Homer: The Odyssey

Book XI

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2004 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XI:1-50 Odysseus tells his tale: Ghosts out of Erebus

- Bk XI:51-89 Odysseus tells his tale: The Soul of Elpenor

- Bk XI:90-149 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Teiresias

- Bk XI:150-224 Odysseus tells his tale: The Spirit of Anticleia

- Bk XI:225-332 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghosts of Famous Women

- Bk XI:333-384 Alcinous asks Odysseus to continue his narration

- Bk XI:385-464 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Agamemnon

- Bk XI:465-540 Odysseus tells his tale: The Spirit of Achilles

- Bk XI:541-592 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Ajax and others

- Bk XI:593-640 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Heracles and others

BkXI:1-50 Odysseus tells his tale: Ghosts out of Erebus

‘On reaching the shore, we dragged the vessel down to the glittering sea, and set up mast and sail in our black ship. Then we hauled the sheep aboard, and embarked ourselves, weeping, shedding huge tears. Still, Circe of the lovely tresses, dread goddess with a human voice, sent us a good companion to help us, a fresh wind from astern of our dark-prowed ship to fill the sail. And when we had set the tackle in order fore and aft, we sat down, and let the wind and the helmsman keep her course. All day long with straining sail she glided over the sea, till the sun set and all the waves grew dark.

So she came to the deep flowing Ocean that surrounds the earth, and the city and country of the Cimmerians, wrapped in cloud and mist. The bright sun never shines down on them with his rays neither by climbing the starry heavens nor turning back again towards earth, but instead dreadful Night looms over a wretched people. There we beached our ship, and landed the sheep, and made our way along the Ocean stream, till we came to the place Circe described.

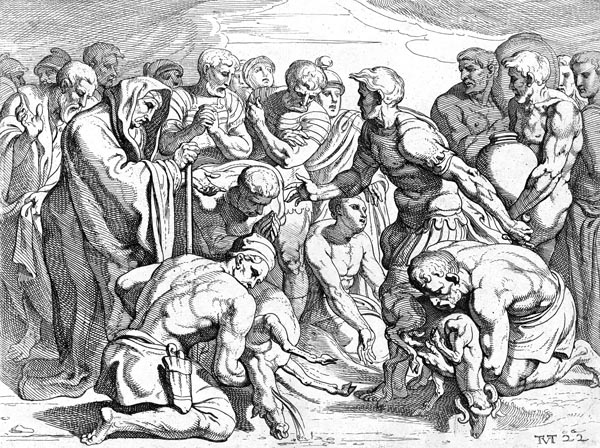

‘Odysseus arrives in the Underworld’

Perimedes and Eurylochus restrained the sacrificial victims while I drew my sharp sword from its sheath, and with it dug a pit two foot square, then poured a libation all around to the dead, first of milk and honey, then of sweet wine, thirdly of water, sprinkled with white barley meal. Then I prayed devoutly to the powerless ghosts of the departed, swearing that when I reached Ithaca I would sacrifice a barren heifer in my palace, the best of the herd, and would heap the altar with rich spoils, and offer a ram, apart, to Teiresias, the finest jet-black ram in the flock. When, with prayers and vows, I had invoked the hosts of the dead, I led the sheep to the pit and cut their throats, so the dark blood flowed.

‘The sacrifice of the sheep’

Then the ghosts of the dead swarmed out of Erebus – brides, and young men yet unwed, old men worn out with toil, girls once vibrant and still new to grief, and ranks of warriors slain in battle, showing their wounds from bronze-tipped spears, their armour stained with blood. Round the pit from every side the crowd thronged, with strange cries, and I turned pale with fear. Then I called to my comrades, and told them to flay and burn the sheep killed by the pitiless bronze, with prayers to the divinities, to mighty Hades and dread Persephone. I myself, drawing my sharp sword from its sheath, sat there preventing the powerless ghosts from drawing near to the blood, till I might question Teiresias.’

BkXI:51-89 Odysseus tells his tale: The Soul of Elpenor

‘The first ghost to appear was that of my comrade Elpenor. He had not yet been buried beneath the broad-tracked earth, for we left his corpse behind in Circe’s hall, unburied and unwept, while another more urgent task drove us on. I wept now when I saw him, and pitied him, and I spoke to him with winged words: “Elpenor, how came you here, to the gloomy dark? You are here sooner on foot than I in my black ship.”

At this he groaned and answered me, saying: “Odysseus, man of many resources, scion of Zeus, son of Laertes some god’s hostile decree was my undoing, and too much wine. I lay down to sleep in Circe’s house, and forgetting the way down by the long ladder fell headlong from the roof. My neck was shattered where it joins the spine: and my ghost descended, to the House of Hades. I know as you go from here, from Hades’ House, your good ship will touch again at Aeaea’s Isle, and I beg you, by those, our absent ones we left behind, by your wife, by your father who cared for you as a child, by your only son Telemachus forsaken in your halls, I beg you, my lord, remember me. When you sail from there, do not leave me behind, unwept, unburied, and turn away, lest I prove a source of divine anger against you. Burn me, with whatever armour I own, and heap up a mound for me on the grey sea’s shore, in memory of a man of no fortune, that I may be known by those yet to be. Do this for me and on my mound raise the oar I rowed with alive and among my friends.”

He spoke, and I replied: “Man of no fortune, all this I will remember to do.” So we sat, exchanging joyless words, I on one side of the trench, holding my sword above the blood, my friend’s ghost on the other, pouring out his speech.

Then there appeared the soul of my dead mother, Anticleia, daughter of noble Autolycus: she who was still alive when I left to sail for sacred Troy. I wept at the sight of her, and my heart was filled with pity, yet I could not let her approach the blood, despite my grief, till I had questioned Teiresias.’

BkXI:90-149 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Teiresias

‘Then the ghost of Theban Teiresias appeared, carrying his golden staff, ad he knew me, and spoke: “Odysseus, man of many resources, scion of Zeus, son of Laertes, how now, luckless man? Why have you left the sunlight, to view the dead in this joyless place? Move back from the trench and turn aside your blade so I may drink the blood, and prophesy truth to you.”

At this, I drew back and sheathed my silver-embossed sword. When he had drunk the black blood, the infallible seer spoke and said: “Noble Odysseus, you ask about your sweet homecoming, but the god will make it a bitter journey. I think you will not escape the Earth-Shaker, who is angered at heart against you, angered because you blinded his son. Even so, though you shall suffer, you and your friends may yet reach home when you have sailed your good ship to the island of Thrinacia, and escaped the dark blue sea, and found there the cattle and the fat flocks of Helios, he who sees and hears everything, if only you can control your own and your comrades’ greed. If you keep your hands off them, and think only of your homeward course, you may yet reach Ithaca, though you will suffer. But if you lay hands on them, then I foresee shipwreck for you and your friends, and even if you yourself escape, you will come unlooked-for to your home, in sore distress, losing all comrades, in another’s vessel, to find great trouble in your house, insolent men who destroy your goods, who court your wife and offer gifts of courtship.

‘Teiresias drinks the blood of the sacrifice’

Yet, I speak truth, when you arrive there you will take revenge on them for their outrages. When, though, you have killed the Suitors in your palace, by cunning or openly, with your sharp sword, then pick up a shapely oar and travel on till you come to a race that knows nothing of the sea, that eat no salt with their food, and have never heard of crimson-painted ships, or the well-shaped oars that serve as wings. And let this be your sign, you cannot miss it: that meeting another traveller he will say you carry a winnowing-fan on your broad shoulder. There you must plant your shapely oar in the ground, and make rich sacrifice to Lord Poseidon, a ram, a bull, and a breeding-boar. Then leave for home, and make sacred offerings there to the deathless gods who hold the wide heavens, to all of them, and in their due order.

And death will come to you far from the sea, the gentlest of deaths, taking you when you are bowed with comfortable old age, and your people prosperous about you. This that I speak to you is the truth.”

He finished, and I replied, saying: “Teiresias, no doubt the gods, themselves, have spun this fate for me. Come tell me the truth of this now. Here I see my dead mother’s ghost: she sits beside the blood silently, and cannot look on her own son’s face or speak with him. Tell me, my lord, how she may know it is I.”

Swiftly he answered my words: “It is a simple thing to explain to you. Whoever of the dead departed you allow to approach the blood will speak to you indeed: but whoever you deny will draw back.”’

BkXI:150-224 Odysseus tells his tale: The Spirit of Anticleia

‘With this the ghost of Lord Teiresias, its prophecy complete, drew back to the House of Hades. But I remained, undaunted, till my mother approached and drank the black blood. Then she knew me, and in sorrow spoke to me with winged words: “My son, how do you come, living, to the gloomy dark? It is difficult for those alive to find these realms, since there are great rivers and dreadful waters between us: not least Ocean that no man can cross except in a well-made ship. Do you only now come from Troy, after long wandering with your ship and crew? Have you not been to Ithaca yet, not seen your wife and home?”

To this I replied: “Mother, necessity brought me to Hades’ House, to hear the ghost of Theban Teiresias, and his prophecy. No, I have not yet neared Achaea’s shores, not set foot in my own country, but have wandered constantly, burdened with trouble, from the day I left for Ilium, the city famous for horses, with noble Agamemnon, to fight the Trojans. But tell me now, in truth, what pitiless fate overtook you? Was it a wasting disease, or did Artemis of the Bow attack you with her gentle arrows, and kill you? And what of my father and son I left behind? Does my realm still rest with them, or has some other man possessed it, saying I will no longer return? And tell me of my wife, her thoughts and intentions. Is she still with her son, and all safe? Or has whoever is best among the Achaeans wedded her?”

So I spoke, and my revered mother swiftly replied: “Truly, that loyal heart still lives in your palace, and in weeping the days and night pass sadly for her. No man has taken your noble realm, as yet, and Telemachus holds the land unchallenged, feasting at the banquets of his peers, at least those it is fitting for a maker of laws to share, since all men invite him. But your father lives alone in the fields, not travelling to the city, and owns no bed with bright rugs and cloaks for bedding, but sleeps where serfs sleep, in the ashes by the hearth all winter through, and wears only simple clothes. When summer comes and mellow autumn, then you will find his humble beds of fallen leaves, scattered here and there on the vineyard’s slopes. There he lies, burdened with age, grieving, nursing great sadness in his heart, longing for your return. So too fate brought me to the grave. It was not the clear-sighted Goddess of the Bow who slew me in the palace with gentle arrows, nor did I die of some disease, one of those that often steals the body’s strength, and wastes us wretchedly. No, what robbed me of my life and its honeyed sweetness was yearning for you, my glorious Odysseus, for your kindness and your counsels.”

So she spoke, and I wondered how I might embrace my dead mother’s ghost. Three times my will urged me to clasp her, and I started towards her, three times she escaped my arms like a shadow or a dream. And the pain seemed deeper in my heart. Then I spoke to her with winged words: “Mother, since I wish it why do you not let me embrace you, so that even in Hades’ House we might clasp our arms around each other and sate ourselves with chill lament? Are you a mere phantom royal Persephone has sent, to make me groan and grieve the more?

My revered mother replied quickly: “Oh, my child, most unfortunate of men, Persephone, Zeus’ daughter, does not deceive you: this is the way it is with mortals after death. The sinews no longer bind flesh and bone, the fierce heat of the blazing pyre consumes them, and the spirit flees from our white bones, a ghost that flutters and goes like a dream. Hasten to the light, with all speed: remember these things, to speak to your wife of them.”’

BkXI:225-332 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghosts of Famous Women

‘So we talked together, and then the women, the wives and daughters of heroes came, sent by royal Persephone. A crowd they thronged around the black blood, and I considered how best to question them, and this was my idea: to draw my long sword from its sheath, and prevent them drinking of the blood together. Then each came forward, one by one, and declared her lineage, and I questioned all.

Know then, the first I saw was noble Tyro, who told me she was peerless Salmoneus’ daughter, and wife to Cretheus, Aeolus’ son. She fell in love with the god of the River Enipeus, most beautiful of Earth’s rivers, and used to wander by its lovely waters. But the Earth-Shaker, Earth-Bearer Poseidon, took Enipeus’ form, and lay with her at the eddying river-mouth. A dark wave, mountain-high, curled over them, and hid the mortal woman and the god. There he unclasped the virgin’s girdle, and then he sealed her eyes in sleep. When he had finished making love to her, he took her by the hand, and said: “Lady, be happy in this love of ours, and as the year progresses you will bear glorious children, for a god’s embrace is not without power. Nurse them and rear them, but for now go home and keep silent, and know I am Poseidon, the Earth-Shaker.” With this he sank beneath the surging sea. Tyro conceived, and bore Pelias and Neleus, two mighty servants of great Zeus. Pelias, rich in flocks, lived in spacious Iolcus, while Neleus lived in sandy Pylos. This queen among women bore other children to Cretheus: Aeson, Pheres and Amythaon, filled with the charioteer’s delight in battle.

Next I saw Antiope, Asopus’ daughter, who claimed she had slept with Zeus himself. She gave birth to two sons, Amphion and Zethus, who founded Seven-Gated Thebes, ringing it with walls, since powerful as they were they could not live in a Thebes vast but unfortified.

Then came Alcmene, wife of Amphitryon, who conceived Heracles, lion-hearted, fierce in fight, when she lay in great Zeus’ arms. And I saw Megara, proud Creon’s daughter, who married that same indomitable son of Amphitryon.

Then Oedipus’ mother came, the beautiful Jocasta, who unknowingly did a monstrous thing: she wed her own son. He killed his father and married his mother: only then did the gods reveal the truth. By the gods’ dark design despite his suffering he still ruled the Cadmeans in lovely Thebes, but she descended to the house of Hades, mighty jailor, tying a fatal noose to the high ceiling, hung by her own grief, leaving endless pain for Oedipus, all that a mother’s avenging Furies can inflict.

And lovely Chloris I saw, youngest daughter of Amphion, son of Iasus once the great Minyan King of Orchomenus. Neleus wooing her gave her countless gifts, marrying her because of her beauty: and she was Queen in Pylos. She bore her husband glorious children, Nestor, Chromius, and noble Periclymenus, and the lovely Pero, she a wonder to men, so that all her neighbours tried for her hand, but Neleus would only give her to the man who could drive great Iphicles’ cattle from Phylace: a broad and spiral-horned herd, and hard to drive. The infallible prophet, Melampus, alone, agreed to try, but the gods’ dark design snared him, and the savage herdsmen’s cruel bonds. Only when days and months had passed, the seasons had altered, and a new year came, did mighty Iphicles release him, since he had exhausted all his prophecies, and Zeus’ will was done.

Leda, I saw, Tyndareus’ wife, who bore him those stout-hearted twins, Castor, the horse-tamer, and Polydeuces, the boxer. Though they still live, they have even been honoured by Zeus in the underworld, beneath the fruitful Earth. Each alternately is alive for a day, and the next day that one is dead: they are honoured as if they were gods.

Next I saw Iphimedeia, Aloeus wife, who claimed she had slept with Poseidon. She too bore twins, short-lived, godlike Otus and famous Ephialtes, the tallest most handsome men by far, bar great Orion, whom the fertile Earth ever nourished. They were fifteen feet wide, and fifty feet high at nine years old, and threatened to sound the battle-cry of savage war even against the Olympian gods. They longed to add Ossa to Olympus, then Pelion and its waving woods to Ossa, and scale the heavens themselves. They would have done it too, if they had already reached manhood, but Apollo, Zeus’ son, born of lovely Leto, slew them both, before the down had covered their faces, and their beards began to grow.

And Phaedra too I saw, and Procris, and fair Ariadne, daughter of baleful Minos. Theseus tried to carry her off from Crete to the sacred hill of Athens, but had no joy, for Artemis, warned by Dionysus, killed her on sea-encircled Dia.

And Maera came, and Clymene, and hateful Eriphyle, who sold her own husband’s life for gold.

I cannot count or name all the wives and daughters of heroes I saw there, or all this immortal night would be gone. And it is time for me to sleep, here in the palace, or with my crew by the swift ship. My journey home is in your hands, and in the hands of the gods.’

BkXI:333-384 Alcinous asks Odysseus to continue his narration

So Odysseus spoke. Spellbound at his words, all had fallen silent in the darkened hall. White-armed Arete was the first of the gathering to speak: ‘Phaeacians, what do you think of this man’s looks, his stature, and judgement? He is my guest, as well, though you all share in that honour. So don’t be in a hurry to send him on his way, nor fail in generosity to one who stands in need, for favoured by the gods your homes are full of treasures.’

Then a Phaeacian elder, the aged hero Echeneus, said: ‘Friends, our wise queen’s words are fitting and match our thoughts. Respond to them, though words and actions here are still subject to Alcinous.’

‘Her word is good,’ Alcinous replied, ‘as long as I live and rule the sea-loving Phaeacians. Yet our guest must stay until tomorrow, despite his longing for home, while we add to our gifts. The men shall concern themselves, all of them, with his passage, I most of all, since the power here rests with me.’

Then resourceful Odysseus replied: ‘Renowned Alcinous, my lord, if you further my passage and offer me glorious gifts, though you commanded me to stay, even for another year, I would accept it. It would be better to reach my country with full hands. I would win more honour and love from those who witness my return to Ithaca.’

Again Alcinous spoke: ‘Odysseus, when we gaze at you, we certainly do not think of you as one of those liars and cheats the black earth breeds in such numbers among the ranks of humankind, men who fashion falsehoods out of things beyond experience. You have a wise and eloquent heart, and have told us your adventures and of the Argives’ sad misfortunes with the skilfulness of a bard. But tell me the truth of this, in Hades did you see any of your godlike comrades, warriors who travelled to Troy with you, and met their death there? The night is long, and it cannot be time to sleep yet, not on such a marvellous night as this. Tell me the wondrous things you have done. I could stay awake till shining dawn, listening as long as you are willing to speak of your misfortunes.’

To this resourceful Odysseus answered: ‘Lord Alcinous, most renowned of men, there is a time for words, and a time for sleep. But if you long to hear I cannot refuse to speak of a sadder thing than these, the fate of friends who escaped the dread ranks of the Trojans only to die later, to die on their return through an evil woman’s wiles.’

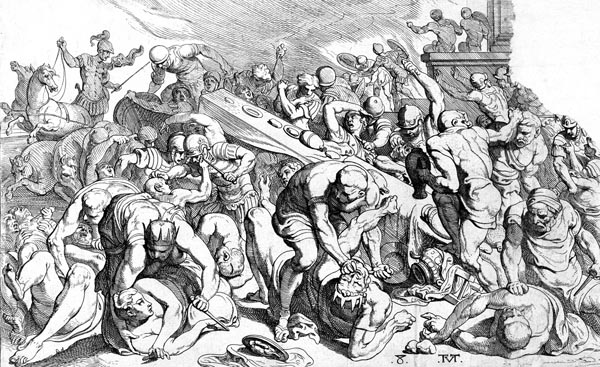

BkXI:385-464 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Agamemnon

‘When sacred Persephone had dispersed the female spirits, the ghost of Agamemnon, son of Atreus, came sorrowing, and other ghosts were gathered round him, those who met their fate alongside him, murdered in Aegisthus’ palace. Drinking the black blood he knew me, and wept loudly, shedding great tears, stretching his hands out in his eagerness to touch me. But all his power and strength was gone, all that vigour his body one possessed.

I wept when I saw him, and pitied him, and spoke to him with winged words: “Agamemnon, king of men, glorious son of Atreus, what pitiless stroke of fate destroyed you? Did Poseidon stir the cruel winds to a raging tempest, and swamp your ships? Or perhaps you were attacked in enemy country, while you were driving off their cattle and fine flocks, or fighting to take their city and its women?”

He answered my words swiftly: “Odysseus of many resources, scion of Zeus, son of Laertes, Poseidon stirred no cruel winds to raging tempest, nor swamped my ships, nor was I attacked in enemy country. Aegisthus it was who engineered my fate, inviting me to his palace for a feast, murdering me with my accursed wife’s help, as you might kill an ox in its stall. I died wretchedly, and round me my companions were slaughtered ruthlessly, like white-tusked swine for a wedding banquet in the hall of some rich and powerful man, or at a communal meal, or a great drinking session. You yourself have witnessed the killing of men, in single combat or in the thick of the fight, but you would have felt the deepest pity at that sight, the floor swimming with blood where our corpses lay, by the mixing bowl and the heavily-laden tables. But the most pitiful cry of all came from Cassandra, Priam’s daughter, whom treacherous Clytemnestra killed as she clung to me. Brought low by Aegisthus’ sword I tried to lift my arms in dying, but bitch that she was my wife turned away, and though I was going to Hades’ Halls she disdained even to close my eyelids or my mouth. Truly there is nothing more terrible or shameless than a woman who can contemplate such acts, planning and executing a husband’s murder. I had thought to be welcomed by my house and children, but she with her mind intent on that final horror has brought shame on herself and all future women, even those who are virtuous.”

‘The murder of Agamemnon and Cassandra’

To this I answered: “Indeed, from the very beginning, Zeus the Thunderer has tormented the race of Atreus, through women’s machinations! So many men died for Helen’s sake while Clytemnestra plotted in your absence.” I spoke, and he made answer swiftly: “So don’t be too open with your own wife, don’t tell her every thought in your mind, reveal a part, keep the rest to yourself. Not that death will come to you from wise Penelope, Icarius’ daughter, she who is so tender-hearted, and circumspect. A newly wedded bride she was when we left for the war, with a baby son at her breast who must be a man now and prospering. His loving father will see him when he returns, and he will kiss his father as is right and proper. But that wife of mine did not even allow me to set eyes on my son before she killed me. Let me say this too, and take my words to heart, don’t bring your ship to anchor openly, when you reach home, but do it secretly, since women can no longer be trusted.

Come tell me, in truth, have you heard if my son is still alive, maybe in Orchomenus or sandy Pylos, or in Menelaus’ broad Sparta: that my noble Orestes is not yet dead?” To this I answered: “Son of Atreus, why ask this of me? I cannot tell if he is dead or living, and it is wrong to utter empty words.”’

BkXI:465-540 Odysseus tells his tale: The Spirit of Achilles

‘So we stood, exchanging words of sadness, grieving and shedding tears. And now the spirit of Achilles son of Peleus appeared, and the spirits of Patroclus and peerless Antilochus, and Ajax who for beauty and stature was supreme among the Danaans, save only for Peleus’ flawless son. And the ghost of swift-footed Achilles, grandson of Aeacus, knew me, and spoke through the tears: “Odysseus of many resources, scion of Zeus, son of Laertes, what could your resolute mind devise that exceeds this: to dare to descend to Hades, where live the heedless dead, the disembodied ghosts of men?”

So he spoke, and I replied: “Achilles, son of Peleus, greatest of Achaean warriors, I came to find Teiresias, to see if he would show me the way to reach rocky Ithaca. I have not yet touched Achaea, not set foot in my own land, but have suffered endless troubles, yet no man has been more blessed than you, Achilles, nor will be in time to come, since we Argives considered you a god while you lived, and now you rule, a power, among the un-living. Do not grieve, then, Achilles, at your death.”

These words he answered, swiftly: “Glorious Odysseus: don’t try to reconcile me to my dying. I’d rather serve as another man’s labourer, as a poor peasant without land, and be alive on Earth, than be lord of all the lifeless dead. Give me news of my son, instead. Did he follow me to war, and become a leader? Tell me, too, what you know of noble Peleus. Is he honoured still among the Myrmidons, or because old age ties him hand and foot do Hellas and Phthia fail to honour him. I am no longer up there in the sunlight to help him with that strength I had on Troy’s wide plain, where I killed the flower of their host to defend the Argives. If I could only return strong to my father’s house, for a single hour, I would give those who abuse him and his honour cause to regret the power of my invincible hands.”

To this I answered: “Truly, I have heard nothing of faultless Peleus, but I can tell you all about Neoptolemus, your resolute son, since you command me. I myself brought him from Scyros, in my well-made hollow ship, to join the bronze-greaved ranks of the Acheans. When we debated our plans before Troy he was always first to speak and his words were eloquent: only godlike Nestor and I were more so. And when we fought with our bronze spears on the plains of Troy, he never lagged behind in the crowded ranks but always advanced far in the lead, yielding to no one in skill. Many were the men he killed in mortal combat. I could not count or name them, all those victims of his, killed as he fought for the Argives, but what a warrior that hero Eurypylus, son of Telephus was, who fell to his sword, and Eurypylus’ Mysian comrades slain around him, all because of a woman’s desire for gain.

Next to noble Memnon, he was the handsomest man I ever saw. Then again, when we Argive leaders climbed into the Horse that Epeius made, and it fell to me to open the hatch of our well-made hiding place, or keep it closed, the other Danaan generals and counsellors kept on wiping the tears from their eyes and their limbs trembled, but he begged me endlessly to let him leap from the Horse, toying with his sword hilt and his heavy bronze spear, eager to wreak havoc on the Trojans. And when we had sacked Priam’s high city, he took ship with his share of the spoils and a noble prize, and never a wound, untouched by the sharp spears, unmarked by close combat, something rare in battle, since Ares, the God of War, is indiscriminate in his fury.”

When I had spoken, the spirit of Achilles, Aeacus’ grandson, went away with great strides through the field of asphodel, rejoicing at my news of his son’s greatness.’

BkXI:541-592 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Ajax and others

‘The other ghosts of the dead departed stood there sorrowing, and each asked me about their dear ones. Only the spirit of Ajax, Telamon’s son, stood apart, still angered over my victory in the contest by the ships, for Achilles’ weapons. Achilles’ divine mother, Thetis, had offered them as a prize, with the Trojan prisoners and Pallas Athene herself as judges. I wish I had never won the reward for that debate, that armour that caused the earth to close over so noble a head as that of Ajax, who in beauty and martial action was supreme among the Danaans, save for that faultless son of Peleus. I spoke to his ghost in calming words: “Ajax, son of faultless Telamon, even in death can you not forget your anger with me, over those fatal weapons? The gods themselves must have cursed the Argives with them. In you a tower of strength was lost to us, and we Achaeans never cease to share as great a grief for you, as we do for Achilles, Peleus’ son. But Zeus alone is to blame whose deadly hatred for the Danaan host hastened your doom. Come closer to me, my lord, so you can hear my speech. Curb your wrath: restrain your proud spirit.”

He chose not to give a single word in answer, but went his way into Erebus to join the other ghosts of the dead departed. For all his anger he might still have spoken to me, or I to him, but my heart desired to see other ghosts of those who were gone.

Know that I saw Minos there, Zeus’ glorious son, seated with the golden sceptre in his hand, passing judgement on the dead as they sat or stood around him, making their case, in the broad-gated House of Hades.

I next saw great Orion, carrying his indestructible bronze club, driving the phantoms of wild creatures he once killed in the lonely hills over the fields of asphodel.

‘Odysseus in the Underworld’

I saw Tityos, son of glorious Gaea, spread out over a hundred yards of ground, while a vulture sat on either side tearing his liver, plucking at his entrails, his hands powerless to beat them away. He is punished for his rape of Leto, Zeus’ honoured consort, as she journeyed to Pytho through lovely Panopeus.

I saw Tantalus in agonising torment, in a pool of water reaching to his chin. He was tortured by thirst, but could not drink, since every time he stooped eagerly the water was swallowed up and vanished, and at his feet only black earth remained, parched by some god. Fruit hung from the boughs of tall leafy trees, pears and pomegranates, juicy apples, sweet figs and ripe olives. But whenever the old man reached towards them to grasp them in his hands, the wind would sweep them off into the shadowy clouds.’

BkXI:593-640 Odysseus tells his tale: The Ghost of Heracles and others

‘And I saw Sisyphus in agonising torment trying to roll a huge stone to the top of a hill. He would brace himself, and push it towards the summit with both hands, but just as he was about to heave it over the crest its weight overcame him, and then down again to the plain came bounding that pitiless boulder. He would wrestle again, and lever it back, while the sweat poured from his limbs, and the dust swirled round his head.

Then I caught sight of mighty Heracles, I mean his phantom, since he joys in feasting among the deathless gods, with slim-ankled Hebe for wife, she the daughter of great Zeus and golden-sandalled Hera. Round Heracles a clamour rose from the dead, like wild birds flying up in terror, and he dark as night, his bow unsheathed and an arrow strung, glared round fiercely as if about to shoot. His golden shoulder-belt was terrifying too, where marvellous things were wrought, bears, wild boars, lions with glittering eyes, battle and conflict, murder and mayhem. I hope that whatever craftsman retained the design of that belt he never made another, and never will.

When he saw me, he in turn knew me, and weeping spoke in winged words: “Odysseus of many resources, scion of Zeus, son of Laertes, wretched spirit are you too playing out your evil fate such as I once endured under the sun? A son of Zeus, Cronos’ son, I still suffered misery beyond all measure, since I served a man far inferior to me, and he set me difficult tasks. He even sent me here to bring back the Hound of Hades, unable to think of a harder labour. I carried off the creature too, and led him away. Hermes and bright-eyed Athene were my guides.”

With this he departed into Hades’ House, but I stood fast, hoping some other heroic warrior of ancient times might still appear. And I might have seen those men of the past I longed to see, Theseus and Peirithous, bright sons of the gods. But long before that the countless hosts of the dead came thronging with eerie cries, and I was gripped by pale fear lest royal Persephone send up the head of that ghastly monster, the Gorgon, from Hades’ House.

So I hastened to the ship, and ordered my friends to embark, and let loose the cables. Swiftly they climbed aboard, and took their seats at the oars, and as we rowed the force of the current carried her down the River of Ocean, till afterwards a fair breeze blew.