Hesiod's Works and Days

Translated by Christopher Kelk

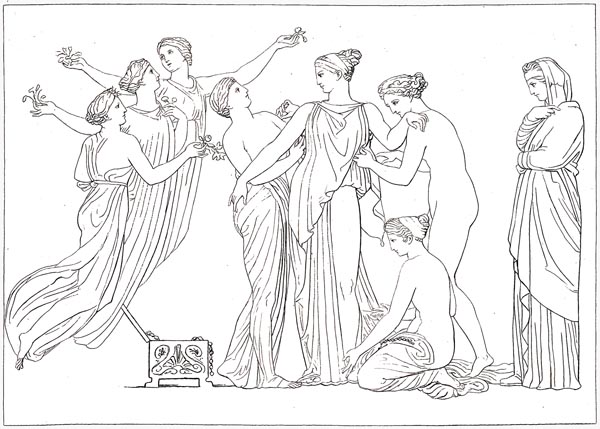

Compositions from the Works, Days and Theogony of Hesiod, 1817

William Blake (1757–1827) - The Minneapolis Museum of Art

© Copyright 2020 Christopher Kelk, All Rights Reserved.

Please direct enquiries for commercial re-use to chriskelk@sympatico.ca.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Pierian Muses, with your songs of praise,

Come hither and of Zeus, your father, tell,

Through whom all mortal men throughout their days

Acclaimed or not, talked of or nameless dwell,

So great is he. He strengthens easily

The weak, makes weak the strong and the well-known

Obscure, makes great the low; the crooked he

Makes straight, high-thundering Zeus upon his throne.

See me and hear me, make straight our decrees,

For, Perses, I would tell the truth to you. 10

Not one, but two Strifes live on earth: when these

Are known, one’s praised, one blamed, because these two

Far differ. For the one makes foul war thrive,

The wretch, unloved of all, but the gods on high

Gave the decree that every man alive

Should that oppressive goddess glorify.

The other, black Night’s first-born child, the son

Of Cronus, throned on high, set in the soil,

A greater boon to men; she urges on

Even the slack to work. One craves to toil 20

When others prosper, hankering to seed

And plough and set his house in harmony.

So neighbour vies with neighbour in great need

Of wealth: this Strife well serves humanity.

Potter hates potter, builder builder, and

A beggar bears his fellow-beggar spite,

Likewise all singers. Perses, understand

My verse, don’t let the evil Strife invite

Your heart to shrink from work and make you gaze

And listen to the quarrels in the square - 30

No time for quarrels or to spend one’s days

In public life when in your granary there

Is not stored up a year’s stock of the grain

Demeter grants the earth. Get in that store,

Then you may wrangle, struggling to obtain

Other men’s goods – a chance shall come no more

To do this. Let’s set straight our wrangling

With Zeus’s laws, so excellent and fair.

We split our goods in two, but, capturing

The greater part, you carried it from there 40

And praised those kings, bribe-eaters, who adore

To judge such cases. Fools! They do not know

That half may well transcend the total store

Or how the asphodel and the mallow

Will benefit them much. The means of life

The gods keep from us or else easily

Could one work for one day, then, free from strife,

One’s rudder packed away, live lazily,

Each ox and hard-worked mule sent off. In spleen

That fraudulent Prometheus duped him, Zeus 50

Kept safe this thing, devising labours keen

For men. He hid the fire: for human use

The honourable son of Iapetus

Stole it from counsellor Zeus and in his guile

He hid it in a fennel stalk and thus

Hoodwinked the Thunderer, who aired his bile,

Cloud-Gatherer that he was, and said: “O son

Of Iapetus, the craftiest god of all,

You stole the fire, content with what you’d done,

And duped me. So great anguish shall befall 60

Both you and future mortal men. A thing

Of ill in lieu of fire I’ll afford

Them all to take delight in, cherishing

The evil”. Thus he spoke and then the lord

Of men and gods laughed. Famed Hephaistus he

Enjoined to mingle water with some clay

And put a human voice and energy

Within it and a goddess’ features lay

On it and, like a maiden, sweet and pure,

The body, though Athene was to show 70

Her how to weave; upon her head allure

The golden Aphrodite would let flow,

With painful passions and bone-shattering stress.

Then Argus-slayer Hermes had to add

A wily nature and shamefacedness.

Those were his orders and what Lord Zeus bade

They did. The famed lame god immediately

Formed out of clay, at Cronus’ son’s behest,

The likeness of a maid of modesty.

By grey-eyed Queen Athene was she dressed 80

And cinctured, while the Graces and Seduction

Placed necklaces about her; then the Hours,

With lovely tresses, heightened this production

By garlanding this maid with springtime flowers.

Athene trimmed her up, while in her breast

Hermes put lies and wiles and qualities

Of trickery at thundering Zeus’ behest:

Since all Olympian divinities

Bestowed this gift, Pandora was her name,

A bane to all mankind. When they had hatched 90

This perfect trap, Hermes, that man of fame,

The gods’ swift messenger, was then dispatched

To Epimetheus. Epimetheus, though,

Ignored Prometheus’ words not to receive

A gift from Zeus but, since it would cause woe

To me, so send it back; he would perceive

This truth when he already held the thing.

Before this time men lived quite separately,

Grief-free, disease-free, free of suffering,

Which brought the Death-Gods. Now in misery 100

Men age. Pandora took out of the jar

Grievous calamity, bringing to men

Dreadful distress by scattering it afar.

Within its firm sides, Hope alone was then

Still safe within its lip, not leaping out

(The lid already stopped her, by the will

Of aegis-bearing Zeus). But all about

There roam among mankind all kinds of ill,

Filling both land and sea, while every day

Plagues haunt them, which, unwanted, come at night 110

As well, in silence, for Zeus took away

Their voice – it is not possible to fight

The will of Zeus. I’ll sketch now skilfully,

If you should welcome it, another story:

Take it to heart. The selfsame ancestry

Embraced both men and gods, who, in their glory

High on Olympus first devised a race

Of gold, existing under Cronus’ reign

When he ruled Heaven. There was not a trace

Of woe among them since they felt no pain; 120

There was no dread old age but, always rude

Of health, away from grief, they took delight

In plenty, while in death they seemed subdued

By sleep. Life-giving earth, of its own right,

Would bring forth plenteous fruit. In harmony

They lived, with countless flocks of sheep, at ease

With all the gods. But when this progeny

Was buried underneath the earth – yet these

Live on, land-spirits, holy, pure and blessed,

Who guard mankind from evil, watching out 130

For all the laws and heinous deeds, while dressed

In misty vapour, roaming all about

The land, bestowing wealth, this kingly right

Being theirs – a second race the Olympians made,

A silver one, far worse, unlike, in sight

And mind, the golden, for a young child stayed,

A large bairn, in his mother’s custody,

Just playing inside for a hundred years.

But when they all reached their maturity,

They lived a vapid life, replete with tears, 140

Through foolishness, unable to forbear

To brawl, spurning the gods, refusing, too,

To sacrifice (a law kept everywhere).

Then Zeus, since they would not give gods their due,

In rage hid them, as did the earth – all men

Have called the race Gods Subterranean,

Second yet honoured still. A third race then

Zeus fashioned out of bronze, quite different than

The second, with ash spears, both dread and stout;

They liked fell warfare and audacity; 150

They ate no corn, encased about

With iron, full invincibility

In hands, limbs, shoulders, and the arms they plied

Were bronze, their houses, too, their tools; they knew

Of no black iron. Later, when they died

It was self-slaughter – they descended to

Chill Hades’ mouldy house, without a name.

Yes, black death took them off, although they’d been

Impetuous, and they the sun’s bright flame

Would see no more, nor would this race be seen 160

Themselves, screened by the earth. Cronus’ son then

Fashioned upon the lavish land one more,

The fourth, more just and brave – of righteous men,

Called demigods. It was the race before

Our own upon the boundless earth. Foul war

And dreadful battles vanquished some of these,

While some in Cadmus’ Thebes, while looking for

The flocks of Oedipus, found death. The seas

Took others as they crossed to Troy fight

For fair-tressed Helen. They were screened as well 170

In death. Lord Zeus arranged it that they might

Live far from others. Thus they came to dwell,

Carefree, among the blessed isles, content

And affluent, by the deep-swirling sea.

Sweet grain, blooming three times a year, was sent

To them by the earth, that gives vitality

To all mankind, and Cronus was their lord,

Far from the other gods, for Zeus, who reigns

Over gods and men, had cut away the cord

That bound him. Though the lowest race, its gains 180

Were fame and glory. A fifth progeny

All-seeing Zeus produced, who populated

The fecund earth. I wish I could not be

Among them, but instead that I’d been fated

To be born later or be in my grave

Already: for it is of iron made.

Each day in misery they ever slave,

And even in the night they do not fade

Away. The gods will give to them great woe

But mix good with the bad. Zeus will destroy 190

Them too when babies in their cribs shall grow

Grey hair. No bond a father with his boy

Shall share, nor guest with host, nor friend with friend –

No love of brothers as there was erstwhile,

Respect for aging parents at an end.

Their wretched children shall with words of bile

Find fault with them in their irreverence

And not repay their bringing up. We’ll find

Cities brought down. There’ll be no deference

That’s given to the honest, just and kind. 200

The evil and the proud will get acclaim,

Might will be right and shame shall cease to be,

The bad will harm the good whom they shall maim

With crooked words, swearing false oaths. We’ll see

Envy among the wretched, foul of face

And voice, adoring villainy, and then

Into Olympus from the endless space

Mankind inhabits, leaving mortal men,

Fair flesh veiled by white robes, shall Probity

And Shame depart, and there’ll be grievous pain 210

For men: against all evil there shall be

No safeguard. Now I’ll tell, for lords who know

What it purports, a fable: once, on high,

Clutched in its talon-grip, a bird of prey

Took off a speckled nightingale whose cry

Was “Pity me”, but, to this bird’s dismay,

He said disdainfully: “You silly thing,

Why do you cry? A stronger one by far

Now has you. Although you may sweetly sing,

You go where I decide. Perhaps you are 220

My dinner or perhaps I’ll let you go.

A fool assails a stronger, for he’ll be

The loser, suffering scorn as well as woe.”

Thus spoke the swift-winged bird. Listen to me,

Perses – heed justice and shun haughtiness;

It aids no common man: nobles can’t stay

It easily because it will oppress

Us all and bring disgrace. The better way

Is Justice, who will outstrip Pride at last.

Fools learn this by experience because 230

The God of Oaths, by running very fast,

Keeps pace with and requites all crooked laws.

When men who swallow bribes and crookedly

Pass sentences and drag Justice away,

There’s great turmoil, and then, in misery

Weeping and covered in a misty spray,

She comes back to the city, carrying

Woe to the wicked men who ousted her.

The city and its folk are burgeoning,

However, when to both the foreigner 240

And citizen are given judgments fair

And honest, children grow in amity,

Far-seeing Zeus sends them no dread warfare,

And decent men suffer no scarcity

Of food, no ruin, as they till their fields

And feast; abundance reigns upon the earth;

Each mountaintop a wealth of acorns yields,

Bees thrive below, and mothers all give birth

To children who resemble perfectly

Their fathers, while the fleeces on the sheep 250

Are heavy. All things flourish, while the sea

Needs not a ship; the vital soil is deep

With fruits. Far-seeing Zeus evens the score

Against proud, evil men. The wickedness

Of one man often sways whole cities, for

The son of Cronus sends from heaven distress,

Both plague and famine, causing death amid

Its folk, its women barren. Homes decline

By Zeus’s plan. Sometimes he will consign

Broad armies to destruction or will bid 260

Them of their walls and take their ships away.

Lords, note this punishment. The gods are nigh

Those mortals who from adulation stray

And grind folk down with fraud. Yes, from on high

Full thirty-thousand gods of Zeus exist

Upon the fecund earth who oversee

All men and wander far, enclosed in mist,

And watch for law-suits and iniquity.

Justice is one, daughter of Zeus, a maid

Who is renowned among the gods who dwell 270

High in Olympus: should someone upbraid

Her cruelly, immediately she’ll tell

Lord Zeus, there at his side, of men who cause

Much woe till people pay a penalty

For unjust lords, who cruelly bend the laws

For evil. You who hold supremacy

And swallow bribes, beware of this and shun

All crooked laws and deal in what is best.

Who hurts another hurts himself. When one

Makes wicked plans, he’ll be the most distressed. 280

All-seeing Zeus sees all there is to see

And, should he wish, takes note nor fails to know

The justice in a city. I’d not be

A just man nor would have my son be so –

It’s no use being good when wickedness

Holds sway. I trust wise Zeus won’t punish me.

Perses, remember this, serve righteousness

And wholly sidestep the iniquity

Of force. The son of Cronus made this act

For men - that fish, wild beasts and birds should eat 290

Each other, being lawless, but the pact

He made with humankind is very meet –

If one should know and publicize what’s right,

Far-seeing Zeus repays him with a store

Of wealth, but if one swears false oaths outright,

Committing fatal wrongs, forevermore

His kin shall live in gloominess, while he

Who keeps his oath shall benefit his kin.

I tell you things of great utility,

Foolish Perses; to take and capture sin 300

En masse is easy: she is very near,

The road is flat. To goodness, though, much sweat

The gods have placed en route. The road is sheer

And long and rough at first, but when you get

Right to the very peak, though hard to bear

It’s found with ease. That man is wholly best

Who uses his own mind and takes good care

About the future. Who takes interest

In others’ notions is a good man too,

But he who shuns these things is valueless. 310

Remember all that I have said to you,

Noble Perses, and work with steadfastness

Till Hunger vexes you and you’re a friend

Of holy, wreathed Demeter, who with corn

Will fill your barn. But Hunger will attend

A lazy man. The gods and men all scorn

A lazy man, who’s like a stingless drone

Who merely eats and wastes the industry

Of the bees. You must be organized and hone

Your working skills so that your granary 320

Is full at harvest-time. Through work men grow

Wealthy in sheep and gold: by earnest work

One’s loved more by the gods above. There’s no

Disgrace in toil; disgrace it is to shirk.

The wealth you gain from work will very soon

Be envied by the idle man: virtue

And fame come to the rich. A greater boon

Is work, whatever else happens to you,

If from your neighbours’ goods your foolish mind

You turn and earn your pay by industry, 330

As I bid you. Shame of a cringing kind

Attends a needy man, ignominy

That causes major damage or will turn

To gain. Poor men feel sham, the rich, though, are

Self-confident. The money that we earn

Should not be seized – god-sent, it’s better far.

If someone steals great riches by duress

Or with a lying tongue, as has ensued

Quite often, when his mind in cloudiness

Is cast by gain, and shame is now pursued 340

By shamelessness, the gods then easily

Destroy him, bringing down his house, and there,

In record time, goes his prosperity.

Likewise, if someone brings great ills to bear

On guest or suppliant or, by wrong beguiled,

Lies with his brother’s wife or sinfully

Brings harm upon a little orphan child,

Or else insults with harsh contumely

His aged father, thus provoking Zeus

And paying dearly for his sins. But you 350

Must keep your foolish heart from such abuse

And do your best to give the gods their due

Of sacrifice; the glorious meat-wrapped thighs

Roast for them, please them with an offering

Of wine and balm at night and when you rise

To gain their favour and that it may bring

The sale of others’ goods, not yours. Invite

A friend to dine and not an enemy,

A neighbour chiefly, for disaster might

Be near and they’re in the vicinity, 360

Unarmed through haste, while kinsmen will delay

In arming. Wicked neighbours cause much pain

But good ones bring a splendid profit. They

Who have good neighbours find that they will gain

Much worth. No cow is lost unless you dwell

Near wicked neighbours. Measure carefully

When borrowing from a neighbour, serve them well

When giving him repayment equally,

Nay more if you are able, for you’ll gain

By this a friend in need, and do not earn 370

Ill-gotten wealth – such profits are a bane.

Love all your friends, turn to all those who turn

To you. Give to a giver but forbear

To give to one who doesn’t give. One gives

To open-handed men but does not care

To please a miser thus, for Giving lives

In virtue, while Theft lives in sin and brings

Grim death. The man who gives abundantly

And willingly rejoices in the things

He gives, delights within his soul. But he 380

Who steals however small a thing will find

A freezing in his heart. Add to your store

And leave ferocious famine far behind;

If to a little you a little more

Should add and do this often, with great speed

It will expand. A man has little care

For what he has at home: there’s greater need

To guard his wealth abroad, while still his share

At home is safer. Taking from your store

Is good, but wanting something causes pain – 390

Think on this. Use thrift with the flagon’s core

But when you open it and then again

As it runs out, then take your fill – no need

For prudence with the lees. Allow no doubt

About a comrade’s wages; no, take heed

Even with your brother – smile and ferret out

A witness. Trust and mistrust both can kill.

Let not a dame, fawning and lascivious,

Dupe you - she wants your barn. Your trust is ill-

Placed in a woman – she’s perfidious. 400

An only child preserves his family

That wealth may grow. But if one leaves two heirs,

One must live longer. Zeus, though, easily

To larger houses gives great wealth. The cares

And increase for more kindred greater grow.

If you want wealth, do this, add industry

To industry, and harvest what you sow

When Pleiades’ ascendancy you see,

And plough when they have set. They lurk concealed

For forty days and nights but then appear 410

In time when first your sickles for the field

You sharpen. This is true for dwellers near

The level plains and sea, and those who dwell

In woody glens far from the raging deep,

Those fertile lands; sow naked, plough, as well,

Unclothed, and harvest stripped if you would reap

Demeter’s work in season. Everything

Will then be done in time: in penury

You’ll not beg help at others’ homes and bring

Your own downfall. Thus now you come to me: 420

I’ll give you nothing. Practise industry,

Foolish Perses, which the gods have given men,

Lest, with their wives and children, dolefully

They seek food from their neighbours, who will then

Ignore them. Twice or thrice you may succeed,

But if you still harass them, you’ll achieve

Nothing and waste your words about your need.

I urge you, figure how you may relieve

Your need and cease your hunger. The first thing

That you must do is get a house, then find 430

A slave to help you with your furrowing,

Female, unwed, an ox to plough behind,

Then in the house prepare the things you’ll need;

Don’t borrow lest you be refused and lack

All means and, as the hours duly speed

Along, your labour’s lost. Do not push back

Your toil for just one day: don’t drag your feet

And fight with ruin evermore. No, when

You feel no more the fierce sun’s sweaty heat

And mighty Zeus sends autumn rain, why, then 440

We move more quickly – that’s the time when we

See Sirius travelling less above us all,

Poor wretches, using night more, and that tree

You cut has shed its foliage in the fall,

No longer sprouting, and is less replete

With worm-holes. Now’s the time to fell your trees.

Cut with a drilling-mortar of three feet

And pestle of three cubits: you must seize

A seven-foot axle – that’s a perfect fit

(You’ll make a hammerhead with one of eight). 450

To have a ten-palm wagon, make for it

Four three-foot wagon-wheels. Wood that’s not straight

Is useful – gather lots for use within:

At home or in the mountains search for it.

Holm-oak is strongest for the plough: the pin

Is fixed on it, on which the pole will sit,

By craftsmen of Athene. But make two

Within your house, of one piece and compressed.

That’s better - if one breaks the other you

May use. Sound elm or laurel are the best 460

For poles. The stock should be of oak, the beam

Of holm-oak. Two bull oxen you should buy,

Both nine years old - a prime age, you may deem,

For strength. They toil the hardest nor will vie

In conflict in the furrows nor will break

The plough or leave the work undone. And now

A forty-year-old stalwart you should take

Who will, before he ventures out to plough,

Consume a quartered, eight-slice loaf, one who,

Skilled in his craft, will keep the furrow straight 470

Nor look around for comrades but stay true

To his pursuit. Born at a later date,

A man may never plough thus and may cause

A second sowing. Younger men, distract,

Will wink at comrades. Let this give you pause -

The crane’s high, yearly call means “time to act”

Start ploughing for it’s winter-time. It’s gall

To one who has no oxen: it will pay

To have horned oxen fattened in their stall.

It will be simple then for you to say 480

“Bring me my oxen and my wagon too”,

And it is also easy to reject

A friend and say “They have their work to do,

My oxen.” Merely mind-rich men expect

Their wagon’s made already, foolish men.

They don’t know that a hundred boards they’ll need.

Get all you need together and then, when

The ploughing term commences, with all speed,

You and your slaves, set out and plough straight through

The season, wet or dry; quick, at cockcrow, 490

That you may fill those furrows, plough; and you

Should plough in spring; the summer, should you go

On ploughing, won’t dismay you. Plough your field

When soil is light – such is a surety

For us and for our children forms a shield.

Pray, then, to Zeus, the god of husbandry,

And pure Demeter that she fill her grain.

First grab the handles of the plough and flick

The oxen as upon the straps they strain.

Then let a bondsman follow with a stick, 500

Close at your back, to hide the seed and cheat

The birds. For man good management’s supreme,

Bad management is worst. If you repeat

These steps, your fields of corn shall surely teem

With stalks which bow down low if in the end

Zeus brings a happy outcome and you’ve cleared

Your jars of cobwebs: then if you make fast

Your stores of food at home you will be cheered,

I think. You’ll be at ease until pale spring,

Nor will you gape at others – rather they’ll 510

Have need of you. Keep at your furrowing

Until the winter sun and surely fail

And reap sat down and seize within your hand

Your meagre crop and bind with dusty speed,

With many a frown, and take it from your land

Inside a basket, and few folk will waste

Their praise upon you. Aegis-bearing Zeus

Is changeable – his thoughts are hard to see.

If you plough late, this just may be of use:

When first the cuckoo calls on the oak-tree 520

And through the vast earth causes happiness,

Zeus rains non-stop for three days that the height

Of flood’s an ox’s hoof, no more, no less:

That way the man who ploughs but late just might

Equal the early plougher. All this you

Must do, and don’t permit pale spring to take

You by surprise, the rainy season, too.

Round public haunts and smithies you should make

A detour during winter when the cold

Keeps men from work, for then a busy man 530

May serve his house. Let hardship not take hold,

Nor helplessness, through cruel winter’s span,

Nor rub your swollen foot with scrawny hand.

An idle man will often, while in vain

He hopes, lacking a living from his land,

Consider crime. A needy man will gain

Nothing from hope while sitting in the street

And gossiping, no livelihood in sight.

Say to your slaves in the midsummer heat:

“There won’t always be summer, shining bright – 540

Build barns.” Lenaion’s evil days, which gall

The oxen, guard yourself against. Beware

Of hoar-frosts, too, which bring distress to all

When the North Wind blows, which blasts upon the air

In horse-rich Thrace and rouses the broad sea,

Making the earth and woods resound with wails.

He falls on many a lofty-leafed oak-tree

And on thick pines along the mountain-vales

And fecund earth, the vast woods bellowing.

The wild beasts, tails between their legs, all shake. 550

Although their shaggy hair is covering

Their hides, yet still the cold will always make

Their way straight through the hairiest beast. Straight through

An ox’s hide the North Wind blows and drills

Through long-haired goats. His strength, though, cannot do

Great harm to sheep who keep away all chills

With ample fleece. He makes old men stoop low

But soft-skinned maids he never will go through –

They stay indoors, who as yet do not know

Gold Aphrodite’s work, a comfort to 560

Their darling mothers, and their tender skin

They wash and smear with oil in winter’s space

And slumber in a bedroom far within

The house, when in his cold and dreadful place

The Boneless gnaws his foot (the sun won’t show

Him pastures but rotate around the land

Of black men and for all the Greeks is slow

To brighten). That’s the time the hornèd and

The unhorned beasts of the wood flee to the brush,

Teeth all a-chatter, with one thought in mind – 570

To find some thick-packed shelter, p’raps a bush

Or hollow rock. Like one with head inclined

Towards the ground, spine shattered, with a stick

To hold him up, they wander as they try

To circumvent the snow. As I ordain,

Shelter your body, too, when snow is nigh –

A fleecy coat and, reaching to the floor,

A tunic. Both the warp and woof must you

Entwine but of the woof there must be more

Than of the warp. Don this, for, if you do, 580

Your hair stays still, not shaking everywhere.

Be stoutly shod with ox-hide boots which you

Must line with felt. In winter have a care

To sew two young kids’ hides to the sinew

Of an ox to keep the downpour from your back,

A knit cap for your head to keep your ears

From getting wet. It’s freezing at the crack

Of dawn, which from the starry sky appears

When Boreas drops down: then is there spread

A fruitful mist upon the land which falls 590

Upon the blessed fields and which is fed

By endless rivers, raised on high by squalls.

Sometimes it rains at evening, then again,

When the thickly-compressed clouds are animated

By Thracian Boreas, it blows hard. Then

It is the time, having anticipated

All this, to finish and go home lest you

Should be enwrapped by some dark cloud, heaven-sent,

Your flesh all wet, your clothing drenched right through.

This is the harshest month, both violent 600

And harsh to beast and man – so you have need

To be alert. Give to your men more fare

Than usual but halve your oxen’s feed.

The helpful nights are long, and so take care.

Keep at this till the year’s end when the days

And nights are equal and a diverse crop

Springs from our mother earth and winter’s phase

Is two months old and from pure Ocean’s top

Arcturus rises, shining, at twilight.

Into the light then Pandion’s progeny, 610

The high-voiced swallow, comes at the first sight

Of spring. Before then, the best strategy

Is pruning of your vines. But when the snail

Climbs up the stems to flee the Pleiades,

Stop digging vineyards; now it’s of avail

To sharpen scythes and urge your men. Shun these

Two things – dark nooks and sleeping till cockcrow

At harvest-season when the sun makes dry

One’s skin. Bring in your crops and don’t be slow.

Rise early to secure your food supply. 620

For Dawn will cut your labour by a third,

Who aids your journey and you toil, through whom

Men find the road and put on many a herd

Of oxen many a yoke. When thistles bloom

And shrill cicadas chirp up in the trees

Nonstop beneath their wings, into our view

Comes summer, harbinger of drudgery,

Goats at their fattest, wine its choicest, too,

The women at their lustiest, though men

Are at their very weakest, head and knees 630

Being dried up by Sirius, for then

Their skin is parched. It is at times like these

I crave some rocky shade and Bibline wine,

A hunk of cheese, goat’s milk, meat from a beast

That’s pasture-fed, uncalved, or else I pine

For new-born kids. Contented with my feast,

I sit and drink the wine, so sparkling,

Facing the strong west wind, there in the shade,

And pour three-fourths of water from the spring,

A spring untroubled that will never fade, 640

Then urge your men to sift the holy corn

Of Demeter, when Orion first we see

In all his strength, upon the windy, worn

Threshing-floor. Then measure well the quantity

And take it home in urns. Now I urge you

To stockpile all your year’s supplies inside.

Dismiss your hired man and then in lieu

Seek out a childless maid (you won’t abide

One who is nursing). You must take good care

Of your sharp-toothed dog; do not scant his meat 650

In case The One Who Sleeps by Day should dare

To steal your goods. Let there be lots to eat

For both oxen and mules, and litter, too.

Unyoke your team and grant a holiday.

When rosy-fingered Dawn first gets a view

Of Arcturus and across the sky halfway

Come Sirius and Orion, pluck your store

Of grapes and bring them home; then to the sun

Expose them for ten days, then for five more

Conceal them in the dark; when this is done, 660

Upon the sixth begin to pour in jars

Glad Bacchus’ gift. When strong Orion’s set

And back into the sea decline the stars

Pleiades and Hyades, it’s time to get

Your plough out, Perses. Then, as it should be,

The year is finished. If on stormy seas

You long to sail, when into the dark,

To flee Orion’s rain, the Pleiades

Descend, abundant winds will blow: forbear

To keep at that time on the wine-dark sea 670

Your ships, but work your land with earnest care,

As I ordain. So that the potency

Of the wet winds may not affect your craft,

You must protect it on dry land, and tamp

It tight with stones on both sides, fore and aft.

Take out the plug that Zeus’s rain won’t damp

And rot the wood. The tackle store inside

And neatly fold the sails and then suspend

The well-made rudder over smoke, then bide

Your time until the season’s at an end 680

And you may sail. Then take down to the sea

Your speedy ship and then prepare the freight

To guarantee a gain, as formerly

Our father would his vessels navigate.

In earnest, foolish Perses, to possess

Great riches, once he journeyed to this place

From Cyme, fleeing not wealth or success

But grinding poverty, which many face

At Zeus’s hands. Near Helicon he dwelt

In a wretched village, Ascra, most severe 690

In winter, though an equal woe one felt

In summer, goods at no time. Perses, hear

My words – of every season’s toil take care,

Particularly sailing. Sure, approve

A little ship but let a large one bear

Your merchandise – the more of this you move,

The greater gain you make so long as you

Avoid strong winds. When you have turned to trade

Your foolish mind, in earnest to eschew

Distressful want and debits yet unpaid, 700

The stretches of the loud-resounding sea

I’ll teach you, though of everything marine

I am unlearned: yet on no odyssey

Upon the spacious ocean have I been –

Just to Euboea from Aulis (the great host

Of Greeks here waited out the stormy gale,

Who went from holy Greece to Troy, whose boast

Is comely women). I myself took sail

To Chalchis for the games of the genius

Archidamas: for many games had been 710

Arranged by children of that glorious,

Great man and advertised. I scored a win

For song and brought back home my accolade,

A two-eared tripod which I dedicated

To the Muses there in Helicon (I made

My debut there when I participated

In lovely song). Familiarity

With ships for me to this has been confined.

But since the Muses taught singing to me,

I’ll tell you aegis-bearing Zeus’s mind. 720

When fifty days beyond the solstice go

And toilsome summer’s ending, mortals can

Set sail upon the ocean, which will no

Seafarers slaughter, nor will any man

Shatter his ship, unless such is the will

Of earth-shaking Poseidon or our king,

Lord Zeus, who always judge both good and ill.

The sea is tranquil then, unwavering

The winds. Trust these and drag down to the sea

Your ship with confidence and place all freight 730

On board and then as swiftly as may be

Sail home and for the autumn rain don’t wait

Or fast-approaching blizzards, new-made wine,

The South Wind’s dreadful blasts – he stirs the sea

And brings downpours in spring and makes the brine

Inclement. Spring, too, grants humanity

The chance to sail. When first some leaves are seen

On fig-tree-tops, as tiny as the mark

A raven leaves, the sea becomes serene

For sailing. Though spring bids you to embark, 740

I’ll not praise it – it does not gladden me.

It’s hazardous, for you’ll avoid distress

With difficulty thus. Imprudently

Do men sail at that time – covetousness

Is their whole life, the wretches. For the seas

To take your life is dire. Listen to me:

Don’t place aboard all your commodities –

Leave most behind, place a small quantity

Aboard. To tax your cart too much and break

An axle, losing all, will bring distress. 750

Be moderate, for everyone should take

An apt approach. When you’re in readiness,

Get married. Thirty years, or very near,

Is apt for marriage. Now, past puberty

Your bride should go four years: in the fifth year

Wed her. That you may teach her modesty

Marry a maid. The best would be one who

Lives near you, but you must with care look round

Lest neighbours make a laughingstock of you.

A better choice for men cannot be found 760

Than a good woman, nor a worse one than

One who’s unworthy, say a sponging mare

Who will, without a torch, burn up a man

And bring him to a raw old age. Beware

Of angering the blessed ones – your friend

Is not your brother – treat them differently.

But if you don’t, don’t be first to offend.

Don’t lie. If he treats you offensively

In word or deed, then you should recompense

Him double, then, if he would be again 770

Your friend and pay the price for his offence,

Then take him back. They are all wretched men

Who go from friend to friend, so let your face

Not falsify your nature. Let none be

Able to call you comrade of the base

Or one who fights men of integrity

Or over-friendly or no friend at all.

Don’t chide a man for his pennilessness

That devastates and turns one’s soul to gall,

Because it is the Deathless Ones’ largesse. 780

A man’s best trait’s a thrifty tongue. Malign

Someone and you will very likely hear

Worse of yourself. When you are out to dine

With many folk at common feasts, don’t smear

Another, for the happiness is fine,

The cost a trifle. Wash your hands before

You start to sacrifice the sparkling wine

To Zeus or other gods – they’ll hark no more

And spit back all your prayers. Don’t urinate

Towards the sun, and when you’re travelling 790

Do not upon the highway micturate,

Nor off it either. From your frame don’t fling

Your garments – to the gods belongs the night.

A wise and reverent man will sit beside

The courtyard wall which keeps him out of sight.

Your sexual parts do not reveal but hide

Then after you make love. Don’t sow your seed

After a funeral, rather, having fed

At a god’s feast you should perform the deed.

When you a lovely stream of water find, 800

Don’t cross it till you’ve looked into that rill

And prayed and washed your hands in it. If you

Should cross with hands and errors unpurged still,

The gods will visit you with penance due

And cause you pain. And do not, when you’re dining

At a great feast to honour the gods, cut through

The dry shoots from the five-branched plant with shining

Iron, nor in the mixing-bowl, when you

Are drinking, leave the ladle - fatal blend!

Don’t leave your house half-built in case a crow 810

Should perch on it and misery portend.

A pot that is unblessed can bring you woe,

Therefore don’t eat or wash from it. Permit

No twelve-year- or twelve-month-old to be sat

Upon a sacred monument, for it

Will make him womanish, and make sure that

You don’t wash in a basin that has been

Just handled by a woman – punishment,

Should you do this, will for a time be keen.

If you should find a sacrifice unspent 820

Of flame, do not belittle things that we

Know nothing of – a god is angered thus.

In springs or rivers flowing to the sea

Don’t urinate – this point is serious.

It’s better not to vent your bowels there:

Thus you’ll stay fee of mortals’ wicked chat,

Which, though lightweight, is difficult to bear

And hard to lose. Such idle talk as that

Will not completely die when manifold

Folk use it, for it’s godlike. And observe 830

The days Zeus sends; make sure your slaves are told

To do likewise. The day that’s best to serve

To portion out all food and oversee

All work’s the thirtieth. These are the days

Of Counsellor Zeus: all prudent men agree

This is the truth. Upon these days we praise

The gods: first, fourth and seventh. It was then

Gold-girt Apollo first beheld the light,

Born of Leto: on the eighth and ninth day, when

The moon is waxing, it’s fitting and right 840

For men to work. When you would shear your sheep

Or pick your fruit, the twelfth and eleventh days

Are good, although it’s better that you keep

The twelfth, for then, beneath the morning’s rays,

The spider spins its web and floats in space

While clever ants their store are harvesting.

Your wife may then set up her loom and face

Her coming toil. No time for scattering

Your seeds in this month is the thirteenth, when

It’s best to raise your plants, though they’re unfit 850

For setting on the sixth, while yet for men

It is a good day to be born, though it

Is not for females, who should not be wed

Upon this day. Days One to Five well may

Inflict ill luck on women brought to bed

Of girls, but geld your kids and lambs that day

And build a sheepfold. Male births, though, create

Good luck, but boys born then will love to lie,

Taunt, flatter, chat in secret. On Day Eight

Geld boars and bawling bulls, then, by and by, 860

Upon the twelfth the labouring mules should be

Castrated too. The twentieth births males

Of wisdom. On the tenth prosperity

Attends male births, while wellbeing prevails

For girls upon the fourth. That time is fair

For training shuffling oxen, sheep as well,

And sharp-toothed dogs and labouring mules. Take care

To shun the fourth, at both its wane and swell –

Such days will eat your soul. Bring home a bride

On the auspicious fourth. The fifth you ought 870

To shun, whose pains will make you terrified.

Upon the fifth, the Furies, it is thought,

Helped Strife birth Horkos, who would bring heartache

To perjurors. Upon the seventh, take care,

Upon the well-worn threshing-floor, to take

To cast Demeter’s holy kernels there.

Let wood be gathered by a carpenter

To build your house, and let him bring enough

To build a ship and start constructing her

Upon the fourth. The ninth becomes less rough 880

Towards nightfall. The first ninth is quite free

Of woe for men and fine for coitus

For either sex and never totally

Unlikely, while the most salubrious

For opening up of jars and coupling

Your oxen, mules and speedy steeds (it’s known

To few) is the twentieth. You must bring

Upon that day the swift, oared ship you own

Down from her dock into the wine-dark sea:

This day by few is called its proper name. 890

Broach casks upon the fourth, for markedly

This is a holy day. Few, too, can claim

To know the twenty-first’s best at cockcrow,

The worst at dusk. These are of greatest use,

The rest are luckless, fickle, bland. Few know

These things, although opinions are diffuse.

From stepmother to mother goes each day.

Happy are they who know that these days bless

All men, guiltless before the gods, while they

Watch omens and avoid all wickedness. 900

The end of Hesiod's Work and Days