Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XLII: Rinaldo's Quest

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XLII: 1-6: Ariosto on Vengeance

- Canto XLII: 7-11: Orlando slays Agramante and Gradasso

- Canto XLII: 12-15: Then returns to the dying Brandimarte

- Canto XLII: 16-19: Orlando frees Oliviero and aids Sobrino

- Canto XLII: 20-23: He spies an approaching sail

- Canto XLII: 24-28: Bradamante again complains of Ruggiero’s cruelty

- Canto XLII: 29-33: Rinaldo seeks the help of Malagigi

- Canto XLII: 34-37: Who discovers the cause of Rinaldo’s passion

- Canto XLII: 38-41: Rinaldo asks leave to sail for the East

- Canto XLII: 42-45: He reaches the Ardennes

- Canto XLII: 46-52: And is attacked by a monstrous female form

- Canto XLII: 53-58: A knight, Disdain, comes to his rescue

- Canto XLII: 59-64: Rinaldo drinks of the love-quenching fount

- Canto XLII: 65-69: He still determines to seek Gradasso in Sericana

- Canto XLII: 70-73: He meets a knight who leads him to his palace

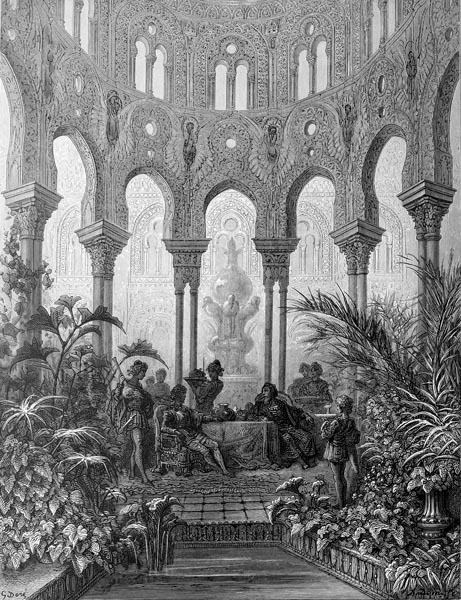

- Canto XLII: 74-79: The palace described

- Canto XLII: 80-82: The female statues supporting the roof

- Canto XLII: 83-95: The identities of these Este women, and their poets

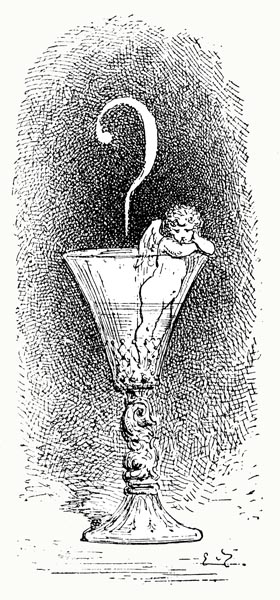

- Canto XLII: 96-104: Rinaldo is offered a drink from an enchanted cup

Canto XLII: 1-6: Ariosto on Vengeance

What harsh bit, what iron curb, could be found,

Or, if such existed, adamantine chain,

That might keep human wrath tightly bound,

And ire within lawful limits, thus, contain,

When we see one that with our love is crowned,

Towards whom we fixed loyalty maintain,

Suffer, through violence or treachery,

Deep dishonour, or be harmed mortally?

And if to cruel and inhuman action

Such anger should lead the human heart,

It may merit forgiveness, for Reason

Has fled from out the mind, and sits apart.

Achilles, who viewed his armour upon

The dead Patroclus, felt that cruel dart,

Unsatisfied, till Hector died also,

And he’d thrice round Troy dragged his mangled foe.

Unconquered Alfonso, a like fury

Engulfed your company on that ill day

When a stone struck your forehead, so cruelly,

All thought your soul had, there, been reft away.

And were filled with such anger, they swiftly

Overran the foe’s defences, made them pay,

Till all, behind wall and rampart, lay dead,

And none was left the sorry news to spread.

Seeing you fall caused ours so deep a pain,

That they were moved to wrath and cruelty.

If you had yet been standing, to maintain

Some order, they’d have wrought less viciously.

Twas enough in one brief hour to regain

Your Bastia of Zaniolo, more swiftly

Restored than won, o’er many days, before,

By Cordoba and Granada, in that war.

Perhaps the Lord above the wound ordained,

Preventing you from leading on that day,

So that ere the deed was done, He’d pained

Your House for their most cruel excess, I say;

For once the Bastia had been regained

The wretched Vestidello, without delay,

Was slain with all his men (unarmed, unbowed)

By an uncircumcised, and evil crowd.

Thus, in conclusion, I would e’er assert

There is no other anger half so great

As when our lord, our kin, our friend is hurt.

So twas just that, in Orlando, the fate

Of his dear friend should, like Nessus’ shirt,

Sting with such fire as will not soon abate,

Seeing Brandimarte stretched on the sand,

Where Gradasso, with bloodied sword, did stand.

Canto XLII: 7-11: Orlando slays Agramante and Gradasso

Like to the wandering shepherd, who sees

The angry viper sliding on its way,

Fangs emptied of their venom ere it flees,

That killed his infant son, erstwhile at play,

And, seeking to slay it, his crook will seize,

So did Orlando grasp his sword, I say,

Keener than other weapons, and swiftly

Rushed first upon the king, Agramante,

Who all drenched in blood, and without a blade,

His shield in two, his helm loose on his head,

Wounded, more than I can say, sore dismayed,

Escaped from Brandimarte’s clasp, half-dead,

(Like a sparrowhawk by eagle’s talons flayed,

Leaving its tail behind) now swiftly fled.

Yet Orlando caught him, and with his sword

He lopped the head from that treacherous lord;

The helm was loose, and all the neck displayed,

The head was severed, like a nodding reed;

The trunk collapsed, beneath the passing blade,

And fell upon the sand, to drain and bleed.

His shade then for those Stygian waters made,

Where old Charon dragged it aboard, at speed.

Orlando, o’er the corpse, scarce stayed longer,

Seeking Gradasso and Balisarda.

Gradasso, seeing head and trunk parted,

And Agramante’s headless corpse laid low,

(No sight for the weak, or the faint-hearted)

His heart shook, a pale visage he did show;

He seemed to quail, his courage departed,

Foreseeing his fate, as on sped Orlando.

No defence did he make, nor sought to flee,

From that mortal blow descending heavily.

Orlando struck him hard, on his right side

Beneath the lowest rib, and then the blade

Through all the flesh and innards swift did glide

Till a hand’s-width of sharp steel was displayed

Beyond the left, which more than testified,

To the strength of the greatest knight e’er made,

Who’d consigned that lord to death at a blow;

The finest warrior Pagandom could show.

Canto XLII: 12-15: Then returns to the dying Brandimarte

The Count knew little joy in victory.

Leaping from his saddle he now sped

(His face the pattern of pure misery)

To Brandimarte’s side, where he yet bled.

The sand all about was soiled and bloody,

The helm as if an axe had struck him dead;

Had it been frailer than a piece of rind,

No worse could it have served him, to my mind.

Orlando raised the visor from the face,

And found the skull cleft, to betwixt the eyes,

Yet, such was the hardiness of that race,

That the knight, of the King of Paradise

Sought pardon for his sins, of His grace,

And ere he died was able to apprise

Orlando of his wishes, and exhort

To patience the Count, with grief distraught;

Whispering: ‘Orlando, please remember

My life, in your prayers of thanks to the Lord.

While to you I must commend my Fiorde…

…lisa he would say, yet that final chord

Was denied him. Thus, he died, while ever

Angel voices sounded, as his soul soared,

The which, dissolved from out its earthly veil,

Midst sweet music, to the heavens did sail.

Orlando, though he knew he should delight

In so blessed a death, and was assured

That Brandimarte’s soul had taken flight

To Heaven, opened to him by the Lord,

His human nature sorrowed at the sight,

That which, to our weak senses, can afford

But suffering, when we lose one dearer

And more to be mourned, than is a brother.

Canto XLII: 16-19: Orlando frees Oliviero and aids Sobrino

Sobrino, who had lost a deal of blood,

Which poured forth from his face, and from his side,

Had been lying some time amidst the flood,

That, draining from his veins, spread far and wide.

Oliviero too, although he would,

Could not withdraw his leg, and must abide,

The foot nigh crushed, so long the limb had lain

Beneath his steed, that proved his master’s bane;

And had Orlando not come to his aid,

(He being weakened, and so full of woe)

He had remained there, and was like to fade;

And once he was freed, it pained him so,

He could not stand alone; each step he made

Was agony, the whole leg numbed also,

Such that he could not move without help;

At each pace issued forth a groan or yelp.

Despite the victory, Orlando grieved,

For too harsh, too bitter it was to see

Brandimarte’s corpse, the wound he’d received,

Nor was Oliviero’s life a surety.

Old Sobrino would survive he believed,

Yet but little light in darkness had he,

For with his blood his strength had ebbed away

And he was like to die that very day.

He had him carried, still bleeding freely,

To be treated by a surgeon, with great care,

And, as if he were kin, he discreetly

Consoled Sobrino, with words ever fair;

For when a fight was over, clemency

Was his way, he was ever prompt to spare

The injured, though the arms and the steeds

He would take from the dead, to serve his needs.

Canto XLII: 20-23: He spies an approaching sail

Now on the truth of this my history,

Federigo Fulgoso has cast doubt.

For, sailing near the shores of Barbary,

He landed, and the whole isle he did scout,

Lampedusa that is, found it hilly,

And saw no level place, thereabout.

There is nowhere, he claims, in all the isle,

Where one might fight, the going is so vile;

Nor can he believe, that, in this affair,

Six valiant knights, the flower of chivalry,

Rode to battle with levelled lances there.

I shall answer his objection, civilly,

There was indeed a strand that they could share,

Beneath the cliffs, though the isle is hilly,

But an earthquake since loosed a mighty block

Of stone that covered all that place with rock.

So, O shining light of your fair line,

Dear Fulgoso, O everlasting ray,

If you must question this tale of mine,

And here, before my lord, must have your say,

(He who’s brought us peace, and all that’s fine)

Forego your hatred, let love win the day;

I pray you, delay not, choose the latter,

And concede: I lie not in this matter.

Orlando, meanwhile, gazing out to sea,

Saw a barque approaching, in speedy style,

A handy vessel that nearing, swiftly,

Looked set indeed to touch upon the isle.

What she was, I’ll not yet say, for clearly

More than one is awaiting me this while,

And, to France I must go, for we must see

If our friends there are woeful or happy.

Canto XLII: 24-28: Bradamante again complains of Ruggiero’s cruelty

There we shall see how the loyal lady

Fares, who saw her knight depart once more,

I speak of the afflicted Bradamante,

For the pledge he had broken, as we saw,

That he’d made with Rinaldo, formerly,

And had, instead, sought to follow the Moor.

Since he’d failed her again, as she thought,

Her hopes, of their marriage, had turned to naught.

Her tearful complaints were now repeated,

All the tale of Ruggiero’s cruelty,

Bemoaning again how she’d been treated,

Cursing her harsh and evil destiny.

Then, by her misery well-nigh defeated,

The heavens, that allowed such perjury,

She called unjust, since they gave no sign,

Or lacked the power to alter fate’s design.

The wise Melissa she accused; then cursed

That deceitful oracle in the cave,

For, persuaded by its lies, she’d immersed

In that ocean of love that drowns the brave.

And then, before Marfisa, she rehearsed

Her woes, and called Ruggiero a knave,

And demanded, midst her complaints and cries,

That warrior-maid’s help, with tearful eyes.

Marfisa shrugged her shoulders and offered

What comfort it was in her power to give,

Not believing (such the advice she proffered)

That he would fail her; she ought to forgive.

If he returned not, twould not be suffered;

She swore to right the wrong if she but lived,

Twixt her and him there would be mortal war,

If he failed to do as he’d pledged before.

By speaking so, she quenched the other’s grief

Somewhat, that once vented, seemed to lessen.

Now we’ve seen Bradamante gain relief,

(Despite that ‘proud, wicked, perjured’ person)

Let’s see if Love has shown himself a thief

Where her brother is concerned, whom reason

Has departed from, whose bones and marrow,

Nerves and veins, are afire; I mean Rinaldo.

Canto XLII: 29-33: Rinaldo seeks the help of Malagigi

That Rinaldo, the brave (who, as you know,

Was full of love for Angelica the Fair,

Though twas enchantment that had drawn him so

To love her, more than her eyes or her hair)

Since the victory had laid the Moors low,

While the other knights seemed free of care,

Amidst the victors, had alone remained

A prisoner to Love, enthralled, enchained.

He’d sent a hundred envoys to find her,

While he himself sought the errant maid,

Then to Malagigi went the lover,

Who had, when needed, offered him his aid.

With blushing face, his gaze ever lower,

He told him of his longing, and prayed

That he might, in his great wisdom, say where

Might be found this Angelica the Fair.

Wonder at the strangeness of the matter

Arose in Malagigi’s mind, and he said,

To himself, that Rinaldo might have drawn her

Oh, a hundred times or more, to his bed,

And, being so persuaded, had ever

Tried to seal that, with all he’d done and said;

For, with prayers and threats, he’d sought to bend

Rinaldo’s will, yet failed to gain his end;

And the more so in that Rinaldo, then,

Would have freed Malagigi from prison,

Yet now, of his own will, he sought again

Her company, and with far less reason.

He begged him to remember how and when

He had offended on that occasion,

Since, by his failing to yield, out of pride,

Malagigi himself might well have died.

The more importunate, to Malagigi,

Rinaldo’s fresh demands of him appeared,

The more it indicated, and more clearly,

How deeply she’d made herself endeared.

Unable to refuse him, the memory

Of that injury from his mind he cleared,

And a friendly countenance he displayed

As he prepared to grant him welcome aid.

Canto XLII: 34-37: Who discovers the cause of Rinaldo’s passion

He set a time by which he’d give his answer,

And gave Rinaldo hope that he might say

Where in France, or elsewhere, Angelica

Had sped to in her flight, and point the way.

And then Malagigi left, to conjure

His demons in their customary array.

In a cave, neath an impenetrable mount,

He oped his book, and called them to account.

Then he chose one skilled in the ways of love,

To discover why Rinaldo’s heart, before

So hard, was now so soft as to approve

The lady, and that circumstance explore.

The demon told him of twin founts that move

To prompt or quench desire, evermore;

For the ill each one breeds there’s no succour

Except to drink deeply of the other.

And Malagigi learned that Rinaldo

Had drunk of the fount that quenched all longing;

Harshness and obstinacy then did show

To Angelica whose love was unending,

And then his ill stars led him to the flow

Of the other fount, and of it drinking

He was filled with endless love for the maid

Whom he’d loathed before, and sought to evade.

While ill stars and cruel destiny had led

Rinaldo to sip flame from icy water,

Angelica had slaked her thirst instead

In the other stream, whose taste was bitter,

And drove all thoughts of love from her head,

Till she loathed him, worse than any viper;

Yet he loved her, desiring all the more

The one he’d hated and disdained before.

Canto XLII: 38-41: Rinaldo asks leave to sail for the East

Malagigi was instructed most fully

By the imp, in the details of the case.

He’d had news of Angelica, who lately

With her love a young African did grace,

And said she’d left Europe, o’er the sea,

For the East, where lay her native place,

Aboard a Catalonian galley,

Bound for India, and her own country.

When Rinaldo arrived for his answer,

Malagigi sought to dissuade the knight

From his love for the false Angelica

Who in a barbarous lad had found delight;

While since, now, he was so far from her,

It was foolish to pursue her sudden flight.

She must have travelled more than halfway,

With this fellow Medoro, to Cathay.

That she was far away now, o’er the deep

Troubled not our Rinaldo, I may say,

Nor did the notion much disturb his sleep

That to the East, thus, he must make his way.

But that a lad, a Saracen, should reap

The fruits of her love, his nerves did fray;

Such heart-ache, such passion, and such strife,

He’d never felt before, in all his life.

He lacked the power to speak a single word;

His heart trembled inside, his lips also,

His tongue moved but not a thing was heard,

His mouth tasted bitter; there bile did flow.

He fled from Malagigi, anger stirred,

In one now filled with jealousy and woe;

After a mighty plaint, and mighty rant,

He thought to make his way to the Levant.

Canto XLII: 42-45: He reaches the Ardennes

In Paris, he sought leave from Charlemagne,

Making the excuse that brave Baiardo

Should not be used against his knights again,

And, so, his honour urged him thus to go,

That he might make his ownership quite plain,

Believing the horse still with Gradasso,

That must not be left to claim that his lance

Had won the courser from a knight of France.

Charlemagne, thus, gave him leave to depart,

Though all of France lamented that he should;

And yet could not deny him, for his part,

Since bold Rinaldo’s intention seemed good.

Dudon, with brave Guidon, should also start,

He said, his firm friends, but Rinaldo would

Have naught of this, and from Paris, alone

He took his way, with many a plangent moan;

For, in his mind, he dwelt upon the thought

That a thousand times he might have won her,

Yet, obstinate and foolish, though besought

By her a thousand times, declined her offer,

Considering her love a thing of naught;

That sweet and lovely chance was lost for ever.

Yet now, but for a day, he’d have her nigh,

And after that brief moment seek to die.

Twas ever in his mind, and ne’er did part

From his sad thought that, for a soldier-boy

She had driven her first love from her heart,

Despite its worth, exchanged it for a toy.

Vexed by this, that nigh tore his soul apart,

To the East he sped, the hours did employ

In making for the Rhine and Basle, and found

Himself in the Ardennes, on wooded ground.

Canto XLII: 46-52: And is attacked by a monstrous female form

Venturing many a mile, midst the trees,

Far from habitation, where all was drear

And perilous, possessed by some unease,

The sky above seemed darkened, far and near,

The sun was lost in cloud, and stilled the breeze,

And where a cliff arose, its heights unclear,

From a shadowy cave that there did gape,

A monstrous form emerged, female in shape,

A thousand lidless eyes set in her head.

With no way to close them, she never slept.

She had as many ears as eyes and, spread

O’er her skull and brow, evil serpents crept.

From the infernal shadows, dark and dread,

Out of the depths, to which alone she kept,

This creature came; a tail about her wound,

A larger serpent coiling all around.

What had never troubled our knight before,

Not in ten thousand ventures, did so now,

As that most strange and dreadful form he saw

Emerging from her cave with snaky brow;

Chilled was the blood that through his veins did pour,

Deep fear he felt, twas fear he did allow,

Yet feigned his usual look of bravery,

Merely gripping his good sword more tightly.

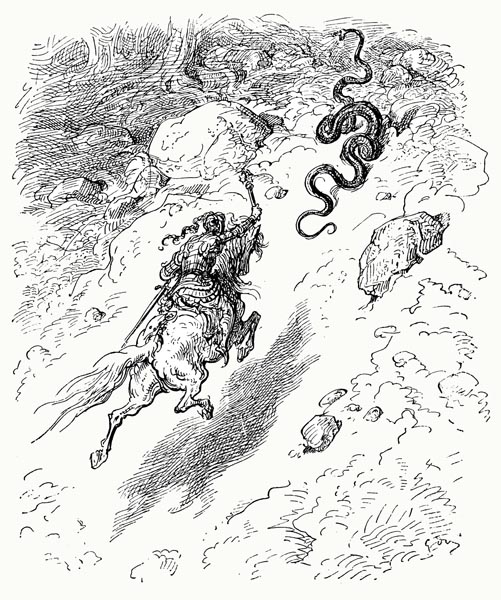

So fierce the attack the monster now made,

Her mastery of such assaults was evident,

For she brandished the serpent like a blade.

It hovered, then struck, in venomous descent,

And, swaying about him, her calls obeyed.

Rinaldo dodged its fangs; with vain intent

He thrust and swept his sword against the foe,

Yet failed to land a single wounding blow.

Now she would aim the serpent at his chest,

Freezing his heart within his coat of steel,

Now at his visor flung the evil pest,

That did the warrior’s face and eyes conceal.

Rinaldo fled the field, his steed addressed

With flailing spurs, his blood like to congeal.

The infernal Fury scarcely seemed to halt;

In a trice, to the crupper, she did vault.

To right, to left, where’er he sought to go,

That accursed pest was ever at his back,

Nor could he manage to remove her so,

Though the horse reared, and plunged, about the track.

His heart shook like a trembling leaf, and though

Her snaky locks refrained from close attack,

Those things such horror and such loathing bred

He moaned and groaned, and wished that he were dead.

Down the saddest gloomiest paths he went,

Threading his way through the tangled wood,

By vilest leap, and thorniest vale, half-spent,

Where all seemed darkest, seeking, if he could,

To thwart that hideous creature’s foul intent,

Rid himself of the monstrous form, for good.

Even so, all might have ended badly,

If one had not appeared to aid him, promptly.

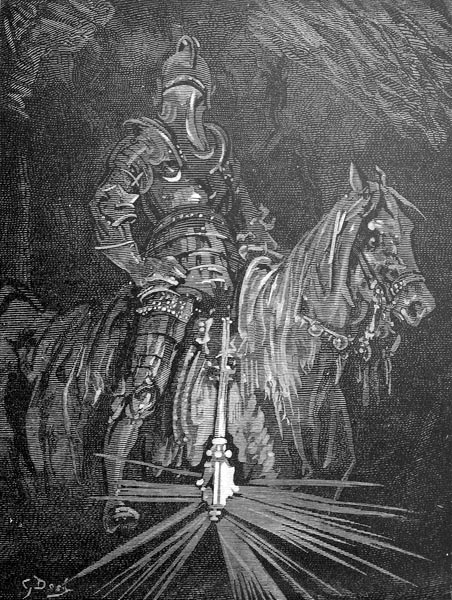

Canto XLII: 53-58: A knight, Disdain, comes to his rescue

For succour, just in time, a knight now brought,

His crest a broken ploughman’s yoke, his shield

(For he was armed, as if some joust he sought)

Showed crimson flames upon a yellow field.

So was his coat embroidered, thus he fought;

His steed’s caparison the like revealed.

A lance he grasped, his sword was at his side,

And, to his saddle, a blazing mace was tied.

The mace was wreathed in an undying flame,

Being always alight, but ne’er consumed,

Nor shield, nor amour, could escape that same,

Nor solid helm, but all such things it doomed.

And all made way where’er that warrior came,

Yielding to this thing, that flared and fumed.

No less was needed, you will understand,

To free Rinaldo from the monster’s hand.

As a warrior full of courage should

He galloped to the source of those load cries,

And there he saw the monster, midst the wood,

Gripping Rinaldo in her serpent ties,

That would have cast her from him, if he could,

For, from her grasp, he sought himself to prise.

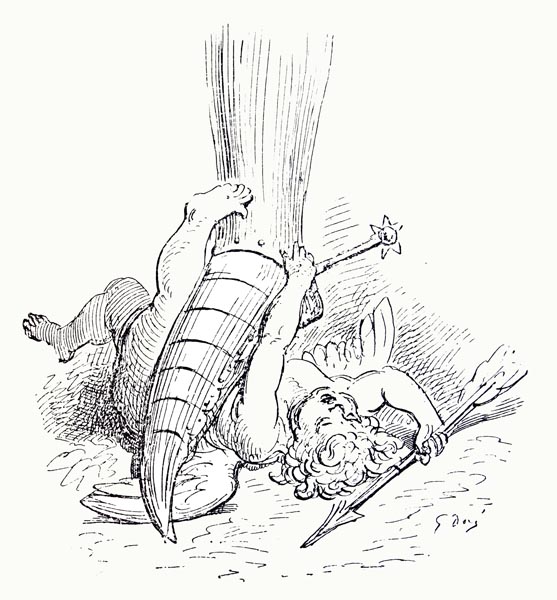

The knight approaching struck her evil hide,

Until she fell, upon her left-hand side.

Yet she had scarcely fallen ere she rose,

And shook the vile serpent all about her.

The knight, abandoning his lance, now chose

To scorch her with the flame, and make her suffer.

He gripped the mace, and a hail of blows,

Upon that serpent form, thought to deliver.

Nor allowed a moment for the monster

To recover, or charge at him in anger:

And the while he struck, or held her at bay,

So, avenging a thousand acts of shame,

He advised our knight to ride, without delay,

And ascend the mountain, flee the evil dame.

He took that sound advice, and went his way,

Without glancing back to learn what became

Of the creature, who soon was lost to sight,

Though twas hard to climb the rugged height.

The warrior who’d sent the infernal monster

Scurrying to her dark cave, far below,

Where she bit and gnawed herself, forever,

Shedding tears from her eyes, in ceaseless flow,

Sought Rinaldo to guide him thereafter,

Caught him, and lest he wander to and fro,

He rode along beside him, without fail,

And led him from that ill and gloomy vale.

Canto XLII: 59-64: Rinaldo drinks of the love-quenching fount

Finding him there beside him, Rinaldo

Declared he owed the knight thanks indeed,

And that he would repay what he must owe,

With his life, if ever there should be need.

Then he asked his name that he might know

Who twas that to his aid had thought to speed,

So that he might, before King Charlemagne,

Praise to the skies and, there, exalt that same.

The knight replied: ‘Let it not displease you,

If I choose not to give my name, for now;

Before the shadows grow a pace or two,

I will, if you’ll that short delay allow.’

Then, as they rode, a river came in view,

That drew the passer-by to bathe his brow,

And shepherd-lads, likewise, to stop and drink,

And banish fruitless longings, at its brink.

For, clear and cold, here flowed that chilling stream,

That ever quenched the burning heart’s love-woe.

By drinking there, Angelica, I deem,

Had conceived her hatred for Rinaldo.

And if he once had loathed her, it would seem,

And her sweet love been ready to forego,

Naught else as the cause, I would offer,

But drinking of its enchanted water.

The knight who accompanied Rinaldo,

When he beheld the river flowing there,

Reined in his weary steed, beside its flow,

And said: ‘We might halt here; it seemeth fair.’

‘It cannot but be good, I say also,’

The other replied, ‘such coolness to share.

The midday sun is hot; tis for the best

Free of that evil creature, to seek rest.’

The pair dismounted, and each let his steed

Graze, untethered, through the forest glade;

And set their helms upon the flowery mead,

Whose yellows, greens, and reds, a picture made.

Then our knight to the crystal stream did speed

Driven, by thirst and heat, therein to wade,

And with one cooling draught, Rinaldo proved

Free, in his mind and heart, of thirst and love.

When the other knight saw Rinaldo

Raise his head from the murmuring water,

And that the knight repented, in his woe,

Of his foolish love for Earth’s fair daughter,

He lifted his head and proudly did bestow

His name upon the air, that earlier

He had withheld, and cried: ‘I am Disdain,

Come to free you from suffering in vain.’

Canto XLII: 65-69: He still determines to seek Gradasso in Sericana

And, so saying, he vanished in a trice.

As the courser too vanished from his sight,

The good Rinaldo blinked, not once but twice,

In wonderment, and asked: ‘Where is the knight?’

Thinking this was, perchance, some charmed device

Of Malagigi’s, who had sent this sprite,

And had commanded it to break the chain

Which had so fettered him, and end his pain,

Or that an angel, from the heavenly sphere,

The Lord above had sent, of His goodness,

And so ordered all, as, it would appear,

He’d once ordered Tobit healed of blindness.

Whether good or evil, and from there or here,

Who, thus, had freed him from his close duress,

He thanked and praised him, and only knew

That he had granted liberty anew.

He loathed the thought now of Angelica,

While his aim of pursuit seemed unworthy;

Nor should he seek to follow her further,

Not half a league, but forego her wholly.

Yet, to win Baiardo, to Sericana,

He still proposed to pursue his journey,

For his honour was involved and, again,

He’d spoken of the thing to Charlemagne.

Indeed, he reached Basle the following day,

To which the news had come awhile before

That Orlando, in arms, had sailed away,

On Gradasso and the king, to wage war.

Twas not the Count who’d sent word, I must say,

That they would meet on Lampedusa’s shore,

But a messenger had sailed from Sicily,

Who swore the thing was so, in verity.

Rinaldo wished to be with Orlando,

And yet he found himself far from the fight.

He changed his steed every ten miles, though,

And spurred away, as hard as any might.

Across the Rhine, at Konstanz, he did go,

Then o’er the Alps, to Italy passed the knight,

Left Verona, and then Mantua, behind,

Crossing the River Po, as he’d designed.

Canto XLII: 70-73: He meets a knight who leads him to his palace

The sun was declining towards evening,

And the first stars were gleaming in the sky,

As our knight stood, on the shore, deciding

Whether to ride on, or to lodge nearby,

Until, the shadows and the mists pursuing,

Fair Aurora would chase them forth, thereby;

When he saw a cavalier approaching

His courtesy, in face and manner showing.

Greeting our knight, thus, graciously, he sought

To ascertain if he were wed or no.

Wondering at the question, in a thought,

He answered: ‘I, indeed, am knotted so.’

‘I joy at that,’ came the other’s retort,

And, to explain himself to Rinaldo,

Added: ‘I pray you’ll lodge with me this night,

And be content to view a pleasant sight,

For I would have you see what any man

That is so wedded, willingly, would see.’

Rinaldo thought this a most fitting plan,

For, of travel, he was more than weary,

And then adventures oft with such began,

Which he ever desired (he loved them dearly).

He accepted this kind offer from the knight,

And followed on behind, to view this sight.

Not a bowshot from the road went the pair,

And, before them, a palace came in view,

Whence brave squires came, in haste, to light them there,

Their torches flaring, ever and anew.

Rinaldo entered, and saw all was fair,

A place of beauty, such as few men knew,

Of fine and sound construction, on a plan

That befitted none but some princely man.

Canto XLII: 74-79: The palace described

The archway’s stones were all of porphyry,

And of serpentine, and bronze, was the door,

With figures cast there, that apparently

Lived and breathed, while, embedded in the floor,

Mosaics in bright hues, attractively

Arrayed, deceived the eye, with fair allure.

The quadrangle, within, was long and wide,

A hundred yards of colonnade on each side.

Each gallery was entered through a gate,

With archways set there between the two,

Each of equal breadth, variously ornate,

For the architect had splendour in view.

Each arch led to a stair, wide and straight;

The ascent a steed could easily pursue,

It was so gentle; arches topped them all,

And each archway gave entrance to a hall.

These arches above projected some way,

And so shaded the grand portals below,

While twin pillars supported each tall bay,

Of bronze, or of marble white as snow,

Twould take too long to speak of the array

Of ornamented chambers row on row,

In that courtyard, beneath which, indeed,

The architect hidden rooms had decreed.

Tall columns, with their capitals of gold

Supporting gemmed entablatures, and rare

Slabs of marble decorated with untold

Forms and figures all finely carved and fair,

Pictures, and bronze casts, that court did hold,

(Though, in truth, obscured by the shadows there),

Showing that two king’s riches would ne’er

Have sufficed to raise that palace in the air.

Over the ornaments, which occupied

That pleasant quadrangle, a fountain played,

Scattering in many threads, on every side,

Fresh water midst the items there arrayed.

In this court many tables, long and wide,

Servants set at equal intervals, and laid,

Where the four gates any there might see,

And be seen from those four gates, equally.

That fount had been made with subtle labour,

And great skill, by a master of such art,

Colonnaded with a sloping cover,

With eight faces, thus shaded, at its heart.

A gilded roof capped the court, moreover,

With enamelled work below in every part,

While eight statues supported it below,

(With their left arms) of marble white as snow.

Canto XLII: 80-82: The female statues supporting the roof

In each right hand, the ingenious master

Had sculpted the horn of Amalthea,

From which water fell, with pleasant murmur,

Into a vase carved from alabaster,

And had likewise fashioned each pilaster

In female shape, and ever modelled after

Some great lady, in both form and face,

And all of equal loveliness and grace.

The feet of each female statue rested

On two male statues, fashioned equally,

Whose open lips graciously attested

To their delight in song and harmony.

And their attitude indeed suggested

That all of their effort, and close study,

Was but to laud those ladies set above,

Whose living likenesses they each did love.

These statues below proffered, in their hand,

Fair scrolls, both broad and long, the which contained

The names and praises of those who did stand

Above (more worthy) with their roles explained;

While their own names were also close at hand,

Thus, their identities were, there, maintained.

Rinaldo reading, midst the blaze of lights,

Named, one by one, the ladies and their knights.

Canto XLII: 83-95: The identities of these Este women, and their poets

The first inscription there that met his eye

Spelled out, at length, Lucrezia Borgia’s fame.

Whose chastity and beauty, Rome, say I,

Places her above one that once bore her name.

Antonio Tebaldeo, on high,

With Ercole Strozza, supported that same.

(So said the scroll, so that tuneful pair

A Linus, an Orpheus, fill the air.)

No less lovely a form followed after,

On the scroll this sentiment was expressed:

‘Ercole’s daughter, fair Isabella,

Behold here, by whom all Ferrara’s blessed,

(Born here within its confines) more than ever

That realm is favoured, and all the rest

Of the gifts benign Fortune there bestows,

As time upon its endless journey flows.’

The pair below, who desire, hereafter,

To sing her praises, both Gian Jacobi

Are named, Bardalone and Calandra.

On the third and fourth sides (there, lightly,

Through narrow channels, the gleaming water

Escaped the octagon) there stood a lady

With a second, equal to her in birth,

And in realm, honour, beauty, and in worth,

Elisabetta, and Leonora;

And, if we believe what the marble said,

The latter was born in fair Mantua

(That honours Virgil, he who there was bred,

Yet honours her no less, moreover,

Nor her that to its gracious lord is wed)

Whose feet on Pietro Bembo were set

And upon Jacopo Sadoleto.

Castiglione and Aurelio sustained,

With elegance and art, the other lady,

Or so the scroll’s inscription there maintained,

(Both then unknown, now well-set for glory)

Next came a lady on whom heaven rained

Such virtue as was never known in story;

She, to the good or ill brought to our age

By Fortune, inured; e’er gracious and sage.

Engraved in golden letters, our knight read:

‘Lucrezia Bentivoglio (of Este)

Whom Ferrara’s Duke joys in having bred,

Amidst his other praise, such her beauty.’

Camillus sang of her (above his head)

Reno and Felsina moved profoundly,

By his sweet voice, showed wonder at the strain

(Like that with which Amprhysus heard his swain)

With one through whom that lovely city’s name,

Set where Foglia meets the sea, Pesaro,

Africa and India shall acclaim,

And farthest north, and farthest south, yet know;

And, thus, for more that city shall win fame

Than enriching the Papal coffers; lo,

Silvestri, I mean (Guido Postumo)

Crowned by both Minerva and Apollo.

Dian d’Este was the next in order,

‘Care not,’ in the marble was carved, there,

‘That she seems proud of face, for within her

Is a heart as humane as she is fair.’

Celio Calcagnine shall praise her

And bear her name and glory everywhere,

Till Juba’s and Moneses’ Parthians hear,

With Spain to farthest India, far and near.

And Marco Cavallo, who such a fount

Of poetry shall bring forth in Ancona,

As did Pegasus on that fairest mount,

Parnassus (no, twas Helicon rather).

Beatrice now appeared, of whom account

Was made in the scroll that she did offer:

‘A blessing to her spouse, while she had breath,

She, thus, left him grief-stricken at her death,

And our Italy, indeed; victorious

While she yet lived, a mere captive after.’

A lord of Correggio has granted us,

In lofty style, a poem on the matter,

And the Bendedeis’ pride, Timotheus;

Twixt its banks, this pair shall halt forever

Our River Po (whose trees shed tears of amber,

When Phaethon fell) with their sweet endeavour.

Between her place and that lofty pillar

Carved in Lucrezia Borgia’s likeness,

A statue had been carved in alabaster,

A lady of such grace and nobleness,

That neath a veil, simple in its manner,

And free of gold or gems, in plain black dress,

Midst the bejewelled, she seemed no less bright,

Than Venus does amidst the stars of night.

None might tell, though gazing fixedly,

If her beauty was greater, or her grace;

Or more intelligence or honesty,

Or more majesty present in her face;

‘Who that would speak of her,’ was writ clearly

In the marble, ‘wherever speech takes place,

Upon no worthier task could e’er expend

His labour, yet that task shall find no end.’

Though her statue, both well-wrought and lovely

Was, thus, filled full of grace and sweetness,

She seemed disdainful that one so lowly,

And devoid of wit, should sing her greatness;

One that stood alone, lacking company

(I know not why) to sustain her likeness.

The names of all those others were revealed;

This pair’s the artist had, it seems, concealed.

Canto XLII: 96-104: Rinaldo is offered a drink from an enchanted cup

The statues formed a circle, at the centre,

While of coral was the pavement below,

Cooled and sweetened by the falling water,

Pure as crystal, that sent its murmuring flow

Along a channel through the wall, to further

Moisten and cool a flowering meadow,

Gladdening the plants and flowers that grew

Nearby, their colours yellow, white and blue.

Rinaldo sat at table, and conversed

With his host, all impatient now to hear

Of the matter he’d earlier rehearsed,

(To his promise, he’d have him thus adhere)

While observing his visage, for accursed

With some deep woe the knight did e’er appear,

Since, as he spoke, not a moment went by

Without his yielding forth a burning sigh.

Oft our knight was on the point of asking

The reason, and yet smothered the request,

Refraining, through courtesy, from seeking

An answer, thinking reticence was best.

But now, as their meal approached its ending,

A youth, who was standing midst the rest,

Placed a golden cup before our paladin,

Bejewelled without, and full of wine within.

Then, with a seeming smile, the host raised

His eyes, and fixed them upon Rinaldo,

Who yet thought, as on his host he gazed,

That he smiled less in joy than in sorrow.

‘I’m reminded,’ twas thus the host now phrased

His address, ‘that, the time has come to show

A wondrous way of knowing, without strife,

What every man should know that has a wife.

Every husband, in my judgement, ought

To keep an eye on whether he is loved,

To know if shame or honour haunts his court,

And whether man or beast he thus is proved;

And yet the weight of antlers is as naught

Though to ridicule all the world is moved,

For though his shame, by all, thereby is read,

He feels them not, that wears them on his head.

If you know that she’s faithful to you ever,

You’ve more reason to love and respect her

Than he who knows his wife has a lover,

Or he who is but doubtful of her honour.

Many a spouse from jealousy will suffer

Though his wife ne’er glances at another,

While many a man has felt himself secure

That on his brow most splendid antlers wore.

If you would know whether your wife is true,

(As I trust you believe, and should believe,

For tis wrong to think aught else, unless you

Clear proof of unfaithfulness should receive)

None other than you yourself shall view

What she is at, thereby to joy or grieve,

If you’ll drink from the cup that’s here displayed,

That I might fulfil the promise that I made.

Drink from this, and a marvel you shall see,

For if you bear King Mark’s Cornish crown,

Ne’er a drop shall pass your lips, but freely

Shall descend, and all your clothing drown.

But if she’s faithful you may quaff it deeply.

Now try your fate, and drink the vintage down!’

With that, he fixed his gaze on Rinaldo,

To find if he would quench his thirst or no.

Rinaldo was nigh tempted to discover

That which, perchance, twas better not to know.

He reached out his hand, watched by the other,

And took the cup, disposed to doing so,

When, suddenly, he thought on the danger,

Ere it touched his lips and the wine did flow.

But let me rest a moment here, ere I

Continue with the paladin’s reply.

The End of Canto XLII of ‘Orlando Furioso’