Bion

Lament for Adonis and The Lament for Bion

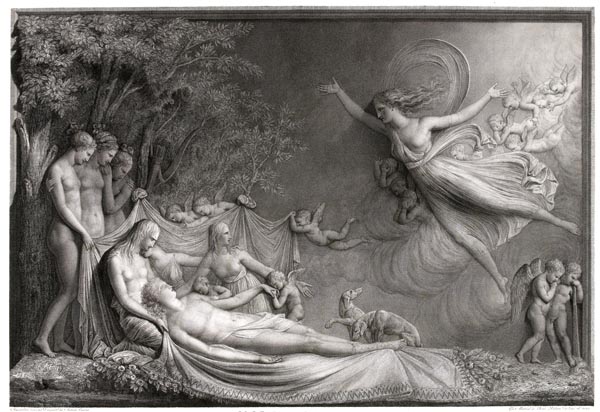

Venus mourning the dead Adonis - Antonio Canova (1800)

The Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lament for Adonis

- Translator’s Introduction

- The Lament

- The Lament for Bion

- Translator’s Introduction

- The Lament

- Notes on the Text

Lament for Adonis

Translator’s Introduction

The Lament for Adonis is attributed to Bion (fl. c100BC), a Greek poet, of ancient Lydia (now Izmir, Turkey). He was noted as a poet of the countryside, writing in the Doric dialect and, with Moschus and Theocritus, is one of a trio of major bucolic poets writing in that period. His work, of which this lament and a few fragments survive, was alluded to by Catullus and Ovid, and influenced later poems of lament, notably Shelley’s ‘Adonais’, his elegy for Keats. The Lament survived in two medieval manuscripts only.

The cult of Adonis was of near-Eastern origin (the name derives from the Canaanite word for ‘lord’), Adonis (in Greek myth the son of Cinyras, King of Cyprus) being worshipped as consort of the Canaanite great goddess, Astarte. His attributes were inherited from the earlier Mesopotamian Tammuz, consort of the goddess Ishtar. Adonis was also considered, in Greek mythology, to be a sometime consort of Persephone, the Maiden, the daughter of Demeter the harvest goddess. Persephone was fated to spend the winter months in the underworld as queen to Hades, its god, who had abducted and raped her, and she acted therefore as a link between the earth above, and its subterranean equivalent.

Adonis’ festival, the Adonia, was celebrated annually by women, who mourned his death, as the consort of Aphrodite. The festival is known of in classical Athens, though other sources provide evidence for the ritual elsewhere in the Greek world. Mythologically, Venus-Aphrodite, the goddess of love, and a manifestation of the great fertility Goddess of ancient times, was born from the sea, near her island of Cythera, or near Cyprus (Paphos is located on its southwest coast), in both of which she was worshipped. Hence her epithets, ‘Cytherea’, ‘Cypris’, and ‘the Paphian’. Frazer (in ‘The Golden Bough’) considered the lament for Adonis another instance of a vegetation rite, in which the solar consort of the Goddess meets his death in the winter, to be resurrected (or replaced) in the spring. The Greek rite seems to have been performed at other times also, according to the planting and harvesting seasons in various regions. Shelley deepens his tribute to Keats, by considering him ‘one with Nature’ so identifying the dead poet with the earlier mythological figure, and the natural cycles of death and renewal.

Poetic lament is thus an ancient and archetypal literary form of the act of mourning. Shakespeare’s poem ‘Venus and Adonis’ retells the myth, but derives rather from Ovid’s account (in Metamorphoses: Book X). Among modern writers, the theme of lament is significant in Rilke’s ‘Duino Elegies’, where Lament is personified in the form of a young girl. Rilke views the realms of life and death as a single whole, a perspective which the vegetation rituals were, in a sense, designed to confirm and celebrate. Lorca’s ‘Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías’, the matador, also contains echoes of Bion’s poem, the horn of the bull replacing the tusk of the boar that killed Adonis, with the poem’s rhythmic repetitions creating similar effects to those of Bion.

The Lament

I mourn now for Adonis: he is dead, the fair Adonis;

‘Lovely Adonis is dead’, echo the servants of Love.

Sleep no more, fair Cypris, under your purple covers,

Wake to your pain; in black robes, beat your breast;

Cry out, to all the world: ‘Lovely Adonis is dead’.

So, I mourn for Adonis; so, echo the servants of Love.

Wounded in the thigh, fair Adonis lies on the hill,

The white tusk piercing the white; Cypris shivers

With cold, for the black blood drips on his flesh,

Staining the white; the eyes neath his brows grow dim.

The rose flees from his lips; that kiss dies, and is gone

Cypris shall know no more. Though Cypris would kiss

Adonis as he lies dying, he knows naught of her kiss.

So, I mourn, for Adonis; so, echo the servants of Love.

Cruel, oh cruel, is the wound in his thigh, crueller

The wound that has pierced Cytherea’s heart.

Loud wail his hounds; and the Nymphs on the hill,

Loud their cry; Aphrodite lets down her long tresses,

Wanders the woodland, distraught, and un-sandalled.

Although the briars tear her, the brambles mar her,

As she yields an offering, a sacrifice of her blood,

She runs yet through the glades, bathed in her tears,

Bewails her Assyrian spouse, the lad that she loves.

Now the black blood pools at his navel; his breast

Is dark with the dark blood that runs from his thigh;

And crimson is all that was once white as the snow.

‘Woe, woe, for Cytherea!’ they cry, the servants of Love.

Lost is her lovely lord; her beauty too lies victim;

While Adonis yet lived, Cypris was lovely to see.

Her beauty died with him: ‘Woe for Cypris, woe!’

Cry all the hills, as the woods cry ‘Woe for Adonis!’

The rivers and streams weep Aphrodite’s sorrow;

The mountain springs shed tears for the dead Adonis,

The flowers redden in sympathy; Cythera, her isle,

Every slope, every valley there, mourns in pity:

‘Woe to Cytherea, for the lovely Adonis is dead.’

Echo returns the cry: ‘The lovely Adonis is dead.’

Who would not weep at the tale of Cypris’ love?

She saw the mark of Adonis’ unquenchable wound;

She saw his pale thigh drowned in a pool of blood;

She raised her fervent lament: ‘Ill-starred Adonis,

Let me hold you, my own Adonis, for one last time.

Let me embrace you, once more, touch lip to lip.

Stay a while my Adonis, grant me this one last kiss.

Kiss me, once more, your kisses might yet have life,

Till you faint at last, your sweet breath in my mouth,

Till I’ve drawn your spirit deep into my loving heart,

To guard, as myself, now that ill-starred you flee me,

Far, far away, Adonis, to where the Acheron flows,

And Hades, its hated king, governs; while, in pain,

I must live on, as a goddess, unable to follow.

O, Persephone, take my spouse, take him if you must.

You are more powerful than I. To you go the fairest,

While I am helpless, where sorrow is now unending.

I cry for you, Adonis, my dying one, for my loss;

You are dying, and my love has fled like a dream.

Widowed is Cytherea, and empty the house of Love;

Her weaving all undone. Far too bold, my fair one,

Your hunting; were you not mad to wrestle the boar?’

Such was Cypris’ lament. So cried the servants of love:

‘Woe, woe, for Cytherea! The lovely Adonis is dead!’

The Paphian’s tears flow, likewise the blood of Adonis,

And the earth blooms beneath the blood and the tears.

Roses spring from the blood, anemones from the tears.

I mourn for fair Adonis: the fair Adonis lies dead.

Mourn your spouse in the woods, no longer, Cypris.

The lonely thicket is no good place, for such as he.

Cytherea, grant Adonis your couch in death, as in life,

For, in death, he’s lovely; as lovely as if he’s asleep.

Set him down on the soft coverlet, where he slumbered,

On that couch of solid gold, where he spent his nights

In sacred sleep with you; it yearns for the dead Adonis.

Strew garlands of flowers around him, and upon him,

Now that Adonis is dying, let all fair flowers die too,

And pour on him Syrian unguents, sweet scented oils.

Make an end of all; your all, Adonis, has perished.

There delicate Adonis lies, in a shroud of purple,

And the servants of Love lift up their cries of lament,

Their locks shorn for Adonis; one places his bow

Beside him, others the quiver, the feathered arrows;

One takes off his sandals, another brings water,

In a golden basin, another now laves his thigh,

While one, behind him, cools him with his wings.

‘Woe, woe, for Cytherea!’ they cry, the servants of Love.

Hymenaeus has quenched the torches by the door,

And scattered the wedding-wreaths upon the ground.

No more do they sing of marriage, sweet marriage,

‘Woe, for Adonis’, not ‘Hail, Hymenaeus’, they sing.

The Graces weep for the son of Cinyras, crying:

‘The lovely Adonis is dead!’, one to another,

More filled with lament their cry, than is the Paean;

And even the Fates weep and wail for him, calling

Adonis’ name in their chant, though he gives no ear.

He would rise again, but the Maiden won’t free him.

Cease weeping and beating your breast now, Cytherea,

For you’ll weep and lament again, come another year.

The Lament for Bion

Translator’s Introduction

The Lament for Bion was long attributed to Moschus of Syracuse (fl. c150BC), though Bion was the younger man (fl. c100BC), but is now thought to have been written by a pupil of Bion. Like Bion’s own ‘Lament for Adonis’ it had a great influence on subsequent elegies for dead poets, for example Deschamps’ double-lament for Machaut, and Milton’s ‘Lycidas’. More of a pastoral, and less the ritual invocation which Bion’s lament echoes, it shows the deep roots of the Sicilian literary tradition, examples of which are the poetry of Jacopo da Lentini and his school in the thirteenth century, and Salvatore Quasimodo’s evocative verse in the twentieth.

Note that Hyacinthus was turned into a flower, according to Ovid (Metamorphoses, X), though the lack of markings on the modern hyacinth, suggest that the Greek flower intended was that of larkspur, iris, or some other plant.

The Lament

Mourn, woodland glades, I pray, and Dorian waters,

You, streams and rivers, weep for the lovely Bion.

Lament you, trees and glades, let tears flow down.

Flowers, let your living clusters bow in sorrow.

Seem redder with weeping, anemones and roses;

Flowers of Hyacinthus, cry the marks on your petals,

Cry your ‘AIAI’ of woe; fair Bion the singer is dead.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

You nightingales, that mourn, among the dense leaves,

Tell of this now, sing out to Arethusa’s Sicilian fount,

That Bion the tender of herds is dead, and, with him

The music has died; dead the voice of the Dorian lyre.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

You swans, shed tears of grief, on Strymonian shores;

Sing your melancholy notes, your song of mourning,

With such a voice as you utter when old, and dying.

Cry to all the Oeagrian maidens, cry out to them all,

All the Bistonian nymphs: ‘The Dorian Orpheus is dead’.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

He sings no more, the beloved tender of herds.

He sings no more beneath the solitary oak;

Seated by Hades he sings now a Lethean song;

The hills are mute, and all the wandering herd

Raise the bull’s loud moan, and refuse to graze.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Bion, your sudden end, Apollo himself lamented,

The Satyrs grieved, and Priapus, in mourning, wept.

Pan sighed for your voice, and the fountain nymphs

Lamented among the trees; their streams, bright tears.

And Echo, among the rocks, she mourned your silence,

No longer repeating your song, and, with your loss,

The trees let fall their fruit, and the flowers withered.

The ewes yield none of their milk, the bees no honey,

The honeycombs are dry, on account of their sorrow,

For the hives yield no sweetness now yours is gone.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Never so sad the cries of the Siren, on the shore,

Never so sad the nightingale’s song in the glade,

Never so sad the lament of the swallows on the hill.

Never did Alcyone weep so, for her drowned Ceyx,

Never did the kingfisher cry so, on the dark waves.

Nor did the birds of Memnon grieve so, over the tomb

Of that Son of the Dawn, in the valley of Morning,

As rose the lament in the air at the death of Bion.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

The swallows, the nightingales, whom he delighted

In teaching to sing, while seated there, under a tree,

Now sang out their song, and others cried the refrain,

‘Grieve then, you birds, in sadness, and so will we.’

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Who shall play now on your reed-pipe, thrice-beloved?

Who so bold as to set their lips to the sounding reed?

For your lips, and your breath, seem as if living yet,

And midst the reeds, the sound of your song yet stirs.

Shall I bear your flute to Pan? Even he would fear

To set it to his lips, lest he seem but second to you.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Galatea too, she weeps at the loss of your music,

The music she used to love as she sat on the shore;

The Cyclop’s music was harsher, and she fled him,

Yet she looked on you more gladly than on the sea.

Now, as she sits on the shore, the waves are forgot,

Although she still leads your lowing herd to pasture.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Herdsman, with you, are the gifts of the Muses lost;

The maidens’ lovely kisses, the lads’ sweet lips.

About your grave the dishevelled mourners weep,

Even Cypris is filled with a longing for your kiss,

More than that she had of Adonis, as he lay dying.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Clear-sounding River, this brings you a second grief,

New sorrow, fair Melos. Your Homer died long ago,

That sweet melodious mouthpiece of yours, Calliope,

For whom you mourned, weeping sad floods of tears,

Till all the ocean was swelled by your dire lament.

Now, all wasted in sorrow, you mourn another son.

Both loved the sacred springs, for the former drank

At Pegasus’ fount, the other of Arethusa’s waters.

One sang of Helen, fair daughter of Tyndareus,

Achilles, born of Thetis, and Menelaus Atreus’ son.

The other sang not of war and grief, but sang of Pan.

A herdsman, he played and sang as he grazed his herd,

He fashioned his reed-pipes, and milked the heifers,

He taught lads how to kiss, and fostered you, Eros,

And took you to heart, and conquered you, Aphrodite.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Every city and every town, mourns you, Bion.

Ascra grieves more for you than for Hesiod.

The woods of Boeotia miss not Pindar more.

Lesbos weeps not so tenderly for Alcaeus,

Nor Teos for Antimachus, he who was hers.

More than Archilochus, Paros yearns for you;

Mytilene, more than for Sappho, weeps forever,

Syracuse for Theocritus. As for Ausonia, hers

Is the sad lament that I sing; I, no stranger

To pastoral song, but heir to the Dorian Muse,

My inheritance all that you taught me, for you

Left but your dross to others, to me your song.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Alas, when the mallows wither in the garden,

And the green parsley, and the feathery dill,

They live again, they rise the following year.

But we mortals, so wise, so strong, so mighty,

Lie, unhearing, under the earth, when we die,

Sleep long and sound, a sleep without end, un-waking.

So, you will lie in the earth, your coverlet silence.

Though the Nymphs grant the little tree-frog his song,

I bear them no ill-will; it’s scarcely music he makes.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Poison, it was, that entered your mouth, sweet Bion,

Poison you drank, how was it not turned to sweetness?

What man was so cruel as to mix that drink, so vicious

As to answer your summons, for, there – the music died.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Yet Justice overtakes all. As for myself, I grieve;

This sad song is my lament at your death. Could I

Like Odysseus, Orpheus, descend to Tartarus, now,

Or Herakles long ago, to Hades’ house I’d come,

And if you sing for the god, perhaps I’d see you,

And hear you there. Play, then, a song for the Maiden,

A song of Sicily; sing some sweet pastoral air.

She was of Sicily too, she danced on Etna’s shores,

She knows the Dorian music; and nor will you go

Lacking a gift; for as she granted Orpheus, once,

For his sweet sounds, Eurydice’s chance to return,

You too she’ll give back to the hill. Had I the strength

Of your lyre, I would sing, there, to Hades myself.

Be first now, Sicilian Muse, with your song of lament.

Notes on the Text

Oeagrus was king of Thrace, and reputedly the father of Orpheus and Linus. Bistonia was a part of central southern Thrace, the term sometimes being used for the whole. Hades or Pluto, the Roman Dis, was the god of the underworld. Lethe was the river of forgetfulness. Ceyx was king of Trachis, Alcyone his Thessalian queen; Ceyx was drowned at sea, and Alcyone mourned him, both being transformed into kingfishers, which occasionally haunt saltwater estuaries (see Ovid: Metamorphoses, XI). Memnon, the son of Eos, the Dawn, was granted immortality at her request, and the smoke of his funeral pyre turned to a flock of birds (see Ovid: Metamorphoses, XIII). Galatea was wooed in vain by the Cyclops (see Ovid: Metamorphoses, XIII). Cypris is Venus-Aphrodite mourning for Adonis (see Bion: The Lament for Adonis). The shores of the river Meles, flowing through Smyrna, were the traditional birthplace of Homer. Calliope is the Muse. Pegasus’ fount is the Hippocrene spring, on Mount Helicon, sacred to the Muses. Arethusa’s fount is on the island of Ortygia, at Syracuse in Sicily. Ascra in Boeotia was the birthplace of Hesiod. Ausonia was the Greek name for southern Italy. The Maiden is Persephone.