Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto III: The House of Este

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto III: 1-4: Ariosto seeks inspiration to sing of the House of Este

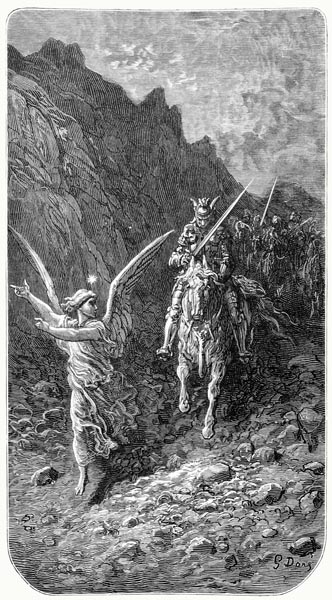

- Canto III: 5-8: Bradamante enters the cave and meets the sorceress Melissa

- Canto III: 9-15: And learns that beneath the cave lies Merlin’s tomb

- Canto III: 16-21: Merlin’s spirit foresees the lineage that stems from her

- Canto III: 22-25: Melissa conjures the first shade, the founder of the House of Este

- Canto III: 26-63: She gives an account of the future Este line

- Canto III: 64-68: Bradamante rides forth with Melissa as her guide

- Canto III: 69-75: Melissa tells her of the magic ring in Brunello’s possession

- Canto III: 76-77: Bradamante finds Brunello at the inn

Canto III: 1-4: Ariosto seeks inspiration to sing of the House of Este

Who will grant me a voice, and words to speak,

Which might befit so glorious a theme?

That, lending wings to my verse, will seek

To aid my flight towards the heights I dream?

Greater power to reach the mountain peak

I need than ever filled my breast, I deem;

For this, that follows, to my lord I owe,

That sings of those from whom his virtues flow.

For none more glorious in peace or war,

Came from heaven to earth, to rule us here;

None more illustrious Phoebus ere saw,

Who shines, and so illuminates our sphere;

No lineage has served its subjects more,

And shall serve yet, if this light, true and clear,

Of prophecy, within me shines aright,

While, round the pole, circle the heavens bright.

Yet to declare their honours here entire,

Apollo, yours the strings, not mine, we need,

That to sing out Jove’s glory did aspire,

After the war the Giants sought to breed.

If instruments, more fitting than my lyre

To carve the stone, in this my hour of need,

You grant me, all my skill I will apply,

And all my wit, these forms to beautify.

Till then, with humble chisel, I will seek

To smooth the marble, cut the flakes away,

And, perchance, improving my technique,

Perfect this work that I attempt, someday.

Yet now, again, of that vile man I’ll speak,

Whose armour shall protect him not, I say;

Pinabel of Maganza is that knight,

Who’d hoped to kill our warrior outright.

Canto III: 5-8: Bradamante enters the cave and meets the sorceress Melissa

The traitor thought our Bradamante dead,

In that precipitous tumble, and so,

With pallid face, straight from the chasm fled,

And from the light, his evil stained, below.

Then, swiftly mounting, to his saddle wed,

Like one whose spirit did but darkness know

And lapsed from sin to sin and fault to fault,

Purloined the warrior’s steed too, by default.

Let us now quit that wretch, who for the maid

Planned instant death, yet but procures his own,

And turn to that fair knight he had betrayed,

Who so close to death and the tomb had flown;

Dazed she arose, such was the price she’d paid,

For meeting with that floor of solid stone,

And then made entry to the first bright cave,

That access to a larger cavern gave.

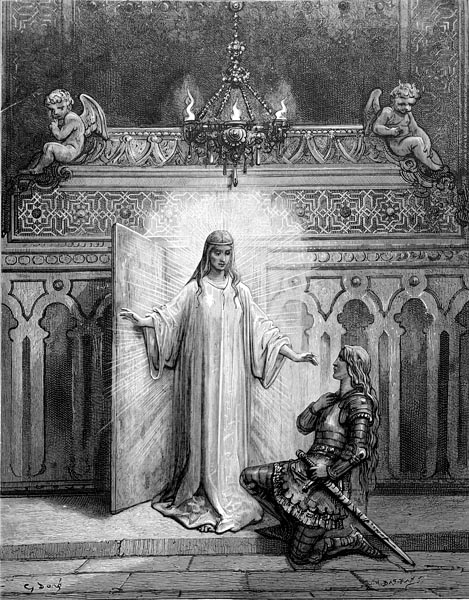

The place was square and spacious, and it seemed

To be a chapel, used from ancient days,

Where columns of pure alabaster gleamed,

Supporting the roof in various ways,

The rare and lovely architecture dreamed

By some skilled craftsman, while the light did blaze

From a lamp before the central altar,

That filled both the caverns with its splendour.

Most humble and devout thoughts filled her mind,

Viewing the holy place in which she stood;

She knelt, and her heart, by prayer refined,

Gave thanks to God, the source of all her good.

And then she heard a door creak; from behind

The altar came there one of noble blood,

Barefoot, with hair loose, and her dress the same,

That greeted the warrior-maid by name.

Canto III: 9-15: And learns that beneath the cave lies Merlin’s tomb

‘O generous, Bradamante!’ she cried,

‘By divine will alone you reach this place;

For long ago, wise Merlin prophesied

That this most sacred chapel you would grace,

Thus, reaching, by a means not often tried,

The precincts that his relics now encase;

And here I’ve waited, that I might reveal

To you what heaven, and the fates, conceal.

This is the ancient memorable cave

Merlin, the sage enchanter, created.

The hateful way in which she did behave,

The Lady of the Lake, is oft related,

While here, beneath us, is the very grave

In which his corrupted flesh was fated

To remain, to sate her will; and where he,

Entombed alive, now lies dead, seemingly.

A living mind dwells in that dead body,

Till is heard the angelic trumpet sound,

That shall raise, or banish it completely,

On dove or raven’s wing; yet, in the ground,

His voice lives, and you shall hear how clearly,

From out the marble tomb it doth resound;

For whoever asks that voice will answer,

Speaking of things past, and of the future.

Tis many days since, from a far country,

I came to this sepulchre, so that I,

That make the arcane mysteries my study,

Might see as Merlin, with as clear an eye;

And, since I wished to meet you, did tarry

Here a full month beyond, and know you why?

Merlin, who truth to come doth e’er convey,

Prophesied your presence, and on this day.’

Amone’s warrior daughter, amazed,

In silence heard the speech that she did make,

Her mind so full of wonder, as she gazed,

She knew not if she dreamed or was awake.

And then with humble, downcast eyes, still glazed,

Like one who would bow for modesty’s sake,

Replied: ‘What merit can there be in me,

To make me worthy of such prophecy?’

Yet, delighted by this strange adventure,

She now moved to follow the sorceress,

Who led her to the sepulchre beneath her,

Enclosing Merlin’s bones and soul, no less.

Twas built of hard stone that lasts, forever

Of a fiery red, translucent brightness,

Such that, though hidden from the sun, the room

Shone with the light that issued from that tomb.

Whether tis in the nature of such stone,

Like a bright candle, to dispel the dark,

Or whether spells, and magic flame alone,

(Which indeed seems closer to the mark)

Or else some stellar influence unknown,

Produced the splendour blazing from that ark,

Fair sculptures, hues, many a lovely thing

The light adorned, that Merlin’s tomb did bring.

Canto III: 16-21: Merlin’s spirit foresees the lineage that stems from her

Scarcely had Bradamante raised her foot

From the threshold of that most secret cell,

When a living voice the deep silence cut,

And, speaking clear, as from a stony well,

Said: ‘May Fortune’s fair gaze ne’er be shut

From you, O noble maid, where’er you dwell;

From your chaste womb a fecund race shall rise,

That Italy, and all the world, must prize.

The noble blood that issued forth at Troy

Merging in you its most glorious streams,

Will yield the flower, the ornament, the joy

Of every lineage on which Phoebus gleams,

That doth fierce cold, or burning heat enjoy,

By Indus, Tagus, Nile or Danube teems;

And midst your progeny, crowned with honour,

Dukes, marquises, emperors shall prosper.

Brave knights and captains shall arise from you,

Who with true wisdom, and the lance and sword,

Shall all the ancient honour, all that’s due

And yet denied, to Italy afford,

While just men shall uphold her laws anew,

Such as Numa and Augustus did record;

And, under their true governance, once more

The golden age they shall to her restore.

And that heaven’s wish may thus be brought

To take effect in you, Ruggiero,

That you for wife has ever boldly sought,

Was chosen, from the first, to bless you so.

Let nothing interpose to mar that thought,

Though to meet the sorcerer you must go,

So that a thief who bars you from your good,

Shall not be first to seal your fate with blood.’

So saying, Merlin’s voice fell silent, there,

And gave way to wise Melissa and her task,

To show the maid her race, and thus prepare

To reveal each heir’s illustrious mask;

Whether they came from Hell or from elsewhere,

The many that she chose, seek not to ask;

But all she sought she gathered in one place,

Varied in their manner, and dress, and face.

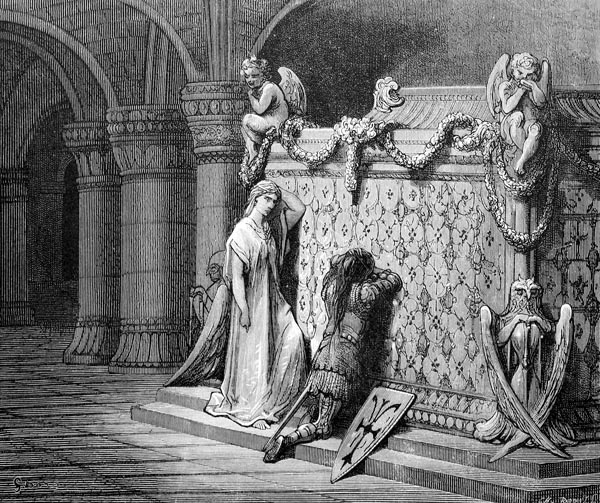

Then to the chapel she recalls our knight,

Where she inscribes a circle of a size

To hold the maid if she should fall outright,

With but a palm-width left if there she lies;

And that no spirit should invade the light,

Upon her head a pentacle she ties,

And tells her to be silent, stand and gaze,

Then opes her book, and to the demons prays.

Canto III: 22-25: Melissa conjures the first shade, the founder of the House of Este

Behold, what shapes from out the first cave press

About the sacred circle’s boundary,

And yet the way is barred to their ingress,

As though a moat ringed the sanctuary.

Full three times must they go, to win success,

About that border, ere they may be free

To enter in that cave that holds the urn

In which the prophet’s relics seem to burn.

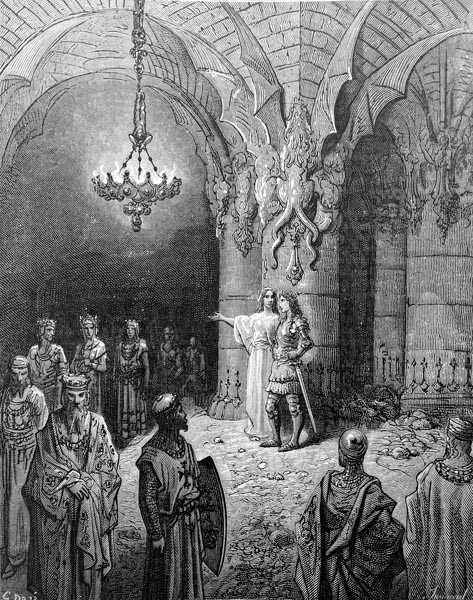

‘If I told the name and deeds of every one,’

The enchantress said to Bradamante, ‘then

I must speak of them, ere their deeds are done,

Before their birth, in truth, and how and when

I might conclude I know not, for the sun

Might set, and yet we’d not have cried amen;

So, I’ll but summon those I choose to me,

Granted both time and opportunity.

See now the first who’s like to you indeed,

In his fair seeming, and his pleasant face,

Conceived by you of Ruggiero’s seed,

The head in Italy of your proud race.

See him who’ll stain the earth, his good deed

To spill Pontier’s blood, who lacks grace,

And let fall the traitor’s sins on his head;

Vengeance on those who’d see his father dead.

Through his actions, King Desiderio

Will be conquered, the Lombards’ master;

Of Este and Calaon lordship, so,

He will be granted by the Emperor.

Behind him is your grandson Uberto,

Bearer of arms and his country’s honour.

That on the Barbarians shall descend,

And Holy Church many a time defend.

Canto III: 26-63: She gives an account of the future Este line

Next, the unconquered captain, Alberto,

That trophies in many a shrine will lay;

With him goes, at his side, his son Ugo,

Who’ll take Milan, and the viper display;

The next, will rule Insubria, Azzo

In his dead brother’s realm shall hold sway;

See Albertazzo, through whose opinion,

Berengar will be banished, and his son.

His worth is such that emperor Otho

Will marry him to Alda, his daughter.

O noble line! Behold, another Ugo,

The son no less worthy than the father,

He with just cause the pride will overthrow

Of the contentious Romans, and after,

Removing Otho the Third from their hands

With Pope Gregory, end all their demands.

See Fulke, who will grant to his brother

All his patrimony in Italy,

And for that realm will accept another,

Midst Germany, as Duke of Saxony,

Those lands inherited by his mother,

Its rulers falling from their high degree,

While Alda’s line he will thus maintain,

And through his progeny her rights sustain.

Azzo the Second now his face doth show,

Famed for his courtesy, less so in war;

His sons Bertoldo and Albertazzo.

The former shall prove Henry’s conqueror;

A river of Belgian blood will Parma know,

Staining all the fields at that city’s door.

The latter will the wise Matilda wed,

She, the Great Countess, chaste and nobly bred.

His virtues of that will make him worthy,

Great praise indeed, in his day, to receive

Half of Italy as the kingdom’s dowry,

And the hand of such a one, I believe.

Rinaldo, Bertoldo’s son, you now see,

He that the greatest honour will achieve,

Of rescuing the Church from Barbarossa,

His emblem the white eagle thereafter.

Azzo the Sixth shall hold Verona,

(Behold him here!) with all its territory,

And be styled the Marquis of Ancona,

By Otho and Honorius; twould be

A lengthy task to show every other

Of your blood, that for the Consistory

Raises the banner, or count every deed,

Aiding Holy Church, of your noble breed.

See Obizzo, Fulke, Azzi and Ugo;

Two Henrys, the son beside the father,

Two Guelfs; the one, to Umbria a foe,

Gaining it, shall hold Spoleto after.

Now, behold one who shall stem the flow

Of Italy’s tears, turning woe to laughter.

Azzo the Seventh (there, he is the one)

By him shall vile Ezzelino be undone.

Ezzelino, that inhuman tyrant,

A man that shall be thought the Devil’s son,

Many a city’s leaders will supplant,

Wasting Ausonia, its folk undone;

Yet Azzo the Seventh reprieve shall grant,

There at Cassano see the battle won,

That Marius, Sulla, Gaius, Nero,

Shamed, and Frederick the Second also.

Azzo, with happier sceptre, shall hold

Ferrara by the Rover Po’s fair stream,

Where Phoebus’ lyre, lamenting, wept the bold

Phaethon, his son, who drove his noble team

Too near the fiery orb, so that, of old,

Its trees weep amber, where the waters gleam

O’er which pale Cygnus glides so silently;

Azzo receives it, from the Holy See.

What of his brother, Aldobrandino?

He will grant succour to the Papacy,

And counter the Ghibellines and Otho,

As they wage war on Rome savagely,

Each nearby township dealt a bitter blow;

Then the Umbrians, and Picentini,

He will curb, and lacking funds will borrow

From Florence; his pledge his brother Azzo;

Naught else supports his promise to repay,

So, he must leave his brother in their care.

His victorious ensign he’ll display,

(The German army its defeat must bear)

Restoring to the Church the lands alway,

While the Earl of Celano death must share.

Then, at the service of the Papal power,

He’ll die, severed in manhood’s early flower.

He’ll leave to his elder brother Azzo,

Lordship of Pesaro and Ancona,

With all the towns lying twixt the Tronto,

From mountain to shore, and the Foglia,

And virtue, that precious jewel, also,

Greatness of spirit, faith; superior

To all the riches in Fortune’s dower,

Since only virtue stands against her power.

Rinaldo see; valour in him will shine

No less radiantly, though ill Fortune

And Death, in ire, and envy of your line,

Shall yet destroy his promise all too soon;

Hear the dirge rise, in Naples he must pine,

Hostage for his father, at eve and noon.

And now the young Obizzo shows his face;

Legitimised, takes his grandfather’s place.

To that fair dominion he will add

Bright Reggio, ferocious Modena,

His valour such his subjects will prove glad

For him to serve them as martial leader.

One of his sons, Azzo the Eighth, the bad,

Will gain in dower the rule of Adria,

Bearing the standard, on Crusade, with pride;

Charles of Sicily’s Beatrice his bride.

Now in a fine, and friendly, group you see,

Many a fair prince of outstanding fame,

Obizzo, Alberto, filled with mercy,

Aldobrandino, Nicolo the Lame.

In haste, I’ll pass them by, silently;

Yet they’ll add Faenza to your name,

And take a firmer grip on Adria,

Her title shared with that sea forever;

And Rovigo, that cultivates the rose,

Which gives that town its name, as Rhodes, in Greek;

Comacchio, which fish-rich fens enclose,

That ever fears the Po’s two mouths that wreak

Great havoc, though its fisher-folk, God knows,

Desire the flood that offers what they seek;

Then there’s Argenta, Luco, and a store

Of towns and castles; a good thousand more.

See Nicolo, whom at a tender age,

The people will choose to be their lord;

Azzo and Tydeus in vain may rage,

That had hoped to gain by civic discord.

The lad’s childish pursuit will be to wage

War in play, which study shall afford

This Este such true skill with sword and spear,

The flower of warriors he shall appear.

Every rebellious scheme he’ll thwart,

And return upon its instigator,

Every stratagem, each tactic that’s sought,

He’ll perceive, and foil the perpetrator.

Ottobuono, the tyrant, may have brought

To Reggio and Parma sheer terror,

Yet, late to comprehend, he shall be reft

Of life, and all reclaimed he gained by theft.

That realm so fair, will after see increase,

Without it straying from the rightful way.

Nor shall any subject break the peace

That has not first felt injury, I say,

And so, Providence will never cease

To further its true destiny, alway,

But it shall prosper, and in peace endure,

Until the very heavens turn no more.

See Lionello; see Duke Borso too,

The first to add that title to your line,

The doyen of his age, a leader who

Shall reign in peace, and many arts refine.

Fierce Mars he shall imprison, hid from view,

The Fury’s hands behind her back entwine,

This splendid ruler’s every fond intent

To see the people of his realm content.

See Ercole, his half-brother, that might

Reproach his tardy neighbour’s feeble pace

And his listless forces, when in the fight,

At Molinella, he the troops must face,

And stem the rout, before they take to flight,

Naught gained but his Barco tower to grace,

Besieged; yet one of whom I’m still unsure

Whether he shines brighter in peace or war.

All Lucania, with all Apulia,

All Calabria, shall long remember

His jousting, his skill so singular,

As to garner him great praise and honour,

There, from the King of Catalonia,

And many a victory thereafter.

The dukedom shall be his, what is more,

Owed him, of right, some thirty years before.

As much as any realm may be in debt

To its great ruler, his realm shall be so,

Not only shall Ferrara wider yet

Extend; its marshlands drained; against the foe

New walls created; but here he shall set

Amidst the city, on his realm bestow,

Fine temples, palaces, theatres, squares,

And a thousand things to ease our cares.

Not only shall he his broad lands defend,

From the winged Venetian lion’s claws,

But when the Gallic forces shall descend

Upon Italy, and invade her shores,

Against his fair realm they shall not offend;

Without fear, untaxed, he her peace secures.

Not just for these, but other blessings yet,

To Ercole shall his folk prove in debt.

More so that he shall glorify your line

With two fair sons, like those born to Leda,

Alfonso, Ippolito the benign.

As her Castor and Pollux, forever,

Exchange a Stygian darkness malign

With the light above, each brother,

For the other, readily seeking death,

Shall brave endless night at every breath.

The great love of each other that they bear,

Will render the populace more secure

Than if Vulcan had twice encircled there

The walls with steel, their safety to ensure.

Alfonso with wisdom, beyond compare,

Justice shall combine, and love and law,

Such that Astrea seems returned again,

To this world that gave her so much pain.

And well were it that he should prove as wise

As his own father, and of like valour,

For Venice, on his flanks, her troops supplies

To one enemy and then the other,

And he with scant forces, yet replies.

I know not if mother or stepmother

Venice seems, but if a mother harsher

To her own than Procne or Medea.

Whatever time of day or night this lord

Shall issue forth from his realm to fight,

Rout and dismay he will the foe afford,

Whether on land or water, plain or height.

Ill led those soldiers of Romagna’s horde,

That war with friends and neighbours shall ignite;

Bloodied the soil enclosed then by the Po,

The Santerno, and the Zaniolo.

And there the Pope’s Spanish mercenaries,

Shall wage war against Alfonso’s army;

Bastia’s fortress they will take with ease,

Slaying its castellan, mercilessly,

For which crime, once the place he frees,

Alfonso leaves not one live enemy

Within its walls, lest they should seek their home,

Or carry news of their defeat to Rome.

He it shall be, with counsel and the sword

Will win great honour in Romagna’s fields,

For he to France’s marshals shall afford,

That great triumph where Pope Julius yields,

Or those Spaniards over whom he’s lord;

Their mounts swim in blood, lost their shields,

Where midst the dead, warriors there shall be,

Of Germany, France, Greece, Spain, Italy.

He now, in priestly habit, that shall place

A cardinal’s red hat, upon his head,

Sublime and generous, and full of grace,

Ippolito, to Holy Church is bred.

He shall, indeed, eternal matter trace,

To prose and rhyming verse his virtues wed,

By a just heaven that would add below

To our Augustus, a second Maro.

His deeds shall adorn his glorious line

Much as the sun adorns the living earth.

More than the moon above or stars divine,

Brighter than every light, is his worth,

Him I see, with few men neath his ensign,

Go forth in sadness, and return in mirth,

With fifteen captive gallies brought to shore,

While in the river he has sunk four more.

See one Sigismundo and the other,

See now Alphonso’s five fair sons, all dear;

With great glory, three the earth shall cover,

Unmatched on land or sea they shall appear.

To a fair daughter of France, one brother,

Ercole the Second, is wed; see, here,

A second Ippolito’s light shall shine,

His uncle’s equal, and adorn the line.

Francesco is the third; the other two

Shall die as infants, both named Alfonso;

Yet if every branch we were to view,

The worth of your lineage proving so

Sublime, then, indeed, as I have told you,

Many a night and day twould take to show

All of your descendants, so, if you please,

I’ll free these spirits and, in silence, cease.’

Thus, with the warrior-maid’s permission,

The skilful enchantress closed her book,

And all the spirits were as swiftly gone

As they to Merlin’s bones their passage took.

Then Bradamante, having gazed thereon,

Sought leave to speak anew, with a look:

‘And who then were that sorrowful pair,

Twixt Ippolito and Alfonso there?

They came sighing, and with eyes downcast,

Deprived of confidence, and full of shame;

I saw the brothers shun them, as they passed,

As if some sin of theirs had brought them blame.’

Melissa’s aspect changed, and then, at last,

She answered her, and those two shades did name:

‘Ah, Guilio, Ferrante, to what pain

That evil counsel led you, for small gain!

O sons, worthy of Ercole the Good,

Let not their great crime forbid all mercy,

The wretched pair are yet of your own blood,

Let justice in their case yield to pity.’

Then, in softer tones be it understood,

And turning once more to Bradamante:

‘I’ll say no more, yet linger with the sweet,

To share what’s bitter with you is not meet.’

As soon as the dawn light invades the sky,

You shall take the quickest way with me

To reach that fortress made of steel, on high,

Where dependent on another’s mercy

Ruggiero lies; through the woods shall I

Accompany you, until we reach the sea,

For if amidst the trees you cease to stray,

You cannot err; for straight then is the way.’

Canto III: 64-68: Bradamante rides forth with Melissa as her guide

There the warrior-maid remained that night,

Listening to the sound of Merlin’s voice

Seeking to convince her that, at first light,

Aiding Ruggiero must prove her choice;

So, leaving the cavern, then, our fair knight,

Who felt in the dawn all around rejoice,

Forth, by a dark and winding path, did ride,

The sorceress, beside her, as her guide.

They issued, from there, to a secret vale

Midst mountains inaccessible to man,

And all day without rest they strove to scale

The rugged cliffs, and surging torrents span;

And, since the path was tedious, to avail

Themselves of conversation was their plan,

Speaking of aught that might but make the way

Seem less severe; and, so, they passed the day.

The greater role the sorceress did take,

Advising Bradamante by what art

Ruggiero might be freed, and, for her sake,

How, without dying, she might play her part:

‘If you were Mars, or Pallas, you’d not make

An end of that wizard, though from the start

Both Charlemagne’s and Agramante’s aid

Were yours, and every skill you displayed.

Not only is his fortress walled with steel,

Impregnable those cliffs that rear on high,

His fearsome steed is taught to plunge and wheel,

And swoop, and soar again towards the sky;

He bears a fatal shield, he will reveal

Amidst the fight, so dazzling to the eye,

So confusing to every other sense,

It leaves his foes half-dead, without defence.

And if perchance you think it might avail

To close your eyes, and so avoid its light,

How would you know if he then chose to sail

Towards you and attack, or soar in flight.

Yet there’s a way to counter, without fail,

This and all other spells of that vile knight,

For there’s a remedy, a means that’s mine;

And none other in the world proves as fine.

Canto III: 69-75: Melissa tells her of the magic ring in Brunello’s possession

King Agramante has a precious ring,

One stolen from a queen of India,

And to a baron he has lent the thing,

One Brunello, who a little further

Along the path we now take is walking.

Whoever shall wear it on their finger,

Is proof against every charm and spell;

The mage’s art Brunello knows full well.

Brunello is most practised and most sly,

As I have said, and sent here by the king,

Commanding that his skill he should apply,

And, with the proven aid of this same ring,

Extract Ruggiero from that keep on high;

For Brunello boasted that he would bring

Ruggiero, once freed, to his master,

Who’d use him in his warfare thereafter.

Yet so that his release is owed to you,

And not the king, why then to free him so

From his enchanted cage you must pursue

The remedy I speak of, and must go

Three days along the coast we’ll shortly view;

To that I’ll lead you, and the path will show,

For, at your lodgings in the evening,

There shall you find the one who holds the ring.

That you may recognise the man on sight,

He has a curly head of hair, jet-black;

In stature he is scarce six palms in height,

Of beard, on cheek and chin, he has no lack;

Dull skin, and murky eyes, guarded not bright,

Thick eyebrows, a nose all squashed, his back

Clad in a courier’s mantle, short and neat

His clothes likewise, to make my sketch complete.

With this man the subject you may raise,

Of strange enchantments and mystic charms,

And show him your desire, in a phrase,

To seize the sorcerer in your two arms.

Yet hide your knowledge of the ring, always,

That ensures such magic never harms,

And he will offer to show you the way,

And keep you company, as well he may.

Then follow close behind, and when you near

That mount, and see it clearly, slay the man;

Let pity not restrain you, show no fear,

And heed my counsel, execute your plan;

But let no trace of your design appear,

Such that the ring shall hide him, as it can,

Since he will disappear before your eyes,

If his lips touch the ring. Ensure he dies.’

As she was speaking, they approached the shore,

Where the Garonne, at Bordeaux, meets the sea.

There not without a tear, perchance a score,

They said farewell, and parted company.

Amone’s daughter rode three days or more,

Beside the waves until, at evening, she

Found lodging at the inn where Brunello

Occupied a room until the morrow.

Canto III: 76-77: Bradamante finds Brunello at the inn

She recognised Brunello, at first sight,

His description lodged in her memory,

And asked him where he came from, outright,

And where he might be going presently.

With many a lie he answered the knight,

Yet she, forewarned, lied quite as well as he,

Concealed her name, sex, lineage and land,

While glancing, more than once, at his hand.

Her eyes, thus, rested on him, in her fear

Lest to his lips he raised his ring-finger,

While wishing he were far, and not so near,

Being well-informed as to his manner;

And this was the scene when to the ear

A sound arose, as they stood together,

Which I shall speak of, and explain its cause,

After my song has met with a brief pause.

The End of Canto III of ‘Orlando Furioso’