Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XLV: A Ruggiero's Woes

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XLV: 1-6: Ariosto on the Vagaries of Fortune

- Canto XLV: 7-9: Ruggiero is taken prisoner

- Canto XLV: 10-12: Constantine receives news of his capture

- Canto XLV: 13-18: Theodora seeks vengeance on Ruggiero

- Canto XLV: 19-24: Charlemagne proclaims the contest Bradamante requested

- Canto XLV: 25-30: She has no news of Ruggiero and is in doubt

- Canto XLV: 31-40: She debates with herself and laments

- Canto XLV: 41-47: Leo enters Ruggiero’s prison cell and frees him

- Canto XLV: 48-50: Ruggiero is deemed to have escaped

- Canto XLV: 51-55: Leo decides Ruggiero shall fight Bradamante in his place

- Canto XLV: 56-60: Ruggiero agonises over the matter

- Canto XLV: 61-63: They reach Paris

- Canto XLV: 64-69: Ruggiero prepares for the contest

- Canto XLV: 70-71: Bradamante proves eager to begin

- Canto XLV: 72-77: The fight commences and Ruggiero defends stoutly

- Canto XLV: 78-80: He maintains his stand and thereby wins the fight

- Canto XLV: 81-85: Bradamante must wed Leo, and Ruggiero departs

- Canto XLV: 86-90: His lament

- Canto XLV: 91-94: He seeks some place to end his life

- Canto XLV: 95-102: Bradamante’s lament

- Canto XLV: 103-105: Marfisa addresses Charlemagne

- Canto XLV: 106-111: Duke Amone complains

- Canto XLV: 112-114: Marfisa suggests a further duel between Leo and Ruggiero

- Canto XLV: 115-117: Leo seeks the Knight of the Unicorn

Canto XLV: 1-6: Ariosto on the Vagaries of Fortune

The higher on Fortune’s swift-turning wheel

We see some poor mortal rise, the sooner

We see them fall, their head below their heel,

To lie flat on the ground, their reign over.

Polycrates exemplifies, I feel,

This truth, Croesus, and Dionysus, later,

(Of Syracuse) and others who, in a day,

Fell from the heights of glory to dismay.

To counter that, the lower some folk fall,

The nearer they are to the ground below,

The sooner and faster, rising amidst all,

As the wheel turns, upwards they will go.

Their head upon the block, they yet rise tall,

And the next day they rule the world; tis so;

To Servius, Marius, such days were known,

Ventidius too; Louis in our own;

Louis the Twelfth (of our Alfonso’s son,

Ercole, the father-in-law) who when

Captured at Saint-Aubin, the battle done,

Was nearly slain, yet lived to rise again.

Matthias Corvinus too, was such a one,

He that, not long ago, a throne did gain;

To Louis all France swearing fealty,

Matthias crowned as King of Hungary.

It seems clear, from such examples, that fill

Reams of ancient and modern history,

That ill’s succeeded by good, good by ill,

Glory ends in shame, and shame in glory.

Folk should place no trust, as ever they will,

In land, or riches, or in victory,

Nor yet despair if Fortune runs counter,

For her fickle wheel goes turning ever.

Ruggiero, with that fine victory won

O’er Leo, and his sire, the emperor,

With a confidence now second to none,

Trusting in his good fortune and valour,

Without aid, and nary a companion,

With only his own heart’s burning ardour,

Midst a hundred squadrons, in close array,

Sought the son and the father both to slay.

But Fortune, who never promises aught,

Soon showed him, clearly, how she will raise,

A favourite, then bring them down to naught,

For, now the friend, and now the foe she plays.

The Romanian knight, knowing him, sought

In haste, to work him harm, and not to praise;

He who, in the heat of that dreadful fight,

Had soon turned tail and fled from him in fright.

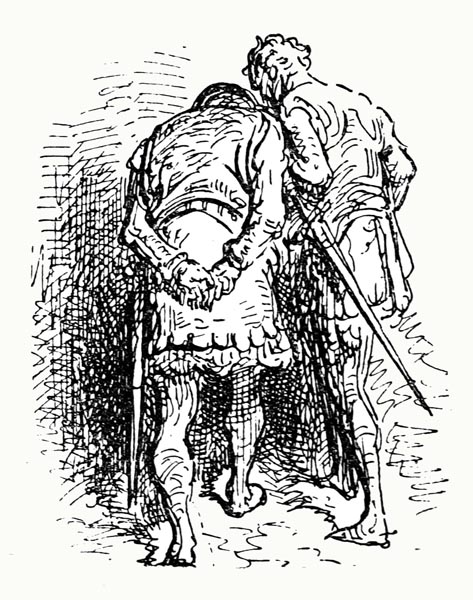

Canto XLV: 7-9: Ruggiero is taken prisoner

He now made known to this Ungiardo

That he who’d put Constantine’s men to flight,

And done so much damage (our Ruggiero)

Was in the city, and slept there that night;

And, if Fortune’s hair was grasped, even so

He could be taken there, without a fight;

And if he imprisoned him, he could bring

The Bulgars neath the sway of his great king.

Ungiardo learnt what ruin had ensued,

From those who had fled the savage plain,

(For, squad by squad, an endless multitude

Arrived, the bridgehead having failed to gain)

And that by a warrior they’d been pursued,

By whom a host of Greeks were swiftly slain;

And that same knight had led the charge alone,

By which one force was saved, one overthrown;

And that, of his own will, he’d run his head

Into the net, gave some cause for wonder.

Ungiardo showed his joy at what was said,

With every last word, and look, and gesture.

He waited till Ruggiero was abed,

Then sent his guards to enact the capture,

Who promptly took the unsuspecting knight,

While fast asleep, amidst the dark of night.

Canto XLV: 10-12: Constantine receives news of his capture

In Novigrad our brave Ruggiero

Was imprisoned; the fact brought much pleasure

To that cruellest of men, Ungiardo;

He savoured his good fortune at leisure.

Yet what could he have done against the foe,

Our knight, asleep, what countermeasure,

Taken, naked and bound? A messenger

Soon carried the news to the emperor.

Constantine had departed, that same night,

From the Sava’s shore, with his whole army,

And to Beletrik had gone, though not in flight,

Androphilus his brother-in-law’s city,

Father of him whose armour, in fierce fight,

Had been pierced (as if twas soft as putty)

At their first encounter, by Ruggiero,

That now was held fast by Ungiardo.

There, the emperor had strengthened the wall,

And, once the gates were repaired, thus defied

The Bulgarian forces, who stood tall

Having such a valiant knight on their side,

That of his Greeks had made a deadly haul;

Nigh every man might easily have died.

Hearing of his capture, now quelled all fear,

Though the whole world in arms were to appear.

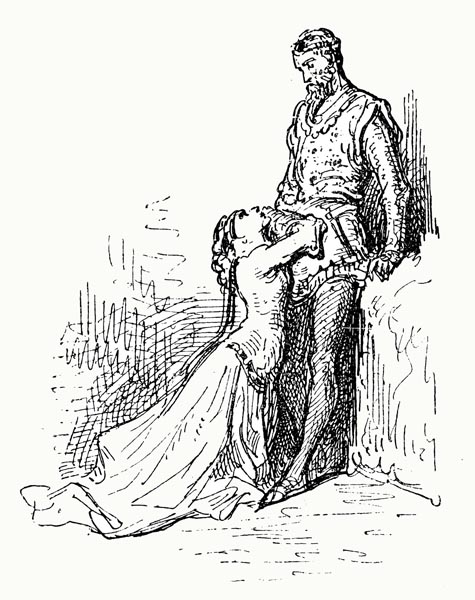

Canto XLV: 13-18: Theodora seeks vengeance on Ruggiero

‘Swimming in a sea of milk’, the emperor

Could scarcely express his sheer delight,

‘Truly I may call myself the victor,’

He cried happily ‘now we have their knight.’

As sure of his success as the soldier

That lops off his foe’s two arms in the fight.

Such was the pleasure the news had given

Him, on hearing Ruggiero had been taken.

No less cause had the emperor’s son, Leo,

For delight, for he hoped to gain Belgrade,

And subdue the country round; Ruggiero

Too he hoped to gain, and deploy his blade,

Fighting with his own men gainst the foe;

Nor need he envy (if his ranks displayed

That mighty warrior) King Charlemagne

His Orlando or Rinaldo, known to fame.

Theodora, was of a different mind,

Her dear son slain by Ruggiero’s lance,

That piercing his breast had emerged behind,

(A hand’s breadth) with the force of that advance.

She was Constantine’s sister; and, half-blind

With grief, assailed by ill circumstance,

She knelt at his feet, and stirred his pity,

Tears falling from her eyes, scorning mercy.

‘I shall not rise again, my lord,’ she cried,

‘Except you take revenge upon this knight,

Now your captive; through him my dear son died

Who was ever your champion in the fight,

Your nephew, who loved you; for our side,

Many a deed he wrought of skill and might,

Surely it would be wrong not to exact

Vengeance on this man now, for his vile act!

See how the Lord, in pity for our woe,

Removes this cruel warrior from the field,

Like some bird, unsuspecting of its foe,

Lures him into the net, so well-concealed,

So that my son need not wait long, below,

On Styx’s shore, till our revenge is sealed.

Give him to me, my lord, and be content,

For my pain to be eased by his torment.’

His sister wept and mourned so movingly,

And so effective was her woeful plea,

(She would not rise upon her feet, though he

Tried three times and more, pityingly,

To raise her by his words and actions; she

Refused, till he was forced to yield, you see)

That he gave way before her just demand,

And she received the knight, at his command.

Canto XLV: 19-24: Charlemagne proclaims the contest Bradamante requested

That they might not appear dilatory,

His guards took the ‘Knight of the Unicorn’

And led him to Theodora, promptly,

With but a night’s respite, in the morn.

Merely to see him quartered, publicly,

With a show of opprobrium and scorn,

Seemed slight revenge; he must undergo

Other novel, and immeasurable, woe.

That cruel woman had him chambered deep,

Chains about his neck, and hands, and feet,

In the darkness, beneath a dungeon-keep,

Where never a ray of sunlight might greet

His purblind eyes; a tender heart might weep

To see the mouldy bread he had to eat,

Some days none; his gaoler did her will,

Prompter even than she to work him ill.

Of, if brave and lovely Bradamante,

Or that magnanimous maid, Marfisa,

Had but heard news of such cruelty,

And how he was a wretched prisoner,

Would they not have sought his liberty;

Regardless of every threat and danger?

Nor would Bradamante have obeyed

Her parents’ orders, but have brought him aid.

Meanwhile King Charlemagne, who bore in mind

The promise he had made to her, that none

Should win her who proved less in martial kind

Than her in battle, that was a paragon,

Had his decree proclaimed to all mankind,

For not only at his court, and in person,

But far and wide the thing was trumpeted,

Thus, swiftly through the land the news was spread.

This the condition that was stated there:

He that would wed Duke Amone’s daughter,

Must from dawn to dusk, against the fair

Maintain, with the shining blade, his honour.

And if he could but last out the affair,

Undefeated, then that knight should have her;

The maiden deemed to have lost the fight,

And, thus, obliged to marry him outright;

And she the choice of arms would forego,

Without questioning the suitor’s right.

(This was not to her disadvantage though,

Being skilled with all weapons, in a fight,

Mounted or on foot.) All this being so,

Amone could not go against the might

Of Charlemagne, and yielding, finally,

Resolved to ride to court, with Bradamante.

Canto XLV: 25-30: She has no news of Ruggiero and is in doubt

Though her mother felt disdain and anger,

Twas nonetheless a question of honour

That she should have rich garments about her,

In varied styles, of more than one colour.

Bradamante left for court with her father,

Though, on finding no trace of her lover,

King Charlemagne’s noble court seemed no more

As fair a place as it had seemed before.

Who views the garden; its leaves and flowers;

In April or May, a most lovely sight,

And then regards it in its autumn hours,

The days short, in the sun’s declining light,

And finds it robbed of spring, neath wintry showers,

So, with Ruggiero absent, scant delight

Did Bradamante find on returning

To the court, mere emptiness discerning.

She dared not ask where the knight had gone,

For fear of arousing folk’s suspicion,

But kept her ears open, lest, here or yon,

Someone might speak, though she asked no question.

That he had left she knew, yet learnt from none

As to which road he’d taken, or his mission.

Since he, on leaving, had said nary a word

Except to the squire with whom he’d conferred.

Oh, how she sighed! What fears she countenanced,

Feeling as if he’d not just gone, but fled,

(Oh, how her fears and doubts were thus enhanced!)

Perchance to drive thoughts of her from his head!

Since Leo’s cause her father now advanced,

Had he lost hope that they might ever wed?

Perchance far from her he’d sought to remove,

Hoping he might forget her, and her love;

Perchance that very journey he had planned

To remove her more swiftly from his heart,

And would wander now from land to land,

And meet some woman who, with subtle art,

Might end that love, he then at her command,

As a nail another from its place will start,

Tis said. A second thought then succeeded:

Ruggiero was true, her heart conceded.

She reproved herself for lending an ear

To so unjust and blind a suspicion.

Thus, one thought absolved the cavalier,

The other condemned him; intuition

Helped her not; this way and that, I fear,

She was drawn, unsure of her opinion,

And yet inclined to that which pleased her more;

Ever its opposite she must abhor.

Canto XLV: 31-40: She debates with herself and laments

And then recalling, frequently, to mind

What her lover had repeated often,

As if in error, she now grieved and pined,

That she’d felt jealousy and suspicion,

And, as if before her eyes, she would find

His image, and scorn her indecision:

‘I see,’ she said, ‘twas ill such to rehearse,

And yet the cause of it is cause of worse;

Love is the cause, that on my heart impressed

Your form, so graceful and so fine to see,

All your wit and ardour therein expressed,

All your virtues, that folk praise before me,

Such that it seems impossible that, blessed

By the sight of you, every fair lady,

Would not be stirred, and employ every art

To eclipse me, and draw you to her heart.

Ah, if Love would but show me your thought

As it has shown me your handsome face!

Then I am certain I would find, unsought,

Such revealed as all such thoughts efface,

And, thus, be quit of Jealousy, as I ought,

That would not so harass me, in this place.

For she, whose expulsion costs me great pain,

Would not be routed merely, but be slain.

I’m like some miser whose heart is so intent

On hoarding treasure, burying it there,

They cannot for one moment be content,

For to part from it brings fear and despair.

Since I can’t see or hear one who’s absent,

More fear than hope I feel, in this affair;

Fear is but vain, yet, be that as it may,

I cannot choose but yield myself its prey.

But no sooner shall I see, Ruggiero,

The light of your joyous face, appear,

Countering my every foolish doubt (oh,

I know not from where) than deceitful Fear

Shall, thereby proven false, be vanquished so;

Hope will conquer, and falsehood disappear.

My love, return to me, raise Hope again,

Whom Fear has overcome and well-nigh slain!

The shadows lengthen when the sun departs

And as they do so, idle fears are born,

Yet, when it rises, light restores our hearts,

And the fearful take comfort in the morn.

When he is absent, pierced by cruel darts,

All’s dread yet, present, I put dread to scorn.

My love, return to me, lest Hope, again,

Should be oppressed by Fear, and thereby slain!

Every flame seems alive, when tis night,

Yet is suddenly eclipsed by the dawn.

So, when my sun doth take, from me, his light,

Fear fills my heart, and renders me forlorn,

Yet no sooner in the sky does he shine bright,

Than Fear is gone, and Hope once more reborn.

My love, return to me, sweet light, appear,

And rid me of this all-consuming fear!

When the sun turns from us, and days shorten,

All the beauties of Earth are soon concealed,

The fierce gales blow, all the world seems frozen,

No bird sings, no fresh leaf or flower revealed.

Likewise, when your turn your light, unbidden,

From me, O my fair sun, my fate is sealed,

A thousand fears bring harshest winter, here;

Chill me on many a day throughout the year.

My sun, return to me, and bring again

The sweet and longed-for brightness of the spring,

Rid me of snow, and ice, and freezing rain,

Clear my dark, clouded mind; warm everything!’

As Philomena, or Procne that, fain

To feed their fledgling young on returning

Find the nest cold and empty, make lament;

As the turtle dove voices her discontent

On losing her mate, so Bradamante

Grieved, fearing the loss of Ruggiero;

Yet, sighing, and weeping copiously,

She, nonetheless, strove hard to hide her woe.

Oh, how much worse had been her agony,

If she had known all that she could not know:

That, tormented by pain at every breath,

Her love was prisoned, and condemned to death!

Canto XLV: 41-47: Leo enters Ruggiero’s prison cell and frees him

Of the pain the cruel Theodora

Now inflicted on the imprisoned knight,

While preparing to organise his murder,

The fresh torments, by day and by night,

Eternal Justice, in Leo’s ear, did murmur,

And, conveying to him Ruggiero’s plight,

Stirred his heart to bring the warrior aid,

Nor let noble virtue be thus betrayed.

The courteous Leo, that loved Ruggiero,

(Not that he knew the knight was so named)

Moved by the valour that the knight did show,

Unique, nigh-superhuman some had claimed,

Thought as to how he might his aid bestow,

And found a way, ere the brave knight be maimed;

Such that his cruel aunt might not complain

That he’d wronged her, in saving him from pain.

He spoke to the warder, that held the key

To Ruggiero’s cell, and said it suited

Him to visit the prisoner, privately,

Before the sentence was executed.

That night, with one sworn to secrecy,

Bold, true, and strong, to the persecuted

Captive he went, and there the gaoler

Gave him free access to the prisoner.

Not knowing it was he, the castellan,

Silently led him, with his companion,

To the dungeon where lay the wretched man,

Reserved for torment, then oblivion.

There, as their guide (for such was Leo’s plan)

Turned his back, with the plain intention

Of unlocking the door, a noose they cast

About the warder’s neck, who breathed his last.

Raising a trapdoor, by the rope provided,

Leo descended, to the cell below,

Lighted torch in hand, for there abided

Bound to a grating, our Ruggiero,

From the darkened torrent scarce divided

That beneath the dungeon walls did flow.

In a brief month, or in some shorter space,

Death must find one, in that noisome place.

Leo embraced Ruggiero and, in pity,

Said: ‘Sir knight, your virtue binds me to you,

With eternal bonds, and indissolubly.

I shall e’er show you the honour due

To a great warrior, and do so willingly,

Setting aside my safety, to pursue

Your own, putting my love for you before

That I hold for my parents, kin, and more.

I am Leo, you must understand,

The emperor’s son, here to bring you aid,

In person, and with my own loving hand

Free you, despite all danger, unafraid;

Though, if Constantine knew, he’d demand,

My banishment, and think himself betrayed.

For he hates you for the slaughter, indeed,

You wrought before Belgrade, every deed.’

Canto XLV: 48-50: Ruggiero is deemed to have escaped

He followed with other speech in this style,

Seeking to bring new life to Ruggiero,

While loosening his tightened bonds, the while.

The latter cried: ‘Infinite thanks I owe,

To you, and yet will render, with a smile,

This life to serve you, if you will it so,

Which I shall ever willingly restore

To you, and spend it if the need be sore.’

Ruggiero, they rescued from the pit,

Leaving, in his place, the dead gaoler;

Nor were they seen, in the doing of it.

To his house Leo led our warrior,

Persuading him to stay, till he saw fit,

In safety, secretly, a week or more;

Meanwhile he’d retrieve his steed (Frontino),

His arms, and armour, from Ungiardo.

At dawn the prison gate was found ajar,

The gaoler strangled, and Ruggiero fled,

Though none thought, without aid, he could go far;

Much talk there was, all which to nothing led.

The thought twas Leo’s doing was bizarre,

And none voiced it, for twas thought instead,

There being a great debt to be repaid,

He would rather slay him than bring him aid.

Canto XLV: 51-55: Leo decides Ruggiero shall fight Bradamante in his place

Ruggiero, struck by Leo’s chivalry,

Was left confused, and full of wonder,

So other than his thoughts, he seemed to be,

Whom he had sought in hatred, and anger.

Comparing this fair act of courtesy

With his prior conception, dissimilar

They seemed; the latter formed too hastily,

The former a deed of love and mercy.

All day and night he reviewed the matter,

With no other care, no other desire,

Than to discharge the debt by some greater

Act of chivalry, and did then aspire,

Whether life be long or short to, ever,

(Gone now was all his jealousy and ire)

Serve this Leo; a thousand deaths, indeed,

Were too little to repay him for his deed.

Meanwhile news came to the emperor’s court

Regarding Charlemagne’s proclamation,

That he who’d wed Bradamante, in short,

Must with sword and lance maintain his station.

News that, to Leo, little pleasure brought,

While his face revealed his agitation;

He believed that, thereby, his fate was sealed,

Feeling he could not match her in the field;

But musing, thereon, saw he might supply

All by cunning, if the skill was lacking,

For this unnamed warrior would gladly die

To serve him, and might bear to the jousting

His own insignia; he seeming, to his eye,

A match for any knight, and right willing.

And thought that, if the man would but agree,

He would conquer, and win him Bradamante.

But that required two things, of which the one

Was the knight to undertake the enterprise,

The other, since in his name twould be done,

That none must penetrate the youth’s disguise.

He summoned him, who to his cause he won

With eloquence; his plan to realise,

Ruggiero must ride to the encounter,

Under a false name, emblem and banner.

Canto XLV: 56-60: Ruggiero agonises over the matter

The Greek’s persuasiveness was great, but more

Than any eloquence with our Ruggiero

The obligation weighed, which he now bore,

Which he could not discharge except by so

Appearing, though the thought grieved him sore;

It seemed a thing impossible; his woe

He nonetheless concealed, as he replied,

That no request for aid would be denied.

No sooner had he said the words than he

Felt sorrow’s blade pierce his loving heart.

Night and day, the thought brought misery,

Afflicting, and tormenting with its dart.

Yet though his own death he could now foresee,

He could not repent of it, for his part,

For rather than scorn Leo, and deny

His debt, a thousand deaths he’d seek to die.

And death seemed certain; were he to forego

The lady’s hand, his life was forfeit too;

For they would slay him, his anguish and woe,

Or if anguish and woe would not so do,

His own soul he would free, of its sorrow,

The very bonds of life himself undo.

For aught he could more readily endure

Than see another wed the maid; therefore

He was disposed to die, as yet unsure

Of the manner of his death; now he thought

Twere best to let her pierce him to the core,

Offer his naked flesh, as there they fought;

For never more blessed were a death in war

Than at her hand, to gain the end he sought.

Yet saw that, except he obtained the maid

For Leo, then his debt remained unpaid.

For he’d promised to fight Bradamante

In true encounter, so as to win her,

Not feign, and show the semblance only,

Thus, failing Leo; thus, as ever,

He chose the way of honest chivalry,

And although great anguish he must suffer,

He drove all thought away, except this thought:

That he must keep his promise, as he ought.

Canto XLV: 61-63: They reach Paris

With leave from Constantine, his father,

Leo had now readied arms and armour,

And had gathered a suitable number

Of men, and they all set out together.

Ruggiero rode Frontino, his courser,

Clad in his own gear, thanks to the other,

And day after day they rode, like this,

Till they entered France, and so reached Paris.

Not wishing to enter that fair city,

Leo pitched his pavilion on the plain,

While the arrival of the embassy

Was made known that day to Charlemagne.

The king was pleased, and with true courtesy,

Sent many gifts, and visits did maintain;

Leo gave the reason for his coming,

Asking that he expedite the jousting,

And let the valiant maiden take the field,

That would wed no man less skilful than she,

For he was there to make the lady yield,

Or die in the attempt; his bride she’d be.

Charlemagne agreed and, with sword and shield,

She appeared next day; the lists hurriedly

Marked out before the wall, that very night;

Thus, all was ready to commence the fight.

Canto XLV: 64-69: Ruggiero prepares for the contest

The eve before the contest, Ruggiero

Felt like a condemned man about to die,

Knowing he must pay upon the morrow

With his life, and so much troubled thereby.

He would be clad in Leo’s armour, so

Himself unknown to any watching eye.

His steed and lance would in this be ignored,

For he’d employ no weapon but his sword.

No lance he’d take, but it was not through fear

Of that gold lance Argalia once wielded,

And then Astolfo, that had year by year

Downed many a knight howe’er well-shielded,

All unknowing that twas to a charmed spear,

One forged by necromancy, they’d yielded;

Twas King Galafrone wrought the weapon,

And gave it to Argalia, his son.

Astolfo bore it, now Bradamante,

Neither thinking that it was enchanted,

But that they used the thing most skilfully,

Not that its power their strength supplanted.

That with some other lance they’d, equally,

Have toppled their foes, they took for granted.

Twas not fear of it deterred Ruggiero,

But of employing his steed, Frontino;

For she’d readily recognise the steed

If she saw him, since, in Montalbano,

She had ridden that horse of noble breed.

It presented a problem to Ruggiero,

Filled his every passing thought, indeed,

How he might act so she’d not come to know

That twas he; and so, he hid Frontino,

With all that his identity might show.

He brought a fresh blade to the encounter,

For he knew that steel was soft as putty

When twas matched against this Balisarda,

No armour could resist its enmity,

For it beat on other swords like a hammer,

And reduced their strength and their utility.

So armed, Ruggiero entered on the field,

As night, to the first rays of light, did yield.

To seem like Leo, the surcoat he wore

Was one the prince was accustomed to wear.

A twin-headed eagle, in gold, he bore,

On the crimson shield, he sported there.

And what sustained the fiction even more

Was the equal size and stature of the pair.

He presented himself so like the one

His true identity was known to none.

Canto XLV: 70-71: Bradamante proves eager to begin

Twas the will of the maid, Bradamante,

To have her sword prepared quite otherwise.

While he hammered at his blade till bluntly

It would fall, she whetted hers till edgewise

It gleamed, and she wished herself entirely

Absorbed into the steel, so she might prise

The life from out this Leo, and impart

Such fierce blows as would pierce him to the heart.

As one sees a fiery steed prick its ears,

While attending on the sign to commence,

And shift here and there, as the foe appears,

Its nostrils flaring, eager to speed thence,

So, the bold maiden seemed, devoid of fears,

(Thinking he was Leo, in her defence!)

With fire in her veins, awaiting the call,

Pacing restlessly about, yet standing tall.

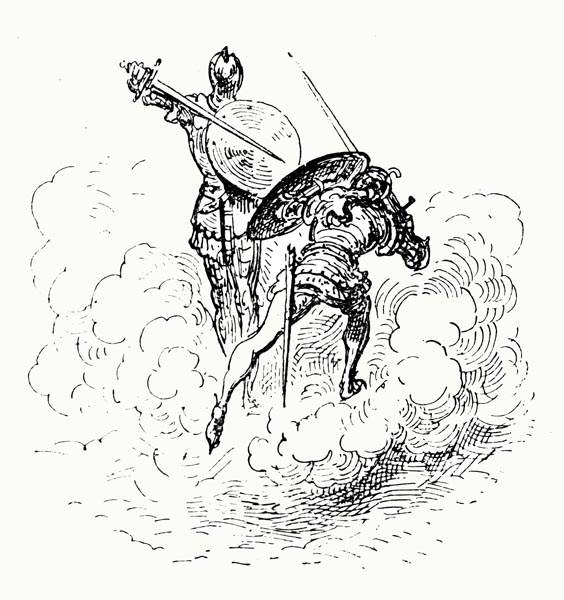

Canto XLV: 72-77: The fight commences and Ruggiero defends stoutly

As sometimes, after thunder, a sudden gale

Troubles the sea, and churns the waves about,

And raises clouds of dust that swiftly sail

Through the sky, and drives on the clouds in rout,

While the flock, and its wise shepherd, turn tail,

As hail and sleet from out the darkness spout,

So, the maid, on the signal, bared her sword,

And fell upon Ruggiero, her sweet lord!

But no more are ancient oak, or mighty wall,

Or well-founded tower moved by the storm,

That rages about them; no more the squall,

Shifts the rock that’s battered by the swarm

Of waves that, night and day, upon it fall,

Than her blade could those plates of steel deform

That Vulcan had gifted Trojan Hector.

For they yielded not to this storm either.

A hail of blows she landed, lunging too,

Wholly intent on entering that steel,

And driving her frantic blade, through and through,

To vent her ire, her hatred thus reveal;

Now here and there, sought, ever and anew,

To pierce his last defence, and have him feel

The fury in her heart, yet grieved to find

He thwarted every move she had in mind.

Like one who lays siege to some great city,

That’s flanked by battlements set on high,

And launches many an assault, that surely

Must breach the wall (not caring who must die)

Yet toils in vain to enter, so strongly

The walls defend it, and his blows defy,

So Bradamante toiled, to small avail,

Failing to pierce his armour, and stout mail.

Though sparks flew from his helmet, from his shield,

From his breastplate, as she aimed at his head,

And then his arm, and chest, he would not yield

An inch; though blows fell, as on a farmstead

The rain resounds, that sweeps across the field,

Or the blind hail, that o’er its roof is spread,

He defended himself from each attack,

With care and caution, scarcely striking back,

For he’d cease, or turn aside, or withdraw,

As his feet matched the motion of his hand,

Or he’d raise his good shield, when he saw

Her sharp blade advance, and the blow withstand.

His blows flew wide or, if he sought to draw

A drop of blood, some skilful move he planned

To do least harm; ere the sun descended,

The lady wished the fight swiftly ended.

Canto XLV: 78-80: He maintains his stand and thereby wins the fight

She recalled her edict now, for she knew

Her peril if twas brought to a close

Without her conquering him, nor anew

Could it be fought; her fate lay in her blows.

The time for Phoebus to retreat was due,

Past Hercules’ pillars, ere the moon arose,

When she began to doubt her skill and strength,

Appearing to abandon hope, at length.

The more hope faded, the more her ire grew;

She redoubled her blows, and strove to break

The steel that had defied their force, anew,

And had endured all day (of charmed make),

Like one who, slow their labours to pursue,

Sees night their toil and effort overtake,

Yet strives and heaves, still, all to no avail,

Till light and strength, together, ebb and fail.

O wretched warrior-maid, had you known,

Whom it was you wished to wound and slay;

If Ruggiero to your sight had been shown,

On whom your happiness depended (nay,

You’d have pierced your own flesh and bone,

Ere he was touched by your blade that day);

How swiftly, finding twas your own true lord

You would have rued the blows from your sharp sword!

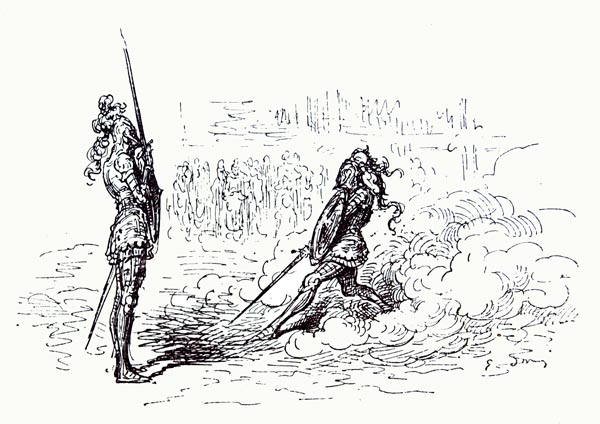

Canto XLV: 81-85: Bradamante must wed Leo, and Ruggiero departs

Charlemagne, with the rest, thought that Leo,

And not our Ruggiero, had won the fight,

Having seen how he’d absorbed blow on blow

And the speed and prowess shown by the knight,

Without dealing her much harm, and had so

Defended himself, that any wound was slight,

Now cried: ‘They’re well-suited to each other:

She is worthy of him, as he of her.’

Once Phoebus was hidden neath the tide,

Charlemagne bade the two go their ways,

Judging that the lady must be allied

To Leo, although both had won his praise.

Ruggiero, knowing he had lost his bride,

Still in armour and helm (for one obeys,

One’s king) mounted a sorry steed, and went

To where Leo waited for him, in his tent.

Leo clasped him twice, much like a brother,

And then he drew the helmet from his head,

Kissed him warmly on the cheeks, and ever

Held him close against his side, as he said:

‘Ask aught of me now, for you shall never

Find I weary of our friendship, instead

Both myself and my whole estate, entire,

I shall expend to serve your least desire.

No recompense, I know of, could repay,

The mighty debt I owe you, though I gave

The garland from my head to you this day,

Who proved the very bravest of the brave.’

Ruggiero, upon whom his woes did prey,

And that loathed his life, scarce a word did say,

But, returning the emblems he had worn,

Was once more the Knight of the Unicorn.

He appeared as one now listless and spent,

And, as soon as was decent, he withdrew,

And from there to his lodging swiftly went,

Where, at midnight, he armed himself anew,

Saddled his steed, and, filled with sad intent,

Went his way, all while no one was in view,

And then followed the road that Frontino

Was pleased to take, bearing his Ruggiero.

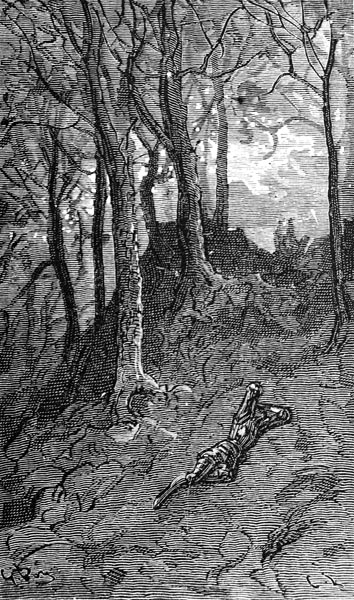

Canto XLV: 86-90: His lament

Now by a straight, now by a winding way,

Frontino passed, by wood, by open field,

And bore his lord and master far away,

Whose misery and woe were now revealed.

He called on Death, and in that solace lay,

Since life’s deep wounds by death alone are healed,

Thinking naught but death, the sufferer’s friend,

Could to this ceaseless torment put an end.

‘To whom should I complain of my anguish,

That robs me, evermore, of every good?’

He cried, ‘If I must take revenge for this,

On whom would I avenge me, if I could?

None but myself the guilty party is,

None else offends me; then, tis understood,

Upon my own self I must avenge me,

That brought about this endless misery.

If the injury were but done to me,

Perchance I could forgive myself, in time,

And yet I cannot, for Bradamante

Was injured, equally, by my sad crime.

How could I do so with impunity

And so, from out this vile darkness climb?

Even if I could cleanse myself of this,

I must avenge my marring of her bliss.

I ought to avenge her, and so must die,

Which is no heavy thing to undertake.

Except for death, I know no means whereby

To ease my heart, and twould be for her sake.

And yet I grieve I wrought not thus, ere I

Offended her, and did her poor heart break;

Better if I had died before I fought her,

Executed, at the whim of Theodora.

Though ere I died she’d have tortured me,

In many a cruel manner, yet I might

Have retained the hope, in my misery,

That Bradamante pitied my sad plight.

But, knowing honour has meant more to me

Than her love, that, of his will, her knight

Chose Leo over her, and in his stead,

She’ll loathe all thought of me, alive or dead.’

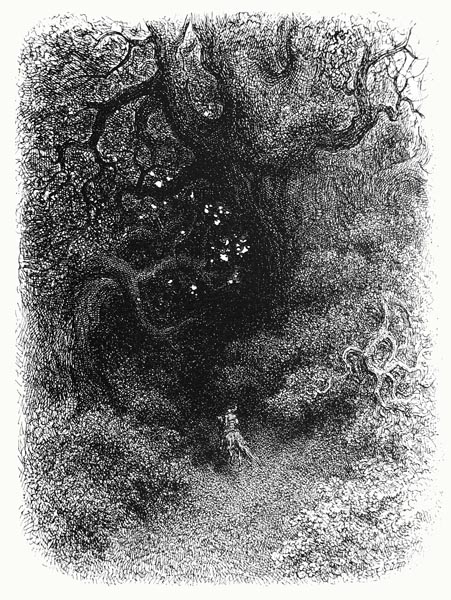

Canto XLV: 91-94: He seeks some place to end his life

This, and many another thought, he spoke,

Accompanied by many a deep sigh,

And found himself, as the world awoke,

In a dark wood, wild and foreign to the eye,

Where, desiring to shed life’s weary yoke,

He sought a hidden place in which to die,

Its silence seeming fitting for such a deed;

Twas remote, and melancholy, indeed.

He plunged within, till he could scarcely see

Amidst that dark, dense, and entangled wood;

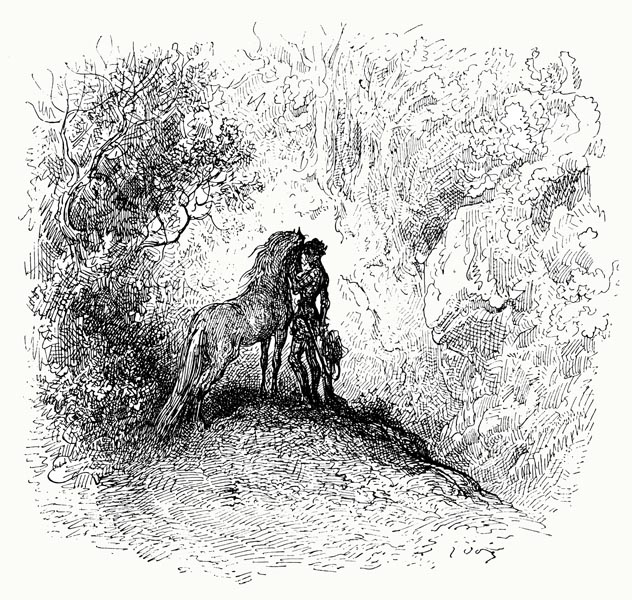

And first he set the steed, Frontino, free,

Caressing the brave creature where it stood,

‘Frontino,’ he cried, ‘were it granted me

To reward your great merit as I should,

You’d have scant need to envy those, brave, few

Set amidst the stars, glorious to our view.

Castor’s Cillarus, was not more worthy,

Adrastus’ Arion ne’er earned more praise,

Nor any other steed that’s famed in story,

Its name proclaimed in Greek and Roman days;

None, I say, could ever match your glory.

Though they might equal you in other ways,

They could never boast that they had won

Such honours and prizes as you have done;

Then, you are dear to the fairest lady,

That ever was, or that will ever be;

So dear that her hands would feed you, daily,

Saddling and bridling you, most graciously.

Dear to my lady fair; ah, woe is me,

Why do I call her mine, so foolishly?

Having gained her for another? Why wait

To use my sword and, thus, fulfil my fate?’

Canto XLV: 95-102: Bradamante’s lament

If our Ruggiero was so tormented

That he moved the birds and beasts to pity,

(For no human heard how he lamented,

Nor saw the tears he shed so copiously)

Think not Bradamante more contented,

That, as yet, remained in Paris, for she

Lacked all further excuse to justify

Delay, but must wed Leo, by and by.

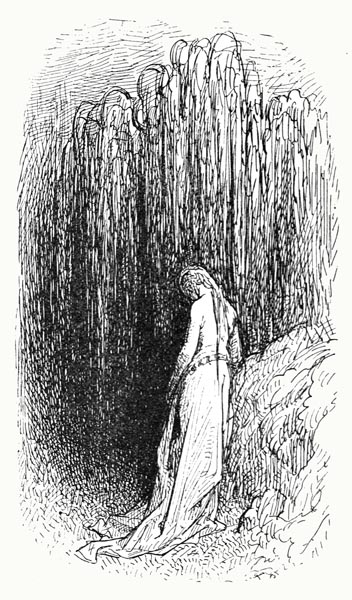

![Ariosto - Orlando Furioso - Canto XLV: 95 [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Italian/interior_ariosto_orlandofurioso_cantoxlv95b.jpg)

Ere she must take another to her bed,

And lose Ruggiero, she’d do what she might,

Forego her word, belie what she had said,

Anger her parents, and Charlemagne slight;

And, if she could do naught, then better dead,

Of poison, or a sword-thrust, for twas right,

And better far, to take her own life so

Than live on, and yet lack her Ruggiero.

‘Ah, Ruggiero,’ she cried, ‘where were you?

Is it that you, so far from me, now stray?

That you heard not the edict, all but you

Must have heard, and were absent on that day?

None would have sped here faster than you,

Had you known of it, my fears to allay.

Ah, woe to me, what else should I believe

Than that which is the worst I can conceive?

How is it Ruggiero that you alone

Failed to hear what all the world must have heard?

If twas so, and naught of this have you known,

Surely you must be prisoned, or interred.

No doubt that son of Constantine has sown

The seeds of this, spread some misleading word,

Or treacherously barred the way to you,

Such that the thing was hidden from your view.

I gained Charlemagne’s promise that to none

Less valorous than myself should I be given,

Believing you alone would be the one

With whom I should then have vainly striven,

For I thought by you alone I must be won.

My audacity has been repaid, and Heaven

Grants me now to a man that has never

Done aught in his life that gained him honour.

If he weds me (since I lacked the skill

To make him yield, or slay him swiftly)

It yet seems wrong that, all against my will,

I must thus accept Charlemagne’s decree.

I know that I’ll be thought contrary still,

If I retract what I proposed but lately,

But not the first maid nor the last I’ll be

To stand accused of mere inconstancy.

Enough that I keep faith with my lover,

And, firmer than any rock, remain true,

And thereby surpass all that have ever

Loved in those ancient times, or in the new,

And, though they call me inconstant, never

Care one iota, if but joy ensue.

Lighter than any leaf they may name me,

If with the Greek I’m not forced to marry.’

These words and others, interspersed with sighs,

And many a moan, she murmured to the night,

(Drenched with the tears that flowed down from her eyes)

That closed the day, and robbed the world of sight.

But when to his cave, neath Cimmerian skies,

Nocturnus, midst the shadows, sped in flight,

Heaven, that e’er desired the maid should be

Ruggiero’s bride, brought aid, as we shall see.

Canto XLV: 103-105: Marfisa addresses Charlemagne

For, at dawn, Marfisa went to Charlemagne.

The noble maid told him that her brother,

Ruggiero, had been wronged, for twas plain,

His sworn spouse would be wed to another,

And naught said against; let him maintain,

Who would, that the truth of it was other,

And prove to her (and stake his sorry life)

That the maid was not pledged to be his wife.

Let Bradamante say it was not so,

And deny it before them, if she dared.

The maid had pledged herself to Ruggiero,

In her own presence, and had so declared.

And, with the usual ceremony, so

Had it been sworn, and sealed, and naught impaired

The contract, they were thus bound together

And neither was free to wed another.

If what Marfisa said was less than true,

She was simply concerned, so I believe,

To thwart, rightly or wrongly, and undo,

Leo’s design than to a false truth cleave;

For Bradamante’s wish was now hers too,

And this was the best means she could conceive

To prevent the marriage to this Leo,

And see Bradamante wed Ruggiero.

Canto XLV: 106-111: Duke Amone complains

Troubled by her claim, King Charlemagne

Summoned the reluctant Bradamante,

And what Marfisa had said re-told again,

In the presence of her father, Amone.

Bradamante bowed her head, yet did not deign

To deny the fact, or to affirm it, wholly,

Such that all judged from her confusion

That Marfisa’s account was no fiction.

Rinaldo was much pleased, and Orlando,

To hear a valid reason now revealed

That no further might that alliance go

Which Leo thought already signed and sealed.

In spite of the objection to Ruggiero

That Amone maintained, and ne’er concealed,

Now, without further argument or strife,

He must give her to the knight, as his wife;

For, if such words had passed twixt the pair,

The knot was tied, and might not be undone.

Each must hold to what they’d promised there,

Without argument; each had the other won.

‘Tis deception here is wrought, I declare,’

Cried Amone: ‘to be credited by none;

For even if twas true, and not a lie,

Ne’er shall your errant wish be gained thereby.

For presupposing what I’ll not allow,

Nor will e’er believe in, that she has made

A foolish promise to him, scarce a vow,

As you claim, and he the same to the maid,

Where was the thing achieved? Come, tell me now,

More clearly, plainly it must be conveyed.

Either naught of this is so, as I’m advised,

Or twas done ere Ruggiero was baptised.

If twas ere he became a Christian,

I’ll not accept a jot of what they did.

Since she is of the faith, and he a pagan,

I hold all such contracts invalid.

Tis not for this that honourable man,

Prince Leo, fought; and the Lord forbid

That Charlemagne, our emperor, should break

His solemn word, and for a pagan’s sake.

What you say now, you should have said before,

Ere this thing, you claim, was done, and ere

King Charlemagne proclaimed from shore to shore,

That ill contest, swayed by my daughter’s prayer.’

Thus, to Rinaldo he laid down the law,

And to Orlando, seeking, then and there,

To deny their cause; while from Charlemagne

No precise opinion could they gain.

Canto XLV: 112-114: Marfisa suggests a further duel between Leo and Ruggiero

As when a south wind, or a north wind, blows,

Till the leaves murmur in the woods, on high,

Or as when Aeolus, the Wind-God, shows

His wrath gainst Neptune, till the breakers sigh

Along the shore, so the rumour that arose

Of this affair soon spread, through France did fly,

And prompted such discussion, far and near,

That of naught else did any wish to hear.

Some sided with our knight, some with Leo,

Yet, if one was of Amone’s party,

Ten, at least supported Ruggiero;

Though Charlemagne felt it was his duty

To choose neither, but have the matter go

To his parliament, to debate it fully.

But, since the marriage had been thus deferred,

Marfisa came to him, for she demurred.

‘As Bradamante cannot wed another

While my brother is still alive,’ said she,

‘Let Leo employ, if he would have her,

All his ardour, and end their rivalry;

Let the pair fight for her, and whichever

Kills the other shall wed her, rightfully.’

Charlemagne agreed, and sent to Leo

To so inform him, and soon, all did know.

Canto XLV: 115-117: Leo seeks the Knight of the Unicorn

Leo who felt his cause would be secure

If he asked the Knight of the Unicorn

To fight in his place, as he had before,

(One fit to conquer any warrior born)

Not having seen the saddened knight withdraw

Into that lonely woodland ere the morn,

Thinking he’d soon return and had gone

But a mile or two, expected him anon.

He would shortly repent of doing so,

For he upon whom he wholly relied

Failed to appear that day, nor to his woe

On the next two, nor any news beside.

And he was like to fight this Ruggiero

Unless, disguised, the knight his weapons plied.

So, he sent, to evade the harm and scorn,

Men to find this Knight of the Unicorn.

Through every town, and city, and castle

They searched for the knight errant, far and near.

Not content with this, he took to the saddle,

And sought the man himself, urged on by fear.

Yet, of the absent warrior, not a tittle

Would he have heard – or so it would appear –

Had it not been for Melissa; and, lo,

I shall speak of her, in my last canto.

The End of Canto XLV of ‘Orlando Furioso’