Jean Moréas

The Manifesto of Symbolism (1886)

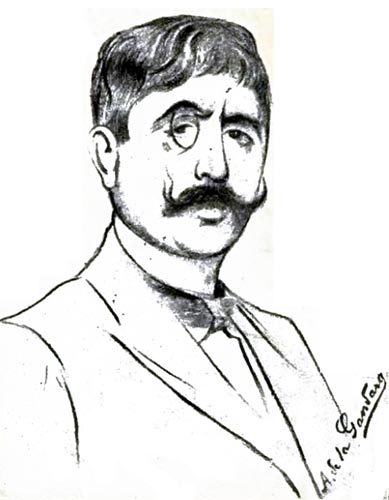

Jean Moréas by Antonio de La Gandara

Wikimedia Commons

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

For two years, the Paris press has busied itself with a school of poets and prose writers called ‘decadent’. The storyteller of ‘Thé chez Miranda’ (in collaboration with Mr. Paul Adam, the author of ‘Soi’ ), the poet of ‘Les Syrtes’ and ‘Les Cantilènes’, Mr. Jean Moréas, one of the most prominent among these literary revolutionaries, has formulated, at our request, for the readers of the Supplément, the fundamental principles of this new manifestation of art.

Le Figaro, Saturday, September 18th, 1886

Symbolism: by Jean Moréas

Like all the arts, literature evolves; in cyclical evolution, with strictly determined phases, complicated by various modifications brought about by the passage of time, and the upheavals of society. It would be superfluous to point out that each new evolutionary phase of art corresponds precisely to the senile decrepitude, the inevitable end of the school immediately preceding it. Two examples suffice: Ronsard triumphed over the last imitators of Marot; Romanticism unfurled its banners above those classical ruins ill-defended by Casimir Delavigne and Étienne de Jouy. Every manifestation of art meets with fatal impoverishment and exhaustion; then follow copies of copies, imitations of imitations; what was new and spontaneous becomes cliché and commonplace.

Thus, Romanticism, having sounded all the tumultuous alarm-signals of rebellion, its days of battle and glory over, lost strength and grace abdicated its heroic audacities, became restrained, sceptical and full of common sense; in the honourable and tentative narrowness of the Parnassians, it sought false revival, then finally, like some monarch lapsing into childishness, it allowed itself to be deposed by Naturalism, to which one cannot seriously accord a greater value than that of protest, legitimate but ill-advised protest, against the blandness of certain novelists then in fashion.

A new manifestation of art was then awaited, one both necessary and inevitable. That manifestation, long incubated, has now hatched from the egg. And all the anodyne mockery of the most playful amongst the press, all the anxiety of serious critics, all the ill-humour of the public, startled from its sheep-like placidity, does no more than to affirm each day the vitality of the present revolution in the French literary world, an evolution which hasty judges have termed, unbelievably and paradoxically, decadent. Note, however, that decadent literatures reveal themselves to be essentially leathery, stringy, timorous and servile: all Voltaire’s tragedies for example are marked with these incrustations of decadence. And what is this new school to be reproached for, what is it indeed reproached for? An abuse of splendour, a strangeness of metaphor, a new vocabulary in which harmony is combined with colour and line: characteristics of all rebirths.

We have already proposed the name of Symbolism as the only term capable of truly designating the present thrust of the creative spirit in art. The name may stand.

It has been said at the beginning of this article that the evolutions of art possess a cyclical character, frequently complicated by divergence: thus, to follow the precise ancestry of the new school, it would be necessary to return to certain poems of Alfred de Vigny, even as far as Shakespeare, to the mystics, or still further. Such investigations would demand a whole volume of commentary; let us say then, that Charles Baudelaire must be considered as the true precursor of the present movement; Monsieur Stéphane Mallarmé endows it with a sense of the mysterious and ineffable; Monsieur Paul Verlaine threw off, in its honour, the cruel shackles of verse, which the noble hand of Monsieur Theodore de Banville had previously loosened. However the Supreme mystery is not yet achieved: an effort, both stubborn and jealous in nature, is demanded of the newcomers.

✯✯✯

The enemy of didacticism, declamation, false sensibility and objective description, symbolic poetry seeks to clothe the Idea with a sensory form which, nevertheless, should not exist as an end-in-itself but as a form which, though serving at all times to express the Idea, must remain subjective. The Idea, in its turn, must not be allowed to be deprived of the sumptuous robes of external analogy; for the essential character of symbolic art consists in its never leading to the concentration of the Idea in itself. Thus, in this art, scenes of nature, the actions of human beings, all concrete phenomena are not there to manifest themselves; they are sensory appearances intended to represent an esoteric affinity with primordial Ideas.

The accusation of obscurity launched against such an aesthetic by readers, in a desultory way, is no great surprise. But what can one do? Have not Pindar’s Pythian Odes, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Dante’s Vita Nuova, Goethe’s Faust, and Flaubert’s Temptation of Saint Anthony, been taxed also with ambiguity?

For an exact interpretation of its synthesis, Symbolism must adopt an archetypal and complex style; of unpolluted vocables; of a period that supports the line, alternating with a period of falling undulations; of significant pleonasms; of mysterious ellipses; the anacoluthon in suspense; all daring and multiform; ultimately, superb expression – established and modernised – the superb, and luxuriant, and exuberant French of a Vaugelas a Boileau-Despréaux, the language of François Rabelais and Philippe de Commines, of Villon, of Rutebeuf and so many other writers freely firing the fierce darts of language, as the Thracian Toxotai their sinuous arrows.

Rhythm: the old metric sharpened; a skilfully-ordered disorder; rhyme set gleaming, hammered like a shield of gold and brass, beside rhyme of abstruse fluidity; the alexandrine with multiple and movable stops; the use of certain prime numbers – seven, nine, eleven, thirteen – set in various rhythmic combinations of which they are the sums.

✯✯✯

Here I ask permission to involve you in a little Interlude derived from a precious book: The Treatise on French Poetry, where Monsieur Theodore de Banville, like Apollo, the god of Claros, mercilessly sets the monstrous ears of a donkey on the head of Midas.

Your attention!

The Characters on stage in this piece are:

– The Detractor, a person critical of the Symbolist school

– Monsieur Theodore De Banville

– The Muse Erato

Scene I

The Detractor Oh! These decadents! What self-importance! What a show of utter nonsense! How right the great Molière was when he said:

‘That mannered style, of which conceits are made,

Abandoning virtue, with scant truth displayed.’

De Banville Our great Molière penned two bad lines, which, themselves, are as distant from virtue as possible. What virtue? What truth? Apparent disorder; dazzling intemperance; passionate emphasis, are the very truth of lyric poetry. To depend upon excessive figures of speech or upon colour; such evils are not great, and it is not from these that our literature will perish. In the worst periods, when it died utterly, as for example under the first Empire, it was not emphasis, or the abuse of ornamentation, that killed it; it was the descent into platitudes. Taste and truth to nature, are fine things, but assuredly less useful than one thinks in poetry. Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is written, from beginning to end, in a style as affected as that of the Marquis de Mascarille in Molière’s own Les Précieuses; while that of Jean-François Ducis, adapter of Shakespeare, shines with the happiest and most natural simplicity.

The Detractor But the caesura, the caesura! They violate the caesura!!

De Banville In his remarkable Prosody of the Modern School, published in 1844, Monsieur Wilhelm Ténint establishes that the Alexandrine verse admits twelve different combinations, beginning with the line which has its caesura after the first syllable, and ending with the line which has its caesura after the eleventh syllable. That is to say, in fact, that the caesura can be placed after any syllable of an Alexandrine line. In the same way he establishes that lines of six, seven, eight, nine, ten syllables admit variable and variously placed caesuras. Let us do more: let us dare to proclaim complete freedom and say that with regard to such complex questions the ear alone decides. One perishes, always, not from having been too bold, but from not having been bold enough.

The Detractor What horrors! Not to respect the alternation of rhymes! Do you not know Monsieur that the decadents even dare to permit the hiatus! Even the hiatus!!

De Banville The hiatus, the diphthong as a syllable in the line, and all the other things that have been forbidden, and above all the optional use of male and female rhymes, have furnished the poet of genius with a thousand kinds of delicate effects always varied, unexpected, and inexhaustible. But in order to deploy this complicated and learned verse, genius and a musical ear were needed, whereas with fixed rules, the most mediocre writers can, with loyal obedience, forge, alas, passable verse! Who has gained anything from the regulation of poetry? Mediocre poets; and they alone!

The Detractor It seems to me, however, that the Romantic revolution...

De Banville Romanticism was an incomplete revolution. What misfortune, that Victor Hugo, a victorious Hercules with bloody hands, was not a revolutionary at all, and that he allowed a horde of monsters to live on, all of whom he had been charged with exterminating by use of his fiery arrows!

The Detractor Any attempt at such revolution is crazy! The imitation of Victor Hugo; why, there lies the salvation of French poetry!

De Banville When Hugo had freed verse, it must have been thought that, instructed by his example, the poets who came after him would wish to be free, and independent. But such is the love of servitude in us that the new poets copied and imitated Hugo’s most habitual forms, combinations and striking images, instead of trying to find new ones. It is thus that, fashioned for the yoke, we revert from one form of slavery to another, and that after the clichés of Classicism, came those of Romanticism, clichés of imagery, clichés of phrasing, clichés of rhyme; and the cliché, that is to say the commonplace when it becomes a chronic state, in poetry, as in everything else, is Death. On the contrary, let us dare to live! And to live is to breathe the air of the heavens and not the breath of our neighbour, even if that neighbour were a god!

Scene II

Erato (invisible) Your Little Treatise on French Poetry is a delightful work, master Banville. But these young poets drown in blood to the level of their eyes, as they fight against the monsters shepherded together by Nicolas Boileau; you are summoned to the field of honour, yet you are silent, master Banville!

De Banville (the dreamer) – Malediction! Could it be I have failed in my duty as their elder and as a lyric poet!

(The author of Les Exilés utters a lamentable sigh, and our interlude ends.)

✯✯✯

Prose – novels; short stories; tales; fantasies – evolves in a sense analogous to that of poetry. Elements, seemingly heterogeneous, contribute to it: Stendhal brings his translucent psychology, Balzac his exorbitant vision, Flaubert his cadences of phrasing with their ample volutes. Monsieur Edmond de Goncourt his impressionism, in the suggestive modern manner.

The conception of the symbolic novel is polymorphous: sometimes a single person moves in a social ethos deformed by his own hallucinations, his temperament; in this deformation there lies the sole reality. Beings with a mechanical gesture, with shadowy silhouettes, flicker around this unique character; they are mere excuses for sensation and conjecture. He himself is a tragic mask, or a buffoon, but an embodiment of humanity, however, that though perfect is rational. – Sometimes crowds, superficially affected by the gathering of representations surrounding them, drive themselves, through alternating conflict and stagnation, towards acts which remain incomplete. At times, their will as individuals is manifested; they attract each other, mass together, become generalized for a purpose which, achieved or lost, disperses them to their primitive elements. – Sometimes evocations of mythical phantasms, from ancient Demogorgon to Belial, from the Cabiri to the Necromancers, appear in ostentatious fashion on Caliban’s rocky isle, or in Titania’s woods, to the Mixolydian modes of barbitons and octachords.

Thus, disdainful of the puerile methods of naturalism – Monsieur Zola himself was saved by a wonderful writer’s instinct, namely the symbolic novel – the impressionist will build upon his work of subjective deformation, fortified by this axiom: that art can only find in the objective a simple, and extremely limited, point of departure.

Jean Moréas.