Jean de Meung

The Romance of the Rose (Le Roman de la Rose)

The Continuation

Part VII: Chapters LXX-LXXIV - The Crone’s Lament and Advice

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter LXX: The Crone brings Fair-Welcome the youth’s gift.

- Chapter LXXI: The Crone’s lament.

- Chapter LXXII: The Crone teaches a perverse view of Love.

- Chapter LXXIII: The sad tales of Dido, Phyllis, Oenone and Medea.

- Chapter LXXIII: The Crone’s advice on appearance and behaviour.

- Chapter LXXIII: The Crone’s advice to girls on the make.

- Chapter LXXIII: The Crone’s advice on how to despoil a lover.

- Chapter LXXIV: The tale of Venus, Mars and Vulcan.

- Chapter LXXIV: Woman’s natural freedom.

Chapter LXX: The Crone brings Fair-Welcome the youth’s gift

(Lines 13165-13310)

How the Crone tells Fair-Welcome,

To console him in his prison,

All the deeds of his Lover,

And the great grief he doth suffer.

‘SINCE you are noble, brave and wise,

I bring you, much to your surprise,

A thousand greetings now, and more,

Not from some stranger, what is more,

But a courteous lad, all full of grace,

For but now I met him in this place,

As he was going down the street,

And he sends this chaplet to greet

You, wishes that he might see you;

Not another day shall he see through,

Not another day of health shall know,

If that be not your wish also.

God and Saint Foy love him, he said,

Could he but speak to you, he said,

One single time, at his leisure,

Should that also be your pleasure.

He loves life through you only,

At Pavia naked would be gladly,

If he could but grant a measure

Of aught that gave you pleasure.

Nor cares what becomes of him

If he can keep you near to him.’

Fair-Welcome asked straight away

Who it might be that this did say,

Before he’d accept the present,

Uncertain who the gift had sent,

And from what origin it came,

Lest he wish to refuse the same.

And the Crone, with nary a lie,

Told the whole story, by and by.

‘Tis from the young man that you know,

Of whom you heard such talk below,

On whose account you’ve suffered lately,

Since Ill-Talk troubled you greatly,

By placing all the blame on you.

Paradise may his soul ne’er view!

He’s troubled many a good man

But now to the Devil he has gone;

He is dead, and we’ve escaped him,

And his slanders vanish with him,

Not one of which was worth a sou.

We’re free, and if he rose anew,

He would not trouble you again,

Howe’er he sought you to blame,

For I know more than ever he did.

Now believe me, for I do bid

You take this chaplet, wear it too,

Twill comfort the youth if you do,

For he doth love you, doubt me not,

With a true love, all else forgot.

And if he harbours other intent,

He told it not, in any event;

Yet upon him you may rely.

And then you know how to deny

Aught he asks that he should not.

If he plays the fool, he’s a sot.

If he’s no fool, then he is wise,

And him the more I’ll love and prize,

If he’s done naught outrageous.

He’ll ne’er be so discourteous

As to make of you a base demand,

You who do naught on mere command.

He’s truer than any that live,

So those who know him do believe,

And ever to that will testify,

As witnesses, and so will I.

He is well-ordered in his ways;

None born of woman ever says

A bad word of him, or heard such,

Except when Ill-Talk claimed too much.

But all such things are now forgot,

I may say I remember them not,

I no longer recall his malice,

Except I know twas all foolish,

And that wretch did them contrive,

Who proved them not while yet alive.

I know the youth had slain him for it,

If he had known aught about it,

For he’s fine and brave, without doubt,

None’s equal to him hereabout;

He’s of the true nobility,

Surpassing in generosity

King Arthur, or Alexander.

If he had all the gold and silver

That they had at their command,

He’d give with a more open hand

Than they did, a hundred times more;

Gifts that the world could not ignore,

So good a heart lies in his breast,

Had he the riches they possessed.

None can teach him about largesse.

Come, take the chaplet; I confess

Its flowers smell sweeter than balm.’

‘I’faith, I fear twill do me harm,

For I’ll be blamed,’ Fair-Welcome said.

He trembled, started, sighed, turned red,

Then pale again, lost countenance,

As the old Crone made her advance,

And sought to force him to take it.

He dared not stretch a hand to it,

Saying, the better to excuse it,

Twould be better to refuse it,

Though wishing to accept, in fact,

Whate’er might come of such an act.

‘The chaplet,’ he said, ‘is very fair,

But twere better that I went bare,

My clothes burned and turned to ash,

Than that I take it, twere too rash.

For if I do so, what would we

Say then, to fractious Jealousy,

The quarrelsome, for she, I fear,

Filled with anger would appear

To tear the chaplet from my head,

Piece by piece, and strike me dead,

If she did know where it came from;

Or I’d be shut in a darker room

Than ever I have been till now;

Or if I seek to flee, say how

I might, and where I could strive

To hide; she’ll see me buried alive,

If I’m taken after I’ve fled;

While I fear I’ll be as good as dead,

If I’m caught as I try to flee,

For all will rise to hinder me.

I’ll take it not.’ ‘Come, take this same,

For it will bring nor loss nor blame.’

‘And if she asks from whence it came?’

‘Ten or more places I could name.’

‘Yet if an answer she doth demand

What should I say to her command?

If I’m reproached, if blame should come,

Where shall I say I had it from?

For I’ll be obliged then to reply

With the truth, or tell her a lie.

I swear that if she knew, instead

Of prison, I’d be better off dead.’

‘What to tell her? If you know not,

If no better answer you’ve got,

Say that it was a gift from me.

You know she trusts me utterly;

No blame or shame will fall on you,

For anything that I might do.’

Chapter LXXI: The Crone’s lament

(Lines 13311-13598)

How, after the exhortation

Of the Crone, with jubilation,

Fair-Welcome doth the chaplet take,

Risking his life, all for love’s sake.

‘Fair-Welcome, gazing in his mirror’

‘SO Fair-Welcome, thus reassured,

Took the chaplet and without more

Ado set it upon his head.

And the old Crone smiled, and said

That, upon her soul, she did swear

Ne’er was there a chaplet so fair.

Fair-Welcome, gazing in his mirror,

Looked there often to see whether

It showed as fair as she did say.

The Crone, as no one came their way,

None but the two of them were there,

Sitting beside him, gave her care

To preaching at him in this way:

‘Ah, Fair-Welcome,’ she did say,

‘How worthy, fair, and dear you are!

My happy days are distant far,

But yours, my dear, are yet to be.

You’re scarcely out of infancy,

While I must soon, in Age’s clutch,

Support myself with stick or crutch.

You know not what you’ll do, alas,

But I know you’ll be forced to pass

Sooner or later, come what may,

Through the flames, along that way

Where all are burned, and must stew

Where Venus stews her ladies too.

I know you’ll feel her burning brand,

But ere you do so, understand,

Ere the hot bath you enter, there,

I’ll teach you how you may prepare;

For to bathe is most perilous

For any youth not counselled thus,

While if my counsel you receive

A fair harbour shall you achieve.

If I had but been as great a sage,

When I was at your youthful age,

As wise in Love as I am now!

For I had beauty, I avow,

Though now I moan and complain,

To view my face doth give me pain.

From frowning I may not forbear

Remembering the beauty there,

That made the youths skip about,

So greatly did I draw them out,

It was a wonder just to see.

And then I was famed for beauty;

Tales of it went here and there,

How that I was sweet and fair.

To my house flocked many more

Youths than any had seen before.

At night upon my door they knocked

But harsh was I, who kept it locked,

And failed thus to keep my promise,

And twas not seldom I did this,

For I had other company.

They committed many a folly,

At which I did often frown,

For often my door they’d break down,

Or find themselves in such fierce fights,

Through envy, hate, and such delights,

That ere the rest ended the strife,

They’d lose a member, or their life.

If master Algus, Al-Khwarizmi,

Who could calculate so keenly,

If he had taken the trouble,

To come, with every numeral

Of the ten with which he did count,

He’d not have rendered an account

Of all those fierce quarrels, say I,

Howe’er much he did multiply.

Then was my body strong and firm;

Ten thousand might I have earned

Of sterling silver or even more,

But I was foolish, and I am poor.

Young, and fair, foolish and wild,

Ne’er in Love’s school, as a child,

Was I, where one learns the theory;

All I know the practice taught me.

Tis experience hath made me wise,

That all my life I’ve learnt to prize.

Now I’ve been in every battle,

Tis only right that I should prattle

To you, and teach you all I know,

All that I’ve proven to be so,

Tis well to counsel thus the young.

And tis no wonder, by my tongue,

You know naught, nay, not a bean,

For you, my lad, are yet so green.

And then there’s such science in it,

That I would likely never finish

To tell you all I’ve learnt with age.

Never avoid though or disparage,

All that seems ancient now; what’s old

Good sense and manners it may hold.

For, many have proved, as I maintain,

At least in the end, there doth remain

But manners and sense that they own,

However rich they might have grown.

Since manners and sense I did gain,

That I won not without some pain,

Many a fine man I did deceive,

Caught in the net that I did weave.

Yet I too was deceived by many

Ere I comprehended any;

Then twas too late, they’d had their fun!

Then my youth was over and done.

My door that was oft open, I say,

(For it was open night and day)

Was more often tight to the sill.

No one came yesterday, nor will

Today, I used to think, ah woe!

I am doomed to live in sorrow,

My heart should depart in pain!

And when I viewed my door again,

And even myself, at thought of it,

This country I desired to quit,

For I could not endure the shame.

How could I bear it when those same

Still handsome men came wandering by,

And I, once the apple of their eye,

Whom they could never leave alone,

I watched them pass by, with a groan

At their sidelong glance as they progressed,

Though each was once my dearest guest?

There they went passing by me, too,

Thinking I was worth ne’er a sou,

Even those whose hearts I did own,

Calling me a wrinkled old crone;

And much worse to themselves did sigh,

Before indeed they’d passed me by.

And then, my dear and noble child,

None, who has ne’er been reviled,

Or seen great sorrow, none knows

Unless they watch how this world goes,

What great sadness gripped my heart,

When I remembered the grace and art

Of all those sweet words, and caresses,

All those pleasures, all those kisses,

And all those sweet embraces past,

All that had flown away so fast.

Flown? In truth, and without return.

Twould have been better, you will learn,

If I’d been prisoned in a tower high,

All my days, than be born to cry.

God, what sorrow then came to me,

Through my fair gifts that now failed me!

And the remnants that remained,

How sadly of them I complained!

Alas! Why was I born? To whom

Can I thus complain, to whom

But you, the lad I hold so dear?

No other solace have I, I fear,

Than to preach to you my doctrine.

Tis why, fair lad, I did thus begin

To lecture you, so when twas done,

You’d take revenge on every one.

If God please that time doth come,

Why then you’ll recall my sermon.

Know that, as to retaining it,

If, that is, you do now recall it,

You have by reason of your age

A most substantial advantage.

For Plato said, and it is true,

That the memory stays with you

Whatever the lesson may be,

Best, if it’s learned in infancy.

Certain, dear boy, my tender youth,

If my youth were but here in truth,

As yours is now, the vengeance I

Would take on them none dare try

To write down as twould be taken;

Everywhere, if I’m not mistaken,

That I went I’d work such wonders

On them, none would have heard the like,

On all who valued me so lightly,

And vilified me and despised me,

As basely as they did, in passing,

They would pay for my weeping,

For all their pride, and their spite;

No pity on them would alight.

For with the sense that God gave me,

And in this speech you hear from me,

Do you know what I’d do to them?

I’d pluck all they have from them,

Even if that were wrong, indeed,

And on worms I’d make them feed,

And lie naked on dunghills there,

Especially the first whom I did care

For, those who loved most faithfully,

And sought to serve most willingly,

And did serve and show me honour.

Naught would I grant in their favour,

Not a clove, if I could, until,

With their gold my purse I did fill,

And they were gripped by poverty,

And stamped their feet behind me,

And gnashed their teeth in anger too.

But then, regret’s not worth a sou;

For what has gone can’t come again.

There’s no man now I could retain,

With a face so wrinkled that they

See no threat there in its display.

Long ago those rascals told me

So, those rascals who despise me;

Then it was I took to weeping!

Yet, please God, tis still pleasing

To think upon it, to this day,

In such thought I delight alway,

And I feel joy in every member,

When the good times I remember

And all that life of gaiety,

For which my heart yearns so strongly.

My body doth rejuvenate,

Whene’er my youth I contemplate.

Every blessing I feel bar none,

When I think of all I have done;

And then, at least, I’ve had my fun,

Although deceived by everyone.

A young lady ne’er is idle,

When she leads the life that’s joyful,

Especially one who, in her defence,

Thinks but to live at others’ expense.

And then I came into this country,

Where I chanced to meet my lady,

Who has taken me into her service

To guard you here; such is her wish.

May God that keeps and guards us all,

Grant that I guard you well in all!

Your fair behaviour means I should

For certain, that proves naught but good;

Though to do so would prove perilous

Due to your beauty, all marvellous,

That nature has granted to you,

If she had not also taught you

Prowess, sense, valour and grace.

Now we have the time and space

Where we can speak unperturbed

By any fear of being disturbed,

And say to each other, in my view,

More than we were accustomed to.

And I must now advise you fully.

Wonder not if occasionally

I interrupt my speech a little.

For I must say to you that till

This siege began I made no move

To set you on the path of love;

But if involved you now would be,

Then I will show you willingly,

The pathways that I travelled on

Before my beauty all was gone.’

Then the Crone sighed, and did seek

To know if he desired to speak,

Yet then, indeed, did scarcely wait,

Finding that he did hesitate,

And was silent, and did listen,

And so took up her theme again;

For he who, without contradicting,

Says naught agrees to everything;

And to one who’s pleased to hear

It, all can be said without fear.

Then she recommenced her babble,

Like a false crone, old and evil,

Who thought, by her doctrine, she

Could make me lick pure honey

From thorns, and wished me to be

Called friend, but not too lovingly;

So Fair-Welcome told me later

In recounting the whole matter.

If he’d been such as might believe her,

He might have betrayed me to her,

But he was not a traitor there,

Through aught she said in that affair;

This he swore and, scorning her lies,

Assured me twas not otherwise.

‘O fair sweet boy, fair tender flesh,

I teach the games of Love, no less,

So when my lesson you’ve received,

You will,’ she said, ‘be less-deceived.

Live in accord with my sweet art,

For none who has it not by heart

Can survive without selling all.

Now, attend, so you may recall

And comprehend, all that I say,

For I know all the games they play.’

Chapter LXXII: The Crone teaches a perverse view of Love

(Lines 13599-13765)

How the Crone, without objection,

To Fair Welcome gave her lesson,

Such as is taught by any woman

Who cares naught for reputation.

‘The Crone teaches Fair-Welcome’

‘Fair lads, who would delight in love,

With its sweet ills that bitter prove,

All of Love’s commands must know,

But Love himself ought not to know!

And all of them I’d teach, you see,

If twere not visible to me,

That there is in you by Nature,

Of each thing an ample measure

Of what you ought to own, and so,

Of those that you ought to know,

Although there are ten in number,

He’s a fool who would encumber

Himself here with the final two,

Neither of which is worth a sou.

So I will here allow you eight;

For whoe’er of the two doth prate,

Wastes his time and ends in folly;

Teach them not to anybody.

For he who’d have a lover’s heart

“Be generous” knows not love’s art;

And “set its love on but one place,”

The text is false, and false its face.

Amor but lies, fair Venus’ son,

None should believe him, for the one

Who does so will pay most dearly.

As in the end you’ll see, clearly.

Fair son steer clear of all largesse,

Nor keep your heart under duress,

Ne’er set it on a single one,

Nor give or lend it anyone.

No, sell your love is my advice

And always at the highest price.

And make sure that the one who buys

Ne’er wins a bargain, earns the prize.

Let them have naught they do not earn,

Tis better you hang or drown or burn.

And in such things take care that you

Keep your hands from giving too;

Open them swiftly, though, to take.

Giving is but a fool’s mistake,

Unless a little, to win someone,

Whom one hopes to prey upon;

Or if one hopes from such a birth,

To garner more than it was worth,

Such giving, I’ll allow it ever;

Giving is good where the giver

Wins multiples, and thus doth gain.

Who’s sure of their profit, of the pain

And the gift should ne’er repent;

To such a gift I grant consent.

Next I’ll speak of the five arrows,

For the five possess great virtues,

And yet all five wound readily;

Learn how to fire them so wisely

That even Love that great archer,

Never drew his own bow better;

For many a time you fire your bow,

And then do never seem to know

In what place the arrow will land,

Whether far away or near to hand,

For when one fires away at will,

The one that arrow seeks to kill

May not be the archer’s target.

But whoe’er sees you fairly set

Sees you so well-equipped to draw,

There I can teach you nothing more.

And your skill is such, you realise,

That, if God please, you’ll take the prize.

And next, there is no need for me,

To teach you aught of finery,

Of how to adorn your garments,

With ribbons, baubles, ornaments,

To seem of worth to other men;

Such you may dispense with when

You know the little song by heart

You have heard me sing with art,

When I have dallied here with you,

About Pygmalion’s statue.

Take care, dress well, you’ll know, I vow,

More than an ox doth how to plough.

There is no need for you to learn

The trade, yet if your heart doth yearn

For more, well, I will tell you later,

Of the statue and its creator,

If you wish to listen, and ample

The wisdom gained from that example.

And to you this much I can say,

If you’d offer friendship, any day,

To any young man it ought to be

Granted to that young man I see

Who prizes you, but not unwisely.

If you’d offer, do so wisely,

And I’ll find you enough rich men

For you to gain great wealth from them.

Tis good to befriend the wealthy

If their hearts prove not miserly,

And you know how to pluck them well.

Fair-Welcome, as far as I can tell,

May know whom he wishes, if he

Tells each friend no other would he

Know, not for a thousand in gold;

And swears that if he were so bold

As to wish another to command

The Rose, that is in great demand,

Then he’d be rich in gems and gold,

But his heart’s so true, if truth be told,

That none will e’er set there his hand

But one. And were there a thousand,

He must say to each who doth aspire,

“The Rose is yours alone, fair sire.

No other may have a share in it;

God help me, were I to divide it.”

He may so swear, and so flatter;

If he perjures himself, what matter,

God smiles at such oaths as these,

And pardons the deceit with ease.

Jupiter and the Gods all laughed

When Lovers did so in the past;

They often committed perjury

When they loved adulterously.

When Jupiter sought to reassure

Juno, twas falsely that he swore

By the Styx, in a loud voice too;

He but perjured himself anew.

Since the Gods are their examples,

By the saints, convents, and temples,

True lovers may thus falsely swear

With assurance, and nary a care.

But, God love me, what fool is there

Who doth believe what lovers swear?

For their hearts are ever fickle,

The young folk ever mutable

As often the old folk are too,

All lie on oath, as people do.

Now for another truth prepare;

He who is lord of all the fair

Takes his toll wherever he will;

He who finds no joy at the mill,

Hey then, and off to another!

The mouse that runs for cover,

Is in peril if it has no more

Than one bolthole, that’s for sure.

So tis with that woman, no less,

Who of all the market’s mistress,

Since all labour to possess her,

She must take her toll wherever.

For a foolish choice it would be

If after much reflection she

Wished for but a single lover.

By Saint Liphard of Meung, whoever

Sets her love in a single place,

Has a heart unfree, if such the case,

And thus she doth but basely serve.

Truly doth such a woman deserve

Her full measure of pain and woe

Who, loving but one man, doth so.

If comfort he fails to confer,

Then there is none to comfort her,

And they are often failed the most

Whose hearts do of one lover boast.

All men in the end, all do them flee,

When they are bored, and feel ennui,

No woman e’er comes to a good end.’

Chapter LXXIII: The sad tales of Dido, Phyllis, Oenone and Medea

(Lines 13766-14444)

How that Dido, Queen of Carthage,

Because of the villainous outrage

Committed by Aeneas her friend,

With his sword made sudden end;

While Phyllis hung herself rather

Than hopelessly await her lover.

‘The death of Dido’

‘She could not hold him in the end,

Dido, who was Queen of Carthage,

Though to Aeneas every advantage

She had offered; greeted him, poor,

A wretched fugitive, at her door,

Fled from Troy, where he was born,

Clothed him, and did him adorn.

In her great love for him did she

Honour him and his company,

And did his fleet of ships renew,

To serve him, and to please him too.

She gave him, to arouse his passion,

Of her body full possession,

And her city and her riches,

And he swore to his mistress

That he was hers and would be ever,

And that he would leave her never.

Yet scant was her joy, as I said,

For, without leave, the traitor fled

With his ships, far over the sea;

And she lost her life, in misery.

Ere the morrow you understand,

She was dead by her own hand,

The sword she used he gave her.

Dido, thinking still of her lover,

Seeing that love indeed had fled,

Took the naked blade, and led

The upturned point toward her heart,

Into her breast the blade did start,

And then upon the sword she fell;

Of pity doth the story tell.

Whoever saw her do that deed

Unmoved, were pitiless indeed,

Beholding her, Dido, the fair

Transfixed by the sharp blade, there.

Into her body she drove the steel,

So great the sorrow she did feel.

Phyllis too was such another,

Who hanged herself; for her lover,

Demophon, tardily did return,

And broke his oath to her, we learn.

And what of Paris and Oenone,

Who gave him her heart and body,

As he in return gave his to her?

He took back what he did confer,

For on a tree beside the river,

With his knife he carved a letter

Rather than on parchment, I mean,

And yet it proved not worth a bean.

Twas the bark of a poplar tree,

That conveyed his words you see;

He said it would reverse its stream,

The Xanthus, ere he would dream

Of leaving her, and yet, of course,

Xanthus was free to seek its source.

And what of Jason and Medea?

Shamefully did he deceive her,

Though she’d saved him from sudden death

When savage bulls with fiery breath

Came at him, and he thought to die;

Such that he was not wounded by

Their horns, not burnt by their flame;

Yet his word he broke, to his shame.

He was delivered through her spell,

For she charmed the serpent as well,

So that it slept and would not wake,

So strong a potion did she make.

As for the soldiers born of earth,

Leaping forth warlike at their birth,

Who all wished to slay the hero,

When he threw a stone, the blow

Through her enchantment, drove the men

To destroy each other. And then

Through her potion, the stories tell,

He won the Golden Fleece as well.

While she rejuvenated Aeson,

To strengthen her hold on Jason.

No more from him did she require

Than that she be his sole desire.

And that he value her, his lover,

The better to keep faith with her.

Ye he left her, the false trickster,

The disloyal thief, the traitor;

And once she knew, then the children

That she had conceived with Jason

She strangled, in her grief and rage,

Less than sanely, with that outrage,

Forsaking a mother’s pity;

Worse than a stepmother proved she.

A thousand such I might detail,

But it would prove too long a tale.’

Chapter LXXIII: The Crone’s advice on appearance and behaviour

‘IN short, they’re faithless and deceive

These imps, who everywhere achieve

Their wish, so we should do likewise,

Love more than one, if we are wise.

Foolish is she who doth not so,

Many a lover she should know,

And to distraction, if she can,

She should drive them, every man.

If she’s no graces, then acquire them,

And be all the haughtier to them,

All those men, who would deserve

Her love, so they more truly serve;

And gather the more from all those

Who lightly do their love dispose.

Let her know games and songs to suit,

And flee from quarrel and dispute.

If she’s not lovely, she should dress,

Even the ugliest, to impress;

And if she finds her tresses suffer,

(A great sorrow to any lover)

The blonde hairs falling from her head,

Or if they must be trimmed instead

Because of some dire malady,

And she be shorn of her beauty,

Or if some rascally lover

Has torn them away in anger,

Such that she can do naught at all

Her lovely long hair to recall,

Why, then let false strands be brought,

Hair from some dead woman sought,

Or soft pads of light-coloured silk,

Shaped to fit her, aught of that ilk;

Above each ear then wear a horn,

That goat, or stag, or unicorn,

Could not with their horns surpass,

Not if they burst their brows, alas.

And if they need a little colour,

She should dye them with a smatter

Of plant-juice, and there’s good in fruit,

In wood and leaf, in bark and root.

Next, if her complexion suffers,

Which also grieves the heart of lovers,

She must have moist ointments ready

In her room, as necessary,

So she may hide and thus repair

Her face; but let no guest be there

As witness, or tis my belief

She might swiftly come to grief.

If she’s a fine neck, a white throat,

Then let her dressmaker take note,

She must wear dresses decollete,

And show her skin the whiter yet,

Six inches there, behind, before,

That she may but seduce the more.

And if her shoulders are too fat

To please, if dancing she is at,

Then let her wear a silken shawl,

To seems less ugly at the ball.

And if her hand’s not fair and white,

Due to some wart or insect-bite,

She should not neglect the skin,

But scrape the surface with a pin,

Or wear a pair of long gloves so

The warts and pimples will not show.

And if her breasts seem too heavy,

She should have a towel ready

To press them flat to her chest,

And round her sides secure the rest,

Stitched or knotted, whichever way,

So she can go abroad, and play.

And like a good child all complete,

She’ll keep Venus’ chamber neat,

If she’s well brought up, I’d say,

All the cobwebs she’ll sweep away,

Scour and trim, and smooth and gloss,

So that naught can gather moss.

With ugly feet she should choose

Always to cover them with shoes;

Thin stockings for fat legs too;

In short, hide all not worth the view.

And if her breath is not so sweet,

She should spare no effort to eat

Not fast, and for goodness sake

Speak not if she doth not partake,

And to keep her mouth well away

From others’ noses, and not stray.

If she gives way to laughter, she,

Should seek to do so discreetly,

With charm, and let the dimples show

At the corners of her lips also,

And never grimace, and never fail

To keep from puffing like a gale;

But smile and keep the lips closed,

The teeth covered, and in repose.

A woman should smile with her mouth,

For tis not pretty, north or south,

To widen the mouth at each side

Until an army could step inside.

And if her teeth are not quite even,

Worse ugly, crooked and uneven,

If she opens her mouth to laugh,

For a pretty woman tis a gaffe.

There is a proper way to cry,

But then every woman, say I,

Knows how to weep on occasion.

For whate’er may be the reason,

Even if not grief, hurt, or shame,

They’re always ready for that same.

They weep and are used to weeping

In whate’er guise they are keeping.

Yet no man should feel disturbed

If he sees tears, or be perturbed,

Though they flow as fast as rain,

For all those tears are not of pain,

Those sorrows and lamentations,

For they’re mere manifestations;

A woman’s tears are but a ruse,

For any pretext she may use,

Yet must take care not to reveal

By word or deed, what she doth feel.

Next, she must also take her place

At table with appropriate grace;

Before she even sits down, there

She should trip about everywhere,

Let all know, at least the hostess,

She knows all about the business;

Go up and down, and to and fro,

And be the last to be seated, so;

And look about a moment too

Before she settles herself anew.

And once she’s seated at the table

She should serve, if she is able,

She should carve before them all,

And pass the bread to one and all.

And then she must, to win his grace,

Before her close companion place,

A share indeed of every dish,

A thigh, a wing, a piece of fish,

Or carve the beef or pork or hare,

According to what meat is there.

Nor should she prove niggardly

In dealing out whate’er there be,

While one as yet’s unsatisfied;

But let her guard against the fried,

The wet and greasy; let her fingers

Keep far from the sauce that lingers,

Her lips far from the garlic, fat or

Soup, nor must she pile her platter

With far more food than she can eat.

Let but her fingertips touch the meat

That she would dip now in the sauce,

Whether for bland or spicy course,

And bring it carefully to her lips,

So that no drop or morsel slips

Down her chin onto her breast.

And if she drinks, neatly is best,

So naught is spilt down her front,

For one who did the sight confront

Might consider she was greedy,

Or at best that she was clumsy.

And she must not to be touching

Her drinking glass while she is eating

And she must wipe her mouth so clean

That on her glass no grease is seen,

Nor dwells there on her upper lip,

For when a smear, if she doth sip,

Remains, then drops fall in the wine,

Which is not pretty or refined.

And she must drink as a bird might

However great her appetite,

And never should drain a full glass,

Or goblet, in a single pass;

Little and often she should drink,

So that others there do not think,

Or say, that she doth drink too much,

Or while she eats, the wine doth touch,

But rather sips delicately.

Nor swallow the cup’s rim, should she,

Like many a nurse, as we see,

Who is both foolish and greedy.

They pour the wine down hollow throats

As into casks, or castle moats,

With great gulps that make one amazed,

Then they become fuddled and dazed.

She must ne’er in drink so indulge.

Every secret they’ll soon divulge

The tipsy man or woman, straight;

For when a woman’s in that state,

She has no defence, from drink,

But blurts out all that she doth think,

And abandons herself to all,

When into liquor she doth fall.

She must not fall asleep at table,

She’ll appear far less agreeable;

Many an ugly thing can occur

To those who sleep and do not stir.

It is not sensible to sleep

In those places where one should keep

Awake, many have been deceived

And then a nasty fall received,

Forward, backward or to the side,

And broken an arm, or leg, or died.

Beware lest sleep overtakes her,

Palinurus let her remember,

Helmsman of Aeneas’ vessel,

Who while awake steered her right well,

And yet when sleep overtook him

Fell from the rudder into the swim,

And drowned in sight of the company,

Who afterwards mourned him deeply.

Next, a lady must not delay

Too long ere she choose to play,

For so long there she might stand

That none offer to take her hand.

She should seek the delights of love,

While youth dictates her every move,

For when old age assails her, then

She’ll lose the attentions of men.

The fruit of love, the wise, in truth,

Will gather in the flower of youth;

For they do lose their time, alas,

If lacking love’s joys it doth pass!

If my counsel she doth not credit,

That I share with all, to their profit,

Know, she’ll be sorry hereafter,

When old age her flesh doth wither.

But I know that women will believe

At least those who wisdom receive,

And adhere to my rules, or may,

And many a paternoster will say

For my poor soul when I am dead,

Who comfort them, for twill be read

This lesson I preach, rule by rule,

And taught then in many a school.’

Chapter LXXIII: The Crone’s advice to girls on the make

‘MY fair, sweet boy, if you should live,

(For I see that these words I give,

All my teaching, you set apart

Gladly in the book of your heart,

And when you depart from me,

You shall be a teacher like me,

If it please God, for you will preach)

Then I’ll grant you licence to teach

Despite rules set by chancellors,

In all the chambers and cellars,

Meadows, groves and gardens,

Behind tapestries, in pavilions,

And thereby inform the students,

And in lodgings, in tenements,

In attic, wardrobe, kitchen, stable,

If you’ve nowhere more suitable.

But yet my lessons only tell,

To them when you have learned them well.

Now, a woman should take good care

Not to be shut indoors, for there

She is less seen by one and all,

And her beauty is not known at all,

Less desired and less in demand.

She should go to church, and stand

There to be seen, and go on visits,

To weddings, and to view exhibits,

To games, and to feasts, and dances;

For there the God of Love prances,

He and the Goddess school do keep,

And chant the mass to all their sheep.

Now if she would be well-admired

Of course she must be well-attired,

And when she wears the latest dress,

And through the streets she doth progress,

Let her bear herself alluringly,

Neither too stiffly nor too loosely,

Not too upright, nor too bowed,

But graciously, among the crowd.

Let her move her shoulders, her flanks,

So gracefully, that in the ranks

Of women none seems as lovely;

And she should walk most daintily,

In pretty little shoes, so sweet,

That well-made, trim, perfectly neat,

Fitting so tightly to her feet,

Show not a wrinkle or a pleat.

And if her dress should trail along,

Too near the pavement, and all wrong,

She should raise the front or side,

As it to sweep the breeze aside,

Or as if it were her habit

To raise her gown a little bit,

So she might walk more freely;

And take care to reveal briefly

The shape of her foot to the eye,

Of everyone who passes by.

If she wears a mantle, by the way,

She should wear it in such a way

As to make sure it part reveals

The lovely body it conceals.

For she will wish to display all

Her form, and the material,

Neither too heavy nor too light,

With silver thread and small pearls bright,

And her purse, prominently, too

For everyone she meets to view;

Open her mantle, show her charms,

And widen and extend her arms,

Whether the street is clean or muddy,

And remembering that fan, that he

The peacock offers with his tail,

She should her mantle like a sail

Extend so as to show the lining,

Grey, or vair, or whatever, shining,

And flaunt her body on the street,

For any onlooker she may meet.

And if her face is not so lovely,

She must be clever, let them see,

Her blonde tresses, rich and fair,

Her head behind coifed with care,

With never a loose tress in sight.

A fine head of hair, fair and bright,

Is truly a most pleasant thing.

Now, a woman must seek to bring

Ever a she-wolf’s powers to bear

As when that creature’s sole affair

Is stealing ewes, when she must run

At a thousand sheep to capture one,

Not knowing till she sees it bleed,

With which of them she will succeed.

So a woman must spread her net

Among all men, uncertain as yet

Which of them she may have the grace

To capture, till she sees his face,

And attach herself to them all,

To guarantee that one will fall.

Thus she’ll not have to wait too long

To find one fool that crowd among,

Of thousands that brush against her,

To recruit as her defender,

Or more than one, peradventure,

Since art doth greatly aid nature.

And if she doth hook a number

Of those who would kiss her finger,

Let her take care, for tis her power,

To grant no two the self-same hour,

For they would think themselves deceived

If two together she received;

And then they might even quit her,

On account of feeling bitter,

And she’ll lose, at the very least,

What each of them brings to the feast.

No, she should leave them naught at all,

On which to fatten, but see them fall

Into such depths of poverty

They must end in misery,

And debt, while she grows wealthier,

For what they keep tis lost to her.

She must not fall for one who’s poor,

For no man that’s poor is worth more

Than a glance, though he be Homer

Or Ovid; nor for some traveller,

Who as he lodges in many places

Amongst many bodies and faces,

So he has a heart that’s flighty.

No, let her pray to the Almighty,

Not to fall for a travelling man,

But she should gather what she can

If he offers her cash or jewellery,

And hide it in her treasury;

Then let him take his pleasure,

Whether in haste, or at leisure.

She should be careful not to pant

After one who’s too elegant,

Or who likes to vaunt his beauty,

For pride tempts him; so Ptolemy,

Who says that the man who pleases

Himself, e’er his God displeases,

(And Ptolemy was a great lover

Of knowledge, and truth moreover.)

Such a man can ne’er love well,

His heart is under an evil spell,

And bitter, and then such a man

Says to all what he says to one,

Deceives many women indeed,

But to despoil them, in his greed;

Many a complaint I’ve received

From many a girl so deceived.

And if any man makes promises

Whether he’s honest, or wishes

To swindle her, hoping for her

Love, or with pledges to bind her,

She may promise him in return,

But must be careful, in her turn,

Never to give herself away,

Unless some money comes her way.

In aught that he puts in writing,

She for deceit should be looking

To find if it shows good intention,

A true heart without deception.

Soon she may write him her reply,

Yet delay a little longer, say I,

For delay excites many a lover,

As long as tis not forever.

When she hears a lover’s request

She should take care, for it is best,

Not to grant all that he desires,

Nor ban all to which he aspires.

Rather keep him in the balance,

Twixt hope and fear so let him dance.

And then when he asks more of her,

And she aims not to surrender

Her love to him, but bind him tight,

With cunning and with all her might,

Let her ensure that hope shall grow

Little by little, but passing slow,

While fear diminishes all the while,

Till peace doth them both reconcile.

She who does so, with all her feints,

Should swear by God and the saints,

That she had ne’er wished to give

Herself to any, as long as she live,

And say: “Fair sir, here is my all,

By Saint Peter on whom I call,

I give myself to you from love,

Not for presents; heavens above,

The man’s not born for whom I would

Give myself for such gifts, nor could.

Many a fair man I’ve refused,

Though many have o’er me enthused,

I think o’er me you’ve cast a spell,

An evil charm chanted as well.”

Then she must embrace him straight

And kiss him hard, to seal his fate,

Yet, if she’ll listen to my advice,

Think of gain ere she does so twice.

She’s a fool who plucks not a lover

Down to the very last feather;

For the better that she can pluck,

Then the better will prove her luck,

For she’s held the dearer, clearly,

Who doth sell herself more dearly.

And men who get all for nothing,

They think it not worth anything,

No not a single husk of wheat,

And thus think naught of losing it,

At least not as much as will he

Who has bought the thing dearly.’

Chapter LXXIII: The Crone’s advice on how to despoil a lover

‘HERE is the way to pluck a man:

Get all your servants, tis my plan,

Your chambermaid, your nurse, your sister,

Even, if she will, your mother,

To help you in the given task,

And so take every chance to ask,

For coat and mantle, glove and mitten,

As by wolves let him be bitten,

That will seize on all they can,

So that the unfortunate man,

No means of flight can hit upon,

Till his very last sou is gone.

As though twere with buttons he played,

Let all his gold coins be displayed;

The prey is ever captured apace

When many hunters join the chase.

On occasion let them say: “Sire,

See you not my lady’s desire,

For a new dress; though we say so,

How can you let her go forth so!

If, by Saint Giles, she wished to be,

With a certain person in this city,

Why, she’d be dressed like a queen,

And in a coach and four be seen!

And you, lady, why wait so long

To ask for that for which you long?

You are too shy in your pursuit

Of one who leaves you destitute.”

Howe’er it pleases that they try it,

She must order them to be quiet,

She who has perchance relieved

Him of such as leaves him grieved.

And if she thinks he doth recognise

That he’s given more than is wise,

And may be harmed grievously

By all he gives so generously,

And does not feel that she dare

Urge him to strip the cupboard bare,

Then she should ask him for a loan,

Swearing she’s ready, she doth own,

At any time, that sum to repay,

If he will merely name the day;

But let her be torn limb from limb

If aught she e’er returns to him.

If some past lover appears, the while,

Of whom, God willing, there’s a pile,

On none of whom she’s set her heart,

Though she calls them all “sweetheart”,

She should complain, if she is wise,

That she’s in debt up to her eyes,

Her best dress pawned, tis usury

That means she’s in such misery

And so uneasy is her heart

She can do naught, on her part,

To please, till he redeems her debt.

And if he’s not wise to her yet,

And happens to have cash to hand,

Into his purse he’ll put his hand,

Or bring about some contrivance

By which she wins deliverance,

From debts that need not be paid,

For in some coffer she has laid,

The better that he might believe,

Those items he must not perceive

In her wardrobe, you understand,

Till she’s the money in her hand.

Of a third friend she should request,

Perchance, a silver belt, a dress,

Or a scarf, or since he’s a friend,

Some cash in hand that she can spend.

But then if he’s naught to give her,

Yet swears to her, to comfort her,

While promising, at her command,

Tomorrow it will come to hand,

Then she should turn a deaf ear.

Trust not a thing, tis lies I fear,

All men indeed are expert liars;

More lies I’ve had from those sires,

More oaths and vows, to be precise,

Than there are saints in paradise.

If he has naught, let him at least

Pledge his word for wine, the beast,

Two sous worth, or three, or four,

Or go knock on another’s door.

A woman who’s no simpleton

Must feign to be a coward, one

Who trembles much and doth appear

Anxious, distraught, and full of fear,

Whenever she receives her lover.

She should have him know, moreover,

Tis perilous to receive him,

Since her spouse, well, she deceives him,

(Or her parents, or her guardian)

And that she’d be dead for certain

If what she would do covertly

Were there for everyone to see.

She should swear he cannot stay

If it brings ill in any way,

And then, when she has enchanted,

He’ll remain just as she wanted.

Then she should always be sure

Whene’er her lover’s at the door,

To guarantee he’s not perceived,

That through the window he’s received,

Even if twere fine through the door,

And swear she’d be ruined evermore,

Or dead, and he’d be dead as well,

If aught were known of what befell;

No sharp weapon could defend him,

Nor helm or hauberk would protect him

Nor would the wardrobe in her chamber,

He’d be shorn of every member.

Next, she must be ready to sigh,

Wipe an angry tear from her eye,

Attack him forcefully, and say

He must have a reason for delay,

That he comes so late, it must be

That elsewhere he keeps company

With some other girl, whoever,

Whose charms yield him greater pleasure,

And that she’s indeed betrayed,

Now his hatred for her’s displayed,

And she a wretched fool is proved

For loving where she is unloved.

Then, once her anger he has bought,

Once occupied with foolish thought,

He’ll believe, quite incorrectly,

That this girl loves him loyally,

And indeed that she’s more jealous

Than Vulcan e’er was o’er Venus,

His wife, he caught there in the act;

With the god Mars she lay, in fact.

For he had forged a net of steel,

To hold them; naught could they conceal

When they were coupled in their play;

The fool had spied on them that day.’

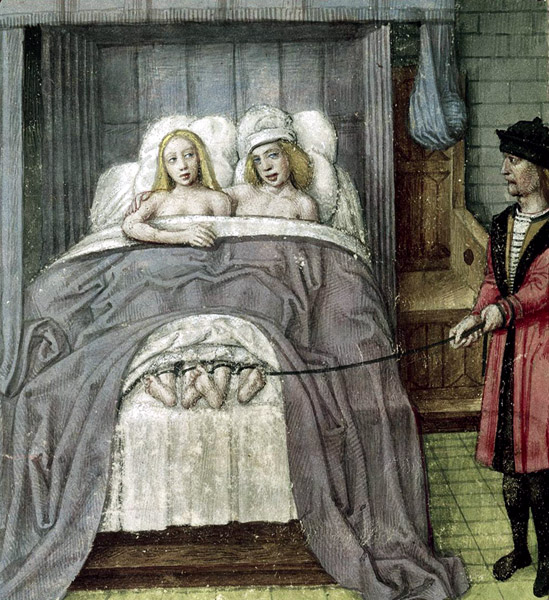

Chapter LXXIV: The tale of Venus, Mars and Vulcan

(Lines 14445-14542)

How Vulcan spied upon his wife,

Venus; and caught her, by my life,

In a net with Mars her lover,

When he found the two together.

‘The tale of Venus, Mars and Vulcan’

‘NOW, the moment Vulcan knew

That he indeed had caught the two,

In that net of steel he’d prepared,

(Only a fool would thus have dared,

And little he knows, he who’s said,

That he alone his wife will bed)

He summoned up the gods swiftly,

Who all laughed long and loudly,

On seeing them in such a plight,

Amazed at Venus’ beauty bright;

It delighted the majority,

While she was ashamed and angry

At having been caught and netted so;

Much she complained in her woe,

Great her shame and without equal,

Yet twas not very wonderful

If Venus gave herself to Mars,

For Vulcan, all replete with scars

And soot from his forge, was ugly,

Black his hands, and face, and body,

Such that Venus she loved him not,

Nor could, marriage being their lot,

Not though an Absalom was there,

As spouse, he of the long blonde hair,

Or Paris, son of the King of Troy,

Even then she’d have felt no joy.

For she knew, lovely and debonair,

What all women know of that affair.’

Chapter LXXIV: Woman’s natural freedom

‘BESIDES, all women are born free,

Tis the law acts conditionally,

Taking away the freedom Nature

Gave to them in equal measure.

Nature is not so foolish she

Gives birth to some girl, Marie,

Solely to mate with Robichon,

If wisdom’s cap we now don,

Nor Robichon with Mariette,

Or Agnes or, perchance, Perette.

She made all women, forever,

For all men, and vice versa,

Each man is for every woman,

And each woman for every man.

So when a woman’s engaged, you see,

Then taken in marriage lawfully,

To avoid quarrels and contentions,

And even murderous intentions,

And to aid the children’s nurture,

Whom parents care for together,

She’ll still struggle in every way

To regain her freedom each day,

This demoiselle, or this lady,

Whether she is gross, or lovely.

They’ll act freely, if they can do so,

From which many an ill must flow,

And does flow, and has flowed before.

A hundred names I’d name, or more

If I were not forced to move on,

For I’d be tired when I was done,

And you tired of hearing them all,

Ere I’d listed those that I recall.

In times past when a man guessed

That some woman would suit him best,

He’d seek to ravish her, there and then,

If she was not claimed by other men,

And then he’d quit her if he wished,

Once he’d added her to his list.

Men and women killed each other,

Blind to their offspring’s nurture.

This was ere marriage was contrived,

By wise counsel; then they survived.

And, if Horace you’ll dare believe,

Good and true words you’ll receive,

For he knew how to think and teach;

I’d like women to hear him preach,

For a wise woman feels no shame

When such authority she doth name,

Thus: long ago, in Helen’s day,

There were wars over women, pray,

In which many fought and died,

With great suffering on each side;

Many the dead who are unknown

For Homer sang of Troy alone.

And those men were not the first,

Nor shall be the last to be cursed

By wars that have and will be waged

By those whose hearts are engaged

By one woman alone, and thus

Both body and soul are lost to us.

And shall be lost if the world endure;

But attend to Nature once more,

And that I may more clearly address

What wondrous power she doth possess,

Many examples I’ll advance you,

Which in detail may convince you.’

The End of Part VII of the Romance of the Rose Continuation