Wolfram von Eschenbach

Parzival

Book III: The Young Parzival

‘Honour's Prize’

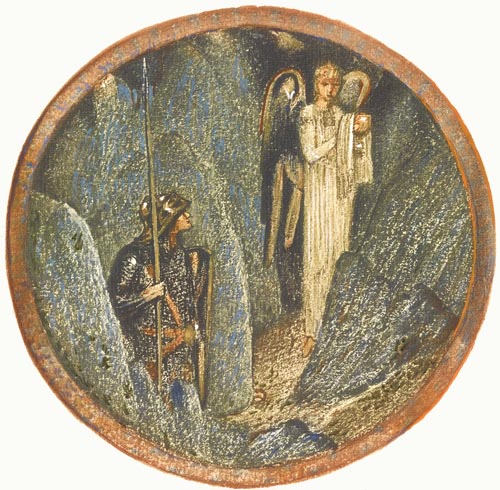

From The Flower Book, Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833 – 1898)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Parzival’s upbringing.

- He meets a band of knights.

- Parzival tells his mother of the knights.

- The death of Herzeloyde.

- Parzival sets out, and comes upon a pavilion.

- He kisses the Lady Jeschute and takes her ring.

- Duke Orilus de Lalander scolds his wife.

- Parzival finds his cousin Sigune with a dead knight in her lap.

- She tells him his true name, and of the dead knight, SchionatulandeR.

- Parzival lodges with a churlish fisherman.

- He and the fisherman ride to Arthur’s court at Nantes.

- Parzival encounters the Red Knight, Ither of Gaheviez.

- Parzival is brought before King Arthur.

- Sir Kay strikes the Lady Cunneware.

- Antanor predicts that the lady will be avenged by Parzival.

- Parzival slays Ither, the Red Knight, and takes his armour.

- Iwanet aids and advises Parzival with regard to the armour.

- The mourning for Ither.

- Parzival comes upon the castle of Gurnemanz de Graharz.

- Gurnemanz trains Parzival in the arts of chivalry.

- Parzival takes leave of Gurnemanz.

Parzival’s upbringing

IT saddens me that all women bear

That same name of Woman; all fair,

And all owning the same clear voice.

Yet some do in pure deceit rejoice,

While others of such are wholly free.

Two faces you have it seems to me.

To my heart’s depth the pain doth strike,

That all you women are named alike.

For if to yourself you are ever true,

Then, Woman, faithfulness and you

Will ever remain the best of friends,

Bound together whate’er fate sends.

Many will say that poverty

Brings us naught but misery,

Yet for loyalty’s sake to endure

Such a thing doth ever ensure

That the soul doth escape hellfire.

Here was one who amidst the choir

In heaven found her true reward,

The infinite gift it doth afford

Faithfulness, despite poverty.

I doubt today there are many

Who in their youth would thus forgo

Earthly riches that they might know

Heavenly glory hereafter.

I know none, and I’d go farther,

For men and women in my view

Would, one and all, shirk it; and do.

Lady Herzeloyde, though possessed

Of riches, renounced, none the less,

Her three kingdoms, sought poverty,

Burdened by care, while all falsity

Was so absent from heart and face,

Nor eye nor ear could find a trace.

The sun was clouded to her sight,

She shunned all worldly delight.

To her the day and night were one,

Her heart was e’er to sorrow won.

Possessed by grief, she now withdrew

From all she had, and all she knew,

Among the wild wastes of Soltane

She lived, and not the flowery plain;

Bright garlands brought her no delight,

Nor those less pleasing to the sight,

So deep the sorrow in her heart.

And she bore to that place apart,

The son of her lord Gahmuret,

So he might find a refuge yet;

And there her folk cleared, all around,

A space to cultivate the ground.

How she sought to protect her son

Ere to maturity he had come!

She forbade her people, every man,

On pain of death, and every woman,

Ever to breathe the name of knight:

‘For if ever my heart’s delight,

Should come to learn of chivalry,

A burden it would prove to me.

So take care that he never learns

Of knighthood, and the pain it earns.’

There things took their narrow course.

Buried away from the world, perforce,

The lad was reared in Soltane’s waste,

Of the royal life had ne’er a taste,

Made bow and arrows with his own hand,

And hunted the birds about that land;

Though when he had shot one dead,

That had been singing loud, instead

Of rejoicing, the lad would weep,

And grasp his hair and then wreak

Vengeance on his own foolish head.

Proud and handsome, there he led

A simple life; he washed each morn

In a stream in the meadow, at dawn,

And naught in all the world did prove

A care to him but the birds above,

Whose sweet singing pierced his heart,

Troubling his breathing with their art.

Then all in tears he’d run to the Queen.

‘What vexes you, what have you seen

In the meadow there?’ she would ask,

Lifting her eyes from some small task,

But he could find ne’er a word to say,

As oft happens with some child today.

She thought about this many a time.

One day she saw his clear gaze climb

To where the birds sang on high,

And found in them the reason why

His heart was moved. In this the boy

Was victim of that amorous joy

To which his race was heir, and she

Now turned on them her enmity,

Ordering ploughmen and drovers

To hasten and remove the singers.

But still the birds escaped in flight

In numbers sufficient to delight

The world still with their sweet song.

‘Why do they do the birds such wrong?’

The little lad asked of his mother,

And begged a truce for wing and feather.

The Queen kissed him; their lips met:

‘Oh, why, she said, ‘must I forget

And thwart the will of God on high?

Must the birds mourn with such as I?’

‘Who is this God now?’ asked the boy.

‘My son, I’ll tell you, without alloy;

He shines more brightly than the sun,

He who our human shape once won.

My son, do this wise saying heed,

Pray to Him in your hour of need,

His steadfast love shall never fail.

Let not the lord of Hell prevail.

He’s black and full of treachery.

Scorn him, for he brings misery.’

Then she told him of dark and light,

And how each differs to our sight.

And so the lad dashed off to play,

And through the forest made his way.

He’d learned to throw the javelin,

And slay the deer, lurking within;

Of these his mother had benefit.

In snow and thaw he practised it,

And wrought havoc on the quarry.

List to the wonders of my story!

When he had felled a stag so heavy

It would have burdened a pack-pony,

He bore it home, at a steady pace,

Unquartered, to his mother’s place.

He meets a band of knights

ONE day while hunting the hill-slopes,

He’d broken off a twig, in hopes

Of sounding a decoy-call, when he,

Heard echoing hoofbeats swiftly

Passing along the trail nearby.

He raised his javelin to his eye.

‘What’s this I hear now? If only

It is the Devil come upon me,

In all his fierce and dreadful power,

Then I might do for him, this hour.

My mother tells awful tales of him,

Though she trembles in every limb.’

He stood there, ready for a fight.

Behold, there came a splendid knight,

With two companions; three as fine

As you could wish, in single line,

All fully armed from crown to heel,

And each a god; the boy did kneel,

It must be so: ‘God aid me!’ his cry,

Rang out, ‘Your help you’ll not deny!’

The leading knight lost his temper:

‘This stupid Welshman,’ he cried in anger,

‘Blocks our way!’ Now the men of Wales,

I tell you, born of its hills and vales,

Are much like us Bavarians,

That others deem barbarians;

Though twice as dense again in fact.

Yet he becomes a marvel of tact

And courtesy, and a warrior born,

That in either land first sees the morn.

Now a fourth fair knight did appear

Handsomely clad in finest gear,

And he was riding in hot pursuit

Of others far ahead on his route,

A pair of knights who had lately

Borne away a fair young lady;

For he thought this a great disgrace,

One that brought shame on all his race,

And he was angered by the wrong

Done to her, so he galloped along,

To seek them; and the other three

Were his men, of his own country.

He rode a fine Castalian steed,

Ever a proud and handsome breed,

His shield dented by many a lance;

His name it was Karnahkarnanz,

Count of Ulterlec. ‘Who,’ he cried,

Blocks the way?’ then the boy he spied.

To the lad, a god this knight did seem,

Never saw he such brightness gleam

From anything. The knight’s tabard

But brushed the dew it left unmarred;

His neat stirrups rang with the sound

Of tiny bells there, on each leg found

At its front, they were made of gold.

And his right arm too, which did hold

The same, made music when he swung

A sword, and jingled where they hung,

For he was ever in search of fame.

Splendour then this knight did claim,

On a steed richly caparisoned.

‘And have you seen two knights, my son?’

Asked Karnahkarnanz, courteously,

He the flower of manly beauty,

‘Scant chivalry have they displayed,

Ravishers, who have here essayed

To carry away a girl by force.

Devoid of honour is such a course.’

But, barely listening to what he said,

The lad saw him as God, instead

Of just a knight, whom Herzeloyde

Had spoken about, when employed

On telling him of dark and light.

‘Help me, kind God!’ at the sight

Of him, the lad cried, earnestly,

And then he went down on one knee,

And began to pray.’ ‘God I am not,’

The Count replied, ‘yet fair my lot

On earth, and I do God’s will gladly.

And if your eyes saw not so badly

You’d but see four knights before you.’

‘Knights, you say, what do they do?

If you are not God then tell me now

Who grants this knighthood and how?’

‘King Arthur dubs a man a knight.

Were you, my boy, to seek aright,

And come into his court, none need

Blush for the knight you’d make, indeed,

I deem you of noble lineage.’

The knights in their bright equipage

Looked him up and down, and thought

That God in truth the lad had wrought.

And that I learn too from my source

Who tells me no one in the course

Of the centuries, since Adam’s day,

Was e’er more handsome in his way,

And women praised him far and wide.

There came more laughter on their side,

For the lad said: ‘What can you be?

Sir God, for look, here are many

Little rings tied fast to your gear,

All down there, see, and all up here.’

And the lad tugged at the ironware,

Saying: ‘My mother’s maids do bear

Rings on ribbons, on my honour,’

As he gazed at the Count’s armour,

‘But theirs are not so closely set,

And what is this coat gleaming yet,

That makes you look so neat and trim,’

For so he asked the Count, on whim,

‘While scarce a seam doth it afford?’

The Count he showed the lad his sword,

Saying: ‘If a man attacks me

I must fight with him most fiercely,

Thus, to defend myself, I wear

This armour, fitting it with care.

Tis good against lance-thrusts you see

And stops the arrows fired at me.’

‘Well, if the deer had hides made so,

The boy replied, ‘my every throw

Would never wound a single one,

Which my javelin has often done.’

The knights grew angry that their lord

Stood talking so, with this fool abroad.

But the Count cried: ‘God protect you!

And I would I had your good looks too.

If you’d but a modicum of wit,

God would have left you not a whit

More to wish for. May His power

Guard you now, and at every hour!’

The Count and his men parting made,

And rode to a field by a forest glade.

There that courteous knight did slow,

Finding fair folk much to their woe,

Labouring there, the Queen’s farmhands,

Ploughmen and such, for her commands

Had set them to furrowing; they sowed,

And harrowed, and worked the goad

Over the hides of the ox-teams there.

The Count asked them how they did fare,

And whether they’d seen two knight pass by,

With a woeful damsel, their reply

Was: ‘Two knights and a young lady

Rode by this morn, and we could see

The lady was sad and filled with fear.

They spurred hard and galloped clear.’

Now one of these was Meljahkanz,

Whom this Count Karnahkarnanz

Sought to catch and then by force

Win back the lady in due course,

For she till then would be in woe

And anguish, this the knight did know,

And then this lovely lady’s name

It was Imane de Beaufontane.

Now as the knights away did fare,

They left the ploughmen in despair:

‘How did we come to do this thing?

They cried, ‘for these men are wearing

Battle-scarred helmets, and further

They were seen by our young master,

And so our trust we have betrayed.

With harsh words we’ll be repaid

By the Queen, and it serves us right,

For he came with us, at first light,

While the Queen was still asleep.’

Parzival tells his mother of the knights

AND sure enough the lad was deep

In thought, and had forgot the chase,

But went to seek his mother’s place,

And told a tale that sent her reeling,

With such a shock to her feelings,

She fell at his feet, in a swoon.

She regained her senses full soon,

Though her spirit had failed at first,

And asked: ‘My son who rehearsed

This tale of the code of chivalry?

Who told you such a thing might be?’

‘Mother, I met four, each a knight,

Shining like God, and yet more bright,

And one he told me of chivalry,

And how so fine a thing might be.

It lies in Arthur’s royal power

To guide me to honour, that hour,

And the fair office of the shield,

When by his hand my fate is sealed.’

It added to that woe of the Queen’s.

She cast about to find some means

Of persuading him from his intent.

On gaining a mount he seemed bent.

‘I’ll not deny him.’ Though her heart

Regretted it; since they must part:

‘Yet it shall be the worst I know,

And he shall wear fool’s clothes also,

O’er his white skin, and then if he

Is scorned he will return to me.’

And, oh, for the pity of the thing!

She took a piece of coarse sacking,

Cut him trousers and a doublet

All of a piece, the strangest yet,

Neck to knee, twas a fool’s garment,

With a cowl as its complement.

And then did she, from raw calf-hide,

Cut a pair of boots, shaped to hide

His white legs, and all this was done

In tears, lamenting o’er her son.

She asked him to stay one more night:

She said: ‘You shall not leave my sight

Till I have taught you a little sense.

Now then, when you go riding hence,

Avoid the fords with murky water,

But go briskly where they’re clearer.

Greet those that you meet, one and all,

And if it should chance to befall

That you meet a wise grey-haired man,

Who offers to teach you, as he can,

Fine manners, then do as he says,

Willingly; keep from anger always;

And I give you this advice, my son,

If a lady’s ring’s there to be won,

And her welcome, take it from her,

Dawdle not, embrace and kiss her,

It will add much to your content,

And bring good fortune if her intent

Is good, and she be chaste; learn this,

Lahelin the proud has taken as his

Two of our lands, Wales and Norgals,

From our vassals, while Turgentals,

One of those brave lords, he has slain.

Your rights then you must maintain.

Lahelin killed your kith and kin,

Or took them captive, think on him.’

‘I will avenge it, mother, I vow;

I shall wound him, if God allow.’

The death of Herzeloyde

WHEN the sun shone bright at dawn,

The lad rose swiftly with the morn,

Eager to search for Arthur’s court.

The Queen kissed him, all distraught

Ran after him and (the saddest thing)

When she could no longer see him,

(Who feels not the pain she found?)

That loyal lady fell to the ground,

Where sorrow dealt her such a blow

That death came to her, in her woe.

Her loyalty from hellfire saved her,

O happy woman, faithful mother!

Thus from true virtue’s root we see

Rose that stem of humility

To seek the path that brings souls gain,

Ah, that her scions no more remain

To the eleventh generation;

For lack of them, woe to our nation!

Yet all true-hearted women should

Bless the lad, and pray for his good,

As he goes forth, and leaves her there.

Parzival sets out, and comes upon a pavilion

NOW hear more of this whole affair.

In a while, our handsome young man

Approached the Forest of Brizljan,

And came to a stream where if it please

A cockerel can cross with ease.

Though twas only grass and flowers

That darkened the ford’s pure waters,

Our hero shunned them, rode away,

And went following the stream all day.

He spent the night as best he could,

Till the bright sun cleared the wood,

Then, all alone, discovered a ford

That him clear passage would afford.

Upon the far bank, in a meadow,

Stood a pavilion, and it did glow

With bright samite, in three colours,

Worth a fortune, midst the flowers.

It was tall, and spacious within,

And then gold braid its seams did trim.

A leather cover too hung there,

Employed whene’er rain filled the air.

Duke Orilus de Lalander –

Twas his wife reclined thereunder,

The fair Duchess, a noble sight,

The sweetest mistress for a knight;

And fair Jeschute that was her name.

The lady was asleep; that same

Wore Love’s emblem, a sweet mouth

Of gleaming red, to quench the drouth

Of amorous knight and aching heart.

Her lips, at rest, did slightly part,

That wore the flames of Love’s hot fire,

Thus there she lay, the sweet desire

Of any man who ventured by.

Her perfect gleaming teeth did lie

In rows of snow-white ivory.

(Naught could ere accustom me

To kissing of a mouth so praised,

For no such thing ere came my way!)

The sable coverlet reached barely

To her hips; her lord had scarcely

Left her, ere she had felt the heat,

And pushed it down, her hips to meet.

Her figure it was trim and neat,

No art was lacking there, twas meet,

Her sweet form God himself had wrought.

And if this beauty’s arms you sought

They were slender, and white of hand.

Now on one finger of her right hand

He spied a ring, which drew him on,

Toward the couch, and thereupon

He began to struggle with the lady;

He’d thought of his mother, how she

Would have him take a woman’s ring,

And so he’d sought that very thing,

And leapt to the couch from the floor.

The modest woman, shocked, I’m sure,

Found a handsome lad in her arms;

How to sleep through such alarms?

He kisses the Lady Jeschute and takes her ring

‘WHO is this does me such dishonour?’

The lady cried, in shame and anger,

‘A lady tis you seek to smother;

Address yourself to someone other!’

She seemed grieved but, ignoring this,

The young lad forced her mouth to his.

While he crushed her breast to breast,

Of her ring she was dispossessed.

Then a brooch on her shift he saw,

And, from it, this he roughly tore.

All women’s wiles were the lady’s,

But his strength was as an army’s.

Nonetheless she fought the fight.

The winner now complained outright,

Of raging hunger: ‘Don’t dine on me,

Choose other fare for there is plenty,’

Cried the fair one, ‘there’s good bread,

And wine, and partridges instead;

The maid left them, though not for you.’

Little he cared; she reclined anew;

He filled his belly and drank the wine,

While she thought him a tedious swine,

Some page perchance who’d lost his wits;

The shame nigh had the girl in fits.

‘Young man you must return my ring,

And my brooch, for the hour will bring

My husband, and you’ll feel such anger

As you’d be spared; scorn to linger.’

Why should I fear your husband so?’

The lad replied, ‘and yet I will go,

If it harms your honour in some way,

And to the couch he made his way

And then another kiss was taken

Though, unless I’m much mistaken,

It gave the lady great annoy.

Then, without leave, the foolish boy

Rode off, though he cried: ‘God bless you!

That’s what my mother said to do.’

Duke Orilus de Lalander scolds his wife

THE lad was happy with all he’d won,

And all that he had said and done.

When he’d ridden on, a little while,

(In truth he’d gone nigh on a mile)

Her lord appeared, of whom I’ll tell.

From the tracks he knew full well

(Some of the ropes were slack, alas,

Where the lad had trampled the grass)

That someone had sought his lady;

Count Orilus found her, utterly

Wretched, standing there within.

‘Ah, madam,’ thus he did begin,

‘Is it for this I gave my service?

Shall my fair deeds but end in this,

Sad disgrace? You love another!’

The lady swore she loved no other,

And claimed that she was innocent;

He feigned to know not what she meant.

‘A madman rode this way,’ she sighed,

‘A fool, but handsome, and did abide,

And then he stole my brooch and ring.’

‘Oh, you liked him, and did the thing

With the fellow!’ ‘Nay, God forbid!

Twas against my will, all he did;

His boots and javelin I did fear,

Both of them came far too near;

You but shame me to say twas so!

To love such a lout were but low.’

‘Madam, scant wrong I do to you,’

Replied the Count, ‘except tis true

That for my sake, to your distress,

Your title is now that of countess,

Not queen; but there I’m the loser;

My skill is such that your brother,

Erec son of King Lac, has cause

To hate you for it; the applause

I win from all those who can judge

Proves tis so, though he did budge

Me from my seat before Prurin.

Yet o’er his crupper I drove him,

And won the glory at Karnant;

For a straight lance I there did plant

On him, and I drove your favour

Clean through both shield, and armour;

While your brother did surrender.

But that you’d found another lover,

My lady Jeschute, I’d have you know,

Little did I dream that might be so.

Come, credit me for another win;

Galoes, the son of King Gandin,

Him I slew with a thrust of mine.

Nor were you far away that time,

When Plihopliheri did advance

Against me there to break a lance,

And pressed me hard, and yet he went

Over his crupper in brief descent,

His saddle no more troubled him.

Many an honour I did win,

Full many a knight I laid low;

Yet sad disgrace I now must know;

I have failed thus to reap the fruit.

They all hate me, beyond dispute,

All those men of the Round Table,

Eight of whom I did disable

At Kanedic, before a crowd

Of young ladies, who cried aloud,

To see it; of all I was the talk,

When I fought for the sparrow-hawk,

And gained it for you, my lady,

And for myself the victory.

King Arthur watched me, at your side,

With whom my sister doth reside,

Sweet Cunneware, who’ll not wear

A smile until she sets eyes there

Upon the finest knight on earth,

The man of most illustrious worth.

If only he might come my way!

There would be fine sport this day,

Like this morning’s, when I fought

A prince, who challenged me and sought

To unhorse me. He fell instead;

A single lance-thrust saw him dead.

I’ll not speak my anger; for less

Men strike their wives; I seek redress,

And if of right or favour there’s aught

I owe you, let it still be sought,

I’ll warm to your embrace no more,

Those white arms where I lay before,

On many a pleasant day gone by.

I’ll teach your lips to fade, next I

Will teach your eyes your lips’ redness.

I’ll steal from you all happiness,

And so I’ll school your heart in sighs.’

The Countess gazed with piteous eyes

And mouth: ‘Oh, treat me with honour,

Chivalrously, for you are ever

True and wise; I’m in your power,

And you can deal me woe this hour,

But listen first to my defence,

For I’ve committed no offence.

I beg you in the name of woman;

Punish me then, though if some man

Were to kill me now, and so spare

You from shame, I should not care

How death came, for it would be sweet

Now your hatred proves so complete.’

Then the Count said: ‘Lady, you grow

Too proud, but that you shall forego.

An end to our eating and drinking

Together, and as for our sharing

One bed, that is over and done!

Regarding clothes you shall have none

But those that you now are wearing.

Your palfrey will not be dining;

A twist of lime-bark its bridle,

And this for your pretty saddle!’

He tore the rich brocade away,

And all her good saddle did flay.

Modest, loyal, she bore his spite,

And then must suffer the delight

Of a saddle with lime-bark retied;

His sudden rage she must abide.

‘Now, madam, let us ride,’ he said,

‘How pleasant if our journey led

To him who enjoyed your favours!

I’d try my fate, though he labours

Hero-like, or breathes fire upon

My face, raging like a dragon.’

Far from pleasure, drowned in tears,

The lady set forth, hedged by fears,

Not thinking of what she endured,

But of the sufferings of her lord;

His wretchedness was her distress,

And death to her a true kindness.

Her loyal love deserves your pity,

Since she’ll now feel his enmity.

Though I were hated by the sex,

Though each one my heart did vex,

I could not fail to be irate

At Lady Jeschute’s bitter fate.

Thus they rode, following his trail,

While on ahead the lad did sail,

Not knowing they came on behind.

For indeed, he passed the time,

Greeting all those he chanced to see,

Adding: ‘So mother asked of me.’

Parzival finds his cousin Sigune with a dead knight in her lap

OUR simple lad was riding down

A trail traversing sloping ground,

When a woman’s voice he heard.

Below a cliff; with sorrowful word

A lady mourned lost happiness.

The lad was moved by her distress,

And rode towards her in some haste.

Hear, now! Twas Sigune in that place

Who sat there weeping with despair,

And tearing at her long brown hair.

Now the lad gazed down upon her,

And lo, Prince Schionatulander

Lay dead there, in her lap, and so

Her thoughts were but of endless woe.

‘Sad or joyful, not to forget

To greet all folk, all that I met,

So said my mother: God keep you,’

Said the boy, ‘tis a grief to view

That sad thing lying in your lap,

How have you come by this mishap?’

Unabashed, he asked: ‘Who slew him?

Was it with some sharp javelin?

It seems to me that he is dead.

If whoe’er faced him lies ahead,

I will willingly catch the man,

And fight and kill him, if I can.’

And the lad clutched at his quiver

Of javelins, all set to deliver

Some lasting blow. Had he yet known

His father’s practise which, I own,

Once learnt, stayed with him forever,

The thought would have played far better

Back where he had found the Duchess,

Who thanks to him knew great distress;

For he still had the brooch and ring

He’d taken from Jeschute, causing

Her spouse to scorn her for a year

Or more. She was much wronged I fear.

She tells him his true name, and of the dead knight, Schionatulander

NOW hear of Sigune. She did express,

With sad looks, her unhappiness.

‘You seem fair,’ she said, ‘all honour

To sweet Youth that doth you favour!

For I feel sure that some fine day

Good fortune will bless your way;

It was no javelin slew this knight,

He lost his life in noble fight.

You too must come of nobility,

If you feel pity for him you see.’

Ere she allowed him to ride on,

She asked his name, for he was one,

She said, whose features, as a man,

Seemed as if wrought by God’s own hand.

‘Bon fîz, cher fîz, bêâ fîz,’

Such, in mother’s house, they called me.’

Now, from these words, she knew his name.

Hear him addressed by that true name,

(For he’s the hero of our tale)

As he stands there with her, in the dale.

‘Upon my word, you are Parzival!’

She of the red lips cried: ‘Withal,

You shall “pierce to true worth,” indeed,

Through many a great and noble deed.

Mighty love pierced such a furrow

Through your mother’s heart, for sorrow

Your father left her when he died.

Tis not idly I speak.’ She sighed:

‘Your mother is my mother’s sister,

I’ll tell you who you are; your father

Was an Angevin, but Welsh are you

On your mother’s side, for I tell you,

At Kanvoleis you were born,

And know, for tis true as the morn,

That you are King of Norgals too,

And at Kingrivals should wear the crown,

In that city of high renown.

This prince, his loyalty unmarred,

He died for you, while he did guard

Your lands as he has ever done.

My sweet young and charming one,

Two brothers have done you great wrong.

Lahelin who stole your kingdom;

The other Orilus, who slew

This knight with Galoes your uncle too,

And thus drowned me in misery.

This prince of your own fair country

Gave to me his service freely,

While your mother fostered me.

Good kind cousin let me tell how

His death came about, for I vow

A bitch-hound’s leash led to the fight,

Earning a swift death for the knight,

Which he won in service to us two,

And bringing me such grief anew,

So great the love for him I bore.

I know not the reason, I’m sure,

Why I denied him true content.

For, in thus refusing my assent,

It must become the source of woe;

Dire misery from this did flow,

And now but a dead man I love.’

‘Cousin,’ said he, ‘your sufferings prove

A grief to me, and shame me greatly,

If ever I may avenge you, truly,

I’ll settle accounts with Orilus.’

He was full eager to battle thus,

But she pointed the opposite way,

Lest he too might be slain that day,

And she meet harm at Orilus’ hand.

Parzival lodges with a churlish fisherman

HE took the broad, paved road that ran

To Arthur’s court, and catching sight,

Of any man, merchant or knight,

Waking or riding, he would greet

Them with a speech, fair and sweet,

Saying his mother had so advised;

Nor had she erred; for such was wise.

As evening fell, he grew weary,

A fair house he came to shortly;

Within a churlish host was found,

The sad kind that do still abound,

A fisherman devoid of grace.

The hungry lad approached the place,

And told the fellow of his hunger.

‘Not a loaf you’ll win,’ said the master,

‘In thirty years, for, if any man

Thinks to see me with open hand,

He seeks in vain, tis all for naught.

I feed myself on what I’ve caught;

Next my children; you’ll not enter

If you wait all day crying hunger.

Yet if you’d aught of worth to pawn,

I might relent yet, come the dawn.’

The simple lad did then approach,

Offering Lady Jeschute’s brooch,

And when the churl saw the thing

His face, of a sudden, wore a grin.

‘Dear child’, he said, ‘come stay with me,

All shall treat you respectfully.’

‘If you do feed me well tonight

And on the morrow set me right

As to the road to Arthur’s court,

Whom I love, the gold you sought

Is yours.’ ‘I will,’ the churl replied,

‘So fine a lad I ne’er espied.

I’ll show you the King’s Round Table,

And see what comes; for tis no fable.’

He and the fisherman ride to Arthur’s court at Nantes

THE lad stayed the night; next morn,

For he could scarce await the dawn,

They were gone, for the fisherman

Ran on ahead, you must understand,

While the lad followed on his steed,

And both seemed in a hurry indeed.

(Now, my lord Hartmann von Aue,

I send you a stranger, this hour,

To greet your lord and lady, here,

King Arthur and Queen Guinevere.

Kindly shield him from mockery.

For he’s no fiddle or rote you see,

To be strummed upon, let the folk

Find some other butt for a joke,

Otherwise your Lady Enide,

And her dear mother Karsnafide

Will find their reputation gone,

When all my tale is said and done;

If I, to such jibes, an ear must lend,

I must seek to defend my friend.)

The noble lad and the fisherman

Came to Nantes, as was their plan;

Near that city, ‘God be with you,’

Cried the latter, ‘Now, in plain view,

Lies the gate where you may enter.’

Said the lad: ‘Guide me no further.’

‘Nor will I! There they are so fine

They shun a common face like mine.’

Parzival encounters the Red Knight, Ither of Gaheviez

THE boy rode on, and soon had sight

Of a great meadow, its flowers bright.

Now, he knew naught of fine manners

(No Curvenal, fair Tristan’s tutor,

Had sought to raise this home-bred lad)

A twisted lime-bark bridle had

His little palfrey, that was pleased

To stumble, and fall to its knees,

Full oft. No patch of fresh leather

Had adorned its saddle ever.

As to fair ermine or samite,

Not a trace of it was in sight;

No need of silk cords for his cloak

In the manner of gentle folk;

Instead of a tabard and surcoat,

He had his javelin, we note.

Alas, his father King Gahmuret

Whose elegance none can forget,

Was so much better dressed when he

Showed himself at Kanvoleis!

Riding towards the lad there came

One whom he greeted in the same

Way as ever with: ‘God keep you!

For this my mother told me to do.’

‘God reward her and you, my lad!’

Said the knight. Now this lord, who had

Been reared by Uther Pendragon,

Was Arthur’s paternal aunt’s son,

And to Britain he now laid claim,

As his heritage. The knight’s name

Was Ither of Gaheviez, otherwise

The Red Knight; twas no surprise,

Since his gear was of such a red

It reddened the eyes in one’s head.

His warhorse was a sorrel steed,

Its head-plates crimson, as indeed

Were its trappings, of red samite;

A crimson shield he bore, this knight,

And his sword was red, his choice,

With hardened edges; he did rejoice,

This noble King of Cumberland,

At the goblet he clasped in his hand,

Seized from the Round Table there,

For of red gold was that brave affair.

His skin was white, his hair was red,

He turned towards the lad, and said:

‘A blessing on your handsome face!

A fine woman, of noble race

Brought you into the world, my lad.

I’ve ne’er seen another who had

So fine a form, and you possess

Love’s very glance, her success

And her defeat, for joy entire

In many a woman you’ll inspire,

Yet grief will weigh on her also.

Dear friend, if onward you would go,

Into the town, tell King Arthur

And his knights that no further

Shall I stray, nor would I flee,

I wait here for any who’d be

Pleased to arm, and dares to fight,

And not for naught,’ said the knight,

For I rode to the Round Table here

To claim my lands; though, I fear,

I snatched this goblet, clumsily,

And spilt the wine, gracelessly,

Straight into Queen Guinevere’s lap,

While staking my claim; a sad mishap;

Grasped I a burning wisp of straw,

Lo, I’d have been blackened for sure.

Twas not taken as plunder, indeed,

My royal wealth doth quell the need.

Tell the Queen twas not with intent

I splashed her, before the noblemen,

Whose weapons they had but forgot.

Kings or princes, why do they not

Come to retrieve his golden cup,

And let the King his fresh wine sup?

If they refuse, their boundless fame

Doth lag somewhat behind their name.’

Parzival is brought before King Arthur

‘ALL you request, sir, I shall do.’

Said the lad; without more ado,

He left him, and then, riding on,

Into the town of Nantes was gone.

There all the little children sought

To follow him to the great court

Before the palace, where he found

A vast crowd covering the ground.

He was jostled about, but Iwanet,

An honest page, our hero met,

And offered him his company.

‘God keep you!’ cried the lad, gladly,

‘For that my mother told me to say,

Ere I did leave home, on a day.

Now I see many an Arthur here,

Which will knight me?’ ‘None, I fear!’

Laughed Iwanet, ‘he’s not in sight,

But you may soon see such a knight.’

And he led him into that place,

Where were gathered a noble race.

Above the noise, he sought to call:

‘God keep you, fair folk, one and all,

Especially the King and his Lady!

My mother enjoined me, strictly,

To give these two a special greeting.

Those at the Round Table meeting,

Those too, yet one thing I would know,

Who is the master here? But show

Me to him, for outside the gate

I saw a brave knight who doth wait,

All shining red indeed was he,

And he sends this message by me,

That he awaits there any knight,

Who intends, as he does, to fight.

He is sorry he spilt the wine,

Over the Queen; if it were mine,

That red armour, the King’s gift,

I would my faithful javelin lift,

And fight for it, it seems so fine!’

The fearless lad was jostled about,

For none could quite make him out,

Though from his looks they could see

Never was handsomer progeny

Sired by any. God was indeed

In a fair mood when he decreed

Parzival’s making, whom no fear

Could grip, nor terror force a tear.

So the lad, in whom God contrived

Such perfection, at last arrived,

Before King Arthur; while the Queen,

In leaving the hall, she too had seen

The lad, and looked closely on him,

For it was difficult to dislike him.

‘God reward you for your greeting

Young gentleman,’ declared the King,

While contemplating this raw youth,

‘I’d hope to deserve it, in truth,

Given life and wealth, I assure you.’

‘God grant it! And yet I say to you,

It seems to me a whole year blighted

All this time that I go unknighted.

Tis scarcely happiness I feel,

Delay no longer, but here reveal

How you will make a knight of me.’

‘As honour lives in me, it shall be,’

Replied his host, ‘you so delight,

With your charm, that as a knight

My gift will prove a right fair one.

I’d hate to deny you. Anon,

I shall equip you; all will follow;

Simply wait until the morrow.’

Now, the noble lad stood there,

Trampling like a bustard: ‘I’d dare

To ask for naught here,’ he said,

‘If I could not claim, in its stead,

The armour of that knight outside

Who toward me but now did ride,

I care not to hear of a king’s gift,

Since my good mother will make shift

To grant me one; for she’s a queen.’

Arthur said: ‘The knight you mean,

Is formidable, and his red armour

I dare not grant; I lack his favour

Even now, through no fault of mine;

In wretchedness I drink my wine.

Ither of Gaheviez, that same

Curbs my happiness, mars my fame.’

‘To balk at such a gift,’ said Sir Kay,

‘Would see you ungenerous, I say.

Give the lad his gift, let him loose

On Ither, for here’s a fair excuse;

If from your goblet you would sip,

There’s the top, and here’s the whip,

Let the boy take to the ground

Watch as he flogs him round and round;

To the ladies we’ll commend the fun.

Many trials he’ll face, ere he is done,

And I’m concerned for neither there.

To win the boar’s head, one must dare

To sacrifice the hounds, I fear,

However fine they be, or dear.’

‘I should be sad to deny him,’

Said the king, ‘yet, if I try him,

I fear indeed he might be slain.

He seeks his knighthood now to gain,

And I should aid him,’ said the king,

True in this, as in everything.

Yet the lad accepted the trial;

Dire it proved in a little while.

Sir Kay strikes the Lady Cunneware

PARZIVAL swiftly left the king,

With young and old all following.

Iwanet took him by the hand,

And led him thus, you understand,

Below a long low gallery;

From end to end of it he could see.

Twas so low, that up there he saw

Too woeful an action to ignore.

It was then the Queen’s pleasure

To sit by the window at leisure

With knights and ladies about her;

She gazed now at the lad below her.

There Lady Cunneware sat too,

Proud, and radiant, to the view,

Who never smiled nor ever would

Until she saw the man who could

Win the highest prize, or held it;

For she’d rather die, than see fit

To laugh or smile in other case.

No such smile had crossed her face,

Until the lad went trotting by,

But now her laughter rose on high.

It made her back to smart, indeed,

For Kay the Seneschal it did lead

To seize her by her curling hair,

And clench it, hard as he did dare,

And wind her tresses round his hand,

The lady’s, Cunneware de Lalant.

Twas not her back had sworn the oath,

Yet his staff was applied to both,

And it sank upon clothes and flesh,

Until his thoughts he dared express.

‘You’ve lost your good name for a lie!’

He cried, greatly enraged thereby,

‘But I’m the one to restore it now,

For I shall hammer it home, I vow,

Till in your bones you feel it there.

Many a true man doth oft repair

To Arthur’s court and yet doth fail

To raise a smile, yet now a gale

Of laughter sweeps through you for one

Who’s not a notion, ne’er a one,

Of knightly manner, or fit dress.’

Now anger leads us to excess,

And his right to so strike the maid,

(Her loyal friends were sore dismayed),

No king or emperor would uphold.

The blows indeed were overbold

If she were a hardy knight, yet she

Was a princess born; and certainly,

If her younger or elder brother,

Had seen this insult to their sister,

Orilus or Lahelin I mean,

Fewer blows would there have been.

Antanor predicts that the lady will be avenged by Parzival

ANTANOR, who was thought a fool,

Being ever silent as a stool,

Although he spoke not, the while,

For the same reason she’d no smile,

An oath they’d taken, Antanor,

That had said not a word before

The lady laughed, who thereafter

Had been beaten for her laughter,

Opened his mouth and said to Kay:

‘God knows, Sir Seneschal, I say,

Because of the boy you raised your hand,

Against poor Cunneware of Lalant,

And the lad, on some future day,

Will much discomfort you, Sir Kay,

However friendless he may be.’

‘Since your first words threaten me,

I swear you’ll have no joy of it!’

Cried Sir Kay, in his spiteful fit,

And then he tanned Antanor’s hide

And his two fists had much beside

To whisper in that wise fool’s ears;

For Kay was quick to rouse his tears.

Young Parzival could only linger

And watch the ‘fool’ and lady suffer.

He was angered at their distress,

He clutched his javelin no less!

But round the Queen too great a throng

Were packed, to hurl it in among.

Parzival slays Ither, the Red Knight, and takes his armour

IWANET took leave of our hero,

Who then set out for the meadow,

To meet with Ither, and he brought

The news that none within the court

Were keen to come and break a lance.

‘The king did a gift to me advance.

I told him, for such was your intent,

That you spilt the wine by accident,

And now regretted your clumsiness.

Since none is eager to seek success,

Give me your steed, and all your gear,

For it was gifted to me, tis clear,

And I’m to be made a knight therein,

And, if you will not, why tis a sin,

For I’ll retract my greeting to you;

So if you’re wise, tis what you’ll do.’

‘If Arthur did thus my armour grant

To you,’ said the King of Cumberland,

‘And you can strip that same from me,

My life he’ll grant you! Thus, does he

Favour his friends, perchance? Did you

Serve him in aught which you did do,

That earned you his good will, today?

Your service is prompt to gain its pay.’

‘I’ll seek to earn what’s due to me;

There’s no denying he gave it me.

Hand it over, come, stall no further,

I’d be a suppliant no longer,

But follow the path of the shield,

That doth the fruits of chivalry yield.’

Seizing the other’s bridle, he cried:

‘Is that not Lahelin, there inside,

Of whom my good mother warned me?’

The knight reversed his lance, swiftly,

And thrust at the boy, with such power,

He and his horse fell midst the flowers;

Then, angered, beat him fore and aft

With the butt end, and with the shaft,

So that the blood sprayed in a cloud.

Parzival leapt to his feet, full proud,

He flung his javelin and, there,

Where helm and vizor leave bare

A narrow slit, the tip made entry,

Piercing Ither’s eye, then fully

Passing through the nape, while he

A knight devoid of treachery,

Fell earthwards, breathing his last breath.

Many a woman mourned that death.

Ither of Gaheviez left

A legacy of tears. Bereft

Of her knight, any fair lady

Who felt affection for him, she

Saw happiness vanish, joy yield,

And love escorted from the field.

The raw lad turned the body over

Seeking to remove the armour,

But made little progress there,

Quite baffled by the strange affair.

Helmet or greaves his hands failed

To loosen, for the straps prevailed.

He twisted them, and tried in vain,

That foolish lad, yet Ither’s bane.

The little palfrey and the charger

Whinnied so loudly that, farther

Away, at the moat’s edge, by the wall,

Iwanet the squire, heeded the call;

He was Guinevere’s page and kin,

And swiftly he came riding in,

Finding the mounts both riderless,

And drawn by friendship no less

For this Parzival. There he found

Ither’s dead body on the ground,

And Parzival in perplexity.

He ran to him and effusively

Praising him, spoke of the honour

He had won in slaying the other,

That great king of Cumberland.

Iwanet aids and advises Parzival with regard to the armour

‘GOD bless you! Help me understand

How do I strip him, and don it?

‘I’ll show you all, in a minute.’

Said Iwanet, to Gahmuret’s son.

No sooner said, than it was done,

For, on the field of Nantes, the dead

Gave armour to the living instead,

Though that was but a simple boy.

‘Those boots you shall ne’er employ,’

Said Iwanet, ‘for now your entire

Self must show but knightly attire.’

Parzival jibbed at this decree.

‘Nothing my mother gave to me

Shall e’er leave my body,’ he said,

‘For better or worse’. To Iwanet,

This seemed strange, yet the squire kept

His patience and to show respect

To the boots clad them with bright steel.

Now shining greaves did them conceal,

With them went spurs worked in gold,

That silk, not leather, cords did hold.

These he attached and then, ere he

Offered the chain mail, at each knee,

He laced on the steel guards, and so,

The lad was armed from head to toe,

Despite his restlessness; demanding

His quiver: ‘No, not one javelin

Will I hand you!’ cried Iwanet,

‘Chivalry bids that you forget

The use of such weapons,’ but he

Girded the sword on carefully,

And told him how to draw the blade,

And never to flee, nor seem afraid.

Then he led up the Castalian steed,

The dead man’s mount, long-legged indeed,

Yet Parzival, the stirrups scorning,

Fully-armed to the saddle leaping,

Showed manly vigour, in full play,

Which many praise in our own day.

And Iwanet taught him further

How to deploy, and manoeuvre

Behind his shield, and wait the chance

Against the enemy to advance.

He placed a lance in Parzival’s hand:

‘What’s this?’ the latter did demand.’

‘Why, if a man meets you in the field,

You must thrust it through his shield,

So hard that it splinters; if you do

The ladies shall hear praise of you.’

No painter of shields from Cologne

Or Maastricht, not the finest known,

Could have shown him, the tale says,

To better effect, or earned more praise,

Nor the fine steed he sat upon.

‘Dear friend, and my companion,’

He said to Iwanet, ‘I have gained

What I wished, and have attained

The armour and the goblet; now go,

Greet King Arthur, and tell him so,

Give him the goblet thus, and say

That I endured dishonour this day,

For a boorish knight offended me

By punishing a fair young lady

Who honoured me with her laughter;

Pity for her moved me thereafter,

Her pain has more than touched my heart,

Nay it is lodged there like some dart.

In true companionship, feel my shame.

God keep you, – I go to win a name –

For He has power to protect us all.’

The mourning for Ither

NOW, Ither of Gaheviez,

He abandoned him where he lay,

And Ither’s body, that yet still bled,

Was fair of form, though he lay dead,

Whom Fortune favoured while alive.

If in knightly combat he’d died,

Of a lance-thrust that pierced his shield,

Who’d speak of tragedy on that field?

He died of a javelin’s base powers.

Iwanet gathered the brightest flowers

To cover him, and his next action

Done to recall the Crucifixion,

Was to plant the javelin shaft above,

And then, with dignity and love,

He forced a stick through its head

To form a cross o’er that fair bed;

Then to the city did repair,

To bring news to the fair folk there.

Many a lady did lament,

Many a knight his head now bent

And wept, and by his mourning showed

His deep affection, and sorrow’s load.

Great affliction they suffered there.

The corpse they bore in with care.

The Queen rode out from the city,

Ordering the monstrance, in piety,

To be brought there, and raised,

(Ere she spoke of that lord in praise)

Over the King of Cumberland,

Who had died at Parzival’s hand.

And then the Lady Guinevere

Words of grief spoke, loud and clear:

‘Alas, this deed shall mar the fame

Of Arthur, and tarnish his name;

That he who should, by every right,

Be placed above every fair knight

Of the Round Table, must lie here,

Before Nantes; for it doth appear

He but claimed his inheritance,

Yet death received, and by no lance.

He was indeed of our company,

In his courtesy and his chivalry,

Such that no true ear ever heard

Of him an ill or graceless word.

If treachery’s wild, he was tame,

From his book they erased that same.

Now, all too soon, is he interred,

The seal upon fame’s scroll, conferred

By the courteous heart wrought there,

That, formed in honour, ever fair,

Counselled him perfectly when he

Sought woman’s love, so we might see

Proof of good faith, and dauntless will.

The seed of grief is sown here, still,

Among us women, yet to flourish,

While we our deep sorrow nourish.

From out your wound, lament, Ither,

Issues forth, and doth fill the air.

So red were your locks that never

Could blood dye the flowers redder.

Woman’s laughter you drain away,

You have squandered it all this day!’

So King Ither was laid to rest,

Royal pomp did his rites invest;

His death brought forth fair women’s sighs.

His bright armour proved his demise;

For foolish Parzival’s desire

For that brave armour quenched his fire.

Later, when he was wise, indeed,

How Parzival regretted that deed!

Parzival comes upon the castle of Gurnemanz de Graharz

PARZIVAL’S mount had this virtue

That whatever road it did pursue,

Whether o’er stone or fallen trees,

It ever picked its way with ease.

And whether it was hot or cold

It ne’er sweated, so we are told.

And Parzival never had need

To tighten the girth on his steed

By so much as a single hole,

Though he rode for two days whole.

The simple lad rode it as far,

That day, as any old warrior

Without his gear would seek to do

If he’d been given a day or two,

And Parzival rode in full armour,

And at a gallop moreover,

Rarely a trot, and never rested.

Towards eve his gaze was arrested

By the sight of a castle tower,

And as he neared, within the hour,

More and more of them could he see,

And so, in his simplicity,

He thought by Arthur they were sown,

And a plenteous crop had grown,

All due to Arthur’s sacredness,

Thinking him one that God did bless.

‘My mother’s people farm not so,’

He said: ‘of all her crops, none grow

As tall as this, though it be plain

Tis not for lack of heavy rain.’

Now Gurnemanz de Graharz owned

The castle, and was there enthroned.

Below the walls, stood a linden tree

In a green meadow where it was free

To spread its boughs, for long and wide

The meadow stretched on either side.

The path and mount conspired to lead

The lad to where the master, indeed,

Was seated, while great weariness

Made Parzival’s shield, I do confess,

Swing in a way, to front and rear,

Not too deserving of praise, I fear.

Prince Gurnemanz sat all alone,

Where the linden tree’s leafy dome

Shaded, no doubt as it should,

A man whose heart e’er sought the good,

A captain of true courtesy.

And Gurnemanz did courteously

Receive this guest, as he was bound;

No knight or page was to be found.

Born out of youthful ignorance,

Parzival returned his advance:

‘My mother told me, on a day,

To seek out one whose hair was grey,

And, in return for his counsel,

To learn from him, and serve him well.

And I shall give good service, know,

Since mother said I should do so.’

‘If you come here to seek advice,

Then your goodwill shall be the price

While my counsel I do furnish;

If good advice is what you wish.’

The prince now loosed a sparrow-hawk

From his fist, and while they did talk,

It flew to the castle; as it did soar,

The gold bell tinkled that it wore,

In summons, for a crowd of pages

Handsome, and of sundry ages,

Hastened to join them; Gurnemanz

Requested them, as they did advance,

To escort his guest, and seek his ease.

‘Mother was right; true as the breeze,

An aged man’s words are guileless!’

The lad cried, pleased by his success.

The pages led him to where he saw

A throng of knights before the door,

There they begged him to dismount.

‘A king dubbed me; on his account,

This rider will not leave his seat.

My mother said that I should greet

You all.’ They thanked both him and her.

Greetings done, they sought to offer

Many a plea, ere they found success

(The horse was weary, the man no less)

In persuading him to descend,

But he reached his room in the end.

‘Let us remove your armour, now,

And ease your limbs, if you’ll allow.’

Disarming him, whether or no

He wished it, they made to go,

Though they were truly horrified

By his fool’s garb, his boots beside

Were scarce acceptable; dismayed,

His state to their lord they relayed,

Who was troubled at the thought

Of this boy and of what he sought;

He well-nigh despaired of the lad,

Such his pain at how he was clad,

How ill shod, as he went his way.

Yet one courteous knight did say:

‘I swear that ne’er did my eyes see

So noble a child; it seems to me

That his form is such as Fortune

Would gaze on gladly, late or soon,

Showing the traits of noble birth,

As noble as any on this earth.

How is it then that Love’s fair glance

Is found in this sad circumstance?

I regret to see the Court’s delight

Clad in the manner of this knight.

Bless the mother that bore a son

Possessed of such true perfection.

His armour too is a splendid sight,

And made of him a splendid knight,

Till it was removed. There I saw

Marks of bruises, bloody and sore.’

‘No doubt suffered for some lady,’

His master commented swiftly.

‘Not so, my lord, with his manners

No lady would ever suffer

Him to serve her, though he doth seem

Well-favoured for such a scheme.’

Said his lordship: ‘Come, let us go,

And see the wonder that dresses so.’

Off they went, to visit Parzival,

Who was wounded, you’ll recall,

By a lance that failed to shatter.

Gurnemanz, like a kind father,

Tended the lad most carefully,

And gazed at him most tenderly,

As if twas a child of his own,

Cleansing, bandaging him, alone,

With his own hands. Then to supper,

The lord led the hungry stranger.

He’d had no breakfast when he left

The fisherman’s, and was bereft

Of nourishment; then his armour

Won at Nantes, with its weight brought

Him famished, weary, to the court

Of King Arthur, where they allowed

Him to go hungry midst the crowd,

And with his wound, to add to all.

Now he might sit and sup withal,

And so the lad dined with a will,

And a mass of good things did fill

His stomach and sink out of sight,

The master smiled at his appetite.

Lord Gurnemanz begged him to eat,

Heartily, till he felt replete,

And, thus, put by his weariness.

The time then came to seek his rest,

‘You are weary?’ asked the master,

‘How early did you rise?’ ‘My mother,

Still slept, and heaven knows that she

Never rises early, unlike me.’

Gurnemanz, smiling, led the way

To the chamber where his bed lay,

And told him he must now undress;

He jibbed at it, but nonetheless

It had to be, then, upon the bed,

A coverlet of ermine was spread,

That served to cover his naked form,

So handsome a lad was never born.

His weariness and his lack of sleep

Meant that his posture he did keep

All night, nor turned from side to side

Until the dawn light shone betide.

The lord had them a bath prepare

At mid-morning, while he lay there;

And they did so, at the carpet’s edge,

And strewed rose-petals and sedge,

And though they made little sound,

He woke from sleep, and so he found

The tub, and sat, enjoying it.

I know not who had prompted it,

But the loveliest girls, finely clad,

Entered, with due regard for the lad,

And massaged his bruises away,

All their soft white hands in play.

Little cause did he have to feel

Unloved (though he could not conceal

His foolishness, orphaned as he was

Of common-sense) that was because

His innocence, and his simple heart,

Brought no unkindness on their part.

There he sat in contented ease,

While the modest girls sought to please,

Washing him not quite all over;

Nor did he say a word moreover,

Howe’er they prattled. He did see

A second morn shine there, graciously,

In them; the one vied in brightness

With the other, his face no less

Radiant, as it sought to quench

Both bright lights in their excellence.

They offered a robe but, bashfully,

He refused it, since they might see;

And so the young girls had to leave,

Since that robe he’d not receive.

They could stand there no longer, though

I think they might have liked to know,

If he had sustained some harm unseen,

For women are so kindly, I mean,

Pity will move them whenever

They deem that some friend may suffer.

Their guest now approached the bed,

Where a white doublet lay. He fed

A belt of golden silk around it,

To hold his breeches then in hose

Of scarlet the brave lad did pose,

Ah, those legs, what a splendid pair!

What elegance was apparent there!

Tunic and mantle they were brown,

Long, well-cut, lined, all around,

With dazzling ermine, and adorned

With trimmings that no eye might scorn,

Broad, and of sable, black and grey;

In these he did himself array.

Another fine belt he fastened on,

Costly, a rare clasp set thereon.

Above it all, his handsome head

Showed a pair of lips glowing red.

Now his faithful host did appear

With a company of knights drew near,

To greet him, and they did all declare

They’d not seen the equal anywhere

Of his fair form, and praised that she

Who had brought forth such progeny.

No less in truth than in courtesy

They cried: ‘Why, any fair lady

Of whom this lad may seek favour

Him with her kindness will honour.

Fair welcome and the joys of love

Are his for the asking, if she prove

Appreciative of this knight’s worth.’

All paid him tribute, free of mirth,

These and others, in time to come,

Who saw all that he might become.

His host now took him by the hand,

And led him midst the knightly band,

Asking him how he’d slept that night,

Beneath his roof; thus spoke the knight:

‘If on that day I left my mother

She’d not told me to seek the master,

I find here, how I’d have suffered!

‘Sir, you’re kind; may God reward her!’

Our simple warrior now did pass

To a chapel wherein the Mass

Was sung to God, for the master,

And there at Mass did the latter

Teach him what would still today

Add to one’s true blessings, I say,

To make his offering and then

The sign of the cross, whereby men

Defy the Devil, and punish him.

And then all the company went in

And sat to table, in the hall,

The guest beside the host; and all

The food he saw the guest did eat.

‘I hope it proves not indiscreet,’

Said his host, politely, ‘if I ask

Where you journeyed from, this last.’

And the lad told him, and detailed

All that his travels had entailed,

How’d he left his mother behind,

How the ring and brooch he did find,

And how he had won his armour.

Gurnemanz knew it must be Ither

He had slain, and so he sighed

Pitying how Ither had died;

Yet he insisted it was right

His guest be named as ‘The Red Knight.’

Gurnemanz trains Parzival in the arts of chivalry

NOW, after the board was removed,

The lord a gentle teacher proved,

And sought to tame the raw and wild:

‘My friend you speak as doth a child,

‘Why do you speak still of your mother?

Turn your mind to something other;

Take my advice, avoid all wrong;

Think to what lineage you belong.

I shall begin; now hear the same;

Ne’er must you lose your sense of shame,

If shame be gone, what use the man?

You’d live like a hawk on the hand,

Moulting its feathers; as the bird

Its plumes, you’d lose, in a word,

All your virtues, like plumes that fell,

Downwards, pointing straight to Hell.

You have good looks, a trim figure,

And of a realm may prove the ruler;

If you’re of noble, aspiring stock,

Bear in mind the key to the lock,

Have pity on poor folk’s neediness,

With kindness solace their distress;

Be generous and humble too,

For a decent man, not unlike you,

Who chances to fall on evil days,

Must wrestle with his pride always,

(A bitter struggle for any man)

You should offer a helping hand.

If you relive such a man’s distress,

Then you are such as God will bless;

Such men are in a plight that’s more

Vile than those who beg door to door.

Whether poor or rich, be temperate;

The noble who squanders his estate

Shows a base spirit, while if he

Hoards his wealth too excessively,

Then great dishonour it will bring.

Be moderate then, in everything.

Tis clear that you need good advice.

Eschew your raw ways; think twice.

You should refrain from questioning,

Yet if someone asks you a thing,

Offer them a thoughtful answer,

One that’s to the point, however.

You can see, hear, taste and smell,

And so may be led to reason well.

Temper your courage with mercy,

In such a matter come, follow me;

When you win a man’s surrender,

Accept the plea that he doth tender,

And let him live, and so live long,

Unless he’s done you mortal wrong.

You will oft bear arms, but when

Those arms are laid aside again,

See that you wash your hands and face;

High time, if iron has left its trace!

For you will be handsome once more,

When women’s eyes your looks explore.

Be manly and cheerful in your station,

Such will enhance your reputation.

And hold the ladies in high esteem,

It heightens a man’s worth I deem.

Scorn not their cause a single day,

Such thoughts inspire a man alway.

Lie to them, you’ll deceive many,

But listen, ere you trouble any:

Cunning prospers but not for long,

Compared to love, fine and strong;

The dry branch in the thicket snaps,

And then the watchman who naps,

Wakes, the noise declares the thief.

Many a fight breaks out beneath

The trees, and in the heathland waste.

Compare this with a true love graced

With sure defence against deceit.

Earn Love’s disfavour and you’ll meet

With every manner of disgrace,

A lasting shame on all your race.

And take this lesson now to heart,

Treat not man and woman apart,

For women and men are all one,

As are the daylight and the sun,

Nor can they be parted, indeed,

They rise from the self-same seed;

So note it closely and remember.’

The lad bowed in thanks; moreover

He said naught about his mother,

Though in his heart he did so ever,

As a loving son might do today.

‘Now learn more of the knightly way,’

The lord continued, ‘And think how

You first approached, for I avow

Many a wall where shields are strung

Showed each one of them better hung,

Than the one slung round your neck!

Tis not too late to rein in check

Such things; hasten to the meadow,

Where far more skilful you shall grow.

Let pages come too, bring his steed,

And every knight what he doth need,

And good fresh lances bring them too!’

And so the prince rode out anew,

Onto the field where horsemanship

Was revealed, and tightened his grip,

And showed him how to alter speed

With only a touch of spur, at need,

Thighs beating like wings, and how

To lower his lance and prepare now

For the thrust, and employ his shield

To defend himself upon the field.

‘Let me show you,’ the lord would say,

And taught him thus, in a better way,

How to shun impropriety,

Than with the supple stick we see

Many a teacher in school employ,

When he’d correct some wanton boy.

Then he asked some skilful knight

To ride against him in true fight,

And led the lad as if to tourney,

Who dealt a thrust so furiously,

In a manner all thought extreme,

That he flung a knight of high esteem,

From his horse and to the ground,

Though he recovered at a bound.

A new opponent did now advance,

And Parzival raised a fresh lance.

Youth, strength, and spirit he had;

Gahmuret’s blood was in the lad

And to his courage he was heir,

And though but a beardless boy there,

He nonetheless spurred on his steed,

Made to gallop, and charged at speed,

Aiming at his opponent’s shield.

The knight his seat was forced to yield,

And measured his length on the earth,

Midst broken splinters, and some mirth.

In this manner he downed five men.

Then his lordship led him in again.

Parzival proved his worth and more

In sport, and, later on, in war.

The skilled knights who looked on,

Seeing how this young lad shone,

Acknowledged his courage and skill,

‘As for our master, now, he will

Be done with grief, and live anew.

If he is wise, he will wed him to

His daughter, and so end his woe,

Since Fortune her fair face doth show,

And, for his three dead sons, amends

Through this stranger, she extends.’

Parzival takes leave of Gurnemanz

AND then they all returned, at eve.

Orders the servants did receive

To lay the board, while his daughter

Was summoned there, for he sought her

Presence at table, with them all.

On the fair Liaze he now did call,

When he first saw the girl appear,

‘Allow this true knight to draw near

And kiss you; show him due respect;

Fortune herself his path has decked.

As for you sir, we would demand

That you left the ring on her hand,

If she had one, yet she has none,

Not e’en a brooch like that you won

From the lady in the meadow there.

Who’d grant one to this daughter fair?

While the first had one who gave her

What you chose to acquire from her.

Naught from Liaze can you acquire!’

The lad kissed her lips, red as fire,

While he blushed. None sweet as she,

With the virtue of true modesty.

The table was both long and low,

No need for my lord to elbow

His neighbour, for he sat instead

In sole possession, at its head.

He then seated the fair stranger

Between himself and his daughter.

Whene’er our Red Knight wished to eat,

Liaze with her white hands, soft and neat,

Must carve and slice as her father bade,

None was there whose presence weighed

On their deepening acquaintance.

Well-bred, Liaze did yet enhance

All that her father asked of her.

And those two made a handsome pair.

After the meal, the girl withdrew,

And, in this way, each night anew

They dined for a fortnight; and yet

There was one matter made him fret:

He wished to fight on many a field

Ere to a woman’s arms he’d yield.

Twas noble ambition, so he thought,

That led to the victory he sought

In this life, and the life hereafter;

Words that are true now, as ever.

One morn he begged leave to depart.

His host went forth, with heavy heart,

Beside him; from Graharz they rode,

To the open country, where they slowed:

‘I lose a fourth son now in you,’

Sighed the prince, with feelings true:

‘I thought myself repaid for the woe

Of my threefold tale of loss, for so

It seemed; till now there were but three.

Yet if someone were to courteously

Cut my heart in four, and bear away

Each quarter, I would gladly pay,

Such a price, one quarter for you

Three for my noble sons all who

Died gallantly, for such the reward

That chivalry does to man afford,

Grief borne at the end, without fail,

As the crupper’s borne by the tail.

One death stole all my happiness,

That of Schenteflurs my eldest.

Condwiramurs he sought to aid,

When a strong defence she made

Of her lands, and her fair person.

He fell to Clamide and Kingrun,

So that my heart is pierced through

By sorrow’s lances; and now tis you

Who ride away, too soon, from me,

And leave me here in my misery.

I should die now, since you like not

Liaze the Fair, nor my lands, I wot.

My second son was Count Lascoyt,

Slain by Ider, the son of Noyt,

Competing for the sparrow-hawk.

Thus, robbed of joy, I walk and talk.

Gurzgri was the last of the three,

Lovely Mahaute he wed, for she

Was given in marriage by Ehkunat,

Her proud brother, and after that,

My son fell at Schoydelakurt,

Where he came of his mortal hurt,

Near the royal city of Brandigan;

Mabonagrin slew no finer man;

Mahaute lost her shining beauty,

While his mother died of misery.’

The guest now felt his host’s deep pain,

For he had made the reason plain.

‘My lord, he said, I am not wise,

But if I should win fame, in this guise,

Such as would let me sue for love,

I would then ask you to approve

My marriage to Liaze the Fair,

You daughter. Tis great grief you bear;

But if when the time comes I may free

You from your woe, assuredly

I shall not suffer you to grieve.’

And so Parzival took his leave

Of the faithful lord, and his men.

After three sad throws, now again,

The prince had lost a fourth also,

Doomed once more to a life of woe.

End of Book III of Parzival