Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part XVIII: Appendices – 1 to 8

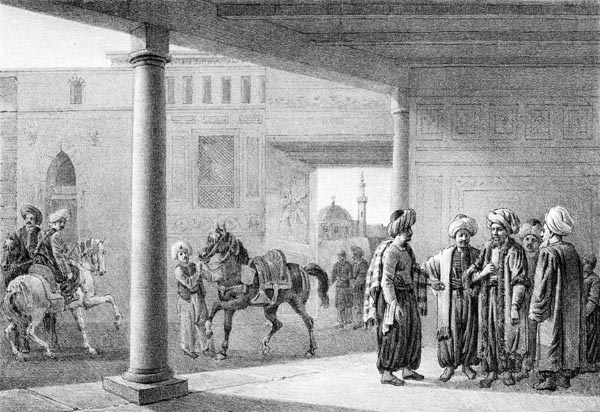

A country house near Cairo, 1828, Otto Baron Howen

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- The Manners and Customs of Modern Egyptians.

- Appendix 1: Regarding the Condition of Women.

- Appendix 2: Female Seclusion in Cairo — Customs of the Harem.

- Appendix 3: Particular Celebrations.

- Appendix 4: Egyptian Dancers.

- Appendix 5: Jugglers and Entertainers.

- Appendix 6: The Houses of Cairo.

- Appendix 7: Funeral Ceremonies.

- Appendix 8: The Population of Egypt.

The Manners and Customs of Modern Egyptians

Appendix 1: Regarding the Condition of Women

The current period of literature is similar to that which inaugurated the second half of the eighteenth century. Then, as now, writers were drawn to the curious, to eccentric investigations, to paradox, in a word. If paradox, as has been said, ruined the eighteenth century, how will it affect ours? Do we not recognise, herein, the most incoherent mixture of political, social, and religious opinion seen since the late Roman empire? What we lack is a multi-faceted genius, capable of providing a rational view of all such misguided fantasies. In the absence of a Lucian (of Samosata) or a Voltaire, the majority of the public will take only a limited interest in the immense work of decomposition at which so many ingenious writers are labouring.

The eighteenth century published a defence of Islam, just as it tried to resuscitate Epicureanism and the theories of the Neoplatonists. Let us not be surprised, given the works now appearing, once more, concerning those latter subjects, if we find some author raising among us the standard of the Prophet. That would be scarcely stranger than the announcement of a mosque being built in Paris. After all, that would only be just, since Muslims allow our churches in their countries, and their princes visit us as the kings of the East once visited Rome. Great things may result from the friction of two civilisations long hostile to each other, which may rediscover previous points of contact by ridding themselves of the prejudices that still divide them. It is for us to take the first steps and rectify our many errors and wrong opinions regarding the customs and social institutions of the East. Our role in Algeria, especially, makes this a duty for us. We must ask ourselves whether we gain anything by our religious propaganda, or whether it would be more appropriate to limit ourselves to influencing the East through our civilisation and philosophies. Both are equally in our hands; it would be interesting to discover if we could not draw, from such a study, lessons of our own.

When the French army seized Egypt, there was no lack of moralists and reformers in its ranks determined to shine the torch of ‘reason’, as it was then called, on those ‘barbarous’ societies; a few months later, Napoleon himself invoked the name of Muhammad in his proclamations, and General Jean-Baptiste Kléber’s successor, Jacques-François Menou, embraced the religion of the vanquished; many other Frenchmen, then and since, have followed this example, yet, compared to the few illustrious figures who have become Muslims, one would be hard pressed to cite well-known Muslims who have become Christians. This might seem perhaps to prove that Islam offers men certain advantages which do not exist for women. Polygamy may, indeed, have tempted a few superficial minds from afar; but this motive can have no influence on anyone who studies, closely, the genuine customs of the Orient. A certain Monsieur de Sokolnicki brought together, in a work which is perhaps a little paradoxical, but in which one finds much observation and science, all the passages of the Koran, and some other Oriental books, which relate to the situation of women (see ‘Mahomet, Législateur des Femmes, Ses Opinions sur Le Christ et Les Chrétiens,’ by Michal Sokolnicki, second edition 1846). The author found little difficulty in demonstrating that Muhammad established neither polygamy in the Orient, nor female seclusion, nor slavery, all of which should no longer even be a matter for discussion, while he endeavoured to highlight the efforts of that legislator to temper and moderate as much as possible the ancient and enduring institutions of patriarchal life, which had always varied according to nation and clime.

The idea of the baser nature of woman, and the tradition which presents it as the primary cause of the sins and misfortunes of the human race, is found especially in the Bible, and consequently, influenced all the religions which derive from that text. The idea is no more marked in Islamic dogma than in Christian dogma. There is, it is true, an old Arabic legend which I summarise below, which outdoes even the Mosaic tradition; however, I scarcely believe it was ever taken entirely seriously:

The Orientals are known to accept Adam as being the first man in the material sense of the word, but, according to them, the earth was first populated by the divs or elementary spirits, previously created by Allah in a high, subtle, and luminous manner. After having left these pre-Adamite populations to occupy the globe for seventy-two thousand years, and having tired of the spectacle of their wars, loves, and the fragile products of their genius, Allah wished to create a new race, more intimately connected to the Earth and better realising the difficult union of matter and spirit. That is why the Koran says: ‘We created Adam partly of sandy earth, and partly of silt; but, as for the genies, we had created and formed them, verily, of burning fire.’ Allah therefore created a form composed chiefly of this fine sand, the colour of which gave Adam his name (red), and, when the figure was dry, exposed it to the view of the angels and divinities, so that each could give his opinion of it. Iblis, otherwise called Azazil, who is the equivalent of Satan, touched the figure, striking it on the belly and chest, and perceived that it was hollow. ‘This empty creature,’ he said, ‘will desire to fill itself; temptation has many ways of penetrating it.’ However, God breathed life into the nostrils of Man, and gave him as companion the notorious Lilith, one of the divs, who, following the advice of Iblis, was later unfaithful, and was decapitated. Eve, or Hava in the Islamic tradition, must therefore have been Adam’s second wife. The Lord, having understood that he had been wrong to combine two very different natures, chose on the second occasion to extract woman from the very substance of man. He plunged the latter into sleep, and began by extracting one of his ribs, as in the Bible legend. But here a different nuance is present in the Arabic tradition: while Allah, busy closing the wound, had lifted his eyes from the precious rib, laid on the ground beside him, a monkey (qird), sent by Iblis, gathered it swiftly and disappeared into the depths of a nearby wood. The Creator, greatly annoyed by this, ordered one of his angels to pursue the animal. The latter sank ever deeper among the branches. The angel finally managed to seize the creature by the tail; but the tail remained in his hand, and that was all he could bring his master, to bursts of laughter from the assembly. The Creator gazed at the object, in disappointment. ‘Well,’ he said, at last ‘we will use what we have.’ And, yielding perhaps to the vanity of the artist, he transformed the monkey’s tail into a creature beautiful externally, but full of malice and perversity within.

Should one see in this tale only the naivety of primitive legend, or traces of a kind of Voltairean irony which is not foreign to the Orient? Perhaps it would be helpful, in order to understand it, to relate the first struggles of the monotheistic religions, which proclaimed the lesser nature of woman, to a hatred of Syrian polytheism, where the feminine principle dominated under the names of Astarte, Derceto (Atagartis) and Mylitta (Mullissu). The idea that the first source of evil and sin preceded Eve herself can be traced to those who refused to conceive of an eternally solitary Creator, they spoke of a crime so great committed by his ancient divine spouse, that after a punishment before which the universe trembled, it was forbidden to any angel or earthly creature to ever pronounce his name. The solemn obscurities of primitive cosmogony contain nothing more terrible than this wrath of the Eternal Being, eclipsing the very memory of the mother of the world. Hesiod, who depicts at such length in his Theogony the monstrous births and struggles of the mother divinities of the Uranus cycle, presents no darker a myth. Let us return to the clearer concepts of the Bible, which softened and humanised are even more in the Koran.

It has long been believed that Islam places women in a far inferior position to men, and makes them, so to speak, slaves to their husbands. This idea fails to stand up to serious examination of Oriental custom. It should rather be said that Muhammad greatly improved the condition of women.

Moses declared that the period of impurity of the woman who gives birth to a girl and therefore brings into the world a new cause of sin, should be longer than that of the mother of a male child. The Talmud excluded women from religious ceremonies and forbade them entry to the Temple. Muhammad, on the contrary, declares that woman is the glory of man; he allows her entry into mosques, and gives her as models Asia, the wife of Pharaoh, Mary, the mother of Christ, and his own daughter Fatima. Let us also abandon the European idea which claims Muslims deny that women have souls. There is another opinion still more widespread, which consists in thinking that the Turks dream of a heaven populated by houris, always young and virgin: this is an error; The houris are simply their rejuvenated and transfigured wives, since Muhammad prays that Allah will open Eden to the entry of all true believers, as well as their parents, wives and children who have practiced virtue. ‘Enter Paradise,’ he cries; ‘you and your companions, rejoice!’

After this, and many other quotations that I could give, one wonders where the prejudice still so common among Europeans derives from. Perhaps we should not seek any other source than that indicated by one of our European authors (George Sale, see his translation of the Koran, 1734). It arose from ‘the answer Muhammad returned to an old woman, who, upon her desiring him to intercede with God that she might be admitted into paradise, told her that no old woman would enter that place; which setting the poor woman a-crying, he explained himself by saying that God would then make her young again.’

Moreover, if Mahomet, like Saint Paul, grants man authority over woman, he is careful to point out that it is in the sense that he is obliged to support her and provide her with a dowry. In contrast, Europeans demand a dowry from the bride.

As for widows, or women in any capacity who are free, they have the same rights as men; they can buy, sell, and inherit; it is true that the daughter’s inheritance is only a third that of a son; but, before Muhammad, the father’s property was shared only between children allowed to bear arms. The principles of Islam are so little opposed to the subjugation of women that one can cite in the history of the Saracens a large number of absolute reigns by Sultanas, without considering the effective power exercised from the depths of the seraglio by the Sultana Mother, and the Sultan’s favourites. In our own day, the Arabs of the Lebanon conferred a kind of honorary sovereignty on the illustrious Hester Stanhope.

All European women who have visited harems agree in praising the happiness of Muslim women. ‘Upon the whole,’ says Mary Wortley Montague, ‘I look upon the Turkish women as the only free people in the Empire.’ (See her letter of April 1717 to Lady Mar) She even pities, somewhat, the fate of husbands there, who are generally obliged, in order to conceal their infidelities, to take even more precautions than in our own country. This last point though is perhaps only true with regard to Turks who have married a woman from a noble family. Lady Morgan (Sydney Owenson, the author of ‘Woman and her Master’, 1840) rightly observes that polygamy, only tolerated by Muhammad, is much rarer in the East than in Europe, where it exists under other names. It is therefore necessary to renounce entirely the idea of those harems described by the author of the Persian Letters (Baron de Montesquieu), where the women, having never viewed a man, were forced to find the terrible and gallant Usbek amiable. In the streets of Constantinople, many a traveller has met the women of the seraglios, not, it is true, traveling on foot like most other women, but in carriages or on horseback, as befits ladies of quality, but perfectly free to view everything and to talk with the merchants. Such freedom was even greater in the last century, when the Sultanas could enter the shops of the Greeks and the Franks (the shops of the Turks are mere displays). There was a sister of the Sultan who renewed, it is said, the secrets of the Tour de Nesle affair. She ordered the merchandise she had chosen to be brought to her, and the unfortunate young men who were charged with such errands generally vanished without anyone daring to speak of them. All the palaces built on the Bosphorus have basement rooms beneath which the sea flows. Trapdoors cover the spaces assigned for women to bathe. It is supposed that the lady’s passing favourites took this route. The Sultana was simply punished with life imprisonment. The young men of Pera still speak with terror of those mysterious disappearances.

This brings us to the subject of the punishment of adulterous women. It is generally believed that every husband has the right to take justice into his own hands, and hurl his wife into the sea imprisoned in a leather bag with a snake and a cat. If this torment ever took place, it could only have been on the orders of Sultans or Pashas powerful enough to be responsible for that same. Similar acts of vengeance were seen during the Christian Middle Ages.

Let me acknowledge that, if a man does kill his wife after she is caught in the act, he is rarely punished, unless she is of noble family; but it is much the same with us, where the judges generally acquit the murderer in such cases. Otherwise, it is necessary, there, to be able to produce four witnesses, who, if they are mistaken or make false accusations, each risk receiving eighty lashes. As for the woman and her accomplice, duly convicted of the crime, they receive one hundred lashes each in the presence of a certain number of true believers. It should be noted that married slaves are only liable to fifty lashes, by virtue of the fine idea of the legislator that slaves should be punished only half as much as free people, slavery granting them only half of life’s good.

All this is in the Koran; it is true that there are many things, in the Koran as in the Gospel, that the powerful explain and modify according to their will. The Gospels do not pronounce on slavery, while, without even considering the European colonies, Christians own slaves in the East, like the Turks. The Bey of Tunis has, moreover, recently suppressed slavery in his domains, without contravening Muslim law. It is therefore only a question of time. But what traveller has not been astonished by the gentleness of oriental slavery? The slave is almost an adopted child, and is viewed as part of the family. A male slave often becomes the heir of the master; he is almost always freed upon his death by ensuring him the means of subsistence. We must see in the slavery of Muslim countries only a means of assimilation that a society which has faith in its own strength exerts over barbarian peoples.

It is impossible to overlook the feudal and military character of the Koran, but the true believer is the pure and strong man who must dominate by courage as well as by virtue; more liberal than the nobleman of the Middle Ages, he shares his privileges with whoever embraces his faith; more tolerant than the Hebrew of the Bible, who not only did not admit conversions but exterminated conquered nations, the Muslim leaves to each his religion and his morals, and claims only political supremacy. Polygamy and slavery are for him only means of avoiding greater evils, while prostitution, another form of slavery, devours European society like a form of leprosy, attacking human dignity, and driving from the bosom of religion, as well as other categories of established morality, poor creatures who are often victims of their parents’ greed, or of poverty. Should we not ask ourselves, moreover, what status our society grants to bastards, who constitute some tenth of the population? Civil law punishes them for the faults of their fathers by denying them family and inheritance. All the children of a Muslim, on the contrary, are born legitimate; they inherit equally.

As for the veils that women effect, it is an ancient custom which Christian, Jewish and Druze women follow in the East, and which is only obligatory in the main cities. Rural women, and those of the tribes, are not subject to the rule; also, the poems that celebrate the loves of Qays (Majnun) and Layla, of Khosrow and Shirin, of Jamil and Buthaina, and others, make no mention of veils or of the seclusion of Arabian women. Those faithful lovers reflect, in most of the details of their lives, the beautiful expressions of sentiment that have made all young hearts beat, from Daphnis and Chloe (by the second-century Greek writer Longus) to Paul et Virginie (by Bernadin de Saint-Pierre, 1788).

It must be concluded from all this that Islam rejects none of the elevated sentiments generally attributed to Christian society. The differences that have existed until now are much more in the form than in the substance of their and our ideas; Muslims in reality can be viewed as only a sort of Christian sect; many Protestant heresies are no less distant than they from the principles of the Gospel. This is so truly the case that nothing obliges a Christian woman who marries a Turk to change her religion. The Koran only forbids the faithful from uniting with idolatrous women, and agrees that, within all religions founded on the unity of God, it is possible to achieve salvation.

It is by imbuing ourselves with these just observations, and by stripping ourselves of the prejudices which still remain among us, that we will gradually overcome those who have hitherto called into question any alliance with, or submission to us, of the Muslim peoples.

Appendix 2: Female Seclusion in Cairo — Customs of the Harem

A man who has reached marriageable age, yet fails to marry, is held in low esteem in Egypt, and if he can offer no plausible reason for remaining single, his reputation suffers. Hence the many marriages in this country.

The day after the wedding, the woman takes possession of the harem, which is a part of the house separate from the rest. Girls and boys dance in front of the marital house, or in one of its inner courtyards. On this day, if the groom is young, the friend who, the day before, carried him to the harem comes to his house (Author’s note: the groom, if he is young and single, must appear timid, and it is one of his friends who, feigning to do him violence, carries him to the bridal chamber of the harem) accompanied by other friends; the groom is borne off to the countryside for the whole day. This ceremony is called al hurriya (a flight to freedom). Sometimes, the groom himself arranges this outing and pays part of the expense, if it exceeds the amount of the contribution (nukout) that his friends have imposed on themselves. To enliven the party, musicians and dancers are often hired. If the husband is of the lower class, he is escorted home, in procession, preceded by three or four musicians who play the flute and beat the drum; the friends and others who accompany the new groom carry bouquets. If they do not return until after sunset, they are accompanied by men carrying mishals, poles equipped with a cylindrical iron receptacle, in which burning wood is placed. The poles sometimes support up to five of these lanterns, which cast a bright light on the procession. Other people carry lamps, and the friends of the groom lighted candles and bouquets. If the husband is wealthy enough to do so, he arranges for his mother to stay with him and his wife, in order to watch over the latter’s honour and his own. It is for this reason, it is said, that the wife’s mother-in-law is called hama, meaning protectress or guardian.

Sometimes the husband leaves his wife with her own mother, and pays for the maintenance of both. One might think this practice would make the mother of the bride careful of her daughter’s conduct, if only out of self-interest, to preserve the alimony given to the wife by the husband, and to deny the latter a pretext for divorce. But it too often happens that this hope is disappointed.

In general, a prudent man who marries greatly fears his wife meeting with his mother-in-law; he tries to deprive the mother of any opportunity of seeing her daughter, and this prejudice is so deep-rooted, that it is believed much safer to take as a wife a woman who has neither mother nor near relations: some women are even forbidden to receive any female friends, except those who are relatives of the husband. However, this restriction is not generally observed.

As we have said above, the women live in the harem, a separate part of the Egyptian home; but, in general, those who have the title of wives are not considered prisoners. They are usually at liberty to go about, and visit others, and they can receive visits from their female friends almost as often as they wish. Slaves alone do not enjoy this liberty, as their state of servitude renders them subject to the wives and masters.

One of the master’s main concerns, in arranging the separate apartments which are to serve as the habitation of his wives, is to find ways to prevent them from being seen by male servants or other men, without being covered according to the rules that religion prescribes. The Quran (Koran) contains the following words on this subject, which demonstrate the necessity for every Muslim woman, the wife of a man of Arabic origin, to hide from men everything attractive about her, as well as the ornaments that she wears:

‘Say to the women of the believers that they should rule their eyes and guard their modesty from all harm; that they should not show any other ornaments than those which show themselves of themself; that they should spread their veils over their bosoms, and show their ornaments only to their husbands, or to their fathers, or to their husbands’ fathers, or to their sons, or to their husbands’ sons, or to their brothers, or to their brothers’ sons, or to their sisters’ sons, or to the women of these, or to the slaves whom they possess, as well as to the men who serve them and have no need of women or children — women should abstain from making noise with their feet so as to uncover the ornaments which they should hide.’ (see the Koran, ‘Sura XXIV, An-Nur’). The last passage alludes to the custom which the young Arabian women had, at the time of the Prophet, of clinking together the bracelets which they generally wore above the ankle. Many Egyptian women still wear these same kinds of ornament.

To explain the above passage from the Koran, which otherwise might give rise to a false idea of modern customs, concerning the admission or non-admission of certain persons to the harem, it is very necessary to transcribe here two important notes, taken from illustrious commentators.

The first relates to the expression: or to the women of these. That is to say, these women must be of the religion of Muhammad; for it is considered illegal or at least indecent for a woman who is a true believer to uncover herself before one termed an infidel, because it is thought that the latter will not refrain from describing her to others. Some think that foreign women in general should be rejected from the harem, but the doctors of the law do not agree on this point. It is the case that in Egypt, and perhaps also in all other countries where Islam is professed, it is no longer considered improper for a woman, whether she be free, a domestic, a slave, Christian or Jewish, Muslim or pagan, to be admitted into a harem. As for the second part, where slaves are spoken of, we read in the Koran: ‘Slaves of both sexes are part of the exception; it is also believed that domestics who are not slaves are included in the exception, as well as those who are of foreign nation.’ In support of this allegation, is the claim that ‘Muhammad having made his daughter Fatima a present of a male slave, she, wearing only a veil so scanty that she had to choose between the necessity of leaving her head uncovered, or of uncovering the lower part of her body, on seeing the slave enter, turned towards the Prophet, her father, who, seeing her embarrassment, told her that she should not be concerned, since her father and the slave alone were present.’ — It is possible that this custom is valid among the desert Arabs; but, in Egypt, an adult slave is never seen to enter the harem of a man of importance, whether he is a member of it or not. The male slave of a woman may obtain this favour perhaps, since he cannot become her husband as long as he is still a slave.

It is surprising that in the Sura of the Koran of which we are speaking, there is no mention of uncles having the privilege of viewing their nieces without veils. But it is thought the restriction was made to prevent them from giving their sons too seductive a sight of their young cousins. The Egyptians consider it very improper to praise a woman’s features; it is impolite to say that she has beautiful eyes, a Greek nose, a small mouth, etc., when describing her to a male whom the law forbids to view her; but she may be praised in general terms as being lovable and beautified by kohl and henna. (Author’s note: kohl is an aromatic eyewash that blackens the upper and lower eyelids, and is obtained by burning almond shells to which certain herbs are added, henna is a plant powder with which women dye certain parts of their hands and feet.)

In general, a man can only view his legitimate wives without a veil, as well as his female slaves, or women whom the law forbids him to marry because of their too close degree of consanguinity, or because they have been either his wet nurse, or that of his children, or because they are close relatives of his wet nurse — the wearing of a veil is a practice of the highest antiquity.

In Egypt it is believed that it is more essential for a woman to cover the upper part, and even the back of her head, than her face; but what is more essential still is that she should hide her face rather than most other parts of her body: for example, a woman who cannot be prevailed upon to remove her veil before men, will have no scruple about baring her throat, or almost her whole leg.

Most ordinary women appear in public with their faces uncovered; but it is said that necessity forces them to do so, because they cannot afford burqus (burkas, face veils).

When a respectable woman is surprised without a veil, she hastily covers herself with her tarha (a veil which covers the head) and cries out: ‘O misfortune! O agony!’ However, I have noted that coquetry sometimes leads them to show their face to men, but always as if by chance. From the top of the terrace of their house or through blinds, they seem to watch without interruption what is happening around them; but often they uncover the face with the definite intention that it should be seen.

In Cairo, the houses are generally small, and one hardly finds any apartments for men on the ground floor; they must therefore ascend to the first floor, where the women’s apartments are usually sited. But, to avoid encounters that are considered unpleasant in Egypt, and that in France would be considered the opposite, the men when ascending the stairs never cease to shout loudly: Destoor, Ya siti! (Permission oh lady!) or utter other exclamations, so that any women who might be on the staircase can withdraw, or at least cover themselves; which they do by drawing down the veil with which they hide their face in such a way as to leave only one eye barely visible. (Author’s note: Women remove their veils in the presence of eunuchs and young boys).

Muslims carry the idea of the sacred character of women to such an excess that, among them, men are forbidden to enter the tombs of various women; for example, they cannot enter those of the wives of the Prophet or other women of his family which are located in the Al-Baqui cemetery in Medina, while women are permitted to visit these tombs freely. Nor are a man and a woman ever laid in the same tomb, unless a dividing wall is built between the two coffins.

Not all Muslims are so rigid about women; for Edward Lane, who has collected these interesting details (taken or imitated from his ‘Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians’, 1836), says that one of his friends, a Muslim, allowed him to view his mother, who was fifty years old, but who, by her plumpness and freshness, did not appear to be more than forty. ‘She usually comes’ he says ‘to the door of the apartment of the hareem, in which I am received (there being no lower apartment in the house for male visitors), and sits there upon the floor, but will never enter the room. Occasionally, and as if by accident, she shows me the whole of her face, with plenty of kohl round her eyes; and does not attempt to conceal her diamonds, emeralds, and other ornaments, but rather the reverse. The wife, however, I am never permitted to see, though once I was allowed to talk to her, in the presence of her husband, round the corner of a passage at the top of the stairs.’ However, women are generally less restrained in Egypt than in other parts of the Ottoman Empire; it is not uncommon to see women flirting in public with men, but this occurs only amongst the lower classes. One might think, from this, that women of the middle and upper classes often feel unhappy, and detest the seclusion to which they are condemned; but, on the contrary, an Egyptian woman attached to her husband is offended if she enjoys too much liberty; she thinks that, in not watching her as strictly as is customary, her husband no longer loves her as deeply, and she often envies the fate of women who are guarded with more severity.

Although the law authorises Egyptian men to take four wives, and as many slaves as concubines as they please, they are commonly seen to have only one wife, or one slave as a concubine. However, a man, while limiting himself to the possession of one wife, may change his wife as often as his fancy takes him, and it is rare to find husbands in Cairo who have not been divorced at least once, if their state as a married man dates back some time. The husband may, as soon as he pleases, say to his wife: ‘You are divorced’, whether his wish is seen on her part as reasonable or not. After the pronouncement of this sentence, the wife must leave her husband’s house, and seek shelter either with friends or relatives. The power of men to announce a divorce unreasonably is the source of the greatest anxiety in women, and this anxiety surpasses all other anguish, given that they view abandonment and misery as its consequence; other women, on the contrary, who see divorce as a means of improving their lot, think quite differently, and desire divorce with all their hearts.

A man may divorce the same woman twice and then take her back without any formality; but the third time he may not legally take her back unless she has, in the interval between the divorces, contracted another marriage and a divorce from that marriage has taken place.

‘In illustration of this subject,’ Edward Lane says, ‘I may mention a case in which an acquaintance of mine was concerned as a witness of the sentence of divorce. He was sitting in a coffee-shop with two other men, one of whom had just been irritated by something that his wife had said or done. After a short conversation upon this affair, the angry husband sent for his wife, and as soon as she came, said to her, “Thou art trebly divorced;” then addressing his two companions, he added, “You, my brothers, are witnesses.” Shortly after, however, he repented of this act, and wished to take back his divorced wife; but she refused to return to him, and appealed to the “Sharia Allah” (or Law of God). The case was tried at the Mahkem’eh. The woman, who was the plaintiff, stated that the defendant was her husband; that he had pronounced against her the sentence of a triple divorce; and that he now wished her to return to him, and live with him as his wife, contrary to the law, and consequently in a state of sin. The defendant denied that he had divorced her. “Have you witnesses?” said the judge to the plaintiff. She answered, “I have here two witnesses.” These were the men who were present in the coffee-shop when the sentence of divorce was pronounced. They were desired to give their evidence, and they stated that the defendant divorced his wife by a triple-sentence, in their presence. The defendant averred that she whom he had divorced in the coffee-shop was another wife of his. The plaintiff declared that he had no other wife: but the judge observed to her that it was impossible she could know that; and asked the witnesses what was the name of the woman whom the defendant divorced in their presence? They answered that they were ignorant of her name. They were then asked if they could swear that the plaintiff was the woman who was divorced before them? Their reply was, that they could not swear to a woman whom they had never seen unveiled. Under these circumstances, the judge thought it advisable to dismiss the case, and the woman was obliged to return to her husband. She might have demanded that he should produce the woman whom he professed to have divorced in the coffee-shop, but he would easily have found a woman to play the part he required, as it would not have been necessary for her to show a marriage certificate; marriages being almost always performed in Egypt without any written contract, and sometimes even without witnesses.’

It happens quite frequently that the man who has announced a third divorce from his wife and who wants to take her back with her consent, especially when the divorce has been pronounced in the absence of witnesses, does not observe the legal prohibition which forbids him from taking her back if she has not remarried in the meantime.

Men, religiously attached to the observance of the law, find means of conforming to it, by employing the services of a man who marries the divorced woman, and undertakes to repudiate her the day after the marriage and return her to her former husband, whose wife she becomes again by virtue of a second contract, although this mode of proceeding is absolutely in conflict with the law. In these cases, the woman may, if she is of age, refuse her consent; in the case of minority, her father or legal guardian may marry her to whomever he pleases.

When a man, in order to remarry his divorced wife, wishes to conform to the custom which requires an interim marriage before he may take her back, he usually marries her to some very ugly man who is poor, or sometimes to a blind man. This man is called a musthilla or mustahall.

It is easy to see that the ease with which divorces are achieved has had a fatal effect on the morality of both sexes. In Egypt there are many men who have married twenty or thirty women in the space of ten years; and it is not rare to see women, still young, who have been, successively, the legitimate wives of a dozen men. There are even men who marry another woman every month. This practice can take place even among men of little means; they can choose, while passing through the streets of Cairo, a beautiful young widow, or a divorced woman of the lower class, who will consent to marry the man who meets her, for a dowry of about twelve francs and fifty centimes, and, when he sends her away, he is merely obliged to pay double this sum to provide for her maintenance during the iddah (period of waiting) which she must then undergo. It must be said, however, that such conduct is generally considered highly immoral, and there are few middle-class or upper-class parents who would wish to give their daughter to a man known to have divorced several times.

Polygamy, which again acts in a harmful manner as regards the morality of spouses, and which is approved only because it serves to prevent more immorality than it occasions, is rarer among the upper and middle classes than among the lower classes, although it is infrequent even among the latter. Sometimes a poor man allows himself two or more wives, each of whom can, by the work she does, provide more or less for his subsistence; but most people of the middle or higher classes renounce this system on account of the costs and inconveniences of all kinds which it incurs.

It may happen that a man who has a barren wife, and who loves her too much to divorce her, feels obliged to take a second wife solely in the hope of producing children; for the same reason he may take up to four wives. But, in general, inconstancy is the principal reason for indulging in polygamy or frequent divorce; but few men make use of this facility, and one meets with scarcely one man in twenty who has more than one legitimate wife.

When a man who is already married desires to take a second wife or daughter, the father of the latter, or the woman herself, refuses to consent to this union, unless he first divorces his first wife; it is seen from this that women in general do not approve of polygamy. Rich men, those of limited means, and even those of the lower class provide different houses for each of their wives. The wife receives, or may require from the husband, a detailed description of the lodgings intended for her, either in a single house, or in an apartment which must contain a room for sleeping and passing the day, and a kitchen and its dependencies; this apartment must be, or must be capable of being, separate or enclosed, without communication with any of the apartments of the same house.

The second wife is, as I have said, called the durrha (which word means parakeet, and is perhaps used derisively), and the quarrels which the pair give rise to are often spoken of as a thing quite understandable; since, when two women share the attentions and affections of one man, it is rare that they live together in harmony. Wives and slaves who are concubines, living under the same roof, often quarrel too. The law enjoins men who have two or more wives to behave absolutely impartially towards them; but strict observance of this law is very rare.

If the great lady is barren, and another wife, or even a slave, bears a child to the head of the family, often she becomes the favourite of the man, and the great lady is scorned by him, as Abraham’s wife was by Hagar. It then happens, not infrequently, that the first wife loses her rank and privileges, and that the other becomes the great lady in her place; her title as favourite of the master grants her all the outward marks of respect formerly enjoyed by the one whom she succeeds, now shown her by her rival or rivals, as well as all the women of the harem and the women who come to visit; but it is not rare that poison is employed to end her pre-eminence. When a man grants this preference to a second wife, it often follows that the first is declared nashizah (literally: ‘disobedient’), either by her husband, or at her own request made to the magistrate. However, there are a great number of instances of neglected women who act with exemplary submission to their husbands, and who are considerate towards the favourite. (Author’s note: When a woman refuses to obey the lawful orders of her husband, he may, and this is generally done, take her, accompanied by two witnesses, before the qadi, where he lodges a complaint against her; if the case is found to be true, the woman is declared by a written act nashizah, that is to say, rebellious to her husband: this declaration exempts the husband from housing, clothing and maintaining his wife. He is not forced to divorce, and may, by refusing to divorce, prevent his wife from remarrying as long as he lives. If she promises to submit thereafter, she regains her rights as a wife, but he may then pronounce them to be divorced.)

Some women have female slaves who are their property and who have been bought for them, or whom they have received as a gift before their marriage. These can only serve as concubines to the husband with the consent of their mistress. This permission is granted in rare cases; there are women who do not even allow their female slaves to appear without a veil before their husband. If a slave, having become the concubine of the husband without the consent of his wife, bears him a child, the child is a slave, unless before the birth, the slave has been sold or given to the father.

White slaves are usually owned only by wealthy Turks. Concubines who are slaves are not permitted to practise idolatry; they are generally from Abyssinia, and are acquired by the wealthy and middle-class Egyptians; their skin is of a dark-brown or tanned colour. From their features they appear to be of an intermediate race between the black Africans and whites, but they differ markedly from both races. They themselves believe that there is so little difference between their race and that of the whites, that they obstinately refuse to perform the functions of servants, or be subject to the wives of their masters.

The black African women, in their turn, prefer not to serve Abyssinians; but they are always very willing to serve the white women. Most of the Abyssinian women do not hail directly from Abyssinia, but from the territory of the Gallas (the Oromo people), which forms its neighbour; they are generally beautiful. The average price of one of these girls is two hundred and fifty to three hundred and seventy-five francs, if she is passably so: a few years ago, more than double that was paid.

The voluptuaries of Egypt esteem these women highly; but they are so delicate in health that they do not live long, and almost all die of consumption. The price of a white slave is quite commonly three times, and may well be up to ten times, as much as that of an Abyssinian; that of a black African is only half or two-thirds; but this price increases considerably if she is a good cook. The black Africans are generally employed as domestics.

Almost all the slaves convert to Islam; but they are rarely well-instructed in the rites of their new religion, and still less in its doctrines. Most of the white slaves in Egypt were Greek women who were among the great number of prisoners snatched from their country by the Turkish and Egyptian armies under the orders of Ibrahim Pasha. These unfortunates, among whom were children who could hardly walk, were shown no mercy and sold into slavery there. The impoverishment of the upper classes is evidenced these days by the lack of demand for the purchase of white slaves. Some have been brought from Circassia and Georgia, after having been given a preparatory education of sorts in Constantinople, and having been obliged to learn music and other pleasant arts. The white slaves being often the only companions, and sometimes even the wives of upper-class Turks, and being more esteemed than the ladies of Egypt who are not slaves, are in the general male opinion ranked higher than the latter. Such slaves are richly dressed, have lavished upon them gifts of valuable jewellery, and live in luxury and ease, so that, when not forced into servitude, their position seems most happy. This is proved by the refusal of several Greek women who had been placed in harems in Egypt, to accept the freedom which was offered them, on the cessation of the war with Greece; for it must be supposed that few were ignorant of the situation of their parents, and feared to expose themselves to poverty by re-joining them. There is no doubt that some of them are happy, at least for the moment; yet one is inclined to believe that the greater number, destined to serve their more favoured companions in captivity, or the Turkish ladies, or else forced to receive the caresses of some wealthy old man, or of men exhausted in body and mind by excess of all kinds, are unhappy, exposed as they are to being sold, or emancipated without means of existence, on the death of their master or mistress, and thus to pass into other hands, if they are childless, or else see themselves reduced to marrying some humble workman who cannot provide them with the comfort to which they had become accustomed.

Female slaves in middle-class Egyptian houses are generally better treated than those who enter the harems of the wealthy. If they are concubines, which is almost inevitable, they have no rivals to disturb the peace of their home, and, if they are domestics, their service is mild and their liberty less restricted. If there is a mutual attachment between the concubine and her master, her position is happier than that of a wife who may be dismissed by her husband; in a moment of ill-humour, he may pronounce against a wife the irrevocable sentence of divorce and thus plunge her into misery, whereas it is very rare that a man dismisses a slave without providing for her needs so abundantly that she loses little in the exchange if she has not been spoiled by too luxurious a life. On dismissing her, it is customary for her master to emancipate her by granting her a dowry, and to marry her to some honest man, or to make a present of her to one of his friends; in general, the sale of a slave who has long been in service is considered blameworthy. When a slave has a child by her master, and he acknowledges it as his own, the woman cannot be sold or given away, and she becomes free on the death of her master; often, immediately after the birth of a child which the master acknowledges, the slave is emancipated and becomes his wife; for, once she is free, he cannot keep her as a wife without marrying her legally.

Most of the girls of Abyssinia, as well as the young black Africans, are widely prostituted by the jellabs or slave-traders of Upper Egypt and Nubia, by whom they are traded to Egypt. Even at the age of eight or nine years, they are nearly all victims of these men’s brutality, and these poor children, especially those who come from Abyssinia, both girls and boys, experience such dreadful treatment at the hands of the jellabs, that, during the voyage, many of them throw themselves into the Nile and perish there, preferring death to their unhappy state.

Female slaves usually claim a higher price than male slaves. The price of slaves who have not had smallpox is less than the price of those who have. The purchaser is granted three days of probation; during this time, a female, purchased conditionally, remains in the harem of the purchaser or in that of one of his friends, and the women of the harem are charged with making their report on the newcomer: snoring, grinding her teeth, or talking in her sleep, are sufficient reasons to terminate the deal and return her to the seller. The slave women wear the same clothing as the Egyptian women.

Egyptian girls or women who are obliged to serve are charged with the basest occupations. In the presence of their master, they are usually veiled, and, when they are occupied about some detail of their service, they arrange their veil in such a way as to uncover only one of their eyes and to have one of their hands free.

When a foreigner is received by the master of the house in some room of the harem, the women composing the master’s family having been sent to another room, the other women serve him; but then they are always veiled.

Such are the relative conditions of the various classes in the harems; we must now take a look at the habits and occupations of those who inhabit them.

Wives and female slaves are often excluded from the privilege of sitting at table with the master of the house or his family, and they may be called upon to wait on him when he dines or sups, or even when he enters the harem to smoke or take coffee. They often act as servants; they fill and light his pipe, make his coffee, prepare the dishes he wishes to eat, especially when they are delicate and unusual dishes. The dish which the host recommends to you as having been prepared by his wife is usually perfectly made. The women of the upper and middle classes make it a very particular study to please their husbands, and to fascinate them by endless attention and teasing. Their coquetry is noticeable even in their gait; when they go out, they give to their bodies a very particular undulating movement which the Egyptians term ghung. They are always reserved in the presence of their husband: they also prefer his visits during the day to be infrequent, and not too prolonged; during his absence, their gaiety is expansive.

The food of the women, though similar to that of the men, is more frugal; they take their meals in the same manner as the men do. Many women are permitted to smoke, even those of the upper class, the odour of the fine tobaccos of Egypt being most perfumed. The pipes employed by the women are thinner and more ornamental than those of the men. The tip of the pipe is sometimes made of coral instead of amber. The women use musk and other perfumes, and employ cosmetics; they often prepare consumables which they drink or eat for the purpose of acquiring a certain degree of plumpness. Contrary to the taste of the Africans and of the Oriental peoples in general, the Egyptians are not great admirers of large women; for, in their love songs, the poets speak of the object of their passion as slender beings. One of the dishes to which women attribute the virtue of rendering them fatter is quite disgusting; it is principally composed of crushed snails. Many women chew incense and opium (ledin), in order to perfume their breath. The habit of frequent ablutions renders their bodies extremely clean. Their toilette is quite brief, and it is rare that after dressing in the morning, they change their dress during the day. Their hair is braided while they are bathing, and this coiffure is so well done, that it need not be renewed for several days.

The principal occupation of Egyptian ladies is the care of their children; they also superintend domestic affairs; but, generally, it is the husband alone who incurs and regulate their expenses. The hours of leisure are employed in sewing and embroidery, especially of handkerchiefs and veils. The embroidery on silk is usually coloured or in gold; the fabric is made on a loom called a menseg, which is usually made of walnut wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell (the cheapest are made of beech). Many women, even those who are rich, add to their private purse by embroidering handkerchiefs and other objects which they give to a dellaseh (a broker), who carries them off, and displays them in the bazaar, or tries to sell them in another harem. The visit of the women of one harem to those of another harem often occupies almost a day. The women, thus assembled, eat, smoke, and drink coffee and sherbets; they converse, parade their luxury objects, and all this suffices for their amusement. Unless business is of a very pressing nature, the master of the house is not admitted to these female gatherings, and he must, in such cases, give notice of his arrival, so that the female visitors may have time to veil themselves, or retire to another part of the apartment. The young women, being thus free from all fear of surprise, give way to their natural gaiety and abandon, and often display a playful and noisy spirit.

Appendix 3: Particular Celebrations

A celebration takes place among the Egyptians whenever a son becomes a member of a society of merchants or artisans. Among carpenters, wood-turners, barbers, tailors, bookbinders and people of other trades, such admission takes place in the following manner:

The young man to be admitted to the trade, accompanied by his father, visits the sheik and the father informs him of his intention that his son be admitted as a member of the company. The sheik then sends for the masters of the trade of which the son is the neophyte, along with some of the candidate’s friends, that they might attend his reception. An officer, called a naqib, then distributes stems of green grass or flowers to each of the persons invited saying: ‘Let us repeat Al-Fatiha (the first sura of the Koran) for the Prophet.’ To which the naqib adds: ‘Come on such and such a day, and at such a time, to drink coffee.’

The persons thus invited gather either at the father’s house or that of the young man, or sometimes in the countryside, where they are treated to coffee and served dinner.

The neophyte is brought before the sheikh; verses in praise of the Prophet are recited, then a shawl tied with a knot at the ends is tied around his waist. Verses from the Koran are recited, then a second knot is tied in the shawl; with the third knot, which is tied after a few more verses from the Koran have been said, a rosette is fastened to the shawl, and the young man is admitted as a member of the trade to which he is dedicating himself. Then he kisses the hand of the sheikh and of each of the persons present; he makes a small contribution and becomes a member of the trade.

Egyptians, who usually live in the most frugal manner, give feasts involving much variety and profusion; but the time devoted to resting is very short. In gatherings of this kind, people usually smoke, sip coffee or sherbets, and make conversation.

During the reading of the Koran, the Turks generally abstain from smoking, and the honour they pay to the sacred book has caused it to be said of them that ‘Allah has set the line of Othman above those of other Muslims, for they honour the Koran more fully than others!’

The only entertainment at these gatherings is derived from a few stories or tales; but everyone takes extreme pleasure in the dancing, and the musicians’ concerts, performed during these festive days.

It is to be noted that Egyptian men enjoy playing games for entertainment, unless in a small group of two or three people or with the family. Although sociable, Egyptians rarely give large parties, the pretext for which must be some extraordinary event, such as a marriage, a birth, etc. It is only then that it is appropriate to admit dancers to private homes; in all other circumstances, this is considered to be against custom.

There are, certainly, feasts on the occasion of marriages. On the seventh day (yom es saba’a) after the marriage, the bride receives her women friends, in the morning and in the afternoon. Sometimes, during this time, the husband receives his friends, whom he entertains in the evening by means of music and dance. The custom established in Egypt is that the husband abstains from the rights given to him by marriage until after the seventh day if the one he marries is a young virgin. At the end of this time, it is customary to give a feast and to gather friends. Forty days after the marriage, the young bride goes to the baths with some of her friends. On returning home, the bride gives them food, then they depart. During this time, the husband gives a meal, and dancing and music are performed.

The day after the birth of a child, two or three male or female dancers perform their art in front of the house or in the courtyard. The celebrations for the birth of a son are more extensive than those for a daughter. The Arabs still retain that sentiment which led their ancestors to destroy their children of the female sex.

Three or four days after the birth of a child, the women of the house, if the woman who has given birth belongs to one of the upper or well-off classes, prepare dishes composed of honey, clarified butter, sesame oil, spices and aromatic herbs, to which are sometimes added roasted hazelnuts. (Author’s note: some women add to those dishes not intended for friends a paste made from snails which, they believe, will make the women fatter.)

The child is then displayed, by women or young girls, throughout the harem; each of them carries lighted candles of varying colours: these candles, cut in two, are set in lumps of a certain paste formed of henna; several are placed on a tray. The midwife, or another of the ladies present, throws salt mixed with fennel seed on the ground. This mixture, placed the day before at the head of the child’s cradle, serves to protect from evil spells. The woman who sprinkles this salt says: ‘May this salt lodge in the eye of those who fail to bless the Prophet!’ or else: ‘May this impure salt enter the eye of the envious!’ and each of the persons present answers: ‘O Allah! Protect our lord Muhammad!’

A silver tray is presented to each of the women; they say aloud: ‘O Allah! Protect our lord Muhammad! May God grant you long years! etc.’ The women usually add the gift of an embroidered handkerchief, in one of the corners of which is a gold coin; this handkerchief is most often placed on the child’s head or to its side. The gift of a handkerchief is considered as a debt contracted which is paid on a similar occasion, or which serves to pay a debt contracted on a similar occasion. The coins thus collected serve to adorn the child’s headdress for several years. Besides this largesse, they also give the like to the midwife. On the eve of the seventh day, a carafe filled with water, the neck of which is surrounded by an embroidered handkerchief, is placed at the head of the sleeping child’s cradle. The midwife then takes a carafe which she places on a tray, and she offers each woman who comes to visit the mother a glass of this water, which each of them pays for by means of a gratuity.

For a certain time after childbirth, which differs according to the attitude or doctrine of the various sects, but which is usually forty days, the woman who has given birth to a child is considered impure. After this time, termed nifa, she goes to the baths, and from then on is deemed purified.

Appendix 4: Egyptian Dancers

Of all the dancing women of Egypt, the most renowned are the Ghawazi, so called from the name of their tribe. A woman of this tribe is called a Gazyeh, a man a Gazy, but the plural Ghawazi is generally applied to women. Their dance is not always graceful. At first, they begin with a sort of reserve; but soon their look becomes animated, the sound of their copper castanets gains rapidity, and, by means of the increasing energy of their movements, they end by giving an exact representation of the dance of the women of Gades (Cadiz), as described by Martial (‘Epigrams V, LXXVIII’) and Juvenal (‘Satire XI: 162-164’). The costume in which they thus appear is similar to that which the Egyptian women of the middle-class wear within the harem. It consists of the yalek or anteri (long dress), the shintyan (wide trousers) etc., composed of beautiful fabrics, to which they add various ornaments. The rims of their eyes are shaded with black collyrium; the ends of the fingers, the palms of the hands, and certain parts of the feet are coloured with red henna dye, according to the custom common to Egyptian women of all conditions. In general, these dancers are followed by musicians belonging for the most part to the same tribe; their instruments are the kamancheh or rubab (a bowed string instrument), the tar or tarabouk (a drum), and the zukrah (a form of bagpipes). The tar, in particular, is usually in the hands of an old woman. It often happens that on the occasion of certain family celebrations, such as marriages or births, the ghawazi are allowed to dance in the courtyards of houses, or in the street, before the doors, but without ever being admitted to the interior of an honest harem; on the other hand, they are commonly hired for the entertainment of a gathering of men. In this case, as one can imagine, their performances are even more lascivious. Some wear only the shintyan in these private meetings and the tob, that is to say a very loose shirt or dress in coloured gauze, semi-transparent and open in front to about halfway down. If they still affect a remnant of modesty, it does not hold out long against the intoxicating liquors that are poured for them in abundance.

Is it necessary to add that these women are the most wretched courtesans in Egypt? However, some of them are of great beauty, most of them are richly-dressed, and they are, in short, the loveliest women in the country. It is remarkable that a certain number of them have somewhat aquiline noses, although in all other respects they are of the original type. Some women, as well as men, take pleasure in gathering about them in the streets; but honest and upper-class people shun them.

Although the Ghawazi differ slightly in appearance from other Egyptians, we doubt very much whether they are of a distinct race, as they affirm themselves. Their origin, however, is surrounded with much uncertainty. They claim to be called Baramikeh or Bormekeh, and boast of being descended from the famous family of the Barmekids, who were the objects of the favours, and afterwards of the capricious tyranny, of Haroun-al-Rashid, who is mentioned several times in the Arabic tales of the Thousand and One Nights. But, as has been remarked above, they have no other claim to bear the name of Baramikeh than the liberality they share with them, although theirs is of a very different kind.

On many of the ancient Egyptian tombs, Ghawazi (females) are represented dancing in the freest manner to the sounds of various instruments, that is to say, in a manner analogous to that of the modern Ghawazi, or perhaps even more licentiously; for one or more of these figures, although placed beside eminent personages, are usually represented in a state of complete nudity. This custom of thus adorning the monuments of which we speak, and which, for the most part, bear the names of ancient kings, shows how common such dances were throughout Egypt in the most remote times, even before the flight of the Israelites. It is therefore probable that the modern Ghawazi are descended from that class of dancers who entertained the first pharaohs. It might be inferred, from the resemblance of the fandango to the dances of the Ghawazi, that it was introduced into Spain by the Arab conquerors; but it is known that the women of Gades (Cadiz) were renowned for these kinds of performances from the earliest days of the Roman Empire.

The Ghawazi, both men and women, are generally distinguished from other classes by marrying only among themselves; but a gazyeh is occasionally seen to take a vow of poverty, and to marry some honourable Arab, who is generally not discredited by the alliance. The Ghawazi are all destined for wretched professions, but not all devote themselves to dancing. The greater number marry, but never before they have embraced the state they have chosen.

The husband is submissive to the wife, he serves as her householder and provider, and generally, if she is a dancer, he is also her musician. However, some men earn their living as blacksmiths, stone-cutters or coppersmiths.

Although some of the Ghawazi possess considerable property and rich ornaments, many of their costumes are similar to the gypsies (the Romani, or Roma, people) found in Europe, who are supposed to have originated in Egypt. The ordinary vocabulary of the Ghawazi of both sexes is that of the rest of the Egyptians; but sometimes they employ a certain number of words peculiar to themselves, in order to render themselves unintelligible to foreigners. As to religion, they openly ascribe to Islam, and groups often follow the Egyptian caravans to Mecca. A great number of Ghawazi are seen in almost all the considerable towns of Egypt. Their dwellings are generally low huts, or portable tents as they often travel from one town to another. Some, however, settle in large houses, and purchase young black slaves, and also camels, asses, and cows, in which they traffic. They are camp-followers, and are present at every festival, religious or otherwise; which, to many people, is their chief attraction. On these occasions, many tents of the Ghawazi are seen; some sing as well as dance, and associate with the Awalim, who are of the lowest class. Others again wear the gauze tob over another garment with the shintyan and a tarhah of crepe or muslin, and generally adorn themselves with a profusion of ornaments and decoration, such as lace embroidery, bangles, and ankle-bracelets. They also display a band of gold coins on their foreheads, and sometimes a ring in one of their nostrils, and all use the colour of henna to dye their hands and feet.

In Cairo, many people who affect to believe that there is no other impropriety in these dances than that of their being performed by women, who should not expose themselves thus in public, employ men for this kind of entertainment; but the number of these dancers, who are for the most part young men, and who are called khawals, is quite limited. They are natives of Egypt. Since they dress as, and represent, women, their dances have the same character as those of the Ghawazi, and they employ their castanets in the same manner. But, as if they wished to avoid their performance being taken seriously, their costume, which in this respect accords with their singular profession, is half-masculine and half-feminine: it consists principally of a tight jacket, a girdle, and a kind of skirt; however, their ensemble seems more feminine than masculine, doubtless because they let their hair grow and plait it in the manner of the female sex. They imitate women by tinting their eyelids and colouring their hands with henna. In the streets, when they are not dancing, they are often veiled, not out of shame, but simply to better imitate feminine manners. They are also often employed in preference to the Ghawazi, to dance in the courtyards, or at the doors, of houses on the occasion of family celebrations. There is in Cairo another class of dancers, both men and boys, whose exercises, costume, and appearance are almost exactly similar to those of the khawals; but they are distinguished from the latter by the name of gink (Zingaris, gypsies, bohemians), a Turkish word which perfectly expresses the character of these dancers, who are generally Jewish, Armenian, or Greek.

Appendix 5: Jugglers and Entertainers

There is in Egypt a class of men who are supposed to possess, like the ancient psyllids of Cyrenaica (eastern Libya), that mysterious art alluded to in the Bible, which renders them invulnerable to the bite of serpents. Many writers have given surprising accounts of these modern psyllids, whom the most enlightened Egyptians regard as impostors; but no one has given satisfactory details of their more commonplace or interesting feats.

Many Dervishes of the lower orders earn their living by performing a kind of exorcism around houses to drive off snakes. They travel throughout Egypt, often finding employment, though their earnings are small. The conjuror claims to discover without looking whether there are snakes present or no; and, when there are, he affirms that he can attract them to him by the fascination of his voice alone. Then he assumes a mysterious air, strikes the walls with a small palm-stick, whistles, imitates the clucking of a hen with his tongue, spits on the ground and cries: ‘Whether you are above or below, I adjure you in the name of God to appear at once! I adjure you by the greatest of names! If you are obedient, appear! and, if you are disobedient – Die! Die! Die!’ Usually, the snake is dislodged by his wand from some crack in the wall, or falls from the ceiling of the room.

Jugglers and entertainers, called houvas, are numerous in Cairo. They are found in the squares, surrounded by a circle of spectators; they are also seen at public festivals, attracting applause, and jeers often improper ones. They perform a great number of tricks, of which the most common are as follows: generally, the juggler is assisted by two accomplices; he draws four or five medium-sized snakes from a leather bag, places one on the ground, and makes it raise its head and part of its body; with a second snake, he crowns one of his assistants as with a turban, and wraps the two others around his neck; he removes them, then opens the boy’s mouth and seems to pass the bolt of a kind of padlock through his cheek, and close it; he then pretends to drive an iron point into his throat, but in reality makes it disappear into the wooden handle into which it is fitted. Another trick of the same kind is as follows: the juggler lays one of his boys on the ground, presses the edge of a knife to his nose, and strikes the blade until it seems to be sunk to half its width. Most of the tricks he performs alone are more amusing: for example, he draws from his mouth a large quantity of silk, which he winds round his arm; or, he fills his mouth with cotton, and breathes fire; or, he draws forth (always from his mouth) a large number of small tin coins, round like dollars, and inhales them again through his nose in a jet like the stem of a clay pipe. To announce most of his tricks, he blows at various times into a large conch-shell called a zummarah, the sound of which resembles that of a horn.

Another quite common trick is to place a certain number of small strips of white paper in a tin receptacle in the shape of a sherbet mould, and to take them out dyed in different colours; to put water in this same receptacle, to add to it a piece of linen, and to offer it to the spectators, changed to sherbet. Sometimes the juggler cuts a shawl in two, or burns it in the middle, and immediately makes it whole again. At other times he takes off all his clothes except his baggy drawers and tells two people to tie him up by the feet and hands, and imprison him in a bag; this done, he asks for a piastre; someone answers that he will have it if he can extend one of his hands to receive it; he immediately draws one hand out of the bag, grasps it, withdraws his hand, and then appears to be as tightly bound as before; his hand once back in the bag he immediately emerges from it, freed from all bonds, and carrying a small tray surrounded by lighted candles (if the exercise is in the evening) and garnished with five or six small plates of various dishes which are offered to the spectators.

There is in Cairo another species of jugglers called skyems. In most of their exercises, the skyems also have a compère. The latter, as an example, places twenty-nine small stones on the ground, sits down by them and arranges them before him. Then he asks someone to hide a coin under one of them. This done, he summons the skyem, who stands at a distance during this procedure, and, informs him that a coin has been hidden under one of the stones, he asks him to indicate under which one it resides, which the skyem immediately does. The trick is very simple; the twenty-nine stones represent the Arabic alphabet, and the compère takes care to begin his request with the letter represented by the stone under which the coin is hidden.

The art of fortune-telling is often practiced in Egypt, and mostly by Bohemians similar to our own. They are called Guayaris. In general, they claim descent from the Barmekids, like the Ghawazi, but from a different branch.

Most of the women are fortune-tellers; they are often seen in the streets of Cairo dressed like almost all women of the lowest class, with the tob and tarbouch, but always with their faces uncovered. A Guayari usually carries a leather bag containing the equipment of her profession, and she goes through the streets shouting: ‘I am the fortune-teller! I explain the present, I divine the future!’

Most Guayaris practise such divination by the use of a certain number of shells, pieces of coloured glass, silver coins, etc., which they throw down pell-mell, and draw their conclusions according to the order in which chance arranges the items. The largest shell, for example, represents the person whose fate they are to discover; other shells represent favourable or unfavourable events, etc., and it is by their relative position that the diviner judges whether one event or the other will or will not happen to the person in question. Some of these gypsies also cry: Nedoukah oué entchir! (We tattoo, and circumcise!)

Some Bohemians also play the part of a bahlonan, a name given to famous minstrels, swordsmen, or champions, all people who formerly made a name for themselves in Cairo by displaying their strength and dexterity. But the performances of the modern bahlonans are almost exclusively restricted to tightrope-dancing, and all those who practice the art are Bohemians. Sometimes their rope is attached to the medeneh (minaret) of a mosque, at a prodigious height, extending for a length of several hundred feet, supported here and there by poles planted in the ground.

Women, girls and boys willingly take up this form of entertainment; but the latter also do other exercises, such as feats of strength, leaping through hoops, etc.

The skouradatis (the name is derived from a word for monkey), amuse the lower classes in Cairo by means of various tricks performed by a monkey, donkey, dog, and little goat. The man and the monkey (the latter usually of the species of cynocephali, an ape such as a baboon) fight the other three with sticks. The man dresses the monkey in bizarre fashion, like a bride or a veiled woman; he precedes it, beating a tambourine, and makes it parade thus on the back of the donkey amidst the circle of spectators. The monkey is also required to perform several grotesque dances. The donkey is told to indicate the prettiest girl, which he immediately does, putting his nostrils into the face of the fairest, to his great satisfaction, as well as that of all the bystanders. The dog is ordered to imitate a thief, and begins to crawl on its belly. Finally, the supreme act is that of the little goat. It stands on a small piece of wood having about the shape of a dice-box, about four inches long by one and a half wide; so that its four feet are gathered together in this narrow space. The piece of wood thus supporting the creature is raised; a similar one is slipped underneath; then a third, a fourth, and a fifth are added without the goat leaving its place.

The Egyptians often amuse themselves in seeing vulgar and ridiculous farces performed, which are called mouabazins. These performances often take place at the festivals preceding marriages and circumcisions, among the nobility, and sometimes attract numerous spectators to the public squares of Cairo; but they are rarely worthy of description, since it is chiefly through coarse and indecent jokes that they gain applause. They are performed by male actors; the female roles being always filled by men or young boys in feminine attire.

Here, as a specimen of their plays, is a glimpse of one of those which were played before Mehemet-Ali, on the occasion of the circumcision of one of his sons, when according to custom, several other children were also circumcised.

The characters in the drama are a nazir or district governor, a sheik-el-beled, or village chief, a servant of the latter, a Coptic cleric, a poor devil indebted to the government, his wife, and five other characters who make their entrance, two playing the drum, a third the oboe, and the other two dancing. After they have danced a little and played their instruments, the Nazir and the other characters form a circle.

The Nazir asks:

— ‘How much does Owad, Regeb’s son, owe?’

The musicians and dancers, who play the role here of simple fellahin, respond:

— ‘Tell the clerk to view the register.’

This cleric is dressed like a Copt; he wears a black turban and carries at his belt everything he needs for writing. The sheik says to him:

— ‘For how much is Owad, Regeb’s son, indebted?’

The cleric replies:

— ‘For a thousand piastres.’

— ‘How much has he paid already?’ the sheikh adds.

The cleric answers:

— ‘Five piastres.’

The sheik says to the debtor:

— ‘My good man, why have you not brought the rest?’

The man replies:

— ‘I have no money.’

— ‘You’ve no means of paying?’ cried the sheik. ‘Let this man be laid on the ground!’ he adds.

They bring a kind of leather whip with which they beat the poor wretch who shouts to the Nazir:

— ‘O Bey! By the honour of your horse’s tail; O Bey! by the honour of your headband, O Bey!’

After about twenty such absurd appeals to the Nazir’s generosity, the beating ends, and the victim is borne away and imprisoned. In another scene: the prisoner’s wife visits him and asks him how he is; he answers her:

— ‘Do me the favour, my wife, of taking some eggs and pastries, to the Copt’s house, and beg him to obtain my freedom.’

The woman takes the requested objects in three baskets to the Copt’s; she asks if he is there; she is told yes; she introduces herself and says:

— ‘O Mahlem-Hannah! Please accept these, and obtain my husband’s deliverance.’

— ‘Who is your husband?’

— ‘He is the fellah who owes a thousand piastres.’

— ‘Bring two or three hundred as a tribute to Sheikh-el-Beled.’

The woman obtains the lesser amount and frees her husband.

One can see from this that comedy serves, for the people, as a warning to the great, while seeking improvement and reform; this was often the meaning and aim of the dramatic art of the European Middle Ages. The Egyptians are still at that stage of development.

Appendix 6: The Houses of Cairo

The modern metropolis of Egypt is called in Arabic Al-Kahira, from which the Europeans formed the name Cairo. The people call it Masr or Misr, which is also their name for the whole of Egypt. The city is situated at the entrance to the valley of Upper Egypt, between the Nile and the eastern chain of the Mokattam mountains; it is separated from the river by a strip of land almost entirely cultivated, and which, on the northern side, where the port of Bulaq is situated, is more than a mile wide, while it extends less than half that distance on the southern side.