Homer: The Iliad

Book IV

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk IV:1-67 Hera prolongs the War

- Bk IV:68-126 Athene stirs Pandarus to action

- Bk IV:127-197 Menelaus is wounded

- Bk IV:198-249 Agamemnon rouses the generals

- Bk IV:250-325 Agamemnon meets Idomeneus, the Aiantes, and Nestor

- Bk IV:326-421 Agamemnon meets Menestheus, Odysseus and Diomedes

- Bk IV:422-472 The death of Echepolus

- Bk IV:473-544 The thick of battle

BkIV:1-67 Hera prolongs the War

The gods, meanwhile, were gathered with Zeus on the golden council-floor, drinking toasts of nectar from gleaming cups that lovely Hebe filled while they gazed down on Troy.

Cronos’ son was swift to taunt Hera with mocking words, and said slyly: ‘Menelaus has two goddesses to aid him, Hera of Argos and Alalcomenean Athene. But while they sit here only looking on, laughter-loving Aphrodite stands by him and shields him from fate. Now she saves him when he thought to die. Yet surely Menelaus, beloved of Ares, won the duel, so let us decide what to do; whether to stir harsh war and wake the noise of battle, or seal a pact of friendship between these foes. If that were good and pleasing to all, king Priam’s city might stand and Menelaus take back Argive Helen.’

Athene and Hera murmured at his words, where they sat together plotting disaster for Troy. Athene, it’s true, bit her tongue, and despite the fierce fury gripping her, and anger at Father Zeus, stayed silent, but Hera could not contain herself: ‘What’s this you say, dread son of Cronos? Will you render my efforts null and void, all the toil and sweat I’ve suffered, wearing out my horses, gathering an army to defeat Priam and his sons? Do as you will, but be clear the rest of us disagree.’

Zeus, the Cloud-Gatherer was troubled: ‘My Queen, how have Priam and his sons harmed you that you work so fervently to sack the high citadel of Ilium? Will nothing sate your anger but to shatter the gates and the great walls, and consume King Priam, his sons, and nation? Well then, do as you wish, so it ceases to be a source of strife between us. But I tell you this, and keep it well in mind, whenever I choose in my zeal to sack some city dear to you, keep clear of my wrath, and let me have my way, as I agree now to yield to you, though my heart wills otherwise. For of all the cities beneath the sun and stars, that mortal men have made to dwell in, sacred Troy is dearest to me, as are Priam and his people of the strong ashen spear. Never at their feasts did my altar lack its share of wine and burnt flesh, those offerings that are the gods’ privilege.’

And Hera, the ox-eyed heavenly queen replied: ‘There are three cities dearest to me; Argos, Sparta and broad-paved Mycenae; if they rouse your hatred, ruin them. I’ll not shield them, nor hold a grudge. And if I did, you are the stronger: I would achieve nothing by trying. Yet my efforts must not be mocked, for I too am divine and born of the same stock as you, since Cronos, crooked in counsel, begot me, the most honoured of all his daughters, twice so being the eldest and your wife, you who are king of all the gods. Yet let us bow to each other in this, I to you, and you to me, and all the other deathless gods will follow. Command Athene to visit the Greek and Trojan battle lines, and make sure the Trojans are first to break the truce by attacking the triumphant Greeks.’

‘Hera in conversation with Zeus’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

BkIV:68-126 Athene stirs Pandarus to action

At this, the father of men and gods obeyed, swiftly repeating her words, rousing the eager Athene, who darted from the peak of Olympus, like a glistening meteor shedding the sparks that Zeus sends as a warning to sailors or to some great army. She flew to Earth, and landed in their midst, awing those who saw, both the bronze-greaved Greeks and the Trojans, the horse-tamers; so that men turned to each other saying: ‘Does Zeus mean harsh war and the call to battle, or a pact of friendship between foes, for he dispenses peace and war.’

While they murmured, she entered the Trojan ranks, disguised as the mighty spearman Laodocus, Antenor’s son, searching for godlike Pandarus. She found that great and peerless son of Lycaon, where he stood surrounded by the strong force of warriors who had followed him from the banks of Aesepus. Approaching, she spoke her winged words: ‘Would you hear my advice, warlike son of Lycaon? Aim a swift arrow at Menelaus, win glory and renown among the Trojans, and please Prince Paris most of all. He would be first to load you with fine gifts if he saw Menelaus, Atreus’ brave son, felled by your shaft and laid on the funeral pyre. Come, shoot at glorious Menelaus, and vow to Lycian Apollo, lord of the bow, a great sacrifice of firstling lambs when you are home again in holy Zeleia.’

So she spoke, and swayed his foolish heart. Swiftly he took his bow made from the polished horns of a wild ibex, shot beneath the chest as it came from behind a rock where he lay in wait, so that it tumbled backward into a cleft. The horns of sixteen hands the artisan had skilfully joined together, carefully smoothing the bow and tipping it with gold. Now he set it firmly against the ground, and strung it, while his noble friends hid him with their shields, lest the Greeks should rise to their feet before Menelaus could be hit. Then he opened his quiver and took a new-feathered arrow, darkly freighted with pain, swiftly fitted the bitter shaft to the string, and vowed to Lycian Apollo, lord of the bow, a great sacrifice of firstling lambs once he was home again in holy Zeleia. Gripping the notched arrow and the ox-gut string he drew it back to his chest till the iron point was against the bow, and bending the great bow in a curve, it twanged, the string sang out, and the keen arrow leapt, eager to wing its way towards the foe.

BkIV:127-197 Menelaus is wounded

But the blessed and deathless gods did not forget you, Menelaus, Athene, above all, Zeus’ warrior daughter, shielded you, warding off the bitter dart, turning it aside at the last moment, as a mother brushes a fly away from her sweetly sleeping child. She deflected it to where your belt’s golden buckles met, where the double corselet overlapped. The sharp arrow drove through the embossed belt, on through the elaborate corselet, and the armoured apron protecting the flesh, a last and main defence against missiles; piercing that too. So the dart cut the skin, and instantly dark blood poured from the wound.

As a woman of Maeonia or Caria stains a slice of ivory, scarlet, to make a cheek-piece for a horse, an ornament to be kept in a treasure chamber, coveted by many riders, destined for a king’s delight and doubly so, to adorn his steed, and as a badge of honour; so your thighs, Menelaus, were stained with blood, your fine thighs, and legs, right down to your ankles.

Then Agamemnon, lord of men, shuddered, seeing the dark blood flow from the wound, and Menelaus, beloved of Ares, blenched likewise, but finding the arrow-head and its binding had failed to penetrate, his heart grew calm. Nevertheless the king grasped his hand, and groaning heavily among his groaning companions, said: ‘Was it your death, then, I caused by swearing this truce, sending you out alone to fight the Trojans, who in wounding you have trampled their solemn oaths underfoot? Yet an oath over clasped hands, with the blood of lambs, and offerings of pure wine, is a thing not so easily annulled. Though Zeus delays punishment, he will punish fully in the end: the oath-breakers will pay with their lives, and their wives and children too. My heart and mind know well, that holy Troy will be razed, in time; and Priam, and his people of the strong ash spear, brought low; and the sky-dwelling son of Cronos, enthroned on high, will wave his dark aegis over them in anger at this deceit. It shall come to pass. But Menelaus if you died, if that was your present fate: what dreadful sorrow would be mine. With what shame I would sail for parched Argos, since the Greeks would instantly yearn for home, while Argive Helen would remain for Priam and the Trojans to boast of. Your bones would rot in Trojan ground, with your task undone, and braggarts stamp on the tomb of great Menelaus, crying: ‘May all Agamemnon’s quarrels end like this, a fruitless campaign, a swift return to his homeland empty-handed, while the noble Menelaus here is left behind.’ That’s what they’d say, and on that day may earth open and swallow me.’

But red-haired Menelaus comforted him: ‘Be calm, and say nothing to worry to men. The bright arrow missed my vital parts, stopped by the metal belt, my corselet and the apron fashioned by coppersmiths.’ ‘Let us hope so, dear Menelaus’ Agamemnon replied. ‘But our physician must see the wound and treat it with herbs to ease the sharp pain.’

With that he called his noble herald, Talthybius: ‘Go quick as you can, Talthybius, and bring Machaon, son of that great healer Asclepius. He must attend to brave Menelaus. Some Trojan or Lycian, expert with the bow, has struck him with a dart, to their glory and our sorrow.’

BkIV:198-249 Agamemnon rouses the generals

The herald diligently obeyed his words, and made his way among the bronze-clad Achaean warriors, searching for Machaon. He saw him surrounded by the mighty ranks of shield-bearers, the men who had followed him from Tricca, the horse pasture. Reaching him he spoke these winged words: ‘Come, son of Asclepius, King Agamennon calls you to tend to our great leader Menelaus, for some Trojan or Lycian, expert with the bow, has struck him with a dart, to their glory and our sorrow.’

His summons roused the healer, and they threaded the serried ranks of the Greeks till they came where red-headed Menelaus lay, with the generals gathered round him. Godlike Machaon knelt in the centre, and swiftly extracted the shaft from the tightly-clasped belt, breaking the sharp barbs. Then he loosed the gleaming belt, the corselet and the apron fashioned by coppersmiths. When he had found the place the sharp arrow had pierced, he sucked the blood and skilfully applied soothing herbs, which kindly Cheiron had once given to his father.

While he was tending to Menelaus of the loud war-cry, the ranks of Trojan warriors advanced, and the Greeks donned their battle gear and turned to thoughts of battle.

Noble Agamemnon showed no reluctance, no cowardice or hesitation, only eagerness for the fight where men win glory. He eschewed his bronze-inlaid chariot and its snorting team, which his squire, Eurymedon, son of Peiraeus’ son Ptolemy, restrained, though the king commanded him to have them near at hand lest he wearied as he did his rounds, and ranged on foot through the ranks giving out his orders. Whichever of the Greeks he saw, with their swift horses, eager to do battle, he went to and encouraged, crying: ‘Argives, stoke your fiery courage, Father Zeus never aids the oath-breaker. Those who first turned to violence in breach of the truce, the vultures will tear their tender flesh, and we will sail away with their dear wives and children, when we have razed their citadel.’ But those he saw hanging back from the bitter fight, he rebuked fiercely with angry words: ‘You Greeks, brave only with the bow, aren’t you ashamed? Like deer that scatter over the plain then wearied halt, drained of spirit, you stand there dazed, far from the battle. Will you wait till the Trojans threaten your long-stemmed ships by the grey seashore, hoping that Zeus will extend his arm to defend you?’

BkIV:250-325 Agamemnon meets Idomeneus, the Aiantes, and Nestor

So he ranged through the ranks giving his orders, and as he did so he reached the Cretan warriors, gathered round warlike Idomeneus, arming for the fight. Idomeneus, brave as a wild boar, was at the front, while Meriones urged on the rear. Agamemnon rejoiced at the sight of them, and spoke courtly words to Idomeneus: ‘Above all the Greek horsemen, my lord, I honour you, on and off the field, as I do at the feast when the Argive generals drink the elders’ deep-red wine. Though the rest of the long-haired Achaeans drink their given portion, your cup, like mine, is ever-brimming for you to drain at will. Now rouse yourself to battle, and prove again the warrior you say that you once were.’

‘Son of Atreus,’ the Cretan leader answered: ‘I shall stand a friend to you, as I promised at the outset, when I gave you my pledge; go, urge all the long-haired Achaeans to prompt action, for the Trojans have broken the truce. Doom and woe shall be their fate, since they first turned to violence in breach of their oaths.’

Atreides passed on, gladdened by his words, and among the throng found Ajax the great and Ajax the lesser arming for the fight, with a host of warriors round them. Just as when a goatherd from some high point sees a cloud driven by a west wind looming over the sea, black as pitch in the distance and bringing a mighty storm, such that he shudders at the sight and herds his flock into a cave; so the dense dark battalion of young warriors, beloved of Zeus, bristling with shields and spears, readied themselves for war. King Agamemnon rejoiced at the sight, and spoke to them winged words: ‘Aiantes, you generals of the bronze-clad Argives need no urging, and no orders, since of your own account you drive your men fiercely to battle. By Father Zeus, and Athene and Apollo, I would such courage as yours were in each man’s heart, then Priam’s city would soon be humbled, captured and sacked at our hands.’

With this, he left them there, and passed on to Nestor, the clear-voiced orator of Pylos, marshalling his forces there, and rousing them to fight behind mighty Pelagon, Alastor, Chromius, Prince Haemon, and Bias leader of men. He ranked the charioteers, their chariots and horses, in front, and the bulk of brave infantry behind to act as a bulwark, while the lesser men he set in the centre, so even the shirkers would be forced to fight. His first orders were to the charioteers whom he ordered to curb their teams and not get involved with the masses: ‘Let no man be over-eager, trusting in courage and skill to break ranks and challenge the Trojans alone, but let him not lag behind either, since that weakens the force. But no man can do wrong who lays his chariot alongside that of a foe, and tries for a spear-thrust. Such was the courage and will of the men of old who stormed walls and laid waste cities.’

So the old warrior, with his experience of ancient battles, urged them on, and Agamemnon rejoiced at the sight of him, and spoke these winged words: ‘I trust that your limbs obey your heart, and your strength holds firm, my aged lord, but time’s evils weigh on you. I wish that some other warrior might bear your years, and you take your place among the youth.’

‘Son of Atreus,’ Nestor the Gerenian horseman answered, ‘I too would wish to be the man I was when I once slew brave Ereuthalion. But the gods do not grant men all their gifts at once. I was a young man then, and now the years weigh on me. Yet even so I will be amongst the charioteers, urging them on with words and counsel, since that is the privilege of age, Let men younger than I wield their spears, who in their youthfulness are certain of their strength.’

BkIV:326-421 Agamemnon meets Menestheus, Odysseus and Diomedes

Agamemnon left, gladdened by his words, and passed on to Menestheus, tamer of horses, the son of Peteos, who stood among the Athenians, famed for their battle-cry. Nimble-witted Odysseus, with his mighty Cephallenians, stood nearby at ease, since they had not yet heard the call to battle, the Greek and Trojan regiments being scarcely on the move, and waited to fight when some other battalion of the Achaeans began the advance. Seeing this, the king rebuked them: ‘Why do you cower there, waiting on others, Menestheus, son of a royal father beloved of Zeus, and you who excel in guile, Odysseus, master of the cunning stratagem? You should take your stand by rights at the forefront of fierce battle. You are ready enough to respond to my call for a feast, when we Achaeans celebrate the generals, happy enough to swallow meat and swill the honeyed wine all night. Yet now you’d watch while ten battalions of Greeks wield the pitiless bronze.’

Wily Odysseus replied with a dark look: ‘What’s that you say, Atreides? Is it we who hold back from the fight when Greeks and Trojans meet? If you care to watch, you’ll see dear Telemachus’ father challenge the foremost ranks of these horse-taming Trojans. Your speech meanwhile is empty as the wind.’

King Agamemnon, hearing his anger, spoke winningly in apology: ‘Zeus-born son of Laertes, wily Odysseus, you’ll hear no more rebukes, and no commands from me, since I know that inwardly your thoughts accord with mine. Come, I’ll make good later any harsh words I’ve said, and may the gods erase them.’

So saying he left them there and passed on to great-hearted Diomedes, Tydeus’ son, standing by his well-made chariot, with Sthenelus, Capaneus’ son, at his side. Seeing this, the king rebuked them too: ‘What the son of fierce Tydeus, the horse-tamer, hesitating here, watching the sway of battle? Your father never wavered, that’s for certain: all those who saw him in the thick of war say he was ever in the vanguard. I never met him nor was witness, but they say he was superb. He came to Mycenae once, no enemy but our guest, with noble Polyneices, raising an army to lay siege the sacred walls of Thebes, and they begged us to ally ourselves, win glory. Mycenae was minded to agree, and was on the point of doing so, when Zeus granted inauspicious omens. Leaving, they reached the grassy banks of Asopus, dense with reeds, where the Achaeans sent Tydeus forward on a mission to Thebes. There he found a host of Cadmeians feasting in mighty Eteocles’ palace. Though he was a stranger and alone among the Cadmeian throng, Tydeus the horse-tamer was unafraid. He challenged them to trials of strength and, with Athene’s aid, won every bout with ease. But, angered, the horse-driving Cadmeians, set an ambush as he returned – fifty men led by Maeon, godlike Haemon’s son, and Polyphontes, son of the steadfast Autophonus. Tydeus though dealt them a fateful blow, killing all but one, whom he sent on his way. That was Aetolian Tydeus, yet his son’s not his equal in battle, however fine he may seem in the assembly.’

Great Diomedes, accepting this rebuke from the king he revered, said not a word, but noble Capaneus’ son, was quick to reply: ‘Atreides, no untruths now, since you know what true speech is. We consider ourselves far better men than our sires. We captured seven-gated Thebes, with less of a force against stronger defences, trusting in Zeus and the gods’ omens, while our sires came to grief through their own presumption. So don’t raise our fathers to the same level as us.’

BkIV:422-472 The death of Echepolus

‘Hush, my friend, pay heed to what I say,’ Diomedes intervened, with an angry glance at Sthenelus, ‘I’ll not fault Agamemnon, king of men, for urging the bronze-greaved Greeks on to battle. Glory will be his if the Achaeans win, and raze sacred Ilium, but his will be the pain if we Achaeans lose. Let us, rather, turn our thoughts to acts of conspicuous bravery.’

So saying, fully-armoured, he leapt down from his chariot, and the bronze at his breast rang so loud even the stoutest heart might well have trembled.

Now, as the sea-swell beats on the sounding shore, wave on wave driven before the westerly gale, each crest rising out of the depths to break thundering on the beach or rearing its head to lap the headland and spew out briny foam, so the Danaan ranks advanced, battalion on battalion, remorselessly into battle, while the captains’ voices rose in command as the men marched on in silence, as if that moving mass lacked tongues to speak, mute as they were, fearful of their generals, while on every man the inlaid armour glittered. But the Trojan clamour rang out from their ranks, like the endless bleating of countless ewes in a rich man’s yard, there to yield their white milk, when they hear the cries of their lambs, for the Trojan army, gathered from many lands, lacked a common language, speaking a myriad tongues.

Ares urged on the Trojans, bright-eyed Athene the Greeks, and Terror, Panic, and Strife were there, Strife the sister and ally to man-killer Ares, she whose anger never ceases, who barely raises her head at first, but later lifts it to the high heavens though her feet still trample the earth. Now she brought the evil of war among them, as she sped through the ranks, filling the air with the groans of dying men.

So they met in fury with a mighty crash, with the clash of spears, shields-bosses, bronze-clad warriors, till the last moans of the fallen mingled with the victory cries of their killers, and the earth ran red with blood. Like the sound a shepherd deep in the mountains hears; the mighty clash of two wintry torrents that pour down from high sources to their valleys’ meeting place in a deep ravine; such was the tumult raised by those armies toiling together in battle.

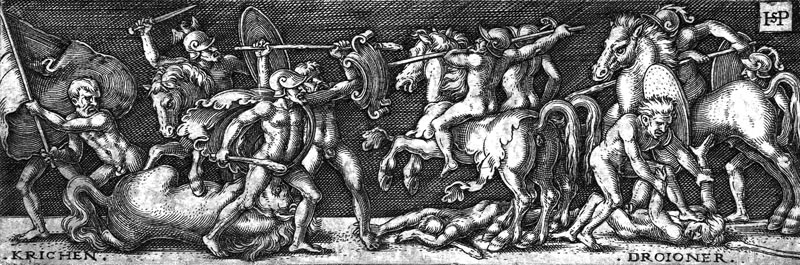

‘Battle between the Greeks and the Trojans’ - Hans Sebald Beham, 1510 - 1550

Of the Trojans, noble Echepolos, son of Thalysius, was first to die, fighting in the vanguard, downed in his armour by Antilochus. The spear struck the ridge of his horse-hair crested helmet, and the point drove through the skin of his forehead into the bone. Darkness filled his eyes, and he dropped like a fallen tower on the field. Once downed, Elephenor, son of Chalcodon, prince of the fierce Abantes, seizing him by the feet, tried to drag his body out of range, ready to strip it swiftly of armour; yet not for long, for brave Agenor saw him drag the corpse aside, and with a thrust of his bronze-tipped spear, striking him in the flank exposed by his shield as he stooped, loosened all his limbs. His spirit fled, and the Greeks and Trojans struggled grimly over the corpse. They leapt at one another like wolves, and staggered locked in each other’s fierce embrace.

BkIV:473-544 The thick of battle

Now Telamonian Ajax felled Simoeisius, Anthemion’s strong young son, who took his name from the River Simois, beside which he was born as his mother returned from Mount Ida, where she had gone with her parents to tend sheep. He failed to repay his parents for all their loving care, brief was his span of life, slain by great Ajax’s spear. As he marched in the vanguard the point pierced his right nipple, exiting through the shoulder. He toppled to the ground, like a smooth poplar with arching branches flourishing in the water-meadows, that a wheelwright fells with his bright axe to craft fine rims for chariot wheels, and leaves to season by the river bank. So did noble Ajax slay Simoeisius Anthemion’s son.

Then Priam’s son, Antiphus of the glittering cuirass, replied with a spear-throw from the ranks. He missed Ajax, but struck Odysseus’s loyal comrade Leucus in the groin as he was hauling Simoeisius away. As he fell, the body slipped from his grasp landing beneath him. Odysseus was enraged by his death, and rushed from the ranks towards the enemy, clad in his burnished bronze. There, after an appraising glance, he hurled his bright spear, so that the Trojans shrank back from his onset. His shaft was not cast in vain, striking Democoon, Priam’s natural son, who had rallied to the cause from his stud-farm and swift-hoofed mares at Abydus. The spear, hurled in anger at a comrade’s death, struck him on one temple, the bronze point exiting through the other so that darkness dimmed his eyes, and he fell with a thudding clang of armour. Great Hector and the Trojan front gave ground, while the Greeks, shouting in triumph, dragged the bodies clear and advanced.

Indignation filled Apollo, gazing down from Pergamus. He called to the Trojans: ‘Drive on horse-tamers, win back your ground; these Greeks are not made of stone or iron: their flesh too will bleed if the sharp bronze strikes. And Achilles, blonde-haired Thetis’ son, he’s out of the fight, away by the Argive ships nursing his bitter anger.’ So the dire god shouted from their citadel, yet the Greeks were urged on by Zeus’ daughter, Athene Tritogeneia, who strengthened the ranks wherever they looked like giving way.

Now, Diores, Amarynceus’ son, was caught in the net of fate, struck on the right ankle by a jagged stone. Peiros of Aenus Imbrasus’ son threw it, leader of the Thracians, and the relentless missile crushed the bones and sinews. Stretching his arms out to his friends, Diores fell backward in the dust, gasping away his life, while Peiros followed up his throw by skewering him with a spear near the navel, till his entrails spilled out on the ground, and darkness filled his eyes.

Yet as Peiros sprang away, Aetolian Thoas speared him in the chest above the nipple, so the bronze point fixed in his lung, then closing, dragging the great spear from the flesh, drawing a sharp blade he struck him in the belly to end his life. Still he was denied the armour. Peiros’ comrades, Thracians sporting topknots, grasped their long spears tightly and though he was tall, strong and threatening, thrust him back till he staggered and gave ground.

So, in the dirt they lay beside each other, among the host of dead, Peiros the Thracian general, and Diores leader of the bronze-clad Epeians. That was no skirmish to make light of, as some unwounded warrior might whom Pallas Athene led into battle, shielding him from the hail of missiles and all the sharp sword-thrusts, for a host of Greeks and Trojans lay there on that day, stretched out side by side, their faces in the dust.