Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XIX: Angelica and Medoro

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XIX: 1-5: Medoro is surrounded

- Canto XIX: 6-10: And ultimately made captive

- Canto XIX: 11-16: Medoro is wounded, against Zerbino’s wish

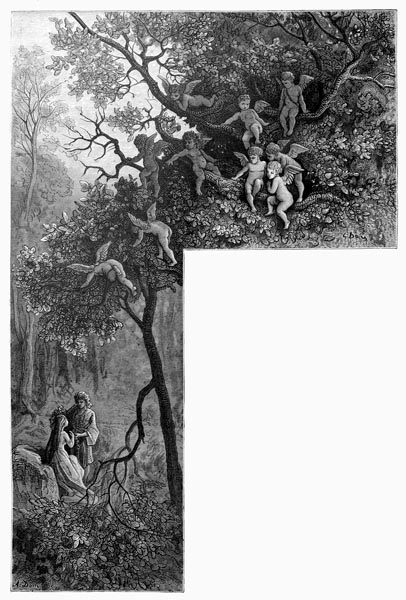

- Canto XIX: 17-20: Angelica comes upon him, close to death

- Canto XIX: 21-26: And tends to his wound, restoring him

- Canto XIX: 27-30: Angelica falls in love with Medoro

- Canto XIX: 31-36: The pair enjoy wedded bliss

- Canto XIX: 37-42: They set out for her land of Cathay, and approach Barcelona

- Canto XIX: 43-49: We return to Marfisa and the knights amidst the storm

- Canto XIX: 50-55: They are driven to Latakia, in Syria

- Canto XIX: 56-59: The captain explains his reluctance to disembark

- Canto XIX: 60-64: They are towed to the shore

- Canto XIX: 65-68: An old woman confirms the terms of entry to the city

- Canto XIX: 69-75: Marfisa acts as their champion

- Canto XIX: 76-87: And soon deals with nine of the warriors

- Canto XIX: 88-91: The tenth, their leader, offers her a respite

- Canto XIX: 92-97: She refuses, and the pair engage

- Canto XIX: 98-108: They agree to postpone the fight

Canto XIX: 1-5: Medoro is surrounded

None can know to what extent they are loved,

Once risen to the summit of the wheel,

For by true friend and false they are approved;

Both would seem an equal sentiment to feel.

Yet, if their prosperous status is removed,

The flattering multitude themselves reveal,

While those who love their master from the heart,

Though he dies, faithfully, perform their part.

If the heart could be viewed, as is the face,

He who is great and favoured most of all,

And he to whom his lord shows little grace,

Would change roles, one would rise the other fall.

The humble man the prouder would replace,

While the latter would answer to his call.

Let us turn to Medoro, who we know

Loved his master, whether living or no.

That unhappy youth sought the nearest way

To save himself, amidst the tangled wood,

Heavily, indeed, did his burden weigh,

That he’d not leave behind, although he could.

Ignorant of the place, he went astray,

So, in a thorn-brake, half-concealed he stood.

Meanwhile, Cloridano, his shoulders free,

Sought a place of safety, as he did flee.

He knew not if his dear friend would follow;

Though none did so, as far as he could tell,

Yet once he found that he’d lost Medoro,

He felt as if his heart were lost as well.

‘Ah, how was I so negligent? What woe!’

He exclaimed, ‘Thinking of myself, I fell

So deeply into error I know not where

I have left him, nor when, in this affair!’

With that, he plunged again amidst the trees,

Threading his way through the tangled maze,

And so retraced his path, with great unease,

Sensing the danger, fearing death always.

He heard the riders calling without cease,

Threatening cries; sought to garner every phrase;

Till, at last, his Medoro’s voice he heard,

Who stood, alone, as round him men conferred.

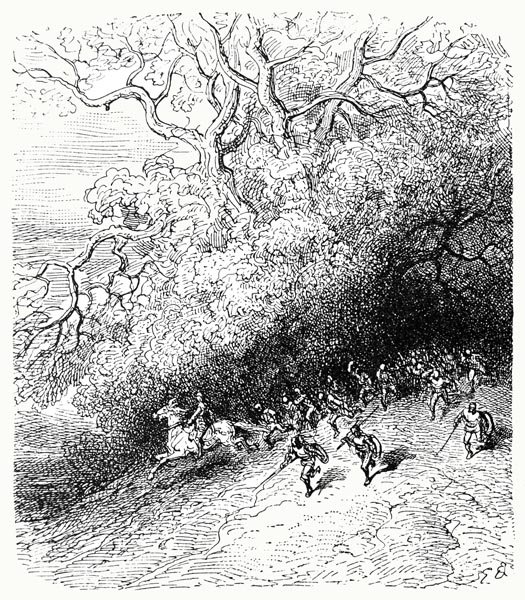

Canto XIX: 6-10: And ultimately made captive

A hundred horsemen ringed the place about.

Zerbino ordered them to seize the lad;

He retreated to the wood, with a shout,

(Still bowed beneath his burden, I should add).

Through stands of beech, oak, elm, ash, in and out

He went, bearing his master, as he had,

Till, wearily, he laid him on the grass,

Lacking strength to escape his foes, alas.

As a she-bear, that Alpine hunters face

Who’ve assailed her in her mountain den,

Will defend her cubs in that stony place,

And growl in her fierce anger at the men,

While rage and tenderness she must embrace,

Unsheathing her sharp claws, yet, now and then,

Drawing back, as love urges a retreat

To shield her young, though wrath their spears would meet,

So Medoro! Cloridano unsure

How to aid him, seeking death by his side,

Yet not prepared to die until ten more

Of the foe met the dust, to there abide,

Set his sharpest arrow to the bow he bore.

And launched a dart, that through the air did glide,

To pierce a Scottish rider through the eye;

He fell stone dead, to earth, with scarce a sigh.

His companions now turned towards the place

From which the fatal missile had emerged,

While Cloridano took another pace,

And launched a second dart; onwards it surged,

To strike a second rider in the face

As a charge, against this hidden foe, he urged;

It pierced him through the open mouth, and throat,

And cut his speech short, on that very note.

But now the leader of the troop, Zerbino,

Losing his patience at the sorry sight,

Rode with fury towards young Medoro,

Crying: ‘Now do penance for the knight!

As, with one hand, he grasped the hair below,

He dragged the youth to him, held upright,

Yet viewing that loyal and tender face,

Took pity on him, and held off a pace.

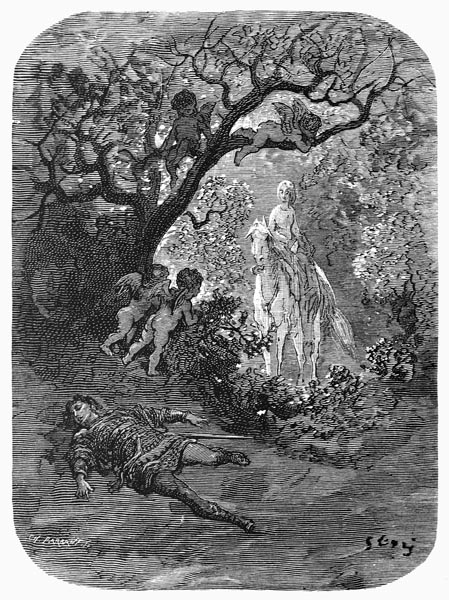

Canto XIX: 11-16: Medoro is wounded, against Zerbino’s wish

Upwards, at him, Medoro stared, and cried:

‘By your God, be not so cruel, sir knight,

As to deny the king I stand beside

A fitting burial, as is his right.

I ask naught else of you; come death, outright,

For life I care not, nor shall long abide;

I wish no more than that this life afford

Sufficient space yet to inter my lord;

And if you needs must feed the wolf and crow,

In your wrath, and act like Theban Creon,

I’ll be their feast; yet, in the tomb, bestow

All that remains of King Almonte’s son.’

Thus, with pleasing grace, spoke Medoro,

Words that might mountains move, and so he won

Zerbino’s heart to pity and respect,

That could not such a noble plea reject.

But at that moment, a malicious knight,

Possessing scant deference for his lord,

With a bold thrust of his lance, pierced outright

The lad’s broad chest, his death all but assured,

The cruel deed a more than bitter slight

To Zerbino who the lad’s wound deplored;

For he saw him fall earthwards, as if dead,

As all there believed, viewing how it bled.

Greatly angered, and grieved, was Zerbino,

‘You’ll not go unavenged!’ the warrior cried;

And, filled with dire intent, he aimed a blow

At that horseman who had his will denied.

But the latter escaped him, even so,

Sought an avenue, and away he hied.

Cloridano, who had seen Medoro fall,

Sprang from the wood, eager to slay them all.

He hurled his bow away, he grasped his sword,

Whirling it about him; though death, he thought,

More than vengeance, his action would afford.

Yet he stained the ground with blood as he fought

Midst the blades, and many a hit he scored,

In his anger, while that swift revenge he sought;

Till feeling his strength departing, slow,

At length, he fell to earth, beside Medoro.

Meanwhile the Scots rode after their leader

Through the dense wood, urged on by their disdain

At having left the dying clasped together,

(Though one was yet alive) upon the plain.

There young Medoro lay, beside the other,

As, from out his wound, the life-blood did drain,

And would soon have perished altogether,

Had not one appeared who aid did proffer.

Canto XIX: 17-20: Angelica comes upon him, close to death

A maiden chanced to come upon the place,

Who, though rustic and humble was her dress,

Bore a noble manner, a lovely face,

And seemed a regal presence, nonetheless.

Tis so long since I did her tale embrace,

You might fail to recognise our princess:

Angelica it was, still riding on her way,

Proud daughter of the great Khan of Cathay.

Angelica, once she’d again retrieved

The ring Brunello had taken from her,

Was filled with monstrous pride, for she believed

That all the mortal world was beneath her;

She went alone, her journey unrelieved

By any friendship this earth might offer,

And scorned to consider as a lover,

Orlando, Sacripante, or some other;

And, above all else, she now repented

Of loving bold Rinaldo, long ago,

Believing that to have, thus, consented,

Had shamed her, receiving one so low.

Love such boundless arrogance resented;

He refused to let the matter rest, and so,

Where young Medoro lay, he took his stand,

And waited for her, bow and dart in hand.

When Angelica saw the young man there,

Near to death, sorely wounded in the chest,

(That for his master had shown greater care

Than for himself) pity stirred, in her breast,

A feeling which she was unused to share,

Softening the heart that it now addressed,

Tempering its harshness; her face grew pale,

(And more so, when she came to learn his tale).

Canto XIX: 21-26: And tends to his wound, restoring him

She now recalled to mind the doctor’s art

Of which she was apprised in India;

For, it seems, such knowledge they impart

In that country, and do praise it ever;

For, with little use of books, but by heart,

Fathers pass it on to son or daughter;

And thus, with the juice of herbs, she now thought

To restore him to life; and these she sought.

She remembered one she’d seen while passing

Through a pleasant place, whether dittany

Or pansy (that panacea) growing,

Or I know not what, whose powers fully

Served to staunch a wound, while greatly easing

Every painful pang and spasm, swiftly.

She found and culled the herb, not far away

And returned to Medoro where he lay.

While doing so, she came upon a cowherd,

Mounted on horseback, there, amid the wood;

He was searching for a heifer, so she heard,

Two full days lost, in that wild neighbourhood.

She brought him with her, with scarce a word,

To where the warrior’s last strength, with blood,

Was staining the ground, dyed deeply now,

While winged Death yet hovered o’er his brow.

From her palfrey, Angelica descended,

And the cowherd dismounted, there, also.

Next, between two stones, the herb she pounded,

And scooped it in her hands when she’d done so;

Then the wound she infused, and surrounded,

With the juice, and smeared the rest below,

On belly, waist and hips, and such its power

It staunched the blood, and roused him, in an hour.

Its force imbued him with such strength that he

Could even mount the horse the cowherd rode,

Though Medoro would not depart, till he

The king and Cloridano had bestowed,

For he now interred the two, reverently.

Then, where’er the maiden went, he followed;

And, she, beneath the cowherd’s humble roof,

Remained with him; of pity certain proof.

Nor wished she to depart till he was sound,

Such was her liking for this warrior,

And such the maiden’s pity, rare, profound,

That, at first sight, had so stirred within her.

Then his address and courtesy, she found,

Had wounded her heart, in secret manner,

Wounded her heart and warmed it, by and by,

Until with amorous flame the maid did sigh.

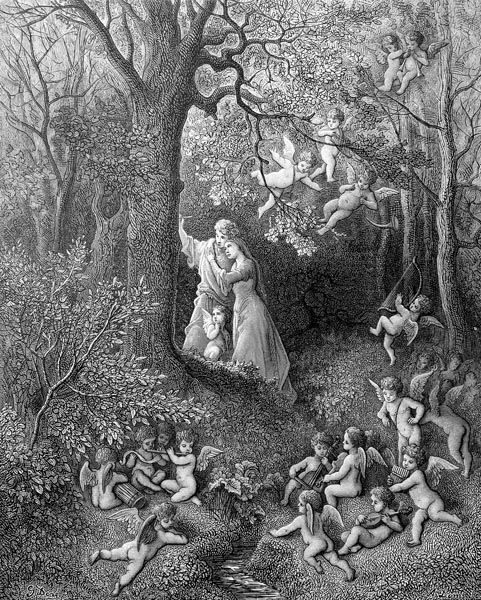

Canto XIX: 27-30: Angelica falls in love with Medoro

The cowherd dwelt in a well-built cabin

On flat ground, twixt two hills, in a fair glade,

With his wife and children; and there, within,

All had lately been re-worked, and remade.

And here Medoro to full health did win,

Through the kind ministrations of the maid.

Who felt a sharper pain, despite her art,

Than ere Medoro felt, deep in her heart.

A sharper pain, a wound far more profound,

From an unseen arrow, she did suffer,

From those fair eyes, those golden locks, unbound,

A wound the winged Archer had dealt her.

A fire she felt, its burning wrapped her round,

Yet cared less for herself than for the other,

Scarce thought about herself, her sole intent

To ensure that her tormentor was content.

The more Medoro’s wound closed and healed,

The more hers ached and opened; heaven knows,

The youth thrived, she languished, yet concealed

Her fever: now she burned, and now she froze.

More beauty every day his form revealed,

While she but wasted, like the springtime snows

That, born unseasonably, melt away,

In open fields, caught in the Sun’s bright ray.

If she were not to die, she needed now

To aid herself, and that without delay;

Nor should she wait till he might such avow,

If she to her desire would find a way.

Without a trace of shame upon her brow,

Her tongue as bold as were her eyes that day,

For the wound he’d dealt her, unwittingly,

She begged him to show kindness and pity.

Canto XIX: 31-36: The pair enjoy wedded bliss

O Count Orlando, O Sacripante,

Say what the prize is for all your valour?

Say what your service earns you, now, what fee,

What reward for all your worth and honour?

Show me, in truth, a single courtesy

Old or new, that she did ever offer,

In recompense for all the pain you’ve felt

On her behalf; for all the pain she’s dealt.

Oh, if aught could your former life restore,

How bitter, Agricane, this would seem!

You whom she scorned endlessly, before,

Sad slave to her cruel, inhuman, scheme.

O brave Ferrau, O you, the thousand more,

Unsung, whose fond desire proved but a dream,

The thousand deeds you wrought for her, but vain,

To see her clasped in those arms now, what pain!

For Angelica allowed this Medoro,

To cull the virgin rose, untouched before.

None was so fortunate, till then, to know

That garden, that so fair a flower bore.

Sacred ritual they employed also,

To honour the thing, yet veil it o’er,

A marriage Love predicted, born of strife,

And whose sole witness was the cowherd’s wife.

Beneath that humble roof, the pair were wed,

With what solemnity they could achieve;

There, for a month or more, time swiftly sped,

They found delight together, I believe.

The lady’s eyes upon her husband fed,

Nor life without him could she e’er conceive,

Nor, arms about his neck, could ever tire

Of seeking, thus, to sate her fond desire.

Whether she kept within or wandering wide

And far beyond, at morn or eve, she strayed,

She had the fair youth ever at her side,

In some green meadow, or fair woodland glade;

Or in some cave, from noonday heat, they’d hide,

No less pleasant and welcome for its shade

Than that which Dido and Aeneas sought

True witness to their secret, tempest-fraught.

Amidst such pleasures, where’er some fine tree

Cast its shadow on a fount, or flowing stream,

His knife, her pin, at work there, instantly,

Would carve the bark (or stone if it did seem

Quite soft) in a thousand places, deeply,

Or within, on the walls, in a like scheme,

‘Medoro’ and ‘Angelica’ they traced,

With diverse knots, prettily interlaced.

Canto XIX: 37-42: They set out for her land of Cathay, and approach Barcelona

When she concluded the length of their stay,

Had been sufficient, she framed a design,

To return to India, and Cathay,

And a crown to Medoro there assign.

A bracelet, on her arm, she had alway,

Gold set with gems, a token and a sign,

Of Count Orlando’s love, and this she’d borne,

For many a day, and happily had worn.

It had been bestowed on Ziliante,

When hid beneath the wave, by Morgana,

And he (once restored to Monodante,

His father, through Orlando’s great valour)

Gave it to Orlando; a lover, he,

One that deigned to wear that bracelet ever;

With intent to gift it to his fair queen,

Angelica, of whom we speak, I mean.

Yet not for love of that knight she wore it,

But because it was rich and finely wrought;

And, thus, she felt so great a love for it,

That, beside it, she held others as naught.

In that Isle of Tears, Ebuda, she bore it

On her arm, by some privilege unsought,

When exposed, all naked, to the whale,

By that inhospitable folk (you’ve heard the tale).

There being little else she did possess

That she might offer as a small reward

To the man and his wife, for their kindness

In granting two fond lovers, bed and board,

She bestowed on them the bracelet, no less,

That some memory of her it might afford.

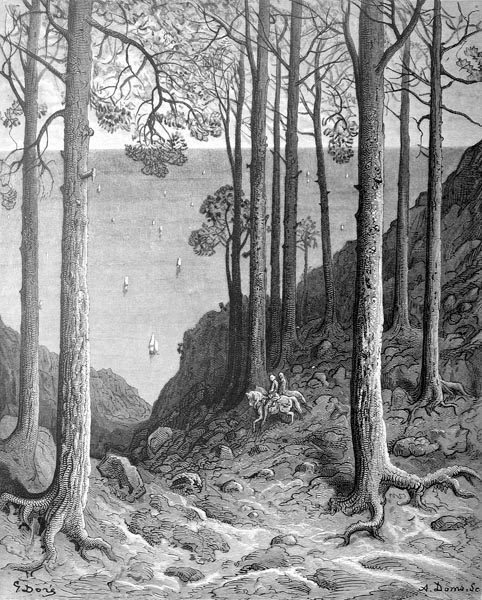

Then to ascend the mountains they were fain,

The Pyrenees, dividing France from Spain.

At Valencia or Barcelona,

The couple thought they might awhile remain,

Until some vessel chose to weigh anchor,

And set sail for the Levant, once again.

They first saw the sea beyond Girona,

Having descended to the open plain;

With the coast to their east, sure but slow,

To Barcelona’s city they did go.

Yet, ere they reached it, they met a madman,

Crouched upon the sand, close to the water,

Who like a wild boar, or some pagan clan,

Was daubed in filth and foul mud, all over.

He attacked as fiercely as (when it can)

A malicious dog assails the stranger,

And annoyed them, and put them both to scorn.

But for Marfisa, once again, I’m borne.

Canto XIX: 43-49: We return to Marfisa and the knights amidst the storm

Of Marfisa, Astolfo, Grifone,

Aquilante, and all the rest, I’ll tell,

That, facing death, pursued their journey

O’er the waves, scarce countering the swell;

While ever more threateningly and fiercely

The mighty waves upon their vessel fell.

Three days, entire, the wicked gale had blown,

And not one sign of abatement had shown.

The hostile breakers tore the deck apart,

And the tall aftercastle at the stern,

While whate’er was left of any other part

Was hurled into the water, in its turn.

Here, the captain stood, head bowed to a chart,

By which he might their troubled course discern,

By a lantern’s flame, that the wind did fight,

There, another, on the bilges, shed a light.

One at the stern, another at the bow,

Observed the sand sifting through a glass,

And at each half-hour, gazed, at poop and prow,

To watch lest some feature they might pass,

Then, each with his chart, amidships now,

Would search for a sight of some landmass,

While the seamen clustered there, together,

At the captain’s call, and faced the weather.

One called, loudly: ‘Off Limassol are we,

Midst the shoals,’ another: ‘We are nigh

Those perilous reefs close to Tripoli,

Where many a shipwrecked vessel must lie.’

Another: ‘Antalya’s coast we’ll see,

Whose currents make many a captain sigh.’

Each championed his opinion, eagerly,

All oppressed by fear and dread, equally.

On the third day, the wind blew spitefully,

And angrier the breakers then became,

While the one drowned the foremast in the sea,

The other did both helm and helmsman claim;

Harder than marble, solid steel was he

That failed to dread the power of those same.

Marfisa who had ever felt secure,

Denied not, on that day, she feared their roar.

A pilgrimage some vowed, to Mount Sinai,

To Cyprus, Rome, or to Galicia,

Or some other sacred place, by and by,

Ettino’s Virgin, or the Holy Sepulchre,

Meanwhile their ship was tossed twixt sea and sky,

Both elements seeking, now, to conquer,

Her mizzen-mast removed by the master,

That she might labour less midst the water.

The bales and chests of substantial weight

Were hurled, from stern, prow, gunwales, overboard,

And every hold and cabin, filled of late

With rich merchandise, was cleared of its hoard;

While the sailors pumped the importunate

Waters from the bilge, sea to sea re-poured;

Or, where plank was torn from plank, stemmed the flow,

Which the pounding waves had started below.

Canto XIX: 50-55: They are driven to Latakia, in Syria

They laboured in such misery and woe,

Four days entire, in a nigh helpless state.

The waves would have won the victory so,

If their fury had refused to abate.

But, with St. Elmo’s fire a lance did glow,

(Bringing them hope of a far better fate),

Within a ship’s boat, stowed at the bow,

For the topmost spar was shattered now.

On viewing that most lovely show of light,

All the mariners fell down on their knees,

And prayed for fairer weather, calm and bright,

In tears, as they voiced their trembling pleas.

The cruel tempest vanished then, outright,

And the vessel floated midst quieter seas.

The mistral and the savage cross-winds died,

Only a strong south-westerly did abide,

Which blew forcefully across the water,

And sent the breath from its dark mouth abroad,

Driving the current neath the surface faster,

Such that it did them greater speed afford

Than a peregrine falcon (that stoops swifter

Than any hawk) as through the waves they bored.

The captain feared that on, to the world’s brink,

They’d be borne, or be torn apart, and sink.

Gainst this, the captain knew a remedy,

Employing a sea-anchor; once in play,

The float and line, paid out steadily,

By two-thirds at least, now slowed their way.

His wise thought (and still more the augury

Of the saint whose fire had shone bright as day)

Saved the ship, that might have sunk easily;

And held her on a true course o’er the sea;

To Syria where in Latakia’s bay

They found themselves, nigh that great city,

Close to the shore, from which, not far away,

They could view two castles, tall and mighty.

The captain turned quite pale, in his dismay,

For he knew where they were, instantly,

And sought not to moor within the harbour,

Yet could not flee, nor ride there at anchor,

Not rigged to do either of the latter,

Having lost a mast and spars out at sea;

Where many a beam and plank the waves did shatter,

Such the pounding they received, endlessly;

And yet the ugly truth of the matter

Was that to land meant death, or slavery.

For all must die, or be slaves for ever,

That found themselves there, by chance or error.

Canto XIX: 56-59: The captain explains his reluctance to disembark

To linger there, unsure, was full of danger,

Hostile troops might issue from the city,

And row, armed, to climb aboard a stranger

Not fit to sail, or meet an enemy.

While in such doubt the man did hover

Astolfo questioned his uncertainty,

Seeking to understand why the master

Had chosen not to dock in the harbour.

The captain told him that upon that shore

A murderous band of women had their lair,

Who, in accordance with their ancient law,

Enslaved or slew all warriors that came there;

And from that fate but one escape was sure,

To conquer their ten champions, then repair

To a bed with ten maidens that same night,

And with those maidens seek carnal delight.

And if a man the first task could complete,

But left the second challenge part-undone,

He was slain; and all with him, in defeat,

Set to guard the herds, or toil neath the sun.

While if both of those harsh tests he could meet,

Then the freedom of his company was won,

Though not his own; he was obliged to wed

Ten women chosen there to share his bed.

Astolfo could not hear of that strange rite,

Without smiling at the thought of that same.

Sansonetto and Marfisa joined our knight,

And Aquilante and Grifone came

And listened, as he told them of their plight,

While the captain explained the sorry game;

‘I’d far rather drown,’ he cried, ‘in the sea,

Than bow beneath the yoke of slavery.’

Canto XIX: 60-64: They are towed to the shore

The sailors were of the same opinion,

As were the other passengers aboard,

But not Marfisa nor a single one

Of her companions, who such fear deplored,

Saying they’d rather meet, beneath the sun,

A hundred thousand swords than afford

The sea another chance to slay them all;

Not this nor other fight could them apall.

The warriors were keen to reach the shore,

And boldest of all was the English knight,

Whose magic horn, deployed as before,

He knew would clear every place in sight.

The other travellers yet remained unsure,

Seeking neither servitude nor a fight.

But the strongest, as ever, won the day,

And the captain was, thus, forced to give way.

When first the harbour had come into view,

On their approach to that cruel city,

A vessel, with full complement of crew,

Had left the shore and then, steered expertly,

Sought them, as their plight they did review;

While, on reaching their ship, its company

Lashed her lofty prow to their low stern,

And then, towards the port, their way did earn;

For they entered the harbour under sail,

Yet more by rowing, than before the breeze,

Since a strong offshore wind did now prevail,

And prevented them manoeuvring with ease.

Meanwhile the five warriors donned their mail,

And, after that, their faithful swords did seize,

And with hope and comfort sought to reassure

The crew and passengers, whose dread they saw.

The city’s harbour, four miles long or so,

Was, in shape, a half-moon of curving shore,

Full six hundred yards deep, each horn also

Ended in a stony fortress; safe therefore,

From a sudden assault by sea-borne foe,

Unless, perchance, from the south they bore.

Like some vast theatre the city met the eye,

While, all around it, tall hills rose on high.

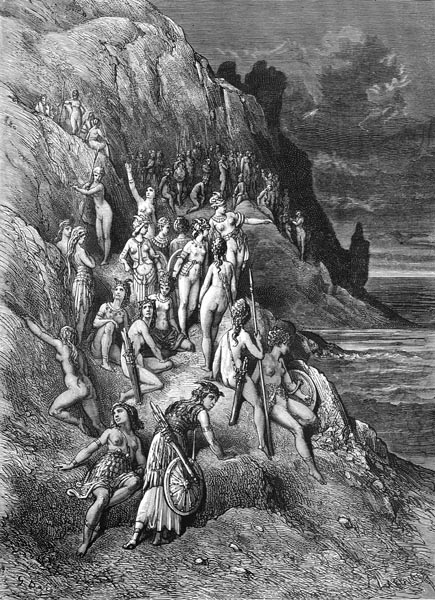

Canto XIX: 65-68: An old woman confirms the terms of entry to the city

No sooner had their vessel reached the land,

(The news had swiftly sped through the place)

Than some six thousand women, bow in hand,

Came there, in warlike dress, with savage face,

And to thwart all escape from that fierce band,

Great chains were stretched, over a wide space

Of the harbour’s waters, so they could close

That port to any vessel, if they chose.

A woman as old as Hector’s mother,

Or the Sibyl at Cumae, now appeared,

Calling on the captain to address her,

And asked him whether slavery they feared

The most, or dying, and, if the latter,

Then to bear the yoke they’d volunteered.

According to the custom of the city,

Their present choice was death or slavery.

‘Tis true’, she said, ‘that if someone of might

Is found among you, full of courage too,

That ten men of ours will engage in fight,

And slay them all here, without more ado,

And then lie with ten women, in a night,

And play the very part that husbands do,

He shall be our king, our lives command,

And you may then depart for your own land;

Though tis up to you if you wish to stay,

All or some, with this single proviso,

That he who would remain here, alway,

Must wed ten women, willingly or no,

While if your champion should fail to slay

Those ten men who against but one shall go,

Or, for the second task, lacks strength and breath,

Then your fate is servitude, his is death.’

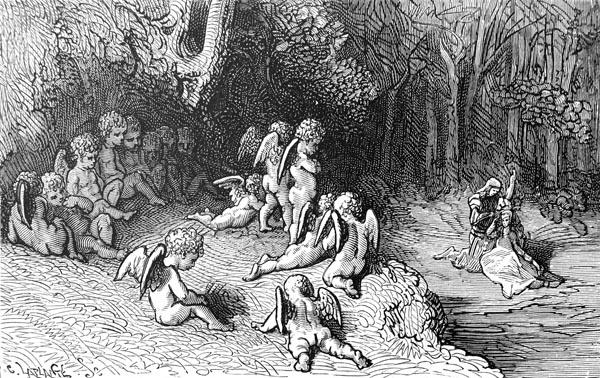

Canto XIX: 69-75: Marfisa acts as their champion

Where that old crone thought to find fear and dread

In the warriors before her, valour

She was forced to recognise there, instead,

For trust they placed in their swords and armour.

Nor did Marfisa quail, to battle wed,

Though the second task might prove beyond her.

Despite being ill-equipped by nature,

With the sword she was as skilled as ever.

To the captain they entrusted their reply,

First attained by mutual discussion,

That since they lacked the power to defy

This custom, they would accept the mission.

The gangplank they lowered, by and by,

Having brought the ship to a near position,

So that the knights, in their shining armour,

Might disembark, with each restless charger.

Then through the city’s midst they progressed,

And saw the haughty maidens riding there,

In every street, while equally impressed,

By those who were arming in the square.

The men were not allowed, not e’en the best,

To bear arms, except the ten in this affair,

No man there wore a sword or spur, no knight,

But those who would perform the martial rite.

Of the rest some were forced to weave or spin,

In female garments, descending to their feet,

Rendering them effeminate; while, within

Such gowns, no flight could be swift or fleet.

Others there were chained, for some past sin,

Made to plough, guard the herds, toil in the heat.

And few there were, barely a hundred men

For every thousand women; one in ten.

The knights decided to draw lots to find

Who, in their common cause, should up and fight,

And dispatch the ten enemies assigned,

Ere contesting the other field that night,

Each excluding Marfisa, in their mind,

As incapable of answering their plight,

Ill-suited as she was, they sought to claim,

As regards the needs of the latter game.

But she desired to draw lots with the rest,

And, as it chanced, to her the mission fell,

‘I’ll risk my life,’ the maiden did attest,

‘To win your freedom, and my own as well.

And this sword, of all companions, is best,

That to sudden death all foes doth impel.

It undoes all that’s tangled, on the spot,

As Alexander solved the Gordian knot.

I would have no traveller complain

Of this place, while the world lasts,’ said she,

And none to thwart her of the task proved fain,

Since, perchance, to fight there was her destiny.

And all to lose there, or, perchance, to gain,

They left to her, their hope of liberty.

Then, clad in all her armour plate and mail,

She took the field those male foes to assail.

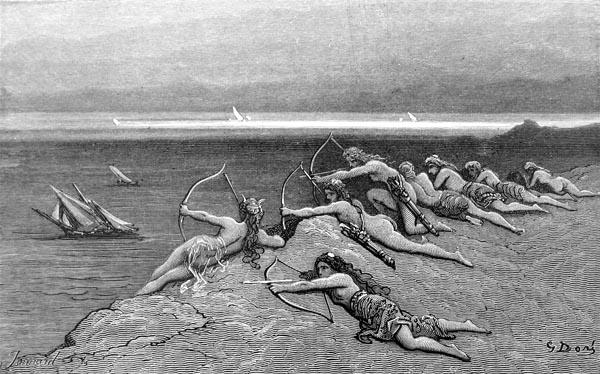

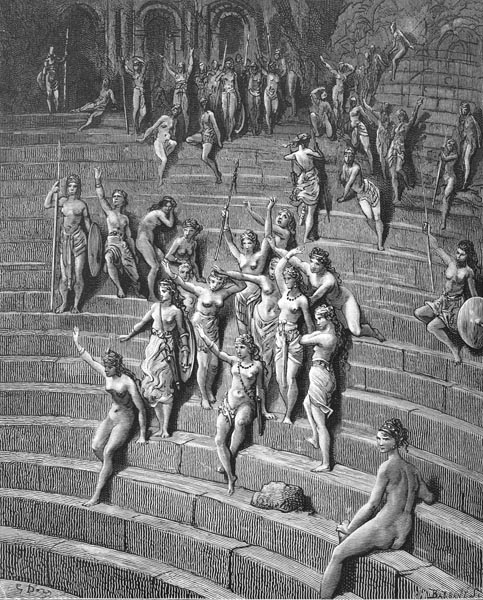

Canto XIX: 76-87: And soon deals with nine of the warriors

There was a place, high above the city,

With tiers of seats, that did a square enclose,

Used for jousting, and many a tourney,

Or gladiator fights, and wild-beast shows.

And four gates of bronze prevented entry.

Through these went the crowd, and sat in rows,

Armed women, en masse, from rim to centre;

And then Marfisa was allowed to enter.

The warrior-maid rode a piebald charger,

With spots and patches all about its hide,

With a slender head, but spirited manner,

Good features, proud air, and splendid stride.

For, out of a thousand mounts, Marfisa

Was with this, by Norandino, supplied;

The bravest, biggest, rarest, of his stable

And fine too the trappings, and the saddle.

She entered, through the south gate, at midday,

And had not long to wait before the sound

Of trumpets reached her ears, and the loud bray

Of horns, that echoed, high and clear, around.

She watched her ten opponents make their way

From the north gate, o’er the open ground,

Of whom their leader looked to her the best,

Seeming of greater worth than all the rest.

He rode a warhorse; but for its forehead,

And one hind foot, twas blacker than a crow;

The brow and foot were snowy white instead.

The rider’s clothes were mostly black also,

As if to say that, like the darkness spread

O’er evening sky that steals the light below,

Likewise, some sadness, darkening his face,

Obscured his happier nature, in that place.

The signal for the joust rang loud and clear;

Nine warriors each their lance did lower.

Yet the horseman in black, it would appear,

Disdained to take advantage of their number;

It seemed his honour was to him most dear,

And that to flout the custom were better

Than fail of chivalry, so paused to view

What nine against a single lance might do.

The warrior-maid’s steed, moving freely,

Bore her swiftly to the fierce encounter,

The lance she carried so large and heavy

Four men could scarcely lift it; earlier,

She’d sought out that same lance, eagerly,

When they’d disembarked, and no other.

A thousand faces paled, so fierce her look;

At her charge, a thousand hearts quaked and shook.

She struck the first of the nine in the breast,

As though he bore no armour to the field,

Piercing the breastplate, then the mailed chest,

But first the solid, well-constructed shield,

So fierce was the blow, and so well-addressed,

A yard beyond the lance-tip was revealed.

A shake of that lance, left his corpse behind,

As, at full speed, the next she sought to find.

Likewise, her lance impaled the second knight,

And struck the third so terrible a blow

That both, with shattered spines, fell outright,

And underneath her charger’s hooves did go,

For her great lance was of such weight and might,

While close on each other’s heels came the foe.

I have seen a bombard in like manner

Cut through a squadron; thus, did Marfisa.

Nor did their lances trouble her at all,

Broken on her armour; at every blow,

She was as little moved as is a wall,

When the players, chasing to and fro,

Strike it, by chance, with the heavy ball.

Hard was her armour, that no mark did show,

Forged in the fires of Hell, deep below,

And in Avernus’ waters tempered so.

At the end of her run, she checked her steed,

Waited a moment, and then charged once more

At those remaining, toppling them, at speed,

And dyeing her sword to the hilt with gore;

Shorn of their head, or arms, she saw them bleed.

Whirling her blade about her, as before.

She sliced one at the waist, left to straddle,

With lower half alone, the bloodied saddle.

She cleft him, I say, in such a manner,

There, where the belly and the haunches meet,

That she left, mounted, but half a figure,

Like those oft placed at holy statues’ feet,

Mostly made of wax, sometimes of silver,

With which the folk, that mercy did entreat,

In deepest gratitude discharge their vow,

As richly as their rank and means allow.

Then she followed after one who fled,

And caught him, near the centre of the square,

And, from his neck, she clean removed the head,

Such that no surgeon could the flesh repair.

In sum, successively, she left them dead,

Or dying, and never a one did spare,

Sure, in the end, that not a single knight

Would rise again, and challenge her to fight.

Canto XIX: 88-91: The tenth, their leader, offers her a respite

Meanwhile the sombre knight, who led the nine,

Had held his self-same place, within the square,

Since for so many men to, thus, align

Against but one, to him, seemed scarcely fair.

Now that he’d seen one knight alone consign

Them all to death; a deed, beyond compare,

To show that it was chivalry, not fear,

Had caused him to refrain, he now drew near.

He gestured with his hand, to indicate

That he would say a word, ere they went further,

And, not thinking that beneath the weight

Of heavy plate and mail a maid did linger,

Thus, declared: ‘Sir knight, I surmise that great

Must be your weariness, post such slaughter,

And if I were to weary you more deeply

Than you are now, that were no chivalry.

That you may rest until the morning light

And then renew the battle, I concede,

Twould be no honour to me, now, to fight

With one who must be tired and spent, indeed.’

‘To labour in the joust, the effort slight,

Is nothing new to me, no rest I need,’

Replied Marfisa, ‘and I hope to prove

That, to your cost, ere we from here remove.

I thank you, sir, for your courteous offer,

Though not in need of rest, as you imply.

As for some time yet the day will linger,

Twould be a shame to let the chance slip by.’

‘Oh, could I but as readily, in other

Matters the heart might wish, so satisfy,

As I now satisfy your wish,’ said he,

‘And yet you may lose the light, too swiftly.’

Canto XIX: 92-97: She refuses, and the pair engage

So, he spoke, and had two fresh lances brought,

(Rather two great spars) then to Marfisa

He had the finest carried and, as twere naught,

Wielded, himself, the weight of the other.

Lances lowered, they waited, as in sport,

For the trumpet call, then met together.

Behold! The land, and sea, and air echoed,

As it sounded, and their advance followed.

None dared breathe or blink; the audience

Was spellbound as they watched the two engage,

Wondering which one would issue thence,

And which lie dead upon that bloodied stage.

Marfisa, who would pierce the knight’s defence

Such that he could not arise, her aim did gauge,

Levelling her lance, while the other sought

No less to slay his foe; and, thus, they fought.

The lances, though of solid seasoned oak,

Seemed more like willow, to the watching eye,

As, up to the grip, they splintered and broke,

While against each other their mounts did fly,

Such that sliced at the knee, at a stroke,

As by a scythe, both steeds were felled thereby,

But, slipping from their saddles easily,

Both riders rose to their feet, equally.

Marfisa had overthrown a thousand

With a first swift lance thrust, and had never

Herself been brought to earth, you understand,

And yet was toppled, in this fierce encounter.

She was not only shocked as she did land,

But nigh on beside herself with anger

At her strange fall, so too the other knight,

Unused to being downed in any fight.

And yet, their steeds had scarcely touched the ground,

Ere they were on their feet, and fought again,

Cut, then thrust, retreated, made their ground,

Deployed their shields, or came on amain;

The air stirred, by blade and armour’s sound,

Whether they struck home, or struck in vain.

Breastplate, helm, or shield rang out, below

Harsher than anvil neath the hammer’s blow.

If the maiden’s strokes fell full heavily,

Those of the other were scarcely light,

And, in full measure, both paid equally,

For all they dealt returned upon each knight.

Those who would bold, courageous, spirits see

Need look no further than that daring fight,

To witness pride, matched by dexterity;

For no finer show of skill could there be.

Canto XIX: 98-108: They agree to postpone the fight

The women, seated, absorbed in viewing

That martial spectacle, fierce blow on blow,

Seeing no sign of weariness ensuing,

Nor any grievous wound there on show,

Praised them as the worthiest two going,

Where’er the sea’s wide arms extended; though,

They said, they had surely died ere long,

Had they not been the strongest of the strong.

To herself, the maid said: ‘Tis well indeed,

That he chose to wait, and not fight, before,

For I risked not merely losing my steed

But my life, if, at first, he’d made one more,

Since I do little here but stand and bleed,

Beneath this hail of blows none can ignore.’

Marfisa meanwhile plied her restless blade,

And continued her defence, quite unafraid.

‘Tis fortunate for me,’ the other knight

Reflected, ‘that my foe did not accept

My suggestion of resting from the fight,

For, though I am myself scarcely inept,

I struggle here; yet what if, at first light,

Renewed in strength and vigour, having slept,

This warrior fought? Fortune favours me,

In that naught came of all my chivalry.’

The battle lasted till the close of day,

Nor was either seen as having won;

Nor as the sun sank, beyond the bay,

Could either clearly view the other one.

So, the courteous knight, now had his say,

In noting that the day was almost done:

‘What should we do, since Fortune equally

Smiles on both, now we can barely see?

It seems to me twere better you prolong

Your life, at least until tomorrow morn;

I may not adjourn further, twould be wrong.

I can but add the one short night, till dawn,

Yet that tis but a night, which is not long,

Blame me not; indeed, the blame should be borne

By these women, and their savage custom,

For the female sex rules this kingdom.

That I grieve for you, and your company,

He knows, from whom nothing is concealed.

You, and your companions, may rest with me,

All other places will but danger yield.

For gainst you now, leagued in conspiracy,

Are those whose spouses fell there, in the field,

For every one you slew of those nine men,

Had, of this band of women, married ten;

And for the harm that they’ve received from you,

Ninety women their revenge would take;

Should you my hospitality eschew,

A bold attack, this night, they’re sure to make.’

Marfisa answered: ‘I, and my comrades too,

Accept your offer for, here’s no mistake,

No less true are your kindness and honour

Than your daring and your martial valour.

But, if you rue the thought of my demise,

You yet may live to rue the contrary.

I’ve given you no cause for grief, likewise,

For I am no less fierce an adversary.

Whether you’d pursue this, or devise

Another plan; by day, to joust with me.

But give the signal, and I’ll be ready,

Howe’er, and whene’er, you seek it of me.’

Thus, the battle was deferred till dawn,

When the sun appears o’er the Ganges’ flow.

And so, the question rested, till the morn,

Of whether either was the stronger foe;

Then he went to her company, to warn

Them of their plight, begging them also,

To seek his roof now and in comfort stay,

As honoured guests, until the break of day.

They accepted his plea, without suspicion,

And, by the light of torches, they ascended

Till his princely palace they came upon,

With many a chamber, and well-defended.

Raising their visors, gazing here and yon,

The two in amazement stood, suspended,

For Marfisa found that the knight once seen,

Appeared to be no older than eighteen.

And while the warrior-maid wondered, there,

How one so young could show such martial skill,

The other wondered, gazing at her hair,

How a maiden had shown such strength of will;

Then they asked each other’s name, that pair.

For his, indeed, I’ll leave you longing still;

How the young warrior was named, I fear,

You must wait on my next canto, to hear.

The End of Canto XIX of ‘Orlando Furioso’