Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XL: The War in Africa

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XL: 1-5: Ariosto again recalls the Battle of Polesella

- Canto XL: 6-9: Agramante and Sobrino flee

- Canto XL: 10-14: Orlando and Astolfo attack Bizerte (Hippo)

- Canto XL: 15-19: The assault on the city

- Canto XL: 20-26: Brandimarte scales the wall

- Canto XL: 27-32: The others follow and take the city

- Canto XL: 33-36: Agramante is restrained from suicide

- Canto XL: 37-39: Sobrino counsels him

- Canto XL: 40-42: Ariosto on the danger of trusting in allies

- Canto XL: 43-46: Agramante reaches an isle, and finds Gradasso there

- Canto XL: 47-50: Gradasso offers to counter the incursion

- Canto XL: 51-55: They issue a challenge to Orlando

- Canto XL: 56-61: Which he readily accepts

- Canto XL: 62-68: We return to Ruggiero and his duty to Agramante

- Canto XL: 69-72: Dudon and his men disembark

- Canto XL: 73-78: Ruggiero encounters Dudon

- Canto XL: 79-82: But refrains from injuring him

Canto XL: 1-5: Ariosto again recalls the Battle of Polesella

Long would it take indeed, were I to tell

The many events of that fierce sea-fight,

Ercole’s great son; and I might as well,

Bear, as they say, in my two arms outright,

Vases to Samos, owls to Athens, fell

Crocodiles to the Nile, for such a sight

You have, in detail, spoken of to me,

And what you saw have made all others see.

Long the spectacle that your loyal men

Viewed, as they watched, a night and a day,

As in some theatre (gazing hard and often)

That hostile fleet, on the river Po, at bay,

Twixt fire and sword, as in a floating pen,

What cries, what woe, what blood, there, flowed away!

How many were the ways you saw men die!

Or showed to those you sought not to deny!

I saw it not, who was obliged to go,

Full six days earlier, to Rome, in haste,

Changing steeds each hour, muddied head to toe,

To seek aid from the Pope, whom there I faced;

But could have then returned with footsteps slow,

The golden lion’s beak and claw defaced,

For you gave Venice such a scare, I say,

She has dared not try the like, since that day.

But good Alfonsin Trotto who was there,

Hannibal, Alfranio, Alberto,

Three Ariostos, witness to that affair,

Pier Moro, Bagno, and Zerbinatto,

Told me of it; and torn banners, to spare,

High in the church, I viewed, and below;

And fifteen galleys by the river’s shore,

With a host of captive vessels too, I saw.

Who viewed that whole fleet, sunken or afire,

So many deaths, so various in kind,

(Our vengeance for our palaces, that pyre)

Till all were taken, drowned, or undermined,

May picture the ruin, wretched and dire,

That Agramante suffered (to my mind,

Well-nigh as great) when Dudon midst the wave

At night attacked his fleet (and nigh as brave).

Canto XL: 6-9: Agramante and Sobrino flee

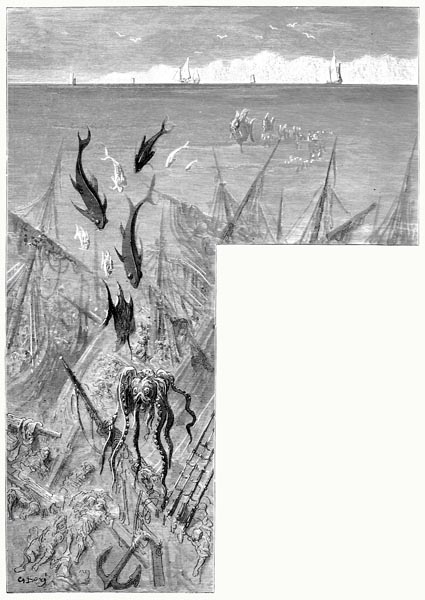

Twas night; not a gleam of light to be seen,

When that bitter naval battle first began,

Yet when sulphur, pitch, and tar, flew between

The vessels, and fire through the rigging ran,

To burn at bow and stern, and send its sheen

O’er the waves, consuming all in its span,

There was glow enough to see all about,

And night seemed turned to day, midst the rout.

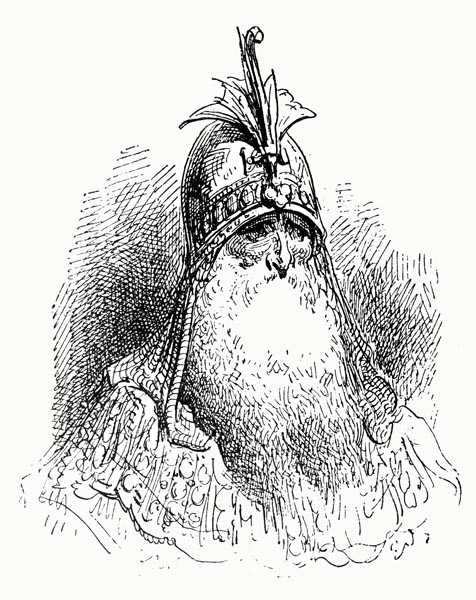

Agramante, deceived by the darkness,

Had not thought the enemy’s force so great,

Nor that, once they were met with steadfastness,

They could do aught but bow to their fate;

But now that the night gave way to brightness,

This fleet, that he’d failed to anticipate,

Was, as he saw, nigh twice his own in size,

And destroying his ships, before his eyes.

He descended to a light barque, below,

In which stood Brigliador, near a hoard

Of precious things; and then, silent and slow,

It tacked its way, bearing those aboard,

To safety, far from his men’s pain and woe,

Whom Dudon sore bitterness did afford;

Fire scorched their flesh, waves drowned, the fierce steel slew,

While the cause of all fled with but a few.

With Agramante went old Sobrino,

One whom the king now wished he had believed,

When that seer had foreseen a day of woe,

And proclaimed the ill that he now perceived.

Yet I must turn to our Count Orlando

Who, ere Bizerte further aid received,

Counselled Astolfo to destroy the place,

So, France its threat might then no longer face.

Canto XL: 10-14: Orlando and Astolfo attack Bizerte (Hippo)

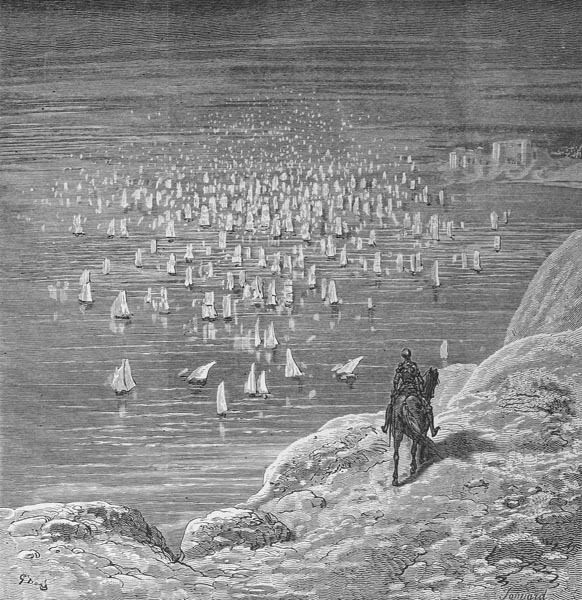

And, therefore, it was proclaimed, publicly,

That all must stand to arms on the third day.

Many a ship was deployed out at sea,

To blockade the port; with Dudon away,

Sansonetto led that squadron, for he

On sea or land, was as brave in the fray;

And his ships remained there, at anchor,

A mile from Bizerte and its harbour.

As true Christians, Orlando and Astolfo,

Who risked naught without God at their side,

Ordered prayers, and strict fasting also,

Throughout their forces scattered far and wide,

And decreed, on the third day, all must go

To their posts, and when the signal was spied,

Then Bizerte must be ceaselessly attacked,

And, once taken, must be set ablaze, and sacked.

Once the prayers and the fasting were over,

And their vows had been made, friends, and kin,

All those who were known to one another,

Feasted, having cleansed themselves of sin

And restored their strength, then drew together,

Embraced, and wept, ere battle should begin,

And uttered all those words the loving heart

Will seek to express ere friends must part.

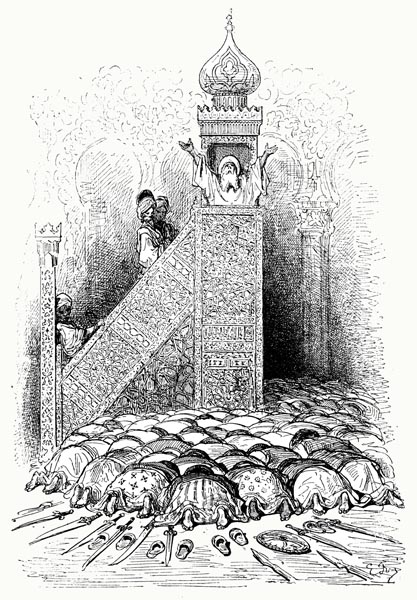

Within Bizerte’s walls their holy men

Prayed with the troubled people and, in tears,

Beat their breasts and, again and again,

Called upon their god, who, it appears,

Heard them not. The vigils and offerings, then,

That were promised, privately, to ease their fears;

The mosques, the domes with lettering engraved,

As eternal monuments, were they but saved!

When the imams had led them in prayer,

The people armed themselves, and manned the wall.

In Tithonus’ bed, Aurora the Fair,

Was slumbering yet, and shadows shrouded all,

As Sansonetto and Astolfo, there,

On each flank, waited for the battle-call;

Then, when Orlando ordered it, at last,

They attacked Bizerte, at the trumpet’s blast.

Canto XL: 15-19: The assault on the city

On two sides the city faced the sea,

Its other walls faced the level plain.

They were excellently made, built strongly,

Dating from ancient times in the main.

No signs of other bulwarks could they see,

For though Branzardo had sought to maintain

Solid defences, skilled masons he lacked,

And little time ere the place was attacked.

Orlando had charged the Nubian king

With clearing the walls of their enemies,

By means of the use of crossbow and sling,

Till none dared appear, and not to cease

From firing his missiles, nor retiring,

Till horsemen and foot could pass, with ease,

Beneath the walls, bearing stones and beams,

And other heavy gear, to work his schemes.

They hurled a mass of earth into the moat,

Passing the weighty loads from hand to hand,

Having blocked the flow of water at its throat,

Till now it was part marsh, part solid land,

It was quickly filled till naught could float,

And made level from the walls to the strand,

While Astolfo and Oliviero

Prepared the first assault, with Orlando.

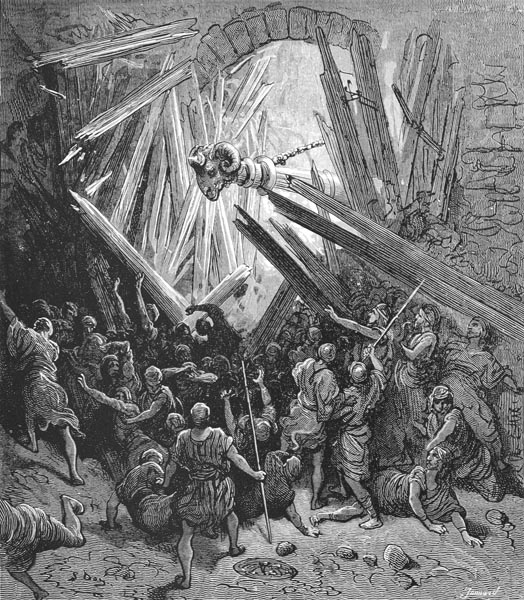

The Nubian force, impatient of delay,

And certain of the victory they’d attain,

Not anticipating danger, made their way

Sheltered by close shields above, in the main,

Bearing battering rams, in close array,

Towards the gates, to break all down, and gain

An entry to the town; advancing fast,

They found the foe equipped lest they passed.

Fire and steel, and stones from tower and wall,

Like a tempest, rained upon the Nubian force.

Shattering the planks and beams, in their fall,

Of those engines meant to win them, in due course.

In the darkness they could scare evade them all,

And many a man was slain o’er that concourse,

But once the sun had issued forth again,

Fortune turned her back on the Saracen.

Canto XL: 20-26: Brandimarte scales the wall

The attack was reinforced on every side

By Orlando, from both the sea and land,

Sansonetto with the fleet now did glide

Into the harbour, and approached the strand.

And, with slings, and bows, and engines, applied

His attentions to the foe, where they did stand,

While sending scaling ladder, sword, and spear,

To his comrades, and all kinds of martial gear.

Orlando, Brandimarte, Oliviero

Wrought fierce and furious battle, near the wall,

With the aid of the daring Astolfo,

He that had flown so high with ne’er a fall.

Each led a fourth of their host against the foe,

As they’d agreed before, bringing them all

Neath the battlements, or clustered at the gates,

Showing a courage set to tempt the Fates,

While proving their prowess, so as to show

Clear indication, midst that confusion,

To a thousand watching eyes also,

Of deeds full worthy of celebration.

Wooden towers were brought against the foe;

And, bearing many a mighty construction,

Trained elephants, a turret on each back

Reared high above the foe, in bold attack.

Brandimarte set a ladder gainst the wall,

Ascended, and to those below he cried;

Many a brave man followed, at his call,

For none could fear behind so brave a guide.

None noted or thought to note midst all,

If it would hold their weight once applied,

For Brandimarte, intent upon the foe,

Fought his way upwards, like those below.

Bracing hands and feet against the stone,

He leapt upon the wall, and whirled his sword;

Revealing all his skill, though all alone,

With blade and point, he sliced, skewered, and bored.

Then, suddenly, the ladder gave a groan,

And broke, neath the weight of those aboard,

And, but for Brandimarte, to the ground,

The Christians fell, a maimed and writhing mound.

And yet the knight, undaunted by its fall,

Not for one moment thought of vile retreat,

Though none of his own answered to his call,

While all the enemy looked to his defeat.

The Christians, fearful of what might befall,

Begged him to turn, but, gazing neath his feet,

He leapt within; the depth of that great leap

Was thirty yards, the wall there high and steep.

Yet he landed without hurt, upon the ground,

As though but wrought of straw, and featherlight,

And then tore into those who clustered round

Showing a prowess granted him of right,

Attacking these, and others that he found,

And scattering both these and those in flight,

Though those without, seeing the leap he made,

Had thought him now beyond all human aid.

Canto XL: 27-32: The others follow and take the city

Through the army ran the sudden rumour,

A murmur and a whisper, far and near,

From man to man, and with every murmur

That rumour grew, and magnified their fear.

To Orlando (amidst the thick as ever,

Where the cost to the foe would prove most dear)

And Oliviero and Astolfo, its flight

Penetrated; there the news did alight.

Those warriors, but most of all Orlando,

Who loved and prized bold Brandimarte,

On hearing that if they should linger so

They must yield their friend to the enemy,

Planted their ladders, and upwards did go,

Showing a proud, and noble, rivalry,

While appearing so fierce, and full of might,

That the Saracens trembled at the sight.

As, in some ocean that the storm-winds churn,

Mighty waves attack a floundering vessel,

Swamping now the prow, and now the stern,

Seeking an entry, midst that furious battle,

(While crew and pilot groan, and terror learn,

That ought to aid her, and yet lack the mettle)

Till at length a wall of foam sweeps all away

And where it entered, all the rest make play,

So, once that mighty trio had gained the wall,

They left a space where the rest could follow,

For upon a thousand ladders men could call,

And where they went a lesser knight might go.

Meanwhile the battering rams’ rise and fall

Breached the gates, with many a mighty blow,

So that, from many sides, men now might aid

Brandimarte, fighting on, unafraid.

With that force the seething waters maintain,

When the King of all Rivers overflows,

And carves a course o’er the Mantuan plain,

In his rage, tears the crops from the furrows,

Bears the pens, with the flock, in his train,

Drowns the dogs with the shepherd, and shows

But the tops of the elms, where fish now glide,

(Once the homes of birds) in his muddy tide;

With that same force, the impetuous host,

Pouring through every breach in the wall,

Seeking to slay the people of that coast,

And concerted resistance, thus, forestall,

Midst death and ruin, wrought their uttermost,

Hands dyed with blood, killing, plundering all,

Dealing destruction to that fair city,

(Proud Queen of Africa) without pity.

Canto XL: 33-36: Agramante is restrained from suicide

Every street was piled high with the dead,

While from innumerable wounds there flowed

A stream, that formed a moat, as deep and red

As that encircling Pluto’s dark abode.

From house to house the roaring flames now spread,

Mosque, palace, portico their fabric showed,

And shattered mansions echoed to the sound

Of cries and pleas, where mercy ne’er was found.

The victors issued forth from that ill place,

Bearing the spoils, one a vase, another

Grasped silver plate, wrought by that ancient race,

Or dragged away a child, a grieving mother;

Rape and pillage did the conquerors disgrace,

Which nor Orlando nor any other

Could now prevent, not the good Astolfo,

Nor Brandimarte, nor Oliviero,

By whose blade Bucifaro had been slain,

That king of Algeciras, at a blow;

Having lost all hope, midst a world of pain,

His own hand took the life of Branzardo;

While pierced by three deep wounds, staunched in vain,

Folvo was captured, the Duke of Pardo,

And thereafter died, the third to whose care

Their monarch had entrusted his realms there.

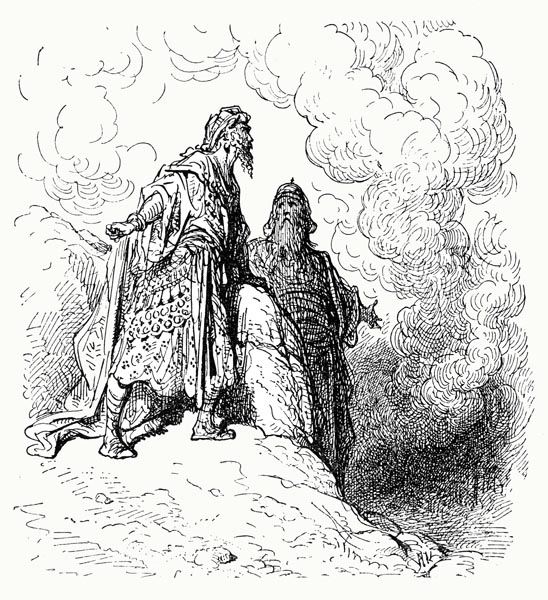

Agramante, who’d deserted his fleet,

And with old Sobrino had taken flight,

Wept both long and hard at their defeat,

When the burning city came in sight.

His Bizerte dying, his eyes did greet,

And drawing closer in that dreadful light,

His thought was but to end there, in his woe,

Yet was restrained by the wise Sobrino.

Canto XL: 37-39: Sobrino counsels him

Sobrino cried: ‘What greater victory

My lord, could your enemy ever know

Than hearing of your death, for would not he

Hope to rule Africa, untroubled, so?

With you alive, tis denied him, wholly,

For he as yet has cause to fear the foe,

Knowing that she will not be his for long

While you yet live, and your grip is strong.

Your death deprives your people, suddenly,

Of their last hope, all that to them remains.

If you yet live, we trust we shall be free,

Redeemed from wretchedness, and all our pains,

While, if you die, we face captivity,

And Africa, a slave, your enemy gains.

Live, my lord, if not for yourself alone,

Live and grant hope to those who are your own.

Your neighbour, Egypt’s Sultan, will supply

Men, and wealth enough, to aid you ever,

Scarce looking with a favourable eye

On Charlemagne’s attempts on Africa;

Norandino your kinsman, he would try

By every means your realm to recover;

Persian, Armenian, Turk, Arab, Mede,

All will assist you, in your time of need.’

Canto XL: 40-42: Ariosto on the danger of trusting in allies

With such and like words, the old counsellor

Sought to raise hope in Agramante’s mind,

Of winning back his realms in Africa,

Though, in his own, he was perchance resigned

To another end entirely; for, ever,

To an evil pass he is brought, we find,

That’s led to forsake his land and honour,

And look to barbarians for succour.

The like, Hannibal and Jugurtha knew,

And others in former times, who did so;

Ludovico il Moro, in our own day, too,

Held by France, his ally become a foe.

Through such examples (I speak to you,

My lord Ippolito) wise Alfonso,

Your brother, was ever wont to decry

Those that on others, not themselves, rely;

So (throughout that war waged in anger

By a Pope filled with deep ire and disdain,

And though his own forces were the lesser,

His friend driven from the Italian plain,

Whose Naples was lost, seemingly forever,

While France’s Charles the Eighth therein did reign)

Neither threats nor promises swayed your brother

That ne’er would yield his dukedom to another.

Canto XL: 43-46: Agramante reaches an isle, and finds Gradasso there

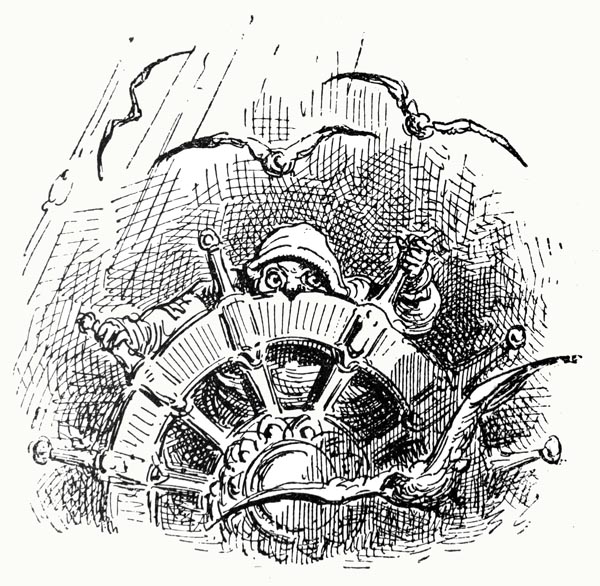

Yet Agramante headed for the East,

And was far out on the deep when a gale

Blew hard offshore, that, before it ceased,

Attacked the vessel, and did near prevail.

The master at the helm, as it increased,

Cried: ‘My lord, I find tis of no avail

To hold this course (eying the sky above)

Against the storm no boat like ours dare move.

If you, sire, will take heed of my counsel,

There is an isle to larboard, close nearby;

It seems to me the place would serve us well

For shelter till this tempest passes by.’

The king gave his assent, thus it befell

That they escaped, that island being nigh,

Which serves as refuge for the mariner,

Twixt lofty Etna and the coast of Africa.

The isle was uninhabited, grown o’er

With juniper and myrtle, granting there

A peaceful sanctuary, a pleasant shore,

Home to roe and fallow deer, and hare,

With its location known, but little more,

Except to fishermen whose nets would share

The silence, drying, while the fish sank deep

Neath peaceful waters, seemingly asleep.

There they found another vessel though,

Driven by the gale to that fair island,

Which had carried the bold King Gradasso,

From Arles, and now was beached on the strand,

Warm greetings, worthily, they did bestow,

Clasping each other tightly by the hand,

For they were bosom friends, as you’ll recall,

Companions in arms neath Paris’ wall.

Canto XL: 47-50: Gradasso offers to counter the incursion

With much displeasure Gradasso now heard

Of the king’s adverse fortune, and consoled

Agramante, and now offered, in a word,

His counsel, for twas worth its weight in gold,

Warning of the harm that might be incurred,

Through seeking aid from Egypt, for: ‘Of old,’

He said, ‘tis ill for exiles to seek aid

In that country where Pompey was unmade.

Since, helped by Ethiopia’s Senapo,

Men are come to steal Africa from you,

Led forth by this Englishman Astolfo,

And now have burnt fair Bizerte too;

While with their army fights Orlando,

That was bereft of sense, restored anew;

I think I know the perfect remedy

To set your troubled mind at liberty.

For love of you, I’ll undertake to fight

The Count in single combat, publicly.

If he were made of bronze or steel that knight

But slight defence would he find from me.

Once he is dead, the Christians, in might

Like lambs before the hungry wolf shall be.

Next, I’ve thought (tis easily put in hand)

How to drive the Nubians from your land.

I’ll rouse the other Nubians, who hold

To the Muslim faith, on our side the Nile,

And the Arabs, and Somalis (rich in gold,

And men, and steeds) to foes of ours hostile,

With Persians and Chaldeans, now controlled

By my sceptre, who those same foes revile,

And, on our enemies, I’ll then make war,

Drive them all forth, and your fair realm restore.’

Canto XL: 51-55: They issue a challenge to Orlando

Gradasso’s second offer much appealed,

Arriving, indeed, so opportunely;

And King Agramante scarcely concealed

His delight at Fortune’s generosity,

In bringing his ship there; it appealed,

This last suggestion, yet he, sternly,

Rejected King Gradasso’s thought, for he,

Though it might reclaim Hippo, could never

Agree to what impinged on his honour.

‘If Orlando must be challenged, it is I,’

He cried, ‘that must undertake the labour.

I shall be ready; may Allah, thereby,

Work his will, in good or fatal manner.’

‘Let us pursue that idea; and why

Not agree to work the scheme together,

For my next thought is that we both should fight,

I, Orlando, and you some other knight.’

‘I care not which,’ replied Agramante,

‘So long as I am there, for I contend

I’d find in war no better company,

Than you, though such I sought to the world’s end.

‘And what then,’ old Sobrino said, ‘of me?

If you would say I’m old, then condescend

To grant my deep knowledge of chivalry,

And long experience; when in peril,

Youth ever benefits from good counsel.’

Sobrino was robust and vigorous

Despite his years, and his skill well-proven,

And he cried that he was still as courageous,

And strong, as in his youth, more so even.

They agreed his claim was meritorious,

And swiftly briefed a messenger, and then

Bade the man sail for Africa, and go

And bear their challenge to Count Orlando:

That he should with an equal company,

Attend them, upon Lampedusa’s shore,

Which is an islet in that self-same sea

Whose waves about their present isle did roar.

The messenger went on his way swiftly,

His vessel driven on by sail and oar,

Reached Bizerte, and there found Orlando

Dividing the spoils wrestled from the foe.

Canto XL: 56-61: Which he readily accepts

The challenge from Gradasso, Agramante,

And Sobrino, now announced publicly,

Was pleasing to the Lord of Anglante,

That rewarded the king’s envoy, richly.

He’d heard it said, among his company,

Durindana was Gradasso’s, whereby he

Had resolved to sail to far India,

There, that famed weapon to recover,

Not expecting to meet the king elsewhere,

Who had quit, so he’d heard, the shores of France,

Now a nearer place would host the affair,

Where he hoped that same mission to advance.

And then Almonte’s prized horn, near as fair,

And Brigliador, spurred his acceptance,

Since both of those possessions he knew

Agramante held; yearning for those too,

He chose as his companions in the fight

Brandimarte and Oliviero,

Both were proven warriors of might,

And that they loved him, truly, he did know.

Fine steeds and sound armour, strong yet light,

And swords and lances he desired also,

To arm all three of them (to you tis known

Why none was there possessed of his own).

Orlando (as I’ve explained before)

In his madness, had scattered his abroad,

While Rodomonte, on the Rhône’s steep shore,

Had added those of the knights to his hoard.

Then, few in Africa such armour wore,

For rare examples could that land afford

Of the finest arms, while Agramante

Had taken such to France’s fair country.

What old and rusted armour could be found

Orlando had brought, and rendered bright,

Meanwhile he paced o’er the sandy ground

With the other two, speaking of the fight.

Three miles beyond the camp, gazing round,

A vessel, on the water, met their sight,

In full sail, and approaching nigh the shore,

With no pilot at the helm, as on she bore.

She lacked a helmsman and, it seemed, a crew,

Driven where’er the wind and Fortune led,

Nearing the land, for a strong breeze yet blew,

Until she grounded on the strand ahead.

But ere I speak of this strange sight anew

My love for Ruggiero seeks instead

To return me to his story, and show

What took place betwixt him and Rinaldo.

Canto XL: 62-68: We return to Ruggiero and his duty to Agramante

Of those two mighty warriors I write

Who had retreated from the fierce mêlée,

On seeing the treaty broken outright,

And every squadron in wild disarray,

And sought to learn from others, if they might,

Who had perjured himself on that sad day,

And caused such havoc on the open plain:

Whether Agramante or Charlemagne.

Meanwhile a servant of Ruggiero’s

Cautious, astute, and loyal to the knight,

And who, when the conflict first arose,

Had taken care to keep his master in sight,

Now brought his sword and steed, amidst the throes

Of the conflict, so Ruggiero might

Aid his friends. He grasped the sword and mounted,

Yet sought not amidst them to be counted.

He departed, but, ere he went, renewed

The pact that he had struck with Rinaldo:

That if he found Agramante had pursued

This evil course, his service he’d forgo.

All that day he took no part in the feud,

One thing alone occupied Ruggiero:

Which leader had committed perjury,

Was it Charlemagne or Agramante?

All, he spoke with, said that Africa’s king

Had been the first man to break the treaty.

Ruggiero loved him; thoughts of quitting

His service could not be mused on lightly.

The Moorish warriors were fast dispersing,

(As I have said before) all from the heady

Heights of Fortune to the depths now hurled,

As she pleased, whose strange fancies move the world.

Ruggiero debated in his mind

Whether he should follow Agramante,

Or keep from Africa, remain behind,

Prompted thus by his love for his lady;

To the former course scarcely resigned,

And so grieved by the thought of perjury

If he now broke his pledge to Rinaldo,

That, restive, he could neither stay nor go.

For his noble heart was equally pained

By his thoughts of dereliction of duty,

That to mere cowardice, if he remained,

Or lack of true honour, would most likely

Be ascribed, or as treachery explained,

And be condemned by the loyal many;

For they would say that no such pledge should bind,

Seeming unjust, unlawful, to their mind.

All through that day and the ensuing night,

He remained alone, and the next day too,

Debating what, in good conscience, he might,

Or for fear of perjury might not, do.

At last, on Africa he turned his sight,

Deeming that to his lord he must prove true;

Moved by his love for her he did adore,

And yet by honour and by duty more.

Canto XL: 69-72: Dudon and his men disembark

He then made for Arles, where he hoped to find

A ship to carry him to Africa,

But only the Moorish dead, left behind,

He saw there; no vessels sailed the river;

For so King Agramante had designed,

Taking the best, and burning every other.

His hopes dashed he slowly turned away,

Then took the coast-road leading to Marseilles.

On some vessel he thought to lay his hand,

That, through force or plea, might serve his turn.

There, Dudon’s mighty ships had now made land,

With Agramante’s roped to bow and stern.

You could scarce have passed a grain of sand

Between them all; those that had failed to burn

Of the enemy fleet, to the harbour brought,

With many a prisoner, captive, to that port.

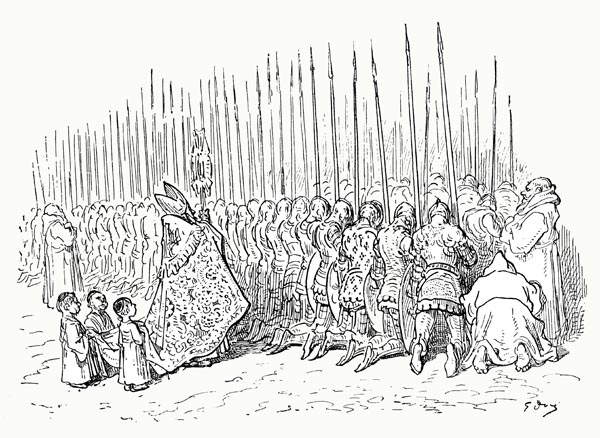

The Moorish ships that had survived the fight

Those not wrecked or sunk, or consumed by fire,

(Save for a few that fled) the Danish knight

Had led to Marseilles, his victory entire.

Seven Moorish kings, appalled at the sight

Of their ruined fleet, their situation dire,

Had yielded their seven ships to the foe,

And now stood mute and weeping, full of woe.

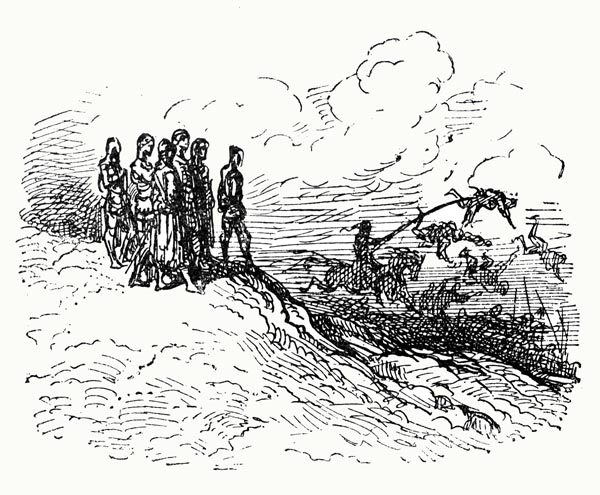

Dudon, once disembarked and on dry land,

Thought to find Charlemagne that very day;

Of the captives, and the spoils now on hand,

He arranged a vast triumphal display.

The captives were drawn up along the sand,

Flanked by Nubian guards, in joyful array,

Who shouting, happily, with loud acclaim,

Made the shore around ring to Dudon’s name.

Canto XL: 73-78: Ruggiero encounters Dudon

There, arrived, in hope, brave Ruggiero,

Thinking the fleet that of Agramante,

On seeing it afar, and neared the foe,

But recognised, on viewing all, more clearly,

Those seven captive kings, Bambirago,

Nasamona’s, Farurante, Agricalte,

Rimedonte, Balastro, Manilardo,

That stood sad-browed and weeping, full of woe.

Ruggiero, who loved them, could not bear

To leave them in that unhappy state,

He knew that there was little use in prayer,

Sheer force was needed, ere it was too late.

He lowered his lance and, scattering all there,

Sought his power and skill to demonstrate,

Then swung his sword and, charging those around,

In a trice, had stretched a hundred on the ground.

Dudon heard the sound of arms, and saw

The destruction wrought by this unknown knight,

He witnessed his people troubled sore,

In fear and anguish, wailing, put to flight.

He called for sword and steed, his helm he bore,

And else was ready-armoured for the fight

Then mounting his steed, and seizing his lance,

Showed he was yet a paladin of France.

Then, shouting to all about to stand aside,

He spurred his bold courser against the foe,

While hope to the captives’ hearts was supplied,

As another hundred fell to Ruggiero;

Who, when Dudon’s arrival he espied,

Mounted alone (the rest on foot did go)

Deeming him the leader, charged outright,

Driven by the desire to prove his might.

Now Dudon was already on his way,

But Ruggiero having dropped his lance,

In disdain, the knight flung his own away,

Not wishing to gain thus from his advance.

Ruggiero finding such chivalry in play,

Said to himself: ‘Some perfect knight of France,

This man must be, that thus refrains from wrong,

Sure, to Charlemagne’s court he must belong.

If I can achieve it, I would know his name,

Before aught else in battle here is done.’

Thus, he asked, and was informed by that same

That here was Dudon, Uggiero’s son.

And then the Dane to the like now laid claim,

And from Ruggiero his title won;

Their names now exchanged, the valiant foes

Shouted their challenges, and came to blows.

Canto XL: 79-82: But refrains from injuring him

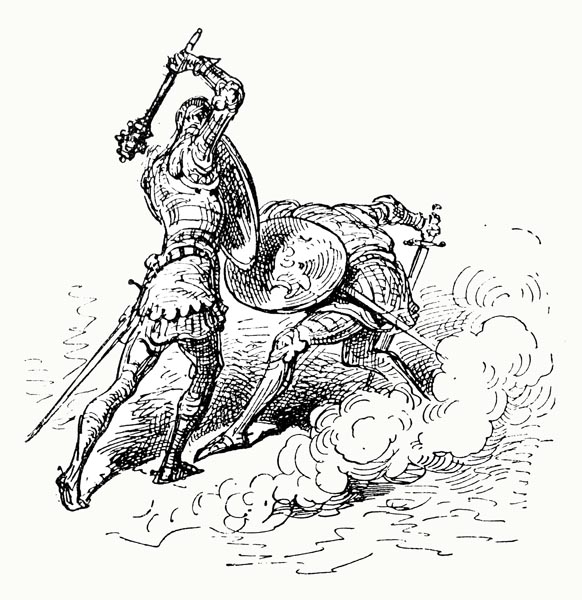

Brave Dudon, there, wielded that iron mace

That in a thousand fights had brought him fame,

Where he’d upheld the honour of his race,

And maintained the glow of Uggiero’s name.

That sword which pierced the best-defended place,

That peerless blade, that finest plate could maim,

Ruggiero drew, and prepared to try

His strength against the Dane’s, with steely eye.

Yet because the youth ever kept in mind

The need not to sore offend his lady

Which he knew he must do, if she should find

He had shed her kinsman’s blood, wantonly,

(For, instructed in the lineage of his kind,

He knew courteous Dudon’s mother to be

Armelina, of that Beatrice the sister

That was, in turn, Bradamante’s mother)

He now refrained from harming the other,

And seldom struck to wound, if he could;

His shield deflected one blow, and another,

Whene’er the mace descended seeking blood.

The good Bishop Turpin claims, moreover,

That he might have slain Dudon where he stood,

Yet ever when required to land a blow

The sharp edge of his blade did thus forego,

But used the flat as fiercely, even so.

Ruggiero’s sword was tempered soundly,

And, in a noisy game of to and fro,

He belaboured Dudon, so forcefully,

And so dazed the man, with blow on blow,

The latter scarce could keep from injury.

I’ll spare my hearers and, with one last rhyme,

Save this canto’s tale for another time.

The End of Canto XL of ‘Orlando Furioso’