Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto VI: The Enchanted Isle

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto VI: 1-6: It seems that Ariodante did not drown

- Canto VI: 7-12: He had determined to champion Ginevra’s cause

- Canto VI: 13-16: Ginevra and Ariodante wed, Dalinda becomes a nun

- Canto VI: 17-22: We now re-join Ruggiero who has reached a distant island

- Canto VI: 23-26: Ruggiero tethers his strange steed to a myrtle tree

- Canto VI: 27-32: The myrtle tree speaks to him

- Canto VI: 33-37: Astolfo, changed into the myrtle, tells his story

- Canto VI: 38-42: Alcina the enchantress deceives Astolfo

- Canto VI: 43-46: They are carried to the island on which Ruggiero has landed

- Canto VI: 47-53: Astolfo loses her love and is changed to a myrtle tree

- Canto VI: 54-58: Ruggiero finds himself in sight of Alcina’s castle

- Canto VI: 59-67: He is attacked by Alcina’s monstrous troops

- Canto VI: 68-70: But is rescued by two maidens riding unicorns

- Canto VI: 71-75: They lead him into Alcina’s domain

- Canto VI: 76-81: Of the giantess Eriphila who waylays travellers

Canto VI: 1-6: It seems that Ariodante did not drown

Foolish the wretch who thinks his hidden sin

Will remain a secret, and none will know,

When oft the ground that it lies buried in,

The air itself, his wickedness will show;

And God will often drive the soul within

To confess all, whether he wish or no,

Condemning himself, at no man’s behest,

To make his whole crime plainly manifest.

So, the wretched Polinesso had thought

To conceal his evil deed completely,

For the death of Dalinda he had sought,

Who knew, indeed, the whole sad history;

Yet in adding a second crime, in short,

Brought the fate upon himself more swiftly

He had sought to avert, and by his action

Ran but faster towards self-destruction,

Losing his friends, life, rank, and that honour,

The loss of which doth ever harm the most.

Now, as I said, the unknown warrior

Being at length persuaded by the host,

Doffed his helm, his visage to uncover.

And lo, a familiar face did boast;

For twas their Ariodante they saw,

Late lamented, yet alive once more;

Ariodante, wept for by Ginevra,

The king, the court, the people who all thought

Him long dead, and mourned, by his brother,

For his virtue, his bright valour when he fought.

It seemed to all then that the traveller

Had lied, for it was false, the news he’d brought.

And yet it was as true as truth could be

That he had seen him plunge into the sea!

But (as oft befalls in desperate plight,

When death, that was long desired, hovers near,

Yet now is dreaded; harsh the approaching night,

Its passage cruel, and painful, doth appear)

Ariodante, once lost to sight,

Repented of his action, and fought clear,

With strength and ardour, heading for the shore,

Rode the waves, and reached the land once more.

Despising now the folly that had led

Him to an action that but sought his end,

He took to the road, many a mile did tread,

And, cold and chilled, his weary way did wend

To a hermit’s cell, where, to silence wed,

Still to each rumour he an ear did lend,

Wishing to know if fair Ginevra grieved,

Or was indifferent, as he believed.

Canto VI: 7-12: He had determined to champion Ginevra’s cause

He learnt at first that from excess of pain,

She had nearly died, for through all the land

The rumour ran, and this all did maintain,

Such folk that heard of it, on every hand,

Countering all that he had seen quite plain,

Although in error he had been unmanned.

Then he heard how Lurciano had brought

A case against her, at her father’s court.

Then against his brother his anger burned

No less than his love waxed for Ginevra,

Thinking no such cruelty had she earned,

Though twas done in his support as ever.

Then, hearing that no brave champion yearned

To fight her cause, since none rallied to her,

(Believing Lurciano such a knight

As none dared to encounter in a fight,

And thinking him, also, so sincere,

So wise and possessed of such discretion,

That what he had claimed could but appear

The truth, all the facts in his possession,

Or he’d not have acted so; thus, in fear

Of wrongly supporting her transgression,

None would champion her) he now chose,

After much thought, his brother to oppose.

‘Alas!’ he cried, ‘I could not bear to hear

That she was put to death because of me;

My seeming death will do worse harm, I fear,

If hers precedes it, and none shows pity.

For she is my lady, my goddess here,

The light of my two eyes, howe’er it be.

I cannot but defend her, wrong or right,

And conquer in the field, or die outright.

If I support the wrong, then be it so,

And, if I die, then there’s some solace too,

(Except that, if I die, to death she’ll go,

Since, by failing, I’d condemn her anew.)

The comfort in my dying would but be

That, Polinesso’s love proving untrue,

She would clearly see how he’d deceived her,

Finding, thus, that he’d declined to aid her.

And then she’ll see one whom she did offend

Meet death, while thus supporting her defence;

My brother must take vengeance; I depend

Upon the fire of ardour in him, whence

His woe when he shall learn how, in the end,

His own harshness has despatched me hence,

He thinking to avenge the wronged lover,

Yet slaying, by that act, his own brother.’

Canto VI: 13-16: Ginevra and Ariodante wed, Dalinda becomes a nun

Concluding, in this way, his train of thought,

He donned new armour, mounting a fresh steed,

(Black his surcoat, and his black shield wrought

With green and yellow stripes.) A squire agreed

To bear his arms, of whom none there knew aught,

Who his master’s name concealed, as decreed.

Then all (as I have said) unknown, the knight

Set out to meet his brother, and to fight.

I’ve told you of what happened in the end.

And how he showed himself for all to see.

The king felt no less joy, I would contend,

At this than in his daughter winning free.

She thought never a lover could fate send

As true and faithful as he’d proved to be;

Who, after such injury moreover,

Had fought for her against his own brother.

The monarch, being naturally inclined

To cherish this knight, at the behest

Of Rinaldo, as all were of one mind,

The marriage with his loving daughter blessed.

Polinesso’s duchy, which was assigned

To the king once more with all the rest

Of his estate, in no happier hour

Could have been forfeit, forming thus her dower.

Rinaldo won mercy for Dalinda,

Who, despite the part she’d played was set free.

She, weary of the world, vowed however

To turn to God, forego her liberty,

For in Denmark, as a nun, she would ever

Live content, and there find sanctuary.

Yet Ruggiero, now, we seek once more,

Who, on the creature, through the sky doth soar.

Canto VI: 17-22: We now re-join Ruggiero who has reached a distant island

Well, that Ruggiero, of constant mind,

Never blanched at the onset of danger;

I’ll not believe a single leaf you’d find

Would tremble less, his heart firm as ever.

Yet Europe’s shores he’d now left far behind,

And travelled a great distance, moreover,

Beyond the pillars that great Hercules

Set as a mark for all that sail those seas.

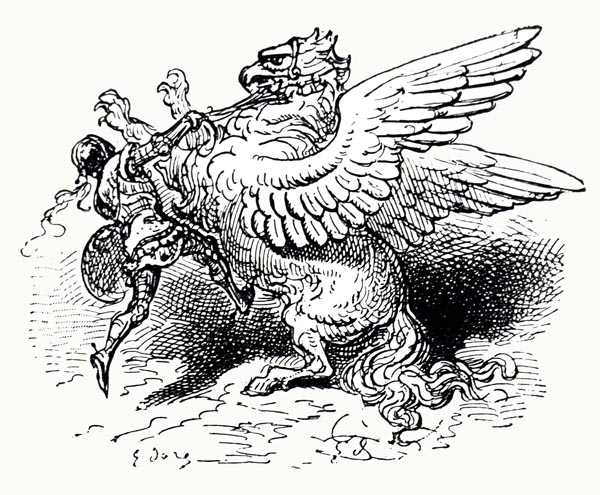

The hippogriff, that strange and mighty bird,

Carried the knight on such strong wings indeed,

It would have soon outmatched, its flanks unspurred,

Jove’s thunder-bearing eagle, in its speed;

There was no other creature, in a word,

That flew so high; no bird of any breed

Could equal its velocity, no bright

Flash of lightning e’er swifter in its flight.

When that creature had flown many a mile,

And without ever bending from its course,

Tired of the air, it wheeled above an isle;

And then descended; thus, the winged horse

Fell towards a place, both fair and fertile,

Like that, which fleeing from her love, perforce,

The virgin Arethusa did attain,

While hid beneath the waves, though all in vain.

Ruggiero no island could have found,

As sweet and pleasant, in that stretch of sea

O’er which his mount had flown, no finer ground

In all the world, where’er he chanced to be,

Than that on which, once it had circled round,

The winged steed now settled, silently;

What fertile plains, delightful hills are seen,

Clear streams, and shaded banks, amidst the green.

There flourished many a laurel bower,

Many a palm-tree, and pleasing myrtle,

Cedars, and orange-trees in fruit and flower,

Of various shapes and kinds, all beautiful;

From the burning heat, in a summer hour,

Yielding a shade, both deep and plentiful,

While safely, midst their boughs, the nightingale

Did, with its song, the secret glades regale.

Midst the red roses and white lilies there

Each of which delays the cool fresh breeze,

The rabbit roams, unhindered, and the hare,

While fine antlered stags Ruggiero sees,

Not fearful of some hunter’s dart or snare,

Grazing the grass, or resting, at their ease,

As hinds in herds, and flocks of goats, display

Their nimbleness on slopes above the bay.

Canto VI: 23-26: Ruggiero tethers his strange steed to a myrtle tree

When the hippogriff was close to the ground,

Such that to dismount involved least danger,

Ruggiero leapt, and his footing found,

Midst the verdant grass, on terra firma,

Yet gripped the reins, lest with a single bound

The creature that had brought him rose higher,

And tied them, twixt a laurel and a pine,

To a green myrtle, fast by the shoreline.

And there, where a spring arose close by,

Amidst the cedars, and the rich palm-trees,

He doffed his helm, and left his shield to lie,

Removed his gauntlets and, once more at ease,

Now gazing on the sea, and now on high,

He turned his face towards the cool fresh breeze,

That made the topmost heights of beech and fir,

With the most pleasant murmurs, gently stir;

Then bathed his lips in the clear fresh water,

And splashed his brow, gently, with his hand

So that the blood in his veins ran cooler,

Heated by his armour; his face he fanned.

And that he felt so warm was no wonder,

No ramble in the street, but far from land

Full three thousand miles had been his passage,

Bearing arms and armour on that voyage.

Meanwhile the creature tethered to the tree,

Beneath the thickest branches’ deepest shade,

Disturbed by I know not what, tried to flee,

Startled perchance by shadows in the glade,

Making the myrtle quiver, fitfully,

Till a heap of leaves at its feet it made,

Bending the myrtle almost to the ground,

And yet no means to free itself it found.

Canto VI: 27-32: The myrtle tree speaks to him

Just as a stick that’s placed upon the fire,

One which the pith within scarce fills complete,

Emits the air trapped in its midst, the pyre

Driving the vapour forth through its great heat,

Seething, bubbling like one that doth suspire,

And sounding, sighing doth the free air meet,

So, the offended myrtle, murmured, blind,

Then shrieking, moaning, split its outer rind

Thence came forth a sad and faltering voice,

Yet in clear and intelligible speech:

‘If in grace and courtesy you rejoice,

As your noble figure would seem to teach,

Let my release be now your kindly choice,

For my own ills into my depths so reach,

I need no other pain, no other woe,

From without, to plague and torment me so.’

At the first sound it gave, Ruggiero

Turned suddenly, and then gazed all around,

And when he found that living speech did flow

From the myrtle tree, whence came the sound,

He stood amazed, then to the steed did go,

Blushing with shame, and swift the reins unwound:

‘Human spirit, or goddess of this tree,

Whoe’er you are,’ he answered, ‘pardon me;

Not knowing such a spirit lay concealed

Beneath the roughened bark, I have done ill

To your living frame, the green leaves have peeled

From your fair branches, though against my will;

But, let your name, despite this, be revealed,

And say who lives within this matter still,

With both rational mind and speech, so may

The hail not mar you, nor the frost, I pray.

And if, in some manner, I may repair

This wrong, and be of benefit to you,

By that lady who hath my heart, I swear

To seek in word and deed, forever true,

To render aid, such as shall seem so fair

That you will praise all that I say and do.’

Thus, Ruggiero spoke, while the myrtle,

From head to foot did shiver and tremble.

Then drops of sap upon the bark appeared,

Like those which from a branch the fire will draw

When against some flaming pyre tis reared,

Too seared by far to be restored once more;

And then the voice its story volunteered:

‘Your courtesy I must not now ignore,

And I shall tell of who I was, and how

To myrtle I was changed, if you’ll allow.

Canto VI: 33-37: Astolfo, changed into the myrtle, tells his story

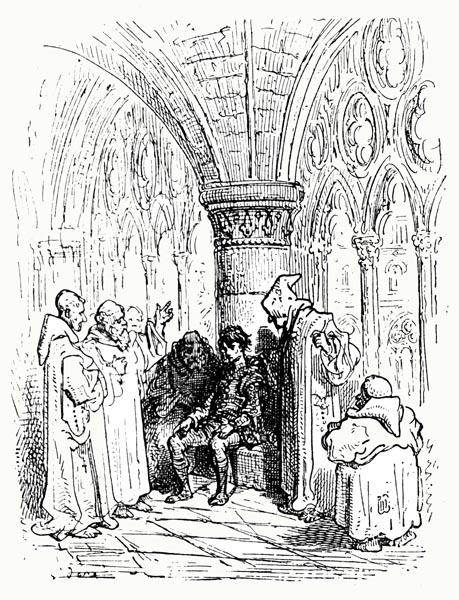

A French lord I was, by name Astolfo,

A paladin much feared in any fight,

Cousin to Rinaldo and Orlando,

Whose fame shall shine forever clear and bright;

And England’s realm, that my father Otho

Did rule, was after him my land, by right.

Handsome, I inspired more than one lady

To love; yet harmed, at last, myself solely.

Returning from far distant isles, I say,

Those that India’s seas lave on the east,

Where Rinaldo, and I, and others lay,

Held captive in a darkened cave, at least

Until Orlando came to save the day,

Whose valour saw its prisoners released,

Westwards I travelled along sandy shores,

That feel the southerlies without a pause.

There, as events and our ill fate decreed,

We came, one morn, upon a pleasant strand,

Where stood a castle, sited, close indeed

To the shore, and Alcina owned the land.

She had issued thence, to fulfil a need;

And all alone, lingering on the sand,

There, without net or hook, drew to her feet

All the fish that she sought for her retreat.

Dolphins hastened swiftly through the water,

With open mouths, the heavy tunnies came;

A sperm whale, like some ancient mariner

Roused from his idle sleep, docile and tame;

Salmon and bass, and sea-bream swam after,

And mullet, leaping, bathed in silvery flame,

Sea-serpents too, orcas, and baleen whales,

Reared their mighty backs and monstrous tails.

We saw a blue whale, the greatest ever

Yet encountered in any stretch of sea;

Eleven yards or more, its back moreover,

Rose from the waves, and, erroneously,

We thought (since he lay still in the water,

And was so vast from end to end) that he

Was some island that never moved at all,

Firm as a rock, and solid as a wall.

Canto VI: 38-42: Alcina the enchantress deceives Astolfo

Alcina made the whale approach the shore,

Simply by some magic incantation.

One mother this witch, and Morgana bore,

Yet perchance not of the same gestation.

That I was handsome, this Alcina saw,

Which wrought in her a pleasing sensation;

Such that she sought to part me, with deceit,

From my dear friends, achieving that complete.

She first received us with a cheerful face,

In a gracious and respectful manner,

And said: ‘Sir knight, if you are pleased to grace

My dwelling, I shall show you, hereafter,

All the creatures that I draw to this place,

All the many kinds of prey I gather,

(With pelts, or smooth, or scaly to the eye)

Far more than there are bright stars in the sky.

And if you’d hear a mermaid sing so sweetly

That with her music she can still the wave,

We’ll pass to another place, completely,

Where, at this hour, such often she doth crave.’

And she pointed out the whale, discreetly,

That semblance of an isle that waters lave.

I that was ever willing (to my own harm)

Mounted its back, while fearing no alarm.

Rinaldo signalled to me, and likewise,

Dudon gave a warning, yet all in vain,

The fey, Alcina, with her smiling eyes,

Left them behind, and the whale’s back did gain.

The creature, obedient, despite its size,

To its office, swam quickly o’er the main,

While I repented of my foolishness,

Too far from shore to ease my deep distress.

Mount Alban’s lord, Rinaldo, sought to aid

My plight, and well-nigh drowned in the sea,

For a furious southerly did the air invade,

Darkening the waves and sky, suddenly.

I know not what became of him; the maid,

Alcina, sought to soothe and solace me,

Yet, all that day and night of constant motion,

Detained me on that monster in mid-ocean.

Canto VI: 43-46: They are carried to the island on which Ruggiero has landed

Yet to this island we two came at last,

The greater part of it Alcina’s own,

Though taken from her sister, in times past,

Who’d held it, as her father’s heir, alone,

For she was his legally, in contrast

(So was I told, by one who long has known

The details, and his oath to me has sworn)

To her fey sisters, both of incest born.

Unlike those two, drenched in iniquity,

Practised in every vice and evil art,

She, who has ever lived in chastity,

Upon virtue has set her kindly heart.

Against her that pair, leagued in conspiracy,

Have more than once directed, for their part,

Mighty armies to drive her from the isle,

Seizing many a castle here, meanwhile.

Nor would she hold a single piece of land,

This Logistilla (such the lady’s name)

Were it not that the sea, and heights inland,

Bar easy passage to some further claim,

Just as they do twixt Scotland and England,

Where hills and river-mouths achieve the same.

Alcina and Morgana, tis confessed,

Will only cease when they possess the rest,

For they were bred to vice and wickedness,

And hate one who is both chaste and holy.

Yet let me once again my tale address,

And say how I was transformed but lately

Into green myrtle. Alcina did bless

Me with her favours, and loved me deeply,

Nor was I any the less amorous:

I found her beautiful and courteous.

Canto VI: 47-53: Astolfo loses her love and is changed to a myrtle tree

Clasped in her loving arms, it seemed to me

That I had found the source of all that’s good,

Which mortals gain in measures that vary,

Some less, and none too much, tis understood;

Nor did I think of France, my fair country,

Gazing upon that face whene’er I could;

In her lay all my hopes, while my desire,

Ending in her, to naught else did aspire.

And by her I was loved, as much or more;

Alcina cared not for any other,

Though she’d won many a heart before,

For me she left every other lover.

Day and night, I was her counsellor;

She served me, where she’d commanded ever;

She trusted me, and so with me conferred;

And, night or day, with none else spoke a word.

Ah, why do I disturb the wound again,

When I now lack the hope of any cure?

Why then recall those happy times, in pain,

Now cruel and bitter penance I endure?

When I had thought no greater love to gain,

Believing that she could not love me more,

She took from me the heart she had bestowed,

And every sign of some new love she showed.

Too late I understood her fickleness,

Loving and leaving, in but little space;

Two months I reigned, perchance a little less,

Ere a new lover had assumed my place.

She drove me away, my fair enchantress,

Disdaining one now banished from her grace;

Who, later, learned that a thousand others

She had treated thus, all her wronged lovers.

And lest we go about the world and tell

Of her faithless and lascivious ways,

She transmutes us; casting a magic spell,

Turns us to trees, to live, for all our days,

As pines, palms, olives, cedars, in some dell,

Or as this green myrtle, whereon you gaze;

Some as sad fountains, some as wild creatures;

In such manner she remakes our features.

Now you, sir knight, are come, by paths unknown,

To this fatal isle, thus one more lover,

Shall be transmuted to a wave or stone,

Or some such thing, as you shall discover;

You’ll win, from Alcina, sceptre and throne,

High above mere mortals, yet, my brother,

Soon you’ll be made to join our company,

As a wild creature, fountain, rock, or tree.

Willingly, I have given of my counsel,

Not that I think to benefit you so,

But tis better to possess the facts I tell,

Since something of her customs, then, you’ll know;

And since men’s talents differ, quite as well

As do their minds and faces, you may show

You have the knowledge (to repair this harm),

That many another lacked she did charm.’

Canto VI: 54-58: Ruggiero finds himself in sight of Alcina’s castle

Ruggiero, who had previously learned

Astolfo was cousin to his lady,

Fair Bradamante, grieved to find him turned

From his true form into this barren tree,

And, for love of her for whom he yearned,

(Could he but find a way to set him free)

Would do the knight a service, if he might

Whom he could only comfort, in his plight,

And solacing him thus, then demanded

If some passage led to that fair kingdom,

That realm Logistilla now commanded,

To which, by hill or valley, he might come,

Escaping, thus, Alcina’s, where he’d landed.

There was a way, the myrtle said, that some

Had gone, though harsh and stony, on the right,

By which a man might scale the mountain height.

And yet would not pursue that path for long,

Before he met a fierce and savage crew,

A company, both hard and passing strong,

That held the pass, and violence did pursue.

To Alcina, as her guard, these did belong,

Against all who sought to escape her view.

Ruggiero thanked the myrtle for his aid,

The gift of knowledge he had so conveyed.

He went towards the steed, which he untied,

Took the reins, and made it follow after,

Nor would he mount the beast and sit astride,

Lest it bear him now to some place other;

Musing on how, in safety, might be tried

The path to her realm, this Logistilla,

Firm in his purpose to do all he could

To escape Alcina’s power, and for good.

He thought again of mounting the creature,

And, on a fresh course, taking to the air,

But feared lest it might convey its rider

To a worse place, and thus he did not dare.

‘I may pass by force,’ he cried, ‘however,

I might fail there, and, so, end in despair,’

Such his vain thought, as, in a mile or two,

Alcina’s faery castle came in view.

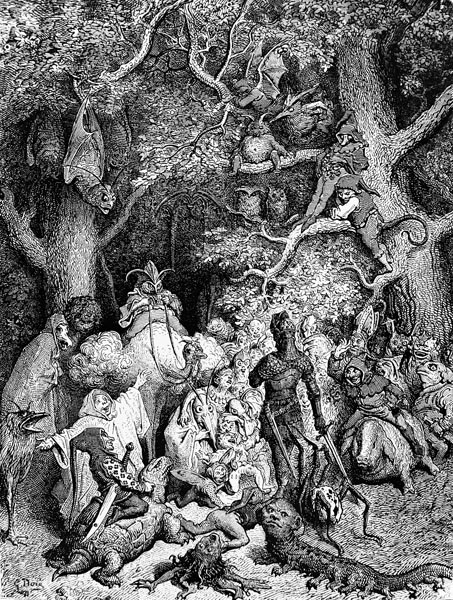

Canto VI: 59-67: He is attacked by Alcina’s monstrous troops

From a distance, he saw a towering wall,

Encircling that tract of open country,

Seeming to touch the sky, it was so tall,

From summit to foot, a thing of beauty.

It shone as if twas gold, some might say all

Its glittering was the work of alchemy.

Perchance such folk know better, and are right;

I say twas gold; it shone with golden light.

As he neared the city wall, now gleaming

Brighter than any other earth could show,

He left the road across the plain, deeming

That straight towards the gate its path must go,

And, on the right, he took a track, seeming

To be that safer route he might follow,

Yet soon he came against that wicked crew,

That must his passage bar, and did so, too.

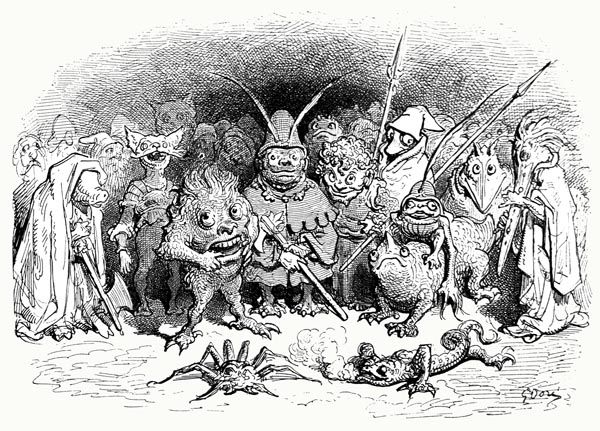

No stranger troop of folk was ever seen,

Monstrous in face, and hideous in shape,

Some with human bodies, though obscene,

Others in aspect like some cat or ape.

Some, goat-footed, trod the desert scene,

Others like centaurs thwarted all escape,

Some were old and stubborn, some young and bold,

These naked, those in pelts against the cold.

One galloped on a horse, without a rein,

Slowly others, on ass or ox, did go,

Or on a centaur’s back, or on a crane,

An eagle or an ostrich, mounted so.

As male or female some showed, some again

Were hermaphrodites, others there did blow

A horn, or drank, or bore a rope, a hook,

A sharpened file, or iron bar for luck.

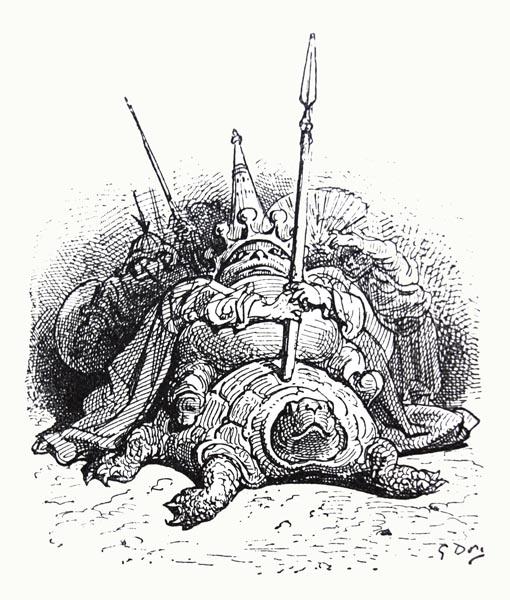

The captain of this crew then hove in sight,

Replete with monstrous paunch and bloated face,

He rode upon a tortoise, this brave knight;

It moved across the ground at snail’s pace.

And, now and then, arms held his form upright,

Since he was drunk, to keep his bulk in place;

Others wiped his chin and brow to ease him,

Others with their vestments gently fanned him.

And one, of human form up to his chest,

With hound’s neck though, above, and ears and head,

Bayed loudly, viewing this unwelcome guest,

That he should turn towards the keep instead.

‘No,’ Ruggiero cried, ‘nor shall I rest,

While I yet hold this, that shall see you dead!’

(Showing him the sword and, with due grace,

Pointing its gleaming tip towards his face).

The monstrous captain sought now to advance,

But Ruggiero sprang towards the foe.

He raised his sword, and that gross paunch did lance;

The blade he drove a hand’s breadth through or so.

Grasping his shield, he, to and fro, did dance,

Yet strong were his enemies, and harsh each blow.

Some grasped him from behind, and some before;

He stood his ground, and on that crew made war.

He cleft one member of that wicked host

To the teeth, and another to the chest,

Since none a helmet on his head did boast,

Nor bore a shield, nor was in armour dressed,

Yet, by sheer weight of numbers, they almost

Pierced his defences, he was so hard pressed.

Briareus, his every hand and arm,

Was needed there to keep that knight from harm.

If he’d but thought to show the magic shield

(I speak of that which, dazzling with its glow

Such that his every enemy must yield,

The wizard strapped beside his saddle-bow)

Then in a trice he might have cleared the field,

Blinding their eyes, and overcome the foe.

But such, perchance, the valiant despise,

Strength’s preferable to magic, in their eyes.

Canto VI: 68-70: But is rescued by two maidens riding unicorns

Be that as it may, better were he dead

Than be rendered captive by such a crew.

And yet, behold, from out the gate, instead,

That portal in that wall, of golden hue,

Two maids appeared, who both seemed nobly bred,

As witnessed by their clothes, and manner too;

Not raised, in truth, among the common herd,

But nurtured in some palace, in a word.

Each maid was seated on a unicorn;

Whiter than whitest ermine was each steed.

Both maids were lovely, and their garb was worn

In such a gracious fashion, rare indeed,

That he who looked upon them would have sworn,

Divine sight one, who viewed that pair, would need

To judge between those two, who did embody

Gracefulness on this side, and there, Beauty.

These lovely ladies rode into the field,

Where Ruggiero held his ground alone,

And each a kind hand to our knight did yield.

Like chaff, away the villains now were blown;

While he, with blushes scarce to be concealed,

Filled with shame, his thanks to them did own.

And then, content to wait upon his fate,

Returned with them, to pass the golden gate.

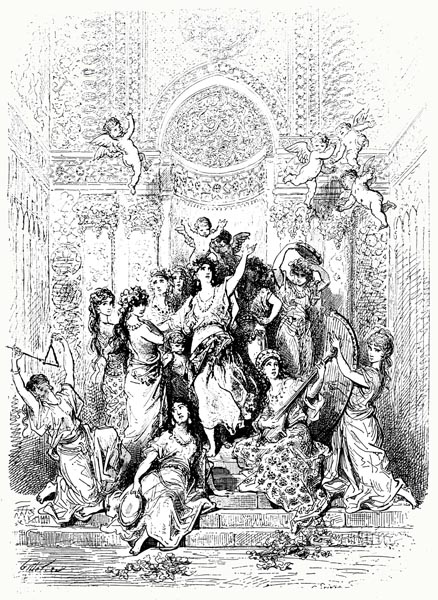

Canto VI: 71-75: They lead him into Alcina’s domain

The cornice, above that pleasant gateway,

Projecting some distance from the wall,

Gleamed everywhere, rich gems it did display,

Rare jewels from the East spread over all.

And each corner there did gently weigh

Upon a diamond column, pure withal;

And whether twas true or false, no fairer

Or more pleasing a gate was viewed ever.

In and out the pillars, and o’er the sill,

Ran wanton maidens laughing, mockingly,

Who might yet have appeared more lovely still,

Had they shown the manners of a lady.

And all were dressed in green, as maidens will,

There hair crowned with fresh garlands, prettily,

And they with glance and gesture did entice

Ruggiero within their Paradise.

For, with good cause, I may so name that place,

Where I believe that Love himself was born,

And where they danced and played, with joyous face;

Where every hour was festive, none forlorn.

There old grey-headed Thought could find no space

In any mind to dwell; there none need mourn;

Nor poverty nor distress could enter where;

Plenty her cornucopia did share.

Where, with fair brow, unclouded and serene,

Graceful April wore a changeless smile,

Lads and maidens passed; one, by the green

Margin of a spring, sang so sweet, the while

These in the shade, those on the slopes were seen,

Dancing, playing, the bright hours to beguile;

And there, one whispered, in a trusted ear,

His plaint of love, that no one else might hear.

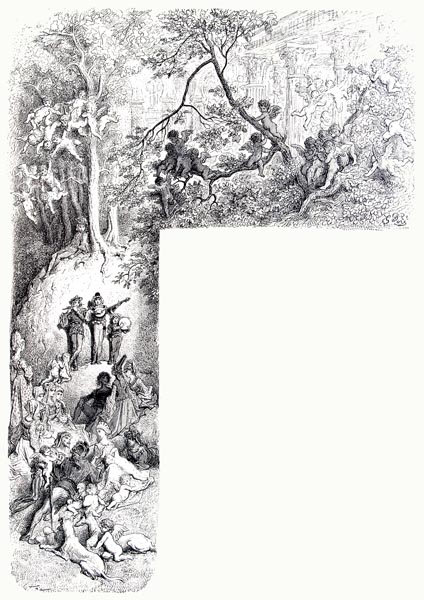

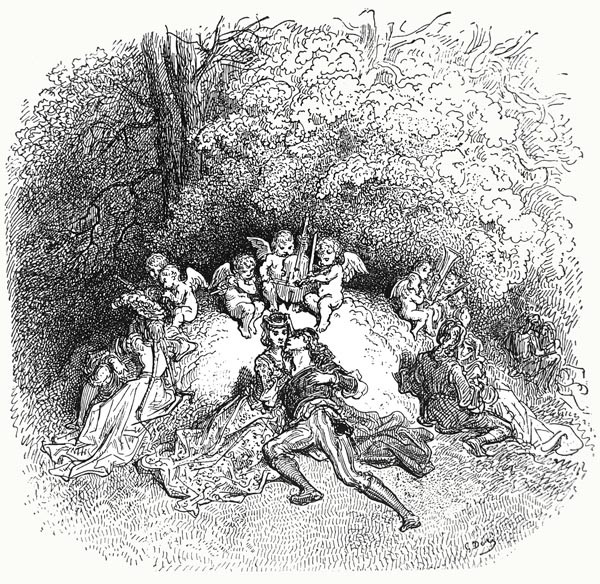

Through the laurel branches, round the pine,

The lofty beech-tree, and the shaggy fir,

Flew Love’s cherubs; none there did repine.

These hailed their latest conquest, him or her,

Those with some loving heart did darts align,

While others spread their hidden snares ever;

One tempered arrow-tips in the stream’s flow,

Which others whetted on the stones below.

Canto VI: 76-81: Of the giantess Eriphila who waylays travellers

To Ruggiero a fine steed was brought,

Strong and lively, of a sorrel colour,

Richly-caparisoned, for every sort

Of jewel the gilded cloth did cover.

And of the hippogriff they’d also thought

(The wizard alone had tamed that creature,

A mount indeed of a different kind);

A young man led it slowly on behind.

The two kindly maidens who’d defended

Ruggiero from the crowd in that affray,

From the crew, that is, who had descended,

Upon him when he took the right-hand way,

Said: ‘Sir knight, your virtue, all your splendid

Deeds, known to us, are such we feel we may,

Emboldened by that knowledge, seek your aid

In what would ease our hearts, if twere essayed.

Soon we shall reach a dale that splits the plain,

Into its separate parts; a giantess

Guards the bridge there, thwarting, to her gain,

Those who seek passage, and our great distress;

Eriphila she’s called, this source of pain,

Who cheats, and robs, and harms us to excess,

Long fangs she has that will the traveller tear,

And with sharp talons claws them, like a bear.

Moreover, she infests the public highway,

Which all were free to travel but for her,

She roams the park, and causes disarray,

And know that of that crowd who, earlier,

Attacked you on the path, and blocked your way,

Many are the sons of that vile mother,

And are her followers, as impious,

And inhospitable, and rapacious.’

‘Not one but a hundred such I would fight,

On your behalf,’ replied Ruggiero,

‘Dispose of my person then, as you see right,

So that we may remove the source of woe.

The reason that I’m clad in armour bright,

Is not because I would gain silver so,

Nor land, but to bring aid where it is due;

Above all, to fair maidens such as you.’

Their grateful thanks those ladies now bestowed

On one so worthy of them, as was he,

And, talking thus, as they went down the road

The bridge and giantess they soon did see.

In golden armour, she the path bestrode,

Emeralds and sapphires decked her richly;

But I’ll defer to the seventh canto

Her encounter with brave Ruggiero.

The End of Canto VI of ‘Orlando Furioso’