Homer: The Iliad

Book XIX

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XIX:1-73 Achilles ends his quarrel with Agamemnon

- Bk XIX:74-144 Agamemnon speaks of Ate

- Bk XIX:145-237 Odysseus gives his advice

- Bk XIX:238-281 The Greeks sacrifice to the gods

- Bk XIX:282-337 Achilles grieves for Patroclus

- Bk XIX:338-424 Achilles arms for battle

BkXIX:1-73 Achilles ends his quarrel with Agamemnon

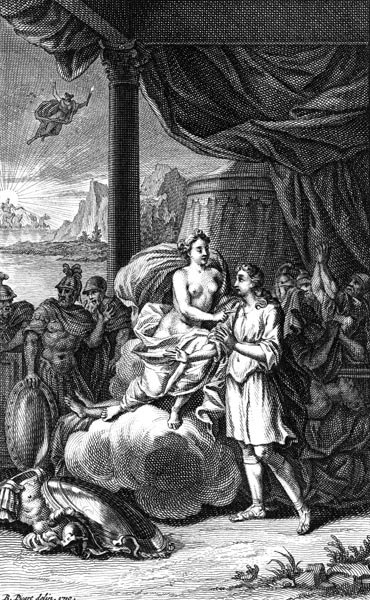

As Dawn, in saffron robes, rose from the stream of Ocean, bringing light to gods and men, Thetis reached the ships bearing Hephaestus’ gift. She found her beloved son groaning aloud, his arms round Patroclus’ body, while his men stood by, weeping bitterly. The shining goddess came and took his hand, saying; ‘My child you must let him go, however great your sorrow, and leave him here, dead for all time, slain by the will of heaven. Now, take up instead Hephaestus’ marvellous armour, more beautiful than any that ever adorned a man’s shoulders.’

The goddess set the armour down before him, and it rang aloud in its splendour. Then the Myrmidons were seized with awe, and none dared look on it, but shrank away. But the more Achilles gazed, the greater rose his desire for vengeance, and his eyes flashed terribly, like coals beneath his lids, as he lifted the god’s marvellous gifts and exulted. When he had looked his fill on their splendour, he spoke to Thetis winged words; ‘Mother, the god grants me a gift fit for the immortals, such as no mortal smith could fashion. Now I shall arm myself for war. Yet I fear lest flies infest the wounds the bronze blades made, and maggots breed in the corpse of brave Patroclus, and now his life is fled, rot the flesh, and disfigure all his body.’

‘Thetis gifts Achilles new armour’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

But silver-footed Thetis, the divine, replied: ‘Fear not, my son, I will defend it from the mass of fierce insects that feed on men who die in battle. Though he lie here a year, his flesh will be sound, even sounder than it is now. Now call the Achaeans to assembly, and end your quarrel with the king, arm for war, and summon all your valour.’ So saying, she filled his limbs with strength, his heart with courage.

Then she infused ambrosia and amber nectar through the nostrils into the corpse, so that Patroclus’ flesh might be preserved, while noble Achilles strode along the seashore, giving his war-cry, rousing the Achaeans. Now he had appeared, after his long absence from the bitter fight, even those who normally kept to the ships, the pilots, helmsmen and stewards, flocked to the assembly. Diomedes, the steadfast, and noble Odysseus, those servants of Ares, came limping, leaning on their spears, still suffering from their wounds, to sit at the front of the gathering, while last of all came the wounded Agamemnon, hurt by Coön, Antenor’s son, in battle, with a thrust of the bronze-tipped spear.

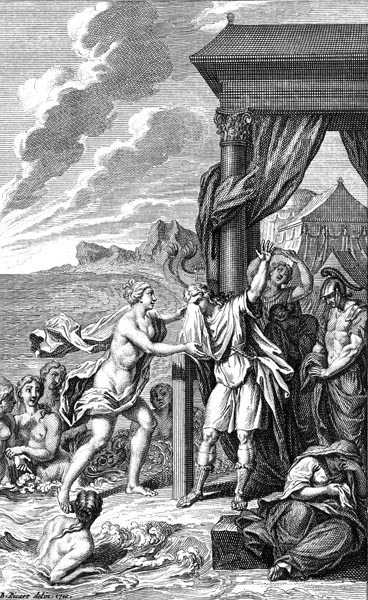

When all the Greeks had gathered, fleet-footed Achilles rose to speak: ‘Son of Atreus, was it good for us to quarrel in this sad way, and eat our hearts out over a girl? I had rather Artemis had fired an arrow and killed her, when I sacked Lyrnessus and took her as mine! Then fewer Greeks would have filled their mouths with the dust of this wide earth, slain by the Trojans while I nursed fierce anger. The Achaeans will long remember our quarrel that only aided Hector and his men. But these things are past and done for all our sorrow, and we must quell the anger in our hearts. My wrath is at an end, I’d not prolong our dispute endlessly. Come, rouse the long-haired Greeks to war, so I may attack these Trojans and try their mettle once more, and see if they still dare to camp by the ships tonight. Many I think, will be glad to escape my spear and the pain of war, and sink to their knees, alive, and rest.’

‘Achilles and Agamemnon are reconciled’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

BkXIX:74-144 Agamemnon speaks of Ate

The bronze-greaved Greeks were delighted by his speech, overjoyed that Peleus’ great son had renounced his anger. King Agamemnon, sitting, due to his wound, rather than standing to address them, now had his say: ‘My friends, Danaan warriors, servants of Ares, it is good to grant a speaker an uninterrupted hearing, interruptions trouble even the skilled orator. And how can anyone speak or hear in a babble of noise? Even the clearest voice would go unheard. What I say is aimed at the son of Peleus, but you other Argives should listen and take note.

You Achaeans have often criticised me as he has done, but the fault was not mine. Zeus, Fate, and the Fury who walks in darkness are to blame, for blinding my judgement that day in the assembly when on my own authority I confiscated Achilles’ prize. What choice did I have? There is a goddess who decides these things, Ate, Zeus’ eldest daughter, blinds us all, accursed as she is. Those tender feet of hers never touch the ground, but pass through men’s minds causing harm, ensnaring this one or another.

Even Zeus they say was blinded by her once, though he’s supreme among gods and men. Hera it was, a mere woman, cunningly tricked him, when Alcmene was due to bear the mighty Heracles in turreted Thebes. Zeus had made a proud boast to the immortals: ‘Listen, gods and goddesses, while I speak what my heart prompts. This very day Eileithyia, goddess of childbirth, will bring a boy-child into the world, born of a race descended from me, who will hold power over all his neighbours. Then it was Queen Hera showed her cunning: ‘As usual, you’ll play the deceiver, and nothing will come of your words. So then, Olympian, give us instead your solemn oath that the man, born of your stock, who issues from between a woman’s thighs today, will indeed hold power over all his neighbours.’ Zeus, misled by her cunning, in his blindness swore a mighty oath. Then Hera darted swiftly from high Olympus to Argos in Achaea where she knew that Nicippe, noble wife of Sthenelus, Perseus’ son, was seven months pregnant with a boy-child. Hera induced the child prematurely, while restraining the Eileithyiae, and delaying Alcmene’s labour. Then she told Zeus, son of Cronos, the news: ‘Father Zeus, lord of the lightning-flash, a word with you. That mighty man is born indeed who shall rule the Argives, fitting, truly, for a child of your lineage. It is Eurystheus, a boy-child for Sthenelus, Perseus’ son.’ At her words he felt a sharp pain deep in his mind, and in a blaze of anger he at once seized Ate by her gleaming tresses, swearing a mighty oath that she who blinds us all should never again be found on Olympus or in the starry heavens. With that, he whirled her round and flung her from the sky down to the ploughed fields of men below. Zeus would think of her and groan later, whenever he saw his dear son Heracles toiling at Eurystheus’ labours.

I too, when great Hector of the gleaming helm was slaughtering Argives by the sterns of our ships, could not forget that Ate who had blinded me before. But since I was blinded indeed, and Zeus robbed me of my senses, I’ll make amends and compensate you richly. I am ready to offer you all the gifts that noble Odysseus promised when he visited your hut the night before last. So prepare for battle and rouse your men. Or you can wait a little, despite your eagerness for war, if you wish, and my attendants will bring you the gifts from my ship, so you can see I give you what will ease your heart.’

BkXIX:145-237 Odysseus gives his advice

Fleet-footed Achilles replied: ‘Agamemnon, king of men, glorious son of Atreus, grant me your gifts if you wish, as is right, or keep them, it is up to you. But for now let us think of war, it is wrong to waste time in talking, and delay the great work still to do. Let Achilles then be your example as you face the enemy, fighting at the front and slaughtering the ranks of Trojans with his bronze spear.’

Wise Odysseus now disagreed: ‘Godlike Achilles, brave indeed you are, but don’t force the sons of Achaea to fight the Trojans, and battle for Ilium, without food in their bellies. When once the battle is joined, and the god breathes courage into both the armies, we are in for a long struggle. Order the Greeks to eat and drink by their swift ships, to give them strength and heart. No man can fight a whole day through, battling the enemy from dawn to dusk, without sustenance. Though a man’s heart may be filled with eagerness for war, his limbs betray him: hunger and thirst overcome him; and he sinks to the ground as he dashes forward. But full of food and wine, a man can fight all day, heart filled with courage, and his limbs unwearied till battle ends. So dismiss the men and order them to eat. As for the gifts, let King Agamemnon have them brought to the assembly, where all the Greeks can see them, and you can be satisfied. Then let him stand in our midst and swear that he has never bedded the girl, a thing customary between men and women, and do you show graciousness in return. Then let him feast you richly in his hut to make amends, so you may lack nothing that is due you. And Atreides, be more just to others in future, there is nothing wrong with a king making amends, when he has been the first to show anger.’

King Agamemnon replied: ‘Son of Laertes your words please me, since you state the whole thing honestly. I will swear the oath, as my heart prompts me: nor do I perjure myself before heaven in so doing. Let Achilles stay here with you all, despite his eagerness for battle, until I have had the gifts brought here, and sworn the solemn oath. I charge you with this, do you yourself choose some of the best young men in the army and have them bring the gifts from my ship, everything we promised to Achilles when you saw him and the women. And let Talthybius ready a boar, to sacrifice to Zeus and the Sun, here in the camp.’

But swift-footed Achilles still demurred: ‘Agamemnon, king of men, most glorious son of Atreus, it would still be better to do all this when my fury has lessened, and a lull occurs in the fighting. Those whom Hector, son of Priam killed, when Zeus gave him the power, lie there mangled and you both talk of eating! I would rather send the sons of Achaea into battle fasting, and feast at sunset when vengeance is sated. I at least will not eat or drink till then, while my friend lies in my hut, mangled by sharp blades, his feet towards the entrance, his comrades grieving round him. What fills my mind, rather, is the thought of slaughter, of blood and the moans of dying men.’

But nimble-witted Odysseus over-ruled him: ‘Achilles, son of Peleus, you are our finest warrior, finer than I and stronger with the spear, yet in counsel I am your superior, being older and more experienced, so suffer yourself to hear me out. Men are quickly exhausted in a fight, when the bronze blades, like sickles, strew the field with cut straw and yield a bitter harvest, and Zeus who rules war’s reaping holds the balance. You want the Greeks to mourn the dead by starving, when hundreds are killed day after day. When would they ever eat? No, we must bury the dead, weep for a day indeed, but harden our hearts. Those who are left alive by this hated conflict must still eat and drink, so as to fight on, without respite, in this heavy armour. And when the summons comes, let no man hang back, waiting for a second summons, this is it: it will go hard with anyone who stays behind beside the ships. We will advance together, and take the fight to these horse-taming Trojans.’

BkXIX:238-281 The Greeks sacrifice to the gods

So saying, he left for Agamemnon’s hut, taking Nestor’s sons along, with Meges, son of Phyleus, Thoas, Meriones, Lycomedes, son of Creon, and Melanippus. No sooner said than done, the seven tripods, twenty gleaming cauldrons, twelve horses, seven women skilled in fine handiwork, with lovely Briseis, the eighth, were all produced as promised, and Odysseus weighted out twenty talents of gold. Then he led the way while the youths brought the gifts to the assembly. There, Agamemnon rose to his feet, while Talthybius, of godlike voice, stood beside the king, restraining the sacrificial boar. Atreides drew the knife he always carried next to the scabbard of his sword, cut a swatch of hair from the boar’s head, and raised his arms in prayer to Zeus. The Argives listened in silence, as they ought, while Agamemnon prayed, gazing at the sky: ‘I call first on Zeus, highest and best of gods, then on Earth, and Sun, and on the Furies, who punish perjury in the underworld, as witnesses that I never laid hand on the girl Briseis, I never made love to her, and that during her stay in my huts she was left untouched. If a word of this prove untrue, may the gods make me suffer all the retribution they exact from those who take their names in vain.’ With this, he slashed the boar’s throat with the merciless bronze, and Talthybius lifting the carcass, turned, and flung it into the depths of the grey sea as food for fishes.

Now Achilles rose and spoke to the warlike Argives: ‘How great the blindness Father Zeus inflicts on men. Agamemnon could not have roused my anger so, nor would he have taken the girl against my will, if Zeus had not first decided that many Greeks should die. Now let us eat, so we can go to war!’

The troops quickly scattered to their ships, while the brave Myrmidons gathered up the gifts, and led the women to Achilles’ huts, while his noble squires drove the horses in among his own herd.

BkXIX:282-337 Achilles grieves for Patroclus

‘Achilles grieves for Patroclus’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

When Briseis, beautiful as golden Aphrodite, saw the corpse of Patroclus mangled by the bronze blades, she flung herself on the body, shrieking loudly, and tore with her hands at her breasts, her tender neck, and lovely face. And the goddess-like woman wailed in her lament: ‘Patroclus, dear to my heart, when I left this hut you were alive, and now alas I return, prince among men, to find you a corpse. So, evil dogs my steps. I saw the husband, to whom my royal parents married me, lie there, dead, by our city wall, mangled by the cruel bronze, and saw my three beloved brothers meet a like fate. But you dried my tears, when fleet-footed Achilles killed my husband, and sacked King Mynes’ city, saying you would see me wed to Achilles, that he would take me in his ship to Phthia and grant me a marriage-feast among the Myrmidons. You were always gentle with me, now I will mourn you forever.’

So Briseis grieved, and the other women took up her lament; mourning Patroclus, it is true, but also their own sorrows. As for Achilles, the Achaean elders gathered round him begging him to eat, but he groaned and refused: ‘Indulge me, dear friends, don’t ask me to sate my hunger or thirst while I suffer so. I will not break my fast before sunset.’

‘Achilles mourns Patroclus’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

He sent the generals away, except for the Atreidae, noble Odysseus, Nestor, Idomeneus, and the old charioteer Phoenix, who all tried to bring him solace in his deep grief, but he refused to be comforted, longing only to enter the bloody maw of battle. He heaved a heavy sigh, stirred by memory: ‘How often, my unlucky, my beloved friend, you would, swiftly and deftly, serve up a savoury meal for us in our hut, when we Greeks were about to attack the horse-taming Trojans. Now you lie here mangled, while I, consumed by grief, lack the heart to eat or drink, though the food is ready and to hand. What worse could I suffer: news of my father’s death? He, alive in Phthia, sheds tears no doubt for his absent son, warring far off in an alien land, battling with Trojans over wretched Helen. Or news of my dear son’s death, assuming he still lives, godlike Neoptolemus, who is growing up in Scyros? I liked to think that I alone would die here, in the land of Troy, far from the horse-pastures of Argos, and that you would be the one to return to Phthia, and fetch my son home with you from Scyros in a swift, black ship, and show him all his inheritance, my goods, my slaves, my great high-roofed halls. For Peleus, I thought, would either be dead by then, or too feeble, weighed down by the hated burden of old age, and the pain of waiting for the sad news of my death.’

BkXIX:338-424 Achilles arms for battle

As he lamented, the generals groaned in sympathy, each filled with memories of home, and Zeus, who saw them grieving, pitied them, and spoke swiftly to Athene: ‘My child, have you forgotten Achilles, your favourite, are your thoughts wholly elsewhere? There he sits by the curved ships grieving for his friend, feeling no hunger, refusing to eat, while his comrades dine. Go and infuse some nectar and sweet ambrosia into him, and save him from starvation.’

Athene scarcely needed prompting, and roused by his words she swooped down from the sky, like a long-winged falcon shrieking through the air. While the whole Greek army prepared for battle, she infused Achilles’ breast with nectar and sweet ambrosia, then returned to her almighty Father’s halls, as the Achaean host advanced from the shore.

Thick and fast as the snowflakes, on the blast of some northerly gale, sent by Zeus himself through the cold bright sky, so the gleaming helms, bossed shields, massive breastplates, and ash spears poured from the ships. The glittering of armour lit the sky, earth shone with the glow of bronze, while the ground rang to the sound of marching men.

In their midst, Achilles armed for battle. His heart filled with unbearable grief, he gnashed his teeth, eyes blazing like fire, and in his fierce anger against Troy he donned the gifts of divine Hephaestus’ toil. First he clasped the fine greaves, with silver ankle-pieces, round his legs. Next he strapped on the breastplate, and slung the silver-studded bronze sword across his shoulders. Then he grasped the great solid shield that shone like the moon from afar. Like the glow of a blazing fire from a lonely upland farm seen by sailors whom a storm drives over the plentiful deep far from their friends, so from Achilles’ splendid richly-ornamented shield the sheen rose to heaven. He lifted the massive horse-hair crested helmet and placed it on his head, where it shone like a star, and above it the golden plumes danced, that Hephaestus had set thickly round the crest. Noble Achilles then flexed the armour to check that it fitted tightly yet still allowed free movement for his strong limbs. He was overjoyed to find he felt as light as if he had wings. Then he took his father’s spear from its stand, the long, massive, weighty spear of ash from the summit of Pelion that Cheiron gave his beloved father for the killing of men, and that Achilles alone now of all the Greeks could wield.

Meanwhile Automedon and Alcimus busied themselves harnessing the horses, tightening the strong breast-straps on their chests, settling the bits in their mouths, and looping the reins back to the wooden chariot. Then Automedon, grasping the gleaming well-balanced whip in his hand, leapt aboard the chariot, while Achilles stepped up behind him, fully armed and shining like Hyperion, the bright sun. Then he gave a fierce cry of reproof to his father’s team: ‘Xanthus and Balius, Podarge’s famous foals, this time think of a way to bring your master back alive when the fight is done, not leave him dead on the field, as you did brave Patroclus.’

Then Xanthus of the glancing feet, whom white-armed Hera granted power of speech, replied from beneath the yoke, bowing his head so his mane streamed down to the ground: ‘This once, mighty Achilles, we will save you, yes, even though the hour of your doom draws nigh, nor indeed will we be the cause of your death even then, rather a mightier god and relentless Fate. It was not through any carelessness or idleness of ours that the Trojans were able to strip Patroclus of your armour, but Apollo best of gods, son of Leto of the lovely tresses, slew him before the army and granted Hector glory. Though we run swift as we can, swift as Zephyrus, the western wind, who flies fastest of all the winds, they say, yet you are fated still to be conquered in battle by a mortal man and a god.’

At that point the Furies checked his utterance, while swift-footed Achilles answered excitedly: ‘What need for you, Xanthus, to prophesy my fate? I know well enough I am doomed to die here, far from my dear parents, yet I will not end till I have given the Trojans their bellyful of war.’

With that he raised his battle-cry, driving his immortal horses to the front.