, on the ground below.

There came two brothers next, from Apamia,

Tirse the one, the other was Corimbo,

Accustomed, in the jousting, to conquer,

Yet downed by that son of Oliviero;

The first quit the saddle, while his brother,

Felt Grifone’s sword, and its mighty blow;

Thus, the common judgement was already

That our knight had indeed won the tourney.

Amidst the lists, now entered Salinterno,

Grand vizier, and marshal, to the king.

Who now governed the kingdom; he, also,

Was skilled at jousting, and at tourneying.

He was affronted that some foreign foe

Was about to take the prize and, seizing

A lance in his hand, called to Grifone,

Defying him with threats, loud and many.

But the latter answered him with a lance,

He’d selected, from ten weapons, as the best;

And lest he should err, in his swift advance,

Scorning the shield, he aimed straight at the breast.

It pierced between the ribs, and not by chance,

Protruding a palm’s length; and, to the rest,

Though not the monarch, welcome was the blow.

They’d loathed the greed of this Salinterno.

Two from Damascus, he now overthrew,

Their names Ermofilo and Carmando,

The first the king’s militia led, he knew,

Lord High Admiral was the other; though,

Flat on the ground, he laid the latter, too,

After the first left the saddle, at his blow.

Carmando’s steed was too weak to withstand

Grifone’s charge, and the lance in his hand.

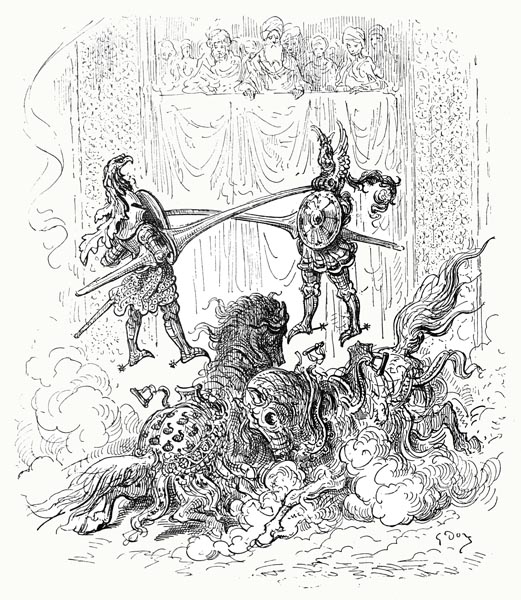

Canto XVII: 100-105: And lastly Seleucia’s lord

The Lord of Seleucia yet remained;

Than those seven, the greater warrior.

And his great rank and honour were maintained

By a fine steed, and by perfect armour.

Both at the vizor of the helmet deigned

To aim their lances, then spurred their charger.

As Grifone landed the firmer blow,

From the stirrup the foot slipped of his foe.

The threw the broken lances down, and wheeled,

And now, with drawn swords, they met together.

Grifone struck a blow, an arm revealed,

That might have cleft an anvil, without bother.

It shattered the bone and steel of the shield,

This lord had preferred to any another,

And had that not been double, like his coat,

The thigh had been cleft, on which it smote.

At the same time, the Lord of Seleucia,

Struck Grifone’s vizor such a blow,

It would have shattered it altogether,

Had it not been charmed and the rest also.

The other’s efforts gained naught however,

So dense was his armour, while the foe,

His mail was pierced and broken everywhere,

For not a stroke had failed to mark its share.

All could see Seleucia’s lord, that day,

Was inferior to this Grifone,

And he’d have seen his life reft away,

If the monarch had not, most suddenly,

Stopped the contest, by ordering away

His guards-captain, who entered swiftly,

And parted the knights from one another.

The king was much praised for it, thereafter.

The eight who had at first maintained their ground

Against the rest, had failed to defend

Themselves against one man, as they’d found,

And had vanished from the field, in the end.

The others set to fight, now stood around,

Absent those with whom they’d thought to contend;

For Grifone, alone, had conquered straight,

All those knights who had once comprised the eight.

Thus, the tourney’s duration was not long,

For in less than an hour the whole was done.

Norandino, to pacify the throng,

And prolong things, till the setting of the sun,

Descending from his balcony, among

The unwearied knights, assigned every one,

To one of two troops, by their rank and skill,

So as to grant them entertainment still.

Canto XVII: 106-108: The trio leave Damascus and halt at an inn

Meanwhile our knight, Grifone, had returned

To his lodgings full of anger and fury,

Thinking less of the honour he had earned,

And more of the scorn, with little glory,

That Martano had won, who bent to turn

The shame from himself, now spun a story,

While that most false and cunning courtesan,

Assisted, as she well knew how, her man.

Whether our knight believed her or no,

He received the excuse, most discreetly,

And thought that it was better that they go,

And, moreover, that they leave, silently,

Lest, catching sight of the shamed Martano,

The inhabitants might behave adversely.

So, by a short, well-hidden track, that day,

They passed the gates, and hastened on their way.

Whether he and the horse were battle-weary,

Or whether lack of sleep weighed him down,

Grifone stopped at the first hostelry,

Which lay scarcely two short miles from the town.

He doffed both his helm and armour, swiftly,

Had his steed unsaddled and, in his gown,

To the chamber assigned, he quickly sped,

Then, naked as a babe, took to his bed.

Canto XVII: 109-114: Martano, in disguise, is honoured as Grifone

No sooner had our brave knight laid his head

On the pillow than his eyes closed in sleep.

He slumbered more profoundly, in that bed,

Than a badger or a dormouse; sunk deep.

Orrigille and Martano strolled, instead,

In the garden nearby, and watch did keep,

While they plotted the strangest deception

That e’er was of human mind’s conception.

Martano planned to ride the very steed,

Grifone rode, steal his clothes and armour,

And approach the king, as if he were, indeed,

Deserving of the knight’s prize and honour.

No sooner was their vile deceit agreed,

Than he’d climbed aboard the milk-white charger,

In all Grifone’s gear and emblems dressed,

His coat of mail, white surcoat, and white crest.

With Orrigille and the squires, he appeared

In the square, filled as yet with a crowd.

Just as all the lances were being cleared,

The battle finished, in the time allowed.

The king requested, while the people cheered,

That they find the knight, both strong and proud,

With the white surcoat, crest and charger,

Since he knew not the name of the victor.

He who was dressed in armour not his own,

Like a donkey covered by a lion’s hide,

Was led, as he’d planned, before the throne,

In the place of Grifone, since he’d lied.

The king on seeing him, this knight unknown,

Rose, embraced him, and set him by his side,

Nor thought it quite enough to laud and praise,

But wished him to remember this, always;

And so pronounced him, to the trumpets’ blare,

The winner of the tourney for that day,

And had his name conveyed to all those there,

An unworthy name, but be that as it may,

And proclaimed that his carriage he must share

When to the palace he’d soon make his way,

And showed him such honour, of his grace,

As brave Hercules or Mars did once embrace.

He granted him fine lodgings, at his court,

And honoured fair Orrigille, likewise;

Knights and squires to attend on them he sought,

Unaware of Martano’s bold disguise.

But it is time that I spoke, as I ought,

Of Grifone, lying there with closed eyes,

Fearing nothing, least of all deception;

Nor did he wake until the day was done.

Canto XVII: 115-118: Grifone repents of his foolishness

Once he woke from sleep, and saw the hour,

He hastened, in his gown, from the chamber,

Seeking Orrigille; the place did scour

For a sign of her, and her (false) brother.

And when he found her not, e’en in the bower

Midst the garden, nor his clothes and armour,

He grew suspicious, more so when he saw

Martano’s gear, where his had lain before.

His host appeared, and told him that the knight

Had gone with the lady to the city,

And how he had clothed himself all in white,

And that, with him, went all their company.

Grifone, little by little, saw the light,

Perceiving all that Love had, cunningly,

Kept hid, and his slowness to discover

That Orrigille’s ‘brother’ was her lover.

He was grieved by his utter foolishness;

In that, having heard the tale the pair told,

He’d allowed himself to excuse a mistress,

That had betrayed him, so often, of old.

He had missed his revenge; nonetheless,

Though the wretch had, but now, escaped his hold,

He could pursue him; though, constrained, indeed,

To employ the villain’s armour and steed.

An error: twere better had he followed,

All naked and unarmed than fully clad

In the shameful gear that he had borrowed,

Nor seized that miserable shield, as he had,

Nor the helm; yet ire at having swallowed

Their lying tale, had driven him half-mad;

Thus, to the city, hastening on his way,

He came, while there was yet an hour of day.

Canto XVII: 119-125: He is mistaken for Martano

Near to the gate by which our knight entered,

Upon his left, a splendid castle stood.

Strong it seemed, and readily defended,

Its walls, and its buildings, sound and good.

The king, by the Syrian lords attended,

And their ladies, of that neighbourhood,

Were met there, in a pleasant chamber,

Enjoying a rich, and sumptuous, supper.

The fortress towered above the city wall,

While from it their balcony projected,

Thus, allowing a wide view over all

The villages about, by roads connected.

So that when Grifone approached the hall,

Now dressed as one the crowd had rejected,

It was his unhappy fate to be seen;

By the king and his courtiers, I mean;

Thinking him the man whose crest he bore,

The lords and ladies were moved to laughter.

Vile Martano sat near the king, secure,

Basking in the royal grace and favour,

With the lady by him, suited far more

To him than to our knight; the king, further,

Sought, smilingly, to know the coward’s name,

That, treating honour lightly, courted shame,

And, after so sad and ugly a display,

Now returned, to the town, quite brazenly.

And remarked: ‘It is most strange, I must say,

That a knight so worthy, as all can see,

Should associate with him, in this way,

He the greatest coward in this country;

Perchance tis so your own worth and honour,

By contrast, may shine forth all the brighter?

By the eternal gods above, I swear,

That were it not for my regard for you,

Public ignominy he’d be made to share,

With all others of like cowardly hue.

And a lasting memory he would bear,

Of my loathing for all that craven crew.

And know that, if unpunished he depart,

Tis only thanks to you, that take his part.’

That sink of every earthly vice replied:

‘Royal sire, I know not who he may be,

I came on him, by chance, the road beside

As we came from Antioch on our journey.

His martial guise misled me, I’ll confide,

Such that I thought him fit for company,

Though I’ve seen naught of the man, I may say,

More than his sad performance here, today,

Which so displeased myself, that naught remains

But to punish his extreme cowardice,

By ensuring that he bear not, for his pains,

A lance or sword again, within the list;

Though I bear such respect in my veins,

I give way to your majesty, in this.

Yet I’d not desire him to boast that he

Spent a day, at least, in my company.

Canto XVII: 126-128: Norandino devises his punishment

For I am tarnished, by association,

Tis a weight upon my heart forever;

And if, to the shame of your brave nation,

I see him depart, as bold as ever,

All untouched, I shall seize the occasion;

Though, indeed, to see him hang were better,

A noble deed, if done in princely style.

Let him dangle there, a mirror to the vile.’

Without a sign from him, Orrigille

Added her confirmation. ‘Come now,’ said

The king,’ I think, though he is a sinner,

Tis wrong to take his life for such; instead,

For a deed so ill, twould prove far better

For him to entertain, in fear and dread,

My people,’ so he summoned up a lord,

To arrange what might true pleasure afford.

This lord departed, with a squad of men,

And descended to the city gate below,

Posted them round him, silently, and then

Waited for the cowardly knight to show.

He surprised him, as he returned again,

And twixt the drawbridges took him so,

And detained him, with mockery and scorn,

In a dark cell, until the coming morn.

Canto XVII: 129-130: Martano and Orrigille depart

The Sun had scarcely raised his golden hair

From the bosom of his ancient nurse, and then

Begun to chase, through all the mountain air,

The shadows from the peaks, and gild again

Their lofty crests, when Martano, whose care

Was to ensure that Grifone, from his pen,

Was not released in time to state his cause,

Ere he was gone, took his leave, without pause.

He gave a plausible excuse for going,

And not waiting for the spectacle decreed,

The king, on him, many a gift bestowing

Besides the prize, undeserved, for his deed,

And letters patent, most bravely showing

That in high honour he was held indeed.

Let him go; for I promise he’ll receive

All that’s merited by those who deceive.

Canto XVII: 131-135: Grifone frees himself from his captors

Grifone was dragged to the square, in shame,

(The place was all about with people set)

His helm and breastplate torn from the same,

Leaving him clad only in his doublet.

And, as if his life they were about to claim,

He was chained, high on a cart, there to sweat,

Pulled along by a pair of cows, slowly,

That, long unfed, seemed both weak and weary.

Round this ignoble chariot, appeared

Old crones of ill repute who, each in turn,

Played charioteer, while the others jeered;

And many a curse from them did he earn.

But more than any cries of shame he feared

The idle lads; they proved of more concern;

Hurling stones, viciously, at his bare head,

That, but for wiser folk, had seen him dead.

The vile armour, that had proved the reason

For his ills, though twas not, in truth, his own,

Was strung behind the cart and, thereupon,

Was drawn through the mud, that deep had grown.

Then they halted, at a platform, whereon

Martano’s sin was proclaimed and known,

As if the shame were his, the crowd around;

Before his eyes, and to the trumpets’ sound.

Then they bore the captive thence, and displayed

Him, there, before the houses, temples, stores,

Nor spared their mockery (to be repaid),

And curses nigh unheard of on our shores;

And led him to the gate, in vast parade,

Persuaded of the virtue of their cause,

Ready to drive him forth, with many a blow,

Though little of their victim did they know.

No sooner had the crowd set free his feet,

And then his hands, from that heavy chain,

Than his two eyes with sword and shield did meet,

And the blade he wielded, with might and main;

His advance, not a pike or spear did greet,

While the foolish folk, unarmed, fled in vain.

Yet, to the next one, I’ll defer the rest,

For to end this canto here, that were best.

The End of Canto XVII of ‘Orlando Furioso’