Rainer Maria Rilke

Letters to a Young Poet

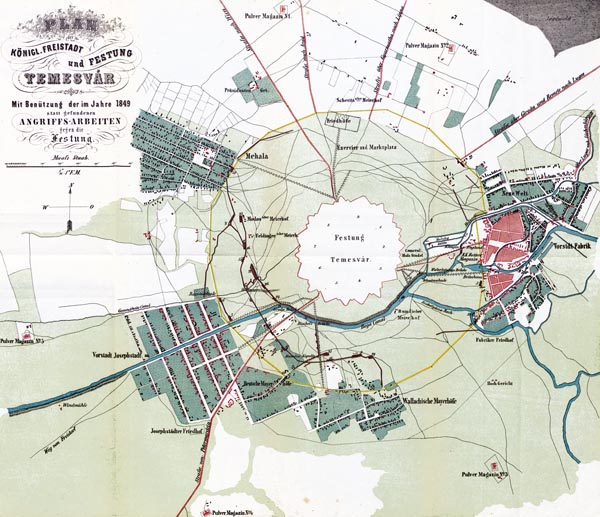

‘Monograph of the Royal Free City of Temesvár’ - Preyer, Johann N (1853), The British Library

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Introduction.

- Letter I: Paris, 17th February 1903.

- Letter II: Viareggio, near Pisa (Italy), April 5th 1903.

- Letter III: Viareggio, near Pisa (Italy), April 23rd 1903.

- Letter IV: Worpswede near Bremen, July 16th 1903.

- Letter V: Rome, October 29th, 1903.

- Letter VI: Rome, December 23rd, 1903.

- Letter VII: Rome, May 14th, 1904.

- Letter VIII: Borgeby Gård, Flädie, Sweden, August 12th 1904.

- Letter IX: Furuborg, Jonsered in Sweden, November 4th 1904.

- Letter X: Paris, Boxing Day, 1908.

Introduction

Rilke’s letters to a young poet Franz Xaver Kappus, written between 1902 and 1908, were first published by Kappus in 1929. A cadet at the Austrian military academy the lower school of which Rilke had attended in the 1890’s, the young man went on to pursue an extended military career, as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army, afterwards working as a journalist, editor, writer, and politician. These letters, dating from the early period of Rilke’s own poetic development, offered advice and insight to the younger man, while also revealing Rilke’s ideas and attitudes regarding creative poetic effort and life itself. The two men never met in person, but, thanks to Kappus, these letters to him were preserved, and help to illuminate Rilke’s own achievements in the art, as well as providing a source of inspiration and guidance to poets in general.

Letter I: Paris, 17th February 1903

Dear Sir,

I received your letter just a few days ago. I wish to thank you for the great and precious trust you place in me. I am unable to do more. I cannot enter deeply into the nature of your verse, since any attempt at criticism is alien to me. Nothing touches on a work of art as little as words of criticism: from them arise more or less unfortunate misunderstandings. Things are not as comprehensible and sayable as we are commonly led to believe; most of our experiences are unsayable; occurring in a space that no word has ever entered, while most unsayable of all are works of art, mysterious existents whose life endures alongside our own transient life.

With these words as introduction, I must simply tell you that your verses lack a style of their own yet, quietly and covertly, they approach the personal. I feel this most clearly in the last poem ‘My Soul’. Something of its own wishes to express wisdom and word. And in the beautiful poem ‘To Leopardi’, a sort of kinship with that great, solitary spirit emerges. Nonetheless, the poems are not as yet anything in themselves, not yet independent creations, not even the last, nor the one concerning Leopardi. Your kind letter, accompanying them, succeeded in clarifying the many shortcomings which I felt on reading them, without being able to name them.

You ask if your verses are good. You ask me this, and have asked others before me. You send them to journals. You compare them with other poems, and are anxious when certain editors reject your efforts. Now (since you would have me advise you) I beg you to forego all this. You are looking outwards, and that above all things you should avoid right now. No one can advise or help you, no one. There is but the one remedy. Go within. Find the reason that you write; see if its roots lie deep in your heart, confess to yourself you would die if you could not write. This above all, ask yourself in the silence of night: must I write? Dig deep for an answer. And if it should be in the affirmative, if you can meet this solemn question with a strong and simple I must, then construct your life in accord with that need; your life in its most trivial, its least important hour, must be sign and witness to this urge.

Then draw closer to Nature. Then, seek to say, as if you were the very first to do so, what you see, experience, love, and lose. Don’t write love poems; avoid those forms that are too common and ordinary; they are the hardest, since it takes great and mature strength to create something of one’s own where a fine and brilliant tradition already exists. Deliver yourself from these general themes and choose those that your own life offers you, day by day; describe your sorrows and desires, your passing thoughts and belief in some kind of beauty – describe all these, with quiet, humble, heartfelt sincerity, and use the things around you to express yourself, the images from your dreams, and the objects of your memory. If your everyday life seems impoverished, don’t blame it; blame yourself, say to yourself that you are not enough of a poet to invoke its riches; since for the creative there is no such thing as poverty, no poor or indifferent place. And even if you found yourself in prison, one whose walls prevented all sound reaching you from the outside world – would you not still possess your childhood, that precious wealth, that store-house of memories? Turn your attention there. Try to raise the sunken sensations of that gigantic past; your personality will grow stronger, your solitude will expand and become a twilit dwelling where the noise others make will pass by, far away. And if from this turning within, from this immersion in your own world, poems arise, you will not even think to ask if your verses are good. You will not even seek to interest the journals in your work: since you will see them as your own dear natural possession, a part of your life, a voice therein. A work of art is good if it is born of necessity. It can only be judged by such an origin: and in no other way. That is why, my dear sir, I have only this advice: go into yourself and view the depths from which your life springs; there at the source you will find the answer to the question of whether you must create. Accept that answer as it is given, without seeking to interpret it. Perhaps you will find your calling as an artist. Take that fate upon yourself, then, and bear its burden and its greatness, without ever asking what reward might come from outside. For the creator must be a world unto themself, and find everything there within the self, and in that Nature to which they are connected.

But it may be that even after this descent into yourself and your solitude you will have to forgo becoming a poet (it is enough, as I said, to feel one could live without writing to make one forbid oneself to try) Nonetheless, the self-contemplation I asked of you would not prove in vain. Thereafter your life will still find its own path, and that it may be fine, and broad, and full of richness, I wish for you more than I can say.

What else can I tell you? Everything seems to me to require its own proper emphasis; so finally, I would simply advise you to keep on growing throughout your development, quietly and earnestly. You cannot disturb that development more violently than by looking outside and expecting an answer from outside to those questions that only your innermost feelings might answer perhaps, in your quietest hour.

It was a pleasure to meet with the name of Professor Horacek in your letter; I have a great admiration for that gracious and learned man, and a gratitude that has endured the years. Please tell him of my feelings; it is very kind of him to still think of me, and I appreciate it greatly.

With that I return to you the poems you have kindly entrusted to me. And I thank you once more for the magnitude and warmth of your trust in me, of which I have sought to render myself somewhat worthier than I, through an honest answer giving of the best of my wisdom, can, as a mere stranger, truly be.

Yours most sincerely,

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter II: Viareggio, near Pisa (Italy), April 5th 1903

You must forgive me, my dear sir, for only now recalling your letter of February 24th, yet with thanks. I have been in a state of suffering all this while; not ill exactly, but oppressed by a flu-like languor that rendered me incapable of anything. And finally, since there was no improvement, I drove to this southern shore whose beneficence has helped me once before. Yet I am still unwell. I find it hard to write, and so you must accept these few lines in lieu of more.

Of course, you must know that every letter of yours pleases me, and be indulgent towards my reply, which must often leave you empty-handed, since fundamentally, and particularly in the deepest and most serious matters, we are unspeakably alone, and in order to advise or even help another much must happen, must go right, a whole constellation of things must arise, for it to succeed.

Today I wish to say two things to you. Irony: don’t let it dominate you, especially in your unproductive moments. In creative times try to use it as one more way of grasping hold of life. Used purely it too is pure, and nothing to be ashamed of; and if you feel yourself becoming too familiar with it, if you fear a growing intimacy with it, then turn to large and serious aims before which it becomes small and helpless. Seek the depth in things: irony never reaches that far – and if you reach the borders of greatness, you will simultaneously test whether this way of apprehending the world arises from your inner need, since under the influence of the serious it will either drop from you (if it is merely accidental) or else (if it is truly innate and belongs to you) it will grow stronger and become a serious tool, and take its place among the instruments of your art.

And the second thing I want to speak of today is this. Of all my library, only a few books are indispensable to me, and two are always with me, wherever I am. They are beside me here; the Bible, and the books of the great Danish poet Jens Peter Jacobsen. I wonder if you know his works. You can easily obtain them, since some have appeared in the Reclam Universal Library in a very fine translation. Get the little volume of ‘Six Novellas’ by J. P. Jacobsen and his novel ‘Niels Lyhne’ and begin with the first novella of the former, which is entitled ‘Mogens’. A whole world will embrace you, the happiness, the riches, the incomprehensible greatness of a world. Live for a while in these books. Learn from them what you think worth learning, but, above all, love them. This love will be repaid a thousand thousandfold and, whatever your life may become, I am certain it will weave through the fabric of that becoming as one of the most vital threads among all the threads of your experiences, all the disappointments and joys.

If I were to say from whom I have learned something of the essence of creativity, of its depths and its eternal nature, there are but two names I can mention: Jacobsen, the great, great poet, and August Rodin, a sculptor who has no equal among living artists –

And all success upon your way!

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter III: Viareggio, near Pisa (Italy), April 23rd 1903

You granted me much pleasure, my dear Sir, with your Easter letter; since it speaks many good things of you, and the manner in which you talk of Jacobsen’s great and beloved art showed me that I was not wrong to direct your life and its many questions to his abundance. Now ‘Niels Lyhne’ will open a book of depth and splendour to you; the more one reads it the more everything seems to be contained within, from life’s most subtle fragrance to the vast, full taste of its heaviest fruit. There is nothing there that has not been comprehended, grasped, experienced, and recognised in memory’s reverberating tremor; no experience has proved too trivial, and the slightest event unfolds as if fated, and fate itself is like a marvellous broad web in which every thread is woven by an infinitely tender hand and laid beside another, and is held and supported by a hundred others. You will experience the great happiness of reading this book for the first time, and will enjoy a host of surprises as if in a new dream. But I can tell you that, even afterwards, one goes through these volumes again and again with the same astonishment, and that they lose none of their marvellous power, and fail of none of the overwhelming enchantment they possessed on first reading.

One simply comes to enjoy them more and more, with more and more gratitude, and become somehow better and more accomplished in seeing, believing more deeply in life, and happier and greater in living.

And then you must read the wonderful tale of Marie Grubbe’s fate and yearning, and Jacobsen’s letters and journals, and fragments, and finally his poems which (even if they are only moderately well translated) are alive with infinite sounds. (I would advise you, if you can, to buy the fine edition of Jacobsen’s works which contains all of these, published in three volumes, and printed with skill by Eugene Diederichs in Leipzig, which costs I believe only five or six marks per volume.)

You are of course quite right, incontestably right, in your opinion of ‘Here should be roses…’ (that work of such incomparable form and delicacy) as against the person who wrote the introduction. And let me make this request at once: read as little aesthetic criticism as possible; which comprises either partisan views, petrified and meaningless, hardened and without life, or clever word games in which today this view wins and tomorrow its opposite. Works of art are infinitely lonely, and no approach to them is as useless as criticism. Only love can grasp them, and hold them, and so be fair to them. Always trust yourself and your feelings, as regards every such introduction, argument, or discussion; if you prove to be wrong, the natural growth of your inner life will gradually, in time, lead you to other insights. Leave judgement to your own quiet, undisturbed development, which like all progress must come from deep within and cannot be forced or hastened. It is all gestation and birth. Let every impression, every germ of feeling, be perfected in oneself, in darkness, in the unsayable, the unconscious, unattainable by one’s understanding, and wait with deep humility and patience for the hour in which a new clarity is born: that alone is to live the life of an artist: in understanding as in creating. In this there is no measure of time, a year, ten years are nothing. Being an artist means not numbering and counting, but ripening like a tree which does not force its sap, but stands securely through the storms of spring, unafraid that summer might fail to follow. It will come. But it comes only to those who are patient, who exist as if eternity stretched before them, so unconcernedly peaceful and immense. I learn it daily, learn it with suffering to which I am grateful: Patience is all!

Richard Dehmel: my experience with his books (and, incidentally, with the man, whom I know slightly) is such that whenever I come upon one of his beautiful pages, I am always afraid that the next will destroy everything once more and change the admirable into the unworthy. You have characterised him well enough with your phrase: ‘living and writing with ardour’. And, in truth, artistic experience is so unbelievably close to the sexual, its pain and its pleasure, that the two appear to be really just different forms of one and the same yearning and bliss. And if instead of ‘with ardour’ one were permitted to say ‘sexually’, sexually in the deep, broad, pure sense of the word, free of any trace of religious sinfulness, then his art would be truly great and infinitely important. His poetic strength is great and as powerful as primal instinct; it has its own relentless rhythms within, and explodes from him like a volcano.

But it seems this power is not always wholly sincere and free of posing (yet that is one of the hardest things for the creative artist: who must always remain unconscious and unaware of his finest virtues if he does not wish to rob them of their impartiality and their untouched innocence!) And then, when sweeping through his being it arrives at the sexual, it finds someone not quite as pure as it would have him be. Instead of a wholly mature and pure world of sexuality, it finds one that is insufficiently human, merely male, full of passion, intoxication, restlessness, and laden with the ancient prejudices and pridefulness with which the male has always distorted and burdened love. Because he loves only as a man, not as a person, there is something narrow, seemingly savage, hateful, temporal not eternal, that diminishes his art and renders it dubious and ambiguous. It is not immaculate but marked by time and passion, and little of it will survive or endure (though most art is like that!). Nonetheless, one can enjoy what is great in it, just don’t get lost in it, and become a fellow-traveller in Dehmel’s world, which is so infinitely fearful, filled with confusion and adultery, and far from one’s true destiny which causes one more suffering than those temporal afflictions, yet also grants the opportunity for greatness, and courage to face eternity.

As for my own books, I would like to send you everything that might please you. But I am quite impoverished, and once my books are published, they are no longer mine. I cannot afford them myself, or, as I often wish to, give them to those who would like them.

So, I have written, on another sheet of paper, the titles (and publishers) of my most recent books (the newest; as in total I have likely published twelve or thirteen) and I must leave it to you, my dear sir, to order one or other from time to time. I would like you to have my work beside you.

With best wishes,

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter IV: Worpswede near Bremen, July 16th 1903

I left Paris about ten days ago, tired and unwell, and travelled to this vast northern plain, whose silence, immensity and open skies should make me well again. But I arrived in a prolonged bout of rain, which today has begun to clear a little from the troubled landscape: and I am employing this first glimpse of brightness in greeting you, my dear sir.

My most dear Herr Kappus: I have left one of your letters unanswered for a long time; not because I had forgotten it – on the contrary: it is of the kind that, on finding it among other letters, one reads again, and I recognised your presence there as if you were close by. It is your letter of the 2nd of May which I am sure you must recall. As I read it now, in the stillness of this vast landscape, I am moved even more by your beautiful anxiety about life than I was in Paris, where all sounds different, and fades into an excessive noise that makes things tremble. Here, where the immense countryside surrounds me, over which blows a wind from the sea, I feel that no one anywhere can reply to your questions and feelings which, in their depth, possess a life of their own; for even the finest words fail if they seek to articulate that which is quietest, and well-nigh unsayable. Yet I still believe that you need not remain without an answer if you trust to things like those which my eyes now rest upon. If you trust to Nature, to what is simple within Nature, the small things that scarcely anyone sees, which can so swiftly become vast and immeasurable; if you possess love for what is humble and, simply as one who serves, seek to gain the trust of what seems impoverished: then all will become easier for you, more consistent, and more filled for you with reconciliation, not in the conscious mind perhaps that remains amazed, but in your innermost awareness, awake and knowing.

You are so young, so before all beginning, and I would beg you, dear sir, as best I can to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books penned in a language most foreign to you. Don’t search for answers now that cannot be given because you could not live them. And it is about living it all. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, at some distant point, without realising it, you will gradually come to live yourself into the answer. Perhaps you have the power to educate and create, within a particularly pure and blessed way of life; train yourself to do so – but accept with true confidence whatever comes, and as long as it comes of your own freewill, from some labour within yourself, take it upon yourself, and hate nothing. Sexuality is difficult; yes. But what we are asked to perform is difficult; almost everything serious is difficult, and everything is serious. If you but recognise this, and reach a point where you achieve your own relationship to your sexuality, by yourself, out of your own experience, childhood, strength (uninfluenced by convention, childhood, custom) then you will no longer have to fear losing yourself or becoming unworthy of your finest possession.

Physical enjoyment is a sensual experience, no different than purely gazing, or the pure feeling with which a beautiful fruit fills the tongue; it is a great, an infinite experience that is granted us, to know the world, the whole richness and splendour of knowledge. And it is not our acceptance of it that is wrong; what is wrong is that almost all of us misuse and squander the experience, and employ it as a stimulant to the tired places of their lives, and as a diversion, rather than a gathering of themselves to a climax. After all, people have turned eating into something other: on the one hand need, on the other an abundance that has dimmed the sharpness of that need, while all the deep and simple necessities whereby life is renewed have likewise been rendered dim. Yet individuals can, of themselves, clarify, and live clearly (if not the dependent individual, then the solitary one at least). The individual can take pains to remember that all beauty in creatures and plants is a silent, enduring form of love and yearning, and can see the creature as he sees the plant, patiently and willingly, uniting and multiplying and growing, not out of physical pleasure, not out of physical pain, but bowing to necessities greater than pleasure or pain, and more powerful than willing or resisting. Oh, if only human beings could accept this mystery, with which the world is filled even it its smallest things, more humbly and suffer it more seriously, and endure, and feel how dreadfully heavy it is, instead of taking it lightly. If only they would show more reverence towards their fertility, which is essentially one whether mental or physical; since mental creation also arises from the physical, is of the one nature with it, and only like a quieter, more pleasing, eternal repetition of physical passion. ‘The thought of creating, engendering forming’ is nothing without its vast, endless confirmation and realisation in the world, nothing without the thousandfold endorsement of things and creatures – and it for this reason alone that our enjoyment is so indescribably rich and beautiful, because it is full of inherited memories from the engendering and birth of countless millions. In creative thought, a thousand forgotten nights of love come to life, filling it with depth and splendour. And those who come together in the night, entwined in cradling delight, perform a solemn task, and gather sweetness, depth and power for the song of some future poet, who will rise and utter unspeakable bliss. And they summon the future; and even if they err and embrace each other blindly, that future will come, a new being arrives, and on the basis of the seemingly chance encounter that has occurred that law awakens by which a resilient powerful seed forces its way through the egg’s membrane that opens to meet it. Don’t be deceived by surface; in the depths all becomes law. Yet those who live the mystery falsely and wrongly (and there are very many) lose it only for themselves, and still pass it on unknowingly like a sealed letter. And don’t be confused by the multitude of names and the complexity of forms. Perhaps above all a great maternal yearning exists in common. The beauty of the virgin, a being who (as you so beautifully put it) ‘has not yet achieved anything’ lies in a motherhood that feels a presentiment and prepares itself, is fearful and yearns. And a mother’s beauty is in serving motherhood, and in the aged woman there is a vast remembering. And there is also a maternal instinct in the male, it seems to me, physical and mental; his creativity is also a sort of giving birth, and it is in giving birth that he creates from his innermost fullness. And perhaps the sexes are more closely related than people think, and perhaps the world’s great renewal will consist in the fact that man and woman, free of delusion and aversion, will seek each other not as opposites but as brother and sister, as neighbours, as human beings, in order to bear, simply, seriously, patiently, the weight of sexuality that has been laid upon them. But what may one day be possible for many, the solitary can prepare for, and build with hands less prone to error.

So, my dear sir, love solitude, and endure the pain it brings with lovely sounds of lament. For those close to you seem far away, you write, and that shows the distance is growing around you. And if you seem far distant, your expanse of self is already among the stars and immense; rejoice in your growth, wherein you can take none with you, and be kind to those who remain behind, and be secure and calm before them, don’t torment them with your doubts or frighten them with your joy and confidence, which they could not comprehend. Seek some plain and simple common ground, that need not necessarily change, if you yourself change and change again; love the life in them, that other life, and be gentle towards those who grow old fearing the loneliness in which you trust. Avoid adding to the material drama that is ever stretched taut between parents and children; it saps the children’s strength and wastes the love of their elders, a love that labours to add warmth, even where it fails to understand. Don’t look for advice from them, and don’t expect understanding; believe in the love that is stored up for you like an inheritance, and trust that within it lies a strength and a blessing that you do not have to depart from however far you go!

It is good that you are entering a profession that will render you independent, that leaves you completely on your own in every sense. Wait patiently to see whether your inner life feels constrained by the nature of this profession. I think it very difficult and demanding, since it is burdened by weighty conventions leaving almost no room for a personal interpretation of its duties. But your solitude will be a haven and home for you, even amidst the most alien circumstances, and you will find your path on which to emerge. All my good wishes are ready to accompany you, and my trust lies in you.

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter V: Rome, October 29th, 1903

Dear Sir,

I received your letter of August 29 in Florence, and only now – two months later – I tell you of it. Please forgive my delay, but I dislike writing letters while travelling, because I, more than most, need those essential tools for writing: a modicum of silence, and solitude, and not too unfamiliar an hour. We arrived in Rome about six weeks ago, at a time when it was still the Rome of emptiness, heat and fever, and this circumstance, along with other practical difficulties in finding a place to stay, contributed to the endless restlessness surrounding us, and unfamiliarity laid upon us its weight of homelessness.

In addition, bear in mind that Rome (if as yet you know it not) seems overwhelmingly sad at first: due to the lifeless, gloomy, museum-like atmosphere it exhales; the numerous pasts that have been excavated and painstakingly maintained (upon which a tiny Present subsists); the endless overvaluing of all these decayed and disfigured things, presented by scholars and philologists and imitated by the customary travellers to Italy, things which are no more than chance remnants of another age, and a life that is not and should not be ours. At last, after weeks of daily resistance, one recovers oneself, though still somewhat confused, and says to oneself: ‘No, there is no more beauty here than elsewhere, and all these objects admired by the generations, restored and repaired by the hands of workmen, mean nothing, are nothing, and possess no heart and no value – yet there is much that is beautiful here, since there is much that is beautiful everywhere.’ Ever-living water flows along the ancient aqueducts into this great city, and dances over white stone bowls in the many squares, and spreads through broad, spacious basins, murmuring by day, and lifting its murmurs to the night, which here is vast, and starry and full of gentle breezes. And there are gardens here, unforgettable avenues, staircases devised by Michelangelo, staircases made on the pattern of downward-sliding water – broadly sloping, giving birth to step after step, as if wave upon wave. Through such impressions one gathers oneself together, regains oneself from the demanding multiplicity that speaks and chatters there (how talkative it is!) and learns, slowly, to recognise a very few things in which something eternal endures that one can love, and something solitary in which one can gently take part.

As yet I am living in the city, on the Capital, not far from the finest surviving equestrian statue in ancient Roman art – that of Marcus Aurelius; but in a few weeks I shall move to a quiet, simple room, an old summerhouse lost in the depths of a large park, hidden from the city, its noise and incident. I shall live there all winter and enjoy great silence from which I expect the gift of good and productive hours.

From there, where I shall feel more at home, I will write you a longer letter in answer to yours. Today, I shall simply tell you (and perhaps I was wrong not to have done so earlier) that the book announced in your letter (that is to contain your work) has not arrived. Was it returned to you, perhaps, from Worpswede? (Since they will not forward parcels to another country). That is the most likely outcome, which I would be pleased to have confirmed. Hopefully there is no question of it being lost – which, unfortunately, is not at all unlikely given the Italian postal service.

I would have been glad to receive the book (as I would anything that indicates yourself); and I shall always read any poems that have arisen in the meantime (if you will entrust them to me) and re-read and experience them, as well and warmly as I can. With greetings and good wishes,

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter VI: Rome, December 23rd, 1903

My Dear Kappus,

You should not lack a greeting from me at Christmas, when you, in the midst of the festive period, bear a solitude heavier than usual. But in noticing how vast it is you should be happy; for what (you should ask yourself) would a solitude be that was not vast; there is only one solitude, great and not easy to bear, and everyone has hours when they would rather exchange it for commonplace speech, however trivial and banal, for the slightest sign of acceptance from the next comer, even the least worthy…But perhaps these are the very hours when solitude matures; for its maturation is as painful as that of growing youths, and as sad as the start of spring. But don’t let it drive you mad. What is required is just this: solitude, vast inner solitude. To enter into yourself and meet no one for hours – that is what you need to achieve. To be solitary, as solitary as one was as a child, when adults walked around you, involved with matters that seemed large and important, because they seemed so preoccupied, and you understood so little of what they were about.

And when one day you realise their activities are wretched, their vocations petrified and no longer connected to life, why not continue to regard it all as a child would, from the depths of your own world, the vastness of your own solitude, which is itself work, status, and profession, as something alien? Why wish to exchange a child’s wise incomprehension for defensiveness and contempt, since incomprehension is solitude, while defensiveness and contempt participate in that from which you would separate yourself, in this way.

Think, dear sir, of the world you bear within you, and call such thinking whatever you wish; whether remembering your own childhood, or yearning for your own future – only attend to what rises in you and set it above all you take note of around you. Your innermost experience is worthy of being wholly loved, you must somehow work with it, and not waste too much time and courage justifying your attitude towards others. Who says you must even have one?

I know your profession is hard and conflicts with your being, and I foresaw your case, and was certain this would happen. Now it has happened, there is nothing I can say to reassure you, but simply suggest that all professions are like this, full of demands, and enmity against the individual, saturated, as it were, with the hatred of those who are dumb and sullen, locked in their solemn duties. The society in which you are forced to live is no more burdened with convention, prejudice and error than any other, and if there are societies that display greater freedom, none are as deep and spacious inwardly, as related to the great things that render life real. Only the solitary individual is bound by the deepest laws, as is all around him, and when someone walks out into the dawn, or looks out into the evening full of event, and feels what is happening there, all rank and position falls from him, as from the dead, though he stands amidst the noise of Life. What you, dear Kappus, must now experience as an officer, you would have experienced in any established profession, yes, even if you had merely sought, outside of any profession, some easy independent social contact, you would not have been spared this feeling of constraint. It is like this everywhere; but that is no reason for sorrow or fear; if there is no common ground between you and others, then try to be close to things that will not abandon you; the night is still there, and the wind in the trees that crosses many a land; everything is still going on amidst creatures and things, and you can be part; and children are yet, as you were as a child, sad and happy still – and when you recall your childhood you live, once again, among them, the solitary children, and adults are nothing, and their ‘dignity’ has no worth.

And if you are anxious, and agonise over your thoughts of childhood, and the silence and simplicity that accompanies it, because you can no longer believe in a God who appears everywhere within it, then ask yourself, dear Kappus, whether you have really lost God. Is it not rather that you never possessed him? For when could that have been? Do you think a child could grasp him, he whom a grown man could only bear with difficulty, and whose weight crushes the old? Do you think whoever has found him can lose him like a little pebble; do you not rather think that whoever has found him could only be lost by him? And if you decide he was not a part of your childhood, if you suspect that Christ was deceived by his yearning, and Mohammed by his pride –if you are terrified to feel that, even now, he exists not, even at this moment when we are speaking of him, what justifies you then in missing one who never existed, or who has passed away, and in seeking him as if he were lost?

Why not consider him as the one yet to arrive, the one who will come, who has been nearing for all eternity, the future one, the ultimate fruit of a tree whose leaves we are? What stops you from projecting his birth into the future, and living your life as one painful but beautiful day in the history of a long pregnancy? Don’t you see that all that happens is a beginning anew, and why not his beginning, since beginning is, in itself, always beautiful? If he is the most perfect, does not something less perfect have to precede him, so that he can choose himself out of plenitude and abundance? Does he not have to come last, so as to include all in himself, and what would be the point of us, if the one we longed for had already been?

As bees make honey, so we collect what is sweetest of all and make him. Even begin with the slight, the inconspicuous (if it is done out of love), with our work and the rest that follows, with silence, or a small and solitary joy, with all that we do alone, without followers or participants; begin him, he whom we shall not know, as little as our forerunners could know us. And yet they, long past, are in us, as a predisposition, a burden upon our fate, as the blood that flows in our veins, as a gesture that rises out of the depths of time. Can anything deprive you of the hope of existing one day in him, the furthest, the outermost?

Celebrate Christmas, my dear Kappus, with a devout feeling, the feeling that he may require of you this very fear of life, in order to begin; these very days of your transition are the moment perhaps when all in you is labouring towards him, just as you once laboured breathlessly towards him, as a child. Be patient and unconcerned, and consider that the least we can do is to make his arrival no harder than the earth does spring’s arrival when it seeks to appear.

And be glad, be confident,

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter VII: Rome, May 14th, 1904

My dear Kappus,

Much time has passed since I received your last letter. Don’t hold that against me; first work, then interruptions, and finally illness has delayed my reply, which I wished to reach you from calm and pleasant days. Now I feel a little better once more (the early spring with its moody, unpleasant transitions was ill-received here as well), and can greet you, my dear Kappus, and talk to you (as I love to do) of this and that in response to your letter, as best I may.

You will see I have copied out your sonnet, as I thought it was beautiful, simple, and has emerged in a form whereby it flows with quiet decency. These are the best lines of yours I have read. And I am sending you this copy, because it is an important and a new experience, as I know, to read your own work in someone else’s hand. Scan the lines as if it were new to you, and you will feel, inwardly, how much it is yours. It has often been a pleasure to me, to read both this sonnet and your letter; thank you for both.

And you must not allow yourself to become confused in your solitude by the fact that there is something within you that seeks to emerge. It is precisely this urge that, used calmly and deliberately as a tool of your art, will aid in you spreading your solitude over a vaster space. People (with the help of convention) have resolved everything easy, on behalf of the easiest; yet it is clear we must hold to the difficult; everything that lives holds to it, everything in nature grows and defends itself according to its nature, and makes something of itself, tries to be itself at all costs, against all opposition. We know little, but that we must hold to what is weighty is a certainty that will never desert us; it is good to be solitary, since solitude is difficult; that a thing is difficult is all the more reason to choose it.

To love is good too: since love is difficult. For one person to love another: perhaps that is the most difficult thing granted us, the final test and proof, the work for which all other work is merely a preparation. That is why young people who are beginners in everything are not yet capable of love: it is something they must learn. With their whole being, their whole strength, gathered about their solitary, anxious, upwardly beating heart, they must learn to love. But the time to learn is always a long, secluded time, and so loving is, for a long time to come and far into life – solitude, a growing and deepening solitude for those who love. Love, to begin with, is not something that means merging, yielding, uniting with another (for what would a union of the unclarified, unfinished, incoherent be?), it is a sublime moment for individual maturation, to become something within oneself, to become a world, a world for oneself for another’s sake, it is a great and unrestrained claim on one, something that chooses the individual and summons one to vaster spaces. Only in that sense, as the task of labouring at oneself (‘hearkening and hammering day and night’) should the young employ the love that is granted them.

Yet this where the young often err, and most seriously: in that they (whose nature it is to be impatient) throw themselves at each other when love overwhelms them, and scatter themselves, just as they are, in all their carelessness, disorder, confusion…And what can happen thus? What can life do with this heap of half-broken things they call their communion, and would like to call their happiness, as if that were their business, and their future? Each one loses themselves for the sake of the other, and thereby loses the other and the many others who still wanted to be. And abandons the wider space of possibility, exchanging the nearing and fleeing of gentle things, full of foreboding, for a sterile confusion out of which nothing further can come; nothing but disgust at the least, and disappointment and impoverishment, and escape into one of the many conventions erected like public shelters in vast numbers on this most dangerous road. No area of human experience is as hedged with convention as this: there are life-belts of the most varied invention, and boats and water-wings; the social order was able to create every kind of refuge, for since it was inclined to consider the life of love as a life of pleasure, it had to make the pursuit of it easy, cheap, and safe and sure as public amusements are.

It is true that many young people who love incorrectly, that is simply devotedly and incoherently (the average person will always hold to that), feel oppressed by failure and wish to make the situation they are in viable and fruitful in their own individual way – for their nature tells them that matters of love, even less than of anything else of importance, cannot be resolved publicly, according to this or that social contract; that there are questions, intimate question, asked by one person of another, that in every case require a new, special, wholly personal answer – yet how can they, who have already hurled themselves at each other, and can no longer distinguish or differentiate themselves, who no longer possess anything of their own, find a way out of themselves, out of the depth of a solitude they have each already interred?

They act from mutual helplessness, and when, with the best of intentions, they wish to escape the convention that afflicts them (marriage for example) they fall into the tentacled grasp of a quieter but equally fatal and conventional solution; for then everything around them is pure convention; there where everyone acts out of a prematurely merged, troubled communion, every act is conventional: every relationship to which such confusion leads has its own convention, however strange it may be (immoral, that is, in the ordinary sense); yes, even separation would prove a conventional step, an impersonal, chance decision, without strength or fear of consequence.

Whoever considers it seriously, finds that neither for dying, which is hard, nor for difficult love has any explanation, solution, or hint of a path been found; and for these two tasks, which we carry out veiled and pass on without disclosing, no common agreed rule can be discovered. Yet as we begin to test out life as individuals these great things will approach us more nearly. The demands that the difficult labour of love makes on our development are greater than life, and we, as beginners are unequal to them. But if we endure, if we accept this love as a burden and an apprenticeship, instead of losing ourselves in all of that easy and careless game behind which people have hidden from the most serious solemnity of existence – then a small advance and an easing of the burden might be perceived by those who will follow, long after us. That would be much.

We are only now beginning to consider the relationship between one individual and another objectively, without prejudice, and our attempts to live such relationships have no model before them. And yet the changing times contain much that can help our timid beginners. The young girl, the woman, in her new individual purity, will only imitate for a time male behaviour and misbehaviour, and the repetitive male professions. After the uncertainty of such a transition, it will be clearly seen that women only wore the varying multitude of those (often ridiculous) disguises so as to purify their own being of the deforming influence of the opposite sex. Woman, in whom life dwells and lives more immediately, more fruitfully, more confidently, must have become at root more mature, more human than lightweight man, who is not drawn into the depths of life by the weight of that physical fruitfulness, he who, arrogant and hasty, underestimates that which he thinks he loves.

One day (of which even now, particularly in the Nordic countries, sure signs emerge and shine), one day will be young girls, and women, whose name will no longer simply signify the opposite of the male, but something in itself, something that makes one thinks not of limitation, of a mere complement, but only of life and reality: the female human being.

This development will transform the experience of love, so full of error (at first very much against the will of those men who are left behind), and reshape it from the ground up, altering it to a relationship meant to be between one human being and another, no longer one directed from a man to a woman. And this more human love (which will be infinitely considerate and calm, and achieved with kindness and clarity in its binding and loosening) will resemble that which we now prepare, painfully and laboriously, a love that consists of two solitudes protecting and bordering on, and greeting each other.

And one more thing: never think that the great love once imposed upon you, as a boy, is lost; how can you know whether or not you possessed great and virtuous longings and purposes which you still live by today? I believe love remains so strong and powerful in your memory because it was your first deep solitariness, and the first inner work you did on your life. Best wishes to you, my dear Kappus!

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Sonnet

Within my life, with no complaint or sigh,

A deep dark illness trembles in the bud.

The pure snow of my dreams, in the blood,

Consecrates my quiet days passing by;

Yet often a vast question blocks my way,

I shrink, and I become small, and I grow

As cold as the lake-water midst the snow,

Whose depths I’d fear to measure any day.

A sadness takes me, dull, as looms, above,

The grey light of that shimmering summer sky,

Through which, from time to time, a star will show –

And then my hand, it reaches out for love,

While I still seek to pray, in sounds that I,

From my burning tongue, cannot make flow.

(Franz Xaver Kappus)

Letter VIII: Borgeby Gård, Flädie, Sweden, August 12th 1904

My dear Kappus,

I wish to speak to you again for a while, dear sir, though I can say hardly anything that will help you, scarcely anything useful. You have experienced many great sorrows that are now past. And you tell me that their passing was also difficult and distressing for you. Yet ask yourself, if you will, whether these great sorrows have not perhaps passed in and through you. Has much not altered within you, has a change not taken place somewhere in your being amidst your sadness? The only sorrows that are dangerous and harmful are those which one bears amongst others in order to drown out their noise; just like diseases that are treated superficially and foolishly, such diseases simply recede, then after a short time break out all the more terribly; and collect within us as life; unlived life, rejected and lost, from which one can die. If we could but see further than our knowing, some way beyond the first outworks of our presentiments, perhaps then we would suffer our sorrows with greater confidence than our joys. For they are moments when something new enters us, something unknown; our feelings are mute, in shy embarrassment, everything in us withdraws, a silence deepens, and the new, known to none, stands amidst all and is voiceless.

I believe nearly all our moments of sadness are those of tension, which we experience as paralysis because we can no longer hear the life of these unfamiliar emotions. Because we are alone with this stranger who entered, because all that is known and customary has been taken from us for an instant; because we are in the midst of a transformation in which we cannot dwell. That is why the sadness passes, too; the newness in us, all that has been added, and entered our heart, has sunk to its innermost chamber, and does not even dwell there – is already within the bloodstream. And we fail to discover its nature. We could readily be led to believe that nothing had happened, and yet we have been transformed, as a house is transformed when a guest enters. We can’t say who has arrived, we may never know, yet there is many a sign that the future enters us so as to transform itself within us, long before it transpires. And that is why it is so important to be alone and attentive when one feels sad: because that seemingly uneventful and rigid moment when our future enters us is so much closer to life than that other loud, random point in time when it occurs, as if from outside. The quieter, the more patient and open we are, in our sadness, the more deeply and unswervingly the newness enters us, the more we make it our own, the more it becomes our fate; and later when it ‘happens’ one day (steps out of us, that is, towards others) we will feel related, and close, to it within. And this is essential. It is essential – for this is the direction in which our development gradually leads us – that nothing that happens to us should be strange, but simply that which has long been our own. We have already been forced to rethink so many of our ideas regarding motion, that we will gradually learn to recognise that what we call fate emerges from us, and does not come to us from outside. It is simply because so many people failed to absorb and transform their fate themselves while it lived within them, that they failed to see what was emerging from them; it was so strange to them that, in their dreadful confusion, they thought it must have entered them that moment, since they swore they had never found the like within them before. Just as people were long mistaken about the motion of the sun, so they are as yet mistaken about the motion of what is to come. The future is motionless, my dear Kappus, but we move in infinite space. How should it not be hard for us?

And, speaking of solitude once more, it becomes clearer and clearer that fundamentally this is not something once can choose or abandon. We are solitary. We can delude ourselves, and pretend it isn’t so, that’s all. But how much better to see that we are so, indeed to presume it. Then of course vertigo will seize us; since all the places on which our eyes used to rest are removed from us, nothing is near, and the farness is infinitely far. Someone snatched from their room and set, without warning or preparation, on the heights of a vast mountain range must feel the same: an unparalleled insecurity, the exposure to nameless forces that seek to destroy. That person would feel they were falling, believe themselves hurled into space, or blown to a thousand pieces: how tremendous a falsehood their mind would be forced to invent to keep pace with and explain this state of their senses. Thus, all distance and measure alter for those who become solitaries; many such changes occur suddenly, and, as happens to that person atop the mountain, strange imaginings and unusual sensations arise which seem to grow beyond what is bearable. But we must experience that too. We must accept our existence to the furthest point possible; everything, even the unheard-of, must be possible therein. That is, at root, the only courage required of us: to be brave as regards the strangest, the most alien, the most inexplicable of our experiences. That human beings have been, in this sense, cowardly has done immeasurable damage to life; the whole so-called ‘world of the spirit’, death, all those things related to us, have been so completely pushed from our lives by our daily defensiveness, that the senses with which we might grasp them have atrophied. To say nothing of God. But the fear of the inexplicable has not only made poorer individual existence; it has also limited human relationship, lifted it, as it were, from the river-bed of infinite possibility onto that fallow shore to which nothing occurs. For it is not indolence alone that causes human relationships to repeat themselves, from case to case, with such unspeakable monotony and inconsequence, but fear of some new, unforeseeable experience to which one believes oneself unequal. Yet, only those who are ready for everything, who exclude nothing, even the most incomprehensible, will live the relationship with another as something alive, and exhaust their own existence in so doing. And if we think of our individual existence as a room, larger or smaller, it seems that most only come to know a corner of their room, a place near the window, a strip of floor on which they walk up and down. Thus, they acquire a certain sense of security. And yet how much more human is that dangerous insecurity that drives the prisoners in those stories by Edgar Allan Poe to feel out the shape of their dreadful dungeons, cease to be strangers to the unspeakable horrors of their cells. We are not prisoners, though. No traps or snares are set around us, there is nothing to frighten or torment us. We are set here in life, as if into the element to which we are most suited, and through millions of years of adaptation have come so akin to this life that when we are still, through a happy form of mimicry, we can scarcely be distinguished from all that surrounds us. We have no reason to be suspicious of our world, because it is not hostile to us. If it holds terrors, they are our terrors, if it contains abysses then those abysses belong to us; if there are dangers, we must try to love them. And only if we organise our life according to that principle that tells us always to hold to the most difficult will what appears most alien to us become the most familiar and most trusted. How could we forget those ancient myths that stand forth amidst the beginnings of every people, the myths of dragons that, at the last moment, turn into princesses: perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who wait to find us beautiful and brave. Perhaps all that terrifies us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that needs our help.

You must not be frightened, my dear Kappus, when you meet with a sorrow as great as any you have ever encountered before; when restlessness, like light amidst shadows of cloud, flickers over your hands and everything you attempt. Think instead that something is happening in you, that life has not forgotten you, that it holds you in its hand and won’t let you fall. Why would you wish to exclude every sorrow from your life, when you know nothing of what these states of mind are, working within you? Why torment yourself with the question of where all this comes from and where it is going? Since you know you are in transition, and desire nothing so much as to transform yourself.

If there is anything unhealthy in your inner workings remember that illness is the means by which an organism frees itself from what is alien to it; one must help it to be ill, to suffer the sickness entirely, so as to recover. There is so much happening in you, dear Kappus; you must be patient like one who is ill, and confident as a convalescent; for perhaps you are both. And more: you are also the doctor, who must monitor himself. Yet in every illness there are many days when the doctor can do no more than wait. And that, above all, is what you, inasmuch as you are your own doctor, must do now.

Don’t observe yourself too closely. Don’t be too quick to jump to conclusions concerning what is happening to you; just let it happen. Otherwise, it would be all too easy to reproach yourself (morally, that is) as regards your past, which is obviously a part of all you now encounter. But whatever errors, wishes, longings of your boyhood are working in you, they are not what you condemn in recalling them. The extraordinary circumstances of a solitary and helpless childhood are so difficult, so complex, exposed to so many influences and at the same time so divorced from all real connection with life, that where a vice enters it, one cannot simply call it a vice. One must be so careful with naming things in general; it is so often the name of an offence upon which a life is shattered, not the nameless individual act itself, which was perhaps a most definite and necessary part of that life, and could have been absorbed by it with ease. And the expenditure of energy only seems so great to you because you overvalue ‘victory’; that is not the ‘great thing’ you think you’ve achieved, though you are right about your feelings; the great thing is that there was already something there with which you were allowed to replace that self-deception, something true and real. Without it, yours would have been simply a moral reaction without much meaning; yet it has, in fact, become a part of your life. Your life, dear Kappus, which I think of with so many good wishes. Do you recall how that childhood longed for something ‘great’? I see how it yearns, far beyond the great now, for the greater. That is why it does not cease being burdensome, but that too is why it will not cease to grow.

And if there is one thing, further, I should tell you, it is this: do not think that he who tries to comfort you lives without effort amidst those calm and simple words that sometimes do you good. His life contains a deal of hardship and sorrow, and lags far behind yours. Yet if it were otherwise, he would never have been able to find these words.

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter IX: Furuborg, Jonsered in Sweden, November 4th 1904

My dear, Kappus,

During part of this time, that has passed without a letter, I was travelling; at other moments, so busy I could not write. And even now I find it difficult to do so, because I have had to pen so many letters my hand is wearied. If I could dictate this, I would have much to say to you, but as it is, must employ only a few words in reply to your long letter.

I often think of you, my dear Kappus, and with such concentrated good wishes that it should help you in some way. Yet whether my letters are in fact a help, I often doubt. Don’t say: ‘Yes, they are’. Simply receive them calmly and without many thanks, and let us wait and see what comes of it.

There is little point perhaps in my delving into the specifics of your letter; for whatever I could say about your tendency to doubt, or your inability to harmonise your outer and inner life, or about all the other things that trouble you – is exactly as I have already, and always, said: the wish, always, that you may find sufficient patience in yourself to endure, and enough simplicity to believe; that you may win to a greater and greater confidence in what is difficult, and in your solitariness amidst others. As for the rest, allow life to happen to you. Believe me: life is always in the right, in every situation.

With regard to feelings: all feelings are pure that unify and elevate you; the only impure feeling is that which grasps only one side of your being and so distorts you. Everything you can derive from childhood is good. Everything that makes you more than you have been, even in your best hours, is right. Every gain is good, if it fills your whole bloodstream, if it is not intoxication or murkiness but joy you can see, clear to the depths. Do you comprehend what I mean? And your tendency to doubt can be a fine quality if you cultivate it. It must become understanding; it must become analysis. Whenever it seeks to mar something, ask why this ugliness? Demand evidence, examine this tendency of yours, and you may find, within it, bewilderment, embarrassment, even rebelliousness. But never yield to it, argue the case every single time, and do so carefully and consistently, and the day will arrive when that which seeks to destroy will become that which toils the best on your behalf – perhaps the most intelligent of all that works at building your life.

This is all, my dear Kappus, I am able to say to you today. Yet I am sending you, with this, the reprint of a little poem that appeared in the Prague Deutsche Arbeit. Within it, I shall continue to speak to you about life and death, and how both are great and glorious.

Yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

Letter X: Paris, Boxing Day, 1908

You should know, my dear Kappus, how pleased I was to have your fine letter. The news it brings me, solid and official as it is now, seems good to me, and the longer I considered it the more I found it truly good. I wanted to write on Christmas Eve and tell you this; but, with the work in which I am variously and continuously involved this winter, the annual festival has arrived so swiftly I have scarcely had time to perform the most essential errands, much less write to you. But I have thought of you, often, during this holiday and imagined how quiet it must be in your lonely fortress amidst bare mountains upon which those great southern winds fall as if they wanted to devour them piece by gigantic piece.

The silence must be immense in which such noise and motion can find room, and if one considers the added presence of the distant sea, sounding perhaps as the innermost tone in that prehistoric harmony, then one can only wish that, trustfully and patiently, you are allowing the vast solitude to work upon you, a solitude that can no longer be erased from your life; that will continue to act, as a gentle anonymous influence on all you will come to experience and perform, both continuously and decisively, rather as the blood of our ancestors flows endlessly in our veins and combines with our own, to form the unique, unrepeatable being we believe ourselves to be at every turn of our lives.

Yes, I am glad that you have your solid, official existence there; the title, the uniform, the service, all that is tangible and limited; which, in such isolated surroundings and with so small a contingent, demands a necessary seriousness, a vigilant application, beyond the mock, time-consuming routines of a military profession; a seriousness that not only allows independent thought, but actually cultivates it. And to be placed in situations that work upon us, that place us in front of the grandeur of natural things now and then, is all that is needful.

Art too is simply a way of life, and however one lives one can prepare for it unconsciously; one is closer to it in every real existence than in the unreal quasi-aristocratic professions which, while pretending to be artistic, in practice deny and attack the whole body of art, as for example does journalism, virtually all criticism, and a good three-quarters of what is called, and seeks to be called, literature. I am glad, in a word, that you have escaped the danger of such an outcome and that, somewhere in that harsh reality, you stand alone and courageous. May that support and strengthen you, in the year ahead.

Ever yours:

Rainer Maria Rilke

The End of Rilke’s ‘Letters to a Young Poet’