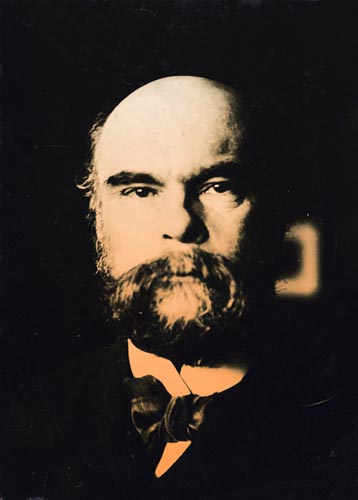

Paul Verlaine

Les Poètes Maudits

‘Portrait of Paul Verlaine’

Willem Witsen (attributed to), 1892

The Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Verlaine’s Foreword.

- I: Tristan Corbière.

- Rescue (Rescousse).

- Epitaph (Épitaphe).

- Hours (Heures).

- The End (La Fin).

- II: Arthur Rimbaud.

- Vowels (Voyelles).

- Evening Prayer (Oraison de Soir).

- The Sitters (Les Assis).

- The Bewildered (Les Effarés).

- The Seekers of Lice (Les Chercheuses des Poux).

- Drunken Boat (Bateau Ivre).

- III: Stéphane Mallarmé.

- Placet.

- Ill-Luck (Guignon).

- Apparition.

- Saint (Sainte).

- The Poem’s Gift (Don du Poème).

- Sonnet: That Night (Cette Nuit).

- The Tomb of Edgar Allan Poe.

- IV: Marceline Desbordes-Valmore.

- A Woman’s Letter (Une Lettre de Femme).

- Oriental Day (Jour d’Orient).

- Renunciation (Renoncement).

- Disquiet (L’Inquiétude).

- Two Loves (Les Deux Amours).

- Two Friendships (Les Deux Amitiés).

- The Sobs (Les Sanglots).

- V: Villiers de l’Isle-Adam..

- Awakening (Réveil ).

- Farewell (Adieu).

- Encounter (Rencontre).

- At the Edge of the Sea (Au Bord de La Mer).

- VI Poor Lelian (Pauvre Lelian, an anagram of Paul Verlaine).

- The Stolen Heart (Le Coeur Volé).

- Faun’s Head (Tête de Faune).

- Index of First Lines

Translator’s Introduction

Verlaine’s ‘Les Poètes Maudits’, or the ‘Accursed’ Poets, was first published in 1884, and later expanded to form this text published in August 1888. Within the work, Verlaine (1844-1896) paid tribute to Tristan Corbière (1845-1875), Rimbaud (1854-1891), Mallarmé (1842-1898), Marceline Desbordes-Valmore (1786-1859) and Villiers de l’Isle-Adam (1838-1889), while calling himself, using an anagram of his name, ‘Pauvre Lélian’. The phrase ‘poète maudit’ had been coined by Alfred de Vigny in his 1832 novel ‘Stello,’ in which he called the tribe of poets ‘la race toujours maudite par les puissants de la terre’, ‘the race that will always be cursed by the powerful ones of the earth’.

Verlaine’s Foreword

One might say ‘absolute’ Poets, to preserve one’s calm, though there is scarcely anything but calm these days; the title has this going for it, that it matches, perfectly, our hatred (and, we are certain, that of the remaining survivors amongst the ‘all-powerful’ in question), for the common readers among the elite, a vulgar phalange that savages us fiercely by their use of the term.

‘Absolutes’ for the imagination, ‘absolutes’ in expression, ‘absolutes’ like the Reys-Nettos (Les Rois-Nets, the pure, or absolute monarchs) of the greatest ages.

But, ‘accursed’! Judge for yourself.

I: Tristan Corbière

Tristan Corbière was a Breton, a sailor, and a master of disdain; all three. A Breton, while scarcely being a practising Catholic, though believing in the devil. Neither of the navy proper, nor the merchant navy specifically, but furiously in love with the sea, such that he only rode it in storms, fiery to excess on that fieriest of horses; one speaks of his prodigies of reckless folly, disdainful of success or glory; so much so that he possessed the air of challenging those two mad creatures to rouse, even for an instant, his pity for them!

Let us pass from the man, so noble in himself, to the poet.

As a versifier and prosodist, there is nothing impeccable, that is to say tedious, about his style. None of the great poets, whom he resembles, is impeccable; beginning with Homer who sometimes nods, ending with Goethe, who is very human whatever one says, and, on the way, encountering the more than irregular Shakespeare. The impeccable are....so, so. Dubois, du bois, and always wooden. Corbière was, in flesh and bone, utterly wild. His verse lives, laughs, weeps but little, mocks well, and jests better. Bitter and salty, moreover, like his dear Ocean, and so no singer of lullabies when he sometimes met with that turbulent friend, but roiling with the rays of sun, moon and stars, amid the swell and phosphorescence of those wild waves!

He became Parisian for a moment, but without the vile mean-spiritedness: hiccups, vomit, a fierce elegant irony, bile and feverishness, exasperating in its genius, to the point of gaiety!

Example:

Rescue (Rescousse)

My guitar there,

If I repair

That savage affair,

Kris (Indian),

Tortured hiss,

Wood of justice,

Box of malice,

Task ill done...

If my voice further

Can’t speak either

To you sweet martyr...

–A thankless one! –

If my cigar,

Help, beamed afar,

Your calm won’t mar,

–Fire burning...

If my dire menace

Vortex past

Graceless blast;

Mute howling!...

If, from my soul,

Sea’s burning bowl

Breaks not whole;

–Frozen being...

–You’d best be going!

Before passing on to the Corbière we most prefer, while enjoying the rest, we must emphasise the Parisian Corbière, the master of Disdain, the Mocker of everything, and everyone, including himself.

Again, read this:

Epitaph (Épitaphe)

He killed himself through ardour and idleness.

If he lives on, then it’s through neglectfulness;

Leaving one sole regret: not being his mistress –

Not born with any end in view

Ever driven by the wind anew,

He was a harlequin ragout

A mere adulterated stew

Of who-knows-what – who never knew

Where gold lay – never owned a sou;

Nerves without nerve, vigour without force,

Momentum – on a random course;

Soulful – and yet no violin;

A lover – yet no stallion within;

Of too many names a name to win.

(...We pass on to other pleasures...)

No poseur – but posing as unique;

Too cynical, so naïve and weak;

Believing naught, so believing all,

His taste forever on distaste did call.

(and again..............................)

Too Self-absorbed for suffering,

The drunk head reeling, the spirit dry,

Done for, yet incapable of ending,

Waiting to live, yet doomed to die,

Waiting for death, yet still living.

A heart without heart, his ill-tenure,

But too successful – in its failure.

Besides this, we ought to cite the rest of that part of the book, or the whole book, or rather re-issue that unique work, Les Amours Jaunes (Wry Loves), published in 1873, and now impossible or nigh on impossible to find, where Villon and Alexis Piron would rejoice to find an often happy rival, and the most illustrious of truly contemporary poets a master at least as great as they!

But wait, we’d not wish to deal with the Breton and the sailor without a few final extracts of verse, sufficient in themselves, from that part of the Amours faunes (‘untamed’ Loves) we are concerned with.

With regard to a friend dead of ‘elegance, drink or tuberculosis’:

He who whistled, with such an elegant air

(And apropos of the same person, most likely)

How fine this sap-filled Youth did seem!

Avid for life, o joy! ... so gentle in his dream.

How he bore his head, or laid it down gladly.

Finally, this devil of a sonnet with so beautiful a rhythm:

Hours (Heures)

Alms for the brigand in the chase!

Cursed be the assassin’s hand!

Blade against blade for the swordsman!

My soul it lacks the state of grace.

I’m the madman of Pamplona,

I fear the moon’s bright laughter

The traitress with her black cloak...

Horror! Lost in candle-smoke

A rattle there sounds noisily...

The evil hour it summons me.

The midnight death-knell leaves a trace...a trace.

I’ve counted fourteen hours and more...

The hour’s a tear. – You wept before,

My heart!... Sing now!... – Count not apace!

Let us admire most humbly – in parentheses – this forceful language, simple in its brutality, charming, surprisingly precise, this science, ultimately, of verse, this rhyme, rare if not rich in its excess.

And now let us speak of an even more superb Corbière.

What a Breton, speaking like a Breton, intensely and tersely, in a noble manner! The child of heathland, vast oak-trees, and the sea-coast, as he was. And how truly this fearsome false-sceptic possessed the memory of, and love for, the strong, deeply superstitious beliefs of his harsh and tender compatriots belonging to those shores!

Hear, or see rather; see, or hear rather (how to express one’s sensations with regard to this monster?) these fragments taken at random from his Pardon de Sainte Anne.

Mother, with blows of an axe carven,

All heart of oak, strong and hard,

Beneath the gold of your robe hidden,

A soul, in good Breton coin, you guard!

Old and mossy, with worn face,

Like the boulder in the flood;

Scarred by tears of love, a race

Rendered dry with tears of blood.

..........................................

Staff for the blind! Crutch

For the old! Soft arms for the new-born!

For your daughter, a mother’s touch!

Parent to orphans, lost, forlorn!

O flower of the fresh virgin!

Fruit of the wife with milk aplenty!

Refuge for the widow-woman...

The widower’s Lady-of-Mercy!

..........................................

Pity the young mother, alone,

Of that babe, by the road ahead.

If someone should throw a stone,

Then let it turn to honest bread!

..........................................

Impossible to quote all of the Pardon within the framework we have imposed on ourselves, but it would seem wrong to take leave of Corbière without giving the poem entitled The End in its entirety:

The End (La Fin)

‘O so many sailors, so many captains

Etc.’ (V. Hugo)

So, all those mariners – sailors, captains

Forever submerged in their vast Ocean...

Lost, carelessly, to the far distance

Are dead – as their departing motion.

So be it! It’s their role; they died with their boots on!

Flask hiding the living heart, sou’wester on...

Dead...Give thanks: Death’s a poor sailor;

Let her sleep with you: she’s a fine partner...

So, let’s go: Unyielding! Snatched from the rigging!

Or lost in a squall, an unforgiving....

Squall...is it Death, that sail, at last,

Beating low in the waves! ... Floundering, rather...

A blow from the leaden sea, and the tall mast

Beating the waves flat...sinking rather.

Sinking – Sound the word. Your death so pale,

And nothing grand aboard, in the heavy gale...

Nothing grand ahead for the bitter grimace

Of the struggling sailor – Onward then, give way!

Old fleshless phantom, Death, as if in play,

Changes – the Sea’s her face!...

Drowned? – Ah! On then! Freshwater are the drowned.

Sunk! Body and cargo! To the cabin boy, downed,

Defiance in the eyes, a curse on his lips!

Spitting a chewed quid out with the sea’s wine,

Drinking, without aversion, his vast cup of brine.

How they’ve drunk their death in sips –

No cemetery rats, no six-foot-deep:

To the sharks they go! A sailor’s soul

Into no coarse potato-bed shall seep,

It breathes-in every tide, where waters roll.

See the swell rise on the horizon;

It appears like some amorous pose

Of a loose woman half-drunk with passion...

There, they are! – The swell has its hollows –

Listen, listen to that tormented grind!

It’s their anniversary! Returning often!

Poets, keep to yourself those songs of the blind,

– These: their De profundis the wind blows them.

...Let them roll endlessly in virgin spaces!...

Let them roll naked, green, without covers

To pine-wood boxes, nails, candles, faces,

– Let them roll there, those upstart landlubbers!

II: Arthur Rimbaud

We have had the pleasure of knowing Arthur Rimbaud. Today, circumstances separate us, without, be it understood, diminishing our profound admiration for his genius and character.

At the relatively distant period of our intimacy, Arthur was a youth, sixteen or seventeen years of age, already endowed with all the poetic equipment that the true public should know of, and which we will attempt to analyse by citing as much as we can.

The youth was tall, almost athletic in build, with the perfectly oval face of an angel in exile, with dishevelled light-brown hair, and eyes of a disturbingly pale blue. From the Ardennes, he possessed an attractive native accent, too swiftly lost, and the gift of prompt assimilation natural to the people of that region, which perhaps explains the rapid evaporation beneath the bland sun of Paris of that vein, that tendency to speak like our forefathers whose direct and precise language was not, in the end, always wrong! We will concern ourselves, firstly, with the initial tranche of Arthur Rimbaud’s work, the product of early adolescence – rash, sublime, miraculous puberty! – in order to examine, subsequently, the various evolutions of that impetuous spirit as far as its literary end.

Here, a parenthesis: if these lines chance to meet his eyes, Arthur Rimbaud should know that we do not judge men’s motives and he is assured of our complete approbation (and of our deep sadness, also) at his abandonment of poetry provided, as we do not doubt, that this abandonment is for him, logical, genuine and necessary.

Rimbaud’s work from the time of his very early youth, that is to say 1869-1871, is plentiful enough and would fill a whole volume. It consists generally of short poems, sonnets, triplets, stanzas of four, five or six lines. The poet never uses a dull rhyme. His verse, solidly grounded, rarely employs fireworks. Few loose caesuras, even fewer rejets (a single emphatic opening word to a line of verse, linked syntactically to the previous line). The choice of words is always exquisite, sometimes pedantic by design. The language is sharp and clear, remaining so even when the idea and meaning grows more obscure. Honourable rhymes.

We could provide no better justification of what we have said than to present you with the sonnet Voyelles.

Vowels (Voyelles)

A black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels

Someday I’ll talk about your secret birth-cries,

A, black velvet jacket of brilliant flies

That buzz around the stenches of the cruel,

Gulfs of shadow: E, candour of mists, of tents,

Lances of proud glaciers, white kings, shivers of parsley:

I, purples, bloody salivas, smiles of the lonely

With lips of anger or drunk with penitence:

U, waves, divine shudders of viridian seas,

Peace of pastures, cattle-filled, peace of furrows

Formed on broad studious brows by alchemy:

O, supreme Clarion, full of strange stridencies,

Silences crossed by worlds and by Angels:

O, the Omega, violet ray of her Eyes!

The Muse (Too bad! Long live our forefathers!) the Muse, we declare, of Arthur Rimbaud, plucks all the strings of the harp, strums all those of the guitar, and caresses the rebec with an agile bow, beyond compare.

As a master of deadpan humour, Arthur Rimbaud occupies first place, when it suits him, while remaining the great poet God made him.

As proof, Oraison de Soir, and those Assis ready to fall forward on their knees!

Evening Prayer (Oraison de Soir)

I sit to life – an angel in a barber’s chair,

A finely fluted beer-mug grasped in my fist,

A curve to its neck and belly, a pipe there

In my teeth, air rank with impalpable mist.

Like warm excrement in an old dovecote,

A thousand Dreams inside softly burn:

At times my sad heart like sapwood floats

Bloodied by the dark gold dripping urn.

When I’ve drunk my dreams, carefully,

Having downed thirty or forty jars, I stop,

And gather myself, to ease my bitter need:

Gentle as the Lord of cedar and hyssops,

I piss towards dark skies, high and heavenly,

Approved of by the giant heliotropes.

The Sitters have something of a history that we should perhaps recount, so that one might comprehend them better. Arthur Rimbaud, who was then in his second term as an external student at the Lycée de ***, indulged in long truancies from school, whenever he felt like it – enough! Weary of surveying mountain, wood and plain – What a traveller he was! – he entered the library in the said town and demanded books offensive to the ears of the chief librarian whose name, unfitted for posterity, dances on the end of our pen, but what does the good man’s name matter in this accursed work? The worthy bureaucrat, obliged by his very function, to deliver up to Rimbaud, on request, Contes Orientaux, and various libretti by Favart, mingled with vague scientific treasures, ancient and rare, grumbled about finding them for this rascally lad and willingly sent him back, by word of mouth, to his uncherished studies of Cicero, and Horace, and we know not what Greeks too. The rascally lad, who, by the way, particularly appreciated the Classics and knew them infinitely better than the old codger himself, finally ‘became irritated’ hence the masterpiece in question.

The Sitters (Les Assis)

Thick lenses, pockmarked, eyes ringed with green,

Their bulging fingers clenched to their femurs;

On their sinciputs, vague plated angers seen,

Like leprous blooms some ancient wall offers.

They’ve grafted, with a love nigh epileptic,

Their fantastic frames to the great black skeletons

Of their chairs. Their feet enlaced, for epic

Morns and eves, round the rickety pinions.

Old men woven to their seats like braids,

Feeling bright suns percussive on the skin,

Or eyes on a window where the snow fades,

Trembling like toads, a woeful quivering.

And their Seats prove kind to them: seasoned

Brown, the straw yields to the angle of their backs;

Their souls lit by ancient suns, and swaddled

In braided ears, that yield ripe grain in sacks.

And the Sitters, knees to chins, lively pianists,

Ten fingers under their seats to the drum’s murmurs,

Hear the faint lapping of barcarolles, tristes,

And their heads sway like those of lovers.

Oh! Rouse them not! Shipwrecked there...

Stirred cats they hiss, rising on their haunches,

Slowly opening shoulder-blades, to glare!

Trousers eating at their bloated paunches.

And you hear them banging their bald heads

On sombre walls, twining their tangled feet, like claws,

Their coat buttons, fawn sloes ahead,

Catching your eye, in the depths of corridors.

Then, they own an invisible hand that kills;

Their return stare oozes that black venom

With which the beaten dog’s pained aspect fills.

You’re trapped in a vile tunnel, sweating, numb.

Stale, their fists in soiled cuffs clenched,

Of those who roused them, they think the worst,

And, from morn to eve, the tonsils bunched

Behind those meagre throats seek to burst.

With visors lowered in austere sleep,

They’ll dream, in the arms of each fecund seat,

Of sweet little selvaged chairs they’ll keep

To border proud offices, all trim and neat.

Flowers of ink, spitting commas like pollen,

Rock them – the line of couched calyxes appears

Like a sword-lily’s, rocked by the dragonflies’ passion

–And their members, teased by those bearded ears!

We wished to repeat all of this skilfully and coolly extravagant poem, to the last logical line of such happy boldness. Thus, the reader can behold the power of irony, the terrifying verve of this poet whose higher gifts it remains to consider, supreme gifts, a magnificent testimony to Intelligence, a proof, proud and French, very French (we here proclaim, in these days of craven internationalism) of a natural and mystical superiority of race and caste, an incontestable affirmation of that immortal kingship of the Human Spirit, Soul and Heart: the Grace and Strength and lofty Rhetoric abjured by our interesting, subtle, picturesque but narrow, and more than narrow, thin and insubstantial, Naturalists of 1883!

We have had examples of Strength in the work inserted above, yet is it not present even at those points, cloaked in paradox, and redoubtable good humour, where it appears disguised in some way? We find it, in all its integrity, wholly fine and pure, at the end of that work. For the moment it is Grace which brings forth lambs. A special grace, unknown indeed until now, where the bizarre and strange salt and pepper the extreme sweetness, the divine simplicity, of thought and style.

For our part, we know nothing in any literature so tender yet slightly fierce, so cordial in its kindly use of caricature, of such goodness, and so frank, sonorous, and masterful in its outpouring as:

The Bewildered (Les Effarés)

Black in the mist and snow

Where a grille lights a row

Of round backsides.

Five kids kneeling – misery!

It’s only the baker they can see:

The heavy blonde bread, besides,

The strong white arm that kneads it so

And then stuffs the greyish dough

Into an open hole.

The kids hear the bread baking,

And the smiling baker singing

Some old rigmarole;

Huddled there, none of them moving,

The breath from the grille rising

Hot as a fevered chest.

When, for some midnight feast,

Of a brioche shape released

The oven shall divest,

When under the darkened beams,

The loaf, perfumed it seems,

And the cricket sings,

Let this warm hole breathe life,

Their souls are so enticed

Under their ragged things,

They feel so, life’s pure hold,

Jesus’s poor, as icy cold,

As ever they could be there,

Sticking each little pink snout

To the grille, and grunting out

Some kind of prayer,

Through the holes there, stupidly,

Bent from the light, you see,

Of the open sky, stuck fast,

So tight that their breeches tear,

Their shirts fluttering, bare

To the wintry blast.

What say you? We, finding in another form of art an analogy which the originality of this little cuadro (scene) prevents us finding amongst the poets, are forced to say it is, for better or worse, a painting by Goya. Inspecting the works of Goya and Murillo certainly justifies the comment. Les Chercheuses des Poux is Goya again, on this occasion a luminous exasperated Goya, white on white with effects in pink and blue, and that unique touch of the fantastic. But how superior the poet always is to the painter, both in heightened emotion and the singing effect of well-made rhyme!

Bear witness:

The Seekers of Lice (Les Chercheuses des Poux)

When the child’s brow, tormented by red,

Implores the white crowd of half-seen dreams,

Two charming sisters come close to his bed

Slender-fingered, with silver nails it seems.

They sit the child down in front of the window,

Wide open to where blue air bathes tangled flowers,

And through his thick hair full of dewfall,

Move their fine fingers, fearful, magical.

He hears the sighing of their cautious breath

That flows with long roseate vegetal honeys,

And is interrupted sometimes by a hiss,

Saliva caught on the lips or desire to kiss.

He hears their dark lashes beating in perfumed

Silence: and their fingers, electrified and sweet

Amidst his grey indolence, make the deaths

Of little lice crackle beneath their royal treat.

It’s now the wine of Sloth in him rises, the sigh

Of a child’s harmonica that can bring delirium:

Prompted by slow caresses, the child feels then

An endlessly surging and dying desire to cry.

It is not only the final irregular rhyme within the last stanza, not only the last sentence resting between its initial lack of conjunction and the end-point, as if hanging suspended, which adds the lightness of a sketch, a shaky workmanship to this frail plough of a piece. Do not the lovely rhythm too, the beautiful Lamartinian swaying, in these few lines seem to extend into music and dream! Racinian even, dare we add, and why not go as far as to confess them Virgilian?

Many another exquisitely perverse or utterly chaste example of Grace, to transport you with ecstasy, tempts us, but the conventional limits of this second essay, already quite long, make it right to pass beyond many delicate miracles and enter, without delay, the temple of splendid Strength, into which the magician invites us with his:

Drunken Boat (Bateau Ivre)

As I floated down impassive Rivers,

I felt myself no longer pulled by ropes:

The Redskins took my hauliers for targets,

And nailed them naked to their painted posts.

Carrying Flemish wheat or English cotton,

I was indifferent to all my crews.

The Rivers let me float down as I wished,

When the victims and the sounds were through.

Into the furious breakers of the sea,

Deafer than the ears of a child, last winter,

I ran! And the Peninsulas sliding by me

Never heard a more triumphant clamour.

The tempest blessed my sea-borne arousals.

Lighter than a cork I danced those waves

They call the eternal churners of victims,

Ten nights, without regret for the lighted bays!

Sweeter than sour apples to the children

The green ooze spurting through my hull’s pine,

Washed me of vomit and the blue of wine,

Carried away my rudder and my anchor.

Then I bathed in the Poem of the Sea,

Infused with stars, the milk-white spume blends,

Grazing green azures: where ravished, bleached

Flotsam, a drowned man in dream descends.

Where, staining the blue, sudden deliriums

And slow tremors under the gleams of fire,

Stronger than alcohol, vaster than our rhythms,

Ferment the bitter reds of our desire!

I knew the skies split apart by lightning,

Waterspouts, breakers, tides: I knew the night,

The Dawn exalted like a crowd of doves,

I saw what men think they’ve seen in the light!

I saw the low sun, stained with mystic terrors,

Illuminate long violet coagulations,

Like actors in a play, a play that’s ancient,

Waves rolling back their trembling of shutters!

I dreamt the green night of blinded snows,

A kiss lifted slow to the eyes of seas,

The circulation of unheard-of flows,

Sung phosphorus’s blue-yellow awakenings!

For months on end, I’ve followed the swell

That batters at the reefs like terrified cattle,

Not dreaming the Three Marys’ shining feet

Could muzzle with their force the Ocean’s hell!

I’ve struck Floridas, you know, beyond belief,

Where eyes of panthers in human skins,

Merge with the flowers! Rainbow bridles, beneath

the seas’ horizon, stretched out to shadowy fins!

I’ve seen the great swamps boil, and the hiss

Where a whole whale rots among the reeds!

Downfalls of water among tranquilities,

Distances showering into the abyss.

Nacreous waves, silver suns, glaciers, ember skies!

Gaunt wrecks deep in the brown vacuities

Where the giant eels riddled with parasites

Fall, with dark perfumes, from the twisted trees!

I would have liked to show children dolphins

Of the blue wave, the golden singing fish.

– Flowering foams rocked me in my drift,

At times unutterable winds gave me wings.

Sometimes, a martyr tired of poles and zones,

The sea whose sobs made my roilings sweet

Showed me its shadow flowers with yellow mouths

And I rested like a woman on her knees...

Almost an isle, blowing across my sands, quarrels

And droppings of pale-eyed clamorous gulls,

And I scudded on while, over my frayed lines,

Drowned men sank back in sleep beneath my hull!...

Now I, a boat lost in the hair of bays,

Hurled by the hurricane through bird-less ether,

I, whose carcass, sodden with salt-sea water,

No Monitor or Hanseatic vessel could recover:

Freed, in smoke, risen from the violet fog,

I, who pierced the red skies like a wall,

Bearing the sweets that delight true poets,

Lichens of sunlight, gobbets of azure:

Who ran, stained with electric moonlets,

A crazed plank, companied by black sea-horses,

When Julys were crushing with cudgel blows

Skies of ultramarine in burning funnels:

I, who trembled to hear those agonies

Of rutting Behemoths and dark Maelstroms,

Eternal spinner of blue immobilities,

I regret the ancient parapets of Europe!

I’ve seen archipelagos of stars! And isles

Whose maddened skies open for the sailor:

– Is it in depths of night you sleep, exiled,

Million birds of gold, O future Vigour? –

But, truly, I’ve wept too much! The Dawns

Are heart-breaking, each moon hell, each sun bitter:

Fierce love has swallowed me in drunken torpors.

O let my keel break! Tides draw me down!

If I want one pool in Europe, it’s the cold

Black pond where into the scented night

A child squatting filled with sadness launches

A boat as frail as a May butterfly.

Bathed in your languor, waves, I can no longer

Cut across the wakes of cotton ships,

Or sail against the pride of flags, ensigns,

Or swim the dreadful gaze of prison ships.

Now, what comment to make on Les Premières Communions (First Communions) a poem too long to display here, especially after our extensive quotations, and whose spirit we greatly detest, which appears to us to derive from an unfortunate encounter with the senile and impious Michelet, the Michelet of women’s soiled underclothes and the backside of Parny (the other Michelet none adore more than us) yes, what comment to make on this colossal piece, except that we love its profound command, and every line without exception. Thus, within it, there is:

Adonai! ... – In their Latin endings dressed,

Skies shot with green bathe Brows of crimson,

And, stained by pure blood from heavenly breasts,

Across swirling suns, fall great snowy linens!

Paris se repeuple, written in the aftermath of ‘The Week of Blood’ (The defeat of the Commune: May 21-28 1871),

seethes with beauties.

.................................................

Hide the dead palaces with wooden benches,

The ancient day, fearful, cleanses your eyes,

Here’s the red gathering of twisted haunches.

.................................................

When your feet have danced in furious wise,

Paris! When you’ve felt the knife-blows redouble,

When you rest, retaining in your clear eyes

A little of the goodness of untamed renewal...

.................................................

In this vein, Les Veilleurs (The Watchers) a poem, alas, no longer in our possession, and which we cannot reconstitute from memory, has left the strongest impression any verse has brought us. It is of a broad resonance, a sacred sadness! And with such a note of sublime desolation that in truth we dare to believe it by far the most beautiful that Arthur Rimbaud has written! Many another first-rate piece has passed through our hands that a malicious fate and the whirlwinds of fairly accident-ridden journeying has caused us to lose sight of. So here we earnestly request all our friends, known or unknown, who possess Les Veilleurs, Accroupissements (Squattings), Les Pauvres â l’Église (The Church Poor), Les Réveilleurs de la Nuit (The Nightwatchmen, an article rejected by Le Figaro), Douaniers (Customs-Men), Les Mains de JeanneMarie (JeanneMarie’s Hands), Les Soeurs de Charité (The Sisters of Charity), and all things signed with that prestigious name, to kindly send them to us, in the likely event of the present work being published. In the name of Literature, we repeat our prayer to them. The manuscripts will be returned, scrupulously, once a copy has been made, to their generous owners.

It is time to think of concluding this section, which has assumed such grand proportions, for these excellent reasons:

The works of Corbière and those of Mallarmé are secure for all time, some will ring out on the lips, others in the memories of those worthy of them. Corbière and Mallarmé are published, that small yet immense thing. Rimbaud, too disdainful of the process, more disdainful even than Corbière, who at least hurled his book in the face of our century, wished none of his poetry to appear in fact.

One piece, which was instantly denied or disowned by him, was inserted without his knowledge, and it was well done, in La Renaissance, in in its first year of issue, around 1873 (La Renaissance Littéraire et Artistique published 1872-1874). It was called Les Courbeaux (The Rooks). The curious may regale themselves with that patriotic, but nobly patriotic thing, which for our part is much to our taste, though as yet imperfect. We are proud to offer our intelligent contemporaries a goodly share of that rich confectionery, Rimbaud!

Had we consulted Rimbaud (whose address is unknown to us, or rather of immense vagueness) he would probably have advised against undertaking this work, at least as far he was concerned.

Thus, he made himself accursed, this Accursed Poet! But the friendship, the literary devotion, we dedicate to him, has ever dictated these lines, has rendered us indiscreet. So much the worse for him! So much the better, is it not, for you? All of the treasure forgotten by this indifferent owner will not be lost, and if we commit a crime by it, then felix culpa, it is a happy fault.

After spending time in Paris, then in various more or less fearsome peregrinations, Rimbaud changed tack, and worked (him!) with a naïve and extreme simplicity of expression, using only assonance, generic words, childish or common phrasing. He accomplished, thus, a wondrous subtlety, a real imprecision, a charm almost imperceptible in its slenderness and delicacy.

It’s found, we see!

What? – Eternity.

It’s the sun, free

To flow with the sea.

But the poet has vanished. We will hear talk of a true poet, employing a special meaning of the word.

An astounding writer of prose followed. A manuscript, whose title escapes us, containing strange mysticisms and the most acute psychological insights, fell into hands that unknowingly led him astray.

Une Saison en Enfer (A Season in Hell) published in Brussels, in 1873, by Poot and Company, 37 Rue au Choux (Jacques Poot) sank, body and all, into a monstrous oblivion, the author having wholly neglected to ‘launch’ it.

He travelled the continents and oceans, with scant resources, proudly (wealthy, if he had wished otherwise, due to his family and class) having written, again in prose, a superb series of pieces, Illuminations, lost forever, we fear.

He said, in his Saison en Enfer: ‘My day is done: I’m quitting Europe. Sea air will scorch my lungs: lost climates will tan me.’

All that is fine, and the man has been true to his word. Rimbaud the man is free, it is only too clear, and that we conceded to him at the start, with a most legitimate reservation that we will stress in conclusion. But were we not right, we, intoxicated with the poet, to take him, this eagle, and hold him here, caged in this manner, and could we not, additionally, in supererogation (if Literature were to see such a loss consummated), lament aloud with Corbière, his elder brother, though not his big brother, ironically? And in a melancholy way? O yes! Furiously? Ah, but yes!

It is done with,

This holy oil, and

He is done with,

The Sacristan!

III: Stéphane Mallarmé

In a book, not destined to appear, I once wrote, apropos of the Parnasse Contemporain (The Contemporary Parnassus, three poetry anthologies published by Alphonse Lemerre, in 1866, 1871 and 1886) and its principal editors:

‘Another poet, and not the least of them, was attached to this group.’

‘He was then living in the provinces, employed as an English teacher, though in frequent correspondence with Paris. He furnished the Parnasse with poems of such novelty as to provoke scandal in the newspapers. Preoccupied, certainly, with beauty, he considered clarity a secondary grace, and while his verse was still plentiful, musical, rare, and languid or excessive as necessary, he mocked everything to please the refined, of whom he was, himself, the most difficult to please. And how badly he was received by the Critics, this pure poet who will endure as long as there is a French language to witness to his gigantic effort! How they mocked the “somewhat deliberate extravagance” as well as the “somewhat” too indolent expressions of a tired master, who had defended himself more effectively perhaps when he was a literary lion, and as well-equipped with teeth as he was violently adorned with the long hair of Romanticism! In the pleasant pages “at the heart of” serious Revues almost everywhere, it became fashionable to laugh, to summon the accomplished writer back to the language, the assured artist back to the sentiment of beauty. In the most influential, fools treated him as a madman! As a badge of honour, writers worthy of the name chose to enter this mindless public fray; one has seen, among the men of spirit and good taste ‘mired in stupidity’, masters of justified audacity and great good sense; Monsieur Barbey d’Aurevilly, alas!

Irritated by the Parnassians’ wholly theoretical Im-Pass-si-bi-li-ty (which had to be THE order of the day in the fight against Sloppiness) this wonderful novelist, this unique polemicist, this essayist of genius, undoubtedly the first of all among our acknowledged writers of prose, published a series of article against Le Parnasse in Le Nain Jaune (The Yellow Dwarf, the satirical and political journal) where the enraged spirit yielded only to the most refined cruelty, the ‘little medal’ awarded to Mallarme was particularly charming, but so unjust as to revolt all of us, more so than our own personal injuries. How such errors of Opinion mattered, how they still matter to Stéphane Mallarmé, and those who love him as he should be loved (or detested) – immensely!’ (Voyage en France par un Français: Le Parnasse Contemporain)

Little needs changing in this assessment of barely six years ago, and which could be dated to the day on which we read Mallarmé’s poetry for the first time.

Since that time the poet has been able to enhance his style, to better achieve his aims – it has remained the same, not stationary, thank God! but more brilliant with the graduated light of evening, at noon or in the afternoon, commonly.

That is why we wish, while ceasing to weary our little audience for a moment with our prose, to set before their eyes a sonnet and a terza rima old, and unknown, we believe, which will win them at our blow to our dear poet and dear friend, attempting, in the dawn of his talent, all the tones of an incomparable instrument.

Placet

Princess! In jealousy of a Hebe’s fate

Rising over this cup at your lips’ kisses,

I spend my fires with the slender rank of prelate

And won’t even figure naked on Sèvres dishes.

Since I’m not your pampered poodle,

Pastille, rouge or sentimental game

And know your shuttered glance at me too well,

Blonde whose hairdressers have goldsmiths’ names!

Name me...you whose laughters strawberry-crammed

Are mingling with a flock of docile lambs

Everywhere grazing vows bleating joy the while,

Name me...so that Love winged with a fan

Paints me there, lulling the fold, flute in hand,

Princess, name me the shepherd of your smiles.

(1861)

(Translator’s note: the use of terza rima could not be captured here, nor in the following poem)

A hothouse flower beyond price, is it not! Culled in how delightful a manner, by the mighty hand of the master-smith who wrought it.

Ill-Luck (Guignon)

Beyond the sickening human abodes

Leapt, in a moment, the savage manes

Of beggars of azure, lost on our roads.

A wind, mixed with ash, fluttered their banners,

Where the ocean’s divine swell strained.

It gouged blood-stained ruts round one or another.

Hell, they defied; heads high, they travelled,

Without bread, staffs, urns to disavow,

Biting the gold rind of the bitter Ideal.

Most groaned in nocturnal ravines; now

Drunk with joy, on seeing their blood flow,

Death is a kiss on their taciturn brow.

If they’re conquered, it’s by a powerful angel,

Reddening the horizon with his sword’s lightning.

Pride bursts from those hearts ever-thankful.

They suck on Pain as they suck on Dream.

And when they rhyme their voluptuous tears,

When folk kneel and the mother is seen,

They are consoled, in their majesty; though

They possess brothers knocked underfoot,

Scorned masters of tortuous chance, also;

With briny tears, their pale cheeks scored,

They eat ashes with a like passion,

But driven by the fate of the vulgar horde.

They too could sound, to the drum’s stutter,

The servile pity of dull-eyed races,

Like Prometheus but without the vulture!

No. Old, and frequenting waterless deserts,

They march to a wrathful skeleton’s whip,

That of Ill-Luck whose mockery so hurts.

If they stumble on, he’ll clamber up after;

The torrent crossed, plunge them into a pool,

And make a fool of the finest swimmer.

Thanks to him, if we sound his weird trombone,

Children, in obstinate mockery,

With their hands, blow a fanfare, of their own.

Thanks to him, if they seek some faded fay,

With flowers with which impurity is lit,

Slugs will be born on their cursed bouquet.

With his feathered felt hat, this dwarfish skeleton,

Booted, whose armpits have worms for hairs,

Is, for them, the sum of human derision.

And if, whipped, they rouse the cruel fellow anew,

Their swishing rapier chasing the moonlight

That snows on his carcase, and passes through.

Lost without pride in their harsh misfortune,

Scorning vengeance by pecks of a beak,

They covet hatred, the grudge their sole tune.

They grant amusement, when fiddles are nigh,

To women, and scions of the ancient rabble,

The ragged who dance when the pitcher’s dry.

Learned poets preaching vengeful intent,

Seeing them broken, not knowing their ills,

Claim them as feeble, unintelligent.

‘They, without begging like the indigent,

Could rear like a buffalo and suck up the storm,

Savouring their eternal ills in the present:

We’ll make the Strong drunk on incense, who oppose

The wild Seraphim of Evil! Those mountebanks

Would have us cease, yet lack bloodied clothes.’

When all have spat on them, in disdainful praise,

Bare, thirsting for greatness, that pray for storms wildly,

These Hamlets, drenched in playful malaise,

Hang themselves, on the lamp-posts, ridiculously.

At about the same time, but evidently a little later rather than earlier, comes the exquisite:

Apparition

The moon was saddened. Seraphim weeping,

Bow in hand, in the calm of flowers, dreaming,

Misted, drew from the viol’s dying

White sobs over white corollas gliding –

It was the blessed day of your first kiss.

My dreaming sought to martyr me like this,

Expertly drunk on sadness’s lament,

That, even without regret and disappointment,

Leaves the culling of a Dream to the heart that culled it,

I strayed, eyes on the ancient stones, sunlit,

When, with the light in your hair, on the street,

And at eve, you appeared, smiling, discreet,

And I thought I saw the fay, in the veil of brightness,

Who, above the spoiled child, in sweet sleep’s caress,

Once passed, shedding, from half-closed hands, always,

A snow of perfumed stars from white bouquets.

And the less venerable but adorable:

Saint (Sainte)

At the window concealing

The old sandalwood, despoiler

Of his viol’s glittering,

Long ago, with flute or mandora,

Stands the pale Saint spreading

The old book’s unfolding spine

At the Magnificat, flowing

Long ago, for vespers or compline:

This glassy vessel of light

Let the Angel touch, harp in hand

Formed, like its evening flight,

For the delicate phalange

Of a finger, lacking old sandalwood

Or old book, held in balance

On its instrumental plumage,

Musician of silence.

These wholly unpublished poems lead on to what we might call the era of the public Mallarmé. Too few pieces of essential colour and music therefore appeared in the first and second Parnasses Contemporains where they might be admired at one’s ease. Les Fenêtres (The Windows), Le Sonneur (The Bell-ringer), Automne, a sufficiently long fragment of a Hérodiade, seem to us supreme among these supreme things, but we will not insist on quoting from published material which is far from unknown, unlike that in manuscript, as is the case with – how, if not by the CURSE it earned, though no more heroically than the poetry of Rimbaud and Mallarme – that vertiginous book of Amours Jaunes by the stupefying Corbière. We prefer to grant you the joy of reading new and precious unpublished work, attributable, according to us, to the intermediate period in question.

The Poem’s Gift (Don du Poème)

I bring you the child of an Idumean night!

Black, with pale naked bleeding wings, Light

Through the glass, burnished with gold and spice,

Through panes, still dismal, alas, and cold as ice,

Hurled itself, daybreak, against the angelic lamp.

Palm-leaves! And when it showed this relic, damp,

To that father attempting an inimical smile,

The solitude shuddered, azure, sterile.

O lullaby, with your daughter, and the innocence

Of your cold feet, greet a terrible new being:

A voice where harpsichords and viols linger,

Will you press that breast, with your withered finger,

From which Woman flows in Sibylline whiteness to

Those lips starved by the air’s virgin blue?

To tell the truth this idyll was wickedly (wickedly!) printed, at the end of the last reign, by a very tedious weekly journal, le Courrier de Dimanche (The Sunday Courier). But what does this fractious claim signify, since to all fine spirits The Gift of the Poem, accused of an involved eccentricity, is found to be the supreme dedication by a pre-eminent poet to half his soul of one of those fearful efforts that we love despite all, while trying not to love them, and which we dream of defending utterly, even from ourselves! The Courrier de Dimanche was republican, liberal and protestant; but whether republican wearing any cap, or monarchist of whatever bearing, or whether indifferent to the import of public life, is it not true that et nunc, et semper et in saecula (‘now and forever, world without end’) the true poet sees himself, feels himself, knows himself to be cursed by the powers that be, of whatever party, O Stello! (See De Vigny’s ‘Stello’, 1832)

The poet’s brow frowns on the public, but his pupils dilate, and his heart grows firmer without shutting itself away, and this is the prelude to his definitive mode of being:

Sonnet: That Night (Cette Nuit)

When the shadow with fatal law menaced me

A certain old dream, sick desire of my spine,

Beneath funereal ceilings afflicted by dying

Folded its indubitable wing there within me.

Luxury, O ebony hall, where to tempt a king

Famous garlands are writhing in death,

You are only pride, shadows’ lying breath

For the eyes of a recluse dazed by believing.

Yes, I know that Earth in the depths of this night,

Casts a strange mystery with vast brilliant light

Beneath hideous centuries that darken it the less.

Space, like itself, whether denied or expanded

Revolves in this boredom, vile flames as witness

That a festive star’s genius has been enkindled.

As for this sonnet, Le Tombeau d’Edgar Poe (The Tomb of Edgar Allan Poe), so beautiful that it seems feeble to honour it only with a sort of panicked horror...

The Tomb of Edgar Allan Poe

Such as eternity at last transforms into Himself,

The Poet rouses with two-edged naked sword,

His century terrified at having ignored

Death triumphant in so strange a voice!

They, like a spasm of the Hydra, hearing the angel

Once grant a purer sense to the words of the tribe,

Loudly proclaimed it a magic potion, imbibed

From some tidal brew black, and dishonourable.

If our imagination can carve no bas-relief

From hostile soil and cloud, O grief,

With which to deck Poe’s dazzling sepulchre,

Let your granite at least mark a boundary forever,

Calm block fallen here, from some dark disaster,

To dark flights of Blasphemy scattered through the future.

...must we not end with it? Does it not make concrete the artificial abstraction of our title? Is it not, in Sibylline rather than lapidary terms, the sole thing worthy of saying on this dreadful subject, at the risk of ourselves also being accursed, o glory! Along with These?

And we will, in fact, content ourselves with this last quotation, which is fine, in the present situation, as well as intrinsically.

It remains for us, as we are aware, to complete the study we have undertaken of Mallarmé and his work! What a pleasure that will be to us, brief duty though it must prove!

All (worthy of the knowledge) know that Mallarmé has published, in a splendid set of editions, L’Après-midi d’un Faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) a sultry fantasy in which the Shakespeare of Venus and Adonis might have inflamed the fieriest of Theocritean eclogues; and the Toast Funèbre a Théophile Gautier (Funeral Toast to Gautier) a very noble lament for a very fine master. These poems being publicly available, it seems pointless to us to reproduce them. Pointless and impious. It would be to destroy everything, since the definitive Mallarmé is as one. As well cut the breasts from a beautiful woman!

All (of those mentioned) also know Mallarmé’s fine linguistic studies, his Dieux de la Grèce (The Gods of Greece) and his admirably precise translations of Edgar Allan Poe.

Mallarmé is working on a book whose profundity will astonish, no less than its splendour will dazzle, all but the blind. But when, finally, dear friend?

Let us end here: praise, like the flood, can only attain a certain height.

IV: Marceline Desbordes-Valmore

Despite, in fact, a pair of published articles, a comprehensive one by the marvellous Sainte-Beuve, and a second –

dare we say? – rather too brief one from Baudelaire, even despite a kind of benign public opinion that failed to assimilate her wholly to the outpourings of Louise Colet, Amable Tastu, Anaïs Ségalas, and other blue-stockings of no importance (we forgot Loïsa Puget, also entertaining it seems to those who like such things), Marceline Desbordes-Valmore is worthy by her apparently total obscurity, of ranking among the Poètes Maudits, and it is therefore our imperative duty to speak of her at length and in as much detail as possible.

Monsieur Barbey d’Aurevilly once singled her out among the ranks, and signalled, with that bizarre competence he possesses, his bizarre attitude towards her and the true, though feminine, competence she possessed.

As for ourselves, we, so interested in good or beautiful poetry, were yet ignorant of her work, content with those of the masters, when Arthur Rimbaud, to be precise, knew and forced us to read all that we thought to be a hodgepodge concealing a few beautiful things within.

Our astonishment was great, and demands a few moments explanation.

Firstly, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore was from the North not the South, a nuance more nuanced than we think. From the raw North, the genuine North (the South, the cooked, is always better, but that better especially may be the undoubted enemy of the genuine) – and that pleased us, we of the North, and also raw – ultimately!

No cookery then, but with language and effort enough to reveal her work as interesting.

Quotation will witness to what we might call our sagacity.

In the meantime, should we not return to the total absence of the South from this not inconsiderable body of work? And yet how ardently understood, her Spanish North (but has not Spain a composure, a haughtiness, colder even than all that Britishness?), her North

Where the fervent Spaniards came to dwell!

Yes, none of the emphasis, none of the falseness, nothing of the bad faith one must deplore in the works deriving most indisputably from the Outre-Loire (the historic northern province ‘beyond’ the Loire, the region of the langue d’oui as opposed to the langue d’oc). And yet how warm they are, these romances of youth, these memories of the age of Woman, these maternal tremors! And sweet, and sincere, and all of that! What a countryside! What love of that countryside! And that passion so chaste, discreet, yet so strong and moving!

We have said that Marceline Desbordes-Valmore’s language is adequate, we ought to have said perfectly adequate, only we are such a purist, such a pedant we may add, for we are said to be decadent (a term of abuse, in parentheses, picturesque, very autumnal, a sunset glow in sum) that a certain naïvety, a certain ingenuousness of style, sometimes roused the prejudices of a writer aiming at the impeccable. The truth of our self-correction will be brought to light in the course of the quotations we are about to lavish upon you.

For the strong but chaste passion we indicated, the almost excessive emotion we praised, falls short, it must be said, of excess, no? After a ruthless reading, prompted by consciousness of our previous paragraphs, we retain our opinion of her.

And the proof I find here:

A Woman’s Letter (Une Lettre de Femme)

Women should not write, and that fact I know,

Yet I am writing,

That my heart you may read while distant, so,

As if in parting.

I will trace not a thing that will not prove

Finer in you,

Yet a word said a hundred times, from one we love,

Seems fresh and new.

May it bring you happiness, which I await,

Though ‘over there’

I feel I walk, and hear and contemplate

Your wandering air.

And turn not away if a swallow briefly

Brushes the sand,

Believe it is I, sweeping past faithfully,

To touch your hand.

You go, and everything goes! All is voyaging,

Flowers and light;

Fair summer follows you, leaving me weeping

In storm-filled night.

Yet if one must live only on hopes and fears,

Ceasing to see,

Let us part for the best; I’ll restrain my tears.

Hope on, for me.

No, I’d not long to see you suffer, since I

Am one with you,

Nor, wishing my better half to grieve and sigh,

Hate myself too.

Is that not divine? But wait:

Oriental Day (Jour d’Orient)

That was a day! Like the beautiful one

That set love ablaze, to see all undone.

It was a day of divine charity

Where, in blue air, walks eternity

Where, disrobed of stifling weight,

Earth plays, and becomes a child elate.

It was like a mother’s kiss, in its power,

A dream long astray in ephemeral hour,

The hour of birds, and fragrance, and light,

Of forgetting all things...in unequalled delight!

................................................

That was a day, like the beautiful one

That set love ablaze, to see all undone.

We must restrain ourselves, and reserve our quotations for poems of another order.

Before passing on to examine harsher ‘sublimities’, if it is permitted to so describe some of the work of this adorably sweet woman, let us, with tears literally in our eyes, recite this to you from her pen:

Renunciation (Renoncement)

Forgive, Lord, my face, of all happiness bereft...

For you have set tears beneath the joyful brow:

And of your gifts, Lord, only one is left.

The least envied, and yet the best, so it appears.

I no longer have to die among things flowering,

All are returned to you, dear author of my being,

And I own no more than the bare earth of my tears...

Flowers for the child; salt for the woman, a briar:

Form innocence, and dip it in my days.

Lord, when this salt has bathed my soul, entire,

Return me a heart, to love you with always.

All on earth that might surprise, is past for me.

My farewells made, the soul is ready to leap

To reach its fruits, protégés of mystery,

Dead modesty alone dared gather, and not keep.

O Saviour! Be tender to mothers, ease their fears,

Out of love for yours, and pity, thus we entreat.

Baptise their children with our bitter tears,

And raise mine again, fallen at your feet.

How this sadness surpasses the ‘Sadness of Olympio’, and that of ‘To Olympio’ (see the poems ‘Tristesse d’Olympio’ and ‘À Olympio’ by Victor Hugo) however beautiful those two proud poems, especially the latter, might be! But rare readers, forgive us, at the threshold of other sanctuaries of that church of a thousand chapels, the work of Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, for chanting with you, after you:

May my name be only a sweet shadow, in vain,

May it never give rise to fearfulness or pain,

May some poor soul take it, after speaking with me,

And hold it, in their heart, consoled, for all eternity?

Do you forgive us?

Now let us pass on to the mother, the daughter, the young daughter, the troubled but sincere Christian who was the poetess, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore.

We have said that we will try to speak of the poet in all her aspects. Let us proceed in due order, giving as many examples as possible. Here then, firstly, are a few much-truncated examples of the young Romantic of 1820, a superior Parny, different in form while remaining singularly original.

Disquiet (L’ Inquiétude)

What troubles me then? What do I await?

Sadness in town, ennui in the village,

All the finest pleasures of my age,

Save me not from the tedium of time.

Formerly friendship, the fruits of study,

Filled my days of quiet and leisure,

Oh! What’s the object of my vague pleasure?

I seek and I scorn it, unquietly.

If I found no joy in such happiness

I no more found it in melancholy.

Yet, between tears and lunacy,

Where now shall I find felicity?

.....................................

She then addresses ‘Reason’, both adjuring and abjuring it, in so kindly a manner! While, we admire, for our part, this monologue in the style of Corneille, and more tender than Racine, but noble and proud in the style of those two poets, though in a wholly different way.

Amongst a thousand things of a gentleness, somewhat sentimental, but never bland, and forever surprising, we beg you to receive in this swift survey a few isolated lines to tempt you towards the whole:

.....................................

Conceal me, your gaze full of soulful sadness.

.....................................

One resembles delight in a flowery hat.

.....................................

Inexplicable heart, an enigma to yourself...

.....................................

In my serenity you see delirium only.

.....................................

...feeble slave that you are, listen anew,

Listen, Reason absolves, and pardons, you.

Render her tears at least! Will you yield entire?

Alas no! Forever no! Oh, to all, let my heart, aspire!

As for La Prière Perdu (The Lost Prayer), a work of which those few lines form part, we make honourable amends for our over-use of the word gentleness, employed but an instant ago. With Marceline Desbordes-Valmore one often knows not what to say or think, her genius stirs one so delicately, an enchantress herself enchanted!

If anything speaks of passion, as well expressed as in the finest elegiacs, it is this, or we know naught of the matter.

And how to praise enough the friendship, so pure, the love so chaste, of this proud yet tender woman, except to counsel you to read all her work. Listen further to these two small fragments:

Two Loves (Les Deux Amours)

A love it was more playful than tender,

My heart was brushed by its unforced caress,

It was as light as is a smiling falsehood;

.........................................

Offering joy, without talk of happiness.

.........................................

It is in your eyes I see that other love.

.........................................

This complete, and utter, self-forgetfulness,

This need to love, for love’s sake alone,

Which the word love can barely express

Your heart contains, and my heart can divine,

I feel, by your passion, my fidelity,

That it means happiness and eternity,

And that its power is indeed divine.

Two Friendships (Les Deux Amitiés)

There are two friendships, just as love is two,

And the one, resembling imprudence,

Is a child, ever-full of laughters new.

And all the charm of a friendship between two young girls is thus divinely described.

..........................................

Then...The other is graver and more severe,

Granted slowly, chosen mysteriously, here.

..........................................

Always scattering flowers, fearful of being hurt.

..........................................

It sees with Reason’s eyes, and on her feet is borne,

It awaits its hour, and never may forewarn.

Hear the note of gravity already sounding.

Alas, if only we were not limited by the need to conclude our study! What wonderful and congenial locales! What landscapes, those of Arras and Douai! What riverbanks, those of the Scarpe! How sweet, and quite strange to us (we know what we intend, and you comprehend us) are those young Albertines, those Inès, those Ondines, that Laly Galine (Her childhood friends, and her sister) that exquisite ‘lost land of beauty, lost cradle of childhood, pure air of my verdant country, be blessed, oh, sweetest place on Earth.’

We must therefore restrict ourselves to the just (or rather, unjust) limits that cold logic imposes on the dimensions desired for our little book, our meagre review of a truly great poet. But – but! – how shameful to seek only to quote fragments like these, written long before Lamartine became known, and which are we insist, those of a Parny, chaste and utterly peaceful, his superior in this tender genre.

Lord, how late it is! Wonder anew!

Like a lightning-flash, time fled there.

Twelve times the bell trembled in air,

And here I’m still sitting by you.

And far from waiting for sleep to come,

I thought I could yet see a ray of sun.

Can the bird be already at rest in the hedge!

Ah! It’s still far too lovely for sleep!

......................................

Be sure to let our sleeping dog lie.

He might not know it’s his friend, and so of my

Imprudence my mother he’ll tell.

......................................

Listen to reason, let go of my hand;

For, it’s midnight now...

It’s chaste, that ‘let go of my hand’, yet it’s loving that ‘it’s midnight now’ following on the ray of sunlight she thought she could see!

Let us quit the young girl, sighing! The woman we have viewed previously, and what a woman! The friend, O, the friend! The lines on the death of Madame de Girardin!

Death has closed the most beautiful eyes in the world.

The mother!

When I’ve scolded my son, I hide, and I weep.

And when this son goes to college, a dreadful cry is it not?

The candour of my child, how they’ll destroy it!

What is least known of Marceline Desbordes-Valmore are those adorable fables, truly hers, after the bitter Lafontaine, and the pretty Florian:

A tiny little lad was sent off to school;

They said: on your way! And he tried to obey.

............................................

And ‘The Fearful One’ (Le Petit Peureux) and ‘The Little Liar’ (Le Petit Menteur) Oh! We implore you, read all these gentle things, neither bland nor affected.

If my child loves me today

sings ‘The Sleeper’ (La Dormeuse) which means, here, ‘The Lullaby’ (La Berceuse) how much more preferable!

Then God himself will say

I love this sleeping child,

Grant him golden dreams and mild.

But, after noting that Marceline Desbordes-Valmore was first among the poets of her time to employ, with the greatest felicity, unusual metres, the eleven-syllable line among others, very artistically and without being over-conscious of it, which was all to the better, let us sum up our admiration by quoting this admirable work:

The Sobs (Les Sanglots)

Ah! Hell is here! The other troubles me less.

Though Purgatory’s the heart’s unquietness.

I have heard too much for that funereal name

Not to coil about the feeble heart, nor there remain.

And as time’s flood erodes me, hour by hour,

Purgatory I see, such is my pallor’s dower.

If they speak true, we must suffer that place,

Lord of all life, ere we may see your face.

There, without moon or sun, we must move,

Under the weight of fear, and the cross of love,

Hearing the condemned souls by sighs riven,

Unable to say: ‘Go now! You are forgiven!’

And sobs and tears penetrating everywhere,

Unable to dry the tears; O, care upon care;

A clashing at night from the caged cells, that lie

Where no dawn lights them with its clear eye.

Not seeing where to cry to the Saviour unknown,

Alas, my sweet Saviour, are you not come?

Ah, I fear the fear itself, and the cold; I hide,

Like the fallen bird, we aid, trembling inside.

I sadly open my arms again at the memory...

And yet I feel it near, it is Purgatory.

It’s there I dream of my dead self, alway,

Like a slave, error-filled, at the eve of day,

Hiding her pale lined forehead in her hand,

Crushing the heart beneath, in that bruised land.

It’s there, to meet my own self, that I remove,

Not daring to wish for those whom I love.

I’d have naught of charm then, in my heart,

But the far echoes that the living start.

Heaven! Where must I go

Without feet on which to run?

Heaven! Where knock although

I own no keys, not one?

The eternal judgement, deaf to my prayer,

What sunlight will reach my sad eyes there,

To cleanse them of everything, each fearful sight

That causes my dolorous gaze to lower in fright.

No more sun! Why? That beloved light

Still saves the wicked here from eternal night;

Over the convict to the scaffold led

It sheds its sweet ‘Come to me’ upon his head.

No birds above! No warm hearth anywhere!

No more ‘Ave Maria’ on the gentle air!

At the dry lake’s edge, no quivering reeds!

No air to support a living creature’s needs!

Fruit that quenches the ungrateful believer,

No longer serving there to cool my fever!

And from my absent heart that shall yet oppress me,

I’ll garner those tears that will ne’er flow from me.

Heaven! Where must I go

Without feet on which to run?

Heaven! Where knock although

I own no keys, not one?

None of those memories that fill me with tears,

So alive to me they near quench my fears.

No family that nigh the hearthside keep,

Singing to grandfather to bless his sleep.

No beloved bells that, with invincible grace,

Force nothingness to sound being and place;

No more sacred books like leaves from the skies,

Concerts my senses hear through my eyes.

Not to dare to die when one no longer dares to live,

Nor seek a friend in death that might salvation give!

O parents, why are your flowers cradled so,

When the sky curses plants and trees below?

Heaven! Where must I go

Without feet on which to run?

Heaven! Where knock although

I own no keys, not one?

Who leans to the soul beneath the cross, forlorn,

Punished when dead for the sin of being born!

But what, in this death that feels its expiration,

If some far cry spoke of hope and expectation;

If in the darkened sky some pale star

Sent light to my melancholy from afar;

If under arched rows veiled in shadowed misery,

Troubled eyes yet lit with concern for me?

Oh, it would be my mother, intrepid and benign,

Descending to reclaim her daughter, at a sign!

Yes, it would be my mother in God’s mercy

Who from that dire place were come to save me,

And would the canopy of fresh hope bring,

To her last fallen fruit, gnawed by suffering.

I would feel her lovely arms so soft and strong,

Clasped in her powerful embrace, borne along;

I would feel the flow, over each nascent wing,

Of the pure air that sends the free swallows gliding,

And my mother fleeing, no more returning,

Would bear me on into the future, living!

And yet, before departing that deathly land,

We would go clasp our companions by the hand,

And by the funeral field, where for many a year

I’ve planted flowers, bathe, in the scent born of each tear.

And we shall have voices there, of ecstasy and flame,

Crying ‘Will you come, now?’, summoning them by name,

‘Come, to that fair summer, where all things flower again,

Where we love without weeping, nor dying of our pain?

Come, and behold your God! For each one is his dove;

Throw off your shrouds, no more tombs, in the heavens above,

The Sepulchre is shattered by the eternal kiss,

My mother bears us, once more, to an eternal bliss!’

Here the pen falls from our hands and pleasant tears dampen our illegible scrawl. We feel powerless to further analyse the work of such an angel!

And pedant that we are, such being our pitiful profession, we shall proclaim in a loud, and intelligible, voice, that Marceline Desbordes-Valmore is, along with George Sand (who is so different, harder, though not without a charming lightness, great good sense, a proud and so to speak male allure) the only woman of talent and genius in this century, and all centuries, worthy of the company of Sappho perhaps, and that of Saint Theresa.

V: Villiers de l’Isle-Adam

‘One should write for the whole world...’

‘What does just treatment matter to us, then? He who does not, at birth, bear within himself his own glory, will never know the meaning of the word.’

These words taken from the preface to La Revolté (The Revolt, 1870) express the whole of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, the man and his work.

An immense, but justifiable, pride.

An entire Paris, the literary and artistic one, somewhat nocturnal and rightly nocturnal, lingering more over fine debate than the joys lit by the intimacy of gaslight, knows, and though it may not like him, admires this man of genius, and perhaps fails to like him much because it is forced to admire him.

A mass of greying hair, a broad face which is seemingly there to enhance the magnificent lively eyes, a regal beard and moustache, frequent gestures, a thousand miles from being without gracefulness, but sometimes strange, a disturbing conversationalist, suddenly convulsed, by some hilarity, that gives way to the most beautiful intonation in the world, a slow calm bass, that suddenly modulates to contralto. And always such verve, as restless as it is possible to be! Dread sometimes mingles with his paradoxes, a dread which one might say the speaker shares, then a wild laughter shakes speaker and audience alike, bursting forth with fresh spirit and comic strength. All essential opinion, and nothing that cannot fail to interest the mind, passes by, borne on this magical flow. And Villiers goes, departing like some dark mist in which, at the same time, a memory seems to linger in the eye, of some firework, some series of flashes, of lightning or the sun!

The work is as hard to render and realise as the Workman, who is met with often, while the work seems exceedingly rare. By that we mean almost impossible to locate, since, due as much to his disdain for celebrity as for reasons of supreme indolence, the gentleman poet has preferred lonely glory to banal publicity.

He began, as a youth, with superb verses. Only, seek them out! Seek out Morgane (Morgana), Elën, dramas seldom known among the great dramatists; go seek out Claire Lenoir, a novel unique in this century! And the others, and the conclusion of Axël, of L’Ève Future (The Future Eve), of masterpieces, pure masterpieces, the writing of them interrupted for years, continually resumed like cathedrals or revolutions, as noble as they.

Happily, Villiers promises us a grand edition of his complete works, in six volumes, and those – very soon!

Although Villiers has already won Great Glory, and his name is destined to gain the profoundest resonance with endless posterity, nevertheless we class him among the Poètes Maudits, because he is Not Glorious Enough in this age which should fall at his feet.

But, hold! Since for us, and many fine spirits, the Académie Française – which has granted Leconte de Lisle the armchair of the celebrated Victor Hugo, which Hugo had, nonetheless some sort of poetic greatness, speaking frankly – since the Académie owns to good and better writers, and since the immortals beyond the Pont des Arts have, at last, instituted, thus, the tradition of one great poet replacing another – Hugo following on from the considerable poet who was Népomucène Lemercier, who himself replaced we no longer know whom – then who could follow the Classical and ‘Barbarous’ poet, Leconte de Lisle, after his death, which we hope will be long delayed, if not Monsieur le Comte de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, recommended, to all those dukes, firstly by his grand and noble title, then above all by his immense talent, his fabulous genius, besides his being a charming fellow, an accomplished man of the world, without the disadvantageous propensity of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam for saying anything and everything?

Now let us quote, and a fine quote it is, namely the ‘silent scene’ from La Révolte.

The clock above the door strikes one in the morning, sombre music; then, between fairly long silences, two, then two-thirty, three, three-thirty, and finally four. Felix remains in a swoon. Dawn light enters through the windows, the candles extinguish themselves, a candle-ring shatters, of its own accord, the fire dies down.

The door at the rear opens violently, Madame Elisabeth enters trembling and dreadfully pale; she holds a handkerchief to her mouth. Without seeing her husband, she goes slowly to the large armchair near the fireplace. She throws down her hat, and forehead in hands, with fixed gaze, sinks into the chair and begins to indulge in reverie, in a low voice. She is cold; her teeth chatter, and she shivers.

And then Scene X of Act Three of Nouveau Monde (New World) where, after the eloquent and spiritual expression of the grievances of the financial backers from England and America, all speak together, as indicated by page-long curled brackets, eliminated here to meet the requirements of our text.

Effie, Noella, Maud reciting a psalm: ‘Super flumina Babylonis (By the waters of Babylon...)

The Officer standing on the stepladder behind Tom Burnett and, with loud volubility, dominating their chanting of the psalm...

You are late, Sir Tom! It is the due date. You are definitely late. You made several agreements with the German explorers: to the value of one hundred and sixty-three thalers, which they pronounce dollars...

(The sound of birdsong in the trees)

Effie, Maud, Noella more loudly ‘sedimus et flebimus (we sat down and wept...)

The Officershouting in Tom Burnett’s ear... and with the merchants from Philadelphia! They are well within their rights to demand payment too. As for the industrial operations, here is the schedule of payments...

The Cherokee seated on his barrel.

Drink wine! Very good! Syrup of flowering maple!

The Quaker Eadie reading in a loud voice.

When noon is past the birds re-awaken. They resume their hymns and everything in nature....

(The dog barks)

Lieutenant Harris pointing to Tom Burnett.

Silence! Let him speak!

An American Indian speaking confidentially to a group of black Americans.

If you see bees, white men are coming, if you see the bison the Indian follows.

Mr. O'Keene to a group.

They say fearful things happened in Boston. Imagine that...

Tom Burnett beside himself, to the officer.

Late! Ah that, but that’s my problem! There’s no reason for all this to end. Tax the air I breathe! Why not arrest me, at the corner of the woods, right now? Have I lived only to see this? It’s scarcely worth striving to become an honest man! I positively prefer the Mohawks!

(Furiously, towards the women)

Oh! That psalm!

(Monkeys swing in the lianas. – Translator’s note: geographical confusion. Scene X is set in Virginia.)

A Comancher aside, gazing at them.

Why did the Great Spirit (Translator’s note: spiritual/religious confusion regarding the Comanche Nation) set the red-skinned people at the centre and the white people all around?

Maud in a single breath, her eyes on the heavens and pointing at Tom Burnett.

How eloquent is the Holy Spirit!