Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto IV: Bradamante and Ruggiero

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto IV: 1-4: Bradamante beholds the winged steed and its master

- Canto IV: 5-10: She sets out with Brunello to seek the sorcerer’s castle

- Canto IV: 11-15: She seizes his ring and issues a challenge to the sorcerer

- Canto IV: 16-21: They fight and the sorcerer unveils his shield

- Canto IV: 22-26: Bradamante overcomes his magic

- Canto IV: 27-36: Atlante, the sorcerer, yields her an explanation

- Canto IV: 37-41: Bradamante frees Ruggiero and the other captives

- Canto IV: 42-46: Ruggiero, unwisely, takes to the air, astride the hippogriff

- Canto IV: 47-50: The hippogriff bears Ruggerio towards the west

- Canto IV: 51-53: We return to Rinaldo, who has reached Scotland

- Canto IV: 54-62: He hears of the plight of Ginevra, a king’s daughter

- Canto IV: 63-67: Rinaldo decides to champion the lady

- Canto IV: 68-72: Rinaldo rescues a maiden

Canto IV: 1-4: Bradamante beholds the winged steed and its master

Though dissimulation often conceals

The inner workings of an evil mind,

Many a time some good it yet reveals,

And many a benefit therein we find,

Saving us from harm in life’s ordeals;

For those we meet with are not always kind,

In this our life, more clouded than serene,

Where envy bears many an ill, unseen.

If, in our bitter trials, we scarcely meet

With one true friend to whom we can display

Our secret thoughts, communicate, complete,

All we believe in, and not go astray,

Should Ruggiero’s friend be less discrete,

When dealing with Brunello; one, I say,

Who was as insincere, and false, and tainted,

As by the wise Melissa he’d been painted?

So, she dissimulated, twas fitting,

With one who was a master of the lie,

And held her position, ever glancing

At those rapacious hands that met her eye,

When, behold, a mighty noise, arising,

Filled their ears, as if from out the sky.

‘O Virgin Maid! O King, above!’ she cried,

And quickly ran to seek its source outside.

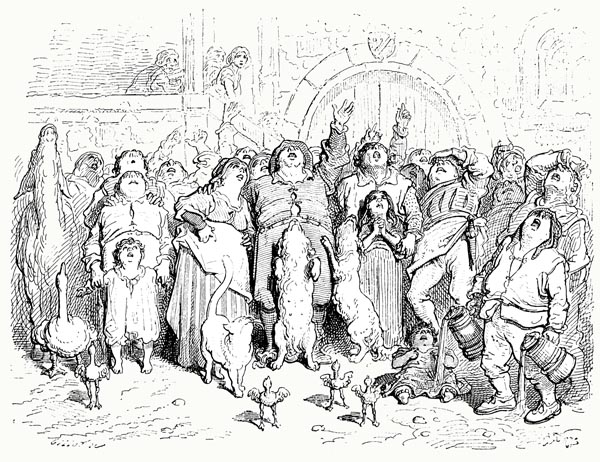

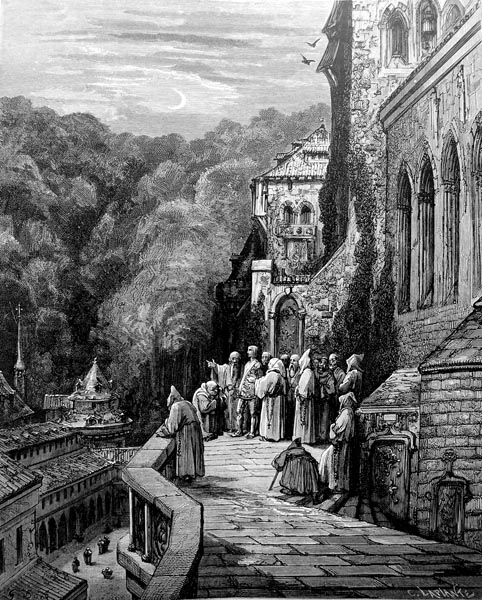

She saw the host and his family there,

Folk at the windows, folk out in the lane,

All gazing upwards at the heavens bare,

As if a comet or eclipse showed plain;

There flew a wondrous thing, high in the air,

She scarcely credited, nor could explain,

A winged steed, gliding, in clear daylight,

Across the sky, bearing an armoured knight.

Canto IV: 5-10: She sets out with Brunello to seek the sorcerer’s castle

Broad, and of varied colours, was each wing,

And in the midst that figure shining bright,

Since his steel breastplate, a radiant thing,

Lit all around it; westward was his flight.

Yet the creature, now, did downward spring,

And midst the mountains there, was lost to sight.

This path, the host said, the sorcerer flew,

In raiding near and far, and he spoke true.

‘Sometimes he flies straight upwards to the sky,

Then sometimes seems to skim along the ground.

He bears away those pleasant to the eye,

From all the distant countryside around,

So those who are, or think they are, all sigh,

(Though he in fact will steal what he has found)

And so, the maids are careful not to stray,

But hide their features from the light of day.

A keep, in the Pyrenees, forms his lair,

Built on high, by spells and incantation,

All made of steel, and it shines bright and fair,

The whole world shows no finer creation;

And many a brave knight has ventured there,

Yet none return from that destination,

For I fear,’ the host said, ‘naught do they gain,

But they are all imprisoned there, or slain.’

The warrior-maid thought on all he’d said,

Rejoicing, while believing that she would,

Without a doubt, strike the sorcerer dead,

Wielding the ring, and end his theft for good.

‘Find me a bold guide, host, to ride ahead,’

She cried, ‘who knows the way, by vale and wood;

For I must not delay, my heart beats so,

But find this enchanter, and destroy our foe.’

‘You shall not lack a guide; with you I’ll go.

I have the path, writ here, and then a thing

That may well aid us both,’ cried Brunello,

‘As we ride on our way.’ He meant the ring,

But then he said no more, nor made a show

Of aught, lest that some penalty should bring.

‘Twould please me, if you did so,’ she replied;

Wishing to make the ring hers, thus, she lied.

She said but what she needed to, no more,

Concealing what might help the Saracen

To do her harm. At cock-crow, to the door

The host brought their two steeds, and once again

As dawn light filled the sky from hill to shore,

And promised a fine day, dwarf and maiden

Went their way, the sorcerer’s keep to find,

Brunello now before her, now behind.

Canto IV: 11-15: She seizes his ring and issues a challenge to the sorcerer

From wood to wood they rode, and hill to hill,

Until they reached a Pyrenean height

From which both France and Spain the view will fill,

If the air is clear, and the day is bright,

As from the Apennines, those same eyes will

Have both the Adriatic’s shores in sight,

From Camaldoli say; then, painfully,

And slowly, descended to a valley.

There, in its midst, a hill rose to the sky

Its summit circled by a wall of steel,

And towering, in its majesty, so high

That all the hills behind it did conceal,

And none could reach its top that could not fly,

And little to bring hope would that reveal.

‘Behold,’ Brunello cried, ‘the wizard there,

Both men and women prisons in his lair!’

Sheer on all four sides, the mountain gleamed,

As if smoothed with a file, by day and night,

Nor was there any path or stair it seemed,

Whereby a living soul might climb the height.

Built for a winged creature, such they deemed

That nest and lair, where naught else could alight.

And this, the warrior-maid knew, was the hour

To seize the ring; the dwarf was in her power.

And yet she felt it wrong to wet her sword

With the blood of one unarmed, though vile,

For she might well obtain the ring, assured

Of overcoming him, with strength and guile.

So, the dwarf suspecting naught untoward,

She seized him, and then bound him fast the while,

To a tall fir-tree, where he might linger,

While taking the ring first, from his finger.

Nor did a single groan, lament, or tear,

Brunello now brought forth, disturb the maid.

For she descended, filled with hope and fear,

To that small space within the tower’s shade,

At a snail’s pace, and then as she drew near,

Upon her horn she blew, and so conveyed

Her intent, to the mage above, outright;

With a loud cry, summoning him to fight.

Canto IV: 16-21: They fight and the sorcerer unveils his shield

The enchanter waited not but, swiftly,

He issued from the gate, at her loud cry;

The winged creature bore him, steadily

Towards her, plunging earthwards from on high.

Ferocious the armed knight seemed to be,

And yet the maid was comforted thereby,

For he appeared to lack a lance or sword,

Or aught else that might some harm afford.

He bore naught but a shield, on his left arm,

A scarlet cover hiding it from view;

He held a book in his right hand; a charm

He read aloud, to conjure wonders new.

And, now, a phantom lance caused her alarm,

While he scarce raised an eyelid; now, there flew

A club or mace that kept the maid at bay,

Without his touch, who glided far away.

It was not formed by magic, his fell steed,

But born of a mare, quite naturally,

Though fathered by a griffin and, indeed,

Was winged as was its sire, quite splendidly.

While the forelegs, beak and crest agreed

With that creature, though all else, equally,

Conformed to the mother; such are found

Midst Riphaean hills, northern, and ice-bound.

This ‘hippogriff’ he lured by incantation

From its far land, and waited not, but sought

To tame it and, with constant dedication

To the task, soon all he wished he wrought;

And in a month nigh made it his creation,

Such that it mastered every move he taught.

And then on earth, or through the air, he rode;

All else magic, but that which he bestrode.

Though magic could indeed change its colour,

Making its hide seem yellow now, or red;

The maiden was undeceived however,

For the wearer of the ring, was not misled.

Yet all her blows but empty air did sever,

As here and there she rode, in fear and dread,

Labouring and striving, struggling there,

To demonstrate her skills in that affair.

And when she’d exercised herself awhile

On horseback, she leapt, neatly, to the ground,

In order better to achieve, by guile,

Melissa’s tactics, ever wise and sound.

The mage to work his final spell, meanwhile

Not knowing of the ring, at last unbound

His shield and, sure of blinding all below,

Swooped, and veiled her in its baleful glow.

Canto IV: 22-26: Bradamante overcomes his magic

He might well have shown his shield from the start,

Not needing, then, to keep the maid at bay,

But liked to see brave knights display their art,

A lance thrust, or a good sharp sword at play,

As the cat prefers the mouse to act its part,

And toys with it, in a mischievous way,

Then grows bored and bites it, by and by,

And, in the end, determines it should die.

The mage, in this, I liken to the cat,

The maiden to the mouse, each had their role,

But then my simile falls somewhat flat,

For with the ring the maiden sought her goal,

Intent upon the task that she was at,

Of fighting him, while staying sound and whole;

So, when she saw the naked shield appear,

She closed her eyes, and fell, as if in fear.

Not because the light from it could harm her,

As it had others who had met its glare,

But that, despite himself, the sorcerer

Might now descend, and to the earth repair.

Nor was she wrong in all she did infer,

No sooner did she fall than, in the air,

The sorcerer turned his strange steed around,

Which, landing swiftly, settled on the ground.

Leaving the shield, which he’d already veiled,

Hanging from his saddle-bow, he went

To seek the warrior-maid who had availed

Herself of cover, like a wolf content

To wait in ambush for the prey she’s trailed.

Then the maid leapt forth, with fierce intent,

To seize the wretch, whose book fell from his hand,

His magic spells no more at his command.

He ran towards her, with a chain he bore

Around his waist, believing he could bind

The warrior, since he’d done the like before;

At least that was the purpose in his mind.

But she threw him, expertly, to the floor;

Although, for this, a fair excuse I find,

The old man’s strength appearing none too great,

When matched against the maid I celebrate.

Canto IV: 27-36: Atlante, the sorcerer, yields her an explanation

Victorious, the maiden raised her sword,

Intending to remove the wizard’s head,

And yet, as if base vengeance she abhorred,

Now showed the sorcerer mercy instead;

The visage that she viewed, to age inured,

Was but a face of woe, and filled with dread;

Its wrinkles, the white hair above, did show

His age as three score years and ten, or so.

‘For God’s sake, slay me, youth!’ the wizard cried,

Revealing ire, and spite, and bitterness,

Yet she was as keen to see his wish denied

As he to end his life; she longed, no less,

To know why a sorcerer would decide

To build a fortress, midst the wilderness,

And who he might be, that had built so high,

And wrought such outrage on the lands nearby.

‘Yet not through some malign intent, alas,’

The aged wizard answered, in his woe,

‘Did I create, upon this solid mass

Of rock that soars above the vale below,

A keep, of which I am the lord, and pass

For a thief, but to save, by doing so,

A beloved knight who, fate prophesies,

Else through treason, as a Christian, dies.

For none, between the Poles, has ever seen

A youth that is so handsome, or so fine,

Ruggiero by name, and I have been

His tutor since a child, his care was mine;

I am Atlante. Love of fame, I ween,

And how the stars within his chart align,

Led him to France in service of his king,

Yet I to him another fate would bring.

I only built the mighty fortress here

To hold Ruggiero most securely,

Who was then captured by me as, I fear,

I’ve failed to capture you, and, equally,

Fair ladies, and many a man his peer,

I seized, also, to bear him company,

So that if freedom ever proved his wish,

Sweet friendship might such desires extinguish.

So long as he and they seek not to leave,

I grant them every other pleasure there;

Whatsoever in this world they believe

They might like, I obtain or I prepare;

Whatever hearts long for, and minds conceive,

Such songs, games, dance, dress, food my captives share.

The seed well sown, a rich crop it would yield,

And yet you venture here, and win the field.

Oh, if your heart is lovely as your face,

Do not reject this, my sincere counsel:

Come, take the shield, I yield it you with grace,

And then, the creature shall be yours as well.

Leave all within my castle still in place,

Or take a friend or two, that therein dwell,

Or take all who are there, I’ll not say no,

As long as you leave me Ruggerio.

Or if you choose to take him from the tower,

And he in France must, by your wish, remain,

Be pleased to free my soul, this very hour,

From this vile body that brings naught but pain!’

‘You’ll see him freed, for such is in my power,’

The maid replied, ‘though loudly you complain.

Deign not to offer me your shield and steed;

All that was yours, now mine, you here concede.

Nor if all here were yours to take or give,

Would the thing be fitting; it seems to me.

You say you prison him that he might live,

And thus escape his ill-starred destiny,

Yet that you cannot know, nor heaven’s sieve

May comprehend, nor alter what shall be;

For since you failed to prophesy your fall,

Far less another’s fate shall you forestall.

Pray not to me for death, for your prayer

Will prove in vain; but if such you desire

Though all the world should seek your life to spare,

Strong souls win that to which they may aspire.

Yet, ere your spirit leaves your flesh, prepare

To free your prisoners, void your keep entire.’

So spoke the warrior, and drove him on

Towards the high mount, and the keep thereon.

Canto IV: 37-41: Bradamante frees Ruggiero and the other captives

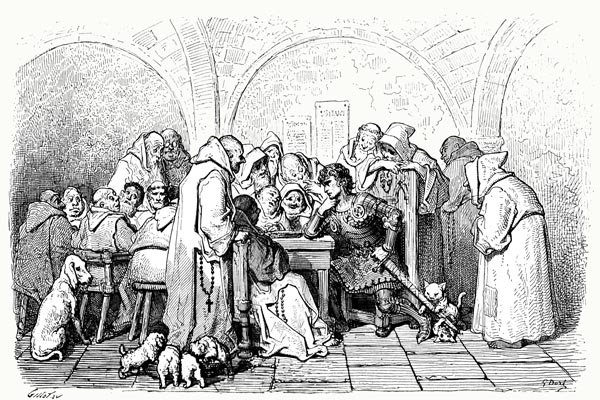

Bound with his own chain, the enchanter,

Atlante, went before, the maid behind.

She scarcely trusted him, though his manner

Seemed much subdued to her cautious mind.

They’d gone but a few paces, together,

Before they came upon a stair that twined,

Incised within the rock, about that same,

And climbed till to the castle gate they came.

Atlante, at the threshold, raised a stone,

Engraved with arcane characters and signs,

And vessels lay beneath, to sight unknown;

Eternal fires burned, deep in their confines.

These the wizard shattered; all was flown,

The castle gone, bare the mount’s outlines,

Now, empty slopes were all that met the eye,

As if no keep had towered beneath that sky.

The mage had suddenly escaped the maid.

He fled, a thrush from out the fowler’s snare,

Freeing the knights and ladies he’d conveyed

To their prison, now vanished in thin air.

Bereft of their fine lodgings, they surveyed

The deserted summit, and could but stare,

And many there were grieved, in full measure,

That freedom had robbed them of their pleasure.

There stood Gradasso, there Sacripante,

There too was the noble knight, Prasildo,

Who’d accompanied Rinaldo, on his way

From the Levant, and his friend, Iroldo.

And now, at last, the fair Bradamante,

Has found her beloved Ruggiero,

Who when he saw that it was her, truly,

Welcomed her, and thanked her most profusely.

He greeted her, whom, more than his own eyes,

More than his heart, far more than his own life,

He’d loved since she, though in martial guise,

Doffing her helm, was wounded in the strife;

Of which I could relate more and, likewise,

How they then searched, confusion being rife,

Midst the wood for each other, day and night;

While destined not till now to reunite.

Canto IV: 42-46: Ruggiero, unwisely, takes to the air, astride the hippogriff

Once they had spoken, and he understood

That she alone had free him from his gaol,

His felt great joyfulness, as well he should,

And hailed his own good fortune. To the dale,

From the mount, they descended, till they stood

Where the maiden had laboured to prevail,

And where the sorcerer was made to yield.

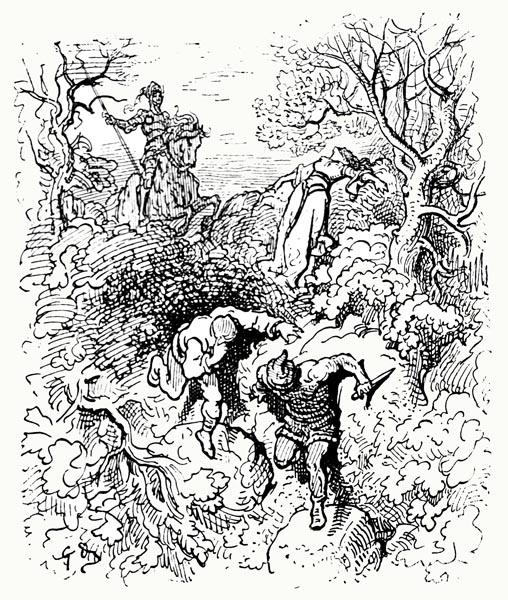

She saw the hippogriff still bore the shield.

The maiden went to seize it by the rein,

The creature stood stock still, till she was nigh,

And then it spread its wings, and flew again,

Settling upon the slope, though not too high.

She followed, and the same thing did obtain,

It flew some way, then dropped to earth nearby.

Much as a crow behaves, on sandy ground,

Teasing a dog, leading it round and round.

Gradasso, Ruggiero, with the king,

Sacripante, and the rest, watched its flight,

Now here, now there, quietly pursuing,

Hoping it might turn back, and then alight.

Yet, the creature, its same ploy renewing,

Left them, one by one, on some rocky height,

Or deep in some moist and stony hollow;

But dropped beside the last, Ruggiero.

This, Atlante the mage had brought to be,

Whose deepest wish was ever as before,

To thwart young Ruggerio’s destiny;

This was his only thought and care, therefore

He’d sent the hippogriff to, suddenly,

Bear him from Europe to a distant shore.

Ruggiero seized its bridle, but, lo,

The winged creature refused to follow.

Ruggiero, dismounting from his steed,

(Frontino was the lively charger’s name)

Now sprang onto that mount of different breed,

And with his spurs dug deep into the same.

Its proud heart stirred, it moved now, for, indeed,

Bearing the youth aloft was its true aim,

Then, swifter than a falcon, soared away,

Whose lord unhoods it, and points out the prey.

Canto IV: 47-50: The hippogriff bears Ruggerio towards the west

Bradamante, seeing them rise on high,

And her Ruggiero in such danger,

Stood mazed, astounded, peering at the sky,

And needed sundry moments to recover,

For he was not the first such youth to fly;

She knew of Ganymede, whom Jupiter

Had seized, and feared lest her Ruggiero

No less fair and noble, were treated so.

She kept the flying creature in her sight,

Her gaze fixed on them, till they disappeared

Where eyes, unable to pursue their flight,

Must leave the heart to follow, all afeared;

Though all her tears and sighs for her lost knight,

Would bring but little comfort it appeared.

With Ruggiero vanished from her view,

Her eyes fell on his warhorse, whom she knew.

Not wishing to abandon poor Frontino,

That rich prey, to some random passer-by,

She decided to take him with her, so

As to keep him for her love, lost on high.

Meanwhile the hippogriff, with Ruggiero,

Unable to return, soared through the sky,

While the valleys and mountains passed below,

Their heights and depths one flat and even flow.

When the steed had reached a point, high above,

Where it dwindled to a dot in the sky,

Towards the west, it then began to move,

Where the sun, in Cancer, set; it could fly,

Through the air, like a vessel set to prove

Its speed, whene’er propitious breezes sigh.

But we must leave the steed, and Ruggiero,

And turn our thoughts, at once, to Rinaldo.

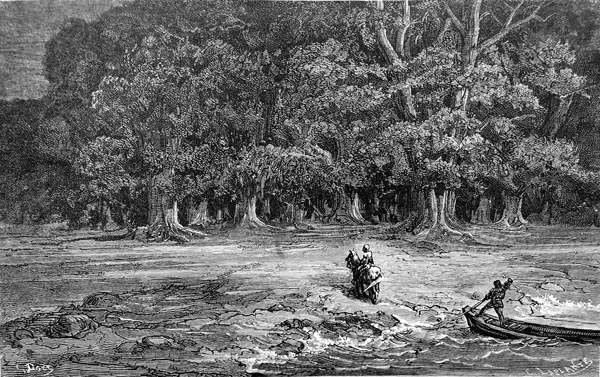

Canto IV: 51-53: We return to Rinaldo, who has reached Scotland

Rinaldo had been driven, day after day,

Before the gale, over wide breadths of sea;

Swiftly towards the north, and then away

Beneath the western sky, blown, equally;

Till Scotland’s shores, at last, were on display,

That Caledonian Forest, where he

Might hear within the stands of ancient oak,

Bold knights duelling, sounding stroke on stroke.

For many a knight-errant wandered there;

Those famous throughout Britain one might see;

From near and far, came those that arms did bear,

From France, from Norway, and from Germany.

None lacking valour its dark depths would dare;

Those seeking honour, found death frequently.

There did Lancelot, and Tristan, glory gain,

Sir Galahad, King Arthur, Lord Gawain,

Knights of The Round Table, old or new;

More than one monument, finely wrought,

Proof of their valiant deeds, all might view.

Next Bayard, and his arms, Rinaldo sought,

For he, on shore, his aim would now pursue,

Telling the vessel’s master that had brought

Him there, to sail south, then await his need,

In the harbour, at Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Canto IV: 54-62: He hears of the plight of Ginevra, a king’s daughter

Devoid of squire, or other company,

Through that vast, ancient forest rode the knight,

Choosing now this, now that, path; constantly,

Hoping for some fair quest that might delight.

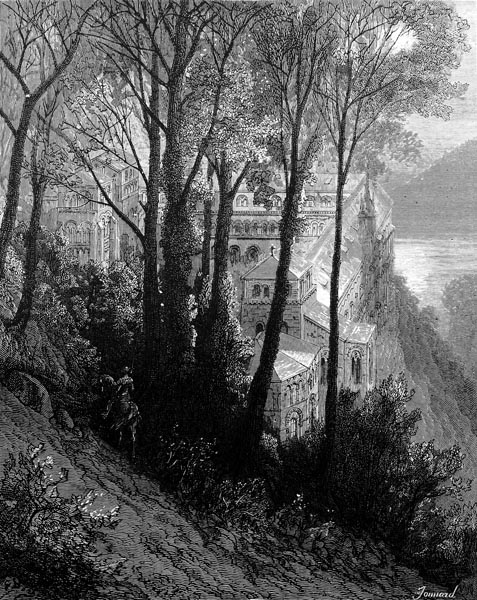

He headed that first day for an abbey

Where any that passed by might spend the night,

For a good deal of its wealth thus was spent,

In lodging those upon adventure bent.

The abbot and the monks gave him good cheer,

And welcomed him; of them he sought to know,

(Though not before he’d doffed his martial gear,

And filled his stomach, from a plate or so)

Whether some brave adventure might appear

From which a host of valiant deeds might flow,

Whereby a man might prove whether merit

Or blame was his lot, and thus might profit.

They replied that wandering in the forest

With many a strange adventure he’d meet,

But, there, action won small fame, they confessed,

Since the place was as obscure as their retreat.

‘Seek,’ they said, ‘to go where you’ll be blessed

Your deeds not buried underneath your feet,

Where, after all the weariness and pain,

Glory will follow, and your name remain.

And if you would seek to prove your valour,

Prepare to hear of a quest as worthy

As any that brought a brave knight honour

In this age, or in some past century.

In need of aid is our king’s fair daughter,

Who must defend herself, continually,

Against a baron, called Lurciano,

Who’d mar her name, and would destroy her so.

For he has denounced her to her father,

(Without good reason, more, indeed, from spite)

And claims that he saw her lead her lover

To her own chamber, in the dead of night.

And death by fire is her fate, moreover,

According to our law, unless some knight,

Within this month, will be her champion,

And prove the baron lies, ere it be done.

Scotland’s harsh laws, impious and severe,

State that a lady, of high rank or low,

Who lies with any but her husband here,

If she is but accused, to death must go.

Nor is there remedy should none appear

Who’ll champion her cause, and strike a blow,

And act as her defence, and so maintain

Her innocence, and thus remove her bane.

Grieving for his daughter then, our king,

(Ginevra is the guiltless lady’s name)

In town and city, has proclaimed the thing,

And that if one would champion that same,

Counter the case the baron seeks to bring,

(If he but of some fair lineage came)

She would be wed to him, with a dowry,

Of which so noble a maid is worthy.

But if no knight demands to fight for her,

Or does, but fails to conquer, then she dies.

Such seems for you a more fitting venture

Than wandering the forest and, likewise,

There’s the fame you’d win and the honour,

That would be yours for ever, and the prize,

The fairest flower of maids of tender years,

That twixt India and Atlas’ mount appears;

And riches would be yours, a realm indeed,

So, you might live content for all your days;

And the king’s favour, if by your brave deed

His honour is increased – dim glow its rays;

Then, by the laws of chivalry, at need,

You’re obliged to champion such always;

Since, she is, by common opinion,

Of modesty, in truth, the paragon.’

Canto IV: 63-67: Rinaldo decides to champion the lady

Rinaldo thought a while, and then replied:

‘Maidens must perish then because they choose

To embrace their love and in one confide

Whose very passion does the deed excuse!

Accursed are the laws by which she’s tried

And cursed be he who seeks so to abuse

Such a maid. Slay, rather, her accuser,

Than one who grants new life to her lover.

Whether the tale that’s told be false or true,

I care not; if she has so blessed her love,

Although, indeed, tis brought to public view,

Yet such an action I must still approve.

My every thought’s bent upon her rescue;

Grant me a guide, and I shall swift remove

To where’er her accuser now doth stand,

And, trust to God, I’ll counter his demand.

I may not claim she did not do the deed,

Lest I, unwittingly, proclaim a lie;

I simply say, whatever be your creed,

No reason can I see why she should die;

And that vile law’s unjust, which so decreed,

One of undue severity, say I,

So iniquitous it must be repealed,

And to a new and better law shall yield.

If the same ardour, if a like desire,

Moves both the sexes, and both equally,

To that sweet end of love, and with like fire,

In which sad folk naught but excess can see,

Why should the woman take the blame entire?

Merely for doing what the man is free

To do with as many maids as he would,

And go unpunished, as if twere a good!

They are rendered unequal by this law,

A wrong’s expressly done to the woman.

God willing, I will show tis so, before

All men; tis borne too long, its time is done!’

All there agreed it should be used no more,

And that their sires were wrong, every one,

Who had consented to such injustice,

And the king, if he would not amend this.

Canto IV: 68-72: Rinaldo rescues a maiden

When with its white, and crimson blush, the dawn

Heralded the day, and the skies grew clear,

Rinaldo, armed, and by good Bayard borne,

Rode with his guide, through the forest drear

And dense, mile after mile, on paths unworn,

Until the knight and his escort drew near

To the city where her case had been moved,

And the maid’s innocence must now be proved.

Now, having sought the swiftest path to take,

They had left the broader track, completely,

When suddenly a sound arose, to break,

The silence, amidst the woods, and swiftly

He spurred Bayard, the other too did rake

His palfrey’s sides, and plunged to a valley,

Whence came the sounds; and, twixt two villains there,

He saw a lady, who seemed passing fair.

Yet she was as tearful, and full of woe,

As any maid on this earth was, ever,

Hastened to her death, by this vile duo

That sought to redden the grass around her.

She, with her prayers, looked for pity though,

And hoped to stave off death, by her fervour.

Came now Rinaldo, and to their surprise

Rode at the villains, with threatening cries.

On seeing help arrive, they turned and ran,

While he considered their two backs in flight;

To hide in that deep vale was all their plan,

Though their pursuit seemed worthless to the knight.

He sought the tearful lady, then began

To question her as to the fault that might

Have led to this, while ordering the guide

To take her up behind him, and so ride.

Once on their way, he could see her nearer,

And though her face, indeed, still showed dismay,

He found her beautiful, marked her sweet manner,

Despite the fear of death that turns one grey.

Then, once more, who was the man, he asked her,

Who’d brought about her woeful state that day.

In humble tones she answered his request, though

I’ll defer it to another canto.

The End of Canto IV of ‘Orlando Furioso’