Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XLIII: Two Tales and a Funeral

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XLIII: 1-5: Ariosto on Avarice

- Canto XLIII: 6-8: Rinaldo declines to drink

- Canto XLIII: 9-10: The host prepares to tell his tale

- Canto XLIII: 11-16: The origin of the palace

- Canto XLIII: 17-19: The marriage and the quarrel

- Canto XLIII: 20-23: The host is loved by the enchantress Melissa

- Canto XLIII: 24-31: Who seeks to shake his faith in his wife

- Canto XLIII: 32-35: Melissa alters his form to that of his wife’s suitor

- Canto XLIII: 36-40: His wife is compromised

- Canto XLIII: 41-46: And flees him for the other

- Canto XLIII: 47-49: Rinaldo condemns the whole affair

- Canto XLIII: 50-55: He boards a boat and heads for Ferrara

- Canto XLIII: 56-59: Malagigi’s prophecy of Ferrara’s future

- Canto XLIII: 60-63: Rinaldo is borne past the city

- Canto XLIII: 64-67: He muses upon the tale he has heard

- Canto XLIII: 68-70: Then enters into conversation with the boatman

- Canto XLIII: 71-74: The tale of Adonio

- Canto XLIII: 75-77: Impoverished, he leaves his native Mantua

- Canto XLIII: 78-81: Meets with an adventure, and years later returns

- Canto XLIII: 82-85: Anselmo is to go on an embassy to Rome

- Canto XLIII: 86-89: A mage prophesies that his wife Argia will be seduced

- Canto XLIII: 90-94: Anselmo transfers use of his wealth to her and departs

- Canto XLIII: 95-102: Adonio is visited by the shade of Manto

- Canto XLIII: 103-106: She transforms herself into a dog

- Canto XLIII: 107-112: The dog’s abilities are revealed

- Canto XLIII: 113-116: Argia succumbs and her husband returns

- Canto XLIII: 117-120: Anselmo attempts to learn the truth

- Canto XLIII: 121-124: Does so, and orders the death of his wife

- Canto XLIII: 125-129: The lady vanishes

- Canto XLIII: 130-133: Manto creates a palace for her to dwell in

- Canto XLIII: 134-139: Anselmo enters and is compromised by his greed

- Canto XLIII: 140-143: Argia appears and they are reconciled

- Canto XLIII: 144-150: Rinaldo journeys to Lampedusa

- Canto XLIII: 151-153: He arrives there after the conflict has ended

- Canto XLIII: 154-159: Fiordelisa learns of Brandimarte’s death

- Canto XLIII: 160-164: Her lament

- Canto XLIII: 165-168: The preparations for Brandimarte’s funeral

- Canto XLIII: 169-175: Orlando’s lament

- Canto XLIII: 176-180: The funeral procession

- Canto XLIII: 181-185: The death of Fiordelisa

- Canto XLIII: 186-189: The warriors sail to the hermit’s isle

- Canto XLIII: 190-194: Oliviero and Sobrino are healed

- Canto XLIII: 195-199: Ruggiero is recognised and welcomed to the company

Canto XLIII: 1-5: Ariosto on Avarice

O execrable Avarice, O greed

For possession! To me, tis no wonder,

That you seek to control each word and deed

Of base souls, degraded by their plunder.

And yet, with cruel chains, to bind, and lead,

While clawing with those same talons, ever,

Those, who of honour would be worthy

If they could but scorn you, and be free!

Some the earth, and sea, and sky can measure,

And render all the varied causes known

Of all the effects and works of Nature,

And soar, till to the heavens they have flown,

And yet care only to gather treasure,

With no greater end, no richer pasture sown;

Poisoned by your venom, such is their aim,

Their solace, their fond hope, and their shame.

Some that shatter armies and, through the gate

Of warlike cities, in triumph, proudly ride,

Forever the foremost to challenge fate,

Last to retreat, when victory is denied,

Still cannot save themselves from the state

Of captivity, in your blind prison tied.

Others, in arts and learning, who should be

Shining lights, you drown in obscurity.

What shall we say of some noble lady,

That harder, and less prone to yield, appears

Than marble columns, in her constancy,

Despite her lover’s charm and worth, and years

Of service, when foul Avarice we see,

Work such, that she, enchanted, free of fears,

In a moment, without love (who’d believe it?)

Falls prey to some old brute (who’d conceive it?).

Not without cause, do I express my pain;

Understand me who can, myself I know;

I’ve not strayed from my task, I maintain,

Nor have forgot the drift of my canto,

For no less do I apply this sad refrain

To what I’ve said than what I have to show;

Thus, I turn to the tale of our brave knight,

That was about to taste the wine’s delight.

Canto XLIII: 6-8: Rinaldo declines to drink

As I said, Rinaldo paused, thoughtfully,

Ere drinking, undecided in his mind,

Saying, to himself: ‘A fool, I shall be,

If I seek what I’d give all not to find.

She’s a woman, therefore full of frailty,

So let her not be jealously maligned.

Trust ever brought me joy, and joy shall bring;

What joy requires the heart to prove a thing?

Such can bring little good, yet greater woe;

Our Lord himself scorned every temptation.

Whether tis wise or foolish, I’ll not know

More than I need to, nor chance vexation.

I’ll put the enchanted cup from me, so,

And would, and will, decline the invitation,

Which is prohibited by God, as surely

As our first father’s plucking of the tree.

For as Adam, eating of the apple so,

(A thing that the Lord forbade, expressly)

Fell from a state of grace to bitter woe,

Afflicted, from that hour, with misery,

So, the mad husband that would seek to know

What his wife may say or do privately,

Falls out of happiness, to grief and pain,

Ne’er to be free of either, I’ll maintain.’

Canto XLIII: 9-10: The host prepares to tell his tale

Pushing the hateful cup away, Rinaldo,

On so deciding, saw, to his surprise,

A copious stream of tears begin to flow

Forth from his gracious host’s mournful eyes,

Who said, once he had reined in his sorrow:

‘Cursed be he who tempted me, likewise,

To seek such proof, alas, and so tempt fate,

Whereby my dearest spouse was lost, of late!

Would I had known you, sir, ten years ago,

And benefited then from your counsel,

Before I knew such bitter grief and woe,

These eyes, half-blind, from which the tears e’er well;

But now the curtain shall be raised to show

The source of all my pain, and what befell.

The headings and the argument you’ll find,

All the torment that afflicts my sorry mind.

Canto XLIII: 11-16: The origin of the palace

Past a neighbouring city, came you here,

Through which flows a river, the Mincio,

Surrounded by a lake, whose waters clear

Extend, to merge then with the River Po.

The Mincio from Lake Garda doth appear;

While Mantua was built, as all men know,

When Thebes was destroyed; there I was born,

Of noble line, though of all riches shorn.

Though Fortune took but little care of me,

Denying me wealth, at my birth, Nature,

Granting, instead, a certain grace and beauty

Made me the equal of any creature.

And, in my youth, many a maid and lady

Was enamoured of my face and figure.

For with my grace went a courteous manner,

Albeit one should praise oneself never.

A wise man dwelt in that place, in those days,

Whose knowledge of every science was great,

And when his eyes closed on Phoebus’ rays

He’d lived a hundred years and twenty-eight.

Alone, uncivilised in many ways,

He’d lived, until with gifts, urged on by fate

And love, he seduced a married lady;

That then bore him a daughter, secretly.

And to keep the child from that error

The mother had made, who for pure gain

Had bartered her chastity, that ever

In worth exceeds all that Earth doth contain.

He fled the paths of corruption, with her,

And, in the loneliest place, he was fain

To build this palace, with a demon’s aid

And sundry spells, and lived here with the maid.

Chaste and aged women reared the daughter.

She grew to possess a peerless beauty.

And had no contact but with her father,

As far as men were concerned, the while he,

To give her patterns to follow thereafter,

Had pictures and statues made, solely

Of fair women who’d behaved modestly,

And kept from doing aught illicitly;

Not only of those, of sovereign virtue,

That adorned antiquity, and whose fame

Is preserved by history, wherein we view

The qualities and manners of those same,

But, also, those that would in ages new

Serve to beautify our Italy; each such dame

Was represented, each true to Nature,

Like these eight that about the fount do feature.

Canto XLIII: 17-19: The marriage and the quarrel

When the old man deemed her ripe to wed,

So that the fruits might be gathered, he

By mischance, or by ill fortune, was led

To deem myself worthier than many.

Land beyond the city wall he granted,

Streams rich in fish, fields, and open country,

For twenty miles around, the earth and water

He gave me for a dowry, with his daughter.

She was so accomplished, and so lovely,

Naught but herself did she need to bring.

She stitched and embroidered so sweetly

She outdid Minerva; if she did sing,

Walk, play, the viewer, hearer, simply

Thought her a heavenly not mortal thing,

And in the liberal arts she was, moreover,

Almost as learned as was her father.

To her intellect, and equal beauty,

That might have melted the hardest stone,

A loving sweetness, more than mere duty,

Was conjoined, that to think on makes me groan.

She found no greater, joy it seems to me,

Than to be with me, the two of us alone,

For many a day we lived thus, without strife,

Then quarrelled, for I sinned and not my wife.

Canto XLIII: 20-23: The host is loved by the enchantress Melissa

My father-in-law had been dead five years

Since we two had tied the conjugal knot,

When this affliction began, this well of tears,

This sorrow I yet feel, that is my lot.

While the love, of her I praise to all ears,

Yet blessed me, all her virtues I forgot.

A noble lady, of Mantua’s fair city,

Desired my love; none more ardent than she.

All charms, and all enchantments, she knew,

More than ever mage could command at will.

Black night she lit, the day could darken too,

And move the Earth, or make the Sun stand still.

Yet could not make me love her, to speak true,

For I could not grant her a remedy,

Without causing my sweet lady injury.

And though she was noble, and passing fair,

And though I knew that she loved me deeply,

And though many a gift revealed her care,

And though she begged love of me, endlessly,

Not the smallest spark of love had I to spare,

From the flame my first love had lit in me;

While the knowledge of my wife’s faithfulness

Prevented aught that might cause her distress.

The hope, the sound belief, the certainty,

That my wife would be ever true to me,

Should have made me scorn the other’s beauty,

(As great as Helen’s, Leda’s daughter, surely)

And those gifts and charms (offered Paris equally,

Ida’s shepherd, by those goddesses three).

But rejection of her pleas was all in vain;

She did e’er, on her side, the suit maintain.

Canto XLIII: 24-31: Who seeks to shake his faith in his wife

Meeting me, one day, a mile from this place,

This enchantress, whose name was Melissa,

Knowing she possessed the time and space,

Found a way to disturb my peace forever.

Spurred on by jealousy, she sought to chase

The firm faith I possessed, as a true lover,

From my heart, first praising my loyalty

To one who had e’er seemed loyal to me:

“But that she’s truly such, you cannot say,

Unless you first see proof that it is so;

If she errs not, where’er she could essay,

Why, then you can believe, and claim you know.

But if she’s never absent for a day,

Ne’er sees another man, and may not go

Abroad, is not your confidence misplaced,

When you firmly declare that she is chaste?

Go forth awhile; leave the house and go,

And let the fact be known then, far and wide,

That you are gone from home; let all men know

That she remains there, all alone, inside.

If pleas fail to persuade her, or a show

Of gifts (her seeming faithfulness belied)

When acceptance could likely be concealed,

Why, then her faithfulness might be revealed.”

With these words, and the like, the enchantress

Wrought upon me, until I would be gone,

And, from a distance, banish the mere guess

And prove my loving wife a paragon.

“If I accept,” I cried, “and here confess,

That I may hold to some false opinion,

By what sure means can I ascertain

Whether she’s true, or will a lie maintain?”

“I’ll give you, to that purpose,” said Melissa,

“A drinking-cup, with virtue strange and rare,

One wrought by Morgana, that King Arthur

Might test the truth of Guinevere the Fair.

He whose wife is chaste may drink, but never

Can he, whose wife is not, its contents share,

For when the wine he’d taste in his mouth,

It sprinkles o’er his chest, he knows but drouth.

Before we part, then you that test must try,

And, as things are, then deeply you shall drink,

For as yet it seems her loyalty’s no lie,

And of such you’ll have proof, or so I think.

Then, if you return and seek again, say I,

To prove her, and sip thus, at the brink,

And it spills not, and she is as you said,

You’re the luckiest man that ever wed.”

I accepted the offer; thus, received

The enchanted cup, and met with success;

For my wife proved as chaste as I’d believed,

Her virtue confirmed, and her faithfulness.

Then Melissa said: “Depart, leave her deceived

As to your intent, for a month, no less,

And then return, and take the cup again,

And find if you may drink, or see all plain.”

I found it hard to leave my wife, and go;

Twas not that I doubted her loyalty,

But twas the thought that made me suffer so

Of not seeing my wife there beside me.

Then Melissa said: “Another means I’ll show

By which to prove this, of a surety.

Your voice and appearance I shall alter,

And you’ll approach her as someone other.”

Canto XLIII: 32-35: Melissa alters his form to that of his wife’s suitor

The River Po, twixt threatening horns, defends,

The nearby city, Ferrara, with its flow,

Whose jurisdiction to the coast extends,

Where the murmuring tides sweep to and fro.

It yields in age, but in its wealth contends

With its neighbours, and in resplendent show,

To a Trojan scion owing its foundation,

And surviving Attila’s vile invasion.

A rich, and youthful, and handsome knight

Holds the reins of that realm in his hand,

Who following, one day, his hawk in flight,

Entered my stronghold; there the bird did land.

He was entranced by my wife, at first sight,

Such that his thoughts her image did command.

Nor did he cease to practise upon her,

To bend her to his will, as her fond lover.

She’d so often rejected his pleas before,

That at the last he failed to gain his end.

But the memory of her beauty, Amor

Engraved upon his heart, you may depend.

Melissa altered my shape, and did ensure

That his voice and form to me she did lend.

For she transfigured me (I know not how)

In speech and face, and hair, and eyes, and brow.

I, deceiving my lady into thinking

That I’d departed for some Eastern shore,

Once changed, in all aspects of my being,

Returned, in that sure disguise, once more,

With Melssia beside me, by her seeming

My page, that most costly items bore,

(For she her own form had thought to alter)

Gold and gems, from India, and Eritrea.

Canto XLIII: 36-40: His wife is compromised

Knowing every passage, I made my way,

With Melissa at my side, to the chamber

Wherein my wife was like to be that day,

And found her alone; no maid was with her.

I made my plea to her, then put in play

The gold and such, to her those gems did offer,

Emeralds, rubies, diamonds, worked with art,

Such as might sway even the firmest heart.

Twas but a fraction of the gifts, I told her,

Which she might hope to receive from me,

And then, her husband’s absence did proffer

As a reason not to scorn my company.

I promised I would love her forever,

And would cherish her, as she could see.

And that my love and constant faithfulness,

Should be rewarded with her love, no less.

At first, she was utterly confounded,

Blushed rose-red, and would not hear a word,

But, by that gold and those gems surrounded,

Came to see her resistance as absurd,

And, briefly and quietly (I, dumbfounded!)

Said what robbed me of my breath, when I heard

That whate’er I desired, she would do,

Just as long as no one else ever knew.

Her words were like a dart dipped in venom,

By which I felt my very soul pierced through,

A chill pierced me to the marrow, seldom

Has my voice so failed me; the mage withdrew

The veil of her enchantment; stricken dumb,

I was returned to my former shape, anew.

Think of the colour my wife’s face did claim,

Caught, thus, agreeing to an act of shame!

Both of our faces now turned deathly pale,

We both stood silent, and with downcast eye,

So powerless my tongue it could but fail

To speak, and faint at last was my sad cry:

“You would betray me then, but to avail

Yourself of that which shames us both thereby?”

She gave no answer, though her tears did speak,

That, streaming from her eyes, her breast did seek.

Canto XLIII: 41-46: And flees him for the other

Her shame was great, her indignation more,

Because I had, thus, caught her in the act.

It increased then from what it was before,

Till it turned to wrath and hatred at the fact.

She chose the other, swiftly sought the shore

Of the flowing river, though darkness lacked

But an hour or two; in a barque she fled,

Through the twilight, and to his realm she sped,

With the dawn, presenting herself before

The knight who was in love with her, whom I

Had feigned to be, when I his semblance wore

And tempted her, my honour shamed thereby.

To one that loved, and loves her evermore,

You may believe her presence pleased the eye.

From there, she said no hope I should maintain

That she’d love me, nor e’er be mine again.

And, alas, with him she is content to stay,

Takes her pleasure, and makes a jest of me.

Of the evil I brought on myself that day

I languish, and am troubled, endlessly;

My sorrow grows; tis right I fade away.

And little, indeed, there now is left of me.

I believe within the year I must have died,

But for one sole comfort, on which I relied.

My solace is that each and every guest,

That, for the last ten years, have lodged with me

(For I’ve offered every one the self-same test)

None but has drenched his chest; good company

I keep, for I’m no different than the rest,

Which somewhat eases my sore misery.

You are the only one that’s proven wise,

By refusing that perilous enterprise.

My wish for knowledge, passing every bound,

Seeking to know what every spouse would know,

Means that no peace I have, none may be found,

Whether life is short or long, time fast or slow.

Melissa was pleased at first to see me crowned

With horns, a short-lived joy, for, in my woe,

Deeming her the cause of my bitter plight,

I loathed the witch, and drove her from my sight.

Angered, at being treated with disdain,

(By one that she loved more than life, she said)

Where she, indeed, had thought to dwell and reign,

(Now her rival was gone) in my wife’s stead,

Scorning to dwell where aught might cause her pain,

Was swift to follow where her fate now led.

And has so far abandoned this country,

No news of her is e’er conveyed to me.’

Canto XLIII: 47-49: Rinaldo condemns the whole affair

Such was the tale his host told Rinaldo,

And when he’d reached the end of his story,

The latter, contemplating his host’s woe,

Gave this reply, touched, it seems, by pity:

‘Ill, indeed, that Melissa counselled so,

And made you stir the wasps’ nest; equally,

Little wisdom had you, who poked around,

And found what you’d gladly not have found.

If your wife was so possessed by avarice,

As to be induced to break faith with you,

Small wonder; she’s not the first, I promise,

Nor will she be the last one so to do.

For stronger minds have done far worse than this,

Though a lesser prize they sought to pursue.

Many the men we’ve heard of that have sold

Their masters, or their dearest friends, for gold!

For you never should have tempted her so,

If you wished her to offer some defence.

Know you not that steel or stone are of no

Avail, the draw of gold is e’er immense.

The failure was yours, as now the woe,

In testing her, when the consequence

Bore such weight; no doubt you’d have fared far worse,

If your wife had sought the like to rehearse.’

Canto XLIII: 50-55: He boards a boat and heads for Ferrara

Rinaldo ceased and, as he did so, rose,

And said he sought a bed until the morn,

Or rather he’d sleep awhile, but chose

To leave an hour or two before the dawn,

Since but little time had he for repose,

And, indeed, none could he spare, he’d be sworn.

And his host said, in truth, if that would please,

He might rest there within, all at his ease.

For he’d prepared a room there, and a bed,

But, if he’d take his sound advice, he might

Advance for many a mile, and be sped,

While yet enjoying his rest, through the night.

‘For you can take to a boat,’ his host said,

And progress with the river in its flight,

As it makes it way through our country,

And so, gain half a day on your journey.’

Rinaldo was pleased with the offer,

And thanked his host most courteously,

Then made for the mooring on the river

Where the vessel was waiting, which promptly

Departed. There, at ease beneath a cover,

The knight was carried down the stream swiftly.

Six light and slender oars drove the boat,

And, like a bird on the wing, it did float.

He was asleep ere he laid down his head,

Having told the men to wake him as soon

As they neared Ferrara, for as he said

If they failed to, he might well sleep till noon.

They passed Melara on the left, as they sped,

Then Sermide on the right, neath the moon,

Ficarolo and Stellata they passed by,

The fickle river dividing nearby.

Of the two arms, the helmsman took the right,

Leaving that which flowed to Venice behind,

Passing Bondeno, as the morning light

Flowed from the east, the dark hills outlined.

And now Aurora all her crimson and white

Fair blossoms to the glowing sky consigned.

Rinaldo awoke, raised his head, and lo,

He saw the twin forts built by Tealdo.

‘O most fortunate Ferrara!’ he cried,

‘Of which my good cousin Malagigi

(The stars and wandering planets having spied,

And forcing some sprite to appear promptly)

Viewing the future centuries, prophesied

(When I accompanied him on a journey)

That you shall prove the pride of Italy,

And men shall set no bounds to your glory.’

Canto XLIII: 56-59: Malagigi’s prophecy of Ferrara’s future

So, he exclaimed, and forever rushing

Along, as if with wings the vessel flew,

Down the king of rivers swiftly passing,

Till the isle, nearest the walls, came in view;

And though it was devoid of any being,

He was pleased to see it, and joyed anew

That in after times that isle would be fair,

Adorned, and beautified, by many an heir.

At other times, on the road, he did hear

From Malagigi, that when to Aries

The Sun had returned in his fourth sphere

Seven hundred times, in all the wide seas,

And lakes and rivers, no isle would appear

More beautiful, or more suited to please,

And none who saw it would seek to speak more

Of that isle where Nausicaa trod the shore.

He heard that its palaces would outdo

Capri, that Tiberius held so dear;

The Gardens of the Hesperides too

Could but yield in beauty to those found here.

Nor to the rare plants, creatures, trees on view,

Would Circe’s have compared, it would appear.

While there, with the Loves and Graces, Venus

Might dwell, no more in Cnidos or Cyprus;

And its prince would, with study and with care,

Joining, to his knowledge, will and power,

Would thus the Belvedere fashion there,

Circling the place with moat, and wall and tower,

Until all foreign forces it might dare,

Nor need it call for aid at any hour.

Ercole’s son, Ercole’s father, twould be,

Alfonso, who its building would o’er-see.

Canto XLIII: 60-63: Rinaldo is borne past the city

So, Rinaldo approached it, recalling

The prophecies Malagigi had made,

Those sights, of later times, divining,

The which to him alone he had conveyed.

And marvelling at the place, and wondering:

‘How can it be’ (his amazement displayed)

‘That upon an empty marsh shall flourish

The liberal arts, and most worthy studies;

And, from a little burgh, a town shall grow,

And then a mighty city of great beauty;

And where now all about the waters flow,

Rich farmland will prosper, fruitfully?

Ferrara, even now I rise, and honour show

To that line, the noble love, the courtesy

Of your lords, and all the virtues shown

By your knights and subjects, known and unknown.

The Redeemer’s ineffable goodness,

Your princes’ wisdom and care for justice,

With endless care and love, in happiness

Will preserve you, and abundance promise,

Protecting you from that pain and distress,

Inflicted on others, by your enemies.

Let them be angered by your contentment;

Scorn, yourself, base envy and resentment.’

While Rinaldo mused thus, the vessel ran

Downriver, with the current, at such speed,

No falcon, flying swift as any can,

E’er descended faster, when the call decreed.

The right branch of the right arm they began

To navigate, and watched the walls recede,

San Giorgio fell behind the parting boat,

The turrets of Gaibana, and the Moat.

Canto XLIII: 64-67: He muses upon the tale he has heard

Our knight, as one thought led to another,

Recalled his host of the previous eve,

In whose palace he’d dined, and who, ever,

Was in pain and woe, and scorn did receive

From that city, from his wife, and her lover,

More pain and woe than any could conceive.

And of that cup he was obliged to think,

That revealed all, if one sought to drink.

And at the same moment he remembered

What his host had said: of all that had tried

To sip from the cup, none had succeeded

In drinking, but had spilt it far and wide.

Now he repented, now: ‘Had I conceded,’

He thought ‘no joy could in my heart abide;

Succeeding I’d but have proved my belief,

While failing I’d have brought myself to grief.

Since my faith in my wife is most certain,

Naught could amplify that belief in me.

And had I put it to the test, tis plain,

It could ne’er produce greater certainty.

Yet the evil would be great, I maintain,

If I saw of Clarice what I would not see.

That were a bet best not laid, where one

Might lose all, and yet little could be won.’

While the knight of Chiaramonte was musing,

Never raising his two eyes from the floor,

The helmsman, seeing him thus pursuing

His thoughts (and gazing at him, not the shore),

And wishing to know what he was thinking

And what occupied him so, sought therefore,

Being bold and well-spoken, to stir him,

And to hold some conversation with him.

Canto XLIII: 68-70: Then enters into conversation with the boatman

The substance of their pleasant colloquy,

Was this: a spouse had little common-sense

Who set out to test his wife’s loyalty,

And yet gave her little chance for defence;

Though a wife, armed with simple modesty,

That scorned the lure of wealth, howe’er immense,

Would be proof gainst a thousand swords of steel,

And scorching flames, having naught to conceal.

The boatman agreed: ‘Tis true, as you said,

He should ne’er have proffered gems and gold.

From such temptations, although she be wed,

Not every woman can her hands withhold.

I know not if you’ve heard or may have read

Of the spouse (elsewhere the tale may be told)

That his wife in the act, did espy,

For which she should have been condemned to die.

Your host should have kept in memory

That all resistance yields to gold’s allure,

But he forgot when he needed to, you see,

And so brought sorrow to himself, and more.

Had he only recalled the deed, like me,

Done in that city that lies on the shore,

(His and mine) of the marshes and the lake,

Where Mincius its sluggish course doth take.

Canto XLIII: 71-74: The tale of Adonio

‘Tis of Adonio I wish to tell,

That on a judge’s wife a gift conferred

By means of a dog.’ ‘Whate’er thus befell,

Is known among you only, I have heard

Naught of it beyond the Alps, it may well

Be unknown in France, for not a word

Of it did I hear there: come, tell the tale,

And I shall listen closely, without fail.’

The boatman thus began: ‘Twas in Mantua,

One Anselmo dwelt, of high family,

His youth spent in flowing gown, forever

Studying Ulpian; who chastity,

Lineage, beauty sought to discover,

In some bride who’d enhance his dignity.

One he found in neighbouring Ferrara,

Of more than mortal beauty, and wed her.

Now, she was of such manners and such grace

That everything seemed love and lightness there,

More perchance than seemed fitting for his place,

Or that might leave a husband free of care.

Once wedded, his jealousy grew apace,

More than in any man that breathes the air.

And yet she gave no cause for jealousy,

Except that she was shrewd, and a beauty.

In Mantua too, lived a knight, who came

Of an ancient and an honourable line,

Sprung from the serpent’s teeth, the very same

House as Manto’s, who that city of mine

Was destined to found; tis known to fame,

And midst the others shall forever shine.

And this bold knight was called Adonio,

That loved the lady, and his love would show.

Canto XLIII: 75-77: Impoverished, he leaves his native Mantua

And he, to pursue his amorous quest

Began to spend his riches lavishly,

Gave many a feast, in rich garments dressed,

And did whatever seemed to him most worthy.

Had he of Tiberius’ wealth been possessed

He’d yet have exhausted it completely.

For I think that ere two winters were past,

His paternal fortune he’d run through at last.

The well-lit house that many did frequent

From morn till eve, filled with his many ‘friends’,

Was empty, now his money was all spent,

And he without the means to serve their ends.

The feasting done, all from his table went,

But for the beggarly few; to seek amends

He thought to leave the city, and to go

Wherever none his name or face did know.

With this intention, he set out one morn,

Told not a soul, on not one ‘friend’ did call,

With many a tear and sigh, all forlorn,

To cross the marsh beyond the city wall.

Yet, to the lady was his heart still sworn,

He forgot her not, forever in her thrall.

Behold, with high adventure he now met,

One destined to reverse his fortunes yet.

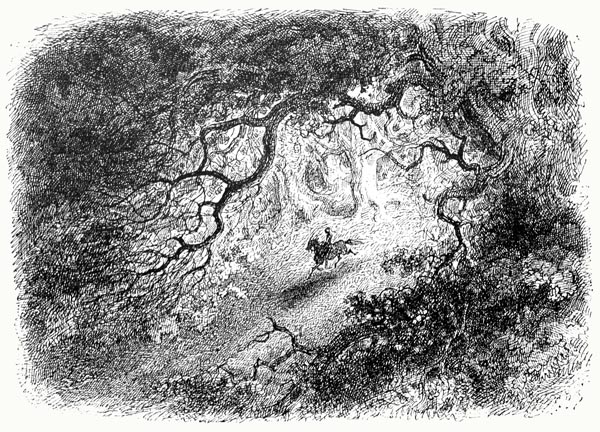

Canto XLIII: 78-81: Meets with an adventure, and years later returns

He saw a peasant who beat, with a heavy stake,

The tangled bushes, growing all around.

Adonio did question of him make,

As to the man’s purpose, and thereby found

That within he’d spied a most ancient snake,

That slithered there, over the marshy ground.

A longer and a thicker serpent he

Had never seen before, nor thought to see.

The peasant said he’d not depart the place

Until he’d caught and killed the evil thing.

At this, Adonio, with angry face,

Rebuked the man, his impatience showing,

For serpents were e’er revered by his race;

They bore a snake as emblem, recalling

That their ancestor had issued (twas known)

Forth from the serpent’s teeth by Cadmus sown.

He said and did to the fellow what deterred

Him from pursuing that aim, in any guise,

Leaving the serpent free, as he preferred,

To go its way unharmed, hid from all eyes.

And, journeying where none of him had heard,

He dwelt in deep obscurity likewise,

Living far from this land, so it appears,

For a space of more than seven long years.

Neither distance nor straightened circumstance

Made Love, that ever occupies the mind,

Grant him rest; he recalled her form and glance,

That stirred his heart, and his feelings did bind.

Thus, at last, he returned, and not by chance,

For the beauty he had lost he yet would find.

Unkempt, ill clad, still troubled to the core,

He sought the road to Mantua once more.

Canto XLIII: 82-85: Anselmo is to go on an embassy to Rome

At this same time, an embassy was sent

To the Papal See, and at Rome would stay

(To complete its mission, and win consent

For its aims) for how long none could say.

Anselmo, their number would augment

(He ever would repent that fateful day!)

Though he promised, prayed, and bribed, he must go,

And at the end he yielded; to his woe.

It seemed to him no less cruel and bitter,

This matter that caused him so much grief

Than if some creature at his side did hover

And plucked at his heart-strings; for scant relief

Could he find from Jealousy; forever

Paling his cheek, for twas his sad belief

His wife would stray, thinking her but frail,

And so, he begged her to be true (to no avail!)

Not beauty, birth, or fortune would suffice

He told his lady, to maintain her honour,

If she failed in chastity, repeating twice

That the prize to be won was ever greater

Where virtue proved strong against all vice,

And now his long absence she must suffer,

And so, a wide field lay open surely

Wherein men might win her from loyalty.

With such exhortations, and many more,

He encouraged the lady to be true,

This journey his lady could but deplore;

Heavens, what tears, what sorrow did ensue!

Sooner would the sun turn black, she swore,

Than she should cease his counsel to pursue.

She’d not break her faith, she would expire,

Rather than pander to some base desire.

Canto XLIII: 86-89: A mage prophesies that his wife Argia will be seduced

Though to her promises and abjurations

He lent belief, such that his fears grew less,

He could not rest from his lamentations

Till better assured of her faithfulness.

He had a friend, prized for his predictions,

That could see men’s future ruin or success;

For of every science, every magic art,

He knew the secrets, or the greater part.

He asked him, ere he took his departure,

To determine if, while he was away,

His wife, whose name, indeed, was Argia,

Would be true to him, or be like to stray.

Swayed thus, by his pleas, the astrologer,

Plotted the orbs’ positions day by day;

Anselmo left him to his work, and came

Upon the next morning, to learn that same.

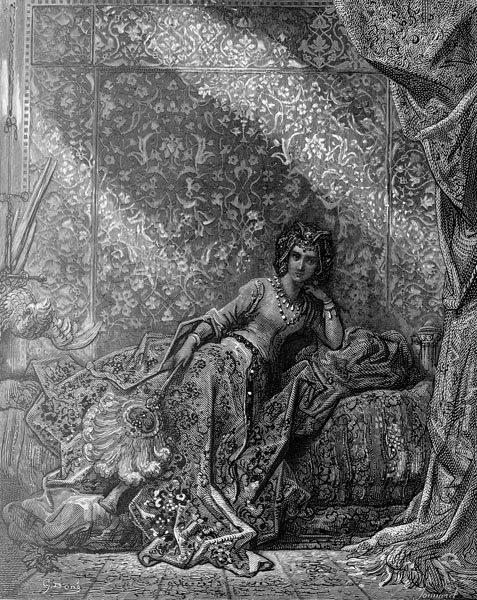

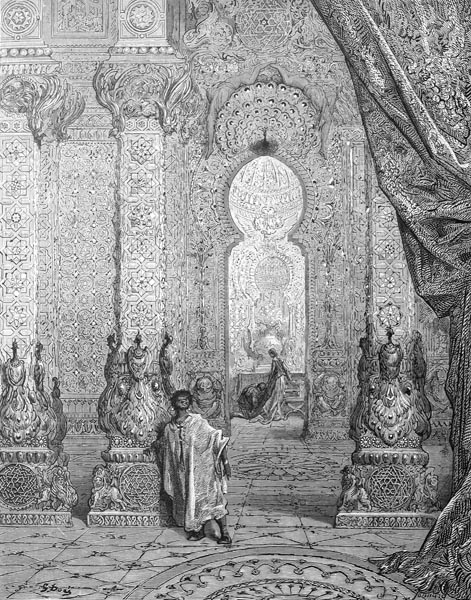

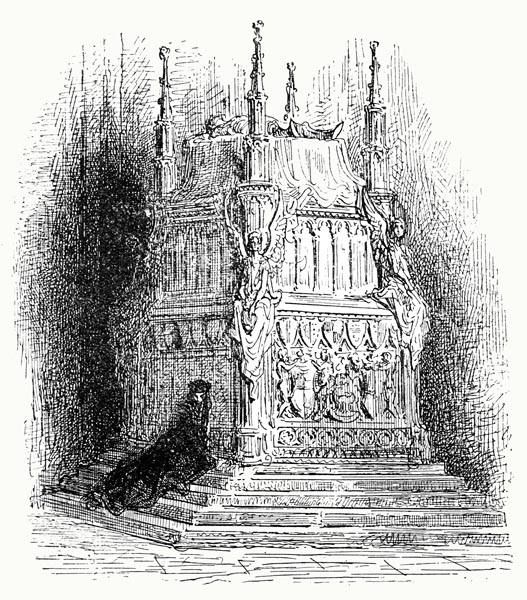

![Ariosto - Orlando Furioso - Canto XLIII: 86 [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Italian/interior_ariosto_orlandofurioso_cantoxliii86b.jpg)

The mage was silent, not keen to display

Such results as might cause his friend much woe,

And with many excuses sought delay,

But, since the spouse declared that he must know,

Revealed that the wife was like to betray

His trust when he left, or it seemed so.

She’d not be won by beauty, he was told

Or lover’s pleas, she’d be seduced by gold.

When to his first fears, the threat was added

One written in the stars, and thus foreseen,

You’ll know, if on Love’s mysteries you’ve fed,

How stood his heart: it stood not well I ween.

And, midst the woes that hung above his head,

One grieved him most; the knowledge twas, I mean,

That by avarice she’d be won (and lost)

Her chastity thus purchased (to his cost).

Canto XLIII: 90-94: Anselmo transfers use of his wealth to her and departs

So, to prevent his wife, as best he could,

From falling into such grievous error,

(For a man will sometimes seek the good,

By disposing of the riches on his altar)

All the wealth he had (and be it understood

He was no pauper) he transferred to her,

The rents and produce, all that he possessed

He gave her, all with which he then was blessed.

“Yours is the power,” he said, “to buy and spend,

And you may do the like without measure,

Consume or waste, give, acquire, or vend,

Just as you wish, according to your pleasure.

If I but find you faithful, in the end,

I shall take no account of my treasure,

Stay but as you are now, you understand,

And you may e’en dispose of house and land.”

He begged her, till he was again beside her,

Not to spend her weary days in the city,

But in their most pleasant country villa,

Where she might live more comfortably.

This he said thinking to keep her ever

From those who might corrupt her easily;

Fearing not the humble shepherds, or those

That tilled the fields all around (one must suppose).

Argia, her fearful spouse embracing,

Her sweet arms about his neck, was I fear

So distressed that her tears, overflowing,

Like two glittering fountains did appear.

She was grieved at her husband for showing

That he thought she was suspect, far or near,

While his suspicion’s source was no less

Than his lack of faith in her faithfulness.

It would take too long, if I sought to tell,

Of the tenderness of their last goodbyes,

“I commend my honour to you; farewell.”

He cried out, she yet with tears in her eyes.

And he felt a fond tear or two, as well,

As he wheeled his steed, falling from his eyes.

Her gaze long followed him, as on he rode,

While o’er her cheeks the streams of tears flowed.

Canto XLIII: 95-102: Adonio is visited by the shade of Manto

Meanwhile, the pale, unkempt Adonio

(As I have said before) made his way

Towards Mantua, hoping none would know

His face, and to his entry there cry nay.

Across the marsh, near the city, he did go,

Where he’d defended the serpent that day.

Which had found a refuge, in the wild brake,

From the peasant, who’d sought its life to take.

Arriving there, with the dawning light,

For a few stars still glittered in the sky,

A noble maiden appeared to his sight,

On the brink of the marsh, and to his eye

She seemed alone, a wanderer in the night,

Richly dressed, her rank announced thereby.

She greeted him, in a pleasant manner,

And spoke to him in these words, thereafter:

“Although you know me not, we two are kin,

And I am deep in debt to you, also.

From Cadmus did our lineage begin,

We both share his blood, and I am Manto,

Who first a city from this marsh did win,

That now most fine and splendidly doth show,

And as you may have heard (tis often claimed)

Tis after me that Mantua was named.

Of the faery kind, I am one; and our state,

So that you may understand our being,

Is that we suffer all the ills of fate,

All but the greatest ill, that of dying.

Though to our immortality we mate

An ill nigh-on as vile, and more trying,

For every seventh day our bodies take

On the form (thus, are we bound) of a snake.

To find our bodies sheathed in that vile skin,

And slither o’er the ground, is such an ill,

As none would ever wish upon their kin,

And we curse the fact we are living still.

The debt I owe you, that I would begin

To redeem, requires I tell you, and I will,

That at the time when we that form display,

We are left to countless dangers a prey.

For no creature on Earth is so hated,

As the serpent, and we, in that semblance

Suffer men’s outrage and assault, fated

To be hunted and harmed at every instance,

Unless we can ensure they are frustrated,

By sinking underground at their advance;

Tis better to die than be beaten so,

Thrashed, and often wounded, by blow on blow.

The debt I owe you is that, on that day,

When you passed by the marsh, as you know,

You rescued me from one who sought to slay,

And had dealt me many a painful blow.

If you had not been travelling that way,

I’d not have escaped, not without more woe,

A broken spine or skull, and there have lain

Broken, though destined never to be slain;

For on those days when we must slither for hours,

Clad in that serpent form, along the ground,

The heavens afflict us, rob us of our powers;

They are otherwise by our wishes bound.

At all other times, these virtues of ours

Can make the Sun dim, halt it in its round,

The solid Earth spin backward like a wheel,

And ice take fire, and fire to ice congeal.

Canto XLIII: 103-106: She transforms herself into a dog

Now I am here to pay the debt I owe,

In return for the good you rendered me,

Naught shall you ask in vain, now I go

Free of my serpent form; your poverty

Is ended, for upon you I bestow,

Three times your former patrimony,

Nor do I wish you to be poor again,

For the more you spend, the more shall you gain.

And because you are still tied in that knot

With which Love has bound you, I aspire

To show you the way you may change your lot,

And so, attain the result that you desire.

For, now that her husband to Rome is got,

My counsel you shall take, free of his ire;

At their villa, the lady you will find,

Seek her there; I shall not be far behind.”

She followed by telling him in what guise

He should present himself to the lady,

How he should dress, I say, and speak, likewise,

How he should tempt her, and make entreaty,

And what form she would for herself devise,

For, but for those days when at the mercy

Of her serpent shape, as any creature

She could appear, of whatever nature.

She clothed the knight in a pilgrim’s habit,

Of one who begs for alms from door to door;

She changed herself into a dog, and made it

Of the smallest size, while long hair it bore,

Whiter than ermine; twas for a lady fit,

Fine to see, with many a trick in store.

And in this guise, they went towards the villa,

Wherein dwelt the enchanting Agria.

Canto XLIII: 107-112: The dog’s abilities are revealed

At the farm-hands’ huts, young Adonio

Halted, ere venturing any further,

And on a shepherd’s pipe began to blow,

To which the dog danced, hither and thither.

The lady heard the sounds arise below,

And went to find the source of the murmur,

To the courtyard she had the pilgrim brought,

For from such things Anselmo’s fate was wrought.

There Adonio told the dog to begin,

And the creature obeyed, with canine grace,

And danced the dances that were danced within

Our country, and beyond, at its own pace,

With other tricks as well, and so did win

(For well-nigh human ways it did embrace!)

The admiration of the watchers, with its act;

They scarcely dared to blink or breathe, in fact.

Great wonder that most noble dog inspired

In the lady, then deep longing; her old nurse

She sent to the youth, to say she desired

To purchase it, offering a goodly purse.

“If all the treasures woman e’er acquired,

By her cupidity, it might disburse,”

The wary pilgrim said, “twould fail to buy

A single paw of this fine dog, thereby.”

And to show why what he said must be true,

He took the nurse to a nearby corner,

Instructing the dog, on his given cue,

To summon a gold coin for the messenger.

The dog then leapt, and shook itself anew,

And, lo and behold, produced the treasure!

“Well now,” the youth next placed it in her hand,

“What price the finest dog in all the land?

For whatsoe’er I request, the dog supplies,

Nor am left empty-handed, night or day,

Rare pearls and rings, and aught that I devise,

And lovely garments, if for such I pray.

Tell your lady, she may acquire, likewise

What she wishes, but not for riches, say;

I ask for one brief night to embrace her,

And she may possess this useful creature.”

And then a gem, that moment born, he gave her,

That she might bear it to the lovely lady,

One that, to the nurse, seemed worth a further

Ten gold coins, or perchance even twenty.

Back to her mistress, sped the messenger

And solaced her with the news that surely

The wondrous animal might yet be bought

By a simple gift, that would cost her naught.

Canto XLIII: 113-116: Argia succumbs and her husband returns

Argia, at first, proved most reluctant,

Partly due to her vow of faithfulness,

Partly too she doubted, in that moment,

All the claims that the other did express.

The nurse tried all, persuasion and lament,

Saying seldom did rare fortune so bless

The folk on this Earth, and gained consent

To bring the youth, next day, so she might see

The dog’s fine tricks, in perfect privacy.

The next appearance Adonio made

Was but death and ruin to Anselmo,

For gold coins, on demand, were soon displayed,

And strings of pearls, and jewels in a row.

Her proud heart was tamed, the young man made

A great impression too; she’d not say no

To him who’d made the offer, when she saw

Twas the Mantuan who’d wooed her before.

The wicked nurse’s efforts at persuasion,

The pleas, and the presence, of the lover,

The chance offered by this rare occasion

When her jealous husband was far from her,

With small risk of any accusation,

Soon led her to embrace the knight’s offer.

The dog was hers, all chaste thoughts overcome,

And she led Adonio to her room.

The knight reaped in full the fruits of love

Lying with the lady, whom the faery,

Felt affection for, and did so approve,

She chose to dwell there continuously.

Through all the Zodiac the Sun did move

Ere the justice arrived home, finally,

Fear and suspicion running in his head,

As to all the astrologer had said.

Canto XLIII: 117-120: Anselmo attempts to learn the truth

Once arrived, his first instinct was to fly

To the man’s abode, and of him demand

To know if his dear wife had sought to lie

With any, or had honoured his command.

The astrologer consulted charts and sky,

To see how might the Sun and planets stand,

And sent to say that as he had foreseen,

So, he could now confirm, events had been:

That, tempted by the rarest present, she

Had fallen prey, yes, to another man.

This grieved the judge, and wounded him sorely.

Sharp lance nor spear so pierce; and so, he ran

To find the nurse and know with certainty

(Although he credited the starry plan)

What had occurred: he drew the nurse apart,

And plied his questions with a lawyer’s art.

He circled widely all about the question,

While hoping of the truth to find some trace,

And at first learnt naught worthy of mention,

However hard he cared to sift the case.

For being used to countering aspersion,

She met his claim with an immobile face;

And, so instructed, till the month was out,

Left him hanging twixt certainty and doubt.

How good would doubt have seemed to Anselmo,

If he’d known the grief certainty would bring!

When he learnt, by pleas or gifts, there was no

Shred of fact the nurse would yield, not a thing,

Sounding no chord that rang true, to his woe,

He chose, as one ever used to biding

His time, to wait till she angered his wife,

Thinking: where’er women are, there is strife.

Canto XLIII: 121-124: Does so, and orders the death of his wife

He waited, and there came the thing he sought,

For at the first rebuke, the nurse appeared

And news of all that had occurred she brought,

And nothing she held back; twas as he’d feared.

Twould take long to tell how he was fraught,

And how his heart sank, whene’er his wife neared.

The wretched judge was so by grief oppressed

Of his wits he was well-nigh dispossessed.

Conquered by ire, he was disposed to die,

But first resolved to see his wife struck dead,

Clear her from shame, himself from grief, thereby,

The witness a sharp blade stained crimson-red.

To the city he went, with wrathful eye,

Stung by fury, the thought lodged in his head,

And to the farm despatched a loyal man

Whom he ordered to execute the plan.

He sent the servant speeding to the villa,

Who was told to say his master was laid low,

With such a fever, he’d have Argia

Come to him, for his fate was touch and go.

Unaccompanied by any other,

She must hasten to him, her mercy show

(He believed she would come, without delay);

Then the man must cut her throat on the way.

The servant thus ran to find Argia,

Prepared to carry out his lord’s command,

Though her little dog now barked to tell her

That her fate might lie in this servant’s hand.

Its manner told her she was in danger,

But she felt she must go, you understand,

For he had cared for her, in word and deed,

And she ought to bring aid in time of need.

Canto XLIII: 125-129: The lady vanishes

Now, the servant turned aside from the road,

And went by strange and solitary ways,

And took a path to where a river flowed

(From the Apennines to the Po it strays).

Amidst a dark and gloomy wood, it showed,

Far from farm and town lay that forest maze.

It seemed a silent and secluded place,

Fit for the cruel task he now must face.

He drew his sword, and to the lady said

That she must die, such was his lord’s decree,

And she should pray, before he struck her dead,

To be cleansed of her sins. Suddenly

I know not how, she vanished (and so fled)

Just as he thought to slay her wickedly,

He saw her not, searched all the woods around,

But not a trace of Argia he found.

Filled with shame, he then returned to his lord,

With a bewildered look, and sore dismayed,

And all the tale to his master did afford,

And that he’d sought her all about the glade.

The judge knew not that Manto did accord

His wife such powers, and her escape did aid,

Because the nurse, who all else had revealed,

That useful fact, I know not why, concealed.

He knew what to do; he thus had failed

To exact revenge for all his pain and woe,

What was a mote was now a beam; he paled,

It weighed upon him, and oppressed him so.

Of her error, concealed before, or veiled,

Every fool about, he feared, soon would know.

He might have hidden the truth from them all,

But that power he’d now lost beyond recall;

For he well-knew that his treacherous heart

He had shown to his wife, by his vile deed,

While she to escape him, would flee apart,

And run to some great lord in her sore need,

One that would hold him to scorn, for his part,

And deride him that her death had decreed;

Or perchance a worse might now command her,

That would act as her lover, and her pander.

Canto XLIII: 130-133: Manto creates a palace for her to dwell in

To remedy the situation, he

Sent messengers with letters, here and there,

Leaving no stone unturned in Lombardy,

Seeking Argia, as hound will hunt the hare.

Then, he went in person through that country,

And he, or his agents, searched everywhere.

Yet no one living there could Anselmo

Discover, who of her refuge might know.

He summoned the servant he’d commanded

To do the deed, who yet had failed him so,

And had him lead him to the place he’d said,

Where she’d vanished in the wooded hollow;

For perchance she roamed the place instead,

And at night retired where none could follow.

The servant led him to that tree-lined shore,

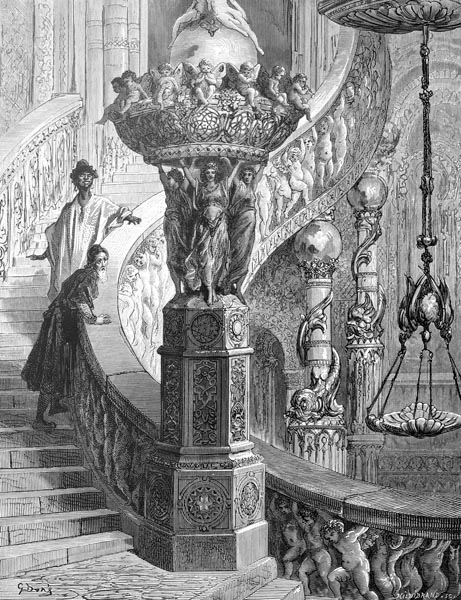

Or thought to, but a palace there they saw.

Manto had wrought it there, for fair Argia,

And laboured swiftly to raise it on high,

An enchanted dome of pure alabaster,

Where, everywhere, gleaming gold met the eye,

No tongue could tell, no mind compass ever

The treasures that within those courts did lie,

Nor its outer beauty; my lord’s great place

Seems a cottage next its splendour and grace.

Costly curtains and Arras tapestries

Richly woven in many a different style,

Decked stable walls, not just its galleries,

And chambers, and halls, for mile on mile.

Gold and silver vases, designed to please,

And gemstones carved in forms to beguile,

(Cups and the like, in azure, red, and green)

And cloths of gold, and silk, adorned the scene.

Canto XLIII: 134-139: Anselmo enters and is compromised by his greed

The judge came to this palace, as I said

Expecting to find only woodland there,

And his eyes well-nigh started from his head,

On discovering a place strange and rare.

He thought his wits were addled when, instead

Of a wasteland, all about him showed so fair,

He thought he was drunk, or it a dream,

For a marvellous enchantment it did seem.

In the doorway to the palace there stood

An Ethiopian woman, with thick nose

And lips, as ugly a sight as one could

E’er see, or e’en imagine, I suppose,

Less fair than Aesop was, tis understood;

Paradise she’d have marred, Heaven knows!

Dressed in beggar’s garb, greasy, dirty,

I could ne’er describe the wretch completely.

There being no other there, Anselmo,

Curious as to who it’s lord might be,

Now approached her, and demanded to know:

The woman said: ‘Why, it belongs to me.’

The judge believed she lied, it was not so,

She’d made the claim by way of mockery,

But the Ethiopian swore that it was hers,

Hers alone, though she welcomed travellers,

And, if he wished, he could view the whole,

Enter, and go about there, at his ease,

And through the corridors, and chambers stroll,

And take aught that him or his friends might please.

Anselmo, since that was his present goal,

Threw the reins to his serving-man to seize,

And, led by her, through each hall and chamber,

From top to bottom, gazed around in wonder.

The architecture, and the artistry

He admired, and the ornamentation,

Oft saying: “The wealth of every country

Would hardly pay for its construction.”

To this his guide replied: “And yet many

A palace has its price, as has this one,

Not in gold and silver, yet, nonetheless,

You may own it for what will cost you less.”

She made the same request Adonio

Had made to Argia the time before,

The justice thought her addled even so;

As ugly was she as a running sore.

Three times denied, she yet besought him though,

And strove so hard to persuade Anselmo

Offering that fair reward to him still,

Until, at last, she bent him to her will.

Canto XLIII: 140-143: Argia appears and they are reconciled

Argia, his wife, in hiding nearby,

Upon seeing him lapsing into error,

Leapt forth crying: “Oh, this deed is worthy,

No doubt, of so great and wise a lawyer!”

Caught in an act of such vile treachery,

You’ll imagine his face, and its colour!

“O Earth (he thought) split now from pole to pole,

And swallow this fool of a husband whole!”

To shift the blame, and shame him, Argia

Piled her reproaches on the poor man’s head.

“What punishment suffices for a lover

Of such vile deeds?” mockingly, she said,

“When you would have slain me, moreover,

For obeying Nature’s urge; to my bed,

Taking a fair and noble knight, who brought

A gift compared to which this place is naught!

If you were prepared to see the end of me,

Then, a thousand times, you deserve to die.

Yet though I have power here, and surely

Could wreak revenge on you, yet, say I,

Naught shall be done to mark your treachery

Though you may seek to rut there in your sty.

But, give and take, my husband; think anew,

And pardon me, as I now pardon you;

Let there be peace between us, and accord,

And let our indiscretions be forgot.

Oblivion to my past faults afford,

As I to yours, and we’ll recall them not!”

It seemed the wisest course to our lord,

Nor was he too unhappy with his lot.

Trust and concord they agreed to restore,

And loved each other dearly evermore!’

Canto XLIII: 144-150: Rinaldo journeys to Lampedusa

So went the boatman’s tale, and Rinaldo

Gave a wry smile at the end of the story.

He’d blushed, indeed, hearing of Anselmo,

As he’d listened somewhat shame-facedly.

He praised Argia’s wisdom even so,

Who’d caught him in her mesh so cleverly,

Netting a bird, that, while about the same,

Was exposed by her, yet incurred less shame.

When the sun rose higher in the sky

He ordered his breakfast to be prepared,

From provisions the Mantuan laid by,

To sustain our knight as onward he fared.

While Ferrara, fell behind, by and by,

With its marshes, to the daylight now bared.

Argenta came and went, that stretch also

Where the Santerno joins the River Po.

The Bastia was not yet built, I deem,

That Spain has little cause to boast of ever,

Where her banner has been raised, it would seem,

That causes greater sorrow to Romagna.

To the right shore, o’er the flowing stream,

They then flew, and, leading to Ravenna,

Followed a stagnant canal, one that soon

Brought them near that city, at nigh-on noon.

Though of gold he’d little to spend freely,

He had enough to reward the boatmen,

And wished to do so, of his courtesy,

Before he left, and went his way again.

Changing his mount and guide, to Rimini

He rode, and passed beyond that town, and then,

In Montefiore stayed, till night was done,

Reaching Urbino with the morning sun.

No Federico da Montefeltro,

No Isabetta, no Guidobaldo,

Francesco Maria, Leonora, no,

None of that line was there, bowing low,

Courteous hospitality to bestow,

For many a night, on brave Rinaldo,

As that House bestowed on every guest,

And do so now, as I can well attest.

Since none there took his rein, our Rinaldo,

Made his way next to Cagli, o’er that height

Where the Metauro, and Candigliano

Carve their way, till no longer on his right

The Apennines lay; onwards he did go

Past Tuscany, and Umbria, to alight

In Rome; from Ostia, sailed to Sicily,

Where Aeneas old Anchises did bury,

At Eryx; and there changed vessel, and so

Made haste for the isle of Lampedusa

That place well-chosen by Orlando’s foe,

(Although the fight was already over).

The ship’s captain, urged on by Rinaldo,

Employed every sail and oar, however,

The winds both strong and unfavourable

Saw them arrive too late, though by little.

Canto XLIII: 151-153: He arrives there after the conflict has ended

He arrived at the point where Orlando

Had completed the great task he’d begun,

Slaying Agramante and Gradasso,

Yet harsh, bloody, had been the victory won.

Brandimarte was dead; Oliviero,

Most sorely wounded, and well-nigh undone,

Languished on the shore, on sandy ground,

Crippled and suffering, with limb unsound.

Orlando could barely restrain his tears,

As he embraced Rinaldo, and related

How Brandimarte had died; for long years

Of friendship their deep love had created.

No less moved was Rinaldo, it appears,

At the sight of that wound, so ill-fated.

And he hastened to embrace Oliviero,

That nursed the wounded foot that pained him so.

He comforted him as best he could, and yet

Could find no comfort for himself, for he

Had arrived not when the table had been set,

But when the feast was done, the board empty.

Meanwhile their squires had sailed (lest I forget)

For Bizerte’s scorched and ruined city,

To inter Agramante and Gradasso,

Bearing the blood-stained corpses of the foe.

Canto XLIII: 154-159: Fiordelisa learns of Brandimarte’s death

Great satisfaction from that victory

Astolfo and Sansonetto derived,

Though the death of their friend Brandimarte

Pierced them through; had the warrior survived

Their hearts had been lighter, certainly,

For, of that valiant spirit now deprived,

Gloom darkened their faces; how best to tell

Fiordelisa, who’d seen all was far from well?

In the dark that preceded this sad day,

She’d dreamed the sable surcoat she had made

That he might go forth in noble array,

Was with bright crimson droplets overlaid,

As if strangely rained upon, one might say,

Or as if tears of blood were there displayed;

It seemed to her that she had wrought it so,

And grieved that thus adorned he must go;

And spoke to herself: ‘My lord commanded

That I should work his surcoat all in black,

Wherefore upon it have these strange drops landed?

Naught like this did he wish upon his back.’

The interpretation her dream demanded

Seemed ill to her; twas that same night, alack,

The news had come to them, though Astolfo

Had concealed it; now he and Sansonetto

Entered where she was; she saw no trace

Of joy upon their faces, naught did show;

And ere a word was uttered in that place,

She knew that they both bore a tale of woe;

She knew Brandimarte heaven did grace,

And with that her poor heart filled with sorrow,

Her sight was clouded, the world spun round,

And she fell, as if struck dead, to the ground.

When life returned once more, she tore her hair,

Scored her cheeks with her nails, called out his name,

Harmed herself, in agony, naught did spare,

Forever vainly summoning that same,

Crying out, as if some raging demon, there,

Possessed her, and madness upon her came,

As the Bacchantes at the horn’s wild sound,

Would race o’er hill and field, and stony ground.

Now she begged whichever yet bore a blade,

To yield it her, that she might pierce her heart;

And now would board the ship that had conveyed

The corpses of his foes, to tear apart

The lifeless flesh, that ill might be repaid,

And vengeance done, and she thus play her part;

And now would sail for that isle, whereby

She might seek her lord and, beside him, die.

Canto XLIII: 160-164: Her lament

‘Ah, Brandimarte,’ she cried, ‘why did I

Let you hasten, without me, to your fate?

Your departures ne’er before did I spy

But I followed, to seek you, soon or late.

I might have helped you, uttered a wild cry,

Seeing the danger come upon you straight,

As Gradasso stepped behind you, and so

Have warned you of the menace from your foe.

Or, perchance, I might have come between,

And, in your stead, received the fatal blow;

My poor head, as a shield, might have been

Some defence; little harm had I done so,

For I die still, and from this death naught seen

That profits you, for I but die of woe;

While, protecting you to my last breath,

How could I e’er have died a truer death?

Even though Fortune had denied us grace,

Averse to aid, and all the heavens, yet

My last kiss might have caressed your face,

My tears your pallid cheeks might have wet,

And ere the angels wafted you, apace,

Towards your Maker, lest you might forget,

‘Depart in peace, my love, await me there,’

I might have cried, ‘that we sweet rest may share.’

Is this then the realm, my Brandimarte,

Whose sceptre you were destined to wield?

How now shall your fair city, Dammogire,

Welcome us, when to death we both must yield?

Oh, cruel Fortune, how you’ve wrought against me,

What hopes you render vain, our fate thus sealed!

Ah, let me cease, since lost is he that blessed

My life, why should I grieve to lose the rest?

Repeating these and other words, the madness

Gripped her once more, and with such fury

That she tore again at every tangled tress

Of her golden hair, and beat more wildly

At her breast, biting her lip in distress,

Bloodying her face, her body weary.

Yet leaving her to weep, consumed by woe,

I must turn to the Count, and Rinaldo.

Canto XLIII: 165-168: The preparations for Brandimarte’s funeral

Orlando with his kinsman, whose kind care

And attention he needed, now gave thought

To the matter of where the two might bear

Brandimarte’s corpse, for a site he sought

Worthy of that knight, to inter him there.

They sailed for Etna, and its fiery court,

The mount that lights the night and darkens day.

Not far north, to starboard, Sicily lay.

With a fresh wind blowing in their favour,

The ship weighed anchor as the evening fell,

The silent goddess lit their path, moreover,

Her shining horn directing them, as well,

And past dawn they lay in gentle harbour,

Near Agrigento, riding with the swell.

Here Orlando ordered, ere the next night,

All that was needed for the funeral rite.

When he had seen his orders executed,

The light of the sun being well-nigh spent,

With many a noble from that place recruited,

To Agrigento, the two warriors went,

The shoreline lit with torches; well-suited

Was that sanctuary, loud their lament,

Where the Count would leave his valiant friend,

Whom he had loved, loyally, to the end,

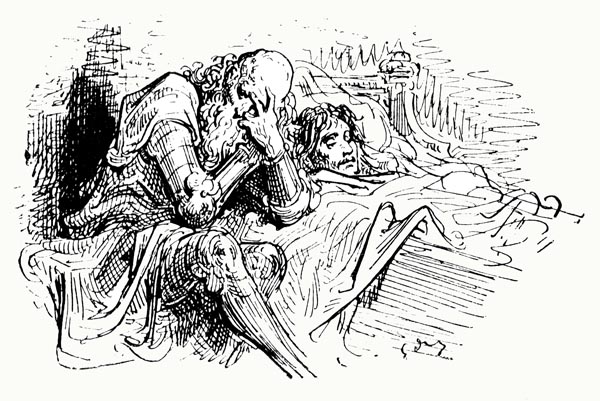

Bardino, bowed down by the weight of years,

Stood weeping o’er the sad funeral bier,

That aboard ship had cried so many tears,

He’d well-nigh wept away his sight, I fear.

Calling the heavens cruel, the starry spheres,

Like an old anguished lion, he did appear;

Pawing there, rebelliously, within

His pallid mane, clawing his withered skin.

Canto XLIII: 169-175: Orlando’s lament

On the Count’s return the cries grew louder,

The sound of weeping, and lamenting, grew,

Then Orlando to the bier drew closer.

And stood awhile, silent, the corpse to view,

Now pale as, at eve, is the acanthus ever,

Or the lily, plucked in the morning dew.

He sighed as he gazed upon the dead,

And with his eyes upon his friend, he said:

‘O brave, O dearest, O most faithful friend,

That, dead, lie here, yet live in heaven above,

And just reward gain thus at your life’s end.

Now heat and cold no longer painful prove.

Look down, forgive the tears I here expend,

Because I linger here, while you remove

To taste of those delights I cannot share,

Though you are here with me, and everywhere.

Alone, without you, naught on Earth can please,

Nor ever will, now you from Earth are gone.

If by your side in war, on stormy seas,

Why not now, when calm and peace you’ve won?

Great must be my sins, that I cannot ease

My soul from out this flesh, and so be done.

Why if I shared your ills, did aid afford,

May I not share in your deserved reward?

Yours is the gain, and mine must be the loss.

Your prize is yours alone, not so my woe;

Germany, Italy, France, all bear the cross.

And oh, how Charlemagne, left here below,

And all his knights must lament; the dross

Is left, the gold, refined, above must show!

How the Empire and the Church will groan

Whose best defence, with you, is overthrown!

How cheered will be your every enemy,

By your death freed from alarm and terror!

Alas, how strengthened Pagandom will be

What joy they will have of it, what pleasure!

And what of Fiordelisa, what of she?

I seem to share her tears; sighs beyond measure

I hear, e’en now; and she hates me, I know;

Through me her hopes are lost, and all is woe.

Yet one comfort, Fiordelisa, we possess,

That are deprived, thus, of Brandimarte,

For every warrior that remains, must bless

His name, and envy his death, his glory.

The Decii, Curtius plunging to success,

King Codrus so renowned in Argive story,

For themselves gained no greater honours,

Nor, by their death, achieved more for others.’

This speech, and others, Count Orlando made,

The while a line of monks, black, white, and grey,

And a host of clerics, moved in sad parade,

Following the bier, borne on its slow way.

To God, for the departed’s soul they prayed.

That it might dwell among the blessed alway.

Bright torches went before, amidst, around,

Turned night to day, and lit the hallowed ground.

Canto XLIII: 176-180: The funeral procession

They raised the bier; many a count and knight

To bear it, turn by turn, had been assigned;

The pall was purple silk, with gold thread bright,

While rarest pearls about the hem did wind.

On gemmed cushions, no less fair, lay the knight;

With no less skill had the fabric been designed.

The corpse in like purple robes was dressed,

Wrought with equal care, fine as all the rest.

Three hundred men headed the procession,

Recruited from the poorest in the land,

And all of them were dressed in like fashion,

In black and trailing gowns; then came a band

Of a hundred pages, in warlike succession,

On a hundred coursers, their reins in hand,

While each splendid steed a page rode upon

Swept the ground with its black caparison.

Banners in front and banners to the rear,

On them many an emblem depicted,

Accompanied, unfurled, the funeral bier,

Gained by many a defeat inflicted,

All won for Emperor and Church, held dear,

By this knight, whose death now both afflicted.

Many a shield too was borne there, by others,

Showing the arms of worthy warriors.

These folk were followed by hundreds more

Ordained for different tasks; shining bright,

The torches that, like all the rest, they bore;

And mantled, say muffled, was every knight,

And dressed in black. Orlando now one saw,

His eyes suffused with tears, a noble sight,

Then Rinaldo, with weeping nigh as blind;

Oliviero, wounded, had remained behind.

It would take too long to tell in verse,

All that was done in honour of the knight,

The black and purple cloaks, each weighty purse,

Given in dispensation, all the bright

Torches that thus, at eve, did morn rehearse.

Beside the way, not a dry eye was in sight;

Every age and rank, both sexes, pitied there,

The death of one so good, so young, so fair.

Canto XLIII: 181-185: The death of Fiordelisa

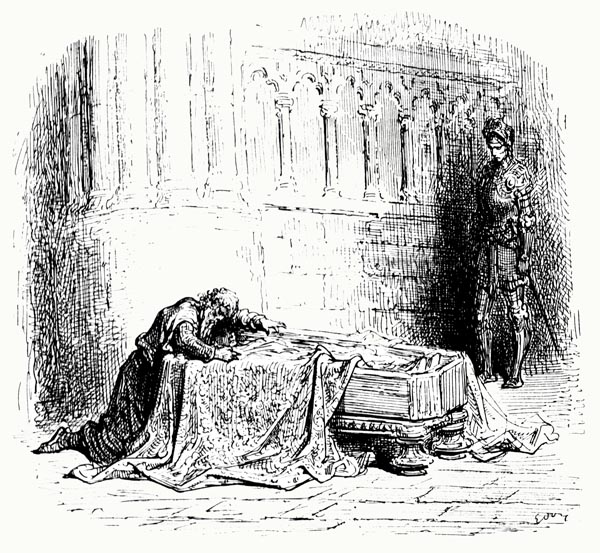

They placed him in the church. When the women

With tears, and vain lament, had mourned the dead;

When the Kyrie had been chanted, and when

Other sacred prayers had been sung or said,

He was laid in an ark by several men,

Which they raised to twin pillars, overhead.

Draped in cloth of gold, he would rest so,

Till his tomb was furnished by Orlando.

The Count would not depart from Sicily

Till he’d procured enough alabaster

To dress the tomb he wished, and porphyry,

And engaged, for the work, a famous master.

Fiordelisa, arriving there most swiftly,

Saw the stones placed, each slab and pilaster,

Brought there (Orlando having gone before)

From fresh quarries on the African shore.

She, finding her tears ne’er ceased to flow,

That sighs, without end, rose from her breast,

Nor mass, nor prayer, repeated, eased her woe,

Nor had the power to grant her longing rest,

Vowed, in her heart, that she’d lie there also

Until her soul had fled its earthly nest.

Within the tomb, they wrought for her a cell,

And, shut within, she in that place did dwell.

Having sent her letters by his messenger,

Orlando went himself, to lead her thence.

If she’d but come to France, he would grant her

Galerana as companion; no expense

Would spare; or if she would join her father,

To Lizza they would go; he, her defence;

Or he would build for her a nunnery

If to serve her God now seemed her duty.

Still to the tomb she clung, till, worn away

By penance, lost in prayer from morn to night,

Atropos cut the thread, and darkened day,

And so released her to the heavenly light.

The three warriors of France, from the bay

Departed where the Cyclops lost his sight.

Each was grieving, still mourning in his mind

Their fourth companion who remained behind.

Canto XLIII: 186-189: The warriors sail to the hermit’s isle

They were loath to go far without seeking

A surgeon to treat Oliviero,

The wound at first painful in the handling,

And hard to ease with salves; in his woe

The warrior cried out loudly, inspiring

Great fear of his dying, in Orlando.

While they were conversing, the captain thought

Of a means to compass what they all sought.

He said that, not far from that very place,

A hermit occupied a lonely isle,

Where none who landed, seeking help or grace,

Would fail of aid, however grave their trial,

And he had treated many a hopeless case,

Cured blindness, and raised the dead erstwhile.

Storms he’d eased and, with the sign of the cross,

Had calmed the waves, and saved vessels from loss.

He doubted not, if they were to sail there,

And seek that holy man, whom God so loved,

And place Oliviero in his care,

He’d restore him, as those examples proved.

His counsel pleased Orlando; they would fare

To that isle; swiftly o’er the waves they moved,

And, never swerving from their course, were borne

To that lonely rock, reaching it at dawn.

The crew now worked the vessel to anchor,

Safely alongside, and not far from shore.

Oliviero, they sought to lower

Into the longboat (him their servants bore)

Succeeded, and drove the frail craft nearer,

Through the spray, till the hermit’s cell they saw,

The hermit who had, not so long ago,

Baptised the shipwrecked Ruggiero.

Canto XLIII: 190-194: Oliviero and Sobrino are healed

The servant of the Lord of Paradise,

Welcomed Orlando and his company,

And blessed them, with a smiling face, likewise,