Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XVI: Rinaldo at the Siege of Paris

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XVI: 1-4: The pains of misplaced love

- Canto XVI: 5-7: Grifone finds the lovers near Damascus

- Canto XVI: 8-13: Orrigille lays the blame on Grifone

- Canto XVI: 14-16: He accepts her excuses

- Canto XVI: 17-20: We return to Paris under assault from Agramante

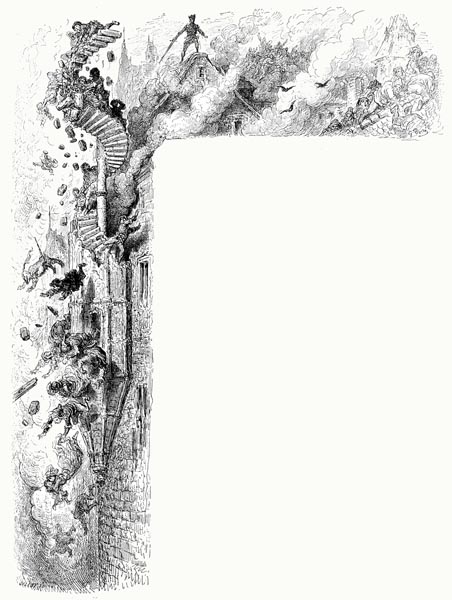

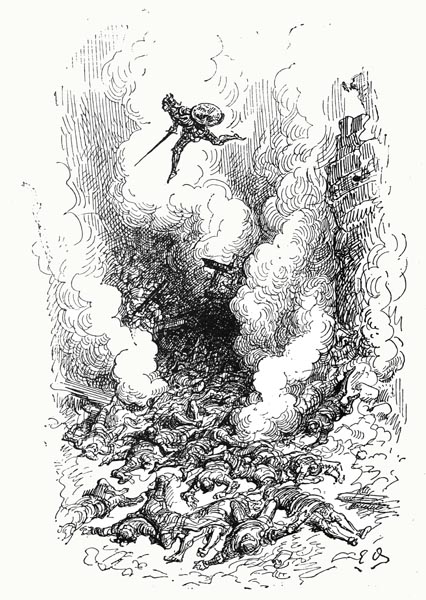

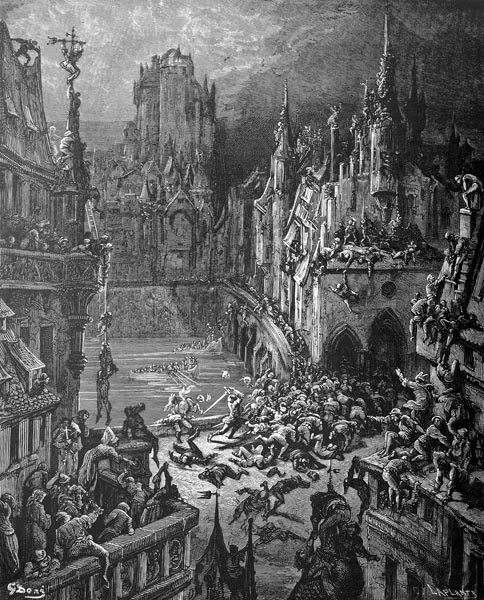

- Canto XVI: 21-28: Rodomonte runs amok within the city

- Canto XVI: 29-38: Rinaldo arrives, and exhorts his men

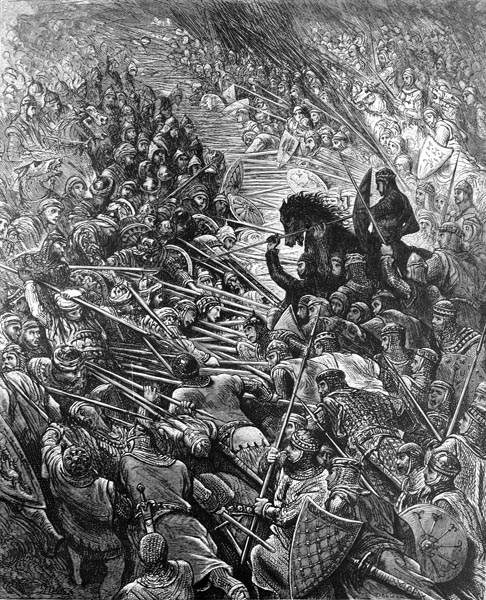

- Canto XVI: 39-42: He deploys, near to the Moorish army

- Canto XVI: 43-48: Rinaldo slays Puliano, King of Oran

- Canto XVI: 49-54: Then, with Zerbino, presses on against the foe

- Canto XVI: 55-58: The Scots engage on a broader front

- Canto XVI: 59-65: Zerbino’s exploits

- Canto XVI: 66-70: The deeds of the English contingent

- Canto XVI: 71-74: Ferrau enters the fight

- Canto XVI: 75-78: King Agramante attacks the Scots

- Canto XVI: 79-84: Rinaldo unseats Agramante

- Canto XVI: 85-89: Charlemagne views Rodomonte’s trail of destruction

Canto XVI: 1-4: The pains of misplaced love

The pains of love are many, and full sore,

Of which I have endured the major part;

And, to my cost, well read in them, and more,

Can speak of them as twere my trade or art.

Thus, if I say, or if I’ve said before,

In speech or on the page, and from the heart,

‘Love’s ills may seem light, or harsh and bitter’,

Believe me, my judgement’s all the truer.

I say, have said, and, till I die, will say,

That he who’s caught in a most worthy snare,

Though his lady scorns his desire alway,

And to his greatest wish gives little care,

Though Love deprives him of his rightful pay,

His time spent wearily, his pleas but air,

He, while his heart is ever aimed on high,

Should grieve not, though he’s like to fade and die.

Let him lament, who ever serves as slave

To two bright eyes, and to lovely tresses,

Beneath which, yet, a wanton heart betrays

Itself, and what’s far from pure addresses.

The saddened wretch would fly, but feels always

The arrow’s wound, a stag the hunt presses,

Ashamed both of himself, and of his love,

Afraid to speak, yet helpless to remove.

Lo, in this sad case, was young Grifone,

Who saw his error, yet could not amend it;

He knew his heart was set, most foolishly,

On faithless Orrigille; he did own it.

Yet ill-use o’er reason gains the victory,

While to appetite yields our will and wit.

Howe’er treacherous, thankless, vile is she,

We’re forced to seek for her, where’er she be.

Canto XVI: 5-7: Grifone finds the lovers near Damascus

I say, resuming now my lengthy tale,

That he left Jerusalem, secretly,

Nor his brother with his plans did regale,

Who’d reproved his foolishness, frequently.

But northwards he, to Ramla, sought a trail

Borad and level, and the going easy;

Six days then to Damascus, as he thought;

From there, Syrian Antioch he sought.

Just north of Damascus, he met the pair,

She, and the lover her heart had claimed,

As well-matched (in the sins they did share)

As flower and stem, and equally shamed

By their light hearts, forever free of care.

One a flirt, one a traitor might be named;

While each one hid their respective defect,

To others’ cost, neath a courteous aspect.

Now, tis fair to say, the lover, a knight,

Came, fully armed, on a mighty charger,

With Orrigille, a most gorgeous sight,

In a dress of blue, with a gold border,

And two men at the rear, left and right,

Bearing one his shield, his helm the other;

For, to Damascus, they all did journey,

To make a brave display at the tourney.

Canto XVI: 8-13: Orrigille lays the blame on Grifone

Now, the King of Damascus, on a day,

Had declared a festival, the reason

For their visit and their gaudy display,

And there too came many a champion.

On seeing Grifone, she felt dismay,

Fearful of his scornful opinion,

Knowing that her knight might, in a breath,

Being the weaker man, face sudden death.

Yet she was so audacious and cunning,

(Though she shook from head to foot with fear)

That she fixed her expression, adopting

A pleasant tone, and let no trace appear

Of her anxiety, while alerting

Her lover, and, as if he were her dear,

Ran to Grifone, stretched her arms out wide,

Then clasped his neck, hung there awhile, and sighed.

Matching each affectionate gesture

To her suavity of speech, oft weeping,

She said: ‘My lord, is this the due measure

Of my reward, for praising and adoring

Your good self, to live as a lone creature

A year, nigh on two, and you not grieving?

And, had I waited there till you returned,

I know not if your presence I’d have earned.

When, every day expecting you’d appear,

From Nicosia, and the high court there,

Holding me (infected with the fever!) dear,

Whom you left (fearing death!) in others’ care,

I heard you’d gone to Syria, then drear

Were my days, and my sorrows harsh and rare,

Such that, without the means to follow you,

I near pierced my loving heart quite through.

But Fortune, by her double gift, has shown

More care for me than you have ever done,

She sent my brother here, who is my own

Screen against dishonour; that is the one

Gift; then that you’ve searched for me, to atone,

Which I prize more than aught else neath the sun,

And in good time, for had you stayed longer,

I’d have died of a love, ever stronger.’

The deceitful minx so pursued her theme,

(Worse than a fox for subtlety that same)

And so astutely worked her cunning scheme

That poor Grifone now received the blame,

While he was forced to treat with high esteem

This relative, her flesh and blood, in name,

And thereby swallow her whole deception,

As if it held more truth than Luke or John.

Canto XVI: 14-16: He accepts her excuses

For, not only did he fail to reproach her,

That wicked, though more than lovely, fay,

But he took no vengeance on her lover,

Who’d made her his mistress, but sought a way

Instead to defend himself, and rather

Deflect some portion of the blame away;

While by her brother (for so she’d professed

Him to be) she was oft kissed, and caressed.

And so, he rode, with our knight, to the gate

Of Damascus, while telling good Grifone

That the wealthy King of Syria, had of late

Announced he would hold a sumptuous tourney,

And that whoever came, or poor or great,

And of whatever faith he chanced to be,

Whether Christian or other, could stay

There safely, while the feast was under way.

However, I now choose not to follow,

The tale of deceitful Orrigille,

Who, in her day, not one loving fellow,

But a thousand, treated as perversely.

I turn to Paris; where with blow on blow

Two hundred thousand men yet warred cruelly,

(Scorched by the sparks of that dreadful fire)

Bringing its people fear, and pain, and ire.

Canto XVI: 17-20: We return to Paris under assault from Agramante

I left you at the point where Agramante

Had launched his fierce assault upon a gate,

Which he had thought he might attack freely,

It lacking guards, abandoned to its fate.

Yet King Charlemagne kept watch there, nobly,

With many a master of war, he did wait,

Two Angelinis, Guidos, Angeliero,

Otone, Avino, Avolio, Berlingiero.

The men on both sides sought now to display

Their prowess before king and emperor;

Knowing that praise and riches, on that day,

They might win by true service in this war.

But the Saracens could not repair, I say,

The damage they incurred, troubled sore;

A tithe lay dead, pierced in face and breast,

Which spoke of their brave folly to the rest.

A hail of arrows, from the city-wall,

Rained down upon the enemy below;

Up to the trembling sky, rose cry and call,

From the defenders, and the crowded foe.

But Charles and Agramante I must stall;

To sing of Africa’s great Mars, I go,

King Rodomonte, devoid of pity,

Who now ran amok, amidst the city.

I wonder if, indeed, you yet recall

That Saracen, of reckless bravery,

Who, twixt the outer and the inner wall,

Had left so many of his company

Consumed there by that great fiery squall,

A sight to arouse the Christians’ pity;

And how he’d cleared the moat at a bound,

Reaching the very summit of the mound.

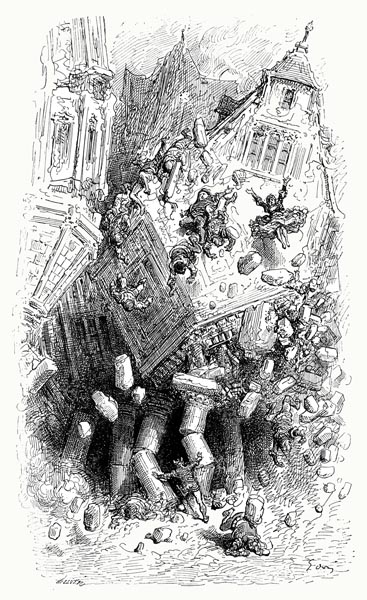

Canto XVI: 21-28: Rodomonte runs amok within the city

Once the Saracen intruder was spied,

With scaly hide, and clad in strange armour,

By the old and weak, gathered there, inside,

Now hanging on every whispered rumour,

Cries of grief and woe spread far and wide,

Lamenting, they beat their palms together;

While none, indeed, remained there who could flee,

To house or shrine, and scape the enemy.

Yet this the cruel sword to few conceded,

Which the mighty Saracen swirled around,

As here a foot, and half a leg, were ceded,

While there a head went flying to the ground;

One man, sliced across, his cries unheeded,

Another, by the falling blade, uncrowned;

While of the many conquered in that chase,

Not one of them bore wounds on chest or face.

What the tiger wreaks on the fearful herd,

In the Hyrcanian field, or by the Ganges,

What, by the lambs and goats, is oft incurred

On Etna’s slopes, when’er the wolf doth please,

This pagan executed, in a word,

Not on squadrons, but mere crowds of these

Sad folk, like sheep, of life now swiftly shorn;

All deserving of death, ere they were born.

Not one of them would look him in the face

Of the many that he pierced, cut, and maimed.

All that street, which leads towards the space

Before Pont Saint-Michel, the pagan claimed,

Whirling his sword, as onwards he did race;

Careless of lord or servant, his blade aimed

At sinner and saint alike, running swiftly,

Went the proud and fearsome Rodomonte.

His religion proved no shield to the priest

Nor innocence a safeguard to the child,

Nor kind eyes and crimson cheeks to the least

Of ladies or maidens, meek and mild,

While the old struck at their chests, ere they ceased

To breathe, where the king, as cruel and wild

As he was brave, ran up the street in rage,

Not distinguishing by rank, or sex, or age.

Nor did that Lord of the Impious stain

His hands with human blood and gore, alone,

But against the walls, of houses, he was fain

To hurl himself (for few were made of stone,

In those days) bearing gouts of fire in his train.

(I well believe it, for tis widely known

That Paris then like some dense forest stood,

And six in ten there are still made of wood)

Though all was alight, it seemed his hatred

Was still far from quenched and, where’er,

He applied his hands, the disaster spread,

Tumbling roofs far and wide, naught did he spare.

Never, at Padua, was bombard seen so dread,

When the mighty battle was raging there,

Or so powerful in shattering its wall,

As this king was, who made great houses fall.

If, while Rodomonte exercised his sword

And brought flames to the streets of the city,

Agramante had pressed hard, be assured

Paris had been lost; and his, the victory.

But he was thwarted by a warrior lord,

A valiant knight midst the English army,

Racing to their aid, with the Scots, that day,

Led by Silence, and Saint Michael, on the way.

Canto XVI: 29-38: Rinaldo arrives, and exhorts his men

God willed that, while the King of Algiers brought

Fire and destruction to the streets within,

Rinaldo came, that flower of every court,

To Paris, with the English, and their din.

Three leagues above, a bridge he laid athwart

The Seine, and by the left bank then did win

They way, such that in moving to attack,

The river would be sited at their back.

He’d commanded six thousand fighting men,

All archers, led by Edward, to the fore;

With him two thousand light-cavalrymen,

Under Ariman; from Picardy’s far shore

By the swiftest roads they sped, who then

By Porte Saint-Martin might enter in; or

By Porte Saint-Denis bring Paris succour,

And defend her safety thus, and honour.

And after them he’d sent the baggage train,

With their equipment, by the shortest road,

While, with the troops that did still remain,

He made a circuit, where the river flowed;

Bridges and boats he bore to cross the Seine,

Fords being scarce, as ruin there he sowed,

Downed the bridges to his rear, by design,

Then ranked the English and the Scots in line.

But bringing, first, the knights and captains, there,

In a ring about him, stood atop a hill

High above the plain, where all could share

His words, and hear all his thoughts and will.

‘My lords,’ he cried, ‘give thanks in prayer,

To God, who guided us, and leads you still,

Who, through your sweat, and a little valour,

Above every race, shall bring you honour.

Through you two princes shall be defended,

If, from siege, you now relieve this city;

Your own king who, ever, has depended

On you, his wall gainst death or slavery;

And one whose praise has e’er ascended

Above, your emperor, throned in majesty;

And, with them, other kings, and dukes, and knights,

Many a lord, that in wide lands delights.

Thus, in saving this city, not only

Parisians shall be obliged to you,

Fearful, and saddened by more than merely

Their own despair, but that of others, too,

Of their dear wives and children, who clearly

Share their trouble, risking all anew,

And those virgins, cloistered, dedicated,

That pray their chaste vows be not frustrated.

I repeat, that in rescuing this city,

Not only will all Paris hold you dear,

But the folk of every Christian country,

Of lands that support her, far and near;

For all of Christendom owns to many

A brave soul midst those beleaguered here.

By victory, in what must now ensue,

More than the French will be obliged to you.

If, for rescuing one worthy citizen,

The soldiers of old received a crown,

Then for shielding the lives of many men,

What reward? Or for saving a whole town?

Shall jealousy now, or sloth, yet again,

Bring these most sacred walls tumbling down?

Believe me, should this city not endure,

Nor Italy, nor Germany, stands secure;

Nor any other land where men adore

That Christ, who died for us, upon the Cross.

Think not that distance saves yours from the Moor,

Nor that the sea shall keep those isles from loss,

For if from Gibraltar, or their native shore,

Those Gates of Hercules they quit, because

Fresh plunder and new riches they’d command,

What will they do once they possess this land?

And if nor gain nor honour leads you here,

To play your part in this great enterprise,

Then tis our common duty to appear,

And aid our Holy Church, in martial guise.

Nor this weakened enemy should you fear,

You’ll see how swift their broken army flies,

Its inexperienced troops, in their fright,

Lacking armour, strength, or guts for a fight.’

Canto XVI: 39-42: He deploys, near to the Moorish army

Thus, it was that, in clear and fluent speech,

Rinaldo gave to valiant knight, and lord,

And eager captain, every and each

Good reason why he should his aid afford

To Paris, although he sought to preach

To the converted, their loyalty assured.

His speech done, he ordered them quietly

Beneath their banners, all and separately.

Without noise and murmur on the way,

The tripartite host deployed; Zerbino,

Marching along the river-bank that day,

Was granted the first meeting with the foe,

While the Irish were sent further away,

Taking a wide arc; twixt the two did go

The English cavalry and infantry,

The Duke of Lancaster, leading boldly.

As soon as this was done, brave Rinaldo,

Galloping his mount along the river,

And, swiftly overtaking Zerbino

And his men, their passage slower,

Came to where Oran’s king, and Sobrino,

Had quartered the Moorish troops together,

Who, half a mile or so from those of Spain,

Were positioned to guard the open plain.

The Christian army, who, on their side,

Had arrived most safely and securely,

Led there by Silence, and their Angel guide,

No longer waited for action, quietly;

On hearing the foe’s loud cries, they replied,

Making the shrill trumpets sound out fiercely,

Filling the heavens, once and then again,

And chilling the heart of every Saracen.

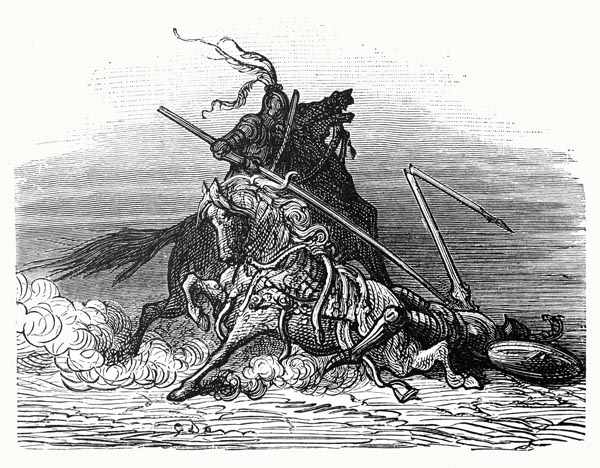

Canto XVI: 43-48: Rinaldo slays Puliano, King of Oran

Rinaldo spurred his mighty steed ahead.

Past all the company, with lowered lance;

A bow-shot’s length, beyond the Scots, he sped,

Tired of delay, impatient to advance,

As a sudden gust of wind oft is bred

Within a coming storm, and forth will dance,

So, before the following troops, indeed,

Did the knight, urging on Bayard, his steed.

The coming of this French paladin,

Brought to the watching Moors a taste of fear;

Hands trembled on the lance, deep within

The ranks, feet and thighs too, with that spear,

As they gripped the saddles; but, amidst the din,

King Puliano, his gaze firm and clear,

Not knowing him, nor anticipating

A mighty shock, set his charger moving.

He stooped above the lance as he sped on,

Calm and collected for the encounter,

Then abandoned the reins and, thereupon,

With his spurs alone, urged on his charger,

While the knight, betraying no deflection,

Feigned not, revealing by his fierce ardour,

His epithet (his skill writ in the stars)

Not Amone’s son, but the son of Mars.

Well-matched, the pair exchanged cruel blows,

Their lances sought to strike each other’s head,

Yet, unequal in arms and strength these foes,

The one rode on, the other fell stone dead.

A clearer sign of skill the true knight shows

Than simply a stout lance thrust out ahead,

But good fortune a knight needs even more,

Without which, victory is never sure.

Grasping the lance tightly, Rinaldo flew

Towards Puliano, who was possessed

Of the massive bulk, and bone, and sinew

To resist, but not the courage; for the rest,

The blow Rinaldo gave was sound and true,

The stout shield’s lower rim put to the test;

And all those who decline to praise that blow,

No lance had ere reached higher, you should know.

And, then again, the shield he’d pierced right through,

Though wrought of palm without, and steel within,

So that forth, through the belly, his soul flew,

And, slighter than his frame, a path did win;

While the charger, a mount both good and true,

That had thought all day that weight to underpin,

Gave thanks, internally, to our brave knight

Who’d eased him, with the outcome of the fight.

Canto XVI: 49-54: Then, with Zerbino, presses on against the foe

His lance shattered, Rinaldo wheeled his steed

So swiftly that it seemed the beast had wings,

And where the ranks seemed thickest indeed,

Launched himself; as a thorn pricks and stings,

Blood-stained Fusberta, his blade, now freed,

Stabbed arms like panes of glass, while its swings

Biting not through some solid, armoured sheath,

But wood and cloth, soon found the flesh beneath.

Few tempered plates with iron pins it met,

That sharp descending blade, where’er it fell,

But shields of oak or leather, weaker yet,

And quilted coats and turbans, that dispel

Light blows alone; while his furious onset

Thinned, cleft, pierced, cut, and sheared his foes as well,

Who could no more against his sword prevail,

Than grass against the scythe, or crops the gale.

The foremost squadron he had put to flight,

When, with the vanguard, came brave Zerbino.

Before his men, rode out that valiant knight,

With levelled lance, while the rest did follow;

The Scots beneath his banner, roused to fight

With equal ardour, ran to launch their blow;

Like fierce wolves they seemed or lions, that reap

A bloody path amongst the goats and sheep.

Both the knights, with lowered lances, pressed

Against the foe; between them little space,

As their fleeing enemies they addressed,

Eating up the ground, speeding on apace;

No stranger dance was ever so expressed,

For no pagan dared the fierce Scots to face;

One cut and pierced, the other fled and died,

As if led there to perish and abide.

The pagans’ hearts grew colder now than ice,

Those of the Scots hotter than scorching flame.

The Moors began to think, caught in that vice,

Their foes Rinaldos, mighty as that same.

Sobrino now advanced, not waiting twice

For the herald’s call; onwards they came,

His braver troops, responding to the cry,

More skilful, better armed, prepared to die,

Worthier to fight the African cause,

Though not deemed worthy of the greatest prize;

Dardinello, led his ill-equipped Moors,

Inexperienced in battle, to our eyes;

He had a shining helm, wrought on those shores,

His limbs sheathed in metal, and likewise

His breast; while the fourth company, the best,

Beneath Isolier, now stirred from rest.

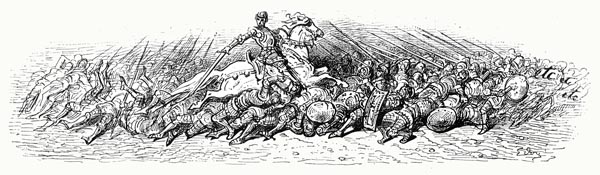

Canto XVI: 55-58: The Scots engage on a broader front

Meanwhile the Duke of Marra, brave Thraso,

That rejoiced in the fray, had raised the bar

To the lists, bidding his soldiers follow,

Seeing Isolier lead out Navarre,

Hearing the pagans cry against the foe,

Longing to reach those pagans from afar;

Then Ariodante roused his company,

He who’d been made the Duke of Albany.

The rising noise of the shrill trumpeting,

The sound of drums, and uncouth instruments,

The twang of bows, and the slings’ loud whirring,

The creaking machines, their wheels in torment,

And above the din, and all that groaning,

The cries, and roars, and moans of sore lament,

Were louder than the cataracts’ swift fall,

With which the Nile, descending, deafens all.

Twin flights of arrows from the armies soared,

Darkening the whole heavens in their flight.

A mist of dust, breath, sweat issued abroad,

Filling the air, and challenging the light.

One side advanced, the other would afford

Them ground, then change places, in the fight,

Leaving the dead, with the foes they’d slain,

Revealed to sight, spread-eagled, on the plain.

Where a squad withdrew, through weariness,

Another swiftly came to fill its place;

From here and there, men marched into the press,

Or rode their steeds towards an empty space;

While Earth, beneath them, bloodied now no less,

Her verdant cloak, bright crimson did deface.

And where but blue and yellow flowers had been,

Now men and mounts lay dead amidst the scene.

Canto XVI: 59-65: Zerbino’s exploits

Zerbino wrought many a wondrous deed,

More than any at such a tender age.

He many a foe to his death did lead,

Bringing destruction on them, in his rage;

While Ariodante, his men agreed,

Showed as a paragon upon that stage,

Filling with dread and wonder, from afar,

The soldiers of Castile, and of Navarre.

Chelindo and Mosco, bastard brothers,

(Calabrun of Aragon, their late father)

With one well-respected by the others,

Brave Calamidor of Barcelona,

Left the standard, covering each other’s

Backs, and hoping to win fame forever

By slaying this Zerbino, in due course

Succeeded in wounding the prince’s horse.

Pierced three times in the flank, the creature died,

While Zerbino rose quickly to his feet;

Striking his foes, vengeance aloud he cried,

Eager to bring about their swift defeat.

And first to Mosco his sharp blade applied,

Who’d hoped to make the victory complete,

Piercing him, in reply, such that he fell

Into the dust, and there the man did dwell.

Seeing him fall, as by a stealthy blow,

Chelindo his brother, filled with fury,

Thinking to surprise him, charged Zerbino,

But the latter seized his bridle, swiftly,

And brought his war-horse down, at a blow,

Destined never again its stall to see,

For so mighty was the stroke, full and true,

Both the warrior and the mount, he slew.

When Calamidor saw the other fall,

He gripped the reins, to turn and quickly flee,

But Zerbino struck hard, seeking to forestall

His flight, from behind, while crying, fiercely:

‘Stay, traitor, stay!’ The stroke, unlike his call,

Failed to reach the rider, straying slightly,

But fell hard across the horse’s croup, and so,

Brought the charger to the ground, at a blow.

Quitting the saddle, crawling o’er the ground,

The Spaniard sought safety, but in vain,

For Thraso’s charger, that the earth did pound,

Passed over him, and struck him hard again,

As many an enemy now gathered round,

Our captains went racing o’er the plain,

Ariodante and Lurcanio,

To bring a spare mount to Duke Zerbino.

Twas then Margarno and Artalico,

Felt the force of Ariodante’s blade;

Casimiro and, likewise, Etearco,

For, more heavily still, on them it weighed.

The former pair escaped all further woe;

The latter fell to earth, their last debt paid.

Lurcanio revealed his prowess too,

Who charged, and struck, and overturned, and slew.

Canto XVI: 66-70: The deeds of the English contingent

Think not the conflict raging on the plain

Was less intense than that by the river,

Nor that the Duke of Lancaster was fain

To maintain his place, and merely linger;

Rather he moved against the ranks of Spain,

Where the fighting was long and bitter,

For horse, and foot, and their brave captains’ skills

Ensured a battle of opposing wills.

Forward went Oldrado and Fieramonte,

Those brave Dukes of York and of Gloucester,

With them moved Richard of Warwick, swiftly,

Henry, Duke of Clarence, followed after.

They faced Follicone, battling fiercely,

Brave Baricondo, and Matalista;

Those from Almeria, and from Majorca,

They led forth, and all those of Granada.

At first, the fight seemed balanced equally,

With but small advantage, though men died;

One, then the other, moved forward slowly

Then backward, like the rippling of the tide,

Or like the wheat, in a May breeze, stirred gently,

Swayed to and fro, and from side to side.

But when Fortune had toyed with them a while,

Upon the Christians she chose to smile.

At the same time the Duke of Gloucester

From his saddle toppled Matalista,

While Fieramonte, skilful as ever,

Struck Follicon, piercing his right shoulder,

And overthrew him; one and the other,

Midst the English, were taken prisoner,

As Clarence’s hand, high above the strife,

Robbed Baricondo, as it fell, of life.

The Moorish troops knew great fear, at the sight,

While the Christians felt greater ardour;

Thus, the former, instantly, took to flight,

The latter advancing with fresh fervour,

Gaining ground, as their foes ceased to fight,

Then hounding them, ere they could recover;

And if none had come to the pagans’ aid,

Then all there had been captured, or unmade.

Canto XVI: 71-74: Ferrau enters the fight

But Ferrau who, until that moment came,

Had scarcely left King Marsilius’ side,

On witnessing the rout, was filled with shame,

As their troops, in flight, scattered far and wide,

He spurred his charger; deep into that same

Throng of men he plunged, that ebbing tide,

Just as Olimpio de la Serra,

Struck in the head, was silenced forever.

A youth he was who, with his sweet singing

Attuned to the tones of the twin-horned lyre,

Melted every heart, and set men dreaming,

Hard though they were, or devoid of fire.

Happy were he if he had scorned the fighting,

And sought fame pursuing his first desire,

Eschewing the scimitar and the lance,

That led one so young to his death in France!

When Ferrau saw Olimpio overthrown,

One whom he loved, and held in high regard,

He felt more pity for that youth alone,

Than for a thousand others slain and marred,

And cleft the man that struck him to the bone,

Splitting the helm in twain, the blow so hard

It sliced through skull and face, then neck and chest,

And left the Christian dead amidst the rest.

Nor did he linger, swinging his great sword,

Breaking helms and breastplates, far and wide,

Slicing at some man’s brow, his fate assured;

A head, an arm, the sharp blade would divide.

Heart and soul from many a man he clawed,

Heartening the fearful on the pagans’ side,

While the dispirited and fleeing army,

Breaking from their ranks, he sought to rally.

Canto XVI: 75-78: King Agramante attacks the Scots

Into battle rode King Agramante,

Bent on slaying and scattering the foe;

With him Baliverso, Farurante,

Soridano, Prusione, Bambirago,

And other, nameless, soldiers, full many

Whose blood, ere that long day was done, would flow,

To form a lake; one could, with greater ease,

Number the leaves, shed by the autumn trees.

Agramante removed a company

Led by the King of Fez, from neath the wall,

And commanded that host, there and then,

To issue beyond the camp, and forestall

A charge by the Irish cavalrymen;

They were, it would appear, set to fall

On the tents from behind, for they had made

A wide arc, all their banners there displayed.

The King of Fez soon obeyed the order,

Lest delay impair the action in hand;

While Agramante drew his men together,

And, parting company, took his command

Towards the river, thinking to cover

His left flank, as events did now demand,

For a courier, a terse request had made,

(The man sent by Sobrino) seeking aid.

More than half his camp he led to battle,

While the Scotsmen trembled at the sound,

Their dread such that, like a herd of cattle,

In disorder, they abandoned their ground.

Lurcanio, made of finer metal,

And Zerbino reserves of courage found,

As did Ariodante; though Zerbino

Might have died, but was saved by Rinaldo.

Canto XVI: 79-84: Rinaldo unseats Agramante

For that warrior, pursuing, in their flight,

A hundred banners, elsewhere on the field,

Hearing Zerbino’s cry, saw that the knight,

All alone, on foot, would be forced to yield,

For, midst the Africans, dire was his plight,

Abandoned by his men; Rinaldo wheeled,

And, to where the Scots ran from the fray,

Spurring his steed, he swiftly made his way.

He rode among the fleeing troops, and cried:

‘Where, go you? What baseness in you now

Leads you to yield, and quit your leader’s side,

Abandoning all, breaking every vow?

Behold the spoils, destined to hang with pride

On the walls of every church, yet you bow

To lesser men. What praise what glory, here?

Dishonour, and not death, true soldiers fear.’

Then, from a squire, he took a mighty lance.

Prusione, the Alvarrachian king,

He saw nearby, preparing to advance,

And knocked him to the ground, surely dying.

Agricalte, he dispensed with, at a glance

Bambirago, Soridano wounding,

Who would, surely, have breathed no longer,

If Rinaldo’s weapon had proved stronger.

The lance shattering, he drew Fusberta,

And Serpentino of the Star he struck,

Who, protected by its power, as ever,

Still felt the blow; hard was the fall he took.

Then around the Scottish lord, a wider

Space he cleared, while, in a rare stroke of luck,

The duke, on foot, seized a riderless mount,

Then gained the saddle, on his own account.

And well it was, indeed, that he did so,

He might not have won forth, if he’d delayed.

For Agramante, and Dardinello,

Sobrino, Balastro, the ground had made.

Yet he’d mounted, in time, and even though

He was attacked, he wielded his sharp blade,

Sending this or that man down to hell,

That they of this, our life above, might tell.

The good Rinaldo who e’er had regard

To unhorsing the boldest and the best,

With his sharp sword struck Agramante hard,

Who, to his eyes, seemed prouder than the rest,

(He’d fought a thousand battles, sang the bard)

As brave Bayard drove hard against the chest

Of his charger, such that the double blow

Spilled horse and rider to the ground below.

Canto XVI: 85-89: Charlemagne views Rodomonte’s trail of destruction

While, without, in cruel and savage battle,

Hatred, Rage, and Fury, stirred the fight,

Rodomonte, within, those walls did rattle

Of house and shrine, burning left and right,

And slaying the people there, like cattle,

While Charlemagne yet laboured, out of sight.

Edward, and Ariman, he now received,

With the British force; and seemed relieved.

But a squire came to him, with pallid face,

Who scarce could draw his breath, and loudly cried:

‘Oh, my lord, my lord!’ naught else, for a space,

Till he had strength to utter aught beside.

‘The Roman Empire falls, and Christ his grace

Has withdrawn from his people, penned inside.

From the sky, came a devil, free of pity,

To slay us, now Our Lord has left the city.

This Satan (for none other can it be)

Burns the houses, destroys the churches there.

Turn and gaze; those towers of smoke but see;

Huge walls of flame rise high into the air.

But hear those cries of woe and misery,

And trust to what your servant doth declare:

That sole creature, that brings both sword and fire,

Will render this, your city, one vast pyre.’

Like a man who, hearing noise all around,

(Cries, and groans, and alarm bells ringing)

Only grasps the true meaning of the sound

When it touches him, the danger pressing;

Such was Charlemagne, who quickly found

With ear, and eye, those signs of conflict rising.

Sending his finest troops on ahead,

Towards the tumult, and the cries, he sped.

Many a worthy, noble knight was there,

Summoned by the emperor to his side;

He directed their banners to the square,

Where the pagan had slain folk, far and wide;

Heard the cries, viewed the marks of that affair,

Human members, cruel tokens, sadly eyed.

No more: let those return some other time

That, willingly, would hear such things in rhyme.

The End of Canto XVI of ‘Orlando Furioso’