Homer: The Iliad

Book X

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk X:1-71 Agamemnon and Menelaus meet

- Bk X:72-130 Agamemnon rouses Nestor

- Bk X:131-193 Nestor rouses Odysseus and Diomedes

- Bk X:194-253 Diomedes chooses Odysseus to make a foray

- Bk X:254-298 Diomedes and Odysseus set out

- Bk X:299-348 Hector sends Dolon out to spy

- Bk X:349- 411 Odysseus questions Dolon

- Bk X:412-464 Diomedes kills Dolon

- Bk X:465-514 Diomedes and Odysseus capture the horses of Rhesus

- Bk X:515-579 Diomedes and Odysseus return in triumph

BkX:1-71 Agamemnon and Menelaus meet

Now, while all the rest of the Greek leaders were resting beside their ships, overcome by gentle sleep, Agamemnon, son of Atreus, king of men, was restless, his mind lost in thought. Just as when Zeus, fair Hera’s lord, thunders when he brews a storm of heavy rain or hail, or a blizzard to veil the fields with snow, or opens the jaws of rabid war, so Agamemnon groaned from the depths of his being, and his heart quaked within him. When he looked towards the Trojan plain, he was dazzled by the host of fires burning before Ilium, by the din of flutes and pipes, and human voices. Then gazing towards the ships and his own army, he plucked his hair out by the roots so that Zeus above might see, grieved at heart. Finally it seemed best to seek out Nestor, Neleus’ son, in hopes of devising with him some unique way of warding off a Greek defeat. So he rose and donned his tunic, bound a fine pair of sandals on his gleaming feet, slung a tawny lion skin over his shoulders, a large and glossy pelt that reached his feet, and clasped his spear.

Meanwhile Menelaus was gripped by like forebodings, fearful for the Argives who, filled with visions of war, had sailed with him to Troy over the wide seas: and sleep would not come to his weary eyelids. Throwing a spotted leopard skin over his broad shoulders, and setting his bronze helmet on his head, he also grasped a spear in his strong hand. Then he went to rouse his brother, great king of the Argives, whom the people honoured as a god. He found him by his ships’ stern, slinging his great shield over his shoulder, and the king was overjoyed to see him. Menelaus of the loud war-cry spoke first: ‘Why are you arming, brother? And have you thought of sending someone to spy on the Trojans? Though I doubt you’ll find a man eager for the task, willing to go alone and spy on the enemy in the depth of night: it would need a bold spirit.’

‘Menelaus, nurtured by Zeus’ Agamemnon answered, ‘we need some clever plan to save us Greeks and protect the ships, now Zeus has turned against us. It seems in his heart he prefers Hector’s offerings to ours. I have never known, or heard in the tales, of one man doing as much harm to the Greeks in a single day, as Hector, so dear to Zeus, has, and yet not be the beloved son of some god or goddess. He has done things we shall feel to our sorrow for many a long day, such damage has he inflicted. Go, hurry along the line of ships, and summon Ajax and Idomeneus, while I rouse noble Nestor, hoping he will go with me and visit the outposts, and exhort the watch. They will respond to him, since his own son leads the guard, he and Meriones squire to Idomeneus. They hold that command.’

‘What are your orders, then?’ asked Menelaus of the loud war-cry, ‘should I wait with them there till you come, or hasten back when I’ve told them?’

‘Stay there,’ the king replied, ‘lest we miss each other on the many paths through the camp. But as you go, rouse the army, and call the men by their name and lineage, humbly honouring each. We must toil, in accord with the weight of sorrow Zeus loaded us with at birth.’

BkX:72-130 Agamemnon rouses Nestor

Having charged his brother with this, he sent him on his way, himself setting out in search of Nestor, shepherd of the people, whom he found lying on a soft bed beside the hut and his black ship. His ornate armour was near him, shield, twin spears, and helmet, and the gleaming belt the old man wore when he went into bloody battle, leading his troops in defiance of his great age. Now he raised himself on his elbow, lifted his head, and challenged Atreides: ‘Who are you, wandering alone by the ships in the dead of night, when other men sleep sound? Do you seek a friend, or a stray mule? Stand and speak, what business have you here!’

King Agamemnon answered: ‘Nestor, son of Neleus, glory of the Greeks, surely you know me, Atreides, that Agamemnon whom Zeus has singled out for endless toil, while there is breath in my body or strength in my limbs. I wander abroad because sweet sleep evades my eyelids, troubled by this war and our plight. I fear for our people, and my mind is in turmoil, my heart beats in my breast and my limbs tremble. If you too are wakeful, and want employment, let us look to the sentries, lest they are sleeping, overcome by fatigue and their watch, oblivious to their duty. The enemy are camped so close, and, who knows, they may be willing to mount an attack by night.’

The charioteer, Gerenian Nestor, replied: ‘Agamemnon, king of men, noble son of Atreus, Zeus the Counsellor will prevent Hector realising all those hopes I imagine he now may nurture: rather he will know troubles greater than ours, if ever Achilles forsakes his bitter anger. I will gladly come with you, but let us rouse others too, the spearman Diomedes, swift Ajax the lesser, and brave Meges, Phyleus’ son. It would make sense to send a summons too to Telamonian Ajax, and Idomeneus the king, since their ships are farthest off of all. Yet I bear a reproach for Menelaus, loved and respected though he is, and I must speak though I anger you, if he sleeps while you toil alone. He should be working on the leaders, begging their help, in this hour of desperate need.’

‘Aged sire,’ replied Agamemnon, king of men: ‘at other times I might even reproach him myself, for he often holds back, disinclined to toil, not through laziness or lack of care, but because he looks to me for his orders. Yet this time he was first to wake and come for me, and I sent him on to rouse those two you spoke of last. Let us go seek them among the sentries at the gates, where I told them to gather.’

‘In that case,’ Gerenian Nestor answered, ‘no one will blame, no one will disobey him, when he takes command and urges the men on.’

BkX:131-193 Nestor rouses Odysseus and Diomedes

So saying, he donned his tunic, bound fine sandals on his shining feet, and wrapped a broad purple double-cloak of thick wool around him. Then grasping a sturdy spear with a sharp bronze blade he set off along the line of Achaean ships. He roused Odysseus first, peer of Zeus in counsel, his piercing call waking the sleeper, who left his hut saying: ‘Why are you wandering about like this in the dead of night? What great need demands it?’

Nestor answered: ‘Nimble-witted Odysseus, refrain from indignation for we Greeks are greatly troubled. Follow us and help rouse the others who also must decide whether to fight or flee.’

At this, wily Odysseus entered his hut, slung his ornate shield on his back then followed. Next they found Diomedes, Tydeus’ son, sleeping outside his hut his weapons nearby, his men around him heads resting on their shields, their spears driven into the ground by the butts, and the bronze tips shining out afar like Father Zeus’ lightning. The hero slept on an ox-hide, a bright rug under his head. Nestor woke him with a nudge of the heel in his side, and rebuked him as he woke. ‘Son of Tydeus, awake: do you need a whole night’s rest? The Trojans, you’ll see, are camped by the ships on rising ground and barely a stone’s throw distant!’

Diomedes leapt up swiftly and answered with winged words: ‘You are a tough old man, my lord and never rest. Are there no younger men to do the rounds and summon the leaders? You are insatiable.’

‘Indeed, my friend, it’s true,’ Gerenian Nestor replied: ‘I do have peerless sons and men a-plenty, any one of whom might summon up the others. But we are in dire need: our fate is balanced on a razor’s edge, the survival or utter ruin of the army. Since you are younger, show your pity for me, go rouse swift Ajax the lesser, and Meges, son of Phyleus.’

At this, Diomedes flung about his shoulders the great tawny lion-skin that reached to his feet, grasped his spear, and set out. He roused the warriors named and brought them back with him.

When they reached the knot of sentries they found them wide awake, weapons in their hands. As hounds set to keep uneasy watch over a sheepfold cannot sleep if they hear some savage and aggressive creature roaming the wooded hills, rousing the cry of men and dogs, so the sentries had no sleep as they watched through the perilous night, facing the plain to catch the sound of Trojan attack.

Old Nestor rejoiced at the sight, and spoke words of encouragement: ‘Keep watching as you are, dear lads, and no one fall asleep, lest we give joy to our enemies.’

BkX:194-253 Diomedes chooses Odysseus to make a foray

With this, he hurried off along the ditch, followed by the Argive leaders summoned to the council. Meriones and Nestor’s noble son went too, since they had also been chosen to attend. Leaving the ditch they sat down in an open space, clear of the dead, the place where mighty Hector had turned back at nightfall. There they took counsel and Gerenian Nestor was first to speak: ‘My friends, is there one of us who trusts enough in his own daring to enter the Trojan camp in hopes of cutting out some straggler, or gaining some inkling of their plans? Do they mean to stay here far from the city, or retreat again after their victory? If he learnt the answer to that and returned unharmed, he would be celebrated by us all, and well rewarded. Let every leader among the fleet grant him a black ewe with a suckling lamb, a gift beyond compare, and welcome him to all our feasts and banquets.’

All were silent at his words, except Diomedes of the loud war-cry: ‘Nestor, my pride and courage prompt me to try this Trojan camp, but I’d feel greater security and ease if we were two. With two men, one may see an opportunity the other might miss. A man on his own sees less, and possesses less resource.’

Many of them clamoured to go with him: the two warrior Aiantes, Meriones and Nestor’s son, and the great spearman Menelaus. Doughty Odysseus too, always full of boldness, was more than eager to infiltrate the Trojan camp. Then Agamemnon, king of men, addressed Diomedes: ‘Son of Tydeus, dear to me, yourself select the comrade you desire, the best of those who offer, since many men are eager. Don’t let undue respect for birth, or royalty, cause you to choose the worse, and leave the better man behind.’

He spoke these words fearing for the safety of red-haired Menelaus his brother. But Diomedes of the loud war-cry replied: ‘If I am free to choose, I cannot ignore godlike Odysseus whose brave spirit is eager for every adventure. Pallas Athene loves him. Together we might go through blazing fire and return: his is the shrewdest mind of all.’

Noble long-enduring Odysseus then spoke: ‘Be sparing of your praise, Diomedes, and your blame too, since these Greeks all know me. Let us go, since night advances and dawn draws near; the stars have journeyed two thirds of their course, one third alone is left us.’

BkX:254-298 Diomedes and Odysseus set out

Then the formidable pair armed themselves. The staunch Thrasymedes passed Diomedes a shield and a double-edged sword, in place of the one he had left by the ship. On his head he placed an ox-hide skullcap, without peak or crest, the type young bloods wear to defend them. Meanwhile Meriones gave Odysseus quiver, bow and sword, then set a leather helmet on his head, stiffened inside with straps over a cap of felt, cunningly and densely set outside with gleaming white boar-tusks. Autolycus stole the thing from Eleon, when he robbed Amyntor’s house, and gave it to Amphidamas of Cythera to take to Scandeia. He in turn gifted it to Molus, his guest, who passed it then to his son Meriones to wear, and now it was Odysseus’ head it guarded.

Formidably armed they left the group of leaders and set off. And Athene sent an omen, a heron close by on the right, unseen by them in the gloomy night, but apparent by its cry. Odysseus rejoiced, and prayed to Pallas Athene: ‘Hear me, daughter of aegis-bearing Zeus, you who are with me in all my adventures, protecting me wherever I go. Show me your love, Athene, now, more than ever, and grant we return to the ships having won renown, with some brave act that will grieve the Trojans greatly.’

And Diomedes of the loud war-cry followed him in prayer: ‘Hear me also, Atrytone, daughter of Zeus. Be with me as you were with my father Tydeus in Thebes, when he went there as ambassador for the bronze-greaved Achaeans, camped there by the Asopus. A friendly offer was what he made them, but on his way back he was forced to take deadly reprisal for their ambush, and you fair goddess, readily stood by him. Stand by me now, and watch over me, and in return I will offer a broad-browed yearling heifer, unused to the yoke. I will tip her horns with gold and sacrifice her to you.’

These were the prayers, and Pallas Athene heard. Their praying done, they set out, like a pair of lions through the dark, through the remnants of slaughter, the corpses and the weapons darkly stained with blood.

BkX:299-348 Hector sends Dolon out to spy

The brave Trojans too had little time for sleep, since Hector summoned the noblest leaders and counsellors. When they were gathered he proposed a shrewd tactic: ‘Who will volunteer to do a deed, and win a rich reward? I guarantee a chariot and a pair of stallions with high arched necks, the best the Greeks have tethered by the ships, to whoever makes a foray towards their camp, and finds if their swift fleet is guarded as before, or whether defeat has them preparing flight, and a fatal weariness leads them to slacken watch.’

Silence fell at his words but, among the Trojans, was Dolon, son of the sacred herald Eumedes, and a man rich in gold and bronze, ugly to look at but a swift runner, brother of five sisters. He now stepped forward to address Hector and the gathered Trojans: ‘My heart prompts me, my spirit of adventure too, to reconnoitre the ships and report. But first raise the staff high, and swear to me you will grant me the chariot inlaid with bronze, and the horses, of that peerless son of Peleus. For, I will not fail or dash your hopes. I will steal through their camp to Agamemnon’s ship where the leaders must be, debating whether to fight or flee.’

At this, Hector lifted the staff in his hands and swore the oath: ‘Let Zeus the Thunderer himself, Hera’s lord, be witness. No other man shall mount behind those horses but you, yours to enjoy forever.’

His oath proved without force, but it satisfied Dolon, who quickly slung his curved bow on his shoulder, threw a grey wolf’s pelt over it, placed a ferret-skin cap on his head, and grasping a sharp javelin set off towards the ships. Once he had left the camp, crowded with men and horses, he went eagerly on his way, though fated not to return again with news for Hector.

Noble Odysseus soon spotted him, and said: ‘Diomedes, someone comes from the enemy camp, perhaps as a spy or to strip the corpses. Let him go past us a little way then we can rush him and take him captive. If he is quick enough to outrun us, threaten him with your spear and drive him towards the ships and away from his camp, lest he makes a run for the city.’

BkX:349- 411 Odysseus questions Dolon

With this, they lay down, off the path, among the corpses, while Dolon unknowingly ran past them. When he was as far as the width of land a mule-team plough in a day, mules being better at ploughing deep fallow than oxen, the pair gave chase. Hearing the sound behind him he thought they were friends from the Trojan ranks coming to call him back, and that Hector had changed his mind. But when they were no more than a spear-cast distant, he knew they were enemies and took to his heels, while they tore after him. Like two sharp-fanged hunting dogs pursuing a doe or a screaming hare through the woods, so Diomedes and Odysseus, sacker of cities, relentlessly chased him down, cutting him off from his camp. As he ran towards the ships, about to reach the outposts, Athene spurred Diomedes on, so that no bronze-clad Achaean could boast of striking Dolon before him. Running upon him, spear raised, the mighty warrior shouted: ‘Stop or I strike you down: you’ll be doomed to die at my hand.’

So saying, he hurled the spear, missing the man on purpose, the tip of the gleaming spear passing over the right shoulder, and fixing itself in the ground. Dolon halted, gripped by terror, pale with fear and teeth chattering. As his pursuers, panting for breath, reached him and grasped his arms, he stammered: ‘Take me alive, I will pay the ransom. I have gold, bronze and wrought iron, and my father will give a small fortune to hear I was taken alive by you Greeks.’

‘Take heart,’ replied wily Odysseus, ‘keep death far from your mind, and answer truly. Where are you off to at dead of night, while other men sleep? Are you out to strip the bodies of the dead, did Hector send you to spy on the hollow ships, or perhaps it was your own idea?’

His limbs trembling, Dolon answered: ‘Hector seduced my mind with vain hopes, promising me noble Achilles’ chariot inlaid with fine bronze, and his team of horses. He told me to use the dark of night to infiltrate your camp, and find if your swift fleet was guarded as before, or whether defeat had you preparing flight, and a fatal weariness forced you to slacken watch.’

Cunning Odysseus smiled as he replied: ‘Your heart was set on a fine prize indeed, Achilles’ horses: hard for a mortal man to handle and control, save the warrior grandson of Aeacus, with a goddess for a mother. Now tell me this, and tell true, where was Hector, leader of men, when you left him? Where are his horses and his battle gear? What are the Trojan dispositions, what watch do they keep, and what do they plan themselves? Do they mean to stay here far from the city, or retreat again after their victory over us?’

BkX:412-464 Diomedes kills Dolon

Dolon, son of Eumedes, replied: ‘To tell true, Hector and the councillors meet by the tomb of noble Ilus, away from the noise. As for the guards, there is no special watch. Round the Trojan fires those on duty stay wakeful and keep each other alert. As for the foreign allies, since they are far from wives and children, they sleep and leave the Trojans to keep a lookout.’

Wily Odysseus still questioned: ‘How disposed? Do the allies sleep among the horse-taming Trojans or apart? Be clear, I need to know.’

‘I will tell you that truly, too,’ Dolon answered, ‘The Carians, Paeonians of the curved bow, Leleges, Caucones and noble Pelasgi, are camped towards the coast. While the Lycians, lordly Mysians, Phrygian horsemen and Maeonian charioteers are camped towards Thymbre. Why are you asking all this? If you are keen to raid the camp, the Thracians there are latecomers, and furthest out. Rhesus, son of Eioneus, is their royal leader. He has the tallest, finest horses I ever saw, whiter than snow and fast as the wind. His chariot is finely worked in gold and silver, and he brought his gold armour with him, huge and wondrous to look on. It is armour fit for a deathless god, not a mere mortal. So, take me to your swift ship, or bind me as tight as you wish and leave me here, then you can quickly prove whether I tell true or no.’

But mighty Diomedes turned on him in anger: ‘You can forget all thought of escape, now you’ve told us what we needed to know. Release you now, and you live to return to our ships and fight, or spy on us once more. Meet death now, at my hands, and never again be a danger to the Argives.’

As he spoke, Dolon raised his large hand, though only to touch Diomedes’ chin to beg for mercy. But Diomedes sprang at him with his sword striking him square on the neck. The blade sheared through the sinews, and Dolon’s head fell in the dust even as he tried to speak.

Then they took his wolf’s hide and ferret-skin cap, curving bow and long spear. And noble Odysseus lifted them high in his hands for Athene, the goddess of spoils, to see, and prayed: ‘Take pleasure in these, goddess, you whom we call on first of all the immortals, and help us again as we raid the Thracian camp and take their horses.’

BkX:465-514 Diomedes and Odysseus capture the horses of Rhesus

With this, he pushed the spoils into a tamarisk bush, and marked the place with a heap of reeds and thick tamarisk branches, so as not to miss it when returning swiftly through the dark night. Then they both picked their way among bloodstained weapons, and soon reached the Thracian camp. The enemy were fast asleep wearied by their efforts with their fine battle gear on the ground beside them, in three neat rows. Every man slept by his horses, with Rhesus at their centre, his own swift horses tethered to the chariot rail by their reins. Odysseus saw him first and showed him to Diomedes: ‘There is our man, and there are those horses Dolon spoke of before he died. Now exert all your strength, let not our weapons be idle, and loose the horses too; or rather you kill the men, and I’ll handle the horses.’

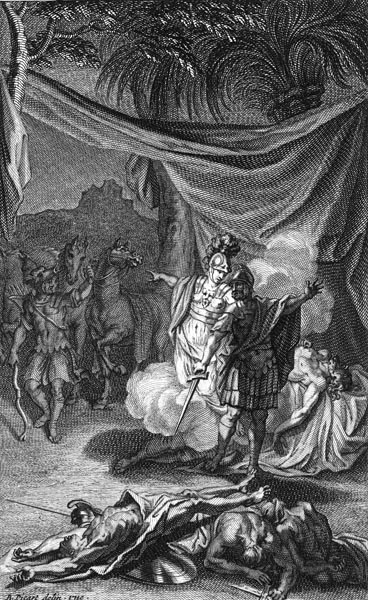

‘Diomedes kills Rhesus’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

At this, Diomedes, into whom bright-eyed Athene breathed new fury, set about killing those right and left, while hideous groans rose from the dying, and the earth ran red with their blood. Like a lion that finds an undefended flock of sheep or goats, and springs on them with slaughter in its heart, so the son of Tydeus despatched twelve Thracian warriors one by one. And as Diomedes killed each man, wily Odysseus seized the body by the feet from behind, and dragged it aside leaving the way clear for the long-maned horses, who might take fright if they trod on the fresh corpses of their masters. When Diomedes reached the king, who was breathing heavily in his dreams, for sent by Athene, a malign phantom of that grandson of Oeneus already hovered over his head: then the thirteenth victim was robbed of honey-sweet life. And stalwart Odysseus loosed the horses, tied their reins together, and drove them clear of the scene, with a touch or two of his bow, neglecting to take the gleaming whip from the ornate chariot. Then he whistled, as a sign to Diomedes.

‘Diomedes kills Rhesus’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

But Diomedes lingered, debating what he might risk, whether to lift and carry, or drag away, the chariot and all its inlaid battle gear, or whether to go on killing Thracians. He was still debating, when Athene came to warn the noble warrior: ‘Son of brave Tydeus, better head for the hollow ships now, or perhaps some other god will rouse the Trojans, and you will be forced to flee.’

Knowing the voice of the goddess, he heeded her words and ran swiftly to a horse. Odysseus flicked his bow once more, and off they sped towards the Achaean fleet.

BkX:515-579 Diomedes and Odysseus return in triumph

But Apollo of the Silver Bow was not blind to Athene’s aid to Diomedes. Enraged by her actions, he descended on the great Trojan army, and roused a Thracian leader, Hippocoön, Rhesus’ noble kinsman. The man leapt up from sleep, and seeing the horsemen drenched in blood, gasping out their lives, and the empty spaces where their horses had been tethered, he groaned aloud and called out his dear kinsman’s name. This brought the Trojans running, with vast noise and confusion, to gaze at what the two Greeks had done before they had headed for the ships.

They, meanwhile, had reined in the swift horses at the spot where Diomedes had killed Hector’s spy, and there Diomedes leapt down, handed up the bloodstained spoils to Odysseus, and then re-mounted. They urged the horses on with a will, eager to reach the hollow ships again.

Nestor was first to hear them coming: ‘My friends, you leaders and counsellors of the Argives, am I wrong, or is it true, what my heart prompts me to utter? I hear the sound of galloping horses. I hope it’s Odysseus and Diomedes, bringing us fine Trojan steeds, yet I fear lest it’s the sound of Trojan cavalry spelling disaster to those two, the best of us Greeks.’

The words were barely out of his mouth when they both arrived. They leapt to the ground, and were welcomed joyously with clasped hands and noble words. Gerenian Nestor was first with the questions: ‘Inestimable Odysseus, glory of Greece: tell me how on earth you found those horses? Did you raid the Trojan camp, or more likely some god met you on the way, and gave you them as a gift. They gleam like rays of light. I meet the Trojans in battle all the time: old I may be, but I never miss a fight, yet I have never seen nor imagined they had such horses. Yes, you met with a deathless one, and they are a gift: for Zeus the Cloud-gatherer loves you, and his daughter who bears the aegis does so too, bright-eyed Athene.’

‘Nestor son of Neleus, flower of Greek chivalry,’ Odysseus of the many wiles replied ‘the immortals are mightier than us by far, and could easily grant us better horses than these, though they, my lord, are fresh from Thrace. Brave Diomedes killed their master and twelve of the best men in his camp as well. And we caught and killed a man near the ships, and that makes fourteen, whom Hector and the rest of the proud Trojans sent to spy on our camp.’

With that he drove the horses across the trench, in triumph, and the rest of the joyous Greeks followed. When they reached Diomedes’ well-built hut, they tethered the horses with fine leather thongs to the manger where Diomedes’ own team were feeding on honey-sweet barley. And Odysseus placed Dolon’s bloodstained gear in the stern of his ship, till he was ready to offer them formally to Athene. Then the two warriors went down to the sea, and washed the sweat from their bodies, head to foot. When the waves had cleared the sweat, and they were refreshed, they went to gleaming baths to bathe further. And after bathing and rubbing themselves with oil, they sat down to eat and draw honeyed wine from the full mixing bowl, to pour libations to Athene.