Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto X: Rescued and Rescuer

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto X: 1-9: Ariosto on male fickleness

- Canto X: 10-14: Bireno’s affections stray elsewhere

- Canto X: 15-18: He and Olimpia reach a deserted island

- Canto X: 19-26: Bireno abandons Olimpia on the isle

- Canto X: 27-34: Olimpia’s lament

- Canto X: 35-39: We return to Ruggiero who meets three of Alcina’s ladies

- Canto X: 40-43: Ruggiero, spurning their pleas, finds himself pursued

- Canto X: 44-47: He boards the ferry to Logistilla’s realm

- Canto X: 48-51: Ruggiero employs the magic shield

- Canto X: 52-56: Alcina is defeated

- Canto X: 57-63: Logistilla’s castle

- Canto X: 64-68: Ruggiero leaves Logistilla’s isle

- Canto X: 69-73: His flight takes him to England

- Canto X: 74-76: He arrives as Rinaldo is reviewing the troops

- Canto X: 77-89: The various companies described

- Canto X: 90-95: Ruggiero flies onward and sees Angelica bound to the rock

- Canto X: 96-99: He is overcome by love and pity

- Canto X: 100-106: He fights with the sea-monster

- Canto X: 107-115: He employs the ring and frees Angelica

Canto X: 1-9: Ariosto on male fickleness

Of all the lovers, all those on this earth

Ever faithful, of all the constant hearts,

Of all those blessed, in sorrow and in mirth,

Who in love have played such famous parts,

To Olimpia I’d give the prize, her worth

Being such that, if not first in love’s arts,

None of the new or ancient story-tellers,

Have told us of a greater love than hers.

And so many and such clear signs she gave

That she had made Bireno sure twas so;

No woman’s faithfulness this side the grave

Were clearer, if her heart were there on show.

And if ever a spirit, loyal, loving, brave,

Deserved such love reciprocated, know

That Olimpia had deserved, no less,

Bireno’s love and constant faithfulness,

Such that he never should abandon her

For any other, were the woman she

Who made both Europe and Asia suffer,

However great her title to beauty.

No, rather should he forego the splendour

Of the noonday sun, the use of every

Sense, his life, his honour, or whatever

Has been claimed, or thought, to be dearer.

Yet whether he loved her as much as she

Loved her dear Bireno, and proved as true

To her as she to him, whether he, duly,

Set his sail to maintain her barque in view,

Or proved ungrateful for her loyalty,

Treating such love and faith as nothing new,

I shall tell; and your lips I shall compress,

In wonder, and your eyebrows raise no less.

And when you’ve seen the depths of cruelty

That proved the reward for all her goodness,

Ladies, take note, for none of you should be

Fooled so easily by your lover’s glibness.

Lovers to win what they desire, you see,

Forgetting God knows all, will oft express

Their so-called love in promises, and swear

Such things as vanish on the morning air.

All their vain oaths and promises are lost,

Scattered, and dissipated by the breeze,

Once their great thirst is sated, to your cost,

Once those hot lips, so full of ardour, freeze.

Let this example leave you less star-crossed

Than doubting of their endless tears and pleas.

Less costly, ladies, is the wit and sense

That’s gained from other folks’ experience.

Beware of those in the first flower of youth,

With their smooth cheeks, that glow with white and red,

For like a fire in straw, swift born, in truth

Their every fancy is as swiftly fled;

Like to a hunter, who e’er plays the sleuth

And seeks the hare, deep in its grassy bed

Or on some hill or shore, he will not prize

What he has won, but only that, which flies.

Such are those youngsters, who will respect you

And love you, if you but treat them harshly,

As well as those who serve you, and prove true,

That offer you their homage, faithfully.

Yet, as slave not mistress, bid love adieu,

If you once let them claim the victory,

For from your own their eyes will quickly stray,

And their false gaze o’er other women play.

By this I do not mean (such would be wrong)

That love should be despised, for then you’d be

Like some uncultivated vine, among

The rest, that needs a prop, or two or three;

Tis only downy youth amid the throng,

Eloquent but inconstant, you should flee,

And choose the riper, not the bitter fruit;

Yet not the overripe: I doubt twill suit.

Canto X: 10-14: Bireno’s affections stray elsewhere

A daughter they’d discovered, as I said,

Of the Frisian king, a captive there,

Who to Bireno’s brother might be wed,

Such was the word, and yet delicate fare

Bireno thought such food, who, instead,

Deemed it would be but a foolish affair,

To give that dainty morsel to another,

Of courtesy, though it were his brother.

The little maiden was not yet fourteen,

Yet beautiful, and fresh, as is the rose,

That springing from the dew-wet bud is seen,

And with the springtime sun sweetly grows,

Not only did he love the maid, I mean,

But dry tinder with less ardour glows

Or ripened corn if some malicious hand

Sets it alight, hurling a burning brand,

Than did Bireno’s passion, instantly,

(Such that he burned to the very marrow)

When he saw her grieving so deeply,

For the king, her gaze softened by sorrow;

And as cold water that is added swiftly

To water near to boiling, heat doth borrow,

And halts the seething, thus was extinguished

That love for Olimpia we’d distinguished.

Not merely sated with his bride, Bireno,

Loathed her so he could not bear to see her.

He longed so deeply for the other, though,

That he could scarcely wait to be her lover,

Yet, till the day appointed, sought to show

Such true feelings for Olimpia, ever,

That indeed he seemed to love her more,

And what she liked, he too feigned to adore.

And if he sought to embrace the other,

None there accused him of an ill intent,

(Though he embraced her more than was proper)

But thought it from pity, and kindly meant,

While to comfort one whom fate, moreover,

Has brought low, one fair and innocent,

Accrues scant blame, but rather garners praise;

Much less a harmless maid with pretty ways.

Canto X: 15-18: He and Olimpia reach a deserted island

Oh, Lord on high, how our human judgement

Is oft obscured, as if by some dark cloud!

Bireno’s deeds, profane in their intent,

And impious, were by other folk allowed,

As kind and pure; The seamen now were bent

To their oars, and now the brave vessel ploughed

The waves, bearing Duke Bireno, gladly,

To Zealand, with his precious company.

The coast of Holland was now far behind,

All lost to sight was that familiar shore,

(Avoiding Frisia, their course inclined

Towards fair Scotland on the port side more)

When, suddenly, opposing winds combined

To drive them to and fro, amidst their roar,

Till, on the third day, they were but a mile,

From an uncultivated stony isle.

They made anchor when the storm winds died;

Olimpia landed and, with true delight,

Dined contentedly, Bireno at her side,

Suspecting naught but kindness from her knight.

Then they entered their tent, above the tide,

Where they found a bed prepared for the night.

The rest of their court would sleep aboard,

Seeking sleep where the vessel now was moored.

Her travails while at sea, and then her fear,

Had weighed upon her, and denied repose;

Yet now she felt secure; the shore was drear,

But, here, at least no woodland cries arose;

While ne’er a care had she that one so near

Her side, her love, could ere a danger pose.

And, thus, Olimpia’s slumber was so deep

No bear or dormouse wins a sounder sleep.

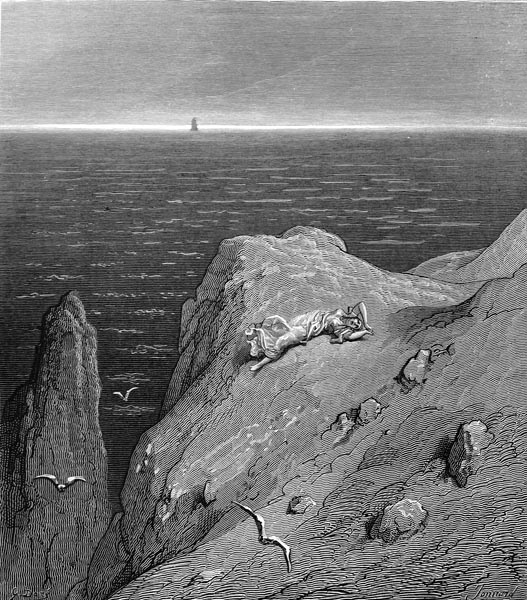

Canto X: 19-26: Bireno abandons Olimpia on the isle

Once she slumbered, that traitorous lover,

Prepared to execute his deception,

Slipped from the bed, bare of any other

Clothes than those he wore, fled their pavilion,

And, as if on wings, his clothes together

In a bundle, flew in the direction

Of his good ship, and bade the crew unmoor;

Then, silently, the vessel left the shore.

Olimpia slept peacefully the while,

Until Dawn scattered the cold briny dew

From her golden chariot, o’er the isle,

And the ancient mournful cry rose anew

From the halcyon, the hearer to beguile.

Twas only then sleep from her mind withdrew.

When, stretching out her arm to Bireno,

Her hand grasped but emptiness, to her woe.

Finding him not, she now drew back her arm

Tried once more, and yet still tried in vain,

Then sought about the bed, in some alarm,

Although from that naught further did she gain.

Fear banished sleep, and with many a qualm,

She rose now from the bed, and viewed all plain,

Then from that couch, and the pavilion

Was driven forth by tremulous emotion.

She ran towards the sea, no vessel saw,

Fearful, and then more certain, of her fate,

She beat her breast, and at her hair she tore,

And looked about (while darkness did abate)

To seek some sign of life along the shore,

Yet all that shore was bare, an empty slate.

She called Bireno’s name, soft, then loudly,

As hills and caves echoed their sympathy.

At the land’s extremity a cliff stood tall,

Which the sea, by beating on it, fiercely,

Had hollowed to an arch; the waves did fall

And break beneath the rock, tumultuously.

Olimpia now scaled that stony wall,

(As if possessed) and gazed upon the sea,

And in the distance saw the swollen sail

Of her cruel lord diminish, and grow pale,

Until its form was scarcely to be found,

For the air between was misted as yet,

And then she fell, shuddering, to the ground,

As white and cold as snow, by tears beset.

Again, she rose, and then a cry did sound

Towards that ship, upon its course now set,

Louder and louder cries her voice did claim,

Mourning her love, still calling out his name.

And when her voice failed, turned to weeping,

Wringing her hands together, in her pain,

‘Where with such speed are you now fleeing?

Swifter your ship, without me, such is plain,

Cruel one, let it bear my body, seeing,

My heart’s weight it doth readily sustain.’

And waving a garment clasped in her hand

Called on the vessel to return to land.

But the wind that bore her treacherous lover

O’er the deep sea, filling his swollen sail,

Scattered her every cry, lament, and prayer,

Upon the waves; all proved to no avail.

Three times then she sought to smother

Her woe in the depths, yet her heart did fail,

So, from the sea below, she raised her sight,

And returned to where she’d passed the night.

Canto X: 27-34: Olimpia’s lament

Throwing herself upon the bed, she lay

Face down, wetting it with many a tear,

‘Two bodies you received, but yesterday,

Why at dawn did two likewise not appear?

O false Bireno, cursed be, I say,

The hour that saw my birth, that led me here!

What can I do, alone, who shall aid me?

Alas, betrayed, what could yet console me?

No sign of life is here, there’s naught around

To show aught human dwells upon this isle;

No kind of vessel, perchance run aground,

That I, yet hoping to escape so vile

A place, might use; I’ll starve, and not be found,

With none to close my eyes, with none to pile

The earth above; save for some wolf, maybe,

To consume my corpse, and so entomb me.

Thus, filled with doubt and fear, e’en now I seem

To sense a bear or lion, midst the trees

Or a tiger’s sharp teeth and claws, I deem,

Or some such creature bent on my decease.

But what cruelty is theirs, more extreme

Than the death granted by your cruelties?

They can, indeed, but slay me once, say I,

And yet a thousand deaths you’d have me die.

Suppose some ship should even now appear,

And her master takes me on board, of pity,

And wolf, bear, lion, the wild beasts I fear,

I escape, and from hunger I win free,

And other forms of death, shall I be clear

Of harm, in Holland, or your tyranny?

Should he bear me thence where I was born,

From whence I was so treacherously, torn?

With a pretence of marriage and friendship

You took me from my own dear country,

Leaving your troops to extend their grip

On my realm, rendering it yours completely.

Shall I turn to Flanders, that did equip

My purpose, though I spent all left to me

In seeking aid, to free you from your prison?

Where shall I go, now my recourse is gone?

Ought I to go to Friedland, where I could,

But on account of you would not, be queen?

Friedland, through which my every good,

My father and my brothers, death did glean?

Twas all for you, you wretch, and yet I would

Not seek to reproach you, for that, I mean.

No less than I, the whole tale you well know.

Behold then my reward for acting so!

Oh, let me not be taken now in flight,

By those who visit, and be made a slave!

Rather let tiger, bear, or wolf, outright

Destroy me, or some fiercer creature rave,

Tear me with its claws, and rend and bite

My helpless flesh, and drag me to its cave.’

With this, she at her golden tresses tore,

Rending them strand by strand, much as before,

Then to the shore’s extremity did run,

Tossing her head, hair blowing in the breeze,

As if possessed, and not it seemed by one

Dark demon, but by ten of all degrees.

(Like Hecuba, on viewing her dead son,

Young Polydore, maddened by his decease.)

Then, fixed upon a rock, gazed at the sea;

No less than true stone, stone she seemed to be.

Canto X: 35-39: We return to Ruggiero who meets three of Alcina’s ladies

But leave her now to grieve till I return.

Of Ruggiero I would speak again,

That in the midday sun did grieve, in turn,

As, wearily, he rode the sandy plain.

Bright rays now struck the hills, and fierce did burn;

Boiling hot, the stones did that heat retain,

And little more was needed, such their might,

To render armour fiery, in that light.

Now, his great thirst and the heavy going,

As he toiled through the deep sand, silently,

Along the shore, its bright surface glowing,

Were both proving unpleasant company,

When, in the shadow of a tower reclining,

(An ancient turret rising midst the sea)

He found three ladies of Alcina’s court,

As their dress and their gestures did report.

On carpets made in Alexandria,

They savoured the coolness with delight;

Round them wines, of every kind and colour,

Were placed, and delicacies sweet and light.

Near the shore, and flirting with the tremor

Of the waves, lay a vessel, small and slight,

That waited for its sails to fill once more;

For not the slightest breeze caressed the shore.

The three (observing Ruggiero toiling,

Through the heavy sand, upon his way,

Seeing his parched lips, his armour boiling

Hot, his sweating face) begged him to stay,

Saying that if he was not unwilling

To turn from his path, in the heat of day,

He might share the coolness of their shade,

And rest his weary limbs, for so they bade.

One of the ladies now approached the knight,

To hold his stirrup, while another bore

Foaming wine in a crystal cup, which quite

Aroused the thirst that he’d subdued before;

Yet against their pleas he chose to fight,

Knowing each delay was one chance more

For Alcina to appear, who, to his mind,

Was either at his heels, or close behind.

Canto X: 40-43: Ruggiero, spurning their pleas, finds himself pursued

Fine saltpetre and pure sulphur blaze not

More instantly, when touched by a flame;

The sea, struck by a whirlwind, seethes not

More furiously, troubled by that same,

Than (on finding Ruggiero waited not,

But plodded o’er the sand much as he came,

Scorning maids that thought themselves most fair)

The third, who burned with rage and fury there.

‘You are neither courteous nor a knight’

(She called to him, as loudly as she could)

‘You stole that armour, and that horse, the right

To which cannot be yours, nor ever could,

And you, if truth be mine, must now requite

That robbery with death, and so you should.

I’ll see you hung, and drawn and quartered too,

Vile thief, a fitting end for such as you.’

All the other cries, more furious yet,

With which the lady cursed the warrior,

Ruggiero with stony silence met,

Thinking to reply brought little honour.

With her sisters to their vessel, in a pet,

She departed and, once upon the water,

Took up the oars, and then pursued the knight

Along the shore, while keeping him in sight,

Venting many a threat, and accusation,

Blaming him with every word she preached.

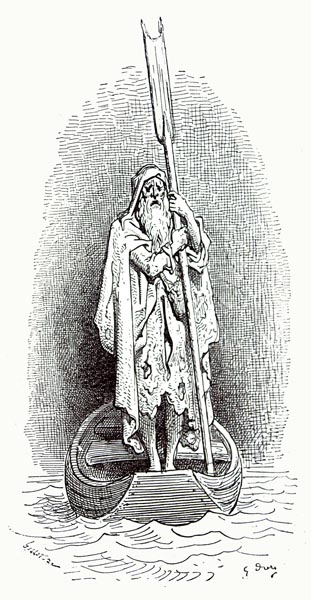

Meanwhile, the knight arrived at a location

Whence Logistilla’s realm might be reached.

And saw an ancient ferryman, on station,

Who, on the shore, was now already beached,

As if forewarned, positioned to await

Our warrior, and bear him o’er the strait.

Canto X: 44-47: He boards the ferry to Logistilla’s realm

The ferryman now welcomed him politely

Set to transport him to a happier shore;

By his look, he seemed discreet and kindly,

As if his face revealed the heart he bore.

Ruggiero, with thanks to God, swiftly

Went aboard and, once seated at the fore,

Passed o’er the calm sea, in conversation

With this wise and experienced boatman.

He praised our knight for fleeing the palace

Of Alcina, in good time, well before

He had drunk of her enchanted chalice;

For she transformed her lovers, by her lore.

And that, to escape her further malice,

He was crossing to Logistilla’s shore,

Where eternal beauty, and endless grace,

Nourished the heart, in that most sacred place.

‘Wonder and reverence are felt,’ he said,

‘In your soul, when you first behold her.

Gaze on her noble presence, and be fed;

Naught but that shall your being treasure.

Fear and hope by other loves are bred,

But love for her differs in such manner

As to desire no more of her than this:

To gaze forever, and in that find bliss.

She’ll lead your intellect to deeper things

Than bathing, eating, music, perfumes, dance;

How, in line with your nobler thoughts, on wings

You may soar like a hawk, your mind enhance;

And how in the glory of blessed beings

A mortal might yet share, and so advance.’

So saying, his pilot approached the shore,

Though distant still; their path not yet secure.

Canto X: 48-51: Ruggiero employs the magic shield

A fleet of vessels flew across the water,

And steered towards the ferry, in a line;

For, thus, came the furious Alcina,

With the host she had gathered, o’er the brine,

Risking her ruin and her realm’s together,

To win the knight; love prompted her design,

Good reason for her to be, thus, aggrieved,

But no less so the insult she’d received.

For such great anger she’d ne’er felt before,

As this ire, gnawing at her heart and mind,

Such that her ship drove on, with sail and oar,

Till all the sea, indeed, foamed white, behind,

And Echo sent the noise from shore to shore,

That every cliff and cave doth ever find.

‘Ruggiero, use the shield, tis needed now,

Else you to death, or utter shame, must bow!’

So cried the ferryman, and waited not,

But grasped the cover, and removed it quite,

And, with it in his grasp, all fear forgot,

He thus revealed its clear and shining light.

Its splendour shone, and forth the bright rays shot,

And so affected their enemies’ sight

That, rendered blind, so fierce the light did burn,

They fell now from the prow, and now the stern.

Then, one who was on watch upon the wall

Who’d observed Alcina’s approaching fleet,

Range the castle’s warning bell; at his call

Swift aid was summoned, to advance and meet

Ruggiero, while their arrows fell on all

That sought to wrong our warrior by deceit.

And such help they granted him in the strife,

That they preserved his freedom, and his life.

Canto X: 52-56: Alcina is defeated

Four ladies now arrived upon the shore,

Sent there, hastily, by Logistilla,

Andronica and Fronesia to the fore,

Valorous the one, and wise the other,

Also (the latter needed even more)

Honest Dicilla, and chaste Sofrosina,

Burning brightest; while from the castle height,

A peerless host emerged to aid the knight.

Beneath the castle, in the calmer water,

A flotilla of mighty vessels lay,

Which, at a signal, from any quarter,

Was fit for martial action, night or day;

And, thus, on land or sea, to the slaughter

They put the enemy, and made them pay.

For they turned Alcina’s realm upside-down,

Which she had stolen with her sister’s crown.

Of how many battles is the outcome

Different than that anticipated!

Not only was Alcina parted from

Her lover, whose capture she’d awaited,

But of the host of ships, so great in sum

They filled the ocean as I have stated,

Out of the flames that destroyed the rest

She escaped with one, though twas the best.

Alcina fled, while all her people drowned,

Were routed and taken, or were burned,

Yet Ruggiero’s loss was most profound,

And brought more pain than her defeat had earned.

Night and day, her tears would wet the ground;

Still, for her handsome warrior, she yearned;

While she now oft regretted, with a sigh,

She could not end it all, and simply die.

For no faery enchantress can do so,

While the sun and stars circle overhead,

Yet if she could, then the third Fate, Clotho

Would surely have severed her life’s thread,

Seeing her sorrow; or she, like Dido,

By cold steel had died or, upon her bed,

Like Cleopatra to endless sleep allied;

But creatures such as her have never died.

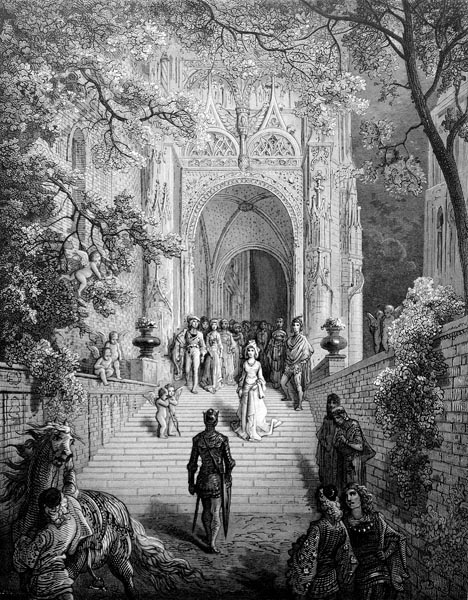

Canto X: 57-63: Logistilla’s castle

Now, let us turn to brave Ruggiero,

A knight worthy of eternal glory,

And leave Alcina to her pain and woe;

For he’d swiftly disembarked the ferry,

And, thanking God that all had ended so,

Had turned his back upon the sea, swiftly,

And being now upon dry land once more,

Ascended to the fort above the shore.

A castle stronger, or more beautiful,

Was never viewed as yet by mortal eye,

The walls were of stones more wonderful

Than diamonds or garnets; scant supply

Of such gems as these, here, or their equal

Do we find; and if aught of those you’d spy,

Then, I believe, you’d need to travel there;

Except in heaven, there are none elsewhere.

What they owned that made them superior

To every other stone, was that, within,

One could see one’s soul, as in a mirror,

One’s virtues, and propensity to sin;

And so no more need heed the flatterer,

Nor yet the hostile crowd, for all their din;

For, one could, by the mere use of one’s eyes,

Know oneself and, by gazing so, grow wise.

Their brilliant glow, that sought to match the sun,

Shed such splendour on all things around,

It yet would seem that, though the day was done,

Without fair Phoebus, light could yet be found.

Not with their light alone did these things stun,

But their cutting had been skilful and profound;

There, form and content vied to such extent,

Tis hard to say which was more excellent.

On arches tall enough to reach the sky,

So as to hold the heavens up to view,

Stood gardens, fair, so lovely to the eye,

None here perchance e’er so sweetly grew.

Odoriferous shrubs one might pass by

(Amidst the battlements) of verdant hue,

Adorned, the summer and the winter long,

With blossom, though ripe fruit hung there among.

Such noble trees it seems were never grown

Except within those gardens, nor such roses;

Such violets, and lilies, ne’er were known,

Such amaranth and jasmine, one supposes;

For here all such flowers are swiftly blown,

They live and die; here, the eve discloses

Bowed heads, on widowed stalks, to the eye;

All’s subject to the ever-changing sky.

Yet there, it seemed, was everlasting spring,

Everlasting beauty, eternal flowers;

Nor did kind Nature temper everything,

Nor the influence of celestial powers,

But Logistilla there her care did bring,

And so preserved, beyond the passing hours,

(A thing that seems impossible elsewhere)

Her endless springtime, that showed ever fair.

Canto X: 64-68: Ruggiero leaves Logistilla’s isle

This visit from so noble a fair knight

Was greatly pleasing to Logistilla,

And she commanded that he should, of right,

Be treated courteously and with honour.

Astolfo had dwelt there for many a night,

Whom Ruggiero greeted with pleasure;

And soon all those past lovers won there,

Whom Melissa had restored elsewhere.

When he had rested for a day or two,

Ruggiero sought out the faery queen,

With him Astolfo; he too had in view

A swift return; Melissa here was seen

To speak for them, and aid the pair anew,

Yet in humble supplication, I mean,

Asking for help and favour, in their name,

That they might now return from whence they came.

‘I shall think on it’, the faery replied,

‘And in two days that same shall expedite.’

How to assist each she did then decide,

Brave Ruggiero and the English knight,

That, to fair Aquitaine, the first should ride,

And on the hippogriff resume his flight,

While she would fashion for that winged horse,

A bit and bridle to control its course.

She showed him what to do if he would soar,

And how he might then fall to earth again.

And, likewise, how to circle o’er the shore,

Or fly at speed, or hover o’er the plain.

All skilled horsemen seek to learn, and more,

On the ground, that knowledge he did gain

As regards the air; thus, he was master

Of the winged steed, then and thereafter.

Once he was equipped in every way,

He next took leave of the fair enchantress,

Who was most dear to him and, on a day,

Took to the air and flew, with great success.

Regarding that fair flight I’ve much to say,

Then of Astolfo something to express,

He who must spend a deal of time and pain

To reach the friendly court of Charlemagne.

Canto X: 69-73: His flight takes him to England

Ruggiero left; yet not upon that course

He was obliged to take when, in flight,

The hippogriff had borne him off by force,

O’er the sea, the land beneath lost to sight;

But knowing how to steer the winged horse,

This way or that, as he now pleased, the knight

By a different route did homewards fare,

As the Magi did dodging Herod’s snare.

When carried to the isle, on leaving Spain

He’d reached India in unswerving flight,

A place ever bathed by the eastern main,

And where a faery with her peer did fight.

A view of other lands he would attain

Than Aeolus’ realm of windswept light,

And finish, thus, the orbit he’d begun,

Having circuited the earth, like the sun.

Here Cathay he saw, there Mangiana,

Passing, on his journey, broad Quinsay,

And then Imavo; with Sericana

Left behind, on his right, he made his way

South, from Scythia to Hyrcania,

And reached Sarmatia, where, so they say,

Europe begins, while Asia is no more;

Russia, Prussia, Pomerania he saw.

Now though our knight had every desire

To return, and search for Bradamante,

He yet wished to circle the world entire,

And could not rest till he saw Hungary,

Then swept over Poland, rising higher,

Till he could view the whole of Germany,

And every other less than torrid land,

Descending o’er the nearest English strand.

And yet think not that throughout all this flight

Our warrior was always on the wing;

No, no, he found good lodgings for the night,

Shunned, as best he could, those that were lacking.

Months he spent in journeying, our knight,

To see the world, lands and seas reviewing,

Now, close to London, his travels ended,

As o’er the Thames his strange steed descended.

Canto X: 74-76: He arrives as Rinaldo is reviewing the troops

There, in a meadow, near to the city,

Cavalry and infantry were arrayed,

Who, to the drum and trumpet, marched neatly,

And, in squadrons, their finer points displayed

To Rinaldo, that flower of chivalry,

Who had, if you remember, lately made

The journey, sent there by Charlemagne,

In search of help to mount a fresh campaign.

Ruggiero arrived as this fine show

Was taking place outside the city wall,

And, from a knight nearby, he sought to know

The cause of it (dismounting first of all);

And soon learned, from the courteous fellow,

That England, Scotland, Ireland (you’ll recall)

And all the isles around had raised this host

Whose many banners the parade did boast,

Adding that, when this display was over,

The armies would descend upon the sea,

Where vessels were waiting, in the harbour,

To bear them o’er the water speedily.

The French, besieged, sought this show of valour,

Hoping that fresh troops would see them free.

‘But so’ he said, ‘as to inform you fully,

I’ll tell you more about each company.

Canto X: 77-89: The various companies described

There, you may see our great banner fly,

Leopards and fleur-de-lys upon it found,

Unfurled by our great captain, who is nigh,

And to whose ensign all the rest are bound.

Doyen of all the bravest neath the sky,

Lionel is his name, the which doth sound

In highest counsel and in war rings louder;

The king’s nephew, and Duke of Lancaster.

That, next to the King’s banner, now revealed

By the wind, streaming towards the mount,

And showing, thus, three wings on a green field,

Marks Richard of Warwick, that mighty Count.

The third the Duke of Gloucester’s arms doth yield,

Two stag’s antlers that half the brow surmount.

The Duke of Clarence shows a burning brand,

The Duke of York a tree, where he doth stand.

There on the Duke of Norfolk’s great banner

You’ll see three pieces of a broken lance,

While a lightning-bolt Kent’s duke doth offer.

And Pembroke’s count a griffin doth advance.

On Suffolk’s flag a pair of scales hover,

As two twined snakes on Essex’ banner dance.

And, neath that garland on an azure field,

Northumberland’s great earl is half-concealed.

The Earl of Arundel is he who shows

A barque still foundering amidst the sea.

See the Marquis of Berkely’s there, and those

Are March’s and Richmond’s earls’; of the three:

A cleft mount on the first, in pure white, glows,

The palm the second holds, a tall pine tree,

Amid the waves, the third. Southampton’s crown,

And Dorset’s chariot, mark their renown.

Raymond, Earl of Devon, bears that banner

With a hawk that spreads its wings o’er the nest.

Sable and or, those are the arms of Worcester.

Derby a dog, Oxford a boar, his crest,

Display; Bath’s wealthy prelate, discover

Beneath that crystal cross, amidst the rest.

A broken chair, on silver ground there set,

Speaks of Edmund, the Duke of Somerset.

Forty-two thousand, that must be the sum

Of knights-at-arms and mounted archers there,

While twice as many here on foot are come,

Give or take a hundred, to this affair.

Behold the flags, sable and azure some,

Argent, and vert, and or, to which repair

Each to their own standard, the infantry,

Led by Edward, Henry, Hamelin, Godfrey.

The first is Edward, Earl of Shrewsbury,

Then comes Henry, Earl of Salisbury,

Next old Hamelin, Baron Bergavenny,

While Duke of Buckingham is this Godfrey.

Those to the east are English Infantry,

Turn to the west now, and the Scots you’ll see.

Thirty thousand led by the monarch’s son,

Zerbino, who hath many a skirmish won.

The lion midst three unicorns you’ll see,

One that clasps a silver sword in its paw,

Tis the Scottish king’s standard, floating free,

There Zerbino camps, his son, he’s far more

Handsome than the other knights there, truly,

Nature made him and broke the mould; tis sure

He exceeds all in virtue, and in grace;

The Duke of Ross his title and his place.

Set on an azure field, that golden bar,

Marks the Earl of Huntley’s great banner,

That other flag proclaims the Earl of Mar,

A leopard in travail displaying ever.

See those birds, multi-coloured and bizarre,

That ensign is Hamilton’s, moreover,

Though he’s neither duke, nor count nor marquis,

He is first in that savage realm of his.

The Earl of Crawford’s has an eagle, there,

Fixing its bold gaze on the blazing sun,

Lurcanio, Earl of Angus, his doth bear

A bull, that’s flanked by hounds; see, two not one.

The Duke of Albany’s those colours share

Of azure and argent. See, the dragon,

All in vert, how it tears at the vulture

The Earl of Buchan shows on his banner.

The mighty Herman, Baron Forbes, displays

A banner striped in sable and argent;

At the Earl of Errol’s, on his right, now gaze,

Which a lamp on a green field doth present.

Look upon the Irish; the sun’s bright rays,

Reveal two squadrons, for Kildare has sent

Its Earl to lead the first, while the second

Is commanded by the Earl of Desmond;

Kildare’s ensign reveals a blazing pine;

Desmond’s a bend gules on an argent field.

Not only England, Scotland, Ireland line

The open plain, their weapons soon to wield

For Charlemagne, but Swedes and Norsemen, fine

Warriors from Iceland, Thule, are revealed:

All lands about, in sum, brave men release,

All those, by nature, enemies to peace.

Sixteen thousand fighting-men, more or less,

Have emerged, as well, from forest and cave,

With hairy face, and legs, and arms, and breast,

Like savage creatures, and as fierce and brave,

All about that argent standard see them press,

As if a floor of spears the ground doth pave.

Such Moray bears, by whom that folk are led,

He, who with Moorish blood would paint it red.’

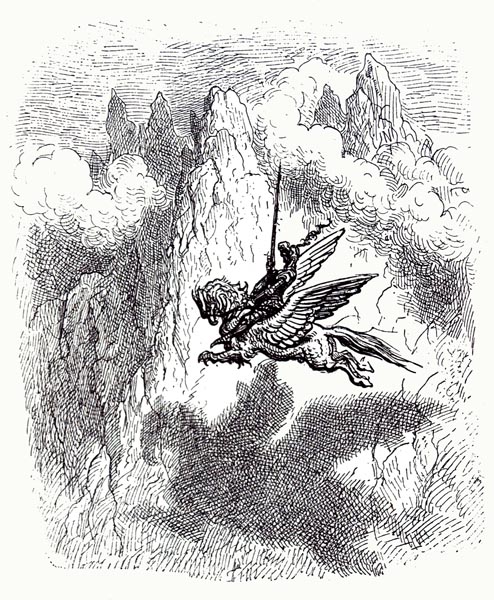

Canto X: 90-95: Ruggiero flies onward and sees Angelica bound to the rock

While Ruggiero thus observed the army

Preparing to bring timely aid to France,

And marvelled at the banners’ heraldry,

And heard the names, towards him did advance

A host of knights; they gathered round to see

The wondrous steed, sole specimen perchance,

Hastening to look, then gazing, stupefied,

Till a circle formed, drawn from every side.

To rouse in them a greater sense of awe,

And add to the sum of his own pleasure,

He shook the reins and set the beast to soar,

Touching his spurs to its sides a measure,

Then, rising heaven-wards a little more,

Set a course through the sky, at his leisure,

Left them gazing, and having viewed that day

The British troops, to Ireland made his way.

Thus, that fabled Hibernia he reached

(Where the old saint had a cell, and within,

It seems, was found the mercy that he preached;

There the penitents were purged of their sin)

And soon had nigh that island over-reached,

Washed by the waves, of Scotland the close kin,

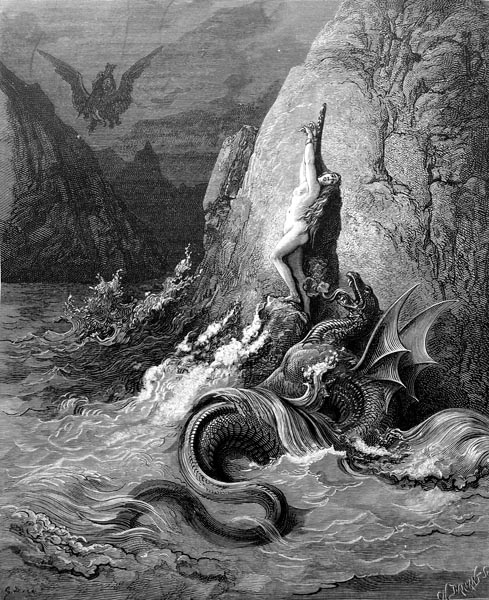

And saw beneath him, fearful and alone,

Angelica, chained to the naked stone.

To the naked stone, in that isle of tears,

For the isle of tears indeed was its name,

A race, proud and cruel, had, through the years,

Dwelt, savage and inhuman, in that same.

They (from a previous canto, it appears)

Roamed armed about the scattered shores, their aim

To bear away the lovely maids they found,

And feed the sea-monster, as they were bound.

She had been chained there that very morning

Thence the immeasurable monster came,

To devour the poor maiden, while still living,

And make a horrendous meal of that same.

Above you were told of her becoming

The prey of those vile robbers who did claim

Her as their prize, as she slept on the shore,

Beside the monk, enchanted through his lore.

That proud, cruel, and inhospitable crew

Had exposed her to the savage creature,

Upon the rock, as naked to the view

As when formed, at first, by Mother Nature;

Nor yet a veil had she to hide her hue,

Of the rose midst the lilies, that ever

Mingled in her lovely limbs, still fair

In December frost, as if June were there.

Canto X: 96-99: He is overcome by love and pity

He would have thought, perchance, he did behold

Some work in marble, or alabaster,

Fixed, it seemed, to the solid rock, of old,

By the skilful hand of some past master,

If it was not for the fresh tear which rolled

Down her cheek, to wet the rose, thereafter,

And lily of her breasts, as if with dew;

And that, in the breeze, her gold tresses blew.

And as his eyes gazed at her lovely eyes,

Fair Bradamante filled his thoughts again,

Pity and love pierced him and, likewise,

From loving tears, he now could scarce refrain.

And mingling then those tears with his sighs

(After checking his winged steed with the rein)

Cried: ‘O lady, of those chains full worthy,

With which Love binds his faithful company,

And undeserving of such cruel pain,

Or aught like to it, say, what perverse hand

Has so cruelly, with its livid stain,

Set, on those ivory members, his foul brand?’

She was obliged to blush, and stir in vain,

Her pale ivory as if with red grain fanned,

On finding, thus, those parts exposed to sight,

That shame conceals within the darkest night.

Her face she would have hidden if she could,

Except her arms were chained to solid stone,

Yet with her tears bedewed it (as she could)

To quench those blushes, or at least disown

Their crimson stain; speechless awhile she stood,

Then in a faint, and nigh-exhausted tone,

Began to speak, yet stopped, almost mid-word,

As some great tumult from the sea was heard.

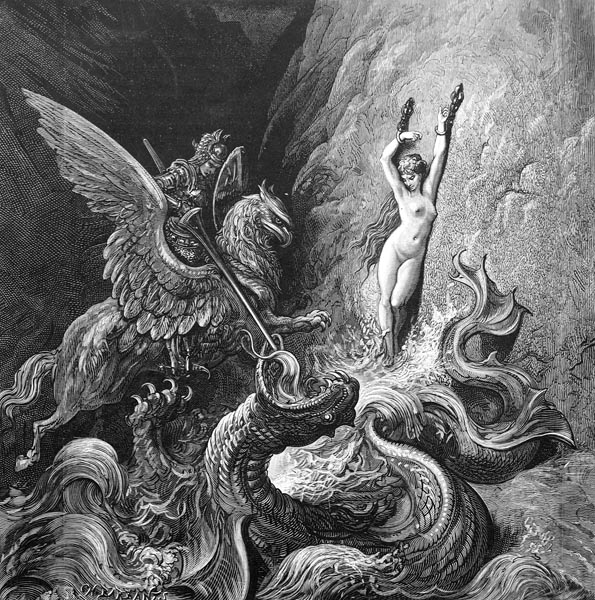

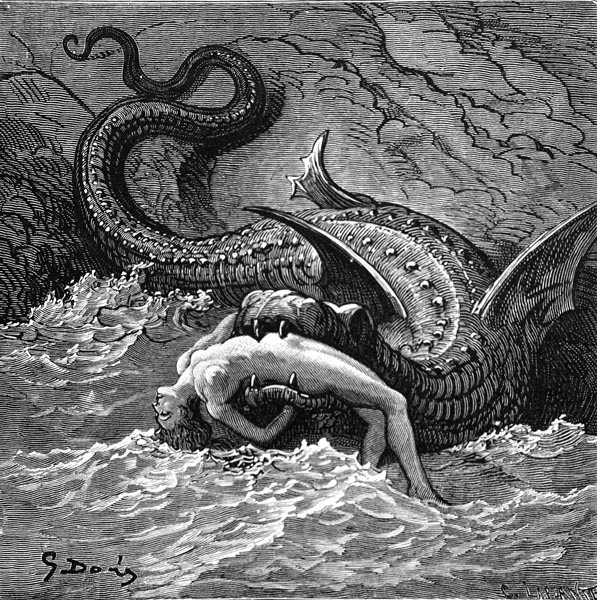

Canto X: 100-106: He fights with the sea-monster

Behold, the enormous monster appeared,

Half-visible, half-hidden by the wave,

As before some northerly gale is reared

The bold longship, that doth the storm-wind brave.

So that great orca, ever loathed and feared,

Arose, and time was short in which to save

The lovely lady, now half-dead with fright

Despite the sudden presence of the knight.

Ruggiero raised his lance overhead,

Then struck the monster, with a downward blow.

All shape it seemed to lack now, and instead,

A writhing mass o’er which the sea did flow,

Revealed no proper form, but for the head,

Which a huge sow’s eyes and jaws did show.

The knight’s blow, on the forehead, it took;

Twas as if at steel or solid rock he’d struck.

Since that first deed had proved of no avail,

The knight returned to perform another;

Thus, when the creature saw dark shadows sail,

Cast by those huge wings, across the water,

It left its prey and followed, without fail,

The phantom form, in its rage to slaughter

This sudden foe, and roiled the depths below.

Ruggiero swooped, and dealt it blow on blow.

As when an eagle spies, from its great height,

A snake that writhes and slithers through the grass,

Or on some bare stone that the sun doth light,

Cleans all its golden scales, a gleaming mass,

The raptor will avoid the poisonous bite,

Nor seek those shining flanks to overpass,

But gripping from behind, on beating wing,

Employs its claws, and thus evades the thing.

So, Ruggiero struck with sword and lance,

Not where the jaws were, filled with those sharp teeth,

But twixt the ears while it sought to advance,

On the spine, or the raised tail underneath.

If the creature turned, by design or chance,

He changed course, rose or fell, with it beneath.

But, as if he beat against a diamond block,

He could no more pierce it than solid rock.

So, the bold fly seeks to torment a dog,

In August’s dust and heat, or either side,

When fields of grass are ripe or must doth clog

The wine-vats and the presses, far and wide.

It swoops downward, where he lies like a log,

Stings his muzzle, and his eyes, in its glide;

At its buzzing, he snaps his jaws together:

Reach the wretch, and tis over for ever.

The monster’s tail so churned the water there,

It sent it soaring far into the sky,

Such that he knew not if he flew in air,

Or if his steed swam, and the waves passed by;

And often wished an end to the affair,

For, if the spray continued so to fly,

He feared it well could drown the hippogriff,

And leave him searching for a float or skiff.

Canto X: 107-115: He employs the ring and frees Angelica

He took counsel with himself, for the better,

To fight the monster with a fresh weapon,

And thought to dazzle it with the splendour

The shield possessed (its cover still was on).

He flew to shore and, in case of error,

With the maid chained to the rock, thereupon

Left the ring, on her little finger set it;

Since it could dim the shield, if he let it:

The ring that Bradamante stole, I mean,

From Brunello, to free Ruggerio,

That saved him from the wicked faerie queen;

Twas borne to the isle by Melissa though,

Melissa who (I said, and you have seen)

For the good of many employed it so,

Then, quietly, returned it to our knight.

He wore it on his finger, day and night.

He gave it to Angelica, for fear

That it would impair the power of the shield;

And so those eyes might stay yet bright and clear,

(Despite its power) to which his own did yield;

For the monstrous whale chose to reappear,

Whose vast belly quite half the sea concealed;

Ruggiero showed the thing, and, thereby,

Seemed to add a second sun to the sky.

Its enchanted radiance dazed the sight

Of that dread beast, in the usual way.

As a trout, or grayling, will sink in flight

When the water, once limed, turns clear as day;

So was the monster troubled by our knight,

Belly-up, midst the foam and slime, it lay.

Ruggiero attacked it, here and there,

But its tough skin he failed, thus, to impair.

She begged him, all this while, not to persist,

And to cease from belabouring it in vain;

‘For God’s sake, sir’, she cried, in tears, ‘desist,

And free me, lest the monster rise again;

Better to drown, no longer to exist,

Rather than as this creature’s prey remain.’

Moved by her righteous plea, the knight forbore,

Unchained her then, and raised her from the shore.

Spurred on, his steed took to the air swiftly,

And then flew onwards, speeding through the sky,

With the knight on its back, and the lady

Seated aft, on the croup, as if born to fly.

While the whale lost a meal, that was surely,

Too sweet and dainty for its taste, thereby.

A thousand kisses, Ruggiero, turning,

Pressed upon her eyelids, hot with yearning.

He took a course, not that first intended

Whereby he would encircle all of Spain,

But towards the nearer coast he tended,

Where lesser Britain doth adjoin the main;

An oak grove, by the shore, shade extended,

Where, as ever, Philomena did complain;

In its midst, a meadow, with a fountain,

And on each side, a solitary mountain.

Here the eager knight reined in his bold steed,

And descended to the meadow below,

Where he made it furl its wings, though indeed

It remained prepared for flight, even so.

Then down he leapt and, prompted by his need,

Might well have furthered his desire, but no,

His armour held him tight, and barred the way,

Thwarting his passion, keeping him at bay.

Fretting, now by one tie now another

Betrayed, he sought his armour to undo,

Nor had it ever proven so much bother;

For every one undone, he knotted two!

But this canto has seemed to last forever,

And its great length perchance has weighed on you,

So, I shall set my muse now at her ease,

Until a later time, when she may please.

The End of Canto X of ‘Orlando Furioso’