Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XLI: Ruggiero Baptised

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XLI: 1-3: Ariosto’s tribute to the founder of the House of Este

- Canto XLI: 4-7: Ruggiero frees the seven kings, and sails for Africa

- Canto XLI: 8-17: His barque encounters a storm

- Canto XLI: 18-23: The skiff sinks while Ruggiero swims to the surface

- Canto XLI: 24-25: The abandoned barque drifts ashore near Bizerte

- Canto XLI: 26-29: Orlando takes Ruggiero’s sword, Oliviero his armour, Brandimarte his steed

- Canto XLI: 30-36: The three warriors set sail for Lampedusa

- Canto XLI: 37-46: Brandimarte makes an offer to Agramante which is refused

- Canto XLI: 47-50: Ruggiero vows to become a Christian if he escapes the sea

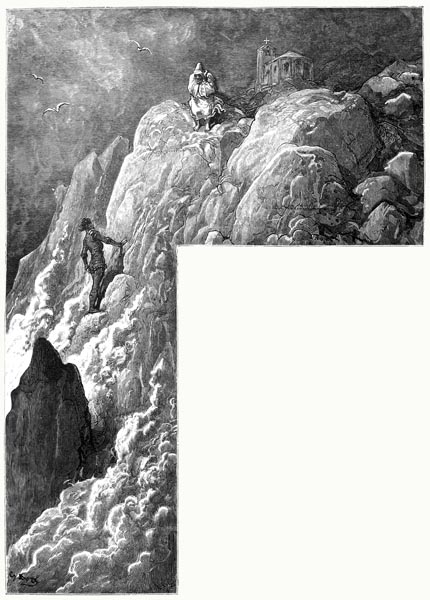

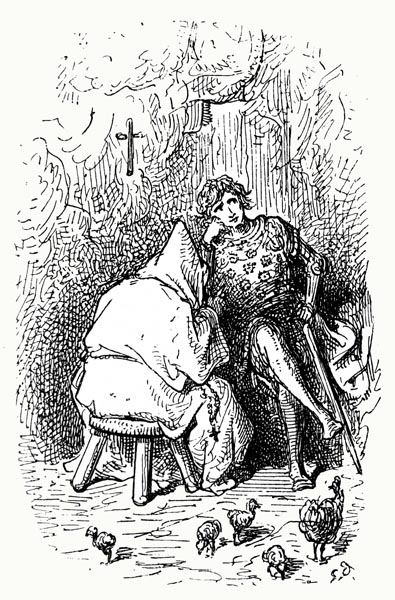

- Canto XLI: 51-56: Gaining the shore he encounters a hermit

- Canto XLI: 57-60: Ruggiero is baptised

- Canto XLI: 61-65: The hermit speaks of the founding of the House of Este

- Canto XLI: 66-67: And the vengeance to be taken for Ruggiero’s death

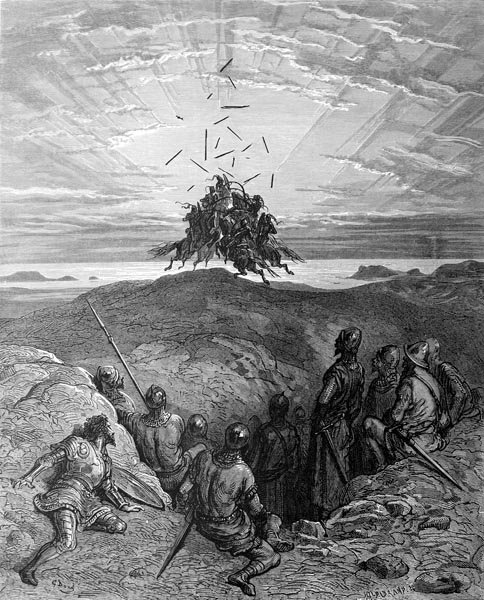

- Canto XLI: 68-73: The battle on the island commences

- Canto XLI: 74-80: Orlando stuns Sobrino

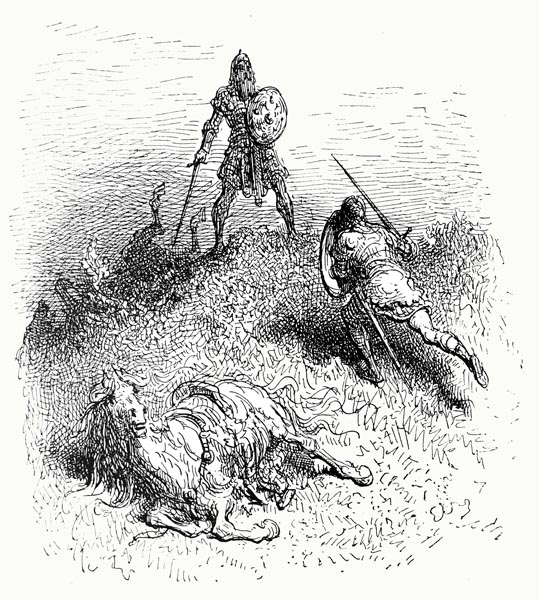

- Canto XLI: 81-85: And then fells Gradasso

- Canto XLI: 86-90: Sobrino recovers and attacks Oliviero

- Canto XLI: 91-93: Brandimarte attacks Agramante

- Canto XLI: 94-98: Gradasso causes Orlando’s horse to flee

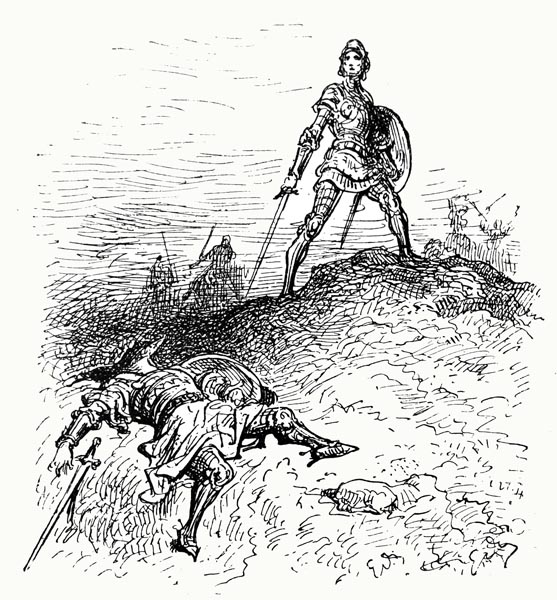

- Canto XLI: 99-102: Brandimarte is felled by Gradasso

Canto XLI: 1-3: Ariosto’s tribute to the founder of the House of Este

That odour sweetly scattered in the air

From the hair, or beard, or dainty dress

Of some graceful youth, or damsel fair,

That Love stirs, through weeping to excess,

If tis breathed where other folk may share,

For many a day, its perfumed loveliness,

Shows by its clear and manifest effect,

How fine its source is, there, midst the elect.

The wine Icarius made the shepherds drink

To his great cost, the like of which they say

Lured Celts and Boii o’er the Alpine brink,

To Italy, unwearied on their way,

Shows the like sweetness of its source, I think,

Since its sweetness lasts out the year alway.

The tree whose verdure lasts the winter through

Shows the green vigour of its springtime too.

So, the famed lineage that, for many a year,

Has shed its light, with grace and courtesy,

Yet seems to shine more brightly, ever clear,

Gives indication, through its majesty,

That he that was the source of glory here,

The House of Este, shone as brilliantly,

In all ways that exalt men to the sky,

As does the sun among the stars on high.

Canto XLI: 4-7: Ruggiero frees the seven kings, and sails for Africa

Ruggiero showed clear and manifest

Tokens of valour and of courtesy,

His high-mindedness nobly expressed,

In every deed he wrought of chivalry,

So Dudon, he restrainedly addressed,

(As I revealed to you previously)

In feigning some lack of strength or breath,

A reluctance to bring about his death.

For Dudon now knew, of a surety,

That Ruggiero wished his foe unharmed;

The Dane’s defence was offered but weakly,

So weary was he, yet his life seemed charmed.

Comprehending this, and seeing clearly

How Ruggiero held back, quite disarmed,

Though less in strength and vigour, certainly,

He yet strove to yield naught in courtesy.

‘For God’s sake, sir’, he said, ‘let us agree,

To cease this fight, I cannot but confess

Myself thus conquered by your chivalry,

Nor may I, here, achieve the least success.’

Ruggiero answered him: ‘And I no less

Desire the truce, that you now wish of me,

Upon condition that these seven are freed,

And rendered to me. Do you so concede?’

He pointed to the seven kings, who stood,

Heads bowed, as Ruggiero spoke further,

Adding that no obstruction later should

Prevent their journeying to Africa.

Dudon agreed, and he the truce made good,

By freeing them, granting a barque thereafter

To Ruggiero, whiche’er he pleased, who then

Sailed, with the seven, for Africa again.

Canto XLI: 8-17: His barque encounters a storm

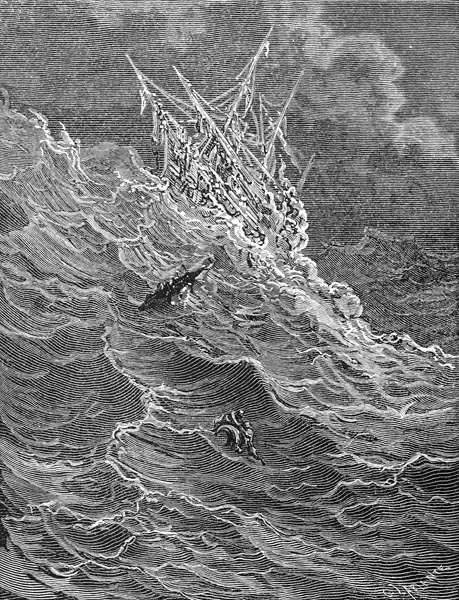

Once loosed, the barque, with gleaming sail outspread,

Gave herself gladly to the steady breeze

That, at the start, conveyed her straight ahead,

Leaving her master idling, and at ease.

The land retreated now, as on they sped,

The waves calm denizens of shoreless seas,

Until, at eve, the breeze grew changeable

Showing itself but fickle and unstable.

It blew from stern to bow, then bow to stern,

But there did not remain; the vessel reeled,

Confounding the pilot, at every turn,

As the wind altered, his fear unconcealed.

The billows rose, the sea began to churn,

Neptune’s pale herd near and far revealed;

As many deaths there seemed, amidst that flow,

As the waves that drove their barque to and fro.

Now blew the wind before, and now behind,

Sending her forth then back, ceaselessly,

Or blew athwart them, rendering them blind,

With spray that lifted high above the sea.

The master, pale of face, oft changed his mind,

Calling, and gesturing, though fruitlessly,

For the sail to be reefed, the mast lowered,

As o’er the helpless craft the waves towered.

Scant use were his gestures, his cries in vain,

For naught could be perceived amidst the gale,

His shouts were smothered by the wind and rain,

The wind and rain that ever did prevail,

Drowning the sailors’ cries of grief and pain,

Merged with the waves’ crash, in an endless wail.

The storm reigned fore and aft, on every hand,

Such that none heard the pilot’s least command.

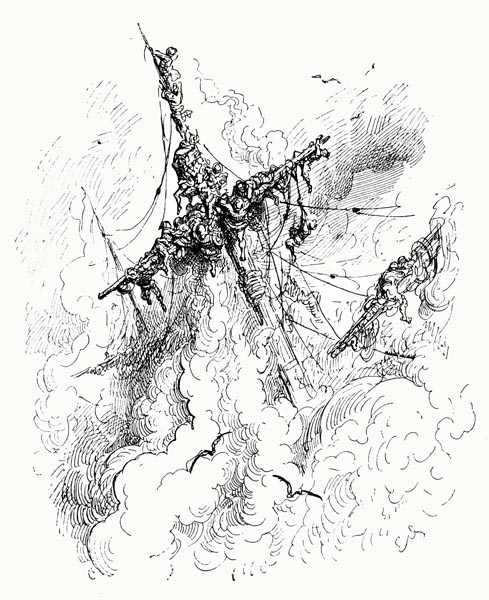

The raging storm roared about the rigging,

That ever gave out dreadful moans and screams;

Wild lightning flashed amidst its groaning,

While thunder crashed to company its gleams;

One man gripped the helm, some tried deploying

The weighty oars, that seemed mere useless beams,

One sought to free a rope, one to bind fast,

Others bailed furiously against the blast.

Higher the strident screeching of the gale,

As Boreas in sudden fury blew,

Driving against the mast the flapping sail,

While vast breakers rose to the sky anew.

The oars now broke, wielded to no avail,

While to mere chance or fate yielded the crew,

As the prow turned to leeward, and the barque

Yawed, defencelessly, in a sickening arc.

On her beam ends, on her starboard side,

About to turn keel uppermost, she lay,

While all, to God above, now prayed and cried,

Certain of being drowned, or borne away;

The sea now gripped them, not to be denied;

The wave was weathered, yet the next, I say,

Caused the barque to split; amidst her beams

The water poured, through the opening seams.

The wintry tide now flowed through every part,

Mounting a cruel and merciless attack;

So high the waves rose as they broke apart

They seemed to reach the sky ere falling back,

While so deep the vessel sank, for her part,

Hell seemed rent open to the nether black.

Small hope was there, or none; with trembling breath,

All there foresaw inevitable death.

Through that weary night, o’er the sounding sea

They were driven, at the mercy of the gale,

While the wind, that might have dropped completely

With the dawn, gathered force, set to prevail.

A bare rock o’er the prow loomed, suddenly,

That all prayed to avoid, yet, without fail,

Despite themselves, towards that rocky place

The tempest drove them, and at headlong pace.

With pallid face, the helmsman, three or more

Attempts now made to steer another course,

Seeking escape, yet the vast waves now tore

The splintered helm away, with massive force;

While what canvas was left served the more

To drive them onwards, and their fate endorse.

No time was there to ponder what was best;

Mortal danger now close upon them pressed.

Canto XLI: 18-23: The skiff sinks while Ruggiero swims to the surface

Perceiving now there was scant remedy,

That their barque was certain to be wrecked,

Each to his own affairs tended closely,

Seeking to save his life; to that effect,

The nearest launched the skiff, leaping quickly

Into the little vessel, frail, undecked,

So many thus o’er-whelming the boat

That, driven deep, it scarce remained afloat.

Ruggiero, seeing the master and the mate

Abandoning the barque without a fight,

Unarmed, and in his doublet, chanced his fate,

Leapt down, and in the skiff did now alight,

But found it then so burdened with the weight

And others yet descending from the height,

Who further pressure on the skiff bestowed,

That into the depths it sank, with all its load.

Into the depths, with those who, in despair,

Had left the larger vessel to the sea,

As woeful cries a moment filled the air,

Calling for heaven-sent aid, fruitlessly.

But a brief instant, all those struggled there,

For the waves rose, in anger, scornfully,

And suddenly occupied all that space,

Whence the cries rose, their striving to efface.

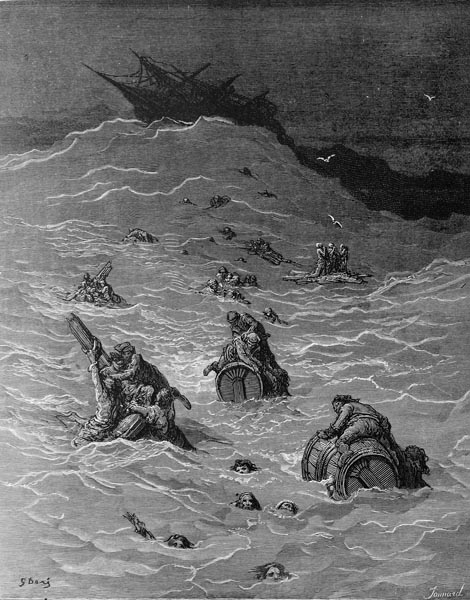

Some, plunged in the deep, were drowned outright,

Others emerged, and sought to ride the flow,

Swam so their heads were lifted to the light,

While an arm, a naked leg, the waves did show,

Ruggiero, whom danger did ne’er affright,

Sprang to the surface from the depths below,

And found himself not far from the bare rock,

That their every effort had seemed to mock.

He hoped, by use of his strong legs and arms,

To swim, climb upon it, and gain the shore.

And breasting the water, despite all alarms,

Unwearyingly, he cleft through the waves before

His face, while, ceasing from their former harms,

Those troubled waters from the sea-cliffs bore

The unmanned barque, abandoning to their fate

Those who had sought to flee her side of late.

Alas, for the endless errors of mankind!

The ship they thought would perish yet survived.

For when the master and the mate resigned

Her to the gale, deserting her, she thrived.

The wind, to which her course was now consigned,

Now drove her on, the waves beneath her dived,

And, now the crew had fled, she floated free

Of danger, to drift safely o’er the sea.

Canto XLI: 24-25: The abandoned barque drifts ashore near Bizerte

Blown astray when her helmsman was aboard,

Without him she reached Africa’s bare shore,

Three miles from Hippo, on the sands toward

The north, facing Egypt, at rest once more,

(As the winds fell, the waves sank in accord)

On the deserted beach, sans sail or oar.

There, walking o’er the strand, as you will know,

For this I’ve told you of, came Orlando.

And, wishing to see if she was empty,

Or held some last remnants of her cargo,

He approached in a skiff, with Brandimarte

Beside him there, and Oliviero.

Into the hold they descended swiftly,

Yet found naught living there, but Frontino,

And strapped to his saddle, Balisarda,

And, at his feet, Ruggiero’s armour.

Canto XLI: 26-29: Orlando takes Ruggiero’s sword, Oliviero his armour, Brandimarte his steed

Ruggiero had been swift to take flight,

And so had left the famous blade behind,

Balisarda, known by the Count on sight,

And which had once been his, you’ll call to mind,

For Boiardo has told the tale outright;

How Falerina lost it, there you’ll find,

When he laid waste to her garden, that lord,

And how Brunello later stole the sword;

And how beneath Carena’s mount, as well,

Brunello gave it, freely, to Ruggiero.

He, from its use, its great worth could tell,

(Peerless its temper, and its edge also)

I mean Count Orlando, who for a spell

Had wielded it, from whom thanks now did flow

To Heaven; believing (as he later said)

Twas sent by God ere to the fight he sped.

For he had need of it against Gradasso,

The King of Sericana, who beside

His great valour and strength, had Baiardo,

And the sword Durindana at his side.

Knowing not Ruggiero’s armour though,

He ranked it less highly, than his own hide;

Fine was the plate and mail, yet suited more,

He believed, to adornment than to war.

Since he needed it not against the foe,

(Being charmed against all weaponry)

He gave the armour to Oliviero,

But set the sword at his side, hanging free;

While to Brandimarte went Baiardo,

The Count sharing out the spoils equally.

And, thus, each companion gained a prize,

One coveted by each of them likewise.

Canto XLI: 30-36: The three warriors set sail for Lampedusa

In rich new gear, for the appointed day,

The knights now dressed, to meet the Moorish king.

Orlando on his shield did, there, display

Babel’s mighty tower, struck by lightning;

On Oliviero’s a greyhound argent lay,

With a leash about its neck, and bearing

A motto: ‘Till He comes.’ In golden vest,

Signalling his worth, the knight was dressed.

For the day of battle, Brandimarte

Had chosen to wear a mournful colour,

Both in his murdered father’s memory

And for the sake of personal honour.

Fiordelisa sewed the surcoat, nobly,

As well as she knew how, and its border

Of many a costly gem was possessed,

Although of plain black cloth was all the rest.

She wrought the costly garment with her own hand,

To adorn the splendid suit of armour,

In which the knight his courser would command,

With a caparison that steed to cover;

But from the day Fiordelisa first planned

The work till it was done, and thereafter,

The lady never smiled, nor showed a trace

Of happiness upon her lovely face.

Ever her heart was fearful, tormented

By the thought that he’d be taken from her,

A hundred times and more she’d consented

To see him fight battles fraught with danger,

But never this terror, that ne’er relented,

Had she felt, that so froze her blood, never

This ceaseless fear within, this chilling blast,

That yet made her poor heart beat twice as fast.

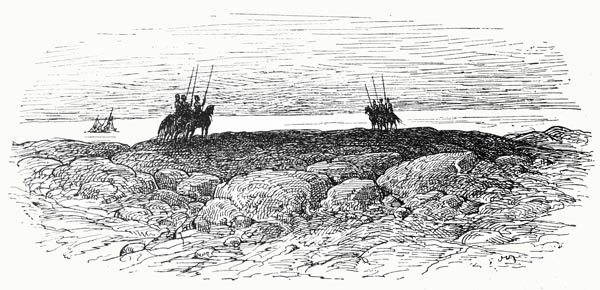

Once armoured at every point, and armed,

The trio set sail, with Sansonetto

Remaining there to see that naught was harmed,

Sharing the task of care with Astolfo;

While Fiordelisa, troubled and alarmed,

Heart filled with fear, a saddened face did show,

Prayed and lamented, watching anxiously

Their vessel, as it vanished o’er the sea.

Nor did Astolfo and Sansonetto

Find it easy to tempt her from the shore,

And lead her to the palace at last, so

She might seek her bed there, lamenting sore.

Meanwhile a favourable wind did blow

And to Lampedusa, swiftly, bore

The warriors, elected thus to fight;

The chosen isle appearing on their right.

Disembarking, the Lord of Anglante,

With Brandimarte, and Oliviero,

Being first to arrive, intentionally

Pitched their tent on the eastern shore, so

That when, on that same eve, Agramante

Came, to the other he was forced to go;

For, since the sun was sinking in the west,

The fight must wait till dawn, and they seek rest.

Canto XLI: 37-46: Brandimarte makes an offer to Agramante which is refused

Placed here and there, until the morning light,

Armed servants stood about, to guard the tent.

To where the Saracens thus camped, that night,

Brandimarte, seeking peace, in silence went,

And, by Orlando’s leave, in a forthright

Manner, spoke with Agramante, his intent

Most friendly, for he had, a time before,

Neath the Moorish banner reached France’s shore.

After a fair greeting, hand clasping hand,

The trusted knight many a reason gave

The Moorish king why he should not demand

They fight the battle, though all there were brave.

Every place would yet be his to command,

Between the Nile and the Western wave,

Offered, there and then, by Orlando’s leave,

If in the Virgin’s Son he would believe.

‘Since I’ve both loved you and do love you still,

This same counsel I give to you,’ he said.

‘And know that I pursue it, of my free will,

And find it good, and to the faith am wed

Of Christ the Lord, and others count as nil;

And would have you follow my way instead,

The way of true salvation, and would move

Your heart to join with me, and those I love.

Therein lies your good; no other counsel

That you could follow here would so avail,

And least of all to now engage in battle

With Orlando, whoever might prevail.

For the loss and the gain are unequal,

The one outweighs the other on the scale;

If you win, small the prize that you will gain,

But great the loss, should you defeat sustain.

Were Orlando and we others to die,

We who will fight to the death at his side,

I see no path ahead for you, whereby

You may recover your realms far and wide.

If we three dead upon the sand should lie

Then our replacements are identified;

A host of knights Charlemagne could send

The least of his vast domains to defend.’

Thus, brave Brandimarte spoke, and many

A point he might have added to his speech,

But in an angry voice, Agramante

Interrupted him, ere such he might teach:

‘This is pure madness, tis audacity

Alone inspires the words you seek to preach,

Foolish is that counsel where none is sought,

Whether for good or ill its words are wrought.

And how the words you speak can proceed

From the affection that you held, you say,

And hold for me yet, I know not, indeed,

Seeing you here, with Orlando, this day.

I deem that, finding that you have agreed

To meet the dragon and become its prey

That e’er devours men’s spirits, you would draw

All others to that dark infernal maw.

Whether I win or lose, command my throne

As of old, or in exile spend my days,

Is a thing that is known to Allah alone,

Whose will none sees; for ours is but to praise.

Whate’er may come to me, I’ll make no moan,

But show myself a worthy king always,

If fated to death or shame, then I shall die,

Rather than mar my princely line thereby.

Now you may return, who, should you display

No better prowess in tomorrow’s fight

Than as an orator you’ve shown today,

Would ill accompany Anglante’s knight.’

No more did the angry king wish to say,

His heart with both pride and ire set alight;

They parted then, to seek their own repose,

Till o’er the eastern wave the sun arose.

The warriors awoke with dawn’s first light,

Then armed themselves, and mounted each his steed,

Brief words were said, twixt knight and hostile knight,

And then without delay, since all agreed,

They lowered their fell lances, sharp and bright.

And yet if I should speak of each brave deed

That befell there, will not poor Ruggiero

Drown in that angry sea, and sink below?

Canto XLI: 47-50: Ruggiero vows to become a Christian if he escapes the sea

In truth, Ruggiero, swimming strongly,

Cleft the wave, and rode the angry sea.

Yet his conscience troubled him more sorely,

Than wind and water, and more urgently.

He feared God’s vengeance, in that previously,

When occasion offered, he’d failed to be

Baptised in fresh, and now was in danger

Of a dire baptism in briny water.

All of those promises now came to mind

That he had made to his loving lady;

And his oath to Rinaldo that did bind

Him, as an honest knight, made but lately

Yet unfulfilled. To God he now consigned

His being, pledging there his soul and body

To Christ, should he escape a watery grave,

Praying that Heaven might preserve and save.

He swore he nevermore would wield a lance

Against the faithful, in aid of the Moor,

And that he’d return speedily to France,

To honour Charlemagne upon that shore,

And marriage to Bradamante advance,

Nor fail in his pledge to her as before.

It seemed a miracle that, with this prayer

His strength increased, and better he did fare.

His strength increased, and his courage also,

He cleft the waves, hurled aside the water,

As they raised him high, and then thrust him low,

Buoyed by one, nigh-smothered by another.

Labouring hard, and yet his progress slow,

He gradually drew closer and closer

To where the land sloped gently to the sea,

And, issuing forth, from the waves won free.

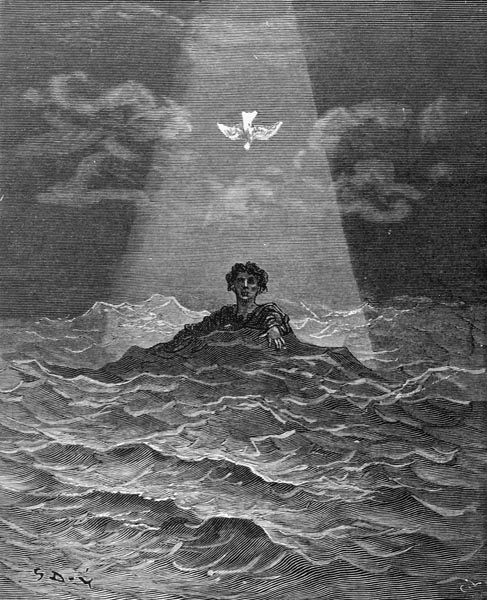

Canto XLI: 51-56: Gaining the shore he encounters a hermit

All the rest who’d been plunged in the flood

Were drowned, and sank to rest neath the wave;

Ruggiero, as Providence thought good,

Had issued forth alone, whom God did save.

Yet once upon the barren slope he stood,

Safe from the sea, feeling less than brave,

He dreaded the harsh confines of that shore,

Where he might starve; as troubled as before.

Yet with steadfast heart, prepared to suffer

Whatever the heavens above had decreed,

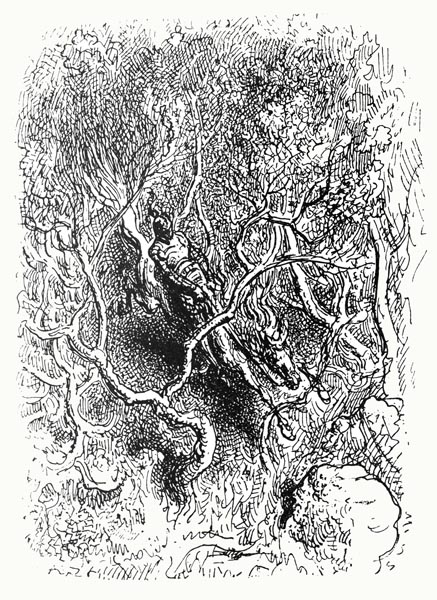

He clambered amidst the rocks, and ever

Sought the far heights above him, in his need;

And not a hundred yards from the water

Had he gone, for the boulders did impede

His progress, when a hermit he espied

Old and lean, descending the mountainside.

And ‘Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?’

He heard the hermit cry (as the Saviour

Cried out to Saint Paul who did journey,

He falling to the ground, changed forever.)

And then he cried: ‘You thought to pass the sea,

Pay naught, and therefore betray another,

Yet found God has an arm to strike alway,

When you thought his influence far away.’

And the hermit added that, the night before,

As he slept, God had sent him a vision,

Of how Ruggiero would reach the shore

With His aid, and He would make provision

For his safety, and had then revealed more,

Of the warrior’s past and, in addition,

Of his future, and his death, and his heirs,

Sons, grandsons, scions, and all such affairs.

Thus, the hermit reproached Ruggiero,

But comforted him also, in the end;

Reproached him, in that he’d failed to follow

The way, scorning his proud head to bend;

Telling him how he should have bowed low,

Willingly, and thus called on Christ to send

Him grace, for he had failed to demonstrate

His own, till threatened with an evil fate.

Yet consoled him that Christ will ne’er deny

His Heaven to the sinner, soon or late,

If such will seek it, and all, low or high,

That strive will be repaid at equal rate.

He instructed him in the faith, thereby,

With a warmth and kindness commensurate

With his zeal and devotion, as he led

Ruggiero to the cave where lay his bed.

Canto XLI: 57-60: Ruggiero is baptised

High on the slope, above that hallowed cell,

A chapel glowed there, in the morning light,

Spacious enough, and fair, and wrought full well.

Descending to the shore, as yet in sight,

A stretch of laurel, juniper, myrtle fell,

With fruitful palms, and there a fountain bright

Sent forth its waters, in a crystal flow,

From the heights to the barren rocks below.

It was nigh on forty years, to the day,

Since the hermit had retired to that place,

In holy solitude to fast and pray,

Where the Saviour had led him, of His grace.

Berries, and herbs were his sole mainstay,

And the water, wherein he bathed his face,

Yet sound and robust, of all illness clear,

He had lately reached his eightieth year.

Within the cell, the hermit lit a fire,

And set a heap of berries on the board,

The which, once he had dried himself entire,

Some sustenance to the knight did afford.

Of the faith to which he now did aspire,

He was taught, and of the words of the Lord;

And in the pure fountain, that next morn,

Was baptised by the hermit, and reborn.

Ruggiero was pleased, awhile, to stay,

Since the servant of God showed his intent

To help him forth, on his previous way;

With their conversation he was most content.

Now of God’s kingdom they spoke all day;

Now of what to his life was pertinent,

All those matters that applied to his case;

Now of his heirs, and of the future race.

Canto XLI: 61-65: The hermit speaks of the founding of the House of Este

The Lord, who sees and hears everything,

To the holy hermit had revealed, say I,

How Ruggiero now baptised, surviving

A mere seven years, would come to die,

(The death of Pinabel, thereby, requiting,

His lady’s deed, though on him it did lie,

And his despatch of vile Bertolagi)

Slain at the hands of the Maganzese;

And how their treachery would be concealed,

So that of it none would hear a whisper,

For they would bury him upon the field

Where they’d gathered to commit his murder,

Yet he’d be revenged (their fates were sealed)

By the hands of his lady, and his sister;

And how his wife would seek him far and wide,

(Full with his heir, and near her term beside)

Twixt Brenta and Adige (neath those hills

That had so pleased the Trojan Antenor

With their many sulphurous veins and rills,

Fruitful soil, and pleasant slopes, and more,

Leaving behind the pools that Xanthus fills,

Lamenting Ascanius, Mount Ida hoar)

Bearing her child in the forest, secretly,

Which lies not far from ‘Phrygian’ Ateste.

And how, in beauty and in valour grown,

On his son, likewise named Ruggiero,

His Trojan lineage once proved and known,

Those Trojans would the lordship then bestow.

And how this valiant son, his mettle shown

In fighting, fiercely, gainst the Lombard foe,

As its marquis, the land would then retain,

Through aiding the armies of Charlemagne.

And that king, in Latin, would cry: ‘Este!’

On his saying ‘Be lord, here,’ so granting

A name to the place now known as Este;

Fair augury to that domain would bring,

Losing but two letters from ‘Ateste’,

Its former name. Further prophesying,

Through his servant, the Lord had then proclaimed,

How vengeance for his death would be obtained.

Canto XLI: 66-67: And the vengeance to be taken for Ruggiero’s death

He would come, in a dream, to his lady,

A little while before the dawn of day,

And tell her of his death, and where his body

Bereft of life by those villains, now lay.

And she, and Marfisa, would, valiantly,

Then put to fire and sword fair Poitiers,

While, once of age, his son, Ruggiero,

Would deal the Maganzeses a fierce blow.

Azzos, Albertos, Obizzos, also

The hermit spoke of; Borso, Nicolò,

Leonello, Ercole, Alfonso,

Isabella the Fair, and Ippolito,

And then fell silent; on Ruggiero

Not a further word would he then bestow.

He’d revealed all it was fine to reveal,

Concealing all it was right to conceal.

Canto XLI: 68-73: The battle on the island commences

Meanwhile, sword at his side, Count Orlando,

With Brandimarte and Oliviero

Went to seek the Saracen Mars, his foe,

(A title well-suited to Gradasso)

And the other two, who had not been slow

To set forth either, I mean Sobrino,

And King Agramante, whose fine coursers

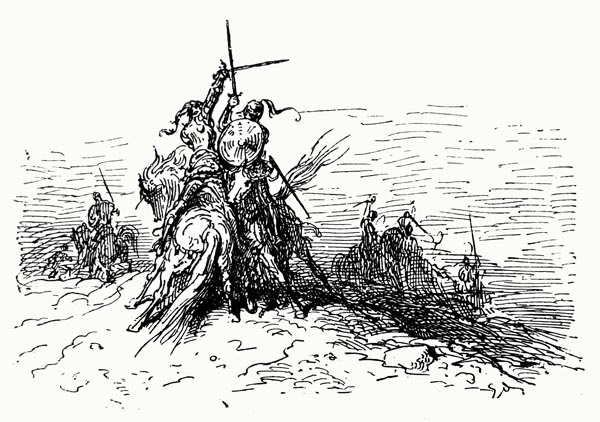

Sent hoofbeats echoing o’er the waters.

When the knights met, in their first encounter,

Splinters flew skywards from every lance;

The sea itself almost seemed to quiver,

And the tremors to spread as far as France.

Gradasso and Orlando clashed together,

And that contest had seemed equal, perchance,

If it had not been that King Gradasso

Seemed the stronger mounted on Baiardo.

For the latter steed struck the lesser horse,

That Orlando rode, with such might and main,

It staggered to and fro, such was the force

Of the blow, and then fell upon the plain.

Orlando tried to raise the steed, perforce,

Full thrice, and then again, with spur and rein,

And, gaining scant success, quit the charger,

Raised his shield, and then drew Balisarda.

Agramante met with Oliviero,

Who seemed on a par, in the encounter;

While Brandimarte unhorsed Sobrino,

Although it was unclear if the courser

Was at fault or the rider, such a blow

Had seldom caused Sobrino to falter.

Whether twas his or his horse’s deed,

Sobrino found himself without a steed.

Brandimarte on seeing Sobrino

Spread-eagled on the ground, left him there,

And turned his steed to charge at Gradasso,

Who’d unhorsed Orlando; while the pair

That seemed equally matched, Oliviero

And Agramante, each maintained their share

Of the contest, who with swords did advance,

Since, on meeting, each had shattered his lance.

Gradasso seeming not to care to turn

And attack him again, for he could not,

(Brandimarte with such rage did burn

That Gradasso his former foe forgot)

Sobrino was Orlando’s new concern,

For, like him, to fight afoot was his lot.

He advanced, and made the heavens tremble

At his tread; some god he did resemble.

Canto XLI: 74-80: Orlando stuns Sobrino

Sobrino, viewing this new foe, now stood,

And prepared to counter the fresh essay,

Like to a helmsman threatened by the flood,

Scared that the waves will sweep him away,

That grips the tiller, fear chilling his blood,

Like a shield; as now, in this dire affray,

Sobrino gripped his hard, ere he was gored

By the point of Falerina’s charmed sword.

Of such fine temper was Balisarda,

That a shield provided little shelter.

And when wielded by such a warrior,

No targe in the world its blade could counter.

It split the thing, and drove deep, thereafter,

Below it, into Sobrino’s shoulder;

The shield though bound with an iron band,

Burst, nonetheless, beneath Orlando’s hand.

The sword descended, and though Sobrino

Was encased in steel plate, and iron mail,

He yet seemed unprotected, even so;

Wounded deep, he found it did scarce avail.

He struck Orlando (though vain was the blow),

Against whom every such attack must fail,

To whom by the Prime Mover was given

A hide resistant to every weapon.

The mighty Count, redoubled his labour,

Thinking to remove Sobrino’s head;

Sobrino, knowing Chiaramonte’s valour,

His shield all but destroyed, withdrew instead,

And yet not so swiftly that a further

Blow fell not, that looked to strike him dead;

He felt the flat of the blade, yet such again

As to crush his helmet, and stun his brain.

Its force drove Sobrino to the ground,

And long it was before the knight could rise.

Orlando thought, because he gave no sound,

He’d struck the other dead before his eyes;

And, lest Brandimarte fell, swung around,

And charged at Gradasso, to surprise

That pagan king, superior perforce,

In his strength, and in armour, blade and horse.

Bold Brandimarte, mounted on Frontino,

The which was Ruggiero’s steed before,

Had fought so well, trading blow for blow,

That Gradasso’s strength seemed little more.

Had he owned as fine a breastplate to show

As the king he’d have fought the better war,

But, feeling less well equipped, the knight

Gave ground slowly, swinging left and right.

There was no horse better than Frontino

At understanding his master’s intent

And then he seemed to anticipate each blow

Of Durindana, as here and there he went.

Meanwhile Agramante and Oliviero

Fought well and fiercely, skill with courage blent,

And both judged themselves equal in a fight,

Given their great experience and might.

Canto XLI: 81-85: And then fells Gradasso

The Count, as I said, had left Sobrino

Stunned upon the ground, and desiring

To aid Brandimarte, on Gradasso

Turned his eye anew; and, while yet speeding

To reach that warrior and land a blow,

He came upon the horse, now wandering,

Which earlier had old Sobrino thrown,

And, having grasped it, made that steed his own.

Uncontested, he seized the horse, and then

Mounted the willing steed, and shook the rein,

One hand steered the creature, as and when;

The other grasped his sword; as o’er the plain

Gradasso spied him, and defied both these men,

Shouting out Orlando’s name, with disdain,

Hoping to send both foes far from the light,

To greet eternal darkness, ere twas night.

Turning from Brandimarte to the Count,

He thrust at the junction of his helm and mail,

Of all but Orlando’s hide it took account,

Against which no mere weapon might avail.

At the same moment there arose a fount

Of his own hot blood, for naught could prevail

Against Balisarda, that sheared his helm, and shield

And breastplate, and the flesh beneath revealed,

Wounding Gradasso in face, breast and thigh,

Which neath that armour had ne’er bled before.

And it seemed strange (he felt about to die

Of rage and pain) a blade could deal so sore

A blow not Durindana’s, one whereby

He might have scarce survived a moment more.

Had the Count stretched further or been closer,

He’d have cleft the bone from crown to shoulder.

He could trust no more in his strong arm,

That many a time had been proved in war.

With greater care, to keep himself from harm,

He prepared to parry, not as before.

Brandimarte seeing the Count’s right arm

Draw Gradasso from him, o’er the shore,

Now placed himself between the pairs of knights,

To lend aid, if he might set things to rights.

Canto XLI: 86-90: Sobrino recovers and attacks Oliviero

With the fight in that perilous state,

Sobrino, who had lain there on the ground,

Recovering from the blow he’d felt of late,

Rose, though badly bruised as he now found.

He lifted his gaze, to ascertain his fate,

And Agramante, at some distance, found,

To whom he hastened, to grant him succour,

Silently, unseen by any other.

From the rear, he crept upon Oliviero,

Whose eyes were fixed upon Agramante,

And dealt the former’s steed a sudden blow,

Behind the knee, landing it so fiercely,

That the courser was, in a trice, brought low,

While Oliviero lay beneath, his foot caught tightly

In the stirrup; thus, unexpectedly,

He found himself unable to fight free.

With a back-handed sword-stroke, Sobrino,

Pursuing, thought to, now, behead the knight,

Yet forgot Hector’s armour that, below

Etna’s Mount, Vulcan wrought with all his might.

Bradamante saw the danger, at the foe

He drove, on viewing Oliviero’s plight,

Struck Sobrino on the head; hard the blows,

But the veteran swiftly to his feet arose.

And turned upon Oliviero to send

The knight’s soul more promptly on its way

Or at least ensure that he must defend

His limbs, and so keep him there at bay.

Oliviero, whose right arm could amend

His state, sought to keep his blade in play,

And, lunging and striking, here and there,

Stopped Sobrino from ending that affair.

He hoped, if he could hold him off awhile,

Though the ground beneath him ran red with blood,

He might shortly issue forth from this trial.

Yet he was bleeding, and thus understood,

The ending might prove ill, and fate hostile,

For his weakness augured nothing good.

Often Oliviero strove to rise,

Yet could not move his leg in any wise.

Canto XLI: 91-93: Brandimarte attacks Agramante

Brandimarte had reached Agramante,

And swiftly set about the Moorish king,

Spurring Frontino at him fiercely,

Frontino, ever lunging, and wheeling.

A fine steed had the son of Monodante,

No lesser a steed the Moor was riding,

Brigliador, his gift from Ruggiero,

That the knight had reft from Mandricardo.

And a further advantage he enjoyed,

For his armour was as yet good and sound,

While Brandimarte another’s employed,

Nigh-on the first, in his need, he had found;

Yet his courage ever his hopes now buoyed,

And he intended to wrap his frame around

With the monarch’s yet; though a sudden blow

Had made the blood from his shoulder flow,

And Gradasso had pierced him in the side,

(Naught to smile about) in their encounter.

The Frank the perfect moment did abide,

And then struck hard at the royal warrior,

He broke the shield, the left arm sorely tried,

And, on the hand, barely touched the other.

Mere play their fierce battle seemed when matched, though,

With that twixt Orlando and Gradasso.

Canto XLI: 94-98: Gradasso causes Orlando’s horse to flee

Gradasso had half-disarmed Orlando,

Shattering his helm, at sides and top,

(His breastplate was split, his mail also,

His shield, part torn away, he now let drop)

Yet had wounded not that charmed hide below.

Worse had Orlando done who’d sought to lop

His head away, wounding, face, throat and breast,

Thus, adding to what he’d wrought on the rest.

Gradasso, desperate, when he espied

Himself now dyed bright red with his own blood,

Yet Orlando, from head to foot, descried

Unstained, all his flesh still sound and good,

Thinking the Count’s whole body to divide

(His sword raised in both hands) if he could,

Struck hard, as he had planned, at Orlando.

Smiting him on his forehead with the blow.

Had it not been the Count but another,

He’d have cleft him to the saddle, straight,

But the sword merely bounced backwards, rather

As if naught but the flat had struck his pate.

Orlando was quite stunned, and a scatter

Of bright stars filled his eyes, such was the weight

Of that blade; he dropped the rein, nigh unmanned,

His sword though was still chained to his hand.

The horse was so frightened by the sound

(The steed that bore the Count on its back)

That it galloped off, o’er the sandy ground,

Showing that no turn of speed it did lack,

Unrestrained by its lord, escape it found,

He being dazed, and weak from the attack.

Gradasso would have caught him, soon after

If he’d spurred Baiardo somewhat faster,

But, in truth, his eye fell on Agramante,

Now in the utmost peril in his fight,

For he’d been gripped by Brandimarte

By the gleaming helm, and the Frankish knight

Unlacing it, might have slain him surely,

Or at the best have robbed him of his sight.

Nor had the king his blade at his command,

For Brandimarte had torn it from his hand.

Canto XLI: 99-102: Brandimarte is felled by Gradasso

Gradasso turned about, and left the chase,

And sped to where he had espied the king.

The incautious Brandimarte, whose face

Was turned towards his task, never thinking

That Orlando might Gradasso outpace,

Remained fixed upon what he was doing.

Gradasso in a trice had swung his blade,

Two-handed, and upon the helm it weighed.

Heavenly Father, grant midst your elect

A place to one most faithful, ever true.

Whose voyage having ended, ne’er shipwrecked,

Now furls his sails in port, and comes to you.

O Durindana, how, to such cruel effect,

Could you betray your lord, obey the new;

Slaying his dearest and most loyal friend,

With Orlando a witness to his end?

An iron ring, two inches thick, that bound

His helm about, was broken by that blow,

And with that metal, circling it around,

The cap of steel was cleft that lay below.

Brandimarte, unhorsed, fell to the ground,

Whose pallid face his fate did sadly show,

While there issued forth from his poor head

A stream of blood that dyed the gravel red.

Regaining his stunned senses, Orlando

Turned his gaze, and saw him lying there,

And, standing beside the knight, Gradasso,

Caught in the act, the culprit thus laid bare.

If anger filled him more, or deep sorrow,

I know not, yet little time for despair

Had he; his anger rose, he stayed his woe.

While, here, I must end the present canto.

The End of Canto XLI of ‘Orlando Furioso’