Wolfram von Eschenbach

Parzival

Book X: Gawain and Orgeluse

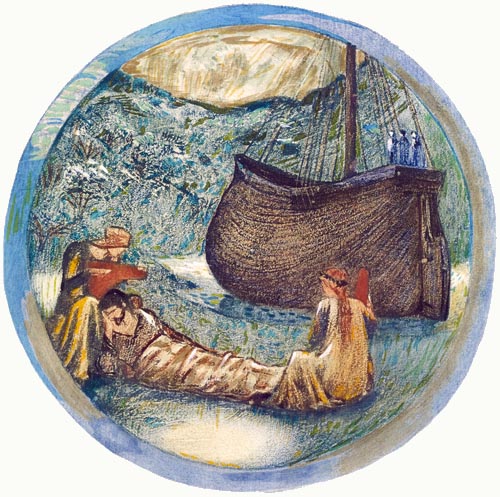

‘Meadow Sweet’

From The Flower Book, Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833 – 1898)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Gawain, cleared of guilt, pursues his quest for the Grail.

- Having saved the life of Urjans of Punturteis, he reaches Logroys.

- Gawain encounters the lovely Orgeluse de Logroys.

- He continues his travels, in company with Lady Orgeluse.

- Her squire Malcreatiure, brother to Cundrie La Surziere, rides after them.

- Gawain finds the wounded Urjans once more.

- He tells Lady Orgeluse the tale of Urjan’s crime.

- Wolfram’s comments on True Love.

- Orgeluse departs on the ferry.

- Gawain encounters and defeats Duke Lischois Gwelljus.

- He pays the master of the ferry, Plippalinot, his due.

- Gawain is a guest of Plippalinot, and meets his daughter Lady Bene.

Gawain, cleared of guilt, pursues his quest for the Grail

NOW we approach the strangest tale,

That may o’er happiness prevail,

And yet in turn may bring us joy,

Both powers this story doth employ.

The set term, of one year, had passed;

The quarrel was resolved at last,

That duel, sought at the Plimizoel,

And then transferred to Barbigoel

From Schanpfanzun, was now set by,

Kingrisin unavenged thereby.

Though Vergulaht accused Gawain,

Yet their kinship was made plain;

Moreover, twas Count Ehkunat,

Had slain Kingrisin, and yet that

It was they’d laid at Gawain’s door;

The Landgrave, Kingrimursel, saw

Gawain cleared of the accusation,

And thus was ended their division.

Now King Vergulaht and Gawain

Both sought the Grail to obtain,

And at the same hour, on a day,

Each man went his separate way.

It was a quest that would demand

Many a conflict, sword in hand,

For whate’er man desires the Grail

Must don his armour without fail,

Only thus is glory striven for.

How the guiltless Gawain now bore

Himself, and all that then was done

When he set out from Schanpfanzun,

And whether he was forced to fight

Let those relate who saw the knight;

Yet he will meet with battle here.

One morn, Gawain did thus appear

On a green meadow where a shield,

Which had been pierced in the field,

Hung from a bough; and a palfrey,

Harnessed there for a noble lady,

All equipped with a costly saddle,

Was tethered to it, by the bridle.

‘Who can this woman be,’ he thought,

‘That a warlike shield has brought?

Should she choose to launch an attack,

How shall a poor knight answer back?

Tis better now if I dismount,

Then of myself give true account.

Though she, if foot to foot we fight,

And we both go the distance, might

Topple me, yet may I win favour

From this affair, or find disfavour.

Though Camilla herself were come,

Who earned her fame at Laurentum

By deeds of arms, and Camilla

Were to challenge me with vigour,

I’d try her mettle nonetheless.’

The shield had known much distress,

Twas badly gashed Gawain now saw;

A window, wide as any door,

A broad spear-head had opened there;

The battlefield had laid it bare.

Now, who would pay the blazoner,

If such proved his only colour?

The body of the tree was wide,

Behind it, on the farther side,

Sat a lady, on the clover,

Grieving as if joy were over,

So deep it seemed was her woe.

As round the tree Gawain did go,

And, thus, the lady came in sight,

He saw, laid on her lap, a knight,

The cause indeed of all her pain.

As he greeted her, Lord Gawain

She acknowledged, with a bow;

Her voice was hoarse, suffering now

From her cries of pure distress.

He dismounted, and did assess

The wounded knight who, pierced right through,

Bled within, and outwardly too.

Gawain asked the knight’s lady

Whether he lived, for, so badly

Was he wounded, he could not know.

‘He lives yet, sir,’ she said, ‘although

It cannot be for long, I deem.

God has sent you, it would seem,

Sustain me then with your counsel;

You must know such matters well,

Grant me your aid and comfort, then.’

‘Madame I shall,’ he answered, ‘when

Blood presses on the heart, then one

Employs a hollow tube; if done,

Then I would guarantee his life,

Twould cure him such that, free of strife,

You might see and hear him, oh,

Full many a day; no fatal blow

Was this.’ Gawain then took a stem,

Slit and peeled its sheath, and then

He took the hollow tube it made,

(Skill was his, in bringing such aid)

And sank it in the knight’s body,

Through the wound, yet delicately,

Then told the lady to suck until

The blood the hollow tube did fill,

Whereon the warrior regained

Consciousness, and strength obtained

To speak, and thank Gawain, seeing

The knight across his body leaning,

And praised him that he had brought

Him from out his swoon, and sought

To know if to Logroys he came

Pursing chivalry, and fame.

Having saved the life of Urjans of Punturteis, he reaches Logroys

‘I myself sought adventure here,

Roving from Punturteis; too near

I did ride, to my deep regret;

If you’re a man of sense forget

This place; for truly I dreamt not

That Lischois Gwelljus, nigh this spot,

Would wound me, and set me down,

Behind my horse, upon the ground,

With a great blow, piercing sorely,

Wounding thus my shield and body.

Twas after that this noble lady

Helped me here, on her palfrey.’

He begged Gawain then to stay,

But the knight would make his way

To the place where it was done.

‘If Logroys lies so near, then one

May overtake the man outside

Its walls,’ my Lord Gawain replied,

‘And he will answer there to me,

And justify his enmity.’

‘Do nothing of the sort’, the knight

Answered, ‘I can explain, outright.

Tis no child’s play to travel there,

Towards mortal danger you’ll fare.’

The knight’s wound, then, Gawain bound,

With a kerchief the lady found;

He spoke a charm, and left them there

Commending both to God’s good care.

He found the trail they’d left behind

All bloody, as if from stag or hind,

And thus it served to point the way.

Full soon, Logroys before him lay;

Both praised, and honoured, everywhere.

The castle was both strong and fair,

A path about it, spiralling round;

A child’s top was that castle mound!

When simple people saw that sight,

They thought it spinning in the light.

Folk claim of that place even now,

None could attack it, and I’ll allow

Men there had little fear of aught

Malice could do, or anger sought.

All round the hill a palisade

Of cultivated trees, a glade

Was planted, pomegranates, figs,

Olives; vines, close-pruned to sprigs,

And other fruiting things grew there.

Gawain had ridden near to where

The path ended, when glancing right

There came in view a pleasant sight.

Though twas destined to bring him pain,

It gladdened the heart of Lord Gawain.

Gawain encounters the lovely Orgeluse de Logroys

FROM the rock there flowed a spring,

Beside which there stood a pleasing

Lady. He gazed with true delight,

Despite himself, did our brave knight.

She was the fairest flower, the lovely

Pinnacle of female beauty.

But for Condwiramurs, no fairer

Woman was born in this world ever.

She was of radiant looks, refined

In courtly ways, her form defined

In shapely manner, and her name

Orgeluse de Logroys, that same

Of whom the story tells that she,

Being a fair and wondrous lady,

Was ever a lure to love’s desire,

Sweet balm to the male eye afire,

A means to pluck the least heartstring.

Gawain offered her fair greeting.

‘If I might descend, by your leave,

Madame, and should you conceive

A wish, indeed, for my company,

Then I declare, of a certainty,

Joy would replace my every woe,

No knight could prove happier so;

I’m fated to die without seeing

Any woman to me more pleasing.’

‘Tis well, but what is that to me?’

She said, inspecting him carefully,

And her sweet lips went on to say:

‘Praise me in not too fine a way,

Or from it you may reap disgrace.

Not every man may judge my face,

For if every fool were free to praise,

Not just those with discerning ways,

And the words were naught but flattery,

What credit would that bring to me?

How would my praises be worth more

Than others’? For I mean to ensure

That mine are those of the discerning.

Of who you are, sir, I know nothing,

Tis time you went, but you, in turn,

Shall now my own true judgement earn:

You are near my heart, but not in it.

If you’d have my love, must earn it.

Many a man who insists on gazing

At that which his heart finds wounding,

Hurls his glances about so wildly,

A sling in battle works more gently.

Bowl your desires, however fine,

At some other target than mine.

If you are a man who serves for love,

If need for adventure you doth move,

Deeds of arms for a lady’s favour,

Here, of me you’ll win no honour.

If I speak truly, dishonour here

Is all that you will earn, I fear.’

‘You speak truly, and no disguise,

Madame, at risk now from my eyes,

Is my heart indeed, for they dwell

On you so, that, as you may tell,

I am your prisoner; treat me then

As a true woman should do, when,

Though she wishes me to depart,

She’s prisoned me within her heart.

Loose or bind me, for you will find

Such is the tenor of my mind,

That if I had you where I wish

Then all were paradisal bliss.’

‘Take me away with you,’ said she,

‘And aught that you may win from me

With your wooing, will only end

In regret, to disgrace twill tend.

I would see if you would make

War on other men for my sake,

Yet, if honour’s dear to you, refrain.

Let me counsel you once again,

And labour to do as I shall say,

Go seek for love some other way.

For if with my love you would toy,

You will fail of both love and joy.

Take me away with you, and see

Trouble to you will come of me.’

‘Who then, without deserving it,

Is for a lady’s true love fit?’

Said Lord Gawain. ‘If I may speak,

A man that a lady’s love doth seek

Without deserving it, doth sin.

For any man that’s eager to win

A noble love, must serve before,

And after, he wins it; tis my law.’

‘If you’d serve me,’ said the lady,

‘You must lead a life of chivalry,

Yet all you’ll win is dishonour,

I need no coward’s service. Further

Along the path now you must go,

Follow the track (there is no road),

It reaches the orchard by and by,

Over a bridge, narrow and high;

Cross the bridge, and there’ll you see

My palfrey tethered to a tree,

And a crowd of people dancing,

And sweet love songs they’ll be singing,

Playing on flutes and tabors too.

Loose the mount; it will follow you.’

Gawain leapt down from his charger,

And sought to find a place to tether

His horse, so it might await him so;

Naught by the spring suited though,

And he wondered if it were seemly

To seek assistance from the lady,

And ask her to hold his mighty steed.

‘What troubles you, I too can read,’

She said: ‘Come leave your mount with me,

And go your way in security,

I’ll hold it till you’re here again,

Though in serving me there’s little gain.’

By the bridle the horse he led:

‘Hold this for me, my lady,’ he said,

‘Why, you’re a fool!’ she cried, ‘For see,

Your hand has touched it, as for me,

I’ll not lay hold of it.’ ‘Madame,

This end I touched, fool that I am,

But not the other,’ the hopeful said,

‘Well, I’ll take it; now, once you’ve sped

O’er the bridge and back, bringing me

My mount, as to keeping company

Then I shall grant you your wish.’

Gawain was well content with this.

He left her and o’er the bridge did go,

And in at the orchard gate, and so

Came where many a fair lady,

And bachelor knights a plenty,

Many more than one and twenty,

Sang, and danced about there, gaily.

Now at the sight of Lord Gawain,

Dressed so finely, they were fain

To grieve, in that orchard, for they

Were good-hearted; of all who lay

Or sat, in their pavilions, or stood,

Not one there, be it understood,

But voiced their woe. Many a knight,

And lady, grieved there at the sight:

‘With her deceitful ways, tis plain,’

They said, and said the thing again,

‘My Lady plans now to entice

This man (they repeated it twice)

To toil for her, and so he will,

And yet win sorrow for it still!’

Many a worthy man did take

His hand, and give it a friendly shake.

He then approached the olive tree

Where the palfrey, as he could see,

Was tethered, its harness and bridle

Worth many a mark. By it did idle,

A knight with a grey braided beard,

Who, as my Lord Gawain had neared,

Bewept him coming for the horse,

Yet spoke him kindly, in due course:

‘If you are open to sound advice,

Then I would bid you, sir, think twice,

And lead not the palfrey this day,

Though none will stand in your way.

For if you’ve ever done what’s wise,

You’ll leave the horse, as I advise.

Accursed indeed shall be My Lady

For causing the deaths of so many.’

Gawain said no, he’d not do so.

‘Then, alas, for what doth follow,’

Cried the old grey-bearded knight,

He then unloosed the halter quite’

‘There is no need to wait, allow

The palfrey to follow you now,

And may He whose hand divine

Made the seas with all their brine,

Grant you aid in your hour of need.

Beware, lest her beauty, indeed,

Makes mock of you, for her sweetness

Is bound up with a deal of sourness,

Like a hailstorm in bright sunlight.’

‘In God’s hand be it!’ said our knight.

He continues his travels, in company with Lady Orgeluse

HIS leave he took, and here and there

That of others, while grief and care

And mournful cries were now expressed.

The palfrey followed him, midst the rest,

Along the narrow path, to the gate,

And o’er the bridge to meet their fate,

For the Lady of the land was there,

His heart’s mistress in this affair.

Though his heart sought refuge with her,

Through her, twould be made to suffer.

The fastenings of her headdress she

Had pushed up on high, summarily,

And when one sees a woman so

She’s ready for conflict, although

She may have a mind to sport, also.

And what else was she wearing? Oh,

If I thought to say aught of her attire,

Her looks would absolve me entire.

As he approached, this was the way

Her sweet lips addressed him: ‘Hey,

Welcome back you goose, if you

Will serve me, you’ll find tis true,

None have ever borne such a load

Of folly as you’ll bear on the road,

Yet you’ve good cause to forebear.’

‘Though you’ve anger and to spare,

Now,’ Gawain said, ‘yet, in the end,

Sweet favour to me you’ll extend.

Though you may scorn me further,

You’ll grant me satisfaction later.

Meanwhile my service I’ll render

Till my reward you shall tender.

I’ll help you mount, if you desire.’

‘I asked you not, I’ll not require

Your unknown hand to work so,

Seek some baser forfeit, below!’

And from midst the flowers she leapt

On to her horse, twas most adept,

And had him mount and ride ahead.

‘What a pity it would be,’ she said,

Were I to lose my fine companion,

Yet God may bring you to confusion.’

Now he who would heed my advice

Will not malign her, but think twice.

And not exercise his tongue till he

Knows the full tale, and all that she

Might feel now, in her present state.

Though I, tis true, might remonstrate

With that lovely woman somewhat,

Yet whate’er the earful Gawain got

From her in her bouts of ill-humour,

Or the trouble she brought him later,

No matter the pain, or its amount,

I exonerate her on every count!

Orgeluse now started, not like one

Eager to prove a good companion,

For she came riding towards Gawain

In such a fury that, it was plain,

He needs have small hope of release

From care through her, or any peace.

They rode o’er a heath bright with flowers,

And here Gawain who knew the powers

Of many a herb spied one whose root,

He said, some grievous wound might suit.

The noble knight descended, then

Dug up the root, and mounted again,

While the lady did not forbear

To exclaim, as she watched him there:

‘If my companion works skilfully

In physic, and not mere chivalry,

And learns to hawk salves and things,

Why, a decent living such toil brings.’

‘I rode by a tree, and there had sight,’

Said Gawain, ‘of a wounded knight,

And, if he is there yet, the strength

Of it should restore him at length.’

‘I should like to see that,’ she said,

And learn physic to earn my bread?’

Her squire Malcreatiure, brother to Cundrie La Surziere, rides after them

A squire there came riding swiftly

With a message, and when, shortly,

Gawain halted, as he drew near,

He was struck by what did appear;

A monstrous proud squire was he,

Called Malcreatiure, and Cundrie

Was his fair sister, and like to her

Was he, but of a different gender.

His two fangs, on a similar plan,

Suited a wild boar, not a man,

Though his hair was not as long

As that which dangled down upon

Cundrie’s mule, but short and prickly,

Like a hedgehog’s coat exactly.

Such folk are found in Tribalibot,

Beside the Ganges, tis their lot

To suffer this mischance at birth.

Once God had seeded life on Earth,

Adam, our father, named each thing,

The wild and tame understanding

The nature of each, and the seven

Lights that circled him in heaven

With their innate powers, and he

Knew of each herb some property.

Now when his daughters reached

Child-bearing age then Adam preached

To them of intemperate excess,

And on them he would e’er impress,

When a child they were carrying,

That to ensure that their offspring

Was undeformed, and an honour

To their race, all in their power

They must do, to seek not to eat

(And, thus, with good fortune meet)

Any herb ‘but those God created

For us, when He sat, and mated

Flesh to bone, in achieving me.

‘My daughters, be not blind,’ he said,

‘To how true happiness is bred.’

Those girls (is it any wonder?)

Did according to their nature.

Some, led by frailty, to forget,

Ate that on which their hearts were set,

So that to Adam’s bitter sorrow,

Deformed progeny did follow.

Yet he was firm of purpose still.

Now a queen there was, Secundille,

Whom, with his deeds of chivalry,

Feirefiz won, queen, realm, and all,

And she had many such folk withal.

Since ancient days they’d appeared,

Bodies ill-formed, features weird.

Secundille was told of the Grail,

And how its splendours did avail,

The finest thing on earth it was,

And guarded by King Anfortas.

She found it strange for, to her land,

Many rivers brought gems not sand,

And she had mountains full of gold.

‘How shall I his secrets unfold,

This man who commands the Grail?’

She wondered, and, so runs the tale,

Sent him a gift, a human wonder,

Namely Cundrie, and sent with her

Malcreatiure her brother,

And, I swear, a deal of treasure

Such that you could never buy,

For none has it to sell, say I!

Anfortas, whose very nature

Was generous, gave this creature

To Orgeluse, to be her squire,

Though born of intemperate desire,

That set the man, body and mind,

Far from the mass of humankind.

Gawain waited for him; kindred

To herbs and stars, the man shouted,

As he approached, on a sorry horse

That limped and stumbled in its course.

(Lady Jeschute rode one far better

That day when Parzival saw her

Return once more to Orilus’ favour,

Which no fault of hers had lost her.)

‘Sir!’ cried Malcreatiure, angrily,

Fronting Gawain, ‘from decency,

You might have chosen to refrain.

A fool you are if you to seek to gain

Aught from absconding with my lady

In this manner. Praise would surely

Come to you, could you but evade

Punishment for the choice you’ve made.

If you’re a warrior, cudgels shall so

Scrape your hide that, at every blow,

You’ll think yourself far otherwise.’

Gawain looked him hard in the eyes.

‘My person has never suffered such;

Tis the shiftless mob, not overmuch

Given to manly deeds, who deserve

That such a lesson you should serve;

No man has punished me before.

Should you, and this lady, ignore

All courtesy, and insult me here,

Tis you shall have reason to fear,

What you may rightly call, my anger.

Howe’er dreadful the face you offer,

Your threats I’ll counter readily.’

Gawain seized his hair and, promptly,

Flung him from his horse to the ground,

Where the wise squire could be found

Gazing up at him timidly.

Yet his hedgehog bristles deeply

Pierced Gawain’s hand, and blood

Covered it; a revenge made good.

The lady laughed: ‘I love to see

Such fine folk quarrelling over me!’

Gawain finds the wounded Urjans once more

THEY set off again, the squire’s horse

Limping beside them till, in due course,

They arrived where the wounded knight

Was lying; kindly addressing his plight,

Gawain bound his wound with the herb.

‘What nest of troubles did you disturb,

On leaving here?’ said the wounded man.

‘You bring a lady whose sole plan

Is aimed at harming you. Through her,

Came my injury, for she led me, sir,

Into narrow straits, and fierce strife,

At the risk of my property and life.

If you would save your own, allow

That faithless woman to vanish now;

Have nothing more to do with her.

Judge from my sad state what further

Pain her counsel may bring to you.

Yet I might recover wholly too,

If I could but find a place to rest.

Help me to that, and so be blessed.’

‘Ask aught from me you might name,’

Said Gawain, ‘I’ll attempt that same.’

‘There’s a hospice, not far away,’

Said the wounded knight, ‘if this day

I might reach it I’d seek their care.

My companion’s mount stands there,

Set her upon it, place me behind.’

Gawain, with this intent in mind,

Untethered the palfrey from its tree,

And led it towards her, carefully,

But the wounded man cried: ‘Stay,

Would you trample me along the way?’

So Gawain slowly circled round.

A sign from the man on the ground

Sent the lady following Gawain,

At a gentle pace, till she might gain

The saddle, with his help; and now

The wounded knight, leapt, and how,

Onto Gawain’s Castilian steed.

If you ask me, twas a sinful deed.

They sought not to prolong their stay,

And, with the spoils, they rode away.

Gawain gave vent to anger, though

His lady found more in his woe

To laugh at than he found pleasure.

He’d lost his steed, thus she did utter

These words from her sweet lips: ‘I,

Thought you a knight yet, by and by,

You turned surgeon, and now I see

Tis as a footman that you’d serve me!

If any can make a living still

From his wits, a place you’ll fill.

But, do you still desire my love?’

‘Yes, my lady, could I but prove

I possessed it then it would be

Dearer than aught on earth to me.

If I were offered a choice between

The riches of every king and queen

Beneath the sky that wears a crown

And wins joy, honour, and renown,

And you, my lady, then my true heart

Would leave the riches, for my part,

To them. For tis your love I wish.

And if I may not win it in this

Manner, I’ll die a bitter death!

On me, your own, you waste your breath,

For if I was ever free before

I now am subject to your law;

And I judge it your given right.

Whether you name me as a knight,

A squire, peasant, footman, yet you,

By the jests you subject me to,

And your mockery of my service,

You win a burden of sin in this.

Were I to profit from some deed,

Then you will change your tune indeed.

Though your scorn ne’er vexes me,

It lowers your worth, assuredly.’

The wounded man rode back again,

And called to our knight: ‘Are you Gawain?

If you e’er borrowed aught from me,

Tis now repaid, of a certainty.

Lord Gawain, you should remember

That I was one you did overpower

And in that joust took my surrender,

And led me off to your King Arthur,

Who saw that with the hounds I ate,

And hungered a whole month straight.’

‘Are you Urjans?’ Gawain replied.

‘Why should I suffer for your pride?

I won the King’s pardon for you.

Ignoble thoughts you did pursue,

And were excluded from the Order

Of Knighthood, beyond the border

An exile, for denying a free

Maid her inviolability,

And due protection of the law.

King Arthur sought to ensure

You saw the gallows; had not I

Spoken for you, why then, say I,

You’d have hung high in the air.’

‘Whatever might have happened there,

Here we are. You will have heard

The saying, tis an ancient word,

That, if a man should save another

From death, he’ll be his foe thereafter.

I’ve my wits about me, tis known,

Babes do weep, not men full-grown,

And so, the charger I’ll keep this day.’

He spurred hard, and galloped away

Much to Gawain’s anger, indeed,

As he watched the departing steed.

Then he turned to his fine lady,

And began to tell her the story.

He tells Lady Orgeluse the tale of Urjan’s crime

‘HERE is the tale,’ said Lord Gawain,

‘It was when Arthur did maintain

His court at fair Dianazdrun,

Attended there by many a Briton.

Now to his land had come a lady,

As envoy from another country,

While Urjans, a mere outsider,

Had come there to seek adventure.

He was a guest there, so was she.

And yet his base thoughts, sinfully,

Led him to seek from her his pleasure,

Against her will, he had full measure.

Twas nigh a forest, and her cry

Was heard as we hunted, nearby.

The King, he called aloud, and there

We all hastened, and I did repair

To the place ahead of the rest,

This I found the villainous guest,

And led him back, my prisoner,

To the king but a short time later.

The maid rode back along with us,

Although her state was piteous;

No loving servitor was he

Who’d stolen her virginity,

Nor indeed had his knightly fame

Increased, in tarnishing his name,

By raping a defenceless maid.

Kind-hearted Arthur was dismayed,

Well-nigh beside himself with anger,

He could restrain himself no longer:

‘This outrage should stir our pity!

Perish the day this savagery

Was enacted, in this kingdom,

Where I seek justice! Young woman,

Bring a case now, don’t hesitate

And be your own best advocate,’

He said, while turning to the lady,

Who followed his counsel promptly.

There came a host of noble knights,

To hear the girl defend her rights,

Who gathered where, Urjans, the lord

From Punturteis, stood before

Arthur of Britain, both his honour

And his life at stake, while over

Against him, where rich and poor

Could hear her, she took the floor,

And bravely petitioned the King,

In the name of womankind, asking

Him to take her shame to heart,

For maidenly honour, on her part,

And the rules of the Round Table,

And as an envoy, and were he able

So to do, pronounce his judgement,

And said with this she’d rest content.

She begged the company of knights

To apprise themselves of her rights,

For she’d been robbed of what she

Could ne’er regain, her virginity,

And they should ask the King also

For judgement, and speak her woe.

The guilty man, devoid of honour

In my view, sought a defender,

An advocate who did his best

Though all in vain; for the rest,

Prince Urjans was condemned to die,

With loss of honour, for by and by,

Of willow they’d twist a garotte,

Strangulation was to be his lot,

Wherein no blood would be shed.

Then he appealed to me, and said

That it was I took his surrender,

Granting him life. I feared my honour

Would be lost, and asked the lady

Since she had witnessed the manly

Manner of vengeance I had wrought,

To quell the anger in her thought,

And accept that her beauty might

Have maddened the aforesaid knight.

‘If ever a lady has helped a man

Whose deep desire grew out of hand

In the sequel, honour it now,

And mercy on this wretch allow.’

I begged the king, and each follower,

If I had done him service ever,

To bear it in mind and, of his right,

Lighten the sentence on the knight,

And avert the shame I would incur.

I entreated the Queen (for with her

I had ever sought refuge at court,

Winning help of the King’s consort)

By the love born of ties of blood,

For he had reared me from childhood,

To help me, now, and she did so,

Spoke with the King and then also

Sought a further word privately,

With the girl, as the injured party,

And thanks to this he was saved,

Though his action was depraved.

Nonetheless he was made to suffer,

Was punished still with dishonour,

For with the hounds he must eat

Out of the trough, and complete

His atonement in four weeks, thus,

The lady proving magnanimous.

Yet though she did her wrong avenge,

This deed, madam, is his revenge!’

‘It shall not succeed,’ said Orgeluse,

‘All favours to you I might refuse,

But he shall have his reward before

He leaves my realm, and count it more

Of a disgrace than he found there;

For the King, in this whole affair,

Has quite failed to avenge the deed,

In his land, where the lady indeed

Suffered from that shameful action,

Yet, here, I have jurisdiction;

Though I knew not either’s name,

Before, you’re subject to the same

Law, my law; he must be brought

To battle and a lesson taught,

Though for that lady’s sake alone,

Not, lest you think it, for your own!

Great misdeeds should be repaid

With thrusts and blows, of lance and blade.’

Gawain went to Malcreatiure’s steed,

And caught its bridle, twas frail indeed.

The squire came to them, and the lady

Told him in heathen speech, swiftly,

All she wished done at the castle.

Now it is nearing, Gawain’s peril!

Malcreatiure went off on foot

While Gawain took a closer look

At the squire’s horse, but thought

It too poor a creature to be fought.

The squire had it from a peasant

Ere he mounted, yet, at present,

Gawain could do naught but suffer,

Doomed to employ it as his charger.

Maliciously, the lady said,

‘Why do you not ride on ahead?’

‘I shall do so when you grant leave.’

Answered Gawain: ‘Then, I believe,

You’ll wait forever!’ the lady cried,

‘Yet I’ll serve to gain it!’ he replied.

‘Then you are a fool so to do!

I tell you twill be the worse for you;

You’ll go not as the joyful go,

But ever find fresh trouble and woe.’

‘I must serve you, in sorrow or joy,

Riding or walking, tis my employ,

For love, it was, so instructed me.’

Standing now, beside the lady,

He inspected his poor charger,

Its lime-bark stirrups, moreover,

Were unfit for the mildest battle,

And oft he’d had a finer saddle;

He feared to ascend, lest his feet

Rendered its harness incomplete.

The creature had a hollow back,

Such that in mounting, to attack,

It might well cave in altogether,

A thing he must avoid; however,

Though in the past he well might

Have balked at it, as a proud knight,

A victim, now, of circumstance

He led it, carrying shield and lance.

The lady, source of so much pain,

Laughed joyfully at Lord Gawain.

As he tied his shield to the steed,

She asked: ‘Are you now turned indeed

To a merchant, with goods to sell?

Whom should I thank? For tis well

To possess a doctor and a trader;

Beware though of my tax-gatherer,

He’ll rob you of your good humour:

Beware the customs posts, your honour!’

But with her jests he was well-content,

Not minding what she said, intent

On that which drove the pain away:

To him she was the spirit of May,

The blossoming of all things bright,

Sweet to his eye, a shining sight;

And yet a bitterness to his heart.

Since a man could, in equal part,

Both lose and find his joy in her,

Then ease the pain he must incur,

It made him, at all times, he found

Both wholly free yet tightly bound.

Wolfram’s comments on True Love

MY authorities make the claim

That Cupid and Amor, those same

Whose mother is Venus, oft inspire

Love in folk, with their darts and fire.

Such love is suspect, yet if a true

Faithfulness lives there in you,

You will never be free of love.

Now joy, now woe, such love doth prove,

Yet true loyalty is love benign.

Cupid your arrows, oft fired blind,

Miss me, your target, and what’s more,

So does that lance-thrust from Amor;

If you o’er love possess the power,

With Venus’ torch from which we cower,

The pangs they bring I never feel.

If I the marks of love reveal,

Then they derive from faithfulness.

If I’d the knowledge, nonetheless,

To aid a man against Love’s pain,

Well, I’m so fond of Lord Gawain,

I’d help him, and forego the pay.

When all’s said, no shame this day

Is his that he is chained by Love,

Love, that all defence doth prove

In vain. He is so capable

Of strong defence, forever able

To prove himself a man of worth,

No woman, howe’er fair, on earth

Should harass his noble person,

Nor work her harm on such a one.

Ride near, Lord Tyranny of Love!

You savage Joy, as if you’d move

To pierce her full of holes, and Woe

To that same source of pain doth go.

Indeed, Woe’s tracks are so plain

That had her march swerved again

From Heart’s Deep, I’d have said

Joy’s was the advantage instead.

If Love should seek to misbehave,

She is too ancient, yet she’ll save

Her sharpest darts for lover’s fears,

And blame it on her tender years!

I could condone her wantonness

In youth more readily, I confess,

Than her misbehaviour in old age.

Yet she is trouble at every stage:

Which age of hers shall I condemn?

If youthful urges prompt, and then

She scorns the old and settled ways,

She’ll lose both renown, and praise.

She needs to comprehend more clearly:

That love is pure I prize more dearly,

All who are wise agree tis so.

For where such tender feelings flow

Towards their like, transparent, calm,

Neither demurring where Love’s balm

Burns true, Love sealing their two hearts,

(Free of mistrust and subtle arts),

With strong and lasting faithfulness,

High above all others, tis blessed.

Orgeluse departs on the ferry

PLEASED though I should be, I say,

To fetch my Lord Gawain away,

He cannot now escape love’s woe;

What aid then from me could flow,

Despite my words? A man of worth

Should not deny true love its birth,

If only because Love must save him,

Love’s embrace may yet redeem him.

Gawain must toil because of love:

She shall ride, he on foot must move.

Now Orgeluse, and our brave knight

Entered a forest, dark as night;

To a tree-stump his steed he led,

And took the shield that, as I said,

It carried, slung it round his neck,

Mounted, and resumed the trek.

The horse scarce managed to provide

A seat, till on the other side

Of the forest where ploughlands lay

He saw a castle, and, truth to say,

His heart and eyes both confessed

They’d ne’er known a castle blessed

With such magnificence, its towers

Its halls, more numerous than ours.

Nor could Gawain help noticing

Fair ladies, at the windows leaning,

Full four hundred of them, or more;

Of famous lineage, there were four.

A causeway the marsh led over,

Towards a navigable river,

Broad and swift; his lady and he

Now rode towards it, cautiously.

Beside the quay lay a meadow

Where courageous men did follow

The arts of war, and jousts deliver;

The fortress loomed above the river.

In the meadow he saw a knight,

One not known to shirk a fight.

Proud Orgeluse, said haughtily,

‘Bear me out, you now will see

I never break my word; I said

Be all this upon your own head;

I told you you’d reap dishonour,

Now if you would save your honour

Defend yourself as best you can.

He’ll topple you, that nobleman,

His strong right arm will achieve

Your downfall and, I do believe,

You run the grave risk you’ll tear

Your fine breeches, here and there,

And then you must bear the shame,

For the ladies may then proclaim

The fact, all those who sit and gaze,

And view whate’er the field displays!’

The master of the ferry now brought

The vessel over, as Orgeluse sought,

And, to Gawain’s sorrow, she cried

As she boarded: ‘Stay on your side!

You may not join me here on board,’

Her words scant courtesy did afford,

‘For fortune’s pledge you must be!’

‘Why so fast? he cried, woefully,

Must I then view you never again?’

‘That honour, if such you seek to gain,

You may win, but not soon, I deem.’

Her parting words flew off downstream.

Gawain encounters and defeats Duke Lischois Gwelljus

NOW Duke Lischois Gwelljus came.

If I were to say he flew, you’d blame

Me for it, yet his speed was such

His charger scarcely seemed to touch

The ground. ‘How then shall I receive

This knight?’ Gawain thought, ‘I believe,

If he comes at me full tilt, he’ll ride

O’er us, and down the other side;

His mount will stumble over mine,

Then if he offers to fight tis fine;

With both on foot, if that’s his wish

I’ll grant it, e’en though after this

The lady who would have me fight

Bestows not a smile on her knight.’

Naught could stop them now, for he

Who fast approached, in gallantry,

Was the match for he who waited;

To a long struggle they were fated.

Gawain prepared for his advance,

On the saddle he couched his lance,

And the two thrusts were so exact

The impact so great that, in the act,

Both lances shattered, and each man

Lay on his back; twas Gawain’s plan,

The man with the finer mount fell,

And he and Lord Gawain as well

Reclined a while amidst the flowers.

Yet soon both regained their powers.

What then? They leapt up sword in hand,

Both eager, and neither one unmanned.

There was no sparing of shields then,

Both were so carved by these men

That little above the grips remained,

(Shield are ever most sorely maimed)

And you could see the sparks rise

From their helms, to scorch their eyes.

Whichever God grants the victory

Must first cover himself in glory,

Yet count himself right fortunate.

They fought so long, in that state,

On that wide expanse of meadow,

And dealt so many a hefty blow,

Two strong blacksmiths would have tired.

Yet to renown they both aspired.

Though who shall praise the pair,

Fighting for no good reason there,

Other than that Fame might smile

Upon the winner, for a while?

Rash men, they had no great matter

To decide, no cause to flatter

Themselves for holding life so cheap;

Neither man had a grudge to keep,

Nor had committed any wrong.

Now Lord Gawain was skilled and strong

At pinning a man to the ground,

After throwing him, and had found

That if he blocked the other’s blade,

And grappled him, his foe was laid

Flat on his back, at Gawain’s will.

Forced to defend himself he still

Gave good account. Now he grasped

The brave young knight, and clasped

Him; though he too was fit and strong,

Turning, he threw the man headlong,

Then pinned him beneath his weight.

‘Surrender, knight, such is your fate

If you would live,’ Gawain now cried.

Lischois, lying beneath him, sighed,

Ill-prepared his pledge to render

Being unaccustomed to surrender.

Twas strange to him that any man

Should have the power to demand

What none had ever sought before,

Much like a badge the vanquished wore,

A sworn oath, such as he had wrung

From others before; his praises sung

For the many jousts that he had won.

Whate’er the outcome of this one,

Having forced many a surrender,

He was more than loth to render

His pledge, whatever fate might come,

He’d rather die than be the one

To swear an oath, under duress;

To treat with death would irk him less.

‘You are the victor now,’ he said,

And it were better I were dead

Than have my friends, by and by,

Learn that one, who flew so high,

Has been vanquished here. The lady

Was mine, and I had all the glory,

While God wished it so, your hand

Must my present death command.’

Gawain demanded his surrender,

But Lischois would not so render

Seeking swift death; then Gawain

Asked himself: ‘Why seek again

To kill the man? Would he obey

In all else, I’d free him this day.’

And he tried to gain agreement

To such terms, but Lischois, intent

On dying thus, would not concede.

Gawain, averse to such a deed,

Let him alone, and that was that;

There amidst the flowers they sat.

Now Gawain, still discontented

With that steed he so resented,

Thought, wisely, he might mount

Lischois’ own charger, on account,

And spur the horse, and trial it so.

Warlike it stood, steel-clad below

A second covering of brocade

And samite, so his way he made

Towards the steed; having won it

In this venture why not ride it?

He’d not known the horse as yet,

But saw now it was Gringuljete;

Urjans had gained it, through deceit,

Rendering his dishonour complete.

‘Tis you then, Gringuljete!’ he cried,

All set for a noble knight to ride,

Thus, God, who often ends our woe,

Of His grace, has returned you so.’

Dismounting, he saw that the steed

Bore the true Grail device, indeed,

A dove, branded on its shoulder.

Riding it Lahelin, proving bolder

And more skilled, had slain a knight

Of Prienlascors, and twas his right

To seize the creature, then the horse

Had come to Orilus in due course,

Who gifted it to Gawain that day,

By the Plimizoel, where Arthur lay.

Now his spirits that had sunk so low,

Oppressed by a dire state of woe,

(For his loyal devotion to his lady,

Had yielded for him but scorn lately,

Though his thoughts still pursued her)

They rose; proud Lischois however,

Ran now to where, upon the grass

Lay the sword that slipped his grasp

When Gawain threw him, and then,

Those watching saw them fight again.

Their shields were both in such a state,

They let them lie, and battled straight,

Each a brave-hearted, fighting man

Now met together, blade in hand.

Many a maid sat, at her window,

Watching the fight unfold below.

And now their fury blazed anew,

Each was of such lineage, too,

It would have irked him to bow

To the other’s greater valour now.

Their swords and helms suffered badly,

Scant shields against death, as madly

They toiled, and those who saw the fight

Would have judged both in sore plight.

Lischois Gwelljus fought like this:

His noble heart inspired the wish

For boldness, courageous action,

Many a swift sword-stroke; often

He leapt away, but then attacked;

Gawain sought, by his every act,

To clasp him close: ‘If I can see

A way to grasp you, I shall surely

Repay the debt in full,’ he thought,

‘A lesson now you will be taught.’

Sparks of fire their sword-arms brought

From the other’s armour, they sought

To manoeuvre, and yet why fight

At all? For all their toil they might

More fittingly let the matter rest.

My lord Gawain, grasping the chest

Of Lischois, threw him to the ground,

Beneath him (may I not be found

In such a loving embrace as he,

For it would prove the death of me!)

Gawain demanded his surrender,

Once again, yet he would not render

Himself, refusing as before.

‘You but waste your time, my lord,

I offer my life this day, instead,

Let my renown, and I, lie dead;

God has cursed me, who cares not

For all the glory a man has got.

For love of the Duchess Orgeluse,

Many a knight renown did lose,

Many a worthy man did yield

His fame to me, upon the field,

So that, by slaying me, that same

Renown will gather to your name.’

‘Truly, I must not,’ thought Gawain,

‘Were I to slay the man, then Fame

Would never again smile on me.

From love of her, he fought, and he

Was driven by that same torment

That pains me. I should rest content,

And let him live for her dear sake.

Is she’s to be mine, he can make

No move that will avert what fate

Bestows on me, and, at any rate,

If she has seen the battle we fought

She’ll credit me, as one who sought

To, thus, deserve her love. God knows,

I’ll spare you for her sake!’ He rose,

So Lischois could stand; in distress,

Both aware of their weariness,

They sat down once more, well apart,

Yet neither man seeking to depart.

He pays the master of the ferry, Plippalinot, his due

THE ferry now came to the shore,

Returning to where it lay before,

And the master of the ferry strode

Towards them; a grey merlin rode

On his fist. Each loser must yield,

When knights jousted on that field,

Payment to him of their fine steed,

While he would offer praise indeed

And honour the knight that had won,

And noise his fame abroad. So, one

Raised revenue from that meadow,

And many a steed he had to show,

Equalled only when his fair hawk

Swooped upon some crested lark.

He had no other income, but he

Was well content with his fiefdom. He

Came of high and knightly descent

And his breeding proved excellent.

He went to Gawain and, courteously,

Asked of him the appointed fee.

‘I sell not in the market-place, so,

Good sir, you may spare me your toll.

Said Gawain: ‘My lord,’ he replied,

My lawful due shall not be denied,

For many a lady saw you conquer;

You must concede it, as the victor.

You won the steed, and great renown,

When you thrust him to the ground

Who ruled supreme till this fair day.

Your victory, sweeping him away,

Has robbed the man of happiness,

While your good fortune is no less;

It fell like a blow from on high,

On him; you benefit thereby.’

‘He unhorsed me,’ replied Gawain,

‘Though I exacted payment again.

If a jousting tax is paid to you,

Then let him pay whate’er is due.

The little steed he won in battle

Take that from the knight if you will;

But mine shall be the better horse,

Destined to bear me, in due course.

You speak of what’s owed; yet you

Owe it to me not to part from you

On foot. I’d be sorry and you also,

If, lacking a horse, you saw me go.

You’d regret it, if it were known,

For this morn, it was still my own,

Beyond all doubt. If you would ride,

Mount a hobby and strut with pride.

Twas Orilus of Burgundy

Who gifted this creature to me,

But Urjans of Punturteis,

Took the horse, and made it his

For a while. Take what he stole?

Sonner get you a she-mule’s foal!

But I can still grant you a favour,

Since you do the knight full honour,

Instead of the war-horse, feel free

To take the man who rode at me,

Whether he likes the fact or no.’

The ferryman true joy did show:

‘I’ve ne’er known so rich a gift,’

He cried, with laughter on his lips,

‘If it were proper to receive it.

Yet sir, if you will guarantee it,

It far exceeds my own request.

Now, for a warrior of the best,

Five hundred steeds were fair trade,

If in such coin one might be paid.

If you’d have me rich, indeed,

I’d call it a right handsome deed,

If, like a true knight, you would,

Into my boat, upon the flood,

Deliver the man. ‘I shall do so,’

Said Gawain, ‘and he shall go,

As your prisoner now, on board,

And off again, be thus assured,

Until he stands before your door.’

‘You’ll be welcome all the more,’

Cried the ferryman, bowing low,

In gratitude, ‘and let me show

You honour, come spend the night

In my humble house, sir knight,

Find comfort there, no greater

Honour befell my peers ever,

Those that ply the ferry I mean;

It would be well if I were seen

To entertain such a nobleman.’

‘I would welcome so kind a plan,

Being overcome by weariness,

The which dictates that I should rest.

She who commands me, tis her manner

To turn whate’er is sweet to bitter,

To make the heart poor in delight,

But rich in cares; such is her right,

Yet tis no fair reward. Alas,

Loss, that at first sight came to pass,

You weigh upon the breast, I fear,

That rises free when joys appear,

While the heart that lay beneath

Has vanished. I endure this grief

Without her aid, where shall I find

That which might relieve my mind?

If she were a true-hearted woman,

Would not she, whose powers can

Wound me so, bring happiness?’

Hearing that love did so oppress

Gawain, seeing him struggle so

With love’s cares: ‘Such here below

Is e’er the rule, amidst the meadow

And the woods, concerning sorrow:

Sad today, and glad tomorrow,’

Said the ferryman, ‘everywhere

Where Clinschor’s lord. Your weight of care,

Not cowardice nor bravery

Can alter one iota, you see.

You may not be aware, but all

That in this country doth befall

Is marvellous, you understand,

Tis a great wonder this whole land,

And its magic holds night and day.

If a man is brave, then fortune may

Aid him here. But the sun is low,

And on board you both should go.’

The ferryman urged them so to do.

Gawain led Lischois, and the two

Boarded the ferry, the prisoner

Patiently, and without demur,

While the ferryman led the steed,

And once it was secured, indeed

The ferryman delayed no more.

Thus, they crossed to the other shore.

Gawain is a guest of Plippalinot, and meets his daughter Lady Bene

‘NOW in my house come play the host,’

The master said. Arthur could boast

No finer dwelling at Nantes indeed

Where he oft stayed. Gawain did lead

Lischois within, while the master

And his household did him honour.

‘See to the needs of this great lord,

And every comfort do him afford,’

The master said to his daughter,

‘He grants us much; go together.’

While she saw that this was done,

Gringuljete was housed by his son.

She did as bidden, most courteously,

And Gawain followed her as she

Led him to an upper chamber

Whose floor was strewn all over

With fresh rushes and bright flowers,

Companions of our happier hours.

The sweet girl unarmed him there.

‘May God reward you, for your care,

Said Gawain, ‘I am shamed, madam,

For were it not so decreed, I am

The object of too much attention.’

‘I wait on you for no other reason

Than your good favour, sir,’ she said.

The master’s son, a squire, well-bred,

With bolsters and cushions appeared.

Away from the door, a space he cleared,

Arranged them neatly, by the wall,

And laid a carpet before them all,

Where Gawain might sit, then spread

A red sendal coverlet o’er the bed,

And prepared a couch for his host.

Then a second squire who did boast

Fine table-linen, wine, and bread,

Entered the chamber in his stead,

And laid the table, as bidden him.

Next, the lady of the house came in,

Who warmly welcomed Lord Gawain:

‘We who were poor are rich again,

And Fortune smiles on us,’ she said.

His host entered; ere Gawain fed,

A squire a basin of water brought,

He washed his hands, as his host sought

To ensure all fitting for his guest.

And now Gawain made a request,

And asked his host for company:

‘Let this young lady dine with me.’

‘She never dined with lords before,

Or sat beside them, what is more,

For fear she’d run to pride’s excess,

Yet this is but one more kindness,

You have done us; daughter, I say,

Do as my lord doth wish, I pray.’

The girl, Bene, blushed, and again

Obeying, sat down beside Gawain.

The host’s two fine sons now brought

Crested larks his merlin had caught

On the wing; they served all three

To their guest, with a sauce, while she

Cut tasty morsels for Lord Gawain,

And on the good white bread was fain

To lay them, with her own fair hand,

For fine manners she did command.

‘Sir, of these birds, pray you, grant one

To my mother for she has none.’

He told her he would do her wish

In aught she might ask, as in this,

And so a lark was served promptly

To the lady of the house, and she

Acknowledged the gift with a bow,

While the host his thanks did avow.

Then one of the sons, to their guest,

Brought lettuce and purslane dressed

With vinegar (such a diet extended

For too long is scarce recommended

As the best way to give one strength

Or colour, yet what’s won at length

From what one eats e’er speaks true,

While, all too often, a lady’s hue

Is laid on o’er the skin these days;

Yet ne’er has won resounding praise.

I think the woman of constant heart

Bears a finer glow than that of art.)

Had Gawain fed on goodwill alone,

He’d have thriven well there, I own,

For no fond mother has ever wished

Her child more joy than his host wished

The guest who now did eat his bread.

And, once my Lord Gawain had fed,

And the host’s wife left the chamber

A bed of soft down, with a cover

Woven of green samite, was brought;

Though twas not one of the better sort.

A quilt then, of brocade, was spread

For Gawain’s comfort, o’er the bed,

Brocade without the thread of gold

Brought from heathen lands of old,

Quilted o’er ‘palmat’ silk, o’er this

Soft sheets of snowy linen, for his

Greater ease, were drawn; on them laid

Pillows, and a cloak, of ermine made,

Such as a young lady might wear.

The lord of the ferry left him there,

And went to his bed. Thus, tis said,

The girl was now host in his stead.

I think did he wish aught from her,

With his request she would concur,

But he needs to sleep, as best he can;

When daylight dawns, God aid the man!

End of Book X of Parzival