Gottfried von Strassburg

Tristan: Part V - ‘Tantris’ in Ireland

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Last Modified 6th January 2020

Contents

- Tristan sails for Ireland to seek a cure.

- Tristan reaches Dublin.

- Tristan is helped ashore.

- Queen Iseult is informed of his sad state.

- The queen sets about his cure.

- ‘Tantris’ is cured of his wound.

- ‘Tantris’ acts as tutor to Iseult the Fair.

- ‘Tantris’ seeks leave to return home.

- Tristan lands in Cornwall.

- Tristan is the victim of envy.

- An embassy to Ireland is agreed.

- Tristan prepares to return to Ireland.

- The envoys reach Ireland.

- The encounter with the dragon.

- The steward seeks out the dead dragon.

- The steward claims the victory.

Tristan sails for Ireland to seek a cure

I turn now to the tale once more;

Once Tristan had gained the shore

Without his steed, without his lance,

Crowds of folk did then advance,

Mounted or on foot, towards him,

In their thousands there to meet him.

Never had king or kingdom known

So joyous a day, for he alone

Had brought an end to all their shame

And misery; all said the same,

That he had brought them great honour.

As to the wound which he did suffer,

They sorrowed over it, and grieved,

Yet thinking he had but received

A small hurt, they thought it naught,

And thus to the palace they brought

The man, and unarmed him straight,

Saw to his comfort, then did wait

On his ease, as each might suggest.

But now the doctors, the very best

To be found throughout the land,

Were summoned and their command

Of medicine they demonstrated.

Yet to what end? For their belated

Treatment saw him none the better.

Though they delivered to the letter,

In application of their learning,

It proved of no advantage to him.

For the venom was such, they found,

It spread within, and all around

His body, till a ghastly hue

Tainted his flesh; yet naught they knew

Allowed the poison’s removal;

He seemed unrecognisable;

Moreover the site of the blow

Gave off an evil stench, one so

Noisome life became a burden,

And his own body wearisome.

Yet his grief was greater when

He realised that it gave offence

To the many friends who stood

By him, and thus he understood

More and more, the whole meaning

Of Morolt’s earlier warning;

Yet he had heard, in days past,

How lovely Morolt’s sister was,

And of Iseult’s accomplishments,

For all men paid her compliments.

There was a saying in those lands,

Those neighbouring on her Ireland,

To which the people would refer,

Whenever her name did occur:

‘Iseult the fair, Iseult the wise,

Shining bright as morning skies.’

Now Tristan, that care-laden man,

Knowing of this, conceived a plan

That aimed at his recovery;

For he saw it could only be

Through the skill of one, I ween,

Who of the subtle arts was queen.

Although he still was full of doubt

As to the bringing it about.

He summarised it, in a breath:

In this matter of life or death,

There was little to choose between

Placing his life with the queen,

Or this death-like extremity.

He set his mind accordingly,

On setting sail for Ireland,

To seek a cure in foreign land,

If God but willed that it might be

That such were now his destiny.

So for his uncle now he sent,

And told him all his true intent,

As friend to friend, and how that he

Would seek, for his infirmity,

The cure Morolt had spoken of.

Mark liked it, and he liked it not.

Yet one must suffer as one may

The trouble met upon one’s way;

To choose the lesser of two evils,

As fate dictates, proves ever useful.

Together they agreed his course

Of action, how he would perforce

Effect his journey, how they might

Supress the news of sudden flight

To Ireland, and spread the rumour

That he had simply left however,

For Salerno, to take the cure.

When this was settled, and much more,

They summoned to them Curvenal,

And told him all that must befall,

Their common purpose and intent,

And Curvenal gave his consent

To accompanying Tristan,

To live or die his loyal man.

A barque, with a small skiff as well,

Was made ready, as evening fell;

Food and water were laid aboard,

And all else for the voyage stored.

Then, with a quiet show of grief,

Tristan was set on deck, in brief,

In such great secrecy that none

But those who witnessed the thing done,

Knew of his journey; at the end,

He did his own affairs commend

To Mark, with all his retinue,

Requesting that he should eschew

All thought of dispersing aught

Of his, till certain news arrive

As to whether he was yet alive.

His harp he did request also,

That being all he asked for though,

All of his own he sought to take.

Then they upon their course did make,

And soon they were well out to sea,

The crew of eight had faithfully

Pledged their lives, and in God’s name,

Sworn not to swerve from the same

Obeying Tristan’s every command.

When they had parted from the land.

King Mark, I know, gazed on the sea,

With little pleasure; twould seem to me,

This parting pierced him to the heart,

Bone-deep, and yet, despite the start,

To both the voyage brought happiness

And a large measure of success.

Now when all the nobles heard

The tale of what had thus occurred,

The suffering that then prevailed,

When Tristan for Salerno sailed,

To seek a cure; his state on shore,

And now at sea, then not one more

Tear could they have shed had he

Been their own child in misery.

And since Tristan had suffered this

Sad mischance all in their service,

It moved their hearts more deeply still.

Tristan reaches Dublin

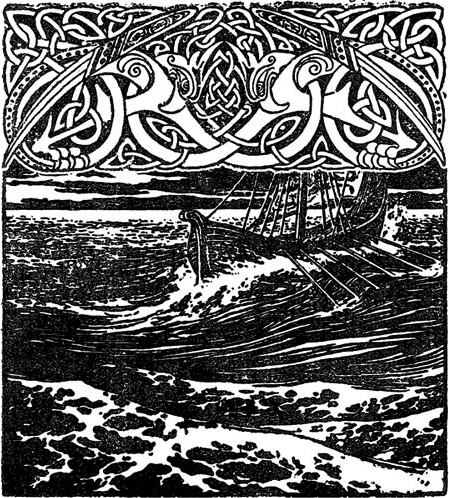

‘Tristan's voyage to Ireland’

The Story of Tristan and Iseult , Vol I - Jessie L Weston and Caroline Watts (p57, 1907)

Internet Archive Book Images

TAXED to the utmost of his will

And strength, Tristan sailed to Ireland,

Steered by the experienced hand

Of his master-mariner, and when

The ship drew near to land again,

Tristan told him to set a course

For Dublin, the capital, perforce,

Being aware that the wise queen,

Dwelt there; there she must be seen.

They sailed swiftly to the city,

And soon could discern it clearly.

‘See, my lord!’ cried the master,

‘Tis the city, give your order.’

‘We’ll drop anchor here,’ Tristan

Replied, ‘and not too near the land,

And wait here, in the fading light,

And spend a part thus of the night.’

So they dropped anchor there and lay

Offshore that evening, and when day

Was done, then in the dark of night

Tristan had them heave to, in sight

Of the city, and this being done,

Once the ship had taken station

Half a mile from the harbour,

Tristan gave a further order.

He asked now for the poorest clothes

In the barque and, dressed in those,

Had them remove him straight away,

Into the skiff and, with scant delay,

Hand him enough food and water,

For three days or four, thereafter,

And set his harp down in the boat,

And prepare to set the skiff afloat.

As he desired, the crew wrought all.

And then he summoned Curvenal,

Calling, before him, all the crew,

Addressed him, and the others too:

‘Friend Curvenal, I ask you to take

Charge of the men and, for my sake,

Care for the ship and them, full well

And when you are home again, tell

Them to keep this, our secret, safe.

And reward them all, in good faith,

That they might say no word to any.

Go, return to Cornwall swiftly.

Greet my uncle, say I yet live,

And may be cured, if God give

His aid, and say to him that he

Should not sorrow now for me.

Say, if I’m destined to recover,

I’ll return ere the year is over;

And that if my affairs go well,

Some that news will swiftly tell.

But tell both the court and country

I died of my debility;

Say that I perished on the way.

Take care that my followers stay

In company, and do not disband.

See that they wait, and are on hand,

Through all the time I named to you;

But if no news has come to you

Within the year, treat me as lost.

God keep my soul, and at all cost

Look to your own self, set sail

You and my men and, without fail,

Go, safe and sound, to Parmenie,

And settle there, in our country,

Beside my dear father, Rual.

Ask him, from me, to care for all,

And through you, as he loves me,

Repay my love for him, faithfully,

Treating you handsomely and well,

And then to him my wishes tell,

Concerning those who have served

Till now; for, as they have deserved,

So he must thank them and, in this,

Reward each man for his service.

Thus, dear folk,’ he reached an end,

‘To God your lives I now commend;

Set me adrift then take your way,

And for God’s mercy I will pray;

Tis time that you put out to sea,

Sailing, now, for life, and safety;

For tis high time, fast fades the night,

And o’er the sea twill soon be light.’

Tristan is helped ashore

AND so, with many a lament,

Many a pang of grief they went,

And left him there, tearfully,

Adrift on the turbulent sea.

No parting ever pained them so.

Every faithful man doth know,

Who e’er had a faithful friend,

And swore to love him to the end,

The sore distress Curvenal knew,

And yet, though he was ever true,

Heavy of heart, and suffering,

He kept a true course in parting.

Tristan was thus left there alone,

Drifting to and fro, to moan,

In anguish, and in misery,

Till dawn broke brightly o’er the sea.

Now when the Dubliners caught sight

Of the craft, in the morning light,

All pilotless, upon the wave,

They sent a crew at once to save

Any that might yet be aboard,

And learn what aid they might afford.

Now, while they were drawing near,

They saw naught, but yet could hear,

As they were swiftly approaching,

The sweet strains of a harp, floating

O’er the water, to their delight.

And then a voice did there alight,

Of one who sang, enchantingly,

So that they thought it wondrously

Strange, in truth a marvellous thing;

And as long as that voice did sing,

They remained so, without moving,

While he harped, slowly drifting.

Yet the momentary pleasure,

Lasted not, for them to treasure,

For the sounds that were relayed,

Music hands and lips had made,

Issued not from deep within him;

His heart was not in the playing.

To music’s nature it doth belong,

That no artist can play for long

Unless their heart is in the task,

Though little it may seem to ask;

For, though it is a common thing,

That cursory mode of playing,

Heartless, soulless, unmelodic,

Tis scarce worth the name of music.

Though fair Youth made Tristan,

Divert her, with voice and hand,

By harping and singing for her,

It seemed, for that poor sufferer,

A vile torment and martyrdom,

To which his artistry had come.

And now, as Tristan ceased to play,

The other boat beside his lay.

Its crew grappled his vessel’s side,

And sought to see who was inside.

When they at last had sight of him,

And the sad condition he was in,

It troubled them that such music

Could be made, such sweet magic,

By his poor hands and lips, alone;

Yet, as one who should be shown

Fair greeting, for his fair playing,

They greeted Tristan, while asking

What fate he’d met with on the sea,

Seeking an answer, courteously.

‘All shall I tell you, said Tristan,

‘I was a minstrel, and so a man

Versed in the ways of the court;

When to be silent, when to talk,

Or play the lyre, or the fiddle,

The harp, or the rote right well,

Or smile, or tell a tale in jest.

I held my station with the best,

As all who are at court must do.

But I desired more than my due,

Having gained sufficient wealth

More than was good for my health.

I took up trade, and that has been

My undoing, as you have seen.

A rich merchant was my partner,

We filled a ship with whatever

Cargo pleased us, there in Spain,

And set sail for Britain, for gain.

Yet, once we were out at sea,

A band of brigands, furiously,

Attacked our vessel, then they stole

All we had loaded in the hold,

Regardless of value, everything,

Slaughtering every living thing,

My partner too; yet I survived,

Sore wounded tis true, but alive,

For from my harp they could see

I was born and bred to minstrelsy;

While I assured them it was so.

I begged them then to let me go,

Was granted this skiff and supplies

Enough to live on, to my surprise,

And I have drifted thus till now,

In pain, where’er the waves allow,

For well on forty days and nights,

Alone among their vales and heights,

Wherever the wind has driven me,

Or the savage seas have borne me,

Now one way, and now another,

Not knowing one from the other,

And even less where I was driven.

Now sirs, if you’d be forgiven,

And have our Lord reward you well,

Help me to where good people dwell!’

‘My friend,’ the crew then replied,

‘No help could ever be denied

Your sweet voice, and fine playing;

We’ll put an end to such straying,

For you shall float here no longer,

Helpless, while the wind grows stronger;

Whate’er it was that brought you here,

Wind, waves, or God, whom we revere,

We shall lead you, indeed, to land!’

And then they took his boat in hand,

And true to their word, skiff and all,

Into the harbour, no long haul,

They towed him, and there made fast,

Exactly as Tristan had asked;

And cried: ‘Look, minstrel, now behold

This fine city, and fair stronghold,

Know you what place this might be?’

‘No, good sirs, for tis new to me.’

‘Then we shall tell you; here at hand

Is Dublin; you are in Ireland!’

‘The Lord be praised, then,’ Tristan said,

‘Amongst good people am I led,

For one among you there must be

Who will show their kindness to me;

One here will grant aid and counsel.’

The boatmen made for the citadel

And told of their strange adventure

And their marvellous encounter

With this man, who scarce seemed

A wonder, and yet was, they deemed.

They related all that had occurred,

Telling their story, word for word:

How, while they were some way away,

They heard a harp, so sweetly played,

And a song, its notes accompanying,

God might well find to his liking,

If sung by all the heavenly choir.

There they’d discovered one in dire

Straits, a minstrel, wounded to death,

Like, indeed, to sigh his last breath.

‘Go now, and look, and there you may

See one who’ll die perchance this day,

Or this night, yet though he suffers

He has such spirit, among all others

You’ll not find one, in any land,

So little troubled, you understand,

By such sad and grievous mischance.’

Queen Iseult is informed of his sad state

A crowd of folk did then advance

And engaged him in conversation,

Asking him question after question,

Though he repeated the same story.

Then they asked him to play sweetly

On his harp, and he, willingly,

Set all his mind on their request,

And sought to deliver of his best.

For whate’er he could sing or play

To win their favour, on that day,

That was his wish, and he did so.

The poor minstrel’s singing though

And his harping, done so sweetly,

Moved his audience to pity;

Twas beyond his bodily strength.

So they had him moved, at length,

And saw him borne to a safe place,

Where a physician of their race

Would attend him diligently,

The people paying the man’s fee,

And do whatever he might please

To bring the minstrel help and ease.

All this was done, and the doctor

Did all that he could do; however,

Though the sage worked all his skill

To treat him and ease him, still

It did the sufferer little good.

The tale of this was understood

Throughout the city of Dublin;

As one group left, the next were in

That house, all voicing their lament,

Grieving over this guest God sent.

And in a while, there came a priest,

Who’d noted, ere the singing ceased,

The minstrel’s skill with hand and voice,

For the man was himself a choice

Performer there, on every kind

Of instrument that comes to mind,

And knew all songs that were sung,

And was master of many a tongue,

For he had devoted all his days

To learning and to courtly ways.

This man was tutor to the queen,

A member of her suite, I mean,

And then, from her childhood on

He had sharpened her perception,

With many a goodly precept, and

To many an art he turned his hand,

Learning that the queen had sought.

And her daughter too he taught,

Iseult the Fair, that rarest girl

She of whom the whole wide world

Spoke, as does this tale of mine.

She was the loveliest of her kind,

And as she was her only daughter,

The queen had paid attention to her,

And her alone, from the moment

When the daughter showed intent

To play an instrument of choice

And learn the arts of hand and voice.

The priest too had her in his charge

He whose learning was writ large,

And sought to teach her all he knew,

Book-learning, and then music too,

And upon all stringed instruments.

Witnessing Tristan’s acquirements,

His skills and his capacity,

The priest was moved to deep pity

By the suffering he had seen,

And quickly went to find the queen.

He told her that, to her city,

Had come a man of quality,

A minstrel and yet, in a breath,

One suffering a living death,

Racked with pain, a wounded man,

And yet no man, born of woman,

Was e’er so skilful in his art,

Nor seemed so spirited at heart.

‘Ah,’ he cried, ‘most noble queen,

If but by you he might be seen,

In a place where you might be

And that miracle you might see

And hear, that of a dying man,

Who yet harps, as only he can,

And sings so finely and sweetly;

Though he is wounded so deeply

He can ne’er be cured, I vow,

For he is past all helping now.

His host, who is a fine physician,

Now despairs of his condition,

And has discontinued treatment,

Although it was his first intent

To cure him, having failed with all

The medicine at his beck and call.’

The queen sets about his cure

‘SEE now,’ the queen said, thoughtfully,

‘I’ll tell the chamberlain that, if he

Can stand to be moved from there,

They are to place him in my care,

To discover if, in his sad state,

He may yet be cured, soon or late.’

What she asked was soon achieved.

And once the queen had perceived

The anguish which he did suffer,

And viewed the wound’s ugly colour,

She knew there was venom within.

‘Ah, sad minstrel,’ she did begin

Her speech to him, ‘the true reason

For your plight’s a noxious poison!’

‘I knew it not,’ said Tristan, swiftly,

‘Such things are all unknown to me;

Yet, whate’er has been the treatment,

Naught has brought me improvement.

Who knows what life I yet may see?

Yet I know that naught is left to me,

But to place myself in God’s hands,

And live for as long now as I can.

Though if any pity my state,

If any can make my pain abate,

May God reward them! Help I need;

For this is living death, indeed!’

Then the wise lady, spoke again:

‘Tell me now, what is your name?’

‘My lady, I am called Tantris.’

Then, Tantris, take it not amiss,

If I profess that I shall heal you,

Whate’er I say, I will make true.

Take heart, and be now of good cheer!

For I shall be your doctor, here.’

‘My thanks to you, most gracious queen;

Like to those leaves forever green,

May your speech forever flourish,

And may your heart never perish,

So may your wisdom live forever,

To grant, to the helpless, succour.

And may your name honoured be

Now, and throughout eternity!’

‘Tantris,’ to this, the queen replied,

‘Let not my wish now be denied:

If your condition will permit,

Though you are weakened so by it,

I would be pleased to hear you play

Upon your harp, for all do say,

That you perform most skilfully.’

Oh, think naught of it, my lady!

For no sad misfortune of mine,

Shall deny you a wish so fine,

And I shall here display my art;

I shall play, with mind and heart.’

So, to him, his harp they brought.

And then the young princess they sought,

She, love’s true signet-ring, with which

His heart was to be sealed, through which

Twas kept from all the world, unknown,

Unseen, except by her alone,

Iseult the Fair; she came also,

And right closely did she follow

As Tristan took his harp and played.

His finest skills he now displayed,

Played better than he had before,

In hopes that all his woes were o’er,

Played not lifelessly, as a man

Half-dead, but as an artist can

When in the fullness of his powers,

As if he might play so for hours.

And then Tristan played so well

And sang so that, ere one could tell,

He had won, from all, their favour,

His fortunes now all set to prosper.

Yet as he played, now and elsewhere,

His wound gave off such odour there,

That none who came within its power

Could yet remain with him an hour.

‘Tantris,’ the queen now did say,

‘If ever there should come a day

When this odour shall leave you,

And people may remain with you,

Let me commend the young girl there,

The maiden, Iseult, to your care.

She studies hard, and she doth work

At books and music, will not shirk,

And given such brief time, as yet,

Little she learns doth she forget.

If you have greater skill than I,

Or her tutor’s, in aught, then try

Her knowledge, and then instruct her.

I shall repay you in another

Manner, for I shall now restore

Body and life to you once more,

Returning you to perfect health,

Which is better far than wealth.

I can grant you such, or deny

You my healing; in this, say I,

I hold the power in my hand!’

‘Indeed, if that is how things stand,’

The suffering minstrel replied,

‘If such indeed may heal the sick,

And I be cured so through music,

Then if God wills, I shall be healed!

Since your own thoughts do yield,

Most gracious queen, this intent

For your daughter, I must consent,

And all my reading, I believe,

Allows me now to thus conceive

A way to winning your goodwill,

Through her, if such I can instil.

And then I know tis true of me

That no one, of my years, can be

As skilful at playing on so many,

So rich and rare a variety

Of noble stringed instruments.

Whate’er your wish and your intent,

Ask; it shall be performed by me

To the best of my ability.’

‘Tantris’ is cured of his wound

THEY furnished a chamber for him

And all attention was shown him

That he required while, day by day,

They saw to his ease in every way.

Now he reaped good value from all

The caution he’d shown in Cornwall,

His wounded side there concealed,

From the Irishmen, by his shield.

Thus, his wound unknown to them,

In ignorance, they had sailed again,

While, had they known of his state,

They might have sought to relate

The tale of his wound; folk might

Think this was now a similar sight

To wounds Morolt had dealt in war,

And ponder then on what they saw.

And thus Tristan might have fared

Otherwise in all that he’d dared;

For now his foresight helped to save

His life; such prescience may pave

The path to profit and respect

For the prudent and circumspect.

But now, the wise and learned queen

Turning her mind to all she’d seen

Of his wound, was wholly intent

On healing one on whom she bent

All her skill, for whose life, I own

She would have laid down her own.

Her reputation too was at stake;

Yet who he was she did mistake,

For had she known whom she saw,

She would have hated this man more

Than she did love herself, yet she

Wrought all towards his recovery,

His comfort, and his well-being;

Setting her mind on his healing,

Was at that task, both night and day.

Yet there is naught that one can say

About this, for she knew him not;

Had she known twas he had fought

And slain Morolt, on whom her care

Was lavished, and the patient there,

Whom she was helping from death’s door,

Her enemy, then whate’er was more

Bitter than death she’d have granted

Him more readily than aught he wanted,

Than life, tis certain, yet good she knew

Of him, and good thus would she do.

Now if I were to speak at length

Of how Tristan regained his strength,

Of the queen’s skill in medicine,

Of her potions, how she did win

Him to health, would it achieve

A single thing? No, I believe

A seemly word sounds far better

In noble ears than any doctor’s.

I will refrain from all things here

That might indeed offend your ear

Or your feelings, I’ll say naught

In language not meant for court,

So that my story may not seem

Harsh or unpleasant in its theme.

Regarding my lady’s skill and art,

And the medicines she did impart,

I’ll tell you briefly, in twenty days

She aided him, in so many ways,

All could endure his company,

And his sad wound cured wholly

No longer did they keep away

From his presence, but sought to stay.

‘Tantris’ acts as tutor to Iseult the Fair

FROM this time on, the young princess

Was tutored by her learned guest,

And he gave all his attention,

Time, and effort, to her instruction,

Teaching the best of what he knew,

In book-learning, and music too;

I will not name all he did present

To her, each book or instrument,

One by one, so she might choose

Whate’er she liked of what was new,

But here is what Iseult achieved:

She took the best that she received

Through this, and most diligently

Improved her capability,

Assisted, indeed, by all that she

Had learned of such things formerly;

She owned already to refinements,

And to courtly accomplishments,

That called for use of voice and hand

And many such skills did she command.

Hers was the language of Dublin,

But she could speak French and Latin,

And played the viol, excellently,

In the Welsh manner, and if she

Set her fingers to the lyre, then

She played most deftly, and again,

From the harp drew plangent sound,

Tone, pitch, and modulation found,

And did so with dexterity.

Moreover she sang well and sweetly,

This girl blessed with skill and sense;

Her previous accomplishments

Much improved by her new tutor,

The minstrel, he who now taught her.

Among his various teachings he

Gave her a sense of the courtly

Art of pleasant manners, the art

With which a maiden should start

Her schooling, and her studying,

Since tis a fine and decent thing,

Worthy of both God and others.

Its dictates teach us the manner

Of pleasing others and God too,

Tis a nursemaid that is given to

All noble hearts so they may find

Life and nurture and, in the mind,

Lodge its precepts, for unless

Good manners aid their address

They’ll gain no profit or esteem.

Twas the chief pursuit, I’d deem,

Among the rest, of this princess;

As she sought ever to impress

Its principles upon her mind,

Her ways grew sweet and refined,

And full of charm, and courtesy.

Thus, the lovely girl, readily,

Acquired, in learning and bearing,

All that was noble and endearing,

Such that in less than half a year

All those who could see and hear

Her spoke of her true excellence.

The king, her father, took immense

Pleasure in all this, and the sight

Of her to her mother brought delight.

So, if it chanced that King Gurmun

Was joyful, or that knights had come

From other parts to join the court,

Then Iseult the Fair was sought,

And summoned before her father

To divert him, and those others,

With all her courtly attainments,

Adding, thus, noble entertainments,

To please her father and them all.

For whether they were rich or poor,

She pleased their eyes, and her arts

Delighted both their ears and hearts;

Thus, within them and without,

True pleasure was brought about.

Iseult the Fair, sweet, refined,

Sang, read, wrote for them, her mind

Joyful at their delight; whenever

They were pleased it gave her pleasure.

She would strike up an estampie,

Or play rare lays sung, exotically,

In the French style, of Saint-Denis,

And Sanze, for indeed she knew

Tune and words of more than a few.

She struck the strings of harp and lyre

As sweetly as one might desire,

With hands that were as white as snow;

And from her fingers notes did flow.

No woman played with such sweet ease

No, not in Lut, nor in Thamise,

As she, with grace and skill, did there,

Iseult the sweet, Iseult the Fair,

La dûze Iseult, la bêle;

And she would sing a pastourelle,

A rotruenge or a rondeau,

A chanson, or a refloit, so,

Or a folate and sang them well,

Well, and well, and all too well,

For many a heart, at her singing,

Thereby was filled with longing;

Her songs roused many a thought,

Many an idle dream they brought,

Wondrous things came to mind,

Which happens, as we ever find,

When such a wonder we behold,

Of grace and loveliness untold,

As in Iseult was manifest.

To whom this girl, by fortune blessed,

Should I compare if not the Sirens,

Who, with the lodestone, would commence

To draw ships near, of their singing?

For thus, to my way of thinking,

Iseult to her drew thoughts and hearts,

Deemed secure from all such arts,

Safe from the disquiet of longing.

And these two, ships and thoughts, straying

Are a comparison worth making;

Neither keep true course, oft lying

In uncertain havens, heaving

To and fro, pitching, tossing.

Just so does an aimless yearning,

Desire this and that way turning,

Wander like an anchorless boat,

Here and there. With every note,

This young and learned princess,

Iseult the wise, charmed her guests,

Drew forth feelings, with her art,

Those enshrined within the heart,

As the lodestone draws ships in,

That sound of the Sirens’ singing.

Many a heart her singing reached,

Both openly and covertly,

Through the ears and through the eyes.

Openly, there, sounds would rise,

The music of her sweet singing;

And the strings, softly sounding,

Played both here and elsewhere,

Echoed for all, and entered there

Through the ears’ realm, to dart

Straight to the depths of the heart.

But ever the song that covertly

Was sung, was her wondrous beauty,

That stole, with enraptured thought,

Wholly unbidden and unsought,

Through the windows of the eyes

Into the heart, stirred noble sighs,

Sweetly its enchantment sought,

Readily seized on every thought,

And bound it captive, fettering

The mind with desire and longing.

And thus, with Tristan’s tutoring,

Iseult the Fair, in many a thing,

Had much improved; she was charming

In her manner, and her bearing,

Played many a fine instrument,

Refined in each accomplishment,

And just as she could read and write,

So too she made songs to delight,

Creating both words and melody

Composing them most beautifully.

‘Tantris’ seeks leave to return home

TRISTAN now was quite recovered,

Such that his countenance and colour,

Which the treatment did thus restore,

Had returned to as they were before

His wound, yet he lived in fear

Lest he might be recognised here,

Among the people, or at court,

And was forever seeking in thought

Some courteous way of taking leave

So that his mind he might relieve,

Though the queen and her daughter

Were sure to resist his departure;

Nonetheless his life was surely

At risk, dogged by uncertainty,

And so he approached the queen

And spoke courteously as had been

His custom, and most eloquently,

Knelt before her, saying, humbly:

‘My lady, may God see you repaid

Eternally, for the comfort and aid,

And the favour you grace me with!

I pray that the Lord will ever give

You due reward for treating me

With such great kindness and mercy.

I’ll seek to deserve it, every way

I can, until my dying day,

And, poor man though I am, your name,

I’ll seek to ever advance that same.

Most generous queen, by your leave,

One further blessing I’d receive,

I would return to my own land,

For my affairs, you’ll understand,

Mean that I can no longer stay.’

The queen smiled, and then did say:

‘Flattery will not avail you so.

I shall not grant you leave to go.

You shall not leave within the year.’

‘Nay, noble queen, consider here

The nature of the marriage vow;

What two hearts’ love doth here allow;

For in that land I have a wife,

Who is dearer to me than life.

And I am sure she must believe

That I am dead. Should she receive

Another, for such is my fear,

My life, my joy would disappear,

For all my comfort would be gone,

And with it everything whereon

I set my hopes, and I should be

Doomed to a life of misery.’

‘Truly,’ the wise queen replied,

‘Such bonds are not to be denied.

For no such close a pair, I’d state,

Should any seek to separate.

May God grant his blessing then

To you and your good wife, again!

And though I would not see you go,

For God’s sake, I’ll suffer it so,

And will yet remain your friend.

Iseult, my daughter, and I extend

The gift to you for your journey,

For your sustenance, as may be,

Two marks in weight of fine red gold;

From Iseult then; to have and hold!’

The exile then his palms did place

Together, with courtesy and grace,

To give thanks, in spirit and body,

To the queen, and to the lady,

To the mother, and the daughter:

‘Thanks be to you, and all honour

In God’s name,’ Tristan now cried.

Since he would no more there abide,

He crossed the sea towards England;

Yet once he had approached the land,

Sailed southward towards Cornwall.

Tristan lands in Cornwall

WHEN his uncle, King Mark, and all

The folk around, heard that Tristan

In perfect health, was there at hand,

Then the people rejoiced, as one,

Through the whole of that kingdom.

The king, his friend, asked him how

He had fared on the waves, till now,

And Tristan then told his story

In all its details, as precisely

As he could. All showed their wonder

Yet amazement turned to laughter,

As their ears he did thus regale

With the substance of his tale,

How he had voyaged to Ireland,

And how, in that far distant land,

He had been healed, mercifully,

By one who was yet his enemy;

And of all that he had done there,

Among the Irish. All did declare,

They’d ne’er heard such a thing before.

When their marvelling at his cure,

And their laughter at his story,

Had abated, they were ready

To ask him of the people there,

And, most of all, Iseult the Fair.

‘Iseult,’ he said, ‘is so lovely,

All that was e’er said of beauty,

Beside her beauty, is as naught.

None shines so bright in any court.

Iseult is a girl so charming,

So entrancing, and so pleasing,

Both in person and in manner,

None was born, or will be ever,

So delightful, so enchanting.

Iseult the fair, brightly shining,

Bright as the gold of Araby!

No more now, that old tale for me,

Which praises that Helen born

Fair as a daughter of the dawn,

And how that one girl, in bloom,

All women’s beauty did assume.

The fault was all mine; forever,

Iseult has rid me of that error.

Never again shall I, for one,

Think that Mycenae bore the sun,

Perfect beauty shone not in Greece,

Here it shines, and without cease.

Let all men turn their thoughts and gaze

On Ireland, in these latter days,

Therein let their eyes find delight,

And on the new sun fix their sight,

That follows thus upon the dawn,

Fair Iseult, after Iseult, born,

That from Dublin to these parts,

Shines now into all men’s hearts!

This dazzling and enchanting light

Sheds everywhere its lustre bright.

All that folk may say in praise

Of woman’s naught before its rays.

Whoe’er sees Iseult, heart and soul

Refined, in him, as is true gold

By fire, delights in them and life.

Other women, maiden or wife,

Are not diminished in any way

By her, as many a man will say

Of his lady, for her great beauty

Serves to render others lovely,

For she adorns and crowns, we find,

Each, in the name of womankind.

Such that none need feel ashamed.’

When Tristan every joy had named

Roused in him by this fair lady,

She, of all Ireland the glory,

Those who listened to the story,

And were moved, and not by art,

But felt it there, along the heart,

Found that it sweetened all the mind,

As the blood is by May-dew, we find;

And all who heard it were inspired.

Tristan is the victim of envy

TRISTAN resumed his old life, fired

By new pleasures, as if enchanted.

A second life he’d been granted,

And he was as a man new-born.

He began to live; with that dawn

Found happiness and peace again,

And the king and his noblemen

Were happy to seek his pleasure,

Till an insidious rumour,

Born of accursed envy, stirred

Such as seldom goes unheard,

Altering opinions and manners,

Till men begrudged him honours,

And the distinction that he sought,

Once granted by people and court.

To his past actions they’d refer,

Claiming he was a sorcerer,

Disparaging him, recalling now

How he had slain Morolt, and how

He had then fared when in Ireland,

Supposedly a hostile land,

Saying it was worked by magic.

‘Look,’ they would murmur, ‘think on it,

And say now, how he could counter

The strength of Morolt, and after

Deceive Iseult, the all-knowing,

Trick a mortal foe into caring

For him so well that, in Ireland,

He was healed by her own hand?

List! Is it not a mighty wonder

How this most cunning deceiver

Draws a mist o’er people’s eyes,

And gains by every enterprise?

Then those men of Mark’s council,

Conspired to work Tristan evil,

Counselling Mark night and morn

To take a wife; let there be born

An heir, whether son or daughter.

Mark then gave them good answer:

‘The Lord indeed an heir did give;

By God’s grace, long may he live!

While Tristan, has health and life,

Know, I shall never take a wife;

Once and for all, there will be no

Queen or consort; it shall be so!’

This but increased their enmity,

And swelled the accursed envy

They all bore towards Tristan,

Visible in many a man

Who could hide it no longer.

Their hostility grew stronger,

Appearing in their attitude

And the language that they used,

So often that he felt his life

Was in danger, and this strife

Would, he feared, turn shortly

To cunning and conspiracy;

That indeed they’d seek further

So to bring about his murder.

He begged his uncle, good King Mark,

In God’s name, to attend, to hark

To his fears, and view the danger,

And then agree to whatever

The barons wished; let that be done:

He knew not when his death might come.

His uncle, wise and faithful too,

Said: ‘I wish for no heir but you,

Tristan, my nephew, never fear,

I shall ever protect you here.

Fear not for your body or life.

How then can such malice and strife

Harm you? A man who’s worthy

Is oft by malice beset, and envy.

And if he’s subject to men’s envy,

Indeed a man shows more worthy,

For envy and worth, together,

Are like a child and its mother;

Worth bears, and envy is its fruit.

Who meets not malice in pursuit

Of fortune and honour? That fate

Is of little worth, poor its state,

That never meets with enmity.

Struggle, that you might be free

Of folk’s spite for a single day,

Yet you’ll ne’er succeed, I say,

Of their spite you’ll ne’er be free.

But if quite free of such you’d be,

Then sing their tune, and be as they,

Their envy then will ebb away.

Tristan, whate’er others do

Remember what you are and who;

Aim always at nobility,

Look to where honour may be,

And what may be to your benefit,

And urge me not to counter it

With what works to your detriment.

Whate’er is their or your intent,

I’ll not attend to such a wish!’

‘Sire, if you will but grant me this,

I’ll go from court now; allow me;

I’m no match for their enmity.

If my downfall now is sought,

I must no longer live at court.

If tis amongst such malice here,

I must live, and live in fear,

Rather than realms in my hand,

I’d rather lack both realms and land.’

An embassy to Ireland is agreed

MARK, seeing he’d not be denied,

Interrupted, and then replied:

‘Nephew, as much as I would wish

To prove my love to you, in this,

And my good faith, you’ll not allow

My doing so; then, I avow,

Whate’er ensues I’ll take no blame,

And you shall have whate’er you name,

Tell me, what would you have me do?’

‘Summon your councillors to you,

Those who encourage you to wed,

And sound them out, as I have said,

And seek to know what they commend,

And find what it is they intend;

Then all may be settled readily.’

The councillors were summoned swiftly,

And they, aiming at Tristan’s death,

Agreed at once, with barely a breath,

That if a marriage they could contrive,

Iseult the Fair should be Mark’s wife,

For she, indeed, was more than fitting,

In her person, birth, and breeding.

This they thought was the very thing.

Then they had audience of the king.

One man, possessed of eloquence,

Delivered the meaning and sense

Of their counsel, on behalf of all,

Their will and purpose, in the hall:

‘Sire,’ he declared, ‘we understand,

That Iseult the Fair, of Ireland,

(For this is known in lands around,

And by all there on Irish ground)

Is a maiden on whom the power

Of womanly grace has sought to shower,

All the blessings there might be;

As you yourself have frequently

Heard of her, she is Fortune’s child,

Perfect in life, limb, undefiled.

If you obtain her as your wife,

And as our lady, no more in life,

No greater good, could come our way,

Where woman is involved, we say.’

The king answered: ‘My lord, explain,

Granted I wished her hand to gain,

How could that ever come to be?

Consider, now, the enmity

That has long existed between

The Irish and ourselves, I mean.

All of these people are our foes.

Gurmun himself, you must suppose,

Hates us all, and detests my name,

And rightly so; I too feel the same.

That any could ever bring about

Friendship between us: that I doubt.’

‘Sire’, they replied, ‘tis oft the case,

There is enmity twixt race and race.

But let the two sides take counsel

And make peace among the people,

Then we and they are reconciled,

Every man, woman, and child.

For enduring hostility

May oft yet end in amity;

And if you bear this in mind today,

You may yet live to see the day

When over Ireland you hold sway,

For only three stand in your way:

A king, a queen, Iseult the Fair,

Who, indeed, is their sole heir:

Ireland’s future’s with these three.’

‘King Mark replied: ‘Tristan has me

Thinking on her seriously,

For she has been much in my mind

Since he praised her, and thus I find,

Because of such thoughts, I too

Rejecting others, think as you.

I have dwelt so much upon her

That, if indeed I cannot wed her,

I will take no other to wife

I swear, by God, upon my life!’

Yet he swore the oath although

His true feelings were not so

Inclined, but as mere policy,

Never dreaming that it might be.

But his counsellors now replied:

‘If Tristan here doth take our side,

Who is acquainted with that court,

And you arrange that he do aught

That is required in this affair,

And deliver your proposal there,

Then all will readily be achieved,

The thing shall be as we conceived.

He is wise, prudent and fortunate

In all he seeks to undertake,

And he knows their language well.

He does all, as if by some spell.’

‘Tis evil counsel,’ King Mark cried,

‘Once, for you, he has all but died,

Fighting for you and for your heirs.

You are too intent on your affairs,

It seems, and would harm Tristan.

Do you seek again to kill the man?

No, you lords of my Cornwall,

You yourselves shall deal with all.

Go there yourselves, and be sure

To plot against Tristan no more!’

‘My lord,’ for thus spoke up Tristan,

‘Naught ill was said by any man,

It would be most fitting for me

To perform this, better twould be,

Indeed, than if another you chose;

And it is right that I do so.

I am the man, indeed, my lord;

None better can the realm afford.

Yet command them to sail with me,

Both there and back, to oversee

This thing, and maintain your honour,

Guarding your interest in the matter.’

‘You shall not lie in enemy hands

A second time; from that hostile land,

God Himself brought you back to us.’

‘Nay, Sire, it shall not transpire thus;

And whether these barons live or die,

I must share their destiny; tis I

Who’ll allow them thus to see,

That the fault will not lie with me,

If this land is left without an heir.

Tell them to make all ready, there.

I’ll steer the ship with my own hand,

And pilot it to that blessed land,

And so to Dublin once again,

And that sun that doth maintain

Happiness in many a heart.

Who knows but that we may depart

Again having won such beauty?

If she were yours, Iseult, the lovely

Girl, and yet we chanced to die,

Twere a small price to pay, say I.’

But when Mark’s counsellors perceived,

How Tristan’s speech was there received,

They were more downcast in spirit

That ever in their lives but there, it

Was settled, and must go forward.

Tristan prepares to return to Ireland

TRISTAN told the king’s steward

To find him twenty loyal knights,

From the household, fit to fight;

And sixty mercenaries he found,

Natives and foreigners, all sound;

And from the barons, twenty that day

He chose, to sail there without pay,

To make that company entire:

A hundred, levied or for hire.

This then was Tristan’s company

With which to cross the open sea.

He gathered also clothes and stores,

Assembling them all on shore,

Such that no ship that sailed before

Was ever so well provided for.

Now, one reads in the old ‘Tristan’,

That a swallow flew to Ireland,

From Cornwall, and a lock of hair

It plucked from the lady’s head there,

With which it then might build a nest,

(Though none knows, I would suggest,

How the swallow knew of the lady)

And brought it back across the sea,

So fair it led to Tristan’s journey;

Though, given that in Mark’s country

There was a plentiful supply

Of things to build a nest, then why

Would a swallow need to fly so far

To foreign lands? I swear there are

Few more fantastic tales; I fear

Tis nonsense they were talking here.

God knows, tis even more absurd

To say that Tristan, at Mark’s word,

But sailed the ocean at a venture,

While taking no account whatever

Of where he sailed to, or how far,

Yet following some fortunate star,

Nor knowing whom he was seeking.

What old score was he settling

With the book, who wrote that down,

And then spread the tale around?

If it were so then Mark, the king,

And all he sent about this thing,

The whole crowd of councillors,

And then the sad ambassadors

Who on a fool’s errand did go,

Would have been but fools also.

The envoys reach Ireland

NOW, Tristan and his company,

Sailed away upon their journey,

Though some, were most uneasy,

I mean the councillors, the twenty,

The barons of the Cornish nation,

Who, in their state of trepidation,

All fearing they would surely die,

Cursed the hour, and heaved a sigh,

The moment that their embassy

Sailed forth towards the enemy.

They saw no chance of salvation,

Discussing every sort of action,

But failing to reach agreement,

On aught to which all might consent.

Nor was that any great surprise;

Since any way to save their lives

Involved a choice between those two,

Boldness or cunning, and but few

Of them were eager to venture,

Or possessed of any measure

Of cleverness. And yet they said:

‘Tristan has thoughts in his head,

The man is clever, and versatile,

If God is kind to us the while,

And Tristan curbs his recklessness,

The which he shows to fine excess,

Then we may yet emerge alive.

Careless of himself, he’ll strive

Indifferent to our lives, or his,

Yet ever our best hopes in this

Our bound up with his success,

And his great resourcefulness

Is the key to our salvation.’

Once these doyens of their nation

Had reached the shores of Ireland

And at Wexford sought to land

Where they thought the king to be,

Then Tristan anchored out at sea,

Out of bowshot of the harbour.

His barons begged him, with ardour,

To tell them now, in God’s name,

How he would, for twas no game,

Win the lady, since all their lives

Rested on it, and twould be wise

If he spoke of his intention there.

‘Enough,’ cried Tristan, ‘now take care

That none of you meet their eyes.

Lie low within, we must disguise

Our purpose; members of the crew,

Rather than any one of you,

Will ask for news now, as they go

About the harbour, to and fro,

For none of you must yet be seen.

Be silent, and lie there between

Decks, I who speak their tongue

Will do the talking; soon will come,

Many a hostile questioner,

From the town, to the harbour.

I must tell smoother lies today

Than ever I have, so hide away.

If they see you, then understand

We’ll have a fight on our hands,

And all the country against us.

Tomorrow I go to speak for us;

I shall ride out early to chance

Our fortune and seek to advance

Our cause here, for well or ill.

While I’m away be hidden still,

Let Curvenal stand, at his ease,

By the dock, with any of these

Crewmen who speak the tongue,

And if I should be away too long,

If I do not, in four days, return,

Then wait no longer death to earn.

Save your lives, and take to sea.

For I’ll have lost my life indeed

Trying to arrange this affair;

And you may choose a wife back there

For your lord, from where’er you wish.

Thus do I think, and advise in this.’

Now the King of Ireland’s marshal,

One who had power over all

Dublin’s city and the harbour,

Came riding down in full armour,

With a great host in company,

Of citizens and emissaries,

With his orders from the court,

As this tale has already sought

To tell of, for, just as before,

All folk who landed on their shore,

He had his fixed orders to seize,

And discover if any of these

Was a native of Mark’s country,

To whom the Irish denied entry.

And thus this band of tormenters,

These bold and accursed killers,

Who many an innocent had slain,

To protect their master’s domain,

Came marching down to the harbour,

With their crossbows, in full armour,

Much like a band of brigands; so

Tristan donned a travelling cloak,

To disguise himself more readily,

And had a fine cup, marvellously

Wrought of pure gold, brought to him,

Done in the English style, and then

Took to his skiff with Curvenal,

And made towards the harbour wall.

He saluted the citizens and bowed

With all the grace that such allowed,

But, ignoring his every greeting,

Many a boat came out to meet him,

While the rest but shouted the more:

‘Put in to land now, seek the shore!’

Tristan promptly sought the land.

‘My noble lord,’ he did command,

Tell me why you come so armed,

As if indeed one might be harmed?

What mean you now by all this show?

What one should think I barely know.

Do me the honour, in God’s name,

Of telling me, what means this same?

If there is one here in this harbour

Who commands, then in all honour

Let him give fair hearing to me!’

‘That man is I, whom you now see,’

Said the Marshal, ‘and you will find

That we are armed in looks and mind,

To search out, and thus discover,

Why you are here and every other

Thing, down to the very last oar.’

‘Truly, my lord, I can assure

Your lordship I am at your pleasure.

If one might calm the crowd, at leisure,

And then allow me to have my say,

I would request that man, this day,

To hear me, in courteous manner,

As befits my country’s honour.’

With this he was granted a hearing.

‘My lord,’ said Tristan, with cunning,

‘Our trade, and standing, and country,

I now declare, to all and sundry.

We are men who live for profit,

Nor need we be ashamed of it.

We are merchants of Normandy

I and all of my company;

And there our wives and children are.

We travel from land to land, afar,

Trading our goods where’er we go,

Here and there, and to and fro,

And earn enough by that to live;

Whate’er gain our trade doth give.

A month ago we put out to sea,

I and two other ships, all three

Vessels, in convoy, bound for here,

And yet, but a week ago, I fear,

A storm-wind blew us far off course,

As gales will do, and so perforce

Dispersed our company of three,

And drove the others far from me.

I know not what’s become of them.

God preserve them, and so keep them!

During those eight days, the sea

Beat at our ship most cruelly,

And sent us on a wayward course.

Yesterday noon, the greater force

Of the gale being spent, I saw

The cliffs and headlands of this shore.

I hove to and anchored in the bay

Where we have lain until today.

Then this morning, when it was light,

I sailed for Wexford; yet my plight

Seems worse indeed than out at sea.

Though I came here seeking safety,

My life seems now to be in danger,

Though I sought welcome for the stranger,

For I have known this place before,

With other merchants found this shore,

And so hoped all the more to find

Safety, welcome; where men were kind.

Into a fresh storm now I sailed,

Yet God preserve me from the gale,

For if I find no safety here,

Among these folk, why then, tis clear,

That I must put to sea again,

There, where I may command the main

I’ll show any vessel fair fight,

Though in the way of taking flight.

Yet show me honour and courtesy,

And I shall be more than happy,

To gift you what my means allow.

If I may moor here, such I vow,

In return thus for some brief stay,

On the understanding, this day,

That you protect me, and my boat,

And all aboard, for still afloat

The other pair of ships may be,

And we may gather in company.

If you then would have me stay,

See to our safety; keep away

This fleet of skiffs whoe’er they be,

For if you do not, you shall see

I’ll return to my ship and crew

And think the less of all of you.’

The marshal, thereon, did command

The fleet of boats to head for land,

And then demanded of the stranger:

‘What will you give the king, if ever

I guarantee your life and vessel,

And grant you safe passage to travel,

To his court, and defend your stay?’

‘A mark of red gold, every day,

I’ll give, my lord, from our trade,

And this gold cup too, shall be made

Your very own, if I, thereby,

Upon your word may so rely.’

‘Indeed you may!’ on every hand,

The cry arose, ‘for in this land

He is the marshal.’ So the lord

Took that princely gift on board,

And bade Tristan seek the shore.

And then he ordered, furthermore,

The safety and security

Of Tristan and his company.

Rich and fine that tax and toll,

Rich and fine the king’s red gold,

And the goblet rich and fine,

For both now Tristan did resign,

And each of them magnificent,

So that he might thus gain consent

To both shelter and protection,

And save their lives by misdirection.

The encounter with the dragon

THUS Tristan has won safe passage,

And yet not e’en the wisest sage,

Knows what he may do with it.

You shall be told the whole of it,

And thus not tire of the story.

A serpent dwelt, in that country,

A vile monster, you understand,

That had brought upon the land

And its people such destruction,

That the king, driven to action,

Swore by his royal oath that he

Who rid them of their enemy,

Had claim to Iseult, if of worth,

A knight, that is, of noble birth.

This report, when widely known,

And the beauty of the girl alone,

Led to the deaths of many a man

Who came there to try his hand;

From far and wide they did wend,

Their way; but to meet their end.

Everywhere the tale was known,

To Tristan also it had flown;

For this alone he had chosen

To embark on the expedition,

And upon it, in the absence

Of aught else, he placed reliance.

Now is the hour, cometh the man!

And early the next morn, Tristan,

Armed himself as a man must do

Who knows that danger will ensue.

He took the strongest and the best

Lance aboard, in armour dressed,

Then mounted a sturdy war-horse,

Seized the lance, and set a course

Through the wastes and open land.

Twisting, turning, on every hand

To cross that tangled wilderness;

And as the morning did progress,

He sought the Vale of Anferginan,

Where lay the lair of the dragon,

As you may know from the story.

There, afar off, he saw a flurry

Of action, four men hard-riding

Across country, plainly fleeing

At a good pace; somewhat faster,

Than a pleasant morning canter!

One of the four that he had seen

He was the steward to the queen,

And sought the love of the princess,

Counter to all that she expressed.

Whene’er knights, seeking honour,

Rode forth to try deeds of valour,

The steward also would appear,

At any hour, be it there or here,

Solely that he too might be said

To venture forth where others led.

Though that was all he sought to do,

Since, if the dragon hove in view,

At the very first hint of dragon,

He turned swiftly, and was gone.

Now Tristan, he could clearly see

From the way these men did flee,

That the dragon was close nearby,

And so, holding his lance on high,

He rode that way and yet no more

Than a mile had he ridden before

He saw the dreadful sight ahead

Of the dragon, flame about its head,

Belching smoke from out its maw,

Twas the devil’s spawn: it saw

Man and horse there, and did advance.

Tristan, now lowering his lance,

Set his spurs to his faithful steed,

And galloped forward at full speed,

Thrusting the lance such that it tore

Through the throat beneath the jaw,

And sank deeper full near the heart

While he and his steed, for their part,

Now met the dragon with such force,

The horse fell dying, in mid-course,

And he was fortunate to survive.

But the dragon, still, as yet, alive,

Attacked the horse, scorching it,

Till through the lifeless corpse it bit,

And then that offspring of the devil,

Consumed the steed to the saddle.

Yet as the lance-wound pained it so,

It turned away, and did swiftly go

Towards the cliff there, while Tristan

Dogging its tracks, behind it ran.

The doomed creature forged ahead

Filling all the forest with dread

Of its vast roaring, while it burned

The trees, and through the thickets churned,

Till it was overcome with pain,

Whilst seeking for its lair again,

And wedged itself, for refuge, deep

Beneath a dark and rocky steep.

Tristan approached and drew his sword,

Thinking to find it wounded sore,

But no the danger now was greater.

And yet howe’er fierce the monster

Tristan attacked it, undeterred.

Despite the wound it had incurred,

It reduced him to such dire straights

He thought that he had met his fate.

But that he kept it at arm’s length,

It would have robbed him of the strength

To cut and thrust, and then indeed

Other fell foes it seemed to breed,

As smoke and steam, fire and teeth,

And claws that raked him from beneath,

So sharp, and closely ranked together,

They proved wicked as a razor.

Thus it chased him here and there,

Through trees and bushes, everywhere,

With many a tortuous twist and turn,

While he did some protection earn

From their scant cover, on the run,

Since the result of all he’d done,

Was that his shield was now torched,

Down near to his hand, and so scorched

To fragments, it was scant defence,

Against the flames, a poor pretence.

Yet none of this endured for long,

The murderous creature, strong

Though it was, found that strength

Ebbing fast, and the spear gone deep

Brought the monster down, to reap

The evil it sowed, in agony.

Tristan ran towards it swiftly,

Raising his sword; on his advance

Thrusting it, hard beside the lance,

Into the heart, hilt-deep; hurt sore,

The vile creature sent out a roar,

So frightful, and so appalling,

The sky seemed as it were falling,

While earth shook; the mortal cry

Filling the land about, thereby,

With that shriek, stunning Tristan.

But seeing it fallen, by his hand,

And lying there in death, he tore

Its jaws apart, and from the maw

Cut out the tongue with his sword

As far as his reach would afford,

Placing it neath his hauberk there,

To bring an end to that affair.

He withdrew to the wilderness,

Seeking there for a place to rest,

And recover, while it was light,

Then return to his friends at night.

But, suffering still from the heat

Of the dragon, and near defeat,

He knew so wearisome a feeling,

He thought his own death nearing.

Yet, looking all around, he saw

A gleam of water that did pour

From a cliff, both tall and sheer,

Into a long and narrow mere.

In he plunged, armour and all,

Upon his back there he did fall,

With naught but his face in sight.

There he lay, a day and a night,

For the dragon’s tongue he bore

Had stolen his strength and more,

Senseless he lay: the fumes alone

Rendered him the colour of stone.

And there indeed must Tristan lie,

Till the princess shall him espy.

The steward seeks out the dead dragon

NOW the steward, as I said above,

Wished to win the princess’ love,

And be her knight, the lovely maid.

Hearing the death-roar, unafraid,

Now, of the beast whose mortal cry

Filled the woods and wastes nearby,

Rehearsing its death in his mind,

He fresh assurance thus did find,

Thinking: ‘It surely must be dead

Or, if not, so near to death instead,

That I can readily follow through

With a little cunning.’ So from view

He stole, left his three companions,

Rode down a slope, in the direction

Of that cry, spurring on his horse

And so arriving, in due course,

At the remains of Tristan’s mount,

Where he halted to take account,

Anxiously swept his gaze around

Then slowly covering the ground,

He weighed the matter in his mind,

Fearful of what else he might find.

Nonetheless, twas not too long

Before he stirred, and then rode on,

In a somewhat desultory manner,

Nervously now, following after

The trail of burnt leaves and grass,

Where the evil creature had passed;

And suddenly, but half-aware,

He came upon the dragon there.

The steward was shocked indeed,

Astonished by his daring deed

At having approached so near,

Nearly losing his seat, that here

He wheeled his mount so swiftly

Horse and man collapsed entirely.

Once his scattered wits he’d found,

(Gathering himself from the ground)

It was more than he could do

To remount his war-horse too,

Given his state of abject fear;

So the sad steward disappeared,

Leaving his mount there, and fled.

Yet since naught behind him sped,

He halted, and returned once more,

Picked his lance up from the floor,

Grasped his mount by the bridle,

And scrambled into the saddle,

From a tree-trunk that lay nearby,

Settling again, with a deep sigh.

Then he galloped some way away,

And looked at where the dragon lay

To judge if it was dead and gone,

Or if some life still lingered on.

The steward claims the victory

ONCE he determined it was dead:

‘By God’s good will, now,’ he said,

‘My fortune’s made, at a venture;

For here’s a veritable treasure:

Fortune indeed has brought me here.’

And with this he lowered his spear,

Spoke to his mount, and gave it rein,

Then put it to the gallop again,

Spurring its flanks on either side,

And as he spurred it on, he cried:

‘Schevelier damoisêle,

Ma blunde Iseult, ma bêle!

Iseult the blonde, Iseult the fair,

My lady’s knight am I, beware!’

He gave the dragon a thrust, aft,

So forceful that the ashen shaft

Slid backwards through his grip.

Yet that he fought no more with it

Was due to a fresh thought, you see:

‘If its destroyer, whoe’er he be,

Is still alive, then all my scheme

Must prove as idle as a dream.’

So the steward rode here and there,

Searching the ground everywhere,

In hopes of discovering the man,

(For this was now his secret plan)

So badly wounded, and so weary,

That he might overcome him; clearly

He could engage him in a fight,

Kill him, and lodge him out of sight.

But searching, and yet finding naught,

‘Enough of this, my lord!’ he thought,

‘Whether he’s dead or still alive,

My find it is, and I shall thrive.

For I have kin, a host of friends,

On whom, in this, I may depend,

So notable, such men of worth,

That never a man on this earth

Could dispute the matter with me.’

He spurred back now to his enemy,

Dismounted, and hacked away,

As if he had the thing at bay,

Stabbing and thrusting with his blade,

Here and there until he had made

Sufficient holes, peck after peck.

And then he started on the neck,

And would have liked to sever it,

But found its hide so tough and thick,

That of the task he soon was weary.

He broke his lance across a tree,

And forced the half with its tip,

Into the dragon’s throat, as if

It was the outcome of a blow.

‘How he slew the dragon’

The Story of Tristan and Iseult, Vol I - Jessie L Weston and Caroline Watts (p75, 1907)

Internet Archive Book Images

Then he mounted, and off did go,

To Wexford on his Spanish steed,

Where he ordered men with speed

To take a cart, and fetch the head,

While he the wondrous news did spread,

Of his victorious encounter,

How he’d been in dreadful danger,

And yet, despite all he had borne,

Had slain the dragon that fair morn.

‘Yes, yes, my lords, let everyone

Hear all the wonders I have done,

And see what a courageous man

May venture yet for a fair woman,

A man who’s steadfast to the end.

I can scarce believe, my friends,

That I’ve returned safe and alive,

From what few heroes could survive.

I’d not have done so, were I weak

And tender; of that man I speak

I know not whom, some knight errant,

Who’d ventured first on this errand,

And came upon it before me,

And yet had not the victory,

For then, indeed, he met his death,

Both man and steed lost in a breath,

Since God had there forsaken him;

And they are dead the pair of them.

Half the horse remains in place,

That jaws and fire did not deface;

But why should I prolong the tale,

Since in the end I did prevail,

Yet suffered more for this dragon

Than man e’er suffered for a woman.’

He gathered all his friends together,

And they returned to see the creature.

He showed the wonder, then he asked

That all bear witness, if so tasked,

To the gospel truth of all he’d said,

And then they carted off the head.

He sought his kin, and called his men,

And then he sought the king again,

There to remind him of his oath;

And thus a day was set when both

He and all the lords might meet

At Wexford, and there complete

Discussion of the matter; and so

That the thing might duly follow,

The whole council was summoned,

By which I mean here, every baron;

And they made ready as required

To gather there as the king desired.

End of Part V of Gottfried’s Tristan