Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto VII: Alcina the Sorceress

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

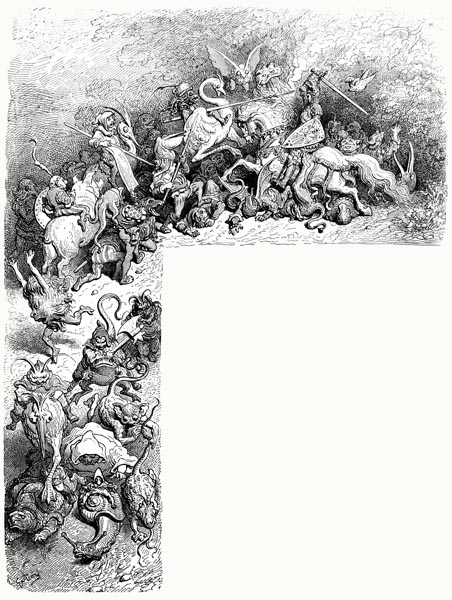

- Canto VII: 1-7: Ruggiero conquers the giantess Eriphila

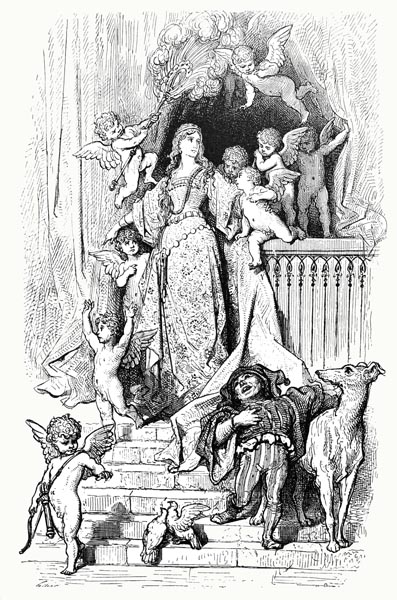

- Canto VII: 8-10: He arrives at Alcina’s palace

- Canto VII: 11-15: Her beauty described

- Canto VII: 16-18: Ruggiero is instantly in love with her

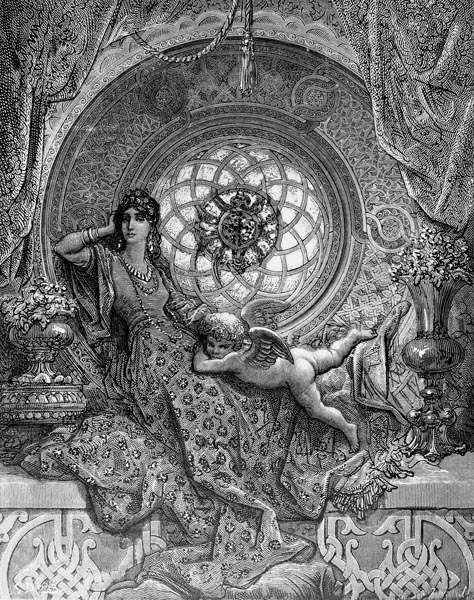

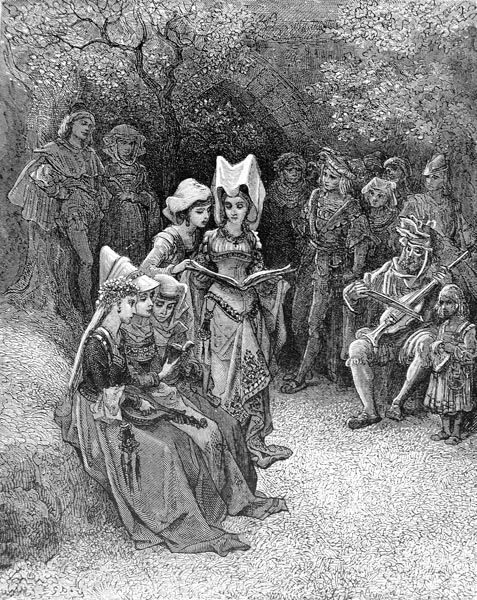

- Canto VII: 19-23: At the feast, they agree to meet that night

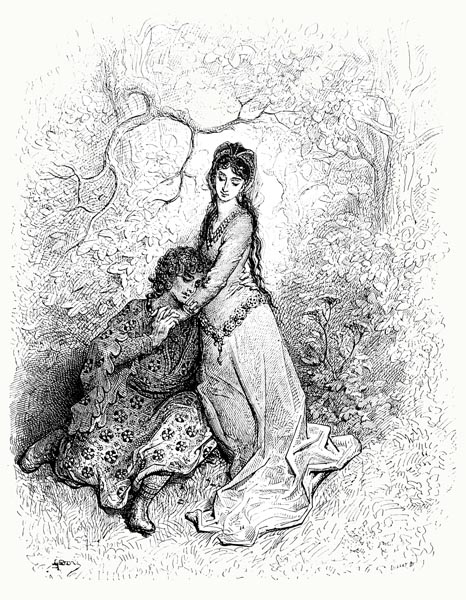

- Canto VII: 24-29: Alcina and Ruggiero fulfil their pledge

- Canto VII: 30-32: They take their pleasure

- Canto VII: 33-36: We return to Bradamante, Ruggiero’s lover

- Canto VII: 37-41: She decides to re-visit Merlin’s Cave

- Canto VII: 42-45: But Melissa intercepts her with news of Ruggiero

- Canto VII: 46-50: The sorceress commits to rescuing Ruggiero

- Canto VII: 51-55: She visits him, in the guise of Atlante the sorcerer

- Canto VII: 56-64: She reproaches him for his loss of virtue

- Canto VII: 65-67: Melissa returns to her true form

- Canto VII: 68-71: Ruggiero’s love for Alcina turns to loathing

- Canto VII: 72-75: He perceives her true form

- Canto VII: 76-80: He escapes Alcina’s realm

Canto VII: 1-7: Ruggiero conquers the giantess Eriphila

He who travels far from his own country

See things which are believed, when far from view,

Yet when he tells of them, subsequently,

He’s thought a liar, and such things untrue;

And thus, the vulgar crowd, ignorantly,

Reject all sights their eyes cannot pursue;

And having seen naught of these things I tell,

Will merely deem this canto lies, as well.

Whatever I may own to, there’s no need,

To pander to the ignorant and vulgar.

I know you will believe what you now read,

In whom the light of intellect shines brighter;

And hence for you alone I write, indeed,

To render dear the fruits of all my labour.

I left you at the bridge above the river,

Defended by the giant Eriphila.

Her armour was of metal pure and bright,

With many a rich-hued gem set therein,

The crimson ruby, yellow chrysolite,

Tawny jacinth, the pale jargoon its twin,

Green emeralds too. She rode to the fight,

On no horse, but a wolf with savage grin.

Astride that wolf she rode beside the river;

Richer saddle none has mounted ever.

No larger wolf lives in Apulia;

This was bigger than a bull, and taller;

And although unbridled, it was tamer

Beneath her hand than a faithful charger.

Her surcoat was of a sandy colour,

That cast a sickly hue o’er the armour,

A coat which, but for that, was of the sort,

That both bishops and prelates wear at court.

She had, upon her shield and helmet’s crest,

As emblem, a venomous, swollen toad.

The maidens our valiant knight addressed,

Explaining this was how she barred the road,

Prepared to fight, for she was wont to test

The traveller who stout resistance showed.

‘Turn back, sir knight!’ the giantess now cried;

He took a lance, and her bold threat defied.

And no less promptly did the giantess

Spur the wolf, and sit tall in the saddle,

While, in mid-course, her lance she did address,

Making the very earth beneath her tremble,

Yet our hero held his ground, nonetheless;

He struck, beneath her helm, in the middle,

And so dislodged her, with such force indeed

She landed six full yards behind her steed.

Already had the knight unsheathed his sword,

Ready to rob her of her once proud head,

And well he might, since she lay on the sward,

Among the herbs and flowers, like one dead,

But both the maidens cried: ‘Hold off, my lord,

Since she is conquered, let no blood be shed.

Sheathe your sword, our courteous champion.

Now, we may cross the bridge, and journey on.’

Canto VII: 8-10: He arrives at Alcina’s palace

The path ran onwards through a grove of trees,

Quite rough and awkward to negotiate,

But then led upwards and, with greater ease,

They climbed where all was stony now and straight.

Ascending to the summit, by degrees,

They reached a meadow (its extent was great)

And saw a gracious palace, lovelier

Than any that the eye might discover.

The fair Alcina had advanced some way

Beyond the gate, to greet Ruggiero,

With all her noble court, in fine array,

And to the knight great honour there did show,

While the court did every reverence pay

To our knight likewise, honouring him so

They could have done no more, I’d testify,

Were Jupiter descended from the sky.

The palace owned no greater excellence,

Exceeding every other in its splendour,

Than the company was, in every sense,

The most courteous and pleasing, ever,

For youth and beauty; let me not commence

To choose amongst them all; yet still fairer

Was Alcina, midst that fair court, by far;

As, to our eyes, the sun outshines each star.

Canto VII: 11-15: Her beauty described

Her form was such, as artists labouring

Would find it difficult to recreate,

So shapely; her knotted tresses coiling,

Far brighter than gold of purest state;

The colours of rose and lily glowing

Upon her cheeks, so soft and delicate.

Her brow was clear as is smooth ivory,

And rounded out, in perfect symmetry.

Two dark and slender eyebrows curved above

Two clear dark eyes, that shone like two bright rays,

With calm yet kindly gaze that scarce did move,

And from them, Love, that ever sports and plays,

Scattered his shafts, and no mean archer proved,

Piercing hearts, in a hundred thousand ways.

The nose, in perfect line, the face descended,

Where Envy could find naught to be amended.

Beneath it, where two fair vales almost met,

Her lips revealed their hue, pure cinnabar;

Within, two rows of finest pearls were set,

That those sweet lips could or display or bar,

Or thence release fair words to soften yet

The hardest heart, and some man make or mar.

And, there, a gentle smile to that gave birth

Which seemed to offer paradise on earth.

The breast as white as milk, the neck as snow,

A lovely column; full and large the breast,

Where two unripe and ivory fruits did grow,

That rose and fell, like waves that swell, then rest,

As when some sea-breeze stirs the depths below.

Not Argos’ hundred eyes could spy the rest,

But one might judge of what was so concealed

By all those charms the outer form revealed.

The arms were of a fitting proportion,

And a white hand, now and then, was seen,

Long and slender, and without distortion,

Quite free of any knot or vein, I mean.

And then the feet, the dull earth their portion,

Were small, and neat, as trim as any queen.

Such angelic semblances, heaven-born,

Go all unveiled, as doth the light of dawn.

Canto VII: 16-18: Ruggiero is instantly in love with her

Her every aspect was a subtle snare,

Whether she merely moved, spoke, sang or smiled,

No wonder Ruggiero could but stare,

Who found her pleasing, and was thus beguiled;

The myrtle’s warning helped him little there,

Who thought her false, and so to be reviled;

For who could think betrayal and deceit

Could own such beauty, or a smile so sweet.

Rather he now believed twas right that she

Had so transformed Astolfo on her isle,

Since, proving ungrateful, he was worthy

Of his fate and more, and filled with guile.

And as for all he’d heard but lately,

He thought it prompted by revenge, and vile,

A mere falsehood, born of hate and malice,

Pure poison, proffered in a humble chalice.

Bradamante, the lady that he loved,

Was now wholly banished from his heart,

For, with a spell, Alcina had removed

All traces of that former wound; her art

Ensured that she alone was now approved,

Her love, her image set there; for our part,

Surely, we must forgive Ruggiero,

For the inconstancy he seems to show.

Canto VII: 19-23: At the feast, they agree to meet that night

At table later, lute, and harp and lyre

With other instruments sounded sweetly;

Soft music filled the air about, entire,

One melodious consort, in harmony.

Nor did they lack a fair voice, raised higher,

To sing of love’s deep passion, joyously,

And with choice invention, true poetry,

Give life there to some pleasant fantasy.

What rare feast, both splendid and sumptuous,

That Ninus’ successors might have proffered,

What costly spread, for the bold and famous,

That Queen Cleopatra might have offered,

Could compare with all that the amorous

Enchantress, for her paladin, now spread?

I believe none dine so, in those halls, indeed,

Where Jove accepts his cup from Ganymede.

Once the remnants of the feast were cleared away,

All sat in a circle, and enjoyed a game,

Requesting their neighbour, as if in play,

To whisper in their ear, some secret name;

Delighting every lover, I may say,

Who their love could reveal, in just this way,

And, in doing so, these two pledged outright

To meet together in the dark of night.

The game was quickly ended, and much sooner

In truth than the accepted custom there;

Pages with torches were swift to enter,

Chasing away the shadows everywhere;

Amidst fair company before and after,

Ruggiero to the chamber did repair,

Freshly adorned, appointed for his rest,

And ever reserved for the choicest guest.

And when the almond comfits and the wine

Had been offered, once more, as was fitting,

The others did their heads, with grace, incline,

And went to their chambers, till the morning.

Our knight midst scented sheets, rare and fine,

That seemed like those of Arachne’s weaving,

Lay still, and, listening closely, sought to hear

The sound of his fair lady drawing near.

Canto VII: 24-29: Alcina and Ruggiero fulfil their pledge

At every little movement that he heard,

He raised his head, hoping it might be her,

Believing it was, then that naught had stirred,

And then sank back, sighing at his error.

Often, he left his bed, by longing spurred,

Opened the door, looked out, yet went no further,

While, a thousand times, he cursed the hour

That delayed her elsewhere in the tower.

Often, he thought: ‘Now, she leaves her chamber.’

And counted out the steps along the way,

Twixt her room and his, where in a fever,

Awaiting her, our Ruggiero lay;

Such idle thoughts, and many another,

Crossed his mind, troubled at her delay,

Now fearing some impediment, unplanned,

Might deny the fruit, well-nigh in his hand.

Alcina, when at last she’d put an end

To her application of some rare perfume,

And could no longer her delay defend,

Prepared to go, and issued from her room,

Then, by a secret way, her path did wend,

While all around was silent as the tomb,

To where the warrior in hope and fear

Felt each pierce his heart, like a sharpened spear.

Thus, when Astolfo’s successor saw her,

And felt the warmth flow from those smiling eyes,

It roused a fire in his veins, like sulphur,

For deep delight he now would realise,

And, plunged in a sea of bliss, might linger,

Where beauty grants its joys beyond surmise.

He leapt from his bed, took her in his arms,

For scarce could he wait to reveal her charms.

He thought it fine; no heavy robe she wore,

But only a light mantle, quickly thrown

Over her plain white shift, though this, he saw,

Was of the finest quality e’er known.

As Ruggiero clasped her, to the floor

The mantle fell, she, in her shift alone,

Veiled no more than the lily or the rose,

That, seen through clearest glass, yet brightly shows.

No closer does the ivy clasp the tree,

The branches winding tightly together,

Than did those lovers who, so tenderly,

Their spirits felt upon their lips, forever

Tasting of that perfumed spice that surely

Nor India nor Sabaea offer;

Their deep joy formed the content of their speech,

While mingling two tongues, two languages each.

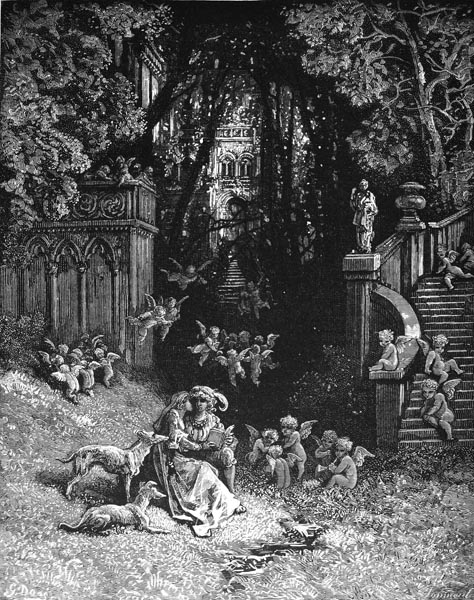

Canto VII: 30-32: They take their pleasure

Whate’er happened there, was kept a secret,

Or if not secret, was ne’er spoken of;

Seldom are any blamed for silence yet,

Though many have had benefit thereof.

Ruggiero, smiled upon by those he met,

Was greeted warmly by the wise in love,

And honoured, and reverenced, as ever,

Since twas the wish of amorous Alcina.

No pleasure there was lacking, since they all

Dwelt within Love’s court, for twas no less,

While for their use, or at another’s call,

Twice, or three times, a day they changed their dress.

Oft they did feast, or banqueted withal,

Jousted, played, acted, bathed, danced to excess,

Or in the shade, by some fount, tenderly

Read from the love poems of antiquity.

Now through the cool vale, and o’er the hill,

They would go chasing the timorous hare,

Now flush the pheasants, with their dogs, at will,

From the fields and bushes, now set a snare

For thrushes, midst the juniper, now fill

Their nets and baskets with such fish as dare

To take the bait, and rise to line and hook

Troubling their secret haunts in pool or brook.

Canto VII: 33-36: We return to Bradamante, Ruggiero’s lover

Thus, Ruggiero dwells, joying, feasting,

Whilst Charlemagne and Agramante fight,

Of whose brave wars I must not cease to sing,

Nor of Bradamante, that maiden bright,

To whom his absence great distress did bring.

She mourned for many a day her lost knight,

Who’d been borne away, amidst the air,

To some distant place; she knew not, where.

Before those others, I’ll speak of this maid,

Who searched for him, many a day, in vain;

Through shadowy wood, or open field, she strayed,

Midst town and city, and by hill and plain,

That ne’er a sign of her dear friend displayed,

Divided from him by the rolling main;

And oft the Saracen host she saw below,

Yet none viewed therein was Ruggiero.

She asked for him a hundred times a day,

But none could answer her, or ease her mind;

She roamed far and wide, rode every way,

Searched every tent and lodging she could find;

This she could do unseen, I ought to say,

The knights, the soldiers, all were as if blind,

Thanks to the ring, whose power did eclipse

Her silent form, when pressed to her soft lips.

She could not, would not, think that he was dead,

Since the sad news of such a knight’s demise

Would from far distant India have spread,

To where the sun dips in the western skies.

She knows not where his errant course has led,

As through the air, above the earth, he flies,

But seeks him everywhere, in company

With sighs and tears, still plagued by misery.

Canto VII: 37-41: She decides to re-visit Merlin’s Cave

She thought, at last, to seek the distant cave,

Where the bones of prophetic Merlin lay,

And there to so lament about his grave

His voice, out the cold marble, might obey

Her request, and the answer that it gave

Show whether he yet saw the light of day,

Or whether fate had quenched his life, and so

Pursue the best counsel that might follow.

With this intention then, she made her way

Towards that wood, close by Pontiero,

Where Merlin’s tomb, amidst the mountains, lay,

That sepulchre from which his voice did flow;

Yet the sorceress, who both night and day

Held Bradamante in her thoughts, also,

The wise Melissa, who in that fair cave

To her some knowledge of the future gave,

That benign, and ever-wise, enchantress,

Viewing the warrior-maid as in her care,

Knowing she would prove the fair ancestress

Of peerless rulers, demi-gods would bear,

And wished to know her deeds, and no less

All she said, cast lots, and viewed all there:

How Ruggiero freed, was lost once more,

And then transported to a foreign shore.

She saw him borne by that unbridled steed

Which his attempts to master it denied,

And how o’er a great space it flew at speed,

Upon a course both fearful and untried;

And how he now was well-nigh lost indeed,

To idleness, dance, play, feasts (all she spied),

Nor to his lordly realm now gave a thought,

His lady, nor the honour he had sought;

And that he’d waste the flower of his years

Consume his life, in endless inaction,

That chivalrous knight, first among his peers,

Losing body and mind to slow destruction;

And that sole part, outlasting joys and fears,

(That, when our frail form meets with corrosion,

Shall yet our life, from out the tomb, restore)

Be closed in tree or stone, on that far shore.

Canto VII: 42-45: But Melissa intercepts her with news of Ruggiero

But, the kind mage, who ever showed more care

For him than he himself had seemed to do,

Thought now by a harsh path, stony and bare,

To lead him on towards the heights of virtue,

Much like the doctors that no means do spare,

Blade, heat, or drug to render us as new,

Who, though at first, the body they offend,

Bring ease, and find us grateful, in the end.

She was not so indulgent as to seek,

Like the wizard Atlante, rendered blind

By excess of love, to grant to the weak

Life at all costs, for such was in his mind,

Prolong the knight’s existence, week by week,

Though little fame or honour he would find,

And let all praise be lost, in idling so,

Rather than one vain passing hour forego.

Twas he who’d sent him to Alcina’s isle,

There to forget all strife at her fair court,

And, as a lord of magic arts, likewise

So strong an enchantment he had wrought

It snared Alcina’s heart, and fixed her eyes

Upon that knight so firmly that, in short,

Though Nestor’s wealth of years he might see,

From such a love she never would win free.

Returning to the mage, who had foreseen

All that was yet to come, she took, I say,

A course to where the maiden might be seen

Lingering, woefully, beside the way.

Bradamante, who but mournful had been,

Soon felt fresh hope, and held her grief at bay,

As the heard the truth, now, from Melissa:

Her knight had been borne off to Alcina.

Canto VII: 46-50: The sorceress commits to rescuing Ruggiero

The warrior-maid was left in piteous state,

Half-dead, on hearing of his distant plight,

And, even more so, fearing for his fate,

If some swift cure failed to restore the knight.

Yet Melissa brought the salve; she needs but wait;

There was no lasting danger, for a sight

Of Ruggiero, she would win once more,

And that but in a few brief days, she swore.

‘Give me the ring’, she said, ‘that you possess,

For it is proof against the magic art;

If I should visit now that sorceress,

Who holds your love, I doubt not, for my part,

I’ll break the spell and, in a week or less,

Restore to you the one that holds your heart.

I’ll go this evening, long before the morn

And there, by India, shall greet the dawn.’

And then continued to explain the mode

Of operation that she would employ

To draw the knight from out that lax abode

Whose luxuries could never bring him joy,

And back to France. So, Bradamante showed

The ring, and gave it into her employ;

And more than that she would have given too,

Her heart, her life, his safety to pursue.

The ring she gave, her cause she commended,

Ruggiero’s more so, to Melissa;

Fair wishes to him, through her, she extended,

And took the road to Provence thereafter.

The enchantress, on whom she depended,

Swift departed for another quarter,

And a palfrey by her art did conjure,

But for one red foot, jet black all over.

Some Alichino, or Farfarello,

Drawn from the Inferno, in some wise,

Was that demon steed, while she did go

In barefoot, ungirt, and dishevelled guise.

She mounted, yet the ring did safely stow,

Lest it should mar the spell; then, through the skies,

Her palfrey swiftly flew and, ere the morn,

To Alcina’s island was she borne.

Canto VII: 51-55: She visits him, in the guise of Atlante the sorcerer

Her shape she wondrously transmuted

Adding a full palm’s length to her stature,

Increasing her limbs in size, as suited,

Until she felt she’d reached, in full measure,

Atlantes’ form, and might go, undisputed,

In place of that wizard, at her leisure,

Who’d reared the lad; a beard adorned her now,

Her hair all hoary, wrinkles on her brow.

Atlante’s face and speech she knew so well

She could imitate him most completely,

And, as the sorcerer, all doubts dispel;

And then she hid, and waited patiently,

Until the day came, and a chance befell,

To meet, Alcina absent, privately;

Rare chance indeed, for this Alcina so

Loved the knight, where’er he went she’d follow.

All alone she found him, as she wished,

As he was taking the fresh morning air,

Beside a stream that the hillside nourished,

Which flowed towards a clear lake, set there,

Hi soft and pleasant garments were finished

In a manner that love’s idle ways declare,

Wrought by Alcina’s hand, in silk and gold,

That of her spells and subtle magic told.

A fine string of richest gems was set

In a chain, that descended to his breast,

And round his once-manly arms were met

Twin bracelets, so adorning her fair guest;

Both ears were pierced, completing our vignette,

By rings of gold, designed to match the rest,

And from them hung two pearls, their quality

Unmatched in India or Araby.

His curling locks were moist with such perfume,

As owns the sweetest scent, and costs the most;

He soft and pleasing gestures did assume,

As, in Valencia, fond lovers boast;

Naught but unhealthy things in him found room,

Except his name, the rest corruption’s host;

Such he appeared, destined for damnation,

His former self changed, by incantation.

Canto VII: 56-64: She reproaches him for his loss of virtue

She observed him, in the form of that mage,

Whose semblance she’d adopted, then drew near,

Severe her aspect, venerable with age,

Which he was once accustomed to revere,

And with a most threatening look of rage,

That was wont in his pupil to plant fear,

Cried sternly: ‘Come, is this the fruit I gain

For all of my long labour, sweat, and pain?

The marrow of the lion and the bear,

Was the first food I fed you on, and I

Nurtured you, gladly, in my mountain lair,

A child that strangled snakes (I tell no lie)

De-clawed the tiger and the panther there,

And drew the wild boar’s tusks; then tell me why

After such disciplines, I find you later,

Mere Attis, or Adonis, to Alcina?

Is this what the stars I studied promised,

Those sacred entrails, and the flight of birds,

Omens, and auguries, and dreams, that fist

Full of lots, and all those learned words,

When from the milky breast you were dismissed,

All that proclaimed (since not by tending herds

Do men win fame) in arms you would appear,

And in your martial deeds would own no peer?

A fine beginning, one from which, sir knight,

One might surmise a Caesar would arise,

An Alexander, Scipio, outright!

Who alas, unless with their own two eyes

They saw it, could believe you ever might

Become Alcina’s slave, one to despise,

With, on your arms and round your neck, her chains,

By which she leads you, and her will maintains?

Oh, if true praise and honour move you not,

Or the deeds for which heaven destined you,

Why is your own posterity forgot?

Why scorn the victories that must ensue?

Why shun that womb the fates to you allot,

Set to conceive a line that shall pursue

True fame, a more than human progeny,

Brighter than the sun in its great glory?

Do not deny those noble souls their birth,

Formed in Eternal Mind, that now and then

Must take on mortal bodies on this Earth,

And so, arise from your sole root again.

Do not deny those laurels, marks of worth,

With which, after the damage and the pain,

Your heirs, their children, their successors

Shall deck Italy, restore her honours.

Not only should those many souls add weight

To your purpose; bright, and illustrious,

Matchless, sacred souls, the truly great

Flowers of your fertile line, sent among us,

But two of them alone should demonstrate

My claim: Alphonso, and the glorious

Ippolito, his brother; none their peer,

Wherever strength and virtue prosper here.

I spoke more of these than any other,

When I described your future line to you,

Because these two will acquire, together,

More of that virtue all good men pursue.

Thus, I gave more attention to either,

Than to the deeds of your other issue,

Seeing that you delighted in my speech

That of their glorious renown would teach.

What has she, whom you have made your queen,

More than a thousand courtesans possess,

That to a host a concubine has been?

And you well know the end of such excess.

And yet to better learn what goes unseen,

Unmask her magic, her deceitfulness,

Don this ring now, return then to her side,

And see what seeming beauty yet may hide.’

Canto VII: 65-67: Melissa returns to her true form

Ruggiero now gazed, mute and ashamed,

At the bare ground, and knew not what to say.

The mage, placing the ring that she had named

Upon his little finger, stepped away.

As Ruggiero his true being claimed,

Such deep remorse upon his heart did weigh,

He’d rather have been hidden from the eye;

There, a full thousand fathoms deep, to lie.

For once the ring he’d lifted to his lips,

In an instant, Melissa’s form he saw,

And old Atlante’s shape was in eclipse,

Since she required that same disguise no more,

Like that mask from her face the actor strips,

That played its part, and casts it to the floor.

Now swiftly her true purpose she revealed,

And how and why she’d met him, thus concealed;

That she was sent there by that lady who

Loved him ever, and for his presence pined,

To liberate him from his chains anew,

Those bonds of sorcery that did him bind.

And to inspire belief that this was true,

By Atlante of Carena’s form defined,

Had thus appeared; and, since he was restored,

The truth she told must not now be ignored.

Canto VII: 68-71: Ruggiero’s love for Alcina turns to loathing

‘The noble lady, she who loves you so,

And is of love right worthy on your side,

To whom you owe a debt, as you must know,

For the freedom in which you now abide,

Sends you the ring that magic art doth show,

And would have sent her heart, if deep inside

It owned a power that could match the ring’s,

That, nonetheless, your true salvation brings.’

And she went on to speak more of that love

Bradamante had borne him, and still bore,

While commending her worth, as if to prove

How truth and affection informed her lore,

All framed in a manner he would approve,

Shrewdly as any diplomat, and more,

Bringing such hatred upon Alcina

As we show towards the wicked ever,

Fuelling hatred of one he had adored;

Yet why should that seem so wondrous a thing,

Since from a charmed state he’d been restored,

His enchantment now dispelled by the ring.

The ring made clear, also, how false a chord

Her beauty had sounded, her form changing;

Naught there, from head to foot, had been her own;

All vanished now, its ruin hers alone.

As if, one morn, some lad had set aside

A ripe apple, forgetting where it lay,

And then returned to where it did reside,

By some chance and after many a day,

Wondering then to find it marred inside,

A thing of rottenness and foul decay,

And what before was dear, and greatly prized,

Now loathed and scorned, discarded and despised.

Canto VII: 72-75: He perceives her true form

So, Ruggiero now (to whom the ring

Given him by Mellissa had revealed

The fey’s true form, since that powerful thing

Made visible what magic spells concealed

And thwarted all enchantment) withdrawing

His love from one that to clear sight did yield,

Beheld an ugliness so great nowhere

Knew he of aught so withered or less fair.

Pale, wrinkled, lean was this Alcina’s face,

And sparse and white the hair upon her head,

Her height not six palms, nor a tooth in place,

For she was longer lived, to magic wed,

Than the Sibyl, that Cumae’s cave did grace,

Or ruined Hecuba, yet through a dread

Enchantment, to this present age unknown,

Had shown a youth and beauty not her own.

Beauty and youth she’d gained by her dark art,

Fooling Ruggiero among many,

But now the ring had torn the veil apart

That all those years had hidden, utterly,

The deeper truth; no wonder that his heart

Denied he’d ever loved her, nor did he

Now think to do so, shorn of her disguise,

And helpless now to charm him with her lies.

Yet he was advised, thus, by Melissa:

To employ his customary manner,

Until he could retrieve his steel armour,

Laid by, neglected and unused as ever.

And lest Alcina should suspect him, further

Feign that he wished to determine whether,

Since he’d not worn that armour for so long,

It fitted him, to whom it did belong.

Canto VII: 76-80: He escapes Alcina’s realm

Once so clad, he fastened Balisarda

(For so brave Ruggiero’s sword was named)

To his side, and grasped the shield with ardour

Which, dazzling the eyes, the vision maimed,

But seemed to strike the spirit yet harder,

As if the very breath of life it claimed.

This he now raised, and hung about his neck,

Wrapped in the silk, that held its power in check.

And then to the stables he passed swiftly,

Leading therefrom an Arabian steed,

(Melissa had so counselled, formerly,

Knowing it to be strong and sure indeed,

A horse as black as pitch, that o’er the sea

The whale had brought) and saw it met his need.

Swift as the breeze, twould bear him everywhere,

That sea-born breeze, now ruffling his hair.

The hippogriff he might have commandeered,

Which was housed beside the Arabian,

But the wise mage had said: ‘I am afeared

You lack the skill to master such a one.’

For she, the following day, it appeared,

Would steer the beast to a fresh location,

Where it might be trained, more easily,

To obey the rein in flight, or run free;

Nor if he refused to take the creature,

Would any suspect what he intended;

So, Ruggiero could do naught other,

For Melissa e’er her counsel extended.

Now, from that realm that all worth did smother,

And its withered fey, his way he wended,

Reaching, in time, a gate from which the road

Would lead to Logistilla’s fair abode.

Against its sentinels he charged, at will,

Riding towards them swiftly, sword in hand;

That one he chose to wound, and this to kill,

Then o’er the drawbridge, with his foes unmanned,

And Alcina unknowing of it still,

Ruggiero departed from her land.

In the next canto I’ll tell how he fared,

Ere to her sister’s palace he repaired.

The End of Canto VII of ‘Orlando Furioso’