Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto II: The Sorcerer’s Castle

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto II: 1-4: Rinaldo denounces Sacripante as a thief

- Canto II: 5-10: They fight and Rinaldo gains the upper hand

- Canto II: 11-13: Angelica flees and meets a hermit in the wood

- Canto II: 14-17: The hermit conjures a sprite who intervenes in the duel

- Canto II: 18-24: Rinaldo seeks Angelica once more

- Canto II: 25-27: Reaching Charlemagne’s fortress he is sent to England

- Canto II: 28-30: His vessel is caught in a storm

- Canto II: 31-36: Bradamante meets a melancholy knight

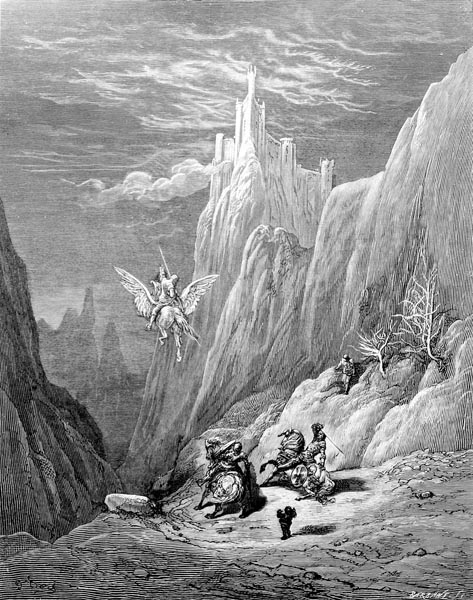

- Canto II: 37-40: Count Pinabel tells how his lover was snatched away

- Canto II: 41-44: And how he journeyed to the sorcerer’s castle

- Canto II: 45-47: And how he met King Gradasso and Ruggiero

- Canto II: 48-57: And how those two knights fought the sorcerer

- Canto II: 58-61: Bradamante wishes to be led to the sorcerer’s castle

- Canto II: 62-65: A messenger arrives, but Bradamante is undeterred

- Canto II: 66-68: Pinabel contemplates some evil deed

- Canto II: 69-73: They come upon a dark wood and a chasm

- Canto II: 74-76: Through Pinabel’s treachery Bradamante falls into the chasm

Canto II: 1-4: Rinaldo denounces Sacripante as a thief

Love, so unjust, in that you so rarely

Make our loves and hatreds correspond,

Why then, do you, the lord of perfidy,

Refuse thus to allow two hearts to bond?

You lead me not where the clear ford I see,

But into the flood, and its depths beyond:

The one I love you’d have me love no more,

Yet the one I hate you’d have me adore.

Rinaldo finds Angelica most fair,

While she considers him an ugly man,

Though, when she loved him truly and did care,

He hated her as deeply as one can.

Now he grieves in vain, in his despair,

Repaid in like kind: he where she began.

For she so hates this knight, in love with her,

That death to his embrace she’d much prefer.

‘Down from my horse, sir thief!’ Rinaldo cried,

Proudly threatening the Saracen knight.

‘I will not suffer any man to ride

My steed, and who does so must pay outright;

Nor shall the lady now with you abide,

For I’ll not leave her here, without a fight;

So fine a horse, a lady so worthy,

Do scarcely suit a thief it seems to me.’

‘In calling me a thief you do but lie,’

Cried Sacripante to the man, in answer,

(For no less haughty was his proud reply)

‘Though a word I hate, it suits you better.

Come let us prove who’s worthier, say I,

Of this lovely lady, and the charger;

For, as to her, we may indeed agree,

In all the world there’s none so fine to see.’

Canto II: 5-10: They fight and Rinaldo gains the upper hand

As two dogs, that would each other bite,

Through envy or some other form of hatred,

Will grind their teeth together, set to fight,

Their eyes like burning embers, fiery red,

Then on each other, jaws apart, alight,

Bristling, growling, straining head-to-head,

So, from threats and reproaches to the sword

Passed the king and the Chiaramonte lord.

The one on foot, the other mounted high,

Think you twas to the pagan’s benefit?

No more than if a hapless page should try

To prod the war-horse on which he doth sit,

For Bayard had, by instinct, rather die

Than such insult to his true lord admit.

So did the heathen king find in this case,

Nor hand nor spur led it to move a pace.

When the king thought to charge, it stood stock still,

When he would hold it back, it sprang away,

Or bowed its head towards its chest, at will,

Or arched its spine, or kicked as if in play.

Finding not one command it would fulfil,

Lacking the time to make the beast obey,

Grasping the pommel hard, he quit his seat,

Leapt from its flank, and landed on his feet.

As soon as Sacripante reached the ground,

Ceasing with Bayard’s stubbornness to fight,

In fierce assault did those two swords resound,

Their conflict worthy of the bravest knight.

Each weapon raised on high its target found;

Less swift was Vulcan’s hammer in its flight,

In that deep smoke-filled cavern where he strove

To forge the lightning-bolts of mighty Jove.

Now they lunge, or with feint and parry show

Their mastery of the sword; now they leap

High in anger, retreat now from a blow,

Show themselves, or their shields before them keep;

Drive forward, with a flurry, swift or slow,

Then give way, as many a thrust they reap,

Swivel round; and where one man’s foot doth yield

The other’s takes its place upon the field.

But now Rinaldo, with his sword raised high,

Throws himself wholly at the pagan king,

Who, with his shield of bone, would him deny;

Well-tempered steel its outer edge doth ring.

Yet the sword, Fusberta, falls from the sky,

Its steel as strong, and makes the forest sing;

With bone and metal shattered like thin ice,

The king’s arm’s rendered useless in a trice.

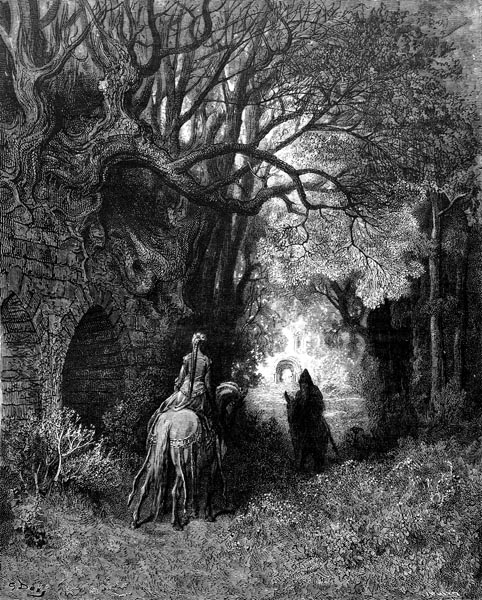

Canto II: 11-13: Angelica flees and meets a hermit in the wood

When the timid maid viewed the ruin dealt

By the great force behind that crushing blow,

Her face expressed the agony she felt,

As one condemned their misery will show;

Time for her to flee, the king’s downfall spelt,

Lest she become Rinaldo’s prey; her foe

That Rinaldo whom she loathed as deeply

As he now loved the maid most woefully.

She turned her horse into the tangled wood,

Galloping on, through rough and narrow ways,

Yet looked behind as often as she could,

Seeming to hear him following always.

And she had not gone far, for ill or good,

When, in the dale, a hermit met her gaze.

Whose beard, full long, descended to his waist;

Devotion, on his features, age had traced.

Made lean by fasting and the years, upon

A slow and steady mule the hermit came,

Seeming by his calm face, where wisdom shone,

Humble, pure of conscience, as free of blame

As any man yet living, or long gone.

Seeing the maid, delicate as her name,

However feeble he appeared to be,

And modest, he yet succumbed to pity.

Canto II: 14-17: The hermit conjures a sprite who intervenes in the duel

The lady asked him to point her, swiftly,

To some fair harbour of the closest shore,

From which she might quit France and so, once free

Of this Rinaldo, hear his name no more.

The hermit, who was skilled in sorcery,

Seeking to comfort her, and reassure

The lady she would soon be safe, now took

From a deep pocket a mysterious book.

And this he now deployed to great effect,

For he had barely uttered the first page,

Before a sprite appeared and, with respect,

Asked what he might perform now for the sage.

Then, a squire’s shape and garb he did effect,

And went to where the two knights did engage,

Amongst the trees, not in the open glade,

Where, most audaciously, their hands he stayed.

‘Tell me, of courtesy,’ the spirit cried,

‘What use is either’s death to the other?

What will you gain, true victory denied,

When this fine conflict of yours is over,

If Count Orlando, without having tried,

Without a single blow, free of bother,

Towards Paris leads the lovely lady,

That committed you to purgatory?

I met Orlando not a mile away.

To Paris with Angelica, he goes,

They ride together, making mock, I say,

Of you, and all your pointless painful blows.

Better twould be to follow them this day;

Hoof-prints they leave behind, I would suppose.

If he and she reach Paris, then tis plain,

Neither of you will that fair maiden gain.’

Canto II: 18-24: Rinaldo seeks Angelica once more

You’ll not have seen two brave knights more amazed;

For at the news, both men were most unhappy,

Their eyes were vacant, and their minds half-dazed:

Mocked by Orlando then, and the lady!

Rinaldo moved to where his charger grazed,

Breathing sighs forth that seemed most fiery,

And swore in his anger that, for his part,

If he found Orlando, he’d have his heart!

Reaching the place where Bayard was standing,

He leapt on the horse’s back, and sped away,

Without a word of farewell, and leaving

The king behind, nor pledging to convey

Him at his back, but, his charger spurring,

He drove the creature on, and would not stay,

Ditch, boulder, stream, or thorn, naught halts the horse,

Or serves to swerve the rider from his course.

Lest it seem strange to you that Rinaldo

Could mount upon the steed so easily,

Considering that, for a week or so,

He’d pursued that horse of his fruitlessly,

(Had he so much as touched the bridle? No!)

Well, its mind was well-nigh human, you see,

It fled but to lead him to the lady

Whom he loved, as it had heard but lately.

For when Angelica had left the tent,

The steed had seen and marked her sudden flight,

And naught was there to hamper its intent

Its saddle being empty of the knight,

Who had descended, upon battle bent,

Desiring with some lord, on foot, to fight,

And so had followed her you’ll understand,

Wishing to place her in its master’s hand.

Eager to lead him to where she might be,

Thereafter it had run on through the wood,

Nor would it let him mount, for fear that he

Might turn away, and lose the maid for good.

Twice had it found her yet, frustratingly,

Was thwarted, though achieving all it could,

First by Ferrau, and so deviating,

Then, as you have heard, by the pagan king.

Now Bayard had believed the conjured sprite,

Whose news had set them on a phantom trail,

And so allowed Rinaldo to alight

Upon his back, obeying without fail,

As his master followed the maiden’s flight,

Ever towards Paris, o’er hill and dale,

Filled with such eagerness that all too slow

Seemed a steed that fast as the wind did go.

Rinaldo was at such pains to pursue

And thus meet Orlando, Anglante’s lord,

For great was his belief the news was true

That the sorcerer’s sprite did him afford.

That night and morn he sought the path anew,

Until he crossed a plain, and rode toward

The fortress where Charlemagne now rested

After that battle so ill-contested.

Canto II: 25-27: Reaching Charlemagne’s fortress he is sent to England

There, with the remnants of his force, the king

Fearful of Moorish siege, had set his men

To gathering provisions, recruiting,

Breaking stone, and shoring the walls again;

All that might serve for defence procuring,

Without delay, to aid them, as and when.

And an envoy to England he would send,

That might new strength to his weak forces lend.

For again he sought to test himself in war,

And try his fate, on some fresh field, and so

To England, that was Britain long before,

He now chose to send the good Rinaldo.

And sore was he to go, you may be sure,

Not because he loathed the land, his woe

Was all because Charles saw him on his way

Without permitting him a moment’s stay.

Naught did Rinaldo do less willingly,

Being diverted from his former quest

For that fair visage which had utterly

Ravished the heart from out his burning breast,

But obedient to Charles, towards the sea

He made his way, prepared to do his best;

And, in a few hours, arrived at Calais,

Embarking, indeed, the very same day.

Canto II: 28-30: His vessel is caught in a storm

Ignoring the advice of the master,

Impatient to go so he might return,

He sailed on waters boding disaster,

The while a storm the narrow seas did churn,

A mighty tempest, waxing all the faster

Indignant at a pride that sense did spurn,

Raising the sea aloft with such power

Up to the masthead the waves did tower.

The watchful mariners soon manned the sail,

Intending to wear ship and come about,

Since, by so doing, they might yet prevail,

And reach the harbour from which they’d set out.

‘That I shall not permit,’ declared the gale,

‘For tis not fitting thus my will to flout!’

And, threatening shipwreck, as it howled and cried,

Strained the more gainst every tack they tried.

Now at the stern, now at the prow it blows,

Never ceasing, but ever growing more,

While the vessel, now tangled in its throes,

Fails, in the deep, to find the distant shore;

Yet since many a varied thread I chose,

On setting forth, and none must now ignore,

I’ll leave Rinaldo calmer waves to seek,

And of his sister Bradamante speak.

Canto II: 31-36: Bradamante meets a melancholy knight

The famed warrior-maid I mean by this,

Who toppled Sacripante to the ground,

Daughter of Amone and Beatrice,

And worthy of her brother, as we found.

Her mighty deeds and her ardent service

Did with Charles, and all of France, resound,

(That knew many a shining paragon)

As much as did her brother’s here and yon.

She was loved by a bold Saracen knight,

That o’er the waves with Agramante came.

His father, a Christian of true might,

Ruggiero, whose son now shared his name,

In Agolante’s daughter found delight,

That had borne this son of that very same.

And Bradamante loved the knight, though fate

Had one sole meeting granted them to date.

Since then, she had gone seeking her lover;

As safe, with none to keep her company,

As if a thousand guards protected her,

Trusting in her own skill and bravery.

Once Sacripante she had made to cover

The solid ground beneath, she sped swiftly

Through the wood and, after, o’er a mountain,

Until she came to a flowing fountain.

The spring flowed amidst a flowering meadow,

Adorned with ancient trees, that cast cool shade,

Inviting the passer-by to follow

Its murmuring, and rest there in the glade,

While a tamed hillside sheltered all below,

And, at full noon, a sanctuary made.

There, as she turned her lovely gaze, she saw

A knight’s great war-horse, though no knight it bore.

The youthful knight was sitting, pensively,

Beneath the shadow of a bush that grew

Beside the flowering bank, and silently

Watching the crystal stream as past it flew.

His helm and shield hung from a nearby tree,

To which his mount was fastened, in full view,

While he, with lowered gaze, and with a tear

Wetting each eye, full weary did appear.

That longing that stirs in every heart

To know the fate of another person,

Prompted the maiden now, with gentle art,

For his sadness to enquire the reason.

Won by her courtesy, he did impart

The cause of his woe, at this sweet season,

And with a noble look that, at first sight,

Confirmed him to be a valiant knight.

Canto II: 37-40: Count Pinabel tells how his lover was snatched away

He answered thus: ‘Brave knight, twas I who led

Horseman and infantry to that wide field

Where Marsilio our force awaited,

Seeking on his descent to make him yield,

As from the Pyrenees his army sped.

There, too, a maid I loved I sought to shield;

And yet, beside the Rhone, as fate decreed,

I saw one armed, atop a winged steed.

No sooner did that thief, amidst the air,

Whether mortal or some infernal sprite,

Behold the lovely lady in my care,

Than he stooped, as a falcon does in flight,

And caught her with his hands as in a snare,

And seizing her was well-nigh out of sight

Ere I had registered the bold assault,

Hearing her cry from out the sky’s blue vault.

So, the rapacious hawk will plunge, and thieve,

Stealing a new-born chick from out the pen,

Leaving its hapless mother there to grieve,

Squawking, or clucking sadly now and then.

I could not fly, and midst the high peaks weave,

To reach his ledge of rock, his cliff-bound den;

And now my steed is wearied to the bone,

Travelling these harsh trails, o’er shattered stone.

For I, like one who had far rather seen

His beating heart torn from his living breast,

Left my brave men, and quit the martial scene,

While, masterless, they rode to seek the rest,

Along well-trodden paths, amidst the green,

As I, by ways love showed me, sought the nest

To which that cruel bird had flown, on high,

Bearing my hope and peace towards the sky.

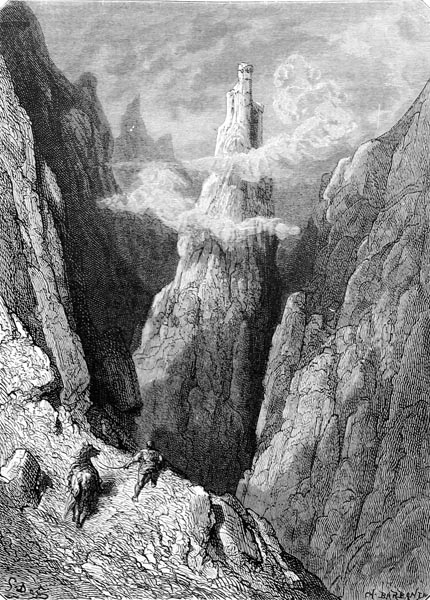

Canto II: 41-44: And how he journeyed to the sorcerer’s castle

Six days I journeyed on, from morn to eve,

Midst strange spires and hideous walls of stone.

Where paths were not, my mount a way did weave;

Where nothing human dwelt, I passed, alone,

Until a barren vale I did perceive,

Ringed by vast cliffs, with mighty boulders sown,

And in its midst, upon a rock, rose there,

A castle, strong and marvellously fair.

And from afar it shone like some bright flame,

Nor seemed it brick or marble to my eye,

For as I neared those walls now known to fame,

The finer and more wondrous twas, say I.

Later I learned a spirit wrought that same,

With spells, midst sulphurous fumes, raised it high,

Surrounding it with gleaming steel entire,

With Styx’s water tempered, out the fire.

Its shining turrets glowed with such a light

That I saw there no mark of rust, no stain;

The foul thief scours the land by day or night,

And then retreats within that bright domain.

All he desires he claims, without respite,

Though he’s pursued with curses, all in vain.

So, there she lies, who won my heart from me,

And lost all hope that I might set her free.

Alas, what’s left me but to keep my eye

Upon that fortress that holds my lady,

Like a she-fox that hears her lost cub cry

From the eagle’s nest, nor knows what she

Can do but pace the empty fields nearby,

Lacking the wings to seek her enemy;

Such is the castle on that rock, on high,

Unreachable by all that cannot fly.

Canto II: 45-47: And how he met King Gradasso and Ruggiero

And, as I lingered there, behold I saw

Two noble knights appear, a dwarf their guide;

They to my longing brought fond hope, once more,

Hope well-aimed though ever the shot fell wide.

Warriors both, those bravest knights in war,

The King of Sericane, and at his side

One that the Moorish courts valued so,

Their names Gradasso, and Ruggiero.

“They come,” the dwarf proclaimed, “to try their worth,

Against that mighty castle’s errant lord,

To whom that winged creature of evil birth

Strange, unnatural passage doth afford.”

“Fair sirs,” said I, “oh, fairest knights on earth,

Have pity on me, whom fate grants scant reward!

Once the hoped-for victory you attain,

Come render me my lady, once again.”

I told how the thief had seized my lady,

Witnessing my woe with many a tear,

They offered, in turn, a wealth of pity,

And then along a track, stony and sheer,

Made their way towards that evil city,

(While I remained, praying to God in fear)

To reach, below the wall, a piece of ground,

Perchance in width a few yards, all around.

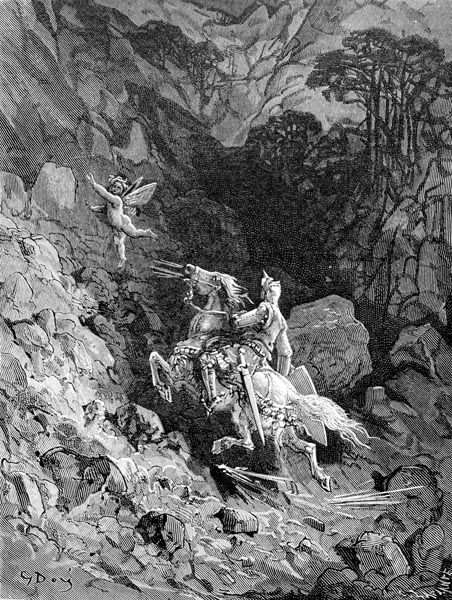

Canto II: 48-57: And how those two knights fought the sorcerer

When both attained the base of that high wall,

They argued as to which of them should fight,

Whether to Gradasso the lot should fall,

Or on brave Ruggiero should alight.

The king, indeed, sounded his battle call,

The fortress ringing to its topmost height.

Behold! All armed, the sorcerer appeared,

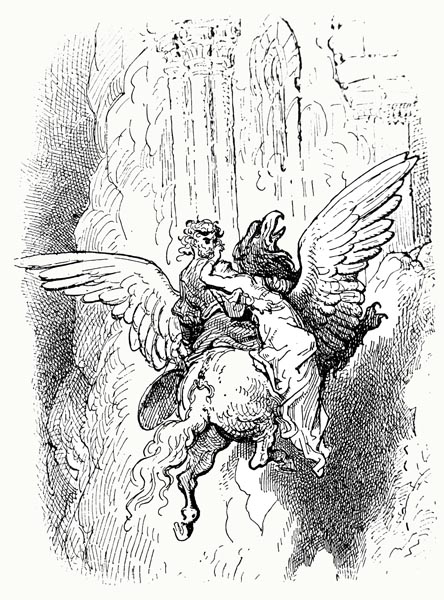

Outside the gate, on his fell steed upreared.

Slowly, at first, his mount took to the skies

As a crane will do, its wings beating,

Running uncertainly, e’er it doth rise,

But then once launched, the ground beneath skimming,

It puts forth all its strength and upward flies,

Faster and faster, and onward sailing.

So, on high the sorcerer soared in flight,

An eagle scarce ascending to such height.

When he saw fit, he wheeled his steed around;

Closing its wings, it plunged down through the air,

As a well-trained falcon, its quarry found,

Dives at the duck or pigeon it doth scare.

So came, their enemy, with fearsome sound,

With lance outstretched, upon the valiant pair,

Gradasso scarcely saw his advent, though

He heard his passage, and he felt the blow.

The sorcerer’s lance shattered; Gradasso

Striking the empty air, in vain fury,

Yet hardly troubling the creature so;

It beat its wings, and soared away swiftly.

His valiant steed, at the encounter, though,

Reared from the turf, surprised utterly;

It was an Arab steed the king did ride,

The finest ever man did sit astride.

Up towards the stars the sorcerer flew,

Then, wheeling, plunged towards the earth again,

Striking at Ruggiero ere he knew,

That his gaze on Gradasso did maintain.

He bent beneath the blow, his charger too

Recoiled a pace or so, and shook its mane.

Yet when Ruggiero turned to reply,

He saw his foe far distant in the sky.

Gradasso, then Ruggiero, in turn,

On forehead, chest, and back, he strikes with force,

While all their empty blows no merit earn;

They ever fail to see him in his course.

He circles widely, nor can they discern

Whom next he will endeavour to unhorse.

Their eyes he dazzles, thus they never know

From which direction they’ll receive the blow.

Between those two on earth and their foe above

War continued till the fall of evening,

That veiling the earth, doth light remove,

Stealing the fairest hues from everything.

Twas as I say; I saw it, and might prove

The matter, though but tentatively bring

It to your eyes for, marvellous to view,

Retold, it might seem rather false than true.

The celestial foe had veiled the shield

Upon his arm in a silken cover,

Though I know not why he took the field

And yet displayed it not, while he did hover,

For it so dazzled once it was revealed,

His opponent his sight could ne’er recover,

But must tumble corpse-like to the ground,

And by the sorcerer’s power be bound.

Like to a gemstone the shield shone bright,

Though brighter than has any other shone;

None could choose but stagger at the sight,

Fall blinded to the ground, the senses gone.

I too was dazed, though distant from its light,

And when the scene I once more gazed upon,

No dwarf, no knights I saw, the place was bare,

The mount, the plain, and all was darkness there.

I deemed them gone with the fell enchanter,

Those warriors seized, and so borne away;

Trapped, by virtue of that blazing splendour,

Their freedom lost, and my hopes all astray.

To those walls, that held my heart prisoner,

I said a last farewell, and sought my way.

Now, judge: was ever greater punishment

Than mine incurred, by one on love intent?’

Canto II: 58-61: Bradamante wishes to be led to the sorcerer’s castle

The knight relapsed into his gloomy state,

Lacking the wish to speak now, or the need.

Twas Pinabel this sad tale did relate,

Anselmo d’Altaripa’s son, indeed,

Of the Maganzesi, his noted trait

Was to disdain, amidst that evil breed,

Loyalty and courtesy while, no less

Than they were, steeped in vice and wickedness.

With varying expressions, the fair maid

Gave ear to the melancholy knight,

For, at Ruggiero’s name, she displayed

A look that conveyed intense delight,

Yet hearing further how he was dismayed,

True signs of love and pity showed outright,

Not satisfied until not once but twice

He’d told the tale, and scarce did that suffice.

And when at last the thing was clarified,

‘Rest now awhile, sir knight, for our meeting

May prove to be of worth to you,’ she cried,

‘And fortunate the day I gave you greeting!

To this castle, that so fair a gem doth hide,

Let us go; for their venture’s worth repeating,

Nor will my martial efforts seem in vain,

If Fortune will but prove my friend again.’

The knight replied: ‘You wish that I should pass

That mountain track anew, and show the way?

It is no loss to me, who now, alas,

Have lost all I possessed; yet those, I say,

That seek to penetrate that rocky mass,

Gain but a prison, and prolong their stay.

So, blame me not, for what shall come to be;

Since all that I’ve warned you of, you shall see.’

Canto II: 62-65: A messenger arrives, but Bradamante is undeterred

This said, the knight mounted his steed once more,

And served the bold warrior-maid as guide,

That for Ruggiero’s sake sought fresh war,

To free her knight, or on the field abide.

But now, behold, a messenger they saw,

One riding hard: ‘Await my news!’ he cried;

Twas from his lips King Sacripante found

How twas a maid had felled him to the ground.

Now, to that warrior, the news he brought

Of how Montpellier had, with Narbonne,

Raised high the standard of Castile, and fought

Against the Moors’ incursion, whereupon,

With Aigues-Mortes in arms, all Marseilles sought

Her help, that oft times to their aid had gone,

Ever recommending themselves to her,

And requesting counsel now, and succour.

This city, with great tracts of land around

Betwixt the Var and Rhone, set by the sea,

King Charlemagne had to the maiden bound,

In whom his trust and hope he placed, for he

In her a wondrous warrior had found,

A miracle of armoured chivalry.

Now, from Marseilles, this messenger was sent,

As I have said, on seeking aid intent.

Twixt yea and nay, uncertain, the maiden

Mused awhile: whether to return, or no?

Honour and duty weigh with her, but then

The flame of love now burns within her so,

She can but turn to her first aim again,

To free Ruggiero, and end his woe;

Or, if her skill or her strength should fail her,

To dwell beside him there, a prisoner.

Canto II: 66-68: Pinabel contemplates some evil deed

So fair was her excuse, the messenger

Was pleased to, quietly, await her will;

She shook the reins, and urged her steed to stir,

Then followed Pinabel who, gloomy still,

Seemed none too pleased, for indeed he knew her

To be of a hated line, boding ill

For him, if she should come to discover

That he, a Maganzese, sought to guide her.

Twixt Maganza’s and Chiaramonte’s line

Lay bitter hatreds, ancient enmity;

Many an evil plan they would design

Against each other, till the blood ran free.

And so, the wicked count, his heart malign,

Thought to betray this maid, all unwary;

Or, at least, when it seemed convenient,

Leave her alone, as on his way he went.

Such was the innate hatred, doubt, and fear

That filled his mind, he, inadvertently,

Went astray, and far from the path did veer,

And in a dark wood found himself to be,

With, in its midst, a hilltop standing clear,

Its summit bare, in stony majesty,

While behind him rode Amone’s daughter,

Whom he led towards despair or slaughter.

Canto II: 69-73: They come upon a dark wood and a chasm

He, when he found himself within the wood,

Thought to abandon her, that rode behind,

And said to her: ‘Ere it grows dark, we should

Seek some fair place to rest, and lodging find.

Beyond that hill, if memory holds good,

Stands a fine castle in a dale, but mind,

You must wait here for me while I ascend

That bare summit, and see which way to wend.’

So saying, he spurred onwards to the height,

And, climbing that bare, solitary hill,

Sought out some evil plan whereby he might

Be rid of her, and his intent fulfil,

When, lo, a rocky chasm met his sight,

Falling two hundred feet or more, until

Its spurs and hollows reached a stony floor,

And there, within its depths, appeared a door.

This portal, that lay fully open, gave

Wide access to a spacious room inside,

And a great brightness issued from that cave,

That to the gloomy depths did light provide.

Yet while the wretch was musing there, the brave

Warrior-maid, who’d followed her ill guide,

(Fearing lest she be stranded in the wood)

Came fast upon the villain where he stood.

Finding his first design was all in vain,

The traitor sought a different strategy,

By which to rid himself now of his bane,

Or send down to the grave his enemy.

And so, returned a little way again,

And asked her to ascend, most urgently,

For he had spied, he said, in that bright place,

A lovely maiden that was fair of face,

Who, by her aspect, and manner of dress,

Seemed of a noble rank, of high degree,

Yet troubled sorely, and in great distress,

Imprisoned there, as far as he could see.

And when he’d endeavoured to make ingress

To seek the reason for her misery,

Someone had issued from the inner cave

Whose display of anger the reason gave.

Canto II: 74-76: Through Pinabel’s treachery Bradamante falls into the chasm

Bradamante, ever as unwary

As she was bold, trusted this Pinabel,

And, eager to bring aid to the lady,

Thought how she might descend to her deep cell.

In glancing round, she saw an old elm-tree

With a long branch that served her purpose well;

Severing it with her sword, in a trice,

Into the depths, she lowered her device.

To Pinabel, she gave the severed end,

While, in both hands, she yet held the other,

Then, feet first, sought the chasm to descend;

As she clung there, Pinabel, above her,

Said, laughingly, that she must now depend

On her powers of flight, and then the traitor

Let her fall, crying: ‘Would I might deal so

With your whole house, and send them all below!’

Yet all went not as Pinabel intended,

Not such the guiltless Bradamante’s fate,

For as, into the depths, she descended

The elm-branch broke her fall, and held her weight,

And though it splintered, yet still she ended

Her descent in not too dire a state,

For she lay there quite dazed, but still alive,

To tell of which in canto three I’ll strive.

The End of Canto II of ‘Orlando Furioso’