Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XLVI: A Beginning and an Ending

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XLVI: 1-19: Ariosto nears the end of his long voyage

- Canto XLVI: 20-24: Melissa seeks out Leo

- Canto XLVI: 25-28: They find Ruggiero lamenting

- Canto XLVI: 29-32: Leo offers the knight his aid

- Canto XLVI: 33-37: Ruggiero accepts, and offers an explanation

- Canto XLVI: 38-44: Leo foregoes his claim on Bradamante

- Canto XLVI: 45-48: Ruggiero is returned to health

- Canto XLVI: 49-52: The Bulgarian embassy

- Canto XLVI: 53-55: Leo presents the knight who fought the duel with Bradamante

- Canto XLVI: 56-60: Who is revealed as Ruggiero

- Canto XLVI: 61-64: Leo tells of Ruggiero’s deeds and actions

- Canto XLVI: 65-66: Bradamante receives the news

- Canto XLVI: 67-72: Ruggiero accepts the kingship of Bulgaria

- Canto XLVI: 73-77: Preparations are made for the marriage

- Canto XLVI: 78-84: The bridal canopy

- Canto XLVI: 85-97: Its prophetic portrayal of Ippolito d’Este

- Canto XLVI: 98-100: Bradamante and Ruggiero recognise the hero there displayed

- Canto XLVI: 101-106: Rodomonte appears and challenges Ruggiero

- Canto XLVI: 107-110: Who refutes his accusation and accepts the contest

- Canto XLVI: 111-114: Bradamante watches on anxiously

- Canto XLVI: 115-118: The duel begins

- Canto XLVI: 119-123: Rodomonte’s sword is shattered

- Canto XLVI: 124-127: Ruggiero is thrown, and fights on foot

- Canto XLVI: 128-130: The pagan king is weakened by his wounds

- Canto XLVI: 131-134: They wrestle and Ruggiero gains the advantage

- Canto XLVI: 135-140: Ruggiero triumphs, Rodomonte is slain

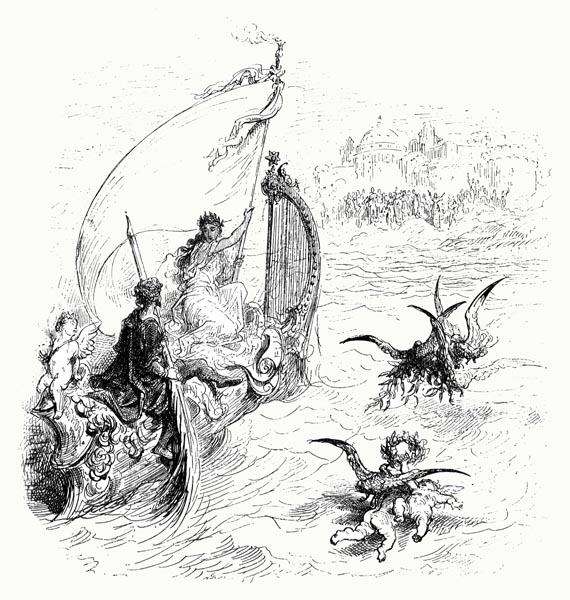

Canto XLVI: 1-19: Ariosto nears the end of his long voyage

Now, if the chart before me speaks true,

Twill not prove long ere I reach harbour,

And so, achieve the promise made to you

Who’ve long escorted me o’er the water,

On which I feared shipwreck might ensue

To my barque, or I might stray forever;

And yet it seems to me, I see the shore,

Tis land indeed, nor shall I wander more.

I seem to hear a burst of joy arise;

It trembles in the air, and skims the wave,

A peal of bells, brave trumpets, joyous cries,

Mingle together, to salute the brave.

Now I begin to see (here ends surmise)

The forms of those whose presence I now crave,

All happy, now my journey’s well-nigh done,

To see the harbour will at last be won.

O, the wise and lovely ladies that I see!

O, the brave knights here that adorn the shore!

O, the friends, to whom an eternity

Of thanks I owe, for this, their joy, and more!

La Mamma and Ginevra welcome me,

They, of Correggio’s House, go before;

Veronica Gambara follows near

To Apollo and the Muses so dear.

Then another Ginevra, of that same tree

A slip, accompanied by Julia;

And Ippolita Sforza, there I see;

Giovanni’s daughter, Trivulzia,

Emilia Pia, Margharita, three

Fair ladies; beside Angela Borgia,

Ricciarda d’Este, Graziosa,

Bianca and Diana, with their sister.

Behold, as wise and chaste as she is fair,

Barbara of the Turchi, beside Laura,

The sun shines not on any kinder pair,

Twixt the Indies and Mauritania.

Behold Ginevra that so gilds the air,

Within the house of Malatesta,

That no more worthy a flame, I’m sure,

Lights the palace of king or emperor.

If she had lived, perchance, in Rimini

When Julius Caesar returned from Gaul,

And by the Rubicon stood, all uneasy,

As to whether upon Rome he should fall,

He’d have lowered his banners, swiftly,

Before her, and set down his trophies all,

Agreed to whatever pact she thought best,

And never have fair Liberty oppressed.

There, the wife of my lord of Bozzolo,

His mother, sisters, and cousins, I see;

They of the Torelli, Bentivoglio,

The Visconte, and Pallavigini.

Behold her on whom all ladies bestow

The palm; of all in Greece, or Barbary,

Of whom fame tells, and those of Italy,

First among all for her grace and beauty,

Julia Gonzaga. Where’er, she goes,

Where’er, she turns her calm and limpid gaze,

Not only must all yield, as to the rose,

In beauty, but a heavenly goddess praise.

And her sister-in-law beside her shows,

That stood firm in her loyalty, always,

Though long ill Fortune worked in her despite;

Tis Anna of Aragon, Vasto’s light:

Anna, noble, lovely, courteous, wise

Temple of love, and truth, and chastity,

Her sister too is with her, who likewise

Gleams so that she dims all other beauty.

See Vittoria, who, in faithful guise,

In spite of all the Fates and Destiny,

Has from the Styx raised up her lord, on high,

To shine in splendour in the glowing sky.

My ladies of Ferrara, they are here,

With those of Urbino’s court; I espy,

Those of Mantua; many now draw near

That Tuscany, and Lombardy supply.

The noble knight beside them, whom tis clear

They honour, if naught deceives my eye,

Dazzled by the splendour of their faces,

Is Accolti, whose light Arezzo graces.

Benedetto, his nephew, there I see,

Adorned with the scarlet cap and mantle;

Campeggio, glory of the Papacy,

And beside him Mantua’s cardinal;

And each of them (or I rave foolishly)

To face and gestures such delight recall,

At my return, no easy task twould seem

So vast an obligation to redeem.

Lactantius, Claudio Tolemei,

Paulo Panza, the Capilupi, lo,

Giovenale Latino, there, I see,

Molza, Sasso, Florian Montino,

With one who the shortest path doth show

To Hesiod’s fount, Giulio Camillo;

And I now discern, it seems to me,

Marco Flaminio, Sanga, and Berni.

See my lord Alessandro Bernini,

‘Phaedra’, Capella, Porzio as ever

‘The Bolognese’, Filippo, Maffei,

Blosio, Piero, Vida of Cremona,

His vein inexhaustible and lofty,

Maddaleni, Latin versifier,

Mussuro, Lascaris, Navagero,

Andrea Marone, and Severo.

Lo! Two more Alessandros I see,

(One of the Orilogi, one Guarino)

Mario d’Olvito, scourge of royalty,

With the divine Piero Aretino;

Two Girolamos (of Veritade

One, and one of the Cittadino),

The Mainardo, the Leoniceno

Pannizato, Celio and Teocreno.

Bernardo Capel, Pietro Bembo

That raised our idiom, both sweet and pure,

Beyond all vulgar usage, and doth show,

By his example, what might lie in store.

Gasparro Obizzi, him doth follow,

Admiring what he bestows, and more.

I see Fracastoro, Bevezzano,

Trifone Gabriel, far-off a Tasso.

Nicolò Tiepoli, Nicolò

Amanio now fix their eyes on me,

While, with wonder, Antonio Fulgoso,

Sees my barque nearing harbour joyfully.

Distant from the ladies, my Valerio,

Is there with Barignano, hopefully

Thinking of how he might evade them all,

And not, as ever, for the nearest, fall.

Of high, nay superhuman wit, there, see,

Tied by love and blood, Pico and Pio.

He that is with them, whom the most worthy

Honour, I’ve never met, but wish to know,

For, by certain tokens, he seems to me

To be that Jacopo Sannazaro

Who’d have the Muses leave their mountain peak,

And dwell beside the shore; tis him I seek.

Behold, that diligent secretary,

Pistophilus, the loyal and learned,

Who, together with the Acciaioli,

And my Angiar, is now contented

To find I need no longer fear the sea.

Annibale Malaguzzo, strides ahead

My kin, with Adoardo, who grants me

Hope I’ll be heard from India to Calpe.

Vittore Fausto, Tancredi, delight

In viewing my sail, with a good five-score

Of men and women, gathered at the sight,

That joy at my return, and crowd the shore.

So, since tis a brief space ere I alight,

And the wind blows fair, I’ll delay no more,

But turn to Melissa, swiftly, and show

How she saved the life of our Ruggiero.

Canto XLVI: 20-24: Melissa seeks out Leo

Melissa, as I’ve oft said, and you know,

Greatly desired that fair Bradamante

Should be tied in marriage to Ruggiero,

And on their weal or woe pondered deeply,

Such that she must ever seek to follow

Their progress, and sought news of them hourly.

To that end, she sent her sprites to and fro;

As one returned, another one would go.

They found Ruggiero a prey to sorrow,

Wandering, midst the shadow of the trees,

Who would not eat a morsel, in his woe,

And sought to die of hunger if you please,

For none was there to stop him doing so.

But soon Melissa would his troubles ease,

Who, issuing forth, had set out that day,

To encounter Prince Leo on the way.

Leo, who’d sent his people, one by one,

To seek him everywhere, and no place scorn,

Had, afterwards, set out himself, in person,

To find that brave Knight of the Unicorn.

The wise enchantress, who that day upon

A steed that cloaked a demon form was borne,

(In a bridled nag she did him confine)

Now came upon that son of Constantine.

‘If your nobility is such,’ she said,

‘As now appears in your outward show;

If true goodness and courtesy were bred

In you, and did on you that face bestow,

Let some comfort, some aid, now be sped

To one who is the bravest knight I know,

Who if he finds not aid and comfort, soon,

Will surely die; I ask of you this boon:

The best of the knights that ever bore,

A shield, or rode with sword at their side;

The fairest and noblest that e’er wore

A helm, of all that live yet, or have died,

Will perish if the courtesy of yore,

Is not readily, to comfort him, supplied.

Come, for the sake of Heaven, sir, and see

If your aid might relieve his misery.’

Canto XLVI: 25-28: They find Ruggiero lamenting

The thought crossed Leo’s mind, most suddenly,

That the knight of whom she spoke was the same

Whom he had sought throughout all that country,

One that, he now perceived, was known to fame.

So that he spurred behind her, furiously,

Who had invoked his mercy; soon they came,

(For neither long nor tedious was the way)

To where, at the gate of death, Ruggiero lay.

He had been three days without sustenance,

And was so overcome, and filled with pain,

He could but walk a pitiful distance,

Unsupported, ere collapsing again.

Girt with sword, helm on head, by his lance

He lay on the ground, where he long had lain,

And of his shield a pillow he had made,

With the white unicorn thereon displayed.

There, musing on the injury he’d done

His lady, how unthinking he had been,

How ungrateful, in his deep affliction

Not grief alone troubled him, unseen,

But he bit his hands and lips in passion,

As the tears ran unchecked down his lean

And hollow cheeks, and gazing fixedly,

Neither Leo nor Melissa did he see,

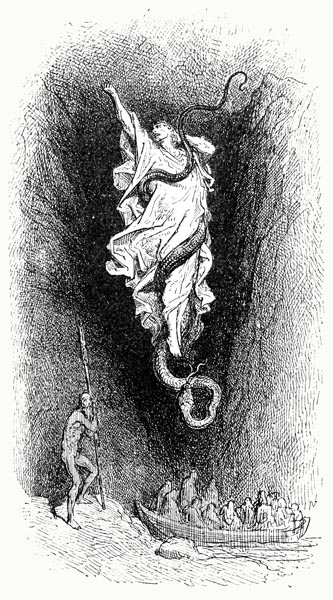

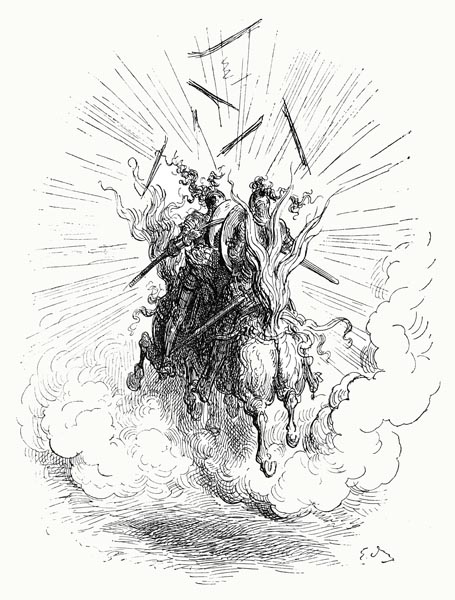

![Ariosto - Orlando Furioso - Canto XLVI: 27 [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Italian/interior_ariosto_orlandofurioso_cantoxlvi27b.jpg)

Or hear, or know, nor left off his lament,

Nor tempered his weeping and his sighing.

Leo halted, upon listening intent,

Dismounted, and to the knight went speeding.

He now knew that true love was the torment

That afflicted him, though still unknowing

Who the lady was that had caused such pain,

For Ruggiero had scarcely made that plain.

Canto XLVI: 29-32: Leo offers the knight his aid

Approaching nearer, and still nearer, he

Looked the unhappy warrior in the face,

And, greeting him with sweet and brotherly

Affection, clasped him in a warm embrace.

I know not if twas pleasing entirely

To Ruggiero, his presence in that place,

Who greatly feared disturbance and annoy,

And that some argument he’d now employ.

But Leo, with the gentlest and sweetest

Of speeches, sought his warmest love to show,

‘Let it not pain your heart, to be confessed’

He said, ‘of the trouble that afflicts you so;

Few are the evils with which we’re oppressed

That deny us some escape from our woe

If the cause be known, nor is there such strife

As bars all hope, so long as there is life.

It grieves me that you’d hide yourself from me,

Whom you know for a faithful friend and true,

Not only am I bound to you, wholly,

Such that the knot no mortal could undo,

But I have been so since I’d cause to be

Your foe, when your worth I scarcely knew.

Know then, that I am here to bring you aid,

Friendship, and life, and see your ills allayed.

Scorn not to share your pain and your sorrow,

Let us find if strength, or wealth, may avail;

Art, or skill, or mere affection thus bestow

Some amendment; if not, and all must fail,

Then Death alone may serve to end your woe,

And his dark chariot then, you may hail;

Yet, take the better course, seek not to die

First, let what can be done be done, say I.

Canto XLVI: 33-37: Ruggiero accepts, and offers an explanation

He followed this with such a fervent plea,

So benign was his speech, and so humane,

That Ruggiero was forced to yield, sadly,

Whose heart was not of stone nor steel, tis plain.

He deemed that if he, discourteously,

Denied him a reply, failed to explain,

The deed was ill; but twice or thrice he tried

To speak, ere his thoughts he could confide.

‘My lord,’ he said, at last, ‘when I supply

My name to you (for I shall tell you all)

I think you’ll be no less content than I

To wish for me to pass beyond recall.

For, know, I am the one you wished might die,

Ruggiero, whom you hated, you’ll recall,

As I once hated you; and so, from court,

I rode to seek you, for your death I sought,

Since I’d not see you wed Bradamante,

Knowing her father was inclined to you.

And yet though man proposes, as we see

Tis God disposes, for my blinkered view,

Was changed by your display of courtesy,

In my great need; my eyes were oped anew;

I renounced the hatred I had felt before,

And pledged to serve your cause for evermore.

Not knowing I was that same Ruggiero,

You begged me to help you win the lady,

Nor was that otherwise, you must know,

Than to tear the heart and soul from out me.

Whether I served your wish, by doing so,

Or my own, you have thus been made to see.

She is your fate; marry her now in peace,

More than my own, I wish for your increase.

Be content if, deprived of her I love,

I would deprive myself of life also;

Sooner would I my beating heart remove

Than live on, without Bradamante, so;

And ne’er, while I amongst the living move,

Can you legitimately have her; know,

That twixt us pledge was made, and vows were said,

Nor can she, if I live, two husbands wed.’

Canto XLVI: 38-44: Leo foregoes his claim on Bradamante

This speech of his did Leo so amaze,

On finding that this was Ruggiero,

That, struck dumb, he could only stand and gaze,

Unmoving as a statue, and naught did show;

A mere statue, like those devout folk raise

To fulfil a vow: that one should forego

Their love, for a rival, seemed so rare

A courtesy, naught else was e’er so fair.

He felt not only had the great goodwill,

He had borne towards Ruggiero before,

Abated not, but it had waxed, until

He suffered with the other, if not more.

For which reason, and to show that he still

Was the true son of a great emperor,

Though in aught else he must concede the field

To Ruggiero, in courtesy he’d not yield.

He cried: ‘Upon that day, Ruggiero,

When my host was routed by your valour,

Though I loathed my rival, yet, even so,

If I had known that you were that other,

As I do now, had known you were that foe,

I still would have loved you as a brother;

For that same valour would have swiftly chased

All hatred from me, by this love replaced.

That I hated the name of ‘Ruggiero’

Before I came to know you were that same,

I’ll not deny; but think not I would so

Mar our true friendship now; but rather claim,

That had I known the truth, as I now know,

On freeing you from that vile place of shame,

I would have done for you, then, what I will

For your benefit, do now, and love you still.

And if I’d willingly have done so then,

When I was not, as now, in debt to you,

I would prove the most ungrateful of men

If thus indebted I fail so to do,

When you deny yourself fulfilment; when

You grant that to me which to you is due.

But I restore the gift, one I believe

I’m as content to give as to receive.

She is more suited to yourself than me;

Though I love her for her worth, yet tis true

I’d not sever the thread prematurely

If another wed her, as you seek to do.

Nor would I ever wish your death to be,

A valid reason to seek her anew,

(Scorning the bond by which to you she’s tied)

And thereby gain her as my lawful bride.

I would rather not only lose the lady,

But life itself, with all that I possess,

Than know that it is on account of me

That such a knight should suffer such distress.

Thus, your diffidence grieves me, utterly,

(Who can, indeed, count on me no less

Than on yourself) when you would rather die

Than accept my aid, and be saved thereby.’

Canto XLVI: 45-48: Ruggiero is returned to health

And with these words many more he proffered,

Which it would take too long to utter here,

That refuted every argument offered

As to why he should not so interfere.

At last, the knight, in yielding, answered

‘Then I am content to live, and yet, I fear

That I can ne’er requite the debt I owe

To one that twice has delivered me so.’

Melissa had nourishing food, and wine,

Brought there, and in a trice was obeyed,

And comforted the knight, and made him dine,

That might well have perished without such aid.

Meanwhile Frontino, perchance by her design,

Had appeared and for his master had made,

Whom Leo’s squires caught, at his command,

And saddled, and then tethered near at hand.

Ruggiero mounted, with difficulty,

Despite Leo’s aid, upon the courser,

So feeble was his strength, although he

But a few days before, in full armour,

Had overthrown swathes of the enemy,

And in doing so never lacked for vigour.

Departing, within half a league, they saw

A nearby abbey, and soon reached its door.

There they chose to stay until the morn,

Then spent another day, and another,

Resting, till the Knight of the Unicorn

Had been granted full time to recover.

Then Ruggiero, less weary and careworn,

Returned to court, with Leo and Melissa;

Where was found a Bulgarian embassy

That had brought a message from that country.

Canto XLVI: 49-52: The Bulgarian embassy

Their nation, who sought him as their king,

Wishing him to return, had sent them there,

To France and Charlemagne’s court, believing

They might find Ruggiero, and then swear

Allegiance to him, their kingdom granting;

Such was the plea the embassy did bear.

His squire who had met with the embassy

Had spread their news of the knight widely:

The squire had told of the battle he’d won,

For the Bulgars, on the field of Belgrade,

How Leo’s and his sire’s host was undone,

And their people slain, or sore dismayed,

And how the Bulgars now, as a nation,

Wished Ruggiero as king, and so prayed;

And how, at Novigrad, Ungiardo

Having taken him captive did bestow

Ruggiero on the cruel Theodora;

And then of how the gaoler was found dead,

And the utter absence of the prisoner;

No more did the Bulgars know, or had said.

Ruggiero, unseen, and under cover

Of a secret path, to lodgings, was led,

And next morn, accompanied by Leo,

To King Charlemagne’s court, the pair did go.

He presented himself neath the banner

Of the gold two-headed eagle on its field

Of crimson, and he wore, o’er his armour,

A surcoat with those arms; so too his shield

Bore the like; all was the same moreover,

Though damaged, as before had been revealed;

Thus, presenting himself as, by this show,

Him who’d fought Bradamante as her foe.

Canto XLVI: 53-55: Leo presents the knight who fought the duel with Bradamante

In rich vestments, and adorned regally,

Leo, unarmed, approached beside the knight,

And before, and behind him, came a worthy

Flock of noble companions; when in sight

Of Charlemagne he bowed (he, graciously

Had risen to honour him, as was right);

Then Leo took the cavalier by the hand,

As they all watching eyes did, thus, command.

‘Behold the champion who did maintain,

From the dawn of day to day’s end, the fight,

And by Bradamante was nor taken, nor slain,

Nor was driven from the lists; this the knight

Generous sire, whose victory was plain,

If we, here, have read your decree aright,

Who thus has won the right to wed the lady,

And comes here, to be granted her wholly.

Besides the fact that, by that same decree,

You can grant to no other man that same,

He has merited her by his valour, surely;

What more worthy husband could one name?

And if the one who loves her best, should be

The one to have her, none has better claim

Than this knight, who will fight against all foes

That would his right to marry her oppose.’

Canto XLVI: 56-60: Who is revealed as Ruggiero

Charlemagne, and all his court, were stupefied,

For they’d believed that Leo was the warrior

Who his sword gainst Bradamante had plied,

And not the unknown knight that they now saw.

Marfisa who had heard, and fiercely eyed,

The knight, could scarcely wait to hear more,

And almost before Leo finished speaking

She stood forth boldly, and addressed the king.

‘Since Ruggiero is not here, to contest

His prior claim and meet this unknown knight;

And lest she, without sufficient protest,

Is borne away from the palace, outright;

I, as his sister, make this just request,

That I, on his behalf, may face in fight

Whoever claims a right to Bradamante,

Or that he, of the maid, is more worthy.’

She spoke with such great anger and disdain

In expressing this plea, that many there,

Thought that, without leave from Charlemagne,

She would slay the knight, and end the affair.

It seeming to Leo foolish to maintain

The disguise, Ruggiero’s head he did bare,

And called out to her: ‘He is ready now

To render his account to you, I’ll vow.’

As old Aegeus looked, when he perceived

At the accursed feast that, from Medea,

Twas Theseus his son who had received

The poisoned cup she had readied earlier,

The son he might have killed, he believed,

If, by the sword, he’d not known its bearer,

So Marfisa looked when she saw the foe

That she hated, was her Ruggiero!

She clasped him, in a trice, in her embrace,

Nor from his neck would she her arms unwind.

Orlando, Rinaldo, the king, did grace

His bare brow with kisses, loving and kind,

Oliviero too thus laved his hands and face,

Dudon and Sobrino close behind.

Nor did paladin nor lord grow weary

Of welcoming a warrior so worthy.

Canto XLVI: 61-64: Leo tells of Ruggiero’s deeds and actions

Leo, that was possessed of eloquence,

Once they had ceased embracing the knight,

Related before all that audience

(Addressing Charlemagne) how the might

Of the warrior, his skill, martial presence,

And bravery, at Belgrade, midst the fight,

Had outweighed, although he fought for the foe,

For him, the harm that was inflicted so;

Such that when consigned to Theodora

(Who was set to torment him, cruelly)

He, had chosen to save the prisoner,

Despite his aunt, and all his family;

And how this Ruggiero had, thereafter,

Repaid his deed with such high chivalry,

With such noble courtesy, that by none

Had he been, or could ever be, outdone.

And then, point by point, he narrated

How Ruggiero had served him graciously,

And how, later, believing himself fated,

In his grief at the loss of his lady,

To die, had then starved himself; and stated

How the knight had been aided, in timely

Fashion; and expressed himself so sweetly,

That all were consumed by tears, completely.

Then he addressed such efficacious pleas

To the stubborn and prejudiced Amone,

That he not only swayed him, by degrees,

Till his will matched that of Bradamante,

But persuaded that proud lord, on his knees,

To beg forgiveness of the knight, and swiftly

Receive him as his son and son-in-law,

To be bound to Bradamante evermore.

Canto XLVI: 65-66: Bradamante receives the news

To whom the news was brought where she lay,

(Her life in doubt) weeping, in her chamber,

With happy cries, as they sped on their way,

By many a breathless, joyful, messenger;

So that the blood that, from the very day

She was first afflicted, had sought to gather

Round her stricken heart, rose in such a tide

Of sudden joy the lady well-nigh died;

The maid was so depleted of vigour,

That she could barely stand, yet you ought

To know the strength of spirit within her,

The power of will that to all things she brought.

None dragged to the block, the wheel, the halter,

Or condemned to other death by some court,

And about whose head the black cloth is tied,

Was e’er happier to hear their pardon cried.

Canto XLVI: 67-72: Ruggiero accepts the kingship of Bulgaria

Chiaramonte’s and Mongrana’s Houses joyed

To twine again their kindred branches so;

The Maganzeses, Gano, Gini, were annoyed,

Ginami, Falcone, Count Anselmo,

Though a suitable front these all employed

Their dark and envious feelings not to show,

Yet waited on the time of vengeance, there,

As the fox at the gate awaits the hare;

For they loathed Orlando and Rinaldo;

Both had slain many of that wicked clan.

Though curbed by fighting gainst the common foe,

And by the king’s wise counsel, to a man

They’d been stirred by the deaths of Pinabello,

And Bertolagi; vengeance was their plan.

Yet naught of their feelings they revealed,

Whilst the truth of those deaths they yet concealed.

The Bulgarians who’d arrived at the court

Of Charlemagne hoped (as I have said)

To find the knight who at their side had fought,

(His, the white unicorn on a field of red);

To crown the knight as their king they sought.

Praising their good fortune, with bowed head,

They fell at his feet, on finding him there;

‘Return, sire, to Bulgaria,’ their prayer;

For, in Adrianople, he’d receive

The royal crown, and the jewelled sceptre.

Let him but come, and their folk would believe

They’d be protected by his fame and power;

For Constantine fresh plans did now conceive,

To war in person, and so seize the hour,

While they, with their new king, might aspire

To wrest from him the Eastern Empire.

Ruggiero accepted, won by their plea,

And promised to return to Bulgaria,

Within three months, if Fortune was truly

Kind to them all, or even earlier.

Leo, hearing this, addressed him, promptly,

Asking the warrior to trust him further,

For, once Ruggiero was crowned, he’d seek

To make peace twixt Bulgarian and Greek;

Nor need he depart from France so soon,

To lead his army and defend his land,

For he’d persuade his father, as a boon,

To return those strongholds he did command.

Of the virtues (to which she’d seemed immune)

Possessed by Ruggiero, you’ll understand,

None so endeared Bradamante’s mother

To him, as his rise to wealth and power.

Canto XLVI: 73-77: Preparations are made for the marriage

Rich and royal nuptials they prepared,

To him who undertook them most fitting,

For Charlemagne in all that pleasure shared,

As if it was his own daughter’s wedding.

Such was the promised bride for whom he cared,

Such the merits of her House and following,

The king thought naught too great a measure,

Though it cost him half his kingdom’s treasure.

Open court was declared to one and all,

And safe welcome to all he did extend,

And whoever the delights of joust did call

To arms there, till the ninth day, might contend.

With leaves and branches he decked every hall,

None e’er as fair, on that you may depend;

In the gardens, too, they wrought sweet bowers,

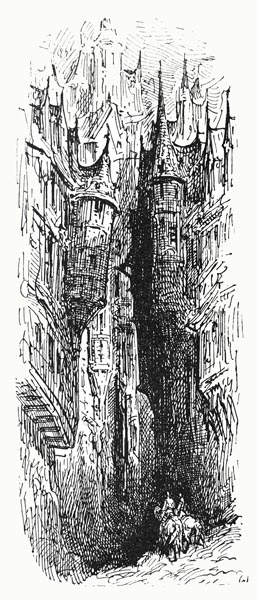

Rich with silk and gold, adorned with flowers.

All Paris was not able to contain

The many guests that now sought lodging there.

Rich and poor, of every quality and strain,

Greeks, Latins, foreigners both strange and rare,

No end of folk from every far domain,

Noblemen, embassies, sought that affair;

But all were found fair shelter, new created,

In huts, tents or booths accommodated.

Melissa had, against the wedding night,

Decked out a marriage chamber for the pair,

Filled with finest adornments, fair and bright,

That had taken long hours to so prepare.

For many a year she had, with second sight,

Anticipated their sweet coupling there,

Since, in foreseeing the future, she knew

That their stem would bear a fruitful issue.

She had there arranged a welcoming bed,

Beneath a broad and spacious canopy,

None richer, more ornate was ever spread

In war or peace, nor one more lovely,

For to Thracian shores the wise mage had sped,

And from thence she had conveyed it, swiftly.

That costly thing she took from Constantine,

That in his realm did sport, beside the brine.

Canto XLVI: 78-84: The bridal canopy

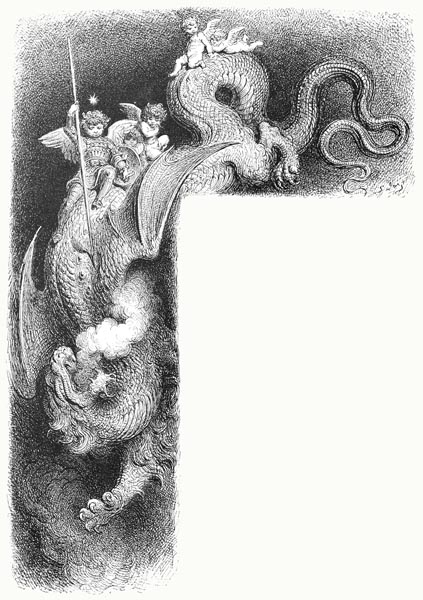

Melissa, with the knowledge of Leo,

And the better to provoke his wonder,

A fine example of her art, would show,

Who could draw Hell’s great serpent to her,

And rule him and all his, sunk deep below,

All that brood, God’s enemies forever;

Thus, to Paris, she’d made tamed demons bear

It, from Constantinople, through the air.

Constantine lay beneath it, who held sway

Over the Eastern Empire; when the sun

Had reached the zenith, they whisked it away,

With its cords, and poles, and curtains every one,

And, flying through the sky thus, at mid-day

Brought it, to roof the bed; the first night done,

They turned about, a like course did maintain,

And, magically, bore it back again.

Two thousand years before, that canopy

Had been woven, and in such rich fashion,

Created, midst the heat of prophecy,

By a maid of Troy, and wrought with passion.

Her hands had laboured with care and study,

To embroider the whole, and that Trojan

Prophetess was Cassandra who to brave

Hector, her brother, that fair gift conveyed.

The noblest knight that would, in time, arise

From out that brother’s stock, she portrayed

(Far distant from that root, neath other skies,

With many a branch betwixt ere he be made)

With her own hand, his form did realise,

In varied silks, and rich gold thread, displayed.

While he lived Hector prized it greatly,

For the work therein, and the learned lady.

But when Troy’s great champion lay dead,

And the Greeks yet laid siege to the city;

When false Sinon the citizens misled,

And greater ill was done than told in story,

It passed through Menelaus’ hands instead,

And to Egypt went with him, its destiny

To be granted Proteus, Egypt’s great lord,

When that king, to him, fair Helen restored,

Whom he had taken captive; to free her

The Greek gave, in ransom, this canopy,

In time inherited by Cleopatra,

An heirloom of the House of Ptolemy,

To be seized by Agrippa’s navy later,

At Actium, midst the Leucadian Sea;

To Octavian, then Tiberius it came,

Held in Rome, till Constantine laid claim;

Constantine the Great, whose reign you’ll rue,

Fair Italy, while the heavens turn, for he

When wearied of the Tiber built anew;

To his Byzantium went the canopy.

To Melissa, from his namesake, now it flew,

Its cords of gold, its poles of ivory,

Its cloth with lovely figures overlaid,

Far fairer than Apelles’ brush ere made.

Canto XLVI: 85-97: Its prophetic portrayal of Ippolito d’Este

Upon it, the Graces, in sweet attire,

Were portrayed aiding the delivery

Of a noble son; none finer an entire

Four ages of this world could ever see.

There Venus, Mars and Jove, stood to admire

The child, beside eloquent Mercury,

And scattered, o’er him, heavenly showers

Of ethereal, ambrosial flowers.

‘Ippolito’, inscribed there, could be read,

On his garment, in minute lettering.

There (older now) by Fortune he was led

Tight by the hand, with Virtue preceding.

Next in long robes, with dangling locks outspread,

Came those of King Corvinus’ following,

Requesting the young child leave his father,

For Hungary, to be ordained with honour;

Parting respectfully from Ercole,

He was seen, and Eleanor, his mother;

Then, beside the Danube, being widely

Adored, with a near-religious fervour,

There where the prudent king of Hungary

To his ripening knowledge did great honour,

And, given the child’s tender unripe years,

Esteemed him above all his lords and peers.

Next, while still a child, he was portrayed,

With Esztergom’s crozier in his hand;

Then with the king at court, and on parade,

And next, afield, as the troops, on command,

Gainst Turks, gainst Germans, some venture made,

Where the king was shown leading his brave band,

Ippolito there (midst the canopy)

Gaining virtue, watching attentively.

Then he, in the flower of youth, was shown

His time spent midst the arts, or studying;

With our Tommaso Fusco both well-known

And hidden thoughts of past times revealing.

‘Shun this,’ he seemed to say, ‘mark this alone,

If you’d achieve things worth remembering.’

On the canopy those scenes were displayed,

Where every gesture its maker had portrayed.

Then, as a cardinal, his form was viewed

Still young, in council at the Vatican,

With eloquence and intellect imbued,

Such as to stun the conclave to a man.

‘What will he become, this but a prelude?’

(They seemed to say, amidst the fabric’s plan)

‘Were Peter’s mantle to grace such as he,

How blessed the age, how fair our century!’

Elsewhere his liberal pleasures met the sight,

His youthful sports; as on some Alpine steep

He faced a bear, or, neath the mountain height,

Chased wild-boar, along some marshy deep;

Now, on his jennet, like the wind in flight,

Chasing a goat or deer, some stream to leap,

The quarry falling on the dusty sward,

Near sliced in two by his descending sword.

Next, he was seen amidst a fine array

Of poets and philosophers; one there

Charted the planets on their wandering way,

Others Heaven’s secrets and Earth’s laid bare,

Chanted sad elegies, joyful verse, a lay,

Heard graceful odes, or dined on epic fare.

He was shown listening, in another place,

To sweet music, and dancing with true grace.

Upon the first part of that canopy

Was portrayed the youth of this noble lord.

Cassandra had woven there, equally,

Acts of justice, prudence, the brave sword,

True modesty, and generosity

The fifth virtue that goes with them abroad,

The virtue that dictates we give, and spend,

And lights the rest, the other virtues’ friend.

In the next, the princely youth was portrayed

With the unhappy duke, midst his Insubri;

Seated in counsel with that lord, displayed,

And then, both armed, neath the Biscione,

Bound by a loyalty that could not fade,

Through happy times, and days of misery;

Following him in flight; in affliction

His comfort, in danger his companion.

Elsewhere he was seen, now deep in thought,

Fearing for Ferrara, and Alfonso,

Who for proof of treachery had sought,

Such found, and shown to wise Ippolito,

The plot forged by their closest kin, at court,

By two he had held most dear; shown also

His receiving the title, long ago

Bestowed by a free Rome on Cicero.

Again, he was seen in gleaming armour,

Hastening to aid Holy Church, his force

Inadequate, and prone to disorder,

Opposing an experienced counter-force,

Yet his sole presence brought such succour,

To those ecclesiastics, that, in due course,

The fire was extinguished ere it spread;

‘Veni, vidi, vici,’ it might be said.

And, at last, was shown, from his native shore,

Fighting a mightier fleet than those sent,

By Venice, against Turks and Greeks before;

And then, once he had conquered it, and sent,

To his brother, spoils and captives, and more,

Was portrayed as, still, upon honour bent,

The sole prize that he could not give away,

But must retain himself, from that great day.

Canto XLVI: 98-100: Bradamante and Ruggiero recognise the hero there displayed

The knight and ladies viewed that canopy,

Yet could give no meaning to the tale told,

Since there was none to gloss the prophecy,

Nor that story of things to come unfold.

They took pleasure, simply, in its beauty,

And read the texts; twas like some myth of old.

But Bradamante, taught by Melissa,

Silently rejoiced; she viewed the future;

And Ruggiero as well, though not so taught

Unlike Bradamante, now recalled to mind

How Atlante had their descendants sought

To name, and had this prince’s deeds outlined.

What shall I say of Charlemagne’s fair court;

How tell of every courtesy, there designed?

Of the festive scenes and games, all applaud;

Of the food and drink, weighing down the board?

Knights jousted to test each other’s valour,

And broke a thousand lances every day,

As, on foot or horseback, they sought honour,

In single combat, or in mixed affray.

Ruggiero shone beyond any other,

Who always conquered, be it night or day.

In fighting, wrestling, dancing, his, the prize;

He the foremost there, in all others’ eyes.

Canto XLVI: 101-106: Rodomonte appears and challenges Ruggiero

On the last day, when the sober company

Were seated, to begin their sumptuous feast,

With Ruggiero on the left, and Bradamante

On Charlemagne’s right, ere the noise increased,

From the fields beyond, there entered, swiftly,

An armed knight, in stature not of the least,

Of proud semblance, and all his courser’s back,

And flanks were, like himself, clad all in black.

Twas the bold King of Algiers, Rodomonte,

Who had sworn, when from the bridge he fell,

And suffered there such scorn from the lady,

Not to bear arms, or draw sword, for a spell.

A year, a month, and a day, silently,

He’d spent, like some monk in his humble cell;

As, to punish themselves, in former times,

Such knights would do, as penance for their crimes.

He had heard, in those months, of Agramante,

And the successes of King Charlemagne,

But not to forswear himself, kept wholly

From the war, and strict silence did maintain.

But when the year and the month had (slowly)

Passed, and then the day, he had armed again,

And with new armour, courser, sword and lance,

Had journeyed, thus, to the court of France.

Without dismounting, or bowing his head,

With not a single sign of reverence,

He showed the scorn that e’er in him was bred,

Of this king and his lords, his pride immense.

Astounded, to a wondering silence wed,

The rest were amazed at such bold licence.

They ceased their feast, and all conversation,

And gazed at the knight, in consternation.

Then to Charlemagne, and Ruggiero,

With a voice that was loud, and full of pride,

‘Rodomonte of Sarza, and your foe,

Am I, and here I challenge you,’ he cried,

‘You Ruggiero, ere the sun shall go,

That, disloyal to your lord, your aid denied,

That, as a traitor to Agramante,

Of this company have proved unworthy.

And, though your felony is plain to all,

Which you, now a Christian, cannot deny,

To proclaim it clearly, here, on you, I call

To show yourself upon the field, and die;

Or if to another such response must fall,

If one will fight for you, or two, say I,

Or three, or more, I’ll deal with them instead

And maintain, thereby, all that I have said.’

Canto XLVI: 107-110: Who refutes his accusation and accepts the contest

Ruggiero, at his words, leapt to his feet,

And, with licence from the king, he replied.

That if the knight, if all the world complete,

Declared that he was a traitor, then they lied;

That he had served, in victory and defeat,

His lord in a blameless manner, and with pride;

And was prepared in battle to maintain

That he had done so, before Charlemagne.

And that he would himself defend his cause,

No need had he for help from another,

Indeed, he hoped (and here he made a pause)

To show that but one his strength would master.

Orlando and Rinaldo, to such wars

Ever drawn, and Dudon sought to offer,

With Marfisa and Oliviero,

And his two sons, to replace him though;

All arguing that, as one newly-wed,

He should refuse to contend in person.

Ruggiero answered: ‘Let no more be said;

Such I dismiss, tis no valid reason.’

Those arms, once the Tartar’s, he, instead,

Took up, thus ending the conversation.

With spurs Orlando decked the youthful lord,

While Charlemagne attended to his sword.

Bradamante and Marfisa encased

Him in the breastplate; the rest did follow.

Astolfo led his mount, that nobly paced.

Dudon held the stirrup, while Rinaldo

And Duke Namus, the eager crowd now chased

From the lists, helped by Oliviero;

The lists maintained there in case of need.

And now Ruggiero leapt upon his steed.

Canto XLVI: 111-114: Bradamante watches on anxiously

The ladies, the maidens, their faces pale,

Fluttered like doves, round the lists, timidly,

Fearful doves, driven by the wind and hail

From the pleasant field, trembling, anxiously,

Lest lightning and peals of thunder prevail,

As the sky turns threatening, doves prone to flee;

Troubled for Ruggiero, they gazed, in fright,

He seemingly ill-matched with this fierce knight.

So, the crowd thought; so, the majority

Of the lords and knights now gathered there,

Whose minds dwelt on all that Rodomonte

Had wrought in Paris, in that late affair,

When, unsupported, with fire and sword, he

Had laid a large part of the city bare,

Leaving the marks of a disaster more

Complete than any it had known before.

Bradamante’s heart was disturbed the most;

Not that she believed the Saracen king

Could of a greater strength or valour boast;

True valour; than Ruggiero, nor deeming

His, the better cause (which, despite a host

Of troubles, may greater courage bring)

Nonetheless she was not quite free of doubt.

Fear stirred the courage love is ne’er without;

Oh, how willingly she would have lifted

From him the burden of that perilous fight,

E’en if she could do naught but join the dead

As seemed certain, facing the pagan knight.

For more than one death she’d die, in his stead,

Were such possible, embracing death outright,

Rather than suffer him she loved to meet

With mortal peril; dreading his defeat.

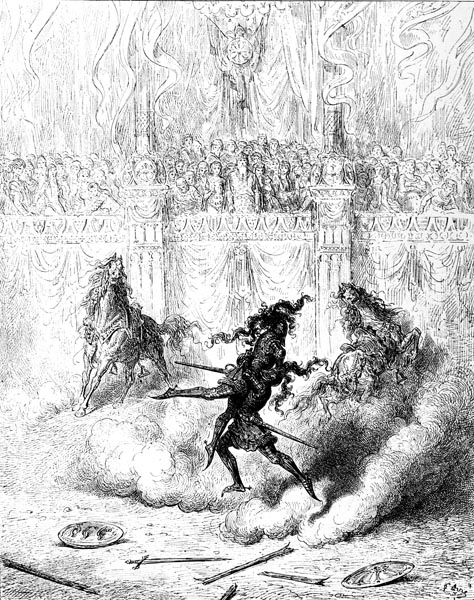

Canto XLVI: 115-118: The duel begins

It had proved of no avail that she’d prayed

Ruggiero to yield her the encounter;

With sad face and beating heart, sore afraid,

She must gaze on as he spurred on his courser.

To right and left, the pair their lances weighed,

And, lowering the steel, charged at each other.

Like ice the lances shattered, and on high

A host of splinters flew towards the sky.

Rodomonte’s lance struck against the shield,

And did but little harm to Ruggiero,

For Hector’s armour its great strength revealed,

Wrought by Vulcan, undamaged by the blow.

His own lance forced the other’s targe to yield,

And passed through the heart of it (although

It was clad with steel, solid bone within,

And a palm’s width thick) as if twere but tin.

And had his lance not broken at the blow,

Thus, failing him at the first encounter,

Shattering to splinters, that ascended so,

They rained down again, a savage shower,

The lance would have pierced his pagan foe,

Though adamantine had been his armour,

And ended the fight; but breaking withal,

Both coursers reared, and then were seen to fall.

With spur and bridle, the knights, instantly,

Forced their steeds to rise, swiftly, from the ground,

Then they, their spears now shattered, turned, fiercely,

To their swords, as fresh ardour both men found.

Their blades struck here and there, remorselessly,

As that pair swung their two coursers around,

Feeling the steel’s keen edge begin to bite,

Probing where’er the plate seemed thin and light.

Canto XLVI: 119-123: Rodomonte’s sword is shattered

Rodomonte lacked that solid serpent’s-hide

That had armoured his chest previously,

Nor was it Nimrod’s sword he now applied

To the other, nor the helm that which he

Once used to wear, for on the losing side

Was he, at the bridge, gainst Bradamante,

And in the chapel was that armour left,

(As I have said) of which, he was bereft.

The king was clad in other plate and mail,

Yet less strong than was the first was the steel,

Though neither those nor finer could avail

Gainst Balisarda whose force all must feel.

All enchantment, all armour could but fail

Struck by the blade that such strokes did deal.

Ruggiero laboured to make each blow tell

That upon the pagan’s helm and breast now fell.

When the king saw the blood begin to flow

From out his armour, unable to escape

The fearful impact of fierce blow on blow,

That pierced and cut him, till the flesh did gape,

A greater fury through his mind did flow,

Than a wintry sea’s that the storm-clouds drape.

He flung down his shield, grasped outright

Ruggiero’s helm, and beat with all his might.

With the extreme force which that machine,

Set on two barges in the River Po,

Raised by both wheels and human strength, I’ve seen

Apply to the tough sharpened piles below,

He beat upon Ruggiero’s helm, with spleen,

As each hand dealt many a might blow.

The enchanted helm stood firm, even then,

Or man and steed had fallen once again.

Twice Ruggiero seemed to bow his head,

Arms and legs slack, as if about to fall,

While the Saracen, longing to see him dead,

Smote again ere his wits he could recall,

Using his sword’s pommel, but instead

Of him maiming, the steel broke with its fall,

Flew to pieces, leaving Rodomonte

Bereft of the blade, his hand nigh empty.

Canto XLVI: 124-127: Ruggiero is thrown, and fights on foot

Rodomonte ceased not from the attack,

But swooped upon the dazed Ruggiero

(His brains so rattled he his wits did lack,

His mind bemused, swaying to and fro).

The pagan king now had him on the rack,

Who, waking him from sleep, his strength did show,

Grasping him, by the neck, with such force

Our hero fell to earth, dragged from his horse.

Nonetheless, Ruggiero rose from the ground,

Filled more by vengeful anger than shame,

For Bradamante’s anxious gaze he found

Amidst the crowd; sore troubled was that same,

Doubtful his fall had left him safe and sound,

And feeling her heart pounding in its frame.

Ruggiero hastening to avoid dishonour

Grasped his sword, and sped towards the other.

He rode at Ruggiero who, warily,

Side-stepped, to escape the sudden blow,

But, as he did, he grasped the bridle, cleanly,

And, with his left hand, thus turned his foe,

While, with his right he struck at his belly

And flank to wound him, striking from below,

Such that Rodomonte, as he passed by,

Was pierced once in the side, once in the thigh.

Rodomonte, still clasping in his hand

The hilt and pommel of his shattered blade,

A blow upon Ruggiero’s helm did land,

Whom another such might have sore dismayed.

But he, who the better cause did command,

Seized his arm and, as Rodomonte swayed,

Using both hands, a firmer purchase found,

And dragged him from the saddle to the ground.

Canto XLVI: 128-130: The pagan king is weakened by his wounds

Through strength, or skill, the pagan so fell

That he was yet a match for Ruggiero.

He landed on his feet, and thus twas well

That the latter had his sword, and not the foe.

With the blade, our hero sought to compel

Rodomonte to retreat, yet even so

Was fearful of the power of that knight,

His height and bulk a threat in any fight.

He could see that he bled from flank and thigh,

And many another wound, here and there,

And hoped he might so weaken, by and by,

That he himself could end the dread affair.

Yet that hilt, that pommel, falling from the sky,

Smote hard, pained and bruised him everywhere.

Rodomonte’s blows such weight and power bore,

They stunned him, as he’d ne’er been stunned before.

On the cheek of his helm, on his shoulder,

Ruggiero was struck, and felt each blow;

He could scarcely keep his wits together,

As he faltered, and staggered to and fro,

Rodomonte sought to close with the other,

But his legs failed him, being weakened so,

(His wounded thigh caused this impotence)

And he fell to his knees, offering no defence.

Canto XLVI: 131-134: They wrestle and Ruggiero gains the advantage

Ruggiero lost no time, striking fiercely

With his sword at the pagan’s face and chest.

Hammered at him, then gripped him tightly,

To drag him to the ground, he thought best.

But the king rose again, clasped him closely,

Such that the pair were locked, breast to breast,

They shifted their holds, grasped, and heaved

Adding art to their moves, yet naught achieved.

His wounded thigh and his raw, gaping side,

Had drained much of Rodomonte’s vigour;

Ruggiero, dextrously, fresh force applied,

Being noted, in the ring, for skill and valour.

He felt the advantage did with him abide,

And thus pressed the pagan hard, wherever

His wounds were causing the king most pain,

Such that great drops of blood now fell, like rain.

Filled with fury and spite, Rodomonte

Grasped his foe by the neck and shoulder,

Bent him back and forward, then fiercely

Raised him upwards, ere he could recover,

Dragged him about, and clasped him tightly,

Seeking a throw that might swiftly conquer,

Ruggiero yet working his advantage,

With great skill, while containing his own rage,

Who pressed once more, and altering his hold,

Thrust his left side against the other’s chest,

Clasping tightly; and though the move was bold,

Straining with all his might, gainst arms and breast,

Forced his right leg gainst the knees, and, behold,

From the ground the warrior he did wrest,

And raising him high as he could, he then

Hurled his foe, face upwards, to the earth, again.

Canto XLVI: 135-140: Ruggiero triumphs, Rodomonte is slain

The ground shook at his fall, his head and spine

Nigh compressed, such was the force of the blow;

The ground was bloodied, while a crimson line

Of blood and gore from out each wound did flow,

Ruggiero’s hand in Fortune’s hair did twine,

Yet gripped the throat, lest he rise, of his foe;

He set his knees on his belly, moreover,

Pointing his dagger at the king’s visor.

As sometimes happens as they mine gold ore

In Iberia or Pannonia,

The workings collapse, the props unsure,

And bury those that avarice would murder,

While the spoil that grips them in its claw,

Passage for the spirit scarce doth offer,

No less oppressed lay that warrior

Pressed to the ground by his conqueror.

Ruggiero to his eyes did now present

The tip of the naked blade he’d revealed,

Threatening to slay him, and yet content

To spare Rodomonte if he’d yield;

But the latter, who had rather been rent

Limb from limb than be shamed upon the field,

Who struggled, and sought, with all his vigour,

To pull him down, not one word did utter.

Like a mastiff that beneath a deer-hound lies,

That has its teeth fixed in his throat, firmly,

Who struggles hard, and vainly tries to rise,

His jaws smeared with foam, eyes burning fiercely,

Yet fails to free himself, howe’er he tries,

From one that wins by force not by anger,

So, in vain the monarch strove, pinned below,

To issue from the grasp of Ruggiero.

And he so writhed and twisted that he gained

The freedom of his good right arm, once more,

And with his hand upon his dagger, strained

(For he had drawn the weapon long before)

To wound Ruggiero in the loins, maintained

Some purchase, but the young knight swiftly saw

The error in his choosing to delay

The evil pagan’s end, and not to slay;

For twice, and thrice, he raised his arm on high,

As high as strength and will would yet allow,

And buried the steel, falling from the sky,

In Rodomonte’s dark and dreadful brow.

From the ice-cold flesh, with blasphemous cry,

The indignant spirit fled, to wander, now,

Acheron’s squalid shore, amidst the crowd,

That was, on earth, so haughty and so proud.

The End of Canto XLVI and of Ariosto’s ‘Orlando Furioso’