Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XLIV: A Marriage Delayed

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XLIV: 1-8: Ariosto on Friendship

- Canto XLIV: 9-11: The hermit urges the marriage of Ruggiero and Bradamante

- Canto XLIV: 12-14: Amone has promised Bradamante elsewhere

- Canto XLIV: 15-18: The warriors depart the island and reach Marseilles

- Canto XLIV: 19-23: Astolfo ends the enchantments and returns to France

- Canto XLIV: 24-27: He reaches Marseilles then frees the hippogriff

- Canto XLIV: 28-30: Ruggiero is presented to Charlemagne and embraces Bradamante

- Canto XLIV: 31-35: Charlemagne and all the company return to the city

- Canto XLIV: 36-40: Her parents oppose Bradamante’s marriage

- Canto XLIV: 41-47: Her lament

- Canto XLIV: 48-51: Ruggiero is also troubled in mind

- Canto XLIV: 52-58: He muses on his plight

- Canto XLIV: 59-66: Bradamante’s message to him

- Canto XLIV: 67-71: She makes request of Charlemagne

- Canto XLIV: 72-75: Her parents remove her from court

- Canto XLIV: 76-79: Ruggiero sets out to confront Leo

- Canto XLIV: 80-84: He finds the Emperor Constantine attacking Belgrade

- Canto XLIV: 85-89: Ruggiero rallies the Bulgarian troops

- Canto XLIV: 90-95: Leo admires the knight’s prowess

- Canto XLIV: 96-100: Ruggiero pursues the retreating Leo

- Canto XLIV: 101-104: He reaches a city and finds lodging

Canto XLIV: 1-8: Ariosto on Friendship

Hearts often join in friendship more fully

Beneath the humble roof of some poor dwelling,

Or in times of grief, or calamity,

Than midst the trappings of wealthy living,

In courts, rife with suspicion and envy,

Where none practice charitable giving,

And friendship is unknown, unless it be

That false connection born of flattery.

Hence pacts and agreements prove but frail,

Made between lords and princes. While today,

Twixt Emperor and Pope, peace may prevail,

Their deep distrust, tomorrow, they’ll betray;

For, with their outward manner, princes veil

The truth of their minds and hearts; while, I say

All seem indifferent to wrong or right,

And do what benefits themselves outright.

Though little capable of friendship (for

She loves not to dwell with those that flatter,

Who never speak except to lie the more,

Or jesting, or bent on graver matter)

Such folk, if they meet on some humble shore

That Fortune’s waves strike upon and batter,

Soon come to learn what friendship is, though they

Knew naught of it, while wealth and power held sway.

In his retreat, the ancient hermit could

Bind his martial guests with a tighter knot

To love and amity than e’er one would

In royal courts where such things are forgot;

So enduring, the bond, there rendered good,

That naught could sever it, if death did not.

The hermit found them pleasing to his sight,

Purer of heart than swansdown’s purest white,

Amiable, and full of courtesy,

Free of the sins that I spoke of before,

And such as reveal themselves openly,

Lacking disguise, and honest to the core,

Amongst them buried every memory

Of harm received on some forgotten shore.

If born of a single womb, and one father,

No greater love could they have shown each other.

Beyond the rest, the Lord of Montalbano

Embraced and honoured young Ruggiero,

As much for the fire he did ever show,

Lance in hand, in battle, and joust also,

As that he was as humane, fine to know,

As any knight in this our world of woe,

But more because Orlando ever found

Himself, to him, by obligation bound.

He knew that he’d saved from mortal danger

Ricciardetto, when the Spanish king,

Had seized that knight and the king’s fair daughter;

And that he’d thwarted the evil-doing

Of Bertolagi and all those other

Maganzeses, from the Saracens freeing

Duke Buovo’s two brave sons (as I have said)

And had left his foes sore-wounded or dead.

His debt, indeed, seemed to him of the kind

That obliged him to hold Ruggiero dear.

It had grieved him, and troubled him in mind,

That he could not as a truer friend appear,

While the youth was still to Africa aligned,

And he for King Charlemagne couched the spear.

Now that he knew him for a Christian

The Count could do what then was under ban.

Canto XLIV: 9-11: The hermit urges the marriage of Ruggiero and Bradamante

With honour, and many a courteous offer,

He greeted, and welcomed, Ruggiero.

Viewing his great warmth, the holy father,

Seeing an opening, addressed him so:

‘Naught else remains to do (and I rather

Hope that it may be done, and none say no)

But that, being conjoined in amity,

You should seek yet closer affinity;

So that, from two lineages that none

Can match, here below, in nobility,

Shining brighter than the brightest sun,

A race shall appear, whose fame and glory

Will grow as centuries their courses run,

And will endure, in its power and beauty

(This God instructs me to inform you of)

As long as the starry sky shall wheel above.’

And expanding his speech yet more fully,

The hermit asked Rinaldo to persuade

Ruggiero to wed fair Bradamante,

Though neither needed her Rinaldo’s aid.

Their union the lord of Anglante,

And Oliviero welcomed, while both prayed

That Amone and Charlemagne would bless

Such a marriage, and all of France no less.

Canto XLIV: 12-14: Amone has promised Bradamante elsewhere

They thus agreed, not knowing that Amone

Had won the consent of King Charlemagne

To the marriage of the fair Bradamante,

With the heir of the Greek Emperor’s domain,

Constantine’s heir, Leo, who had lately

Sought the maid’s hand, if she would so deign.

Though he had seen her not, the youth, inspired

By talk of her worth, to her love aspired.

Amone had answered the youth, saying

That he alone could not decide the matter,

But with Rinaldo must agree the thing,

Who was absent from court; the warrior

He said, would surely welcome the wedding

And rejoice in what would bring great honour

To their House, but his respect for his heir

Meant they could not yet seal the whole affair.

Meanwhile, far from his father, Rinaldo

Knowing naught of the imperial request,

Had promised his sister to Ruggiero,

At the hermit’s and Orlando’s behest,

While such was his own desire, also,

And again, it was welcomed by the rest,

Believing that the marriage would surely

Be pleasing to his father Amone.

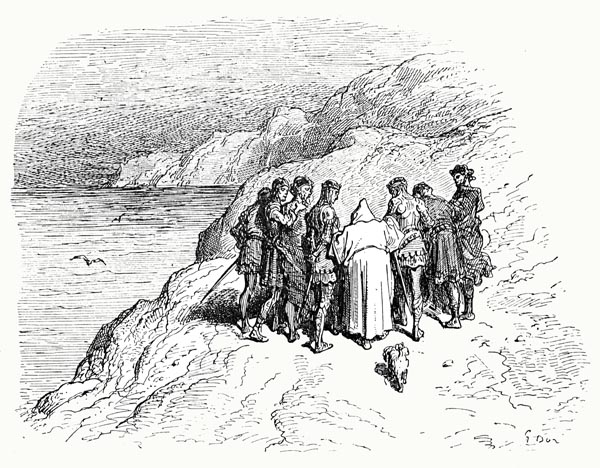

Canto XLIV: 15-18: The warriors depart the island and reach Marseilles

They remained with the wise monk that night,

And a large part of the following day,

Not wishing to return aboard outright,

Though a fair wind might speed them on their way.

Every message they received, from first light,

The sea being calm, summoned them away,

The master begging them to seek the shore,

Urging the company to depart once more.

The exiled Ruggiero who’d not sought

To remove from that island sanctuary,

Now took his leave of one that had taught

Him the virtues of Christianity.

Balisarda, with which Gradasso fought,

Hector’s armour, and Frontino, swiftly

To Ruggiero, the Count did now restore,

A mark of love, though they were his before.

And though that enchanted blade by right

Should have been borne by brave Orlando,

(That, with the exercise of his full might,

Gained it, in that dread garden, long ago)

Rather than the youth (who, without a fight,

Had received it from the thief Brunello,

With the steed, Frontino) yet, with the rest,

He granted it the youth, at his request.

They were blessed by the holy devotee,

Then returned to their vessel, gave their sail

To the pleasant breeze, their oars to the sea

And sped, with never a sign of a gale,

Nor vows or prayers required, of danger free,

Reaching Marseille’s harbour without fail.

There, safe at anchor, let the knights remain,

Till I’ve brought Astolfo to France again.

Canto XLIV: 19-23: Astolfo ends the enchantments and returns to France

When, following his hard-won victory,

That a deal of blood, and small joy, had gained.

Astolfo saw that France would now be free

Secure from the Moors, its lost lands regained,

He thought to send the Nubian army,

Home with its Emperor, and thus maintained

That they should return by the self-same track

That they’d taken to Hippo, ere the attack.

Meanwhile Dudon had emptied all the fleet

That routed the pagans: and suddenly,

A fresh wonder, the vessels all complete,

Were changed, bow to stern, miraculously,

To green fronds once more, in a mere heartbeat,

Reverting to what they once were, wholly,

And, lost to the wind, were lifted with ease,

Through the clear air, to vanish on the breeze.

The Nubian soldiers, and the cavalry,

From North Africa homeward took their way,

But first Astolfo gave thanks, profusely,

To Senapo, to whom he owed the day,

Who’d lent aid, while helping personally,

And doing all in his power in that affray.

Astolfo handed him the bulging skin

That held the fierce South Wind confined within;

The skin, I say, that kept one prisoned there,

Who, when free, would issue forth at midday,

And shift the sand in waves, and through the air

Send it flying, to obscure the light of day;

Thus, he could not, as onwards they did fare,

Emerge to blind, and smother, on the way

The weary troops; and then the emperor

Might free the wind, when they were home once more.

Bishop Turpin says that, once they’d attained

The heights of Atlas’ range, every steed,

The Nubians rode, its stony form regained,

Till all had vanished of that mountain breed.

But time it is Astolfo the fair strand gained

Of France, having conquered, as decreed,

All of the towns on North Africa’s shore;

So let the hippogriff take wing once more.

Canto XLIV: 24-27: He reaches Marseilles then frees the hippogriff

With a single beat, they made Sardinia,

And from there to Corsica he did soar,

Then took his way o’er the sea, though further

To the north-west and, in a little more,

Above the marshes, they did gently feather,

And landed in Provençe, upon the shore.

He leapt from the hippogriff, thereupon

Doing as he’d been told to by Saint John,

For he’d committed that he would no more,

Once they had reached Provençe, use the bit,

Or saddle the creature, or seek to gore

Its flanks with the spur, but swiftly free it.

As for his horn, its note had fled before,

There, on the Moon, to which all lost things flit;

For not merely hoarse but mute it remained,

Once the knight that sacred place had gained.

To Marseilles he came, on the very day

That Orlando arrived with Rinaldo

And Oliviero, anchoring in the bay;

Along with Sobrino, and Ruggiero.

The memory of their friend, on them did weigh,

Such that their welcoming of Astolfo

Was not as glorious or as happy

As they deserved, given their victory.

News from Sicily had reached Charlemagne,

Of the kings’ deaths, the wound to Sobrino

And that Brandimarte the Brave was slain,

And of the knights’ meeting with Ruggiero;

While he rejoiced to hear, and joyed again

At the African defeat of his foe,

From his shoulders the burden lifted, straight,

That had bowed him beneath its grievous weight.

Canto XLIV: 28-30: Ruggiero is presented to Charlemagne and embraces Bradamante

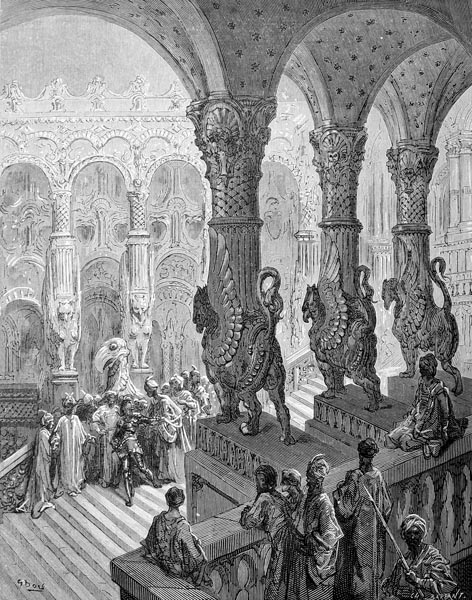

To honour those who were the strong pillars

That had upheld the Holy Empire thus, of late,

Charlemagne had despatched his noble peers,

As far as the Saône to meet them, in state;

He went forth himself, and many others,

Kings, and dukes, and his consort, from the gate,

To greet them, with that goodly company,

And, amidst them, many a lovely lady.

The emperor with clear, unclouded brow,

His kith and kin, every lord and knight,

Showed their love for Orlando; all did bow

To him and his company, in their delight.

‘Mongrana!’ ‘Chiaramonte!’ these were now

The cries that rose on high, as of right.

Then the Count, Rinaldo, and Oliviero,

Brought before the king brave Ruggiero,

Saying that of Ruggiero of Risa

Here was the son, and of equal virtue,

Ardent and courageous, and his valour

The army could affirm; his lance e’er true.

Then came Bradamante, with Marfisa;

Noble, and beautiful, appeared those two.

The former ran to embrace Ruggiero,

Though more restraint the latter maid did show.

Canto XLIV: 31-35: Charlemagne and all the company return to the city

The emperor had Ruggiero mount again,

Who’d quit his steed to show his reverence,

And rode beside him (for King Charlemagne

Would omit naught that his royal presence

Might add to the knight’s honour) midst his train.

He knew he was now a Christian, hence

Joyed in him, having learnt of this before

From his companions, once their ship touched shore.

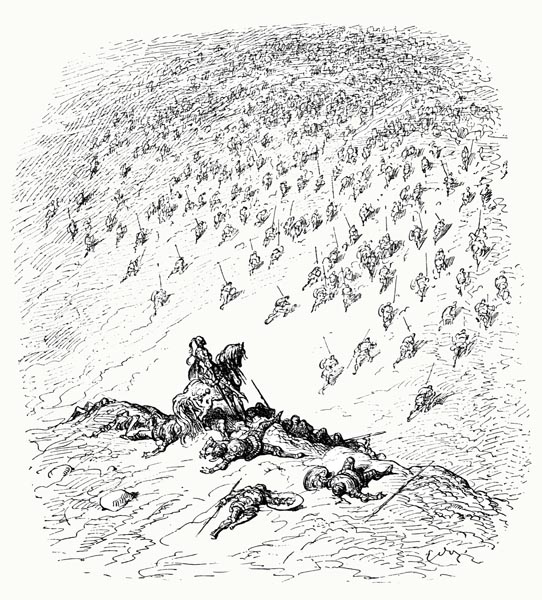

With triumphal pomp, and festive display,

These folk returned within the city wall,

Green leaves and garlands lining every way,

Tapestries and canopies shading all.

A host of flowers and herbs rained, that day,

O’er the conquering heroes, light in their fall,

From balconies, and windows; sweetly grown,

And by ladies, and fair maids, gently thrown.

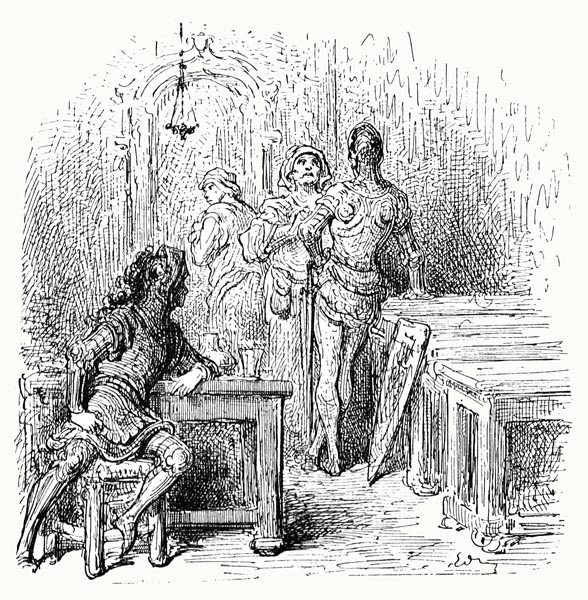

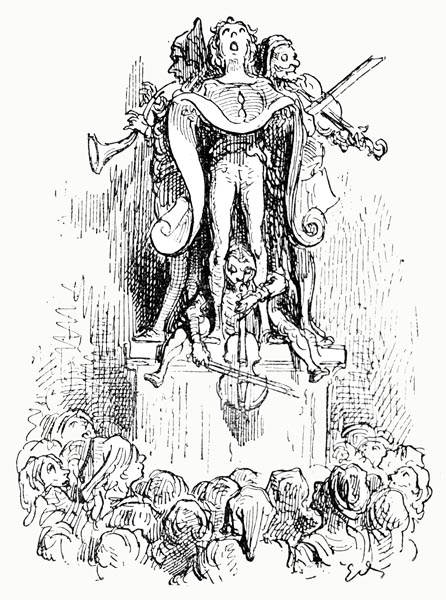

![Ariosto - Orlando Furioso - Canto XLIV: 32 [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Italian/interior_ariosto_orlandofurioso_cantoxliv32b.jpg)

In every street to which that pageant came,

Arches and trophies had been raised on high,

Showing Bizerte, in ruin and flame,

Brave deeds of chivalry wrought neath its sky;

Elsewhere were acted scenes from that same,

Where staged displays of conflict met the eye,

And on banners and inscriptions untold,

‘The Saviours of the Empire’ was writ bold.

To the sounds of pipes, and the trumpet’s call,

Amidst other instruments in harmony,

With laughter and applause attending all,

Surrounded by the people, packed tightly,

The king returned to feast in his great hall,

For many a day, midst noble company;

And many a tournament, and farce, and mime,

Was enacted, to honour that joyful time.

Rinaldo now made known to his father

That he wished to give fair Bradamante

In marriage to Ruggiero; that his sister

Had been so promised, Orlando lately

A witness, and Oliviero; and further

They considered that, for nobility

Of blood, and valour, there was none his peer,

None better to wed the lady, that was clear.

Canto XLIV: 36-40: Her parents oppose Bradamante’s marriage

Duke Amone reacted with disdain,

To the news that, without consultation,

He’d dared to plight the daughter whom he’d fain

Grant to Leo, the Greek Emperor’s son,

And not to Ruggiero, who’d ne’er reign

O’er aught, nor yet owned the least possession;

None prized nobility (and virtue less!)

Unless riches their company did bless.

But Beatrice his wife, reproached their son,

And called Rinaldo vain and arrogant,

And in private, or in open contradiction

To his wishes, showed herself indignant,

Intending her daughter’s elevation,

To Empress of the wide and rich Levant.

But Rinaldo proved obstinate, deferred

Not to them, nor would he retract a word.

The mother, believing Bradamante

Would ne’er thwart her, counselled her to say

That she’d not marry into poverty

And, indeed, would rather die than obey;

And told her she’d reject her most firmly,

If she let her proud brother have his way.

Let her refuse, boldly, and keep so, still;

He could never force her to do his will.

Bradamante was silent, not daring

To directly contradict her mother.

Such reverence, and true respect, bearing

Towards her, she desired to obey her,

Yet it was wrong, to her way of thinking,

To say what she’d ne’er agree to, ever;

Nor would, since she could not, thus approve

A course denied her by the power of Love.

She refused not, nor showed her discontent,

But only sighed, and stood there silently.

Yet once alone, and able to give vent

To her wretchedness, her tears flowed freely,

And marks of her misery, nay, her torment,

Carved on her breast, tearing her hair fiercely,

For the one she beat at, the other tore,

And, lamenting thus, but grieved the more:

Canto XLIV: 41-47: Her lament

‘Alas, shall I seek what she desires not

Who is more mistress of my will than I?

Shall I thus hold her wish not worth a jot,

Merely that I my own might satisfy?

Ah what greater shame is e’er the lot

Of any maid than boldly to ally

Herself to some man whom her dear mother

Rejects because she approves another?

Woe is me! Shall filial piety

Oblige me to abandon you, my love,

My Ruggiero, and so constrain me

To accept another, and that course approve?

Or shall I renounce such ties, entirely,

And from good parents, as mine are, remove

My allegiance, the respect a good child owes,

To gain what alone I wish, heaven knows!

I know, alas, what I should do; I know

All that a dutiful daughter should do;

Yet tis vain if Reason fails to follow

The urging of my heart, my senses too,

And, thus, retreats before the stronger foe,

While Love prevents me, binds me anew,

From following suit, and I must obey

That great lord, in all that I do, or say.

Amone’s and Beatrice’s child am I,

And yet the slave of Love, alas for me!

If I do wrong, and so am shamed thereby

I can but seek forgiveness and pity,

Yet, if I offend Love, who’ll hear my cry?

Whose prayers will save me from his fury?

He will ne’er wait for one excuse of mine;

To death, he’ll instantly my soul consign.

With long and obstinate persistence,

I sought to win Ruggiero’s conversion.

And now tis so; and yet, the consequence?

It seems that I’ll ne’er gain the reversion.

Likewise, the bees, in springtime, commence

To fill the hive with honey, though their action

Brings naught to themselves; yet I shall die,

Ere I wed elsewhere, and my love deny.

I shall reject my parents’ fond request,

It is my brother’s wish I shall obey.

Of far greater wisdom is he possessed;

Age has not left his heart in disarray;

And what Rinaldo wills he has professed

To Orlando; both will my doubts allay;

More to be feared, and honoured everywhere,

Than the rest of my House, in this affair.

They are the flower of Chiaramonte’s tree,

Its glory, its splendour, esteemed by all,

More than the rest in their true chivalry,

As the head o’er-tops the foot, the great the small.

Why should Amone thus dispose of me,

Rather than Rinaldo, and weave my pall?

He shall not; for I am in no way tied

To Leo; promised as another’s bride.’

Canto XLIV: 48-51: Ruggiero is also troubled in mind

If the lady grieved and was tormented

No less troubled was our Ruggiero;

If not yet by swift rumour presented

To the city, the news had reached him though,

And his lack of fortune he lamented

That opposed their desires and wishes so.

For wealth he lacked, or a mighty kingdom,

That to many an unworthy heir oft come.

Of all the virtues granted men by Nature

Or which are obtained by proper study,

He felt he had acquired a greater measure

Than others; especially of beauty

Such beauty as cannot be bought with treasure,

While few could face him in fight securely.

His magnanimity, his regal splendour

That none did more display, all did honour.

But the vulgar, those at whose disposal,

It seemed to him, all great rewards did lie,

(And in the common crowd I include all

But the wise, and condemn most thereby.

Since emperor nor king is raised as high

As such, by sceptre, crown or throne, say I;

For the wisdom and judgement that Heaven

Grants to us here below, to few is given);

The vulgar (to say all that I would say)

Who only revere their wealth and treasure,

And who admire nothing more, and betray

No sign of appreciation, ever,

For beauty, ardour, worth, be it what may,

Dexterity, virtue, goodness, honour,

Are more vulgar in this than all the rest,

And of their vulgarity stand confessed.

Canto XLIV: 52-58: He muses on his plight

Ruggiero mused: ‘If, indeed, Amone

Seeks to make an empress of his daughter,

A year might yet, by fate, be granted me,

Ere he has need to conclude the matter.

I’d hope by then to end that dynasty,

And remove both Leo and his father;

Wearing the crown that the latter wore,

I might prove a more welcome son-in-law.

But if without delay, as has been said,

He weds her to this heir of Constantine,

With no respect to that firm promise paid

Which Rinaldo (agreeing she’d be mine)

Before Orlando, and the hermit, made,

(Oliviero, Sobrino too gave sign

Of their consent) shall I but suffer more,

Or die ere such a grave wrong I endure?

What should I do? Take vengeance on her father

For the insult; a thing not hard to do!

I doubt the deed would be wise, but rather

An act of folly; with that aim in view

I might slay in a trice that wicked elder,

And all his tribe, and all his fair issue,

But that would hardly render me content,

Twould simply frustrate my whole intent!

For my intent was ever, and is now

To win the lady’s love, not her hatred.

Slaying Amone to achieve my vow,

Bringing harm to her kindred, as I said,

Would I not prove her foe; and she avow

To forget me, and treat me as one dead

To her, and to her love? Ne’er could I

Seek such a thing, twere better that I die.

I shall not die; rather, twould be better

To slay this Leo who disturbs my joy,

Him together with his unjust father.

Fair Helen cost her lover out of Troy

Far less; nor, did the earlier, bolder,

Theft of Proserpine bring such annoy

To Pirithous, as shall prove the cost,

And annoyance, to these, of my lover lost.

Can it be true, my life, that you grieve not

To leave your Ruggiero for this Greek?

Shall your father force you to tie that knot,

When your brother so supports what you seek?

I fear lest duty cannot be forgot,

And you’ll bow to Amone; twould be weak,

If you chose rather to wed with Caesar,

Than a humble, and yet honest, lover.

Is it possible: that dreams of royalty,

Imperial titles, majesty and grandeur,

Could corrupt the mind of Bradamante,

She of noble virtue, and endless valour,

Such that she broke her vow of loyalty

And viewed true faithfulness as lesser?

That she’d not sooner defy Amone

Than dismiss the pledge she made to me?’

Canto XLIV: 59-66: Bradamante’s message to him

These were his thoughts, and other things also

He debated with himself, and in such guise

That others who were with him, came to know

That he was troubled, nor could he disguise

His torment such that none learnt of his woe.

And Bradamante came to realise

The depths of his suffering, which once known

She sorrowed for no less than for her own.

But of all the sorrows that she was told

Were now tormenting Ruggiero, this

Grieved her by far the most, that he might hold

Some suspicion that she shared Amone’s wish.

To comfort him, and show her vow of old

Was unbroken, and so ratify her promise,

She sent her trusted maid to him one day,

With a letter, that did her thoughts convey:

‘Ruggiero, I would always be to you

What I was; even more if such could be.

Whether Love is benign or harsh anew,

Whether Fortune lowers or exalts me,

I am a rock, unmoved, and ever true,

Battered by gales, amidst the raging sea.

Be it winter, or spring and fair weather,

Through all eternity, I ne’er shall alter.

Sooner shall leaden chisel, descending,

Varied forms and shapes to diamond impart,

Than shall ill Fortune’s blows, never-ending,

Or Love’s fierce anger, move my constant heart.

Sooner shall the sounding torrents, raging,

Return to the Alpine heights where they start,

Than fresh events, destined for good or ill

Shall sway my thoughts, or undermine my will.

I have granted you dominion over me,

More so, indeed, than any might conceive;

No greater oath of endless loyalty

To new-crowned prince was sworn, I believe,

Nor any realm possessed more securely

Than is yours, Ruggiero; you need cleave

No stone to build high walls, or raise a tower,

For fear lest any other steals your power.

Without others’ aid, this I guarantee,

Every attack on you shall be repelled.

No display of riches shall e’er win me;

The gentle heart cannot be bought, upheld

Not by nobility, or royalty,

That dazzle the vulgar, plain truth expelled.

No beauty, that moves fickle hearts anew,

Shall make me wish for any, love, but you.

You have no cause to fear that my fond heart

Shall bear some new impression, or e’er could.

Your image is etched there, and with such art,

It cannot be removed, set there for good.

That my heart is not of wax, for its part,

Is known; Love has tested its hardihood.

He struck a hundred times, ere he could trace

Your image there, that ever holds its place.

Ivory, gem, or stone of hardest grain,

Resistant to the steel edge, may shatter,

Yet else the same form it must e’er maintain

That it first took, and can take no other.

And I am like to marble; none can gain,

With iron blade, a single flake; twould splinter

To a thousand pieces, ere Love’s rare art

Could grave a second image on my heart.’

Canto XLIV: 67-71: She makes request of Charlemagne

She added to this many another word

Of love, and comfort, and true loyalty,

That, if he were dead, and such might be heard,

Had yet restored his life and liberty.

But when his hope, many a time deferred,

Now looked to anchor, of the tempest free,

A dark and furious gale rose anew,

That seawards from the longed-for shore now blew:

For Bradamante, who wished to follow

Her letter by doing more than she’d said,

Her customary boldness then did show,

And straight to King Charlemagne she sped.

Casting all reverence aside, she spoke so:

‘If e’er my deeds have good fortune bred,

Or, Sire, to you have e’er seemed worthy,

Be pleased to bestow a gift upon me.

Yet first, Sire, ere I utter my request,

By the faith you hold to, promise me

You’ll grant this fervent prayer, at my behest,

For what I ask is right and just, truly.’

‘Your merit deserves that aught expressed

By you, I shall respond to willingly,’

Said Charlemagne, ‘I am content to swear,

Though of my kingdom you should seek a share.’

‘Then the gift I crave of Your Majesty,

Is that I not be wed to any knight’

Bradamante answered him, ‘save that he

Shows greater valour than I, in fair fight.

Who desires me must first, in brave tourney,

Or single combat, prove himself outright.

Let he that defeats me, my life, thus, share;

Him that I defeat, let him seek elsewhere.’

With smiling face, the emperor replied,

That her request was worthy of the maid,

And that upon his word she might rely;

He would accord her that for which she prayed.

This audience was public, and thereby

Others learned of the promise he had made,

And that very day it came to the notice,

Of old Amone, and the mother Beatrice.

Canto XLIV: 72-75: Her parents remove her from court

Her parents were roused to indignation,

Both were greatly angered by their daughter,

(Perceiving, and hence their condemnation,

That she despised Leo, as a suitor)

And to thwart Bradamante’s solution

To the matter, they simply removed her,

Both withdrawing from the emperor’s court,

Taking the maiden with them to Roquefort.

This was a mighty castle, built to plan

By Charlemagne, granted to Amone,

Set between Carcassonne and Perpignan,

Commanding the coast, and all the country

Thereabouts; and there prisoned, under ban,

The maid was held, and told she would, shortly,

Be shipped to the Levant, willing or no,

And, Ruggiero now forgot, marry Leo.

The valorous lady who was no less

Determined than steadfast and spirited,

Though no guard was posted, nonetheless,

Obeyed her sire, for the moment bested;

Yet prison, death, or pain and harsh duress,

She vowed to suffer, being nobly bred,

(Though at liberty there, to come and go)

Rather than betray her Ruggiero.

Rinaldo, on finding that his father

Had spirited her away, out of sight,

And seeing he could achieve naught further

As concerned her marriage to the knight,

Complained to his sire, and his favour

Withdrew from him, saddened by her plight,

Though Amone cared little, I suggest;

He would deal with the maid as he thought best.

Canto XLIV: 76-79: Ruggiero sets out to confront Leo

Ruggiero hearing this, full of dread

That he’d be deprived of his loving bride,

And, by consent or force, Leo, instead,

Would have the maid, resolved he’d ne’er abide

Till he had fought the man (though naught he said)

And seen this new Augustus deified;

For, unless his every hope proved in vain,

He’d rest not till the emperor was slain.

So, he dressed himself in Hector’s armour,

That which had been worn by Mandricardo.

His helm, shield and surcoat he did alter,

In their emblems, and saddled Frontino,

(For no longer on a field of azure

The silver eagle, as before, he’d show,

But a lily-white unicorn he revealed,

As his coat of arms, on a crimson field)

From his faithful squires, he chose the best,

For he needed none else, for company,

Commanding him to thwart each request

For Ruggiero’s name, where’er they be.

He crossed the Meuse and Rhine, on his new quest,

And passed from Austria to Hungary,

Then along the Danube his way he made,

Riding swiftly, until he reached Belgrade.

The Sava, there, into the Danube flows,

And swells it on its journey to the sea,

And there the Imperial banner rose,

And many a pavilion’s high majesty,

For Constantine’s Bulgarian foes

Held the place against his mighty army.

And Leo, was there beside his father,

With all whom the Greek empire could muster.

Canto XLIV: 80-84: He finds the Emperor Constantine attacking Belgrade

Before Belgrade, and o’er the slopes around,

Down to the river flowing at their feet,

The Bulgarian forces held the ground,

While at the Sava both sides deigned to meet.

The Greeks would bridge the river, at a bound,

The enemy were forcing their retreat,

When Ruggiero came there, to behold

That battle that raged, twixt squadrons untold.

The Greeks were four times as strong as the foe,

And supplied with pontoon-bridges beside.

They presented a bold and warlike show

Of forcing their way to the eastern side,

As, with considerable guile, Leo

Redeployed silently, and cast a wide

Circuit, then returned and bridged the river,

And, swiftly, led his bold squadrons over.

A host of foot-soldiers and cavalry,

(Not less than twenty thousand were there)

He sent along the river-bank, and fiercely,

Charged the foe, and nearly ended the affair,

While the Emperor watching, sought swiftly

To cross the flood, and any loss repair.

From pontoon bridge to bridge, linked boat to boat,

He passed with all his army, half-afloat.

King Vatran, the Bulgarian leader,

A warrior, spirited yet prudent,

Laboured hard their attack to counter,

And yet was swiftly foiled of his intent.

The king, toppled, fell beneath his courser,

While Leo his great battle-cry did vent,

As a thousand swords the king did slay,

For they took no prisoners, on that day.

The Bulgarian host had forged ahead,

But once they saw their sovereign laid low,

While everywhere their fierce attackers spread,

They turned their backs, and fled before the foe.

Amidst the Greeks, who o’er the bridges sped,

Went our brave cavalier, Ruggiero,

Disposed to aid the Bulgarians though;

Loathing Constantine, and more so, Leo.

Canto XLIV: 85-89: Ruggiero rallies the Bulgarian troops

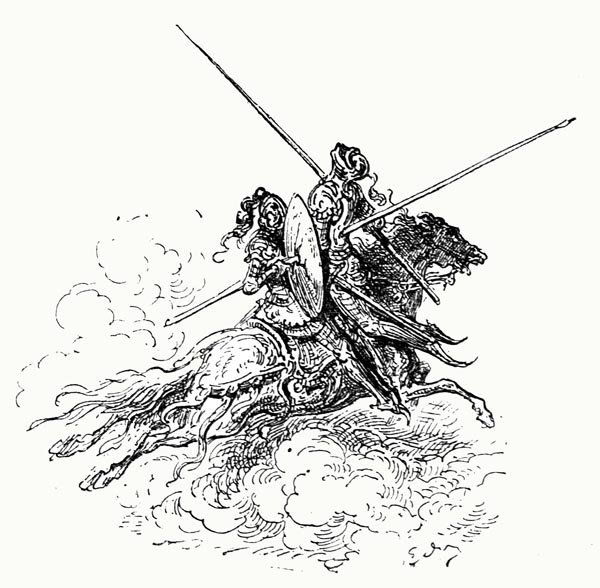

He spurred Frontino; like the wind he flew,

And hence soon outran the Greek cavalry;

Then the Bulgarian ranks came in view,

Fleeing the plain, seeking the slopes swiftly.

He halted their squadrons, bar one or two,

And turned them round to face the enemy,

His gaze so fierce, as they began to move,

Mars and Jove took fright in the sky above.

Out beyond the advancing Greeks he saw,

A rider, in a crimson surcoat dressed;

Woven emblems in silk and gold, it bore

Bright millet-pods, sprinkled o’er that vest.

Twas Constantine’s bold nephew rode to war,

His sister’s son, beloved above the rest,

Bar his own son. Ruggiero ran him through;

A foot behind, his lance appeared to view.

He left him dead, and raised Balisarda

Against a knot of men who fought nearby

One he struck, a second even harder,

Cleft torsos, and saw heads from shoulders fly.

Throat, chest, or flank, he pierced in his ardour,

Hand, or arm, or shoulder, belly or thigh,

Till a river of blood o’er the field did flow,

Slowly draining to the vale, there below.

None, that saw those blows dealt, stood his ground,

All were filled with fear, and deep dismay.

Thus, the Bulgarians fresh courage found,

For, taking heart from his wondrous essay,

As some Greek fled, a hare before the hound,

His foe would chase him down, to wound or slay.

In an instant, the Greek ranks were scattered;

Men fled with the banners, wounded, battered.

Leo Augustus, watching from a height,

Finding his soldiers routed, was amazed,

Sore troubled, and bewildered at the sight,

(For from there upon all the field he gazed).

He took notice of the prowess of that knight

That alone had slain so many, and he praised

To himself, though his dead now stained the earth,

His deeds, and acknowledged his great worth.

Canto XLIV: 90-95: Leo admires the knight’s prowess

By the surcoat, and the insignia,

And by the armour, bright with gold, he knew

That although to the foe he gave succour

This warrior was none of their vile crew.

He seemed of some superhuman ardour,

An avenging angel, that to pursue,

And punish, the Greeks had descended,

For their sins that, so oft, the Lord offended.

And, as a man of great and noble heart,

While many another might well have sworn

Hatred to Ruggiero, he, for his part,

Would not wish to see the man put to scorn,

And he had rather seen six Greeks depart

Than this one warrior, rather have borne

The loss of some wide tract of his own land,

Than a worthy knight be slain out of hand.

As a child, who has angered his mother,

And is driven forth, in shame and disgrace,

Runs not to his father or his sister

But soon returns, to meet a warm embrace,

For momentary wrath love doth conquer,

So, although the knight had put to the chase,

His squadrons, and thereby roused his anger,

Leo’s love was kindled by such valour.

If he admired, nay loved Ruggiero,

It would seem he gained little by the fact,

For the latter hated him, his mortal foe,

And wished naught but his murder to enact.

The knight was searching for him, high and low,

But naught of sense or fortune Leo lacked,

And the prudence of the battle-hardened Greek

Thwarted him that the emperor’s son did seek.

Leo fearing his troops might all be lost,

Sounded the retreat, and to his father

Sent a messenger to tell him, at all cost,

To halt his men, and re-cross the river,

For he’d likely meet with a swift riposte.

He himself, gathering a few together,

Made his way to his former crossing-place,

And over the pontoons they went, at pace.

Into the hands of the Bulgarians, many

A Greek now fell, and there was swiftly slain,

Corpses hid the slopes, the plain, and surely

All would have died had they not crossed again,

Yet many plunged from the bridges, wildly,

While others, that their first flight did maintain,

For safety, to a distant ford now made,

Or were captured, and taken to Belgrade.

Canto XLIV: 96-100: Ruggiero pursues the retreating Leo

When that day of battle drew to a close

In which their chieftain Vatran had died,

His valiant squadrons would, you may suppose,

Have been treated much as the other side,

Had the warrior not won them sweet repose,

Who bore the snow-white unicorn with pride;

With cries of joy, they greeted their hero,

Who’d brought them victory, our Ruggiero.

Some saluted him, while others made a bow,

Some kissed the warrior’s foot or his hand,

As closely as circumstance would allow,

They all surrounded him, a joyous band;

More simply touched him, for they did vow

He was scarcely mortal, you understand,

And wished thus, to be blessed; full loud they cried

That he must be their captain, king, and guide.

Ruggiero replied he’d be their king

Or their captain, whichever suited best,

But left sceptre and baton in their keeping,

Nor would enter Belgrade but take no rest,

And thus pursue Leo, and his following,

As they retreated swiftly to the west;

He’d renew their attack, nor turn away

Till he had slain the man that very day,

For he had come a thousand miles and more

For that alone, and for naught else beside.

And so, with scant delay, he sought the shore,

And by a road revealed to him did ride

For Leo, to the bridge, had gone before,

And he might yet attain the other side.

Now hotly on his heels, sped Ruggiero,

Leaving his squire behind him, to follow.

Yet Leo had so great an advantage

In his flight (twas a flight not a retreat)

That he found the way open, free of carnage,

Destroyed the bridges, and then burnt the fleet.

Ruggiero, spurring on, and filled with rage,

Failed to cross, ere the sun sank neath his feet.

He knew not where to rest, and yet rode on,

By moonlight, though lodging found he none.

Canto XLIV: 101-104: He reaches a city and finds lodging

Lacking a place to sleep, he rode all night,

And not once from the saddle did descend,

But when the sun arose, and all was light,

He saw a city on his left, and there did wend

His weary way, seeking a day’s respite,

When Frontino’s sad state he might amend,

That in battle, and on the road, he’d pressed,

Without disburdening him, or granting rest.

Ungiardo was the lord of that city,

A liegeman, who was dear to Constantine,

And had supplied the emperor with many

Loyal horsemen and soldiers, brave and fine.

Our knight rode in (none were barred entry)

And, once there, found a welcome so benign

He found little need to journey further

For nowhere else was like to prove better.

In the hostelry he’d found, that very night

Was lodged a brave Romanian warrior,

Who had been present at that bloody fight,

Where Ruggiero had aided the Bulgar.

He had scarcely escaped from our knight,

More afraid than he’d found himself ever,

And he trembled yet, sensing at his back

That great warrior bent on fierce attack.

He knew him, when first he saw his shield

(That white unicorn, on its crimson ground)

As the knight who had forced the Greeks to yield,

And left the dead heaped in many a mound.

He hastened to the palace, and revealed

All to its lord (a ready ear he found);

Though the tale that he told Ungiardo,

I shall reserve for the following canto.

The End of Canto XLIV of ‘Orlando Furioso’