Guillaume de Lorris

The Romance of the Rose (Le Roman de la Rose)

Part I: Chapters I-VI

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter I: The Lover’s prologue

- Chapter I: He awakes within the dream.

- Chapter I: He follows the river

- Chapter II: The Garden, and the Images on its wall

- Chapter II: Hatred

- Chapter II: Felony and Villainy

- Chapter II: Covetousness

- Chapter II: Avarice

- Chapter II: Envy

- Chapter II: Sorrow.

- Chapter II: Age

- Chapter II: Hypocrisy

- Chapter II: Poverty

- Chapter II: He seeks a way into the Garden

- Chapter III: Lady Idleness

- Chapter III: The Garden of Pleasure

- Chapter III: He enters the Garden

- Chapter III: The choir of birds

- Chapter III: Pleasure and his company

- Chapter IV: Joy

- Chapter V: The carole or round-dance

- Chapter V: The figure of Pleasure

- Chapter V: The figure of Joy

- Chapter VI: The God of Love

- Chapter VI: Love’s five golden arrows

- Chapter VI: Love’s five black arrows

- Chapter VI: The figure of Beauty

Introduction

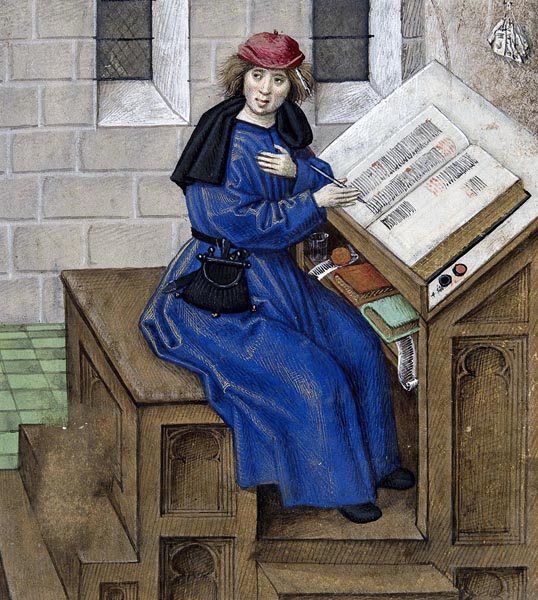

‘The Author’

Jean de Meung (c1240-c1305) wrote a long continuation (dated to between 1268 and 1285 by internal references) to this, the original Roman de la Rose. Jean claimed that it had been conceived by Guillaume de Lorris (c1200?-c1240?) some forty years earlier. Guillaume, it is presumed, came from the village of Lorris, near Orléans, in France; otherwise nothing is known of his life. Clearly he was educated and literate, and therefore likely to have been of the minor aristocracy. He produced in this Romance a dream allegory of courtly love, in a poetic, reflective and elegant style, but his world-view is also shrewd, with his reflections on love partly derived from Ovid’s Ars Amatoria: The Art of Love. Here Guillaume’s work is allowed to stand free of the later work, as an epitome of the allegorical style and a fine development of the courtly tradition of ‘fin amour’.

Chapter I: The Lover’s prologue

It is the Romance of the Rose

That doth the art of Love enclose.

MANY men say that in our dreams

There are but lies and idle themes;

And yet a man can dream such dreams

As are not lies, rather, it seems,

Their meaning, later, becomes clear.

We may invoke as witness here,

Macrobius who did not deem

All things mere folly seen in dream,

When he wrote about the vision

That to Scipio was given.

Though whoe’er believes, or says,

That tis mere foolishness, always,

To think such dreams can come to pass,

May call me a poor fool at last,

If he so wish, nonetheless I

Believe a dream may signify

The good or ill that visits men;

For, at night, in sleeping then,

Many do dream much covertly,

That’s later seen quite openly.

In my twentieth year of age

When Love, at that early stage,

Exacts its tribute, I, one night,

Laid me down, as any might,

And fell into a slumber deep,

And saw a vision in my sleep,

So lovely that it gave delight.

Yet there was naught in the sight

That failed to prove as true, at last,

As in the dream it came to pass.

Now I would that dream relate,

In rhyme, your hearts so to elate,

As Love begs me, nay commands.

And if any, of me, should demand

What I would name this Romance,

That I commence, and so advance,

It is the Romance of the Rose,

That doth the art of Love enclose.

Tis fine and new, all I conceive,

And may God grant that she receive

This with grace for whom I labour,

For she is so filled with honour,

And so worthy of love, that same,

Rose indeed should be her name.

Chapter I: He awakes within the dream

‘The Beginning of the Dream’

I was aware that it was dawn,

Five years ago at least; a morn

In May it was, or so I dreamed;

The time of love, for so it seemed,

The season when all things delight,

Bush and hedgerow shine bright,

With the fresh leaves they display

Thus seeking to adorn the day;

And the trees regain their verdure,

Branches stripped bare by winter;

While the very ground joys too,

Sweetly moistened by the dew,

And all that poverty now gone,

Which it suffered winter long.

Then so proud the earth doth grow

That it would have a fresher robe,

And knows how to form a dress

A hundred pairs of colours bless,

Of grass and flowers, in grey-blue,

Violet, and many another hue;

Such indeed is the robe I mean,

In which the earth would preen.

The little birds which were dumb

While the winter-cold did numb,

In that season, harsh and bitter,

Now, with May’s calmer weather,

Show their pure delight in song;

Pleasure in their hearts so strong

They must perforce sing aloud.

Then the nightingale is proud

To sound its notes, and rejoice,

Then the lark will find its voice;

And like the rest, on joy alight.

So too must young folk delight

In pleasure, and prove amorous,

In that season sweet and joyous.

Hard his heart who loves not in May,

When the birds their hearts display

In their sweet and moving song.

In that lovely season among

All things stirred thus by love

I dreamed that night I moved,

For I was aware in my sleep

The world did full morning keep,

And so I had risen from my bed,

Dressed, laved my hands and head,

Drawn a needle of silver, in haste,

From a fine little needle-case,

And threaded the needle, for I

Longed from the town to fly,

To hear the little birds singing,

Setting all the branches ringing,

In the freshness of the season.

So I stitched my sleeves in fashion,

And went wandering, quite alone,

Listening to the sweet birds’ tone,

For they full-throated so did sing,

Among the gardens flourishing.

Chapter I: He follows the river

JOYFUL, happy, with ne’er a sigh,

I turned towards the river, for I

Heard it murmuring quite near;

And I knew of naught so dear

Than the joy beside that stream,

Which descended, in my dream,

Deep and wide, from out the fell,

As clear and cold as from a well,

And noisy as a fountain; and then,

Twas little smaller than the Seine,

But spread more widely in its flow.

Not one so lovely did I know;

It filled my heart with delight

To gaze upon so sweet a sight,

So fine its course, so fair the place.

As I refreshed and cleansed my face,

In that clear and shining water,

I saw that all its bed, the deeper

Part, was cleanly paved with gravel.

The meadow, fair, wide and level,

Spread right to the river’s border.

Clear and pure, was the weather

And the morning, mild and fine.

So I walked; the path all mine,

Wandering along, downstream,

Following the bank, in my dream.

Chapter II: The Garden, and the Images on its wall

Here doth the Lover recall

A set of images on the wall,

Of the garden, which he saw;

And is pleased again to draw

Their figures; and how they appear,

And their names you will hear.

The figure he is first to name,

Is Hatred then, the very same.

‘Hatred’

AS I advanced, the stream beside,

I found a garden, long and wide,

Closed by a wall, strong and tall.

Sculpted and painted on it all,

Many a portrait did it bless;

These portraits and images,

I most willingly did admire;

And I will tell to you, entire,

Of these portraits all the semblance,

As they come to my remembrance.

Chapter II: Hatred

NOW in their midst, Hatred I saw,

Who seemed as one that, before

All others, stirs anger and strife;

Wrathful and quarrelsome in life,

Full of malice toward each thing,

Was her portrait, in its seeming.

Nor was she in a pleasing state,

But like one ever-enraged, irate,

Frowning and sullen was her face,

The nose squat; all without grace,

Wrapped in a foul cloth was she,

That clung to her most hideously.

Chapter II: Felony and Villainy

‘Felony’

ANOTHER form, of the same height,

I saw there, to Hatred’s right;

By her head, her name I did see,

And she was entitled Felony;

While on Hatred’s left, I saw,

Villainy made one portrait more,

Of the same aspect as those two,

And full as hideous to the view,

The same foul, repugnant nature;

She seemed indeed an ill creature,

Poisonous, spiteful, and malicious,

Ever slanderous, ever vicious;

And whoe’er such forms had made,

He knew well the artist’s trade,

For she seemed a villainous thing,

Full of rancour, and ill-speaking,

A woman indeed who little knew

Of honour, where honour was due.

‘Villainy’

Chapter II: Covetousness

‘Covetousness’

NEXT was shown Covetousness,

She who tempts men to possess;

Forever to take, and never give;

Gain wealth, but neglect to live.

Tis she who presses, with usury,

Many a man; her desire, you see,

To win, gain, and heap together.

Tis she who doth robbers gather,

And incites those rascals to crime,

Such that to their sorrow, in time,

Many then, for their sins, will hang.

Tis she who seeks, without a pang,

Others’ goods, through thievery,

Fraud, miscounting, and deceit.

Tis she who stirs false litigation,

And every form of vile vexation,

Until, like lambs to the slaughter,

Sees the heirs, a son, a daughter,

Forced to court, in a lost cause.

Curved, and hooked like claws,

Were the hands of this image,

As is but right; for in a rage,

Is Covetousness to acquire.

Covetousness has no desire

But to take what others own,

Holding such things dear, alone.

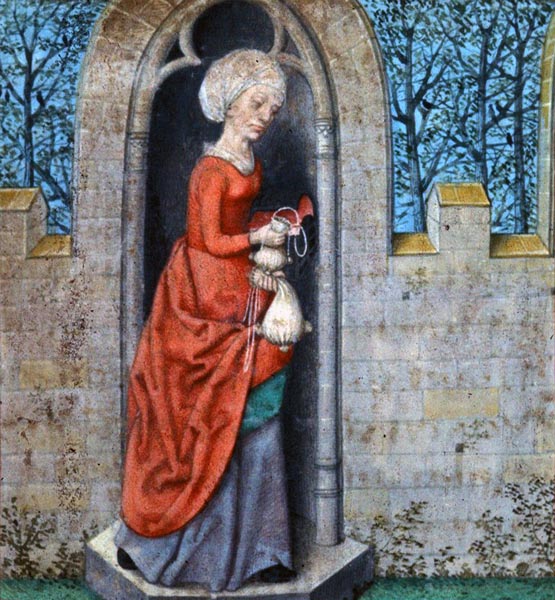

Chapter II: Avarice

‘Avarice’

ANOTHER image I did address,

Seated there, by Covetousness;

Avarice was she named, and she

Was ill-formed, all foul and ugly,

An image of leanness, yet alive;

Though she was green as any chive,

For so unhealthy was her colour,

She appeared half-dead of languor,

A thing reduced to skin and bone,

As if she’d lived on bread alone,

Bread that tasted harsh and bitter.

As well as being thin and meagre,

A threadbare coat did she have on,

That oft among the dogs had gone,

Old and tattered, shabby, poor;

Both behind her and before

For every patch, there was a hole;

Beside her hung, upon a pole,

Set nearby, all torn and thin,

A mantle made of gabardine,

Without a trace of ermine there,

Lined with black; a poor affair

Of lamb’s wool, coarse and heavy;

Her dress was old, a good twenty

Years, at least, for Avarice

Is ever slow to change her dress;

And heavy upon her it did fall

That she must wear a dress at all;

When twas worn and old, that dress,

Avarice would know great distress

Before she’d have another made,

And her new dress was displayed.

Avarice was holding in her hand

A purse, which, you’ll understand,

Was half-concealed, knotted tight,

So that twas long before she might

Draw aught at all from it, for she

Has naught to do with such, you see;

And would regard it as a curse

To take a penny from that purse.

Chapter II: Envy

‘Envy’

NOW Envy was the next portrayed.

Who never laughed in all her days,

Nor e’er enjoyed a single thing

Unless she heard that it did bring

Some poor creature to their knees;

Nor is there anything doth please

Her like ills, and misadventure,

And when she sees discomfiture

Fall upon some noble creature,

From it she derives much pleasure.

She rejoices with all her heart

When some great house falls apart,

And sinks from honour to shame.

And then, if any man wins fame,

If he doth sense or prowess boast,

Tis the thing that wounds her most.

For, know that it doth suit her best

To be angered by others’ success.

Envy’s so filled with cruelty,

That she doth bear no loyalty,

To company, or companion,

Nor kin however close, for none

But ever remains her enemy.

No good doth she wish to any,

Not even her father, or her mother,

But know that she yet doth suffer

A heavy cost for her ill intent,

For she endures much torment

If men do good deeds, for she

Doth well-nigh melt with anxiety;

Her wicked heart tears her in two,

Thus God and men take vengeance too.

Envy lives not one hour, again

Without blaming blameless men,

And I believe that if she knew

Of the noblest man, fine and true,

This side, or that side, of the sea,

He would yet know her enmity.

And if he were so free of blame

That she could not that man defame,

Nor rob him of the world’s esteem,

She would still long to demean

Him, his prowess and his honour,

And by her words him dishonour.

And I saw Envy, as portrayed,

Her own sad ugliness displayed;

And naught there is she doth view

Except obliquely, and untrue;

Tis an ill habit she doth show,

For she cannot, you must know,

Gaze at a person true and plain,

But shuts one eye in pure disdain,

For she burns and melts fierily,

When anyone that she doth see,

Is noble, fair, or courteous

Or is loved or praised by us.

Chapter II: Sorrow

‘Sorrow’

BY Envy, and not far from her,

Sorrow was portrayed, her colour

Seemed to show that, in her heart,

Some great sadness worked its art.

She was tainted, as if by jaundice,

For it seemed that even Avarice

Was not so gaunt and colourless.

Twas all the trouble and distress,

And the weight of sore dismay,

That she suffered night and day,

Had turned her yellow and stale,

Rendering her so thin and pale.

None born knew such suffering,

Nor was such pain in anything,

As seemed thus to arise in her.

I think none could devise for her

Aught that might give her pleasure;

Indeed, she appeared to treasure

The sorrow dwelling in her heart,

Nor, for aught, from it would part.

Her heart was in too great annoy,

And buried in the depths all joy.

She was shown in deep mourning;

All unable to keep from tearing

At her face, her clothes no less;

With her hands she’d ripped her dress,

Like one consumed by dismay;

Her hair too fell in disarray,

Where she’d torn at it wildly,

And down her neck it fell free,

Tangled by her behind, before,

In discontent, and blind furore.

And know that she wept profusely;

None is so hard-hearted, truly,

That they would not, on seeing her,

Have pitied how she did suffer,

How at herself she struck and tore,

Beat at her flesh till it was sore.

Much was she bent on stirring grief,

This poor wretch, of joy the thief,

Who took no interest in pleasure,

Nor kiss or embrace would treasure;

For one who has a grieving heart,

Knows, in truth, they lack the art

For dancing or for carolling;

Nor can one who sorrows bring

Themselves to caper joyfully,

For grief and joy are contraries.

Chapter II: Age

‘Old Age’

NEXT was Old Age pictured there,

Now shrunken by a foot, I swear,

From the height she used to be;

So old and withered now was she

She could scarce feed herself at all,

Her beauty wasted and, in its fall,

A thing of ugliness she’d become,

Worn and lined, scarred and numb.

Her hair was now as white, I’d say,

As if it had been decked with may.

No great loss were it if she’d died,

Nor a great wrong, for age had dried

Her flesh, left her but skin and bone;

Now was her face that of the crone,

Wrinkled o’er and withered where

It had once shown smooth and fair.

Her ears were mossy; to her cost,

All her teeth were long time lost,

Such that not one tooth remained.

Of such great age she complained,

That without her stick she’d never

Totter twenty feet together.

Time that runs, by night and day,

Without a pause, without a stay;

Who quits us all so secretly,

To steal away, it seems, that he

Remains in place, and yet he goes,

And never finds the least repose,

And still doth never cease to fly;

So none can say, and nor can I,

When the present moment is;

For not the wisest clerk there is

Can, in thought, seize it at last,

Before three others have gone past;

Time, who can thus linger never,

But goes, returning not, forever,

Like water flowing, running on,

Ascending not once it has gone;

Time before which nothing stands,

Not steel, nor any work of hands,

For it wastes all, doth all consume;

Time that doth new forms assume,

And nourishes, and raises all,

And then consumes it in its fall;

Time that aged our ancestors,

That ages king and emperors,

And will now age us all as well,

Unless our life death doth expel;

Time, with the power, we are aware,

To age all folk, had so aged her,

And cruelly, that, it seemed to me,

She could not help herself, but she

Lapsed to second childhood, there,

For she’d no more strength, I swear,

Than a child of two, nor the sense

That it doth own, in its innocence.

Yet nonetheless it seemed to me

She had been wise, and most nobly

Made when she was in her prime;

Yet was no longer wise; for time

Had robbed her now of her reason.

She was well-clothed, for the season,

As I recall, with a fur-lined coat,

Against the cold, from feet to throat.

Old people shun the cold, you know,

Since tis their nature to feel it so.

Chapter II: Hypocrisy

NEXT there was an image traced,

That false religion there embraced,

The figure’s name, Hypocrisy.

Tis she that, in deep secrecy,

When no man is watching, still

Ne’er hesitates to work her ill.

Without, she’s modest and humble,

Her aspect both quiet and simple,

And she seems a saintly creature;

Yet there’s no wickedness in nature

She does not think on in her heart.

Here she was captured well, in art,

Which was made in her semblance;

She seemed of humble countenance,

And she was both clothed and shod

As one who’d given herself to God.

And in her hand she held a psalter,

And know that she, before the altar,

Rendered up many a false prayer,

And called on all the saints there.

She sought not pleasure and content,

But rather did appear intent

On performing good works entire,

A hair-shirt showing her desire.

And know she was not fat indeed,

It seemed she fasted, by the Creed.

Her colour too was deathly pale.

The gate to Paradise she shall fail

To win and all her ilk, for they

The Gospel says, who do betray

Their faces, and render them thin

And pale for praise, commit a sin,

And all for some slight vainglory,

That God will judge but transitory.

Chapter II: Poverty

‘Poverty’

THE last I saw was Poverty,

And not a single coin had she,

To buy a piece of rope to hang her;

Nor could sell the robe about her,

She was near naked as a worm;

If the season had taken a turn

For the worse, she’d have died of cold.

She’d but a sack, both thin and old,

Full of patches, a mantle and coat,

Likewise patched and patched about,

And nothing else had she to wear,

But leisure enough to shiver there.

She was a little apart from the rest,

And like a dog in the corner, at best,

Crouching there, and cowering,

For, where’er it may be, anything

That’s poor is forever despised.

Cursed be the hour that was devised

In which the poor man was conceived!

His hunger ne’er shall be relieved,

Nor shall he be clothed and shod,

Loved, or nurtured, except by God.

Chapter II: He seeks a way into the Garden

ALL these images I gazed at near,

For, as I have described them here,

They were done in azure and gold,

Painted along the wall, full bold.

High was the wall itself and square,

In lieu of a hedge, enclosing there

A garden, where no shepherd came

With his flock to mar the same.

This garden was set in a fair place.

Any who’d led me within, apace,

By means of a ladder or a stair,

Had known fair thanks, I declare.

For never such joy or such delight

Saw any man, I’ll answer quite,

As in that garden he might see.

That place of winged minstrelsy,

Was not some poor barren niche;

Ne’er was there any place so rich

In trees, so full of birds in song;

Three times as many were among

The branches as in all of France.

Fair harmonies they did advance;

So sweet their singing in the air,

That all the world in it should share.

And for my part I so joyed to hear

Their lovely song anoint my ear,

I’d not have ta’en a heap of gold,

To turn away from that sweet fold,

An if the way had been open wide,

To view, praise God, the birds inside,

That sang there, so melodiously,

And in such a charmed assembly,

The dance of love, in all its notes,

Prettily, from their sweet throats.

Hearing their harmonious singing,

I was almost mad with longing

Wondering what device or art

Might serve to penetrate its heart.

But nowhere could I find a place

Of entry, not one single trace;

For, know, I nowise knew, I say,

Of an opening, or passage-way

Through which I readily might go;

Nor was there any there to show

The means, for I was all alone,

Much distressed, and did groan;

Till I bethought me there was no

Fair garden made in this world so,

Without a door, to pass thereby,

Or opening, or ladder on high.

So I then advanced in haste

Making a compass of the place,

All about the square enclosure,

Until I found a fair embrasure,

A little gate, narrow and tight.

It was there alone a man might

Enter, so I knocked loudly there,

For I saw no other way to fare.

Chapter III: Lady Idleness

Here Lady Idleness, however,

Opens the door to the Lover.

I’d knock awhile and hammer there,

And then I’d listen out with care,

For any sound, such was my scheme.

Then the gate, which was hornbeam,

Was opened by a noble lady,

She both courteous and lovely.

Her hair was of a copper shade,

Skin tender as a bird, the maid,

Arched eyebrows, shining brow,

The space between her eyes, I vow,

Not short but full wide in measure;

Her fine straight nose, a treasure;

Brighter than a hawk’s her eyes,

To rouse pure envy in the unwise;

Her breath was savoury and sweet;

And red and white did both compete,

In her face; slender mouth, not thin;

And there was a dimple in her chin;

Hers was a well-proportioned neck,

As fine and slender as is correct,

Without a blemish, unmarred its stem,

Nowhere, from here to Jerusalem,

Lived a woman with a neck so fine;

Softly and smoothly, it did shine.

Her throat and breast were as white

As snow that on the branch alights,

When tis new-fallen and undimmed.

Her body was well-made, and slim;

You would not find, not anywhere,

A woman with a form so fair.

She’d a chaplet inlaid with gold;

There was never a girl, all told,

More elegant, or better arrayed,

For me to describe that maid,

Would take a lifetime, I know;

And then she was robed just so.

Above the gold inlaid chaplet

A chaplet too of roses was set.

In her hand she held a mirror.

A rich headband she did favour

Binding the tresses of her hair,

Tightly, her tresses fine and fair.

Her sleeves were tightly laced and she

Wore pure white gloves to keep

Her white hands from the burning sun.

Her coat, cord-stitched, was done

In a rich green cloth of Ghent.

It seemed then that, to all intent,

She had but little work to do,

For when she’d combed her hair through,

Adorned herself, and made all neat,

Her day’s task was quite complete.

Hers was fine weather, ever May,

Without sad sighing or dismay;

Naught troubled her, except to be

Attired most nobly and graciously.

Chapter III: The Garden of Pleasure

‘The Garden of Pleasure’

ONCE this most-gracious lady

Had opened then the door for me,

I thanked her kindly and did demand

Her name; she answered my command,

Politely, for she was not haughty,

Nor any disdain showed for me,

But spoke to me with fair address:

Saying: ‘I am called Idleness,

By all those who chance to know me;

I am a rich and powerful lady.

I have a pleasant time always,

For I think of naught for days

But to seek out joy and content

And make my coiffure elegant:

When I’m adorned, and am neat,

My day’s task is quite complete.

I am the intimate acquaintance

Of Pleasure, that elegant man,

Who is the owner of this garden.

He from the land of the Saracen,

Had the trees brought to this place,

And planted throughout the space.

When the trees were fully grown,

Pleasure had the high wall thrown

About them and outside the glade

Had all those images portrayed

You may have chanced to view, which far

Less elegant and charming are,

But rather sad and dolorous,

As you have seen, most unlike us.

Many a time thus, seeking leisure

To this cool shade comes Pleasure,

And of his followers no small few,

Who live in joy and comfort too.

He is within somewhere, no doubt,

The song-thrush carols hereabout;

He doth his ears perchance regale

With the singing of the nightingale.

Here he finds delight and solace,

With his people; a finer place

And a better spot for joyful play

He would not find, for many a day.

And all the fairest folk, you know,

You might seek, where’er you go,

Are the companions of Pleasure,

Who leads and guides them at his leisure.’

Chapter III: He enters the Garden

WHEN Idleness had told me all

She wished, and I had heard it all,

I spoke thus: ‘Lady Idleness,

Leave off all doubt, for I confess,

If Pleasure, the noble and the fair,

Is in company with his folk there,

Within the garden, that gathering,

I’d not fail, if I could, of joining,

For I must view it, or feel annoy,

To see it, I my thoughts employ,

For lovely is that company,

And wise and full of courtesy.’

Chapter III: The choir of birds

NOT one word further did I say,

But into the garden, straight away,

I went, by the door that Idleness

Had opened; full of happiness,

Joy, delight, at what met my eyes;

For it seemed an earthly Paradise,

So delectable was all that place.

I felt it was by the spirits graced;

And, so I deemed, not anywhere

Could there be a Paradise so fair

To wander in, on this earth below,

As that garden that pleased me so.

There were singing birds aplenty,

Gathered there beyond its entry.

In one place were nightingales,

Starlings and jays in other vales,

Elsewhere were crowds above,

Of warblers and of turtledoves,

The goldfinch, and the swallow,

The robin and the wren below.

Calandra larks were massed there,

Weary of singing through the air,

Despite themselves, on the wing;

The blackbird flew, the redwing,

And the thrush, seeking to outdo

The other birds with its song too.

I heard the sparrows singing there,

And many a bird that, in the air,

And in the glades and groves around

Joyed in its harmonious sound.

A sweet service they performed,

Those birds, the choir they formed,

For they sang songs so beautiful

They seemed angelic, spiritual.

Know, in truth, as I did employ

My hearing so, I filled with joy,

The melodies, so sweet, so clear,

Ne’er heard before by mortal ear.

It seemed, so beautiful, so sweet,

Twas more than birdsong, complete;

Rather one might the song compare

To Sirens singing through sea-air,

Whose sighs, serene as that same,

Gave them Sirens for their name.

They were intent upon their song,

Those birds, ne’er a note fell wrong,

For they were skilful thus, and wise;

Hearing those creatures of the skies,

Seeing the green leaves all around,

I was right joyful at the sound,

Such that there was none who knew

Such delight, for I filled anew,

With joy, in the air’s sweet balm,

So delectable that garden’s charm.

And then I saw how Idleness

Had served me well, so to bless

And set me there in such delight;

My love was due to her, of right,

Opening the door, that I might be,

Of that green branched garden free.

Chapter III: Pleasure and his company

NOW shall I tell of this affair,

As best I can, what I did there.

First of what Pleasure performed,

And of the company he’d formed;

Not making of it too long a tale,

Yet the true manner, I shall regale

You with, of the garden; moreover,

Putting the whole thing in order,

Not speaking it all in one wise,

So that none here may criticise.

A fine service, sweet and charming,

Those birds flew about performing,

Fine love lays, and elegant songs,

And each in its own pleasant tongue,

One singing high, and another low,

Nor did I scorn to listen below.

The sweetness and the melody

Saw my heart lost to reverie.

But after a while there listening,

I could not refrain from seeking

As to where Pleasure might be,

For I had a great longing to see

All his diversions and his being.

So I turned to the right, straying,

Along a path, well-nigh a tunnel,

Full of the scent of mint and fennel,

And there with Pleasure, I did meet,

For I entered into a quiet retreat,

Where he was on leisure intent,

Spending his time in sweet content;

And a host of folk with him, so fair

That I knew not, seeing them there,

Whence folk so lovely might arise,

For indeed it seemed, to my eyes,

They were winged angels, in verity,

And no man born ere saw such beauty.

Chapter IV: Joy

Here the Lover speaks of Joy;

She is a lady, who doth employ

Herself, willingly, in the dance,

And here a carole doth advance.

‘Dancing’

THESE folk, of whom I do tell,

Were all dancing, in a circle,

And a lady sang to the same,

And Joy, in truth, was her name:

She sang right well and pleasantly,

And none sang more agreeably,

Or more sweetly, to her refrain.

She knew all that art, twas plain;

She had a voice, pure and clear,

One never unpleasing to the ear.

And she well knew how to wheel

In true enjoyment, raise her heel.

She was the first, in every court,

To start a song, as custom sought;

For singing was the thing you see,

That she would do most willingly.

And you’d have seen that company

Sing the carole and dance daintily,

And with many a dance-step pass,

And many a turn, on the green grass.

The flute-players, you’d have seen,

Jongleurs and minstrels too, I wean.

One played a song with a refrain,

Another a sweet air from Lorraine,

For in Lorraine they have more airs,

Than realms greater than is theirs.

And there were tumblers, girls too,

Leaping about, and jugglers who

Struck and sounded the tambourine,

Hurled it high, and then were seen

To catch it, as it did downward sail,

In their strong fingers, without fail.

Two young maids, both elegant,

Pleasure guided in the dance,

In short dresses, upon that spot,

With hair all braided in a knot;

But tis in vain to speak of how

Elegantly they danced, I vow.

One, she advanced most prettily,

Toward the other, then she and she,

Nearing, almost seemed to touch

Their lips together, and kiss as such.

They knew the art of dancing well;

While I know not how of it to tell.

Yet I would ne’er leave them though,

As long as I might watch them so;

Those folk so lively in the dance,

Who in their carole did advance.

Chapter V: The carole or round-dance

Here the Lover tells the manner

Of the carole, danced together,

And how he met with Courtesy,

Who addressed him, amorously;

Revealing all the countenance,

Of those people, and their dance.

GAZING on, I stood there, still,

Watching all this carole until,

I was noticed by a noble lady,

And her name it was Courtesy,

The most worthy and debonair;

Whom may God keep in His care!

Then Courtesy called out to me:

‘Fair friend, what is this I see?

Come to me now,’ said Courtesy,

‘And join the carole, tis my plea.’

So without an instant’s delay

I joined the carole, and away

I was swept, amongst the dancers,

Making not the worst of prancers.

And know then that I was pleased

When Courtesy my arm did seize,

And made me join the carole there,

For I was longing, if I’d but dared,

To join the carole, show my paces.

And now I looked upon the faces,

The forms and fashions all around,

The expressions and manners found

Among the dancers on that floor,

And I shall tell you all I saw.

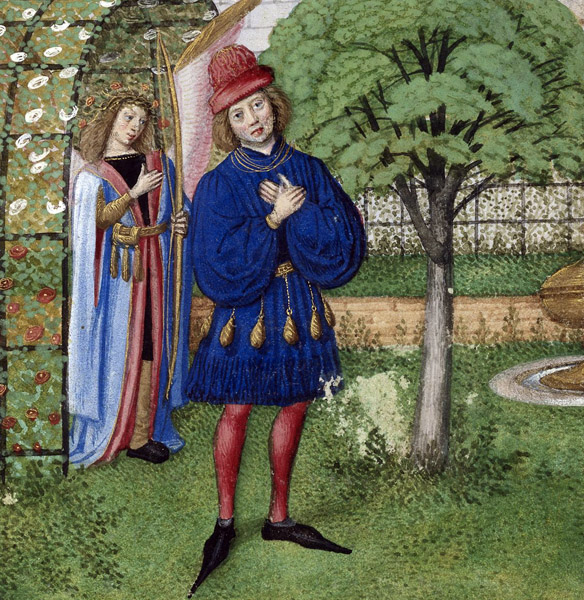

Chapter V: The figure of Pleasure

PLEASURE was fine, tall and straight,

Ne’er, in this world, at any rate,

Shall you find a more handsome man.

His face was like an apple, not wan,

Scarlet and white its hue combined;

Elegance, beauty in him refined.

Bright his eyes, the lips noble;

The nose well-formed, agreeable;

The hair that fell in curls, was blonde;

The shoulders both broad and strong;

Yet he was narrow about the waist,

So well-formed, so full of grace,

So elegant he seemed a creature

Much like a piece of portraiture;

And yet vigorous too, and lively,

A more agile man you’ll not see.

He’d neither beard nor moustache,

Except of the palest down a dash,

For he was but a youth, I swear,

Yet a rich samite did he wear,

All decorated with beaten gold,

And little birds adorned each fold.

His dress indeed thus ornamented,

Slashed, or cut away, presented

The tailor’s art in its every line.

And his shoes too were most fine,

Low in cut, and skilfully laced.

And his lover, of her good grace,

Had a crown of roses made, you see,

Which became him wondrously.

Chapter V: The figure of Joy

DO you know who was his lover?

Joy, who hated him not, moreover;

The lovely girl, the sweet singer,

Whom Pleasure held by a finger,

Who at only seven had given her

Promise he should be her lover.

She held him in the same way too,

In the dance; well-suited those two,

He was handsome, and she was fair.

She seemed a new-blown rose there

In colour, with her skin so tender,

Only a little thorn would rend her.

Her forehead was gleaming white,

For smooth it showed in the light.

Her eyebrows were arched, brown,

Her eyes bright, and such joy found

Within them, they danced awhile,

Before her lips did chance to smile.

Of her nose, what shall I tell you?

None of wax was ever more true.

A tiny mouth she had moreover,

Twas ever ready to kiss her lover.

Her hair was blonde, and it shone.

What more should I say thereon?

She was lovely, and well-dressed,

Golden thread adorned every tress;

A new chaplet embroidered in gold,

Had she, and twenty-nine, all told,

Have I seen, but never, of that ilk,

Saw one so finely worked in silk.

All richly clothed was her body,

In samite, all worked similarly;

Pleasure was likewise endowed,

A favour of which she was proud.

Chapter VI: The God of Love

Here are those beauties expressed,

In which the God of Love is dressed.

‘The God of Love’

ON the other side, and close to her,

Was the God of Love, who doth confer

Love-gifts according to his desire;

He governs lovers; all that choir.

He it is humbles human pride,

When he finds us haughty inside,

Reduces lords to common men,

And ladies to mere maids again.

The God of Love in his bearing

Was no boy, but older-seeming;

His beauty great; as to his dress,

I fear that I may be hard pressed

To describe his robe for, I recall,

His clothes were not silk at all,

Rather he wore a robe of florets,

Of love-gifts, fair mignonettes,

With lozenges, and little shields,

Lion-cubs, beasts of the fields,

Leopards, and little birds there,

Scattered about it everywhere,

Worked too with many flowers

In a sweet diversity of colours.

Flowers of many kinds did I see,

And all were placed most skilfully.

No flower in summertime is born

But did that robe of his adorn,

As broom, sweet-violet, periwinkle,

In yellow, purple, white did twinkle,

And mingled there, on every side,

Rose-petals too, long and wide.

He wore a rose-chaplet on his hair,

But the nightingales circling there,

As they flew above and around,

Scattered the petals on the ground.

He was surrounded by the birds,

Finches, calandra-larks I heard,

Warblers, and he, so beautiful,

Seemed as if he were an Angel

And had descended from the sky.

Amor had a young man close by,

Who was ever beside that same,

And Sweet-Glances was his name.

He guarded, as the dance did flow,

The God of Love’s two Turkish bows.

One is made of wood from a tree

Whose fruit tastes bitter; I did see

It was all knots and burls below,

And above, was that savage bow,

And it was as black as mulberry.

Such was the first that I did see;

The other, long, of noble fashion

Was in some smooth wood done,

Well-made, and well-presented,

And it was finely ornamented,

Fair ladies on it were portrayed,

And elegant young men, inlaid.

These two bows Sweet-Glances kept,

While his master nobly stepped,

And ten arrows too he clasped.

In his right hand five he grasped,

And every nock and every flight

Was well-made, and set aright;

And each was painted all in gold.

Strong and sharp, the points told,

Piercing deep, and nor were they

Of iron or steel, for in that array

The tips were solid gold; the rest

Painted to suit, feathers of the best,

Truest shafts, but those bare points

Barbed for those whom Love anoints.

Chapter VI: Love’s five golden arrows

‘Love’s Five Golden Arrows’

OF those the fairest and the best,

The swiftest, and the loveliest,

The finest feathered of those same,

That shaft has Beauty for its name.

That which most wounds the sense,

I think it is called Innocence.

Another Openness they call,

And that shaft was feathered all

With valour and with courtesy.

The fourth is Close-Company,

A shaft so heavy in its flight

It may not far from home alight,

But whoe’er fires it with near aim,

May, in truth, great damage claim.

The fifth is named Fair-Seeming;

Though less harmful, in its gleaming,

Many a deep wound it doth deal;

Yet good grace its wounds reveal,

For good may come of all that ill,

And so fair health may be restored,

And through it sorrow may be cured.

Chapter VI: Love’s five black arrows

FIVE shafts there were in other guise,

Ugly as aught one could devise,

Their shafts, and their tips as well,

Black as any demon from hell.

The first arrow was named Pride;

The second with it, close allied

And worth no more, was Villainy,

And that vile arrow by felony

Was all empoisoned, and tainted;

Shame the third, blackly painted;

And the fourth, Despair its name,

Inconstancy, ne’er twice the same,

Was the last of the five; they strike

Those five shafts, that seem alike,

In like manner, and they all seem

Well-suited in their hellish theme

To the most hideous of the bows,

Its knots and burls, those arrows.

Yet those five too are necessary

For their true power is contrary

To the other five, all in their fall.

But not as yet shall I tell you all

Of their power and their strength.

Though I will tell you, at length,

The truth, and their significance,

Nor shall forget; in my romance,

With their meaning I shall regale

You all, ere I do end my tale.

Chapter VI: The figure of Beauty

NOW to my theme I shall return,

Of the noble folk you must learn,

All their manners in the dances,

Their aspects and countenances.

The God of Love was in company

With a lady of rare nobility,

And she danced beside him ably,

And her name, it too was Beauty;

Like that one of the five shafts she

Owned many a goodly quality.

Not black-haired, nor dark-eyed,

She was fair as the moon, beside

Which the distant stars that tremble

Seem each like a little candle;

Her flesh was tender as the dew;

As innocent as a bride and true,

White as a lily-flower was she;

Her face it was clear, elegantly

Smooth, and straight, and thin,

No rouge or painting did it dim;

Of adornment she’d no need,

No decoration there, indeed;

Her tresses blonde, and so long

They fell her dancing feet among.

Nose, eyes, mouth all made with art;

Great sweetness doth touch my heart,

God save me, when I remember

The fashion of her every member,

And none in all the world so fair;

Young and blonde and, I declare,

Neat and graceful, frank and teasing,

Slender but firm, noble yet pleasing.

The End of Part I of the Romance of the Rose