Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto VIII: Angelica's Plight

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto VIII: 1-4: Ruggiero is seen by a servant of Alcina

- Canto VIII: 5-8: The servant attacks him

- Canto VIII: 9-11: Ruggiero employs the magic shield

- Canto VIII: 12-15: Melissa cancels all Alcina’s spells

- Canto VIII: 16-18: She restores Astolfo, and they fly to Logistilla’s castle

- Canto VIII: 19-21: Which Ruggiero is still struggling to reach

- Canto VIII: 22-28: We return to Rinaldo, gathering troops for Charlemagne

- Canto VIII: 29-34: Then to Angelica, in her encounter with the hermit

- Canto VIII: 35-39: She is stranded on a rock-bound shore

- Canto VIII: 40-44: Angelica’s lament

- Canto VIII: 45-48: The hermit subdues her with a drug

- Canto VIII: 49-50: And tries to rape her

- Canto VIII: 51-61: Of Proteus and the tribute of maidens

- Canto VIII: 62-68: Angelica is captured and offered as a sacrifice

- Canto VIII: 69-78: Orlando’s lament

- Canto VIII: 79-83: His dream

- Canto VIII: 84-91: He sets out to find Angelica

Canto VIII: 1-4: Ruggiero is seen by a servant of Alcina

What a host of enchantresses there are,

Enchantresses, among us, all unknown!

That changing their visages, seek to bar

Their hearts to us, and yet to win our own.

Who, not through the power of any star,

Or with some spell, but by deceit alone,

By feigned affection, fraud, and subtle lies,

Bind our spirit, with a knot naught unties.

Whoever might wield Angelica’s ring,

Or rather that of Reason, could disclose

The true face beneath, thereby revealing

What deceit and art hides; the outer pose,

All that now seems fair and good, unpeeling,

Such that the wickedness beneath it shows.

Well, was it then, that Ruggiero bore

A ring that could expose the very core.

Ruggiero, while feigning innocence,

Had ridden, armed, to the gate (as I said),

And braving the guard, hastened thence,

With his good sword, breaking many a head,

Leaving behind a crew whose poor defence

Had left them sorely wounded, or quite dead.

Towards a wood he’d gone, not far as yet,

When he a servant of Alcina met.

This servant bore a falcon on his wrist,

One he flew, for his pleasure, every day,

Now on the plain, now by a lake amidst

The fields, where’er the hawk might find its prey.

His faithful dog accompanied him, to assist,

His horse had modest trappings I may say;

On seeing how fast our brave knight did fly,

He knew from whence he fled, from whom, and why.

Canto VIII: 5-8: The servant attacks him

The servant approached our Ruggiero,

And, in a haughty tone, demanded where

He was going, and why such haste did show.

Receiving no reply, the whole affair

Seeming plain, this servant, in the know,

Extending the arm, that his hawk did bear,

Cried: ‘What if I should seek to stop you here?

You’ll not escape my hawk, it would appear.’

Then he let loose the bird, that flew so fast

The Arabian steed could not keep pace.

The huntsman leapt from his horse, and cast

Aside the reins; like an arrow it did trace

An arc towards our knight, and when at last

It reached him bit, and reared towards his face,

While, behind, with such speed the servant came

He seemed a roaring wind or burst of flame.

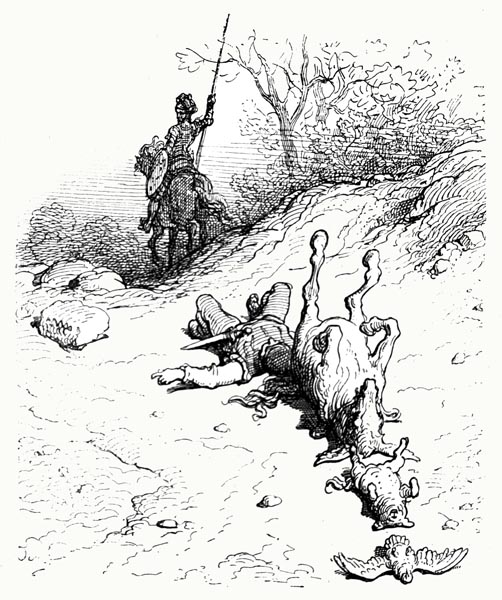

And the dog was no slower to advance,

Snapping hard at his Arabian steed,

Which startled like a hare, now did a dance,

Shaming Ruggiero who turned at speed

Towards the servant, who had seized the chance

To wield his whip, for naught else did he need,

(The whip with which he made his horse obey)

Since Ruggiero’s sword was not in play.

The servant ran at him, and struck him hard,

The dog gnawed his left foot, while, meantime,

The horse, now running free, with nothing barred,

Kicked at his left flank, then tried to climb,

As the hawk, wheeling, with its talons marred

Both steed and rider, adding to the crime,

The Arabian, neath the whip’s flaying,

Neither guiding hand nor spur obeying.

Canto VIII: 9-11: Ruggiero employs the magic shield

Ruggiero, at last, unsheathed his sword,

And, to free himself from their bold attack,

He threatened now the servant, now the horde

Of creatures, with the point and now the back,

Which annoyed them more; with one accord,

They rushed at him, again, and blocked the track.

Our brave knight knew dishonour now, and shame,

Was his, if he allowed more of the same.

He also knew that little time remained

Before Alcina gathered her full strength;

The tower bells, and drums, and trumpets rained

Their noise upon him, while, throughout the length

Of every valley, men and horses strained

To reach the scene, and this was not a tenth

Of all her forces; yet to make these yield

With naked blade seemed wrong; best use the shield.

He raised the cloth that old Atlante’s work

Enclosed, scarlet in hue, which kept it hid;

The shield, once freed from where its light did lurk,

Sent out that glare which no eye could forbid;

The servant gave a single sudden jerk,

And fell, the dog too, as the fierce horse slid

To the ground, while the falcon failed to keep

Aloft; and there he left them, fast asleep.

Canto VIII: 12-15: Melissa cancels all Alcina’s spells

Alcina, meanwhile, having heard the tale

(Of how our knight had forced the outer gate,

Killed her men, and now pursued the trail

To her sister’s realm) near died from distress.

She tore her robe, she struck her face, now pale,

Berating herself for her foolishness.

And gave the calls to arms, while, instantly,

She gathered round her all her strong army.

She divided it in two, then she sent

One half in Ruggiero’s direction,

The others, at the port, made swift ascent

Into her ships, which now sailed into action,

Darkening all the waves beneath them pent.

With them Alcina, troubled to distraction,

Blinded by her love for Ruggiero,

Embarked; her city, left unguarded, though,

Was open to Melissa, who now seized

The opportunity to liberate,

From her evil realm, those she’d been pleased

To prison there, in miserable state;

And comfort them, of their ill plight now eased;

And all her wicked plans thwart and frustrate,

Break seals, burn images, and void the lots,

Shatter the rhombs, and free enchanted knots.

And then through all the fields she passed apace;

There every former lover who’d been changed

To beast, fount, tree, or stone, in that vile place,

She returned to his own form; wide she ranged.

They, once restored, their freedom did embrace,

And following the knight’s path, they exchanged,

Their present realm for that of Logistilla,

Bound for Ind, Persia, Greece, or Scythia.

Canto VIII: 16-18: She restores Astolfo, and they fly to Logistilla’s castle

For each, to his own country, she sent, though

Under an eternal obligation,

And, before the rest, she changed Astolfo,

Restoring his human face and station;

For the noble courtesy he did show

Ruggiero, despite his transmutation,

And his kinship with that warrior, weighed

With Melissa, who granted him her aid,

For Ruggiero had returned the ring,

Which now helped her to restore Astolfo.

Wise Melissa thought it less than nothing

If his armour and lance were lacking, though;

That golden spear that to the earth would bring

Any knight, with a first, and only, blow.

Once Argalia’s, twas now Astolfo’s lance,

And, great renown it brought to both in France.

Melissa sought for it, and found it there,

In the palace, placed there by Alcina,

With all the armour that he used to wear,

Taken from him, in that evil harbour;

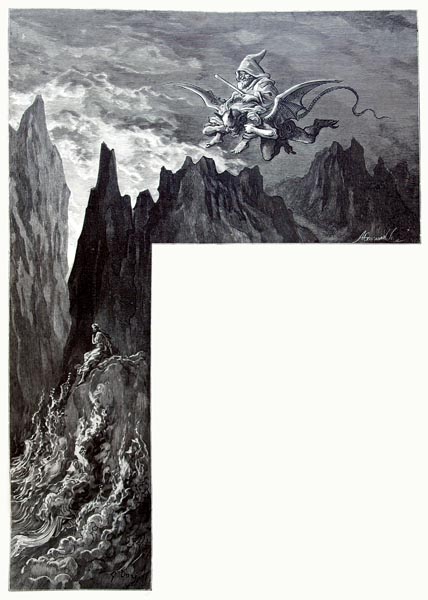

Then mounting that creature, strange and rare,

Atlante’s, set Astolfo behind her,

And reached fair Logistilla’s castle so,

An hour, at least, before Ruggiero.

Canto VIII: 19-21: Which Ruggiero is still struggling to reach

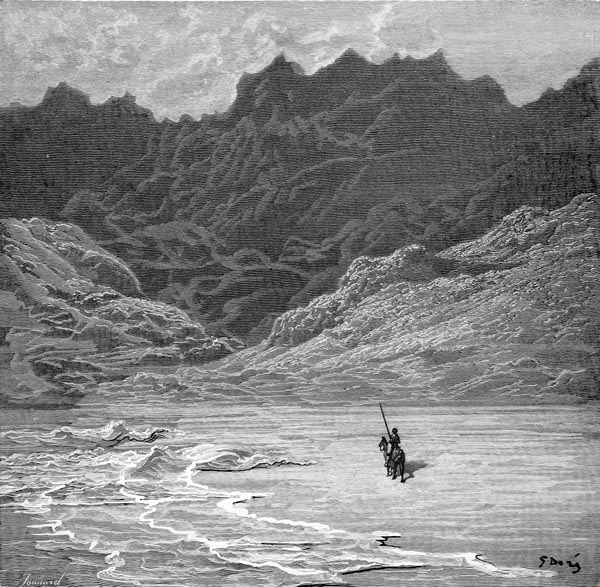

Amidst rough stones, and spiny thorns, our knight

Strove to reach the kinder sister’s dwelling,

From vale to vale, from mountain height to height,

Wild, solitary, harsh and forbidding,

Till, wearied, he arrived, in the broad light

Of noon, above a steep slope descending

To a strand, open to the south, below,

Deserted, bare, and parched, where naught would grow.

The burning sunlight struck the hills around,

While the heat they reflected made the air

And the sand so hot that the very ground

Well-nigh turned to molten glass in that glare.

Not a bird but some shady nook had found,

The cicadas’ tedious hum the sole sound there,

Among the trees, above the bay, their cry

Deafening cliffs and gullies, sea and sky.

The heat, his thirst, and his sheer weariness

(From treading that deserted sandy shore,

Both hard labour and painful to excess)

Proved poor company, you may be sure;

I’ll leave him there, to suffer, nonetheless,

Such subject matter ever proves a bore,

To chill Scotland, seeking brave Rinaldo,

I’ll turn, from the hot, parched Ruggiero.

Canto VIII: 22-28: We return to Rinaldo, gathering troops for Charlemagne

Now, Rinaldo was held in great esteem

By the king, and his daughter, and the court,

And so, the time was right, it now would seem,

To explain his embassy, in that he sought

Levies from England, and the very cream

Of Scotland’s forces, so he, as he ought,

Not only gave good reason for the thing,

But petitioned, for Charlemagne his king.

The monarch swiftly granted a reply,

That whatever of his forces were required,

To fight with honour, all would live and die

To serve King Charlemagne, in arms attired.

And in a few days hence, he would supply

As many knights and men as were desired.

And were he not so old in tooth and claw,

He would have led the troops, as long before.

Nor would that alone have held him back

Were it not that he had a son, and he,

Of strength, intellect and skill had no lack,

And had often led their foot and cavalry,

Cautious in defence, and skilful in attack.

Though he was then absent from that country,

He expected his return; he would be there,

Once his lords had gathered for the affair.

So, he sent his summons through all the land;

The wealthy must send horses and good men,

Prepare the ships and arms, and have to hand

Much gold, and of pure silver more again;

Rinaldo, meanwhile, sailed straight to England,

The king escorting him to Berwick, then

Parting from his guest, with deep emotion;

He was seen to shed a tear on that occasion.

A favourable breeze blew, and Rinaldo

Embarked, and wished farewell to those ashore,

The sails now filled before the breeze, and so

They voyaged, till the River Thames they saw,

Just as the rising tide began to flow.

They worked upriver with both sail and oar,

Secure in their progress, till, at the flood,

Their ship within the port of London stood.

Sealed letters were presented by Rinaldo,

To the Prince of Wales, from Charlemagne,

Besieged there, in Paris, and King Otho,

Requesting soldiers for a bold campaign.

Whatever forces he could raise must go,

Promptly, by ship to Calais o’er the main,

To bring aid, and the cause there to advance

Of England, and King Charlemagne, and France.

This Prince, who now held the land for Otho

And administered the kingdom in his stead,

Deigned to show such honour to Rinaldo,

As the king would have shown, let it be said;

And all those summoned now to fight the foe,

From Britain, and the isles about, were led

To the harbour where his fleet now lay,

Assembling there, by the appointed day.

Canto VIII: 29-34: Then to Angelica, in her encounter with the hermit

Yet, now, I must change my tune once more,

As the musician makes his instrument

Change key, and vary from what went before,

And strikes a flat, a sharp, so I, intent

Upon Rinaldo on that foreign shore,

Thought of Angelica, on flight still bent,

Who, while escaping him, a hermit met;

For, in that place, I’ve left the maid as yet.

I wish now to pursue her tale awhile:

I told how she had asked courteously,

Fearing Rinaldo whom she did revile,

The nearest way by which to reach the sea,

For she thought to die, so great her trial,

Since Europe treated her so savagely;

Yet the hermit caused her some delay,

Finding it pleasant to prolong her stay.

Her rare beauty had so inflamed his heart,

It warmed his bones to the very marrow,

Thus, when he saw her yearning to depart,

And loathe to stay, even till the morrow,

He pricked the mule, cruelly on his part,

Though it scarcely sped off like an arrow,

So slow its pace that it could barely trot;

It looked to pursue her, but had rather not.

And since the maid was swiftly out of sight,

And, in a while, would be beyond pursuit,

The monk returned to his dark cell outright,

And summoned up a horde of imps to suit,

Selecting one of them, a wicked sprite,

And telling him to haste along her route,

And enter in the steed, like Cupid’s dart,

That, with the lady, bore away his heart.

And as a dog accustomed to the chase,

That hunts the hare, or runs the fox to ground,

Will, if it sees its prey swerve, for a space

Appear to lose the trail, and hunt around,

Yet when its master rides there, at full pace,

Has thwarted all, and on the kill is found,

The monk, and by a means that we now know,

Will meet the lady, where’er she may go.

What was the monk’s design I know full well;

And shall explain, but in another place.

Angelica knew naught of what I tell,

And rode all day, now fast, now slow, her pace.

Within her steed, the imp now worked its spell,

As a hidden fire will smoulder, for a space,

To break out later in a towering blaze,

None can escape or quench, and none obeys.

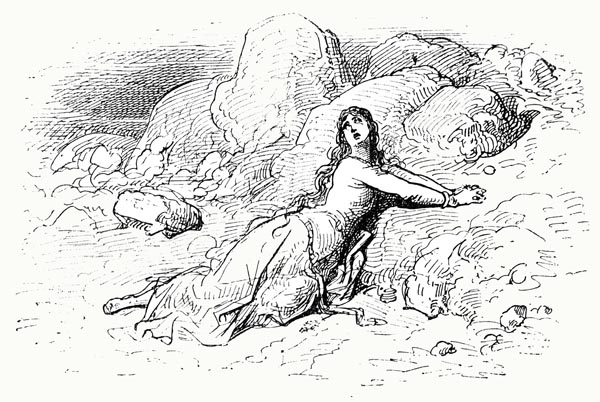

Canto VIII: 35-39: She is stranded on a rock-bound shore

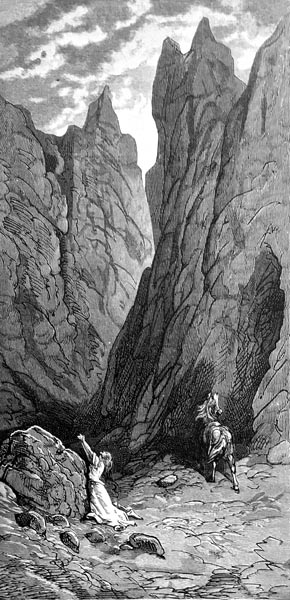

Now, once Angelica had reached the shore

Where the waves lave the coast of Gascony,

She rode upon her horse a mile or more,

Where’er the sand was firm, close by the sea,

Yet the imp drew her mount towards the roar

Of the breakers, and plunged it, suddenly,

Into deep water, the maid, in her fright,

Left no recourse, except to cling on tight.

She’d no time to use the reins, nor did dare.

All the while her steed was plunging deeper.

She but drew her feet higher in the air,

And dragged her garments closer about her.

While round her shoulders fell her loosened hair,

As the wanton breeze grew ever bolder.

Yet wind and sea scarce harmed the maid, as though

They both paid tribute to her beauty so.

She turned her eyes towards the shore, in vain,

A flood of tears poured down her breast and face,

Seeing the land more distant, midst the main,

And shrinking ever, o’er the widening space.

Yet her palfrey towards the north did strain,

And, in a wide curve, bore her to a place

Surrounded by dark cliffs, and fearful caves,

As evening cast its shadows on the waves.

Finding herself on that deserted strand,

Which, to her anxious mind, alone brought fear,

Gazing as Phoebus, sinking, far from land,

Yielding to night, began to disappear,

Fixed like a statue, there, the maid did stand;

To any eye it would have proved unclear,

If this were a living woman, to the view,

Or merely some rock, like to her in hue.

Uncertain, gazing, stunned, in deep distress,

Her hair all loosened, blowing in the breeze,

Her hands in prayer, her lips yet motionless,

Her eyes turned heavenwards, as if to seize

Upon the cause of her unhappiness,

Blaming the powers above for her unease.

Unmoving, as if dazed, she stood awhile,

Then gave vent to her grief, in tearful style:

Canto VIII: 40-44: Angelica’s lament

‘Fortune, what more now can you do to me,

That might serve to satiate your anger?

What can I yield, drowned thus in misery?

My life, perchance, and suffer here no longer?

Yet you sought it not, for you, momently,

Wished me borne from out the deepening water,

So that you might torment me yet on land,

Before I die on this dark, barren strand.

I cannot see how you could harm me more;

Through you I’m exiled from my royal throne

Doomed to flee, to sail from shore to shore,

Ne’er to return, abandoned and alone,

And my lost honour, thus, can ne’er restore,

For though I have not sinned, yet, I must own,

A vagabond, I’ve fuelled the idle chatter

That calls me shameless, and debates the matter.

What good, in this world, can a woman find,

Whose chastity is questioned, and honour?

It harms me that I’m young, and some are kind

Enough to think me beautiful; however,

No thanks are due to Heaven, to my mind,

For such a gift, it only makes one suffer.

For this, Argalia, my brother, died,

Though he with magic weapons was supplied.

For this, Agricane, King of Tartary,

Subdued Galafrone, who was my father,

That, as Khan of Cathay, had mastery,

There in India; yet I’ve a humbler

Place now, doomed to roam eternally,

Seeking lodgings for the night, wherever.

You’ve robbed me of wealth, kin, and honour too,

What greater harm, Fortune, is there in you?

Since death by drowning failed to satisfy

Your cruel intent, then produce some monster

To devour me, and end my pain thereby.

There is no fate you could have me suffer,

For which I would not thank you; let me die,

Be it twixt the jaws of some vile creature!’

Yet, as she grieved, breathing many a sigh,

The hermit, suddenly, appeared nearby.

Canto VIII: 45-48: The hermit subdues her with a drug

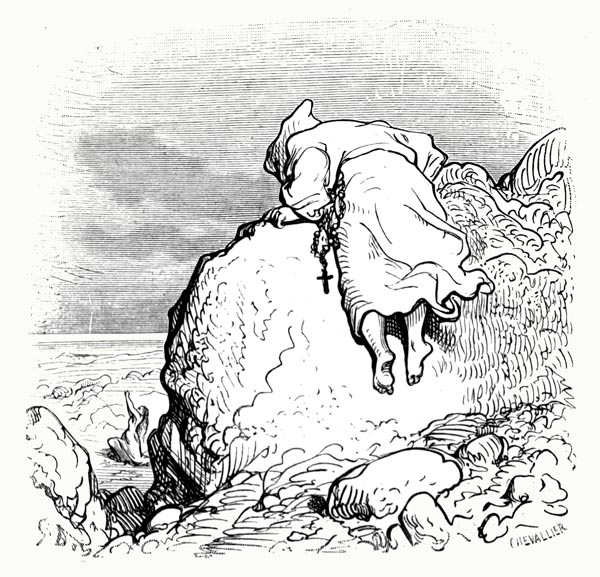

On the heights above he’d sought to stand,

Mounting the summit of a towering rock,

Watching Angelica, now reaching land

Dismayed, afflicted, in a state of shock.

A full six days before, you understand,

He’d been borne, by a demon, to that block

Of stone, and now, feigning true devotion,

Approached, like Paul or Saint Hilarion.

Now, when Angelica saw the monk appear,

She found a deal of comfort in the sight.

His presence there allayed her previous fear,

Though her face was deathly pale in the light.

‘O woe is me!’ she cried, as he drew near,

‘Holy father, how dire is my sad plight.’

And, sobbing loudly, did her tale pursue,

The which, small wonder, he already knew.

The hermit now set out to console her,

Giving her several reasons not to pine,

And, thereby, allowed his hand to linger,

Now on her cheek, now on her neck so fine,

Then, feeling secure, moved to embrace her,

While she, perceiving his perverse design,

Scornfully, set her hand against his breast.

She fell; in blushes all her face was dressed.

Now the hermit had a pouch at his side,

Which held a little vial full of liquid,

And over the eyes, where Love doth abide,

And sparks from his brightest torch lie hid,

Sprinkled a drop or two, which once applied

Had the power to bring sleep, as now it did.

Upon the sand, now unaware, she lay,

To all the old man’s worst desires a prey.

Canto VIII: 49-50: And tries to rape her

He embraced and fondled her at leisure,

While she slept on, unable to resist;

Now her breasts, and now her mouth, brought pleasure,

No eye could see him in the evening mist;

And yet he failed to obtain full measure,

For his weak charger stumbled in the list;

He was anxious; too many years it bore;

Indeed, the more he worried, then the more

All seemed in vain, for every ruse he tried,

The useless creature still refused to rise;

He tugged at it, a while, and heaved, and sighed,

Yet could not raise its head, despite his cries.

In the end, he fell asleep, by her side.

Yet a fresh disaster before him lies,

Since Fortune ne’er does aught by halves, when she

Subjects a man to shame and misery.

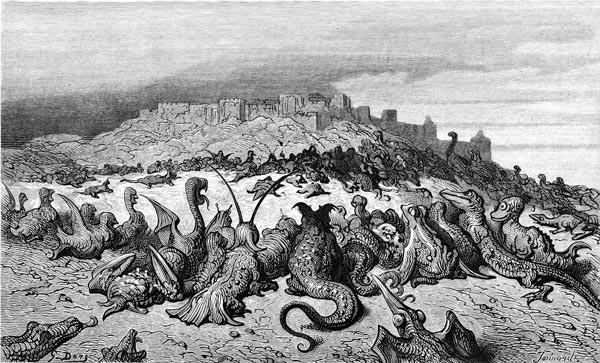

Canto VIII: 51-61: Of Proteus and the tribute of maidens

Before I tell you more, I need to veer

From my present course a little while.

For, if towards the West you were to steer

Past Ireland’s coast, you’d come upon an isle.

Ebuda, it is called; scant folk appear

On those shores, for the orca, we revile,

And other sea-creatures, denude the place:

Old Proteus takes vengeance on that race.

The ancient legends, whether false or true,

Say that once a powerful king ruled there,

Who had a daughter; she so fair to view,

So graceful, tis no wonder that, whene’er

She was seen, Proteus would burn anew,

Midst the waters, while she took the air,

And, finding her alone one day, defiled

The helpless maiden, and left her with child.

This rape was a torment to the father,

Viler, more impious than aught he knew.

No excuse, no pity, quenched his anger,

Such was its force, against his own issue.

Nor did her state persuade him to defer

Her punishment which he did swift pursue;

For he condemned her and the child to death,

Before the babe had taken its first breath.

Now Proteus, who nurtures his great herd

Of sea-creatures for the god of the sea,

Mighty Neptune, of her sad plight had word,

And in his anger, quite unlawfully,

Against that isle his ocean monsters stirred,

(Orcas, and sharks, and whate’er else may be

Lurking beneath the waves) to slay them all,

Herds, flocks, and people, at his martial call.

And then in force he did assault the place,

Each town or village, and lay siege around,

Where fearful and weary folk must face

A tedious watch to secure their ground.

Abandoning their livelihoods, that race

As a last recourse, then agreed to sound

The oracle, for counsel; by and by,

It spoke to them, and yielded this reply:

That they must find a maiden in that land

Who was equal in beauty to the other;

And offer her to Proteus, on the strand,

In exchange for slaying the king’s daughter.

And if he thought her, once she was at hand,

As fair, he would keep her, and no longer

Attack the isle; if not, they must provide

Another, till that sea god found a bride.

And so, the deadly custom commenced,

Whereby a maiden who was fair of face,

Was led to Proteus each day, from thence,

Till one seemed pleasing, in her looks and grace.

The others were but prey, without defence,

Fed to a giant orca, that kept place

Beside the port, and patrolled the shore,

Till the sea god left the isle once more.

Whether the legend be false or true,

(For there is none I know of who could say)

Such a tribute had been offered, when due,

(A vile crime against woman) to that day,

Enshrined in law by that impious crew;

The monstrous orca fed on maids, I say.

Though to be a woman brings, everywhere,

Trouble and oppression, twas far worse there.

O unhappy maids whom misfortune brought

To that unhappy land, and dire distress!

For that folk ever some stranger sought

On whom to perpetrate their wickedness,

Since the more maids from elsewhere that were caught

In their snare, by so much their toll was less.

Yet since the breezes oft brought none to shore,

On every foreign strand they looked for more.

In frigates, galleys, in whate’er would float,

They roamed about the seas, and gathered in

All the maids that they found, that seemed of note,

To aid their tribute, dire as was the sin.

Some they took by force into their boat,

Some by flattery, stealth, or gold did win,

And plundering thus, from the wider region

Filled up every tower, and every prison.

Voyaging, one day, from land to land,

They came upon that solitary shore

Where Angelica slept, upon the strand,

Midst tufts of grass, but on a stony floor.

For water, and what wood there lay to hand,

Those pirates landed, to refill their store;

Thus, the fairest flower of earthly charms

They found there, in the holy father’s arms.

Canto VIII: 62-68: Angelica is captured and offered as a sacrifice

Oh, too noble and far too dear a prey,

For so barbarous and villainous a crew!

Oh, who would credit it, that you hold sway

Fortune, o’er all things mortal, as you do!

That to feed the monster you’d bear away

Such beauty, that which Agricane drew,

From the Caucasus, to India, in state,

With half Scythia, to embrace his fate.

That beauty which King Sacripante set

So far above his honour and his crown;

That which saw Rinaldo swift forget

His better judgment and his fair renown;

That beauty for which whole armies met,

And turned the whole Levant nigh upside-down;

And now has naught to aid it, not a word,

So lonely that its cry must go unheard.

That lovely woman still oppressed by sleep

Was a prisoner, in chains, ere she woke.

The hermit sorcerer they chose to keep

Beside her, on the ship, with other folk;

This done they then sailed out upon the deep,

And returned to their island; not one stroke

Of a sword to prevent them, where their prey

They immured, to await the fatal day.

But her beauty, being great, moved to pity

That savage race, who for many a day

Delayed, until they deemed it necessary,

Her fate; and, while the monster made away

With others snatched from some foreign country,

They spared Angelica, until, I say,

As tribute to the monster, they did bring

The maid, with a tearful crowd following.

Who shall describe the anguish, and the cries;

The lament that rose to heaven above?

If the earth had opened, twere no surprise,

When to the cold stone she must remove,

Where chained, no help indeed could now arise,

And death awaited, and most harsh must prove.

I shall not; for such grief I feel too deeply;

My verse must take another path completely,

And seek lines of a far less mournful kind,

That might my weary spirit now restore,

For nor the squalid serpent, to my mind,

Nor the tigress with her savage roar,

Grieving her lost cubs, nor aught men find

Twixt the Atlantic and the Red Sea shore,

Foul and venomous, but must bemoan

Angelica, chained to the naked stone.

Oh, if it were but known to Orlando,

Who had left for Paris, in search of her,

Or that pair the cunning old man had so

Deceived, with a message from the other

Stygian world; among the dead they’d go,

A thousand times, her traces seeking ever,

That sweet angelic maid; yet, if they’d known,

What could they do, far off, and she alone?

Canto VIII: 69-78: Orlando’s lament

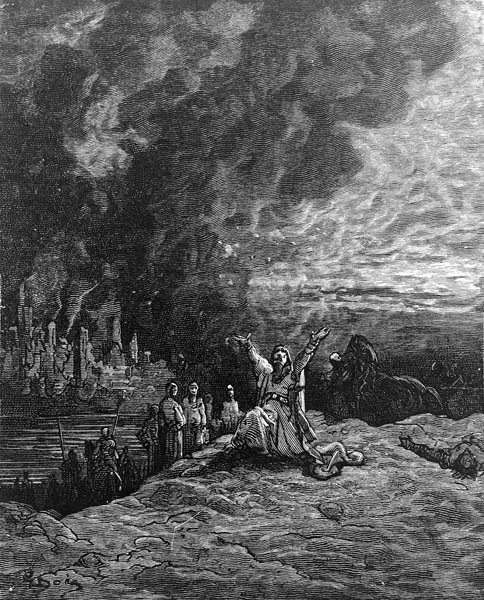

Now Paris, besieged by the enemy,

(This Agramante, King Troiano’s son)

Was reduced to such dire extremity

That the war he had waged was well-nigh won.

And were it not that shows of piety

Placated the heavens, that hid the sun

And brought on heavy rain, the Moorish lance,

Had seized the Empire, and the realm of France.

For the supreme Creator’s eyes had turned

To the aged Charlemagne’s just complaint,

And quenched the fire before fair Paris burned,

By more than human art, which is but faint.

Wise are those who have this lesson learned,

To seek God’s help who suffers no constraint.

Twas well the pious Emperor understood

Aid came from heaven, source of all his good.

Orlando lay, devoid of sleep, one night,

Many a thought passing through his mind,

Of one kind and another, many a flight

Of fancy, seized, yet swiftly left behind;

Like clear water glittering with the bright

Sun’s rays, or by the risen moon defined,

Issuing light from out its sparkling flow,

Now to left or right, now high, now low.

To him came the memory of his lady,

Although in truth it was ever present,

Stirring the flame in his heart that quietly

Burned by day, rendering it more ardent.

From far Cathay, with him, on his journey,

She had come, and yet, to his discontent,

Was lost, leaving no trace he might follow,

When Charlemagne was routed, near Bordeaux.

Orlando grieved at this, and reflected,

Although in vain, on his past foolishness:

‘Dear heart, how sad that I e’er elected

To mistreat you; it pains me to excess,

That, by night and day, I so neglected

You that always sought to show me kindness,

Leaving you in the hands of old Namus,

Nor challenged that wrong, so injurious.

Had I not good cause to wait out the fight?

Nor would Charlemagne have refused me.

And if he had, who then, in my despite

Would ever have dared to take you from me?

Would I then not have armed myself, outright,

Rather than let them do so? Most surely.

Nor Charlemagne, nor all his host beside

Could have served to tear you from my side.

Oh, if he had but placed you in the care

Of his guards, in Paris, or some fortress!

All, since he left you with Duke Namus there,

That calms me, is that he caused your distress,

Not I. Who better, in that sad affair,

Than I to guard her, to the death no less,

Better than my own eyes and heart indeed,

And could and should have done, as I concede?

Where are you now, thus torn from me, dear heart?

So young, so lovely, a lamb, at the fall of night,

Lost in dark woods, far from the flock, apart,

That bleats aloud, hoping the shepherd might

Hear her cries, ere he chooses to depart,

Ere the wolf hears her in the distance, plain,

And the sad shepherd weeps for her, in vain.

Where are you now, my love? Wandering still,

Alone, as lost, perchance, and grieving so;

Or has the cruel wolf spied you from the hill,

And you defenceless, lacking, thus, Orlando?

Is the flower that amongst the gods yet will

Enthrone me, the flower that I’ve yet to know,

Intact (for your chaste spirit I sought to guard)

Or culled perchance, by force, its blossom marred?

O, wretched fool, what’s left me but to die,

If the flower is culled, and so seek an end?

O, Lord above, let me but weep and sigh

For every other woe but this you send.

If such be true, my hand shall life deny,

And yield the spirit, that doth so offend.’

Lamenting to himself, and sighing so,

Complained the sad and tearful Orlando.

Canto VIII: 79-83: His dream

All beings, everywhere, now sank to rest,

Granting repose to spirits full of care,

Some on cold stone, some in their feathered nest,

Amongst the grass, midst beech or myrtle there.

And yet, in pain, Orlando, thus oppressed,

Closed his eyes, with many a wound laid bare,

Nor would his thoughts allow untroubled sleep,

All was but fleeting, neither long nor deep.

It seemed to him that on some grassy shore,

And all amidst the scent of flowers, he viewed

That ivory, that unmarred bloom, once more,

That Love with his own hand had so imbued

With colour; those bright eyes again he saw,

That to his famished spirit served as food.

I speak of those bright eyes, the lovely face,

That stole his heart, and did his spirit grace.

He felt the greatest joy, the greatest pleasure

That ever a happy lover could know,

Yet, behold, a storm, in rapid measure,

Wasted the flowers and trees, and brought them low.

No faster is the garden stripped of treasure

Than this, when north, or south, or east winds blow.

And through the wasteland, then, he seemed to stray,

While seeking cover from the storm alway.

Meanwhile the sorry lover lost his lady,

Vanished in dark cloud, he knew not how.

He made the woods and fields echo loudly

With her fair name, the while; with troubled brow

He kept repeating, sadly: ‘Woe is me!

Who renders all my sweetness bitter, now?’

And heard his lady cry, requesting aid,

For many a heartfelt call to him she made.

He sought the place from which the sound arose,

Wearying himself, running here and there.

Oh, how fierce the grief how deep his woes;

Those sweet eyes he sought for everywhere.

Another voice cried then, at which he froze:

‘Hope not for joy on earth, here find despair!’

At this cry he awoke, and found his eyes

Full of sad tears, that flowed forth at those cries.

Canto VIII: 84-91: He sets out to find Angelica

Forgetting that those visions are untrue,

That doubt or passion conjure, when we dream,

He simply felt his lady’s plight anew,

Exposed to harm, and shame; his pain extreme,

As, leaping from his bed, his fears grew.

He donned his armour, and then, all agleam,

Sought out Brigliadoro, his strong steed,

Nor for a squire’s assistance found the need.

And so as to pass everywhere, and yet

Not mar his dignity in any way,

He chose his honoured pennant to forget,

Quartered in, red and white, but showed, that day,

One all in black, perchance because it met

The needs of one who grieved; in an affray

He’d won it from a brave and steadfast knight,

Whom he had slain, and in that very fight.

At midnight he departed, silently,

Without word to his uncle, Charlemagne;

Nor to Brandimarte, whose loyalty

He cherished, did he seek to explain

His departure; but when the Sun rose free

From Tithonus’ rich lodgings, and did deign

To drive away the shadowy mists of night,

That emperor soon missed his faithful knight.

With great displeasure Charlemagne now heard

His nephew had departed ere the dawn,

(Though he had need of him) without a word,

Nor could he curb his anger, but did mourn

Lamenting loudly, blame on him conferred,

Crying that he’d wish he’d ne’er been born;

Threatening that, if the knight did not return,

Many a weighty punishment he’d earn.

Now Brandimarte, whom Orlando loved

As firmly as his own self, would not stay,

Whether he hoped Orlando might be moved

To return, or whether he felt dismay

That his companion had been thus reproved,

And, ere the eve, sought to be on his way,

Saying nought to his Fiordelisa,

Lest she demanded that he not leave her.

This was a lady, she his true delight,

One who was rarely absent from his side,

Endowed with manners, grace, fair to the sight,

Her wit and wisdom not to be denied,

And if he went now, ere the fall of night,

Without taking leave, nor sought to confide

In her, well, he thought to return outright;

Yet events would serve to detain the knight.

And when she had awaited him, in vain,

For nigh on a month, and he gave no sign,

Without companions, or a guide, in train,

She left, her longing such; and, by design,

Her search through many lands did sustain,

Of which I’ll tell in this long tale of mine.

Though no more as yet, since brave Orlando

Is now my care; for more of him I’d show.

He, foregoing Almonte’s red and white,

Had ridden to the gate, but in the ear

Of the staunch captain there, our mournful knight

Whispered: ‘It is the Count.’ soft but clear,

And so, the drawbridge was lowered outright,

O’er which the road ran, that must bring him near

The battlefield, and lead towards the foe.

What followed, is fuel for the next canto.

The End of Canto VIII of ‘Orlando Furioso’