Guillaume de Machaut

The Book of the True Poem (Le Livre dou Voir Dit)

Part IV

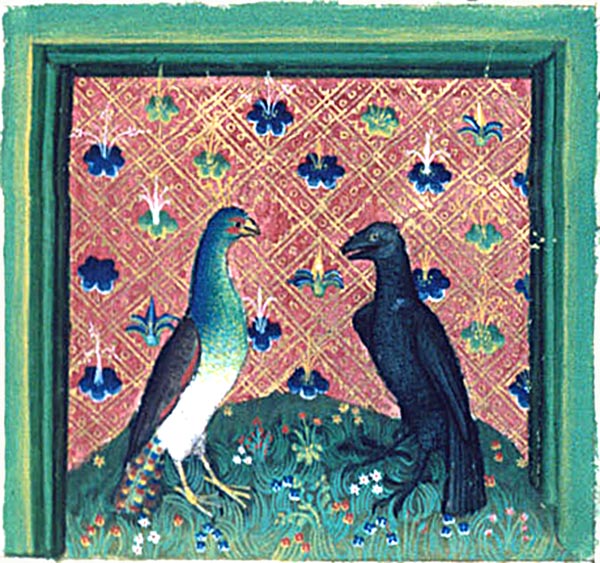

A peacock being mocked by a raven, Austria, W. (Salzburg); c. 1430- British Library

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 6963-6990: Of Polyphemus’ love for Galatea.

- Lines 6991-7222: Polyphemus’ song addressed to her (cf. Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ Book XIII).

- Lines 7223-7260: The Secretary completes his advice.

- Lines 7261-7304: The lover’s friend enters and gives his counsel.

- Lines 7305-7341: The image of Friendship.

- Lines 7342-7414: The meaning of the image’s attributes.

- Lines 7415-7474: The friend advises the lover to desist from his affair.

- Lines 7475-7514: The lover grows despondent.

- Lines 7515-7568: He responds to his friend’s advice.

- Lines 7569-7632: The lover meets the same counsel on every side.

- Lines 7633-7662: He hides her portrait and writes his seventeenth ballad.

- Lines 7663-7683: His ballad ‘Se pour ce muir qu’Amours ay bien servi’ (Ballad XLII).

- Lines 7684-7693: He receives her twentieth letter.

- Lines 7694-7715: He replies with his twenty-first letter.

- Lines 7716-7737: The lover sleeps and dreams again.

- Lines 7738-7791: His dream of the portrait.

- Lines 7792-7845: The tale of how the crow’s feathers became black.

- Lines 7846-7881: The raven reproaches and corrects the crow.

- Lines 7882-7987: The raven’s story (cf. Ovid’s Metamorphoses Book II).

- Lines 7988-8039: The crow reports the affair to Phoebus.

- Lines 8040-8105: Coronis is punished by Phoebus.

- Lines 8106-8131: The crow receives his ill reward.

- Lines 8132-8179: The portrait image continues to admonish the lover.

- Lines 8180-8201: The dreamer wakes.

- Lines 8202-8261: He reinstates his lady’s portrait.

- Lines 8262-8311: Livy’s description of Fortune according to Fulgentius.

- Lines 8312-8327: The lover considers the image of Fortune.

- Lines 8328-8343: His response to the first emblem.

- Lines 8344-8359: His response to the second emblem.

- Lines 8360-8375: His response to the third emblem.

- Lines 8376-8391: His response to the fourth emblem.

- Lines 8392-8409: His response to the fifth emblem.

- Lines 8410-8423: He concludes his comparison of his lady to Fortune.

- Lines 8424-8473: The treatment of the falcon that strays.

- Lines 8474-8493: His attitude to his lady’s fickleness.

- Lines 8494-8509: He sends his lady his twenty-second letter.

- Lines 8510-8525: His lady is distressed at his letter and composes a ballad.

- Lines 8526-8572: Her tenth ballad, a virelay ‘Cent mille fois esbahie’.

- Lines 8573-8578: She sends the virelay with her twenty-first letter.

- Lines 8579-8652: She writes again, sending her twenty-second letter.

- Lines 8653-8690: The messenger reproaches him.

- Lines 8691-8726: The ancients’ description of Fortune.

- Lines 8727-8774: The Fountain and its five states.

- Lines 8775-8812: The messenger compares the lover to Fortune.

- Lines 8813-8862: The messenger’s interpretation of the five states of the fountain.

- Lines 8863-8890: He ends his comparison.

- Lines 8891-8936: The lover is persuaded and writes a twenty-third letter.

- Lines 8937-9016: He asks the messenger to commend him to his lady.

- Lines 9017-9042: His lady responds with a twenty-third letter.

- Lines 9043-9050: The lady’s sixteenth rondel yielding Guillaume’s name.

- Lines 9051-9070: The lover expresses their new-found concord.

- Lines 9071-9088: Their names encoded in the verse.

- Lines 9089-9095: His coda.

Lines 6963-6990: Of Polyphemus’ love for Galatea

GALATEA, whom the monster

Greatly loved, claimed, however,

That Love scared him; for it appeared,

That where he loved he also feared.

See what this shows: that there is naught

A woman cannot gain, unsought;

If Amor but gives his consent,

Women can do much, sans intent;

Yet what can Love seek I wonder

Setting himself amidst such ordure?

Blame and reproach I afford him,

Whoe’er may their praise accord him.

Now, when Polyphemus was denied

His sole eye, he yet blindly sighed,

And oftentimes he sat alone

High on a massive seat of stone,

And there, when his pleasure he sought,

He played his flute, such her report,

All its hundred pipes together,

And made the whole landscape shudder.

So, it seemed to those who heard him,

And midst the thunder, they feared him.

And thus, the monster played, to suit

Himself, who knows what on his flute.

And yet one song he did compose,

So she tells, of his love and woes;

I find it here, but cannot say

If it’s a song, or yet a lay.’

Lines 6991-7222: Polyphemus’ song addressed to her (cf. Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ Book XIII)

‘“GALATEA’S body’s whiter

Than the flowering meadow, nobler,

Fairer, sweeter, and yet more true

Than is the very straightest yew,

Brighter than the water shining,

Prettier, and yet more pleasing

Than little tender goats to me,

Soft as the shellfish from the sea,

Her flesh; fair one, more lovable

Are you and more agreeable

Than the sunlight is in winter,

Or the cool shade in the summer.

O lady of great worth, say I,

There you stand beneath the sky,

Taller, more graceful than the palm,

In all your noble perfumed charm;

Rosier, of brighter colour

Than the apple of sweet flavour;

Lady your brightness doth surpass

The brightness of shining glass,

Worthy lady, riper in shape

Than the sweetest ripened grape.

Lady, courteous, friendly ever,

Whiter than the white swan’s feather,

Or the young quail’s, or the gull,

More pleasant and more beautiful

Than a garden, moist and fertile,

Full of sweet fruits that lips beguile,

Come to your lover, who doth call

To you, hide not from him at all,

He who desires and loves you so,

Grant my wish, my pleasure also.

For should you deny me further

None indeed could e’er be crueller.

Should you do not do as I would wish,

Ne’er was bull crueller than this,

Undaunted in its arrogant pride.

Tougher were you than oak beside

Should you not prove amenable,

And vainer and more changeable

Than a running stream, more pliable

Than a willow branch, more flexible

Than a vine where white grapes grow,

Less merciful, I’d have you know,

Less moved by pity, or by kindness

Than the briar, that wounds us less;

More harmful than the ocean wide,

With all its depths, more full of pride

Than a peacock, praised fulsomely,

Spreading its tail, vaingloriously;

More hateful and more annoying,

More painful yet than fire burning

Dead brushwood, lard, or dry sedge;

Sharper than e’er is thorny hedge,

More savage than a bear in heat,

False as the Hydra in defeat,

And darker than the troubled water,

If you disdain to love me ever.

More fearful than the frightened doe

Or stag that runs before the bow,

And not like to the stag merely,

But more wont to flee me, truly,

Than is the wind; yet, if I could,

I’d cure your fickleness for good.

For if you knew my true intent,

I do believe you would repent

Of fleeing so readily from me,

Then you would rather stay with me

And you would take more pains than this

To accomplish my every wish.

For you would enter my domain,

The cave I dwell in, and remain,

Where the cliff arches high above.

Neath the mount that cannot move.

So strong and rock-bound is the place

No sunlight there shall mar your face,

However lengthy proves the summer,

Nor shall you feel the chill of winter.

In my garden are apple trees,

And they bear ample fruit to please,

Almost more than they can hold,

And, if you deign such to behold,

I’ve rich grapes on my vines growing,

That I’ll keep against your coming,

Purple and white, and you shall eat

Of those that please you or, replete,

Partake of strawberries, if you wish,

You may gather there, and relish,

That grow in the woods; their treasure

You may heap there at your leisure;

And then sorb-apples too, and sloes,

Bud and blossom, whate’er there grows,

And ripe plums, both red and green,

You may gather, the leaves between.

Deign to take me for your spouse,

And you’ll have chestnuts in your house,

And all the fruits of bush and tree,

In great plenty; rich shall you be,

If you agree that you’ll be mine.

As my wife you shall never pine

For lack of aught. And better still

Are all my herds, of vale and hill,

About us here, below the mount,

And in the woods in vast amount,

And in my cave there, penned within.

And if you seek their count to win,

I’ve creatures there beyond number,

Such that I cannot tell their number,

For he’s a poor man who can come

To a total, and his riches sum.

If you think it cannot be true,

All I have said, why then, come view

All that lies in my possession,

And you will know, without question,

If tis a lie. My cattle you’ll see,

With udders so full they scarcely

Can contain the milk they hold,

And then the lambs not one year old

And the kids, and in the cavern

I drink milk whate’er the season,

And with it I have soup to please

And from it too I oft make cheese.

You may surely take your pleasure

Of what I have, in full measure,

All I have told you of and more,

For there are other gifts in store.

I’ll give you roe and fallow deer,

Rabbits and hares too breed here,

All to please you, such is my care.

Of turtledoves I possess a pair

Had from the nest the other day,

With these you can gently play.

Two fledglings I have, of an age,

Of the same size and plumage,

That I found about the mountain,

And I declare, till a certain

Lady comes they shall be guarded

As a gift for her, ne’er discarded,

Fair one, refuse not then my offer,

Nor the lovely gifts I’d proffer,

Instead come turn your head away

From the sea, since I am, I say,

Worthy of love, and this I know,

For in the still pool, here below,

I have seen both my form and face

Reflected in that watery place,

And I am handsome and well-made,

Pleased to see myself so displayed,

The greatness of this form of mine,

How tall a youth I am and full fine.

I know not what god in heaven,

As you folk say, is as handsome,

As noble, or as huge, I say.

I have great locks of hair that stray

Down to my shoulders, o’er my brow,

That suit me well, for you’ll allow

A horse without a mane is ugly,

And birds and their young should be

All clothed in feathers, without fail,

Or they’re like fish without a scale;

As wool is fitting for the ewe,

So every man needs a beard too,

Or he’s ugly, and unseemly;

The body-hair I have suits mine,

Long and thick, and like the swine

It bristles just as their hide does;

Such is the covering I’d choose.

I have but one eye neath my brow

But this becomes me, I’ll avow,

Since it’s vast, both wide and round,

As many a shield may be found;

There’s but one sun, up in the sky,

And, likewise, I have but one eye,

While the world is a single sphere,

So though my hair bristles, tis clear

You should not for that despise me,

There’s little value in the tree

That’s barren of foliage, and so

Do not be proud towards me, no,

Sweet sister, take me as your spouse,

For I am come of a noble house,

Such that you ought to desire me,

As son to the god of the sea.

A great lord is he, my father,

You indeed could find none greater;

No more is required my lady

Than that you do, willingly,

All that I ask, respectfully,

Of you; for of yourself only

Am I the subject, and would be.

I hold Jove, or any other

Gods, their lightning and their power,

And all their virtues, as of naught;

Not worth a fig are they, in short.

On you alone I call, and more,

Alone do honour, fear, adore.

I dread not the lighting, ever,

As much as I do dread your anger.

And if you loved me well, why then,

Since you’d refuse all other men,

Just as you would refuse me now,

I would be more content, I vow,

And I’d endure it, patiently.

But I am wounded, grievously,

For you disdain the giant in me,

To love some wretched nobody,

Actis, in whom you seek solace,

One whom you kiss and embrace,

While my embrace you yet disdain;

No pleasure, comfort I obtain.

As much as he may please you, I,

If I can find where he does lie,

Will display all my great might,

I’ll rob him of his heart, outright,

No matter whom it displeases

And tear him into little pieces,

And strew them all about the ways,

And o’er the fields, so you, always,

May see the one that you love so.

I’ll spread him o’er the sea below,

So that you may be together,

Thus, I’d wish you joined forever.

Jealous am I, and thus accursed,

A scorching flame have I or worse,

That roasts, and burns, and doth grieve me

Like the fires of hell, believe me;

I languish for your friendship, yet

With no mercy from you am met.”

Such is the outcry, the complaint

That ever is the monster’s plaint,

Hold it not as some mere fable,

For tis the singing of the devil.’

Lines 7223-7260: The Secretary completes his advice

‘NOW you have heard all that singing

From its very first beginning

Through to its finish, start to end,

Telling how the giant did extend

His heart’s love to fair Galatea,

And his mad deed concerning her,

His treason and his cruelty

And his immense disloyalty,

And of the sad end men did meet,

Whom that mighty grip did greet;

And yet I promise, faithfully,

He would not treat you so harshly

If into his hands you should fall,

As those thieves that, you recall,

And enemies, and there are many,

With which the devil plagues this country;

Who could not thus afflict folk more

Except by slaying them, tis sure.

And ever the cold winds do blow

That destroy more than we know,

And overthrow the stoutest tree,

And sink brave vessels in the sea.

You would soon be dead I fear,

So, my advice is: rest you here;

And here indeed you should stay,

Yet twere best that, straight away,

You should write your love a letter

And within it you should tell her

The reasons why you’ll not set out,

For she is such, without a doubt,

Who would never seek to blame

Or love you the less for that same.

And I’ll write to your lady too,

And say the very same as you,

And tell her why you yet remain.

Now, let us write to her amain;

And let your heart be full of joy,

Such is your very best employ.’

Lines 7261-7304: The lover’s friend enters and gives his counsel

WHEN his speech had reached its finish,

A speech which I thought most foolish,

I said: ‘My friend, by Saint Simon,

You’ve preached me a lengthy sermon

As to why I should ne’er see her,

Yet prove but a vain counsellor,

For you are no true advocate,

If the only counsel you can state

Is counsel that does me no good,

For you know well I ever should

Obey the sweet commandment she

Ordains, whom I love faithfully.’

In this way, we sat debating,

With each his own viewpoint stating

In support of his contention,

Yet it reached no firm conclusion,

For a nobleman made entry

To my chamber, treading softly,

And ending thus our conversation

Brought about its termination,

Crying: God save this company,

From anger and from villainy,

Grant them peace, honour and joy

Such as I’d wish Love to employ.’

Straightway, we leapt to our feet

And humbly then the man did greet,

Doing him reverence, as we should,

All from the heart, as best we could.

By the right hand, as we did meet

He took me, and to a window-seat,

He led me, sat upon on a cushion,

And told me how, in what fashion,

He had just heard, from start to end,

All the argument, as my friend,

Twixt me and my secretary there,

And understood the whole affair,

The whole debate and argument,

Likewise, the fable, and its intent,

The urge and the desire in me,

To be with my lovely lady;

And from this he’d defend me,

If I would but listen closely,

And show him love, respectfully;

Which I did, most diligently.

Lines 7305-7341: The image of Friendship

FOR now he said: ‘Friend, if I knew

Your greatest virtue I’d help you

To enhance it, raise your esteem,

Lessening what doth harmful seem.

For truly you have here, in me,

A friend of utmost loyalty,

And, for that reason, I’ll relate,

Solely to aid your inner state,

How the ancients did once portray

Friendship’s image, in their day.

The form of a youth they’d paint

Or carve, one lacking mar or taint,

As handsome in body and face

As a subtle hand could, with grace,

Achieve; bare of head, save, I mean,

For a fair garland, all in green,

Which was most noble; moreover,

Painted letters, in gold and silver,

Adorned its brow, saying, ever,

‘Whether tis winter or summer.’

His chest lay open; by true art

One might readily view the heart,

And he had naught, as I have said,

To claim his rank, upon his head.

And, with a finger, he pointed to

His chest where there was writing too,

And there it said: ‘Or far or near,’

I swear that it did so appear.

This figure, in a coat of green

Greener than any leaf is seen,

Seemed as though it drew breath,

And in pure gold ‘In life and death,’

Was written at the hem; all bare

The feet, no boot or shoe was there.

Now I’ll tell you, without delay,

If you will list to what I say,

What the image doth signify.’

Lines 7342-7414: The meaning of the image’s attributes

‘THE garland, pleasing to the eye,

Means that one should e’er defend,

From all his enemies, one’s friend,

And that in all that’s to be done

The two should ever act as one,

Since one adorns oneself e’en so,

For a garland doth beauty show;

Naught is more lovely, equally,

Than is, in truth, great loyalty;

While the garland, through its art,

Shows joy, a treasure in the heart.

That the head’s uncovered there

Shows how, in mishap and despair,

In ill times and adversity

No less than in prosperity,

A friend will never help deny,

But rather will, with head held high,

Proceed without pride, lovingly,

To aid a friend, howe’er they be.

True friends provide assistance so,

For they are neither dull nor slow

To fight their fight, and advocate

Their cause, in friendship, soon and late.

The writing there, upon the brow,

Teaches, and thus makes clear, how

Perfect friendship, faithful ever,

Knows not cold, heat, winter, summer,

But ever the same point doth mark,

Nor doth to alteration hark,

Just, and firm, and loyal wholly;

Who loves well, forgets tardily.

Now, since you’re listening closely,

That the heart one can clearly see,

Since the chest lies open, doth show

That by the heart a friend we know,

And that to naught they will aspire

Unless love proves firm and entire.

And shows, by its very manner,

That Friendship doth bear a banner

Meaning that true love, if complete,

Bears nor concealment nor deceit.

The coat of green, it wears likewise,

Shows that Friendship never dies,

Or withers, but is ever new

And like the lentil fresh in hue,

That hides its verdure in winter,

Yet reveals it come the summer;

Thus, true love though hid, indeed,

Is yet disclosed in time of need.

The lettering says that, sans regret,

In life and death there’s Friendship yet,

The finger pointed at the heart

Says he is ever true, and the art

Of the gold letters set close by

Says that or near or far, thereby,

Present or absent, he’s a friend

Who will love truly till the end.

Now tis my duty to explain

Why the feet are bare, again

Just as the head, and the face also,

Are uncovered, so all may know,

All folk, whether in their chamber

Or hall, or on the road, wherever,

That face and heart they should declare,

So the feet are portrayed as bare.

Nor should a true friend wait to don

Their boots or shoes ere they be gone

To aid their friend who is in need

Nor should they be afeared indeed

Of rock or stone, pebble or thorn.

Such love of true affection’s born,

Pure, not concealed nor hid away,

In town or field, or on the highway.’

Lines 7415-7474: The friend advises the lover to desist from his affair

‘NOW I’ve told you of the image

Of true Friendship, and how the sage

Men of ancient times portrayed it,

And the significance they gave it.

And such a friend am I to you,

For what I say, I swear, is true,

And my friend, if my good counsel

You would take, then I shall tell

You of the path that you should go;

You’re so mad for the lady, though,

So attached to her that, I fear,

By my soul, being held so dear

All my words will go for naught,

Yet no matter, for still I ought,

Whether it pleases you or not,

To speak out, for such is my lot,

And tis not right to rest silent;

Unvarnished truth is my intent.

Friend, by God, in this affair

There’s more than one ass at the fair,

For several suitors has your lady,

Young and handsome, brave and merry,

And they oft go and visit there,

And I pledge you that, everywhere,

To one and all, many a letter

Of yours she goes showing ever,

Which prove a source of mockery;

Many do laugh your words to see.

For she boasts of your love, I know,

And even the wind that doth blow

Is not so readily perceived

As is the fact that you’re deceived.

Think you that she doth love you true

Because ‘friend’ is what she calls you?

In just the same manner, I feel,

She’d name a stranger from Castile,

And her dear friend the man would be

While he was in her company,

For she’s open and courteous,

Knows what friendship’s worth to us,

And though I’ll not say she loves him,

Yet as her ‘friend’ she’d address him,

For many a lady will term as ‘friend’

One that she loves not in the end.

Upon your lady I cast no blame,

Virtuous, prudent, is that same,

Wise, honest, courteous and fair,

Nor is of a secretive air;

My counsel is for you, my friend,

For tis to her your heart doth tend,

With affection that ceases never,

Making of yourself a martyr,

For foolishly you spend your days

Caught fast, and yet deceived, always.

And, be sure, folk mock you too,

So, my friend I do advise you

To quit this amorous affair,

And end all your commitment there;

And trust, friend, in my counsel,

For, by my faith, I counsel well.’

Lines 7475-7514: The lover grows despondent

AFTER he’d spoken at leisure

And at length, to his good pleasure,

I was not swift in my reply,

For mind and sense were both, thereby,

Confused, more than one could conceive

And many a man might believe,

For all my limbs were set a-trembling,

My eyes with tears softly filling,

And so, I knew not what to say,

Such grief and anger came my way,

For one of my friends had written

Not long ago that I was smitten;

I’d sent him to her, he too had said

That I should seek her not, instead

I should leave her, reclaim my heart

Without delay, renounce my part.

I put these two things together,

Comparing one with the other,

And thought that both were likely true

If such was the counsel of these two,

The one the great lord present there,

Who was a friend beyond compare,

And the other whom I trusted, too,

To perform whate’er I sought to do,

As much as I myself, and sure

I think he loved me even more

Than the lord who now chastised me

Because my heart loved too deeply.

This was no trifle, no fancy,

No fable told to deceive me,

But must, of bare necessity,

Be most certain truth they told me,

Knowing that it was not all lies,

For they’d kept silent otherwise,

Not given indeed to play-acting,

As I well knew, nor gossiping.

So wounded was I in spirit,

My heart lost the joy within it;

I knew such melancholy then

I thought I’d never smile again.

Lines 7515-7568: He responds to his friend’s advice

I said: ‘My lord, of a certainty,

You have brought ill news to me,

News that finally makes plain

Such facts as but renew my pain.

This I shall suffer secretly,

Showing but little openly,

Until, indeed, I can learn more

Of what you say, and so am sure.

My lord, though I do believe you,

And am certain, were it not true,

You would ne’er have said a word

Of all this that but now I heard,

Yet it is right that I should do

As I intend, and privately too,

For ill haste will win no prize,

Or benefit, or honour, likewise.’

He said: ‘And you will do no more?’

And I replied: ‘I shall, be sure

To withdraw if I can so do,

Yet not suddenly, for my view

Is that sudden changes of plan

Prove harmful to many a man.

Her kindness, her generosity,

Have from death twice rescued me,

And base would be my attitude,

Betraying great ingratitude,

If I forgot all she’s done for me,

Many a time, of her courtesy.

And I have promised, moreover,

To be always her fond lover,

And never seek another love.

Rather, loveless I would prove,

And love none other, losing her,

And so, call myself thereafter,

The most miserable of men,

And ill-fortuned for, I maintain,

Never have I lacked Love before,

He ever dwelt with me, tis sure;

And all my art I’d then forsake,

Doubtless I would no longer make

Rondel, ballad, or virelay,

Poem, fair song, amorous lay,

For after such pleasant employ

My heart could ne’er know perfect joy,

Rather it would prove melancholy,

Sad and pensive, more than ready

For fell death, without remission.

Now have I spoken my intention.’

Having heard all I did utter,

He said: ‘I’ll not meddle further!’

Then drank a little, and departed,

Leaving me nigh broken-hearted.

Lines 7569-7632: The lover meets the same counsel on every side

MY secretary had heard his speech,

And asked me: ‘Sire, does he teach

Good counsel, as your guiding star?

By the faith you owe Saint Gringoire,

Tell me true.’ but I answered naught,

And he began to grumble somewhat,

Saying: ‘I had my doubts, although

I feared, my lord, to tell you so,

Much afraid I’d rouse your anger,

For such I thought was the danger,

And the agreement we two share,

Thus, be damaged beyond repair.

Tis why I ne’er do make a vow

To any woman to serve her, now;

Swift are they made, yet to our cost

Such vows are all too lightly lost.’

Upon hearing the sombre note

He sounded, my sad heart took note,

Such that, for many a long day,

I kept in mind all he did say.

Twas after forty days, or more,

I would say, though I am unsure,

A special friend of mine told me,

One e’er loyal and trustworthy,

‘Some advocate she has with her,

Arguing his own case better

Than you could ever do, truly;

It seems he does it so expertly,

Fair sweet friend, you will be set,

Among the sins she would forget.’

In another three weeks or so,

Over hills and dales, I did go,

To see a lord I knew, greater,

A thousand times, than the other.

He began to smile, on seeing me,

And then addressed me, laughingly:

‘About the bush you beat,’ his words,

‘From which other men take the birds.’

And this he pronounced openly,

To my face, and in company.

On finding myself greeted so,

I felt now so wretched and low,

So mute, rendered silent, was I,

I mustered not a word in reply.

Gathering myself, I wished him well,

And yet on having heard his counsel,

My heart within was quivering,

I knew not what I was saying,

God help me, for now everyone

Was telling me I was undone,

And all they said exhorted me

To forget my lady, wholly,

She whom I love, serve, praise and prize.

As I walked down the street, likewise,

Everyone hurled some jest at me,

All crying, by way of mockery:

‘There’s one owns to a fine lady!’

And they poked fun at me like this,

Because it was my lady’s wish

That our true love be noised about

The streets and, once the news was out,

Everyone then did know and see

The truth of my lady’s love for me;

So, common knowledge it was then

To one and all, women and men.

I’ll tell you what I did, therefore;

It profited me, I am sure.

Lines 7633-7662: He hides her portrait and writes his seventeenth ballad

TWAS in the month of November

When fires heat hall and chamber,

And I, within the house, keeping,

Until the coming of the spring,

Composing no message to her,

Writing, sealing, not one letter,

To despatch and send her way,

Passing my time another way;

And many an hour so did spend,

Until the winter-time might end

And my eyes could weep no more.

I had no wish now to adore

Her lovely portrait but, instead,

Removed it from above my bed,

And in a little closet placed her,

That rested within one greater.

There it is yet, and so shall stay

And so, remain there, locked away,

Nor will it leave its prison soon,

But rather rest there night and noon,

Because of the wrong my lady,

In seeking a new lover, did me,

At least such was said about her,

Which robbed me of joy and pleasure;

But then, to lighten my dolour,

Which had stolen all my colour,

Composed this ballad, although still

With heart afflicted, weak and ill,

And filled so with love’s malady

Tis ripe within the melody.

Lines 7663-7683: His ballad ‘Se pour ce muir qu’Amours ay bien servi’ (Ballad XLII)

‘If for this I die, that I’ve served Love well,

Ill would it be to have served that lord so,

Since I have not deserved the parting knell

For loving, thus, and with loyal love also;

I do know my days are numbered though,

When I perceive, and openly tis seen,

That in place of blue, lady, you wear green.

Alas, lady, I have cherished you so,

In longing for the sweetness of mercy,

That from me all my sense and strength do go,

So, do these my tears and sighs oppress me,

While hope is dead, beyond recovery,

Since Memory shows me; and tis clearly seen,

That in place of blue, lady, you wear green.

And so, I curse these eyes that first saw you,

The hour, the day, your charm, your address,

The rare beauty that struck my heart anew,

All that delight, enraptured foolishness.

And I curse Fortune, and her fickleness,

And Loyalty, that suffers it to be seen,

That in place of blue, lady, you wear green.’

(Translator’s note: While the significance of medieval colours varied, green was often, as it is here, associated with ill-luck, fickleness, death and decay, while blue was associated with good-luck, steadfastness, mercy and hope; analogues as it were of Earth and Heaven)

Lines 7684-7693: He receives her twentieth letter

NOT long after there came to me

A messenger who, suddenly

Arriving at my very door,

Said: ‘Your lady greets you once more,

And, by me, sends you her letter,

And none ever wrote a better,

No syllable might it lose indeed;

Read it now, please, and take heed.’

So, acting upon what he said,

I opened her letter, and read.

‘My most dear and sweet friend, I send you this message due to the very great and perfect desire I have to hear some good news from you, and may Our Lord grant me the grace to hear such as my heart desires. For I have heard nothing from you since Candlemas, while I have written to you since that time, most recently through your secretary. I also told him several things directly that he was to tell you of, and he promised me that he would do this in such a manner that I would have a response from you shortly, but you deign to do nothing in this regard, and so it seems that you have discarded me utterly and cease to care for me, and that you no longer feel any love for me, and in this you are wrong and do what is bad and sinful. But I pray God may never grant me honour or joy in anything I request of Him if I have ever, in word, deed, or thought, done aught to you which gave reason that you should abandon me in so, or place my heart in the kind of distress it feels for you, as you are well able to understand. And yet you care not; so, you intend no remedy. And, by God, my sweetheart, my heart was never so towards you, for I never felt good or joyful as long as I knew your heart was suffering, and as soon as I was aware of it, I did my best to comfort you. And I think you well know the great distress my heart feels concerning you, and yet you care naught about it, so I am more surprised at your manner than I would be by any other man in the world, for I believe there has never been any man who has protected and loved the peace, benefit, and honour of all women as much as you have done, even of those you never saw, who never loved you, nor did you any benefit. And I, who love you more dearly than all the men who are now alive, and more than any woman has ever loved you, feel through you so great a pain and anguish in my heart that I think no human heart could believe I endure even a tenth this much. And it is no wonder, for I run the risk, if you act not swiftly, of losing honour and all my joy, for you know that our affair is known to a number of good people, such that if they learned it had been broken off, they would believe I had played you false, or that you had found in me some vice or wickedness that had caused you to do so. And surely if this were the case, I would consider myself the most dishonoured woman in the world, and never would any good or perfect joy be mine. And so, my very dear and sweet friend, I beg you, please, as dearly and humbly as the sad and miserable heart of your true and loyal sweetheart yet can, you being the one in whom resides all my good, all my honour, and all my joy, that your tender heart, which has always been so sweet and humble toward all women, should not be so cruel toward me as to wish that I experience such pain. Rather may your great sweetness deign to rescue me from the great misery I am in, and grant me comfort and joy. And know for certain that this can never come from anywhere if it does not come from you. And if it is true that you have thrown me over completely without my having deserved it, and that your heart is so cruel toward me such that I cannot find either comfort or love there, I am the woman who should complain more of you than ever did a woman complain about her lover, more even than Medea did of Jason. And so I promise you faithfully, and I swear on all the holy things a Christian can swear upon, that if it is true that Love, whom I have served so long and so loyally, to whom I have entrusted my heart, thoughts, and affection, should take from me the thing I love most dearly in all the world, and of which he promised me benefit and perfect joy, I then renounce and deny him and his service completely. Nor will I ever be his slave, or endure such subjection, neither I nor any other woman I can turn away from him; nor will I ever grant benefit or pleasure to any man I know who claims to love me or to love any other woman over whom I have influence. Rather I will do as much to annoy and disturb them as I can, and all this to spite Love, who has caused me so much suffering. But, if you please, my very sweet friend, you may swiftly soften this anger if you would but treat me as the virtuous, faithful, and true beloved I am and will be all my life and believe none who say anything against me. And then, if you would be to me the virtuous and loyal friend you used to be, know for sure, that Love will never have been served or honoured as much or as faithfully as he will be by me because of my love for you. So, I beg and ask as humbly and affectionately as I can, and as a favour to me, that you would please send something in writing, by this messenger, of such a nature that I might be comforted, for you may know for sure that all my good, all my honour, and all my joy depends upon you. Adieu, my sweet darling, and I pray to Christ with a virtuous and loyal heart, and his sweet Virgin Mother as well, that He may give you honour and joy in whatever your heart desires, and that He may grant you the wish to do something that might restore my joy. Written this thirteenth day of November. Your true love.’

Lines 7694-7715: He replies with his twenty-first letter

NOW you have, if it pleased you,

Seen her letter, and kept in view,

How I was harassed by all, alway,

At every hour of every day,

Due to the love I held for her;

Nor was made happier, but rather

More displeased, as you have read,

By what, every day, was said;

You know the portrait, of the one

I loved, I had locked in prison,

Which yet did not deserve its fate,

Rather was most unfortunate,

Alas, though I had served it so,

Thinking that I, by doing so,

Might yet save myself by the deed.

As it was, I pondered, indeed,

Upon the matter and I thought

To write a letter yet say naught

Of what others had claimed as true,

That she wore green instead of blue.

Here is the form of my letter,

To explain its contents better.

‘My own sweetheart and my very dear sister and my very true love, I have carefully considered what you have written, and I thank you very dearly for informing me about your good health for, by my soul, the greatest joy I can have is to hear good news from you, next to seeing you, which is what I long for above all things in the world. And, my own sweetheart, regarding your message saying that you are in that place we know of, and that I may come to see you when I please, and also the plan you made concerning it, which pleased me much, since by it I see clearly that, as regards me, your heart is true and you are full of good will, for all these things I thank you as humbly as I am able, and not at all as much as I ought. So, I have sent my secretary, and I will come myself to you as soon as I can after Saint Andrew’s day, or even sooner if I am able, because plans sometimes alter. And I shall bring only three of my servants besides my secretary, if I can have him with me. My dear sweetheart, I know well that you own the power to make Argus slumber, and to prison Resistance and Ill-Speech, and by my soul I am very happy that this is the case, and I beg you, most lovingly, that till I have seen you they may remain so. And as soon as I depart, may they be set free to perform their office of guarding you against all other men. And my own sweetheart, do not fear that when I come to you, and this will be very soon if God pleases and I can so arrange it, I shall perform most wisely and secretly all you have demanded, and as for the rest I will wait upon your noble heart. Recommend me, most humbly, to Columbelle, for I am most eager to greet her for your sake. And know that, where you are, I am acquainted with none except you, so it is most necessary while I am there for me to do as you may direct. Recommend me to H… when you see him, and, be sure that, if he can visit me, I would be most honoured, and it would be a great comfort to my brother, who can find nothing good or joyful when I am away. I was having something made for you, in Paris, but I am told the goldsmith has since died, so I believe I have lost both my commission and the gold. My own sweetheart, you write to me in so open a manner, and have always written in such a fashion, that I know not if it is good that I should put your letters in my book exactly as they stand, so please tell me of your wishes in the matter. Adieu, my sweetheart, and may God grant you honour and joy in whatever you desire, and grant us grace that we might see each other in honour, joy, and good health, and that shortly. Written the thirteenth day of November. Your most faithful lover.’

Lines 7716-7737: The lover sleeps and dreams again

THIS letter to my lady went,

Written without plaint or dissent

Regarding the tales that I’d heard,

For I would not have said a word

To gain a county; not for aught,

Would I have spoken; I said naught,

For fear of rousing her anger

Had I relayed them in my letter,

And I would but have brought her woe;

No messenger can prove too slow,

Nor knock too tardily at the door,

Who carries such ill news, tis sure.

And now I lay down, on my bed,

Naked, joyless, to rest my head,

Musing upon this whole affair,

Its outcome sad and hard to bear,

Though sleep proved difficult to seek,

For, indeed, throughout that whole week

A hundred times more I had wept

Than ever I took my ease and slept.

I dreamt a dream; you shall read it,

Though perchance you’ll not believe it.

Lines 7738-7791: His dream of the portrait

IN my dream it seemed to me

That I, before my face, could see

That portrait of my fair lady,

And all dishevelled now seemed she,

And weeping with great tenderness

Sighing deeply, and to excess,

And with her hair she wiped her eyes

Her face, her breast, amidst her sighs,

Saying: ‘Wretched, alas, am I,

Within sealed casket here I lie,

Prisoned, my lord, and yet you know

There is no reason why tis so.

If someone’s led you to believe

Your lady’s seeking to deceive,

What then? What more now can I do?

Did I provoke it? No, yet you

Believe too readily that tis true,

And so twill turn out ill for you,

As shortly you will come to see,

And all the world, in company,

For you shall but lose your lady,

Who loves you, heart and soul, truly;

And suppose that she has played

You false, and your love betrayed,

For that must I now pay the price?

Alas, you’d dress me, in a trice,

In little love songs; I did hold

Precious gems and finest gold,

And cloth of gold from o’er the sea,

And now you would abandon me.

Is it right that I should suffer?

Why, no indeed, by Saint Peter,

For I’ve done naught. If aught’s awry,

No wrong in word or deed wrought I,

And, surely, she is not to blame,

Owns to no sin to mar her name;

I deem that there’s no truer lover,

God love me, the whole world over.

Play no games now, let her know,

And if she can disprove all, so,

Let her be cleared of infamy;

Whate’er the case, but hear the party,

For every true judge that we face

Hears both the parties in a case;

And yet you think to condemn her,

And from your good graces ban her,

Because some three or four folk claim

Falsehoods that must mar her name,

As venomous as snakes, pure lies,

Told by slanderers, serpent-wise.

Tis a sin such tales to credit,

And a greater to admit it;

And there’s a tale, regarding this,

I might tell, if tis your wish.’

Lines 7792-7845: The tale of how the crow’s feathers became black

‘NOW, once upon a time, the crow

Had feathers whiter than the snow,

Or dove, or goose, or swan, whiter

Than the hawthorn-flower, and brighter.

In brief, he was in no way ugly,

Whiter than milk in his beauty,

And dearly did Phoebus love him,

And he delighted more in him

Than in his bow, or in his lyre,

On which to play was his desire.

I’ll tell you how it came about

That black was in and white was out.

In Thessaly there lived a maid

Who put all others in the shade,

Fair, fine, more praised for her sweet grace

Than any other in that place.

Being a native of Larissa,

There was nothing coarse about her,

For she was courtly, witty, wise,

Her lineage naught to despise.

Coronis was this maiden’s name,

And Phoebus truly loved the same,

With all his heart, his love so true

He ever kept that maid in view.

But a young man she preferred

More than Phoebus his white bird,

In brief, she cared for nothing more,

As the tale will show, I feel sure;

For the crow saw them together,

Conjoined, in the way of Nature,

Each partaking of their pleasure

As Mother Nature teaches ever.

Now, on spying their lechery,

The crow began cursing loudly,

And then a great oath he did swear

That, once he’d taken to the air,

Phoebus should the unchastity

Of his beloved know instantly,

He flapped his wings hard, then he flew,

Without another word and, true

To his oath, to tell Phoebus all

Of what betwixt them did befall.

How he had found them both, indeed,

Caught, in flagrante, in the deed.

Now the raven he did encounter,

Who flew up and asked wherever

Was he going, so eagerly,

As he passed her, full hastily;

The crow gave her a swift reply,

The tale he told, how he did spy

Coronis, her unchastity,

And that to Phoebus he did flee,

For he wished not to hide her shame

From his lord, but speak the same.’

Lines 7846-7881: The raven reproaches and corrects the crow

‘NOW, once she’d heard all the affair,

She answered: “Crow, this much I’ll dare:

Trust me on this, my words obey,

Turn around, fly the other way.

Attend to what I teach, for I

Speak never a word of a lie.

Tis not good always truth to utter;

Think you that Phoebus, your master,

Will not be sad, make no mistake,

Or that his sorry head won’t ache,

If sheer faithlessness you prove

In that Coronis who is his love?

Think you his gratitude to see;

That you’ll be raised to high degree?

No, for he, in truth, will hate you,

Never a good thing will wish you.

(The speaking portrait said a word

Above worth noting, as we heard:

Ne’er comes tardily anywhere

The one who doth ill tidings bear.)

Mischief befalls truth-speakers so,

And again, you must surely know

How ill-luck may thence befall you,

And I know what I’m saying too,

For I was mistress, once, alas,

In the house of grey-eyed Pallas,

And there I met with much honour,

And yet fell into dishonour,

And all for the true words I said;

To what injustice have they led!

Heed my warning; change direction,

Here now I’ll offer you correction;

For he amends his course nobly

Who’s taught by another’s folly.

Come, what happened to me, know;

Twas more than twenty years ago.”

Lines 7882-7987: The raven’s story (cf. Ovid’s Metamorphoses Book II)

“I was lady, once, and mistress,

In the mansion of the goddess,

Pallas, and I did please her so

She granted me more favours, know,

For my service than any other,

If you would learn why, however,

I was banished far from her court

Then listen to my tale; in short,

Vulcan, who’s old and much despised,

(Fierce gout in him be realised!)

Who forges lightning-bolts that strike

On working days and feasts alike,

And does so solely out of anger,

Loved fair Pallas with such ardour

He asked her if she’d sleep with him,

Yet she refused to yield to him,

A woman pure and wise and good,

Thinking to guard her maidenhood.

For a long while he pursued her

But she fled before her suitor,

This enemy, wretchedly begot,

Upon a time, he grew so hot

He spilled his seed upon the ground,

And then the earth split all around,

And from the earth, there, was conceived

A child whom fair Pallas received,

Erisichthon he was named that day,

And, sadly, he was hid away,

Yet I exposed him, foolishly,

With my raucous minstrelsy.

I’ll tell you, now, of the little one,

Who was shaped in wondrous fashion,

For Nature, who the child had made,

A dual form in him displayed,

And Pallas shut him in a coffer

And then she swore by Saint Onofre,

That she’d determine what might be,

And have him guarded carefully,

She not wishing it to be known

How in the earth that seed was sown.

Then to three Cypriot sisters,

Whom she considered wholly hers,

She handed him, in Athens to lie,

Ensuring none should cast an eye

Inside the coffer, that none might see,

Because she wished that secretly

They might raise the little creature,

Its birth so contrary to Nature,

For, in truth, it lacked a mother,

Born of the seed of its father.

Pandrosus was the eldest sister

Next came Herse, and then after

The youngest, Aglauros by name,

And most ill-advised, for that same

Forced open the infant’s coffer,

And so, the secret did discover.

I was perched on a tall oak-tree,

Preening myself, whence I could see

All that was happening below,

How Aglauros, eager to know

What might lie inside the coffer,

Came now to unlock its cover.

And all this I could clearly see,

If not better, then as well as she.

I saw the child had snakes for feet,

Slithering thus about its retreat,

For I saw the dual form, once hid,

As Aglauros threw back the lid;

She opened it seated on a chair,

I know not if she closed it there,

For I took flight, straight away,

And then to Pallas made my way,

To give the goddess true report,

Croak by croak to her, hiding naught,

Saying who had its depths revealed,

And shown the secret it concealed,

Expecting indeed that she’d accord

Me the gift of a fine reward.

I knew not what brought it about,

But instantly she drove me out,

Banished forever, beyond recall,

And I dared never return at all.

And then, what is hardest to bear

In all this most sorry affair,

Is that she gave my place there

To the owl who’s scarcely fair,

Rather is filthy, vile, unclean.

There her beaked, hooded face is seen,

In place of mine; she governs all;

In house and inn, she casts her pall,

That soiled wretch, that filthy bird,

May God consume her, in a word!

She only flies abroad by night,

All hate her, and all flee her sight,

Never a bird doth wish her well,

All complain of her; sad to tell

She e’en sleeps with her own father;

And yet Pallas so prefers her

I feel such pain with every breath

That surely it must cause my death.

Now you can readily perceive

What prize truth-telling doth receive,

And so, dear Crow, I counsel you,

To follow my advice; tis true,

And you’ll recall, what all do say:

Ill doth the goat, scratching away.”’

Lines 7988-8039: The crow reports the affair to Phoebus

‘THE crow replied that he would not,

That resting ne’er would prove his lot

Till he had flown and told Phoebus

The truth of the wretched business.

He flapped his wings and off he flew,

Though badly schooled in my view,

Since often things prove contrary

When one speaks that should silent be,

For they’ll be paid the wages earned

By gossips, who are rightly spurned,

Or those dealt out, with good reason,

By those who are of noble station.

The crow went sailing through the air,

Eager to tell of the affair,

Taking no known path or highway,

But searched about, and did so stray

He came at last to Thessaly,

And to Phoebus’ palace, richly

Adorned with gold, gems, and silver,

Where music from his harp did ever

Sound softly, sweetly through the hall

And then so wound about it all,

Ne’er a chamber or tower was there

That its melodies failed to share,

For all around could hear its voice;

And now the white crow did rejoice,

Hearing the rich notes sounding so,

Expecting a rich reward also.

And yet he failed of his intent,

Like the swan was he, all spent,

That on the brink of death doth sing;

He’s a fool that tells everything,

All of the truth that may displease,

To his master when he’s at ease.

And truly too much talk annoys

Especially that the gossip employs,

Unwelcome ever, day or night.

Spying Phoebus’ house, outright,

The crow sped swiftly through the air

And with all speed descended there.

Phoebus saw him, and did demand

Why he came, as he sought to land,

Since he’d been absent many a day,

Gone seeking pleasure far away.

The crow at once relayed the tale

Of shame and outrage, without fail,

Of Coronis’ vile lechery,

Said to his lord, most forcefully:

“Fair Sire, by every sacrament,

I spied them upon vileness bent,

And I was intent on telling you,

And here I am, and tis all true.”’

Lines 8040-8105: Coronis is punished by Phoebus

‘WHEN Phoebus had heard the story

From the crow, about that lovely

Maid he loved with all his heart,

That she for another did depart,

From his head the crown did fall,

And the harp, that filled the hall

With its soft notes, fell at his feet;

His grief had not been more complete

Had he been pierced by twin sword-blows

Through the body, for, heaven knows,

Twas sorrow the crow had brought him,

Learning that she’d been false to him.

It is not necessary to tell

All the truth, if all would be well,

Nor even a quarter, truly,

Need be said; may God preserve me!

Phoebus tormented himself sadly,

Complaining, and raging madly,

Such was his misery and woe,

Filled with pain and anger also.

By chance the maiden he did spy,

Listen now to how he let fly:

He seized a bow, strung an arrow,

And pierced Coronis to the marrow,

Because he had been thus betrayed;

Deep in her breast he struck the maid.

Coronis fell straight to the ground,

Her heart failed, her sight she found

Grew dim, and from the wound there ran

A stream of blood, on every hand.

Dying she murmured, soft and low:

“Alas, to bring on me such woe;

I see that shortly I must die,

And yet tis undeserved, say I,

For I have served you faithfully,

My love, you’ve acted hastily,

For two you have killed with one blow;

I am with child, and you must know

Tis yours, and it has done no wrong;

Sweet friend, to you it doth belong.”

And with this her soul she rendered,

Phoebus saw naught could be mended,

And, hearing her reproach, no less

Was he shamed, and in sore distress.

And angered, bitter, made outcry

Against all birds that course the sky,

And most especially the crow,

Who had the fairest form also.

He cursed the arrow and the bow,

And the hand that brought him woe,

The hour, the season, and the dawn,

That this most evil day had borne.

He had the maid embalmed too,

With richest ointments, and tis true

That they so skilfully did strive

That she did seem as yet alive.

In the temple of the goddess

Venus, he placed her corpse, no less,

Yet, ere he placed her in the tomb,

He took the child from out her womb,

A child that later won great fame,

Aesculapius was his name,

And he of surgery knew more

Than any who had lived before,

For to life he restored the dead,

So, in the books, indeed, tis said.’

Lines 8106-8131: The crow receives his ill reward

‘THE crow a fine reward now sought

Though twas ill-tidings he had brought,

Awaiting, and longing for, that same,

Yet the messenger shared the blame,

For Phoebus said: “In memory

Of this, your feathers black shall be;

Instead of white, now, on its back,

Let every crow be dressed in black,

Blacker than ink for evermore.

No other lot have you in store,

Due to your wicked gossiping

That robs me thus of the loving

Charms of the fairest ever sent

To this world, who yet innocent

May be, and all this but a lie

That makes me woeful, sad of eye;

Do naught but jabber now I say,

May the eagle snatch you away!

Be off! An exile from these shores,

Show your beak, and shame is yours.”

With this reward the crow was paid,

He flew from there, quite dismayed,

And then, as all folk know, in brief,

Once banished, he became a thief;

And everywhere he doth repair

Does naught but caw and jabber there.’

Lines 8132-8179: The portrait image continues to admonish the lover

‘MY lord, you’ve listened to my tale,

And learned I deem, without fail,

The lesson of raven and crow,

And I’d be amazed, it being so,

If such gossip you’d still believe.

Lend a deaf ear to all you receive

By way of news from those who seek

But to deceive you when they speak;

You’ll sin gainst her nobility,

To credit what wounds so deeply.

Life and honour, by such action,

And your sweet love’s affection,

You would forfeit, believing so,

Slay your lady and then, in woe,

Sigh with repentance, I dare say,

And curse, a hundred times a day,

The hour that brought you such report,

And those who all such gossip taught,

The place, the harm that did befall,

Now clear and evident to all,

As Phoebus did; and all too late!

And so, for God’s sake, heed the fate

Of Phoebus who repented ever,

For he’d pledged to love no other

Than Coronis, who had deceived,

Him; he who had the crow believed.

Would it might please God that they

Who harm love, in this foolish way,

Through gossip, truthless and malign,

Be turned to wild and savage swine,

Or be transformed to trees, or bare

Black polished marble standing there,

So they might change from light to dark,

Dressed in coarse pelt, stone, or bark,

Just like the crow, banished no less,

For his sin, from the god’s palace,

On pain of death, whom, you’ll recall,

The other birds loathe, one and all.

My lord, now I’ve so lectured you

You can see my reasoning’s true,

And from prison I should be freed,

And my honour restored, indeed,

I should be seated now on high,

As I once was; if not, then I

Shall appeal to fair Venus’ grace,

And I shall plead your lady’s case,

Before her thus, and contest yours,

For she’s none to defend her cause.’

Lines 8180-8201: The dreamer wakes

BUT now the watchman gave his cry,

The cowherd sounded, loud and high,

His echoing horn that, as he blew,

Thus, served to waken me anew.

And, once from sleep I was freed,

I was full of wonder, indeed,

And all my blood within was stirred

By what I’d seen, for I’d ne’er heard

Of like image, in any age,

Whether on wall or written page.

And yet her lips spoke not to me,

Rather Morpheus, in his mastery,

Took on her portrait’s form outright,

Came to my bed in darkest night,

Where I slumbered, dreaming deep,

And whispered to me, in my sleep,

The request and the true complaint

Of those lips reproduced in paint.

Whoever knows not Morpheus

To whom I’ve seemed oblivious,

They may read ‘The Amorous Fount’,

Wherein of him I give true account.

Lines 8202-8261: He reinstates his lady’s portrait

AND so, I thought and thought again,

And, while thinking, it seemed plain

That I’d wronged her; and oftentime,

He errs, and doth commit a crime

Who imprisons some poor creature,

Though never a misdeed did feature.

So, I rose from my bed and dressed,

And, once done, I unlocked the chest,

Where the portrait now did dwell

Of she whom I had named ‘Toute Bele’,

And said: ‘Are you within, my beauty?

I ask forgiveness and pray mercy,

For having prisoned you so nearly,’

Addressing her with great courtesy,

With my right hand setting her free,

Placing her where she used to be,

Quite as honourably as before.

And afterwards I mused once more,

And pondered on the errant crow

And on the wise raven also,

Whom Phoebus and Pallas hated

Due to the truths they’d related,

Recalling all that they did discuss,

And I agreed with Morpheus

A fool he is who bears a message

That brings but anger and damage,

Especially where Love’s concerned,

For none has such perfection learned,

That if he’s struck so by Love’s lance

He’ll not feel, through that circumstance,

Anger, displeasure, at ill report

Of his lady in misdeeds caught;

Nor should you, if you’re awake,

Wonder at all, if my mistake

Made me sigh and moan and weep,

And afforded me but little sleep,

Once the news was brought to me

That her beauty was lost to me.

My heart was so filled with worry,

That, by that same God that made me,

So greatly troubled then was I

My heart near broke, I’ll not deny.

Then Love, and Fortune too, I cursed

That I so ill a fate rehearsed,

Though they’d promised endlessly,

A hundred times or more to me,

That she would forget me never

My Toute Bele, nor alter ever.

Yet her promise she’d not kept

If what I’d heard before I slept

Was true, her loyalty but lies,

Nor shall my tale say otherwise.

Yet the man who feels discomfort

Must look about to find comfort,

And so, did I; from a shelf I took

For like purpose, a little book,

Twas writ by one Fulgentius,

And therein Titus Livius

Describes how Fortune doth appear,

And what he says there, I’ll give here.

Lines 8262-8311: Livy’s description of Fortune according to Fulgentius

THE matrons of Rome long ago

Founded a temple, and did owe

Its creation to no man there;

It was solely Woman’s affair.

They to Fortune’s honour raised it,

And agreed to further adorn it

With her form in female semblance,

An image of her true inconstance,

For tis true they are unstable,

Women that is, and variable.

Fortune no one at all should prize,

But rather her should one despise

Who comes free from simplicity,

Or in bare and ragged poverty.

For such folk they do best, I say,

As can hold to the middle way.

The image I’ll describe for you

Was fair of face, and body too,

Four little roundels met the sight

Two on her left side, two her right,

And a large one that did aspire

To hold the four small ones entire.

And the first circle there did hold

This text, in Latin, writ in gold:

‘Free of limit, I grant and share;

I make such games my true affair.’

And in the second there was writ,

As though to test the gravest wit:

‘Cherished am I, while I do last,

Yet thought bitter when I am past.’

The third text was most notable,

Nor should it be thought a fable:

‘I render thought blind and, with ease,

I cause the love of God to cease,’

Yet one should love God faithfully

Who made the sky, and earth, and sea.

Now in the fourth was written, there,

A thing of which all should beware:

‘I sing and sport, yet in such wise

That my song lies, cheats, falsifies.’

The fifth, encircling all, brings down

The king, the sceptre, and the crown,

Bearing all things to destruction,

Here appears the harsh conclusion,

For all those who fail to scorn her,

But rather follow her and prize her.

And here I give the true text, thus,

As writ by Titus Livius:

‘Look on, and think what I may be,

And when you know, loathe me, and flee.’

Lines 8312-8327: The lover considers the image of Fortune

THUS, did one the likeness portray,

Of Fortune, there, who doth display

Spite, hatred; shames, works to deceive

All those who do her grace receive.

Long and hard I viewed her pose,

Took issue in my heart with those,

That once had taught me to believe

In her love, who did but deceive,

For I and joy must perish too,

If what was said of her was true.

Yet, by my faith, I was in doubt

So set myself to think about

My lady and to compare her

To Fortune and all her manner

Of behaving and, in this wise,

Viewed the two as I here advise.

Lines 8328-8343: His response to the first emblem

WHEN I, at first, did fall in love

With my lady who mine did prove,

So sweet the woman that I saw

That later I could not withdraw.

Yet I know not by what attraction

I lost my heart, so swift its action,

To one who thence did yet depart,

After she had so pierced my heart

With her glance and, fatal error,

Drove me on, at sight, to love her.

And so to Fortune I liken her,

And I can rightly compare her,

In heart and body, all her ways,

To Fortune and the games she plays,

If all is true that I’ve heard said;

Naught else my tale says, when read.

Lines 8344-8359: His response to the second emblem

ALAS, I have held her so dear

Without deceit have loved her here,

That in truth I knew not whether

I saw and heard her, yet forever

She was my heart, she was my love,

She did my loving refuge prove,

My desire she was, my treasure,

My joy, my hope, all my pleasure.

Ah me! Ah me! Ah me! Ah me!

And yet her love has died for me,

Vanished is her grace and favour,

To gall doth her sweetness alter,

Which to me was nurse and mother,

Now like to death, sour and bitter,

If all is true that I’ve heard said;

Naught else my tale says, when read.

Lines 8360-8375: His response to the third emblem

SO lovingly I’ve cherished her

And so humbly have I served her

That on her all my attention

Was bestowed, mind and intention,

My heart, my pleasure, all my thought

Never to be withdrawn for aught.

For her great beauty so fired me,

And her sweetness so inspired me

That I neglected my Creator,

For her person, every feature,

Nor in the world did any creature

Save her grant me such pleasure,

Yet in love she has betrayed me

And without due cause doth hate me,

If all is true that I’ve heard said;

Naught else my tale says, when read.

Lines 8376-8391: His response to the fourth emblem

FAR sweeter than the Siren’s call,

Filled with sweet melodies, in all,

Is her voice who, with her singing,

Lulls my heart, my flesh enchanting,

Just as cruel Fortune enchanted

All her sad slaves when she chanted

Her falsehoods, their minds deceived;

She’s false, and ne’er to be believed.

My lady played me false; the same

Is she, and plays that wicked game,

She’s like the fickle wind that blows,

And where it goes to no man knows;

So, she bestows her graces quickly

And then withdraws them as swiftly,

If all is true that I’ve heard said;

Naught else my tale says, when read.

Lines 8392-8409: His response to the fifth emblem

WHEN I first did meet my lady

Viewed her person, sweet and lovely,

I looked not to the beginning

Foolishly, nor to the ending,

For tis said that he works wisely

Who his labour’s end can see.

Yet foolishly I’ve gone astray

Since tis certain many a day

Of pain and care will be my lot,

For Fortune will ne’er be forgot,

And if one sees her, flee again,

Quick as a cat doth flee the rain.

Alas I have followed my lady,

When I should have fled her swiftly.

Deceived myself, I thus consider,

For I should have known her better,

If all is true that I’ve heard said;

Naught else my tale says, when read.

Lines 8410-8423: He concludes his comparison of his lady to Fortune

NOW, my lady has been compared

To Fortune, all their likeness shared.

The two of them go well together

Since she, like Fortune, is forever

Marked by variability

In which lies no stability,

And truly she doth change anew,

As a sparrowhawk does, in mew;

Though its plumage it doth alter

While her heart it is doth falter.

She is skilled at changing course,

Varying in like flight, perforce,

If all is true that I’ve heard said;

Naught else my tale says, when read.

Lines 8424-8473: The treatment of the falcon that strays

ABOUT this I’ll relate a story,

Recounted by the Count to me,

Who is my lord and noble friend,

And one who closely doth attend

To the fine sport of falconry,

For none knows more of it than he,

Nor enjoys the thing more fully,

Tis his great pleasure, certainly,

Therein is nigh all his delight.

Now when his falcon, in its flight,

Veers off course, he’ll curse, call out,

Scream and yell, and cry and shout,

Until the falcon hears the sound.

All the falconers, I have found,

The sport entrances, do likewise,

And, when the falcon hears the cries,

If tis well-bred, twill find the way

To renew its course, sans delay,

Turn, and then, the true path seeking,

Set itself on the proper bearing,

To chase down its previous prey,

Seize its quarry, nor veer away.

The Count then shows it kindness,

Praises it and, with much sweetness,

Reveals a face of such good cheer

That e’en to the falcon it is clear

That the man is more than happy

With its service, since it has fully

Discharged the task that it was set.

And so, the Count must not forget

To yield it the heart of the prey;

That’s why it flies: to hunt, I say.

He feeds it the bird’s heart there,

On the lure; thus, ends the affair.

But if despite his shouts and cries,

Or whatever other means he tries,

The falcon chooses not to forego

The wrong quarry, it follows so,

And if it then takes it in the air,

The noble Count, in pure despair,

Treats the falcon rather brusquely,

Speaking to the ill thing harshly,

While if it bears back the quarry,

Which it seized erroneously,

The count throws it in the river

Or the mill sluice, or wherever;

So, of its feast the falcon fails,

Lost is the heart, and the entrails.

Naught else it gains for its mistake,

Such is the vengeance he doth take.

Lines 8474-8493: His attitude to his lady’s fickleness

THUS, if the lady whom I prize

Sins somewhat against me, likewise,

I should also raise my clamour,

But piteously and in fear of her,

Like a man who dreads her anger,

Praying her not to stray further.

And, if she should amend her flight,

Then I should forgive her, outright,

And do so most affectionately,

And sweetly, and with courtesy.

And, if she fails to show reason,

And casts away the love she’s won,

Then I must let her have her will

As she proves unreasonable still,

And, without further plaint or cry,

Yield her thanks, my head held high,

And say to her, and most politely:

‘As you please, I concede wholly.’

For her love is worth less than naught,

To me, since others’ love she’s sought.

Lines 8494-8509: He sends his lady his twenty-second letter

YET in the end I concluded,

No longer foolishly deluded,

I could, no longer, live this way

Right melancholy, night and day,

With a heart now saddened wholly,

A thing which doth wound most deeply.

So, once more, I wrote a letter,

In which, courteously, I told her

Not the whole of what I’d heard

But that a true friend had brought word

That she was showing my letters,

Freely, to a host of others,

Which was but bitter news to me

Since I was now the butt of many.

That letter, you may read it now,

If its perusal you’ll allow.

‘My most dear and only lady, I am most anxious to learn how you fare, and so I beg you as humbly as I can, to let me know of your state, as soon as you can, for, God knows, one of the greatest joys I can attain is hearing good news of you. And if you wish to know how I am, I was in good health, and quite well when this letter was written. My most dear and only lady, if I repeat to you what has been told to me, I beg you not to be displeased. Be pleased to learn that a powerful man, who is very much my lord and friend, has told me, of a certainty, that you show what I send you to everyman, and thus it seems a fine jest to many. Do what you wish in this regard, but, though I am little worthy, I have been many a time in places where such things were not done, and where the man, or woman, who could best conceal their affairs from others was the one most worthy of reward. So, in order to protect you, I no longer intend to write aught that you could not show to anyone, and, my sweet love, I shall show the semblance of loving some other woman, entirely. And, to be sure, I have composed no more of your book since Easter, for the above reason, nor do I think to do so, for I lack material, and yet one should not believe everything one hears. I am sending you whatever I have composed lately of your book, and you may show it to whomever you please, for. by my faith, I took great pains in the making. And though you may consider it worthy of mockery, by my soul, there are hardly three persons in the world for whom I would have undertaken to do such a composition, however easy it might prove to another. But if sweet pleasure and pure love be absent, it proves most difficult for me to compose. My most dear and sovereign lady, may the Holy Spirit bless and protect you, and grant you honour and joy in whatever your heart desires. Written this 16th day of June. Your most faithful friend.’

Lines 8510-8525: His lady is distressed at his letter and composes a ballad

WHEN my lady read my letter,

Learning, as she looked it over,

Of the stories that some other

Had, it seems, reported of her,

My letter dropped to the floor;

Never had human form before

Suffered from such grievous pain,

The colour from her face did wane,

The crimson and the white grew pale,

A deathly hue did there prevail.

Fainting, she fell upon the bed,

Bowing down her face and head,

And weeping most piteously,

While moaning and sighing deeply;

Yet, in this state of woeful thought,

To make a virelay she sought.

Lines 8526-8572: Her tenth ballad, a virelay ‘Cent mille fois esbahie’

‘DISMAYED a hundred thousand times,

More angry, sorrowful, betimes,

Truly, than any, am I,

Since by this same man, hereby,

Am I cast aside, wholly,

Though he his friend, and lady,

Called me, and then so sweetly.

To my mind, there’s none other

Who could e’er suit me better.

I’d feel joy, free of anger,

If I could listen longer

To his voice, and keep in view,